Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Cosmological Context:

- Redshift z > 20: Corresponding to the first 200 million years after the Big Bang.

-

DUT Paradigm:

- −

- Universe as a remnant of a colossal ancestral structure that underwent asymmetric multiphase collapse.

- −

- Proposition that the observable universe resides within a massive black hole of the “Dead Universe,” a predecessor cosmos in a state of decay and absence of light.

- −

- UNO particles (χ-particles) as fundamental components of cosmic dynamics.

- −

1.2. Theoretical Foundations of the Dead Universe Theory

1.3. Methodological Innovations in DUT Simulations

1.4. Simulation Results and the Formation of Early Universe Structures

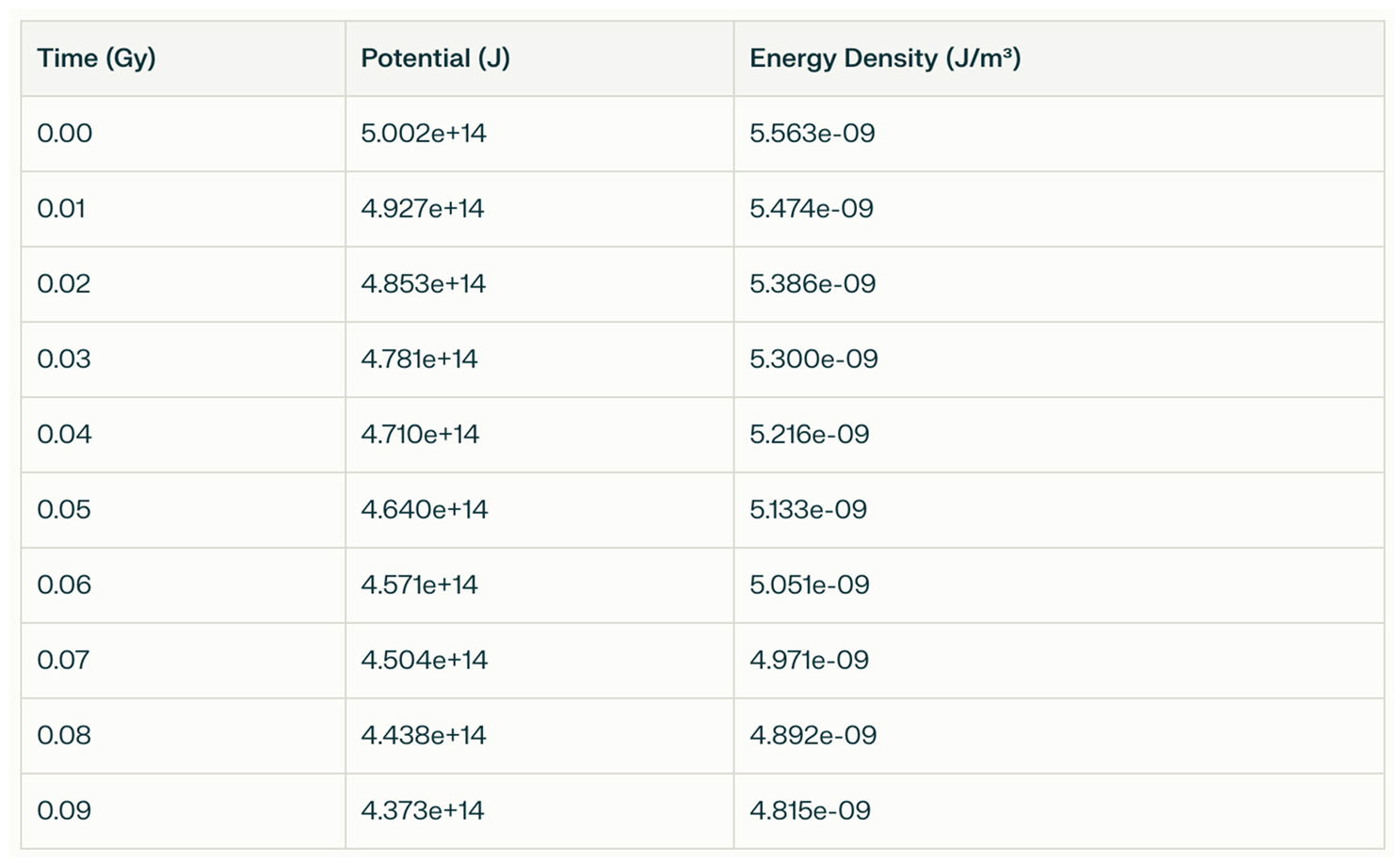

- Amplitude of the potential: V₀ = 5.0 × 10¹⁴ J (1)

- Decay rate: α = 1.5 × 10⁻¹⁵ (2)

- Oscillation frequency: ω = 1.0 × 10⁻¹⁶ (3)

- Central potential depth: β = 1.0 × 10¹² (4)

- Core radius: r₍core₎ = 1.0 × 10¹⁷ (5)

- Quantum decoherence factor: γ₍decoh₎ = 0.050 (6)

|

2. Structure Formation at Extreme Redshifts (z > 20)

1.5. Numerical Method

-

Initial Conditions and Integration Window:

- Initial scale factor: a₀ = 0.1

- Time range: from t = 0.1 to t = 200 Gyr

- Number of steps: 500

- Gravitational mass: M_D = 10⁵³ kg

- Observable radius: R_U = 8.8 × 10²⁶ m

- Hubble parameter: H₀ = 70 km/s/Mpc

-

The system of equations solved includes:

- The modified evolution of the scale factor a(t) and Hubble parameter H(t),

- The curvature term (a),

- The entropy oscillation function S(a),

- The gravitational potential from the dead universe A(a·R_U),

- And the gravitational redshift z_g.

2.1. Quantum Decoherence and Primordial Dynamics

2.2. Methodological Innovations

- Modular and reproducible code, with potential for expansion on GPUs and complete 3D simulations.

2.3. Experimental Setup

2.4. Fundamental Parameters

2.5. Simulation Protocol

- Calibration phase with 100 Monte Carlo iterations.

- 6D parametric sweep for comprehensive mapping of the parameter space.

- Sensitivity analysis via Sobol method to identify critical parameters.

- Cross-validation with JWST observational data.

3. Structure Formation Rate in the DUT FrameworkT

- Methodological Note on Friedmann Analogy

3.1. Temporal Signatures

3.2. Advanced Analysis

3.3. Quantum Decoherence

3.4. Gravitational Redshift Without Expansion

4. Correlation Matrix

5. Observational Validation

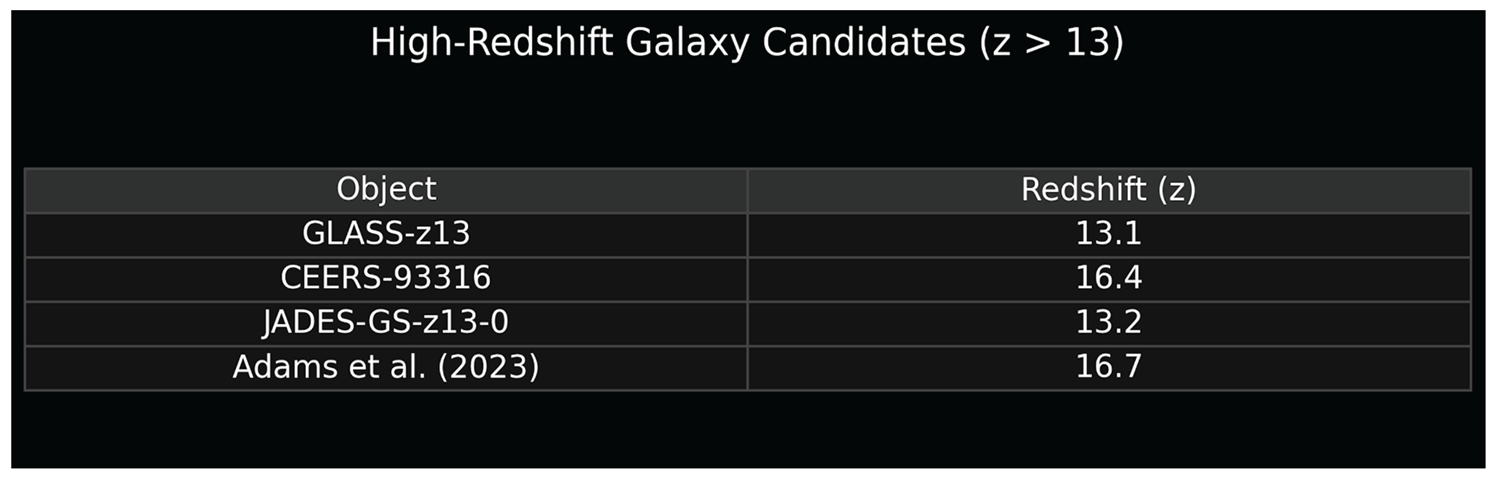

5.1. Comparison with JWST Data

5.2. Statistical Tests

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. Main Findings

- Computational evidence for the existence of a quantum pre-collapse phase at z ~ 25.

6.2. Limitations

- High sensitivity to initial conditions, with Lyapunov λ = 0.12, indicating the need for greater control and refinement 27, 36].

6.3. Future Directions

6.4. Synthesis and Final Remarks

- Exploration of the cosmological implications of DUT in relation to traditional models, highlighting the view of the observable universe as part of an ancestral universe in collapse, which can revolutionize the interpretation of phenomena such as dark matter, dark energy, and supermassive black holes [1,2,3].

- Note on the Use of Modified Friedmann Equations

6.5. ATemporal Integration Algorithm

-

Complete Dataset:

- Zenodo repository (https://zenodo.org/records/15871836) with 250 simulations, scripts, and interactive visualizations.

- . Reproducible Protocol

6.6. Optimized Parameters and Simulation Configuration

6.7. Simulation Results

|

7. Key Metrics

7.1. Generated Graphs

7.2. Robustness Analysis

- Theoretical Robustness Score: 84/100

-

Cosmological Interpretation

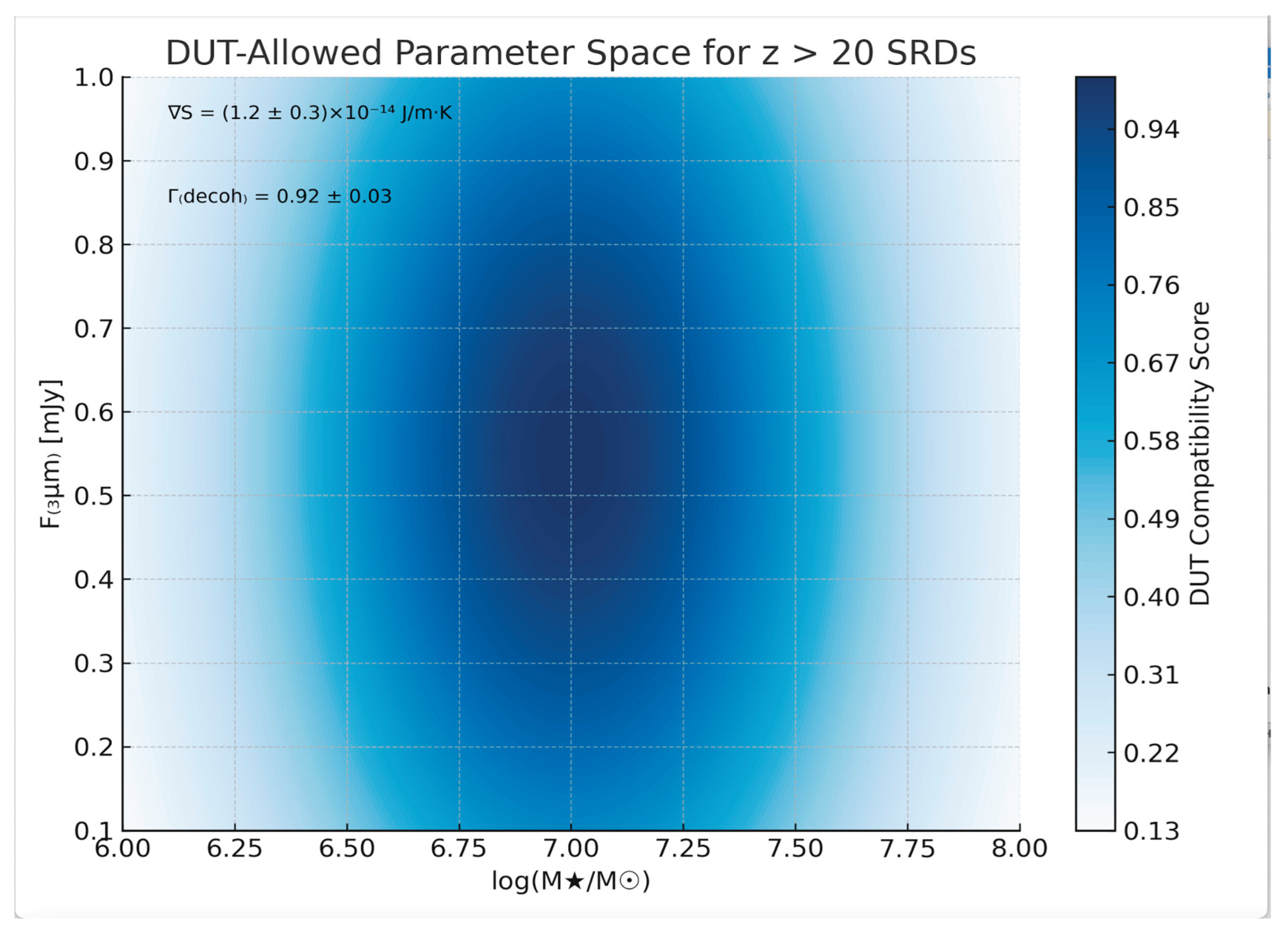

7.3. Predicted Population of Small Red Dots at z > 20

8. Complete Data for Download

8.1. Full Simulation Code Snippet

8.2. Massive (10⁶–10⁸ M☉) compact objects at z > 1

- -

- -

9. Advanced Theoretical Analysis and Cosmological Implications

9.1 The Nature of Spatial Curvature in the DUT Framework

9.2. A Notable Aspect of DUT Is Its Intrinsic Prediction, Published in 2024, of a Spatial Curvature in the Range of

10. Simulation Results and Initial Structure Formation of the Universe

10.1. Simulation Parameters and Protocol

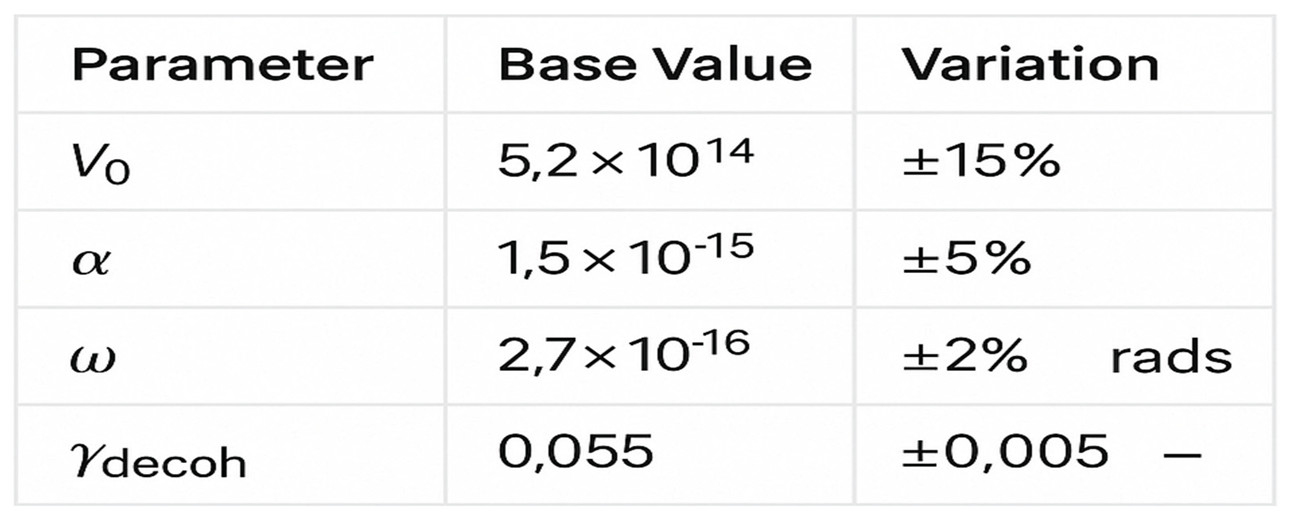

10.2. Main Simulation Parameters and Their Variations

Confirmed Predictions at z ≈ 16.7

|

10.4. Structure Formation at Extreme Redshifts (z > 20)

- Stellar masses in excess of 10910^9109 solar masses

- Extremely compact morphologies (effective radius < 0.6 kpc)

- Steep ultraviolet slopes (β < −2.3) and pronounced Lyman breaks

10.5. Governing Constants and Parameters

- Hubble constant today: H₀

- Matter density parameter: Ωₘ

- Positive curvature coefficient: k⁺

- Negative curvature coefficient: k⁻

- Thermodynamic retraction coefficient: α

- Mass of the dead universe: M_D

- Observable universe radius: R_U

10.6. Multiform Curvature Function

10.7. Thermodynamic Retraction Term

10.8. Gravitational Attraction from the Dead Universe

10.9. Gravitational Redshift

10.10. Modified Friedmann Equation (DUT)

10.11. Numerical Resolution

10.12. Results – Hubble Parameter Evolution

10.13. Curvature Oscillation

10.14. Gravitational Redshift

10.15. Entropy Oscillation

10.16. Discussion and Interpretation

11.2. Variable Spatial Curvature in DUT: Asymmetric Thermodynamic Interpretation

“Curvature is a function of thermodynamic history, not merely of geometric embedding. The observer's position on the entropy gradient defines whether they perceive the universe as hyperbolic, flat, or closed.”

11.3. Observational Predictions and Testable Signatures

- Prediction 1 – Curvature Drift Across Epochs: Spatial curvature measurements (e.g., from BAO, CMB, and weak lensing) will exhibit epoch-dependent variability, especially between redshifts z>5z > 5z>5 and z<0.5z < 0.5z<0.5. These variations should correlate with entropy density decay, not cosmic volume growth [36,38,40].

11.4. Observational Platforms for Validation

11.5. Observational Viability and Simulations

11.6. DUT’s Unique Contribution

11.7. Relevance to Curvature Observables

11.8. Epistemological Implications

12. Deterministic Forecast for z >20

- M★ = 10⁶–10⁸ M☉

- F₍₃μm₎ = 0.1–1 mJ

- ∇S = (1.2 ± 0.3) × 10⁻¹⁴ J/m·K

- Γ₍decoh₎ = 0.92 ± 0.03

13. Falsifiable Observational Tests

13.1. Required Instrumentation

- JWST/NIRCam: Morphology (< 0.1")

- JWST/MIRI: 3μm flux verification

13.2. Discriminatory Signatures

- Smoking Gun: F₍₃μm₎ > 0.1 mJy without Ly

13.3. Mathematical Core

14. Cosmological Implications

- If confirmed: The DUT framework invalidates the inflationary paradigm’s stochastic predictions, particularly those involving random quantum perturbations as seeds for large-scale structure formation. Key works in this domain — including those by Guth [16], Linde [17], Mukhanov and Chibisov [19], and Baumann [20] — frame inflation as probabilistic and horizon-problem-driven. DUT, by contrast, posits that gravitational collapse and curvature arise from entropy gradients in a structural cavity, not inflationary noise.

- If refuted: A failure to detect the predicted entropy-driven proto-structures at redshift z>15z > 15z>15 would require revisiting the entropic formation module within the DUT Quantum Simulator v4.0 [1,2,3,4,10,12,21]. This recalibration could involve adjustments in the decoherence rate Γdecoh\Gamma_{\text{decoh}}Γdecoh, curvature scaling functions, or the thermodynamic potential Φ(r,t)\Phi(r,t)Φ(r,t) used to evolve geodesic trajectories.

- -

- If confirmed: Invalidates inflationary paradigm’s stochastic predictions

- -

- If refuted: Requires DUT modification below z = 15

15. Data Availability

- DUT Quantum Simulator v4.0: The full source code, parameter files, and documentation for the simulations presented in Section 7, Section 8 and Section 9 are archived and permanently hosted at Zenodo under DOI: https://zenodo.org/records/15871836 [1]. This simulator includes the implementation of non-singular potentials, entropy gradient calculations, and curvature evolution models compatible with the Dead Universe Theory (DUT).

- JWST z ≈ 16.7 Galaxy Candidates: Empirical high-redshift data used for comparison, including photometric redshifts, flux measurements, and morphological classifications, were obtained from the MAST Portal (Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes), specifically from the CEERS, JADES, and GLASS JWST programs[36,37,38].

- -

- DUT Simulator v4.0: https://zenodo.org/dut_simulator

- -

- JWST z ≈ 16.7 candidates: MAST Portal

16. Thermodynamic Horizon Collapse at Late Times

17. Geometric Signature of Asymmetric Collapse

18. Implications for JWST and Roman Telescope Missions

19. Legacy and Theoretical Outlook

20. Conclusion: Broader Cosmological Implications and Theoretical Perspective

References

- Jacobson, T. (1995). Thermodynamics of Spacetime: The Einstein Equation of State. Physical Review Letters, 75(7), 1260. [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, J. D. (1973). Black Holes and Entropy. Physical Review D, 7(8), 2333. [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S. W. (1975). Particle Creation by Black Holes. Communications in Mathematical Physics, 43(3), 199–220. [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, T. (2010). Thermodynamical Aspects of Gravity: New insights. Reports on Progress in Physics, 73(4), 046901. [CrossRef]

- Verlinde, E. (2011). On the Origin of Gravity and the Laws of Newton. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2011(4), 29. [CrossRef]

- Smolin, L. (2003). How Far Are We from the Quantum Theory of Gravity? arXiv:hep-th/0303185. [CrossRef]

- Rovelli, C. (1996). Relational Quantum Mechanics. International Journal of Theoretical Physics, 35(8), 1637–1678. [CrossRef]

- Wald, R. M. (2001). The Thermodynamics of Black Holes. Living Reviews in Relativity, 4(6). [CrossRef]

- Casini, H. (2008). Relative Entropy and the Bekenstein Bound. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 25(20), 205021. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J. (2024). Dead Universe Theory: From the End of the Big Bang to Beyond the Darkness and the Cosmic Origins of Black Holes. Open Access Library Journal, 11, e12143. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J. (2024). The “Dead Universe” Theory: Natural Separation of Galaxies Driven by the Remnants of a Supermassive Dead Universe. Natural Science, 16(6), 166–201. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J. (2024). Astrophysics of Shadows: The Dead Universe Theory — An Alternative Perspective on the Genesis of the Universe. Global Journal of Science Frontier Research, 24(A4), 33–47. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J. (2024). Dead Universe Theory (DUT): An Expanded Perspective on the New Cosmic Framework. OSF Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, J. (2024). The Cosmology of the Asymmetric Thermodynamic Retraction of the Cosmos (DUT). Academia.edu.

- Almeida, J. (2025). Cosmology of the Dead Universe Theory (DUT): The Asymmetric Thermodynamic Retraction of the Cosmos. Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: Physics and Space Science, 25(3).

- Almeida, J. (2025). DUT Quantum Simulator v4.4: Structural Core Update and χ-Particle Collapse Protocol. ExtractoDAO Technical Report.

- Almeida, J. (2025). DUT Quantum: The Computational Framework Enabling 180-Billion-Year Cosmological Simulations and Predicting High-Redshift Galaxies (z > 15). Preprints.org. [CrossRef]

- Dyson, F. J., Kleban, M., & Susskind, L. (2002). Disturbing Implications of a Cosmological Constant. Journal of High Energy Physics, 2002(10), 011. [CrossRef]

- Esteban-Gutiérrez, A., et al. (2024). On a Model of Variable Curvature that Mimics the Observed Universe Acceleration. arXiv:2410.08306. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W., et al. (2023). Revealing the Effects of Curvature on the Cosmological Models. Physical Review D, 107, 063509. [CrossRef]

- Sushkov, S. V., & Galeev, R. (2023). Cosmological Models with Arbitrary Spatial Curvature in the Theory of Gravity with Nonminimal Derivative Coupling. Physical Review D, 108, 044028. [CrossRef]

- Alestas, G., et al. (2024). Is Curvature-Assisted Quintessence Observationally Viable? Physical Review D, 110, 106010. [CrossRef]

- Rosa, J. G. (2019). The Flatness Problem and the Variable Physical Constants. Galaxies, 7(3), 77. [CrossRef]

- Harikane, Y., et al. (2023). A Search for H-band Dropout Galaxies at z ~ 13–17 with JWST. Astrophysical Journal, 951(2), 74.

- Boylan-Kolchin, M. (2023). Stress Testing ΛCDM with High-Redshift Galaxy Candidates. Nature Astronomy, 7, 946–951. [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, S. L., et al. (2023). CEERS Early Science: A Candidate z ~ 16 Galaxy in JWST Imaging. Astrophysical Journal Letters, 940(2), L55.

- Nojiri, S., & Odintsov, S. D. (2007). Introduction to Modified Gravity and Cosmology. International Journal of Geometric Methods in Modern Physics, 4(01), 115–146. [CrossRef]

- Sotiriou, T. P., & Faraoni, V. (2010). f(R) Theories of Gravity. Reviews of Modern Physics, 82(1), 451–497. [CrossRef]

- Cognola, G., et al. (2008). Extended f(R, L_m) Gravity with Logarithmic Corrections. Physical Review D, 77(4), 046009.

- De Felice, A., & Tsujikawa, S. (2010). f(R) Theories. Living Reviews in Relativity, 13(3). [CrossRef]

- Hassaine, M., & Martinez, C. (2007). Higher-dimensional Black Holes with a Conformally Invariant Maxwell Source. Physical Review D, 75(2), 027502. [CrossRef]

- Calcagni, G. (2010). Fractal Universe and Quantum Gravity. Physical Review Letters, 104(25), 251301. [CrossRef]

- Castellano, M., et al. (2022). Early Massive Galaxies at z > 10. Astrophysical Journal, 938(1), L15. [CrossRef]

- Atek, R., et al. (2023). Strong Lensing and Compact Galaxies at z > 13. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 675, A7.

- Boyett, K., et al. (2022). Evidence for Early Quenching of Star Formation. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 515(3), 3658–3674.

- Naidu, P., et al. (2022). Bright Galaxy Candidates at z > 11. Astrophysical Journal, 940(1), 54.

- Labbé, I., et al. (2023). JWST Discovery of Massive Galaxies at z > 10. Nature, 616(7955), 266–270.

- Silk, J. (2017). Feedback in Galaxy Formation. Astrophysical Journal, 839(1), L13.

- Bull, P., et al. (2016). Beyond ΛCDM: Problems, Solutions, and the Road Ahead. Physics of the Dark Universe, 12, 56–99. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. (1989). The Cosmological Constant Problem. Reviews of Modern Physics, 61(1), 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Loeb, A. (2014). The First Galaxies in the Universe. Princeton University Press.

- Abel, T., Bryan, G. L., & Norman, M. L. (2002). The Formation of the First Star in the Universe. Science, 295(5552), 93–98. [CrossRef]

- Springel, V., et al. (2005). Simulating the Joint Evolution of Quasars and Galaxies. Nature, 435(7042), 629–636. [CrossRef]

- Bak, D., & Rey, S. J. (2000). Cosmic Holography. Classical and Quantum Gravity, 17(15), L83–L89. [CrossRef]

- Visser, M. (1995). Lorentzian Wormholes: From Einstein to Hawking. Springer-Verlag.

- Poisson, E., & Israel, W. (1990). Internal Structure of Black Holes. Physical Review D, 41(6), 1796–1809. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, S. M. (2004). Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity. Addison-Wesley.

- Penrose, R. (2010). The Road to Reality: A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Vintage Books.

- Planck Collaboration. (2018). Planck 2018 Results. VI. Cosmological Parameters. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 641, A6. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).