Introduction

99mTc-pertechnetate absorbed from the upper rectum and terminal colon in per-rectal portal scintigraphy (PRPS) shows a three- to fourfold increase in the liver transit time from the portal vein to the right atrium (LTT), and in the circulation time from the right heart (more precisely – the right atrium) to the liver (RHLT) - which mainly includes the transpulmonary transit time [

1]. In contrast, a prolonged LTT was not observed for

99mTc-pertechnetate administered into the spleen during trans-splenic portal scintigraphy (TSPS) [

2,

3], and transpulmonary transit time was not increased for

99mTc-pertechnetate given intravenously in radionuclide angiocardiography [

4]. This indicates that the absorption of

99mTc-pertechnetate in the colorectum is essential for slowing the radiotracer flow through the liver and lungs, as noted in PRPS. Since

99mTc-pertechnetate is an artificially produced substance, we hypothesize that the reduced hepatic and pulmonary transit rates of colorectal-absorbed

99mTc-pertechnetate may result from an unidentified defense mechanism activated against unknown substances absorbed from the gut, which the body recognizes as potentially hazardous chemicals (PHCs). The low LTTs of the radiotracers injected into the spleen during TSPS suggest that

99mTc-pertechnetate cannot directly trigger first-pass vasoconstriction in the liver. The normal range observed for transpulmonary transit time of

99mTc-pertechnetate administered intravenously during radionuclide angiocardiography indicates that

99mTc-pertechnetate cannot directly cause first-pass vasoconstriction in the lungs. Therefore, other substances are responsible for triggering the hepatic and pulmonary vasoconstriction during PRPS. Therefore, we hypothesize that vasoactive agents (VAs) released from the colorectal wall during the absorption of

99mTc-pertechnetate are the direct cause of the hepatic and pulmonary vasoconstriction observed in PRPS. This protective physiological response must target PHCs, which are accidentally ingested with food. It also suggests that this response can be triggered by certain medications or synthetic food additives taken orally.

A sudden decrease in portal flow, similar to that observed with

99mTc-pertechnetate in PRPS, has been reported during the early stages of liver metastasis in colorectal cancer (CRC), but not in cancers outside the intestine [

5,

6,

7]. The activation of this vasoactive mechanism, which is specific to CRC, appears to be closely linked to substances released from the colorectal wall, much like the anti-PHC response triggered at PRPS against

99mTc-pertechnetate.

Our study was designed to examine the first-pass vasoactive response to 99mTc-pertechnetate in the liver and lungs, as observed at PRPS. Using the dynamic data from time-activity curves generated at LAS, we also aimed to determine whether a radiotracer reaching the digestive tract mucosa via arterial flow can initiate the anti-PHC response in the liver.

This study could be beneficial for pharmacokinetics, toxicology, and the food industry, and it may also have implications for oncology, especially in CRC. Identifying the VAs can help in early diagnosis and targeted treatment of CRCs in patients at high risk of metastasis [

5,

8]. Targeting either the VAs or their receptors with specific medications may slow down or prevent the spread of CRC to the liver and potentially to the lungs, thereby increasing life expectancy for patients with this disease.

Materials and Methods

Patient Population:

All patients and healthy volunteers provided informed consent before participation, and the confidentiality of their data was maintained throughout the study. The hospital's ethics committee approved the nuclear medicine procedures and the scientific use of the laboratory database. The procedures involved subjects aged 18 to 85 who were required to fast for 12 hours prior to participation. We applied the following exclusion criteria, focusing on conditions that could affect blood flow transit times (TTs) through the liver and lungs: a) Patients diagnosed with heart failure, intracardiac or portosystemic shunts, or pulmonary illnesses were excluded from the RHLT calculation. b) Patients diagnosed with diffuse liver disease, hemangiomas larger than 4 cm in diameter, or portosystemic shunts were excluded from the LTT calculation; c) Patients with hyperthyroidism were excluded from the RHLT calculation in LAS with 99mTc-pertechnetate. d) Subjects who received unsuccessful bolus injections at LAS were also excluded; e) Additionally, we removed cases where time-activity curves showed low resolution or where the difference between the TTs evaluated by two experienced observers exceeded 15%.

The LAS studies involved patients referred for thyroid or skeletal scans who received the standard dose of radiotracer given as a bolus. This selection enabled RHLT and LTT assessment without unnecessary radiation exposure.

Imaging Studies

a) In previous studies, we performed PRPS using the methodology developed by Shiomi et al. [

6]. We introduced two new parameters, LTT and RHLT, to assess the transit of

99mTc-pertechnetate through the liver and lungs following colorectal absorption.

b) We used the methodology proposed by Leveson and Sarper to perform LAS [

9,

10]. After the intravenous antecubital bolus administration of the radiotracer, we recorded serial anteroposterior and posteroanterior images of the chest and upper abdomen every second for one minute. The bolus quality was verified by measuring the time from the half-maximum value to the peak of the renal curve, which must be under 8 s [

11]. To assess RHLT for

99mTc-pertechnetate, seven females and three males aged 29 to 64, who were referred for thyroid scans, underwent LAS with a dose of 150 to 185 MBq. To evaluate RHLT for

99mTc-HDP (hydroxyethylene diphosphate), we performed LAS (

Figure 1) with a dose of 300–370 MBq, in six healthy volunteers (four males and two females, aged 35–62 years) and in 43 patients referred for bone scans. Eleven patients were excluded due to low-resolution dynamic curves or incorrect bolus administration, resulting in a final analysis cohort of six controls and 32 patients: 18 males and 14 females, with ages ranging from 44 to 83 years and 33 to 72 years, respectively.

c) We introduced lower rectum transmucosal dynamic scintigraphy (LR-TMDS) as a variant of PRPS to evaluate the RHLT of

99mTc-pertechnetate injected into the submucosa of the lower rectum. Before reaching the right atrium, the radiotracer sequentially passed through the inferior rectal veins, the internal and common iliac veins, and the inferior vena cava. This pathway resembled that observed in patients with complete portal vein occlusion, as examined in PRPS, but did not involve the absorption of

99mTc-pertechnetate through the colorectal mucosa (

Figure 2). LR-TMDS was performed on four volunteers without any pathology of the lower rectum: one female and three males, aged 41 to 58 years. We injected a dose of 150–160 MBq of

99mTc-pertechnetate into the lower rectum submucosa using a proctoscope positioned 5 to 8 cm from the anus. We then captured serial anteroposterior and posteroanterior images of the chest and upper abdomen at two-second intervals for four minutes. RHLT was calculated using time-activity curves made for the right heart and left kidney regions. We focused on the start of the time-activity curve of the left kidney, as the radiotracer reached the kidneys and liver simultaneously; however, the onset of the hepatic curve was less clear.

d) We assessed LTT using LAS to determine whether the radiotracer's flow through the liver slows down when 99mTc-HDP is injected intravenously and reaches the portal circulation after passing through the mesenteric arteries and gut mucosa. LTT was measured in five healthy volunteers (three males and two females, aged 40 to 61 years) and 61 patients referred for a bone scan with 99mTc-HDP. We used a technique similar to that employed for RHLT measurement at LAS, while recording anteroposterior and posteroanterior images of the abdomen. The peak of the left kidney's time-activity curve was used to determine when the portal flow of the radiotracer entered the liver. The peak of the liver's time-activity curve indicated when the radiotracer's portal flow exited the liver. In five healthy subjects and forty patients (15 women, aged 33 to 70 years, and 25 men, aged 42 to 82 years), the peak of the hepatic curve was visible, allowing LTT to be measured. The remaining participants were excluded from the study.

We conducted LAS and LR-TMDS studies using an AnyScanS gamma camera (Mediso, Budapest, Hungary) equipped with a high-resolution, low-energy parallel collimator, as well as Nucline v2.02 and InterView-XP dedicated software. Patients were positioned in a supine posture.

Results

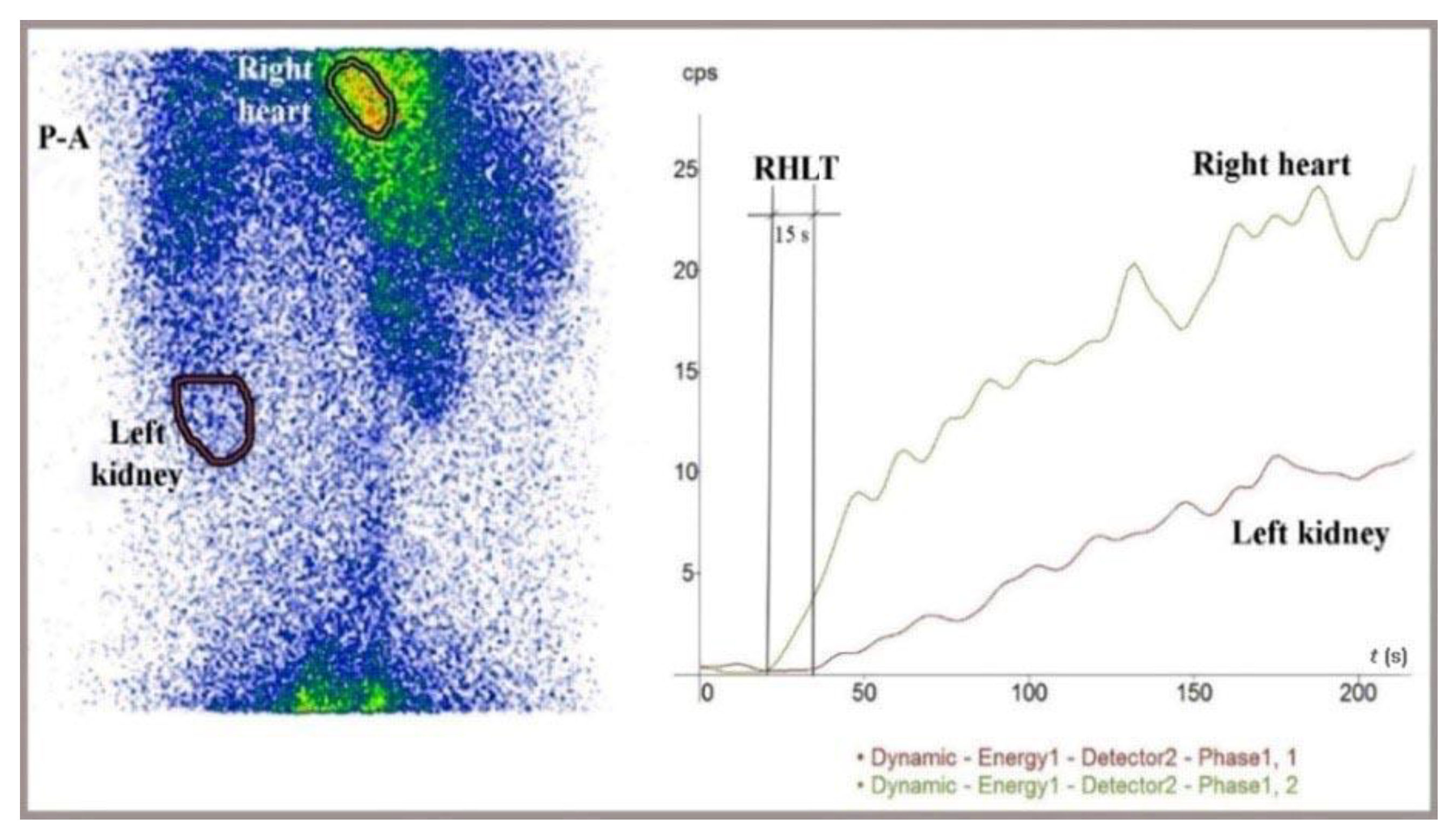

1.1. RHLT Evaluated for 99mTc-Pertechnetate in LR-TMDS

RHLT measured in LR-TMDS (

Figure 5) for

99mTc-pertechnetate injected into the lower rectum submucosa ranged from 12 to 15 s.

99mTc-pertechnetate reached the right atrium by passing through the inferior hemorrhoidal veins, iliac internal and common veins, and vena cava in sequence. This pathway resembled that of

99mTc-pertechnetate in PRPS performed in patients with complete portal vein occlusion, resulting in a significantly longer RHLT of 42 ± 1 s.

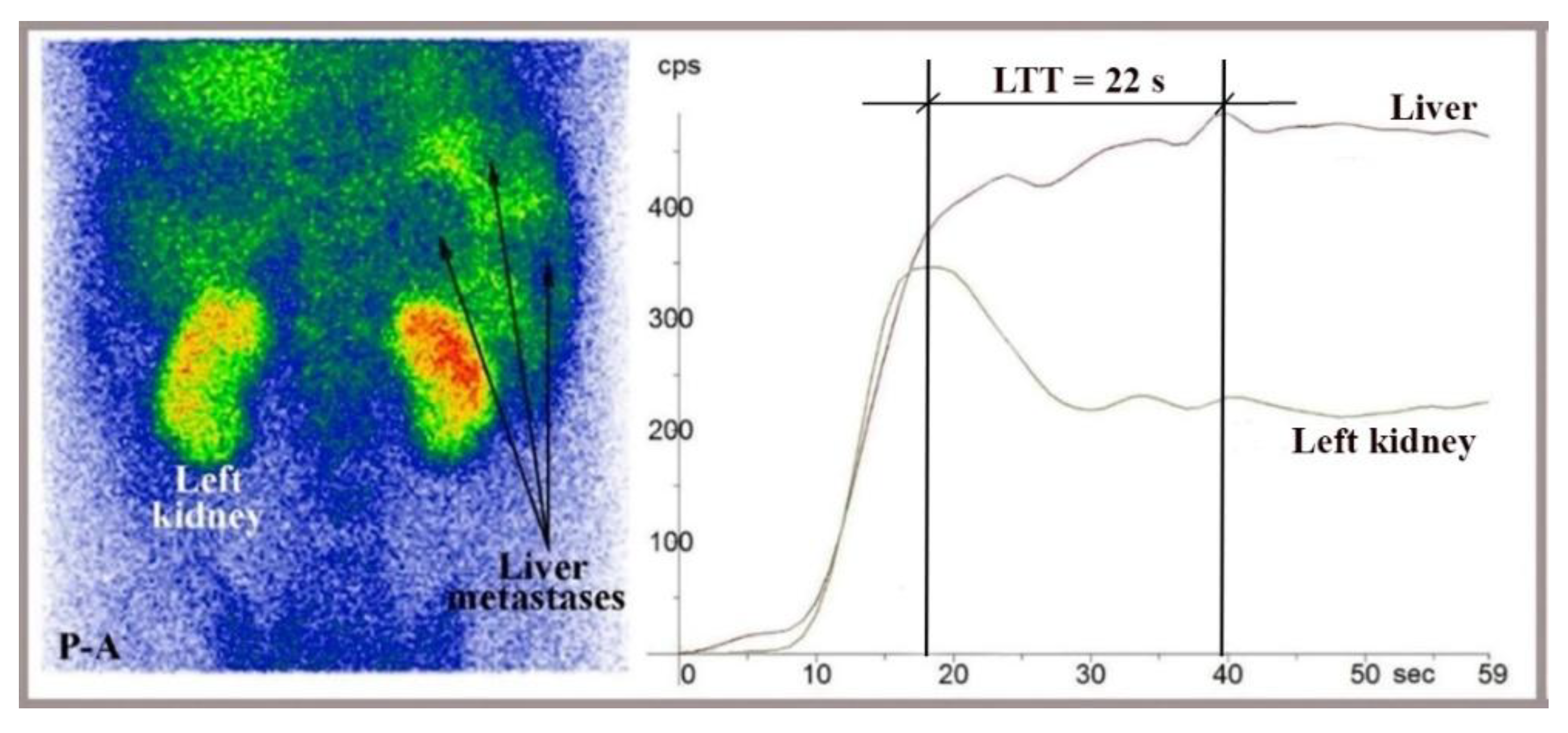

1.1. Assessment of LTT by Analyzing Time-Activity Curves Built at LAS

The time-activity curves created at LAS help us determine when the radiotracer delivered through portal inflow reaches the liver (matching the peak of the left or right kidney dynamic curve) and when the portal inflow of radiotracer then begins to leave the liver (indicated by the peak of the dynamic curve on the liver). LTT is the time between these two points (

Figure 1 and

Figure 6). We used time-activity curves based on the spleen and aorta to verify the accurate delivery of the radiotracer bolus. LTT values measured at LAS for

99mTc-HDP, delivered to the gut mucosa via arterial flow after intravenous injection, ranged from 20 to 27 seconds, aligning with the 24-second mean value recorded at PRPS for colorectal-absorbed

99mTc-pertechnetate. LTT measured at LAS remained within this range even for patients with overt liver metastases from various cancers who did not have a portosystemic shunt (

Figure 6).

1.1. Significance of the Results

No correlation was found between the TTs we evaluated and sex or age.

Table 1 summarizes the studies conducted, the main findings, and their significance.

Discussion

1.1. Activation of the First-Pass Vasoactive Response in the Liver and Lungs to Facilitate the Removal of PHCs Absorbed from the Gut

In PRPS using

99mTc-pertechnetate, the mean value determined for LTT in healthy individuals was significantly higher than those observed in TSPS [

2,

3,

12], MRI [

13], and contrast-enhanced ultrasound [

14,

15,

16,

17]. The RHLT measured at PRPS using

99mTc-pertechnetate was approximately 42 s, which is significantly higher than in LR-TMDS, LAS, and the right atrium to left ventricle transit time measured during radionuclide angiocardiography [

4] (see

Table 2).

The mean LTT of 24 s of colorectal-absorbed

99mTc-pertechnetate was approximately four times longer than the LTT of 5–6 s observed at TSPS by Gao L et al. for

99mTc-phytate injected into the spleen [

2]. Kuba J and Seidlová V provided time-activity histograms for the liver and precordium following splenic injection of

99mTc-pertechnetate during TSPS. The LTT for control subjects, as calculated from these histograms, ranged from 5 to 6 s [

3]. Syrota et al. conducted TSPS using

in vitro 99mTc-labeled RBC, administered into the spleen, and observed LTT values ranging from 8 to 12 s in patients without a portosystemic shunt [

12].

The significantly shorter TTs through the liver of

99mTc-pertechnetate, which is not absorbed from the gut, as observed in TSPS [

2,

3], and through the lungs, noted at LAS and radionuclide angiocardiography [

4], show that

99mTc-pertechnetate does not directly cause vasoconstriction in these organs, indicating that other substances are the direct triggers in PRPS. This finding suggests that

99mTc-pertechnetate binds to specific VAs during absorption through the colorectal wall, forming

99mTc-VA soluble complexes that then activate vasoconstriction in the liver and lungs. The significantly prolonged RHLT determined at PRPS indicates that the vasoactive properties of

99mTc-VA complexes remain the same during their passage through the liver.

W. Wayne Lautt stated that resistance to blood flow in the liver primarily occurs in the hepatic venules. Due to the low gradient, of approximately 6-10 mmHg, between the pressure in the portal and hepatic veins, vasoconstriction activated by VAs in the hepatic venules results in a sharp decrease in portal flow [

18]. Our study suggests that VAs released from the gut mucosa induce vasoconstriction in the hepatic venules, significantly decreasing the flow velocity through sinusoids and thereby facilitating the elimination of PHCs by Kupffer cells. The arterial inflow is only slightly affected by the increased pressure in post-sinusoidal venules activated during the passage of PHC-VA complexes, due to the high mean pressure in the hepatic artery, which is similar to that in the aorta [

19]. Other mechanisms may be activated in the hepatic sinusoids, some of which help reduce portal flow velocity [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Similarly, the VAs cause vasoconstriction in pulmonary arterioles, significantly decreasing flow through the pulmonary capillaries passed by PHC-VA complexes, thereby improving removal by the lungs' mononuclear phagocyte system [

25].

The vasoactive response occurs only in the small vessels of the liver and lungs that are crossed by 99mTc-VA complexes. In the liver, vasoconstriction can be triggered in many of the approximately 50.000 post-sinusoidal venules. The liver acts as an essential hemodynamic buffer, and a temporary reduction in blood flow can accompany a significantly decreased velocity of the radiotracer between the portal and hepatic veins. In contrast, the increase in RHLT to 42 s determined in PRPS cannot be attributed to blood flow but solely to 99mTc-pertechnetate, as such a sudden and significant decrease in transpulmonary blood flow velocity would cause shock. The 99mTc-VA complexes traverse and induce vasoconstriction in only a small percentage of the millions of pulmonary arterioles, leaving the overall blood flow velocity through the lungs unchanged.

99mTc and its derivatives are safe radiotracers that are well tolerated after intravenous administration. However, 99mTc-pertechnetate, a synthetic compound, is recognized by the body during colorectal absorption as a foreign entity and thus a PHC; consequently, the vasoactive first-pass defense response is triggered against it in the liver and lungs.

An increase in RHLT is not observed in LR-TMDS, where 99mTc-pertechnetate is not absorbed through the mucosa. This suggests that the VAs that bind to 99mTc-pertechnetate and directly activate hepatic and pulmonary anti-PHC vasoconstriction in PRPS are released from the colorectal mucosa.

The body should activate this defense response against foreign substances identified as PHCs throughout the digestive tract, where absorption occurs. The uptake of 99mTc-pertechnetate in the gastric mucosa interferes with dynamic PRPS-like studies of the stomach; therefore, alternative imaging methods are necessary to detect the presence of the anti-PHC mechanism in both the stomach and small intestine.

Various oral medications and food components can activate the anti-PHC mechanism, reducing their bioavailability by increasing elimination. Substances absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract that activate the anti-PHC response temporarily decrease blood flow velocity through the liver and selectively in the lungs. This weakens the shear forces and raises the risk of hepatic and possibly pulmonary metastases in patients with different types of cancer [

26]

, who should avoid foods or oral medications that may contain substances the body could recognize as PHCs.

PRPS and TSPS conducted with

99mTc-pertechnetate in dogs and cats showed a longer LTT in PRPS (average: 12 s in dogs and 14 s in cats) compared to TSPS (average: 7 s in dogs and 8 s in cats) [

27,

28,

29]. This suggests that PHCs absorbed through the colorectal mucosa activate a first-pass vasoactive response in the livers of other mammals, not just in humans.

We note that in our study, we could not assess the intraindividual reproducibility of the data due to strict radiation protection guidelines that prevent repeating nuclear medicine investigations at short intervals without a specific clinical reason. However, the accuracy of data interpretation is supported by the low interindividual variability of TTs. The ranges of LTT and RHLT values in PRPS were three to four times higher than those seen in other imaging studies, with the differences in TTs showing high statistical significance (P < 0.0001).

1.1. Activation of the Hepatic Vasoactive Response to PHCs Reaching the Gut Mucosa via Arterial Flow Demonstrates its Overall Role in Aiding the Removal of PHCs from the Circulating Blood

A separate analysis was performed to assess whether the vasoactive response is triggered by PHCs that reach the gut mucosa through arterial flow after intravenous administration. This evaluation was essential to determine if the activation of the anti-PHC mechanism happens during the repeated recirculation of PHCs following their absorption from the gut or if they unintentionally enter the bloodstream.

The LTT values ranged from 22 to 27 s for the radiotracer injected intravenously at LAS, matching the mean value of 24 s observed at PRPS. This supports the idea that the vasoactive response is triggered in the liver by PHCs from the portal flow, which had previously reached the digestive mucosa via arterial blood. Additionally, the similar range of LTT values at PRPS and LAS indicates a comparable strength of the vasoactive responses caused by PHCs absorbed from the gut or delivered to the gut mucosa through arterial blood. This suggests that the vasoactive mechanism we describe acts not only as a first-pass defense against PHCs absorbed from the gut but also as a broader process that helps remove substances recognized as PHCs from circulating blood.

Further research is required to determine whether the body identifies specific imaging agents as PHCs and activates vasoactive defense responses of varying intensities against them. This consideration arises from the significant variations in the mean portal vein to hepatic veins TTs observed in contrast-enhanced ultrasound following the intravenous administration of different echo-enhancers: 6.33 s for BR1 [

14], 6.45 s for Sonazoid [

15], 15.27 s for Sonovue [

16], and 9.597 s for Levovist [

17]. The strengths of the vasoactive responses and, consequently, the LTTs probably depend on the chemical properties of the substances identified as PHCs in the intestinal mucosa.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Additional research is needed to identify the VAs. Our analysis indicates that VAs can be extracted from portal blood flow after the per-rectal administration of 99mTc-pertechnetate. LR-TMDS was conducted with a small patient cohort. We were unable to perform upper rectum transmucosal dynamic scintigraphy using 99mTc-pertechnetate or per-rectal portal scintigraphy with radiopharmaceuticals other than 99mTc-pertechnetate. Further research is required to determine whether PHCs reaching the gut mucosa through arterial flow can trigger the anti-PHC response in the lungs.

Conclusions

This study revealed that a first-pass vasoactive response is triggered in the liver and lungs during PRPS to facilitate the removal of 99mTc-pertechnetate, an artificial substance that the body recognizes as PHC during colorectal absorption. VAs released from the gut mucosa likely bind to PHCs, forming soluble complexes that directly activate an intense vasoactive response in the liver and lungs, significantly slowing PHC flow. This defense response also activates in the liver against unknown substances that reach the gut mucosa through arterial flow, aiding in the removal of PHCs from circulating blood.

A similar sudden drop in portal flow occurs in the early stages of CRC liver metastasis. CRC cells originating from the mucosa usually produce VAs, which are released into portal tributaries during tumor progression. The VAs cause vasoconstriction, which reduces portal flow velocity and facilitates metastasis. Extraintestinal cancers typically do not produce VAs and, as a result, do not trigger the anti-PHC response.

This study has implications for pharmacokinetics, toxicology, and the food industry, and it may also benefit oncology, especially in the treatment of CRC. Tracking VAs in the bloodstream could aid in the early diagnosis and prompt treatment of CRC with a high metastatic risk. Using specific medications to target VAs or their receptors might inhibit or reduce liver and possibly lung metastasis, potentially extending life expectancy for CRC patients.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information can be provided by the corresponding author upon request.

Author Contributions

Dragoteanu M. coordinated the nuclear medicine procedures, conceptualized the study, examined the data collected, reviewed the literature, analyzed the laboratory database, and assessed liver and pulmonary transit times during per-rectal portal scintigraphy, identifying the slowdown in blood flow through the liver and lungs in response to potentially hazardous chemicals passing through the gut mucosa. He examined the role of this mechanism in facilitating early metastasis of colorectal cancer and oversaw the drafting and revision of the manuscript. Tolea S. prepared the manuscript for submission and checked the language as a native speaker. Duca I. compared the data with that from primary liver tumors studied using liver angioscintigraphy and participated in revising the manuscript. Mititelu R. contributed to the synthesis, literature review, and drafting of the manuscript. Kairemo K. supervised the final content and revision. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research ethics board of the ”Professor Dr. Octavian Fodor” Regional Institute for Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, has approved the nuclear medicine procedures currently conducted and their application for scientific purposes (January 29, 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

All patients and healthy volunteers provided written informed consent before participation. Confidentiality of the study participants was maintained throughout the study.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to our late professors, Gheorghe Vocilă, Sabin Cotul, Oliviu Pascu, and István Tamás, as well as to our colleagues, Cecilia-Diana Pîgleșan, Liliana Dina, Florin Graur, and Ioan-Adrian Balea.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

We used the following abbreviations in the manuscript:

| CRC |

colorectal cancer |

| DPI |

Doppler perfusion index |

| HDP |

hydroxyethylene-diphosphate |

| HPI |

hepatic perfusion index |

| LAS |

liver angioscintigraphy |

| LR-TMDS |

lower rectum transmucosal dynamic scintigraphy |

| LTT |

liver transit time, from the portal vein to the right atrium |

| MRI |

magnetic resonance imaging |

| PHC |

potentially hazardous chemical |

| PRPS |

per-rectal portal scintigraphy |

| RHLT |

right heart to the liver circulation time |

| TSPS |

trans-splenic portal scintigraphy |

| TTs |

transit times |

| VAs |

vasoactive agents |

References

- Dragoteanu, M.; Balea, I.A.; Dina, L.A.; Piglesan, C.D.; Grigorescu, I.; Tamas, S.; Cotul, S.O. Staging of portal hypertension and portosystemic shunts using dynamic nuclear medicine investigations. World J Gastroenterol. 2008, 14, 3841–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, L.; Yang F; Ren, C. ; Han, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, H. Diagnosis of cirrhotic portal hypertension and compensatory circulation using transsplenic portal scintigraphy with (99m)Tc-phytate. J Nucl Med. 2010, 51, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuba, J.; Seidlová, V. Evaluation of portal circulation by the scintillation camera. J Nucl Med. 1972, 13, 689–692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jones, R.H.; Sabiston, D.C. Jr.; Bates, B.B.; Morris, J.J.; Anderson, P.A.; Goodrich, J.K. Quantitative radionuclide angiocardiography for determination of chamber to chamber cardiac transit times. Am J Cardiol. 1972, 30, 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leen, E.; Goldberg, J.A.; Angerson, W.J.; McArdle, C.S. Potential role of Doppler perfusion index in selection of patients with colorectal cancer for adjuvant chemotherapy. Lancet. 2000, 355, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiomi, S.; Kuroki, T.; Ueda, T.; Takeda, T.; Ikeoka, N.; Nishiguchi, S.; Nakajima, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Ochi, H. Clinical usefulness of evaluation of portal circulation by per rectal portal scintigraphy with technetium- 99 m pertechnetate. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995, 90, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sheafor, D.H.; Killius, J.S.; Paulson, E.K.; DeLong, D.M.; Foti, A.M.; Nelson, R.C. Hepatic parenchymal enhancement during triple-phase helical CT: can it be used to predict which patients with breast cancer will develop hepatic metastases? Radiology. 2000, 214, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, H.W.; Gallagher, H.; Hemingway, D.M.; Angerson, W.J.; Bessent, R.G.; Wotherspoon, H.; McArdle, C.S.; Cooke, T.G. Prospective assessment of the hepatic perfusion index in patients with colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1998, 85, 1708–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leveson, S.H.; Wiggins, P.A; Nasiru, T.A.; Giles, G.R.; Robinson, P.J.; Parkin, A. Improving the detection of hepatic metastases by the use of dynamic flow scintigraphy. Br J Cancer. 1983, 47, 719–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarper, R.; Fajman, W.A.; Rypins, E.B.; Henderson, J.M.; Tarcan, Y.A.; Galambos, J.T.; Warren, W.D. A noninvasive method for measuring portal venous/total hepatic blood flow by hepatosplenic radionuclide angiography. Radiology. 1981, 141, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glover, C.; Douse, P.; Kane, P.; Karani, J.; Meire, H.; Mohammadtaghi, S.; Allen-Mersh, T.G. Accuracy of investigations for asymptomatic colorectal liver metastases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002, 45, 476–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syrota, A.; Vinot, J.M.; Paraf, A.; Roucayrol, J.C. Scintillation splenoportography: hemodynamic and morphological study of the portal circulation. Gastroenterology. 1976, 71, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohmann, J.; Newerla, C.; Müller, A.; Reinicke, C.; Skrok, J.; Frericks, B.B.; Albrecht, T. Hepatic transit time analysis using contrast enhanced MRI with Gd-BOPTA: A prospective study comparing patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer and healthy volunteers. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012, 36, 1389–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohmann, J.; Müller, C.; Oldenburg, A.; Skrok, J.; Frericks, B.B.; Wolf, K.J.; Albrecht, T. Hepatic transit time analysis using contrast-enhanced ultrasound with BR1: A prospective study comparing patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer with healthy volunteers. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2009, 35, 1427–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goto, Y.; Okuda, K.; Akasu, G.; Kinoshita, H.; Tanaka, H. Noninvasive diagnosis of compensated cirrhosis using an analysis of the time-intensity curve portal vein slope gradient on contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. Surg Today. 2014, 44, 1496–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staub, F.; Tournoux-Facon, C.; Roumy, J.; Chaigneau, C.; Morichaut-Beauchant, M.; Levillain, P.; Prevost, C.; Aubé, C.; Lebigot, J.; Oberti, F.; et al. Liver fibrosis staging with contrast-enhanced ultrasonography: prospective multicenter study compared with METAVIR scoring. Eur Radiol. 2009, 19, 1991–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.Q.; Jiang, B.; Li, H.Q.; Jin, C.X.; Wang, H. Application of the Hepatic Transit Time (HTT) in Evaluation of Portal Vein Pressure in Gastroesophageal Varices Patients. J Ultrasound Med. 2019, 38, 2305–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lautt, W.W. Hepatic Circulation: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Resistance in the Venous System. Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences, USA, 2010, 53-62. [CrossRef]

- Eipel, C.; Abshagen, K.; Vollmar, B. Regulation of hepatic blood flow: the hepatic arterial buffer response revisited. World J Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 6046–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, Z.; Madoff, D.C. Liver anatomy: microcirculation of the liver. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2008, 25, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gangopadhyay, A.; Lazure, D.A.; Thomas, P. Adhesion of colorectal carcinoma cells to the endothelium is mediated by cytokines from CEA stimulated Kupffer cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1998, 16, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shankar, A.; Loizidou, M.; Aliev, G.; Fredericks, S.; Holt, D.; Boulos, P.B.; Burnstock, G.; Taylor, I. Raised endothelin 1 levels in patients with colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 1998, 85, 502–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oda, M.; Yokomori, H.; Han, J.Y. Regulatory mechanisms of hepatic microcirculation. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2003, 29, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kuniyasu, H. Multiple roles of angiotensin in colorectal cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2012, 3, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aegerter, H.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Jakubzick, C.V. Biology of lung macrophages in health and disease. Immunity. 2022, 55, 1564–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haier, J.; Nicolson, G.L. The role of tumor cell adhesion as an important factor in formation of distant colorectal metastasis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001, 44, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, R.C.; Morandi, F.; Avenell, J.; Daniel, G.B. Trans-splenic portal scintigraphy in normal dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2005, 46, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEvoy, F.J.; Forster-van Hijfte, M.A.; White, R.N. Detection of portal blood flow using per-rectal 99mTc-pertechnetate scintigraphy in normal cats. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 1998, 39, 234–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandermeulen, E.; Combes, A.; de Rooster, H.; Polis, I.; de Spiegeleer, B.; Saunders, J.; Peremans, K. Transsplenic portal scintigraphy using 99mTc-pertechnetate for the diagnosis of portosystemic shunts in cats: a retrospective review of 12 patients. J Feline Med Surg. 2013, 15, 1123–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leen, E. The detection of occult liver metastases of colorectal carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999, 6, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, D.A.; Parkin, A.; Wiggins, P.; Robinson, P.J.; Giles, G.R. Hepatic perfusion index and the evolution of liver metastases. Nucl Med Commun. 1987, 8, 970–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopljar, M.; Patrlj, L.; Bušić, Z.; Kolovrat, M.; Rakić, M.; Kliček, R.; Zidak, M.; Stipančić, I. Potential use of Doppler perfusion index in detection of occult liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2014, 3, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nott, D.M.; Grime, S.J.; Yates, J.; Baxter, J.N.; Cooke, T.G.; Jenkins, S.A. Changes in hepatic haemodynamics in rats with overt liver tumor. Br J Cancer. 1991, 64, 1088–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, R.; Anderson, J.H.; Cooke, T.G.; Baxter, J.N.; Angerson, W.J. Splanchnic blood flow changes in the presence of hepatic tumour: evidence of a humoral mediator. Br J Cancer. 1994, 69, 1025–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemingway, D.M.; Cooke, T.G.; Grime, S.J.; Jenkins, S.A. Changes in liver blood flow associated with the growth of hepatic LV10 and MC28 sarcomas in rats. Br J Surg. 1993, 80, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nott, D.M.; Grime, S.J.; Yates, J.; Day, D.W.; Baxter, J.N.; Jenkins, S.A.; Cooke, T.G. Changes in the hepatic perfusion index during the growth and development of experimental hepatic micrometastases. Nucl Med Commun. 1987, 8, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leveson, S.H.; Wiggins, P.A.; Giles, G.R.; Parkin, A.; Robinson, P.J. Deranged liver blood flow patterns in the detection of liver metastases. Br J Surg. 1985, 72, 128–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leen, E.; Goldberg, J.A.; Robertson, J.; Sutherland, G.R.; McArdle, C.S. The use of duplex sonography in the detection of colorectal hepatic metastases. Br J Cancer. 1991, 63, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huguier, M.; Maheswari, S.; Toussaint, P.; Houry, S.; Mauban, S.; Mensch, B. Hepatic flow scintigraphy in evaluation of hepatic metastases in patients with gastrointestinal malignancy. Arch Surg. 1993, 128, 1057–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarper, R.; Fajman, W.A.; Tarcan, Y.A.; Nixon, D.W. Enhanced detection of metastatic liver disease by computerized flow scintigrams: concise communication. J Nucl Med. 1981, 22, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dragoteanu, M.; Cotul, S.O.; Pîgleşan, C.; Tamaş, S. Liver angioscintigraphy: clinical applications. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2004, 13, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bertocchi, A.; Carloni, S.; Ravenda, P.S.; Bertalot, G.; Spadoni, I.; Lo Cascio, A.; Gandini, S.; Lizier, M.; Braga, D.; Asnicar, F.; et al. Gut vascular barrier impairment leads to intestinal bacteria dissemination and colorectal cancer metastasis to liver. Cancer Cell. 2021, 39, 708–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruskal, J.B.; Thomas, P.; Kane, R.A.; Goldberg, S.N. Hepatic perfusion changes in mice livers with developing colorectal cancer metastases. Radiology 2004, 231, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuenod, C.; Leconte, I.; Siauve, N.; Resten, A.; Dromain, C.; Poulet, B.; Frouin, F.; Clément, O.; Frija, G. Early changes in liver perfusion caused by occult metastases in rats: detection with quantitative CT. Radiology. 2001, 218, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kow, A.W.C. Hepatic metastasis from colorectal cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2019, 10, 1274–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarmenitis, S.D.; Kalogeropoulou, C.P.; Hatjikondi, O.; Ravazoula, P.; Petsas, T.; Siamblis, D.; Kalfarentzos, F. An experimental approach of the Doppler perfusion index of the liver in detecting occult hepatic metastases: histological findings related to the hemodynamic measurements in Wistar rats. Eur Radiol. 2000, 10, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopljar, M.; Brkljacic, B.; Doko, M.; Horzic, M. Nature of Doppler perfusion index changes in patients with colorectal cancer liver metastases. J Ultrasound Med. 2004, 23, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oppo, K.; Leen, E.; Angerson, W.J.; McArdle, C.S. The effect of resecting the primary tumour on the Doppler Perfusion Index in patients with colorectal cancer. Clin Radiol. 2000, 55, 791–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leen, E.; Anderson, J.R.; Robertson, J.; O'Gorman, P.; Cooke, T.G.; McArdle, C.S. Doppler index perfusion in the detection of hepatic metastases secondary to gastric carcinoma. Am J Surg. 1997, 173, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishiro, T.; Shuto, K.; Hayano, K.; Satoh, A.; Kono, T.; Ohira, G.; Tohma, T.; Gunji, H.; Narushima, K.; Tochigi, T.; et al. Preoperative hepatic CT perfusion as an early predictor for the recurrence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: initial clinical results. Oncol Rep. 2014, 31, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Liver angioscintigraphy performed using 99mTc-HDP in a healthy patient. (A) Summed image. (B) Control of bolus quality on the dynamic curve built on the aorta. (C) The determined LTT was 23 s. (D) Dynamic comparative curve built on the spleen. The hepatic perfusion index was within the normal range (HPI = 30%). The study was conducted using an AnyScanS gamma camera (Mediso, Budapest, Hungary) in the posteroanterior (P-A) view.

Figure 1.

Liver angioscintigraphy performed using 99mTc-HDP in a healthy patient. (A) Summed image. (B) Control of bolus quality on the dynamic curve built on the aorta. (C) The determined LTT was 23 s. (D) Dynamic comparative curve built on the spleen. The hepatic perfusion index was within the normal range (HPI = 30%). The study was conducted using an AnyScanS gamma camera (Mediso, Budapest, Hungary) in the posteroanterior (P-A) view.

Figure 2.

The vascular pathways of 99mTc-pertechnetate during our investigations: absorbed in PRPS in patients with complete portal vein obstruction (green) and healthy volunteers (yellow), as well as after LR-TMDS administration into the submucosa of the lower rectum (red). The RHLT for 99mTc-pertechnetate was 41-43 s in cases of portal vein obstructions explored at PRPS and only 12-15 s at LR-TMDS. For 99mTc-pertechnetate delivered to the liver via the portal vein, following colorectal absorption in healthy volunteers at PRPS, the mean LTT was 24 s, and the mean RHLT was 42 s.

Figure 2.

The vascular pathways of 99mTc-pertechnetate during our investigations: absorbed in PRPS in patients with complete portal vein obstruction (green) and healthy volunteers (yellow), as well as after LR-TMDS administration into the submucosa of the lower rectum (red). The RHLT for 99mTc-pertechnetate was 41-43 s in cases of portal vein obstructions explored at PRPS and only 12-15 s at LR-TMDS. For 99mTc-pertechnetate delivered to the liver via the portal vein, following colorectal absorption in healthy volunteers at PRPS, the mean LTT was 24 s, and the mean RHLT was 42 s.

Figure 3.

Summed image and time-activity curves generated for the liver and heart regions during per-rectal portal scintigraphy using 99mTc-pertechnetate in a healthy volunteer. The liver transit time from the portal vein to the right atrium (LTT) was 24 s. The study was performed using an Orbiter SPECT gamma camera (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) in an anteroposterior (A-P) view.

Figure 3.

Summed image and time-activity curves generated for the liver and heart regions during per-rectal portal scintigraphy using 99mTc-pertechnetate in a healthy volunteer. The liver transit time from the portal vein to the right atrium (LTT) was 24 s. The study was performed using an Orbiter SPECT gamma camera (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) in an anteroposterior (A-P) view.

Figure 4.

Summed image and time-activity curves generated in per-rectal portal scintigraphy performed with 99mTc-pertechnetate in a patient with alcoholic cirrhosis and complete occlusion of the right portal vein branch. The right heart-to-liver circulation time (RHLT) determined for the right liver, which completely lacked portal inflow, was 42 s. This study used a Siemens Orbiter SPECT gamma camera in an anteroposterior (A-P) view.

Figure 4.

Summed image and time-activity curves generated in per-rectal portal scintigraphy performed with 99mTc-pertechnetate in a patient with alcoholic cirrhosis and complete occlusion of the right portal vein branch. The right heart-to-liver circulation time (RHLT) determined for the right liver, which completely lacked portal inflow, was 42 s. This study used a Siemens Orbiter SPECT gamma camera in an anteroposterior (A-P) view.

Figure 5.

Summed image and time-activity curves generated for the left kidney and right heart during lower rectum transmucosal dynamic scintigraphy (LR-TMDS) following the administration of 99mTc-pertechnetate into the submucosa of the lower rectum. The right heart-to-liver circulation time (RHLT) was 15 s. We used the dynamic curve of the left kidney because the radiotracer reaches the liver and kidneys simultaneously, but the liver curve’s onset is less clear. The study was performed using a Mediso AmyScanS gamma camera in a posteroanterior (P-A) view.

Figure 5.

Summed image and time-activity curves generated for the left kidney and right heart during lower rectum transmucosal dynamic scintigraphy (LR-TMDS) following the administration of 99mTc-pertechnetate into the submucosa of the lower rectum. The right heart-to-liver circulation time (RHLT) was 15 s. We used the dynamic curve of the left kidney because the radiotracer reaches the liver and kidneys simultaneously, but the liver curve’s onset is less clear. The study was performed using a Mediso AmyScanS gamma camera in a posteroanterior (P-A) view.

Figure 6.

Liver angioscintigraphy performed with 99mTc-HDP on a 44-year-old patient showing overt liver metastases from CRC, visible on the summed image. LTT calculated from the dynamic curves was 22 seconds. The hepatic perfusion index was markedly increased at 87.5%. This study was carried out using a Mediso AmyScanS gamma camera with a posteroanterior (P-A) view.

Figure 6.

Liver angioscintigraphy performed with 99mTc-HDP on a 44-year-old patient showing overt liver metastases from CRC, visible on the summed image. LTT calculated from the dynamic curves was 22 seconds. The hepatic perfusion index was markedly increased at 87.5%. This study was carried out using a Mediso AmyScanS gamma camera with a posteroanterior (P-A) view.

Table 1.

Significance of the results of the dynamic nuclear medicine investigations conducted in the study. PRPS: per-rectal portal scintigraphy; LTT: liver transit time, from the portal vein to the right atrium; RHLT: the right heart to liver circulation time; LAS: liver angioscintigraphy; PHC: potentially hazardous chemical; LR-TMDS: lower rectum transmucosal dynamic scintigraphy; HDP: hydroxyethylene diphosphate.

Table 1.

Significance of the results of the dynamic nuclear medicine investigations conducted in the study. PRPS: per-rectal portal scintigraphy; LTT: liver transit time, from the portal vein to the right atrium; RHLT: the right heart to liver circulation time; LAS: liver angioscintigraphy; PHC: potentially hazardous chemical; LR-TMDS: lower rectum transmucosal dynamic scintigraphy; HDP: hydroxyethylene diphosphate.

| Sr. No. |

Imaging method |

The transit time value determined |

Significance of the results |

| 1. |

PRPS with 99mTc-pertechnetate (performed in a previous study) |

Highly increased LTT (mean: 24 s) and RHLT (mean: 42 s) |

First-pass vasoconstriction is triggered in the liver and lungs in response to colorectal-absorbed 99mTc-pertechnetate,

recognized by the body as a PHC. |

| 2. |

LAS conducted to evaluate RHLT for intravenously injected 99mTc-HDP |

Low value of RHLT

(9.5-13.5 s) |

99mTc-HDP, when administered intravenously, cannot directly trigger first-pass vasoconstriction in the lungs. |

| 3. |

LAS conducted to evaluate RHLT for intravenously injected 99mTc-pertechnetate |

Low value of RHLT

(9-13 s) |

99mTc-pertechnetate, when injected intravenously, cannot directly trigger first-pass vasoconstriction in the lungs. |

| 4. |

LR-TMDS conducted to evaluate RHLT for 99mTc-pertechnetate administered in the lower rectum submucosa |

Low value of RHLT (12-15 s) |

Even if 99mTc-pertechnetate crosses the other layers of the colorectal wall but is not absorbed through the mucosa, it cannot directly activate first-pass vasoconstriction in the lungs. This indicates that the vasoactive agents that trigger vasoconstriction in PRPS are secreted in the colorectal mucosa. |

| 5. |

LAS conducted to evaluate LTT for intravenously injected 99mTc-HDP |

Highly increased LTT (20-27 s) |

Vasoconstriction is activated in the liver in response to 99mTc-HDP, which is delivered to the gut mucosa through arterial flow after intravenous injection. |

Table 2.

Mean values of LTT, right atrium to left ventricle transit time, and RHLT were measured in healthy controls using various imaging methods. LTT: liver transit time, from the portal vein to the right atrium; RHLT: the right heart to liver circulation time; PRPS: per-rectal portal scintigraphy; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PHC: potentially hazardous chemical; TSPS: trans-splenic portal scintigraphy; LAS: liver angioscintigraphy; LR-TMDS: lower rectum transmucosal dynamic scintigraphy.

Table 2.

Mean values of LTT, right atrium to left ventricle transit time, and RHLT were measured in healthy controls using various imaging methods. LTT: liver transit time, from the portal vein to the right atrium; RHLT: the right heart to liver circulation time; PRPS: per-rectal portal scintigraphy; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PHC: potentially hazardous chemical; TSPS: trans-splenic portal scintigraphy; LAS: liver angioscintigraphy; LR-TMDS: lower rectum transmucosal dynamic scintigraphy.

| Sr. No. |

Imaging method |

LTT |

The transit time between the right atrium and the left ventricle |

RHLT |

| 1. |

PRPS with 99mTc-pertechnetate [1] |

24 s |

|

42 s |

| 2. |

TSPS with 99mTc-phytate or 99mTc-pertechnetate [2,3] |

5-6 s |

|

- |

| 3. |

TSPS with RBC labelled in vitro with 99mTc [12] |

8-12 s |

|

- |

| 4. |

Radionuclide angiocardiography with 99mTc-pertechnetate [4] |

- |

9.2 s ± 1.2 s |

- |

| 5. |

MRI with Gd-BOPTA [13] |

3.03 s |

|

- |

| 6. |

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound utilizing different echo-enhancers [14,15,16,17] |

6.33 s (BR1)

6.45 s (Sonazoid)

15.27 s (Sonovue)

9.597 s (Levovist) |

|

- |

| 7. |

LAS with 99mTc-HDP

(present study data) |

20-27 s |

|

9.5-13.5 s |

| 8. |

LAS with 99mTc-pertechnetate

(present study data) |

- |

|

9-13 s |

| 9. |

LR-TMDS with 99mTc-pertechnetate

(present study data) |

- |

|

12-15 s |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).