1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), represent a growing global health burden, particularly in the context of rapidly aging populations. AD is the leading cause of dementia, accounting for 60–80% of all cases [

1]. Dementia is a clinical syndrome marked by progressive cognitive decline that interferes with daily functioning, and AD progresses along a continuum—from preclinical stages to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and overt dementia [

2]. Two principal subtypes of AD are distinguished by age of onset: early-onset AD (EOAD), which typically occurs before age 65 and is often linked to autosomal dominant mutations (

APP, PSEN1, PSEN2) [

3], and late-onset AD (LOAD), which manifests after age 65 and comprises most cases [

4]. Unlike EOAD, LOAD is multifactorial, arising from a complex interplay of genetic predisposition (e.g.,

APOE ε4), environmental exposures, metabolic disturbances, and aging-related mechanisms. Importantly, LOAD may be considered a geriatric syndrome, reflecting its heterogeneity, multifactorial pathogenesis, and its primary risk factor—advanced age [

5] (

Table 1).

Over the years, several non-exclusive hypotheses have been proposed to explain AD pathophysiology [

6]. The amyloid cascade hypothesis suggests that extracellular aggregation of amyloid-β (Aβ) initiates a cascade of neurotoxic events, while the tau hypothesis emphasizes the role of hyperphosphorylated tau in neuronal dysfunction. More recently, attention has shifted to broader systemic contributors [

7]. The mitochondrial cascade hypothesis posits that age-related mitochondrial dysfunction is an early event promoting both Aβ and tau pathology. Parallel theories highlight the role of neuroinflammation and metabolic dysregulation, both of which intersect at the level of oxidative stress [

8]. Excessive production of reactive oxygen (ROS) and nitrogen species leads to cumulative damage to neuronal lipids, proteins, and DNA, particularly deleterious in neurons, given their high energy demand and limited regenerative capacity [

8,

9].

Within this oxidative and inflammatory milieu, advanced glycation end products (AGEs) have emerged as key mediators [

10]. Formed through non-enzymatic glycation and oxidation of proteins and lipids, AGEs accumulate with age and are elevated in AD brains. They promote protein cross-linking and structural alterations of Aβ and tau, enhancing their aggregation and neurotoxicity. Moreover, AGEs activate the receptor for AGEs (RAGE), initiating a feed-forward loop of ROS generation, NF-κB-mediated inflammation, and neuronal apoptosis [

11]. Mounting evidence suggests that AGE–RAGE signaling acts not only as a marker but as an upstream amplifier of the metabolic-inflammatory axis driving LOAD [

12,

13,

14]. This places AGEs at the intersection of systemic metabolic dysfunction (e.g., insulin resistance), neuroinflammation, and classical neuropathology.

This review aims to critically examine the metabolic dimension of Alzheimer’s disease, with particular emphasis on the interplay between oxidative stress and AGEs in the pathogenesis of LOAD. We seek to: 1) Elucidate the molecular and cellular mechanisms linking AGEs and oxidative stress to neurodegeneration, 2) Highlight AGE–RAGE signaling as a central node in aging-related metabolic and inflammatory dysfunction, and 3) Discuss emerging therapeutic strategies targeting AGE formation, detoxification, and receptor-mediated signaling in the context of AD.

2. Methodology

A comprehensive literature search was performed across PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science databases for studies published between January 2000 and May 2025, using combinations of the following keywords and MeSH terms: “Alzheimer’s disease,” “late-onset Alzheimer’s,” “oxidative stress,” “advanced glycation end products,” “AGEs,” “RAGE,” “neuroinflammation,” “mitochondrial dysfunction,” and “neurodegeneration.” We included original research articles (preclinical, clinical, and translational), systematic reviews, and meta-analyses published in English that explored mechanistic links between oxidative stress, AGEs, and Alzheimer’s pathology, while excluding case reports, editorials, and studies not directly addressing AD. Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts to assess eligibility, resolving discrepancies through consensus. Data extraction focused on AGE formation, AGE-RAGE signaling, oxidative stress pathways, and therapeutic implications. Due to heterogeneity in methodologies and outcomes, findings were synthesized narratively and organized thematically rather than through meta-analytic techniques.

3. Oxidative Stress and Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease

Oxidative stress refers to an imbalance between the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the capacity of antioxidant systems to neutralize them, resulting in molecular and cellular damage [

15]. ROS include both free radicals—such as superoxide anion (O₂⁻·) and hydroxyl radical (·OH)—and non-radical species like hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). These are primarily generated as byproducts of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and through enzymatic pathways involving NADPH oxidases, xanthine oxidase, and cytochrome P450 isoforms [

16]. Although physiologic levels of ROS contribute to redox signaling and immune defense, their excessive accumulation compromises cellular homeostasis. Table 2 shows the deleterious effects of free radicals on fundamental cellular components, including proteins, lipids, sugars, and DNA.

Table 2.

Cellular biomolecular targets and effects of free radicals lead to pathological conditions.

Table 2.

Cellular biomolecular targets and effects of free radicals lead to pathological conditions.

| Component |

Effects of Free Radicals |

| Proteins |

- Changes in amino acids

- Peptide chain breakage

- Protein denaturation

- Loss of activity |

| Lipids |

- Lipid peroxidation

- Alteration of membranes |

| Sugars |

- Glucose autoxidation |

| DNA |

- DNA breakage

- Base mutations

- Alteration of gene expression |

These reactive oxygen and nitrogen species interact with biomolecules, leading to a cascade of structural and functional impairments. In proteins, free radicals induce amino acid modifications, peptide chain breakage, and denaturation, ultimately resulting in a loss of biological activity. Lipid components, particularly polyunsaturated fatty acids in cellular membranes, undergo peroxidation, which compromises membrane integrity and fluidity. In the case of carbohydrates, glucose autoxidation generates reactive by-products that further propagate oxidative stress. DNA is particularly susceptible to oxidative insults, with consequences such as strand breaks, base mutations, and alterations in gene expression patterns. The cumulative damage to these macromolecules contributes to cell injury and tissue damage. Over time, such injuries can evolve into various pathological conditions, including neurodegenerative disorders [

17]. The central nervous system (CNS) is particularly vulnerable to oxidative insults due to its high oxygen consumption, abundance of polyunsaturated lipids, elevated metabolic rate, and limited antioxidant buffering capacity [

18]. Endogenous antioxidant defences include enzymatic systems—such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and peroxiredoxins—as well as non-enzymatic agents like reduced glutathione (GSH), vitamins C and E, and coenzyme Q10. These systems collectively preserve redox equilibrium and protect neuronal macromolecules from oxidative damage [

16,

17].

Excessive ROS promotes a cascade of neurotoxic events, starting with lipid peroxidation, which compromises neuronal membrane fluidity and function. Reactive aldehyde byproducts, notably 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) and malondialdehyde (MDA), impair ion homeostasis, membrane-bound receptors, and synaptic signaling. ROS also oxidatively modifies proteins, inducing carbonylation, nitration, and disulfide cross-linking [

19]. These changes disrupt protein folding, enzymatic activity, and accelerate aggregation. Oxidative modifications of tau and Aβ enhance their neurotoxicity and propensity to form pathological inclusions, contributing to synaptic and neuronal loss [

20]. Mitochondria are both a source and target of oxidative stress. ROS-induced damage to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)—which lacks protective histones and robust repair mechanisms—leads to impaired ATP synthesis, increased mitochondrial permeability, and further ROS production. This vicious cycle culminates in bioenergetic failure and apoptotic cell death, hallmark features of Alzheimer's pathology [

20,

21].

Oxidative damage is a pervasive and early event in neurodegenerative disease pathogenesis, including AD. Postmortem brain analyses consistently show elevated markers of lipid peroxidation (e.g., MDA, 4-HNE), protein oxidation (e.g., carbonylated proteins), and oxidative DNA damage (e.g., 8-OHdG) in the hippocampus and cortex [

22,

23,

24]. Amyloid-beta (Aβ) aggregates, through interactions with redox-active metals like Cu²⁺ and Fe²⁺, can catalyze ROS formation [

23]. In turn, Aβ-induced mitochondrial dysfunction further amplifies oxidative injury and promotes tau hyperphosphorylation [

25]. Thus, oxidative stress acts both upstream and downstream of hallmark AD lesions, potentiating neurodegenerative cascades and accelerating cognitive decline [

26].

4. Oxidative Stress and Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease

AGEs are a heterogeneous group of stable, irreversible compounds formed through the non-enzymatic Maillard reaction between reducing sugars and amino groups of proteins, lipids, or nucleic acids [

27]. Advancements in food chemistry have revealed that the Maillard reaction—particularly during thermal processing—produces end-products responsible for the complex flavors, aromas, and savory qualities characteristic of foods rich in sugars and proteins. The evolving Western diet has significantly increased the intake of ultra-processed foods, which are frequently enhanced with additives to improve palatability, texture, and shelf life. However, these additives, when subjected to heat, can participate in chemical reactions that promote the formation of AGEs. Concurrently, modern dietary patterns are marked by elevated levels of sugars and fats, alongside widespread use of protein supplements aimed at supporting muscle growth. Coupled with sedentary behavior, these lifestyle shifts have been implicated in the rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases. Consequently, there is growing scientific interest in elucidating the molecular and metabolic pathways underlying conditions such as biological processes associated with aging [

27]. Additionally, AGEs may also form via oxidative mechanisms, particularly when ROS interacts with intermediate metabolic compounds. These oxidative modifications can parallel reactions in which lipid peroxidation by-products bind to protein amino groups, giving rise to structurally analogous compounds known as advanced lipoxidation end-products (ALEs) [

28].

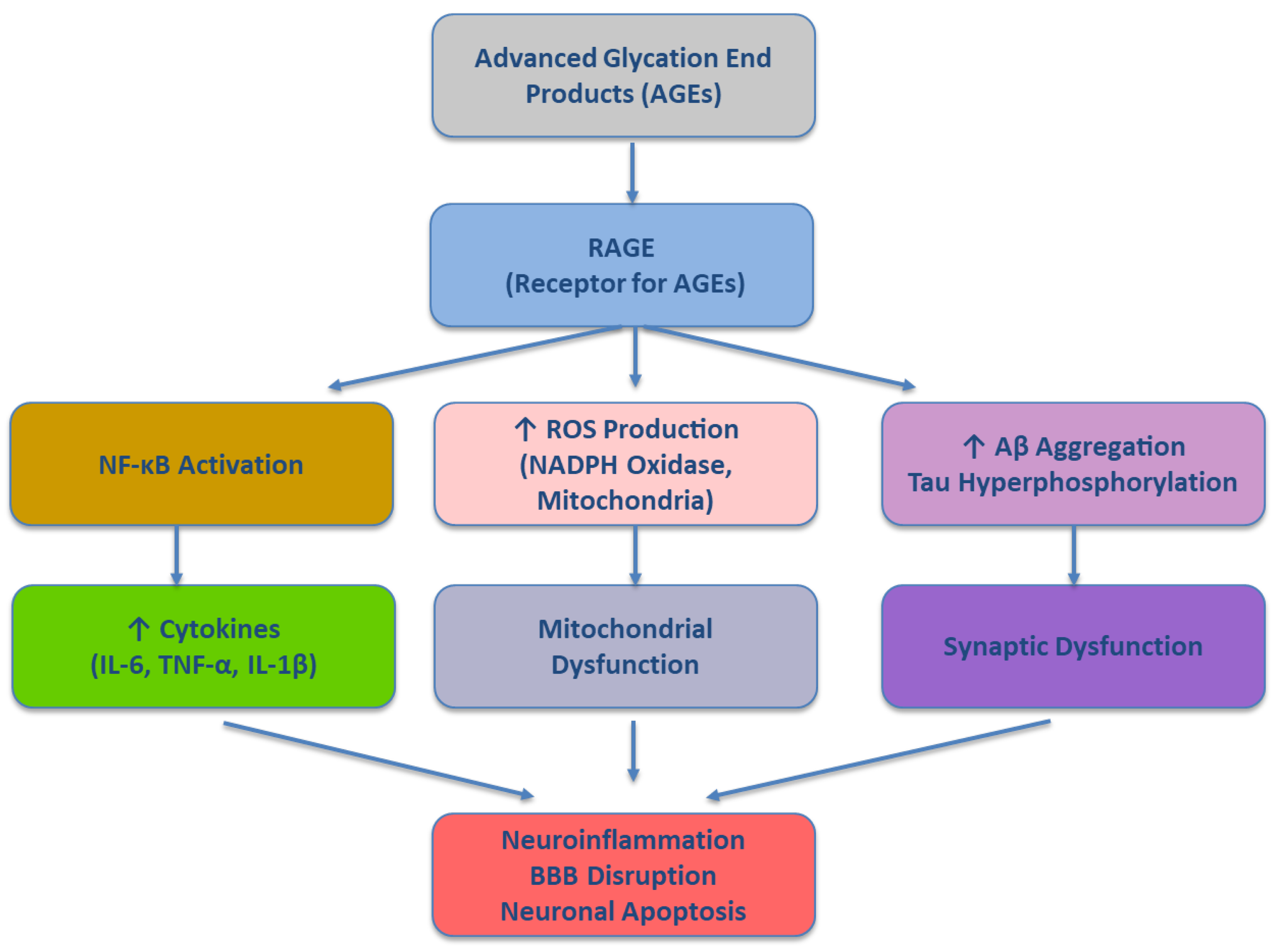

AGEs and oxidative stress exist in a mutually reinforcing loop. Oxidative conditions accelerate AGE formation, while AGEs themselves enhance ROS production through activation of RAGE. Elevated concentrations of AGEs, together with heightened expression of their primary receptor, RAGE, within tissues, can trigger and intensify various pathological processes. This occurs through the upregulation of gene transcription linked to proinflammatory cytokines and signaling molecules, ultimately leading to dysregulated protein synthesis and sustained inflammatory responses [

29]. RAGE is expressed on neurons, microglia, astrocytes, and endothelial cells. Its activation triggers intracellular signaling cascades—including NADPH oxidase activation, mitochondrial ROS generation, and NF-κB translocation—culminating in a chronic pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative state [

30]. This feed-forward mechanism contributes to sustained redox imbalance, glial activation, and neuronal apoptosis, all of which are observed in the Alzheimer’s brain. Moreover, AGEs can modify critical proteins such as Aβ and tau, enhancing their aggregation and neurotoxicity. AGE-modified tau shows increased resistance to degradation and higher propensity for misfolding and fibril formation, promoting the formation of neurofibrillary tangles [

31].

The AGE–RAGE interaction acts as a central node linking metabolic dysfunction, oxidative stress, and inflammation in AD [

29,

31]. This ligand–receptor engagement initiates a cascade of intracellular signaling that amplifies pathological processes fundamental to AD. Specifically, the AGE–RAGE axis contributes to increased amyloidogenic processing of APP, Tau hyperphosphorylation, mitochondrial dysfunction and autophagic impairment and cerebrovascular injury, and blood–brain barrier (BBB) compromise. Binding of AGEs to RAGE upregulates β-secretase (BACE1) activity, leading to enhanced production of amyloid-β (Aβ) [

32]. Concurrently, RAGE-mediated dysfunction of microglial phagocytosis impairs Aβ clearance, fostering extracellular plaque accumulation [

33]. Activation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) downstream of RAGE promotes aberrant phosphorylation of tau proteins [

34]. This modification destabilizes microtubules and supports neurofibrillary tangle formation—a hallmark of AD pathology. AGE–RAGE signaling disrupts mitochondrial dynamics and bioenergetics, leading to elevated ROS production [

35]. It also inhibits autophagic flux, thereby preventing the clearance of damaged organelles and aggregated proteins, further compromising neuronal homeostasis. RAGE expression on endothelial cells mediates vascular inflammation and promotes leukocyte adhesion and transmigration [

36]. This activity, coupled with matrix metalloproteinase activation, facilitates BBB breakdown, which exacerbates neuroinflammation and facilitates peripheral immune cell infiltration into the CNS [

37]. Clinical and post-mortem studies underscore the translational relevance of this pathway. Elevated levels of AGEs and RAGE have been consistently observed in the brain parenchyma, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and plasma of AD patients (Reviewed in Koerich et al., 2023). Notably, the extent of their upregulation correlates with cognitive decline and pathological burden, implicating the AGE–RAGE axis as more than a mere bystander. Rather, it emerges as a central pathogenic driver in late-onset AD, offering a compelling target for therapeutic intervention. Collectively, the AGE–RAGE signaling cascade involves multiple pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory nodes that contribute to the neurodegenerative processes characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. A schematic overview of this molecular pathway is presented in

Figure 1.

5. The AGE–RAGE Axis as a Central Node in Aging-Related Metabolic and Inflammatory Dysfunction

The interaction between AGEs and their main receptor, RAGE, constitutes a central mechanism linking oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and metabolic dysregulation in aging and age-related diseases. RAGE is a multiligand pattern recognition receptor belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily and is expressed in neurons, microglia, astrocytes, endothelial cells, and peripheral immune cells [

39,

40]. While minimally expressed under physiological conditions, RAGE is markedly upregulated in aging tissues, particularly in response to increased AGE accumulation [

41]. Upon ligand binding, the AGE–RAGE interaction initiates intracellular signaling cascades that lead to activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), NADPH oxidase, and downstream proinflammatory transcriptional programs. This results in the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β), and adhesion molecules (e.g., ICAM-1, VCAM-1), which together foster a sustained state of inflammaging—a chronic, low-grade inflammation characteristic of biological aging [

39,

41]. The AGE–RAGE axis also plays a pivotal role in systemic metabolic dysfunction. AGEs impair insulin signaling and pancreatic β-cell viability, contributing to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes—two well-established risk factors for LOAD [

42]. RAGE activation in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle disrupts glucose uptake and mitochondrial function, amplifying oxidative stress and impairing cellular metabolism. In the brain, insulin resistance and impaired glucose metabolism have been observed in early AD, often referred to as "type 3 diabetes." [

43] AGE–RAGE signaling exacerbates these defects by interfering with insulin receptor substrate phosphorylation and promoting inflammatory cytokine release that inhibits insulin signaling pathways. This positions the AGE–RAGE axis as a mechanistic bridge between systemic metabolic impairment and central neurodegeneration. In the CNS, AGE–RAGE signaling promotes neuroinflammation through sustained microglial and astrocytic activation [

44,

45]. Microglia exposed to AGEs adopt a proinflammatory M1 phenotype, releasing ROS and cytokines that damage synapses and neurons. Astrocytes respond by downregulating neurotrophic support and enhancing glutamate excitotoxicity. These glial responses further compromise neuronal viability and synaptic plasticity [

45,

46]. Moreover, RAGE expression on cerebral endothelial cells contributes to blood–brain barrier (BBB) breakdown, allowing peripheral inflammatory mediators and circulating AGEs to enter the brain parenchyma [

47]. BBB disruption is a key early event in AD pathogenesis and facilitates further Aβ deposition, tau pathology, and metabolic toxicity [

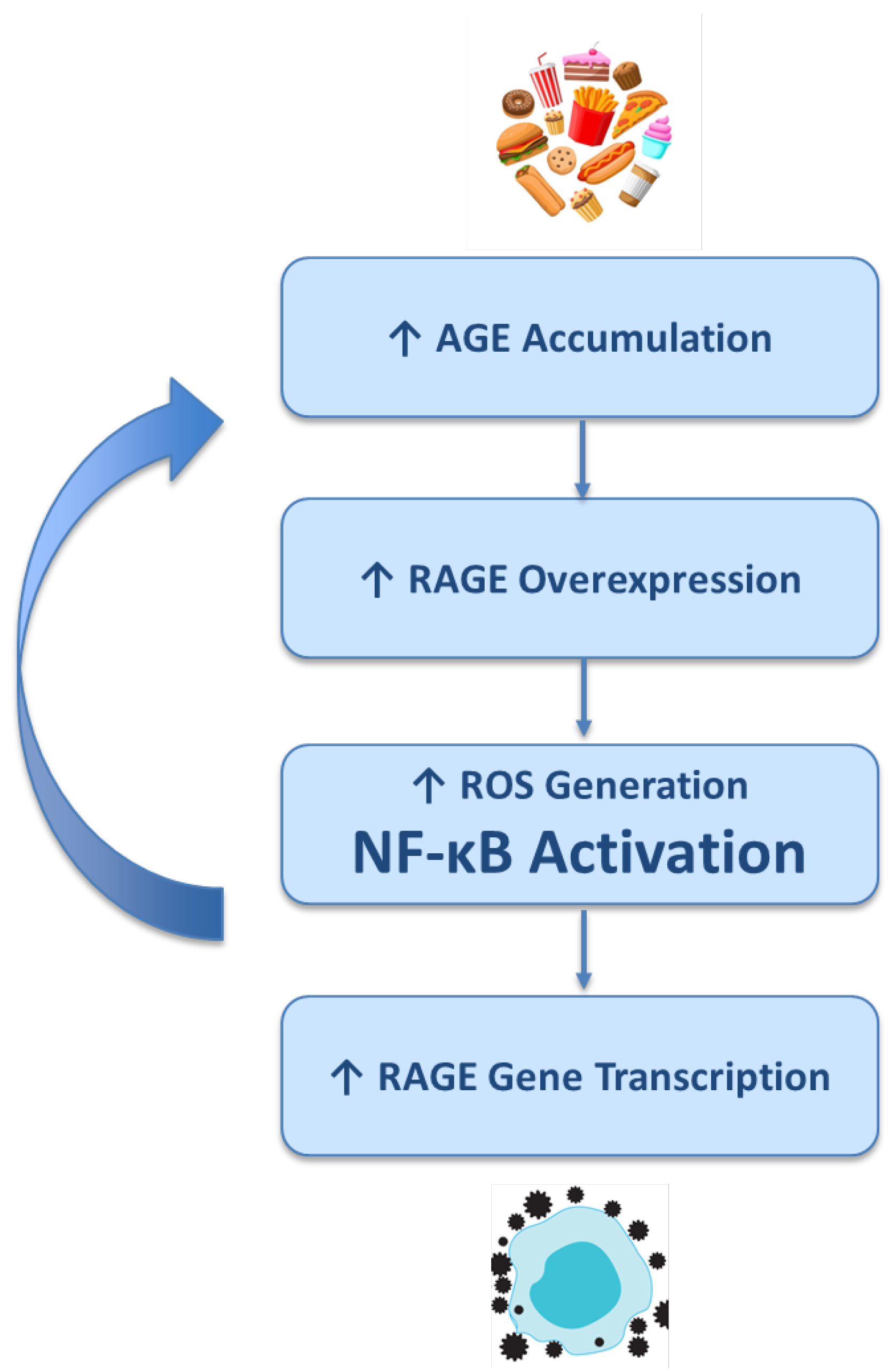

48]. Crucially, AGE–RAGE signaling operates within a feed-forward loop, as shown in

Figure 2. Increased accumulation of AGEs leads to the overexpression of their receptor, RAGE. This upregulation facilitates the generation of ROS and the activation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB. In turn, NF-κB enhances the transcription of the RAGE gene itself, establishing a self-perpetuating cycle. This vicious loop sustains chronic inflammation and oxidative stress, which in turn reinforce peripheral metabolic dysfunction (such as insulin resistance and endothelial impairment) and exacerbate central neurodegenerative cascades, contributing to the progression of age-related diseases. This dynamic creates a pathophysiological continuum in which AGE–RAGE signaling not only reflects cumulative metabolic damage but actively drives the transition from normal aging to pathological aging, including the onset and progression of LOAD.

6. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting AGE Formation, Detoxification, and RAGE Signaling in AD

Given the central role of AGEs and AGE–RAGE signaling in AD pathophysiology—particularly in LOAD—several pharmacological and nutraceutical strategies have been proposed to mitigate their deleterious effects. These approaches target various stages of the AGE cascade, from preventing AGE formation and promoting their detoxification to inhibiting receptor-mediated downstream signaling (

Table 3).

6.1. Inhibitors of AGE Formation

AGE formation can be attenuated by agents that interfere with early steps of the Maillard reaction or that scavenge reactive carbonyl intermediates. Aminoguanidine, one of the earliest AGE inhibitors, traps reactive carbonyl species and prevents cross-linking of proteins. While preclinical studies showed neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects, its clinical development was halted due to adverse events (e.g., liver toxicity) [

49]. Pyridoxamine, a form of vitamin B6, acts as a carbonyl scavenger and metal chelator, showing promising results in diabetic and nephropathic models [

50]. Although limited data exist in AD, its dual antioxidant and anti-glycation properties offer theoretical potential. ALT-711 (Alagebrium), a cross-link breaker that reverses AGE-related protein modifications, showed efficacy in improving vascular compliance in cardiovascular disease [

50] and has been proposed for investigation in neurodegenerative contexts.

6.2. Enhancing AGE Detoxification and Clearance

The body possesses endogenous detoxification systems for AGE intermediates, notably the glyoxalase pathway, which degrades reactive dicarbonyls such as methylglyoxal. Glyoxalase-1 (GLO1) activation: Experimental upregulation of GLO1 in mouse models has been shown to reduce AGE accumulation, oxidative stress, and improve cognitive outcomes [

51]. Agents that enhance GLO1 activity (e.g., sulforaphane, resveratrol) are under investigation for their neuroprotective potential. Glutathione (GSH), a key intracellular antioxidant, supports AGE detoxification indirectly by reducing dicarbonyl stress. GSH depletion has been documented in AD brains, suggesting that GSH replenishment (via precursors such as N-acetylcysteine or dietary interventions) could modulate AGE load and redox balance [

52].

6.3. RAGE Antagonists and Receptor-Targeted Therapies

A major focus of drug development has been the inhibition of AGE–RAGE interaction and its intracellular consequences. Azeliragon (TTP488), an oral RAGE antagonist, reached phase II/III clinical trials for mild Alzheimer’s disease. Although early trials indicated potential benefits in reducing cognitive decline and inflammation, subsequent phase III results were inconclusive, prompting ongoing interest in better-targeted or combinatorial approaches [

53]. FPS-ZM1, a high-affinity RAGE inhibitor, successfully crosses the blood–brain barrier and has shown promise in preclinical AD models [

54]. It reduces Aβ influx into the brain, suppresses RAGE-mediated inflammatory signaling, and preserves synaptic function. Further studies are needed to translate these findings into clinical applications [

55]. sRAGE (soluble RAGE) functions as a decoy receptor, binding circulating AGEs and preventing them from activating membrane-bound RAGE. Reduced sRAGE levels have been reported in patients with AD, and strategies to boost endogenous sRAGE or administer recombinant forms are being explored [

56].

6.4. Nutritional and Lifestyle Interventions

Dietary AGEs, derived from high-temperature cooking (grilled, fried, roasted foods), significantly contribute to systemic AGE burden [

57]. Clinical and observational studies suggest that low-AGE diets, rich in raw or steamed vegetables, whole grains, and low-glycemic foods, may reduce circulating AGEs and improve markers of inflammation and cognition in older adults [

58,

59]. Polyphenols, such as curcumin, quercetin, and resveratrol, exhibit dual activity as antioxidants and glycation inhibitors [

60]. These compounds attenuate AGE formation, modulate RAGE expression, and suppress downstream inflammatory signaling[

61]. While their bioavailability and pharmacokinetics remain a challenge, formulations with enhanced absorption (e.g., liposomal curcumin) are under investigation [

62]. Physical exercise, by improving mitochondrial function, insulin sensitivity, and antioxidant capacity, may also reduce AGE accumulation indirectly, highlighting the importance of multimodal lifestyle interventions in modulating the AGE–RAGE axis in AD [

63,

64].

7. Conclusions

Despite encouraging preclinical evidence, the clinical translation of therapies targeting AGEs in AD remains limited. Several critical challenges impede progress, including: (i) the structural and functional heterogeneity of AGEs, which complicates the development of selective interventions; (ii) the absence of reliable biomarkers to quantify AGE burden and RAGE (receptor for AGEs) signaling activity within the central nervous system; and (iii) the need for early therapeutic intervention, given that AGE–RAGE-mediated damage likely precedes clinical onset by decades. Nonetheless, innovative strategies such as nanocarrier-based drug delivery systems, gene therapies aimed at modulating RAGE expression, and combinatorial approaches that simultaneously target metabolic, inflammatory, and oxidative stress pathways are emerging as promising avenues to overcome current limitations. Therapeutic disruption of the AGE–RAGE axis holds significant potential for attenuating neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic dysfunction—key pathological features of AD. While no AGE-specific interventions have yet gained regulatory approval for clinical use in AD, converging lines of experimental, clinical, and epidemiological evidence underscore the translational relevance of this pathway.

Future research should prioritize the design of mechanistically informed clinical trials, the development of reliable AGE–RAGE biomarkers for early detection and stratification, and the incorporation of glycation profiles into precision medicine frameworks. Moreover, combination therapies that concurrently target glycation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and chronic inflammation may offer synergistic benefits, particularly in the early stages of LOAD.

7.1. Open Research Questions

Despite mounting preclinical support for targeting the AGE–RAGE axis in AD, several pivotal questions remain unresolved. First, how can we systematically classify and characterize the diverse species of AGEs to enable selective therapeutic targeting? Second, what reliable and sensitive biomarkers can be developed to quantify AGE accumulation and RAGE activation in vivo, particularly within the human brain? Third, at what temporal window would AGE and AGE-RAGE-directed interventions yield maximal clinical efficacy, especially considering the likely preclinical onset of AGE-related pathology? Fourth, can emerging modalities such as nanotechnology, gene editing, or multi-target drug platforms achieve sufficient specificity, brain penetration, and safety for long-term intervention? Lastly, how can glycation-related mechanisms be effectively integrated into broader precision medicine strategies for Alzheimer’s disease, particularly in the heterogeneous context of late-onset forms? Addressing these questions will be critical for translating promising molecular insights into tangible clinical applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.B.; Data Curation, V.B.; Formal Analysis, V.B., F.M., P.M.; Investigation, V.B., F.M.; Methodology, V.B., P.M.; Project Administration, V.B.; Resources, V.B.; Supervision, V.B.; Validation, P.M., V.B.; Writing – Original Draft, V.B.; Writing – Review & Editing, V.B.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

References

- Wang, S.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, A.; Meng, F.; Zhang, J. The Expanding Burden of Neurodegenerative Diseases: An Unmet Medical and Social Need. Aging Dis 2024, 0-. [CrossRef]

- Kamatham, P.T.; Shukla, R.; Khatri, D.K.; Vora, L.K. Pathogenesis, Diagnostics, and Therapeutics for Alzheimer’s Disease: Breaking the Memory Barrier. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 101, 102481. [CrossRef]

- Mendez, M.F. Early-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease: Nonamnestic Subtypes and Type 2 AD. Arch Med Res 2012, 43, 677–685. [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Gaxiola, C.A.; Rosales-Leycegui, F.; Gaxiola-Rubio, A.; Moreno-Ortiz, J.M.; Figuera, L.E.; Valdez-Gaxiola, C.A.; Rosales-Leycegui, F.; Gaxiola-Rubio, A.; Moreno-Ortiz, J.M.; Figuera, L.E. Early- and Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease: Two Sides of the Same Coin? Diseases 2024, Vol. 12, Page 110 2024, 12, 110. [CrossRef]

- Mecocci, P.; Baroni, M.; Senin, U.; Boccardi, V. Brain Aging and Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease: A Matter of Increased Amyloid or Reduced Energy? Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 2018, 64, S397–S404. [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Gortaire, J.; Ruiz, A.; Porto-Pazos, A.B.; Rodriguez-Yanez, S.; Cedron, F. Alzheimer’s Disease: Exploring Pathophysiological Hypotheses and the Role of Machine Learning in Drug Discovery. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, Vol. 26, Page 1004 2025, 26, 1004. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.S.; Kabir, M.T.; Rahman, M.S.; Behl, T.; Jeandet, P.; Ashraf, G.M.; Najda, A.; Bin-Jumah, M.N.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Revisiting the Amyloid Cascade Hypothesis: From Anti-Aβ Therapeutics to Auspicious New Ways for Alzheimer’s Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 5858. [CrossRef]

- Kazemeini, S.; Nadeem-Tariq, A.; Shih, R.; Rafanan, J.; Ghani, N.; Vida, T.A. From Plaques to Pathways in Alzheimer’s Disease: The Mitochondrial-Neurovascular-Metabolic Hypothesis. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 11720. [CrossRef]

- Botella Lucena, P.; Heneka, M.T. Inflammatory Aspects of Alzheimer’s Disease. Acta Neuropathol 2024, 148. [CrossRef]

- Kothandan, D.; Singh, D.S.; Yerrakula, G.; D, B.; N, P.; B, V.S.S.; A, R.; VG, S.R.; S, K.; M, J. Advanced Glycation End Products-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease and Its Novel Therapeutic Approaches: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e61373. [CrossRef]

- Fornai, F.; Li, W.; Chen, Q.; Peng, C.; Yang, D.; Liu, S.; Lv, Y.; Jiang, L.; Xu, S.; Huang, L. Roles of the Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products and Its Ligands in the Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Vitorakis, N.; Piperi, C. Pivotal Role of AGE-RAGE Axis in Brain Aging with Current Interventions. Ageing Res Rev 2024, 100, 102429. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mooldijk, S.S.; Licher, S.; Waqaz, K.; Ikram, M.K.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Zillikens, M.C. Advanced Glycation End Products, Their Receptor and the Risk of Dementia in the General Population: A Prospective Cohort Study. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2020, 16, e043005. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mooldijk, S.S.; Licher, S.; Waqas, K.; Ikram, M.K.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Zillikens, M.C.; Ikram, M.A. Assessment of Advanced Glycation End Products and Receptors and the Risk of Dementia. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4. [CrossRef]

- Schieber, M.; Chandel, N.S. ROS Function in Redox Signaling and Oxidative Stress. Curr Biol 2014, 24, R453. [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Toxicity, Oxidative Stress, and Antioxidants: Chronic Diseases and Aging. Arch Toxicol 2023, 97, 2499. [CrossRef]

- Martemucci, G.; Costagliola, C.; Mariano, M.; D’andrea, L.; Napolitano, P.; D’Alessandro, A.G. Free Radical Properties, Source and Targets, Antioxidant Consumption and Health. Oxygen 2022, Vol. 2, Pages 48-78 2022, 2, 48–78. [CrossRef]

- Timalsina, D.R.; Abichandani, L.; Ambad, R. A Review Article on Oxidative Stress Markers F2-Isoprostanes and Presenilin-1 in Alzheimer’s Disease. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2025, 17, S109–S112. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Jung, U.J.; Kim, S.R. Role of Oxidative Stress in Blood–Brain Barrier Disruption and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants 2024, Vol. 13, Page 1462 2024, 13, 1462. [CrossRef]

- Olufunmilayo, E.O.; Gerke-Duncan, M.B.; Holsinger, R.M.D. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidants in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Antioxidants 2023, Vol. 12, Page 517 2023, 12, 517. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wuliji, O.; Li, W.; Jiang, Z.G.; Ghanbari, H.A. Oxidative Stress and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 24438–24475. [CrossRef]

- Yoritaka, A.; Hattori, N.; Uchida, K.; Tanaka, M.; Stadtman, E.R.; Mizuno, Y. Immunohistochemical Detection of 4-Hydroxynonenal Protein Adducts in Parkinson Disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1996, 93, 2696–2701. [CrossRef]

- Gabbita, S.P.; Lovell, M.A.; Markesbery, W.R. Increased Nuclear DNA Oxidation in the Brain in Alzheimer’ s Disease. J Neurochem 1998, 71, 2034–2040. [CrossRef]

- Alam, Z.I.; Jenner, A.; Daniel, S.E.; Lees, A.J.; Cairns, N.; Marsden, C.D.; Jenner, P.; Halliwell, B. Oxidative DNA Damage in the Parkinsonian Brain: An Apparent Selective Increase in 8-Hydroxyguanine Levels in Substantia Nigra. J Neurochem 1997, 69, 1196–1203. [CrossRef]

- Rajmohan, R.; Reddy, P.H. Amyloid Beta and Phosphorylated Tau Accumulations Cause Abnormalities at Synapses of Alzheimer’s Disease Neurons. J Alzheimers Dis 2017, 57, 975. [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.G.; Mandal, P.K.; Maroon, J.C. Oxidative Stress Occurs Prior to Amyloid Aβ Plaque Formation and Tau Phosphorylation in Alzheimer’s Disease: Role of Glutathione and Metal Ions. ACS Chem Neurosci 2023, 14, 2944–2954. [CrossRef]

- Twarda-clapa, A.; Olczak, A.; Białkowska, A.M.; Koziołkiewicz, M. Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs): Formation, Chemistry, Classification, Receptors, and Diseases Related to AGEs. Cells 2022, 11, 1312. [CrossRef]

- Moldogazieva, N.T.; Mokhosoev, I.M.; Mel’Nikova, T.I.; Porozov, Y.B.; Terentiev, A.A. Oxidative Stress and Advanced Lipoxidation and Glycation End Products (ALEs and AGEs) in Aging and Age-Related Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Prasad, K. AGE–RAGE Stress: A Changing Landscape in Pathology and Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Cell Biochem 2019, 459, 95–112. [CrossRef]

- Ballard, C.; Gauthier, S.; Corbett, A.; Brayne, C.; Aarsland, D.; Jones, E. Alzheimer’s Disease. The Lancet 2011, 377, 1019–1031. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Liu, N.; Wang, C.; Qin, B.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, M.; Chang, L.; Yan, L.J.; Zhao, B. Role of RAGE in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2016, 36, 483–495. [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.H.; Hong, S.; Kim, E.; Park, S.; Lee, M.; Park, J.; Cho, Y.; Yoon, H.; Kim, D.; Yun, Y.; et al. A Novel RAGE Modulator Induces Soluble RAGE to Reduce BACE1 Expression in Alzheimer’s Disease. Advanced Science 2025, 12, 2407812. [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Lue, L.-F.; Yan, S.; Xu, H.; Luddy, J.S.; Chen, D.; Walker, D.G.; Stern, D.M.; Yan, S.; Schmidt, A.M.; et al. RAGE-Dependent Signaling in Microglia Contributes to Neuroinflammation, Aβ Accumulation, and Impaired Learning/Memory in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. The FASEB Journal 2010, 24, 1043. [CrossRef]

- DaRocha-Souto, B.; Coma, M.; Pérez-Nievas, B.G.; Scotton, T.C.; Siao, M.; Sánchez-Ferrer, P.; Hashimoto, T.; Fan, Z.; Hudry, E.; Barroeta, I.; et al. Activation of Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 Beta Mediates β-Amyloid Induced Neuritic Damage in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurobiol Dis 2011, 45, 425. [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, M.C.B.; Kanaan, S.; Geller, M.; Praticò, D.; Daher, J.P.L. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ageing Res Rev 2025, 107, 102713. [CrossRef]

- Kierdorf, K.; Fritz, G. RAGE Regulation and Signaling in Inflammation and Beyond. J Leukoc Biol 2013, 94, 55–68. [CrossRef]

- Takata, F.; Nakagawa, S.; Matsumoto, J.; Dohgu, S. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction Amplifies the Development of Neuroinflammation: Understanding of Cellular Events in Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells for Prevention and Treatment of BBB Dysfunction. Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15, 661838. [CrossRef]

- Koerich, S.; Parreira, G.M.; Almeida, D.L. de; Vieira, R.P.; Oliveira, A.C.P. de Receptors for Advanced Glycation End Products (RAGE): Promising Targets Aiming at the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Conditions. Curr Neuropharmacol 2023, 21, 219. [CrossRef]

- Fritz, G. RAGE: A Single Receptor Fits Multiple Ligands. Trends Biochem Sci 2011, 36, 625–632. [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Deng, H. Pathophysiology of RAGE in Inflammatory Diseases. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 931473. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, L.; Li, L.; Zhang, D.; Gong, Z.; Wu, Q. Activation and Modulation of the AGEs-RAGE Axis: Implications for Inflammatory Pathologies and Therapeutic Interventions – A Review. Pharmacol Res 2024, 206, 107282. [CrossRef]

- Affuso, F.; Micillo, F.; Fazio, S. Insulin Resistance, a Risk Factor for Alzheimer’s Disease: Pathological Mechanisms and a New Proposal for a Preventive Therapeutic Approach. Biomedicines 2024, Vol. 12, Page 1888 2024, 12, 1888. [CrossRef]

- Lemche, E.; Killick, R.; Mitchell, J.; Caton, P.W.; Choudhary, P.; Howard, J.K. Molecular Mechanisms Linking Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Late-Onset Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Qualitative Meta-Analysis. Neurobiol Dis 2024, 196, 106485. [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Lue, L.-F.; Yan, S.; Xu, H.; Luddy, J.S.; Chen, D.; Walker, D.G.; Stern, D.M.; Yan, S.; Schmidt, A.M.; et al. RAGE-Dependent Signaling in Microglia Contributes to Neuroinflammation, Aβ Accumulation, and Impaired Learning/Memory in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. The FASEB Journal 2010, 24, 1043. [CrossRef]

- Valiukas, Z.; Tangalakis, K.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Feehan, J. Microglial Activation States and Their Implications for Alzheimer’s Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2025, 12, 100013. [CrossRef]

- Wendimu, M.Y.; Hooks, S.B. Microglia Phenotypes in Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 2091. [CrossRef]

- Wan, W.; Chen, H.; Li, Y. The Potential Mechanisms of Aβ-Receptor for Advanced Glycation End-Products Interaction Disrupting Tight Junctions of the Blood-Brain Barrier in Alzheimer’s Disease. International Journal of Neuroscience 2014, 124, 75–81. [CrossRef]

- Takata, F.; Nakagawa, S.; Matsumoto, J.; Dohgu, S. Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction Amplifies the Development of Neuroinflammation: Understanding of Cellular Events in Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cells for Prevention and Treatment of BBB Dysfunction. Front Cell Neurosci 2021, 15, 661838. [CrossRef]

- Thornalley, P.J. Use of Aminoguanidine (Pimagedine) to Prevent the Formation of Advanced Glycation Endproducts. Arch Biochem Biophys 2003, 419, 31–40. [CrossRef]

- Ooi, H.; Nasu, R.; Furukawa, A.; Takeuchi, M.; Koriyama, Y. Pyridoxamine and Aminoguanidine Attenuate the Abnormal Aggregation of β-Tubulin and Suppression of Neurite Outgrowth by Glyceraldehyde-Derived Toxic Advanced Glycation End-Products. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 921611. [CrossRef]

- Berends, E.; Pencheva, M.G.; van de Waarenburg, M.P.H.; Scheijen, J.L.J.M.; Hermes, D.J.H.P.; Wouters, K.; van Oostenbrugge, R.J.; Foulquier, S.; Schalkwijk, C.G. Glyoxalase 1 Overexpression Improves Neurovascular Coupling and Limits Development of Mild Cognitive Impairment in a Mouse Model of Type 1 Diabetes. Journal of Physiology 2024, 602. [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Urban, C.; Berbaum, K.; Loske, C.; Alpar, A.; Gärtner, U.; De Arriba, S.G.; Arendt, T.; Münch, G. The Carbonyl Scavengers Aminoguanidine and Tenilsetam Protect against the Neurotoxic Effects of Methylglyoxal. Neurotox Res 2005, 7, 95–101. [CrossRef]

- Burstein, A.H.; Sabbagh, M.; Andrews, R.; Valcarce, C.; Dunn, I.; Altstiel, L. Development of Azeliragon, an Oral Small Molecule Antagonist of the Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts, for the Potential Slowing of Loss of Cognition in Mild Alzheimer’s Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis 2018, 5, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Deane, R.; Singh, I.; Sagare, A.P.; Bell, R.D.; Ross, N.T.; LaRue, B.; Love, R.; Perry, S.; Paquette, N.; Deane, R.J.; et al. A Multimodal RAGE-Specific Inhibitor Reduces Amyloid β-Mediated Brain Disorder in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer Disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2012, 122, 1377–1392. [CrossRef]

- Crunkhorn, S. Neurodegenerative Disease: Taming the RAGE of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012, 11, 351. [CrossRef]

- Erusalimsky, J.D. The Use of the Soluble Receptor for Advanced Glycation-End Products (SRAGE) as a Potential Biomarker of Disease Risk and Adverse Outcomes. Redox Biol 2021, 42, 101958. [CrossRef]

- Uribarri, J.; Woodruff, S.; Goodman, S.; Cai, W.; Chen, X.; Pyzik, R.; Yong, A.; Striker, G.E.; Vlassara, H. Advanced Glycation End Products in Foods and a Practical Guide to Their Reduction in the Diet. J Am Diet Assoc 2010, 110, 911. [CrossRef]

- Garay-Sevilla, M.E.; Rojas, A.; Portero-Otin, M.; Uribarri, J. Dietary AGEs as Exogenous Boosters of Inflammation. Nutrients 2021, Vol. 13, Page 2802 2021, 13, 2802. [CrossRef]

- J, W.; E, V.; A, D.; S, H.; J, V.; J, V.; R, V.; M, D.; B, V.; M, F.; et al. Cooking Methods Affect Advanced Glycation End Products and Lipid Profiles: A Randomized Cross-over Study in Healthy Subjects. Cell Rep Med 2025, 6. [CrossRef]

- González, I.; Morales, M.A.; Rojas, A. Polyphenols and AGEs/RAGE Axis. Trends and Challenges. Food Research International 2020, 129. [CrossRef]

- Aatif, M. Current Understanding of Polyphenols to Enhance Bioavailability for Better Therapies. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2078. [CrossRef]

- Brimson, J.M.; Prasanth, M.I.; Malar, D.S.; Thitilertdecha, P.; Kabra, A.; Tencomnao, T.; Prasansuklab, A. Plant Polyphenols for Aging Health: Implication from Their Autophagy Modulating Properties in Age-Associated Diseases. Pharmaceuticals 2021, Vol. 14, Page 982 2021, 14, 982. [CrossRef]

- Małkowska, P. Positive Effects of Physical Activity on Insulin Signaling. Current Issues in Molecular Biology 2024, Vol. 46, Pages 5467-5487 2024, 46, 5467–5487. [CrossRef]

- Clemente-Suárez, V.J.; Rubio-Zarapuz, A.; Belinchón-deMiguel, P.; Beltrán-Velasco, A.I.; Martín-Rodríguez, A.; Tornero-Aguilera, J.F. Impact of Physical Activity on Cellular Metabolism Across Both Neurodegenerative and General Neurological Conditions: A Narrative Review. Cells 2024, 13, 1940. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).