1. Introduction

Galactomannan (Gal) is a natural polymer found mainly in the endosperm of leguminous seeds [

1,

2]. In general, galactomannan presents in its structure mannose units, which compose the main chain, and galactose units in the branches [

3], being characterized by high solubility in solutions [

4] and chemical stability in a wide range of pH due to non-ionic character [

5]. It can be applied as a thickener/stabilizer in the food industry [

6] and in medical applications, like in the diagnosis of invasive fungal infections [

7,

8,

9] and the diagnosis of Aspergillosis [

10].

The interaction of natural glue with different biological systems has been investigated [

11,

12], as polysaccharides are the raw material of interest for this application. The thermal properties of these polysaccharides, especially the presence of water, are a complex and essential process to determine the ideal application and destination for the material [

13] since it can be submitted to thermal treatments during the preparation or use [

14]. Thus, it is interesting to develop new glues of natural origin in medical applications due to their biocompatibility. In civil construction, this material resists thermal expansion and bonds to the substrate [

15].

The application of different natural polymers as glue/adhesive is observed in the literature, such as casein [

16], soy protein [

17], chitosan [

18], cellulose [

19], collagen [

20], and others. It is also known that glycerol-based polymers have potential applications as more ecological adhesives [

21]. In this context, this research aims to study the thermal behavior of the glue produced from galactomannan from the seeds of Adenanthera pavonina L. and glycerol through the analysis of mass loss events, thermal decomposition, and the process of glue glazing. The structure and composition of polysaccharides are expected to influence the thermodynamic behavior of biopolymers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Galactomannan Source and Extraction

The seeds of Adenanthera pavonina L. were collected in the Fortaleza (Ceará) region in Brazil, while reagents and solvents were used without prior purification. The extraction of galactomannan was carried out following the method previously described by Macêdo et al. [

6]. The seeds of Adenanthera pavonina L. were heated in distilled water for 30 minutes after boiling and then swelled after 24 hours. Subsequently, the obtained endosperm was manually separated from the tegument and the embryo, dried with acetone (purity 100.0 %, Synth), and ground to powder. The powder obtained was stored for posterior preparation of galactomannan/glycerol solutions.

2.2. Galactomannan Solutions of 5.0 %

Galactomannan (Gal) was obtained by solubilizing the endosperm in a solution pre-adjusted to pH 3.0 with acetic acid. Then, four grams of galactomannan were homogenized in 100 mL of 0.1% acetic acid solution. The solution was homogenized (in moderate stirring) and then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 20 minutes. The precipitate was removed, and 0.2 mL of potassium sorbate (purity ≥ 99.0%, Sigma / Aldrich) was added to the supernatant. The resulting solution was stored under refrigeration.

2.3. Galactomannan/Glycerol Solutions

Twenty grams of Gal 5.00 % were weighed in different flasks, and 0.2 mL of 0.3% potassium sorbate solution was added in both. After that, three solutions with glycerol (purity ≥ 99.5%, Sigma/Aldrich) were prepared. Samples were classified according to the quantity of glycerol added: Gal5.00 - solutions without glycerol (0.00 mL), Gal5.05 - solutions with 0.50 mL of glycerol, and Gal5.10 - solutions with 1.00 mL of glycerol. Each solution was heated until it reached the consistency of gum.

2.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR analysis was used as an effective tool to gain information on the vibrational of the galactomannan-glycerol solutions (Gal5.00 – Gal5.10). FTIR spectra were determined using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (SHIMATZU FTIR-283B). The gums were ground with spectroscopic grade potassium bromide (KBr) powder and then pressed into pellets for measurement in the wavenumber range of 400 and 4000 cm-1.

2.5. Thermogravimetry (TG)

TG and Derivative Thermogravimetry (DTG) analysis were used to characterize thermal decomposition and evaluate the stability of films. The TG measurements were carried out in synthetic atmosphere air N2 (flow rate of 50 mL min-1) using a Shimadzu TGA-50H equipment calibrated with Indium as standard. The analyses started at 30 °C to 600 °C, with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. The samples were weighed (5 ± 0.1 mg) in alumina crucibles.

2.6. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC was used to investigate thermal transitions. The DSC measurements were carried out in an N2 atmosphere (flow rate of 50 mL.min-1) using Shimadzu DSC-50 calibrated with Indium as standard. The analyses started at 30 °C to 400 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C min−1. The samples were weighed (5 ± 0.1 mg) in alumina pans. The enthalpy was calculated using the area of the peaks between the onset temperature and the end set temperature.

3. Results

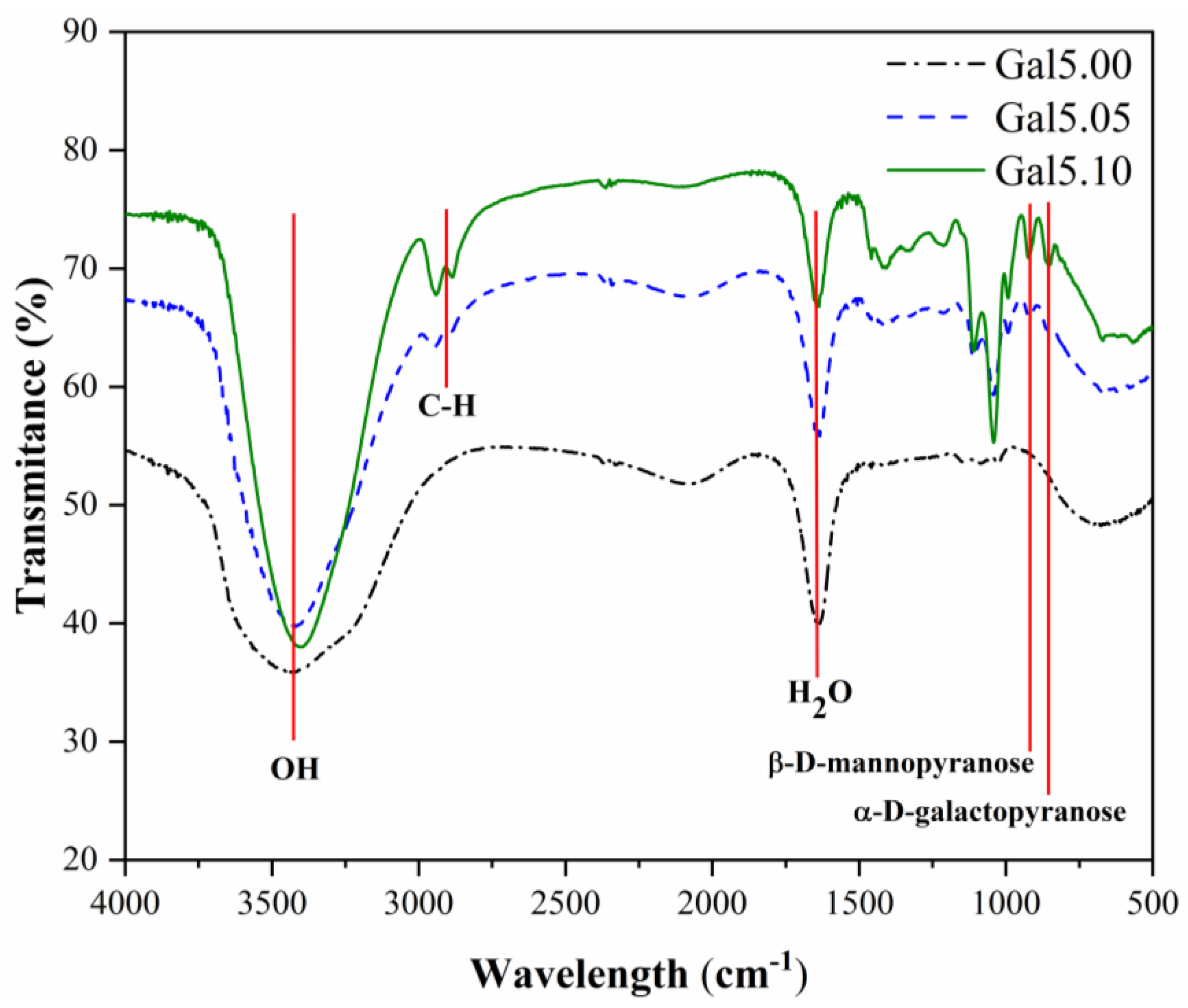

The characteristic vibrations of the galactomannan and galactomannan-glycerol solutions (Gal5.00, Gal5.05, and Gal5.10) were analyzed in the spectral region from 4000 to 500 cm

-1 by FTIR (

Figure 1).

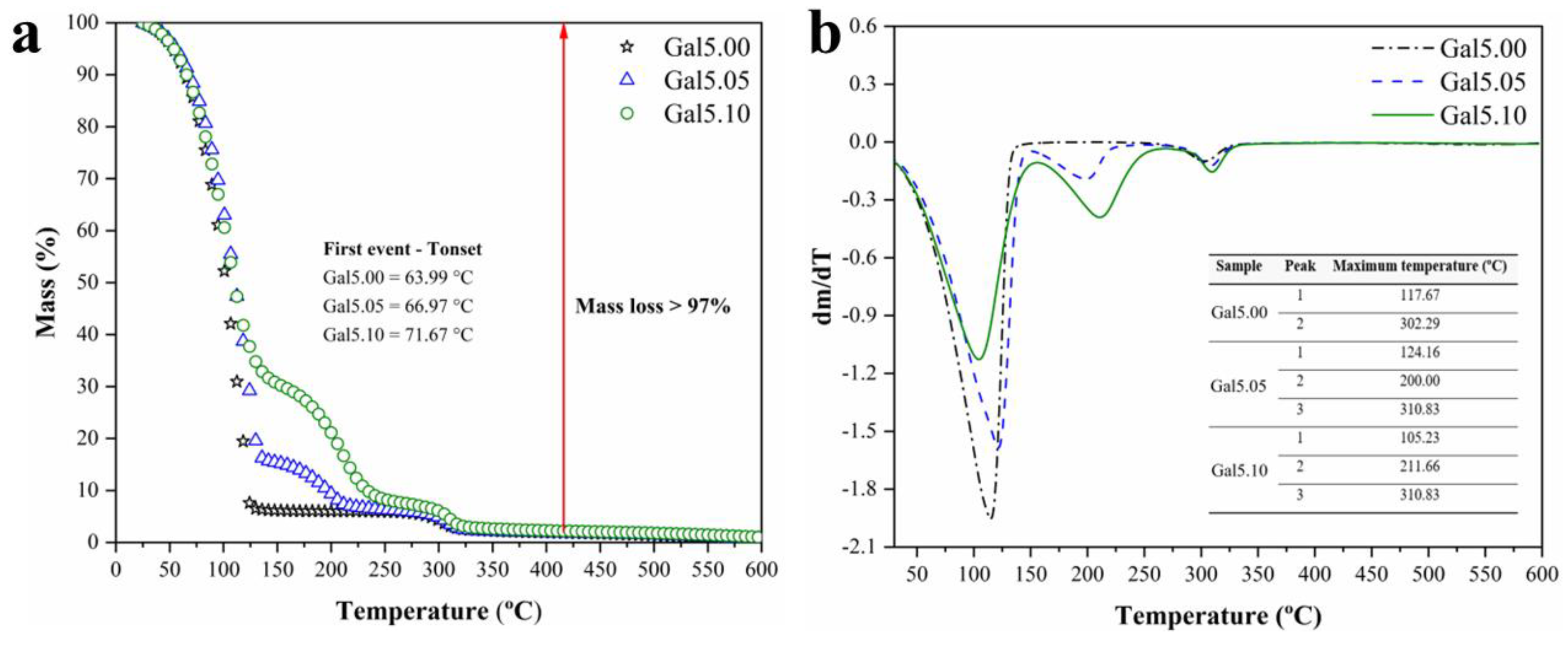

Figure 2 (a, b) shows the TG-DTG curves of Gal5.00, Gal5.05 and Gal5.10 samples. Gal5.0, two mass loss events were verified, while for Gal5.05 and Gal5.1, three events were observed.

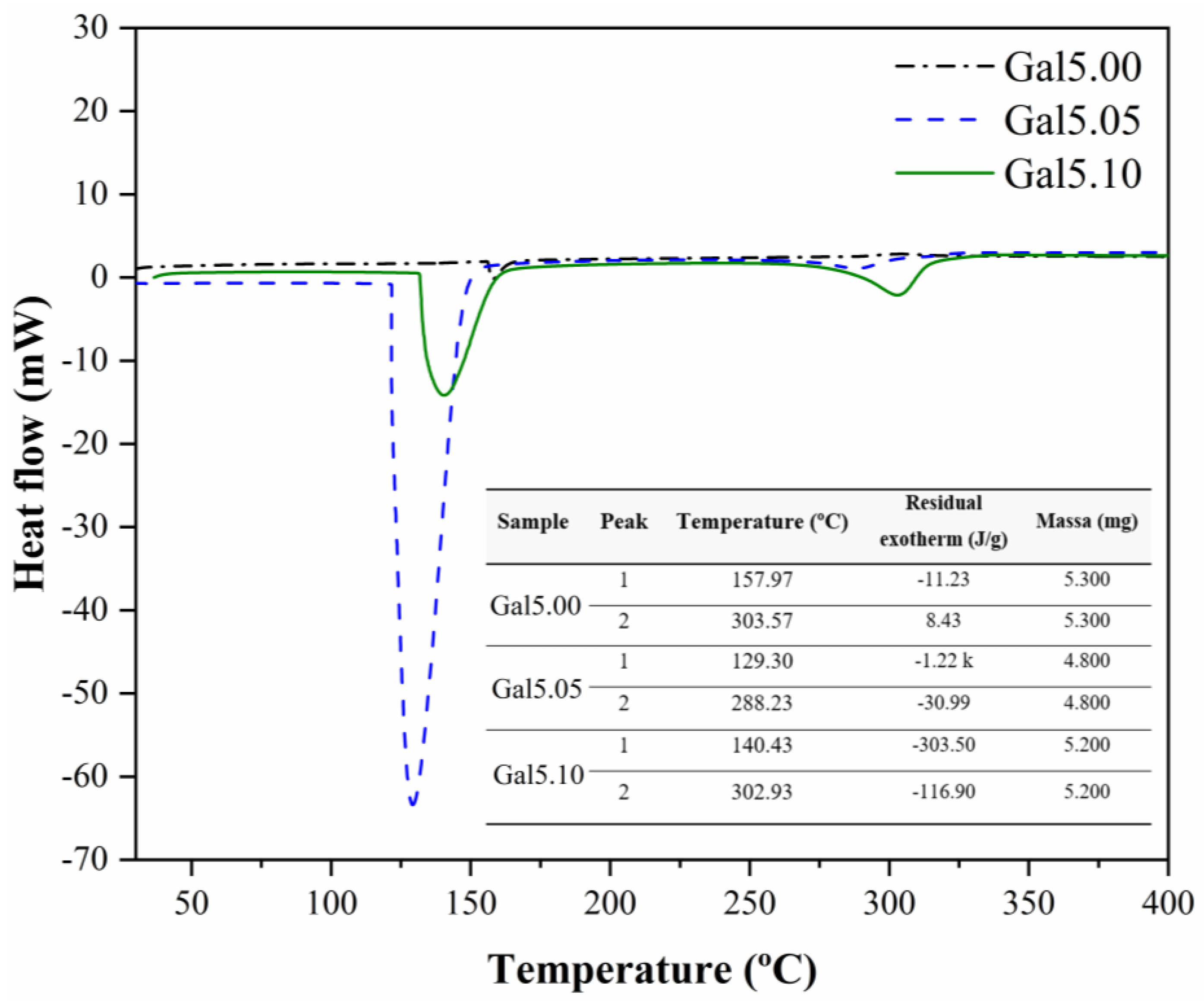

The DSC results for the samples Gal5.00, Gal5.05, and Gal5.10 are present in

Figure 3. The DSC curve of the Gal5.0 sample shows an endothermic peak at 157.97 °C and an exothermic peak at 303.57 °C, respectively. The endothermic peak is related to the water loss process, and the exothermic peak is associated with thermal degradation, considering that these processes occur at similar temperatures in TG (

Figure 2a).

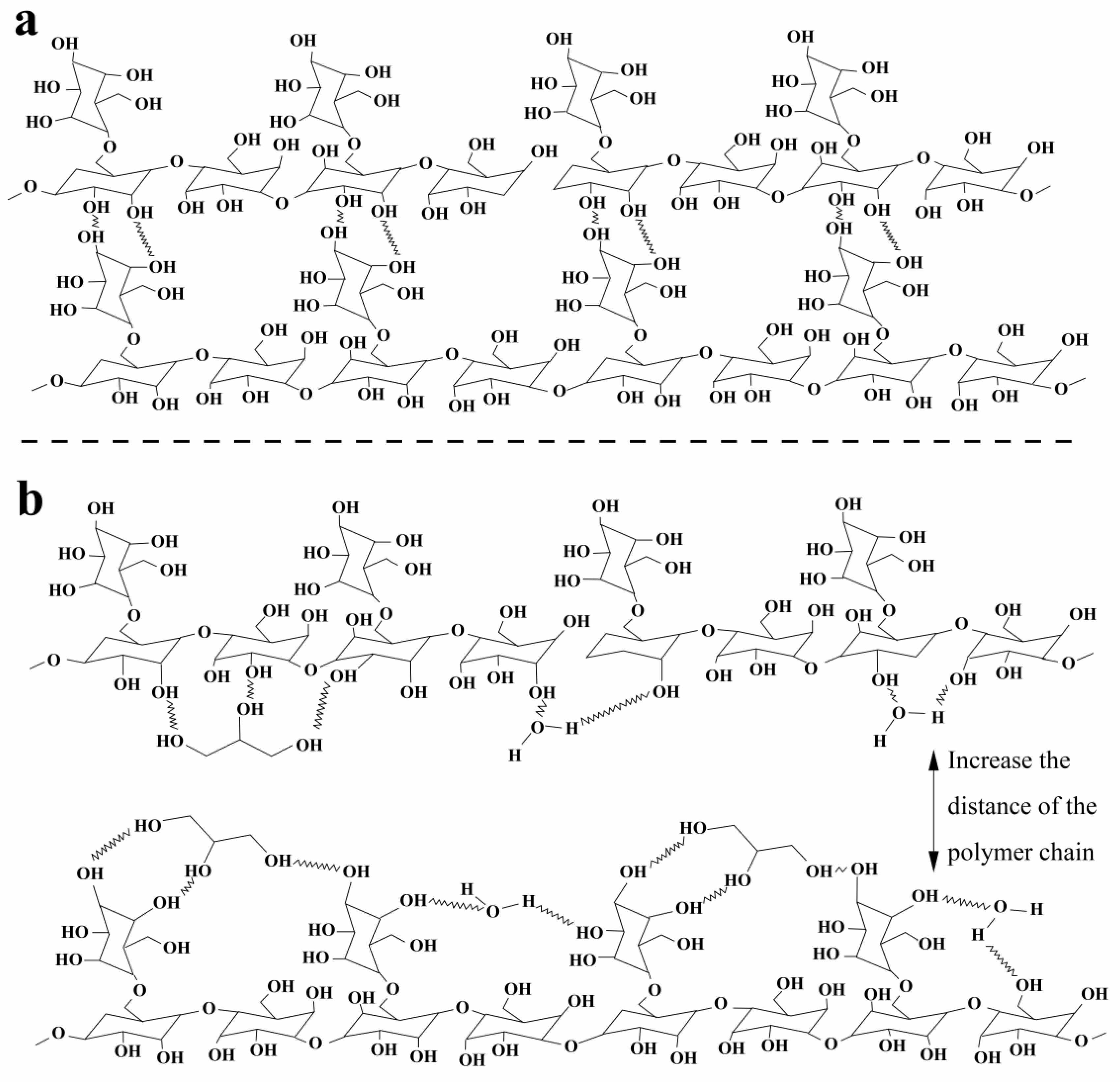

Figure 4 presents a schematic representation of the interaction of galactomannan with and without the presence of a plasticizer.

4. Discussion

According to the FTIR spectrum (

Figure 1), the stretching in the region 3381–3430 cm

−1 has been attributed to OH groups [

22]. The 2081, 2073, and 2089 cm−1 peaks indicate combination bands, whereas the bands observed at 1637 and 1645 cm−1 correspond to the associated water [

23]. An absorption band was detected in the region around 1483 - 1409 cm−1, attributed to CH2 deformation [

24]. The peaks between 800 and 1200 cm

−1 represented the highly coupled C-C-O, C-OH, and C-O-C stretching modes characteristic of carbohydrate polymers [

23,

24]. The region between 2953 and 2886 cm

−1 is attributed to C–H stretching modes [

24]. The characteristic absorption bands of galactomannan that indicate the presence of β-D-mannopyranose units and α-D-galactopyranose units were observed around 922 and 854 cm-1 [

23]. The galactomannan bands in the Gal sample could not be analyzed due to their low concentration and the fact that the spectrum was obtained in solution.

The effect of adding glycerol on Gal is evidenced in the FTIR spectra of the samples by changes in the characteristic peaks observed at regions between 2953 and 2886 cm

−1 and 1409 and 854 cm

−1. Other researchers have observed this behavior previously. According to the literature [

25,

26], the increasing glycerol concentration increases the area corresponding to the O-H stretching vibration region, associated with free, inter, and intra-molecular bound hydroxyl groups (3430-3381 cm

−1). This phenomenon arises from glycerol’s hydrophilic nature and the formation of hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl groups of Gal and glycerol [

25]. Thus, glycerol does not merely physically blend with Gal but actively modifies its hydrogen-bonding network by replacing Gal-Gal interactions with Gal-glycerol interactions. These changes indicate effective plasticization, as the introduction of glycerol disrupts the native intermolecular interactions between Gal chains.

Moreover, the bands at 2953, 2888, and 2886 cm

−1 correspond to the stretching vibration of the C-H bond, which only appears in the glycerol solutions, confirming the more intense C-H stretching vibration in these solutions. Changes in the frequency range between 1409 and 800 cm

−1 are also observed when glycerol is added to galactomannan solutions. For example, bending the C-O-H bond at 1409 cm

−1 and the stretching vibration of the C-O bond at 1111 cm-1 may be attributed to a primary alcohol. The band at 1046 cm-1 corresponds to the stretching vibration of C-O, which appears in all samples; however, it increases intensity for galactomannan solutions with 0.5 and 1.0 mL of glycerol [

25].

For the TG-DTG curves (

Figure 2) of the Gal5.00 sample, the first event starts near 26.61 °C, with a loss percentage of approximately 95% and a maximum temperature of 117.67 °C, which can be attributed to water loss according to other works in galactomannans [

27,

28,

29]. The second event begins at 267.77 °C, with a maximum temperature of 302.29 °C and a loss of approximately 4% of the mass, suggesting the disintegration of the galactomannan macromolecular chains, followed by the degradation of the hexose rings according to the literature [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

Three mass loss events were observed in similar temperature ranges for the TG-DTG curves of the Gal5.05 and Gal5.1 samples. The first curve, as in Gal5.0, is associated with the volatilization of water. Both Gal5.05 and Gal5.1 show the beginning of mass loss at 25.95 °C. Maximum temperatures for Gal5.05 and Gal5.1 are 124.16 °C and 105.23 °C, respectively. It was observed that the mass loss in both samples differs due to the presence of glycerol; Gal5.0 presented a water loss of 84%, and Gal5.1 presented a water loss of 66%. The event is associated with glycerol volatilization, which started at approximately 147.5 °C and 153.3 ºC for Gal5.05 and Gal5.10, and maximum temperature of 200 °C and 211.66 °C, respectively, with mass losses of 8.92% and 20.5%, respectively [

30,

32,

33]. The third event is attributed to the thermal decomposition of galactomannan. This process occurs in the same temperature range and presents around the same gal mass.

No exothermic transition was found in samples Gal5.05 and Gal5.10 (

Figure 3). Peak temperatures for the second endothermic transition occurred at 288.23 °C for G05 and 302.93 °C for Gal5.1. The absence of an exothermic peak at the thermal degradation temperature of samples Gal5.05 and Gal5.10 may be related to the masking of the exothermic peak by the overlap of the endothermic peak associated with the volatilization of glycerol. At the initial temperatures, a change in the heat capacity, characterized by the formation of a curve without the formation of peaks, is observed in Gal5.00. It is suggested that the occurrence of this curve may indicate the process of glue glazing. In the other samples, these transitions are not observed. It is estimated that this occurred due to the presence of the plasticizer.

The water and glycerol inserted in the glue act as a plasticizer, reducing the interaction between the polymer chains. These plasticizers’ absence or low concentrations promote the vitrification of galactomannan chains. At present, water and glycerol interact intermolecularly, making hydrogen bonds with the -OH groups of Gal, preventing chain approximation (

Figure 4) and vitrification. Consequently, after the volatilization of the water, glycerol still exists in Gal5.05 and Gal5.10; consequently, the polymer chains will remain in a malleable state instead of vitrifying.

5. Conclusions

Spectroscopic and thermal data agree that glycerol modifies the Gal hydrogen bond network, replacing Gal-Gal interactions with more dynamic Gal-glycerol interactions. This mechanism not only explains the inhibition of vitrification but also supports the use of Gal-based materials with tunable thermomechanical properties for specific applications. In the context of biomedical adhesives, glycerol plasticization possibly improves flexibility and long-term adhesion, in addition to preserving biocompatibility. To prove its efficacy as a biomedical adhesive, complementary studies are essential.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design: Beatriz da Silva Batista (conceptualization, data curation, original draft, formal analysis); Rômicy Dermondes Souza (conceptualization, data curation, original draft, methodology); Maria Alexsandra de Sousa Rios (investigation, formal analysis, validation); Lincoln Almeida Cavalcante (conceptualization, formal analysis); Walajhone Oliveira Pereira (formal analysis, methodology); Selma Elaine Mazzetto (investigation, methodology); Filipe Amaral (investigation, data curation, validation); Fernando Mendes (supervision validation, review editing); and, Ana Angélica Mathias Macêdo (project administration, resource, funding acquisition investigation, validation, review editing).

Funding

The authors are grateful to the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and Foundation for the Support of Research and Scientific and Technological Development of Maranhão (FAPEMA) agencies for funding the project. The authors acknowledge the support of FCT - Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., within the scope of the project’s LA/P/0037/2020, UIDP/50025/2020, and UIDB/50025/2020 of the Associate Laboratory Institute of Nanostructures, Nanomodelling and Nanofabrication-i3N. This research was funded by FCT/MCTES UIDP/05608/2020 (

https://doi.org/10.54499 /UIDP/05608/2020) and UIDB/05608/2020 (

https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/05608/2020). This work received financial support from the Polytechnic University of Coimbra within the scope of Regulamento de Apoio à Publicação Científica dos Trabalhadores do Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra (Despacho n.º 4654/2024).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological Development), FAPEMA (Foundation for the Support of Research and Scientific and Technological Development of Maranhão) and FCT (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia) for support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Gal |

Galactomannan |

| Gal5.00 |

Gal solutions (5.00 %) without glycerol (0.00 mL) |

| Gal5.05 |

Gal solutions (5.00 %) with glycerol (0.50 mL) |

| Gal5.10 |

Gal solutions (5.00 %) with glycerol (1.00 mL) |

| FTIR |

Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| TG |

Thermogravimetry |

| DTG |

Derivative Thermogravimetry |

| DSC |

Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

References

- Gomes RF, Lima LRM, Feitosa JPA, Paula HCB, de Paula RCM. Influence of galactomannan molar mass on particle size galactomannan-grafted-poly-N-isopropylacrylamide copolymers. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 156, 446–53. [CrossRef]

- Li R, Tang N, Jia X, Nirasawa S, Bian X, Zhang P, et al. Isolation, physical, structural characterization and in vitro prebiotic activity of a galactomannan extracted from endosperm splits of Chinese Sesbania cannabina seeds. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 162, 1217–26. [CrossRef]

- Jian H-L, Lin X-J, Zhang W-A, Zhang W-M, Sun D-F, Jiang J-X. Characterization of fractional precipitation behavior of galactomannan gums with ethanol and isopropanol. Food Hydrocoll 2014, 40, 115–21. [CrossRef]

- Souza NDG, Freire RM, Cunha AP, da Silva MAS, Mazzetto SE, Sombra ASB, et al. A new magnetic nanobiocomposite is based on galactomannan/glycerol and superparamagnetic nanoparticles. Mater Chem Phys 2015, 156, 113–20. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Lei F, He L, Xu W, Jiang J. Physicochemical characterization of galactomannans extracted from seeds of Gleditsia sinensis Lam and fenugreek. Comparison with commercial guar gum. Int J Biol Macromol 2020, 158, 1047–54. [CrossRef]

- Macêdo AAM, Sombra ASB, Mazzetto SE, Silva CC. Influence of the polysaccharide galactomannan on the dielectrical characterization of hydroxyapatite ceramic. Compos Part B Eng 2013, 44, 95–99. [CrossRef]

- Hachem RY, Kontoyiannis DP, Chemaly RF, Jiang Y, Reitzel R, Raad I. Utility of Galactomannan Enzyme Immunoassay and (1,3) β- <scp>d</scp> -Glucan in Diagnosis of Invasive Fungal Infections: Low Sensitivity for Aspergillus fumigatus Infection in Hematologic Malignancy Patients. J Clin Microbiol 2009, 47, 129–33. [CrossRef]

- Maertens J, Maertens V, Theunissen K, Meersseman W, Meersseman P, Meers S, et al. Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid Galactomannan for the Diagnosis of Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Patients with Hematologic Diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2009, 49, 1688–93. [CrossRef]

- Wheat LJ, Walsh TJ. Diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis by galactomannan antigenemia detection using an enzyme immunoassay. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2008, 27, 245–51. [CrossRef]

- Husain S, Paterson DL, Studer SM, Crespo M, Pilewski J, Durkin M, et al. Aspergillus Galactomannan Antigen in the Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid for the Diagnosis of Invasive Aspergillosis in Lung Transplant Recipients. Transplantation 2007, 83, 1330–6. [CrossRef]

- McDermott MK, Chen T, Williams CM, Markley KM, Payne GF. Mechanical Properties of Biomimetic Tissue Adhesive Based on the Microbial Transglutaminase-Catalyzed Crosslinking of Gelatin. Biomacromolecules 2004, 5, 1270–9. [CrossRef]

- Takahashi A, Sato Y, Uno S, Pereira PN. , Sano H. Effects of mechanical properties of adhesive resins on bond strength to dentin. Dent Mater 2002, 18, 263–8. [CrossRef]

- Werner K, Pommer L, Broström M. Thermal decomposition of hemicelluloses. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 2014, 110, 130–7. [CrossRef]

- Soares RMD, Lima AMF, Oliveira RVB, Pires ATN, Soldi V. Thermal degradation of biodegradable edible films based on xanthan and starches from different sources. Polym Degrad Stab 2005, 90, 449–54. [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson AR, Iglauer S. Adhesion of construction sealants to polymer foam backer rod used in building construction. Int J Adhes Adhes 2006, 26, 555–66. [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenbrunner R, Barbu MC, Petutschnigg A, Tudor EM. Water-resistant casein-based adhesives for veneer bonding in biodegradable ski cores. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Lamaming SZ, Lamaming J, Rawi NFM, Hashim R, Kassim MHM, Hussin MH, et al. Improvements and limitation of soy protein-based adhesive: A review. Polym Eng Sci 2021, 61, 2393–405. [CrossRef]

- Mati-Baouche N, Elchinger PH, De Baynast H, Pierre G, Delattre C, Michaud P. Chitosan as an adhesive. Eur Polym J 2014, 60, 198–212. [CrossRef]

- Gardner DJ, Oporto GS, Mills R, Samir MASA. Adhesion and surface issues in cellulose and nanocellulose. J Adhes Sci Technol 2008, 22, 545–67. [CrossRef]

- Baik SH, Kim JH, Cho HH, Park SN, Kim YS, Suh H. Development and analysis of a collagen-based hemostatic adhesive. J Surg Res 2010, 164, e221–8. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo LRF, Nepomuceno NC, Melo JDD, Medeiros ES. Glycerol-based polymer adhesives reinforced with cellulose nanocrystals. Int J Adhes Adhes 2021;110. [CrossRef]

- Maitra J, Shukla VK. Cross-linking in Hydrogels - A Review. Am J Polym Sci 2014, 4, 25–31.

- Rodriguez-Canto W, Chel-Guerrero L, Fernandez VVA, Aguilar-Vega M. Delonix regia galactomannan hydrolysates: Rheological behavior and physicochemical characterization. Carbohydr Polym 2019, 206, 573–82. [CrossRef]

- Mudgil D, Barak S, Khatkar BS. X-ray diffraction, IR spectroscopy and thermal characterization of partially hydrolyzed guar gum. Int J Biol Macromol 2012, 50, 1035–9. [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira MA, Souza BWS, Teixeira JA, Vicente AA. Effect of glycerol and corn oil on physicochemical properties of polysaccharide films – A comparative study. Food Hydrocoll 2012, 27, 175–84. [CrossRef]

- Antoniou J, Liu F, Majeed H, Zhong F. Characterization of tara gum edible films incorporated with bulk chitosan and chitosan nanoparticles: A comparative study. Food Hydrocoll 2015, 44, 309–19. [CrossRef]

- Varma AJ, Kokane SP, Pathak G, Pradhan SD. Thermal behavior of galactomannan guar gum and its periodate oxidation products. Carbohydr Polym 1997, 32, 111–4. [CrossRef]

- Vendruscolo F, da Silva Ribeiro C, Esposito E, Ninow JL. Protein Enrichment of Apple Pomace and Use in Feed for Nile Tilapia. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 2009, 152, 74–87. [CrossRef]

- Zohuriaan, M. , Shokrolahi F. Thermal studies on natural and modified gums. Polym Test 2004, 23, 575–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira MA, Souza BWS, Simões J, Teixeira JA, Domingues MRM, Coimbra MA, et al. Structural and thermal characterization of galactomannans from non-conventional sources. Carbohydr Polym 2011, 83, 179–85. [CrossRef]

- Giancone T, Torrieri E, Di Pierro P, Cavella S, Giosafatto CVL, Masi P. Effect of Surface Density on the Engineering Properties of High Methoxyl Pectin-Based Edible Films. Food Bioprocess Technol 2011, 4, 1228–36. [CrossRef]

- Martins VCA, Goissis G. Colágeno Aniônico como Matriz para Deposição Orientada de Minerais de Fosfato de Cálcio. Polim Ciência e Tecnol 1996:30–7.

- Martins JT, Cerqueira MA, Bourbon AI, Pinheiro AC, Souza BWS, Vicente AA. Synergistic effects between κ-carrageenan and locust bean gum on physicochemical properties of edible films made thereof. Food Hydrocoll 2012, 29, 280–9. [CrossRef]

- Mu C, Guo J, Li X, Lin W, Li D. Preparation and properties of dialdehyde carboxymethyl cellulose crosslinked gelatin edible films. Food Hydrocoll 2012, 27, 22–9. [CrossRef]

- Liyanage S, Abidi N, Auld D, Moussa H. Chemical and physical characterization of galactomannan extracted from guar cultivars (Cyamopsis tetragonolobus L.). Ind Crops Prod 2015, 74, 388–96. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).