Submitted:

15 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Nexus Between Financial Development, Energy Consumption, Economic Growth, and Environmental Degradation

2.2. Nexus Between Renewable Energy, energy consumption and environmental degradation

2.3. Nexus Between Trade Openness and Environmental Degradation

2.4. Nexus Between Freight Transportation and Environmental Degradation

2.5. Nexus Between Industrialization and Environmental Degradation

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

3.2. Empirical Model

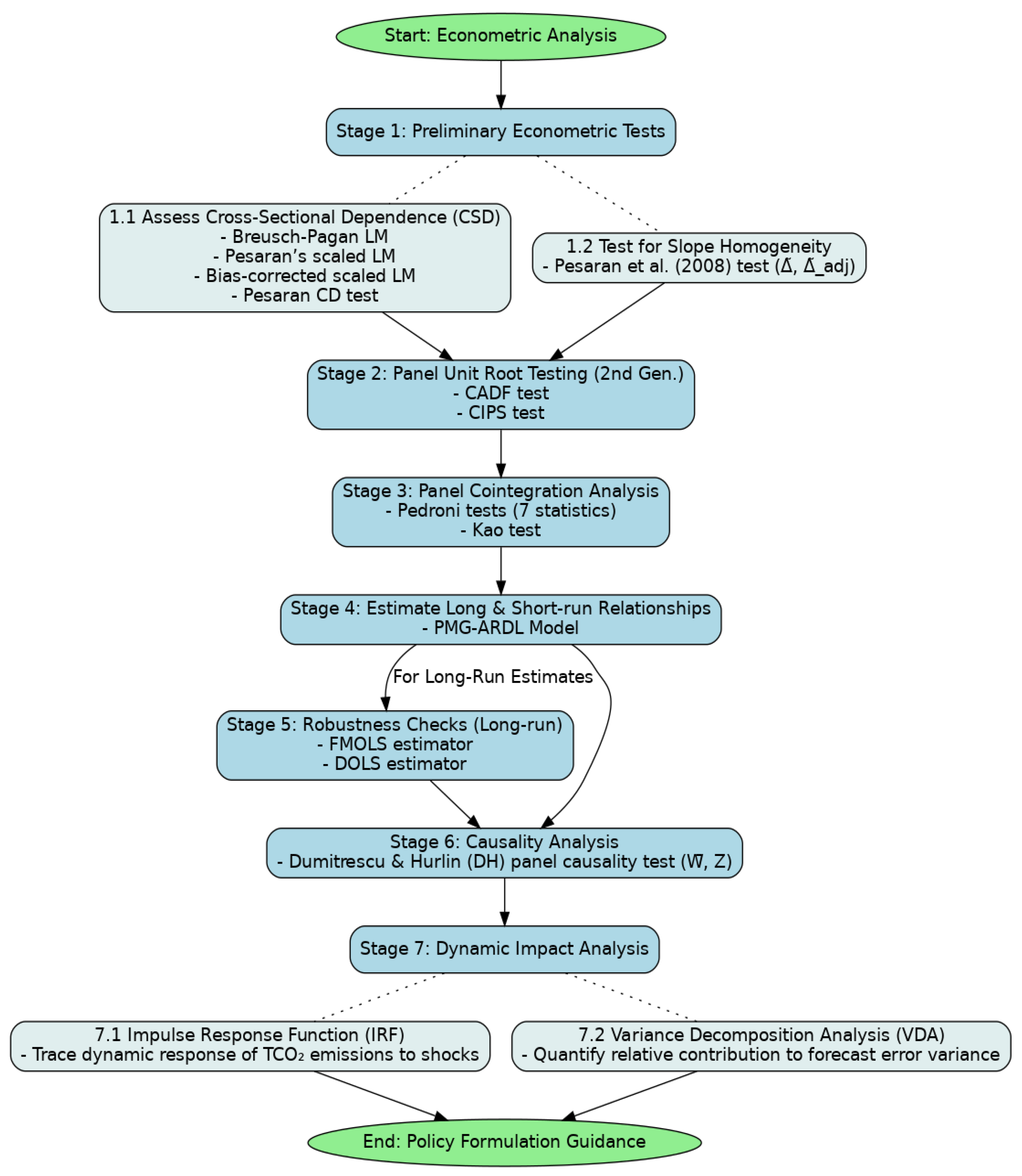

3.3. The Flowchart of the Analysis

3.4. Cross-Sectional Dependence Test

3.5. Slope Homogeneity Test

3.6. Panel Unit Root Test

3.7. Panel Cointegration Test

3.8. Pooled Mean Group (PMG-ARDL) Results

3.9. Robustness Check

3.10. Dumitrescu Hurlin (DH) Panel Causality Tests

4. Empirical Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Cross Sectional Dependence Test

| Breusch-Pagan LM | Pesaran scaled LM | Bias-corrected scaled LM | Pesaran CD | |

| All sample-LLc | ||||

| lnTCO2 | 776.236 (0.000) *** | 68.767 (0.000) *** | 68.595 (0.000) *** | 21.246 (0.000) *** |

| lnROFT | 735.059 (0.000) *** | 64.841 (0.000) *** | 64.669 (0.000) *** | 24.921 (0.000) *** |

| lnRAFT | 435.153 (0.000) *** | 36.246 (0.000) *** | 36.074 (0.000) *** | 6.876 (0.000) *** |

| lnFD | 370.518 (0.000) *** | 30.083 (0.000) *** | 29.911 (0.000) *** | 11.440 (0.000) *** |

| lnGDP | 1542.792 (0.000) *** | 141.855 (0.000) *** | 141.683 (0.000) *** | 39.187 (0.000) *** |

| lnIND | 1085.402 (0.000) *** | 98.244 (0.000) *** | 98.073 (0.000) *** | 31.677 (0.000) *** |

| lnEC | 650.825 (0.000) *** | 56.809 (0.000) *** | 56.637 (0.000) *** | 10.302 (0.000) *** |

| lnTOP | 917.698 (0.000) *** | 82.255 (0.000) *** | 82.083 (0.000) *** | 28.152 (0.000) *** |

| lnRE | 461.787 (0.000) *** | 38.785 (0.000) *** | 38.613 (0.000) *** | 15.105 (0.000) *** |

| European-LLc | ||||

| lnTCO2 | 476.746 (0.000) *** | 70.323 (0.000) *** | 70.213 (0.000) *** | 21.753 (0.000) *** |

| lnROFT | 269.915 (0.000) *** | 38.408 (0.000) *** | 38.299 (0.000) *** | 14.507 (0.000) *** |

| lnRAFT | 197.594 (0.000) *** | 27.249 (0.000) *** | 27.139 (0.000) *** | 2.525 (0.011) ** |

| lnFD | 102.947 (0.000) *** | 12.644 (0.000) *** | 12.535 (0.000) *** | 4.072 (0.000) *** |

| lnGDP | 629.852 (0.000) *** | 93.947 (0.000) *** | 93.838 (0.000) *** | 25.081 (0.000) *** |

| lnIND | 387.646 (0.000) *** | 56.574 (0.000) *** | 56.465 (0.000) *** | 18.605 (0.000) *** |

| lnEC | 293.971 (0.000) *** | 42.120 (0.000) *** | 42.011 (0.000) *** | 15.467 (0.000) *** |

| lnTOP | 343.282 (0.000) *** | 49.729 (0.000) *** | 49.619 (0.000) *** | 16.981 (0.000) *** |

| lnRE | 412.020 (0.000) *** | 60.335 (0.000) *** | 60.226 (0.000) *** | 19.988 (0.000) *** |

| Asian-LLc | ||||

| lnTCO2 | 34.127 (0.000) *** | 8.119 (0.000) *** | 8.057 (0.000) *** | 0.645 (0.518) |

| lnROFT | 69.731 (0.000) *** | 18.397 (0.000) *** | 18.335 (0.000) *** | 7.984 (0.000) *** |

| lnRAFT | 26.741 (0.000) *** | 5.987 (0.000) *** | 5.925 (0.000) *** | 1.517 (0.129) |

| lnFD | 49.639 (0.000) *** | 12.597 (0.000) *** | 12.535 (0.000) *** | 6.676 (0.000) *** |

| lnGDP | 160.542 (0.000) *** | 44.612 (0.000) *** | 44.550 (0.000) *** | 12.643 (0.000) *** |

| lnIND | 147.389 (0.000) *** | 40.815 (0.000) *** | 40.753 (0.000) *** | 12.117 (0.000) *** |

| lnEC | 49.186 (0.000) *** | 12.466 (0.000) *** | 12.404 (0.000) *** | -1.154(0.248) |

| lnTOP | 116.111 (0.000) *** | 31.786 (0.000) *** | 31.723 (0.000) *** | 10.600 (0.000) *** |

| lnRE | 24.201 (0.000) *** | 5.254 (0.000) *** | 5.191 (0.000) *** | -1.097(0.272) |

4.3. Slope Homogeneity Test

4.4. Panel Unit Root Test

4.5. Panel Cointegration Test

4.6. PMG-ARDL Results

4.7. Robustness Check

4.8. Dumitrescu Hurlin (DH) Panel Causality Tests

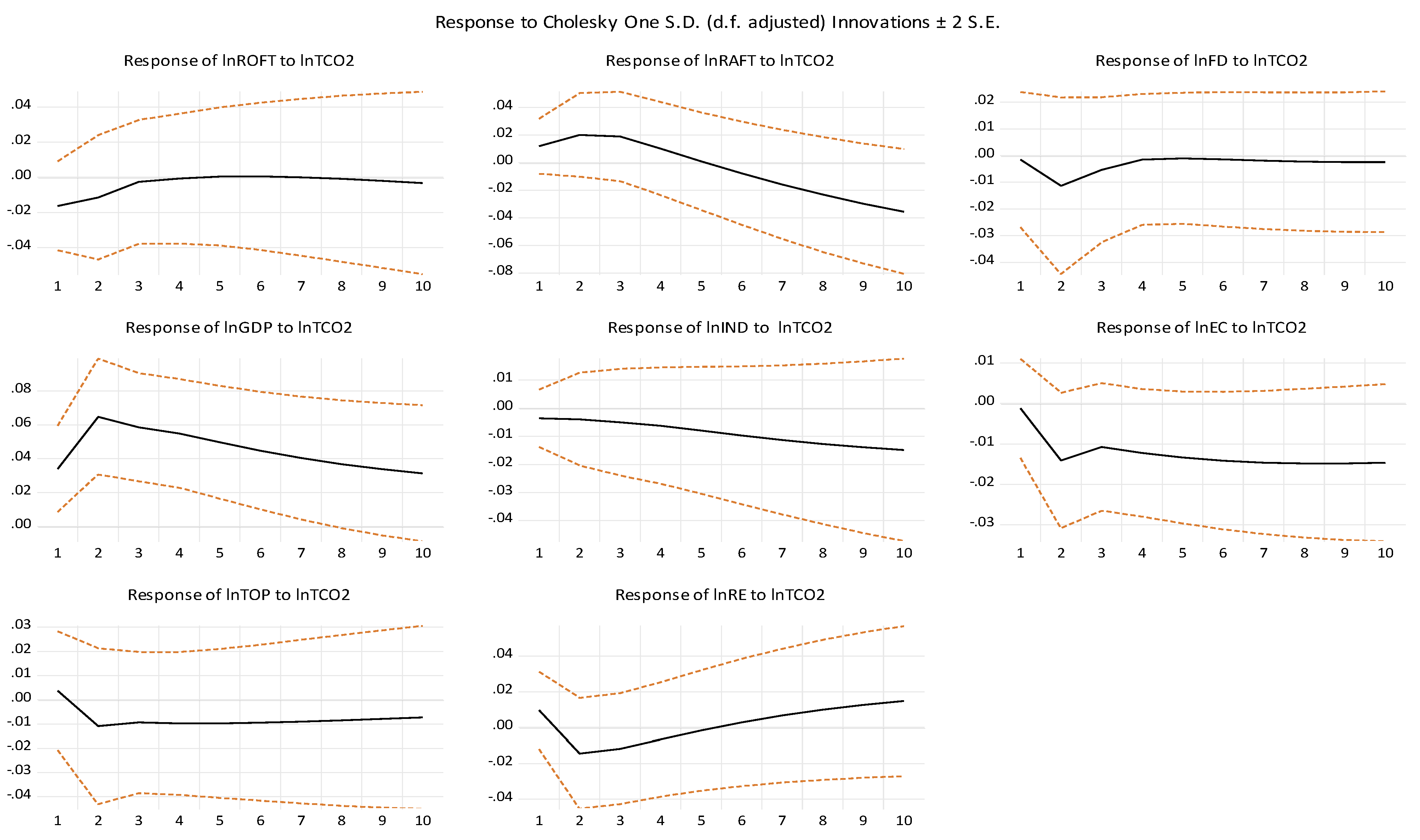

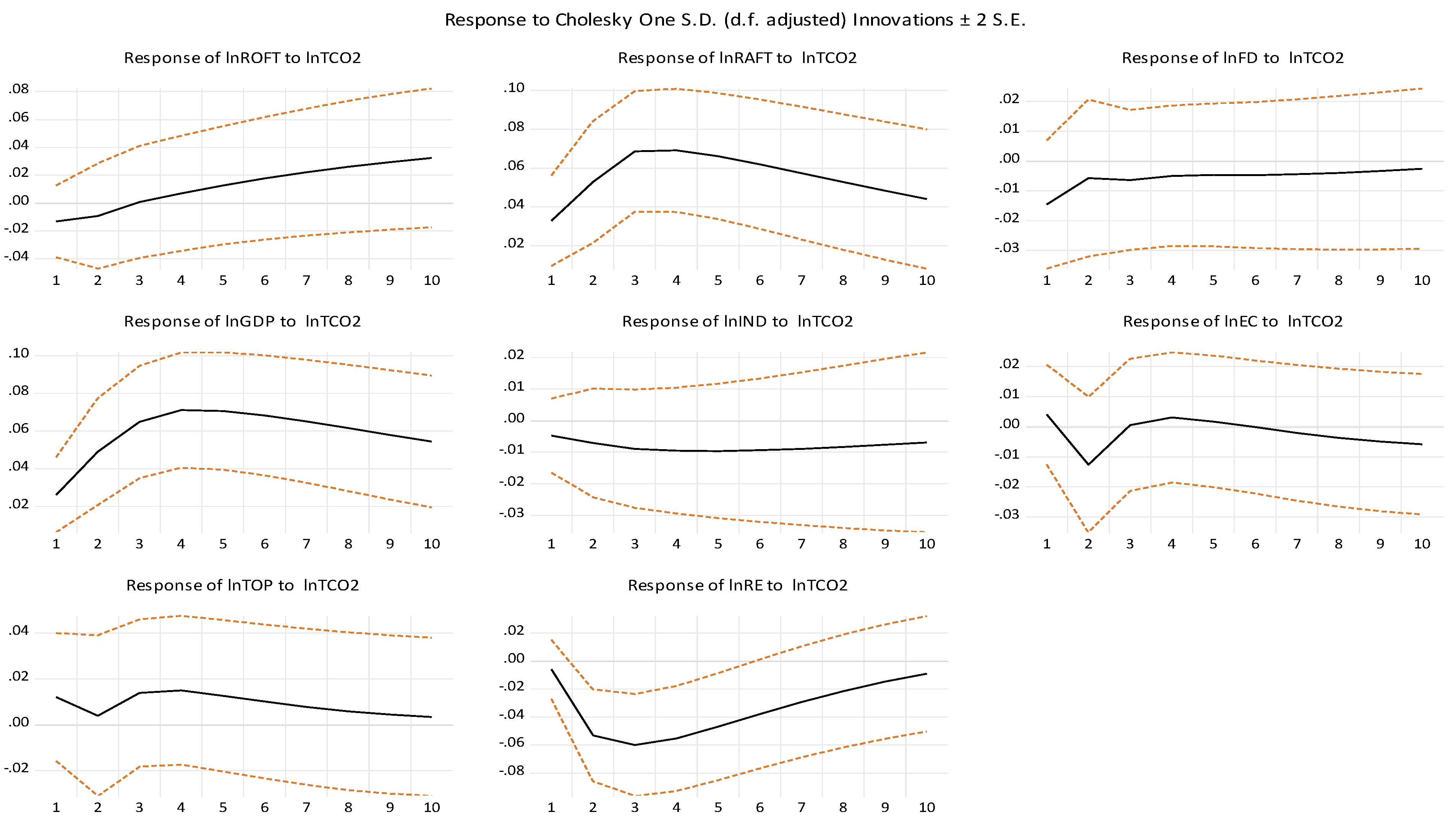

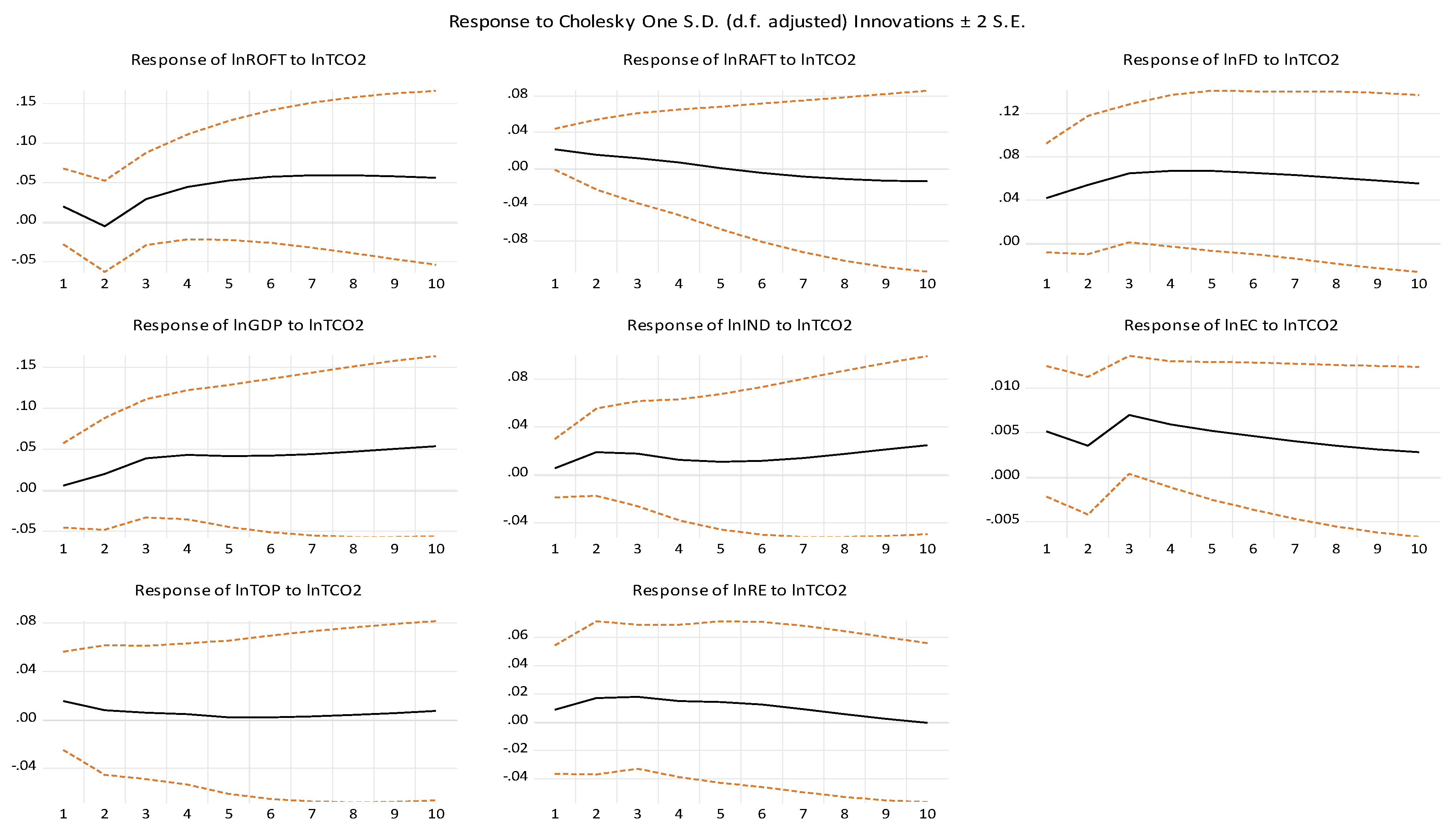

4.9. Dynamic Impact Analysis

5. Conclusion and Policy Implications

References

- Fan, W.; Hao, Y. An empirical research on the relationship amongst renewable energy consumption, economic growth and foreign direct investment in China. Renewable energy 2020, 146, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, G.R.; Shrestha, A. Transport sector CO2 emissions growth in Asia: Underlying factors and policy options. Energy policy 2009, 37, 4523–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryam, J.; Mittal, A.; Sharma, V. (2017). CO2 emissions, energy consumption and economic growth in BRICS: an empirical analysis. [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.; Davíðsdóttir, B. An appraisal of interlinkages between macro-economic indicators of economic well-being and the sustainable development goals. Ecological Economics 2021, 184, 106996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.F. (2020). How Could Trade Measures Being Considered to Mitigate Climate Change Affect LDC Exports?. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 9419.

- Nnene, O.A.; Senshaw, D.; Zuidgeest, M.; Mwaura, O.; Yitayih, Y. Developing Low-Carbon Pathways for the Transport Sector in Ethiopia. Climate 2025, 13, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofélia de Queiroz, F.A.; Morte, I.B. B.; Borges, C.L.; Morgado, C.R.; de Medeiros, J.L. Beyond clean and affordable transition pathways: A review of issues and strategies to sustainable energy supply. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2024, 155, 109544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathaniel, S.; Nwodo, O.; Adediran, A.; Sharma, G.; Shah, M.; Adeleye, N. Ecological footprint, urbanization, and energy consumption in South Africa: including the excluded. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019, 26, 27168–27179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Shah, N.; Sharif, A. Time frequency relationship between energy consumption, economic growth and environmental degradation in the United States: Evidence from transportation sector. Energy 2019, 173, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, I.; Faizulayev, A.; Bekun, F.V. Exploring the role of conventional energy consumption on environmental quality in Brazil: Evidence from cointegration and conditional causality. Gondwana Research 2021, 98, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Destek, M.A. (2019). Financial development and environmental degradation in emerging economies. Energy and environmental strategies in the era of globalization, 115-132. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Ahmed, Z.; Yang, X.; Hussain, N.; Sinha, A. Financial development and environmental degradation: do human capital and institutional quality make a difference? Gondwana Research 2022, 105, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloch, M.A.; Zhang, J.; Iqbal, K.; Iqbal, Z. The effect of financial development on ecological footprint in BRI countries: evidence from panel data estimation. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2019, 26, 6199–6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mulali, U.; Sab, C.N.B.C. The impact of energy consumption and CO2 emission on the economic growth and financial development in the Sub Saharan African countries. Energy 2012, 39, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy-Haksevenler, B.H.; Atasoy-Aytis, E.; Dilaver, M.; Yalcinkaya, S.; Findik-Cinar, N.; Kucuk, E. ...& Yetis, U. A strategy for the implementation of water-quality-based discharge limits for the regulation of hazardous substances. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 24706–24720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidyarthi, H. An econometric study of energy consumption, carbon emissions and economic growth in South Asia: 1972-2009. World Journal of Science, technology and sustainable Development 2014, 11, 182–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, K.; Salim, R. Population ageing, income growth and CO2 emission: empirical evidence from high income OECD countries. Journal of Economic Studies 2015, 42, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Zhao, Y.; Shahbaz, M.; Bano, S.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y. Carbon emissions, energy consumption and economic growth: An aggregate and disaggregate analysis of the Indian economy. Energy Policy 2016, 96, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.S.; Tiwari, S.; Ferraz, D.; Shahzadi, I. Assessing the EKC hypothesis by considering the supply chain disruption and greener energy: findings in the lens of sustainable development goals. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 18168–18180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bölük, G.; Mert, M. Fossil & renewable energy consumption, GHGs (greenhouse gases) and economic growth: Evidence from a panel of EU (European Union) countries. Energy 2014, 74, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebli, M.B.; Youssef, S.B.; Ozturk, I. Testing environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: The role of renewable and non-renewable energy consumption and trade in OECD countries. Ecological indicators 2016, 60, 824–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, F.; Koçak, E.; Bulut, Ü. The dynamic impact of renewable energy consumption on CO2 emissions: a revisited Environmental Kuznets Curve approach. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 54, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoundi, Z. CO2 emissions, renewable energy, and the Environmental Kuznets Curve, a panel cointegration approach. Renewable Energy 2018, 129, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Xie, N.; Fang, D.; Zhang, X. The role of renewable energy consumption and commercial services trade in carbon dioxide reduction: Evidence from 25 developing countries. Applied energy 2018, 211, 1229–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, A.; Raza, S.A.; Ozturk, I.; Afshan, S. The dynamic relationship of renewable and nonrenewable energy consumption with carbon emission: a global study with the application of heterogeneous panel estimations. Renewable energy 2019, 133, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A.; Rashid, M.; Voumik, L.C.; Akter, S.; Esquivias, M.A. The dynamic impacts of economic growth, financial globalization, fossil fuel, renewable energy, and urbanization on load capacity factor in Mexico. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Pham, T.L. H.; Sun, K.; Wang, B.; Bui, Q.; Hashemizadeh, A. The moderating role of financial development in the renewable energy consumption-CO2 emissions linkage: the case study of Next-11 countries. Energy 2022, 254, 124386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshed, M.; Rashid, S.; Ulucak, R.; Dagar, V.; Rehman, A.; Alvarado, R.; Nathaniel, S.P. (2022). Mitigating energy production-based carbon dioxide emissions in Argentina: the roles of renewable energy and economic globalization. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, A.; Mehr, F.; Mao, G.; Yu, Y.; Sápi, A. (2023). The carbon neutrality feasibility of worldwide and in China's transportation sector by E-car. [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Hao, Y. An empirical research on the relationship amongst renewable energy consumption, economic growth and foreign direct investment in China. Renewable energy 2020, 146, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Li, C. (2013, June). An empirical research on trade liberalization and CO2 emissions in China. In International Conference on Education Technology and Information System (ICETIS 2013) (pp. 243–246). [CrossRef]

- Akın, C.S. The impact of foreign trade, energy consumption and income on CO2 emissions. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy 2014, 4, 465–475. [Google Scholar]

- Hakimi, A.; Hamdi, H. Trade liberalization, FDI inflows, environmental quality and economic growth: a comparative analysis between Tunisia and Morocco. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 58, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, T.Y.; Ab-Rahim, R.; Mohd-Kamal, K.A. Trade openness and environmental degradation in asean-5 countries. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2020, 10, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutabba, M.A. The impact of financial development, income, energy and trade on carbon emissions: evidence from the Indian economy. Economic Modelling 2014, 40, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranpanawa, A. (2011). Does Trade Openness Promote Carbon Emissions? Empirical Evidence from Sri Lanka. In The Empirical Economics Letters (Vol. 10, Issue 10) [Journal-article].

- Ertugrul, H.M.; Cetin, M.; Seker, F.; Dogan, E. The impact of trade openness on global carbon dioxide emissions: Evidence from the top ten emitters among developing countries. Ecological Indicators 2016, 67, 543–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Turkekul, B. CO 2 emissions, real output, energy consumption, trade, urbanization and financial development: testing the EKC hypothesis for the USA. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamil, A.M.; Furqan, M.; Mahmood, H. Trade openness and CO2 emissions nexus in Oman. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues 2019, 7, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.M.; Saidi, K.; Mbarek, M.B. (2020b). Economic growth in South Asia: the role of CO2 emissions, population density and trade openness. Heliyon, 6(5). [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Nataliia, D.; Yoo, S.J.; Hwang, Y.S. Does trade openness convey a positive impact for the environmental quality? Evidence from a panel of CIS countries. Eurasian Geography and Economics 2019, 60, 333–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W.; Mahmood, H.; Zakaria, M. Impact of trade openness on environment in China. Journal of Business Economics and Management 2020, 21, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, S.; Klobodu, E.K.M. Financial development, control of corruption and CO2 emissions: Evidence from African countries. Energy Economics 2017, 63, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, H.; Belloumi, M. Investigating the causal relationship between transport infrastructure, transport energy consumption and economic growth in Tunisia. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2016, 56, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, S.A.; Marques, A.C.; Fuinhas, J.A. Is energy consumption in the transport sector hampering both economic growth and the reduction of CO2 emissions? A disaggregated energy consumption analysis. Transport policy 2017, 59, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wu, N.; Wu, K. Energy consumption and energy efficiency of the transportation sector in Shanghai. Sustainability 2014, 6, 702–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtishaw, S.; Schipper, L. Disaggregated analysis of US energy consumption in the 1990s: evidence of the effects of the internet and rapid economic growth. Energy Policy 2001, 29, 1335–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, C.; Grant-Muller, S.; Gale, W.F. Approaches and techniques for modelling CO2 emissions from road transport. Transport Reviews 2015, 35, 533–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, S.; Hammami, S. Modeling the causal linkages between transport, economic growth and environmental degradation for 75 countries. Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 2017, 53, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, M.; Azam, A.; Rafiq, M.; Luo, X. Evaluating the relationship between freight transport, economic prosperity, urbanization, and CO2 emissions: Evidence from Hong Kong, Singapore, and South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, N.; Chaim, O.; Cazarini, E.; Gerolamo, M. Manufacturing in the fourth industrial revolution: A positive prospect in Sustainable Manufacturing. Procedia Manufacturing 2018, 21, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Shackman, J.; Liu, X. Carbon emission flow in the power industry and provincial CO2 emissions: Evidence from cross-provincial secondary energy trading in China. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 159, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Ali, H.; Abdelfattah, Y.M.; Adams, J. (2016, April). Population dynamics and carbon emissions in the arab region: An extended stirpat II model. In Economic Research Forum Working Papers (Vol. 988).

- Rafiq, S.; Salim, R.; Apergis, N. Agriculture, trade openness and emissions: an empirical analysis and policy options. Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 2016, 60, 348–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejat, P.; Jomehzadeh, F.; Taheri, M.M.; Gohari, M.; Majid, M.Z. A. A global review of energy consumption, CO2 emissions and policy in the residential sector (with an overview of the top ten CO2 emitting countries). Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 2015, 43, 843–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Chang, M.; Shi, F.; Tanikawa, H. How does industrial structure change impact carbon dioxide emissions? A comparative analysis focusing on nine provincial regions in China. Environmental Science & Policy 2014, 37, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, R.A.; Shafiei, S. Urbanization and renewable and non-renewable energy consumption in OECD countries: An empirical analysis. Economic Modelling 2014, 38, 581–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniwchan, J. Economic growth, industrialization, and the environment. Resource and Energy Economics 2012, 34, 442–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Uddin, G.S.; Rehman, I.U.; Imran, K. Industrialization, electricity consumption and CO2 emissions in Bangladesh. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 31, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asumadu-Sarkodie, S.; Owusu, P.A. Energy use, carbon dioxide emissions, GDP, industrialization, financial development, and population, a causal nexus in Sri Lanka: With a subsequent prediction of energy use using neural network. Energy Sources, Part B: Economics, Planning, and Policy 2016, 11, 889–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asumadu-Sarkodie, S.; Owusu, P. (2017). Carbon dioxide emissions, GDP per capita, industrialization and population: An evidence from Rwanda. Environmental engineering research, 22(1). [CrossRef]

- Appiah, K.; Du, J.; Yeboah, M.; Appiah, R. Causal relationship between industrialization, energy intensity, economic growth and carbon dioxide emissions: recent evidence from Uganda. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy 2019, 9, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, N.; Elfaki, K.E. Examining the Relationship Between Energy Consumption, Economic Growth and Environmental Degradation in Indonesia: Do Capital and Trade Openness Matter? . International Journal of Renewable Energy Development 2021, 10, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahi, Z.; Hashemi, M.S.; Bameri, S.; Mohamad Taghvaee, V. Environmental pollution, economic growth, population, industrialization, and technology in weak and strong sustainability: using STIRPAT model. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2020, 22, 1105–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). (2024). Les émissions de carbone du secteur de l'énergie.

- Pesaran, M.H.; Ullah, A.; Yamagata, T. A bias-adjusted LM test of error cross-section independence. The Econometrics Journal 2008, 11, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H. (2007), A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross-section dependence. Journal of Applied Econometrics 22, 265-312. [CrossRef]

- Swamy, P.A. (1970). Efficient inference in a random coefficient regression model. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 311-323. [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. (2004), Panel cointegration: A symptotic and finite sample properties of pooled time series tests with an application to the PPP hypothesis. Economic Theory 20, 597-625. [CrossRef]

- Kao, C. Spurious regression and residual-based tests for cointegration in panel data. Journal of econometrics 1999, 90, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroni, P. (2001). Fully modified OLS for heterogeneous cointegrated panels. In Nonstationary panels, panel cointegration, and dynamic panels (pp. 93–130). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [CrossRef]

- Mark, N.C.; Sul, D. Nominal exchange rates and monetary fundamentals: evidence from a small post-Bretton Woods panel. Journal of international economics 2001, 53, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez, I.C.; Barbero, J.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Zofío, J.L. Does institutional quality matter for trade? Institutional conditions in a sectoral trade framework. World Development 2018, 103, 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, E.I.; Hurlin, C. Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Economic modelling 2012, 29, 1450–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Ullah, A.; Yamagata, T. (2008), A bias-adjusted LM test of error cross-section independence. The Econometrics Journal, 11, 105-127. [CrossRef]

- Zhen You, Lei Li b, Muhammad Waqas (2024). How do information and communication technology, human capital and renewable energy affect CO2 emission; New insights from BRI countries. 10, e26-481. [CrossRef]

- Hasanov, F.J.; Mukhtarov, S.; Suleymanov, E. The role of renewable energy and total factor productivity in reducing CO2 emissions in Azerbaijan. Fresh insights from a new theoretical framework coupled with Autometrics. Energy Strategy Reviews 2023, 47, 101079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, L.; Weber, S. Testing for Granger causality in panel data. The Stata Journal 2017, 17, 972–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, H.U. R.; Siddique, M.; Zaman, K.; Yousaf, S.U.; Shoukry, A.M.; Gani, S. . & Saleem, H. The impact of air transportation, railways transportation, and port container traffic on energy demand, customs duty, and economic growth: Evidence from a panel of low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Journal of Air Transport Management 2018, 70, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinnon, A. (2018). Decarbonizing Logistics: Distributing Goods in a Low Carbon World. Kogan Page Publishers.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). (2021). Transport – Analysis. IEA, Paris.

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Transport emissions of greenhouse gases. EEA, Copenhagen.

- Arbolino, R.; Carlucci, F.; De Simone, L.; Ioppolo, G.; Yigitcanlar, T. (2018). The policy diffusion of environmental performance in the European countries. Ecological Indicators 2019, 89, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćosović; E; Mihajlović; I; SpasojevićBrkić, V. (2024). IMPACT OF FUEL CONSUMPTION ON CO2 EMISSIONS IN ROAD TRANSPORT IN EUROPEAN COUNTRIES. In Proceedings of the XIV International Conference-Industrial Engineering and Environmental Protection (IIZS 2024) (pp. 380–387). Zrenjanin: Technical Faculty" Mihajlo Pupin". [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.C.; Sabur, H.M. A.; Saif, T.M. R. Environmental sustainability of inland freight transportation Systems in Bangladesh. International Supply Chain Technology Journal 2023, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbi, M.F.; Abdullah, M. Fossil fuel CO2 emissions and economic growth in the Visegrád region: A study based on the environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis. Climate 2024, 12, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holappa, L. A general vision for reduction of energy consumption and CO2 emissions from the steel industry. Metals 2020, 10, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, R.; Feng, S.; Lauvaux, T. Country-scale trends in air pollution and fossil fuel CO2 emissions during 2001–2018: confronting the roles of national policies and economic growth. Environmental Research Letters 2020, 16, 014006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, N. (2024). Assessing the impact of feed-in tariffs and renewable portfolio standards on the development of solar photovoltaic in Vietnam–opportunities and challenges.

- Hariyani, H.F.; Prasetyo, D.G.; Van Ha, T.T.; Dam, B.H.; Nguyen, T.T. H. Unlocking CO2 emissions in East Asia Pacific-5 countries: Exploring the dynamics relationships among economic growth, foreign direct investment, trade openness, financial development and energy consumption. Journal of Infrastructure Policy and Development 2024, 8, 5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrullah, N.; Husnain, M.I. U.; Khan, M.A. The dynamic impact of renewable energy consumption, trade, and financial development on carbon emissions in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 56759–56773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definitions | Measurements | Sources |

| TCO2 | Transport-related carbon dioxide emissions | % of total fuel combustion | IEA (2024)[65] |

| ROFT | road freight transports | millions of metric tons times kilometers traveled | WDI(2024) |

| RAFT | Rail freight transports | millions of metric tons times kilometers traveled | WDI(2024) |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product | Current US$ | WDI(2024) |

| IND | Industry (including construction) | Current US$ | WDI(2024) |

| EC | Fossil fuel energy consumption | % of total energy consumption | WDI(2024) |

| TOP | Trade openness: Total trade in goods and services | Million US dollars | WDI(2024) |

| RE | Renewable energy consumption | % of total final energy consumption | WDI(2024) |

| FD | Financial development | Domestic credit to private sector (% of GDP) | WDI(2024) |

| lnTCO2 | lnROFT | lnRAFT | lnFD | lnGDP | lnIND | lnEC | lnTOP | lnRE | |

| All sample-LLc | |||||||||

| Mean | 2.869 | 9.495 | 9.436 | 3.677 | 8.914 | 21.652 | 5.040 | 11.302 | 1.835 |

| Maximum | 4.224 | 12.115 | 12.648 | 5.194 | 11.803 | 25.988 | 11.833 | 14.105 | 3.951 |

| Minimum | 1.537 | 4.889 | 5.948 | 0.009 | 4.098 | 2.641 | 3.840 | 8.315 | -0.328 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.729 | 1.393 | 1.407 | 1.021 | 1.590 | 6.333 | 1.950 | 1.392 | 1.185 |

| Skewness | -0.008 | -0.924 | 0.249 | -0.901 | -0.065 | -2.515 | 2.657 | -0.157 | 0.001 |

| Kurtosis | 1.910 | 4.034 | 3.497 | 3.650 | 2.231 | 7.662 | 8.246 | 2.218 | 1.699 |

| Jarque-Bera | 16.384 | 61.949 | 6.840 | 50.627 | 8.385 | 648.806 | 769.191 | 9.781 | 23.326 23.326 |

| European-LLc | |||||||||

| Mean | 3.158 | 9.651 | 9.227 | 4.117 | 9.599 | 21.018 | 5.233 | 2.433 | 11.929 |

| Maximum | 4.232 | 11.460 | 11.230 | 5.227 | 11.803 | 26.122 | 11.833 | 3.951 | 14.105 14.105 |

| Minimum | 1.548 | 5.624 | 5.948 | 1.360 | 6.387 | 2.641 | 3.808 | -0.083 | 8.315 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.624 | 1.087 | 0.909 | 0.749 | 1.359 | 7.472 | 2.310 | 0.931 | 1.216 |

| Skewness | -0.231 | -1.304 | -0.662 | -1.135 | -0.265 | -1.949 | 2.045 | -0.520 | -0.759 |

| Kurtosis | 2.333 | 5.268 | 4.510 | 4.233 | 2.071 | 4.972 | 5.287 | 2.457 | 3.533 |

| Jarque-Bera | 6.329 | 114.989 | 38.841 | 64.322 | 10.999 | 183.834 | 211.394 | 13.283 13.283 | 24.925 24.925 |

| Asian-LLC | |||||||||

| Mean | 2.333 333 |

8.814 | 9.375 | 2.778 | 7.499 | 23.005 | 4.512 | 10.063 | 0.938 |

| Maximum | 3.626 | 12.115 | 12.648 | 4.369 | 9.538 | 25.070 | 4.612 | 11.960 11.960 | 2.876 |

| Minimum | 0.641 | 4.889 | 5.777 | 0.009 | 4.098 | 20.448 | 4.054 | 8.344 | -0.328 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.668 | 2.105 | 2.204 | 0.893 | 1.120 | 1.216 | 0.142 | 0.978 | 0.772 |

| Skewness | 0.201 | -0.352 | -0.027 | -0.734 | -0.118 | -0.259 | -1.515 | 0.143 | 0.815 |

| Kurtosis | 2.394 | 2.096 | 1.877 | 3.755 | 2.328 | 2.150 | 3.692 | 1.874 | 2.366 |

| Jarque-Bera | 2.905 | 7.219 | 6.946 | 15.013 | 2.783 | 5.450 | 53.183 | 7.419 | 16.847 16.847 |

| All sample-LLc | Europeean-LLc | Asian-LLc | ||||

| Statistics | T-statistics | P-value | T-statistics | P-value | T-statistics | P-value |

| 12.255 | 0.0001*** | 17.698 | 0.0000*** | 12.084 | 0.0000*** | |

| 18.053 | 0.000*** | 12.292 | 0.0005*** | 16.115 | 0.0000*** | |

| CIPS |

CADF |

|||

| Level | 1st Difference | Level | 1st Difference | |

| All Sample | ||||

| lnTCO2 | -2.273** | -5.774*** | -1.564 | -4.431*** |

| lnGDP | -3.476*** | -5.254*** | -2.557*** | -3.986*** |

| lnRAFT | -1.908 | -5.317*** | -1.935 | -4.101*** |

| lnROFT | -1.816 | -5.337*** | -1.454 | -4.059*** |

| lnFD | -1.788 | -5.175*** | -1.992 | -3.752*** |

| lnIND | -1.798 | -4.312*** | -2.402** | -3.647*** |

| lnTOP | -1.794 | -5.167*** | -1.687 | -4.230*** |

| lnEC | -1.371 | -5.276*** | -1.201 | -3.767*** |

| lnRE | -1.973 | -4.989*** | -2.110 | -3.326*** |

| Europe | ||||

| lnTCO2 | -3.269*** | -5.776*** | -2.469** | -4.315*** |

| lnGDP | -4.193*** | -5.933*** | -1.912 | -4.404*** |

| lnRAFT | -1,747 | -5.018*** | -1.742 | -3.717*** |

| lnROFT | -1.934 | -5.946*** | -2.228 | -4.133*** |

| lnFD | -1.640 | -5.053*** | -1.630 | -3.806*** |

| lnIND | -0.812 | -5.151*** | -1.067 | -4.322*** |

| lnTOP | -1.515 | -5.284*** | -1.651 | -3.478*** |

| lnEC | -2.077 | -5,365*** | -1.822 | -4.130*** |

| lnRE | -2.032 | -5.320*** | -1.536 | -4.119*** |

| Asia | ||||

| lnTCO2 | -2.856*** | -5.442*** | -2.131 | -4.589*** |

| lnGDP | -2.062 | -4.970*** | -2.229 | -4.223*** |

| lnRAFT | -1.832 | -5.696*** | -2.839** | -4.662*** |

| lnROFT | -1.913 | -5.539*** | -1.865 | -4.589*** |

| lnFD | -1.946 | -5.485*** | -2.766** | -4.172*** |

| lnIND | -1.742 | -4.845*** | -2.391* | -3.576*** |

| lnTOP | -1.896 | -5.454*** | -2.087 | -4.252*** |

| lnEC | -2.237* | -6.072*** | -1.690 | -4.757*** |

| lnRE | -2.551** | -5.272*** | -2.562** | -4.280*** |

| All sample-LLc | European-LLc | Asian-LLc | |||||

| Pedroni Residual Cointegration Test | |||||||

| Alternative hypothesis: common AR coefs. (within-dimension) | |||||||

| Statistic | P-value | Statistic | P-value | Statistic | P-value | ||

| Panel v-Statistic | -2.244 | 0.987 | -0.300 | 0.618 | -1.857 | 0.968 | |

| Panel rho-Statistic | 2.480 | 0.993 | 1.182 | 0.881 | 1.826 | 0.966 | |

| Panel PP-Statistic | -0.751 | 0.226 | -2.482 | 0.006*** | 0.321 | 0.626 | |

| Panel ADF-Statistic | -1.004 | 0.157 | -3.543 | 0.000*** | 0.537 | 0.704 | |

| Alternative hypothesis: individual AR coefs. (between-dimension) | |||||||

| Panel rho-Statistic | 2.983 | 0.998 | 2.054 | 0.980 | 2.229 | 0.987 | |

| Panel PP-Statistic | -2.265 | 0.011** | -2.165 | 0.015** | -0.892 | 0.186 | |

| Panel ADF-Statistic | -0.033 | 0.486 | -0.785 | 0.216 | 0.983 | 0.837 | |

| Kao Residual Cointegration Test | |||||||

| t-Statistic | Prob | t-Statistic | Prob | t-Statistic | Prob | ||

| ADF | -1.267 | 0.102 | -3.190 | 0.000*** | -4.745 | 0.000*** | |

| All-sample-LLc | European-LLc | Asian-LLc | ||||

| Variables | Coef | p-value | Coef | p-value | Coef | p-value |

| Long run analysis | ||||||

| lnROFT | 0.053 | 0.568 | 0.874 | 0.000*** | 0.251 | 0.000*** |

| lnRAFT | -0.690 | 0.000*** | 0.017 | 0.658 | -0.806 | 0.000*** |

| lnFD | 0.650 | 0.000*** | -1.204 | 0.000*** | 0.535 | 0.000*** |

| lnGDP | 0.720 | 0.000*** | -0.355 | 0.000*** | 0.318 | 0.000*** |

| lnIND | -1.104 | 0.000*** | 1.327 | 0.000*** | -0.525 | 0.000*** |

| lnEC | -3.362 | 0.000*** | 0.303 | 0.318 | 12.595 | 0.000*** |

| lnTOP | -0.394 | 0.001*** | -0.208 | 0.000*** | 0.074 | 0.468 |

| lnRE | 0.176 | 0.129 | 0.368 | 0.000*** | 0.512 | 0.000*** |

| Short run analysis | ||||||

| Coint Eq (-1) | -0.108 | (0.053) ** | -0.121 | 0.024** | -0.410 | 0.025** |

| D (lnROFT) | 0.012 | (0.889) | -0.168 | 0.396 | -0.042 | 0.631 |

| D (lnRAFT) | 0.032 | (0.574) | -0.049 | 0.504 | 0.147 | 0.590 |

| D (lnFD) | -0.213 | (0.293) | 0.594 | 0.443 | 0.298 | 0.469 |

| D (lnGDP) | 0.037 | (0.368) | 0.030 | 0.661 | -0.276 | 0.014** |

| D (lnIND) | 0.062 | (0.635) | -0.062 | 0.712 | -0.125 | 0.675 |

| D (lnEC) | -0.303 | (0.579) | 0.071 | 0.908 | -6.755 | 0.273 |

| D (lnTOP) | 0.078 | (0.012) ** | -0.180 | 0.417 | -0.016 | 0.896 |

| D (lnRE) | 0.054 | (0.423) | 0.166 | 0.268 | -0.037 | 0.663 |

| C | 4.871 | (0.057) ** | -3.352 | 0.265 | -17.395 | 0.025* |

| All-Sample-LLc | European-LLc | Asian-LLc | ||||

| Variables | Coefficient | Coefficient | Coefficient | |||

| Fully Modified Ordinary Least Square (FMOLS) | ||||||

| Ln TCO2 Ln ROFT Ln RAFT Ln FD Ln GDP Ln IND Ln EC Ln TOP Ln RE |

- -0.019 (0.000)*** -0.243 (0.000)*** -0.202 (0.000)*** 0.382 (0.000)*** 0.066 (0.000)*** 0.119 (0.000)*** 0.030 (0.000)*** 0.098 (0.000)*** |

- 3.95E-05 (0.997) 0.027 (0,099)* -0.248 (0.000)*** 0.544 (0.000)*** -0.081 (0.000)*** -0.157 (0.000)*** 0.080 (0.000)*** 0.023 (0.000)*** |

- 0.164 (0.000)*** 0.154 (0.005)*** 0.171 (0.003)*** 0.293 (0.000)*** -0.305 (0.000)*** -0.473 (0.000)*** -0.249 (0.000)*** -0.419 (0.000)*** |

|||

| Dynamic Ordinary Least Square (DOLS) | ||||||

| Ln TCO2 Ln ROFT Ln RAFT Ln FD Ln GDP Ln IND Ln EC Ln TOP Ln RE |

- -0.665 (0.000)*** 1.319 (0.000)*** 2.059 (0.000)*** 0.848 (0.000)*** -0.218 (0.594) 0.423 (0.032)** 0.203(0.112) -2.070 (0.000)*** |

- -0.014 (0.764) 0.135 (0.006)*** -0.326 (0.003)*** 0.527 (0.000)*** -0.086 (0.001)*** -0.195 (0.003)*** 0.086 (0.107) 0.048 (0.429) |

- 0.391 (0.001)*** -0.252 (0.004)*** 0.255 (0.011)* 0.518 (0.000)*** -1.296 (0.000)*** 5.145 (0.000)*** 0.306 (0.025)* 0.289 (0.351) |

|||

| All sample-LLc | European-LLc | Asian-LLc | |||||||

| Null Hypothesis | W-stat | Zbar-stat | Probability | W-stat | Zbar-stat | Probability | W-stat | Zbar-stat | Probability |

| lnRAFT≠lnTCO2 | 5.231 | 2.075 | 0.037** | 17.468 | 3.410 | 0.000*** | 46.386 | 7.159 | 8.E-13*** |

| lnTCO2≠lnRAFT | 7.207 | 4.208 | 3.E-05*** | 25.300 | 6.407 | 1.E-10*** | 26.934 | 5.316 | 1.E-07*** |

| lnROFT≠lnTCO2 | 4.483 | 1.273 | 0.203 | 11.966 | 3.749 | 0.000*** | 24.519 | 2.776 | 0.005*** |

| lnTCO2≠lnROFT | 8.981 | 6.139 | 8.E-10*** | 15.924 | 2.819 | 0.004*** | 10.175 | -0.098 | 0.921 |

| lnFD ≠lnTCO2 | 8.405 | 5.543 | 3.E-08*** | 3.508 | 4.006 | 6.E-05*** | 92.597 | 16.422 | 0.000*** |

| lnTCO2 ≠lnFD | 4.920 | 1.758 | 0.0786* | 3.932 | 4.705 | 3.E-06*** | 34.068 | 4.690 | 3.E-06*** |

| lnGDP ≠lnTCO2 | 6.923 | 3.934 | 8.E-05*** | 4.780 | 2.936 | 0.003*** | 13.145 | 0.496 | 0.619 |

| lnTCO2 ≠lnGDP | 4.853 | 1.686 | 0.0917* | 4.536 | 2.662 | 0.007*** | 9.236 | -0.286 | 0.774 |

| lnIND ≠lnTCO2 | 9.886 | 6.939 | 4.E-12*** | 3.273 | 3.620 | 0.000*** | 23.052 | 10.099 | 0.000*** |

| lnTCO2 ≠lnIND | 6.256 | 3.098 | 0.001*** | 3.858 | 4.582 | 5.E-06*** | 9.759 | 2.884 | 0.003*** |

| lnEC ≠lnTCO2 | 2.568 | 3.062 | 0.002*** | 1.599 | -0.637 | 0.523 | 53.231 | 8.531 | 0.000*** |

| lnTCO2 ≠lnEC | 0.955 | -0.248 | 0.803 | 4.465 | 2.582 | 0.009** | 35.371 | 4.951 | 7.E-07*** |

| lnTOP ≠lnTCO2 | 3.847 | 0.455 | 0.648 | 16.776 | 0.191 | 0.847 | 7.075 | -0.719 | 0.471 |

| lnTCO2 ≠lnTOP | 2.984 | -0.394 | 0.693 | 41.008 | 2.809 | 0.005*** | 15.945 | 1.058 | 0.290 |

| lnRE ≠lnTCO2 | 2.456 | 2.828 | 0.004*** | 24.182 | 3.584 | 0.000*** | 34.954 | 4.868 | 1.E-06*** |

| lnTCO2 ≠lnRE | 2.033 | 1.959 | 0.050** | 27.921 | 4.575 | 5.E-06*** | 15.446 | 0.958 | 0.338 |

|

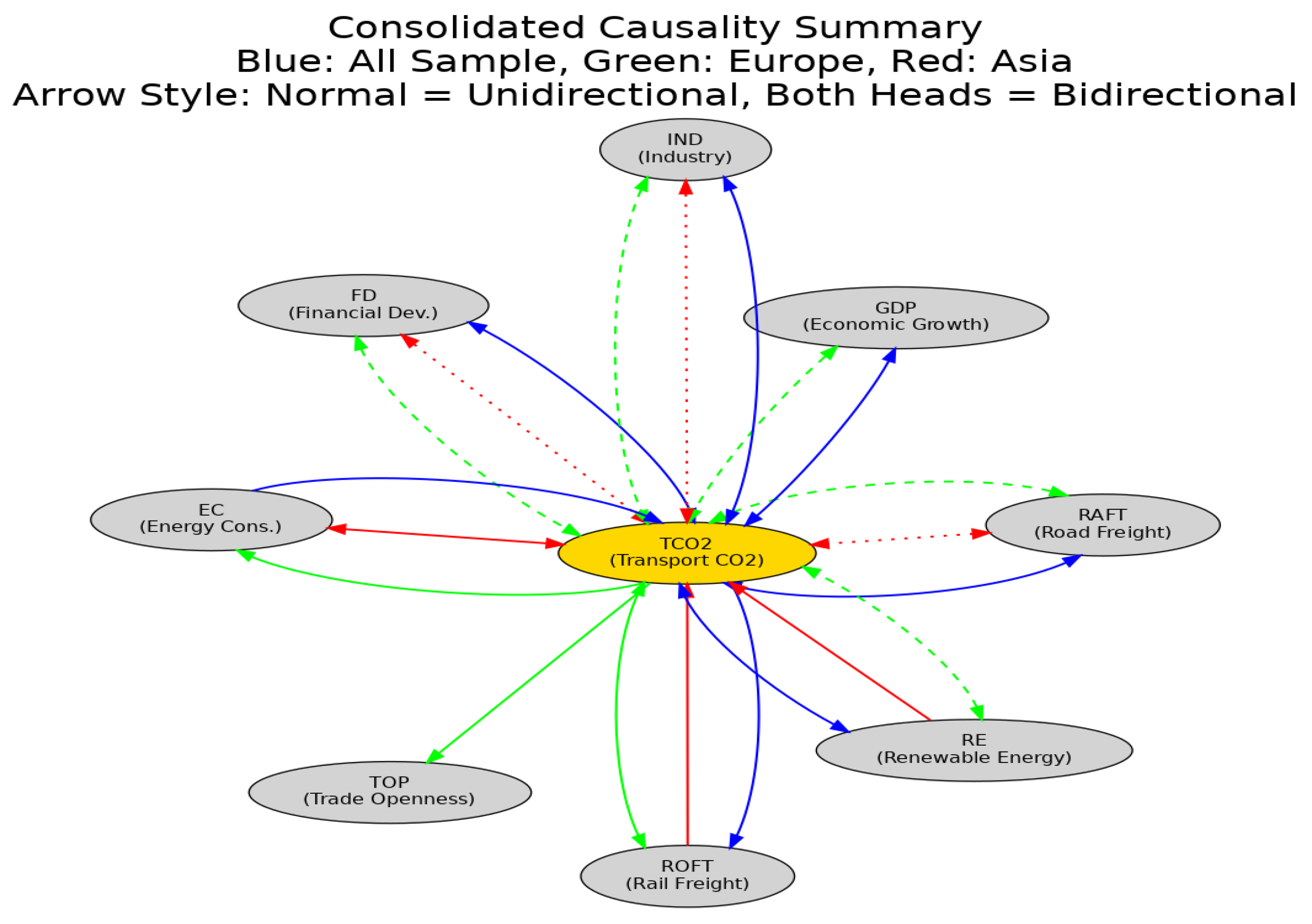

Summary of causalites : All sample-LLc : RAFT↔ TCO2 ; TCO2 → ROFT ; FD ↔ TCO2 ; GDP ↔ TCO2 ; IND ↔ TCO2 ; EC → TCO2 ; TCO2 ↔ RE European-LLc : ROFT ↔ TCO2 ; RAFT ↔ TCO2 ; FD ↔ TCO2 ; GDP ↔ TCO2 ; IND ↔ TCO2 ; TCO2 → EC ; TCO2→TOP ; RE ↔ TCO2 Asian-LLc : RAFT↔TCO2 ; ROFT→ TCO2 ; FD ↔ TCO2 ; IND ↔ TCO2 ; EC ↔ TCO2 ; RE → TCO2 Note: ***,** and * shows statistical significant at 1%, 5% and 10% level respectively, → indicate unidirectional causality, ↔ indicate bidirectional causality and ≠ denotes that A does not homogeneously cause B. | |||||||||

| Period | S.E. | lnTCO2 | lnROFT | lnRAFT | lnFD | lnGDP | lnIND | lnEC | lnTOP | lnRE |

| All sample-LLc | ||||||||||

| 2023 | 0.101506 | 100.0000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| 2028 | 0.193542 | 96.70943 | 1.040579 | 0.348878 | 0.724071 | 0.174985 | 0.324044 | 0.011983 | 0.173929 | 0.492103 |

| 2033 | 0.251320 | 90.17627 | 1.196186 | 3.684687 | 1.324250 | 0.209753 | 0.426638 | 0.047857 | 0.994332 | 1.940026 |

| European-LLc | ||||||||||

| 2023 | 0.081614 | 100.0000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| 2028 | 0.164400 | 90.58908 | 4.520048 | 1.497820 | 0.089900 | 0.942239 | 1.426338 | 0.853628 | 0.017232 | 0.063720 |

| 2033 | 0.205835 | 84.92786 | 7.788997 | 1.408449 | 0.108510 | 1.238609 | 1.994292 | 2.019309 | 0.436806 | 0.077166 |

| Asian-LLc | ||||||||||

| 2023 | 0.226549 | 100.0000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 | 0.000000 |

| 2028 | 0.461080 | 74.87811 | 1.930243 | 9.988028 | 2.024419 | 3.634298 | 1.518210 | 0.992425 | 0.047586 | 4.986683 |

| 2033 | 0.549368 | 60.92547 | 1.783830 | 13.62304 | 6.345661 | 7.957332 | 1.651150 | 3.163423 | 0.250552 | 4.299539 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).