Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, approximately 6.3 billion people worldwide utilize traditional medicine as part of their healthcare [

1]. Traditional medicine refers to the long-established cultural practices that employ plant-based remedies to support health and treat disease. An underlying principle in many traditional systems is the use of synergistic herbal blends, in which the therapeutic effects of individual plants are thought to be enhanced when combined [

2]. Despite their historical and widespread use, the efficacy of such remedies remains under-researched within the framework of modern biomedical science. Individuals may turn to traditional medicine due to dissatisfaction with conventional care, positive past experiences, or family traditions [

3]. While certain compounds derived from individual herbs have been studied, the full therapeutic potential of complex herbal combinations remains underexplored [

4].

One such blend is So-Cheong-Ryong-Tang (SCRT), a traditional Korean medicine composed of multiple plant extracts. Among its key ingredients are ginger root (Zingiber officinale) and licorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabra), both of which have demonstrated antimicrobial properties in prior in-vitro studies. Licorice root contains glycyrrhizin, a triterpenoid saponin that compromises bacterial plasma membrane integrity and interferes with enzymatic activity. Ginger root contains gingerol, shogaol, and zingerone, bioactive compounds that have been reported to disrupt bacterial membranes and inhibit binary fissions.

The motivation for this study lies in the growing concern over antimicrobial resistance (AMR), which has been exacerbated by the excessive use of antibiotics in both medical and agricultural contexts. In the United States alone, antibiotics have extended life expectancy by 5–10 years and saved over 200,000 lives annually [

5]. However, global misuse of antibiotics in healthcare and farming has accelerated the rise of resistant strains. In 2019, antimicrobial resistance was implicated in nearly five million deaths worldwide [

6,

7]. This alarming trend underscores the urgency of identifying alternative antimicrobial agents, especially those derived from natural sources. Penicillin, one of the first antibiotics discovered, originated from a natural compound produced by

Penicillium fungi, illustrating nature's potential to yield potent antimicrobial agents.

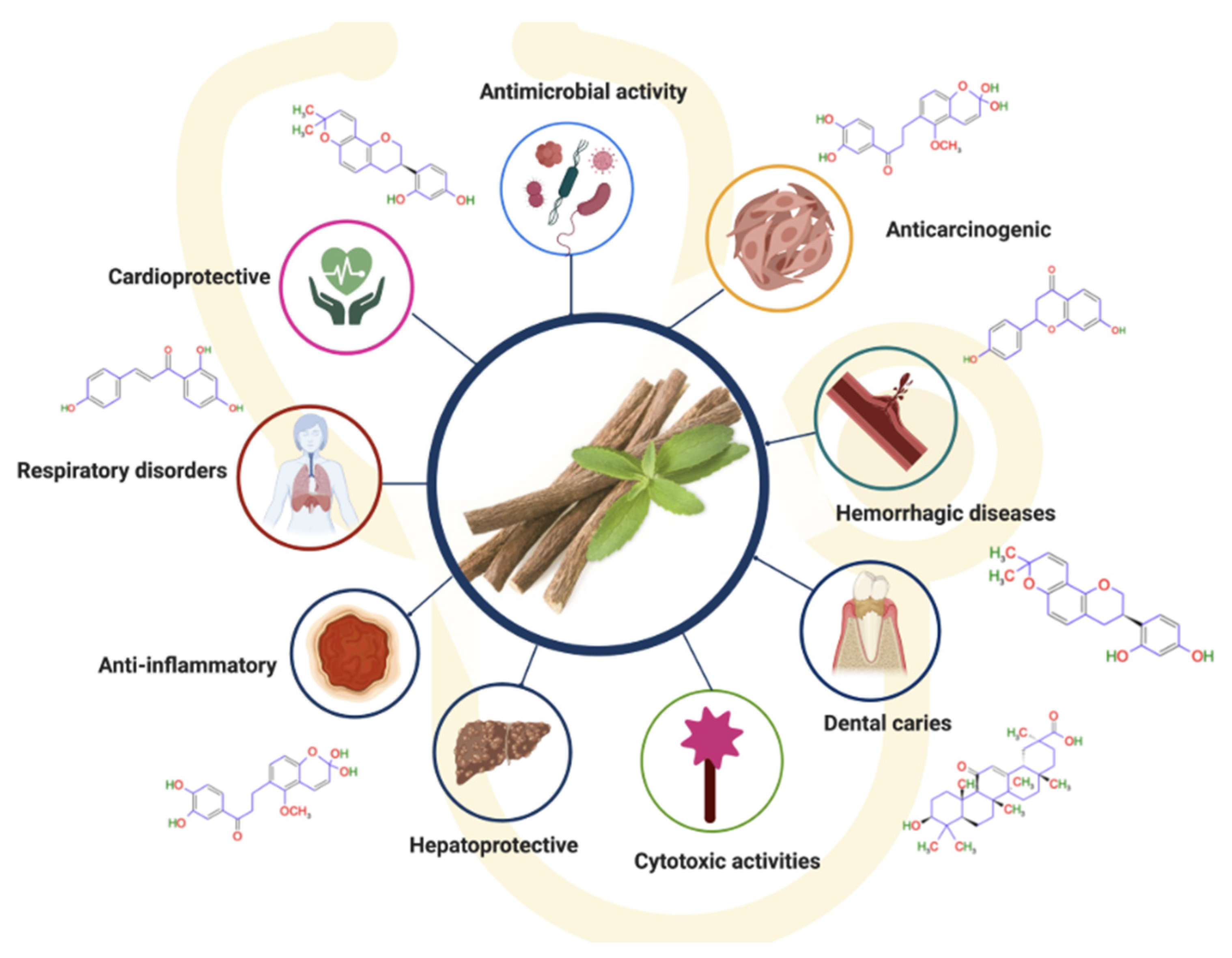

Licorice root contains numerous bioactive compounds, including flavonoids, saponins, and phenolic acids, which contribute to its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties (

Figure 1) [

8].

This study aims to compare the antimicrobial properties of ginger root and licorice root individually and in combination. By examining a simplified version of SCRT that includes only these two components, this research explores whether their combined effects result in enhanced inhibition of Escherichia coli growth. In doing so, the study contributes to the broader understanding of synergistic plant interactions and their potential application in combating AMR.

Methods

Solvent Preparation

A serial dilution of ethanol was prepared using distilled water as the diluent. The initial stock solution was created by mixing 10 mL of 95% ethanol with 90 mL of distilled water to produce a 10% ethanol solution. Subsequently, 10 mL of the 10% solution was combined with 90 mL of distilled water to yield a 1% solution. A final dilution was performed by mixing 10 mL of the 1% solution with 90 mL of distilled water, resulting in a 0.1% ethanol solution.

Agar Plate Preparation and Inoculation

Pre-prepared LB agar liquid medium was purchased and poured into sterile, empty Petri dishes. Approximately 20 mL of the liquid medium was dispensed into each dish under aseptic conditions and allowed to solidify at room temperature for one day prior to inoculation. Once solidified, Escherichia coli cultures were applied using sterilised cotton swabs dipped into the bacterial suspension. Excess liquid was removed by touching the swabs to the inner wall of the tube. The bacteria were evenly streaked across the surface of each agar plate.

Each plate was labelled on the bottom to indicate the treatment: distilled water (negative control), ethanol (solvent control), licorice root extract, ginger root extract, and SCRT (combination extract). A grid with four quadrants was drawn on the back of each plate to guide disc placement.

Sterile paper discs were placed on the agar using forceps and treated with 0.05 mL of the corresponding extract. The plates were left at room temperature for 18–24 hours to allow for diffusion and microbial inhibition. This process was replicated across three independent trials to ensure consistency and reproducibility.

Results

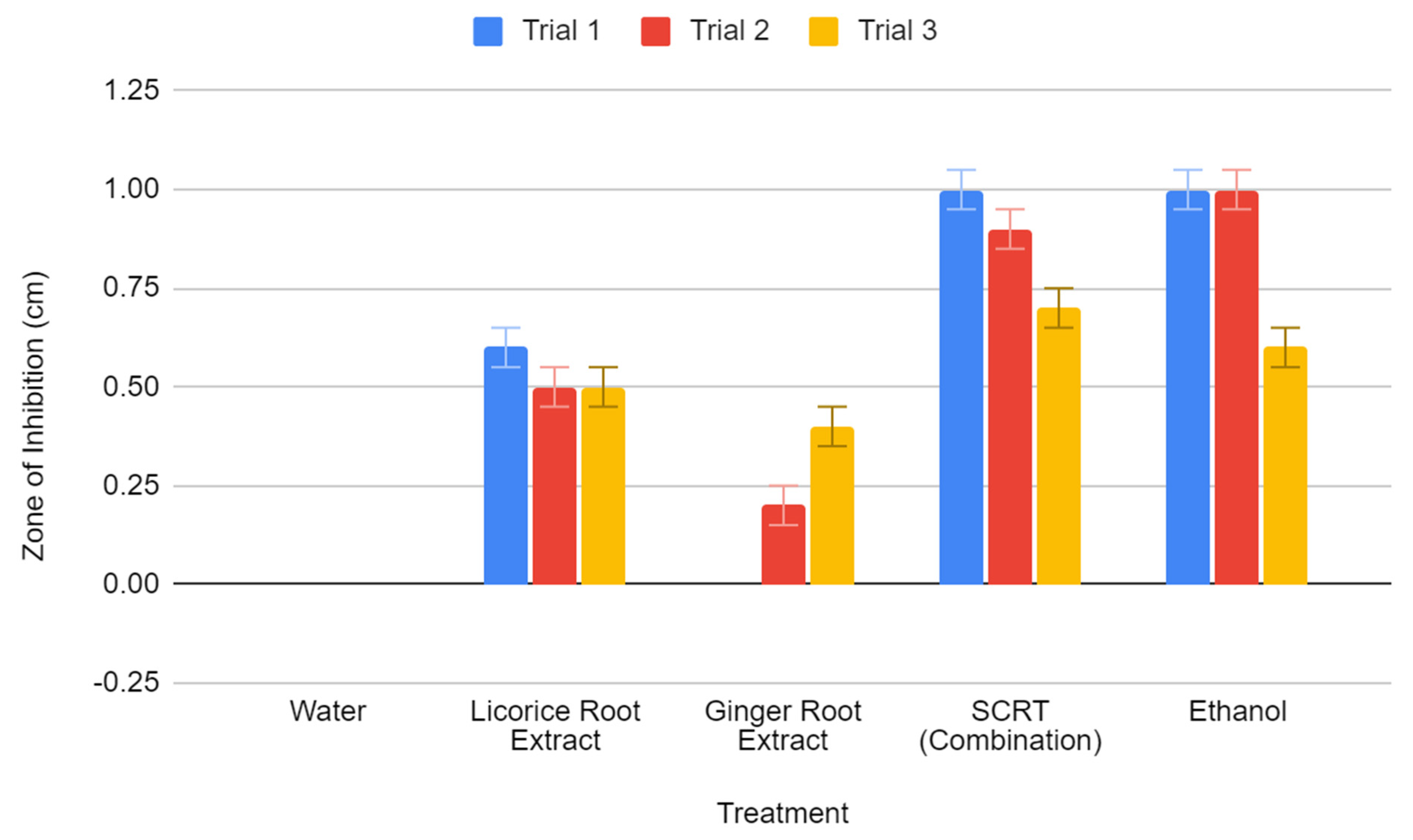

The antimicrobial activity of each treatment was assessed by measuring the diameter of the zones of inhibition formed around the discs after 18–24 hours of incubation.

Table 1 presents the inhibition zone measurements from all three trials, including the mean values.

The distilled water (negative control) showed no antimicrobial activity. Ginger and licorice root extracts both inhibited E. coli growth, with licorice showing a greater effect. Notably, the combination of ginger and licorice in SCRT produced the largest average inhibition zone, suggesting a synergistic interaction between the two extracts. However, the ethanol control also exhibited a comparable average inhibition zone, indicating a need to further isolate the effect of the herbal components from that of the solvent.

Figure 2.

Bar graph showing average zones of inhibition (± 0.05 cm) for each treatment group.

Figure 2.

Bar graph showing average zones of inhibition (± 0.05 cm) for each treatment group.

Figure 3.

Trial-wise comparison of inhibition zone diameters for all treatments, shown via grouped bar chart.

Figure 3.

Trial-wise comparison of inhibition zone diameters for all treatments, shown via grouped bar chart.

Discussion

The findings of this study confirm that both ginger root and licorice root possess antimicrobial properties against

Escherichia coli, with licorice root showing greater inhibitory effect than ginger when used individually. The most notable outcome, however, was observed in the SCRT combination, which demonstrated enhanced antimicrobial activity, suggesting a synergistic effect between the two plant extracts. This aligns with previous research indicating that combined phytochemicals can exhibit greater bioactivity than their isolated counterparts [

9].

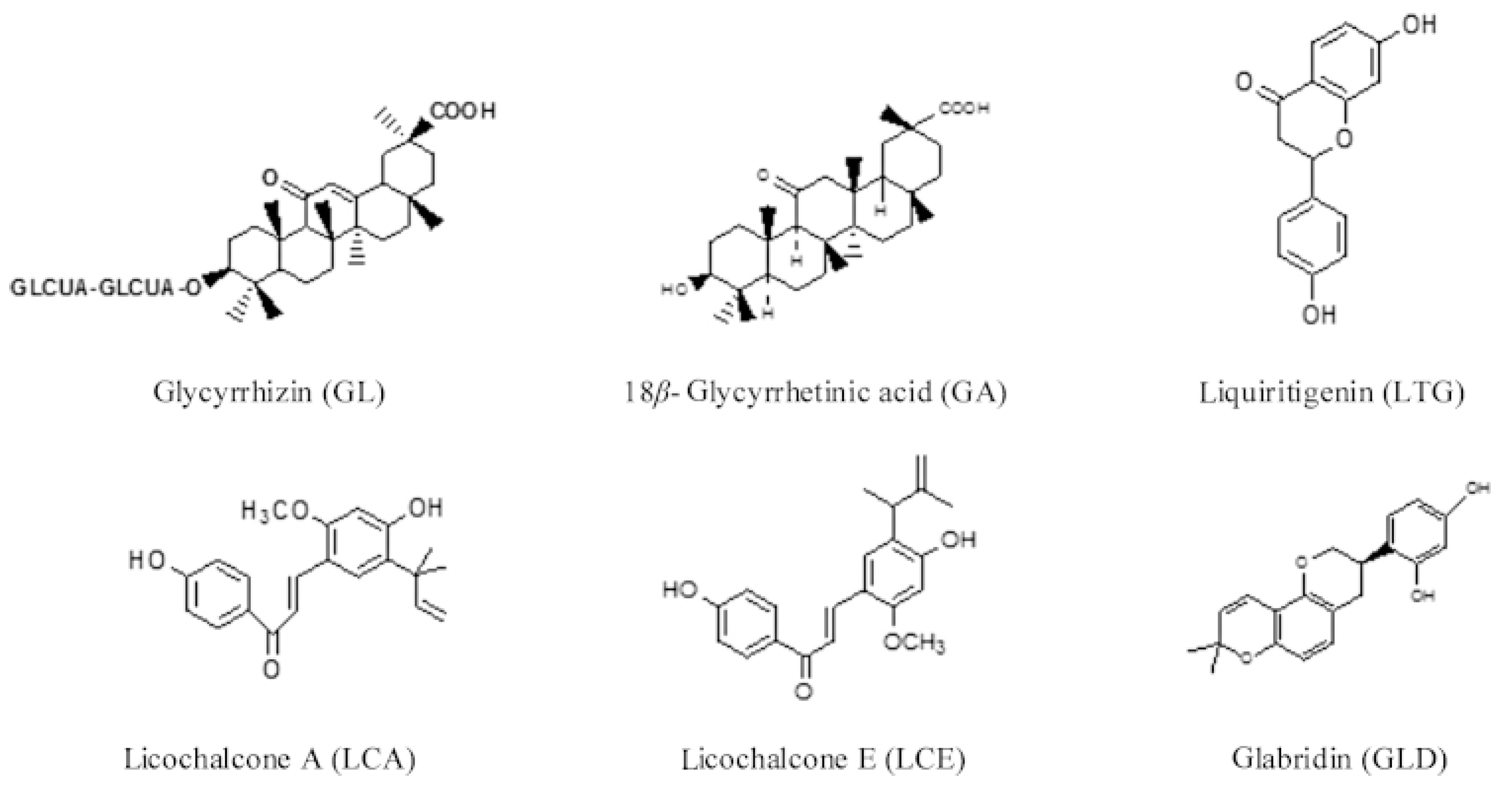

The observed synergy is likely attributed to the interaction of bioactive compounds such as glycyrrhizin (from licorice) and gingerol (from ginger), which disrupt bacterial membranes and inhibit enzyme function. These compounds may act on different microbial targets or reinforce each other’s mechanisms of action. This is illustrated in

Figure 4, which shows key antimicrobial compounds present in ginger and licorice root. Previous studies have also shown that combinations of plant-derived antimicrobials can increase membrane permeability and promote reactive oxygen species generation, ultimately leading to bacterial cell death [

10].

While the combination treatment outperformed the individual extracts, it is important to note that the ethanol control also produced a similar average zone of inhibition. This raises concerns regarding the extent to which ethanol contributed to the observed antimicrobial activity in the SCRT solution. Although the ethanol was diluted to 0.1%, its presence could still influence bacterial growth inhibition. To isolate the true effect of the herbal compounds, future experiments should explore the use of alternative solvents or include additional controls with varying ethanol concentrations.

Moreover, the study's limitation lies in its narrow bacterial focus. Since only E. coli, a gram-negative bacterium, was tested, the results cannot be generalized to gram-positive bacteria or other pathogens. Gram-positive bacteria possess different cell wall structures, and their susceptibility to antimicrobial agents may vary. Future studies should include a broader panel of bacterial strains to better evaluate the spectrum and consistency of the extracts’ antimicrobial effects.

Another consideration is the in vitro nature of the experiment. Laboratory conditions do not replicate the complexity of living organisms, where factors such as metabolism, immune response, and compound bioavailability play significant roles. Thus, further investigation in vivo or through more sophisticated models would be required to validate the practical therapeutic potential of ginger and licorice root extracts.

In summary, the results provide promising evidence for the antimicrobial synergy of ginger and licorice root extracts, supporting their potential as alternative treatments in the context of rising antibiotic resistance. However, more comprehensive studies are required to confirm these findings and address confounding factors such as solvent influence and biological variability.

Conclusion

This study explored the antimicrobial potential of ginger and licorice root extracts against Escherichia coli, both as individual treatments and in combination. The results revealed that while each extract exhibited measurable antimicrobial activity, the combined SCRT formulation produced a significantly enhanced effect. This suggests that synergistic interactions between the phytochemicals in ginger and licorice can amplify their antimicrobial efficacy.

These findings reinforce the potential value of natural compounds as alternatives or complements to conventional antibiotics, particularly in the face of increasing antibiotic resistance. However, the antimicrobial activity observed in the ethanol control group underscores the importance of further investigations using alternative solvents to isolate the true contributions of plant-based compounds.

Future investigations should expand the scope by including multiple different bacterial species, testing various extract concentrations, and conducting in vivo analyses. Such extensions will be essential for validating the clinical relevance and therapeutic applications of herbal combinations like SCRT. With proper validation, these traditional formulations may one day provide accessible and effective antimicrobial solutions in both clinical and community settings.

References

- World Health Organization. Who traditional medicine strategy 2014–2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506090 (2014).

- H. Yuan, Q. Ma, G. Ye, & G. Ni. The traditional medicine and modern medicine from natural products. Molecules, 21(5), 559 (2016).

- A. N. Welz, A. Emberger-Klein, & K. Menrad. Why people use herbal medicine: Insights from a focus-group study in Germany. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 18(1), 92 (2018).

- M. Leonti. The co-evolutionary perspective of the ethnopharmacology of traditional medicines. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 154(3), 873–886 (2014).

- R. Gottfried. The Antibiotic Era: Reform, Resistance, and the Pursuit of a Rational Therapeutics. New York: Columbia University Press (2005).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/pdf/threats-report/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf (2019).

- M. A. Salam, M. M. Khan, S. J. Islam, M. M. Jahan, & A. H. M. Nurun Nabi. Antimicrobial resistance: A growing serious threat for global public health. Healthcare, 11(7), 1002 (2023).

- S. Wahab, S. Ahmad, M. Khan, M. A. Siddiqui, & A. M. Alajmi. Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice): A comprehensive review on its phytochemistry, biological activities, clinical evidence and toxicology. Plants, 10(12), 2751 (2021).

- N. Vaou, D. Stavropoulou, M. Voidarou, E. Tsakris, & G. Rozos. Interactions between medical plant-derived bioactive compounds: Focus on antimicrobial combination effects. Antibiotics, 11(8), 1047 (2022).

- Q.-Q. Mao, J.-Q. Xu, H. Cao, C.-Y. Wang, Y.-L. Zheng, & S.-M. Chen. Bioactive compounds and bioactivities of ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods, 8(6), 185 (2019).

- J. Wang, W. Zhang, Y. Zhang, J. Yang, Y. Wang, & H. Wu. Ginger and licorice: A review of their bioactive compounds and pharmacological effects. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine, 5, 1–6 (2015).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).