Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Aims

3. The Biological and Prognostic Significance of HSP Families in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma (PDAC)

3.1. Low-Molecular-Weight Heat Shock Protein (lmHSPs)

3.2. HSP40 (DnaJ Family)

3.3. HSP60 (Chaperonins)

3.4. HSP70

3.5. HSP90

4. The Role of HSP in Treating Pancreatic Cancer

4.1. HSP27: Marker of Resistance and Therapeutic Target

4.2. HSP47: Modulator of Tumor Microenvironment

4.3. HSP60: Regulator of Mitochondrial Metabolism and Tumor Immunogenicity

4.4. HSP70: Multifaceted Therapeutic Target

4.5. HSP90: Central Regulator of Oncogenic Stability

5. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

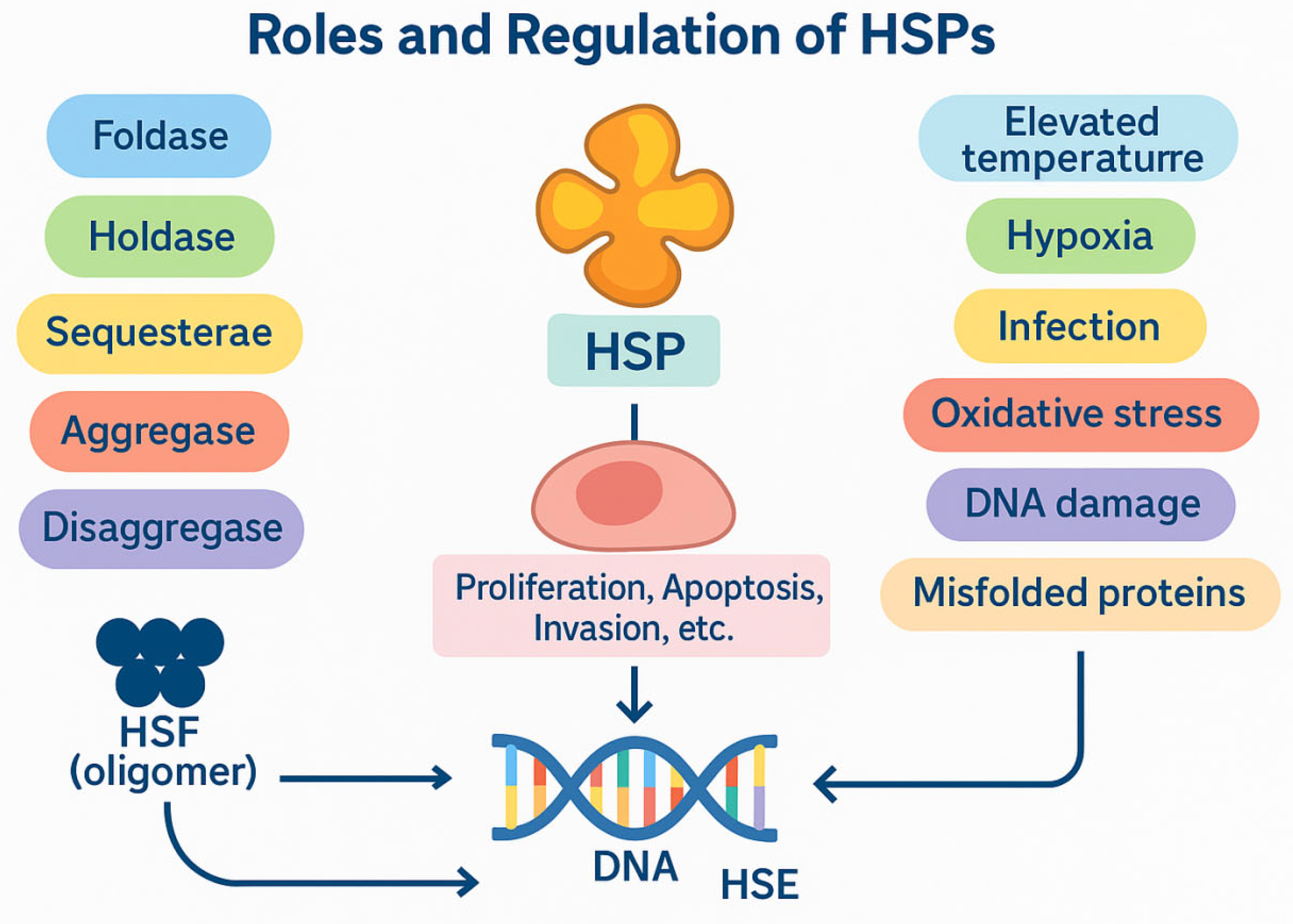

- Hu C, Yang J, Qi Z, Wu H, Wang B, Zou F, et al. Heat shock proteins: Biological functions, pathological roles, and therapeutic opportunities. MedComm. 2022 Sep 1;3(3). [CrossRef]

- Kakkar V, Meister-Broekema M, Minoia M, Carra S, Kampinga HH. Barcoding heat shock proteins to human diseases: Looking beyond the heat shock response. DMM Dis Model Mech. 2014;7(4):421–34. [CrossRef]

- Singh MK, Shin Y, Ju S, Han S, Choe W, Yoon KS, et al. Heat Shock Response and Heat Shock Proteins: Current Understanding and Future Opportunities in Human Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2024 Apr 10;25(8). [CrossRef]

- Melikov A, Biocev PN. Review Article Heat Shock Protein Network: the Mode of Action, the Role in Protein Folding and Human Pathologies (HSP / protein folding / chaperone / aggregation / neurodegenerative disease / cancer).

- Zuo WF, Pang Q, Zhu X, Yang QQ, Zhao Q, He G, et al. Heat shock proteins as hallmarks of cancer: insights from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. J Hematol Oncol. 2024 Dec 1;17(1):81. [CrossRef]

- Yun CW, Kim HJ, Lim JH, Lee SH. Heat shock proteins: Agents of cancer development and therapeutic targets in anti-cancer therapy. Cells. 2020 Jan 1;9(1). [CrossRef]

- Lau R, Yu L, Roumeliotis TI, Stewart A, Pickard L, Riisanes R, et al. Unbiased differential proteomic profiling between cancer-associated fibroblasts and cancer cell lines. J Proteomics. 2023 Sep 30;288. [CrossRef]

- Zhang S, Zhang XQ, Huang SL, Chen M, Shen SS, Ding XW, et al. The effects of HSP27 on gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cell line through snail. Pancreas. 2015 Oct 1;44(7):1121–9. [CrossRef]

- Deng M, Chen PC, Xie S, Zhao J, Gong L, Liu J, et al. The small heat shock protein αA-crystallin is expressed in pancreas and acts as a negative regulator of carcinogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Basis Dis. 2010 Jul 1;1802(7–8):621–31. [CrossRef]

- Liu P, Zu F, Chen H, Yin X, Tan X. Exosomal DNAJB11 promotes the development of pancreatic cancer by modulating the EGFR/MAPK pathway. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2022 Dec 1;27(1):1–20. [CrossRef]

- Roth HE, Bhinderwala F, Franco R, Zhou Y, Powers R. DNAJA1 Dysregulates Metabolism Promoting an Antiapoptotic Phenotype in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. J Proteome Res. 2021 Aug 6;20(8):3925–39. [CrossRef]

- Zhou C, Sun H, Zheng C, Gao J, Fu Q, Hu N, et al. Oncogenic HSP60 regulates mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation to support Erk1/2 activation during pancreatic cancer cell growth. Cell Death Dis 2018 92. 2018 Feb 7;9(2):1–14. [CrossRef]

- Xiong L, Li D, Xiao G, Tan S, Xu L, Wang G. HSP70 promotes pancreatic cancer cell epithelial-mesenchymal transformation and growth via the NF-κB signaling pathway. Pancreas. 2024 Feb 1;54(2). [CrossRef]

- Zhai LL, Qiao PP, Sun YS, Ju TF, Tang ZG. Tumorigenic and immunological roles of Heat shock protein A2 in pancreatic cancer: a bioinformatics analysis. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2022;68(4):470–5. [CrossRef]

- Wu HY, Trevino JG, Fang BL, Riner AN, Vudatha V, Zhang GH, et al. Patient-Derived Pancreatic Cancer Cells Induce C2C12 Myotube Atrophy by Releasing Hsp70 and Hsp90. Cells. 2022 Sep 1;11(17). [CrossRef]

- Yang J, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Ni X, Zhang G, Cui X, et al. ZIP4 Promotes Muscle Wasting and Cachexia in Mice With Orthotopic Pancreatic Tumors by Stimulating RAB27B-Regulated Release of Extracellular Vesicles From Cancer Cells. Gastroenterology. 2019 Feb 1;156(3):722-734.e6. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Ware MB, Zaidi MY, Ruggieri AN, Olson BM, Komar H, et al. Heat shock protein-90 inhibition alters activation of pancreatic stellate cells and enhances the efficacy of PD-1 blockade in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2021 Jan 1;20(1):150–60. [CrossRef]

- Gulla A, Strupas K, Chun M, Wanglong Q, Su G. Heat Shock Protein 90: Target Molecular Regulator in Acute Pancreatitis and Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. HPB. 2023;25:S440. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Zhang J, Wu H, Li Y, Conti PS, Chen K. PET imaging of Hsp90 expression in pancreatic cancer using a new 64Cu-labeled dimeric Sansalvamide A decapeptide. Amino Acids. 2018 Jul 1;50(7):897–907. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Han Z, Zhang J, Chen M, Meng W. Development and Preclinical Evaluation of 18F-Labeled PEGylated Sansalvamide A Decapeptide for Noninvasive Evaluation of Hsp90 Status in Pancreas Cancer. Mol Pharm. 2024 Oct 7;21(10):5238–46. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Zhang J, Han Z, Ma L, Li Y. 18F-labeled Dimer-Sansalvamide A Cyclodecapeptide: A Novel Diagnostic Probe to Discriminate Pancreatic Cancer from Inflammation in a Nude Mice Model. J Cancer. 2022;13(6):1848–58. [CrossRef]

- Richter K, Haslbeck M, Buchner J. The Heat Shock Response: Life on the Verge of Death. Mol Cell. 2010 Oct;40(2):253–66. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Zhao J, Tian Y, Jin H. Cellular functions of heat shock protein 20 (HSPB6) in cancer: A review. Cell Signal. 2023 Dec 1;112:110928. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Yang L, Du K. Exosomal HSPB1, interacting with FUS protein, suppresses hypoxia-induced ferroptosis in pancreatic cancer by stabilizing Nrf2 mRNA and repressing P450. J Cell Mol Med. 2024 May 1;28(9):e18209. [CrossRef]

- Yu Z, Wang H, Fang Y, Lu L, Li M, Yan B, et al. Molecular chaperone HspB2 inhibited pancreatic cancer cell proliferation via activating p53 downstream gene RPRM, BAI1, and TSAP6. J Cell Biochem. 2020 Mar 1;121(3):2318–29. [CrossRef]

- Yun CW, Kim HJ, Lim JH, Lee SH. Heat shock proteins: Agents of cancer development and therapeutic targets in anti-cancer therapy. Cells. 2020 Jan 1;9(1). [CrossRef]

- Montresor S, Pigazzini ML, Baskaran S, Sleiman M, Adhikari G, Basilicata L, et al. HSP110 is a modulator of amyloid beta (Aβ) aggregation and proteotoxicity. J Neurochem. 2024 Jan 1;169(1). [CrossRef]

- Evans CG, Chang L, Gestwicki JE. Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) as an emerging drug target. J Med Chem. 2010 Jun 24;53(12):4585–602. [CrossRef]

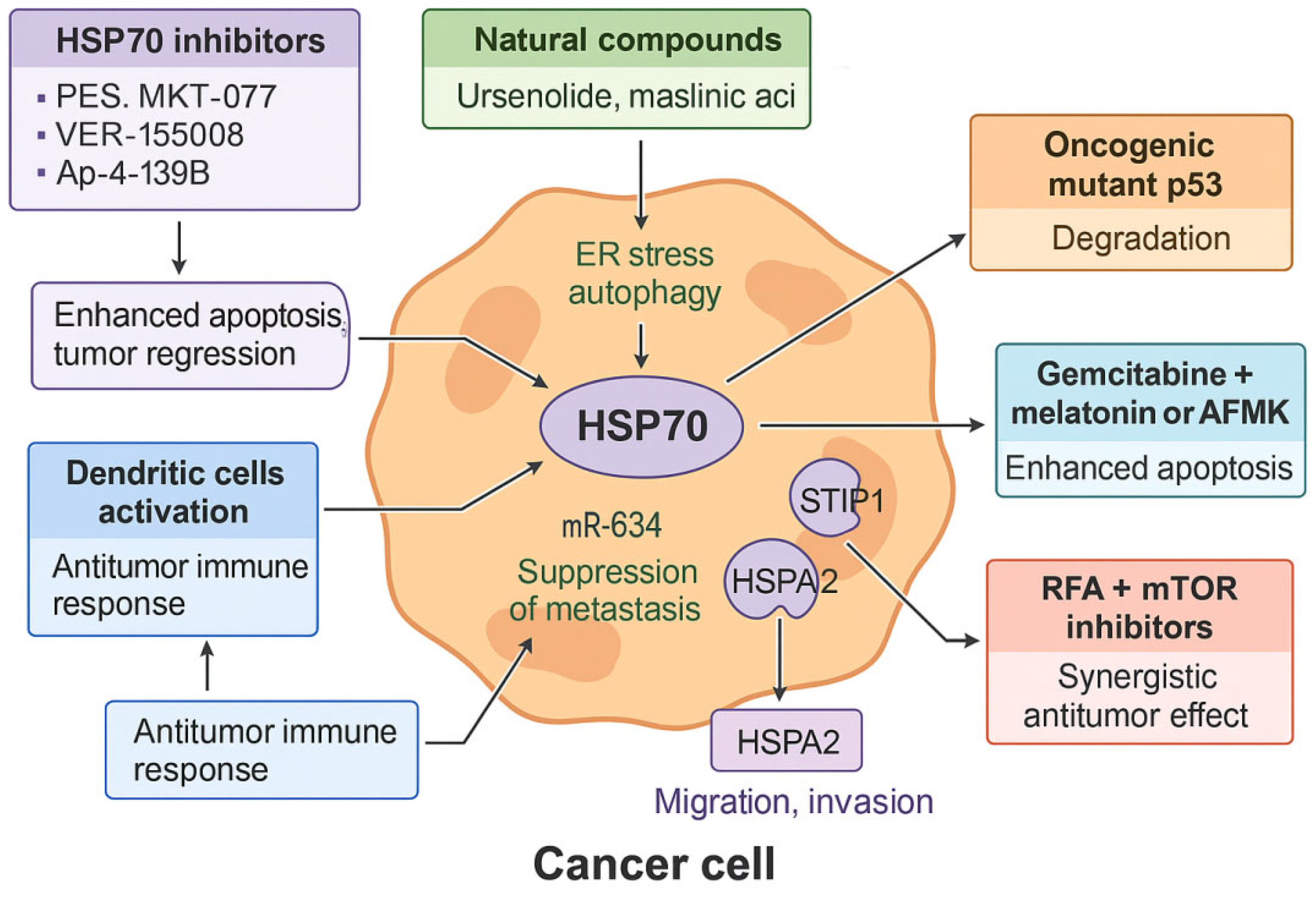

- Sha G, Jiang Z, Zhang W, Jiang C, Wang D, Tang D. The multifunction of HSP70 in cancer: Guardian or traitor to the survival of tumor cells and the next potential therapeutic target. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023 Sep 1;122. [CrossRef]

- Youness RA, Gohar A, Kiriacos CJ, El-Shazly M. Heat Shock Proteins: Central Players in Oncological and Immuno-Oncological Tracks. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2023;1409:193–203. [CrossRef]

- Zuo WF, Pang Q, Zhu X, Yang QQ, Zhao Q, He G, et al. Heat shock proteins as hallmarks of cancer: insights from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. J Hematol Oncol. 2024 Dec 1;17(1). [CrossRef]

- Nawaz MS, Fournier-Viger P, Nawaz S, Gan W, He Y. FSP4HSP: Frequent sequential patterns for the improved classification of heat shock proteins, their families, and sub-types. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024 Oct 1;277(Pt 1). [CrossRef]

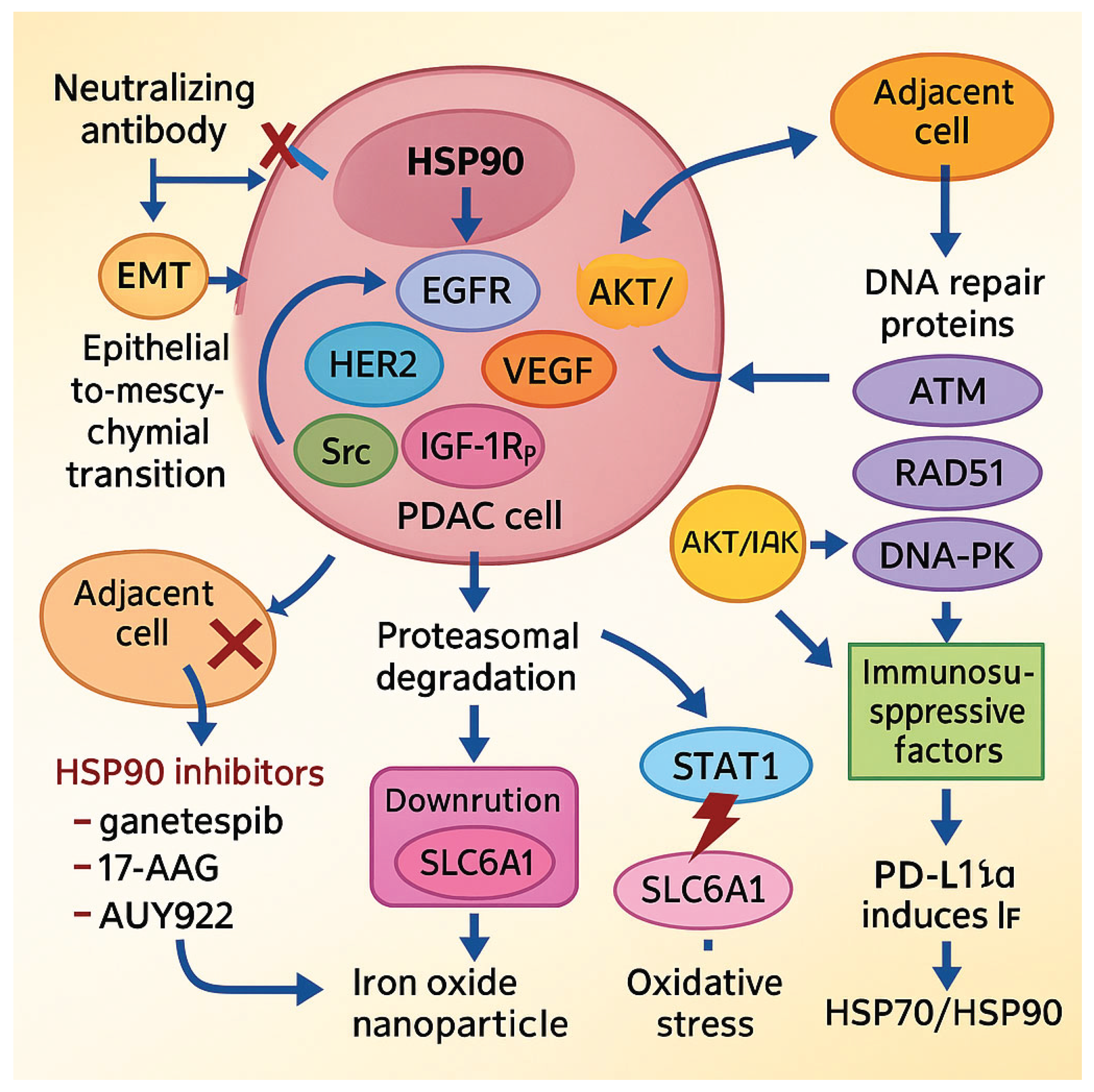

- Peng YF, Lin H, Liu DC, Zhu XY, Huang N, Wei YX, et al. Heat shock protein 90 inhibitor ameliorates pancreatic fibrosis by degradation of transforming growth factor-β receptor. Cell Signal. 2021 Aug 1;84. [CrossRef]

- Neckers L, Workman P. Hsp90 molecular chaperone inhibitors: Are we there yet? Clin Cancer Res. 2012 Jan 1;18(1):64–76. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, Chen Z, Li Z, Zhao X, Zhang W, Zhang A, et al. Hsp90α promotes chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer by regulating Keap1-Nrf2 axis and inhibiting ferroptosis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2024 Feb 1;57(2). [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Li H, Liu Y, Zhao K, Wei S, Sugarman ET, et al. Targeting HSP90 as a Novel Therapy for Cancer: Mechanistic Insights and Translational Relevance. Cells 2022, Vol 11, Page 2778. 2022 Sep 6;11(18):2778. [CrossRef]

- Malkeyeva D, Kiseleva E V., Fedorova SA. Heat shock proteins in protein folding and reactivation. Vavilov J Genet Breed. 2025 Mar 2;29(1):7–14. [CrossRef]

- Lee G, Kim RS, Lee SB, Lee S, Tsai FTF. Deciphering the mechanism and function of Hsp100 unfoldases from protein structure. Biochem Soc Trans. 2022 Dec 1;50(6):1725–36. [CrossRef]

- Wu PK, Hong SK, Starenki D, Oshima K, Shao H, Gestwicki JE, et al. Mortalin/HSPA9 targeting selectively induces KRAS tumor cell death by perturbing mitochondrial membrane permeability. Oncogene. 2020 May 21;39(21):4257–70. [CrossRef]

- Fang Z, Liang W, Luo L. HSP27 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition through activation of the β-catenin/MMP3 pathway in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells. Transl Cancer Res. 2019;8(4):1268–78. [CrossRef]

- Grierson PM, Dodhiawala PB, Cheng Y, Chen THP, Khawar IA, Wei Q, et al. The MK2/Hsp27 axis is a major survival mechanism for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma under genotoxic stress. Sci Transl Med. 2021 Dec 1;13(622). [CrossRef]

- Crake R, Gasmi I, Dehaye J, Lardinois F, Peiffer R, Maloujahmoum N, et al. Resistance to Gemcitabine in Pancreatic Cancer Is Connected to Methylglyoxal Stress and Heat Shock Response. Cells. 2023 May 1;12(10). [CrossRef]

- Tamtaji OR, Mirhosseini N, Reiter RJ, Behnamfar M, Asemi Z. Melatonin and pancreatic cancer: Current knowledge and future perspectives. J Cell Physiol. 2019 May 1;234(5):5372–8. [CrossRef]

- Hussain MS, Mujwar S, Babu MA, Goyal K, Chellappan DK, Negi P, et al. Pharmacological, computational, and mechanistic insights into triptolide’s role in targeting drug-resistant cancers. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2025 Jun 1;398(6). [CrossRef]

- Kuhara K, Tokuda K, Kitagawa T, Baron B, Tokunaga M, Harada K, et al. CUB Domain-containing Protein 1 (CDCP1) is down-regulated by active hexose-correlated compound in human pancreatic cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2018 Nov 1;38(11):6107–11. [CrossRef]

- Drexler R, Wagner KC, Küchler M, Feyerabend B, Kleine M, Oldhafer KJ. Significance of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated heat shock protein 27 as a prognostic biomarker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020 May 1;146(5):1125–37. [CrossRef]

- Yoneda A, Minomi K, Tamura Y. Heat shock protein 47 confers chemoresistance on pancreatic cancer cells by interacting with calreticulin and IRE1α. Cancer Sci. 2021 Jul 1;112(7):2803–20. [CrossRef]

- Duarte BDP, Bonatto D. The heat shock protein 47 as a potential biomarker and a therapeutic agent in cancer research. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018 Dec 1;144(12):2319–28. [CrossRef]

- Han X, Li Y, Xu Y, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Yang X, et al. Reversal of pancreatic desmoplasia by re-educating stellate cells with a tumour microenvironment-activated nanosystem. Nat Commun 2018 91. 2018 Aug 23;9(1):1–18. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood J, Shukla HD, Soman S, Samanta S, Singh P, Kamlapurkar S, et al. Immunotherapy, Radiotherapy, and Hyperthermia: A Combined Therapeutic Approach in Pancreatic Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2018, Vol 10, Page 469. 2018 Nov 28;10(12):469. [CrossRef]

- Ferretti GDS, Quaas CE, Bertolini I, Zuccotti A, Saatci O, Kashatus JA, et al. HSP70-mediated mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy represent a novel vulnerability in pancreatic cancer. Cell Death Differ 2024 317. 2024 May 28;31(7):881–96. [CrossRef]

- Tian Y, Xu H, Farooq AA, Nie B, Chen X, Su S, et al. Maslinic acid induces autophagy by down-regulating HSPA8 in pancreatic cancer cells. Phyther Res. 2018 Jul 1;32(7):1320–31. [CrossRef]

- Giri B, Sharma P, Jain T, Ferrantella A, Vaish U, Mehra S, et al. Hsp70 modulates immune response in pancreatic cancer through dendritic cells. Oncoimmunology. 2021;10(1). [CrossRef]

- Polireddy K, Singh K, Pruski M, Jones NC, Manisundaram N V., Ponnela P, et al. Mutant p53 R175H promotes cancer initiation in the pancreas by stabilizing HSP70. Cancer Lett. 2019 Jul 1;453:122–30. [CrossRef]

- Zhu S, Zhang Q, Sun X, Zeh HJ, Lotze MT, Kang R, et al. HSPA5 regulates ferroptotic cell death in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2017 Apr 15;77(8):2064–77. [CrossRef]

- Leja-Szpak A, Nawrot-Porąbka K, Góralska M, Jastrzębska M, Link-Lenczowski P, Bonior J, et al. Melatonin and its metabolite N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine (afmk) enhance chemosensitivity to gemcitabine in pancreatic carcinoma cells (PANC-1). Pharmacol Reports. 2018 Dec 1;70(6):1079–88. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Wu G, Sun H, Ding J, Xia F, Li X, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients fitting the Milan criteria: A single centre with 13 years experience. Int J Hyperth. 2014;30(7):471–9. [CrossRef]

- Jing Y, Liang W, Liu J, Zhang L, Wei J, Zhu Y, et al. Stress-induced phosphoprotein 1 promotes pancreatic cancer progression through activation of the FAK/AKT/MMP signaling axis. Pathol Res Pract. 2019 Nov 1;215(11). [CrossRef]

- Park HR. Pancastatin A and B Have Selective Cytotoxicity on Glucose-Deprived PANC-1Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020 May 28;30(5):733–8. [CrossRef]

- Tang R, Kimishima A, Setiawan A, Arai M. Secalonic acid D as a selective cytotoxic substance on the cancer cells adapted to nutrient starvation. J Nat Med. 2020 Mar 1;74(2):495–500. [CrossRef]

- Xue N, Lai F, Du T, Ji M, Liu D, Yan C, et al. Chaperone-mediated autophagy degradation of IGF-1Rβ induced by NVP-AUY922 in pancreatic cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019 Sep 1;76(17):3433–47. [CrossRef]

- Rochani AK, Balasubramanian S, Girija AR, Maekawa T, Kaushal G, Sakthi Kumar D. Heat Shock Protein 90 (Hsp90)-Inhibitor-Luminespib-Loaded-Protein-Based Nanoformulation for Cancer Therapy. Polym 2020, Vol 12, Page 1798. 2020 Aug 11;12(8):1798. [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju GP, Zakka KM, Landry JC, Shaib WL, Lesinski GB, El-Rayes BF. Inhibition of HSP90 overcomes resistance to chemotherapy and radiotherapy in pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 2019 Sep 15;145(6):1529–37. [CrossRef]

- Mehta RK, Pal S, Kondapi K, Sitto M, Dewar C, Devasia T, et al. Low-Dose Hsp90 Inhibitor Selectively Radiosensitizes HNSCC and Pancreatic Xenografts. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 Oct 1;26(19):5246–57. [CrossRef]

- Fan CS, Chen LL, Hsu TA, Chen CC, Chua KV, Li CP, et al. Endothelial-mesenchymal transition harnesses HSP90α-secreting M2-macrophages to exacerbate pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2019 Dec 17;12(1):1–15. [CrossRef]

- Zhao ZX, Li S, Liu LX. Thymoquinone affects hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression in pancreatic cancer cells via HSP90 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways. World J Gastroenterol. 2024 Jun 7;30(21):2793–816. [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui FA, Parkkola H, Vukic V, Oetken-lindholm C, Jaiswal A, Kiriazis A, et al. Novel Small Molecule Hsp90/Cdc37 Interface Inhibitors Indirectly Target K-Ras-Signaling. Cancers 2021, Vol 13, Page 927. 2021 Feb 23;13(4):927. [CrossRef]

- Nałęcz KA. Amino Acid Transporter SLC6A14 (ATB0,+) – A Target in Combined Anti-cancer Therapy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020 Oct 21;8:594464. [CrossRef]

- Gulla A, Kazlauskas E, Liang H, Strupas K, Petrauskas V, Matulis D, et al. Heat Shock Protein 90 Inhibitor Effects on Pancreatic Cancer Cell Cultures. Pancreas. 2021 Apr 1;50(4):625–32. [CrossRef]

- Grbovic-Huezo O, Pitter KL, Lecomte N, Saglimbeni J, Askan G, Holm M, et al. Unbiased in vivo preclinical evaluation of anticancer drugs identifies effective therapy for the treatment of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Dec 1;117(48):30670–8. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Kang R, Kroemer G, Tang D. Targeting HSP90 sensitizes pancreas carcinoma to PD-1 blockade. Oncoimmunology. 2022 Dec 31;11(1). [CrossRef]

- Tang D, Kang R. HSP90 as an emerging barrier to immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Oncoscience. 2022 Apr 22;9:20–2. [CrossRef]

- Balas M, Predoi D, Burtea C, Dinischiotu A. New Insights into the Biological Response Triggered by Dextran-Coated Maghemite Nanoparticles in Pancreatic Cancer Cells and Their Potential for Theranostic Applications. Int J Mol Sci 2023, Vol 24, Page 3307. 2023 Feb 7;24(4):3307. [CrossRef]

- Gao S, Pu N, Yin H, Li J, Chen Q, Yang M, et al. Radiofrequency ablation in combination with an mTOR inhibitor restrains pancreatic cancer growth induced by intrinsic HSP70. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2020;12. [CrossRef]

| HSP Family | Pathological Role in PDAC | References |

| lmHSPs | Ferroptosis inhibition, promoting chemioresistance via Snail/E-cadherin/ERCC1 (HSP27); tumor suppression via p53 (HSPB2) | [8,22,23,24,25] |

| HSP40 (DnaJ Family) | Promoting PDAC development via BiP/GRP78 (DnaJB11); apoptosis inhibition, promoting invasiveness, enhancing Warburg effect and Bcl-2 expression (DnaJA1) | [10,11,26] |

| HSP60 (Chaperonins) | Apoptosis inhibition via HSP60/OXPHOS/Erk1/2 pathway; overexpression correlates with PDAC severity | [3,12,22] |

| HSP70 | Promoting EMT via NF-κB; development of cachexia via p38βMAPK; overexpression in tumor cells and CAFs (HSPA2) | [3,5,13,14,15,16,27,28,29,30] |

| HSP90 | Ferroptosis resistance via Nrf2\GPx; mutant p53 stabilization; inducing invassiveness via MMP2/9 activtion; promoting EMT and immune evasion | [31,32,33,34,35,36] |

| Large HSPs (HSP100) | Unknown | [31,32,37,38] |

| Marker (HSP) | Diagnostic/Prognostic Relevance | Methods/Models | References |

| HSPB6 | Overexpressed in cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs); associated with improved overall survival in patients with PDAC; prognostic marker in PDAC | Mass spectrometry analysis of cancer-associated fibroblasts and cancer cell lines (Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium) | [7] |

| HSPB1 (HSP27) | Lower expression linked to poor overall survival in patients with PDAC after resection and liver metastases; higher expression associated with a better response to gemcitabine in the resected, non-metastasisedpatients group | Immunoreactive score (IRS), post-resection PDAC patient data (Dexter et al.) | [46] |

| HSP90 | High levels indicate poor prognosis; in PET imaging the expression of this protein enables monitoring and early detection of pancreatic cancer; | PET radiotracers, mouse model, immunochemistry (Wang et al.); pathologic data (Gamboa et al.); mice and rat models (Kacar et al.) | [18,19,20,21] |

| Strategy/Compound | Mechanism of Action | Targeted HSPs | References |

| Triptolide (TPL) | HSF1 inhibition and caspase-3, caspase-9 degradation promotes apoptosis and leads to increased tumor sensitivity to chemotherapy | HSP27, HSP70, HSP90 | [39] |

| Active hexose-correlated compound (AHCC) | Gemcytabine/methylglyoxal pathway leads to overexpression of HSP27, which is downregulated by AHCC inducing apoptosis and preventing resistance to chemotherapy | HSP27 | [45] |

| siRNA + ATRA delivered by PEGylated polyethylenimine-coated gold nanoparticles | HSP47-specific mRNA degradation by siRNA prevents ECM proliferation and increases gemcytabine sensitivity | HSP47 | [49] |

| AK-778,Col003,Pirfenidon | Direct inhibition of HSP47 inhibits tumor growth and increases gemcytabine sensitivity | HSP47 | [48] |

| Local hyperthermia | Increases tumor antigenicity and drug penetration by enhancing HSP70 and HSP60 expression; HSP70 promotes anti-tumor immune response, while HSP60 activates T cells and IFN-γ secretion | HSP60, HSP70 | [50] |

| Metformin + aminoguanidine | GLO-1 inhibition interferes with methylglyoxal/HSP27/HSP70 pathway increasing PDAC sensitivity to gemcytabine | HSP27, HSP70 | [42] |

| Melatonin | HSP27, HSP60, HSP70, HSP90 and HSP100 downregulation via NF-κB and STAT3 inhibition promotes apoptosis and increases tumor sensitivity to chemotherapy | HSP27, HSP60, HSP70, HSP90, HSP100 | [45] |

| Melatonin, AFMK | Suppression of HSP70 and cIAP-2 enhances gemcitabine efficacy and promotes apoptosis | HSP70 | [56] |

| Ap-4-139B + Hydroxychloroquine | Selective HSP70 inhibition induces mitochondrial swelling and activates the apoptotic pathway; combination with hydroxychloroquine (autophagy inhibitor) enhances antitumor efficacy | HSP70 | [51] |

| Pancastatin A and B | GRP78 (HSPA5) inhibition during glucose deprivation. | HSP70 | [59] |

| Xanthone derivative of secalonic acid D | AKT signaling pathway inhibition under glucose-starved condition and GRP78 (HSPA5) downregulation leads to cytotoxic activity on PANC-1 | HSP70 | [60] |

| Maslinic acid | Proliferation inhibition and inducing autophagy in PANC-28 through HSPA8 downregulation | HSP70 | [52] |

| DIO-NPs + HSP Inhibitors | DIO-NPs induce cellular stress leading to increased HSP70/HSP90 expression; combination with HSP inhibitors may impair survival mechanisms of PDAC and enhance therapy efficacy | HSP70, HSP90 | [73] |

| RFA + mTOR Inhibitors | Inhibition of RFA-induced via HSP70 AKT/mTOR pathway leads to suppression of proliferation and enhanced therapeutic response | HSP70 | [74] |

| JG-231 | Mortalin (HSPA9, GRP75) inhibition in K-RasG12C mutation PDAC increases the permeability of the mitochondrial membrane and promotes apoptosis | HSP70 | [39] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).