1. Introduction

The terms "Priority pollutants" or "contaminants of concern" (CECs) have broad definitions varying according to the source. While the 1976 EPA Clean Water Act focuses specifically on 13 metals (including arsenic, cadmium, mercury, etc.) and 114 organic compounds [

1], others broaden the definition to any potentially hazardous substance observed in the environment (including personal care products and pharmaceuticals) that can pose significant threats to human health and the environment [

2,

3]. Thus, a broad spectrum of such pollutants have been found in both surface and groundwater, including pesticides, pharmaceuticals (including iodinated X-ray contrast media), life-style” and personal care compounds (as caffeine and nicotine), industrial and water treatment by-products, food additives (as parabens and sweeteners), flame retardants and even novel artificial nanomaterials (as quantum dots, dendrimers and nanocomposites) [

4].

During the last few years, several publications have reviewed methods for the efficient removal of such contaminants. While some of those studies review, report, and in some cases compare techniques based on different approaches [

5,

6,

7,

8] others focus on specific approaches. Those include biological processes, such as membrane bioreactors [

9], adsorption on specifically tailored sorbents [

10,

11,

12,

13], or advanced oxidation processes [

14,

15,

16].

Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) are considered a very promising and effective set of techniques based on the

in situ formation of highly oxidating agents, such as hydroxyl, hydroperoxyl, and superoxide radicals [

17,

18,

19], aiming complete mineralization of toxins, contaminants of emerging concern, pesticides, and other priority contaminants [

20]. However, although such methods are widely used in some specific cases, such as ozone or UV disinfection systems, and some limited UV/H

2O

2 devices, such as TrojanUVPhox 72AL75 reactor [

21] or Fenton based applications, more advanced AOP variants remain largely in research and development phases. When focusing on devices based on photocatalytic processes using photocatalytic nanomaterials, there are severe challenges that must be addressed, as reduced performance in complex natural water sources, separation of the catalysts in a slurry system, or mass transfer limitations in immobilized photocatalyst membranes [

22]. All those challenges lead to the fact that even though there are hundreds of reports on "laboratory successes" on photocatalytic water treatment devices, there are only a few units that have seen commercialization [

23], as Purifics Photo-Cat device [

24].

In a previous study, we presented a laboratory-scale slurry-type continuous-flow device for the photocatalytic degradation of priority pollutants [

25,

26]. The device was tested with synthetic hectorite (SHCa-1) or catalytic grade nanoparticles of TiO

2 on several pollutants (dyes, phenols, and pharmaceuticals) and exhibited efficient performance. However, that study was not tested on "real" water, but based only on "synthetic" water systems and at relatively high pollutant concentrations (1-2 mg L

-1).

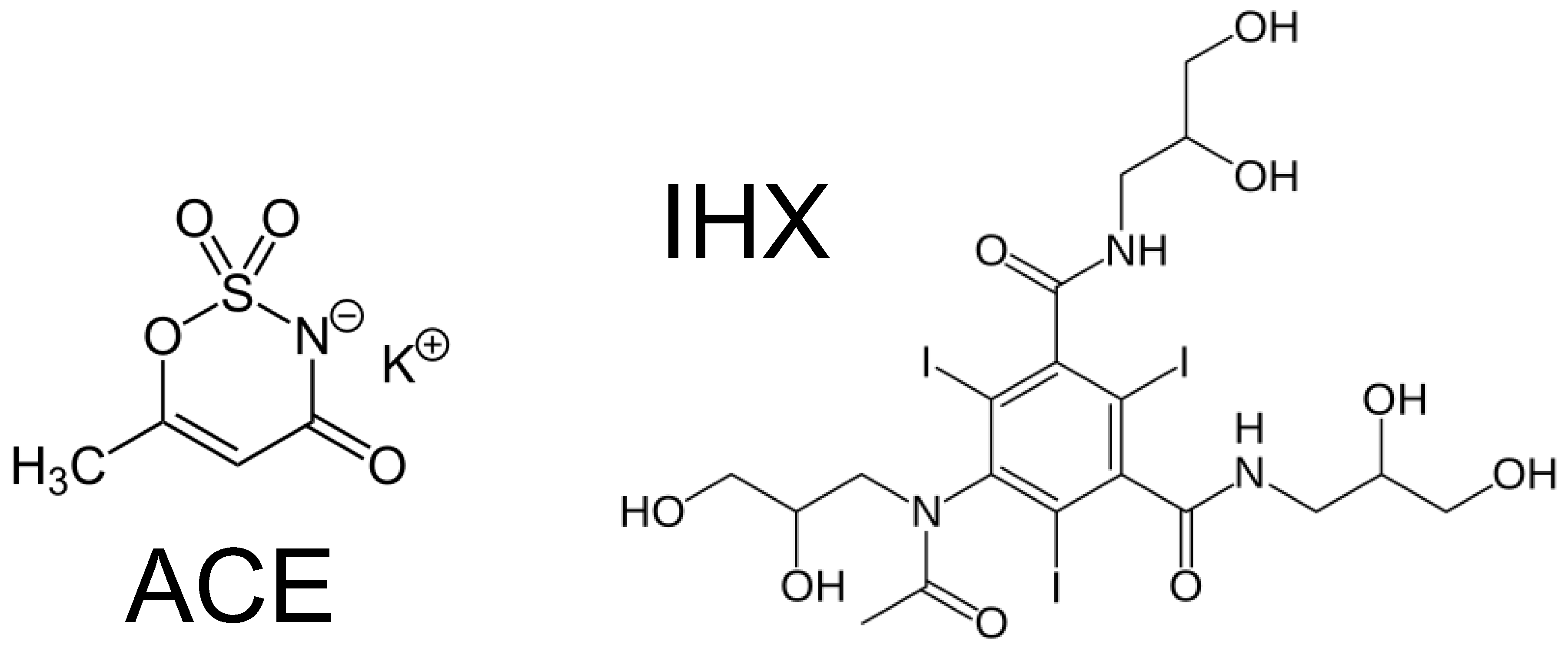

Acesulfame (Potassium 6-methyl-2,2-dioxo-2

H-1,2

λ6,3-oxathiazin-4-olate, ACE,

Figure 1) is an artificial sweetener considered as a sewer tracer in aquatic environments [

27] since it is only partially degraded in regular wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) [

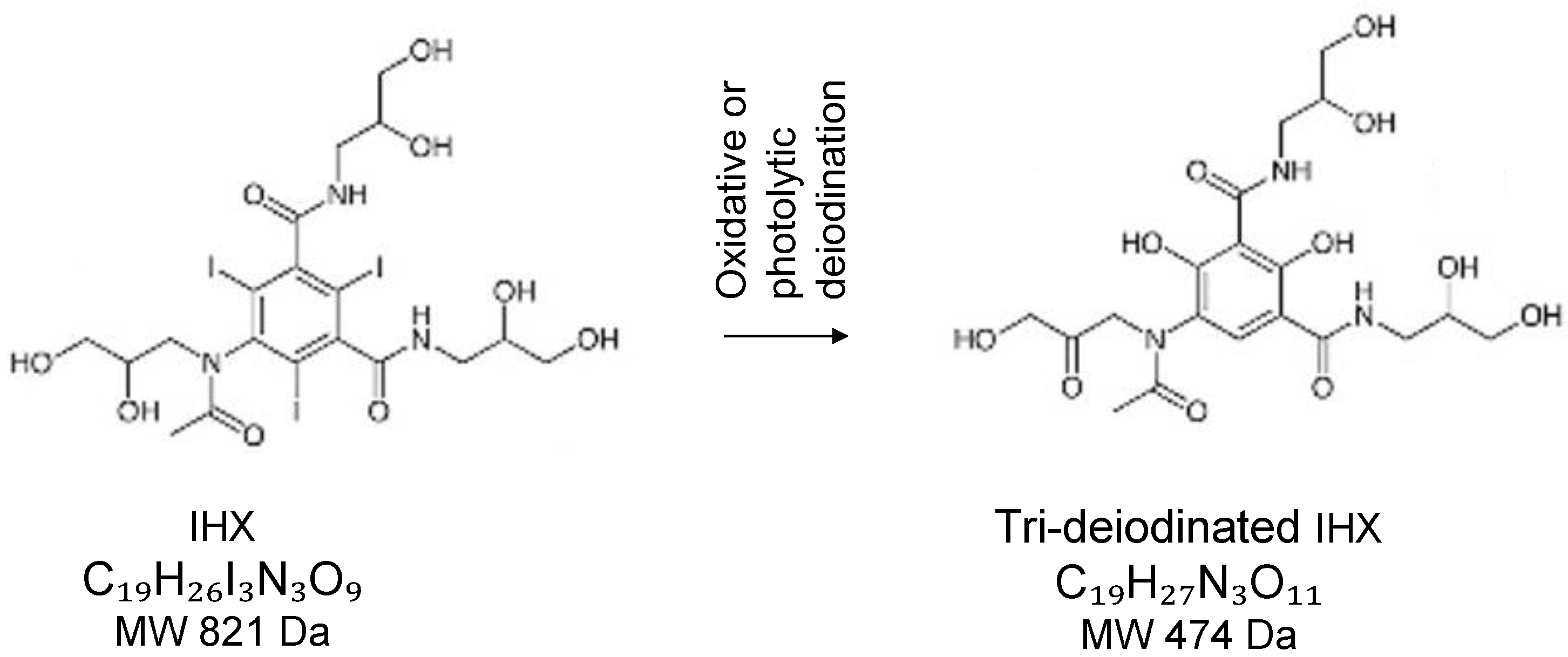

28]. Iohexol (5-[N-(2,3-Dihydroxypropyl)acetamido]-2,4,6-triiodo-N,N′-bis(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)isophthalamide, IHX, Fig. 1) is a non-biodegradable iodinated X-ray contrast media [

29] which was found at relatively high concentrations in several water sources around the world [

30,

31]. Although both pollutants’ degradation by AOPs was studied [

27,

29,

32,

33], all known reports were performed on batch experiments, and there are no reports on such studies in flowing through systems.

Figure 1.

Acesulfame (ACE) and iohexol (IHX) chemical structure.

Figure 1.

Acesulfame (ACE) and iohexol (IHX) chemical structure.

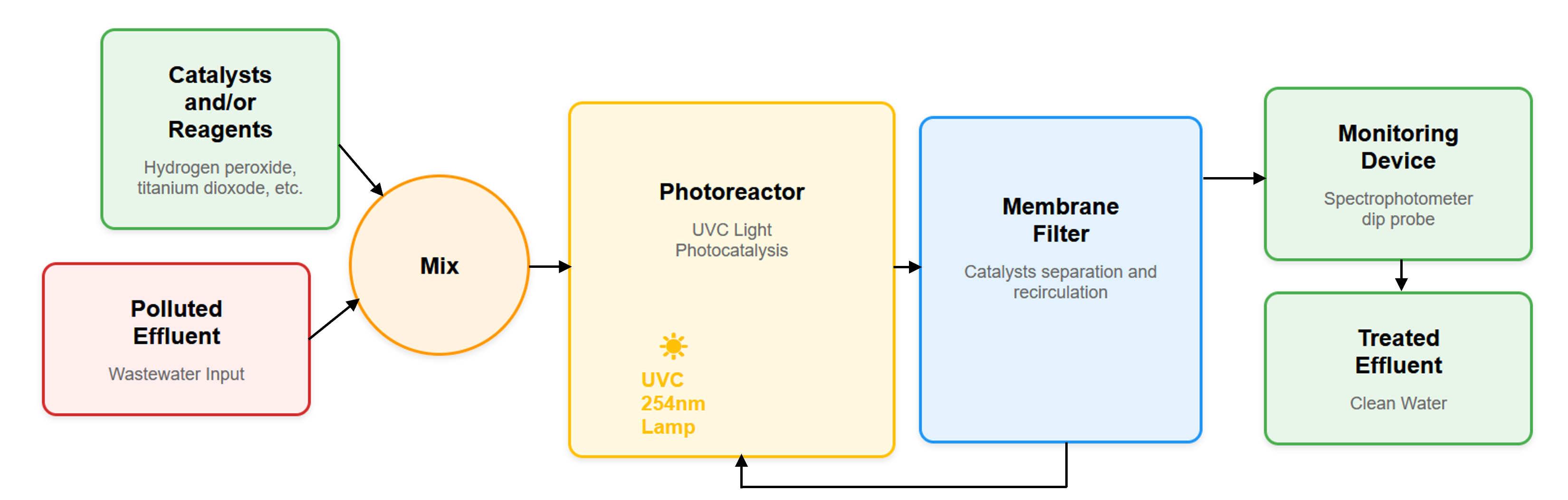

In this study, we present an upscaled device that can combine several AOP processes, including a slurry-type system of nano-photocatalysts, ozone, and/or hydrogen peroxide, combined with a UV lamp. Specifically, results presented focus on a UV/H2O2 combination, and were tested for the complete removal of low concentrations of acesulfame and iohexol in tertiary effluents from a large WWTP.

2. Results

2.1. Flow Through Device for Photocatalytic Degradation

2.2. Preliminary Experiments

As described in subsection 4.2.1, 0.5 mg L

-1 concentrations of ACE or IHX were allowed to flow at a 2.7 L h

-1 flow rate without turning on the UVC system or adding any additional reagents to confirm that there are no considerable sinks of pollutants due to their adsorption to pipes, filter membranes or other parts of the device. The results (shown in

Figure S1 of the Supplementary Materials) indicate that at the first minute, there is a steep decrease in the measured concentrations of both ACE and IHX (C/C

0 of 0.62 and 0.70, respectively). Still, after 8 minutes, values increase considerably (C/C0 of 0.76 and 0.92 for ACE and IHX, respectively), and after 20 minutes, the system reaches equilibrium with C/C

0 close to 1.0.

2.3. Photodegradation Experiments in Synthetic Effluents

A detailed description of the procedure is provided in

subsection 4.2.2.

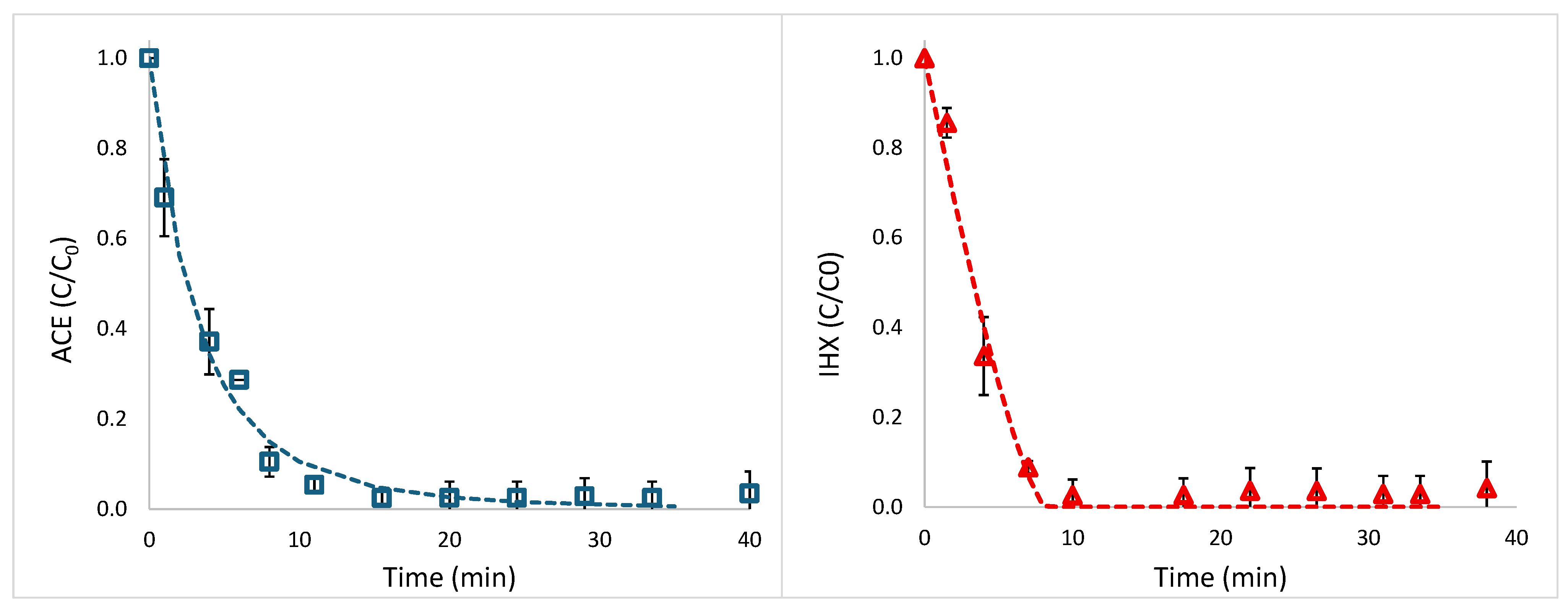

Figure 4 exhibits the photodegradation of ACE (without addition of H

2O

2) and IHX, with the injection of H

2O

2. Points indicate measured results, with standard deviation between the separated experiments, while the lines indicate the evaluated amounts based on the pseudo-order evaluation model [

34], briefly described in

subsection 4.2.2.

As can be seen, complete degradation of IHX is achieved after approximately 8 min, with a pseudo-order of 0.25 and t1/2=3.27±0.39 min. ACE almost complete degradation is observed only after approximately 20 min, with a pseudo-order of 1.27 and t1/2=2.35±0.84 min. Since in priority trace pollutants we are usually interested in almost complete removal, it is worth defining the evaluated time until 95% of the pollutant is removed (t95%). For IHX t95%=7.23±1.21 min, whereas for ACE t95%=14.88±2.02 min, however, it should be noted that the process on IHX included the injection of H2O2 while ACE degradation was based only on photolysis, without any extra reagent or catalyst. The fit between measured and evaluated value is good (R2 of 0.989 for both ACE and IHX).

2.4. Photodegradation Experiments in Shafdan WWTP Effluents

2.4.1. Degradation of Pollutants on Tertiary Treatment Effluents

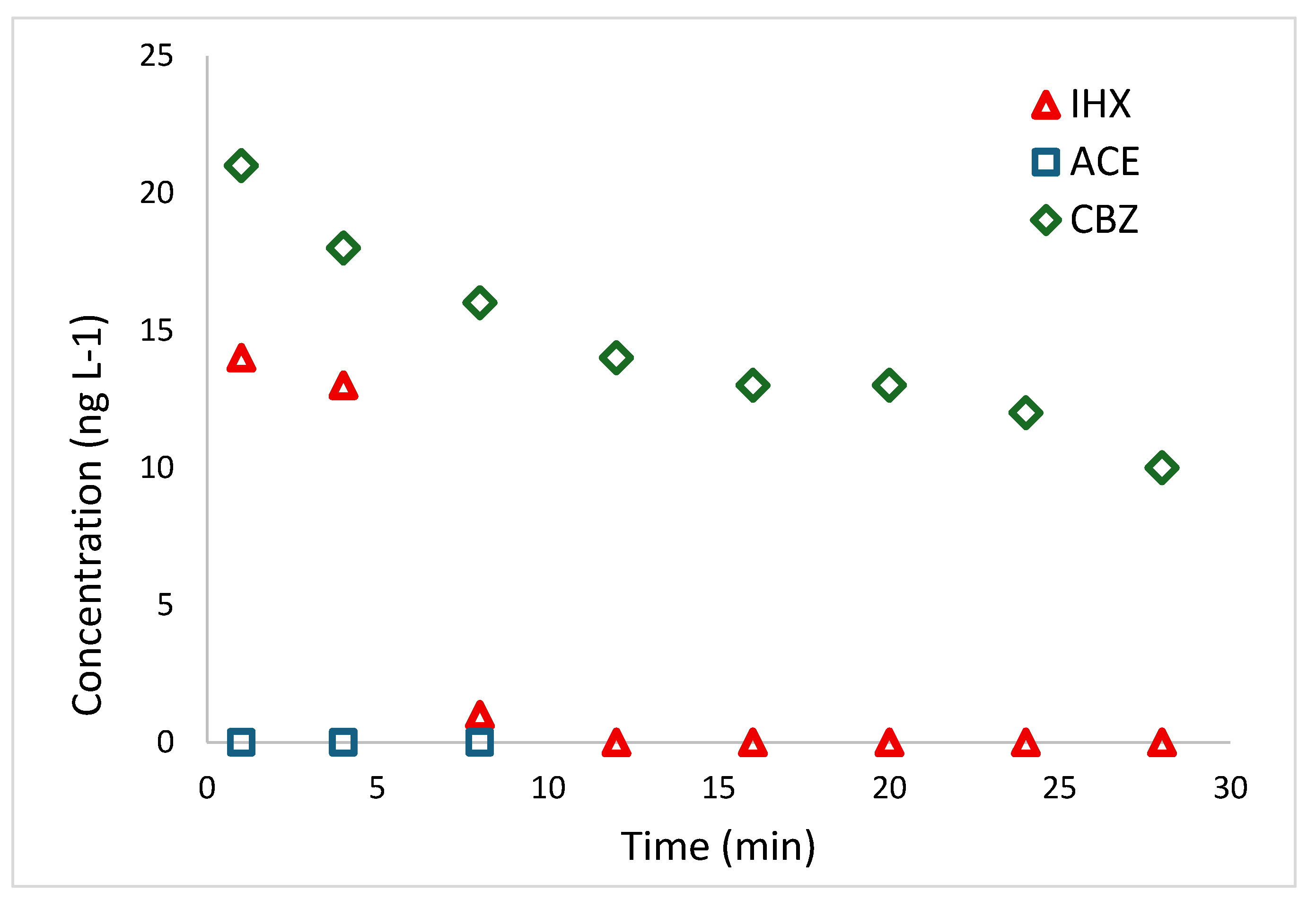

The first experiment was performed directly on the tertiary treatment stage effluents of the largest WWTP in Israel, before disinfection and chlorination, with the addition of 75 μM H

2O

2, as described in

subsection 4.2.3.

Figure 5 shows that the initial concentration of ACE in the effluents is below the limit of detection of the LC-MS, while the initial concentration of IHX is 14 μg L

-1. Carbamazepine (CBZ)- an antiepileptic drug found as contaminant in many WWTP effluents [

35] was added as a comparison, with an initial concentration of 21 μg L

-1.

Interestingly, while degradation of IHX is very fast, and after 8 min, its concentration is reduced to zero, CBZ degradation is slower. Previous studies on the UVC/ H

2O

2 CBZ degradation report efficient and fast processes [

35,

36], but this happened with H

2O

2 concentrations 50-100 fold larger than those used in our study (5000-20000 μM). In most cases, efficient and fast AOPs for the degradation of CBZ are based on heterogeneous catalysts [

37,

38], thus, it is not surprising that the removal under the conditions of this study- is relatively slow: evaluations performed using the pseudo-order method yield a pseudo-order of 2.84, t

1/2=26.5 min, and t

95%=4484 min (more than 74 h). Although it is obvious that exact results depend on full conditions of the system, including UVC intensity, adding a combination of low concentrations of H

2O

2 with mineral catalysts, such as TiO

2 or clay minerals, lowers half life time of degradation to less than 6 min [

12].

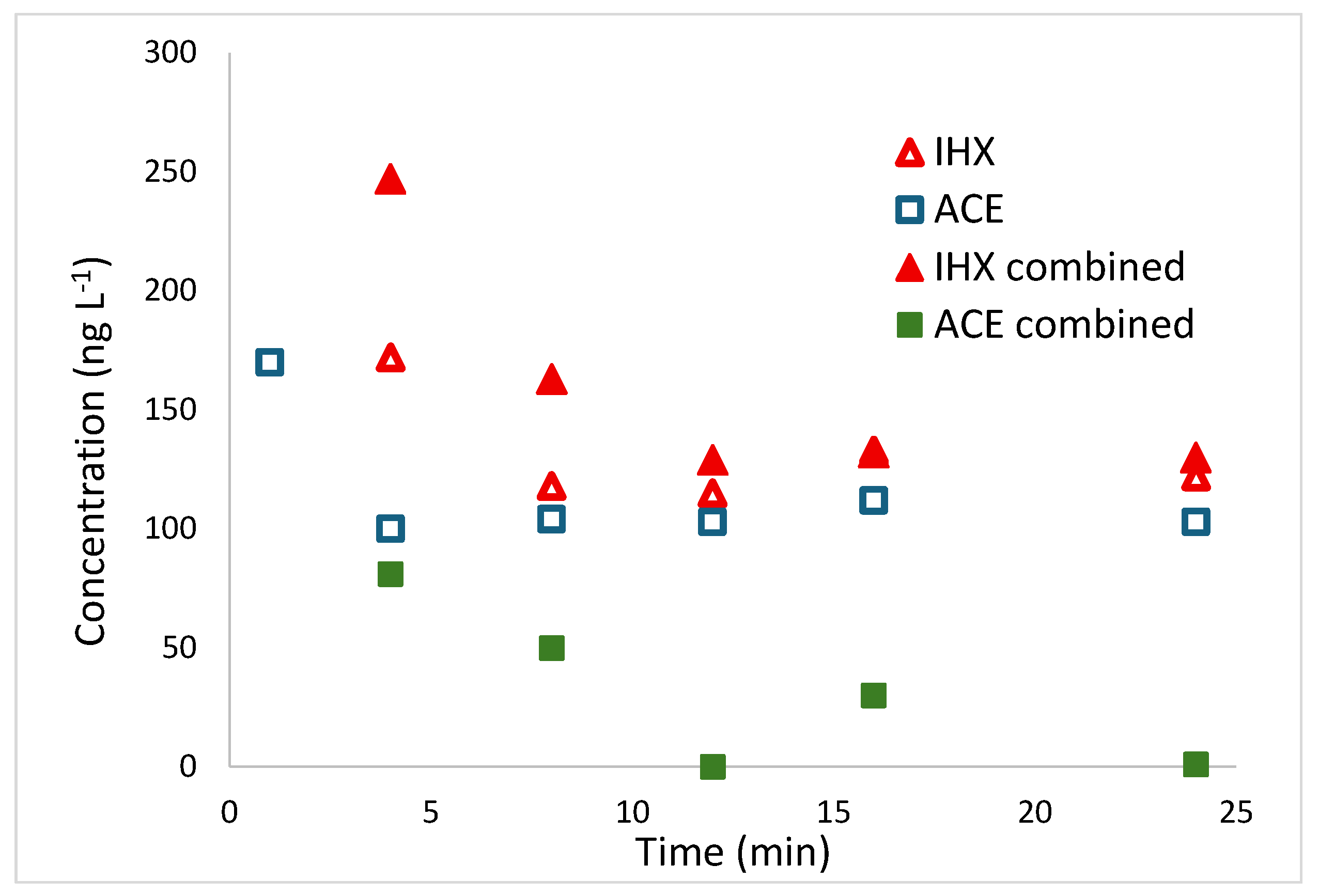

2.4.2. Degradation on Tertiary Treatment Effluents with IHX and ACE Spiking

To estimate the efficiency of the device in effluents containing high concentrations of pollutants (for example, such as those coming from industrial sources) in a background of real, non-synthetic effluents, we tested the efficiency of the device by adding to Shafdan WWTP effluents 1000 μg L

-1 of ACE and IHX, separately, and together.

Figure 6 shows the results of the spiking experiments (separated or combined pollutants) as described in

subsection 4.2.3.

The y-axis of Fig. 6 does not show the initial concentration (1000 μg L

-1 for all the samples) to better distinguish the degradation efficacy after a few minutes. It can be seen that for IHX, the results are similar when added alone or combined with ACE. No complete removal is achieved, and there are remains of approximately 130 μg L

-1 even after 25 minutes. For ACE, a similar behavior is observed when added alone, but when combined with IHX, complete ACE removal is observed after 12 min. The total ACE removal is probably due to interactions between the pollutants that might enhance the degradation of the more easily degraded chemical. The fact that IHX remains, leading to ineffective removal, might indicate that the process follows a higher order. As mentioned in previous papers, higher degradation orders are effective at high pollutant levels, but relatively inefficient at low pollutants’ concentrations [

34].

2.5. Possible Photodegradation by-Products

The procedure to detect and monitor possible photodegradation by-products is described in

subsection 4.3.2. It should be emphasized that no significant traces of such products were found. However, Compound Discoverer 3.1 (Thermo Xcalibur, Version 3.3.0.305) software enables estimation of possible intermediates.

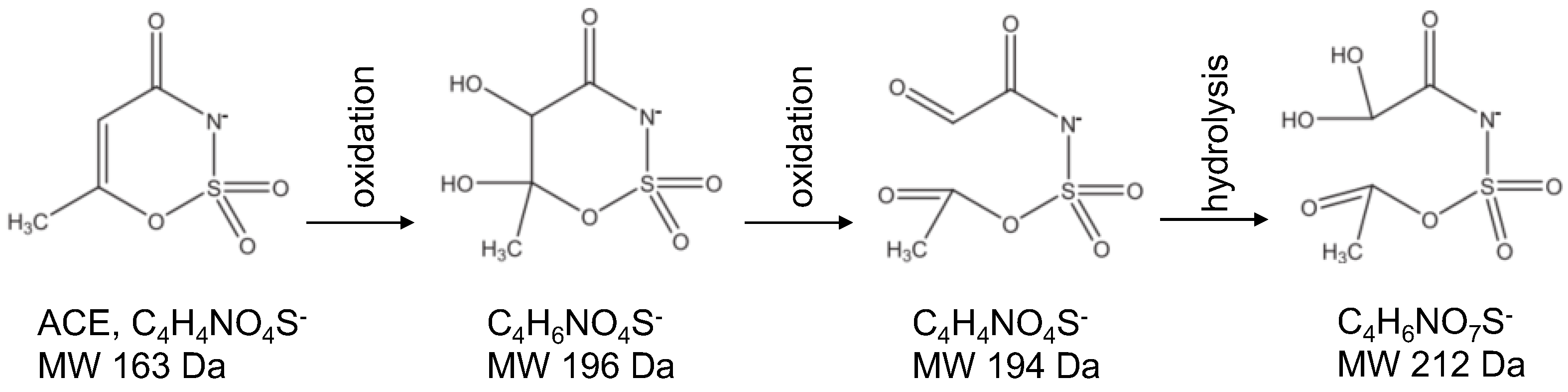

2.5.1. ACE possible Photodegradation by-Products

Several studies have investigated ACE degradation through different UV-based AOP processes, including direct solar [

39] or LED-UVC photolysis at different wavelengths [

32], UV/persulfate [

33] and UV/hydrogen peroxide[

32,

40]. While Wang et al. [

32] suggest a series of possible by-products with molecular weights ranging between 148.9-222.2 Da, our LCMS software does not suggest such chemicals, but it does suggest products with 194 and 212 Da molecular weights. Interestingly, such by-products are also mentioned by Xue et al.[

33]: while the first one occurs after two steps of oxidation (see

Figure 7), the second is formed by an additional step of hydrolysis.

2.5.2. IHX Possible Photodegradation By-Products

The degradation of IHX by different AOPs was also widely studied. In a recent paper, ozonation has been found inefficient, since only partial degradation was achieved, and byproducts "were mostly similar to their parent compounds in their persistence, stability and toxicity" and some of them " were found to be even more toxic than their parent compounds" [

41]. Degradation based on electro-enhanced activation involved deiodination, amide hydrolysis, and/or oxidation, C-OH oxidation, the addition of –OH, hydrogen abstraction, and elimination reactions, while most of the byproducts were not harmful for fish, daphnia, and algae [

42]. Hu et al. [

43] describe details on the kinetics of the UV IHX oxidation, but also mention that the amount of toxic CHI

3 (iodoform) increased through the process. A recent study that tested LED UV photodegradation at different wavelengths detected seven different transformation products and concluded that "overall toxicity increased after UV-LED photolysis, posing a considerable risk that requires careful attention" [

44]. When focusing on UV/H

2O

2 processes as the one used in our device, Giannakis et al. [

29] describe 13 byproducts with molecular masses ranging between 444-712 Da. after 5 min, whereas only three byproducts (ranging between 514-653 Da.) after 15 min. Our evaluations of IHX byproducts indeed show the presence of a tri-deiodinated iohexol (C₁₉H₂₇N₃O₁₁) with a molecular weight of 474.1726 Da, where the 2,4,6-triiodophenyl ring becomes a benzene ring with hydroxylated and acetamido side chains intact (

Figure 8). Such structure is indeed one of the options described in the previous study [

29] as a possible degradation by-product after 5 min in a UV/H

2O

2 processes, and also after 15 min of UV photolysis. A detailed degradation path suggested by Copilot AI (Microsoft, 2025) is attached as in

Scheme S1 of the Supplementary Material.

3. Discussion

There are not enough reports on AOP removal of pollutants in flow-through devices. In the end, operational devices should be such that the polluted effluents flow through a system and are removed along the way. This study presents a relatively easy-to-construct system that might be used for such experiments and even be adapted to field case studies. The fact that all parts are commercially available (see

subsection 4.1) makes it affordable and enables its adaptation to different conditions, depending on the system. The possible combination of different AOP agents (H

2O

2, mineral catalysts such as TiO2, ozone) can be advantageous when dealing with more persistent pollutants.

At first sight, this study (as several studies before) tests the degradation of two pollutants at a range of concentrations that is way above those found in water sources or WWTPs effluents. However,

Figure 5 shows that degradation is fast and complete at least for IHX in real effluents, at actual concentrations found in a large WWTP in Israel. On the other hand, this experiment also shows that in some cases (for example, CBZ), additional AOP agents might be required.

The last experiment, performed with spiked WWTP effluents, also exhibits possible limitations of such AOP processes: On one hand fast process that lowers the concentration of pollutants for one order of magnitude (from 1000 to 100 μg L-1) in a few minutes but following that- high order processes seem to be ineffective at lower concentrations.

As for the degradation byproducts, our study does not deliver new information, but presents possible byproducts already mentioned in previous studies. Additional detailed LC-MS /MS measurements are required to determine if toxic degradation byproducts remain after the process, as was reported in several prior studies. Additional experiments based on such a device will be performed to test more persistent priority pollutants, at a wide range of concentrations and conditions, by employing other AOP agents, such as TiO2 or similar solid catalysts, to exploit the combination of homo- and heterogeneous catalytic processes.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Description of the Device

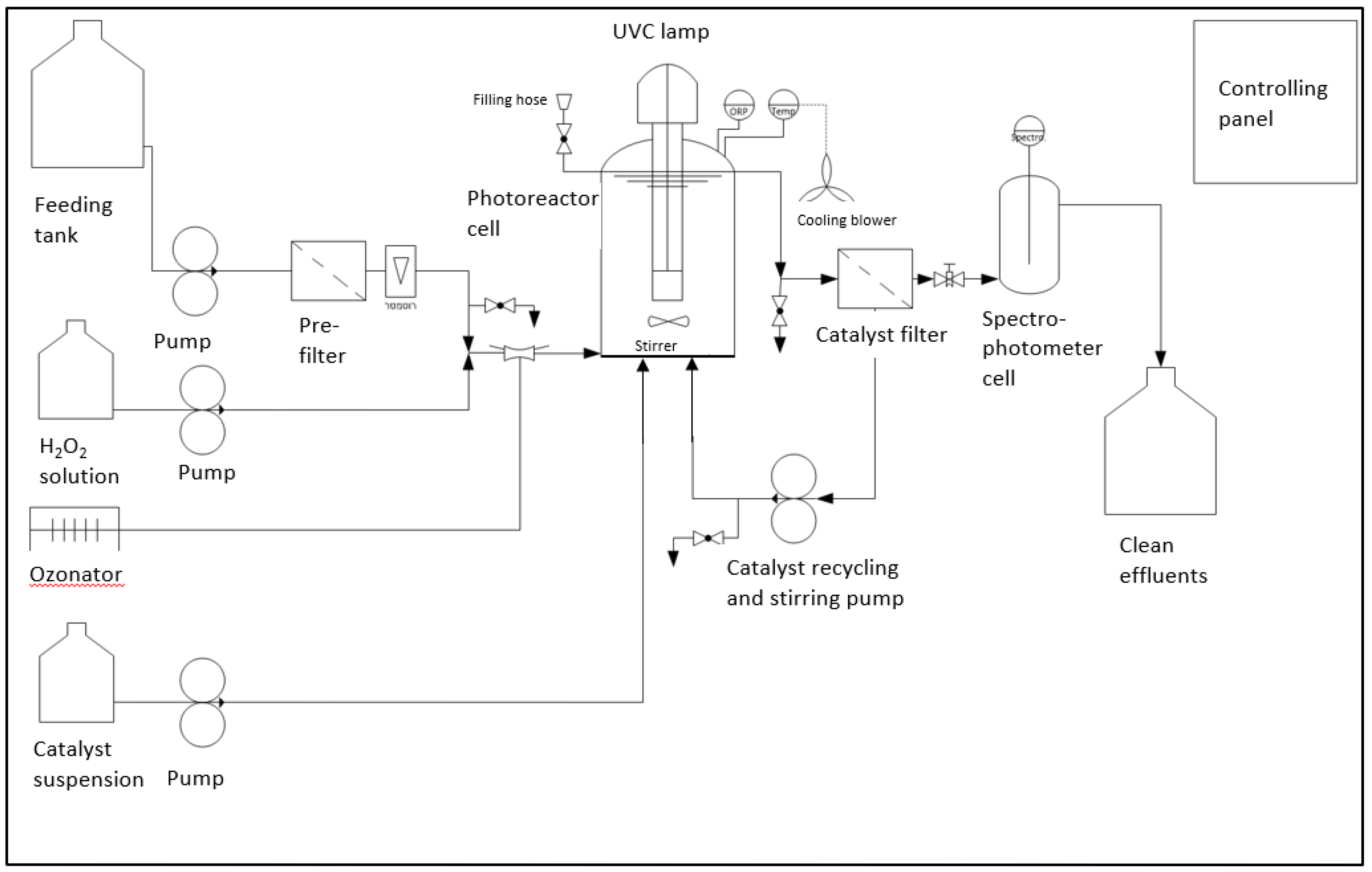

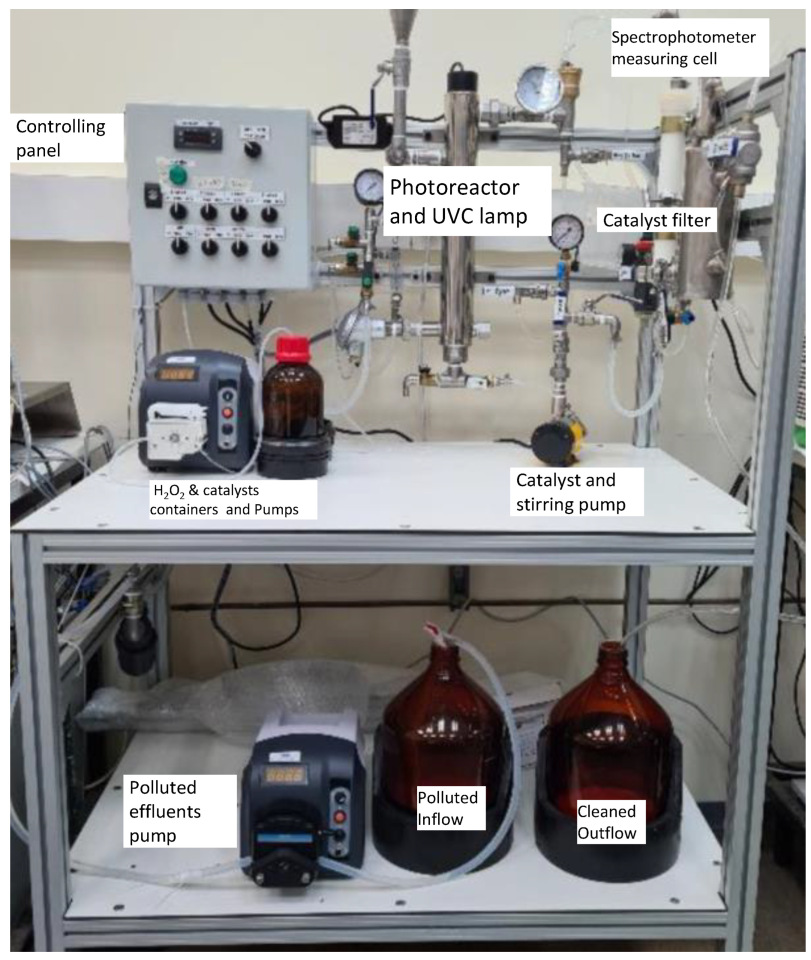

The slurry-type continuous-flow device for photocatalytic degradation of priority pollutants (see Fig.1) is an upscale of a previously presented lab-scale device [

25,

26]. The core of the system is the photoreactor ("Photoreactor cell" or "Photoreactor and UVC lamp" in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, respectively) based on an AMD-UV-21 disinfection module (Zalion Ltd., Bat Yam, Israel), with a nominal flow rate of up to 13.6 L h

-1, a UVC 254 nm lamp of 21 W, with a light intensity of 15.2 mW cm

-2. The polluted effluent is pumped from the "Feeding tank" using a peristaltic PP-X-575 peristaltic pump (MRC laboratory instruments, Holon, Israel) with a YZ1515X head and an S-18 tube, enabling rate flows of up to 35 L h

-1 [

45]. Hydrogen peroxide and catalysts suspension might be injected directly into the photoreactor by two separated PP-X-576 MRC peristaltic pumps (flow rate 300-3000 μL h

-1) that can be operated simultaneously or separately, depending on the conditions required. An ozonator (not installed in this device) might also be added. Following the photoreactor, the treated effluents pass through a 2 m

2 polysulfone NUF® membrane (NUF Filtration, Caesarea, Israel) with a maximum flow rate of 150 L h

-1 and an absolute filtration rate of 30 nm ("Catalyst filter",

Figure 1). NUF filtration technology, originally developed for hemodialysis [

46] allows recirculation of the solid catalysts to the photoreactor ("Catalyst recycling and stirring pump",

Figure 1), using an NH-1PX-Z magnetic drive, centrifugal pump (March May Ltd., Cambridgeshire, UK). The cleaned outflow passes through a DP400 dip probe cuvette connected to a Black Comet SR spectrophotometer using the SpectraWiz software (StellarNet Inc., Tampa, FL, USA), allowing real-time monitoring of the UV-Visible spectrum of the cleaned effluents.

4.2. ACE and IHX Photodegradation Experiments

Analytical ACE, IHX, and a 30% (9.79 M) concentrated H2O2 solution were obtained from Merck/Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Stock solutions of 1 mg L-1 of both pollutants were prepared and kept in dark large bottles at room temperature (23±1C◦). Experiments were performed by pumping pollutants at concentrations ranging between 0.15-0.5 mg L-1 at 25 RPM (equivalent to a rate flow of 2.27 L h-1).

4.2.1. Preliminary Evaluation of the System

To avoid biases due to possible adsorption of the pollutants to the pipes and membranes, a preliminary estimate of the performance of the system was done by running a 0.5 mg L-1 solution of each pollutant through the system, without activating the UVC lamp or adding any additional reagent.

4.2.2. Photodegradation Experiments in Synthetic Effluents

Since preliminary experiments and literature indicated that ACE undergoes photolysis under UVC radiation without any additional reagent [

32], experiments with ACE did not included addition of H

2O

2, while in the experiments with IHX H

2O

2 was injected to achieve an inflow concentration of 75 μM (2.55 mg L

-1). Remaining pollutants concentrations were measured by HPLC, and samples were also measured by LCMS-MS to suggest and even monitor possible degradation by-products. Measured amounts of remaining pollutants were evaluated as the relative remaining concentrations (C/C

0), and the average of three different experiments was calculated. To assess the efficiency of the processes, calculations of the half-life time were done based on the "pseudo-order method" extensively described by Rytwo and Zelkind [

34]. Briefly, pseudo-order kinetic models are based on the integration of the simplified rate law [

47,

48]

where

is the reaction rate,

ka is the apparent rate coefficient, and

na is the apparent or “pseudo” reaction order. Simple integration of Equation (1) (as long as n

a ≠ 1) yields:

To relatively objectively compare efficiency of processes, “half-life time” (t

1/2) can be calculated by solving Equations (2) for the case where the concentration is half of its initial value, thus [A]

(t) = 0.5, yielding:

Considering that in priority trace pollutants the goal is almost complete removal, it is worth defining the evaluated time until 95% of the pollutant is removed (t

95%), as:

Specific adaptation to Eqs. (2) and (3) for pseudo-

first-order (

na = 1) [

49] yields:

Estimates of the best-fit pseudo-order (n), the half-life, and the rate constant (k

a) are made by minimizing the overall root mean square error (RMSE)[

34]. The procedure can be easily performed using the "Solver" add-on in Excel® software. Such calculations allow comparison between different processes without

a-priori assumption of the kinetic order of the reaction, and in such a way- yields a relatively objective evaluation of the efficiency of the process by finding the pseudo-order of the process, and the half-life time based on the pseudo-order [

50,

51].

4.2.3. Photodegradation Experiments on Shadan WWTP Tertiary Effluents

To evaluate the effectiveness of ACE and IHX degradation in real effluents, water from Shafdan WWTP [

52] after tertiary treatment were brought to the laboratory. Preliminary LC-MS measurements indicated that the effluents didn't contain ACE, but a 14 μg L

-1 IHX concentration was measured. It should be mentioned that additional priority pollutants were also found (for example- 22 μg L

-1 carbamazepine). Three different experiments were performed, all of them with injection of 75 μM (2.55 mg L

-1) of H

2O

2 (a) Shafdan original effluents (b) Shafdan original effluents spiked with 1000 μg L

-1 of ACE or IHX in separate experiments, and (c) Shafdan original effluents spiked with 1000 μg L

-1 of both ACE and IHX.

4.3.1. HPLC Measurements

Part of the measurements were performed by injecting 5 μL of the extracted solutions into a UHPLC connected to a photodiode array detector (Dionex Ultimate 3000), with a reverse-phase column (ZORBAX Eclipse plus C18, 3.0*100 mm, 1.8 μm). The mobile phase consisted of (A) DDW with 0.1% formic acid and (B) acetonitrile containing 0.1% formic acid. The gradient started with 2% B and kept isocratic for 2 min, then increased to 75% B in 16 minutes, then increased to 95% in 1 minute and kept isocratic at 95% B for 4 minutes. Phase B returned to 5% in 2 minutes and the column allowed to equilibrate at 5% B for 3 minutes before the next injection. The flow rate was 0.4 mL/min. Column temperature set to 35 °c.

4.3.2. MS/MS Analysis

Measurements for analysis of degradation byproducts were made with Mass spectrometry (MS) analysis performed with Heated Electrospray ionization (HESI-II) source connected to a Q Exactive™ Plus Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap™ Mass Spectrometer Thermo Scientific ™. ESI capillary voltage was set to 3900 V in positive mode and 3500 V in negative mode, capillary temperature to 350 °c, gas temperature to 350 °c. Sheath gas flow set to 35 ml/min, aux gas flow to 10 ml/min and sweep gas flow to 1 ml/min. The mass spectra in Positive-ion mode (m/z 67–900) and in Negative mode (m/z 50–300) and acquired with high resolution (FWHM=70,000 at m/z=200. For MS2 analysis collision energy set to 20, 30 and 50 EV.

Data preprocessing for MS targeted analysis were conducted using Thermo Scientifc™ Xcalibur™ instrument control software. Extracted ion chromatograms for figure production were generated in Xcalibur 4.0.27.19 software using a mass window of (+/−) 5 ppm. Exact m/z values used for figure creation and peak integration corresponded to theoretical [M + H]+ ion m/z values and were as follows: Iohexol 821.8876 m/z, [M - H] Acesulfame 161.9866 m/z. Peak integration was performed using QNTM software after determine LOD, LOQ and linearity for each analyte

Data preprocessing for MSMS untargeted analysis and peak determination and peak area integration for IHX and ACE decomposition products, was performed with Compound Discoverer 3.1 (Thermo Xcalibur, Version 3.3.0.305) using metabolism workflow. Auto-integration was manually inspected and corrected if necessary. For some of the compounds, identification was performed based on MzCloud database using MS2 data and ChemSpider database using MS2 data and HRMS.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Concentrations of ACE or IHX without turning on the UVC system or adding any additional reagent.; Video S1: Short video of the device in action; Scheme S1: Copilot (AI) generated detailed breakdown of hydrolysis and deiodination pathways of iohexol.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.R.; methodology, R.S, S.K, L.L and G.R.; software, R.S and S.K.; validation, R.S, S.K, L.L and G.R.; formal analysis, R.S. and G.R; investigation, R.S, S.K, L.L and G.R..; resources, G.R and S.K.; data curation, R.S, L.L and G.R.; writing—original draft preparation, G.R.; writing—review and editing, R.S, S.K, L.L and G.R..; visualization, R.S, L.L and G.R..; supervision, G.R. and S.K.; project administration, G.R.; funding acquisition, G.R.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Israel Innovation Authority Grant #75367, in cooperation with Mekorot (Israeli Water Company). Additional financial support (Dr. Lior Levy scholarship) was received from CSO-MOH (Israel) in the frame of the collaborative international consortium (REWA) financed under the GA Nº 869178 Joint call of the AquaticPollutants ERA-NET Cofund (GA Nº 869178).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Eng. Ilan Katz and Mr. Gonen Eshel for the full technical support, including the detailed descriptions, planning, and construction of the device. We also want to thank Mr. Mordi Tobol, Mr. Chen Barak, Dr. Ilil Levakov, and other students and technicians at the Environmental Physical Chemistry Laboratory at MIGAL Research Institute. Of course, none of those results would be achieved without the logistical support of all the staff at MIGAL Research Institute and at Tel Hai College. Special thanks to Mr. Ori Ben Herzl for encouraging us along the way in such a difficult period in our region.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACE |

Potassium 6-methyl-2,2-dioxo-2H-1,2λ6,3-oxathiazin-4-olate- acesulfame |

| AOP |

Advanced oxidation process |

| C/C0

|

Ration between measured concentration and initial concentration |

| CBZ |

Carbamazepine |

| EPA |

US Environmental Protection Agency |

| H2O2

|

Hydrogen peroxide |

| IHX |

5-[N-(2,3-Dihydroxypropyl)acetamido]-2,4,6-triiodo-N,N′-bis(2,3-dihydroxypropyl)isophthalamide, iohexol |

| min |

Minutes |

| t1/2

|

Half life time |

| t95%

|

Evaluated time until 95% of the pollutant is removed |

| TiO2

|

Catalytic grade titanium dioxide |

| UV |

Ultraviolet light |

| UVC |

Ultraviolet light in the range 190-280 nm |

| WWTP |

Wastewater treatment plant |

References

- EPA Toxic and Priority Pollutants Under the Clean Water Act | US EPA. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/eg/toxic-and-priority-pollutants-under-clean-water-act (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Sauvé, S.; Desrosiers, M. A Review of What Is an Emerging Contaminant. Chem. Cent. J. 2014, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramírez-Malule, H.; Quiñones-Murillo, D.H.; Manotas-Duque, D. Emerging Contaminants as Global Environmental Hazards. A Bibliometric Analysis. Emerg. Contam. 2020, 6, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naidu, R.; Arias Espana, V.A.; Liu, Y.; Jit, J. Emerging Contaminants in the Environment: Risk-Based Analysis for Better Management. Chemosphere 2016, 154, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathi, S.; El Din Mahmoud, A. Trends in Effective Removal of Emerging Contaminants from Wastewater: A Comprehensive Review. Desalin. Water Treat. 2024, 317, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin-Crini, N.; Lichtfouse, E.; Fourmentin, M.; Ribeiro, A.R.L.; Noutsopoulos, C.; Mapelli, F.; Fenyvesi, É.; Vieira, M.G.A.; Picos-Corrales, L.A.; Moreno-Piraján, J.C.; et al. Removal of Emerging Contaminants from Wastewater Using Advanced Treatments. A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2022 202 2022, 20, 1333–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, T.; Momin, S.; Ali, R.; Naeem, A.; Khan, A.; Mahmood, T.; Momin, S.; Ali, R.; Naeem, A.; Khan, A. Technologies for Removal of Emerging Contaminants from Wastewater. Wastewater Treat. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, B.S.; Kumar, P.S.; Show, P.L. A Review on Effective Removal of Emerging Contaminants from Aquatic Systems: Current Trends and Scope for Further Research. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 409, 124413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, A.; Jebur, M.; Kamaz, M.; Wickramasinghe, S.R. Removal of Emerging Contaminants from Wastewater Streams Using Membrane Bioreactors: A Review. Membr. 2022, Vol. 12, Page 60 2021, 12, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, A.; Al-Khatib, I.A.; Rahman, R.O.A.; Imai, T.; Hung, Y.-T.; Almeida-Naranjo, C.E.; Guerrero, V.H.; Alejandra Villamar-Ayala, C. Emerging Contaminants and Their Removal from Aqueous Media Using Conventional/Non-Conventional Adsorbents: A Glance at the Relationship between Materials, Processes, and Technologies. Water 2023, Vol. 15, Page 1626 2023, 15, 1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Ren, Z.; Bergmann, U.; Uwayezu, J.N.; Carabante, I.; Kumpiene, J.; Lejon, T.; Levakov, I.; Rytwo, G.; Leiviskä, T. Removal of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) from Water Using Magnetic Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB)-Modified Pine Bark. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levakov, I.; Shahar, Y.; Rytwo, G. Carbamazepine Removal by Clay-Based Materials Using Adsorption and Photodegradation. Water (Switzerland) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, M.; Kaykioglu, G.; Belgiorno, V.; Lofrano, G. Removal of Emerging Contaminants from Water and Wastewater by Adsorption Process; Springer: Netherlands, 2012; ISBN 9789400739161. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S. Recent Advances in the Removal of Emerging Contaminants from Water by Novel Molecularly Imprinted Materials in Advanced Oxidation Processes—A Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 883, 163702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demetriou Dionysiou, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Emerging Contaminant Removal. Adv. Oxid. Process. Emerg. Contam. Remov. 2023, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypart-Pawul, A.; Neczaj, E.; Grobelak, A. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Removal of Organic Micropollutants from Wastewater. Desalin. Water Treat. 2023, 305, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghime, D.; Ghosh, P.; Ghime, D.; Ghosh, P. Advanced Oxidation Processes: A Powerful Treatment Option for the Removal of Recalcitrant Organic Compounds. Adv. Oxid. Process. - Appl. Trends, Prospect. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comninellis, C.; Kapalka, A.; Malato, S.; Parsons, S.A.; Poulios, I.; Mantzavinos, D. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water Treatment: Advances and Trends for R&D. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2008, 83, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, U.; Spahr, S.; Lutze, H.; Wieland, A.; Rüting, S.; Gernjak, W.; Wenk, J. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water and Wastewater Treatment – Guidance for Systematic Future Research. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Shea, K.E.; Dionysiou, D.D. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water Treatment. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2012, 3, 2112–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojan UV Resources Environmental Contaminant Treatment Product Brochure. Available online: https://www.trojanuv.com/resources//Products/TrojanUVPhox/TrojanUV_ECT_Products_Brochure.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Hodges, B.C.; Cates, E.L.; Kim, J.H. Challenges and Prospects of Advanced Oxidation Water Treatment Processes Using Catalytic Nanomaterials. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cates, E.L. Photocatalytic Water Treatment: So Where Are We Going with This? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 757–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benotti, M.J.; Stanford, B.D.; Wert, E.C.; Snyder, S.A. Evaluation of a Photocatalytic Reactor Membrane Pilot System for the Removal of Pharmaceuticals and Endocrine Disrupting Compounds from Water. Water Res. 2009, 43, 1513–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rytwo, G.; Klein, T.; Margalit, S.; Mor, O.; Naftaly, A.; Daskal, G. A Continuous-Flow Device for Photocatalytic Degradation and Full Mineralization of Priority Pollutants in Water. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 57, 16424–16434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rytwo, G.; Daskal, G. A System for Treatment of Polluted Effluents. PCT/IL2015/050944, WO2016042558 A1, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, E.; Watanabe, Y.; Agusa, T.; Hosono, T.; Nakata, H. Acesulfame as a Suitable Sewer Tracer on Groundwater Pollution: A Case Study before and after the 2016 Mw 7.0 Kumamoto Earthquakes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 142409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Ren, Y.; Fu, Y.; Gao, X.; Jiang, C.; Wu, G.; Ren, H.; Geng, J. Fate of Artificial Sweeteners through Wastewater Treatment Plants and Water Treatment Processes. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0189867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannakis, S.; Jovic, M.; Gasilova, N.; Pastor Gelabert, M.; Schindelholz, S.; Furbringer, J.-M.; Girault, H.; Pulgarin, C. Iohexol Degradation in Wastewater and Urine by UV-Based Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs): Process Modeling and by-Products Identification. J. Environ. Manage. 2017, 195, 174–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrkal, Z.; Adomat, Y.; Rozman, D.; Grischek, T. Efficiency of Micropollutant Removal through Artificial Recharge and Riverbank Filtration: Case Studies of Káraný, Czech Republic and Dresden-Hosterwitz, Germany. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chèvre, N. Pharmaceuticals in Surface Waters: Sources, Behavior, Ecological Risk, and Possible Solutions. Case Study of Lake Geneva, Switzerland. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2014, 1, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Nguyen Song Thuy Thuy, G.; Srivastava, V.; Ambat, I.; Sillanpää, M. Photocatalytic Degradation of an Artificial Sweetener (Acesulfame-K) from Synthetic Wastewater under UV-LED Controlled Illumination. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 123, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Gao, S.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B. Performance of Ultraviolet/Persulfate Process in Degrading Artificial Sweetener Acesulfame. Environ. Res. 2020, 188, 109804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rytwo, G.; Zelkind, A.L. Evaluation of Kinetic Pseudo-Order in the Photocatalytic Degradation of Ofloxacin. Catalysts 2022, 12, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogna, D.; Marotta, R.; Andreozzi, R.; Napolitano, A.; D’Ischia, M.; d’Ischia, M. Kinetic and Chemical Assessment of the UV/H2O2 Treatment of Antiepileptic Drug Carbamazepine. Chemosphere 2004, 54, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Lu, G.; Zhu, X.; Pu, C.; Guo, J.; Liang, X. Insight into the Generation of Toxic By-Products during UV/H2O2 Degradation of Carbamazepine: Mechanisms, N-Transformation and Toxicity. Chemosphere 2024, 358, 142175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haroune, L.; Salaun, M.; Ménard, A.; Legault, C.Y.; Bellenger, J.P. Photocatalytic Degradation of Carbamazepine and Three Derivatives Using TiO2 and ZnO: Effect of PH, Ionic Strength, and Natural Organic Matter. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 475, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, M.N.; Jin, B.; Laera, G.; Saint, C.P. Evaluating the Photodegradation of Carbamazepine in a Sequential Batch Photoreactor System: Impacts of Effluent Organic Matter and Inorganic Ions. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 174, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M.; Chowdhury, P.; Ray, A.K. Study of Solar Photocatalytic Degradation of Acesulfame K to Limit the Outpouring of Artificial Sweeteners. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 207, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Geng, J.; Wu, G.; Gao, X.; Fu, Y.; Ren, H. Removal of Artificial Sweeteners and Their Effects on Microbial Communities in Sequencing Batch Reactors. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zilberman, A.; Gozlan, I.; Avisar, D. Pharmaceutical Transformation Products Formed by Ozonation—Does Degradation Occur? Molecules 2023, 28, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Han, C.; Xu, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhong, Q.; Shi, K.; Xu, Z.; Yang, S.; et al. Improved Degradation of Iohexol Using Electro-Enhanced Activation of Persulfate by a CuxO-Loaded Carbon Felt with Carbon Nanotubes as an Interlayer. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 312, 123336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.Y.; Hou, Y.Z.; Lin, Y.L.; Deng, Y.G.; Hua, S.J.; Du, Y.F.; Chen, C.W.; Wu, C.H. Kinetics and Model Development of Iohexol Degradation during UV/H2O2 and UV/S2O82− Oxidation. Chemosphere 2019, 229, 602–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.Y.; Zeng, C.; Lin, Y.L.; Zhang, T.Y.; Fu, Q.; Zhao, H.X.; Luo, Z.N.; Zheng, Z.X.; Cao, T.C.; Hu, C.Y.; et al. Wavelength Dependency and Photosensitizer Effects in UV-LED Photodegradation of Iohexol. Water Res. 2024, 255, 121477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MRC PP-X-575PP-X-575, Basic Speed –Variable Peristaltic Pump. Available online: https://www.mrclab.co.il/Media/Doc/PP-X-575-V2_SPEC.pdf.

- NUF Technology Overview. Available online: https://www.nufiltration.com/technology.

- White, D.P. Chapter 14-Chemical Kinetics. Available online: my.ilstu.edu/~ccmclau/che141/materials/outlines/chapter14.ppt.

- IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology: Gold Book. IUPAC Compend. Chem. Terminol. 2014, 1670. [CrossRef]

- Shahar, Y.; Rytwo, G. Elementary Steps in Steady State Kinetic Model Approximation for the Homo-Heterogeneous Photocatalysis of Carbamazepine. 2023, 5, 866–880. Clean Technol. 2023, 5, 866–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.D.; Nguyen, D.Q.; Do, P.T.; Tran, U.N.P. Kinetics of Photocatalytic Degradation of Organic Compounds: A Mini-Review and New Approach. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 16915–16925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddy, N.O.; Ukpe, R.A.; Ameh, P.; Ogbodo, R.; Garg, R.; Garg, R. Theoretical and Experimental Studies on Photocatalytic Removal of Methylene Blue (MetB) from Aqueous Solution Using Oyster Shell Synthesized CaO Nanoparticles (CaONP-O). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 81417–81432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mekorot Shafdan Wastewater Treatment Plant. Available online: https://www.mekorot-int.com/blog/project/shepdan/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).