1. Introduction

Anemia remains a critical global public health issue, affecting approximately 36.5% of pregnant women worldwide, with particularly high prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia [

1]. In Ethiopia, about 41% of pregnant women are anemic, with regional variations ranging from 9% in Addis Ababa to as high as 65.9% in the Somali region [

2]. Maternal anemia is associated with severe health risks, including increased maternal morbidity and mortality, where severe anemia can elevate maternal death risk by 20% [

3]. It also contributes to adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth, fetal anemia, low birth weight, intrauterine growth restriction, reduced gestational weight gain, and increased perinatal mortality [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Beyond health impacts, anemia can diminish physical productivity, perpetuating economic hardship at both individual and societal levels [

7].

To address the global burden of anemia, the WHO promotes two strategic approaches: nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive interventions [

8]. Nutrition-specific strategies focus on addressing the direct causes of anemia, such as poor dietary intake of essential micronutrients like iron and vitamin A, through supplementation and food fortification programs. Meanwhile, nutrition-sensitive approaches, like dietary diversification, aim to enhance year-round access to a variety of nutrient-rich foods [

8,

9]. In Ethiopia, government initiatives aimed at preventing anemia include promoting dietary diversity, providing iron and folic acid supplements, encouraging malaria prevention measures, and implementing deworming campaigns [

10]. The national "Seqota Declaration" also seeks to ensure universal access to adequate nutrition by 2030 [

11]. Community health programs, particularly health extension services focused on the first 1000 days of life, play a vital role in advancing these nutrition goals [

10,

11].

Despite these comprehensive efforts, anemia among pregnant women remains widespread in Ethiopia, especially in rural areas [

2,

12,

13,

14]. A key challenge is the limited dietary diversity observed in most households, where women's diets predominantly consist of starchy cereals low in essential micronutrients [

15,

16,

17,

18]. The consumption of nutrient-rich animal-source foods has declined due to rapid population growth and unplanned urbanization, thereby exacerbating the risk of micronutrient deficiencies among marginalized groups [

19].

Given these challenges, identifying affordable and culturally acceptable food-based solutions to enhance maternal nutrition is crucial [

20]. Amaranth is a highly nutritious yet underutilized crop in Ethiopia, offering significant potential. Compared to commonly consumed cereals, amaranth seeds provide higher levels of protein, iron, zinc, calcium, and dietary fiber. Specifically, 100 grams of edible amaranth contains 7.6–18.0 mg of iron, 11–19 g of crude protein, and notable amounts of essential amino acids like methionine and lysine, nutrients often deficient in other grains. Furthermore, amaranth is rich in magnesium, calcium, vitamin C and B6, folate, and beneficial unsaturated fatty acids [

21,

22,

23,

24].

Beyond its nutritional composition, evidence suggests that amaranth offers various health benefits, including promoting muscle maintenance, improving cardiovascular health, enhancing antioxidant status, and preventing anemia [

25,

26]. Despite its widespread availability, especially in southern Ethiopia, amaranth is often regarded as a wild plant and remains largely neglected in local diets. Increasing its consumption could substantially boost dietary nutrient intake and improve household food security [

27].

While prior research has investigated the nutritional composition of amaranth and methods for phytate reduction [

28,

29], limited studies have assessed its in vivo effects, particularly in the form of flatbread. A cluster-randomized controlled trial conducted in Hawassa, Ethiopia, among children aged 2-5 years demonstrated that consumption of homemade amaranth-based bread improved hemoglobin concentration and reduced iron deficiency anemia (IDA) [

27]. However, to our knowledge, no studies in Ethiopia have evaluated the effect of amaranth grain flatbread consumption on hemoglobin concentration and IDA among pregnant women. To address this gap, we conducted a six-month, community-based, parallel-group, cluster-randomized controlled trial. The cluster design was selected to minimize contamination between intervention and control groups, as participants within the same community or health center could influence each other's dietary behaviors, potentially compromising the integrity of individual randomization. Additionally, randomizing at the cluster level was logistically feasible and aligned with the community-based nature of the intervention.

This cluster-randomized trial aimed to evaluate the potential of amaranth grain as an effective nutritional intervention for pregnant women with anemia. By evaluating the effects of amaranth grain flatbread on hemoglobin concentration and IDA, the findings aim to inform nutrition programs, policy development, and food security strategies. Ultimately, this work contributes toward national efforts to combat maternal anemia and supports the achievement of broader Sustainable Development Goals. Therefore, the objective of this parallel-group, two-arm cluster-randomized controlled trial (RCT) was to evaluate the effect of locally prepared amaranth grain flatbread consumption, compared to maize bread consumption, on hemoglobin concentration and IDA among pregnant women with anemia. We hypothesized that consumption of locally prepared amaranth grain flatbread would improve hemoglobin concentration and reduce IDA when compared to maize bread consumption among pregnant women with anemia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reporting and Ethical Considerations

We reported this study according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines for cluster RCTs [

30], and the checklist is provided as supporting file 1. The trial was registered in the International Clinical Trials Registry under registration number NCT06536153. There were no deviations from the original study protocol. All procedures, including recruitment, intervention delivery, outcome assessments, and follow-up, were implemented as planned. Ethical approval for this trial was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Hawassa University's College of Medicine and Health Sciences (reference number IRB/027/16). Support letters were secured from the Hawassa University School of Public Health, the Sidama Region Health Bureau, and local kebele administrators. Two levels of consent were required before the study commenced. Initially, approval was obtained from community leaders on behalf of the community prior to randomization. Subsequently, written informed consent was collected from each participant before they were enrolled in the study.

2.2. Study Setting

This cluster RCT was conducted in the Hawela Lida district, located in the Sidama region of Ethiopia. Hawela Lida is one of 30 districts within the region and lies approximately 289 kilometers south of Addis Ababa. The district comprises 11 rural and two urban kebeles, the smallest administrative units in Ethiopia. According to the Sidama Regional State Health Bureau's 2024 report, Hawela Lida has a total population of 131,848, distributed across an estimated 24,281 households. Women of reproductive age (WRA) constitute approximately 24.3% of the district's population [

31].

Agriculture is the predominant economic activity across all kebeles, with key crops including Enset (false banana), maize, coffee, khat, barley, haricot beans, sweet potatoes, and Indigenous varieties of cabbage. The district's health infrastructure comprises 20 government health posts, four health centers, five private medium-sized clinics, two non-governmental organization (NGO) clinics, and six private pharmacies. A total of 482 health professionals of various disciplines serve the population. Health posts, managed by Health Extension Workers (HEWs), provide a range of Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health (MNCH) services, including health education, nutritional screening and treatment for children, antenatal and post-natal care, and family planning services. The district's potential health service coverage through existing facilities is estimated at 70% [

31].

Hawela Lida was selected as the study site due to its relatively accessible transportation network, favorable geographic location for supervision, and the logistical feasibility of addressing potential challenges during the intervention's implementation.

2.3. Study Design and Period

A parallel-group, two-arm cluster RCT was conducted between September 2024 and February 2025. In this design, entire clusters were randomly assigned to either the intervention or control arm and remained in their assigned groups throughout the study period. Accordingly, all participants within a given cluster received the same allocation: either exposure to the intervention (amaranth grain flatbread) or the comparator, maize bread.

2.4. Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

The study population consisted of randomly selected pregnant women within the clusters. Pregnant women were eligible for inclusion if they were less than three months gestational age at enrollment, had mild or moderate anemia, and had been residing in the Hawela Lida district for a minimum of six months. Pregnant women were classified as having IDA if they had a serum ferritin concentration <15 ng/mL, indicating depleted iron stores. Among those with confirmed IDA based on serum ferritin levels, anemia severity was further categorized based on hemoglobin concentration: Mild anemia: hemoglobin between 10.0–10.9 g/dL; Moderate anemia: hemoglobin between 7.0–9.9 g/dL; and severe anemia: hemoglobin <7.0 g/dL. Participants were excluded if they met any of the following criteria:

Diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder that could interfere with participation or informed consent procedures.

Presence of chronic illnesses such as tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, or cancer.

History of blood transfusion within the previous six months.

History of malaria infection at least three times within the past three months.

Severe anemia identified during the baseline survey. These women were excluded from the trial and referred to the nearest health facility for immediate medical care.

2.5. Sample Size Determination

The sample size for this trial was calculated using OpenEpi version 3.01, based on assumptions for a cluster RCT. In the absence of prior cluster RCTs on the same topic, estimates were derived from the 2019 Ethiopian Mini Demographic and Health Survey [

32]. The national prevalence of IDA among pregnant women (41.0%) was used to estimate the control arm prevalence (P1 = 41.0%), assuming that the intervention would reduce the prevalence by 10% (P2 = 31.0%). The sample size calculation was based on a 95% confidence interval (CI) and 80% power.

Based on these assumptions, the estimated effective sample size for an individually randomized trial would be 102 participants per arm. To account for the cluster design, the minimum required number of clusters was calculated using an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.05, which is consistent with recommended values for similar studies [

33,

34,

35]. Multiplying the total individual sample size (n = 204) by the ICC factor (0.05) yielded approximately 10.2 clusters for both groups.

To account for the design effect, the effective sample size was adjusted using a variance inflation factor (VIF) of 1.5, calculated as VIF = 1 + [(n–1) × ICC], assuming an average cluster size of 17 participants. Accordingly, the final sample size consisted of 306 participants, with 153 participants allocated to each study arm.

2.6. Randomization

A multi-stage sampling approach was employed to select the study participants. First, the Hawela Lida district was purposively selected from the Sidama region, considering accessibility and feasibility for the study's implementation. In the second stage, 10 kebeles were randomly selected using a computer-generated simple random sampling method. In the third stage, cluster randomization was performed to allocate eligible pregnant women within clusters to either the intervention or control arm.

We employed stratified randomization in our study. The study area comprised 13 kebeles, which were stratified into two strata based on place of residence: urban and rural. Stratification by location was intended to reduce variability between clusters and to ensure that key covariates were balanced across the two study arms

[36,37]. To further enhance comparability between groups, an equal number of clusters from each stratum were randomly allocated to the intervention and control arms. An independent biostatistician, who was not involved in participant recruitment, intervention delivery, or familiar with the study area, conducted the computer-generated randomization process without replacement.

Specifically, using a computer-generated randomization procedure, two urban kebeles were randomly assigned to each arm. Likewise, the eight rural kebeles were randomly allocated to either the intervention or control group using the same method. Following cluster assignment, 31 eligible pregnant women were randomly selected from each kebele to participate in the study. The sampling frame was developed through a house-to-house census of all households in the selected kebeles, conducted by trained field staff.

2.7. Intervention Procedure

The intervention variable was the consumption of amaranth grain flatbread. The intervention group received locally prepared amaranth grain flatbread for six months, from enrollment until delivery, while the control group received the commonly consumed maize bread (See

S2 File). Pregnant women in the intervention and control groups were referred to as the "amaranth arm" and "maize arm", respectively. Pregnant women in the intervention arm (N = 153) received 200 g of flatbread daily, consisting of 30% chickpea and 70% amaranth grain by mass, for six months. Pregnant women in the control arm (N = 153) received 200 g of flatbread daily, made from 100% maize, for six months. In addition to consuming the assigned flatbread, participants in both arms were advised to: (1) continue their usual diet without substitution or restriction, ensuring that the study foods were added rather than replacing existing meals; (2) attend routine antenatal care visits at the nearest health facility, following Ethiopia’s national guidelines; (3) avoid the use of any additional nutritional supplements not prescribed through routine antenatal care, unless medically indicated; and (4) report any side effects, gastrointestinal discomfort, or allergic reactions related to the flatbread consumption to the community health worker or research team. To minimize nutritional confounding, all participants received more than 90 iron folic acid supplements at baseline following national guidelines, with monthly follow-up and pill counts to monitor adherence. Its supplementation proportion after six months was comparable between groups and therefore not adjusted for in multivariable models. Similarly, soil-transmitted helminthiasis was treated in both arms using piperazine citrate syrup as per ethical recommendations. Follow-up assessments of soil-transmitted helminthiasis and other infections revealed no significant differences between groups.

2.8. Recipe Preparation and Iron Bioavailability Analysis

The recipe for the amaranth flatbread was developed following the Recommended Dietary Allowance. According to the Recommended Dietary Allowance, 200 g of amaranth flatbread consisting of 30% chickpea and 70% amaranth grain provides 30 mg of iron, which accounts for 50% of the Recommended Dietary Allowance, assuming an iron absorption rate of 15-20% [

29]. A study conducted by the Hawassa University Department of Food Sciences found that amaranth-grain flatbread was safe for consumption up to 48 hours after preparation and demonstrated an improvement in nutritional value [

38].

To reduce phytate levels in the amaranth grain, a home-level processing method was employed. The amaranth grain was soaked in water with 5 milliliters of lemon juice per 100 milliliters of water for 24 hours, followed by 72 hours of germination. The grain was then sun-dried, roasted, and ground using a nearby electrical mill before being used in the fermentation process to make the flatbread

[27,29]. Maize used in the control group bread was roasted and fermented similarly to achieve a comparable color and texture to the amaranth bread.

Supporting evidence from studies conducted in Ethiopia and Kenya has shown that home-based processing techniques such as soaking and germination significantly reduce phytate levels and enhance the bioavailability of iron and other essential macro- and micronutrients [

29]. To assess the iron bioavailability of the processed amaranth grain bread, a 200-gram sample was sent to a public health institute laboratory in Ethiopia. The laboratory technicians reported the iron and phytate content of the sample in milligrams, which were subsequently converted to grams by dividing by 1000.

Using these values, the molar ratio of phytate to iron was calculated to assess the bioavailability of the iron. The molecular weights of phytate (660 g/mol) and iron (56 g/mol) were used to calculate the moles of each compound, with the molar ratio determined by dividing the moles of phytate by the moles of iron. A critical molar ratio of phytate to iron greater than 14 may impair iron absorption

[39,40]. Based on these calculations, the iron bioavailability in the processed amaranth grain was assessed and found to be below the critical threshold expected to impair iron absorption in our study, which was set at 11.

2.9. Acceptability Test

An acceptability study was conducted on 5% of the study participants prior to the intervention to assess the acceptability of the amaranth grain and maize bread. Acceptability testing was performed according to a protocol similar to that used in previous studies [

38]. The aim was to evaluate the taste, acceptability, and physical tolerance of both the newly prepared amaranth grain bread and the maize bread (details of the acceptability test are provided in

S2 File).

2.10. Masking and Bread Distribution

All trial participants, bread distributors, and outcome assessors (data collectors) were blinded to both the study group assignments and the bread content. The bread distributors assigned to the maize and amaranth groups were distinct, with a total of 12 distributors, one for each kebele. Twelve boxes, each labeled with the name of a pregnant woman, were prepared for distribution. Daily, each distributor delivered the bread to the women’s homes, ensuring close supervision throughout the process. Any unopened bread was returned and recorded by the coordinator in cases of participant absences or refusals.

In our study, both the amaranth and maize breads were prepared to be as similar as possible in appearance and texture to maintain blinding. The breads were roasted and fermented to achieve a comparable color and structure, ensuring that participants, bread distributors, and outcome assessors could not distinguish between the two types based on these characteristics. However, it is important to note that while the breads were made to look and feel alike, there may still be subtle differences in taste. Amaranth grain has a slightly nutty flavor, which could potentially be perceptible to individuals familiar with its taste; nonetheless, the study design aimed to minimize such differences to uphold the integrity of the blinding process. To further ensure blinding, the bread was distributed in identical packaging, labeled only with the participants' names, and delivered daily to their homes by separate distributors for each group.

2.11. Monitoring Compliance with the Intervention

The bread distributors were responsible for monitoring the compliance of the pregnant women at their homes under direct supervision. Any issues, including refusals, non-compliance, or deviations from the protocol, were promptly reported to the coordinator, who documented these incidents in a protocol adherence log.

2.12. Training of the Intervention Research Team

Two women development team (WDT) leaders underwent training on the preparation of flour using home processing techniques, such as germination, soaking, drying, roasting, and milling, one leader for maize flour and the other for amaranth flour. Additionally, they were trained in bread packaging, cooking times, and mixing ratios. The 12 bread distributors, responsible for collecting bread from producers, received training on inspecting bread packages. Furthermore, they were trained in the process of delivering and serving bread to the pregnant women in their homes daily.

2.13. Adverse Events Monitoring.

As part of the cluster RCT protocol, potential adverse events were monitored throughout the study period in both the intervention and control arms. Although formal clinical safety surveillance was not implemented, participants in each cluster were informed to promptly report any discomfort, gastrointestinal symptoms, allergic reactions, or other health issues potentially related to the flatbread consumption to the WDTs or research staff assigned to their kebele. WDTs conducted routine household visits every two weeks to assess adherence and document any adverse symptoms reported by participants. In addition, field supervisors conducted monthly monitoring visits to ensure adherence to the protocol and gather any unreported concerns. The study’s medical supervisor reviewed all complaints or health issues.

2.14. Study Variables

The outcome variables were hemoglobin concentration and iron deficiency anemia, as determined by serum ferritin levels, which were measured at baseline and the end of the 6-month intervention. Trained laboratory technologists performed hemoglobin analysis at all health posts. Each woman's hemoglobin concentration was determined by obtaining a finger-prick blood sample using the HemoCue Hb 301 (HemoCue AB, Angelholm, Sweden). The site was disinfected, and a prick was made on the tip of the middle finger. The first drop of blood was discarded, and the second drop was collected to fill the microcuvette. The cuvette was then inserted into the meter’s holder for analysis. To ensure reliable results, the meter's performance was checked daily using control standards. The meter, designed for capillary blood, was calibrated by pulling the microcuvette to the loading position and then filling it continuously with the sample for examination. Within 10 minutes of filling, the cuvette was placed in the holder and inserted into the meter's measuring position. Hemoglobin concentration: Hemoglobin concentration was measured and recorded within 15–60 seconds, following WHO field survey recommendations

[41,42]. Hemoglobin values were corrected for altitude before data entry, using the appropriate adjustment formula [

41]. All laboratory procedures were conducted following standard operating procedures [

43].

Iron deficiency anemia: Following WHO guidelines, iron deficiency anemia is defined as serum ferritin <15 µg/L in the absence of inflammation, or <30 µg/L in the presence of inflammation, measured using standard ELISA methods. Among those with confirmed IDA based on serum ferritin levels, anemia severity was further categorized based on hemoglobin concentration: Mild anemia: hemoglobin between 10.0–10.9 g/dL; Moderate anemia: hemoglobin between 7.0–9.9 g/dL; and severe anemia: hemoglobin <7.0 g/dL. To account for potential inflammation-mediated increases in ferritin levels, C-reactive protein was concurrently measured using a high-sensitivity ELISA [

44]. Details of the laboratory procedure for serum ferritin measurement are provided in

S2 File.

2.14.1. Baseline Characteristics

The baseline characteristics were categorized into individual and community-level characteristics. Individual-level characteristics included socio-economic and demographic factors, such as maternal age, maternal and paternal occupation, maternal and paternal education, wealth index, and use of mass media. Obstetric characteristics, including maternal age at first marriage and childbirth, gravidity, parity, history of obstetric complications, experience of stillbirth, and pregnancy planning status, were also measured. Additionally, knowledge and practices related to dietary diversity, household food security, malaria infection, iron-rich food consumption, and undernutrition status were included (See

S2 File).

2.14.2. Nutritional Status

Undernourished Status based on Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC): Pregnant women with a MUAC measurement below the cutoff of 23 cm were classified as undernourished, while those measuring 23 cm or above were categorized as having normal nutritional status. MUAC was measured using a flexible, non-stretchable tape, with the subject in the Frankfurt plane, observing the left arm from the side. The measurement was taken to the nearest 0.1 cm with the mother's arms hanging loosely at her sides and palms facing inward [

45].

2.14.3. Dietary Diversity:

Dietary diversity scores for women were calculated using the Food and Agriculture Organization guidelines [

46]. The score was divided into three tertiles: low, medium, and high. Nine food groups were created based on the foods and drinks consumed by pregnant women the day before the survey: cereals and starchy staples; oils and fats; dark green leafy vegetables and vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; legumes; nuts and seeds; other fruits and vegetables; meat and fish; organ meats; milk and dairy products; and eggs. Women who consumed food from each subgroup (at least once) were assigned a score of 1, while those who did not were assigned a score of 0.

2.14.4. Household Food Security

Household food security was assessed using a modified version of the Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance version 3 questionnaire, adapted for the local context. This tool contains 18 questions [

47]. The first nine questions were answered with a "yes" or "no" response, and the results were classified into four categories: food secure, mildly food insecure, moderately insecure, and severely food insecure.

2.14.5. Community-Level Covariates

Community-level covariates included the place of residence (urban or rural), community-level distance to the nearest health facility, community literacy rates among women, social media usage at the community level, and community-level poverty indicators.

2.15. Data Collection Tool and Procedure

The study employed a structured, pretested questionnaire, which was administered by trained interviewers (

S3 File). The questionnaire was adapted from similar studies

[2,12,13,14] and initially written in English. It was then translated into Sidaamu Afoo, the primary language spoken by nearly all study participants. To ensure accuracy and consistency, the translated version was retranslated into English. A bilingual language expert, fluent in both English and Sidaamu Afoo, translated. The principal investigator and an additional language expert reviewed the translated tool. Any discrepancies identified during the review process were corrected to ensure alignment between the two versions.

Data collection post-intervention was conducted using the Open Data Kit mobile application from February 5 to 30, 2025. A team of 12 data collectors and two supervisors managed the process, with the principal investigator overseeing all stages of data collection and adjusting as needed to address any issues that arose.

2.16. Data Quality Assurance

The principal investigator conducted a comprehensive 2-day training session for data collectors and supervisors, focusing on the study tools, study significance, data collection procedures, research objectives, methodologies, and ethical considerations. The data collection process employed a well-designed, standardized, pretested, structured questionnaire, which trained interviewers administered face-to-face. A pre-test of the questionnaire was conducted, and necessary revisions were made before the actual data collection began. Throughout the data collection period, strict supervision was maintained, with daily checks to ensure completeness and consistency of the data. To minimize reporting bias, data collectors were trained to emphasize the importance of understanding the standardized questions and to ensure accurate responses. In parallel, two medical laboratory technicians received specialized training in blood collection techniques, hemoglobin analysis, and the preparation and transport of blood serum to the regional laboratory center for further analysis.

2.17. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were performed to summarize key variables across intervention and control groups. The wealth index was computed using Principal Component Analysis, and the detailed computation procedure is provided in the

S2 File [

47]. The analysis included all women participants enrolled at baseline who consumed at least one serving of amaranth grain bread and had outcome measurements at the end of the intervention. An intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was employed to compare outcomes between the intervention and control groups. Prior to multilevel modeling, the necessity of multilevel analysis was assessed by fitting random intercept models using logistic and linear regression to calculate intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs)

[48,49]. A multilevel model was considered necessary if the ICC exceeded 5%. Both univariable and multivariable analyses were conducted using multilevel mixed-effects modified Poisson regression with robust error variance for iron deficiency anemia, and linear regression for hemoglobin concentration. Baseline characteristics with an important imbalance between the two treatment arms were included in multivariable models to assess the effect of amaranth grain flatbread consumption, adjusting for these differences as potential confounders.

Four hierarchical models were developed: Model 1 (an empty model with random intercepts), Model 2 (adjusted for individual-level factors), Model 3 (adjusted for community-level factors), and Model 4 (adjusted for both individual- and community-level factors). Random effects were evaluated using the ICC value. Model fit was assessed using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the log-likelihood ratio test, with models favoring those with lower values. Interaction terms between the intervention variable and mass media use, wealth quintile, malaria infection, iron-rich food consumption, household food insecurity, dietary diversity, and place of residence were included in the final model to assess potential effect modification. Multicollinearity among independent variables was assessed using multiple linear regression; a variance inflation factor (VIF) of less than 5 indicated an acceptable level of multicollinearity [

49].

The association and strength of relationships between amaranth grain flatbread consumption and outcome variables were expressed as adjusted RRs with 95% CIs for iron deficiency anemia and as adjusted β with 95% CIs for hemoglobin concentration. Statistical significance was noted when the 95% CI of the effect size did not include the null. All statistical analyses were performed using a 95% confidence level and a 5% significance threshold. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26 and Stata 17.

3. Results

3.1. Trial Profile

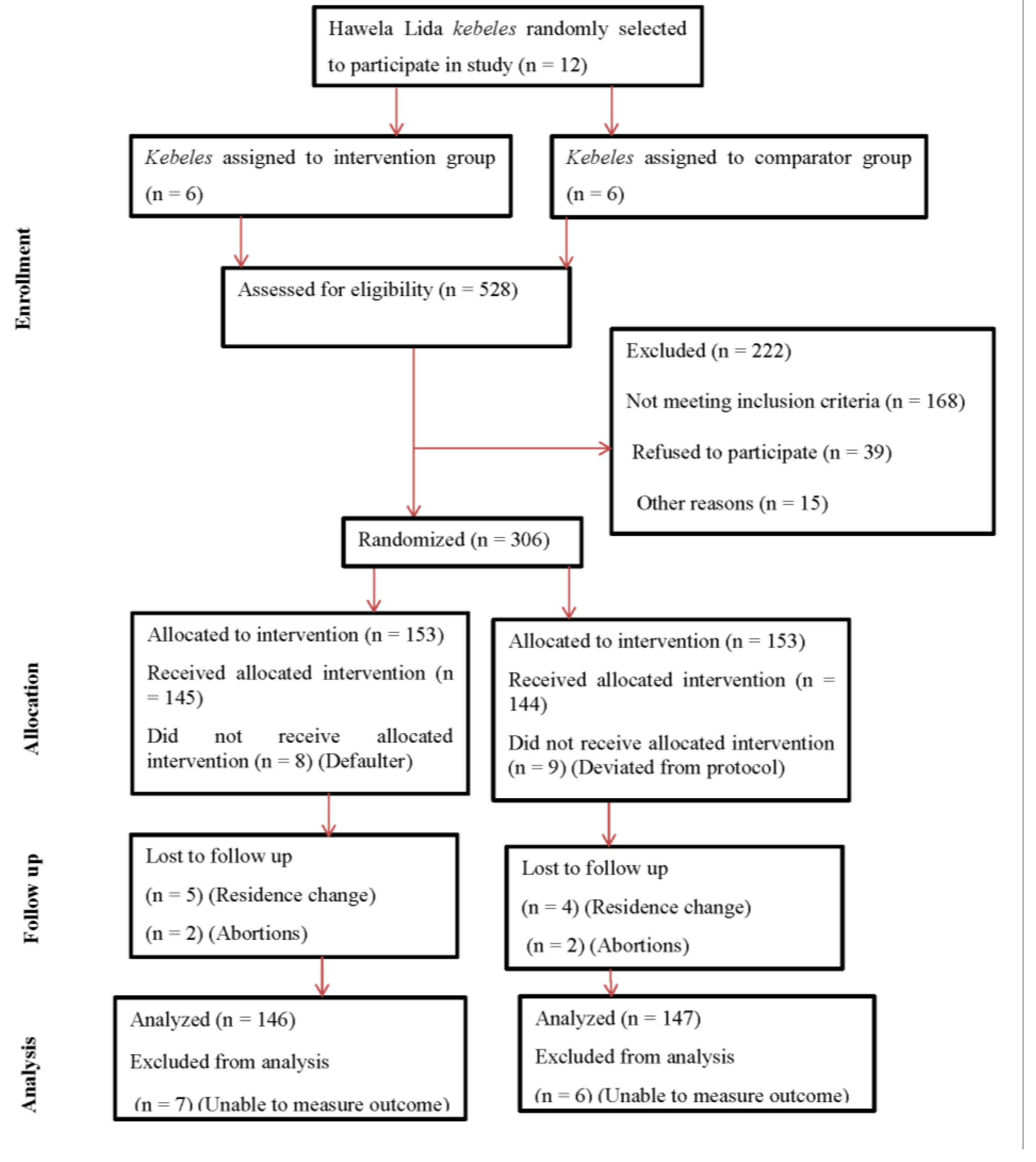

The procedures for recruitment, randomization, and eligibility assessment are detailed in

Figure 1. Between August 1 and 30, 2024, WDT leaders and Health Extension Workers screened 528 pregnant women for eligibility. Of these, 306 women from 10

kebeles met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study, with equal allocation to intervention (n = 153) and control (n = 153) groups. At the time of recruitment, the mean gestational age was 11.02 ± 3.21 weeks. During the outcome assessment period, 293 of 306 participants (95.75%) remained: 146 (95.42%) in the intervention group and 147 (96.07%) in the control group. The overall response rate was 95.75%, with similar follow-up loss in both groups (4.58% vs. 3.93%).

3.2. Participant Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the socio-demographic and economic attributes of the trial subjects. Details of the baseline characteristics of all randomized participants are provided in

S2 File. Overall, the distribution of many characteristics was comparable across the intervention and comparison groups. The majority of participants identified as Sidama ethnicity (96.6%) and were Protestant Christians (88.4%). Nearly all were married (99.0%) and had received formal education (71.7%) at the time of the interview. The mean age of participants was 25.91 years (SD = 4.25) in the intervention group and 25.78 years (SD = 4.55) in the comparison group. Most women in the intervention and comparison groups were housewives, comprising 92.5% and 90.5%, respectively. Government employees represented a small fraction in both groups (3.4% in the intervention group and 2.7% in the comparison group). More than half of the women in the intervention group (69.2%) and just over half in the comparison group (54.2%) reported access to mass media, including radio, television, and newspapers. However, there were important differences in baseline characteristics for the following, which were adjusted for in the analysis: wealth index and mass media use.

3.3. Reproductive and Obstetric Health Characteristics

The reproductive health characteristics were generally similar between the intervention and comparator groups (

Table 2). The mean age at first marriage was 20.65 ± 2.76 years in the intervention group and 21.41 ± 3.38 years in the comparator group. A history of infection during the current pregnancy was reported by 22 women (15.1%) in the intervention group and 26 women (17.7%) in the comparator group. In the intervention arm, 63 women (69.2%) had two to four previous births, compared to 59 women (65.6%) in the comparator arm. Obstetric danger signs were reported by 8% of participants in the intervention group and 9% in the comparator group. In both groups, more than three-quarters of the women stated that their most recent pregnancy was planned (

Table 2). However, there were differences in age at first marriage and age at first pregnancy, which were adjusted for in the analysis.

3.4. Description of the Baseline Hemoglobin Levels and Anemia Status

The intervention and comparison groups were comparable in terms of baseline hemoglobin concentration and iron deficiency anemia, as determined by serum ferritin levels. Among all pregnant women diagnosed with anemia, 108 out of 293 (36.9%) had moderate anemia, while 185 (63.1%) had mild anemia. The proportion of women with moderate anemia was slightly higher in the intervention group (41.1%) compared to the comparison group (32.7%) (

Table 4).

3.5. Effect of Intervention on Hemoglobin Concentration and Iron Deficiency Anemia

In the unadjusted (crude) analysis, the mean hemoglobin concentration was higher in the amaranth group (12.39 g/dL, 95% CI: 12.17–12.61) compared to the maize group (10.17 g/dL, 95% CI: 9.95–10.39). Similarly, the proportion of iron deficiency anemia was lower in the amaranth group, affecting 39 participants (26.71% [95% CI: 20.14–34.49]), compared to 97 participants (65.98% [95% CI: 57.93–73.21]) in the maize group (

Table 5).

After adjusting for potential confounders and accounting for clustering at the community level, pregnant women who received amaranth grain flatbread had higher hemoglobin concentrations compared to those in the maize group. The adjusted mean difference in hemoglobin levels was 2.67 g/dL (adjusted β = 2.67; 95% CI: 2.41–2.90) (

Table 6).

After adjusting for confounders and clustering, pregnant women who received amaranth grain flatbread had a 53% lower risk of IDA compared to those in the maize group (adjusted relative risk, RR = 0.47; 95% confidence interval, CI: 0.26–0.84) (

Table 7).

3.7. Random Effects Model Attributes and Model Fitness Evaluation

The multilevel mixed-effects modified Poisson regression model, incorporating robust variance estimation, demonstrated a significantly better fit than the standard single-level model (p < 0.001). ICCs revealed that 12.6% of the variation in hemoglobin concentrations and 26.7% of the variation in iron deficiency anemia were attributable to clustering at the kebele level, justifying the use of a multilevel modeling approach.

Model fit was assessed using AIC and log-likelihood values. For hemoglobin concentration, the null model exhibited the poorest fit (AIC = 1146.42; log-likelihood = −570.20), while the final adjusted model showed substantial improvement (AIC = 837.45; log-likelihood = −399.73). Similarly, for IDA, model performance improved markedly from the empty model (AIC = 513.36; log-likelihood = −254.68) to the final model (AIC = 471.88; log-likelihood = −226.94). These findings indicate that accounting for individual- and kebele-level factors enhanced the explanatory power and precision of the models. When assessing for potential effect modification, none of the interaction terms were statistically significant, suggesting no effect modification by the stated variables.

3.8. Adverse Events

Throughout the six-month intervention period, no serious adverse events attributable to the intervention were reported in either the amaranth or maize arms. All participants were regularly monitored through biweekly home visits by trained community health workers and monthly follow-ups by field supervisors. Two abortions were reported in the intervention arm and two in the comparator arm. All abortion cases were attributed to external trauma (motorcycle accidents or falls) and, based on assessments by community health workers and field supervisors, were not considered related to the intervention.

A total of 12 participants (7.8%) in the amaranth arm and 9 participants (5.9%) in the maize arm reported minor gastrointestinal symptoms, including transient bloating, abdominal discomfort, or changes in bowel habits. These events were mild and self-limiting, requiring no medical intervention or discontinuation of the intervention.

No allergic reactions or safety-related withdrawals were observed. All adverse events were promptly recorded and reviewed by the study's clinical supervisor.

3.8. Adherence

Of the 306 pregnant women randomized (153 per group), 8 participants in the intervention (amaranth) arm did not receive the allocated intervention due to withdrawal from the study (after receiving at least one serving of flatbread). In the control (maize) arm, 9 participants deviated from the protocol and did not receive the assigned intervention. As a result, 145 participants in the amaranth arm and 144 in the maize arm received all the allocated servings of flatbread.

4. Discussion

This six-month, community-based intervention with amaranth grain flatbread improved hemoglobin concentrations and reduced IDA compared to maize bread among pregnant women with anemia in southern Ethiopia. No serious adverse events were reported. Findings suggest that incorporating amaranth grain into maternal nutrition programs may offer a culturally appropriate and sustainable strategy to combat mild or moderate iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy.

While previous research has explored the nutritional composition of amaranth and techniques for phytate reduction [

28,

29], few studies have assessed its in vivo effects, particularly in the form of flat bread. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Ethiopia to evaluate the impact of amaranth grain flatbread consumption on hemoglobin levels and IDA among pregnant women. Due to the limited availability of directly comparable studies, findings from other populations were referenced as a basis for comparison. A study conducted in Hawassa city among children under five years demonstrated that consumption of homemade amaranth products improved hemoglobin levels and reduced IDA [

27]. Similarly, research from Ghana found that supplementation with dried amaranth leaf powder reduced the prevalence of anemia by 28% and increased hemoglobin concentrations by 8.9 g/L [

50]. The presence of other micronutrients in amaranth, including folic acid, copper, and vitamin A, may have also contributed to the observed improvements in hemoglobin levels [

51,

52,

53]; however, these micronutrients were not measured in either the Ghanaian study or the present trial.

Conversely, a Kenyan study reported that consumption of raw amaranth grain did not reduce anemia rates in preschool children [

21], attributing the lack of effect to the high phytate content, which impairs iron absorption. The authors suggested that reducing phytate content could enhance the nutritional efficacy of the grain. In our study, homemade processing techniques such as soaking, germination, and fermentation were employed, which likely reduced phytate levels and enhanced the bioavailability of iron and other key nutrients, thereby contributing to the positive outcomes observed.

Based on the observed improvements in hemoglobin concentration and reduction in IDA, our findings suggest that amaranth grain can be integrated into maternal nutrition programs in Ethiopia and other similar settings. As a locally available, culturally acceptable, and nutrient-dense crop, amaranth may offer a sustainable solution to address dietary iron deficiency among pregnant women. Future efforts should focus on scaling up community-level production and utilization of amaranth, alongside nutrition education, to promote dietary diversification. Further longitudinal studies and implementation research are warranted to assess the broader impacts on maternal and neonatal health outcomes and to inform policy-level interventions.

This study has several important strengths. First, the research protocol was prospectively registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT06536153), which enhances transparency and helps mitigate the risk of selective reporting bias. Second, the use of a cluster RCT design strengthens causal inference. Participants were selected using simple random sampling, and randomization was applied at the cluster level to allocate pregnant women with anemia into intervention and control groups, minimizing the risk of contamination and strengthening internal validity when assessing this community-based intervention.

Blinding was maintained across multiple levels: bread producers, distributors, caregivers, and data collectors were unaware of the type of bread (maize or amaranth) provided. Furthermore, the daily feeding was implemented under direct supervision, ensuring intervention fidelity. The use of existing community infrastructure, specifically the WDTs, facilitated the delivery and monitoring of the intervention without requiring parallel systems, thereby enhancing both sustainability and scalability. An acceptability assessment for the intervention was also conducted to ensure cultural and contextual appropriateness.

Nonetheless, the study has limitations. It did not assess other potential causes of nutrient-related anemia, such as deficiencies in folic acid, vitamin A, and copper. Additionally, genetic hemoglobinopathies were not evaluated, despite their relatively low prevalence in the study population and setting. Despite efforts to adjust for confounding, residual confounding due to unmeasured variables such as blood-borne parasitic infections cannot be entirely ruled out. Although randomization is designed to distribute confounding variables across study arms evenly, imbalances were observed in several individual- and community-level baseline characteristics. To address these baseline differences, multilevel and multivariable regression models were applied. Missing outcome data presented an additional limitation. Thirteen women were lost to follow-up, nine due to relocation and four due to pregnancy loss (unrelated to the intervention). While randomization can achieve baseline group comparability, differential attrition may introduce bias and compromise the internal validity of the study. However, the extent of attrition was minimal, with loss-to-follow-up rates of 4.58% in the intervention group and 3.93% in the comparator group.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that consumption of amaranth grain flatbread among pregnant women with mild or moderate anemia at baseline improves hemoglobin concentration and reduces iron deficiency anemia compared to a maize-based diet. These findings highlight the nutritional potential of amaranth, an underutilized and locally available grain, in enhancing maternal iron status for pregnant women with mild to moderate anemia in low-resource settings. Integrating amaranth into maternal nutrition programs may represent a culturally acceptable and sustainable strategy for addressing anemia and improving maternal health outcomes in Ethiopia and similar contexts. Informing policy-level action and conducting further longitudinal studies are recommended to evaluate broader maternal and neonatal health benefits of amaranth grain in this population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org S1 file: Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines for cluster RCTs checklist (DOCX);

S2 file: Detail information from methods and results sections (DOCX);

S3 file: English version study questionnaire (DOCX);

S4 file: De-identified Stata dataset, which was authorized to be available by the institutional ethics committee and supported by informed consent from all study participants (dta)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Amanuel Yoseph; Data curation: Amanuel Yoseph; Formal analysis: Amanuel Yoseph; Investigation: Amanuel Yoseph, Lakew Mussie, Mehretu Belayineh; Methodology: Amanuel Yoseph, Lakew Mussie, Mehretu Belayineh; Project administration: Amanuel Yoseph, Lakew Mussie, Mehretu Belayineh; Resources: Amanuel Yoseph; Software: Amanuel Yoseph, Lakew Mussie, Mehretu Belayineh; Supervision: Amanuel Yoseph, Lakew Mussie, Mehretu Belayineh; Validation: Amanuel Yoseph, Lakew Mussie, Mehretu Belayineh; Visualization: Amanuel Yoseph, Lakew Mussie, Mehretu Belayineh, Francisco Guillen-Grima, G. Mutwiri, Jessica J. Wong; Writing – original draft: Amanuel Yoseph, Lakew Mussie, Mehretu Belayineh, Francisco Guillen-Grima, G. Mutwiri, Jessica J. Wong; Writing – review & editing: Amanuel Yoseph, Lakew Mussie, Mehretu Belayineh, Francisco Guillen-Grima, G. Mutwiri, Jessica J. Wong. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript

Funding

This study was supported by the Nestlé Foundation with grant number HUHS/021/2016. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data, the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Medicine and Health Sciences College at Hawassa University, with reference number IRB/027/16.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to the Nestlé Foundation for its generous funding of this study. The support provided was instrumental in enabling the successful execution of the research. We also acknowledge the Sidama Regional Health Bureau and the Hawela Lida District Health Office for their cooperation. Special thanks go to the study participants, data collectors, field assistants, and supervisors for their vital contributions. Lastly, we thank the School of Public Health at Hawassa University for their technical support during the study design and data analysis phases. It is noted that Jessica Wong is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Research Excellence, Diversity, and Independence (REDI) Early Career Transition Award.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIC |

Akaike information criteria |

| ARR |

Adjusted risk ratio |

| CI |

confidence interval |

| LD |

Linear dichroism |

| CRR |

Crude risk ratio |

| ICC |

Intra-class correlation coefficient |

| IDA |

Iron deficiency anemia |

| RCT |

Randomized controlled trial |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| VIF |

Variance inflation factor |

| WDT |

Women development team |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Anemia in women and children. Available online from https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/topics/anaemia_in_women_and_children Accessed on April 2025. 2025.

- CSA, I. Ethiopia demographic and health survey: key indicators report; Central Statistical Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Derso, T.; Abera, Z.; Tariku, A. Magnitude and associated factors of anemia among pregnant women in Dera District: a cross-sectional study in northwest Ethiopia. BMC research notes 2017, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggaz, A.D.; Radi, E.A.; Adam, I. Anaemia and low birthweight in western Sudan. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2010, 104, 234–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, K.; et al. The risks for preterm delivery and low birth weight are independently increased by the severity of maternal anaemia. South African Medical Journal 2009, 99, 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Lebso, M.; Anato, A.; Loha, E. Prevalence of anemia and associated factors among pregnant women in Southern Ethiopia: A community based cross-sectional study. PloS one 2017, 12, e0188783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moench-Pfanner, R.; et al. The economic burden of malnutrition in pregnant women and children under 5 years of age in Cambodia. Nutrients 2016, 8, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Health Organization. Nutritional anaemias: tools for effective prevention and control. 2025. available online https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241513067 Accessed on April 25, 2025.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. National Nutrition Program Multi-sectoral Implementation Guide. Addis Ababa: 2016. http://dataverse.nipn.ephi.gov.et/bitstream/handle/123456789/1029/NNP%20multisectoral%20guideline.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on May 3, 2025).

- MoFED; MoFED. Health sector growth and Transformation Plan (GTP); 2018/19-2024/2025; The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia., 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ayele, S.; Zegeye, E.A.; Nisbett, N. Multi-sectoral nutrition policy and programme design, coordination and implementation in Ethiopia; IDS: Brighton, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goba, E. Prevalence of Iron Deficiency Anemia and Associated Factors among Pregnant Women Attending Antenatal Care Follow up at Dodola General Hospital West Arsi Zone Oromia Region South East Ethiopia. Archives of Medicine 2021, 13, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Laelago, F.; Paulos, W.; Handiso, Y.H. Prevalence and predictors of iron deficiency anemia among pregnant women in Bolosso Bomibe district, Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia Community-based cross-sectional study. Cogent Public Health 2023, 10, 2183562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldegebriel, A.G.; et al. Determinants of anemia in pregnancy: findings from the Ethiopian health and demographic survey. Anemia 2020, 2020, 2902498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desta, M.; et al. Dietary diversity and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal clinic in Shashemane, Oromia, Central Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Journal of nutrition and metabolism 2019, 2019, 3916864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilahun, A.G.; Kebede, A.M. Maternal minimum dietary diversity and associated factors among pregnant women, Southwest Ethiopia, 2021. BMC nutrition 2021, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kebede, A.N.; Sahile, A.T.; Kelile, B.C. Dietary diversity and associated factors among pregnant women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2021. International Journal of Public Health 2022, 67, 1605377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hailu, S.; Woldemichael, B. Dietary diversity and associated factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care at public health facilities in Bale Zone, Southeast Ethiopia. Nutrition and Dietary Supplements, 2019: p. 1-8.

- Ruel, M.T.; et al. Urbanization, food security and nutrition. Nutrition and health in a developing world, 2017: p. 705-735.

- Moss, C.; et al. Sustainable Undernutrition Reduction in Ethiopia (SURE) evaluation study: a protocol to evaluate impact, process and context of a large-scale integrated health and agriculture programme to improve complementary feeding in Ethiopia. BMJ open 2018, 8, e022028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macharia-Mutie, C.W.; et al. Maize porridge enriched with a micronutrient powder containing low-dose iron as NaFeEDTA but not amaranth grain flour reduces anemia and iron deficiency in Kenyan preschool children. The Journal of nutrition 2012, 142, 1756–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muyonga, J.H.; et al. Efforts to promote amaranth production and consumption in Uganda to fight malnutrition. Using food and technology to improve nutrition and promote national development, 2008: p. 1-10.

- Aguilar, E.G.; et al. Evaluation of the nutritional quality of the grain protein of new amaranths varieties. Plant foods for human nutrition 2015, 70, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akin-Idowu, P.E.; et al. Assessment of the protein quality of twenty nine grain amaranth (Amaranthus spp. L.) accessions using amino acid analysis and one-dimensional electrophoresis. African Journal of Biotechnology 2013, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim Rose-Francis and Zawn Villines, Kim Rose-Francis and Zawn Villines. What to know about amaranth. Available online from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/amaranth Accessed on April 26, 2023.

- Laura Dolson, Laura Dolson. Amaranth Nutrition Facts and Health Benefits. Available online from https://www.verywellfit.com/amaranth-nutrition-carbs-and-calories-2241587 Accessed on April 26, 2025.

- Orsango, A.Z.; et al. Efficacy of processed amaranth-containing bread compared to maize bread on hemoglobin, anemia and iron deficiency anemia prevalence among two-to-five year-old anemic children in Southern Ethiopia: A cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0239192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amare, E.; et al. Effect of popping and fermentation on proximate composition, minerals and absorption inhibitors, and mineral bioavailability of Amaranthus caudatus grain cultivated in Ethiopia. Journal of food science and technology 2016, 53, 2987–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zebdewos, A.; et al. Formulation of complementary food using amaranth, chickpea and maize improves iron, calcium and zinc content. African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development 2015, 15, 10290–10304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.K.; Elbourne, D.R.; Altman, D.G. CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. Bmj 2004, 328, 702–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sidama regional health bureau, Annual regional health and health related reports and performance review. Hawassa, Ethiopia. Unpublished report. . 2024.

- Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF, Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019: Final Report; EPHI and ICF: Rockville, Maryland, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hemming, K.; et al. How to design efficient cluster randomised trials. bmj 2017, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donner, A.; Birkett, N.; Buck, C. Randomization by cluster: sample size requirements and analysis. American journal of epidemiology 1981, 114, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killip, S.; Mahfoud, Z.; Pearce, K. What is an intracluster correlation coefficient? Crucial concepts for primary care researchers. The Annals of Family Medicine 2004, 2, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, R.J.; Moulton, L.H. Cluster randomised trials. 2017: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Rutterford, C.; Copas, A.; Eldridge, S. Methods for sample size determination in cluster randomized trials. International journal of epidemiology 2015, 44, 1051–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassore, D.G.; Desalegn, B.B. Formulation of flat bread (Kitta) from Maize (Zea Mays Linaeus.) and Amaranth (Amaranthus Caudatus L.): Evaluation of physico-chemical properties, nutritional, sensory and keeping quality. International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering 2017, 7, 125–131. [Google Scholar]

- Gimplinger, D.; et al. Yield and quality of grain amaranth (Amaranthus sp.) in Eastern Austria. Plant Soil and Environment 2007, 53, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemayehu, D.; et al. Proximate, mineral composition and sensory acceptability of home-made noodles from stinging nettle (Urtica simensis) leaves and wheat flour blends. International Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Engineering 2016, 6, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- World health organization. World health organization. Hemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System; World Health Organization (WHO/NMH/NHD/ MNM/11.1): Geneva, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead Jr, R.D.; et al. Methods and analyzers for hemoglobin measurement in clinical laboratories and field settings. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2019, 1450, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collier, H.B. Standardization of blood haemoglobin determinations. Canadian Medical Association Journal 1944, 50, 550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- WHO. Serum ferritin concentrations for the assessment of iron status and iron deficiency in populations; WHO/NMH/NHD/MNM/11.2; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yoseph, A.; Mussie, L.; Belayneh, M. Individual, household, and community-level determinants of undernutrition among pregnant women in the northern zone of the Sidama region, Ethiopia: A multilevel modified Poisson regression analysis. PloS one 2024, 19, e0315681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, G.; Ballard, T.; Dop, M. Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity. 2011: FAO.

- Coates, J.; Swindale, A.; Bilinsky, P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of food access: indicator guide: version 3. 2007.

- Kleiman, E. Understanding and analyzing multilevel data from real-time monitoring studies: An easily-accessible tutorial using R. 2017.

- Yoseph, A.; et al. Individual-and community-level determinants of maternal health service utilization in southern Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. Women's Health 2023, 19, 17455057231218195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egbi, G.; et al. Effect of green leafy vegetables powder on anaemia and vitamin-A status of Ghanaian school children. BMC nutrition 2018, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mekhlafi, H.M.; et al. Effects of vitamin A supplementation on iron status indices and iron deficiency anaemia: a randomized controlled trial. Nutrients 2013, 6, 190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fishman, S.M.; Christian, P.; West, K.P., Jr. The role of vitamins in the prevention and control of anaemia. Public health nutrition 2000, 3, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wazir, S.M.; Ghobrial, I. Copper deficiency, a new triad: anemia, leucopenia, and myeloneuropathy. Journal of community hospital internal medicine perspectives 2017, 7, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).