1. Introduction

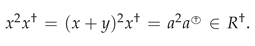

An associative ring with an identity 1 is called a *-ring if there exists an involution

satisfying

for all

. An element

has group inverse provided that there exists

such that

Such

x is unique if exists, denoted by

, and called the group inverse of

a. As is well known, a square complex matrix

A has group inverse if and only if

(see [

13]). An element

has core inverse if there exists some

such that

If such

x exists, it is unique, and denote it by

. Let

represent the range space of a complex matrix

X. A square complex matrix

A has core inverse

if and only if

is a projection and

(see [

3,

16]). Group and core inverses are extensively studied by many authors from very different points of view, e.g., [

1,

3,

7,

10,

13,

16].

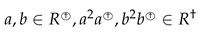

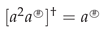

An element

has Moore-Penrose inverse if there exists

such that

The preceding

x is unique if it exists, and we denote it by

. The set of all Moore-Penrose invertible elements in

R is denoted by

. Evidently, every square complex matrix has the Moore-Penrose inverse. In [

2], Baksalary and Trenkler extended core inverse and introduced a generalized core inverse. Recently, Ferreyra and Malik studied such generalized core inverse and call it the introduced BT inverse for a complex matrix. The matrix

is called the BT inverse of

A. Many elementary properties of this new generalized inverse are established in [

5]. For additional references on the BT inverse, we refer the reader to [

6,

8,

9,

17].

The motivation of this paper is to extend the proposed generalized inverse for complex matrices to a more general setting within a ring. We introduce the BT inverse for an element in a ring R. Furthermore, we establish and prove several fundamental properties of the BT inverse within this ring.

In

Section 2, we introduce a new generalized inverse as the generalization of BT inverse of a complex matrix.

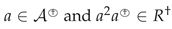

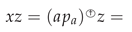

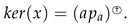

Definition 1.

An element has BT inverse if there exists such that

If such x exists, it is unique, and denote it by . The set of all BT invertible elements in R is denoted by .

In [

15], based on the Hartwig-Spindelbock decomposition of a complex matrix, Wang characterize the BT inverse of a complex matrix by using the system by equations. Replacing the Hartwig-Spindelbock decomposition, we employ the Pierce representation of a ring element as a tool to extend the characterization of BT inverse of a complex matrix to a broader context within a ring. We prove that

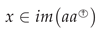

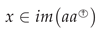

has BT inverse if and only if

. In this case,

. In

Section 3, we investigate the order relation induced by BT inverse. Many characterizations of the BT order are obtained by using Pierce decomposition for a ring element.

Let

be a Banach algebra. Evidently,

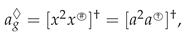

Definition 2.

An element has generalized BT inverse if there exist such that

We denote by and call it the generalized BT inverse of a. The set of all generalized BT invertible elements in is denoted by .

Recall that an element

has generalized Moore-Penrose inverse if there exists

such that

The preceding

x is denoted by

. The set of all generalized Moore-Penrose invertible elements in

R is denoted by

.

In

Section 4, we prove that

if and only if

. We further characterize the generalized BT inverse by using the system of equations.

Finally, in

Section 5, we present certain characterizations of the generalized BT inverse for a geometrical point of view.

Throughout the paper, all rings are associative *-rings with an identity.

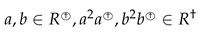

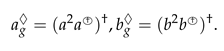

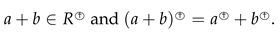

and

denote the sets of all group invertible, More-Penrose invertible and generalized Moore-Penrose invertible elements in

R, respectively. Let

. Set

and

. Let

. Then

. We use

to denote the projection

p such that

and

.

2. BT Inverse

The purpose of this section is to investigate the elementary properties of the BT inverse, which will be frequently utilized in subsequent sections. Our starting point is as follows.

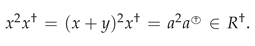

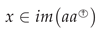

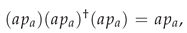

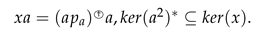

Theorem 1. Let . Then the following are equivalent:

- (1)

.

- (2)

.

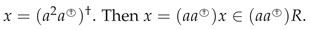

In this case, .

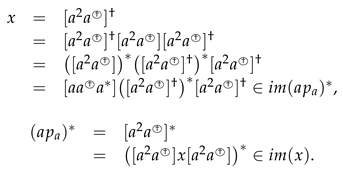

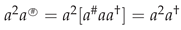

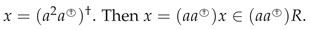

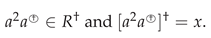

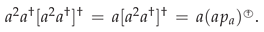

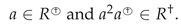

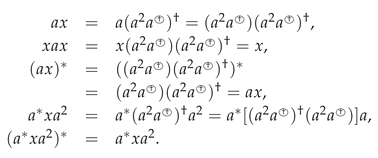

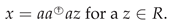

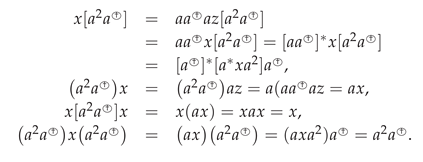

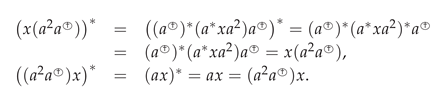

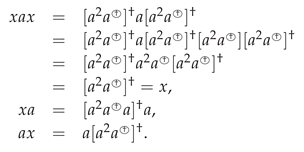

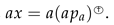

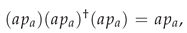

Proof. By hypothesis, there exists

such that

Write

for a

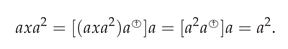

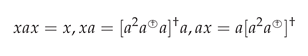

. We directly verify that

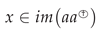

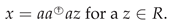

Therefore and . This implies that x is unique, as required.

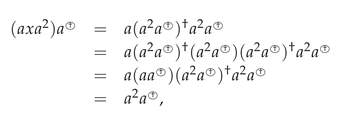

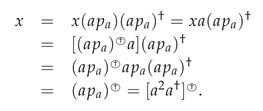

Let

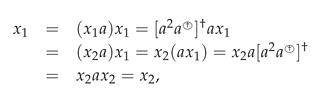

Then

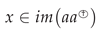

Therefore

is the solution of the system of equations:

as required. □

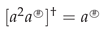

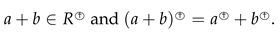

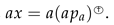

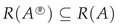

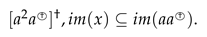

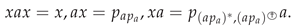

Corollary 1. Let  . Then and

. Then and  .

.

Proof. In view of [

16, Theorem 2.6],

.

Then we have

. It is easy to verify that

Then

This implies that

. In this case,

. □

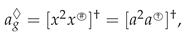

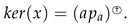

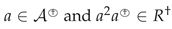

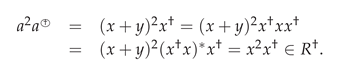

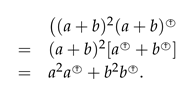

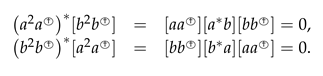

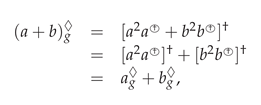

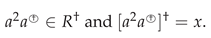

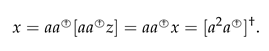

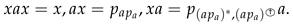

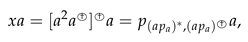

Let

and

. Then we have

Lemma 1. Let . Then and

Proof. It is easy to verify that

Thus, .

In light of Theorem 2.1, we derive that

as asserted. □

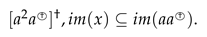

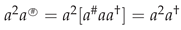

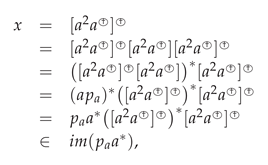

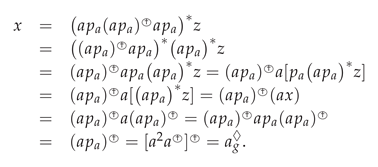

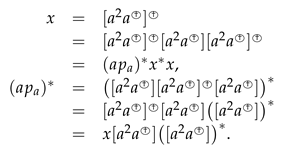

We come now to establish the representation of the BT inverse by using certain projections.

Theorem 2. Let . Then

Proof. By virtue of Lemma 2.3,

. Further, we verify that

Furthermore, we check that

Therefore □

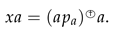

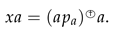

Corollary 2.

Let . The system given by

is consistent and its unique solution is

Proof. Clearly, we have In view of Theorem 2.4, Hence, . We infer that

Suppose that

for some

. As

, we write

for some

. Then

as required. □

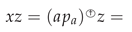

Theorem 3.

Let . The system given by

is consistent and its unique solution is

Proof.

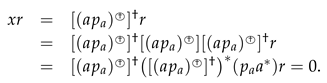

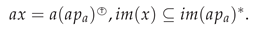

Suppose that for . Then ; hence, . Therefore , as asserted. □

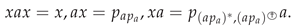

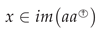

Let

. An element

a has

-inverse provide that there exists

such that

If such

x exists, it is unique and denote it by

(see [

4]).

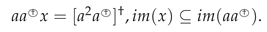

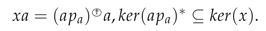

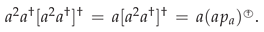

Theorem 4. Let . Then

Proof. Obviously,

. Let

. We verify that

Therefore as asserted. □

Let and . We say that a has -inverse x provided that . We denote x by . We next consider the relation between the BT inverse and -inverse in a ring. .

Theorem 5. Let . Then

Proof. Let . Clearly, we have .

Step 1.

. In view of Theorem 2.1, we have

Hence, . Therefore .

Step 2.

. If

for some

, then

Hence, .

Thus, , as required.

Therefore we complete the proof. □

3. BT Order

This section is devoted to the BT order for two elements is a ring. Let and .

Definition 3. We say that if and only if

Let

. Then we have

Moreover, we compute that

Theorem 6. Let . Then the following are equivalent:

- (1)

.

- (2)

There exist

such that

a and

b are represented by

where

.

Proof. Since

, we see that

Write

. Then

Hence, .

Since

, we directly verify that

Therefore , as desired. □

Corollary 3. Let and . Then the following are equivalent:

- (1)

.

- (2)

There exists

such that

a and

b are represented by

where

.

- (3)

Proof. This is obvious by Theorem 3.2.

By hypothesis, we have

; hence,

. This implies that

. Since

we verify that

as desired.

Write

. By hypothesis, we have

This implies that

and then

Since , we deduce that . This implies that , and so .

Hence

and so

Therefore , as required. □

Corollary 4. Let and . Then the following are equivalent:

- (1)

.

- (2)

.

- (3)

.

Proof. In view of Corollary 3.3,

where

. Thus,

, as required.

In view of Theorem 3.2,

. Set

. Then

, and so

By using Corollary 3.3, .

By hypothesis, we have

Hence, Thus , as required.

Since and , we derive that as desired. □

We are ready to prove:

Theorem 7. Let and . If then .

Proof. In view of Theorem 3.2, we have

where

. Since

, we see that

This implies that .

In view of Lemma 2.3,

Therefore

By hypothesis, we compute that

Accordingly, . □

Corollary 5. Let and . If if and only if .

Proof. ⟸ Since

, as in the proof in Theorem 3.5, we deduce that

hence,

. This implies that

It follows that

. Thus

. Since

, we have

; whence,

. Thus

. Accordingly,

, as required.

⟸ This is proved in Theorem 3.5. □

4. Generalized BT Inverse

The aim of this section is to introduce the notion of the generalized BT inverse in a ring. For further use, we formally establish the following lemma:

Lemma 2. Let . Then the following are equivalent:

- (1)

.

- (2)

There exist

such that

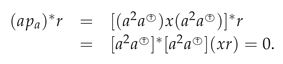

Proof. By hypotheses, there exists

such that

Set

and

Then

. We claim that

x has Moore-Penrose inverse. Evidently, we verify that

Therefore and .

Since

, we have

By hypothesis, we get . Therefore there exists the Moore-Penrose decomposition , as required.

By hypothesis, there exist

such that

Set

. One easily checks that

Moreover, we check that

and then

Then

Since

, we see that

Therefore

, as asserted. □

Theorem 8. Let . Then the following are equivalent:

- (1)

.

- (2)

In this case,

Proof. Since

, there exist

such that

Clearly,

. In light of Lemma 4.1,

and

. It is easy to verify that

Moreover, we check that

as required.

Since

, by virtue of Lemma 4.1, there exist

such that

In this case,

. Moreover, we have

Therefore

. Accordingly,

. □

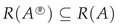

As an immediate consequence, we derive

Corollary 6. Let . Then the following are equivalent:

- (1)

.

- (2)

The system of conditions

is consistent and it has the unique solution.

In this case,

Corollary 7.

Let . If , then . In this case,

Proof. Since

, it follows by Theorem 4.2 that

and

Since

, we verify that

It is easy to verify that

By hypothesis, we verify that

In light of Theorem 4.2,

as asserted. □

We are ready to prove:

Theorem 9. Let . Then if and only if

- (1)

;.

- (2)

there exists

such that

In this case,

Proof. ⟹ Let

We verify that

Furthermore, we have

as required.

⟸ By hypothesis, there exists

such that

Write

Then we check that

Therefore

This completes the proof. □

Corollary 8. Let . Then if and only if . In this case,

Proof. ⟹ This is obvious.

⟸ Since

, we have

. In view of Theorem 4.5, there exists

such that

Therefore . In this case, , as asserted. □

5. Characterizations of the Generalized BT-Inverse

The main purpose of this section is to provide new properties of the generalized BT-inverse in a ring. Consider the system given by

Lemma 3. If the system of equations has a solution, then it is unique.

Proof. Assume that

satisfy

. Then

for

. Therefore

as desired. □

Theorem 10. Let . Then the following are equivalent:

- (1)

.

- (2)

The system of equations is consistent and it has the unique solution x.

Proof. Taking

In view of Theorem 4.2,

Then

By virtue of Lemma 5.1, x is the unique solution of the preceding equations, as required.

By the argument above, we have

Therefore

by Theorem 4.2. □

We are ready to prove:

Theorem 11. Let . Then the following are equivalent:

- (1)

.

- (2)

- (3)

- (4)

- (5)

Proof. In view of Theorem 5.2,

We verify that

as required.

Write

for a

. Then

as required.

In view of Theorem 4.2,

Then we easily check that

Write

for a

. Then

By virtue of Theorem Theorem 4.2, , as desired.

Obviously,

If

, then

. Hence,

Thus

. That is,

, as desired.

We directly verify that , as required.

As

we get

. Hence,

. Since

, we have

. Therefore

Therefore we complete the proof by Theorem 4.2. □

Corollary 9. Let . Then the following are equivalent:

- (1)

.

- (2)

Proof. In view of Theorem 5.1,

. Moreover, we have

It is easy to verify that

Hence,

. Obviously,

. Thus, we have

as required.

By hypothesis,

Then

Moreover, we have

According to Theorem 5.3, we complete the proof. □

Theorem 12. Let . Then

Proof. Set . In view of Theorem 5.2, we have .

Step 1.

. In view of Theorem 4.2, we have

Accordingly, we have .

Step 2.

. If

for some

, then

Thus .

Thus, . As a result, we have .

Therefore By the similar way, we check that This completes the proof. □

References

- O.M. Baksalary and G. Trenkler, Core inverse of matrices, Linear Multilinear Algebra, 58(2010), 681–697. [CrossRef]

- O.M. Baksalary and G. Trenkler, On a generalized core inverse, Applied Math. Comput., 236(2014), 450–457. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen; H. Zhu; P. Patricio and Y. Zhang, Characterizations and representations of core and dual core inverses, Canad. Math. Bull., 2016. [CrossRef]

- M.P. Drazin, A class of outer generalized inverses, Linear Multilinear Algebra, 436 (2012), 1909–1923. [CrossRef]

- D.E. Ferreyra and S.B. Malik, The BT inverse, In book: Generalized Inverses: Algoritms and Applications, Publisher: Nova Science Publishers, 2021.

- D.E. Ferreyra; N. Thome and C. Torigino, The W-weighted BT inverse, Quest. Math., 46(2023), 359–374. [CrossRef]

- T. Li and J. Chen, Characterizations of core and dual core inverses in rings with involution, Linear Multilinear Algebra, 66(2018), 717–730. [CrossRef]

- W, Jiang and K. Zuo, Revisiting of the BT-inverse of matrices, AIMS Math., 6(2021), 2607–2622. [CrossRef]

- A. Kara; N. Thome and D.S. Djordjević, Simultaneous extension of generalized BT-inverses and core-EP inverses, Filomat, 38(2024), 10605–10614.

- N. Mihajlovic, Group inverse and core inverse in Banach and C*-algebras, Comm. Algebra, 48(2020), 1803–1818. [CrossRef]

- D. Mosić, Weighted generalized Moore-Penrose inverse, Georgian Math. J., 30(2023), 919–932.

- K.S. Stojanović and D. Mosić, Generalization of the Moore-Penrose inverse, Rev. R. Acad. Cienc. Exactas Fis. Nat., Ser. A Mat., 114(2020), No. 4, Paper No. 196, 16 p.

- D.S Rakic; N.C. Dincic and D.S. Djordjevic, Group, Moore-Penrose, core and dual core inverse in rings with involution, Linear Algebra Appl., 463(2014), 115–133. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, Core-EP Decomposition and its applications, Linear Algebra Appl., 508(2016), 289–300. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, Some new characterizations of generalized inverses, Front. Math., 18(2023), 1397–1402. [CrossRef]

- S. Xu; J. Chen and X. Zhang, New characterizations for core inverses in rings with involution, Front. Math., 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Xu and D. Wang, New characterizations of the generalized B-T inverse, Filomat, 36(2022), 945–950.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

. Let represent the range space of a complex matrix X. A square complex matrix A has core inverse

. Let represent the range space of a complex matrix X. A square complex matrix A has core inverse  if and only if

if and only if  is a projection and

is a projection and  (see [3,16]). Group and core inverses are extensively studied by many authors from very different points of view, e.g., [1,3,7,10,13,16].

(see [3,16]). Group and core inverses are extensively studied by many authors from very different points of view, e.g., [1,3,7,10,13,16]. . The set of all generalized Moore-Penrose invertible elements in R is denoted by

. The set of all generalized Moore-Penrose invertible elements in R is denoted by  .

. . We further characterize the generalized BT inverse by using the system of equations.

. We further characterize the generalized BT inverse by using the system of equations. denote the sets of all group invertible, More-Penrose invertible and generalized Moore-Penrose invertible elements in R, respectively. Let . Set and . Let . Then . We use to denote the projection p such that and .

denote the sets of all group invertible, More-Penrose invertible and generalized Moore-Penrose invertible elements in R, respectively. Let . Set and . Let . Then . We use to denote the projection p such that and . . Then and

. Then and  .

. .

. . It is easy to verify that

. It is easy to verify that

This implies that . In this case,

This implies that . In this case,  . □

. □ .

. , as asserted. □

, as asserted. □

and

and  . It is easy to verify that

. It is easy to verify that

as required.

as required. , by virtue of Lemma 4.1, there exist such that

, by virtue of Lemma 4.1, there exist such that . Moreover, we have

. Moreover, we have  Therefore . Accordingly, . □

Therefore . Accordingly, . □ and

and

It is easy to verify that

It is easy to verify that

;.

;. such that

such that

We verify that

We verify that

such that

such that

Then we check that

Then we check that

This completes the proof. □

This completes the proof. □ . In view of Theorem 4.5, there exists

. In view of Theorem 4.5, there exists  such that

such that

Then

Then

Therefore by Theorem 4.2. □

Therefore by Theorem 4.2. □

We verify that

We verify that

Then we easily check that

Then we easily check that

for a . Then

for a . Then

If , then . Hence,

If , then . Hence,

Thus . That is, , as desired.

Thus . That is, , as desired. we get . Hence, . Since , we have . Therefore

we get . Hence, . Since , we have . Therefore

. Thus, we have

. Thus, we have

Then

Then  Moreover, we have

Moreover, we have  According to Theorem 5.3, we complete the proof. □

According to Theorem 5.3, we complete the proof. □