4.1. Experiment 1

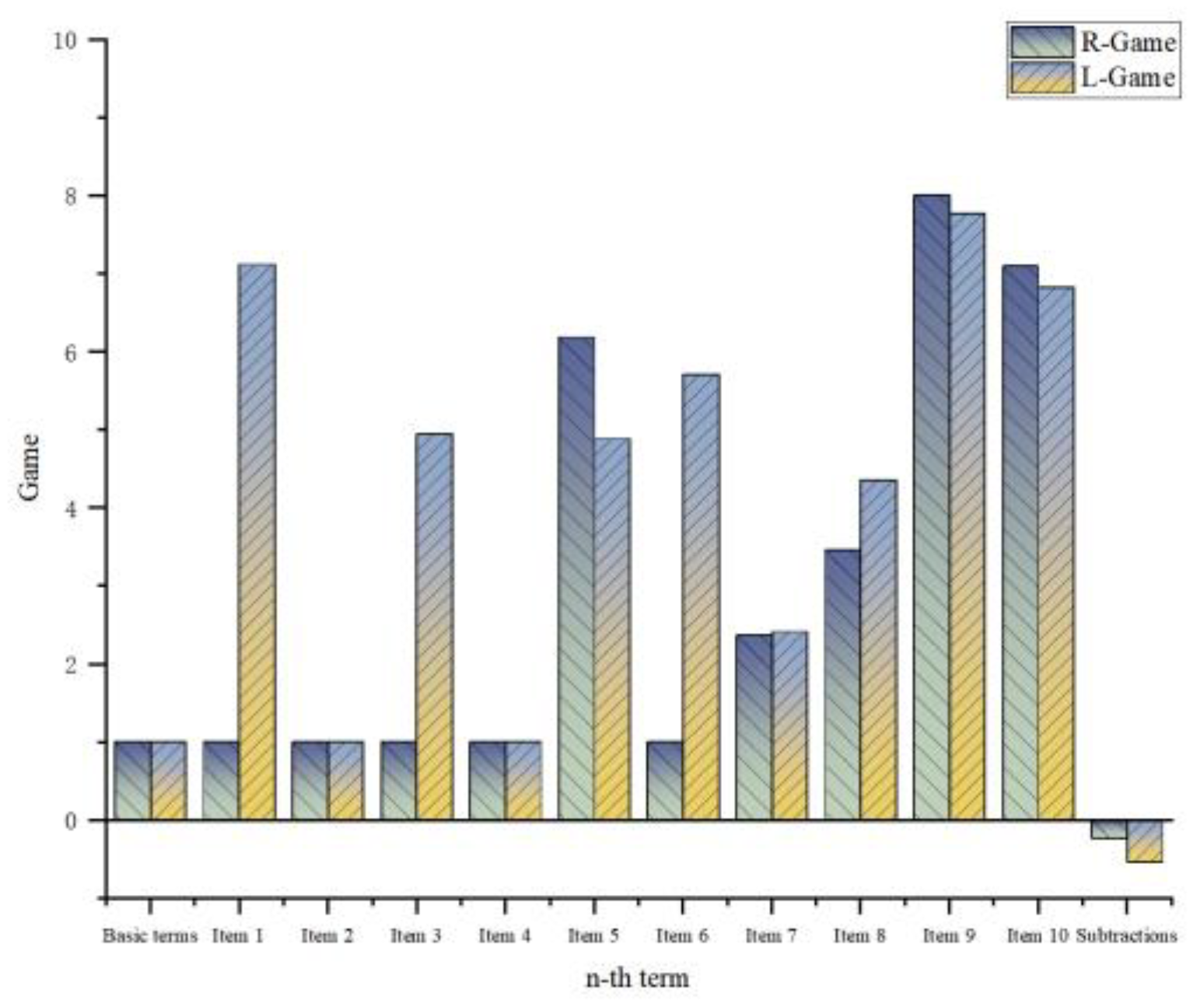

Experiment 1 uses questionnaire II, which is divided into three main categories: basic items, bonus items, and deduction items, with a total of 20 sub-items. This experiment is based on the data in

Table 2 and uses the scoring method to calculate the individual factor scores of all testers, which can be seen in

Table 3 and

Table 4. All individual factors that may affect the validity of hypothesis b are reflected in questionnaire II. For example, finger flexibility may affect the speed and efficiency of button operation, and finger flexibility is not only determined by innate conditions but may also be influenced by acquired training (computer typing speed, proficiency in buttoned instruments, etc.), which are reflected in

Table 3 and

Table 4.

Scores that are too high [80,100) or too low [1,20) may cause severe data dispersion. Through

Table 3 and

Table 4, it can be found that the total scores of all participants are basically between 30-66, and the scores are relatively concentrated. This indicates that all 76 participants can serve as testers. The scores of each sub-item can be compared in the form of bar charts.

According to

Figure 4, the score proportions of various items for participants in the L and R groups are similar (difference: left-handers tend to have a sports advantage, while right-handers tend to have a typing advantage), and the score differences are small. The item with the largest score difference is “personality traits,” with a difference of 2.249 points. It is worth noting that statistics show that left-handed females tend to have a more “negative” personality compared to right-handed females, while this is not evident among males. In addition, left-handed participants are more proficient in using musical instruments, which is consistent with the research of John P. Aggleton and Robert W. Kentridge[

6]. Apart from this, the absolute value of the deduction items for the L group is higher than that for the R group. This is because two left-handed participants had injuries to their left arm, and one had a history of surgery. However, the differences in other items are all within 2 points, indicating that the individual factors of left-handed and right-handed participants are basically similar.

The total score of left-handed participants is slightly lower than that of right-handed participants. Theoretically, the score is positively correlated with the operating ability, which is a characterization phenomenon of the influence of individual factors on operating ability. Therefore, it is preliminarily inferred that the operating ability of right-handed participants is better than that of left-handed participants.

4.3. Experiment 3

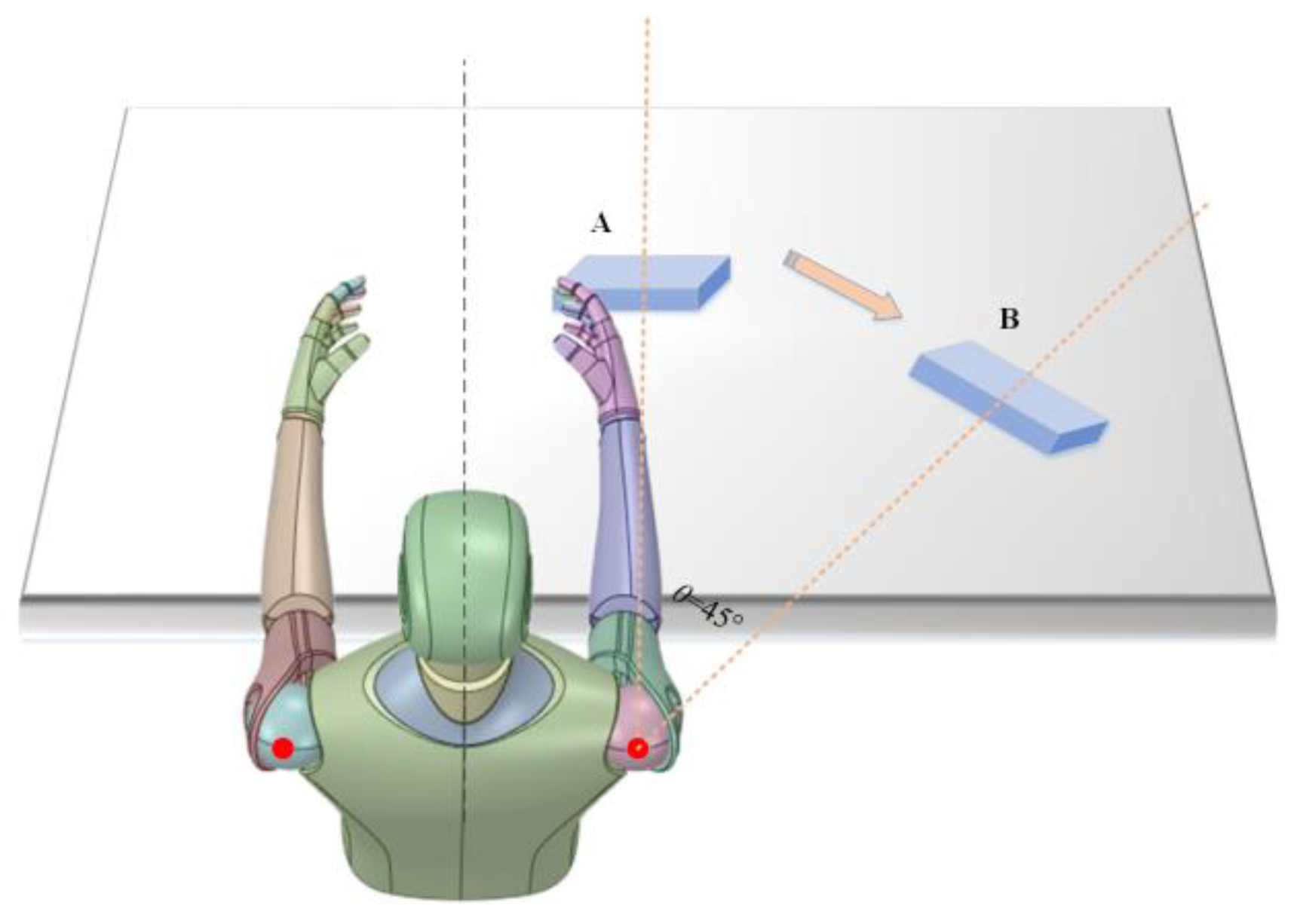

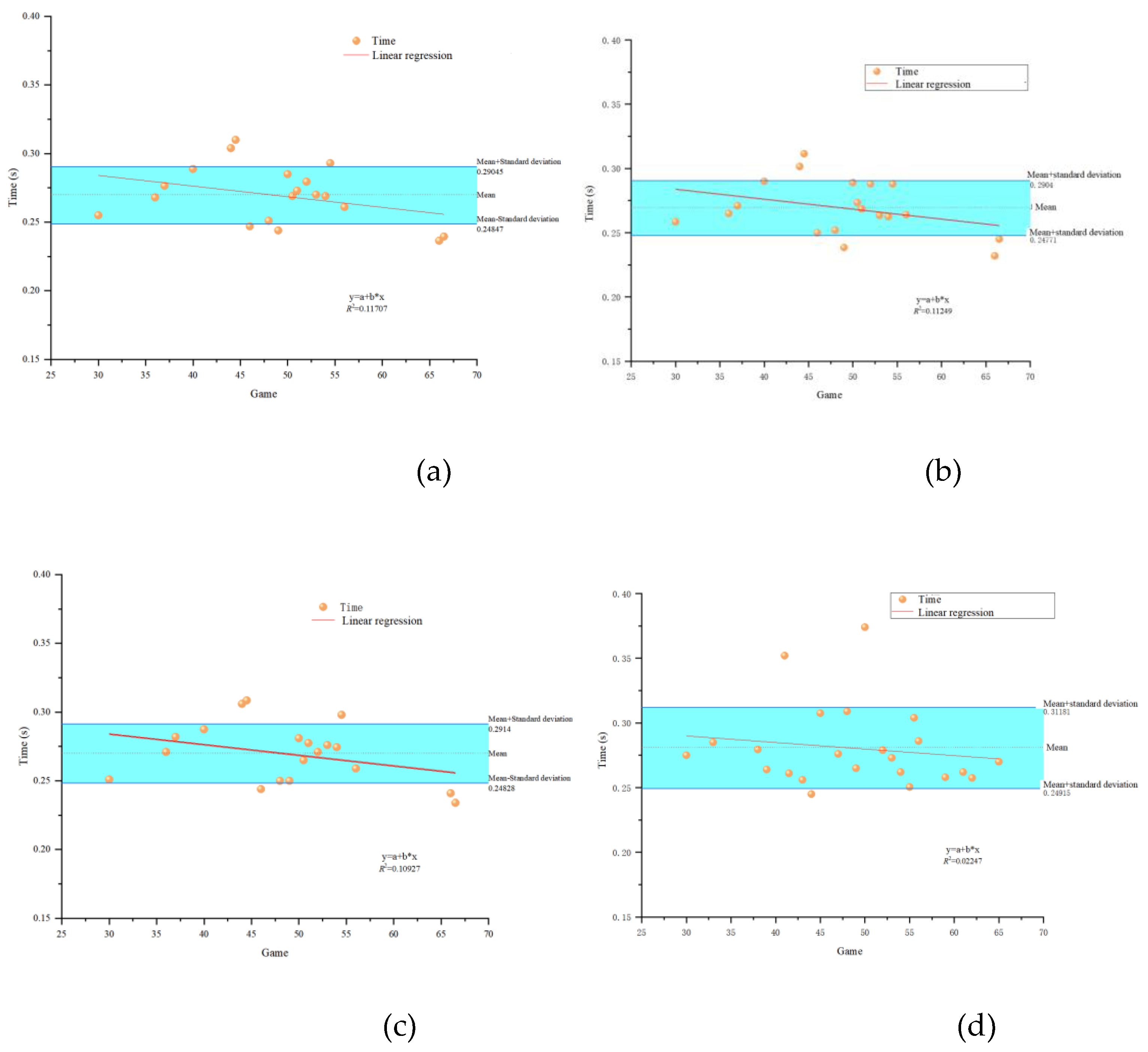

The data shown in

Table 9,

Table 10,

Table 11 and

Table 12 are obtained from Experiment 3. They represent the characterization phenomena of movement time and error rate caused by changes in direction parameters (palm travel angle α and arm extension direction

β) for the L group and R group in Positions A and B. According to the biomechanics classification of arm movement types [

18], we divide arm extension into three directions in this experiment: β

1 (arm forward extension, corresponding to L1 and R1 positions), β

2 (arm inward flexion, left-handers correspond to R2, R3, R4 positions; right-handers correspond to L2, L3, L4 positions), and β

3 (arm outward extension, left-handers correspond to L2, L3, L4 positions; right-handers correspond to R2, R3, R4 positions). Ln and Rn are separately represented as

α. Experiment 3 did not record reaction time because it is not affected by direction parameters, which was confirmed in “

4.2.1 RT”.

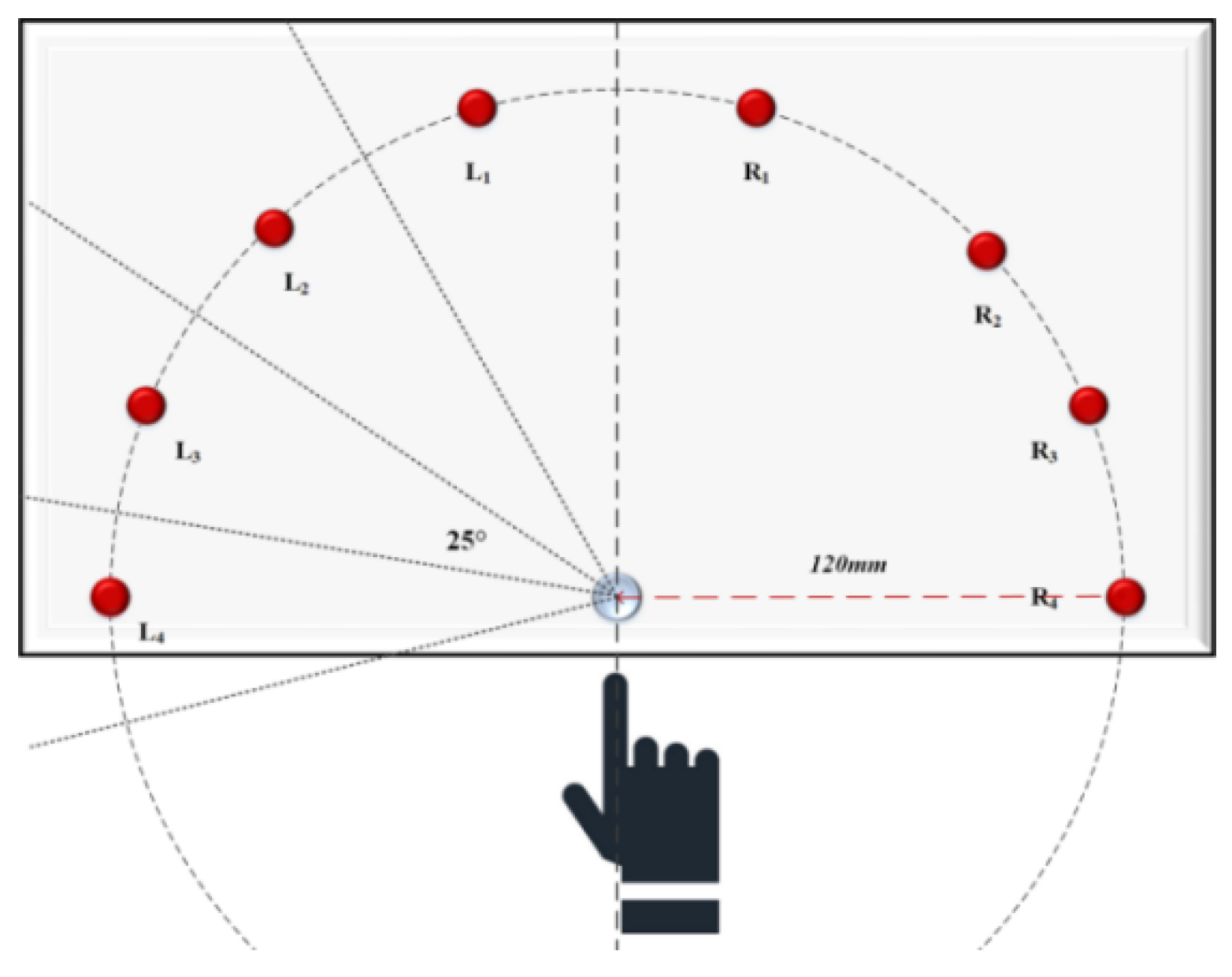

4.3.1. Group R Data Analysis

Concerning the results on the influence of direction parameters on right-handers, please refer to

Table 9 and

Table 10. Based on the data from the R group, the eight positions correspond to different response phenomena, in which both the average movement time (

ET) and the operation error rate are significantly affected by changes in direction parameters.

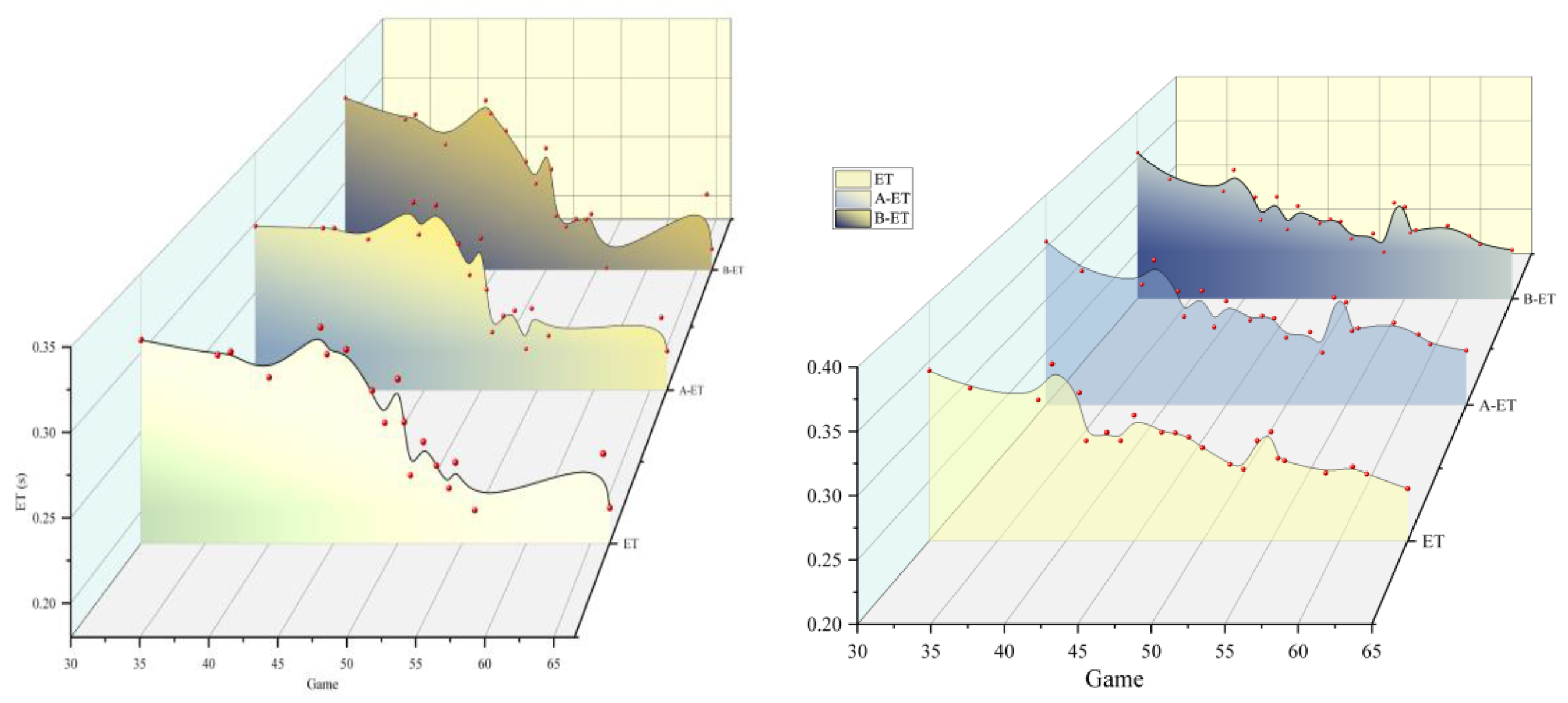

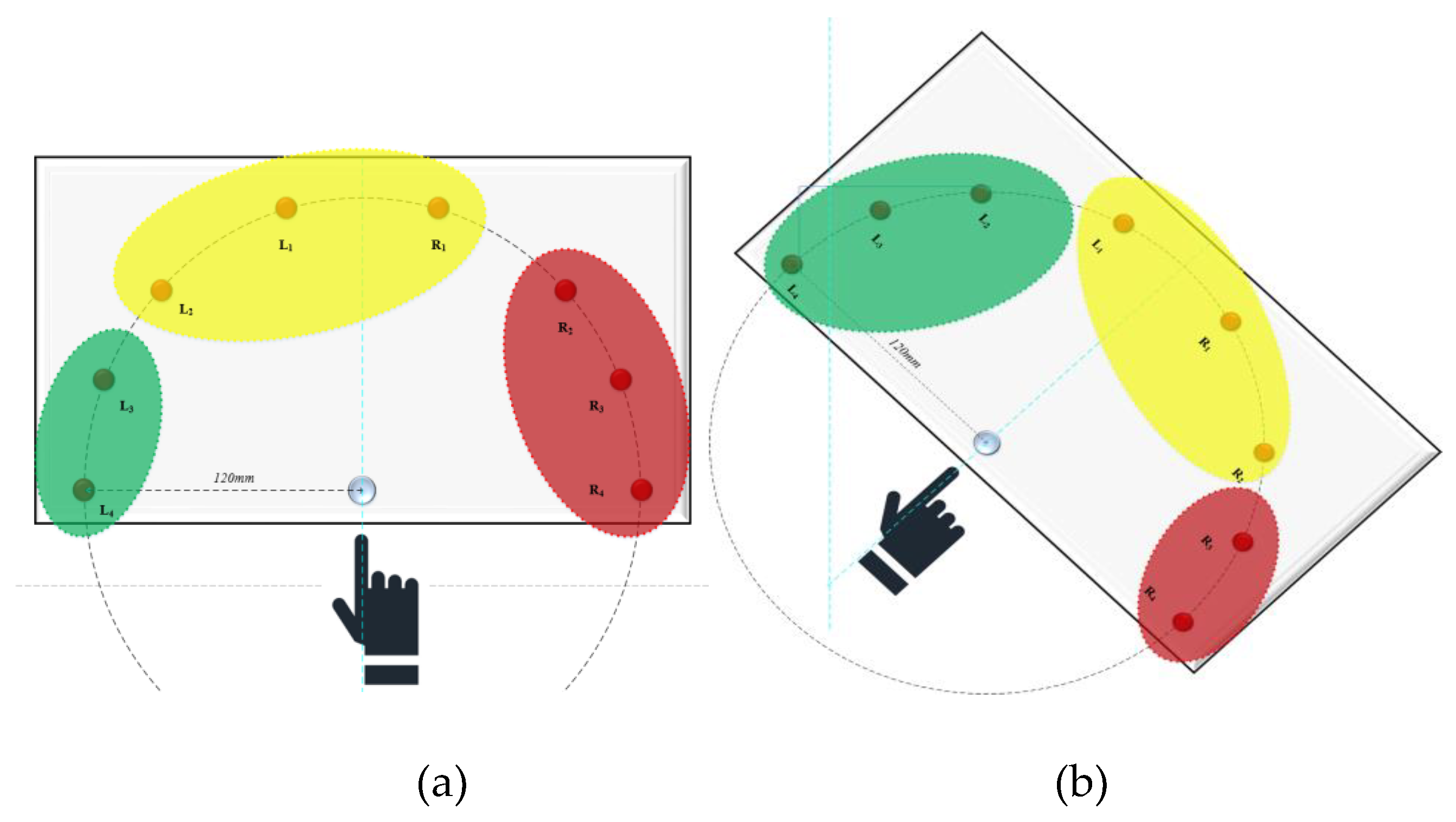

- (1)

A position

Regarding the performance of right-handers at Position A, we can observe different response phenomena for different key stimuli, which may result from the combined effects of α and β. Following the performance patterns of movement time (

ET) in

Table 9, we reorganize the data, dividing α into three regions, as shown in

Figure 9 (a), represented by Red (25, 100), Yellow (-50, 25), and Green (-100, -50) respectively. The study found that the red region has the optimal average movement time, but a high error rate of 13.34%, with

β=(β3) and

α=(R2, R3, R4); the green region has a relatively faster (medium) average movement time and an error rate of 5% (medium), with

β=(β2) arm flexion and

α=(L3, L4); the yellow region has the slowest average movement time, but an error rate of 0 in 30 stimuli, with

β=(β1, β2) and

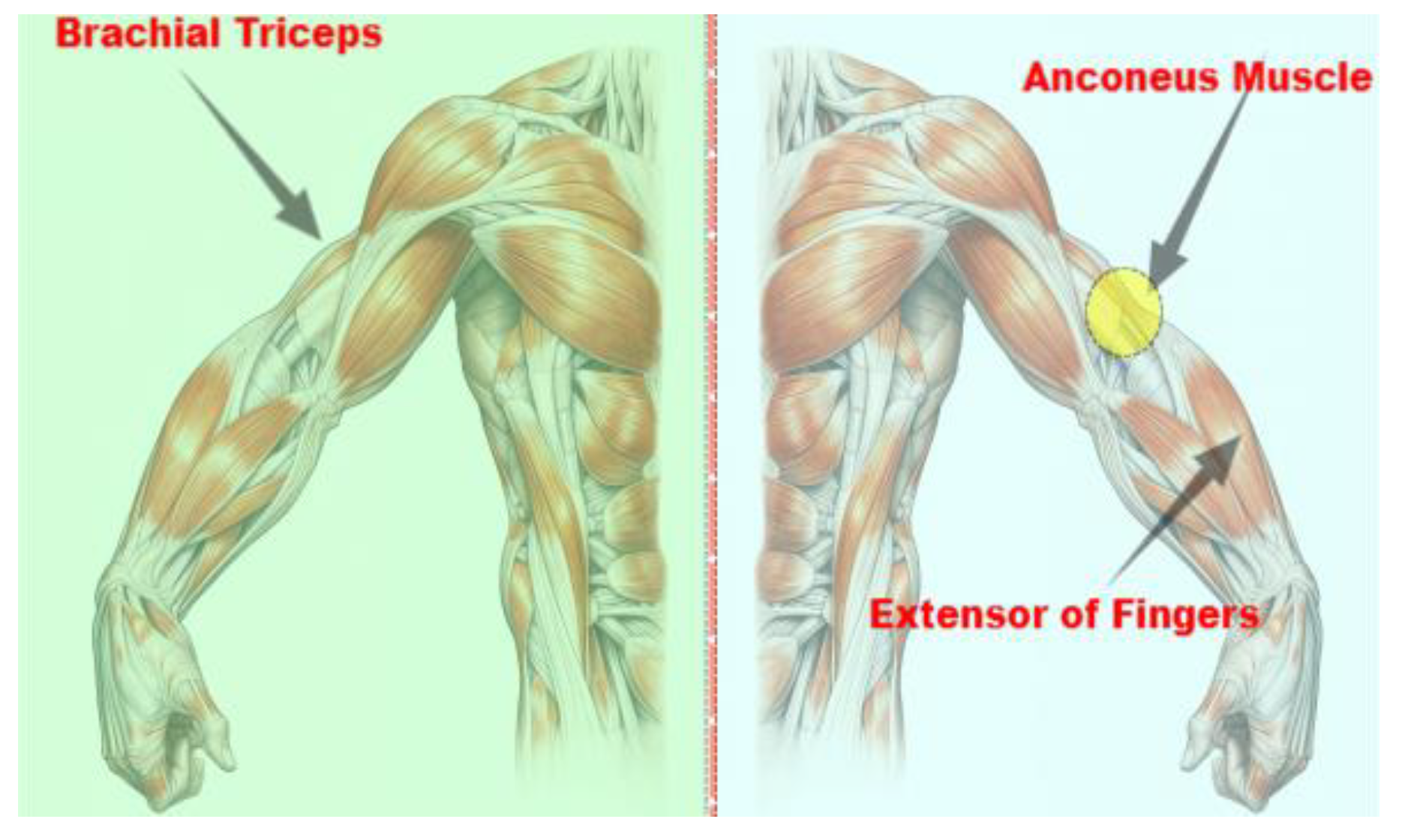

α=(R1, L1, L2). For the red region, we find that R3 and R4 have the fastest speeds, which is because when test subjects receive stimuli from R3 and R4, the arm extension speed is affected by the triceps brachii, brachialis, and extensor digitorum muscles (collectively referred to as the “muscle group”), as illustrated in

Figure 9. Moreover, it is understood that almost every test subject reported feeling relaxed when the lateral keys were illuminated, while feeling fatigued when L1 and L2 were illuminated. In addition, the higher error rate in the red region is due to test subjects stating that when R3 and R4 were illuminated, their fingers could quickly capture the keys, but during the finger movement process, the lateral position of the palm obscured the stimulating light, leading to errors in finger capturing. However, this was not evident for other

α values. The above findings represent the performance of right-handers at Position A when receiving urgent stimuli.

- (2)

B position

Similar to Position A, the performance of right-handers at Position B is also influenced by the combined effects of

α and

β. However, at Position B, the red region shrinks, and R2 is no longer included. Both the Yellow and Green regions extend 25° to the right (toward the lateral side of the arm). It is worth noting that the yellow region at Position B performs better in terms of reaction time and error rate than the green region. In contrast, the green region’s performance at Position B is not as good as at Position A. This is because Position B is on the 45° line to the right of the body’s central axis, and at this position, the green region takes on some of the yellow region’s functions under unfavorable conditions. The specific patterns can be observed in

Table 10. Similarly to Position A, test subjects still reported that keys in the lateral area were easier to capture. The above findings represent the performance of right-handers at Position B.

4.3.2. Group L Data Analysis

Regarding the results of the influence of direction parameters on left-handers, please refer to

Table 11 and

Table 12. These results show a certain mirror pattern compared to the characterization phenomena of right-handers.

Here is a set of illustrations.

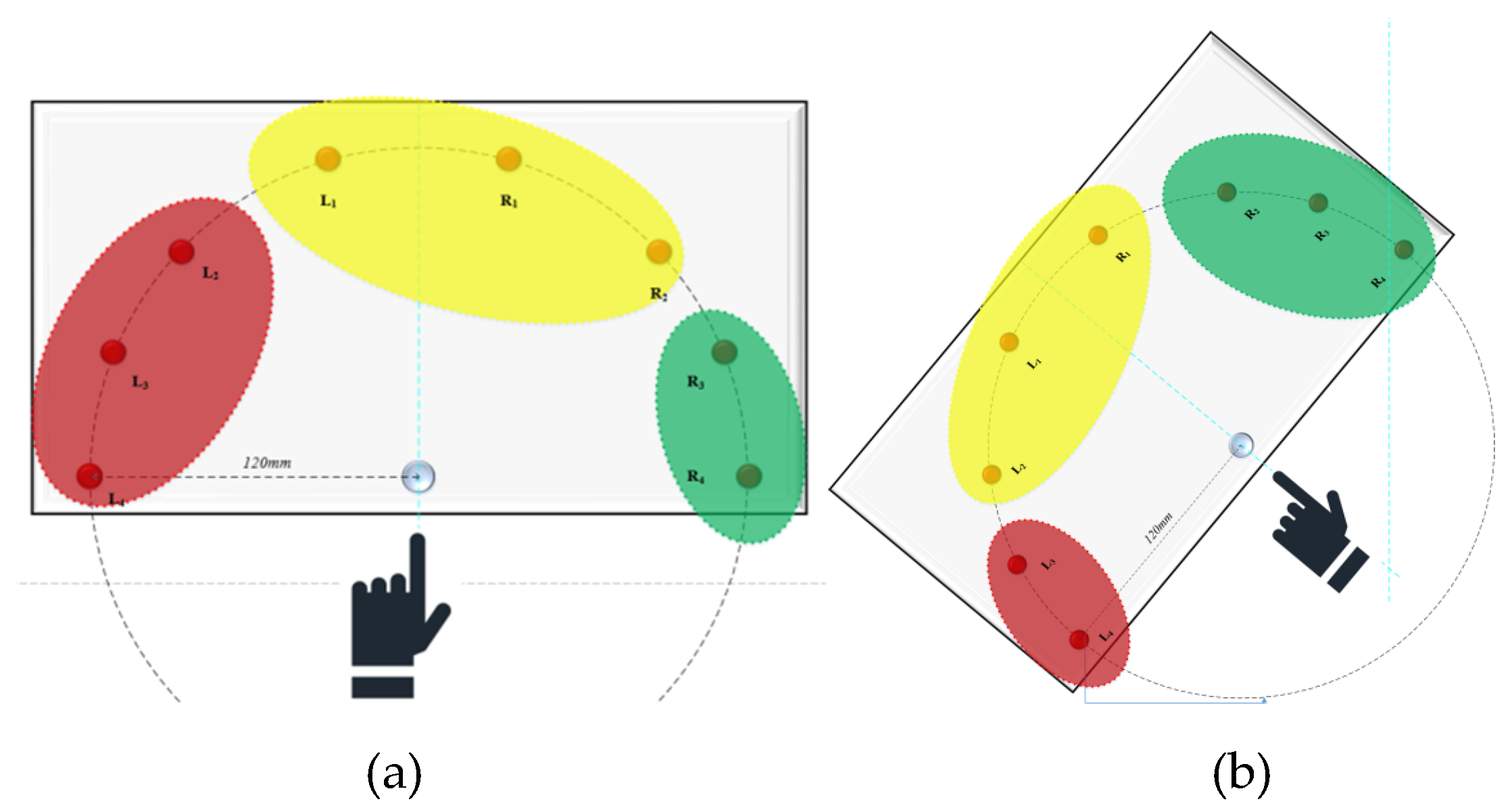

Similar to the A and B positions of right-handers, the performance of left-handers at positions A and B is also influenced by the combined effects of

α and

β. The red (-100, -25), yellow (-25, 50), and green (50, 100) regions for left-handers are symmetric with respect to the midline axis compared to the three regions for right-handers, as shown in

Figure 11. It should be noted that while

β is symmetric, the specific values of

α are not symmetric. For example, the average reaction time for left-handers in the red region at Position A is 225.45ms, with an error rate of 10%, which is significantly better than right-handers. However, for left-handers at Position A, the green region’s performance in terms of reaction time and error rate is significantly better than the yellow region, which is the opposite of right-handers. Similarly, left-handers at Position B also exhibit differences between the yellow and green regions. It is understood that left-handed test subjects agreed with the right-handed test subjects’ description of the yellow region, but they believed that for the red region, the yellow region might be more prone to errors. The data in

Table 11 can verify this point.

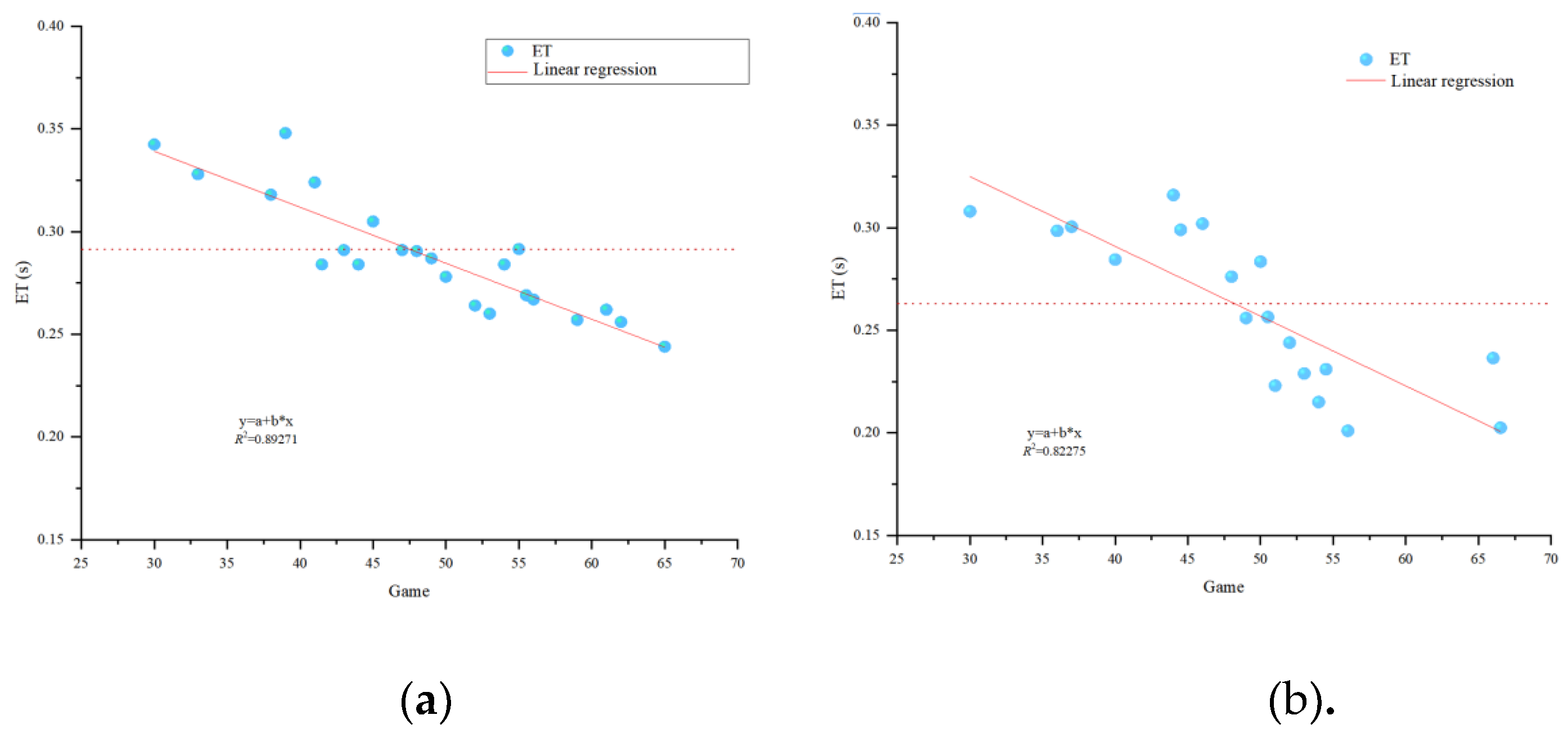

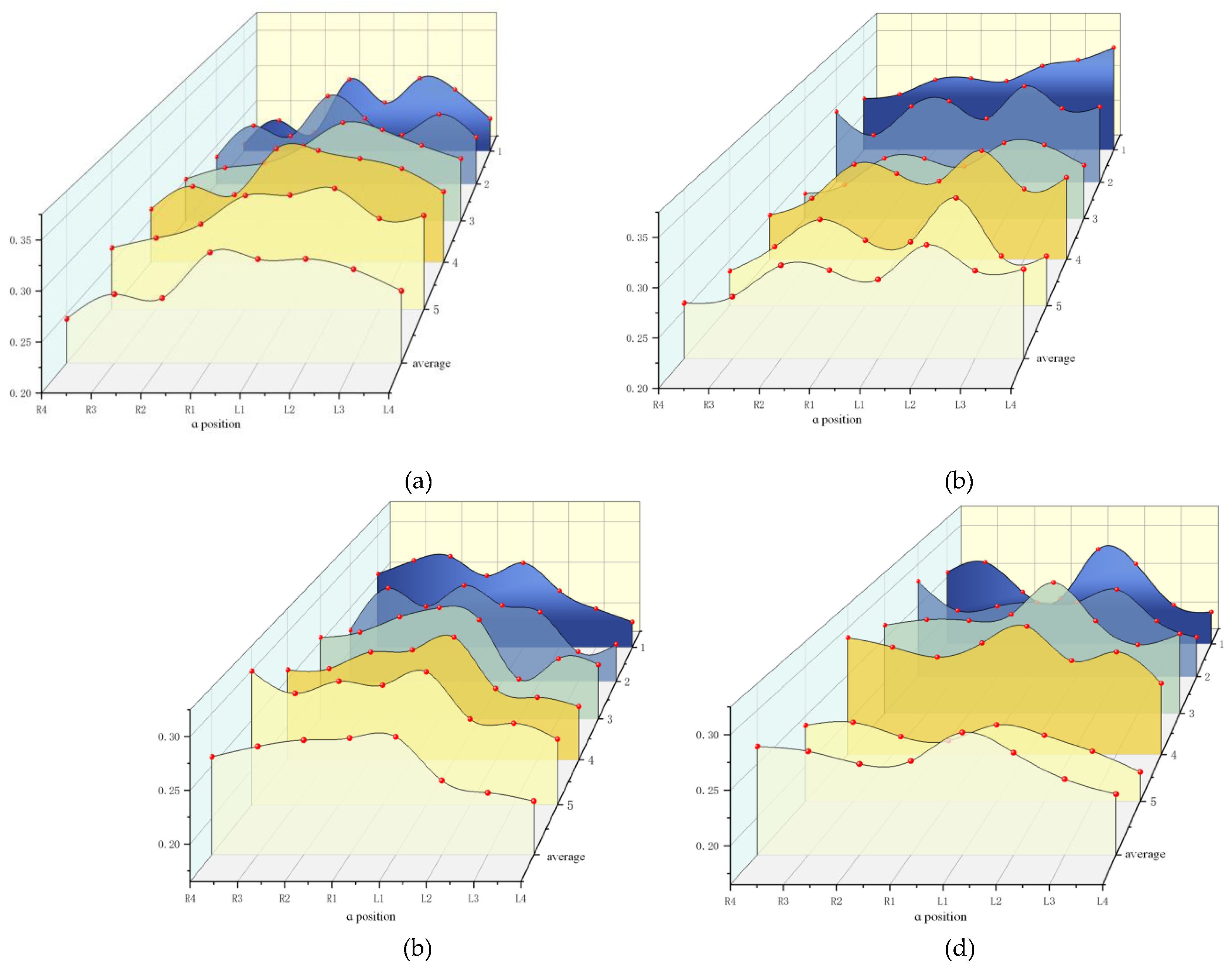

Figure 12 shows the individual data of the five test subjects in Groups L and R at different positions. Taking

Figure 12(a) as an example, the trends in individual data among the test subjects are generally consistent. The optimal

α for left-handers (

α=

Li) and right-handers (

α=

Ri) are symmetric with respect to the midline axis, both at the outermost position of

β3. However, the least optimal positions (slowest reaction times) are not symmetric, which can be proven by comparing Figures 12(b) and 12(d). In addition, the statistics on error rates in Tables 9, 10, 11, and 12 are also used to demonstrate the asymmetry. In summary, when the left and right hands are used as the dominant hands, even with the same movement distance and symmetric movement direction (

Li and

Ri), the characterization phenomena of the dominant hand change at this moment (incomplete symmetry). At the same time, within the same region, the overall performance (speed and error rate) of left-handers is better than that of right-handers, and the value of

α does not affect this pattern.

Overall, in emergency operation scenarios where personal safety is considered, left-handed test subjects have better motor skills, reaction abilities, and correct capture abilities than right-handed test subjects. Individual factors do not change this advantage, and the advantage is even amplified as individual factor scores increase. In addition, when considering the palm travel angle α and arm extension direction β, the characterization phenomena of the dominant hand show incomplete symmetry. However, regardless of how α (Li and Ri) and β change, the overall performance (speed and error rate) of left-handers is still better than that of right-handers. In conclusion, due to the existence of hand dominance, there are differences in operating abilities between left-handers and right-handers, which indirectly affect the safety of HCAS. Hypothesis b is considered to be established.

4.4. Applying Extensions

Considering the overall safety of emergency operation positions, they widely exist worldwide, such as high-speed train driving positions, pilot positions, and firefighting equipment operation positions. When hypothesis b is considered established, the conclusions obtained from the experiments (in emergency operation scenarios where personal safety is considered, left-handed test subjects have better motor skills, reaction abilities, and correct capture abilities than right-handed test subjects) will have an impact on the actual operation positions. The differences in dominant hands may cause a chain reaction and affect safety. Therefore, we have to prove the significance and impact of the conclusions in practice.

Taking the CRH5G high-speed train driving position as the main analysis object and based on the HE principle, we use the conclusions obtained from experiments 1, 2 and 3 to determine the emergency brake valve positions suitable for left-handed or right-handed drivers. Then, according to the vector coordinates (direction and distance) and button size of the position, we use Fitts’ law [

34] to determine the time difference required for left-handed and right-handed drivers to capture the brake valve in scenarios requiring emergency braking.

It is worth noting that the CRH5A train uses a button-type brake valve, while some vehicles use a brake lever. They are consistent in principle. For the convenience of the study, we choose the brake valve-type train driving cab.

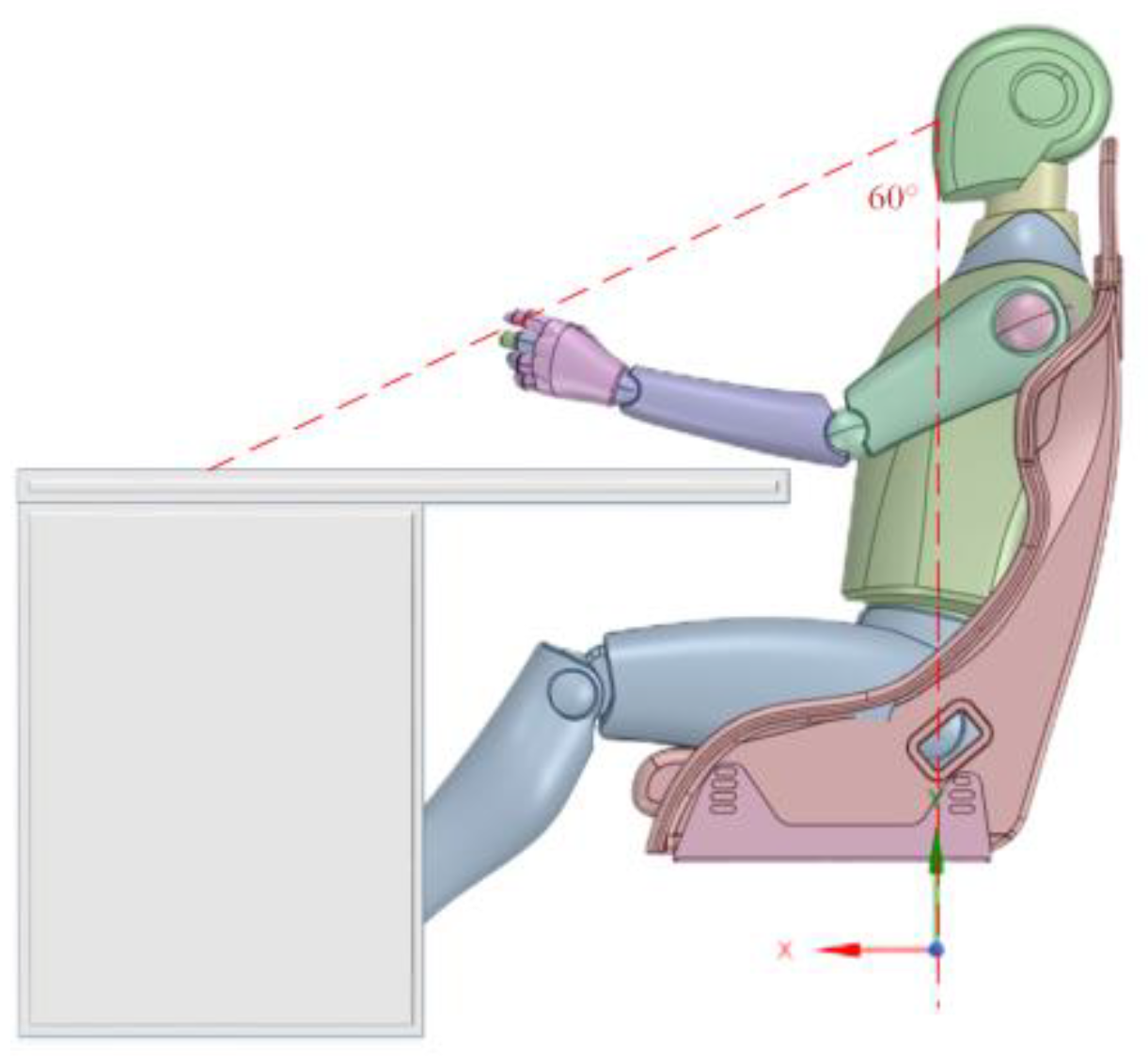

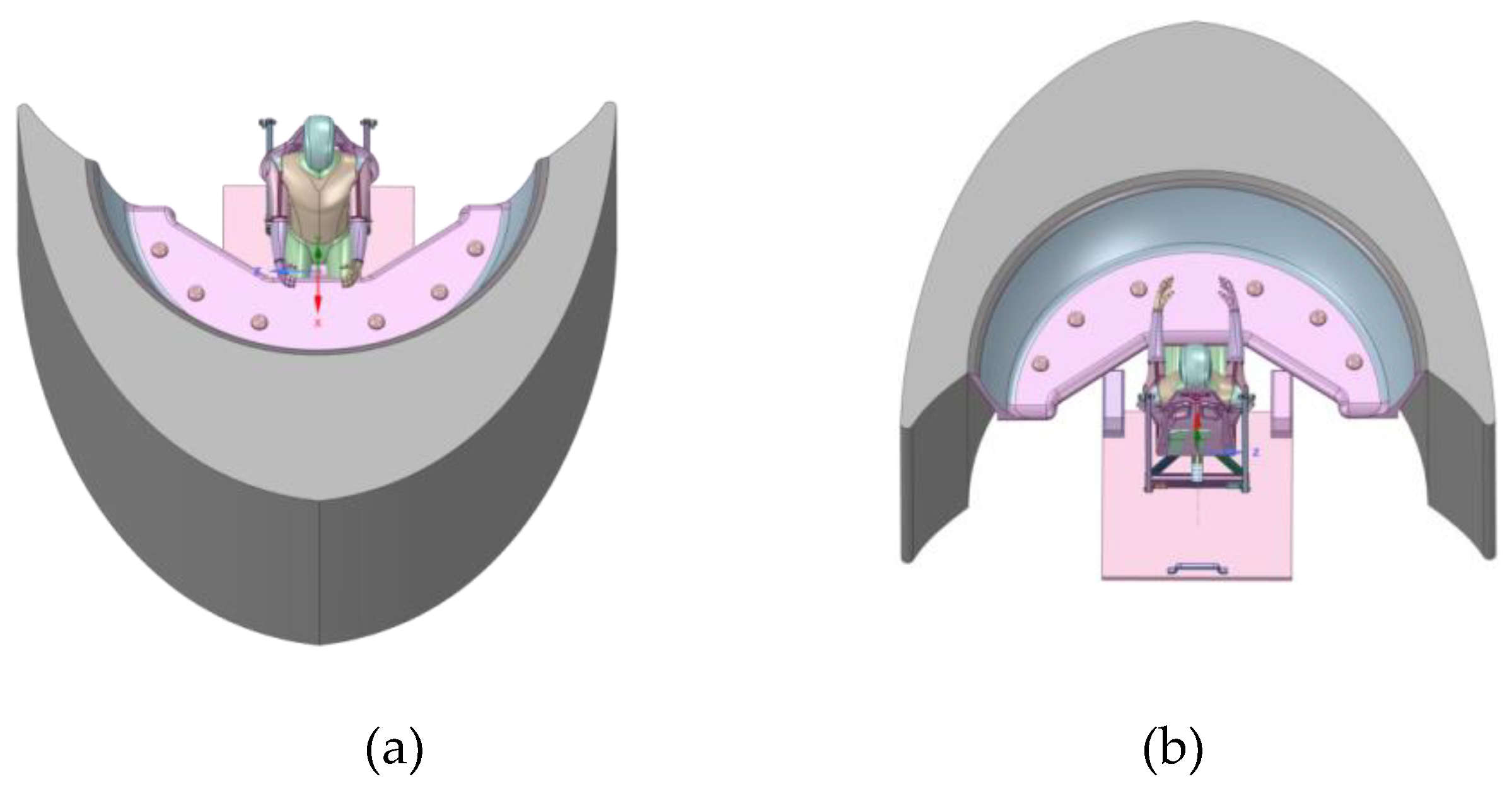

Figure 13 shows the CRH-type driving cab operating platform and a three-dimensional model of the driver’s basic operating posture, with the button representing the pre-set position of the brake valve.

Based on previous studies [

35,

36], we focus on the differences in dominant hands to determine the valve position coordinates suitable for left and right dominant hands. Before this, we need to exclude equipment factors unrelated to this study: valve body color, shape, appearance, etc., as well as personnel factors unrelated to this study: driver’s sitting posture, driver’s psychological quality, etc. Environmental factors and management factors are not considered. The determination of valve position coordinates will be divided into three steps:

1. Determine which positions cannot be set with brake valves;

2. Determine the optimal brake valve setting orientation through the conclusion of experiment 3;

3. Combining the results of a and b, we can determine the optimal valve position that is suitable for both left-handed and right-handed drivers, allowing them to perform emergency braking operations effectively and safely.

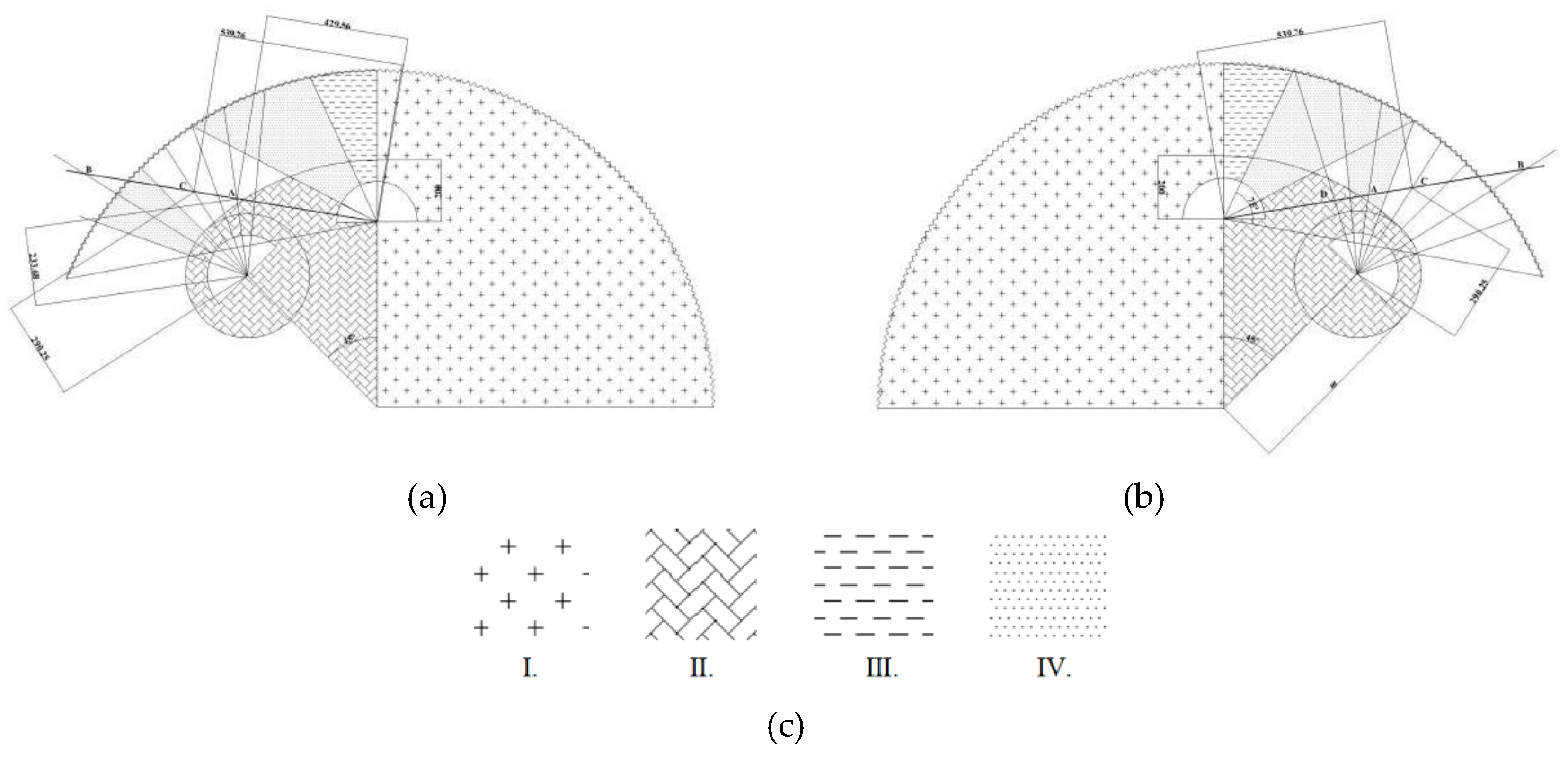

1. Identify admissible areas

The disallowed areas refer to the areas where brake valves cannot be set according to regulations, as well as the areas prone to accidental touches and high error rate areas. It is understood that the layout of the train driving cab needs to be strictly designed according to the specifications. Based on previous research [

32], we have developed a selection model for all disallowed areas, as shown in

Figure 14 (a) and (b).

Area Ⅰ is the train control basic button area, where emergency brake valves cannot be set; Area Ⅱ is the prone-to-accidental-touch area, which includes two accidental touch scenarios: the area swept by the arm during the movement of the palm from position A to position B, and the area within 100mm around the palm; Area Ⅲ is prone to obstructing the view of the display screen; Area Ⅳ is the high-error-rate area (>10%) measured in Experiment 3.

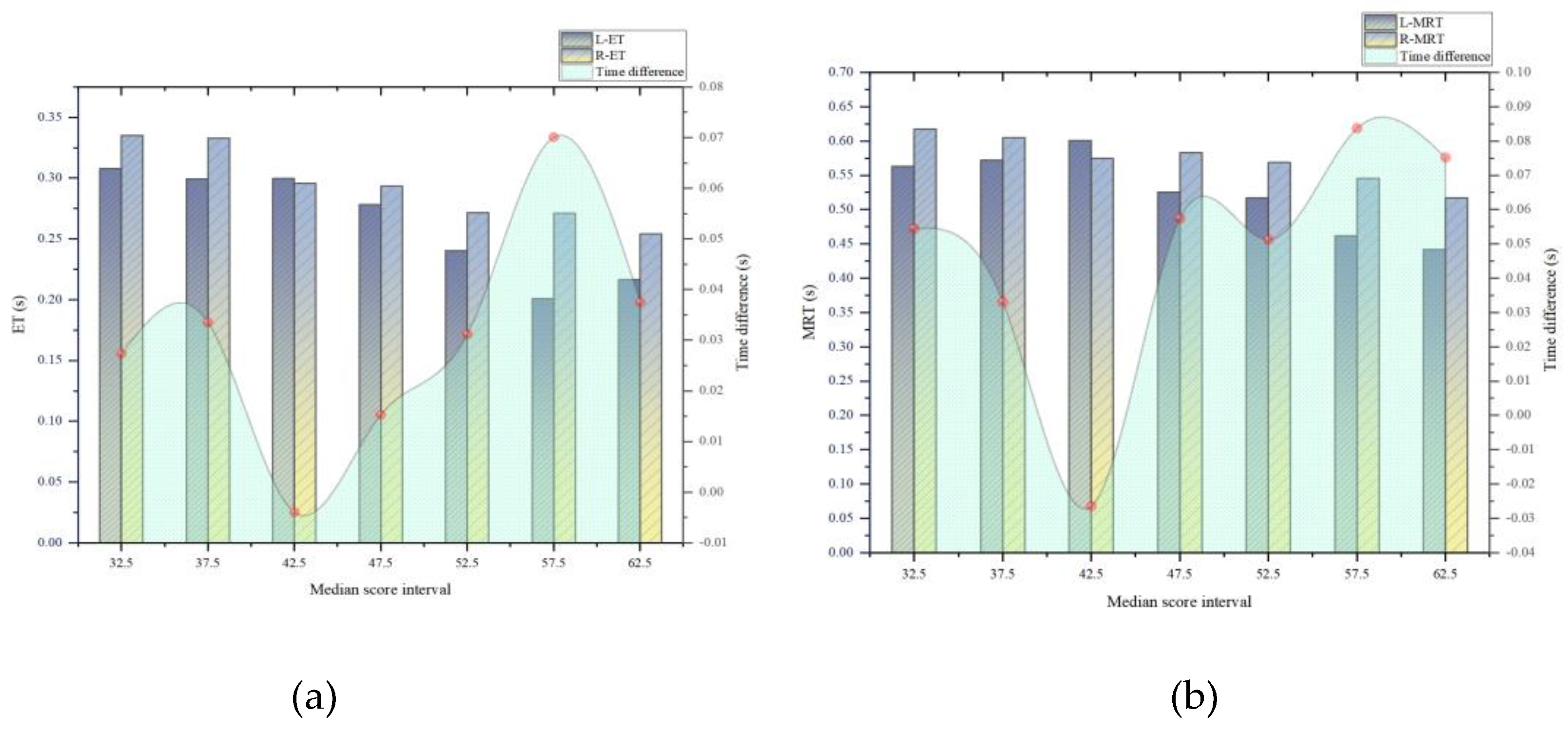

2. Set the orientation to determine

As we know, train drivers are required to place their hands in front of their body (Position A). To alleviate the discomfort caused by maintaining the same posture for an extended period, they will place their hands on the sides of the table (Position B) when it doesn’t affect their operation. Experiment 3 provides two sets of positions A and B, corresponding to the standard hand placement and the natural hand placement for train drivers. In an emergency, the driver’s hands may be in either position A or B. Therefore, we choose the intersection point JD of the bisector of the optimal area α of positions A and B as the optimal position for the valve.

For left-handed drivers, we choose the (-100, -62.5) interval as the optimal area for position A, considering that although the red area has the best MRT, the error rate (Er=10%) is relatively high. Therefore, we select a quarter of the red area’s angle as the optimal area, with the bisector O1A=-81.25° as the optimal line. For position B, the directions O2A, O2B, and O2C are all selectable, and their intersection points with O1A are JDA, JDB, and JDC. However, point JDB is beyond the operable distance (100cm from the shoulder joint). Similarly, when analyzing the optimal orientation for right-handed drivers, only point JDC can be selected.

3. Determine the optimal position of the valve

Fitts’ Law refers to the time it takes to reach a target using a “pointing device” being related to two factors: the distance between the current position of the device and the target (

l), and the size of the target (

w). Fitts’ Law was proposed in 1954 by Dr. Fitts from the United States and is one of the most widely used models in the human-computer interaction (HCI) field. Studies have shown [

37] that Fitts’ Law can be expressed based on the arm’s kinematics, making it very suitable for human behavior data in various situations. The expression of Fitts’ Law in this study is shown in Equation (2):

(2)

l represents the movement amplitude; w represents the target width, which is 5cm; MRT represents the mechanical response time of the arm; a and b are empirical coefficients. The coefficient a is determined by the individual factors of the test subject (left-handed a=0.08, right-handed a=0.12), and b is determined by the experimental equipment, with a statistical value of 0.16.

According to Equation (2), for left-handed drivers, JDA (MRT1=601.2ms, MRT2=477.6ms) is more suitable as the optimal valve position than JDC (MRT1=646.1ms, MRT2=520.6ms). Therefore, the optimal position for left-handed drivers is JDA (MRT1=601.2ms, MRT2=477.6ms), and the optimal position for right-handed drivers is JDC (MRT1=685.7ms, MRT2=560.2ms). When the constraint conditions are the same, the braking time for left-handed drivers is shorter than that for right-handed drivers (braking starts 83.6ms earlier). Assuming the train is traveling at full speed (350km/h), in the event of an emergency, left-handed drivers can provide at least an additional 8.135m of safety distance compared to right-handed drivers. In addition, under the same constraint conditions, the emergency braking error rate for left-handed drivers is 7.7‰ lower than that for right-handed drivers. In summary, during high-speed train travel, left-handed drivers’ emergency braking operations can better avoid accidents.