Introduction

Background

Large Language Models (LLMs) are recognized for their effectiveness in addressing user queries based on information available through training, fine-tuning, or in-context learning. Among the key techniques to enhance their capabilities is “Chain of Thought” (CoT) [

1], also known as “reasoning,” which prompts LLMs to generate intermediate reasoning steps prior to generating final responses. CoT outperforms few-shot prompting with enhanced response accuracy. Another technique is Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [

2], which supplements LLMs with new information through retrievals from external sources. However, recent findings on reasoning reveal an illusion of thinking in LLMs when facing complex tasks [

3].

Literature Review

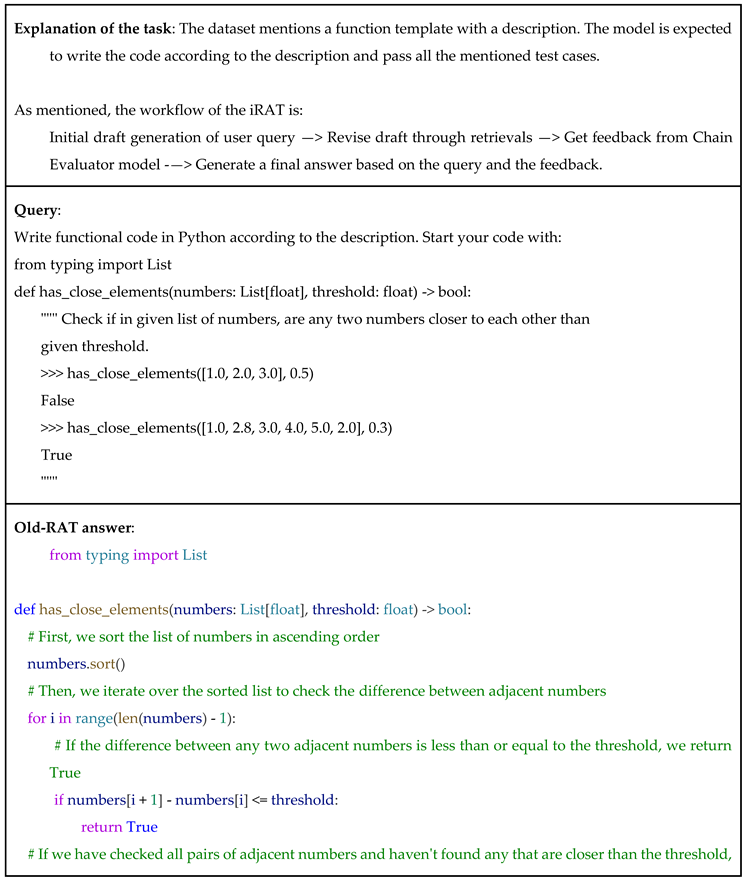

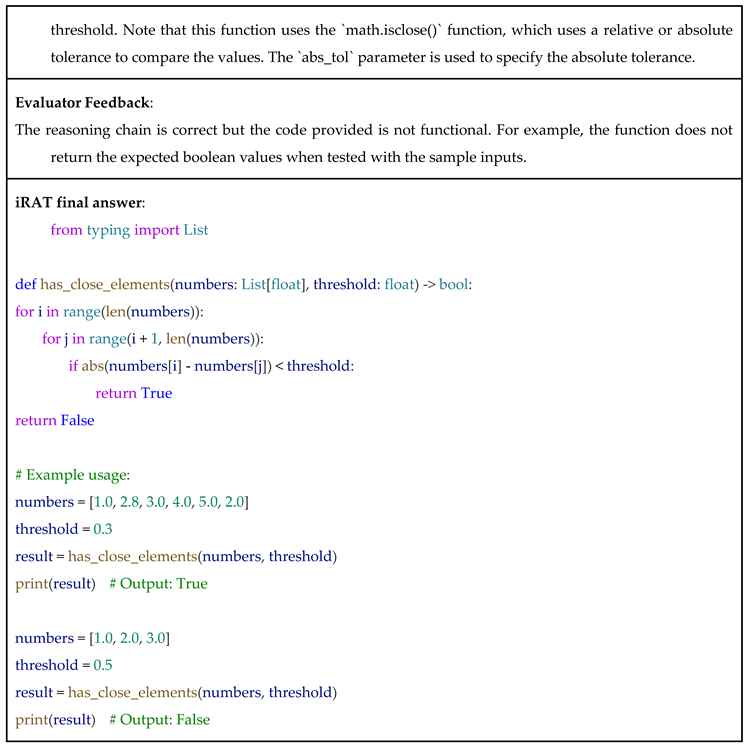

Previous research on Retrieval-Augmented Thoughts (RAT) [

4,

5], referred to as “old-RAT”, utilized CoT combined with RAG, which mitigated hallucinations and incoherent reasoning in the LLMs, increasing response accuracy. Old-RAT generates an initial draft, divides it into reasoning steps, and retrieves external knowledge at each step to iteratively refine the reasoning process. This approach substantially mitigates hallucinations and improves factual grounding. By incorporating retrieval rather than relying solely on the LLM’s knowledge base, old-RAT achieves improved performance across various reasoning tasks. However, old-RAT lacks a mechanism to assess uncertainty, leading to unnecessary retrievals and thoughts, which reduces its efficiency at scale. Furthermore, it fails to optimize reasoning globally and does not employ a model to update previous thoughts when new thoughts contradict them, which implies it lacks end-to-end trajectory optimization.

Self-RAG [

6] introduces a reflective framework where an LLM dynamically decides whether to retrieve, generate, or critique at each step using specialized reflection tokens. This adaptive mechanism improves factual accuracy, enables generalization across different tasks, and maintains low overhead during inference. While effective, the reflection token training process may exhibit instability, and the framework demands significant computational resources during initial training. Additionally, the quality of the generated reflection signals significantly affects the performance and renders the system sensitive to prompt and domain variations. RAG2 [

7] improves factual grounding in the medical domain using a rationale-based approach, where the LLM generates intermediate rationales to guide retrieval queries and filters retrieved results using a perplexity-based scoring model. RAG2 ensures a balanced use of multiple corpora to mitigate source bias and improve reliability. However, the system is limited by its domain specificity, limited filtering capacity (handling one snippet at a time), and elevated pipeline complexity due to additional rationale.

Solution

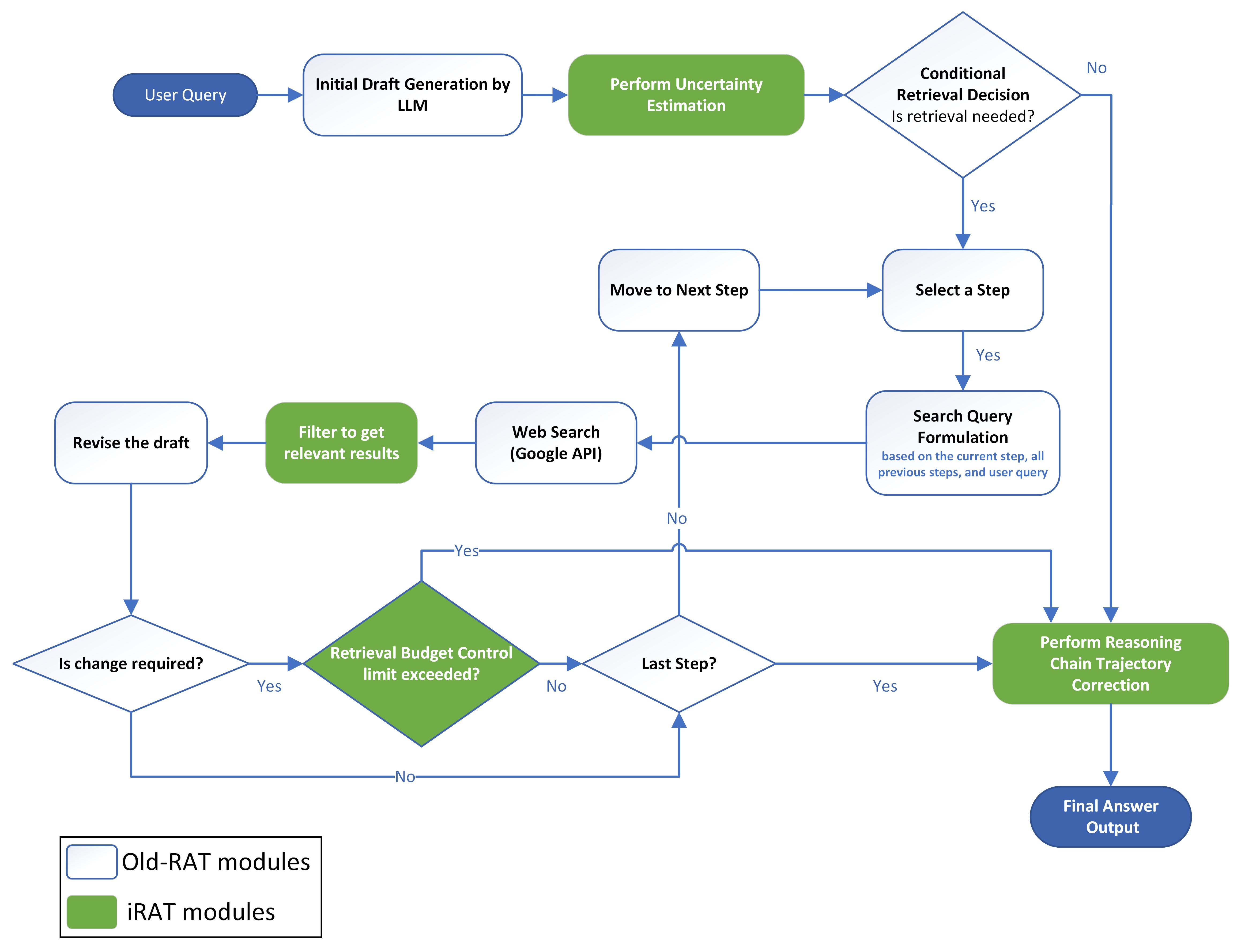

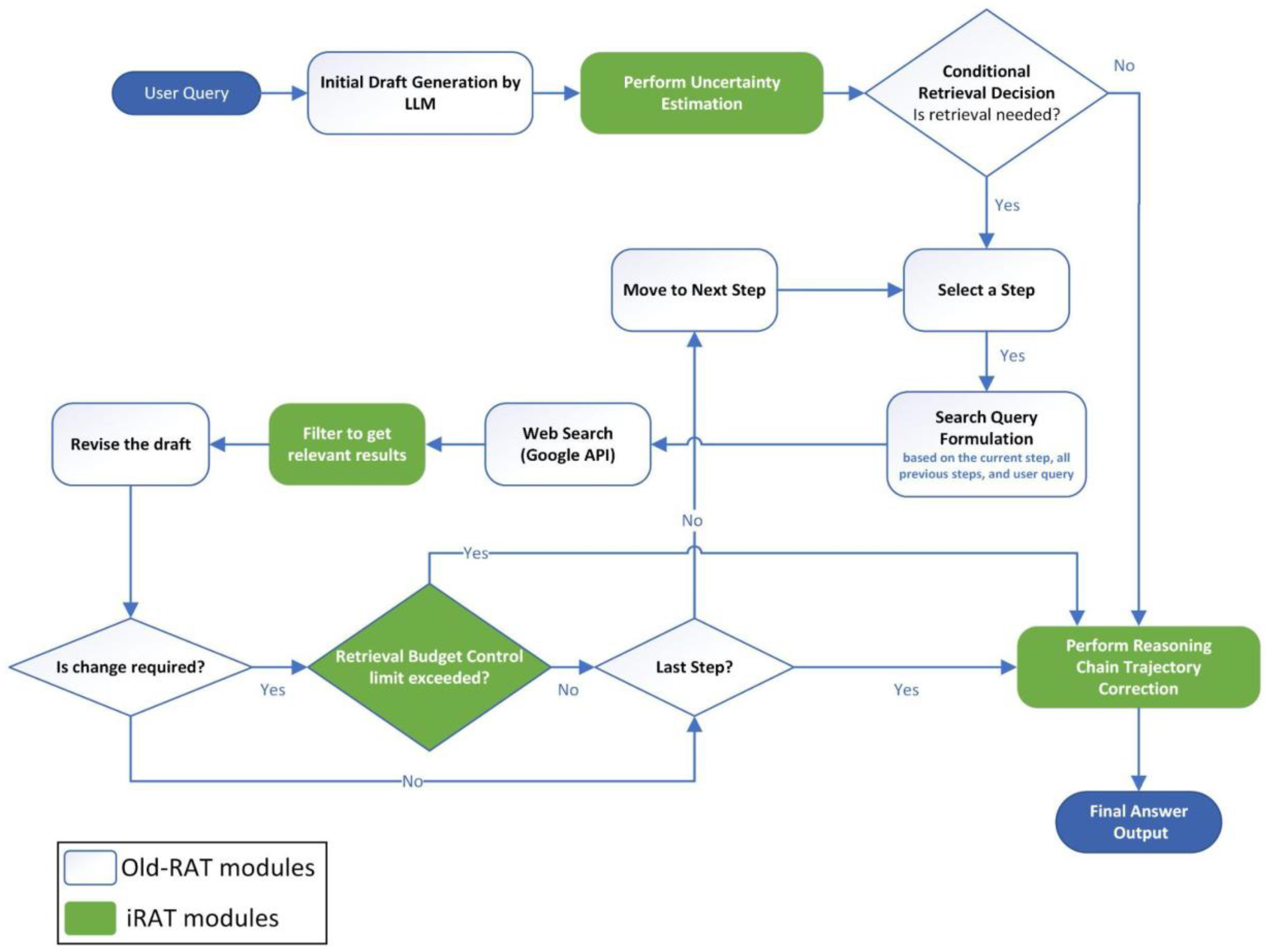

This study introduces iRAT, an enhanced retrieval-augmented reasoning framework derived from old-RAT, and improves reasoning through retrieval control policies and dynamic replanning mechanisms to reduce unnecessary retrievals, filter undesirable results, dynamically correct intermediate reasoning inaccuracies, and adapt inference pipelines for complex, long-horizon tasks. iRAT is designed to be a robust and resource-efficient retrieval-augmented thinking framework capable of adapting to complex tasks, enabling higher accuracy and resource efficiency in real-world applications compared to old-RAT.

Methods

Initial Draft Generation

The first stage in iRAT employs an LLM to generate an initial draft for each query. The system employed an open-source model Llama 3.3 (70B) [

8], which is known for its performance despite its small size. Each query undergoes a validation process to identify and mitigate potentially harmful content, including malicious patterns and unsupported characters.

Uncertainty Estimation

This step measures the model’s confidence in answering a query. The embedding model all-MiniLM-L6-v2 [

9] was selected due to its established performance and small size. This process involves generating three initial responses to the query, encoding drafts into embeddings using the model, and calculating pairwise cosine similarities of the embeddings to measure the consistency of the responses. The average of these pairwise similarity scores represents a self-consistency score, also known as “certainty.” The uncertainty is calculated as 1 - average_consistency .

Retrieval

Retrieval Decision

This module triggers retrieval only when uncertainty exceeds a threshold of 30%. This step enables selective retrieval to maintain accuracy while reducing resource usage when the model’s confidence is high, allowing the optimization of cost and latency.

Retrieval-Based Revision with Budget Control

If retrieval is triggered, a process similar to that of old-RAT is employed to revise the draft in multiple steps. The text is divided into chunks to create multiple steps. At each step, a search query is formulated for the chunk using the selected LLM. The queries are used to fetch paragraphs from the web to update the chunk. Budget control policy is enforced to allow only one retrieval per chunk. While old-RAT generates one chunk per paragraph, iRAT further minimizes retrievals by merging consecutive chunks, subject to a limit of 500 characters per chunk. Budget control is essential because excess retrievals increase computational and financial costs.

The Google Search API is used to retrieve the top 10 most relevant results according to Google. To maintain fairness, URLs containing HumanEval, MBPP, and GSM8K datasets are excluded to ensure the model does not receive solutions from the selected datasets. Unlike old-RAT, the system supports retrievals from websites such as StackOverflow and Stack Exchange pages by utilizing their public API. The system mitigates unsupported URLs, such as YouTube and PDF files, to prevent retrieval errors.

Result Filtering

SEO spamming [

10] in Google’s Search Results may result in irrelevant, low-value, or malicious pages that have the potential to mislead LLMs. Most pages include non-informative elements such as headers and advertisements, potentially interfering with model comprehension. Long content in a web page might lead to information overload, potentially degrading LLM response accuracy and increasing inference costs. Hence, spam URLs are filtered based on the page’s URL and domain using Google Safe Browsing API [

11] and Malicious URLs Dataset [

12]. Paragraphs are extracted from page content, and the new “Attention-Retrieval” method selects relevant paragraphs.

The Attention-Retrieval method employs pre-trained re-ranking models to generate ranks and scores of retrieved paragraphs based on the query. The model ms-marco-MiniLM-L6-v2 [

13] was selected due to its optimal model size and the scores on the official web page [

14]. Top 8 most relevant paragraphs are predicted using the model, and the results are further filtered to select paragraphs above a threshold of 50% of score. Consecutive paragraphs are merged, subject to a limit of 500 characters per paragraph. Similar to old-RAT, the response is revised based on each selected paragraph.

Replanning

To address the challenge of global end-to-end optimization, this module reviews all the steps and generates feedback to enhance previous steps to align the whole chain. This module employs an ensemble of a reward model and DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-1.5B [

15], quantized and fine-tuned using LoRA [

16]. This module mitigates error propagation and reduces contradictions and inaccuracies in prior steps, unlike the old-RAT process. The fine-tuned model used for replanning is available at huggingface.co/zeeshan5k/iRATReasoningChainEvaluatorv2.

Final Evaluation

The system gets evaluated using HumanEval [

17] and MBPP [

18] datasets for coding tasks, and GSM8K [

19] dataset for mathematical reasoning tasks. System evaluation employed the pass@k metric [

20] on HumanEval and MBPP datasets, and the Exact Match (EM) metric [

21] to match the answers on the GSM8K dataset. The pass@k metric measures the model’s code passing all the test cases provided, in the first “k” attempts, while the Exact Match compares the dataset’s answers to the model’s answers. An additional metric that was introduced was the average number of retrievals required to answer a query. This step compares iRAT with old-RAT on the same machine using the same model to enable a fair comparison.

Results and Discussion

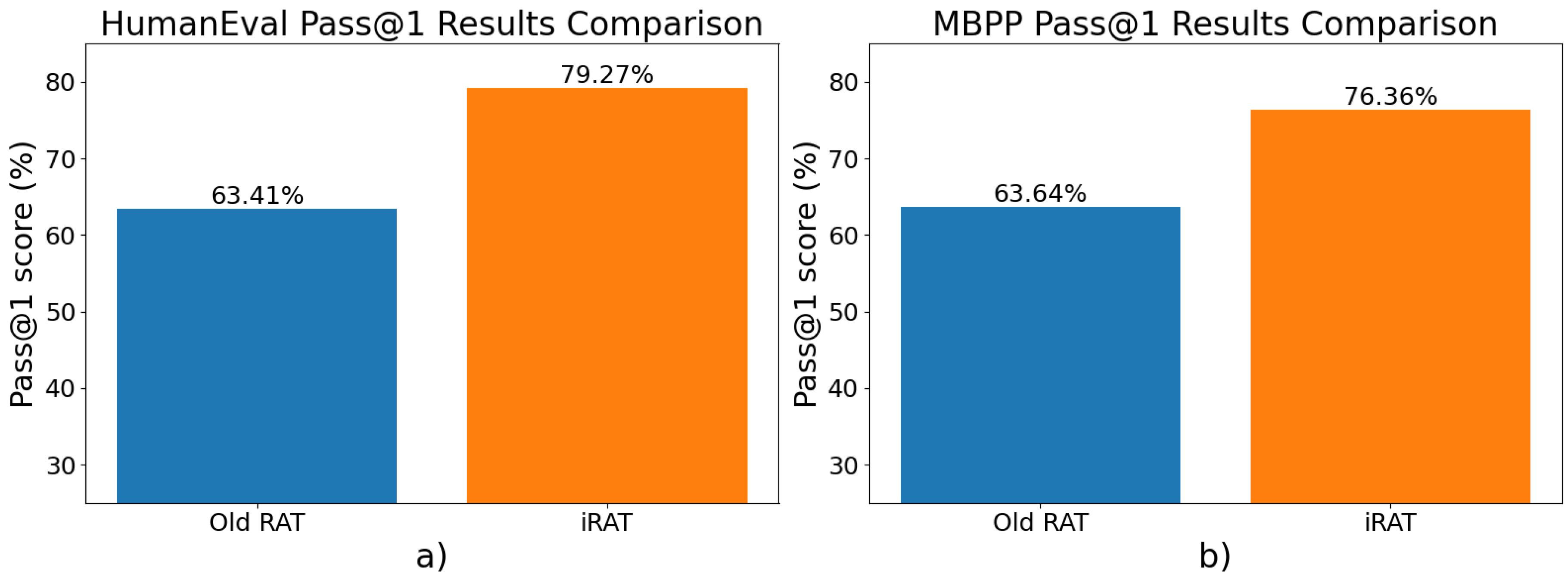

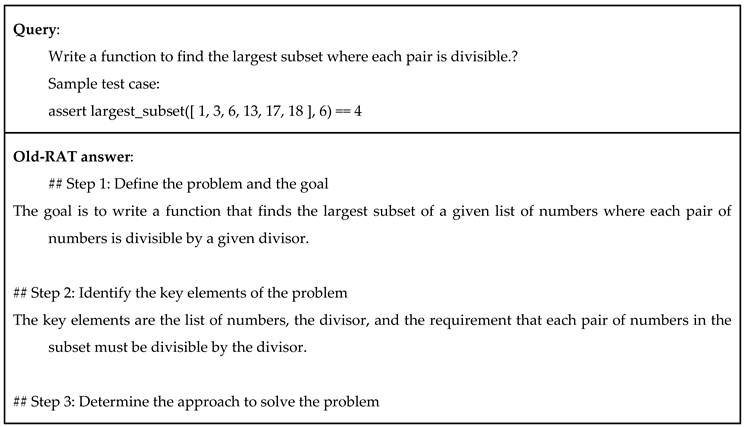

Coding Task Results

Table 1.

HumanEval and MBPP result comparison of old-RAT and iRAT.

Table 1.

HumanEval and MBPP result comparison of old-RAT and iRAT.

| Method |

HumanEval pass@1 score |

MBPP pass@1 score |

| Old-RAT |

63.41% |

63.64% |

| iRAT |

79.27% |

76.36% |

| Improvement |

15.86% |

12.72% |

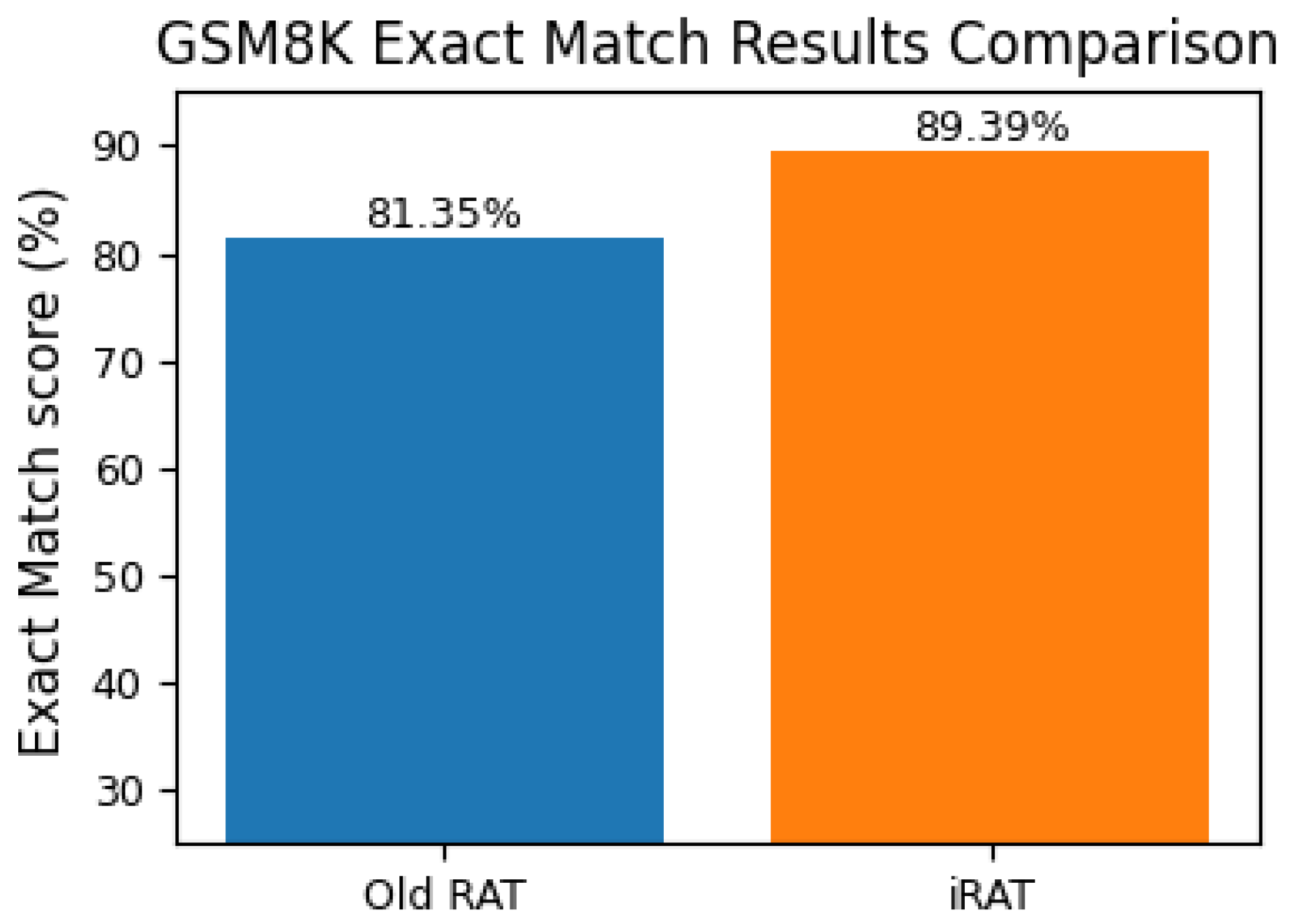

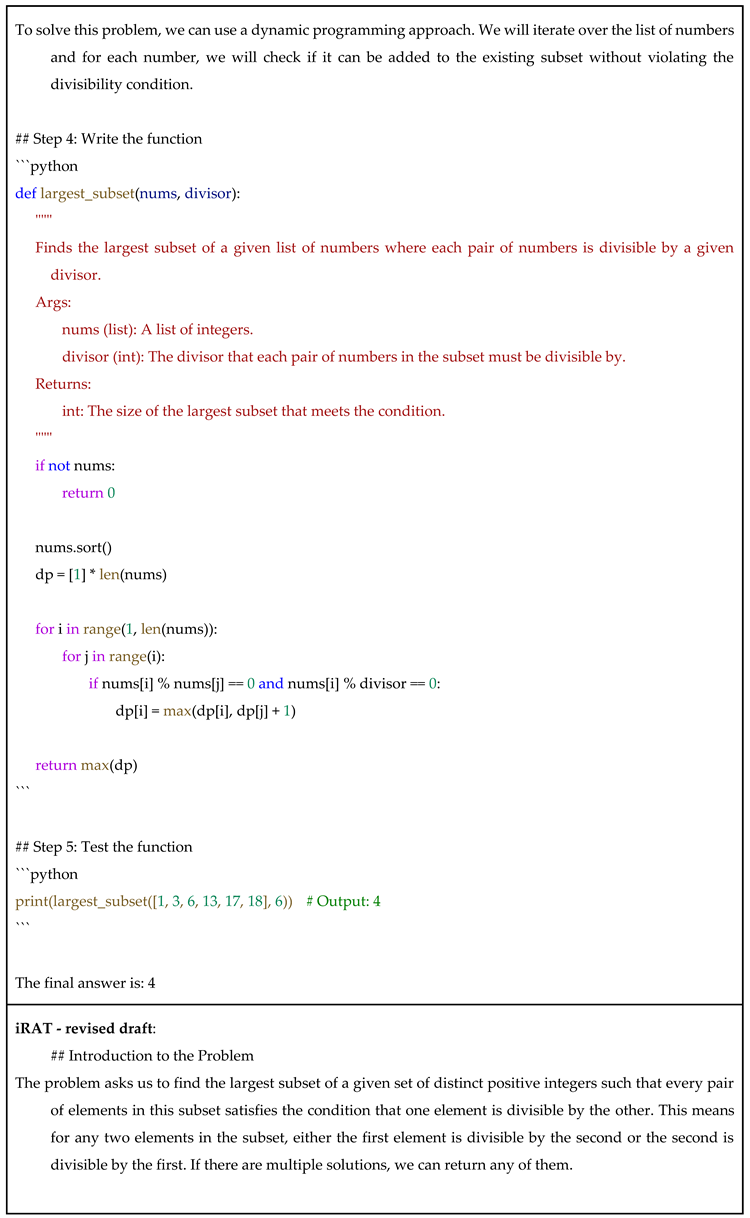

Mathematical Reasoning Task Results

Table 2.

GSM8K result comparison of old-RAT and iRAT.

Table 2.

GSM8K result comparison of old-RAT and iRAT.

| Method |

GSM8K Exact Match score |

| Old-RAT |

81.35% |

| iRAT |

89.39% |

| Improvement |

8.04% |

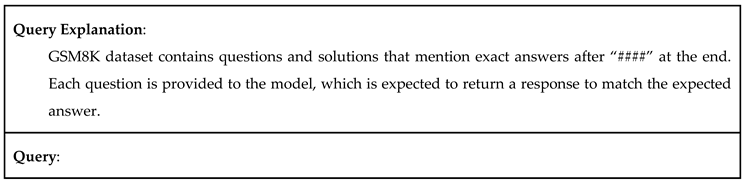

The bar charts below compare the scores visually.

Figure 2.

Bar charts ecomparing pass@1 scores of old-RAT and iRAT in (a) HumanEval dataset and (b) MBPP dataset.

Figure 2.

Bar charts ecomparing pass@1 scores of old-RAT and iRAT in (a) HumanEval dataset and (b) MBPP dataset.

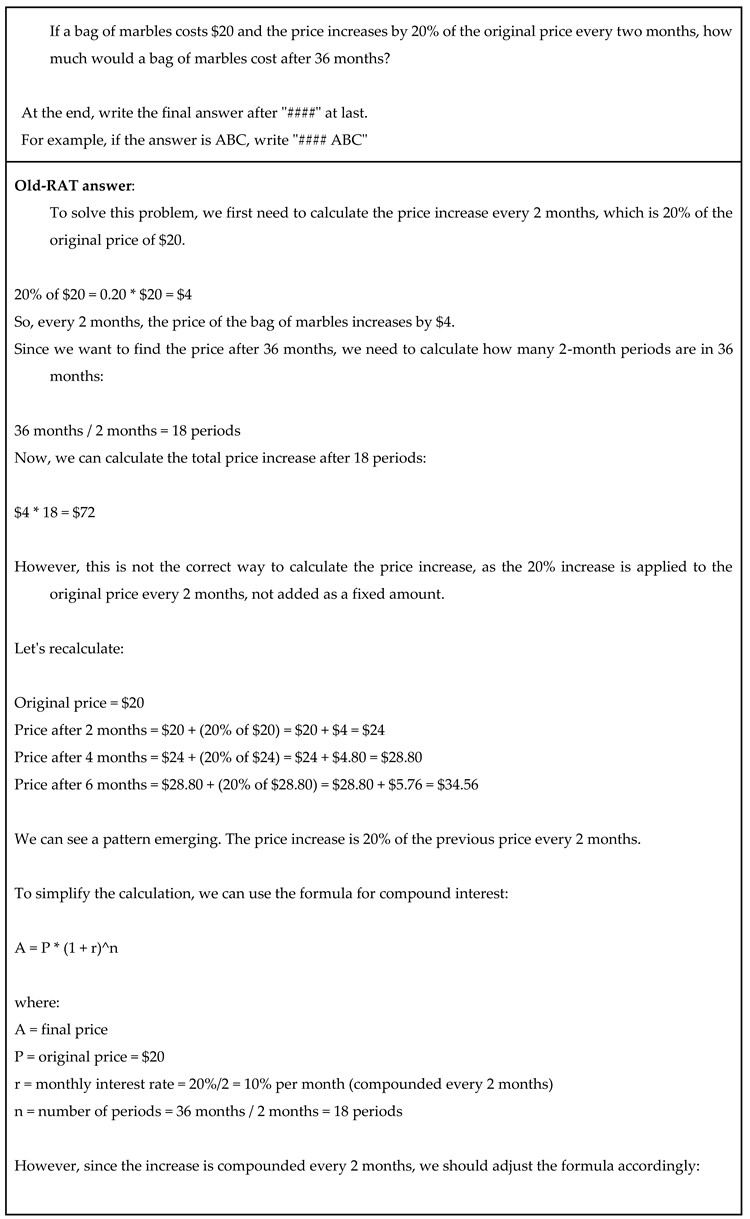

Figure 3.

Bar charts comparing Exact Match (EM) scores of old-RAT and iRAT in GSM8K dataset.

Figure 3.

Bar charts comparing Exact Match (EM) scores of old-RAT and iRAT in GSM8K dataset.

Usage of Retrievals

A comparison of the average retrievals used per query using old-RAT and iRAT for all three datasets is presented in a table below.

Table 3.

Average retrievals per query for RAT and iRAT.

Table 3.

Average retrievals per query for RAT and iRAT.

| Dataset |

Average Retrievals

(old-RAT)

|

Average Retrievals

(iRAT)

|

Reduction in retrievals |

| HumanEval |

4.46 |

3.16 |

29.15% |

| MBPP |

5.24 |

3.36 |

35.88% |

| GSM8K |

3.43 |

1.76 |

48.69% |

Discussion

In HumanEval, the largest increase in accuracy and the smallest reduction in retrievals were observed. For MBPP, a relatively moderate improvement in accuracy and a moderate reduction in retrievals were observed. GSM8K demonstrated a smaller accuracy gain accompanied by the largest reduction in retrievals. A greater improvement in performance was observed in coding tasks compared to mathematical tasks, likely due to the old-RAT already achieving over 80% accuracy on the latter, suggesting a limited room for further improvement. A substantial reduction in retrievals was noted for mathematical tasks compared to coding tasks. iRAT demonstrated its potential to enhance accuracy through replanning while reducing retrievals. Notably, a greater reduction in retrievals corresponds with a smaller performance gain. Importantly, the reduction in retrievals did not negatively impact performance, indicating the effectiveness of trajectory correction.

Limitations and Future Work

Future work may explore a self-reflection process using the selected base model itself, as it possesses a larger knowledge base than the Chain Evaluator model. Old-RAT references the use of vector databases. However, their source code employs Google Search, a procedure that iRAT also adopts to enable fair comparison. Future work may compare the performance of both old-RAT and iRAT using vector databases, and also compare both systems for queries that require a significantly larger number of reasoning steps. Similar to old-RAT, iRAT has been tested using English datasets, although future work could extend it to multilingual datasets. The source code was not designed for commercial deployment, as it has not been evaluated under high-concurrency conditions. Future work may enable support for more websites and PDF files. iRAT has been experimented on coding and mathematical reasoning tasks, and may also be experimented across diverse problem domains.

Conclusions

This study introduced iRAT, an enhanced reasoning framework developed upon old-RAT, incorporating new modules designed to address its limitations. iRAT improves reasoning accuracy and resource efficiency through controlled retrieval and replanning mechanisms. These enhancements enable iRAT to selectively leverage external knowledge sources and revise intermediate reasoning through replanning. Experimental results indicate that the system improves correctness and coherence in multi-step reasoning tasks. iRAT improved accuracy while enhancing control over resource consumption through the reduction of unnecessary retrievals and processing overhead, rendering it more suitable for real-world applications compared to CoT, RAG, and old-RAT. While several challenges and opportunities for future work remain, iRAT represents a novel advancement in adaptable reasoning frameworks.

Author Contributions

Zeeshan Ali: Architecture, uncertainty evaluation, and Chain Evaluator model. Praneeth Vadlapati: Pipeline, result-filter module, evaluation, most of the code and paper, and team leadership. Aryan Singh: Retrieval module with budget control, EDA, pre-processing, pipeline wireframe, and bug fixing in budget control. Alvaro Arteaga: User input normalization, and the idea of spam website filter. Every member assisted in editing the paper.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Dr. Leonard D. Brown at the University of Arizona for suggesting improvements to this work.

Appendix A

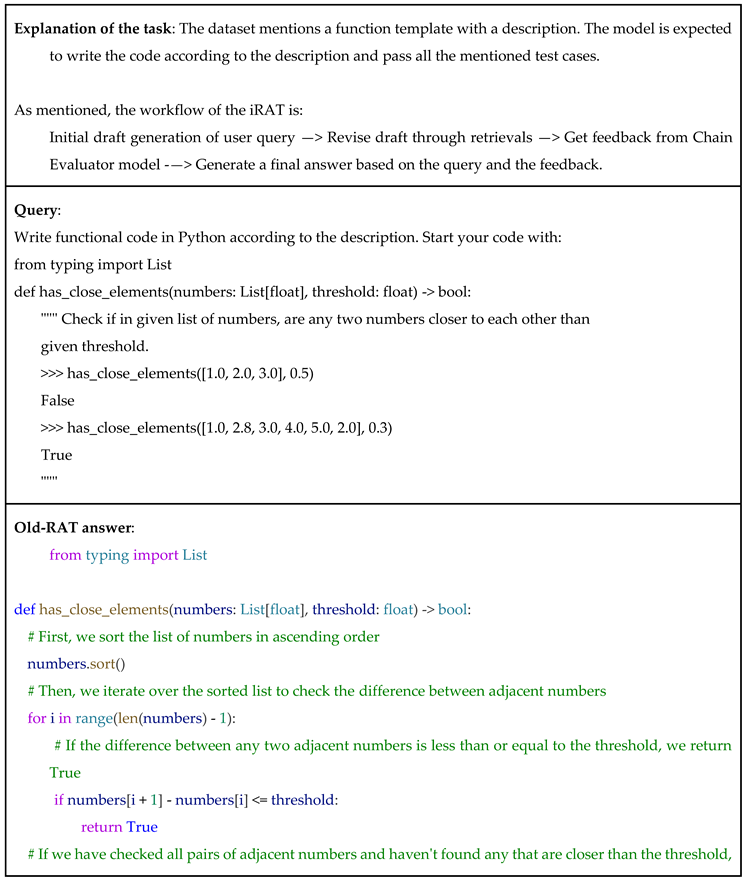

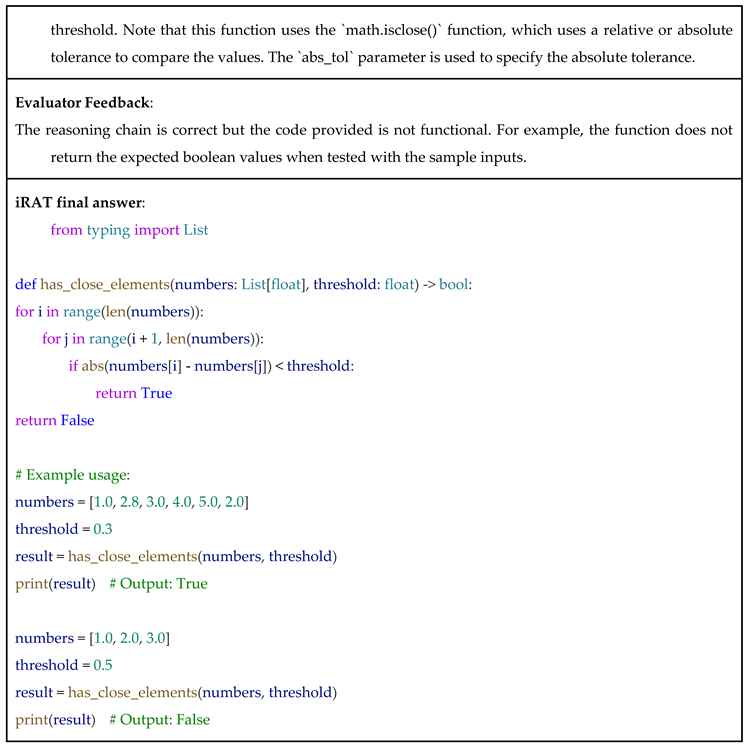

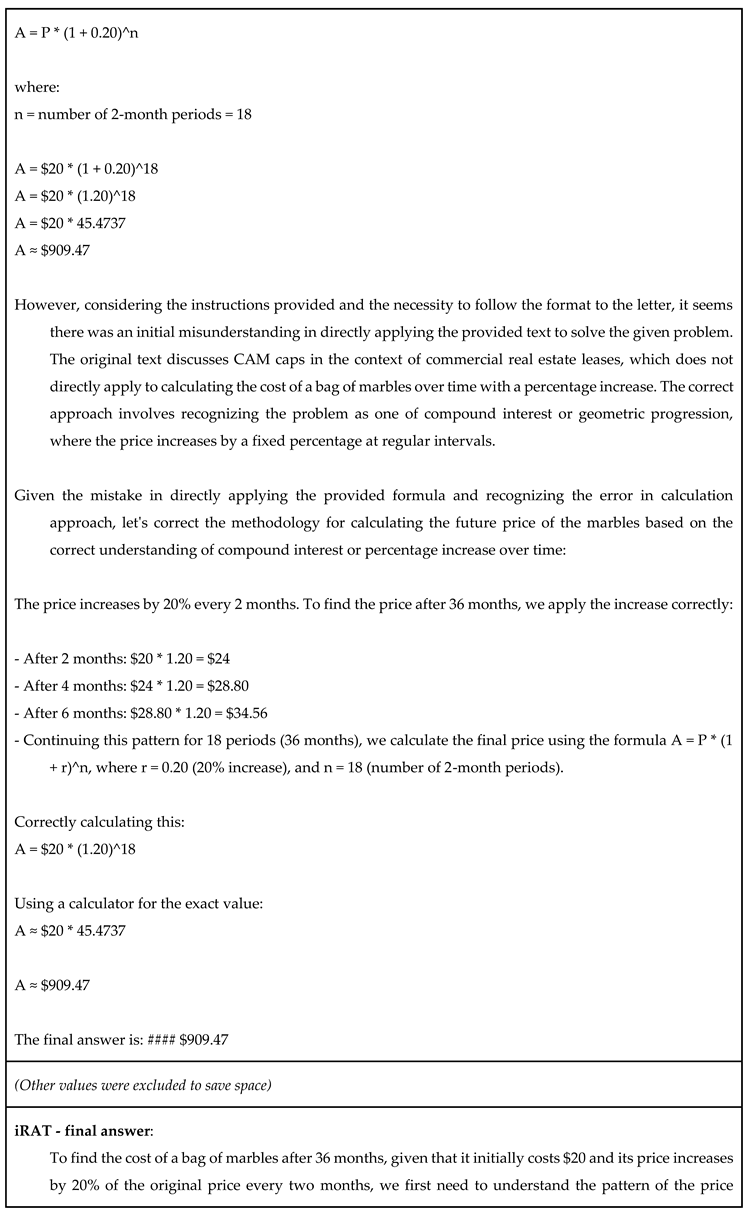

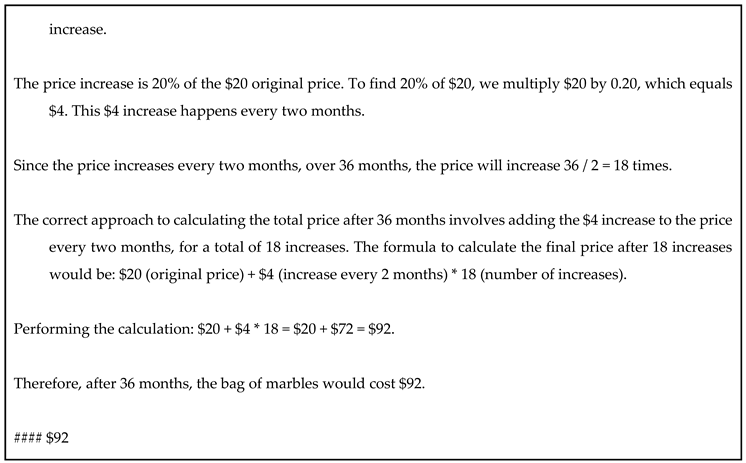

Examples of Thoughts Generated

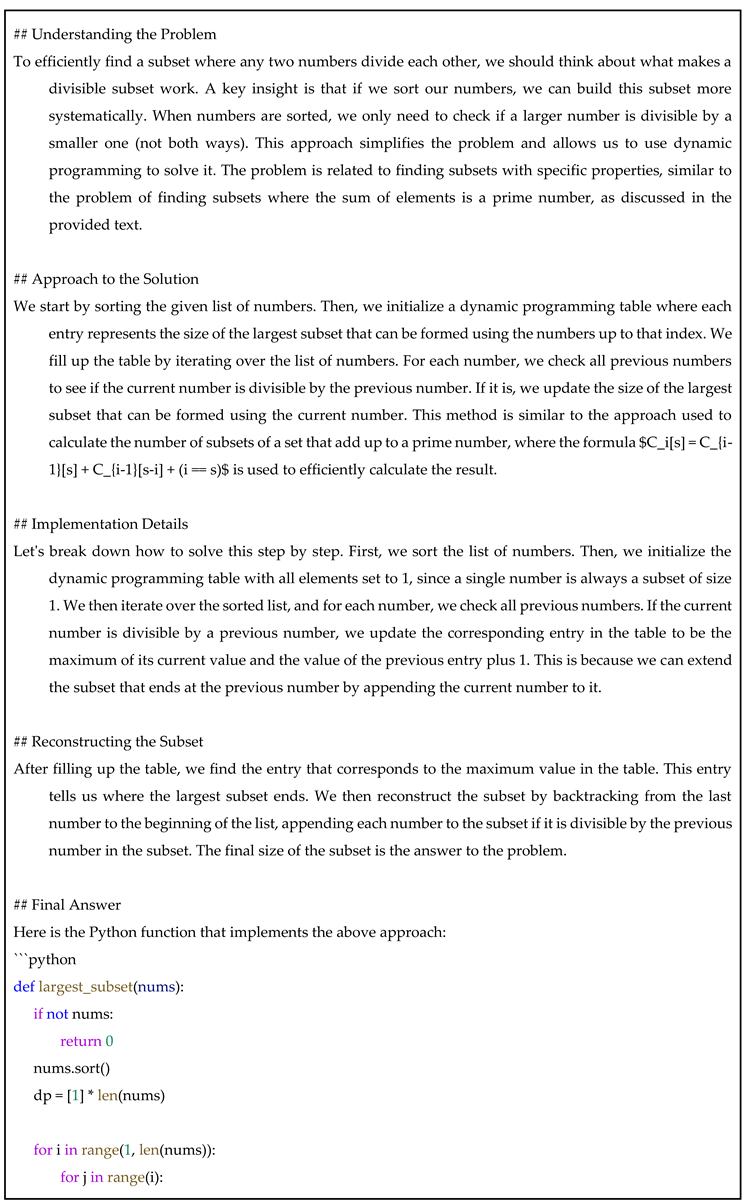

Example 1: (From HumanEval Dataset)

Example 2: (From MBPP Dataset)

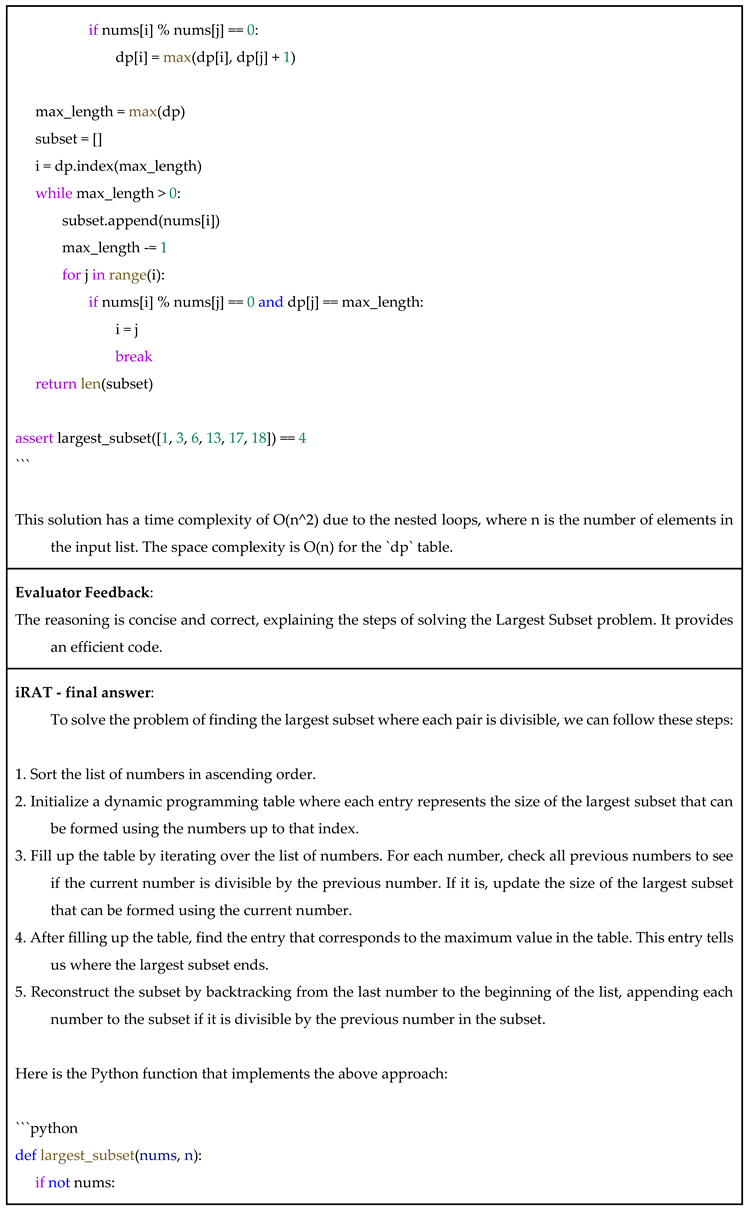

Example 3: (From GSM8K Dataset)

Datasets

HumanEval: OpenAI’s code generation dataset comprises 164 Python programming problems, each with a function signature, docstring, body, and multiple unit tests. It is used to evaluate the correctness of program synthesis from natural language descriptions. The dataset covers coding problems related to language comprehension, algorithms, and basic mathematics, with some tasks resembling introductory software engineering interview questions. It includes columns “prompt,” “canonical_solution,” “test,” and “entry_point”.

MBPP: Google’s code generation dataset that includes 974 Python programming problems designed to be solvable by beginner programmers. Each problem consists of an English task description, a code solution, and three automated test cases. Old-RAT evaluated the test set from index 11 to 175, and the same has been used for iRAT.

GSM8K: OpenAI’s mathematical reasoning dataset that consists of 8790 high-quality and linguistically diverse mathematical word problems. It contains questions and answers. Answers include a reasoning followed by a number after “####” at the end, which is used to compare with the model’s response.

MS MARCO: Microsoft’s dataset that contains 1 million real user queries, each query paired with at most 10 results containing paragraphs, URLs, and the selections of relevant paragraphs. We use this to evaluate re-ranking models on coding tasks prior to implementation in the result-filtering module. More information is mentioned in a section below.

Malicious URLs Dataset: A vast dataset of 651,191 URLs, including 428103 benign or safe URLs, 96457 defacement URLs, 94111 phishing URLs, and 32520 malware URLs. All non-safe URLs were used to filter the query results in the result-filtering module.

Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

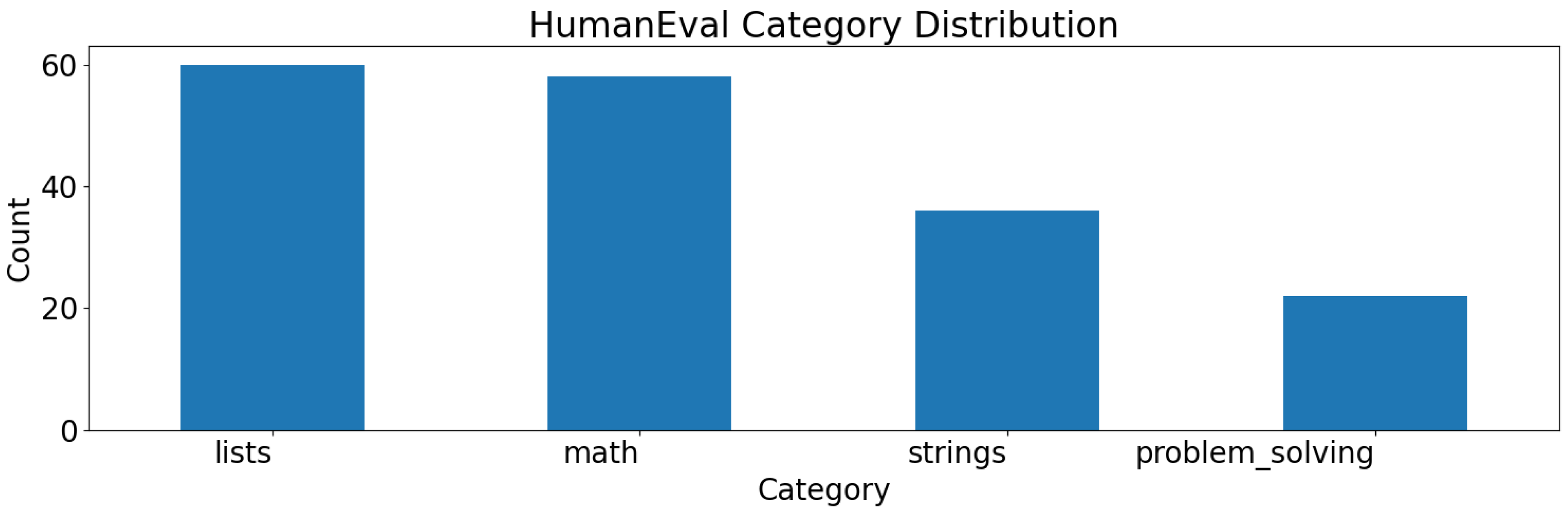

HumanEval

This section presents a graphical analysis of the distributions of categories of queries and prompts from different datasets to identify imbalances. For the HumanEval dataset, there are four main categories of programming problems: lists, math, strings, and problem-solving. The class distribution is not unbalanced.

Figure A1.

HumanEval Category Distribution.

Figure A1.

HumanEval Category Distribution.

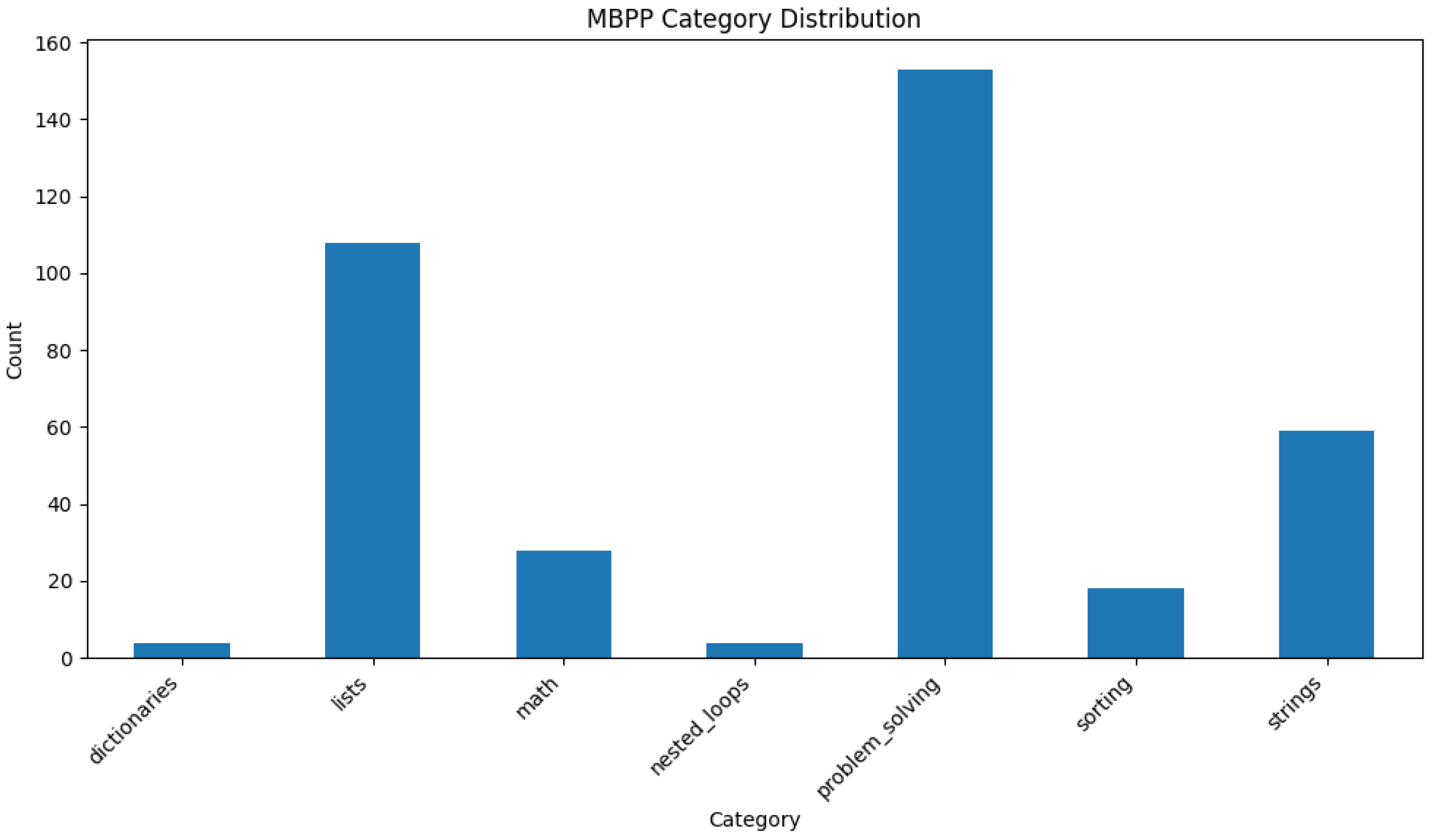

MBPP

For the MBPP dataset, there are seven prompt categories, with lists and problem-solving being the most prevalent, followed by strings, math, and sorting. The dictionaries and nested_loops categories are under-represented. This indicates a category imbalance within the dataset.

Figure A2.

MBPP Category Distribution.

Figure A2.

MBPP Category Distribution.

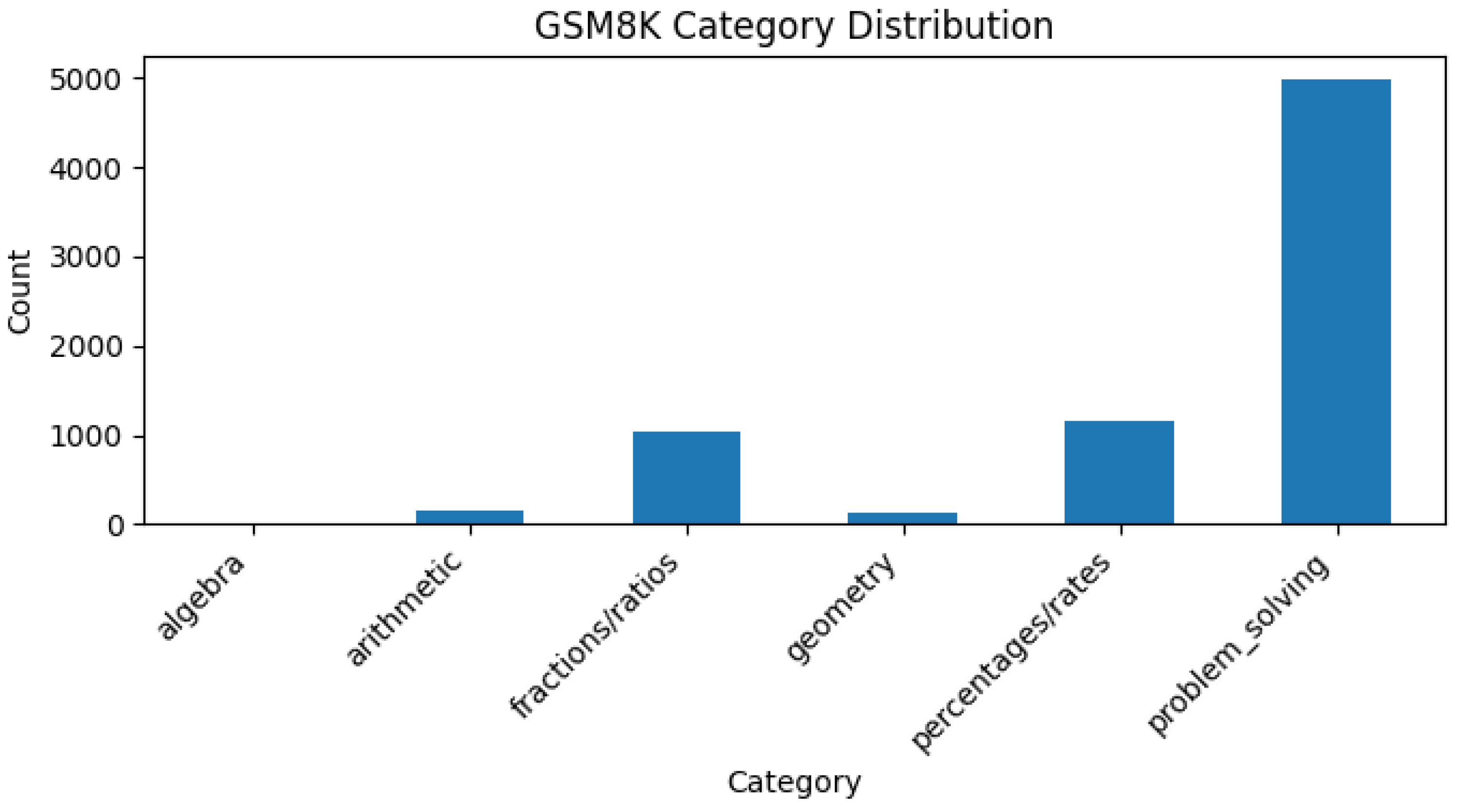

GSM8K

For the GSM8K dataset, the problem-solving category is the most prevalent, followed by fractions/ratios and percentages/rates. Categories that are under-represented are geometry, arithmetic, and algebra. This suggests a clear class imbalance.

Figure A3.

GSM8K Category Distribution.

Figure A3.

GSM8K Category Distribution.

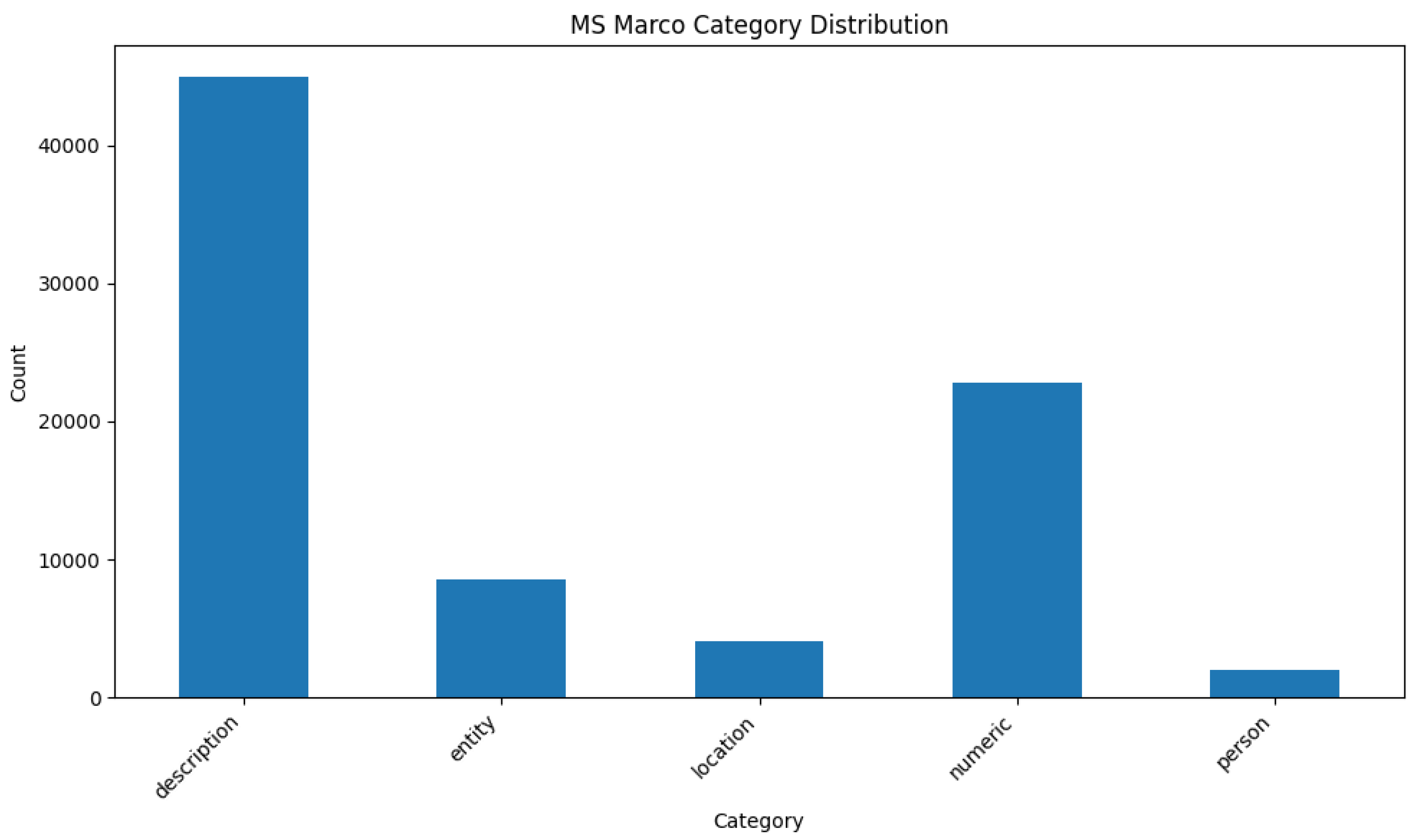

MS MARCO

For the MS MARCO, there are 5 query categories for the data in the dataset. The description and numeric categories are the most prevalent, while entity, location, and person were under-represented. This reflects a category imbalance in the dataset.

Figure A4.

MS MARCO Category Distribution.

Figure A4.

MS MARCO Category Distribution.

Hardware and Software

Table A1 summarizes the hardware configurations of the Virtual Machines (VMs) that were used for evaluating old-RAT and iRAT.

Table A2 lists the Python libraries used for this project and their respective versions.

Table A1.

Hardware details.

Table A1.

Hardware details.

| Name |

|

Value |

| Platform |

|

Azure |

| VM name |

|

B4as_v2 |

| vCPUs |

|

4 |

| Memory |

|

16 GB |

| GPU |

|

N/A |

Table A2.

Python (v3.12.3) - packages used.

Table A2.

Python (v3.12.3) - packages used.

| |

| Package |

Version |

| beautifulsoup4 |

4.13.4 |

| cohere |

5.15.0 |

| datasets |

3.6.0 |

| google-api-python-client |

2.174.0 |

| gradio |

5.35.0 |

| html2text |

2025.4.15 |

| html5lib |

1.1 |

| human-eval |

1.0.3 |

| IPython |

9.4.0 |

| jupyter |

1.1.1 |

| langchain |

0.3.26 |

| langchain-community |

0.3.27 |

| last_layer |

0.1.33 |

| loguru |

0.7.3 |

| lxml |

6.0.0 |

| matplotlib |

3.10.3 |

| numpy |

2.3.1 |

| openai |

1.93.0 |

| pysafebrowsing |

0.1.4 |

| python-dotenv |

1.1.1 |

| readability-lxml |

0.8.4.1 |

| requests |

2.32.4 |

| sentence-transformers |

5.0.0 |

| simple-cache |

0.35 |

| tiktoken |

0.9.0 |

| transformers |

4.53.0 |

Evaluation of Re-Ranking Models for Coding Tasks

The Attention-Retrieval method was evaluated on coding tasks using pre-trained re-ranking models, which assign ranks and scores based on query and paragraphs. A coding-related subset was extracted from the MARCO dataset [

22] based on the occurrence of coding-related keywords in the queries. The dataset includes 2511 training rows and 310 validation rows. Scores were computed using the R-Precision metric, which measures the proportion of relevant paragraphs within the top-R-ranked results, where R denotes the number of ground-truth relevant paragraphs for a given query. For each query, the model was used to predict scores for each paragraph, with the top R scoring paragraphs selected. The accuracy of selecting the correct paragraphs was computed.

Table A3.

Accuracy on the coding subset of MARCO.

Table A3.

Accuracy on the coding subset of MARCO.

| Model |

Parameters |

Estimated R-Precision Score |

| ms-marco-MiniLM-L6-v2 [13] |

22.7M |

78.71% |

| ms-marco-MiniLM-L4-v2 [23] |

19.2M |

76.45% |

| mxbai-rerank-xsmall-v1 [24] |

70.8M |

73.87% |

Models pre-trained on the MARCO dataset outperformed the larger “mxbai” model on the MARCO-derived task. These results demonstrate the suitability of the evaluated models for coding tasks. Considering the trade-off between model size and performance, ms-marco-MiniLM-L6-v2 was selected for integration into the result-filtering module. The evaluation code is available at:

https://github.com/prane-eth/iRAT/…/Result-filter/AR_evaluate.py.

Chain Evaluator Model - Initial Experiment with Reinforcement Learning (RL)

As part of our experimental investigation, we trained a supervised reward model to evaluate reasoning chains generated by an LLM with robust factual grounding. Each chain was rated on a scale from 1 to 5 based on its logical coherence and factual accuracy. However, the reward model, based on the RoBERTa-base architecture, demonstrated limited capacity to learn meaningful reward signals. Upon further analysis, we determined that the model lacked the embedded world knowledge required to interpret and assess the reasoning chains accurately. For instance, evaluating a reasoning chain that explains why the sky appears blue necessitates foundational understanding of physical phenomena such as light scattering and atmospheric composition—knowledge that the relatively small reward model did not possess.

Unlike the LLM, which implicitly encodes such knowledge through extensive pretraining, the reward model operated in isolation, relying primarily on surface-level token patterns without sufficient contextual depth. As a result, it was unable to reliably distinguish between valid and flawed reasoning. This mismatch in knowledge and interpretive capacity ultimately led us to abandon the reward model approach. Instead, we employed the fine-tuned LLM directly as an evaluator, which demonstrated substantially improved alignment with reasoning accuracy and coherence.

References

- J. Wei et al., “Chain-of-Thought Prompting Elicits Reasoning in Large Language Models,” 2023, arXiv. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2201.11903.

- Y. Gao et al., “Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey,” 2024, arXiv. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2312.10997.

- P. Shojaee, I. Mirzadeh, K. Alizadeh, M. Horton, S. Bengio, and M. Farajtabar, “The Illusion of Thinking: Understanding the Strengths and Limitations of Reasoning Models via the Lens of Problem Complexity,” 2025, arXiv. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, A. Liu, H. Lin, J. Li, X. Ma, and Y. Liang, “RAT: Retrieval Augmented Thoughts Elicit Context-Aware Reasoning and Verification in Long-Horizon Generation,” in NeurIPS 2024 Workshop on Open-World Agents, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://openreview.net/forum?id=5QtKMjNkjL.

- “RAT on GitHub.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/CraftJarvis/RAT.

- Asai, Z. Wu, Y. Wang, A. Sil, and H. Hajishirzi, “Self-RAG: Learning to Retrieve, Generate, and Critique through Self-Reflection,” 2023, arXiv. [Online]. Available: https://paperswithcode.com/paper/self-rag-learning-to-retrieve-generate-and.

- J. Sohn et al., “Rationale-Guided Retrieval Augmented Generation for Medical Question Answering,” 2024, arXiv. [Online]. Available: https://paperswithcode.com/paper/rationale-guided-retrieval-augmented.

- Meta AI, “meta-llama/Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct,” HuggingFace. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct.

- Sentence Transformers, “all-MiniLM-L6-v2,” Hugging Face. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2.

- J. Bevendorff, M. Wiegmann, M. Potthast, and B. Stein, “Is Google Getting Worse? A Longitudinal Investigation of SEO Spam in Search Engines,” in Advances in Information Retrieval, N. Goharian, N. Tonellotto, Y. He, A. Lipani, G. McDonald, C. Macdonald, and I. Ounis, Eds., Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, 2024, pp. 56–71.

- Google, “Safe Browsing Lookup API (v4),” Google Developers. [Online]. Available: https://developers.google.com/safe-browsing/v4/lookup-api.

- M. Siddhartha, “Malicious URLs dataset,” Kaggle. [Online]. Available: https://paperswithcode.com/dataset/malicious-urls-dataset.

- Cross Encoder, “ms-marco-MiniLM-L6-v2,” Hugging Face. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/cross-encoder/ms-marco-MiniLM-L6-v2.

- “MS MARCO Scores - Pretrained Models,” Sentence Transformers. [Online]. Available: https://sbert.net/docs/cross_encoder/pretrained_models.html#ms-marco.

- Deepseek AI, “DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-1.5B,” Hugging Face. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/deepseek-ai/DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-1.5B.

- E. J. Hu et al., “LoRA: Low-Rank Adaptation of Large Language Models,” 2021, arXiv. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2106.09685.

- OpenAI, “HumanEval.” Hugging Face, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/datasets/openai/openai_humaneval.

- Google Research, “MBPP.” Hugging Face, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/datasets/google-research-datasets/mbpp.

- OpenAI, “GSM8K.” Hugging Face, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/datasets/openai/gsm8k.

- S. Kulal et al., “SPoC: Search-based Pseudocode to Code,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, H. Wallach, H. Larochelle, A. Beygelzimer, F. d’Alché-Buc, E. Fox, and R. Garnett, Eds., Curran Associates, Inc., 2019. [Online]. Available: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2019/file/7298332f04ac004a0ca44cc69ecf6f6b-Paper.pdf.

- P. Rajpurkar, J. Zhang, K. Lopyrev, and P. Liang, “SQuAD: 100,000+ Questions for Machine Comprehension of Text,” in Proceedings of the 2016 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, J. Su, K. Duh, and X. Carreras, Eds., Austin, Texas: Association for Computational Linguistics, Nov. 2016, pp. 2383–2392. [CrossRef]

- Microsoft, “MS MARCO (v2.1).” Hugging Face, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/datasets/microsoft/ms_marcoms-marco.

- Cross Encoder, “ms-marco-MiniLM-L4-v2,” Hugging Face. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/cross-encoder/ms-marco-MiniLM-L4-v2.

- Mixedbread AI, “mxbai-rerank-xsmall-v1.” Hugging Face, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://huggingface.co/mixedbread-ai/mxbai-rerank-xsmall-v1.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).