1. Introduction

Key cellular processes such as DNA-methylation or synthesis of neurotransmitters and amino acids rely on the availability of methyl groups. Methyl groups are either obtained from the diet (labile methyl groups) or produced endogenously (methylneogenesis) via the one-carbon (C1-) metabolism [

1]. Folate, choline (or lecithin), betaine, and methionine are examples of the dietary sources of labile methyl groups. The possibility to derive methyl groups from multiple nutrients allows the body flexibility in safeguarding the methylation reservoir. The requirements for each of the dietary methyl donors depend on several factors and are partly determined by the amount of other methyl donors in the diet. The amount of methyl groups in the body is regulated by negative feedback mechanisms within the C1-metabolism, body requirements, urinary excretion of methylated substrates and conservation of methyl groups.

Depletion-studies in animals have shown that on the one hand folate deficiency causes depletion of liver choline [

2] and exaggeration of hepatic steatosis [

3]. On the other hand, a diet depleted of choline (or choline and methionine) causes depletion of liver folate [

4,

5,

6]. Therefore, the ability of switching between folate and choline as sources of methyl groups can secure cellular methylation and underscores the necessity of supply redundancy to safeguard this critically important methyl pool.

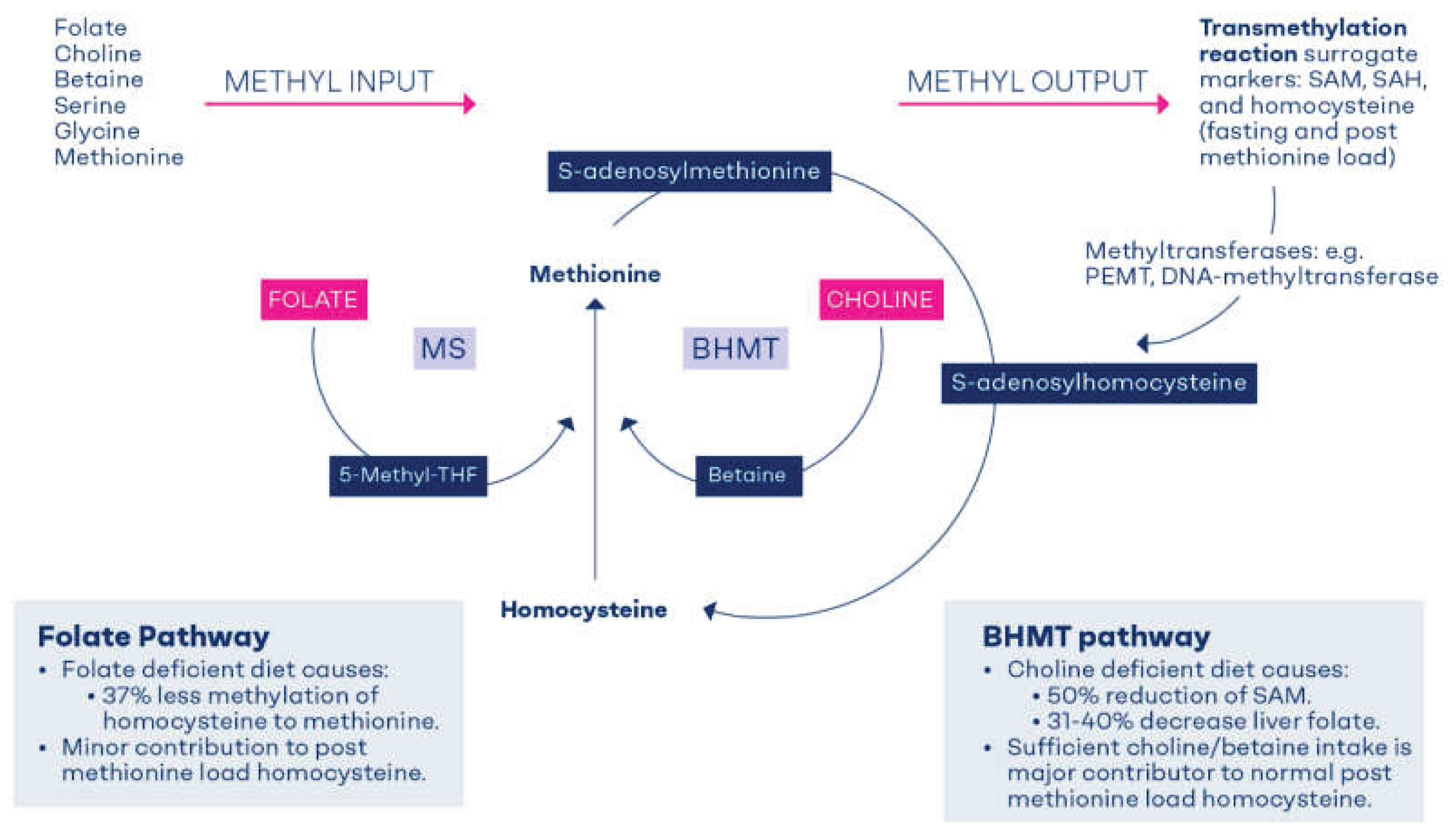

The essential nutrients, folate and choline are metabolically entwined to feed their methyl groups into the C1-metabolism (

Figure 1). Folate has received more attention than choline. One reason is the high-grade evidence regarding the causal link between folate deficiency and diseases such as anemia, birth defects or neurological disorders. The other reason is the availability of biomarkers to measure folate status and relate it to health conditions in human studies. Choline shares some functions with folate, however no biomarkers are currently recognized to accurately measure choline status. A unique characteristic of insufficient dietary choline intake is the development of fatty liver due to insufficient methylation and production of phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho) needed for export of lipids from the liver.

This narrative review highlights the interactions between folate and choline and the essentiality of choline as a key player in C1-metabolism.

2. Formation of Methyl Groups in One Carbon Metabolism

Normal C1-metabolism ensures disposition of CO

2 from different sources such as glucose metabolism, glycine decarboxylation and 10-formyltetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase into the folate pathway. Additionally, it contributes to re-generation of energy as adenine triphosphate (ATP) from adenine diphosphate (ADP) through conversion of 5-formyltetrahydrofolate (5-formylTHF) to tetrahydrofolate (THF). Serine, formate, glycine, dimethylglycine and sarcosine introduce C1-units into the 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate pool and thereby ensure synthesis of purine and pyrimidine and remethylation of homocysteine to methionine. C1-metabolism also contributes to synthesis of the antioxidant glutathione, from cysteine, and to the

de novo synthesis of methionine, adenosine, guanosine and thymidylate. Methionine is an indispensable protein-forming amino acid that is mostly obtained from dietary protein degradation (70% of the methionine). The remaining 30% of methionine is formed from homocysteine in a remethylation pathway that contributes to the body methyl balance [

11].

C1-metabolism is highly active in the liver and the kidney where methionine synthase (MS) and betaine homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT) are expressed [

12,

13]. The liver is also the main folate and vitamin B12 (i.e., B12 is a cofactor for MS) storage organ. Moreover, the liver is very active in taking up choline (60% of 14C-labelled-choline were taken up by the liver within 2 hours) [

14] and rapidly converting it to betaine and phosphocholine within 30 minutes of choline administration [

14]. Homocysteine is converted to methionine via MS using the methyl group of 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate (5-methyl-THF) in the presence of vitamin B12 (methylcobalamin). In a subsequent step, methionine adenosyltransferase, an ATP-dependent enzyme, converts methionine into S-adenosylmethionine (SAM). SAM is a universal methyl donor for numerous methyltransferase-dependent cell reactions. S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) is formed after transferring a methyl-group from SAM to a methyl acceptor (

Figure 1). SAH is converted to homocysteine in an irreversible reaction and homocysteine is either recycled back to methionine to further produce methyl groups or is converted in an irreversible transsulfuration to cystathionine, and finally glutathione [

15].

Betaine is obtained either directly from the diet or via an irreversible mitochondrial oxidation of choline mediated by choline dehydrogenase (CHDH). Betaine is stored in large amounts in tissues where it functions as an osmolyte or used as a methyl donor [

16]. The BHMT pathway is a significant contributor to normal homocysteine metabolism and production of SAM, especially in the non-fasting state or after ingesting a methionine-rich diet. The BHMT enzyme is a zinc metalloenzyme [

17] highly expressed in the liver and kidney, but not in the brain [

18]. Therefore, free choline (a water-soluble molecule) may enter the brain to contribute to formation of brain acetylcholine and phospholipids. For functional methylation within the brain, the brain may rely on methyl groups produced by the liver and the kidney.

Dietary choline is an important source of betaine in the BHMT pathway. The methyl groups of betaine are used to convert homocysteine to methionine via the BHMT pathway thus generating SAM [

19] (

Figure 1). Intervention with betaine has been used to lower plasma homocysteine in patients with severe homocysteinurea due to cystathionine beta synthase deficiency [

20]. Animals lacking the

Bhmt gene provide further evidence on functional roles of the BHMT pathway. Hepatic metabolic and histological abnormalities have been reported in Bhmt-/- mice. Compared to the Bhmt+/+ mice, mice lacking the Bhmt gene had 48% lower liver SAM, 21-fold higher betaine in the liver and liver steatosis [

7]. Failure to export triacylglycerol from the liver of the Bhmt-/- mice can be explained by markedly lowered choline derivatives such as phosphocholine, PtdCho, and sphingomyelin [

7]. The liver synthesis of choline derivatives relies on availability of sufficient methyl groups. This might explain the role of adequate betaine and choline intake in removing the triglycerides from liver cells [

21]. The Bhmt-/- mice developed structural abnormalities in the hepatocytes and the majority of the animals developed liver tumors later in life [

7], suggesting that normal function of the BHMT pathway including sufficient intake of choline contributes to normal liver function.

C1-metabolism is also subject to several feedback mechanisms and it is regulated by the availability of dietary methyl donors. Inadequate input of methyl groups due to prolonged fasting or short term limited intake of proteins, serine, folate or choline causes enhancement of homocysteine conversion to methionine (upregulation of the re-methylation pathways). While under these conditions, the flow of homocysteine via the transsulfuation pathway to cystathionine is downregulated [

11]

. When SAM is formed in excess, it inhibits both the BHMT and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR) which keeps the production of SAM under control.

Experimental dietary folate deficiency in humans (50 µg total folate/day for 6 weeks) leads to 115% increase of fasting plasma homocysteine compared to people on a control diet with sufficient folate [

10]. The 115% increase of fasting plasma homocysteine under the folate deficient diet was associated with only 37% lower remethylation rate of homocysteine to methionine compared to the control diet [

10]. Thus, the rise in plasma homocysteine in folate deficiency is not explained by a corresponding decline in folate-mediated homocysteine remethylation. The question is where could this additional homocysteine come from? It was argued that under the folate depletion model in the study, the BHMT-mediated remethylation of homocysteine to methionine was not stimulated to compensate for folate deficiency [

10]. Folate deficiency may cause a reduction in homocysteine flow through the remethylation pathway, and cause the one-carbon unit of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to be directed toward serine synthesis which may save the C1-units for important cellular reactions [

10]. However, the study did not control for betaine and choline intakes. It is theoretically possible that the BHMT pathway was upregulated in the liver of folate deficient people as an alternative source of SAM. After donating its methyl group, SAM is finally converted to SAH and homocysteine which may explain the 115% increase in plasma homocysteine.

3. Functional Test to Differentiate Between Contributions of Folate and Choline to C1-Metabolism

Folate status is the main determinant of fasting plasma homocysteine [

22]. Thus, fasting plasma homocysteine is a diagnostic marker of folate deficiency. Increasing folate intake is the most effective measure of lowering fasting plasma homocysteine, although vitamin B12 and B6 can also slightly lower plasma homocysteine.

Epidemiological studies found that a 2-fold higher choline and betaine intake (383 mg vs. 689 mg/day) was associated with approx. 1 µmol/L lower fasting plasma homocysteine (-8% versus the low intake category) [

23]. The association between choline and betaine intake on the one hand and fasting homocysteine on the other hand was most pronounced among women with a low folate intake (a methyl-deficient diet) [

23]. Supplementing choline (2.6 g per day as phosphatidylcholine for 2 weeks) [

24] or betaine (1.5g, 3g and 6 g per day for 6 weeks) [

25] caused a dose-response, although moderate, reduction of fasting homocysteine compared to the placebo (-1.3 µmol/L to -2.2 µmol/L or -12% to -20%). Supplementing folic acid for 6 weeks lowered fasting homocysteine to a higher extent than betaine (-18% for folic acid vs. -11% for betaine; both versus placebo) [

8]. These data confirm the dominant effect of folate as determinant of fasting homocysteine concentrations.

In the methionine load test, 75-100 mg methionine per kg body weight (5.6g to 7.5g methionine for a 75 kg person) are ingested and the concentrations of plasma homocysteine are measured after 4, 6, 8, or 12 hours after methionine administration [

26]. Roughly 50% of people with hyperhomocysteinemia after methionine load may have normal fasting plasma homocysteine results [

27,

28,

29], suggesting that methionine load test can uncover disorders in C1-metabolism not captured by measuring fasting homocysteine. Van der Griend et al., defined post methionine load (PML)- hyperhomocysteinemia as increase in homocysteine concentrations after methionine load (6 hour concentration minus fasting concentration) of > 42.3 µmol/L (the 95

th percentile of control subjects) [

27]. The definition of PML hyperhomocysteinemia varies between studies and direct comparison of the results of the test between studies is not possible due to lack of standardization with regard to the time point of measuring homocysteine after the methionine dose or the need to adjust for baseline homocysteine [

26]. The PML-homocysteine concentrations can be influenced by nutritional and genetic factors (

Table 1).

Both acute and chronic intakes of either betaine or choline cause a significant reduction of PML homocysteine response. A single dose of 1.5g, 3g or 6g betaine attenuated the increase of plasma homocysteine after methionine load (by 16%, 23%, and 35%, respectively compared to the placebo) [

25]. Similarly, a single dose of 1.5g choline (from phosphatidylcholine) lowered the PML homocysteine by 15% (-4.8 µmol/L; 95% CI: -6.8, -2.8 µmol/L) compared to the placebo [

24], suggesting that choline was converted to betaine and used as an immediate source of methyl groups. A 32% reduction of PML-homocysteine was also reported after 6 hours of a meal that was rich either in betaine or in choline compared to a control meal that was depleted of the two nutrients [

9]. Therefore, the PML-homocysteine concentration seems to be a sensitive marker of recent intake of choline and betaine. This test maybe used to define the intakes of betaine or choline at the inflection point of the homocysteine curve (i.e., when higher intake of betaine or choline does not lead to a further reduction in PML-homocysteine).

It has been shown that concentrations of plasma betaine correlate with PML-homocysteine concentrations in general [

31,

32]. The correlation remained significant when people received supplements containing folic acid [

31] or when plasma folate concentrations were accounted for [

32]. Thus, PML-homocysteine is a sensitive marker of low plasma betaine (and possibly choline). This suggestion is strengthened by results from a randomized placebo controlled trial measuring PML-homocysteine levels before and after supplementing either 400 µg x 2 per day folic acid or 3g betaine x 2 per day for a duration of 6 weeks (both interventions were tested against a placebo) (

Table 2) [

8]. Betaine supplementation for 6 weeks caused a strong reduction of the PML-homocysteine concentrations compared to the placebo group [mean difference (95%CI) at 6 hours = -17.7 (-31.8, -5.3) µmol/L]. Folic acid supplementation caused a non-significant change of the PML-homocysteine compared to the placebo [mean difference (95%CI) at 6 hours = 1.1 (-13.2, 15.4) µmol/L] [

8] (

Table 2). Similarly, supplementation of 2.6g choline per day (as phosphatidylcholine) for 2 weeks caused 29% lower PML-homocysteine concentrations compared to the placebo [

24] (

Table 2).

The methionine load test is not widely used in clinical practice due to its tedious nature. Especially due to the lack of recognized markers of choline and betaine status and intake, the PML-homocysteine provides information that cannot be inferred from fasting plasma homocysteine. This test offers a unique tool that can show the relative contribution of betaine and choline as methyl donors (even in case of high plasma folate).

Table 3 shows candidate conditions where supplementing betaine/or choline can contribute to normal homocysteine metabolism on case of PML-hyperhomocysteinemia. Examples of gaps in knowledge about potential use of PML-homocysteine in diagnostic and research areas are shown in

Table 4.

4. Safeguarding the Methyl Balance Through the Diet or Methylneogenesis

The diet provides a wide intake range of methyl sources. People achieving the current dietary intake recommendations of methyl donors are unlikely to have impaired methylation. However, the methylation equilibrium could be disrupted under conditions of high requirement, increased loss or low intake of one or more methyl donors. De-novo formation of new methyl groups (methylneogenesis) can maintain the net amount of methyl groups in the body when the dietary intake of methyl donors is temporarily limited [

43] and under prolonged fasting conditions.

Body methylation balance is influenced by renal excretion of SAM and other methylated compounds such as creatine, creatinine, N-methyl nicotinic acid, carnitine, methylated amino acids, and the terminal oxidation of methyl groups, including that of sarcosine (or N-methylglycine) [

44]. The relative contribution of the loss of methyl groups in the bile and stool to body methyl balance remains unknown. In addition, biliary excretion of PtdCho was estimated to consume 5 mmol SAM per day, but it is unknown whether this PtdCho is reabsorbed.

There have been some attempts to qualify body methyl flux that reflects overall body dynamics of methyl groups in µmol.kg

-1.h

-1. Using stable isotope infusion technique, the daily methyl flux in healthy subjects was estimated to be between 16.7 and 23.4 mmol/L (for a 70 kg person) combining the fasting and fed situations within 24 hours [

43]. Approximately 40% of the daily formed homocysteine is remethylated to methionine and 54% of the methyl groups required for this remethylation was generated via the methylneogenic pathway [

45]. Homocysteine remethylation using the methyl group of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-methyl-THF) has been estimated to be between 2 and 8 µmol.kg

-1.h

-1 [

45], suggesting that homocysteine remethylation via methionine synthase constitutes a small fraction of human one-carbon metabolic flux. Considering that Bhmt knockout mice had 48% lower liver SAM compared to the controls, it can be inferred that roughly 50% of SAM is coming from the BHMT pathway [

7].

Folate and choline are also key sources of one carbon units that feed again into the folate cycle [

43]. Sarcosine can be synthesized from SAM-dependent methylation of glycine or from oxidation of choline to betaine that is converted to dimethylglycine and then to sarcosine. A substantial amount of one carbon units originates from glycine and serine [

46]. Methionine load (such as after a protein rich meal) stimulates activities of some methyltransferases such as guanidoacetic methyltransferase [

47] and glycine N-methyltransferase [

44] that can lead to forming creatine and sarcosine, respectively.

5. Factors Affecting Methylneogenesis

C1-metabolism is influenced by the availability of one carbon moieties in the diet, sex, age, genetic polymorphisms, and body requirements (e.g., during pregnancy or early life). Some of these factors have been extensively investigated.

The activities of several enzymes involved in C1-metabolism differ by sex [

41]. The expression of PEMT gene is responsive to estrogen [

48,

49]. Therefore, the reliance of PEMT on methyl groups is high in premenopausal women and highest during the third trimester of pregnancy. Whereas, PEMT activity may be lowest in postmenopausal women and men. Moreover, people with a homozygous PEMT SNP [

50,

51] are more sensitive to develop symptoms of choline deficiency (e.g., fatty liver or muscle damage) than people without this SNP, especially under restricted choline and or folate intake.

The presence of homozygous variant of the common polymorphism in the MTHFR gene (C677T: TT genotype) causes lower activity of the enzyme and compromises circulating concentrations of folate. Mthfr-/- mice have high postnatal death [

52], hyperhomocysteinemia, hypomethlyation and are prone to develop fatty liver under choline deficient diet [

53]. Betaine supplementation to pregnant mice throughout the pregnancy and until weaning of the pups at 3 weeks of age decreased the mortality of Mthfr-/- mice from 83% to 26%, lowered plasma homocysteine and increased methionine and SAM concentrations in the liver and the brain [

52], showing that the BHMT pathway can rescue at least part of severe metabolic and phenotypic consequences of MTHFR deficiency.

In humans, the 677TT genotype is associated with elevated fasting plasma homocysteine, low serum and blood folate concentrations [

54,

55] and attenuated response to folate supplementation [

54]. Yan et al., showed that the demand for betaine to generate methionine from homocysteine is likely higher in individuals with the 677TT genotype [

55]. In a 12-week study of 60 men with known genotype for MTHFRC677T, a daily 550 mg or 1100 mg choline was supplemented for 9 weeks followed by d-9 labeled choline for another 3 weeks [

55]. The higher ratio of d-9-betaine to d-9-PtdCho in the 1100 mg choline group vs the 550 mg group indicated greater shunting away from the CDP-pathway and down the PEMT pathway [

55]. The higher plasma betaine/CDP-choline ratio in subjects with the TT genotype is consistent with the increased demand for choline and therefore, the imperative to channel higher proportion of choline into betaine under limited folate status

.

Table 5.

Factors that affect methylneogenesis.

Table 5.

Factors that affect methylneogenesis.

| Factor |

Explanation |

Reference |

| Dietary deficiency of selected nutrients |

Sufficient intakes of folate, choline, betaine, methionine and serine can compensate for temporary lack of other nutrients with methyl donor function. |

|

| Sex |

Expression and activity of several genes in C1-metabolism differ by sex. |

[41] |

| Age |

Estrogen-dependent regulation of PEMT gene provides additional source of choline in liver of premenopausal and pregnant women. |

[48,49] |

| Polymorphisms in genes involved in the folate pathway |

Individuals with MTHFR677TT genotype may be prone to low folate and rely more on generating SAM from choline, betaine and other nutrients. |

[55] |

| polymorphisms in genes that rely on SAM |

PEMT gene polymorphisms could reduce endogenous synthesis of phosphatidylcholine and thus the net flux of methyl groups. |

[50,51] |

6. Phosphatidylethanolamine methyltransferase Role in Methylneogenesis

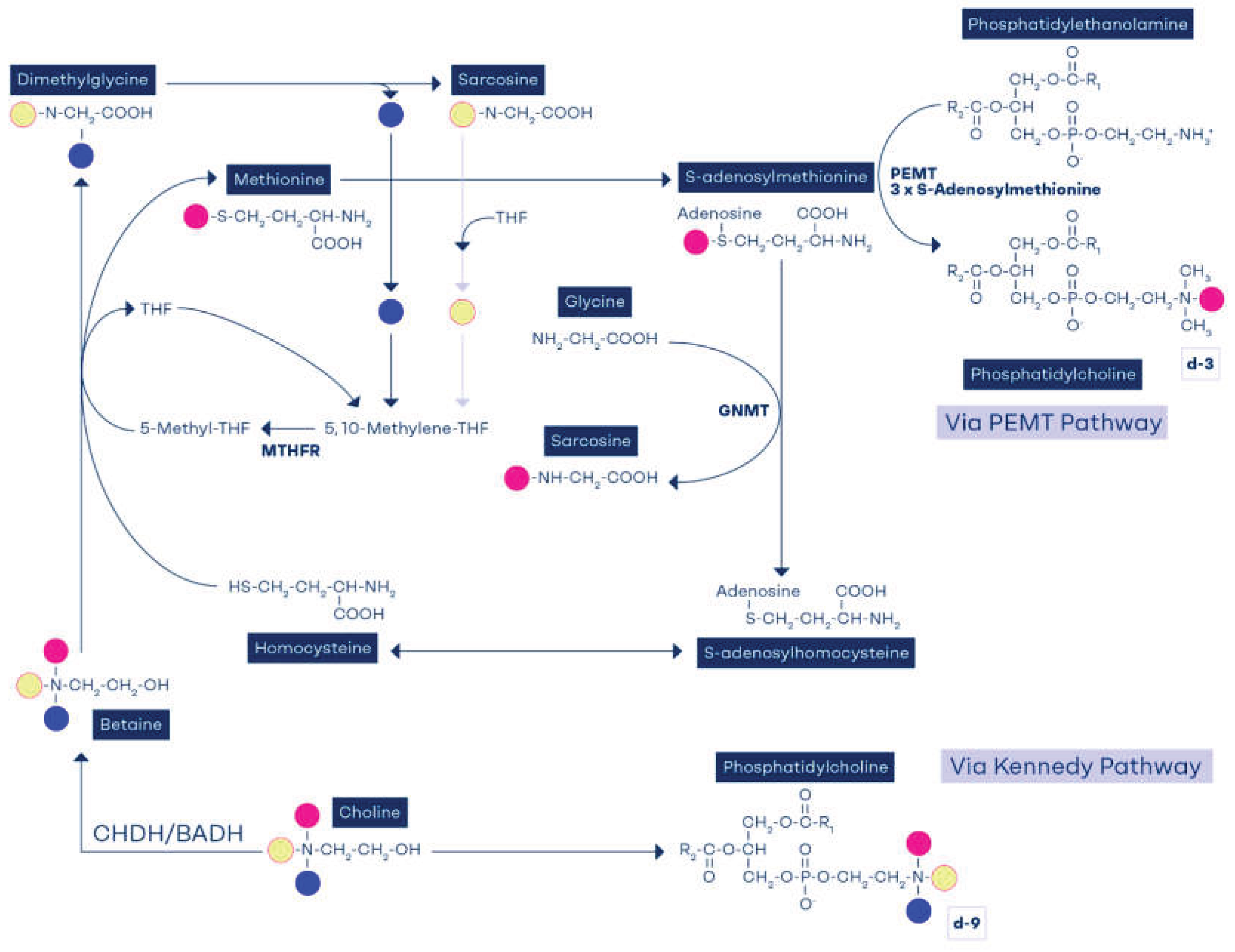

The enzyme PEMT is an SAM-dependent enzyme that is responsible for synthesis of 30% of PtdCho in the liver [

56,

57]. PEMT utilizes three SAM molecules to convert one molecule of phosphatidylethanolamine into PtdCho [

58] and as a result, 3 molecules SAH and then homocysteine are produced. One of the three methyl groups of PtdCho originates from homocysteine remethylation via the BHMT pathway.

When deuterium-labeled choline is used and the methyl groups are tracked, it was found that, the choline diphosphate (CDP) deuterated methyl groups are detected as d-9-PtdCho, showing that the labelled methyl group is channeled down the Kennedy pathway. When choline is driven down the PEMT pathway via methionine, then only one deuterated methyl group can be detected as d-3- PtdCho (

Figure 2). PtdCho derived from the PEMT pathway requires three sequential methylation reactions of phosphotidylethanolamine (PE) that will generate d-3-PtdCho, d-6-PtdCho (if it has two methyl groups from the originally labeled choline or betaine) or rarely d-9 (three deutereum labeled methyl groups).

Metabolites can also be identified by this method (d-6-dimethylglycine, d-3-sarcosine, d-3-methionine and d-3-SAM).

Figure 2 illustrates the metabolic fate of choline's methyl groups as demonstrated by compartmentalization studies [

65].

The PEMT pathway is a significant contributor to methyl group homeostasis [

43]. It has been estimated that PEMT-mediated PtdCho synthesis may consume 5 mmol SAM per day [

59], thus implying that an equivalent amount of SAH and homocysteine is produced. Stead et al., reported that mice lacking PEMT activity have 50% lower plasma homocysteine and suggested that the PEMT pathway is a significant source of homocysteine and thus SAM in the body [

59]. Independent experiments have shown that hepatocytes isolated from PEMT-/- mice have lower PEMT activity and secrete less homocysteine than hepatocytes from control mice [

60]. In contrast, studies on CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase-(CT) knockout mice where higher PEMT flux leads to higher PtdCho production, the concentrations of plasma homocysteine were 20-40% higher than in the control mice [

61]. Seventy percent of liver PtdCho is produced via the CDP-choline pathway. In CTP: phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase-(CT) knockout mice [

61], hepatic CDP-choline pathway is 80% lower than in the control mice while PEMT mRNA, protein, and activity are upregulated possibly to compensate for the absence of the CDP-pathway and produce more PtdCho under the same standard diet [

62]. Also the BHMT activity was increased by 80% in the CT knockout mice, thus securing a source of methyl groups needed for the PEMT activity through oxidation of choline to betaine. Therefore, the need to maintain sufficient amount of PtdCho in this genetic mice model caused compensatory induction of PEMT and BHMT pathways of the same magnitude [

61]. Although BHMT-induction does not lead to normalizing plasma homocysteine, it may maintain SAM at control levels [

61]. The compensatory induction of BHMT is similar to the situation in Mthfr

-/- and Cbs

-/- mice models where homocysteine accumulates [

63,

64]. On the other hand, deletion of the BHMT gene in mice has been shown to cause 8-fold increase in plasma homocysteine, a massive disturbance in hepatic methylation potential (low SAM and high SAH) and accumulation of fats in the liver due to inability to synthesize sufficient PtdCho to export the triglycerides from the hepatic cells [

7]. Therefore, the BHMT pathway that relies on adequate intake of choline and betaine is a significant source of methyl groups needed to produce PtdCho via PEMT. The PEMT pathway consumes SAM, but also provides SAH and thereby homocysteine that is recycled to methionine and new methyl groups.

PtdCho that is produced via the PEMT pathway using methyl groups of folate, betaine and choline transports long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) (22:6n−3) [

65], the fatty acid highly enriched in brain and retina. In contrast, phospholipids derived through the CDP pathway carry medium chain, monounsaturated fatty acids such as oleic acid [

66].

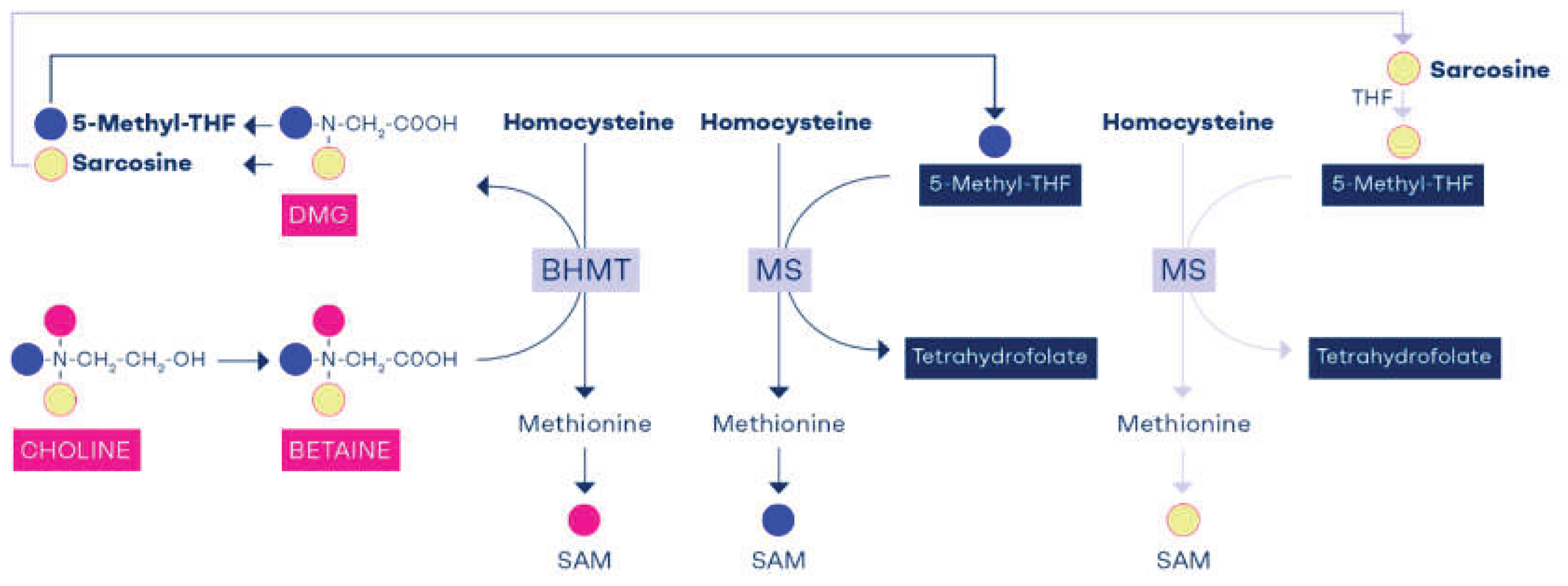

7. Tracking the Methyl Groups of Betaine and Choline

The transmethylation reaction via BHMT provides one methyl group to convert homocysteine to methionine and retains the remaining 2 methyl groups of betaine that forms dimethylglycine. One methyl group of dimethylglycine provides C1-unit that is used to convert THF to 5,10-methylene-THF and sarcosine is produced. Sarcosine or N-methylglycine carries the last methyl group of dimethylglycine which is used to convert THF to 5,10-methylene-THF and producing glycine [

67]. Thus, one of choline’s methyl groups is used to produce SAM and the remaining 2 methyl groups reenter the C1-metabolim pool as 5, 10-methylene-THF via formaldehyde. Choline enriches folate pathway with 2 carbon units that can join C1-metabolism as labile methyl groups via 5-methyl-THF (

Figure 3).

The role of choline in enrichment of cellular folate has been shown in a study in newborn pigs [

68]. The animals were fed a methyl deficient diet (without folate, choline and betaine) at the age of 4-8 days for 7 days and then received a rescue with either folate or betaine between days 7 and 10 [

68]. The folic acid group showed a normalization of plasma folate, a decline of plasma homocysteine and no change in plasma betaine [

68]. Whereas, in the betaine rescue group, besides showing correction of plasma betaine, showed a significant rise of plasma folate, demonstrating that folate was endogenously produced after conversion of betaine to sarcosine (

Figure 3).

8. Interdependency of Folate and Choline

It has also been previously reported that 60% of choline is converted to betaine in the liver and this was confirmed in an in-vitro study by DeLong et al., in which the levels of betaine were found to be three times as high as choline in normal hepatocyte culture [

57]. When hepatocytes were exposed to isotope labelled choline (d9-choline), the ratio of d9-labeled betaine to choline was the same as the unlabeled betaine to choline. When choline is absent from the cell system, no betaine can be detected, demonstrating that oxidation of choline is an obligatory source of betaine in hepatocytes [

57]. Liver cancer cells (RH7777 Hepatoma) do not have the enzyme system to convert choline to betaine and hence the 3:1 ratio of betaine to choline is extinguished, thus confirming the significant contribution of choline’s methyl groups to betaine in the liver [

57].

In the presence of a choline/betaine deficiency, there is greater dependence on 5-methyl-THF to generate PtdCho via the PEMT pathway (

Figure 2). A choline deficient diet for 2 weeks in rats caused a 31 – 40% reduction in liver folate content, which was reversible when choline refeeding occurred [

4,

5]. Rats fed diets deficient in both methionine and choline for 5 weeks had hepatic folate concentrations that were 50% of those in controls [

5]. Tetrahydrofolate deficiency, induced by methotrexate [

69,

70,

71,

72,

73] or by dietary folate deficiency [

2], resulted in decreased hepatic total choline, with the greatest decrease occurring in hepatic phosphocholine concentrations. During choline deficiency, hepatic SAM concentrations also decreased by as much as 50% [

74,

75,

76,

77].

These results suggest that temporary low intake of one of these nutrients such as due to seasonal food availability or food choice can be compensated for by other nutrients or methylneogenesis in the C1-metabolism. Whereas, one sided nutrition or lack of methyl donors in critical stages of the life cycle such as during pregnancy, lactation and early life can have serious consequences on health.

9. Conclusions

The essential nutrients, folate and choline are metabolically entwined to provide SAM for functional methylation reactions. A folate deficient diet depletes liver choline and a choline deficient diet depletes liver folate by up to 40%, suggesting that long-term depletion of one of these nutrients can have devastating effects on cellular methylation capacity. Dietary folate intake or plasma concentrations of 5-Methyl-THF play a dominant role in determining fasting plasma homocysteine concentrations, but this role is not exclusive. Intakes of choline and betaine show weak associations with fasting plasma homocysteine. Studies on Bhmt-/- mice suggest that this choline- or betaine-dependent enzyme contributes to 50% of cellular SAM, but its role in methylation is not reflected by measuring fasting plasma homocysteine, nor by the effect of supplemental betaine or choline on lowering fasting homocysteine. Instead, the BHMT pathway’s major contribution to removing homocysteine can only be appreciated after a standard methionine load test (100 mg methionine/kg body weight), while folate has a limited effect on post methionine hyperhomocysteinemia. Measuring post methionine load (PML) homocysteine concentrations can be used as a sensitive marker of the contribution of choline and betaine to cellular methylation. The multiple scientific studies reviewed here support a significant and so far underestimated role of choline and betaine as sources of methyl groups.

Author Contributions

JB wrote the first draft of the paper. RO provided input and revisions to all parts of the paper.

Funding

No funding was received for this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

JB is employed by Balchem Corporation. RO received honoraria for lectures and served as advisory board member for P&G Health GmbH, Wörwag Pharma GmbH, Balchem Corporation, Merck & Cie, and HIPP GmbH.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript: ADP, adenine diphosphate; ATP, adenine triphosphate; BHMT, betaine homocysteine methyltransferase; CHDH, choline dehydrogenase; C1-metabolism, one carbon metabolism; 5-formylTHF, 5-formyltetrahydrofolate; PML, post methionine load; PtdCho, phosphatidylcholine; 5-methyl-THF, 5-Methyltetrahydrofolate; MS, methionine synthase; MTS, methionine adenosyltransferase; MTHFR, methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase; SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; SAH, S-adenosylhomocysteine; THF, tetrahydrofolate.

References

- Finkelstein J.D., Kyle W.E., Harris B.J. Methionine metabolism in mammals: regulatory effects of S-adenosylhomocysteine. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1974, 165, 774-779. [CrossRef]

- Kim Y.I., Miller J.W., da Costa K.A., Nadeau M., Smith D., Selhub J., Zeisel S.H., Mason J.B. Severe folate deficiency causes secondary depletion of choline and phosphocholine in rat liver. J Nutr. 1994, 124, 2197-2203. [CrossRef]

- Johnson B.C., James M.F. Choline deficiency in the baby pig. J. Nutr. 1948, 36, 339-349. [CrossRef]

- Selhub J., Seyoum E., Pomfret E.A., Zeisel S.H. Effects of choline deficiency and methotrexate treatment upon liver folate content and distribution. Cancer Res 1991, 51, 16-21.

- Horne D.W., Cook R.J., Wagner C. Effect of dietary methyl group deficiency on folate metabolism in rats. J Nutr. 1989, 119, 618-621. [CrossRef]

- Varela-Moreiras G., Ragel C., Perez de M.J. Choline deficiency and methotrexate treatment induces marked but reversible changes in hepatic folate concentrations, serum homocysteine and DNA methylation rates in rats. J Am. Coll. Nutr. 1995, 14, 480-485. [CrossRef]

- Teng Y.W., Mehedint M.G., Garrow T.A., Zeisel S.H. Deletion of betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase in mice perturbs choline and 1-carbon metabolism, resulting in fatty liver and hepatocellular carcinomas. J Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 36258-36267. [CrossRef]

- Steenge G.R., Verhoef P., Katan M.B. Betaine supplementation lowers plasma homocysteine in healthy men and women. J Nutr. 2003, 133, 1291-1295. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson W., Elmslie J., Lever M., Chambers S.T., George P.M. Dietary and supplementary betaine: acute effects on plasma betaine and homocysteine concentrations under standard and postmethionine load conditions in healthy male subjects. Am. J Clin Nutr. 2008, 87, 577-585. [CrossRef]

- Cuskelly G.J., Stacpoole P.W., Williamson J., Baumgartner T.G., Gregory J.F., III. Deficiencies of folate and vitamin B(6) exert distinct effects on homocysteine, serine, and methionine kinetics. Am J Physiol Endocrinol. Metab 2001, 281, E1182-E1190. [CrossRef]

- Mudd S.H., Poole J.R. Labile methyl balances for normal humans on various dietary regimens. Metabolism 1975, 24, 721-735. [CrossRef]

- Chen L.H., Liu M.L., Hwang H.Y., Chen L.S., Korenberg J., Shane B. Human methionine synthase. cDNA cloning, gene localization, and expression. J Biol. Chem 1997, 272, 3628-3634. [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein J.D. Pathways and regulation of homocysteine metabolism in mammals. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2000, 26, 219-225. [CrossRef]

- Galletti P., De R.M., Cotticelli M.G., Morana A., Vaccaro R., Zappia V. Biochemical rationale for the use of CDPcholine in traumatic brain injury: pharmacokinetics of the orally administered drug. J Neurol. Sci. 1991, 103 Suppl, S19-S25. [CrossRef]

- Stipanuk M.H. Metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids. Annu. Rev. Nutr 1986, 6, 179-209. [CrossRef]

- Schafer C., Hoffmann L., Heldt K., Lornejad-Schafer M.R., Brauers G., Gehrmann T., Garrow T.A., Haussinger D., Mayatepek E., Schwahn B.C. et al. Osmotic regulation of betaine homocysteine-S-methyltransferase expression in H4IIE rat hepatoma cells. Am. J Physiol Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 2007, 292, G1089-G1098. [CrossRef]

- Millian N.S., Garrow T.A. Human betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase is a zinc metalloenzyme. Arch Biochem. Biophys. 1998, 356, 93-98. [CrossRef]

- McKeever M.P., Weir D.G., Molloy A., Scott J.M. Betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase: organ distribution in man, pig and rat and subcellular distribution in the rat. Clin Sci (Lond) 1991, 81, 551-556. [CrossRef]

- Wilcken D.E., Wilcken B., Dudman N.P., Tyrrell P.A. Homocystinuria--the effects of betaine in the treatment of patients not responsive to pyridoxine. N. Engl. J Med 1983, 309, 448-453. [CrossRef]

- Wilcken D.E., Dudman N.P., Tyrrell P.A. Homocystinuria due to cystathionine beta-synthase deficiency--the effects of betaine treatment in pyridoxine-responsive patients. Metabolism 1985, 34, 1115-1121. [CrossRef]

- Buchman A.L., Dubin M., Jenden D., Moukarzel A., Roch M.H., Rice K., Gornbein J., Ament M.E., Eckhert C.D. Lecithin increases plasma free choline and decreases hepatic steatosis in long-term total parenteral nutrition patients. Gastroenterology 1992, 102, 1363-1370. [CrossRef]

- Selhub J., Jacques P.F., Wilson P.W., Rush D., Rosenberg I.H. Vitamin status and intake as primary determinants of homocysteinemia in an elderly population. JAMA 1993, 270, 2693-2698. [CrossRef]

- Chiuve S.E., Giovannucci E.L., Hankinson S.E., Zeisel S.H., Dougherty L.W., Willett W.C., Rimm E.B. The association between betaine and choline intakes and the plasma concentrations of homocysteine in women. Am. J Clin Nutr. 2007, 86, 1073-1081. [CrossRef]

- Olthof M.R., Brink E.J., Katan M.B., Verhoef P. Choline supplemented as phosphatidylcholine decreases fasting and postmethionine-loading plasma homocysteine concentrations in healthy men. Am. J Clin Nutr. 2005, 82, 111-117. [CrossRef]

- Olthof M.R., van V.T., Boelsma E., Verhoef P. Low dose betaine supplementation leads to immediate and long term lowering of plasma homocysteine in healthy men and women. J Nutr. 2003, 133, 4135-4138. [CrossRef]

- Ubbink J.B., Becker P.J., Delport R., Bester M., Riezler R., Vermaak W.J. Variability of post-methionine load plasma homocysteine assays. Clin Chim. Acta 2003, 330, 111-119. [CrossRef]

- van der Griend R., Haas F.J., Duran M., Biesma D.H., Meuwissen O.J., Banga J.D. Methionine loading test is necessary for detection of hyperhomocysteinemia. J. Lab Clin Med 1998, 132, 67-72. [CrossRef]

- van der Griend R., Biesma D.H., Banga J.D. Postmethionine-load homocysteine determination for the diagnosis hyperhomocysteinaemia and efficacy of homocysteine lowering treatment regimens. Vasc. Med 2002, 7, 29-33. [CrossRef]

- Bostom A.G., Jacques P.F., Nadeau M.R., Williams R.R., Ellison R.C., Selhub J. Post-methionine load hyperhomocysteinemia in persons with normal fasting total plasma homocysteine: initial results from the NHLBI Family Heart Study. Atherosclerosis 1995, 116, 147-151. [CrossRef]

- Lever M., Slow S., McGregor D.O., Dellow W.J., George P.M., Chambers S.T. Variability of plasma and urine betaine in diabetes mellitus and its relationship to methionine load test responses: an observational study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2012, 11, 34. [CrossRef]

- Holm P.I., Bleie O., Ueland P.M., Lien E.A., Refsum H., Nordrehaug J.E., Nygard O. Betaine as a determinant of postmethionine load total plasma homocysteine before and after B-vitamin supplementation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004, 24, 301-307. [CrossRef]

- Holm P.I., Ueland P.M., Vollset S.E., Midttun O., Blom H.J., Keijzer M.B., den Heijer M. Betaine and folate status as cooperative determinants of plasma homocysteine in humans. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005, 25, 379-385. [CrossRef]

- Lee J.E., Jacques P.F., Dougherty L., Selhub J., Giovannucci E., Zeisel S.H., Cho E. Are dietary choline and betaine intakes determinants of total homocysteine concentration? Am. J Clin Nutr. 2010, 91, 1303-1310. [CrossRef]

- da Costa K.A., Gaffney C.E., Fischer L.M., Zeisel S.H. Choline deficiency in mice and humans is associated with increased plasma homocysteine concentration after a methionine load. Am. J Clin Nutr. 2005, 81, 440-444. [CrossRef]

- Verhoef P., Steenge G.R., Boelsma E., van V.T., Olthof M.R., Katan M.B. Dietary serine and cystine attenuate the homocysteine-raising effect of dietary methionine: a randomized crossover trial in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2004, 80, 674-679. [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Torres A.G., Matias-Aguilar L.O., Coria-Ramirez E., Bonilla-Gonzalez E., Gonzalez-Marquez H., Ibarra-Gonzalez I., Hernandez-Lopez J.R., Hernandez-Juarez J., Dominguez-Reyes V.M., Isordia-Salas I. et al. Cystathionine beta-synthase and methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase mutations in Mexican individuals with hyperhomocysteinemia. SAGE Open. Med 2020, 8, 2050312120974193. [CrossRef]

- Lievers K.J., Kluijtmans L.A., Heil S.G., Boers G.H., Verhoef P., den H.M., Trijbels F.J., Blom H.J. Cystathionine beta-synthase polymorphisms and hyperhomocysteinaemia: an association study. Eur. J Hum. Genet. 2003, 11, 23-29. [CrossRef]

- Bhat D.S., Gruca L.L., Bennett C.D., Katre P., Kurpad A.V., Yajnik C.S., Kalhan S.C. Evaluation of tracer labelled methionine load test in vitamin B-12 deficient adolescent women. PLoS. ONE. 2018, 13, e0196970. [CrossRef]

- Chiang E.P., Selhub J., Bagley P.J., Dallal G., Roubenoff R. Pyridoxine supplementation corrects vitamin B6 deficiency but does not improve inflammation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005, 7, R1404-R1411. [CrossRef]

- de J.R., Griffioen P.H., van Z.B., Brouns R.M., Visser W., Lindemans J. Evaluation of a shorter methionine loading test. Clin Chem Lab Med 2004, 42, 1027-1031. [CrossRef]

- Sadre-Marandi F., Dahdoul T., Reed M.C., Nijhout H.F. Sex differences in hepatic one-carbon metabolism. BMC. Syst. Biol. 2018, 12, 89. [CrossRef]

- Nelen W.L., Blom H.J., Thomas C.M., Steegers E.A., Boers G.H., Eskes T.K. Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphism affects the change in homocysteine and folate concentrations resulting from low dose folic acid supplementation in women with unexplained recurrent miscarriages. J Nutr 1998, 128, 1336-1341. [CrossRef]

- Mudd S.H., Brosnan J.T., Brosnan M.E., Jacobs R.L., Stabler S.P., Allen R.H., Vance D.E., Wagner C. Methyl balance and transmethylation fluxes in humans. Am. J Clin Nutr. 2007, 85, 19-25. [CrossRef]

- Mudd S.H., Ebert M.H., Scriver C.R. Labile methyl group balances in the human: the role of sarcosine. Metabolism 1980, 29, 707-720. [CrossRef]

- Storch K.J., Wagner D.A., Burke J.F., Young V.R. Quantitative study in vivo of methionine cycle in humans using [methyl-2H3]- and [1-13C]methionine. Am J Physiol 1988, 255, E322-E331. [CrossRef]

- Lamers Y., Williamson J., Gilbert L.R., Stacpoole P.W., Gregory J.F., III. Glycine turnover and decarboxylation rate quantified in healthy men and women using primed, constant infusions of [1,2-(13)C2]glycine and [(2)H3]leucine. J Nutr 2007, 137, 2647-2652. [CrossRef]

- Im Y.S., Chiang P.K., Cantoni G.L. Guanidoacetate methyltransferase. Purification and molecular properties. J Biol Chem 1979, 254, 11047-11050. [CrossRef]

- Resseguie M., Song J., Niculescu M.D., da Costa K.A., Randall T.A., Zeisel S.H. Phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PEMT) gene expression is induced by estrogen in human and mouse primary hepatocytes. FASEB J 2007, 21, 2622-2632. [CrossRef]

- Resseguie M.E., da Costa K.A., Galanko J.A., Patel M., Davis I.J., Zeisel S.H. Aberrant estrogen regulation of PEMT results in choline deficiency-associated liver dysfunction. J Biol. Chem 2011, 286, 1649-1658. [CrossRef]

- da Costa K.A., Kozyreva O.G., Song J., Galanko J.A., Fischer L.M., Zeisel S.H. Common genetic polymorphisms affect the human requirement for the nutrient choline. FASEB J 2006, 20, 1336-1344. [CrossRef]

- Fischer L.M., daCosta K.A., Kwock L., Stewart P.W., Lu T.S., Stabler S.P., Allen R.H., Zeisel S.H. Sex and menopausal status influence human dietary requirements for the nutrient choline. Am. J Clin Nutr. 2007, 85, 1275-1285. [CrossRef]

- Schwahn B.C., Laryea M.D., Chen Z., Melnyk S., Pogribny I., Garrow T., James S.J., Rozen R. Betaine rescue of an animal model with methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. Biochem. J 2004, 382, 831-840. [CrossRef]

- Chen Z., Karaplis A.C., Ackerman S.L., Pogribny I.P., Melnyk S., Lussier-Cacan S., Chen M.F., Pai A., John S.W., Smith R.S. et al. Mice deficient in methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase exhibit hyperhomocysteinemia and decreased methylation capacity, with neuropathology and aortic lipid deposition. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 433-443. [CrossRef]

- Colson N.J., Naug H.L., Nikbakht E., Zhang P., McCormack J. The impact of MTHFR 677 C/T genotypes on folate status markers: a meta-analysis of folic acid intervention studies. Eur. J Nutr 2017, 56, 247-260. [CrossRef]

- Yan J., Wang W., Gregory J.F., III, Malysheva O., Brenna J.T., Stabler S.P., Allen R.H., Caudill M.A. MTHFR C677T genotype influences the isotopic enrichment of one-carbon metabolites in folate-compromised men consuming d9-choline. Am. J Clin Nutr. 2011, 93, 348-355. [CrossRef]

- Vance D.E., Ridgway N.D. The methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine. Prog. Lipid Res. 1988, 27, 61-79. [CrossRef]

- DeLong C.J., Hicks A.M., Cui Z. Disruption of choline methyl group donation for phosphatidylethanolamine methylation in hepatocarcinoma cells. J Biol. Chem 2002, 277, 17217-17225. [CrossRef]

- Vance D.E., Walkey C.J., Cui Z. Phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase from liver. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1997, 1348, 142-150. [CrossRef]

- Stead L.M., Brosnan J.T., Brosnan M.E., Vance D.E., Jacobs R.L. Is it time to reevaluate methyl balance in humans? Am. J Clin Nutr. 2006, 83, 5-10. [CrossRef]

- Shields D.J., Lingrell S., Agellon L.B., Brosnan J.T., Vance D.E. Localization-independent regulation of homocysteine secretion by phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferase. J Biol. Chem 2005, 280, 27339-27344. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs R.L., Stead L.M., Devlin C., Tabas I., Brosnan M.E., Brosnan J.T., Vance D.E. Physiological regulation of phospholipid methylation alters plasma homocysteine in mice. J Biol. Chem 2005, 280, 28299-28305. [CrossRef]

- Jacobs R.L., Devlin C., Tabas I., Vance D.E. Targeted deletion of hepatic CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase alpha in mice decreases plasma high density and very low density lipoproteins. J Biol Chem 2004, 279, 47402-47410. [CrossRef]

- Schwahn B.C., Wendel U., Lussier-Cacan S., Mar M.H., Zeisel S.H., Leclerc D., Castro C., Garrow T.A., Rozen R. Effects of betaine in a murine model of mild cystathionine-beta-synthase deficiency. Metabolism 2004, 53, 594-599. [CrossRef]

- Schwahn B.C., Chen Z., Laryea M.D., Wendel U., Lussier-Cacan S., Genest J., Jr., Mar M.H., Zeisel S.H., Castro C., Garrow T. et al. Homocysteine-betaine interactions in a murine model of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency. FASEB J 2003, 17, 512-514. [CrossRef]

- Watkins S.M., Zhu X., Zeisel S.H. Phosphatidylethanolamine-N-methyltransferase activity and dietary choline regulate liver-plasma lipid flux and essential fatty acid metabolism in mice. J Nutr 2003, 133, 3386-3391. [CrossRef]

- DeLong C.J., Shen Y.J., Thomas M.J., Cui Z. Molecular distinction of phosphatidylcholine synthesis between the CDP-choline pathway and phosphatidylethanolamine methylation pathway. J Biol. Chem 1999, 274, 29683-29688. [CrossRef]

- Augustin P., Hromic A., Pavkov-Keller T., Gruber K., Macheroux P. Structure and biochemical properties of recombinant human dimethylglycine dehydrogenase and comparison to the disease-related H109R variant. FEBS J 2016, 283, 3587-3603. [CrossRef]

- Robinson J.L., McBreairty L.E., Randell E.W., Harding S.V., Bartlett R.K., Brunton J.A., Bertolo R.F. Betaine or folate can equally furnish remethylation to methionine and increase transmethylation in methionine-restricted neonates. J Nutr Biochem. 2018, 59, 129-135. [CrossRef]

- Barak A.J., Kemmy R.J. Methotrexate effects on hepatic betaine levels in choline-supplemented and choline-deficient rats. Drug Nutr. Interact. 1982, 1, 275-278.

- Barak A.J., Tuma D.J., Beckenhauer H.C. Methotrexate hepatotoxicity. J Am Coll. Nutr 1984, 3, 93-96. [CrossRef]

- Freeman-Narrod M., Narrod S.A., Custer R.P. Chronic toxicity of methotrexate in rats: partial to complete projection of the liver by choline: Brief communication. J Natl. Cancer Inst. 1977, 59, 1013-1017. [CrossRef]

- Pomfret E.A., daCosta K.A., Zeisel S.H. Effects of choline deficiency and methotrexate treatment upon rat liver. J Nutr Biochem. 1990, 1, 533-541. [CrossRef]

- Svardal A.M., Ueland P.M., Berge R.K., Aarsland A., Aarsaether N., Lonning P.E., Refsum H. Effect of methotrexate on homocysteine and other sulfur compounds in tissues of rats fed a normal or a defined, choline-deficient diet. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 1988, 21, 313-318. [CrossRef]

- Poirier L.A., Grantham P.H., Rogers A.E. The effects of a marginally lipotrope-deficient diet on the hepatic levels of S-adenosylmethionine and on the urinary metabolites of 2-acetylaminofluorene in rats. Cancer Res. 1977, 37, 744-748.

- Barak A.J., Kemmy R.J., Tuma D.J. The effect of methotrexate on homocysteine methylating agents in rat liver. Drug Nutr Interact. 1982, 1, 303-306.

- Shivapurkar N., Poirier L.A. Tissue levels of S-adenosylmethionine and S-adenosylhomocysteine in rats fed methyl-deficient, amino acid-defined diets for one to five weeks. Carcinogenesis 1983, 4, 1051-1057. [CrossRef]

- Zeisel S.H., Zola T., daCosta K.A., Pomfret E.A. Effect of choline deficiency on S-adenosylmethionine and methionine concentrations in rat liver. Biochem. J 1989, 259, 725-729.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).