1. Introduction

In recent years, socially assistive robots (SARs) have gained traction as promising tools for enhancing motivation, engagement, and learning outcomes in educational settings, particularly among younger learners and university students [

1,

2,

10]. While many existing robot-assisted learning systems emphasize verbal interaction and turn-based response logic, such approaches often neglect critical aspects of real-time fairness, first responder detection, and multimodal engagement, which are essential in team-based competitive learning contexts [

3,

33].

Group quizzes, competitions, and interactive games are widely used in classrooms to foster collaborative and experiential learning [

32,

34]. However, ensuring fairness particularly in determining which student responds first in a group is a longstanding challenge [

10,

35]. Traditional quiz systems often rely on sequential prompting, which may not fairly or effectively capture student intent. In response, recent advances in non-verbal sound-based input recognition have introduced novel opportunities for fair and intuitive responder detection using ambient sounds like claps, whistles or buzzing. Yet, few studies have rigorously combined such methods with educational robots in real-world classroom settings.

Equally important is the design of feedback and motivation strategies within robot-led systems [

26]. Research in Human–Robot Interaction (HRI) emphasizes the role of multimodal feedback including gestures, music, visual animations, and speech in creating more engaging and emotionally resonant learning experiences [

6,

27,

29]. Combining this with principles of gamification, such as those articulated in the Octalysis framework [

14], can activate psychological drives (e.g., accomplishment, curiosity, social influence) that are essential for sustaining learner motivation [

25].

To assess such systems meaningfully, validated scales like the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [

17], the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) [

18], and the Godspeed Questionnaire Series [

19] offer robust frameworks for evaluating perceived usefulness, enjoyment, competence, ease of use, behavioral intention, likeability and anthropomorphism of robots. The enjoyment and competence subscales of the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) were used to measure motivation, while the likeability and anthropomorphism subscales of the Godspeed Questionnaire were used as proxies for perceived social presence, as commonly applied in Human–Robot Interaction (HRI) studies.

This article presents the design and evaluation of a novel sound-driven robot quiz system that integrates non-verbal sound input detection with multimodal gamified feedback. The system is implemented on the Pepper robot using a custom Kotlin–Python architecture, employing cross-correlation-based sound recognition to determine first responders and QiSDK ASR for verbal answer input. We conducted a between-subject study comparing this system with a verbal-only baseline, and used subscales from TAM, IMI, and Godspeed to evaluate student responses. The study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: How does gamified multimodal feedback combined with sound-based first responder detection affect students’ perceived usefulness of a robot quiz system compared to verbal-only interaction?

RQ2: How does gamified multimodal feedback combined with sound-based first responder detection influence students’ perceived ease of use of a robot quiz system compared to verbal-only interaction?

RQ3: How does gamified multimodal feedback combined with sound-based first responder detection improve students’ motivation of a robot quiz system compared to verbal-only interaction?

RQ4: How does gamified multimodal feedback combined with sound-based first responder detection impact students perceived social presence measured via robot likeability and anthropomorphism compared to verbal-only interaction?

RQ5: How does gamified multimodal feedback combined with sound-based first responder detection influence students’ behavioral intention to use robot-assisted quiz system compared to verbal-only interaction?

By combining interaction fairness, motivational design, and system usability, our work contributes to the growing field of human-centered educational robotics, providing actionable design and evaluation guidelines for future robot-assisted learning environments.

2. Related Work

2.1. Educational Robots in Learning Environments

Social robots have become increasingly prevalent in educational contexts due to their ability to engage learners through embodied interaction, social presence, and adaptive communication strategies [

1]. Robots such as Pepper and NAO have been employed for vocabulary acquisition, collaborative tasks, and quiz-based learning in both K–12 and higher education settings [

2,

3,

24,

28]. These systems are particularly effective when they offer personalized feedback, group facilitation, and interactive quizzes, making them ideal for promoting motivation and attention in learners [

4,

36].

However, most existing robot-based learning systems rely on verbal interaction or sequential turn-taking [

5], which limits natural competition and does not scale well to multi-student group settings. This paper addresses this gap by integrating real-time sound-based responder detection to support fair, competitive participation.

2.2. Multimodal Interaction and Feedback in HRI

Multimodal feedback combining speech, gestures, audio cues, and visual signals has been shown to improve both task performance and user engagement in HRI systems [

6,

20]. In educational settings, multimodal robots increase children’s enjoyment and task recall [

7,

23], while gesture-augmented interactions with robots enhance social presence and perceived intelligence [

8]. Expressive feedback (e.g., music and dancing after correct answers) has also been linked to stronger emotional bonding and memory retention [

9,

21,

30].

Our system leverages these findings by combining gesture-based movement, auditory music cues, and verbal praise to deliver affective and motivational feedback during a quiz game. This creates a richer experience than unimodal systems and is further enhanced through sound-driven input recognition.

2.3. Fairness and First Responder Detection in Group-Based HRI

Fairness in group interactions is critical for sustained engagement and trust in educational technology [

10]. In multi-student contexts, the perception of fairness who gets to answer first, whether the robot treats all students equally has been shown to affect motivation and participation [

11]. Yet, few systems offer transparent or real-time responder detection based on ambient input.

Some prior work uses hand-raising detection or button presses, but these require additional hardware or physical constraints [

12]. Our approach using cross-correlation of non-verbal buzzer sounds enables a low-cost, intuitive, and fair way to identify who responded first, even in noisy environments. This supports a transparent fairness mechanism embedded in the game logic.

2.4. Gamification and the Octalysis Framework

Gamification is a key design strategy for improving learning outcomes by integrating motivational elements into educational systems [

13,

22,

31]. Frameworks like Octalysis [

14] provide a comprehensive structure for mapping features to psychological drives such as accomplishment, ownership, unpredictability, and social influence.

In robot-based learning, gamification has shown positive effects on user motivation, attitude, and acceptance [

15,

16]. However, few studies have applied a structured gamification framework like Octalysis to systematically design robot behaviors and feedback mechanisms. In this work, we explicitly align our system’s features (e.g., badges, team scores, expressive dance feedback) with Octalysis drives to maximize user motivation and engagement.

2.5. Evaluation Through Multiscale HRI Instruments

Validating educational robot systems requires multidimensional measurement tools. The Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) has been widely used to assess user attitudes and behavioral intention in HRI [

17]. The Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI) captures psychological factors such as enjoyment, competence, and pressure [

18], while the Godspeed Questionnaire Series evaluates robot anthropomorphism, animacy, likeability, and perceived intelligence [

19].

By combining these scales, this study ensures a holistic understanding of user perceptions toward both the robot system and its interaction design.

3. System Design

The proposed system enables a Pepper robot to facilitate a group-based quiz game by detecting the first responder using non-verbal sound inputs, verifying answers via verbal input, and providing multimodal feedback through gestures, music, and speech. The architecture was designed to ensure real-time interaction fairness, personalization, and engagement, with modular components for detection, interaction, and gamified feedback.

3.1. System Architecture

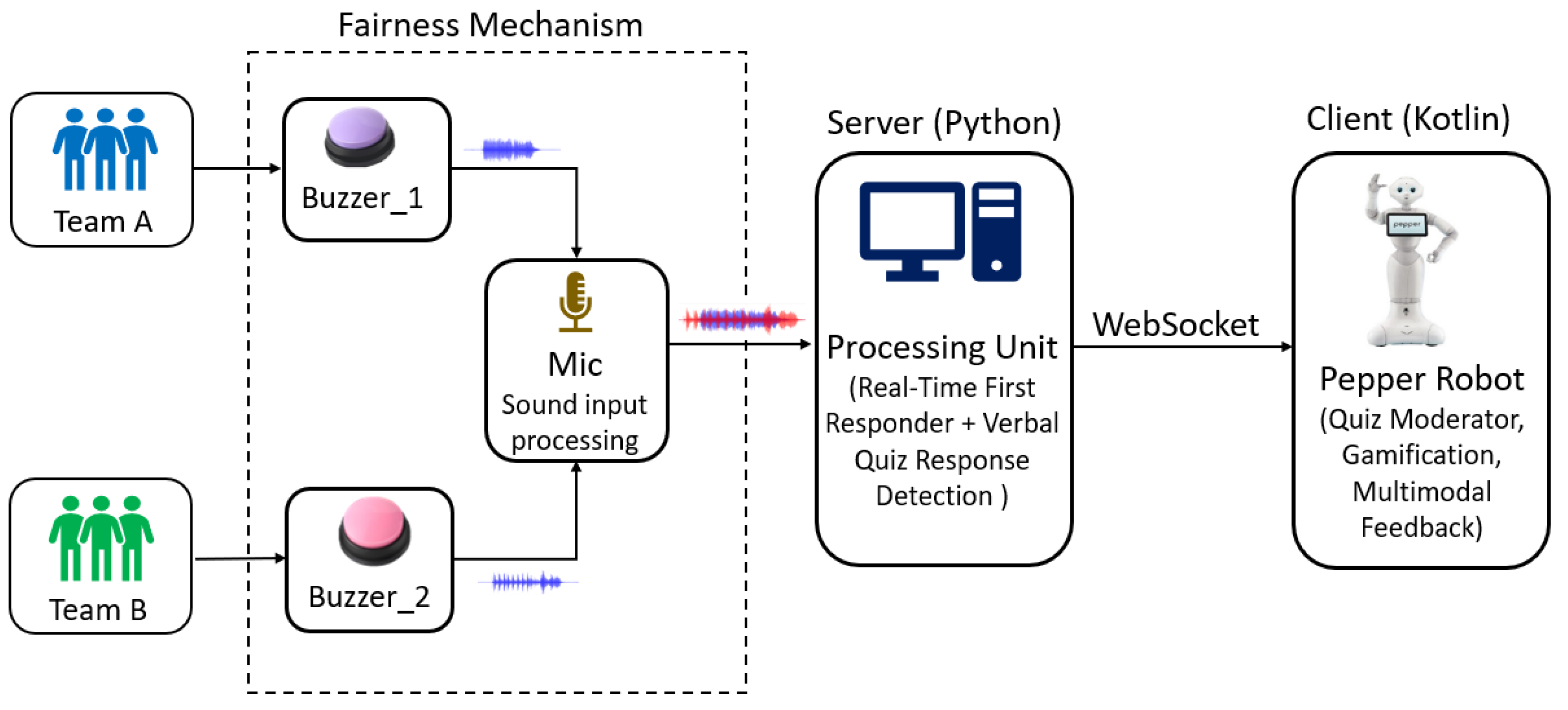

The system is composed of two main modules:

A Python-based backend responsible for sound order detection, template matching, and interaction logic

A Kotlin-based Pepper application using QiSDK ASR for speech recognition, gesture control, and verbal output

The sound detection module uses cross-correlation between live audio and pre-recorded templates to determine the first responder in real time. These templates are created using recordable buzzers, which allow students to generate any sound (e.g., clap, whistle, tap). Before each session, the system enables users to record and test sound templates to ensure robustness and minimize false detections.

The detected responder ID is then forwarded to the robot client via WebSocket, which manages the game flow and multimodal feedback as shown in

Figure 1.

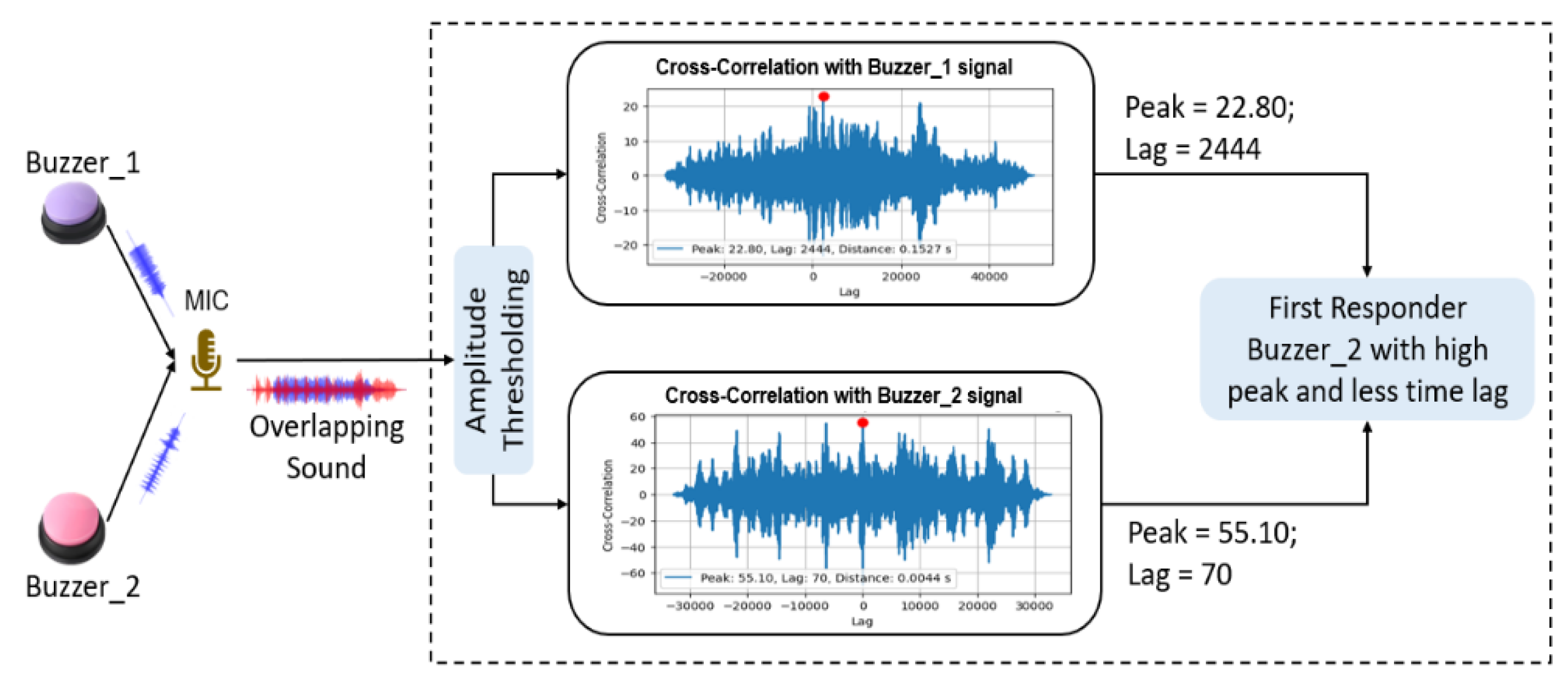

3.2. Sound-Based First Responder Detection

The system uses mono-channel microphone input to capture overlapping signals from the physical buzzers. After amplitude filtering, it performs cross-correlation between the incoming signal and the stored sound templates. The sound with the highest peak score and minimal lag is determined as the first responder. To ensure fairness both buzzers need to be placed in equal distance from the microphone as shown in

Figure 2.

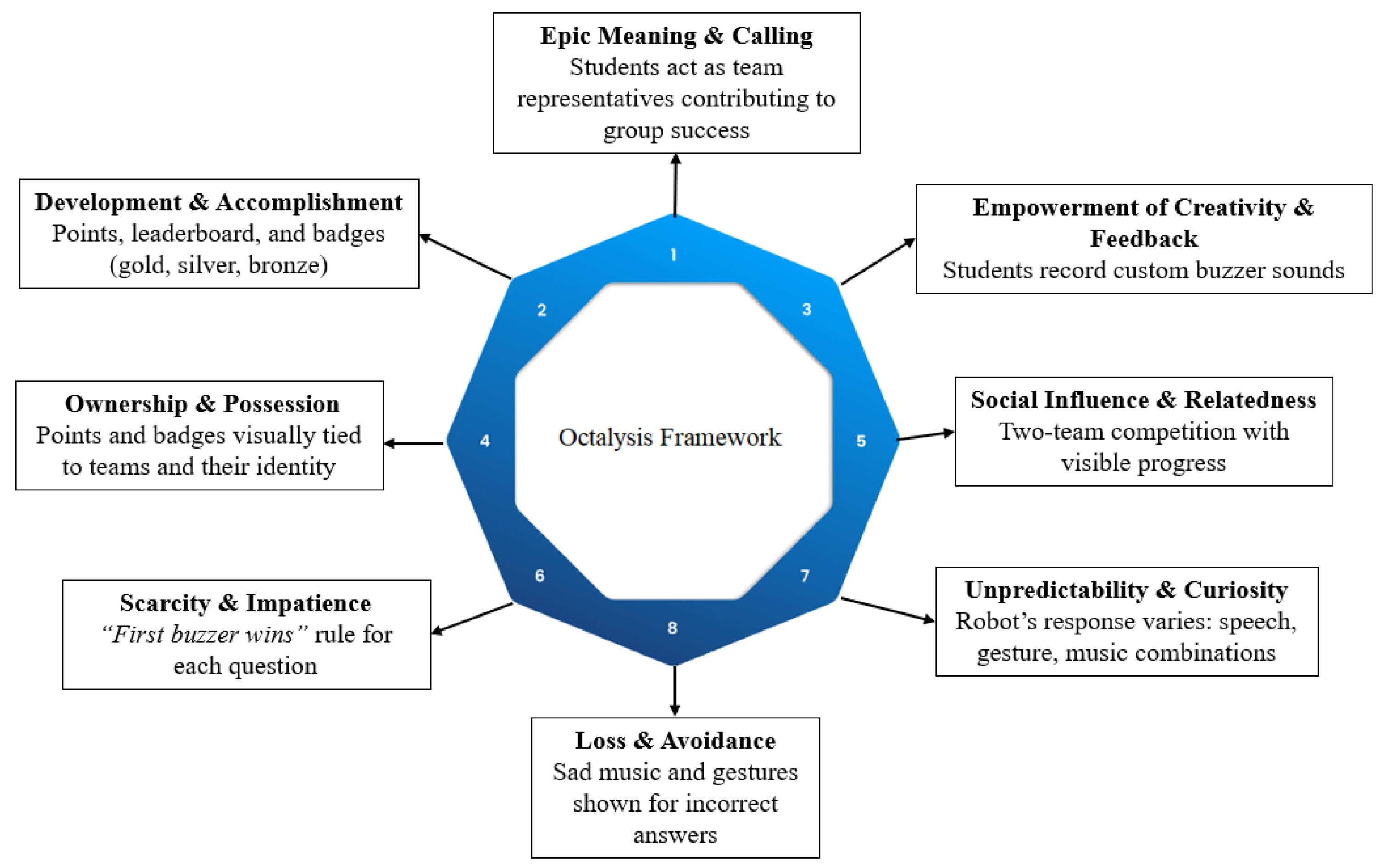

3.3. Gamification via Octalysis Integration

The design of the robot supported quiz game was guided by the Octalysis gamification framework, which comprises eight core motivational drives. Each drive was mapped to a corresponding system feature to stimulate student engagement and emotional investment throughout the learning interaction as shown in

Figure 3.

Core Drive 1: Epic Meaning & Calling was addressed by assigning students to teams, enabling them to act as representatives contributing to their group’s success. This framing reinforced a sense of purpose beyond individual performance.

Core Drive 2: Development & Accomplishment was activated via a real-time scoring system with point accumulation and visible badges (gold, silver, bronze), providing immediate feedback on performance and fostering a sense of progress.

Core Drive 3: Empowerment of Creativity & Feedback emerged through the use of custom recordable buzzers. Students were allowed to choose their own buzzer sounds (e.g., whistling or clapping), offering a layer of creative expression and autonomy.

Core Drive 4: Ownership & Possession was reinforced as teams accumulated points and earned badges that were persistently associated with their identity. This ownership encouraged students to care about outcomes and feel invested in the session.

Core Drive 5: Social Influence & Relatedness was central to the system, as gameplay occurred in two competing teams. Peer motivation, collaboration, and comparison drove engagement in both intra- and inter-team dynamics.

Core Drive 6: Scarcity & Impatience was supported by implementing a real-time “first responder” mechanic, where only the fastest buzz-in was recognized, introducing urgency and time pressure.

Core Drive 7: Unpredictability & Curiosity was realized by varying the robot’s multimodal responses. Depending on correctness, Pepper provided unpredictable combinations of speech, music, and gestures (e.g., dancing, clapping, head movements), maintaining a sense of novelty.

Core Drive 8: Loss & Avoidance was triggered through negative feedback, such as sad music and gestures when a question was answered incorrectly. This emotional contrast motivated students to perform better in the next round.

3.4. Feedback and Interaction Modalities

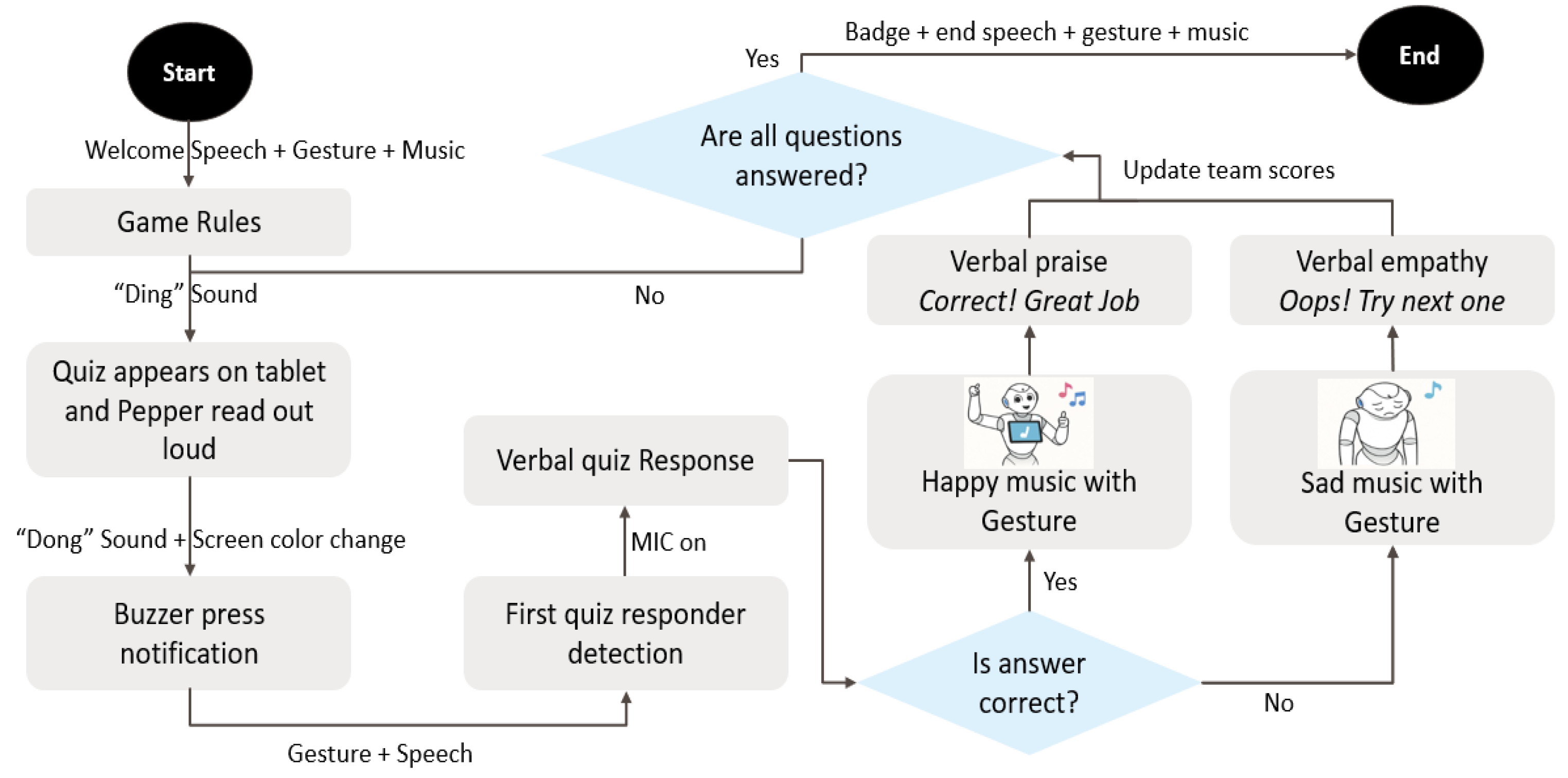

The quiz game algorithm flowchart shown in

Figure 4.

At the beginning of the session, Pepper initiates interaction by greeting the participants using a combination of speech, gesture, and background music to establish rapport. It then verbally explains the rules of the quiz game and awaits participant confirmation to proceed. Upon receiving confirmation, Pepper plays a brief “Ding” sound to signal the start of the game. A quiz question is displayed on the robot’s chest-mounted tablet, and Pepper reads the question aloud while simultaneously playing a “Dong” sound and altering the tablet screen color to prompt participants to activate their buzzers.

Once the system recognizes the first responder through sound-based detection, Pepper verbally announces the team or individual who responded first, accompanied by a pointing gesture toward the identified participant(s). Subsequently, the robot listens for a verbal answer. Upon recognition of the verbal response and determination of its correctness, Pepper delivers multimodal feedback consisting of speech, gestures, and short music cues, and updates the corresponding team’s score.

This process continues iteratively for each quiz question. Upon completion of all questions, Pepper announces the winning team, delivers congratulatory feedback through a celebratory dance and upbeat music, and awards visual badges as a form of recognition and motivation.

4. Experimental Design

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed sound-driven multimodal robot quiz system, a between-subject experimental study was conducted with two conditions: a verbal-only baseline and the proposed gamified system. The primary objective was to examine how multimodal feedback and sound-based first responder detection influenced students’ perceptions of usefulness, ease of use, motivation, and social acceptance of the robot.

4.1. Study Design and Conditions

The control group interacted with a version of the robot that asked quiz questions verbally and received verbal responses from participants in a fixed sequential order. Feedback in this condition was limited to simple verbal statements such as “Correct” or “Incorrect,” without any additional gestures, music, or rewards.

In contrast, the experimental group engaged with the enhanced system that included non-verbal sound-based input, real-time first responder detection using cross-correlation, gesture and music feedback, a team-based point system, and visual badge rewards as shown in

Figure 5. Each student in the experimental group used a physical recordable buzzer, which allowed them to record and use a personalized non-verbal sound for the competition. The system provided testing functionality prior to the game to ensure that the sound templates were accurately recognized and differentiated.

4.2. Participants

A total of thirty-two undergraduate students (N = 32), aged between 19 and 24 years and enrolled in a programming course at a German university of applied sciences, voluntarily participated in the study. Participants (7 female, 25 male) were randomly assigned to either the control group (n = 16) or the experimental group (n = 16). Prior to the quiz session, participants were introduced to the robot and received brief instructions on the interaction procedures. For the experimental group, additional time was allocated for recording and testing individual buzzer sounds to ensure system accuracy and participant familiarity with the setup.

4.3. Procedure and Evaluation Criteria

Each group participated in a robot-led 25-minute quiz session consisting of eight multiple-choice questions. The robot, implemented using QiSDK and autonomously moderated the game. After each question, the robot listened for answers and provided feedback appropriate to the group’s condition. The interaction duration and question difficulty were kept consistent across both groups.

Immediately after the session, participants completed a post-interaction questionnaire consisting of selected subscales from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI), and the Godspeed Questionnaire Series. Specifically, the TAM subscales measured perceived usefulness, ease of use, and behavioral intention; the IMI captured enjoyment, competence as a motivation; and the Godspeed scales measured likeability and anthropomorphism as a social presence of the robot. All questionnaire items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 5 (“Strongly agree”).

4.4. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using independent samples t-tests to compare the mean scores between the control and experimental groups. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each subscale to confirm internal consistency. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were also computed to quantify the magnitude of observed differences. This design allowed for a direct comparison of the impact of the proposed system on user perception, motivation, and acceptance, using validated multidimensional evaluation instruments.

5. Results

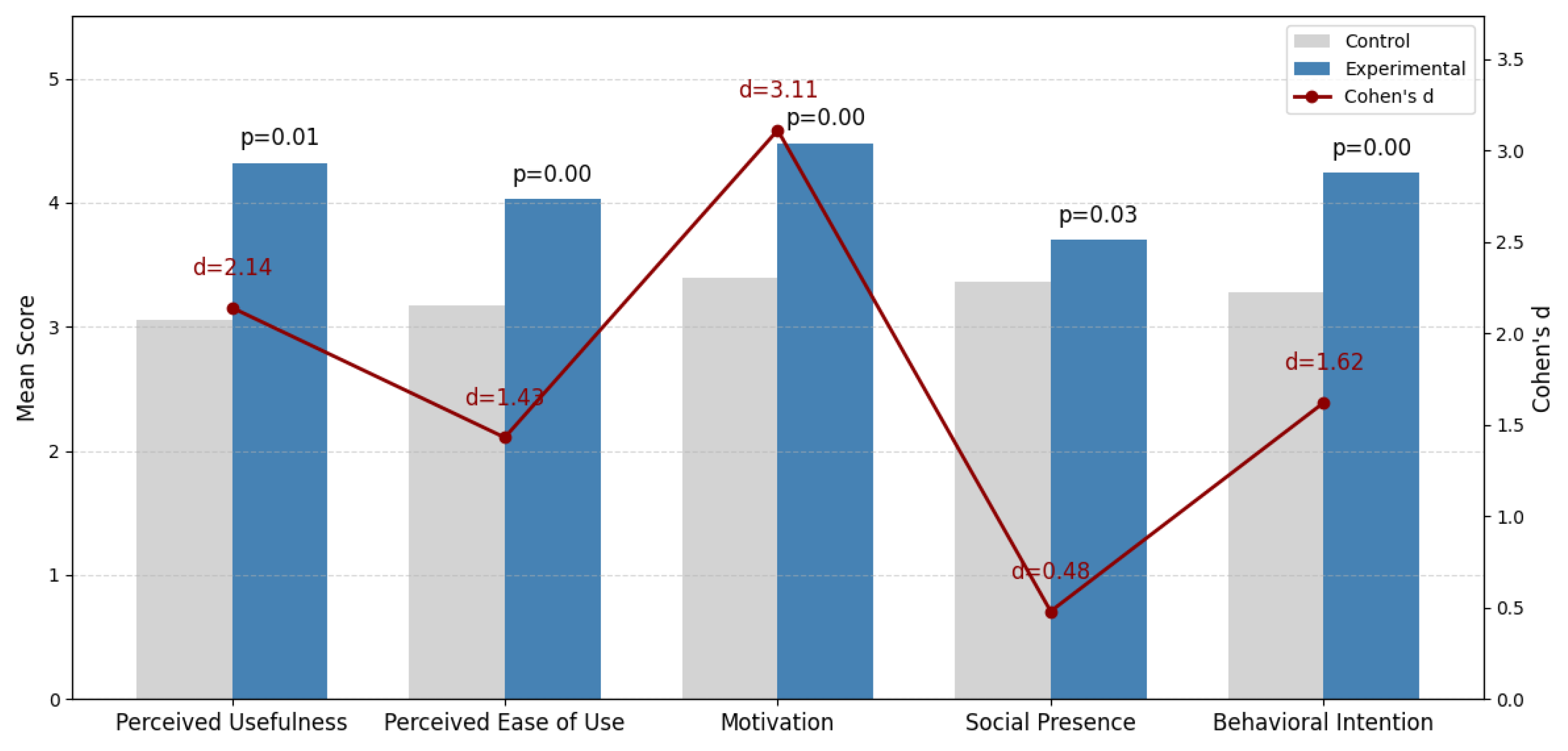

This section presents the results of the comparative evaluation between the control (verbal-only) and experimental (sound-driven, multimodal) groups, structured around the five research questions. Independent samples t-tests were conducted for each subscale, and effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d to assess the magnitude of group differences as shown in

Figure 6.

RQ1 examined how gamified multimodal feedback combined with sound-based first responder detection affects students’ perceived usefulness of the robot quiz system. The results revealed a statistically significant difference in perceived usefulness between the control group (M = 3.05, SD = 0.81) and the experimental group (M = 4.32, SD = 0.83), t(30) = 6.05, p = 0.01. The effect size was large (Cohen’s d = 2.14), indicating a substantial improvement in perceived usefulness due to the integration of multimodal feedback and fairness mechanisms.

RQ2 addressed the effect of the proposed system on perceived ease of use. Students in the experimental group reported significantly higher ease of use (M = 4.03, SD = 0.92) compared to those in the control group (M = 3.17, SD = 0.71), t(30) = 4.07, p < 0.001. The observed effect size was large (Cohen’s d = 1.43), suggesting that the inclusion of intuitive input mechanisms and expressive feedback positively impacted the usability of the system.

RQ3 focused on students’ motivation, as measured by the Interest/Enjoyment and Competence subscales of the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (IMI). The experimental group reported significantly greater motivation (M = 4.48, SD = 0.34) than the control group (M = 3.39, SD = 0.36), t(30) = 6.96, p < 0.001. The effect size was extremely large (Cohen’s d = 3.11), indicating that the gamified and multimodal features contributed strongly to user motivation and engagement during the quiz experience.

RQ4 explored the impact of the system on students’ perception of the robot’s social presence measured by the Likeability and Anthropomorphism subscales of the Godspeed Questionnaire, which serve as validated indicators of perceived social presence in HRI research that showed a significant difference between groups, with the experimental group scoring higher (M = 3.70, SD = 0.62) than the control group (M = 3.36, SD = 0.70), t(30) = 2.17, p = 0.03. Although the effect size was moderate (Cohen’s d = 0.48), the result suggests that multimodal feedback including gestures, music, and expressive animations enhanced the robot’s perceived social interactivity.

RQ5 investigated students’ behavioral intention to use the system in the future. The experimental group exhibited significantly greater behavioral intention (M = 4.24, SD = 0.83) compared to the control group (M = 3.28, SD = 0.80), t(30) = 4.58, p < 0.001. The corresponding effect size was large (Cohen’s d = 1.62), indicating that the integration of fair first responder detection and engaging feedback mechanisms positively influenced students’ willingness to use such systems in future educational settings.

Furthermore, the non-verbal sound-driven first responder detection mechanism was perceived as fair, as no complaints were recorded during the experiment. Several students noted in their qualitative feedback that they had verified the fairness of the detection system using their mobile phone cameras and confirmed its reliability. In contrast, some students reported that the robot occasionally required multiple attempts to recognize verbal responses from female participants, whereas verbal inputs from male students particularly those with stronger vocal projection were recognized more readily. Although such issues were infrequent, with only one or two complaints observed, they were noted in the qualitative responses. These findings suggest that while the system effectively ensures fairness in non-verbal sound-based detection, minor inconsistencies in verbal recognition remain and may warrant further refinement.

Together, these results demonstrate that the proposed sound-driven, gamified multimodal robot quiz system outperforms the verbal-only baseline across all evaluated dimensions, with particularly strong gains in perceived usefulness, enjoyment, and behavioral intention.

6. Discussion

This study set out to evaluate a sound-driven, gamified multimodal robot quiz system by comparing it to a verbal-only baseline across five user perception dimensions. The results consistently demonstrated that the proposed system significantly enhanced learners’ perceptions of usefulness, ease of use, motivation, social presence, and behavioral intention to use the robot in future educational contexts.

The substantial improvement in perceived usefulness (RQ1) suggests that integrating first responder detection with engaging feedback mechanisms enables the robot to function as a more efficient and meaningful learning facilitator. These findings align with earlier work emphasizing that robot systems designed with fairness and responsiveness are more likely to be adopted and trusted in collaborative learning environments [

1,

2]. The large effect size (Cohen’s d = 2.14) indicates that the system’s fairness in determining which team member answered first combined with expressive reward feedback was a design enhancement.

Regarding ease of use (RQ2), students in the experimental group found the system more intuitive and comfortable to interact with, likely due to the familiar and low-friction nature of the recordable buzzers and the system’s seamless response flow. This confirms prior observations that physical interaction, when augmented with multimodal feedback, can reduce cognitive load and increase perceived usability in robot-based learning systems [

3]. Despite the added complexity of sound calibration, the experimental group experienced significantly higher usability scores, highlighting the importance of intuitive design in multimodal HRI.

In terms of user motivation (RQ3), The combined motivation score based on enjoyment and competence showed the most pronounced difference of all subscales (Cohen’s d = 3.11), affirming the strong motivational impact of gamified multimodal features. This reinforces previous findings that game elements such as music, animations, team-based rewards, and choice (e.g., custom buzzer sounds) can activate core motivational drives such as empowerment, social influence, and accomplishment, especially when aligned with frameworks like Octalysis [

4]. The result suggests that motivation, more than any other factor, may be the key determinant of students’ engagement with educational robots in competitive settings.

The enhancement in social presence based on likeability and anthropomorphism (RQ4), although with a smaller effect size (d = 0.48), indicates that multimodal interaction made the robot feel more socially intelligent and present. This finding echoes recent literature emphasizing that social cues such as gestures, expressive feedback, and turn-taking can significantly improve learners’ emotional connection to robots [

6]. It also suggests that even subtle multimodal enhancements can positively affect the relational aspects of human–robot interaction.

Finally, the improvement in behavioral intention to use the system in the future (RQ5) underscores the combined effect of all previous dimensions. When users perceive a system as useful, easy to use, enjoyable, and socially engaging, their likelihood of continued use increases dramatically [

7]. The experimental group’s higher behavioral intention scores (Cohen’s d = 1.62) suggest that integrating fairness mechanisms and multimodal feedback into robot systems may not only improve learning experience in the short term but also contribute to long-term user acceptance and adoption in educational settings.

Additionally, qualitative feedback from participants further validated the system’s perceived fairness and social engagement. Several students reported verifying the first responder detection fairness by reviewing mobile phone recordings, reinforcing trust in the system’s integrity. Others commented positively on the robot’s expressive feedback and team-based structure, noting it made the activity feel more interactive and competitive. However, some participants particularly female students mentioned occasional issues with verbal recognition, highlighting a need for more inclusive ASR tuning. These qualitative observations complement the quantitative findings, offering deeper insights into the user experience and perceived reliability of the system

Taken together, these findings provide strong empirical support for the design of robot learning systems that are not only functionally robust but also fair, emotionally engaging, and motivationally rich. The study bridges gaps in current educational robotics research by combining technical sound detection, game mechanics design, and validated multidimensional evaluation thus offering a replicable and extensible model for future robot-assisted learning applications.

7. Conclusion, Limitations, and Future Work

This study introduced a sound-driven, gamified multimodal robot quiz system designed to enhance fairness, motivation, and engagement in group-based educational settings. By integrating real-time first responder detection through cross-correlation of user-defined buzzer sounds and combining this with expressive robot feedback including gestures, music, and scoring the system enabled a more immersive and equitable learning experience compared to traditional verbal-only interaction. A between-subject experimental study demonstrated that students who interacted with the proposed system reported significantly higher perceived usefulness, ease of use, motivation, social presence, and behavioral intention. The most notable effect was observed in the motivation subscale, highlighting the motivational potential of Octalysis-aligned game mechanics.

Despite these promising results, the study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small (n = 32), limiting the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. While significant effects were observed, larger and more diverse samples across multiple institutions are needed to confirm robustness. Second, the evaluation focused solely on short-term perceptions and did not measure actual learning outcomes or retention. Third, the cross-correlation-based first responder detection, though robust in our controlled setting, may be sensitive to background noise or mic placement variations in uncontrolled environments. Additionally, observed gender disparities in ASR accuracy warrant algorithmic refinement. Lastly, the system was tested with university students in a single cultural context, which may influence social presence perceptions and user engagement styles.

Future work will address these limitations by conducting longitudinal studies that assess learning gains, integrating adaptive difficulty mechanisms, and deploying the system across diverse cultural and educational settings. Additionally, technical refinements such as noise filtering, automated sound template tuning, and multimodal input fusion (e.g., combining sound with motion detection) will be explored to further improve robustness and usability. Expanding the system for cooperative gameplay, emotion-aware feedback, and real-time analytics could also enhance its effectiveness in real-world classroom environments.

Overall, this work presents a meaningful step toward designing robot systems that are not only functional but also fair, socially engaging, and motivationally compelling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.T. and R.T.; methodology, R.T.; software, R.T.; validation, R.T., R.T. and R.T.; formal analysis, N.P.; investigation, R.T.; resources, R.T.; data curation, R.T.; writing—original draft preparation, R.T.; writing—review and editing, R.T.; visualization, R.T.; supervision, N.P.; project administration, R.T.; funding acquisition, N.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article processing charge (APC) was funded by the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The research data supporting the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to project privacy reason.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Belpaeme, T.; Kennedy, J.; Ramachandran, A.; Scassellati, B.; Tanaka, F. Social robots for education: A review. Science Robotics 2018, 3, eaat5954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papakostas, G.A.; Sidiropoulos, G.K.; Papadopoulou, C.I.; Vrochidou, E.; Kaburlasos, V.G.; Papadopoulou, M.T.; Holeva, V.; Nikopoulou, V.-A.; Dalivigkas, N. Social Robots in Special Education: A Systematic Review. Electronics 2021, 10, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stasolla, F.; Curcio, E.; Borgese, A.; Passaro, A.; Di Gioia, M.; Zullo, A.; Martini, E. Educational Robotics and Game-Based Interventions for Overcoming Dyscalculia: A Pilot Study. Computers 2025, 14, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui-Ru, H. Empowering Parents and Teachers to Support Children’s Learning through AI-based and Robotic Learning Companions. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA '25). Association for Computing Machinery 2025, Article 836. Yokohama, Japan, 26 April 2025–1 May 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, H.; Lange, A.L.; Hafner, V.V.; et al. How adaptive social robots influence cognitive, emotional, and self-regulated learning. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 6581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, I.; Martinho, C.; Paiva, A. Social robots for long-term interaction: A survey. International Journal of Social Robotics 2013, 5, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Ishiguro, H.; Sumioka, H. A Multimodal System for Empathy Expression: Impact of Haptic and Auditory Stimuli. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA '25). Association for Computing Machinery, Article 44. New York, NY, USA, 26 April 2025–1 May 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Baxter, P.; Belpaeme, T. Comparing Robot Embodiments in a Guided Discovery Learning Interaction with Children. Int J Soc Robotics 2015, 7, 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delecluse, M.; Sanchez, S.; Cussat-Blanc, S.; Schneider, N.; Welcomme, J.-B. High-level behavior regulation for multi-robot systems. In Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 2014 Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation (GECCO Comp '14). Association for Computing Machinery, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 12–16 July 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.L.; Trafton, G.; McCurry, J.M.; Thomaz, A.L. Unfair! Perceptions of Fairness in Human-Robot Teams. In Proceedings of the 2021 30th IEEE International Conference on Robot & Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–12 August 2021; pp. 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, O.; Hok, H.; Shaw, A.; et al. When it is ok to give the Robot Less: Children’s Fairness Intuitions Towards Robots. Int J of Soc Robotics 2023, 15, 1581–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas-Martínez, Á.-G.; Cunillé-Rodríguez, J.; Aquino-López, E.; García-Moreno, A.-I. Multimodal Human–Robot Interaction Using Gestures and Speech: A Case Study for Printed Circuit Board Manufacturing. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dichev, C.; Dicheva, D. Gamifying education: what is known, what is believed and what remains uncertain: a critical review. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 2017, 14, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Y.K. Actionable Gamification: Beyond Points, Badges, and Leaderboards; Octalysis Group, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Saerbeck, M.; Schut, T.; Bartneck, C.; Janse, M.D. Expressive robots in education: varying the degree of social supportive behavior of a robotic tutor. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI '10). Association for Computing Machinery, Atlanta, GA, USA, 10–15 April 2010; pp. 1613–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravandi, B.S. Gamification for Personalized Human-Robot Interaction in Companion Social Robots. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction Workshops and Demos (ACIIW), Glasgow, UK, 15 September 2024; pp. 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the TAM: Four longitudinal studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior; Springer, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bartneck, C.; Kulic, D.; Croft, E.; Zoghbi, S. Measurement instruments for the anthropomorphism, animacy, likeability, perceived intelligence, and perceived safety of robots. International Journal of Social Robotics 2009, 1(1), 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AGoldman, E.J.; Baumann, A.; Poulin-Dubois, D. Pre-schoolers’ anthropomorphizing of robots: Do human-like properties matter? Frontiers in Psychology 2023, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Kragness, H.E.; Ullah, F.; Chan, E.; Moses, R.; Cirelli, L.K. Tiny dancers: Effects of musical familiarity and tempo on children's free dancing. Developmental psychology 2022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J.; Sarsa, H. Does gamification work? A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. In Proceedings of the IEEE 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 3025–3034), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Qi, W.; Chen, J.; Yang, C.; Sandoval, J.; Laribi, M.A. Recent advancements in multimodal human–robot interaction. Frontiers in Neurorobotics 2023, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fung, K.Y.; Lee, L.H.; Sin, K.F.; Song, S.; Qu, H. Humanoid robot-empowered language learning based on self-determination theory. Education and Information Technologies 2024, 29(14), 18927–18957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, E.; Vanderborght, B.; Roesler, O.; Cao, H.-L. A Reinforcement Learning Based Cognitive Empathy Framework for Social Robots. International Journal of Social Robotics 2020, 13(5), 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, A. Social Robots in Education for Long-Term Human-Robot Interaction: Socially Supportive Behaviour of Robotic Tutor for Creating Robo-Tangible Learning Environment in a Guided Discovery Learning Interaction. ECS Transactions 2022, 107(1), 12389–12403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacula, A.; Knight, H. Dancing with Robots at a Science Museum: Coherent Motions Got More People To Dance, Incoherent Sends Weaker Signal. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Symposium on Technological Advances in Human-Robot Interaction, Boulder, CO, USA, 9–10 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschmanner, M.; Gross, S.; Krenn, B.; Neubarth, F.; Trapp, M.; Vincze, M. Grounded Word Learning on a Pepper Robot. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Intelligent Virtual Agents, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 5–8 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Theodotou, E. Dancing With children or dancing for children? Measuring the effects of a dance intervention in children’s confidence and agency. Early Child Development and Care 2025, 195(1–2), 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Hu, Y.; Nechyporenko, N.; Kim, D.; Talbott, W.; Zhang, J. EMOTION: Expressive Motion Sequence Generation for Humanoid Robots with In-Context Learning. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2024, 10, 7699–7706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripathy, A.; Bobu, A.; Li, Z.; Sreenath, K.; Brown, D.S.; Dragan, A.D. Teaching Robots to Span the Space of Functional Expressive Motion. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Kyoto, Japan, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 13406–13413. [Google Scholar]

- Louie, W.-Y.G.; Nejat, G. A Social Robot Learning to Facilitate an Assistive Group-Based Activity from Non-expert Caregivers. International Journal of Social Robotics 2020, 12(5), 1159–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, D.; Tu, Y.-F.; Hwang, G.-J.; Hu, L.; Chen, Y. Engaging Young Students in Effective Robotics Education: An Embodied Learning-Based Computer Programming Approach. Journal of Educational Computing Research 2023, 62(2), 532–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.-F.; Lian, L.-W.; Zhao, J.-H. Developing a gamified artificial intelligence educational robot to promote learning effectiveness and behaviour in laboratory safety courses for undergraduate students. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education 2023, 20(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutul, R.; Buchem, I.; Jakob, A.; Pinkwart, N. Enhancing Learner Motivation, Engagement, and Enjoyment Through Sound-Recognizing Humanoid Robots in Quiz-Based Educational Games. In Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavo, F.; Campitiello, L.; Todino, M.D.; Di Tore, P.A. Educational Robots, Emotion Recognition and ASD: New Horizon in Special Education. Education Sciences 2024, 14(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).