Submitted:

16 July 2025

Posted:

17 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Animal Feeds

2.2. Performance Measurements

2.3. Water Efficiency Measures

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

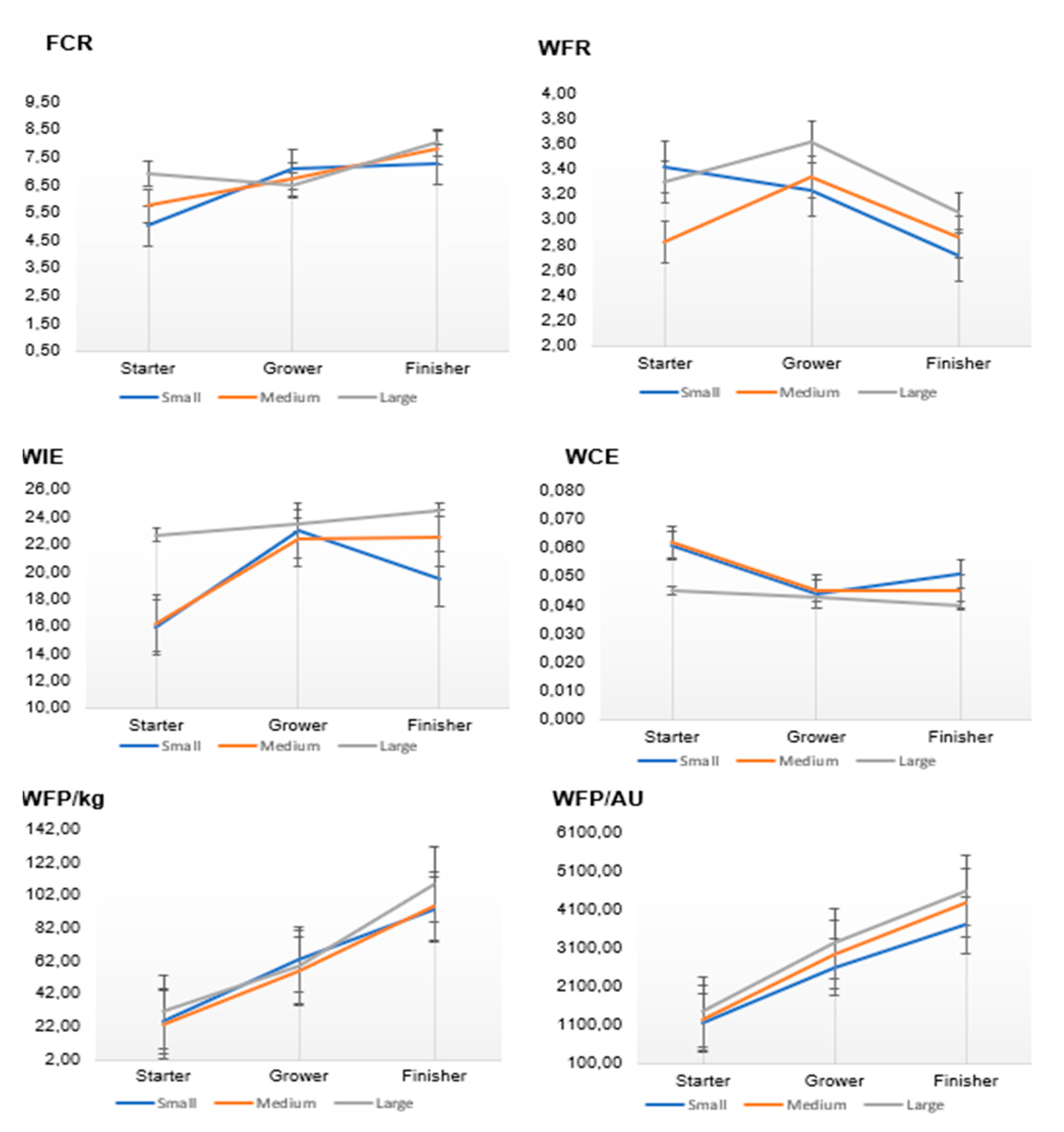

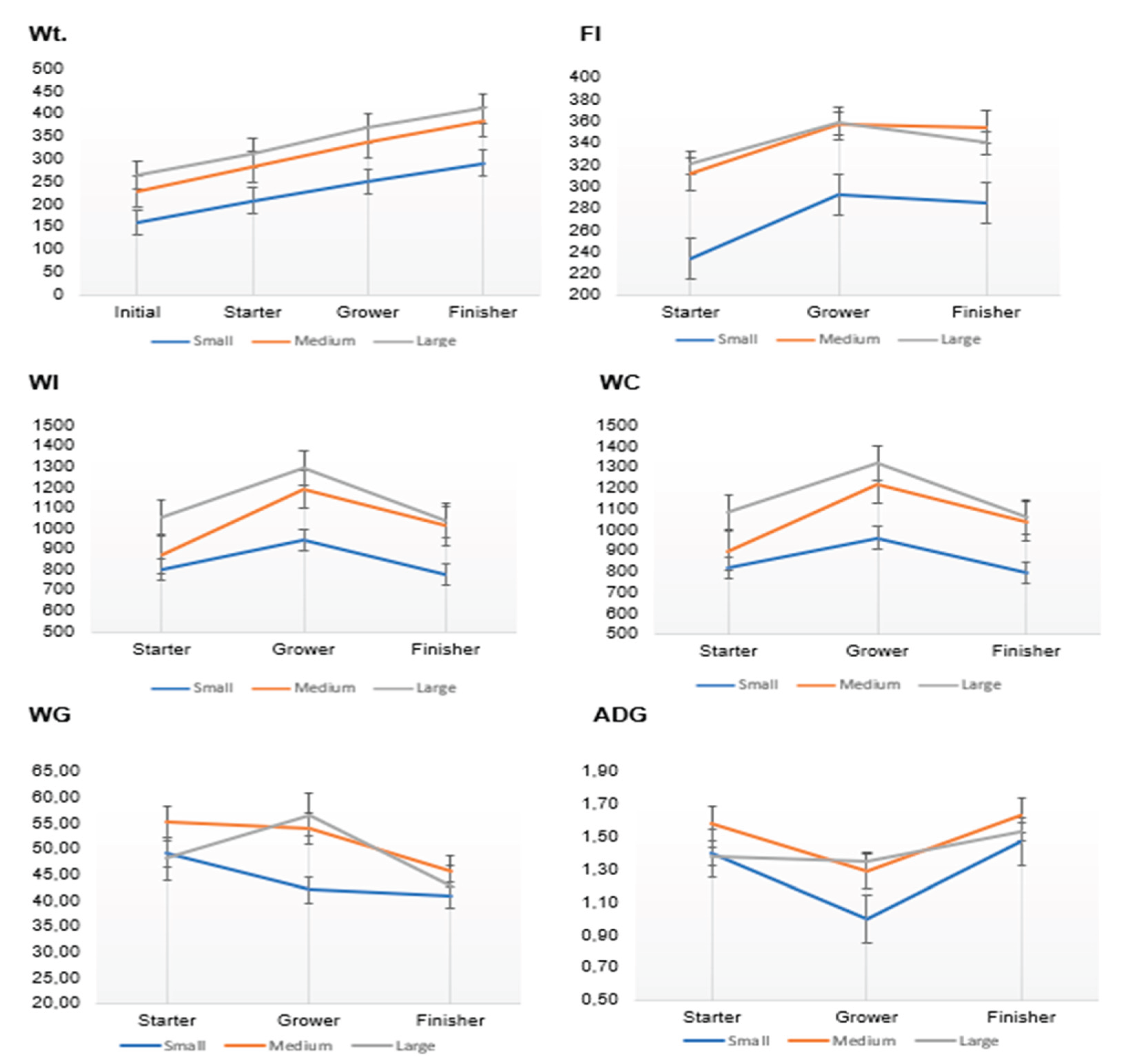

3.1. Growth Performance, Feed and Water Intake

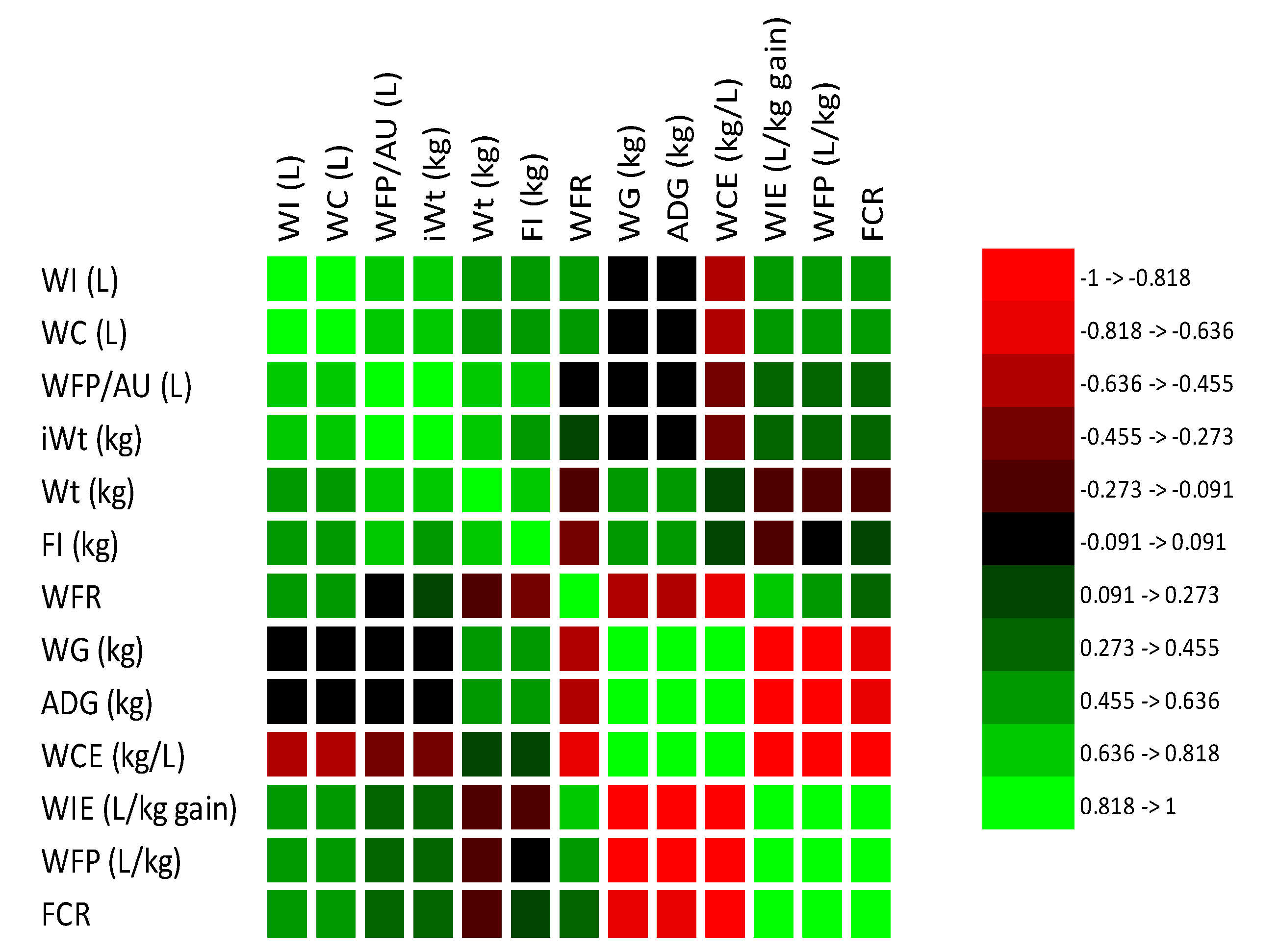

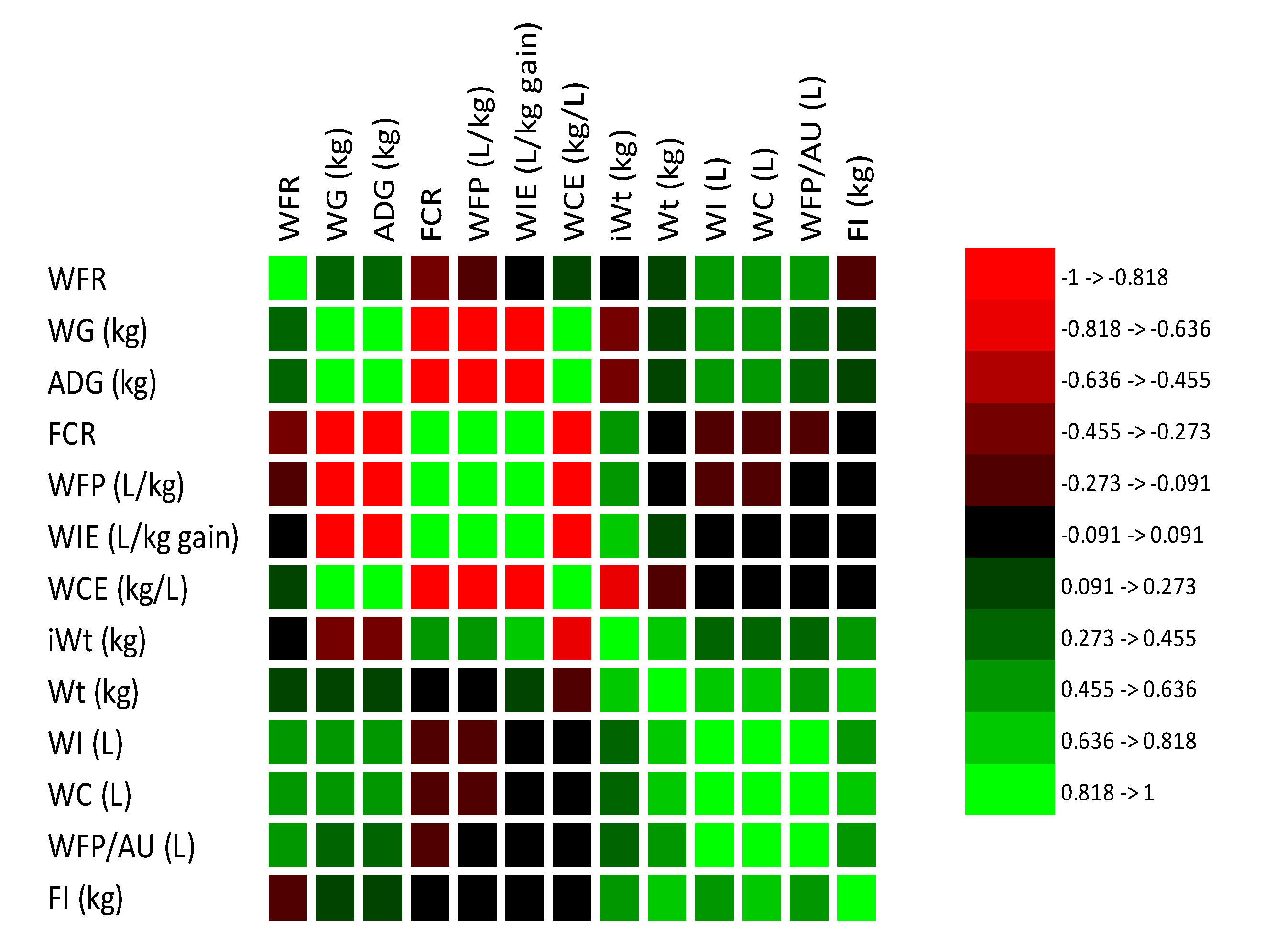

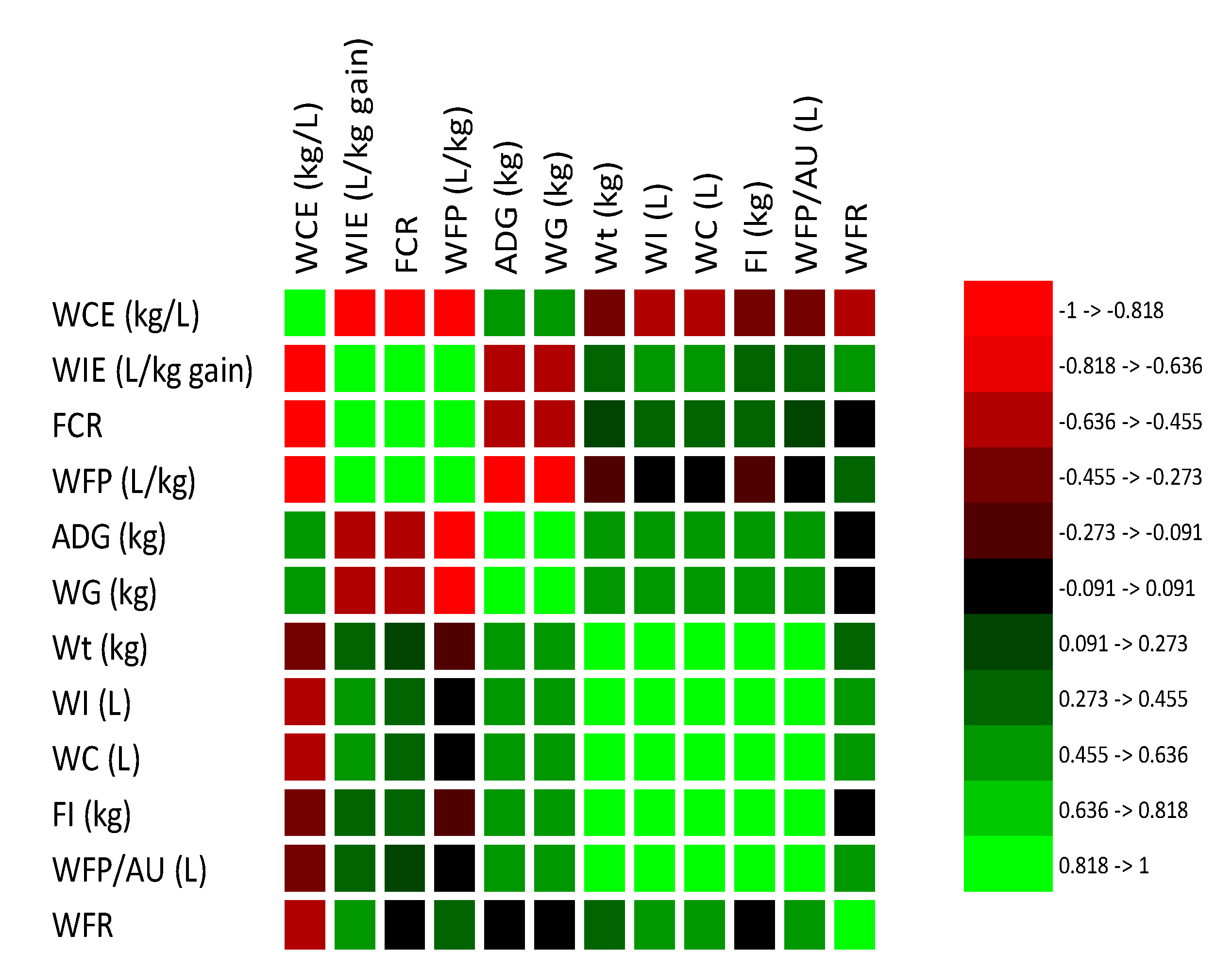

3.2. Correlations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nkadimeng M, Van Marle-Köster E, Nengovhela NB, Ramukhithi FV, Mphaphathi ML, Rust JM, et al. Assessing Reproductive Performance to Establish Benchmarks for Small-Holder Beef Cattle Herds in South Africa. Animals [Internet]. 2022 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Feb 9];12(21):3003. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/12/21/3003.

- Scholtz M, Maiwashe A, Neser F, Theunissen A, Olivier W, Mokolobate M, et al. Livestock breeding for sustainability to mitigate global warming, with the emphasis on developing countries. SA J An Sci [Internet]. 2013 Oct 22 [cited 2025 Feb 10];43(3):269. Available from: http://www.ajol.info/index.php/sajas/article/view/95630.

- Barbero RP, Malheiros EB, Nave RLG, Mulliniks JT, Delevatti LM, Koscheck JFW, et al. Influence of post-weaning management system during the finishing phase on grasslands or feedlot on aiming to improvement of the beef cattle production. Agricultural Systems [Internet]. 2017 May [cited 2025 Feb 10];153:23–31. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0308521X16305170.

- Lalman D, Holder A. NUTRIENT REQUIREMENTS OF BEEF CATTLE. 2014;1–24.

- Mpandeli S, Naidoo D, Mabhaudhi T, Nhemachena C, Nhamo L, Liphadzi S, et al. Climate Change Adaptation through the Water-Energy-Food Nexus in Southern Africa. IJERPH [Internet]. 2018 Oct 19 [cited 2025 Feb 9];15(10):2306. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/15/10/2306.

- Pahlow M, Snowball J, Fraser G. Water footprint assessment to inform water management and policy making in South Africa. WSA [Internet]. 2015 Apr 21 [cited 2025 Feb 10];41(3 April). Available from: https://watersa.net/article/view/10972.

- Meza I, Eyshi Rezaei E, Siebert S, Ghazaryan G, Nouri H, Dubovyk O, et al. Drought risk for agricultural systems in South Africa: Drivers, spatial patterns, and implications for drought risk management. Science of The Total Environment [Internet]. 2021 Dec [cited 2025 Feb 10];799:149505. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0048969721045794.

- Wagner JJ, Engle TE. Invited Review: Water consumption, and drinking behavior of beef cattle, and effects of water quality. Applied Animal Science [Internet]. 2021 Aug [cited 2025 Feb 9];37(4):418–35. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2590286521001075.

- Arboitte MZ, Brondani IL, Restle J, Freitas LDS, Pereira LB, Cardoso GDS. Carcass characteristics of small and medium-frame Aberdeen Angus young steers. Acta Sci Anim Sci [Internet]. 2012 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Feb 9];34(1):49–56. Available from: http://periodicos.uem.br/ojs/index.php/ActaSciAnimSci/article/view/12463.

- Silanikove, N. Effects of heat stress on the welfare of extensively managed domestic ruminants. Livestock Production Science [Internet]. 2000 Dec [cited 2025 Feb 10];67(1–2):1–18. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0301622600001627.

- Effects of heat stress on the welfare of extensively managed domestic ruminants. Livestock Production Science [Internet]. 2000 Dec [cited 2025 Feb 10];67(1–2):1–18. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0301622600001627.

- Lagreca GV, Neel JP, Lewis RM, Swecker WS, Duckett SK. How Does Frame Size, Forage Type, and Time-on-Pasture Alter ForageFinished Beef Quality? J Anim Sci Res [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Feb 9];2(3). Available from: https://www.sciforschenonline.org/journals/animal-science-research/JASR-2-119.

- Barro AG, Marestone BS, Dos S. ER, Ferreira GA, Vero JG, Terto DK, et al. Genetic parameters for frame size and carcass traits in Nellore cattle. Trop Anim Health Prod [Internet]. 2023 Apr [cited 2025 Feb 9];55(2):71. Available from: https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11250-023-03464-z.

- Onyango CM, Nyaga JM, Wetterlind J, Söderström M, Piikki K. Precision Agriculture for Resource Use Efficiency in Smallholder Farming Systems in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. Sustainability [Internet]. 2021 Jan 22 [cited 2025 Feb 9];13(3):1158. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/3/1158.

- Palhares JCP, Morelli M, Novelli TI. Water footprint of a tropical beef cattle production system: The impact of individual-animal and feed management. Advances in Water Resources [Internet]. 2021 Mar [cited 2025 Feb 9];149:103853. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0309170821000087.

- Dickhoefer U, Ramadhan MR, Apenburg S, Buerkert A, Schlecht E. Effects of mild water restriction on nutrient digestion and protein metabolism in desert-adapted goats. Small Ruminant Research [Internet]. 2021 Nov [cited 2025 Feb 9];204:106500. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0921448821001772.

- Boulay AM, Drastig K, Amanullah, Chapagain A, Charlon V, Civit B, et al. Building consensus on water use assessment of livestock production systems and supply chains: Outcome and recommendations from the FAO LEAP Partnership. Ecological Indicators [Internet]. 2021 May [cited 2025 Feb 10];124:107391. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470160X2100056X.

- Gupta GS, Orban A. Water is life, life is water: (Un)sustainable use and management of water in the 21st century. CJSSP [Internet]. 2018 Jun 26 [cited 2025 Feb 10];9(1):81–100. Available from: http://cjssp.uni-corvinus.hu/index.php/cjssp/article/view/246.

- Kummu M, Guillaume JHA, De Moel H, Eisner S, Flörke M, Porkka M, et al. The world’s road to water scarcity: shortage and stress in the 20th century and pathways towards sustainability. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2016 Dec 9 [cited 2025 Feb 10];6(1):38495. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/srep38495.

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2023 [Internet]. FAO; 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: http://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc7724en.

- UN, editor. Groundwater making the invisible visible. Paris: UNESCO; 2022. 225 p. (The United Nations world water development report).

- Street, K. Sustainable Development Goals: Country Report 2023. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Filho WL, Wall T, Salvia AL, Dinis MAP, Mifsud M. The central role of climate action in achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2023 Nov 23 [cited 2025 Jun 9];13(1):20582. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-47746-w.

- Horwitz W, AOAC International, editors. Official methods of analysis of AOAC International. 18. ed., current through rev. 1, 2006. Gaithersburg, Md: AOAC International; 2006. 2400 p.

- Ahlberg CM, Allwardt K, Broocks A, Bruno K, Taylor A, Mcphillips L, et al. Characterization of water intake and water efficiency in beef cattle1,2. Journal of Animal Science [Internet]. 2019 Dec 17 [cited 2025 Feb 9];97(12):4770–82. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jas/article/97/12/4770/5628908.

- Pereira GM, Egito AA, Gomes RC, Ribas MN, Torres Junior RAA, Fernandes Junior JA, et al. Water requirements of beef production can be reduced by genetic selection. Animal [Internet]. 2021 Mar [cited 2025 Feb 9];15(3):100142. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1751731120301440.

- Mekonnen MM, Hoekstra AY. A Global Assessment of the Water Footprint of Farm Animal Products. Ecosystems [Internet]. 2012 Apr [cited 2025 Feb 11];15(3):401–15. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10021-011-9517-8.

- SAS Institute. Base SAS 9.4 Procedures Guide, Seventh Edition. 2017.

- Nkrumah JD, Okine EK, Mathison GW, Schmid K, Li C, Basarab JA, et al. Relationships of feedlot feed efficiency, performance, and feeding behavior with metabolic rate, methane production, and energy partitioning in beef cattle1. Journal of Animal Science [Internet]. 2006 Jan 1 [cited 2025 Mar 24];84(1):145–53. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jas/article/84/1/145/4804175.

- McAllister TA, Stanford K, Chaves AV, Evans PR, Eustaquio De Souza Figueiredo E, Ribeiro G. Nutrition, feeding and management of beef cattle in intensive and extensive production systems. In: Animal Agriculture [Internet]. Elsevier; 2020 [cited 2025 Feb 9]. p. 75–98. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/B9780128170526000057.

- Galyean ML, Hales KE. Feeding Management Strategies to Mitigate Methane and Improve Production Efficiency in Feedlot Cattle. Animals [Internet]. 2023 Feb 20 [cited 2025 Mar 24];13(4):758. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/13/4/758.

- Malau-Aduli AEO, Curran J, Gall H, Henriksen E, O’Connor A, Paine L, et al. Genetics and nutrition impacts on herd productivity in the Northern Australian beef cattle production cycle. Veterinary and Animal Science [Internet]. 2022 Mar [cited 2025 Feb 9];15:100228. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2451943X21000636.

- Ziegler RL, Musgrave JA, Meyer TL, Funston RN, Dennis EJ, Hanford KJ, et al. The impact of cow size on cow-calf and postweaning progeny performance in the Nebraska Sandhills. Translational Animal Science [Internet]. 2020 Oct 1 [cited 2025 Feb 9];4(4):txaa194. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/tas/article/doi/10.1093/tas/txaa194/5940764.

- Nguyen DV, Nguyen OC, Malau-Aduli AEO. Main regulatory factors of marbling level in beef cattle. Veterinary and Animal Science [Internet]. 2021 Dec [cited 2025 Feb 9];14:100219. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2451943X21000545.

- Gerber PJ, Mottet A, Opio CI, Falcucci A, Teillard F. Environmental impacts of beef production: Review of challenges and perspectives for durability. Meat Science [Internet]. 2015 Nov [cited 2025 Feb 13];109:2–12. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0309174015300139.

- Ismail M, Al-Ansari T. Enhancing sustainability through resource efficiency in beef production systems using a sliding time window-based approach and frame scores. Heliyon [Internet]. 2023 Jul [cited 2025 Feb 9];9(7):e17773. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2405844023049812.

- Lagreca G, Neel J, Lewis R, Swecker WJ, Duckett S. How Does Frame Size, Forage Type, and Time-on-Pasture Alter ForageFinished Beef Quality? J Anim Sci Res [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2025 Jan 28];2(3). Available from: https://www.sciforschenonline.org/journals/animal-science-research/JASR-2-119.php.

- Golher DM, Patel BHM, Bhoite SH, Syed MI, Panchbhai GJ, Thirumurugan P. Factors influencing water intake in dairy cows: a review. Int J Biometeorol. 2021 Apr;65(4):617–25.

- Burgos MS, Senn M, Sutter F, Kreuzer M, Langhans W. Effect of water restriction on feeding and metabolism in dairy cows. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology [Internet]. 2001 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Feb 9];280(2):R418–27. Available from: https://www.physiology.org/doi/10.1152/ajpregu.2001.280.2.R418.

- Nyamushamba GB, Mapiye C, Tada O, Halimani TE, Muchenje V. Conservation of indigenous cattle genetic resources in Southern Africa’s smallholder areas: turning threats into opportunities — A review. Asian-Australas J Anim Sci [Internet]. 2016 Mar 22 [cited 2025 Feb 10];30(5):603–21. Available from: http://www.ajas.info/journal/view.php?doi=10.5713/ajas.16.0024.

- Miller GA, Auffret MD, Roehe R, Nisbet H, Martínez-Álvaro M. Different microbial genera drive methane emissions in beef cattle fed with two extreme diets. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2023 Apr 13 [cited 2025 Feb 9];14:1102400. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1102400/full.

- Terry SA, Basarab JA, Guan LL, McAllister TA. Strategies to improve the efficiency of beef cattle production. Miglior F, editor. Can J Anim Sci [Internet]. 2021 Mar 1 [cited 2025 Feb 9];101(1):1–19. Available from: https://cdnsciencepub.com/doi/10.1139/cjas-2020-0022.

- Klopatek SC, Oltjen JW. How advances in animal efficiency and management have affected beef cattle’s water intensity in the United States: 1991 compared to 2019. Journal of Animal Science [Internet]. 2022 Nov 1 [cited 2025 Mar 24];100(11):skac297. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jas/article/doi/10.1093/jas/skac297/6692300.

- Johnson JJ, Dunn BH, Radakovich JD. UNDERSTANDING COW SIZE AND EFFICIENCY. 2010.

- Pastor AV, Ludwig F, Biemans H, Hoff H, Kabat P. Accounting for environmental flow requirements in global water assessments [Internet]. Global hydrology/Theory development; 2013 [cited 2025 Feb 9]. Available from: https://hess.copernicus.org/preprints/10/14987/2013/hessd-10-14987-2013.pdf.

- Dressler EA, Shaffer W, Bruno K, Krehbiel CR, Calvo-Lorenzo M, Richards CJ, et al. Heritability and variance component estimation for feed and water intake behaviors of feedlot cattle. Journal of Animal Science [Internet]. 2023 Jan 3 [cited 2025 Feb 11];101:skad386. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jas/article/doi/10.1093/jas/skad386/7424049.

- Ojo AO, Mulim HA, Campos GS, Junqueira VS, Lemenager RP, Schoonmaker JP, et al. Exploring Feed Efficiency in Beef Cattle: From Data Collection to Genetic and Nutritional Modeling. Animals [Internet]. 2024 Dec 17 [cited 2025 Feb 9];14(24):3633. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/14/24/3633.

- Devant M, Marti S. Strategies for Feeding Unweaned Dairy Beef Cattle to Improve Their Health. Animals [Internet]. 2020 Oct 18 [cited 2025 Feb 11];10(10):1908. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/10/10/1908.

- Tedeschi LO, Abdalla AL, Álvarez C, Anuga SW, Arango J, Beauchemin KA, et al. Quantification of methane emitted by ruminants: a review of methods. Journal of Animal Science [Internet]. 2022 Jul 1 [cited 2025 Feb 9];100(7):skac197. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jas/article/doi/10.1093/jas/skac197/6601311.

- O’Meara FM, Gardiner GE, O’Doherty JV, Lawlor PG. Effect of water-to-feed ratio on feed disappearance, growth rate, feed efficiency, and carcass traits in growing-finishing pigs. Translational Animal Science [Internet]. 2020 Apr 1 [cited 2025 Feb 9];4(2):630–40. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/tas/article/4/2/630/5815769.

- Gerbens-Leenes PW, Mekonnen MM, Hoekstra AY. The water footprint of poultry, pork and beef: A comparative study in different countries and production systems. Water Resources and Industry [Internet]. 2013 Mar [cited 2025 Feb 11];1–2:25–36. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S2212371713000024.

- Ridoutt BG, Page G, Opie K, Huang J, Bellotti W. Carbon, water and land use footprints of beef cattle production systems in southern Australia. Journal of Cleaner Production [Internet]. 2014 Jun [cited 2025 Feb 9];73:24–30. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0959652613005349.

| Feed ingredient (kg) | Starter | Grower | Finisher | |

| Hominy chop | 630 | 670 | 690 | |

| Eragrostis hay | 200 | 180 | 160 | |

| Soya oilcake | 80 | 60 | 60 | |

| Molasses | 60 | 60 | 60 | |

| Limestone | 15.0 | 15.0 | 15.0 | |

| Urea | 8.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | |

| Salt | 5.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | |

| Vit/mineral premix | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.6 | |

| Estimated nutrient specifications (%) | ||||

| DM | 92.35 | 93.81 | 93.13 | |

| TDN | 74.22 | 74.69 | 75.26 | |

| NE (MJ/kg) | 6.81 | 6.85 | 6.91 | |

| CF | 8.41 | 7.69 | 7.08 | |

| CP | 13.72 | 13.39 | 13.51 | |

| Ca | 6.98 | 6.86 | 6.79 | |

| P | 3.13 | 3.10 | 3.14 | |

| Frame size | |||

| Measurements | Small | Medium | Large |

| Growth performance | |||

| Wti. (kg) | 159.77c±23.65 | 228.41b±23.65 | 265.14a±23.65 |

| Wtf. (kg) | 292.14c±27.27 | 383.46b±27.27 | 412.73a±27.27 |

| FI (kg) | 813.68b±47.03 | 1025.21a±47.03 | 1021.59a±47.03 |

| WI (L) | 2510.64c±156.3 | 3095.64b±156.3 | 3394.09a±156.3 |

| WC (L) | 2572.88c±158.8 | 3174.07b±158.8 | 3471.88a±158.8 |

| WG (kg) | 132.36b±15.11 | 155.05a±15.11 | 142.59a±15.11 |

| Efficiency measures | |||

| ADG (kg) | 1.26b±0.144 | 1.48a±0.144 | 1.41ab±0.144 |

| FCR | 6.30a±0.679 | 6.66a±0.679 | 6.97a±0.679 |

| WFR (L/kg FI) | 3.09b±0.130 | 3.02b±0.130 | 3.33a±0.130 |

| WIE (L/kg gain) | 19.37b±2.179 | 20.15b±2.179 | 23.15a±2.179 |

| WCE (kg gain/L) | 0.051a±0.005 | 0,049a±0.005 | 0,042b±0.005 |

| WFP/kg (L/kg gain) | 29.51a±3.074 | 27.21a±3.074 | 30.01a ±3.074 |

| WFP/AU (L) | 3822c±197.22 | 4185b±197.22 | 4407a±197.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).