1. Introduction

Globally, periodontal diseases pose a serious threat to public health because they affect a huge number of people worldwide and, if ignored, could result in tooth loss. One of the common oral bacteria present in the oral plaque of the patients with periodontitis (Schmidt et al.,2014) and known to be actively involved in the progression of gingivitis, is the Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria Porphyromonas gingivalis (

P. ginivalis) [

1]. On both soft and hard oral tissues, it is known to develop biofilms, an organised community of bacterial cells encased in a self-produced polymeric matrix [

2]. These biofilms [

3] are a characteristic of chronic periodontitis and provide resistance to host defense and common antimicrobial therapies, helping to enhance the pathogenicity of

P. gingivalis [

4]. A major concern to world health is antibiotic resistance, which has rendered many common antibiotics ineffective.

The search for new antimicrobial drugs, particularly those derived from natural resources, has been sparked by this dilemma [

5]. Due to their shown effectiveness against a variety of bacterial infections, chemicals originating from plants have attracted enormous attention in this context [

6,

7]. Comfrey, also known as Symphytum Officinale, and Panax Ginseng are two such promising herbs that have demonstrated exceptional antibacterial qualities in prior tests [

1]. Furthermore, it is thought that the quorum sensing (QS) phenomenon in bacteria, a cell to cell communication activity, is crucial for biofilm formation and other virulence characteristics [

8]. Acylated Homoserine Lactones (AHLs), signaling molecules found in many gram-negative bacteria, including

P. gingivalis, are crucial for QS [

9]. Therefore, preventing the synthesis of these molecules may be able to reduce bacterial pathogenicity and prevent the development of biofilms, making it a viable technique for treating chronic infections like periodontitis [

5].

Allantoin, rosmarinic acid, and mucilage are just a few of the many bioactive substances found in Symphytum Officinale, a plant that has long been used to cure a variety of diseases. The anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and wound healing abilities of these substances have been studied in the past. An aphrodisiac, adaptogen, and all-purpose cure-all, Panax ginseng is a well-known medicinal herb with East Asian origins [

2]. The primary active ingredients in Panax ginseng are saponins called ginsenosides, which have strong antibacterial and anti-inflammatory activities [

10,

11]. The investigation of these natural substances for their capacity to thwart quorum sensing and biofilm formation processes may eventually result in the development of novel approaches for the periodontal disease therapy [

9].

One of the main therapies for anaerobic bacterial infections, including those brought on by

P. gingivalis, is the nitroimidazole antibiotic metronidazole. It causes harm to DNA and prevents bacteria from making proteins. The advent of antibiotic resistance and its associated negative consequences, however, have called into doubt its exclusive usage. Metronidazole may be more effective when combined with natural plant extracts, which would lower the dosage needed and the risk of adverse effects on human health [

12]. Despite Symphytum Officinale and Panax Ginseng having well-known antibacterial capabilities, nothing is known about how these two substances interact with

P. gingivalis, specifically how they affect biofilm inhibition and AHL generation. Furthermore, few research have examined the possible synergistic effects of using these extracts in conjunction with common antibiotics like metronidazole though most of the investigations have concentrated on individual plant extracts [

13,

14,

15]. By examining the effects of Symphytum Officinale and Panax Ginseng on

P. gingivalis, both separately and in combination with metronidazole, this study seeks to close this information gap. This study might make a substantial contribution to the creation of periodontal disease treatment plans [

16,

17].

A standard strain of

P. gingivalis and a clinical isolate are utilized in this work in an effort to identify the extent of effectiveness of the proposed treatment [

18]. In light of this, the current study sought to assess the antibacterial effectiveness of Panax ginseng and Symphytum Officinale extracts against

P. gingivalis. The experiment was then expanded to look at how these extracts affected the growth of AHL and

P. gingivalis biofilm when combined with metronidazole, a medication frequently used to treat periodontitis. The effects on a common strain of

P. gingivalis and a patient-derived clinical isolate were compared, providing information on the possible therapeutic uses of these plant extracts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

The main bacterial strain used in this investigation was the well-known laboratory strain P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 (American Type Culture Collection). Additionally, a clinical isolate of P. gingivalis was included to the study to assess the application of the research findings. The plaque samples were collected from periodontitis patients. The injection of Gracey-curette enabled the collection of subgingival plaque specimens. When the curette touched the bottom of the periodontal pocket without damaging the soft tissues, it collected a subgingival plaque. Following that, the plaque sample was immersed in sodium thioglycolate.

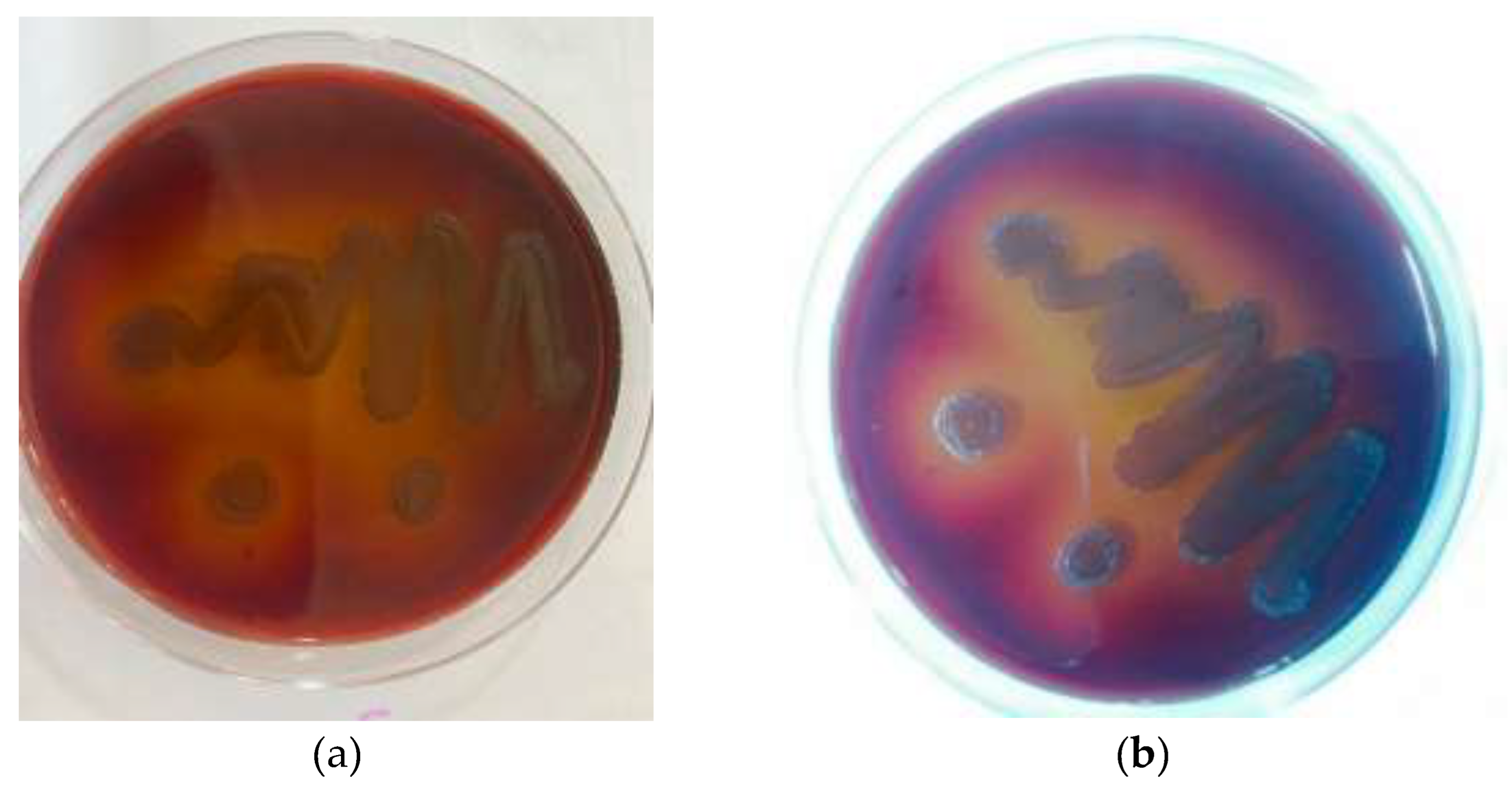

Both the standard strain and clinical isolate of

P. gingivalis were grown anaerobically in brain heart infusion (BHI) [

19] broth that had been treated with hemin and vitamin K while maintaining a 37°C temperature (

Figure 1).

2.2. Plant Extracts and Antibiotic Working Concentrations

Both Panax ginseng and Symphytum Officinale (comfrey) were purchased from reputable vendors (Rejuvica Health, USA). A suitable solvent liquid herbal extract contains no alcohol, no addative materials [

20]. Aqueous extracts of Panax ginseng and comfrey were sterilized using millipore disposable filters (0.22 µm). The selected antibiotic, metronidazole, was purchased from a local pharmacy. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was used to dissolve all substances in order to create workable concentrations. Experimental extracts include each of Symphytum Officinale and Metronidazole (S + F), followed by Symphytum Officinale alone, then the Panax Ginsengand and Metronidazole (G+ F), then the Panax Ginseng(G) alone, and finally the Metronidazole (F) alone. Working concentrations for Metronidazole, Panax Ginseng, and Symphytum Officinale were produced both alone and in combination. To enable a thorough investigation of each chemical's effects throughout a variety of doses, six dilutions (D1 to D6) were generated for each compound using a systematic two-fold serial dilution technique as shown in

Table 1.

2.3. Biofilm Inhibition Assay

P. gingivalis was grown in a brain-heart infusion medium containing 10% blood and 0.2 mg/mL vitamin K. (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Bacteria thrived in an anaerobic chamber with 5% H

2, 10% CO

2, and 85% N

2 at 37°C for 48 to 72 hours [

21].

Using a microtiter plate biofilm test, the potential of plant extracts and Metronidazole to prevent

P. gingivalis from forming biofilms was evaluated. Both the standard strain and isolate were exposed to various test drug doses. The microplates were then incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 24 hours, and the amount of biofilm inhibition was measured using crystal violet staining. The variations in optical densities (ODs) were used to quantify the percentage of biofilm inhibition. The isolates were deemed as strong if the OD was more than 0.240, Moderate if the OD was between 0.120 and 0.240 and weak if the OD was less than 0.120 [

22].

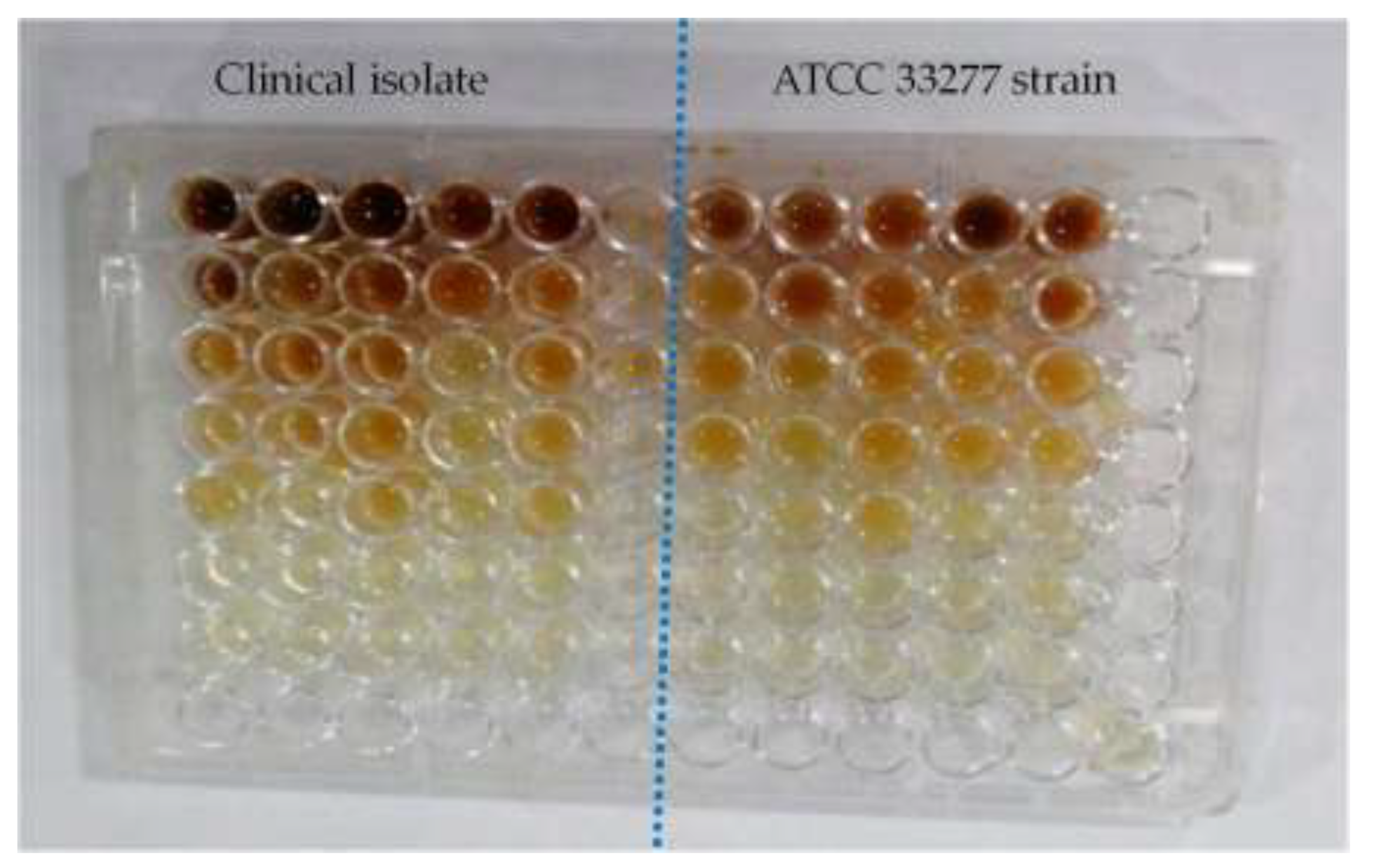

2.4. Detection of Acylated Homoserine Lactones (AHLs)

AHLs, a crucial component of

P. gingivalis's quorum sensing, were determined using a colorimetric technique [

23]. At different dilutions, the effects of Symphytum Officinale, Panax Ginseng, and Metronidazole on the generation of AHLs by two

P. gingivalis strains were observed in

Figure 2.

2.5. Quorum Sensing Inhibition Assay

The potential of the plant extracts to inhibit quorum sensing was assessed by using a colorimetric method, which produces orange pigmentation in the presence of AHL, a quorum sensing molecule. The reporter strain was co-cultured with

P. gingivalis in the presence and absence of plant extracts. The intensity of orange pigmentation was taken as a measure of AHL activity and was quantified spectrophotometrically. The isolates were deemed to produce weak or negative AHLs if the OD was less than 0.98 [

24]. the negative control (-) without AHLs signal molecules and the positive control (+) with AHLs signal molecules.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted with the assistance of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's multiple comparison tests. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

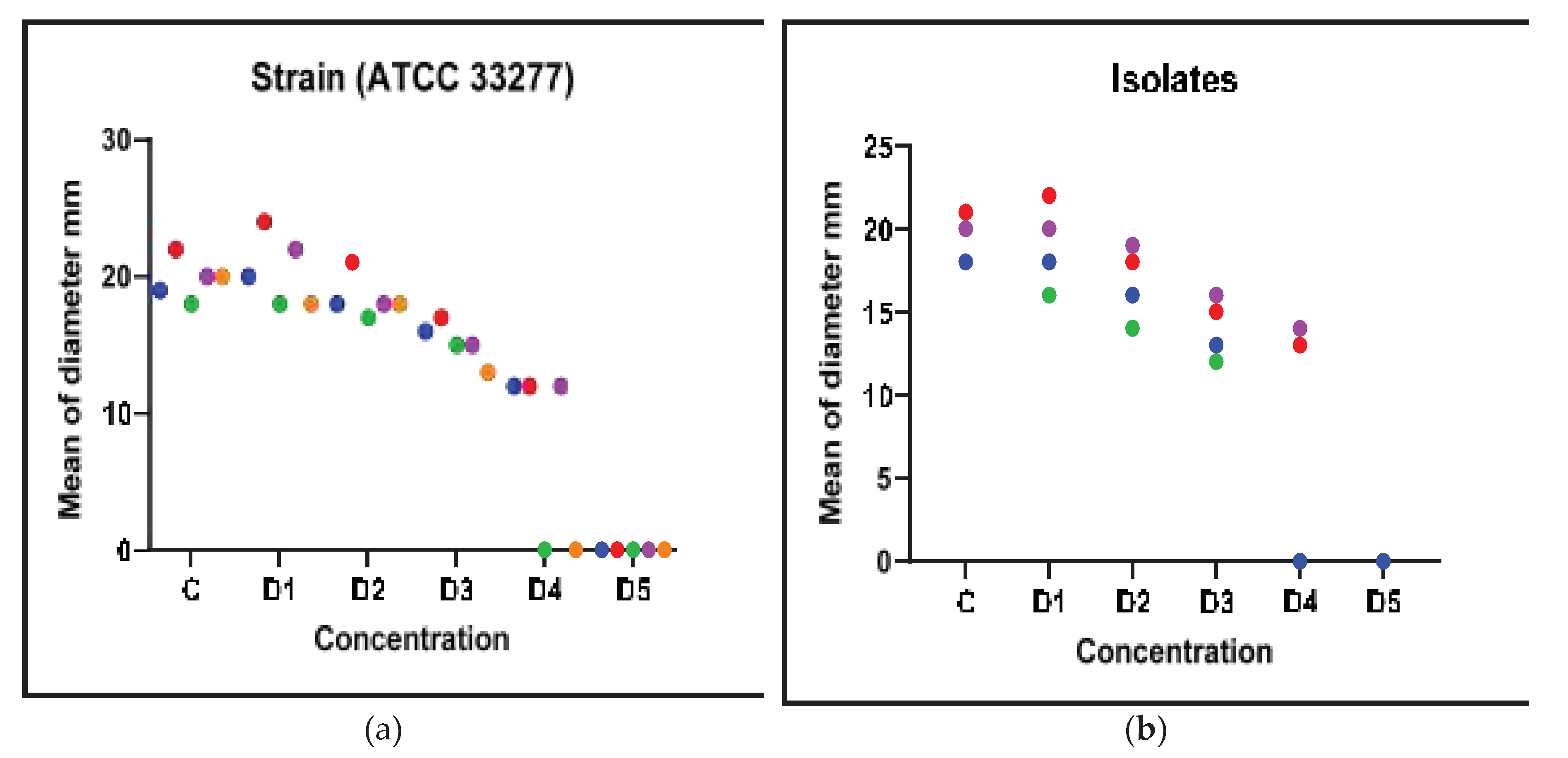

3.1. Antibacterial Activity of Plant Extracts and Metronidazole

The initial assessment was based on the antibacterial properties of Metronidazole, Panax Ginseng, and Symphytum Officinale (Comfrey). Antibacterial efficacy of the plants extracts and Metronidazole against the standard bacterial strain

(P. gingivalis ATCC 33277) and the clinical isolate was evaluated separately and in combination. The outcomes showed a clear antibacterial activity, with diverse effects at various doses (

Table 1) only D4 was nonsignificant for the strains (p > 0.05) (

Figure 3). While the lowest concentration D5 did not show any antibacterial activity at all.

3.2. Biofilm Inhibition Rate of Bacterial Standard Strain and Isolates

Under the impact of several experimental extracts, biofilm inhibition rates of the standard and isolated bacterial strains were compared. The substantial antibacterial activity of the test compounds was shown by the considerable variation in biofilm inhibition across the various treatments (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Antibacterial activities of plant extracts and Metronidazole

Table 2.

Antibacterial activities of plant extracts and Metronidazole

| Microorganism |

Concentration |

Mean inhibition zone diameter, D (mm) |

F-test |

P-value |

| G |

G+F |

S |

S+F |

F |

| Strain (ATCC 33277) |

C |

20.5120 |

24.0125 |

18.6111 |

22.0367 |

20.4119 |

132.25 |

0.000 |

| D1 |

20.2476 |

22.5019 |

18.2110 |

20.8970 |

18.2778 |

129.63 |

0.005 |

| D2 |

18.3017 |

21.000 |

17.1556 |

18.0000 |

18.2100 |

141.11 |

0.003 |

| D3 |

16.1506 |

17.8642 |

15.0556 |

15.6410 |

13.6321 |

128.63 |

0.001 |

| D4 |

12.000 |

12.2590 |

0 |

12.3780 |

0 |

99.52 |

0.142 |

| D5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

- |

| Isolate |

C |

18.3889 |

22.8690 |

18.5124 |

20.1056 |

20.1359 |

138.28 |

0.0025 |

| D1 |

18.2778 |

21.9810 |

16.2531 |

20.0245 |

18.0189 |

129.69 |

0.0015 |

| D2 |

16.5000 |

18.4587 |

14.4376 |

19.0849 |

14.5890 |

137.18 |

0.0032 |

| D3 |

13.6111 |

15.1398 |

12.1400 |

16.8941 |

12.3801 |

98.69 |

0.0015 |

| D4 |

18.3889 |

13.6782 |

0 |

14.7901 |

0 |

91.57 |

0.521 |

| D5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

- |

- |

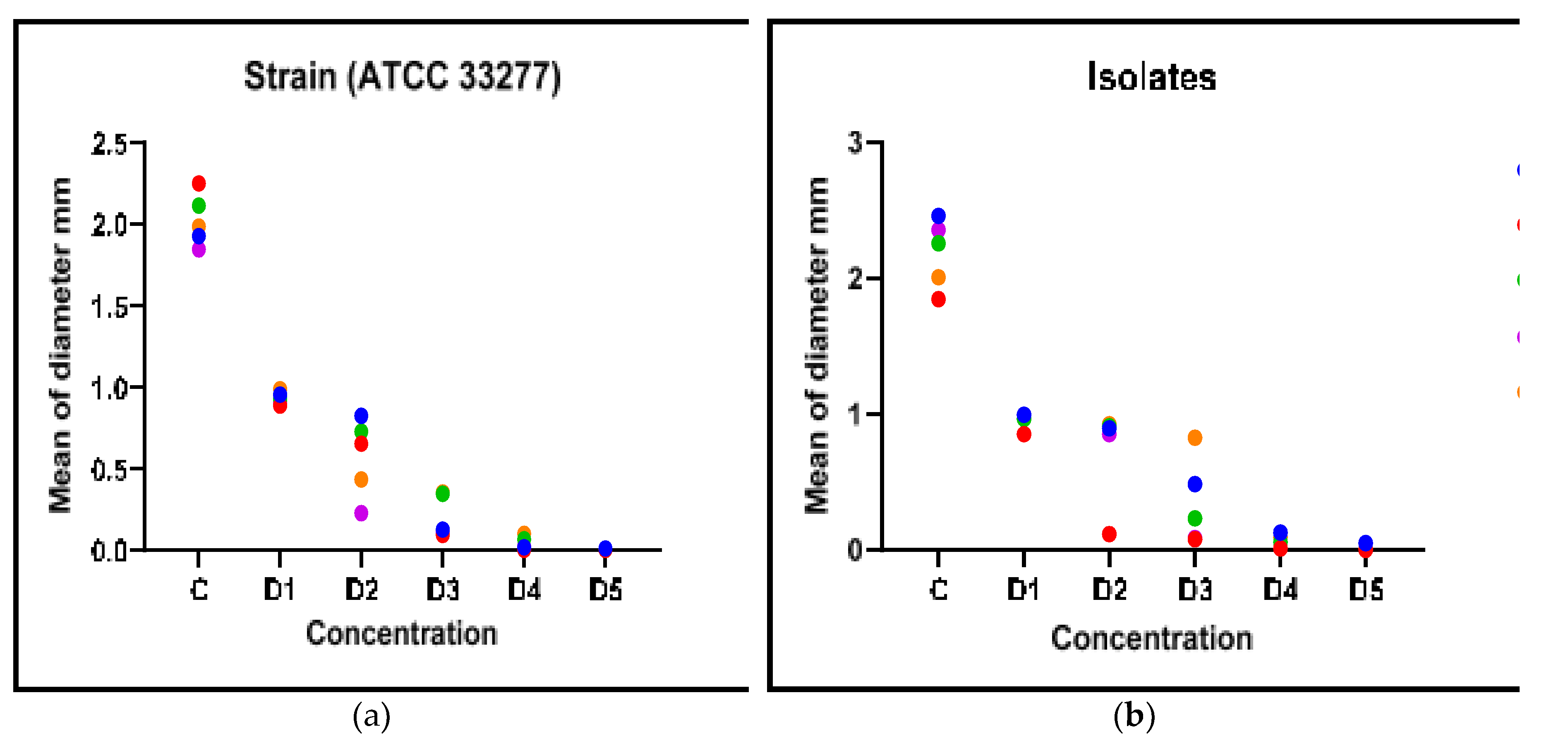

3.3. Acylated Homoserine Lactones (AHLs) Production

Finally, it was assessed how the plant extracts and the antibiotic metronidazole affected the creation of AHLs, an essential component of bacterial communication. As indicated in

Table 3, the plant extracts and metronidazole significantly inhibited the formation of AHLs (p <0.05).

Overall, the findings strongly suggested that Metronidazole, Panax Ginseng, and Symphytum Officinale (Comfrey) have antibacterial and biofilm inhibitory effects, suggesting that they may be used to treat

P. gingivalis infections. The fact was that these results remained true for both the common laboratory strain and clinical isolate indicating their significance in the actual clinical environment (

Figure 4).

3.4. Dose-Dependent Effects of G, S, and F

The results demonstrated dose-dependent nature due to the antibacterial and biofilm inhibiting effects of different doses of G, S, and F. D1 dose produced the most effective results with respect to the values of extract combination. The results of this study will be extremely useful in determining the combinations and concentrations of each medication that will have the greatest therapeutic impact p <0.05 (0.00014) (

Table 4).

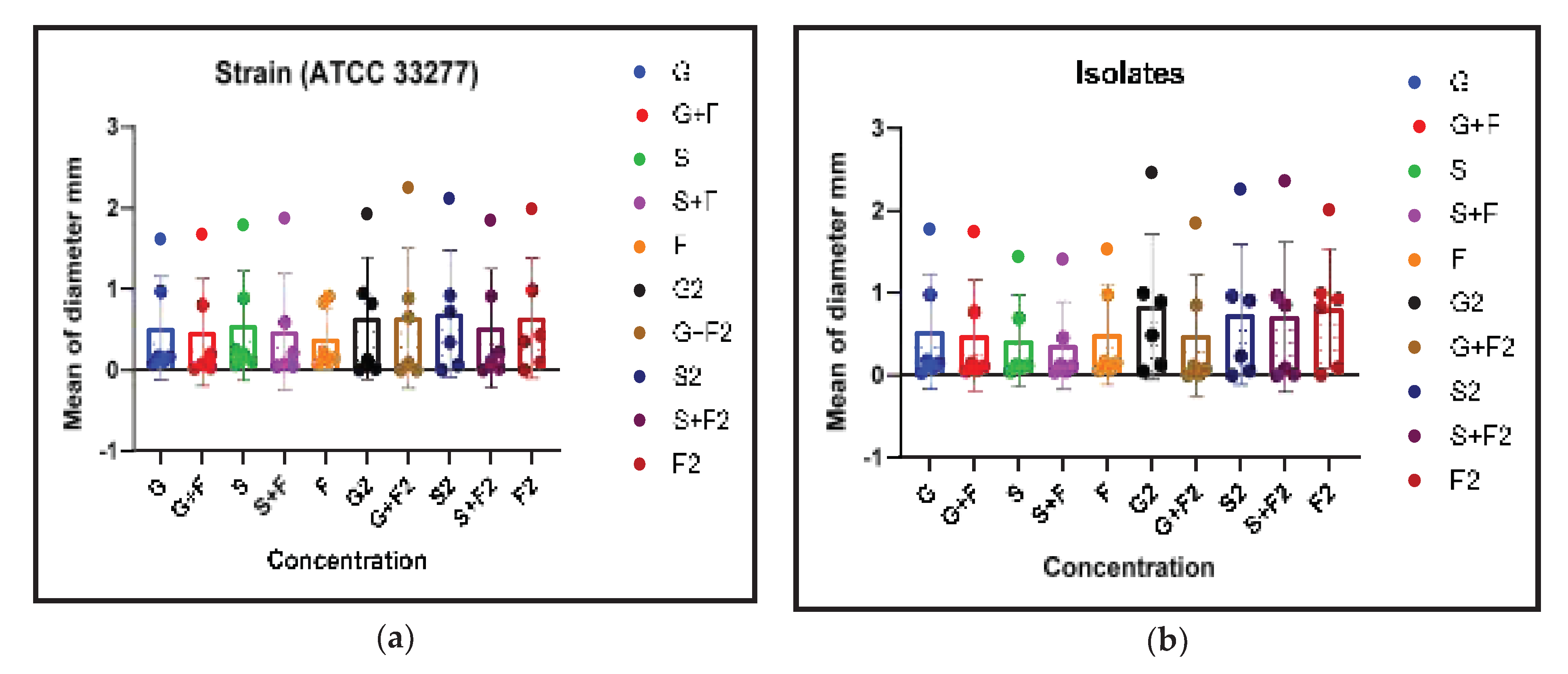

3.5. Correlation Between Biofilm Inhibition and AHL Production

This part presents the relationship, if any, between biofilm inhibition and AHL production in the clinical isolate and standard strain when G, S, and F were used. As indicated in

Figure 5, the plant extracts and metronidazole significantly inhibited the formation of biofilm and AHLs (p <0.05). This significant association, it could imply that the antibacterial and anti-biofilm actions of these medications are, at least in part, influenced by the disruption of bacterial quorum sensing mechanisms. Where G2, G+F2, S2, S+F2, F2 represent the extract doses that inhibited AHLS in strains and isolates, and there was a correlation (p<0.05) between them and biofilm inhibition.

4. Discussion

The current investigation focused on both a standard strain and clinically isolated bacteria to examine the inhibitory potential of Panax Ginseng (G), Symphytum Officinale (S), and Metronidazole (F) against

P. gingivalis. The results support earlier research showing that

P. gingivalis is very amenable to biofilm reduction through a variety of treatment approaches, both conventional and modern [

25]. When exposed to the tested treatments, a substantial suppression of biofilm formation was seen in both the standard strain and the clinical isolate. These findings are consistent with previous research demonstrating the powerful antibacterial and anti-biofilm capabilities of G, S, and F [

2].

Additionally, it appeared that the combination therapies (G+F, S+F) had a more prominent impact than the separate treatments, which may have been the result of a synergistic action by the two [

12]. The generation of AHL, a crucial component of bacterial quorum sensing, was successfully reduced by the tested treatments in both the clinical isolate and the standard strain, according to the research. The capacity of

P. gingivalis to coordinate group behaviour may be compromised by this restriction of AHL synthesis, which would reduce the pathogenic potential of the organism [

9]. Intriguingly, the separated bacteria were more energetic and active than the conventional strain, corroborating other studies that claim clinical isolates may display unique characteristics [

26]. However, the specific causes of this disparity are yet unknown and need more research. Depending on the treatment concentration, a sizable variance in the observed outcomes was noticed, pointing to a dose-response connection. This is in line with other studies showing that the concentration of antibacterial drugs frequently affects their effectiveness [

27].

A possible strategy for reducing bacterial pathogenicity is to disrupt quorum sensing processes. It is possible to significantly lessen the pathogenic potential of bacteria like

P. gingivalis by interfering with their coordination and communication. Bacterial quorum sensing, which is mediated by signal molecules like AHLs, has become a fascinating topic of research, especially in connection to bacterial pathogenicity and the development of durable biofilms [

5]. Notably, the current findings confirm the biofilm-inhibitory effects found by providing strong evidence that G, S, and F can impair quorum sensing with

P. gingivalis by preventing the generation of AHL. This capacity to interfere with the quorum sensing systems is consistent with other investigations that have noted the inhibitory effects of natural extracts on quorum sensing [

28]. The complexity of bacterial behaviour in actual clinical settings is highlighted by the increased activity that was seen in clinical isolates compared to the reference strain. It serves as a reminder that bacterial pathogenicity and medication resistance can differ greatly amongst strains, depending on a number of variables including their genetic make-up and the environment from which they are separated [

29].

The results showed a strong dose-dependent response for the inhibitory effects of G, S, and F. Other research investigating the antibacterial activity of natural extracts have shown that such a reaction is a typical characteristic of many antimicrobial compounds [

1]. These dose-response correlations are essential for pinpointing the precise concentrations that can produce the best therapeutic outcomes while minimising any side effects. When considered as a whole, these results highlight the promising antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities of G, S, and F against

P. gingivalis, suggesting potential for innovative treatments to avert or cure infections caused by bacteria that form biofilms.

This work adds to the expanding body of research that supports the use of natural extracts as alternatives or supplements to conventional antimicrobial treatments by confirming the ability of G, S, and F to disrupt these bacterial communication routes [

27]. Additionally, the synergistic effects of combining therapies (G+F, S+F) provide new avenues for creating more powerful and comprehensive treatment plans. The combination of several antibacterial drugs frequently leads in increased antibacterial effectiveness, as shown by the findings and those of other researchers [

30]. Therefore, it is important to investigate the ramifications of these synergistic effects, including any potential effects on lowering the probability of bacterial resistance.

The significant difference between the clinical isolate and standard strain of

P. gingivalis' susceptibility to the tested therapies can be attributed to a number of variables. The strain's sensitivity to antimicrobial drugs can be changed by differences in genetic variants, mutations, or the capacity to acquire resistance genes [

13]. Future research may focus on elucidating these elements and how they relate to

P. gingivalis infection treatment efficacy[

4].

The results of this investigation provide light on the efficacy of Metronidazole (F), Symphytum Officinale (S), and Panax Ginseng (G) as antibacterial and anti-biofilm agents against P. gingivalis. Further in vivo research is needed to verify these findings. The therapeutic potential and safety profile of these medicines might be further understood using animal models or human participants in clinical studies. While it was found in this study that G, S, and F can hinder quorum sensing in P. gingivalis by blocking the production of AHL, the fundamental mechanism underpinning this process are still not fully understood. The particular molecular processes by which these natural extracts and antibiotics disrupt quorum sensing pathways needs further investigation. This information will aid in the creation of more focused and successful therapy approaches.

This research is limited to providing enough number of samples and microbiological analyzing advance technique.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study focused on both a standard strain and clinically isolated bacteria to examine the inhibitory potential of Panax Ginseng (G), Symphytum Officinale (S), and Metronidazole (F) against P. gingivalis. The findings confirmed that P. gingivalis was susceptible to several biofilm-reduction therapy modalities. The antibacterial and anti-biofilm properties of G, S, and F, the tested treatments showed a significant inhibition of biofilm formation against both the standard strain and the clinical isolate. Combination therapy (G+F, S+F) had a more pronounced effect than the individual therapies, possibly as a result of synergistic activity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S. M. I., and A. S. A.; methodology, S. M. I., and A. S. A.; validation, S. M. I., A. S. A. and J. H.; formal analysis, S. M. I., A. S. A. and J. H.; investigation, S. M. I.; resources, S. M. I.; data curation, S. M. I.; writing—original draft preparation, S. M. I., A. S. A. and J. H.; writing—review and editing, S. M. I., A. S. A. and J. H.; visualization, S. M. I.; supervision, A. S. A. and J. H.

Funding

This research was funded by University of Iraqi Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research for their financial assistance (Grant No. [Protocol-3]).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study (Ethical approval Reference number 382).

Data Availability Statement

Upon reasonable request, the data created and examined during the current study can be made available.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the assistance and resources provided by the Department of Periodontics at the Baghdad College of Dentistry.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ray, R.R.; Pattnaik, S. Contribution of phytoextracts in challenging the biofilms of pathogenic bacteria. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 48, 102642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, A.M.; Rokaya, D.; Kathayat, G.; Afshari, J.T. Onco-immunity and therapeutic application of amygdalin: A review. J. Oral Biol. Craniofacial Res. 2022, 13, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Saliem, S.; Abdulkareem, A.; Radhi, H.; Gul, S. Evaluation of the efficacy of lycopene gel compared with minocycline hydrochloride microspheres as an adjunct to nonsurgical periodontal treatment: A randomised clinical trial. J. Dent. Sci. 2020, 16, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramani, R.; Narayanasamy, M.; Feussner, K.-D. Plant-derived antimicrobials to fight against multi-drug-resistant human pathogens. 3 Biotech 2017, 7, 172–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamont, R.J.; Fitzsimonds, Z.R.; Wang, H.; Gao, S. Role of Porphyromonas gingivalis in oral and orodigestive squamous cell carcinoma. Periodontology 2000 2022, 89, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. R. Ibraheem, N. N. Hussein, and G. M. Sulaiman, “Antibacterial Activity of Silver nanoparticles Against Pathogenic Bacterial Isolates from Diabetic Foot Patients,” Iraqi J. Sci., vol. 64, no. 5, pp. 2223–2239, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kareem, H.H.; Al-Ghurabi, B.H.; Albadri, C. Molecular Detection of Porphyromonas gingivalis in COVID-19 Patients. J. Baghdad Coll. Dent. 2022, 34, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, A.M.; Afshari, J.T. In Vivo Growth Inhibition of Human Caucasian Prostate Adenocarcinoma in Nude Mice Induced by Amygdalin with Metabolic Enzyme Combinations. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Salle, A.; Spagnuolo, G.; Conte, R.; Procino, A.; Peluso, G.; Rengo, C. Effects of various prophylactic procedures on titanium surfaces and biofilm formation. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2018, 48, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khorshid, M. Point of Care testing: The future of periodontal dis-ease diagnosis and monitoring. J. Baghdad Coll. Dent. 2022, 34, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalel, A.M.; Collage of Dentistry - University of Baghdad- Baghdad -Iraq; Fadhil, E. Histological and Immunohistochemical Study of Osteocalcin to Evaluate The Effect of Local Application of Symphytum Officinale Oil on Bone Healing on Rat. Diyala J. Med. 2020, 18, 71–78. [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, C.; Dell’agli, M.; Badea, M.; Dima, L.; Colombo, E.; Sangiovanni, E.; Restani, P.; Bosisio, E. Plant Food Supplements with Anti-Inflammatory Properties: A Systematic Review (II). Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Egra, H. Kuspradini, I. W. Kusuma, I. Batubara, K. Yamauchi, and T. Mitsunaga, “Garcidepsidone B from Garcinia parvifolia: antimicrobial activities of the medicinal plants from East and North Kalimantan against dental caries and periodontal disease pathogen,” Med. Chem. Res., pp. 1–8, 2023.

- Mohammed, A.E.; Aabed, K.; Benabdelkamel, H.; Shami, A.; Alotaibi, M.O.; Alanazi, M.; Alfadda, A.A.; Rahman, I. Proteomic Profiling Reveals Cytotoxic Mechanisms of Action and Adaptive Mechanisms of Resistance in Porphyromonas gingivalis: Treatment with Juglans regia and Melaleuca alternifolia. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 12980–12991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- H. Ullah et al., “In Vitro Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Properties and Bioaccessibility after Oral Digestion of Chemically Characterized Extracts Obtained from Cistus× incanus L., Scutellaria lateriflora L., and Their Combination,” Foods, vol. 12, no. 9, p. 1826, 2023. 10. [CrossRef]

- Mizutani, K.; Buranasin, P.; Mikami, R.; Takeda, K.; Kido, D.; Watanabe, K.; Takemura, S.; Nakagawa, K.; Kominato, H.; Saito, N.; et al. Effects of Antioxidant in Adjunct with Periodontal Therapy in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghdad Science Journal Structural Analysis of Chemical and Green Synthesis of CuO Nanoparticles and their Effect on Biofilm Formation. Baghdad Sci. J. 2018, 15, 211–216. [CrossRef]

- Berghänel, A.; Heistermann, M.; Schülke, O.; Ostner, J. Prenatal stress accelerates offspring growth to compensate for reduced maternal investment across mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2017, 114, E10658–E10666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredua-Agyeman, M.; Gaisford, S. Real time microcalorimetric profiling of prebiotic inulin metabolism. Food Hydrocoll. Heal. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavepour, N.; Bayati, M.; Rahimi, M.; Aliahmadi, A.; Ebrahimi, S.N. Optimization of aqueous extraction of henna leaves (Lawsonia inermis L.) and evaluation of biological activity by HPLC-based profiling and molecular docking techniques. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 195, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayama, K. Porphyromonas gingivalisand related bacteria: from colonial pigmentation to the typeIXsecretion system and gliding motility. J. Periodontal Res. 2014, 50, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakir, Sevan H., and Fattma A. Ali (2016). "Comparison of different methods for detection of biofilm production in multi-drug resistance bacteria causing pharyngotonsillitis." International journal of research h in pharmacy and biosciences 3.2: 13-22.

- Wei, E.S.; Kavitha, R.; Sa’ad, M.A.; Lalitha, P.; Fuloria, N.K.; Ravichandran, M.; Fuloria, S. Development of a Simple Protocol for Zymogram-Based Isolation and Characterization of Gingipains from Porphyromonas gingivalis: The Causative Agent of Periodontitis. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldiris, R., TeherÃ, V., Vivas-Reyes, R., Montes, A., & Arzuza, O. (2016). Anti-biofilm activity of ibuprofen and diclofenac against some biofilm producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae uropathogens. African Journal of Microbiology Research, 10(40), 1675-1684. [CrossRef]

- de Boer, C.G.; Hughes, T.R. YeTFaSCo: a database of evaluated yeast transcription factor sequence specificities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 40, D169–D179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Castillo, M.; Morosini, M.-I.; Gálvez, M.; Baquero, F.; del Campo, R.; Meseguer, M.-A. Differences in biofilm development and antibiotic susceptibility among clinical Ureaplasma urealyticum and Ureaplasma parvum isolates. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 62, 1027–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouidhi, B.; Al Qurashi, Y.M.A.; Chaieb, K. Drug resistance of bacterial dental biofilm and the potential use of natural compounds as alternative for prevention and treatment. Microb. Pathog. 2015, 80, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Packiavathy, I.A.S.V.; Kannappan, A.; Thiyagarajan, S.; Srinivasan, R.; Jeyapragash, D.; Paul, J.B.J.; Velmurugan, P.; Ravi, A.V. AHL-Lactonase Producing Psychrobacter sp. From Palk Bay Sediment Mitigates Quorum Sensing-Mediated Virulence Production in Gram Negative Bacterial Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 634593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M.C.; Ponce, A.G. Beet (Beta vulgaris) and Leek (Allium porrum) Leaves as a Source of Bioactive Compounds with Anti-quorum Sensing and Anti-biofilm Activity. Waste Biomass- Valorization 2019, 11, 4305–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, S.T.; Bassler, B.L. Bacterial Quorum Sensing: Its Role in Virulence and Possibilities for Its Control. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a012427–a012427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).