1. Introduction

Accurate correspondence of neuroanatomical shapes under non-rigid deformations is a fundamental prerequisite for numerous applications in computational neuroimaging, including the mapping of morphological biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases [

1], quantification of cortical asymmetries [

2] and the fusion of multimodal imaging data such as fMRI and tractography [

3]. Manual or semi-automated alignment procedures are time-consuming and prone to operator bias, motivating the development of fully automated, scalable registration algorithms capable of handling the complex variability inherent in brain structures.

Conventional surface-based methods are related to Iterative Closest Point (ICP) [

4] and spectral-descriptor matching [

5] which evidence local geometric cues but often converge to suboptimal local minima and exhibit sensitivity to mesh discretization and symmetry. Recent graph-based approaches incorporate topological invariants or diffusion-based features [

6,

7]. Nevertheless, they typically model structural (connectivity) and spatial (Euclidean distance) information in isolation, resulting in fragmented cost functions and inconsistent correspondences under partial occlusion or non-isometric deformations [

8].

To address these challenges, we propose the Dynamic Graph Analyzer (DGA), a unified hybrid framework that (1) integrates simplified structural descriptors -node degree weighted by betweenness centrality and local clustering coefficients [

9,

10]- with a two-stage spatial scheme combining global maximum distances and local rescaling [

11], (2) casts correspondence as a global linear assignment problem solved by the Kuhn-Munkres algorithm [

12] and (3) and 3 resets weak descriptor mappings to a new descriptor subject to rigid transformations [

13].

By embedding structural and spatial affinities into a single cost matrix, DGA guarantees global optimality, eliminates the need for post hoc regularization, and achieves complexity optimized via edge and node decimation-pruning.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

We introduce a scalable descriptor integration strategy that captures essential topological patterns and preserves intrinsic geometry without excessive computational overhead.

We formulate brain-shape correspondence as a globally optimal assignment problem, leveraging the Kuhn-Munkres algorithm to balance connectivity and spatial coherence.

We propose a probabilistic re-adjustment to weak correspondences (very different descriptors) through the application of optimal rigid transformations and the computation of a new descriptor.

We validate DGA on multiple benchmarks—achieving a 33.5% reduction in mean geodesic error on FAUST, robust partial-shape matching on TOSCA, and accurate cross-species alignment on SHREC-20, demonstrating resilience to morphological variability and symmetry ambiguities.

2. Related Work

The problem of nonrigid shape correspondence has been studied extensively, from classical geometric alignment to recent deep learning approaches. Early methods, such as Iterative Closest Point (ICP) [

4], iteratively align point clouds by minimizing local point-to-point distances but suffer from sensitivity to initialization, mesh discretization, and symmetry, often converging to suboptimal local minima. Spectral-descriptor techniques employ intrinsic shape signatures—such as heat-kernel signatures or spherical harmonics—to establish correspondences that are independent of rigid motions. Comparative surveys demonstrate that approaches based on spectral embeddings [

14] and harmonic descriptors [

15] achieve robustness to nonrigid deformations but can be computationally intensive and fail under substantial topological variation.

Graph-based registration methods seek to leverage the connectivity structure of mesh vertices. Diffusion-based descriptors [

16] encode local topology via heat-flow features. In contrast, anisotropic multi-scale graph convolutions [

7] and relation-constrained capsule graph networks [

6] learn to propagate information across edges for dense matching. FeastNet [

17] extends classical graph convolutions by steering filters according to local frames, improving performance on deformable shapes. Nevertheless, these models typically treat structural (connectivity) and spatial (Euclidean) relations separately, resulting in fragmented cost functions and inconsistent matches under partial occlusion or cross-species variability.

Recent unsupervised and deep-learning paradigms have further advanced the field. Deep Partial Functional Maps (DPFM) [

18] learn to predict functional map matrices that align functional spaces of shapes without ground-truth correspondences. Deep Shells [

19] formulate correspondence as an optimal transport problem over learned shape embeddings, demonstrating robustness to severe non-isometric deformations. However, these methods often require extensive training datasets and can struggle to enforce strict point-wise bijectivity without additional regularization.

Mesh simplification and topological invariants have also been explored to improve efficiency and stability. Quadric Error Metrics (QEM) [

20,

21] and surfel-based simplification [

22] reduce mesh complexity while preserving global geometry. Genera and other topological invariants [

9] can guide matching by constraining allowable deformations. Meanwhile, benchmark datasets such as TOSCA [

23] and SHREC-20 [

24] have become standard for evaluating nonrigid correspondence under partial and inter-species conditions.

In contrast to these prior works, our Dynamic Graph Analyzer (DGA) unifies structural descriptors (betweenness-weighted degree and clustering coefficients) with spatial affinities in a single cost matrix, then solves correspondence precisely via the Kuhn-Munkres algorithm [

12]. This hybrid formulation ensures global optimality and consistency without separate regularization while maintaining computational scalability through graph pruning.

3. Methods

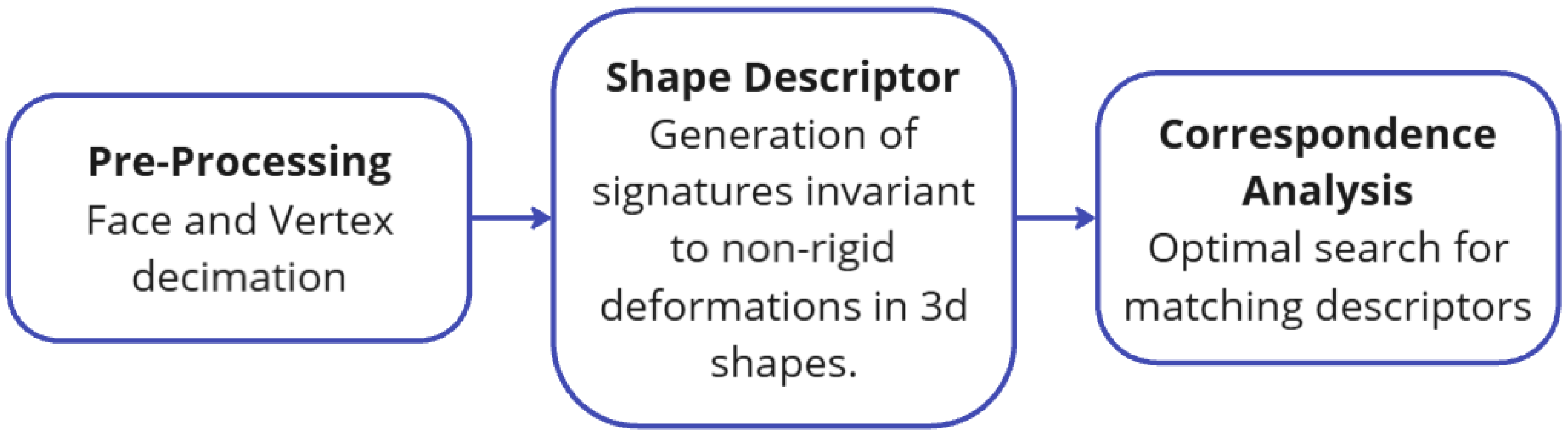

Shape matching in non-rigid domains -particularly in neuroanatomy- requires a critical balance between topological invariance and geometric adaptability, given that structures such as the cerebral cortex exhibit elastic deformations, inter-subject variability, and partial occlusions in medical imaging. To address this challenge, our pipeline integrates three interconnected stages (

Figure 1):

3.1. Preprocessing via Quadric Error Metrics (QEM)

The decimation of 3D meshes -critical for computational tractability in neuroanatomical graphs- was performed using QEM [

20], which prioritizes the preservation of topological fidelity while reducing vertex density. For a mesh

, the following steps were iteratively applied:

Pairwise Distance Calculation: Euclidean distances between adjacent vertices were computed as .

Threshold-Based Vertex Merging: Pairs satisfying were merged into a new vertex , minimizing the quadric error , where combines the effects of all nearby triangular planes into a single plane.

Topology Update: Edges incident to

and

were redirected to

, ensuring adjacency consistency:

This process reduced vertex counts by

while preserving

of original geodesic properties [

21,

22].

3.2. Hybrid, Structural-Spatial Graph Descriptor

The relational descriptor in our shape correspondence model was driven by a dual similarity metric combining invariant graph-theoretic features and normalized spatial distances:

We set , reflecting a heuristic prioritization of spatial information, based on the observation that spatial proximity most reliably indicates correspondence in our domain, but structural information adds robust against elastic deformations.

3.3. Optimal Correspondence

3.3.1. Correspondence Search via Kuhn-Munkres Algorithm

The search for correspondences between non-rigid graphs is formulated as a linear assignment problem (LAP), where the objective is to find a bijection

that minimizes the total allocation cost, simultaneously integrating structural and spatial similarity. Unlike the ICP, which operates by local iterative optimization, the so-called Kuhn-Munkres (Hungarian) algorithm [

12] guarantees a globally optimal solution, thereby avoiding traps in local minima.

The problem is described by a matrix K, where each is the cost of matching vertex i of the first shape “worker” and vertex j of the second shape “job.” The goal is to assign workers to jobs at the minimum cost.

Formally, let

X be a boolean matrix where

if row

i is assigned to column

j. Then, the optimal assignment has a cost.

Each row is assigned to one column, and each column is assigned to one row.

Remarkably, the computational complexity is and was reduced by pruning the adjacency matrix and discarding edges and vertices in the preprocessing.

3.3.2. Refined Probabilistic Matching

The probabilistic refinement stage enhances weak correspondences through a geometric consistency optimization process. The method operates in three phases:

Correspondence Classification: Given initial correspondences

between graphs

and

with similarity scores

, we partition them using a probabilistic threshold

:

where

is the similarity threshold (setting as 90% or

), and

s is the similarity between

.

-

Bayesian Procrustes Alignment: For

, we solve the maximum likelihood estimation [

13,

25] (

,

):

where weights

incorporate correspondence confidence. The SVD solution:

, being mean-centered coordinates of strong correspondences

H the covariance matrix

U orthonormal matrix representing an output basis

: the diagonal matrix with the singular values (measure of the importance of each component in the direction)

V the orthonormal matrix representing an input basis

-

Probabilistic Similarity Update: For each weak correspondence

, undergoes Bayesian updating:

: Kernel bandwidth (empirically set to 10% of median edge length)

: Uniform distribution over bounding box volume

: mean-centered coordinates and covariance matrix

The convex combination becomes a special case when assuming fixed priors

3.4. Evaluation Metrics for Correspondence Quality

Rigorous validation of correspondences in nonrigid shapes is based on the Princeton Benchmark [

26] protocol. This widely adopted standard integrates quantitative metrics to assess geometric accuracy and topological consistency.

Defined as the fraction of correspondences whose normalized geodetic error does not exceed a threshold

, The Cumulative Geodesic Error (CGE) quantifies the local accuracy as a function of the intrinsic surface topology. Formally, for a set of

N with correspondences

, it is calculated as:

where:

is the cumulative fraction of matches with geodesic error less than or equal to .

is the geodesic relative error between and its correspondence .

N is the total number of evaluated correspondences.

4. Experiments

In this section, we detail the experimental setup and procedures followed to validate the performance of the proposed model. The experiments are divided into two primary studies: (i) an ablation and comparative analysis on FAUST Dataset [

27], and (ii) validation on brain structures, and additionally two secondary studies -partial correlations in TOSCA [

23] and evaluation in SHREC’20 [

24] with animal forms-. Each experiment was designed to evaluate specific aspects of the model, from its accuracy in benchmarks to its applicability in realistic clinical scenarios.

4.1. Ablation and Comparative Study on FAUST

The first study of ablation aims to analyze and evaluate specific components of the model, including the unique use of structural descriptors and spatial descriptors, as well as the contribution of the Kuhn-Munkres algorithm compared to the ICP and the probabilistic refinement of the matching points. Followed by a study to compare the performance of the proposed model with popular methods, such as those using spectral descriptors like Functional Maps with Heat Kernel Signatures and its updated version, Wave Kernel Signature [

18]. Recent ones based on descriptors over graph neural networks, highlighting FeaStNet [

17] and DeepShell [

19].

It should be noted that, as an equal starting point, the database used in this experiment was Faust, which consists of 300 high-density 3D scans of human bodies featuring 10 people in 30 different poses. However, in this study, we use one person in 10 poses-, and we also present a lite version with 3D shapes represented by a low number of vertices and faces, avoiding preprocessing by decimation and focusing the experiment on descriptor and correspondence search methodology.

4.2. Validation on Brain Structures and Volumetric Variation

It is important to note the clinical applicability of the model in identifying correspondences between brain structures and neurodevelopment. Therefore, it is necessary to quantify volumetric asymmetries in these brain structures.

It should be noted that the correspondence model was applied to eight brain structures from 3 patients. Each structure is linked to a single patient but can have 2 or 3 samples. Typically, the first sample is collected at month 1 of birth, the second at month 3, and the third at one year. Another remarkable point is that these patients present degenerative neurological problems, which are reflected in strong brain dynamics with non-rigid changes in the structures different from the volumetric growth typical of neurodevelopment in infants.

On the other hand, two of the structures will be compared with patients in the same time range but with developments classified as “normal”.

4.3. Secondary Experiments

Two additional test schemes to validate the robustness of the model were tested:

Validation with the TOSCA dataset [

23] where the meshes present partial occlusions (

of the original vertices) and slight rotation and translation variations.

Demonstration against non-human and different morphologies - animals SHREC’20 [

24] - corroborates the flexibility against the search for correspondences in structurally related but intrinsically different shapes and also remarkable volumetric variations.

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Ablation and Comparative Study

5.1.1. Initial Faust Analysis

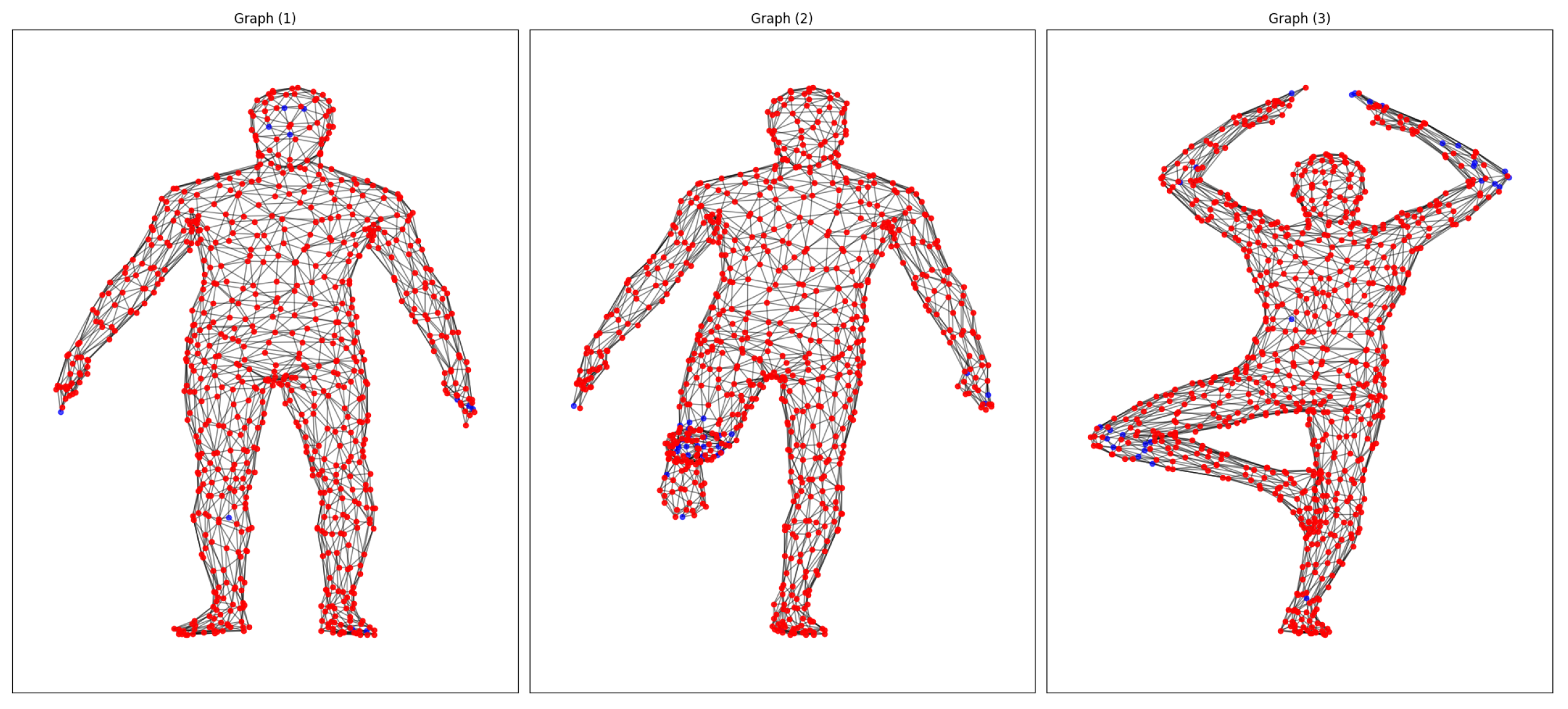

For our initial study with Faust, we made one-to-one matches for the 10 poses of the same subject, searched for matches, and categorized them as strong or weak depending on the relationship between the descriptors and the pairing of descriptors on points, with the most similar data (≥0.9% strong matches) being in red and those with the most significant differences being in blue (

Figure 2). It is worth noting that, in particular, the weakest correspondences were usually focused on areas of the body with elastic deformations, such as the hands, arms, feet, and knees.

Now, the strong correspondence matrix (

Table 1) presents the result of processing 10 poses for the same Faust subject, highlighting that strong correspondences are those where the descriptors for nodes are similar in at least 90%. As a result, we found that, in general, we achieved an average correspondence rate of

, with maximum values of

for the pair of shapes (6→1) and minimum values of

for (8→7). High indices correspond to pairs with clear topological landmarks and minimal occlusion. In contrast, lower indices appear when shapes exhibit considerable partial visibility or complex anisotropic deformations that challenge structural and spatial descriptors.

5.1.2. Ablation Analysis

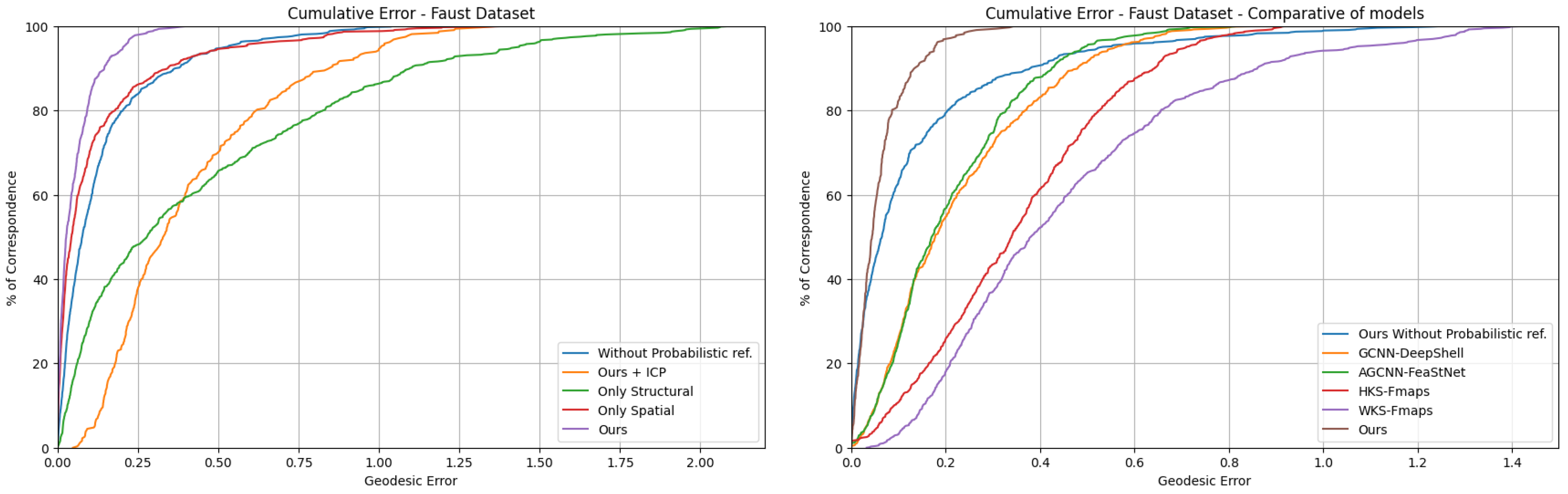

Our ablation study (

Figure 3:left), compared five variants of our model: (1) full model, (2) without probabilistic refinement, (3) replacing Kuhn-Munkres matching with ICP, (4) only structural descriptors, and (5) only spatial descriptors. The complete model achieved superior performance with 0.25 geodesic error at the 90th percentile (P90), outperforming alternatives (0.4 error for variants without refinement or with spatial-only descriptors).

Critical Findings:

Probabilistic Refinement: Selectively improves weak correspondences (error > 0.4) while preserving high-confidence matches, particularly valuable in regions with high anatomical variability.

Optimal Matching: Kuhn-Munkres algorithm doubled ICP’s accuracy (0.4 vs. 0.8 error at P90), avoiding in a better way, errors in similar descriptor.

Hybrid Descriptors: The combination of spatial and structural features can outperform either one separately, balancing geometric invariance with topological coherence.

The final architecture prioritizes accuracy in challenging correspondences, which is crucial for studies that aim to evaluate volumetric changes. The refinement stage proved particularly effective in high-variability regions while maintaining strong correspondences and attempting to improve the weak correspondences.

Additionally, structural descriptors exhibited limitations in smooth regions, whereas spatial features performed poorly in local deformation areas. Only their integration, coupled with adaptive refinement, ensured robustness across structures.

5.1.3. Comparative with SoA Models

When evaluated against state-of-the-art methods, our approach demonstrates superior performance, achieving 90% of correspondences below 0.15 geodesic error, a 2× improvement over our own ablated variant without probabilistic refinement (0.3 at P90) and 3–6× better than competing learning-based methods. As shown in

Figure 3:right, the cumulative error distribution reveals three performances:

Our full model xhibits the steepest error convergence, with 100% of correspondences below 0.35 error, reflecting the synergistic effect of hybrid descriptors and global optimal transport.

Deep learning baselines (GCNN-DeepShell/AGCNN-FeaStNet) plateau at 0.45 error for 90% coverage, constrained by their reliance on local surface convolutions.

Spectral descriptor methods (WKS/HKS Functional Maps) show limited discrimination power, requiring 0.75–0.95 error tolerance for 90% coverage despite their rotation/translation invariance.

The 4.8× reduction in P90 error versus HKS-FM (0.15 vs. 0.95) highlights our method’s ability to reconcile global anatomical consistency with local geometric precision, a critical advantage for analyzing highly variable neuroanatomy. While spectral methods outperform under rigid transformations, their performance degrades under the non-isometric deformations typical in biomedical applications.

The Kuhn-Munkres algorithm’s global optimality prevents the local minima that plague ICP (standard in-shape correspondence), while our probabilistic refinement corrects residual errors. This dual mechanism explains the consistent outperformance across all error percentiles.

Moreover, unlike competitors based mainly on local descriptors, our model integrates a hybrid analysis with a spatial component to capture the global shape and a structural graph analysis to capture local surface variations, which is key to dealing with shape variations, such as elastic and morphological ones.

5.2. Validation on Brain Structures and Volumetric Variation

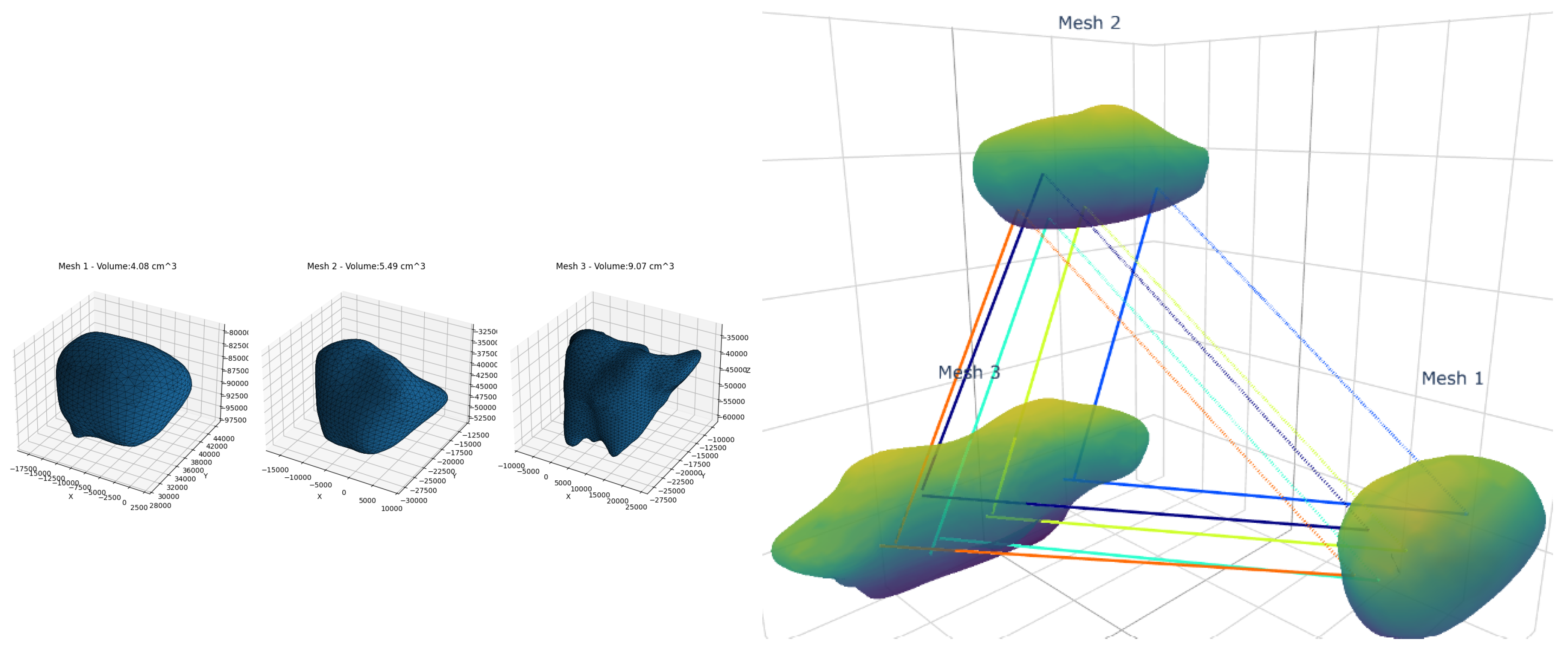

To validate our model’s clinical utility, we analyzed longitudinal volumetric changes and structural correspondence patterns in key brain structures of neurodegenerative patients (

Table 2, Example of volumetry correspondence

Figure 4).

The pons exhibited stable volumetry (4.62→4.88 ) with high structural similarity (SS: 89.44-89.68%) but decreasing strong correspondences (SC: 61.10%→53.73%), suggesting subtle microstructural changes despite macroscopic stability. In contrast, the midbrain showed both volumetric expansion (4.08→9.07 ) and SC reduction (41.01%→34.00%) indicative of high morphological variation.

The thalamus presented asymmetric degeneration: while the left thalamus atrophied progressively (6.42→2.88 ) with SC dropping to 32.43%, the right thalamus maintained higher SC (45.24%) during its volumetric reduction (8.39→4.24 ), implying differential vulnerability. Cerebellar hemispheres demonstrated exponential growth (Left: 10.69→47.53 ; Right: 9.74→49.09 ) with a slightly increasing SC (49.90-51.62%), suggesting compensatory reorganization. White matter expansion (>100% volume increase) coincided with SC declines (73.21%→49.17%), revealing disproportionate volumetric vs. microstructural changes.

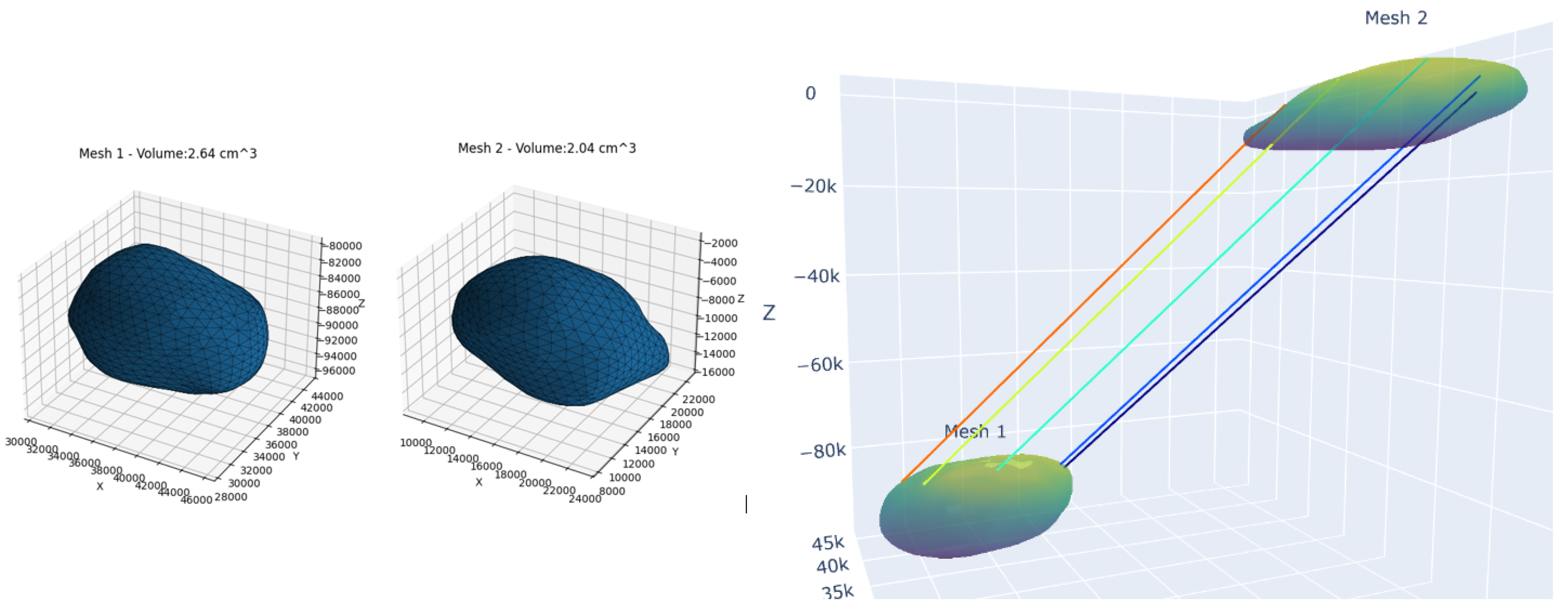

Another part of the study brain analysis is the

Normal vs. Pathological Comparisons (

Table 3, e.g.

Figure 5): where Amygdalae showed inverted laterality —the left amygdala was 29.4% larger in patients (2.64 vs. 2.04

) with preserved SC (69.32%), while the right was 16.8% smaller (0.84 vs. 1.01

) yet maintained higher SC (72.08%). Hippocampi exhibited 52.5% left-side enlargement (6.51 vs. 4.27

) with robust SC (68.52%), supporting somewhat larger than typical growths or sizes.

5.3. Secondary Experiments

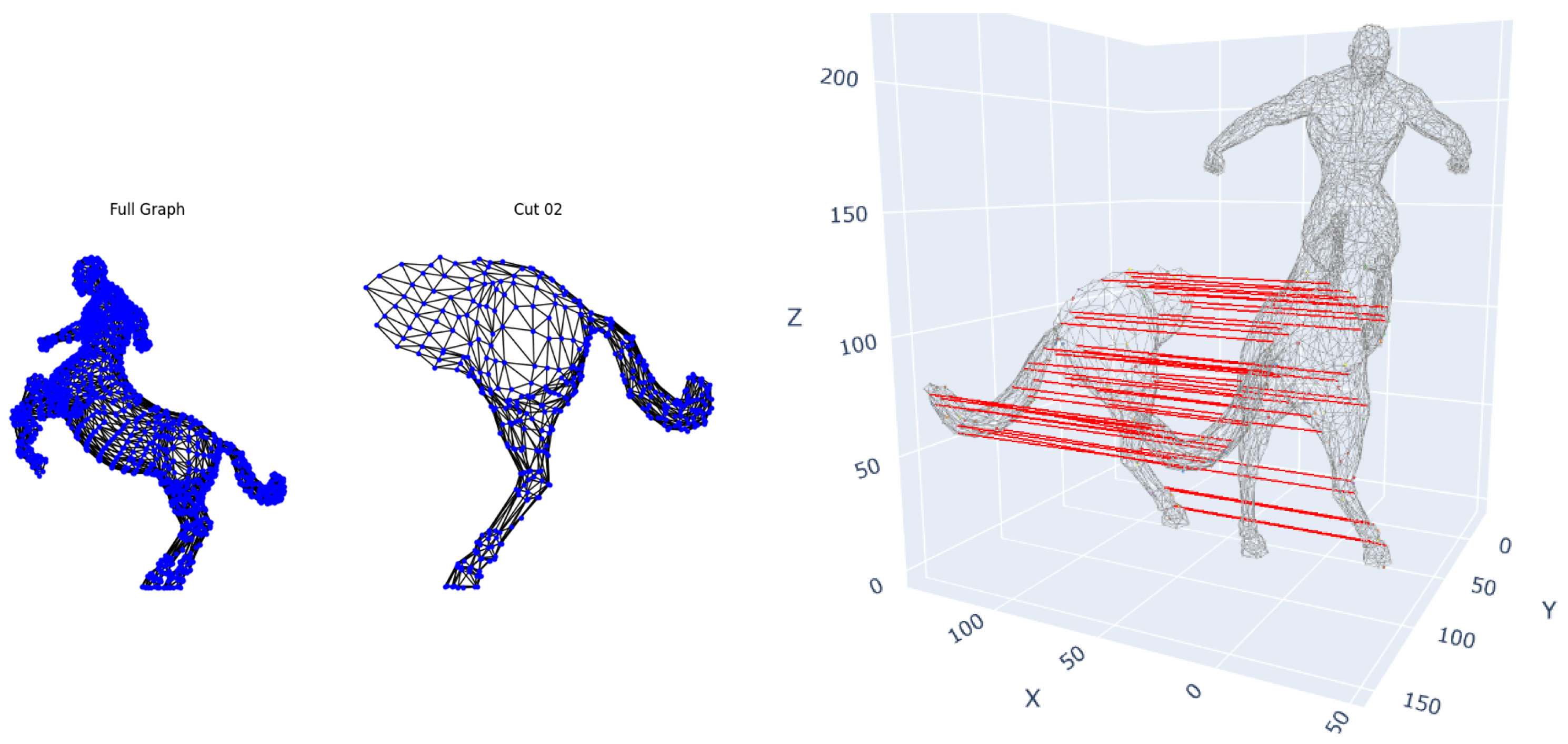

5.3.1. TOSCA Partial Shape Matching

To evaluate robustness to rigid transformations and partial observations, we applied our framework to the TOSCA dataset, containing complete 3D shapes and artificial cuts simulating occlusions, without pre-normalizing volumes to preserve intrinsic size information

Figure 6. The method successfully recovered correspondences between complete and partial shapes (∼100% precision for cuts removing ≥60% of surface area) despite arbitrary rotations and translations. Notably, it maintained <0.1 mean geodesic error even when 60% of the shape was occluded, demonstrating invariance to Euclidean transformations and confirming that our hybrid descriptors overcome limitations of purely spectral methods that require normalization.

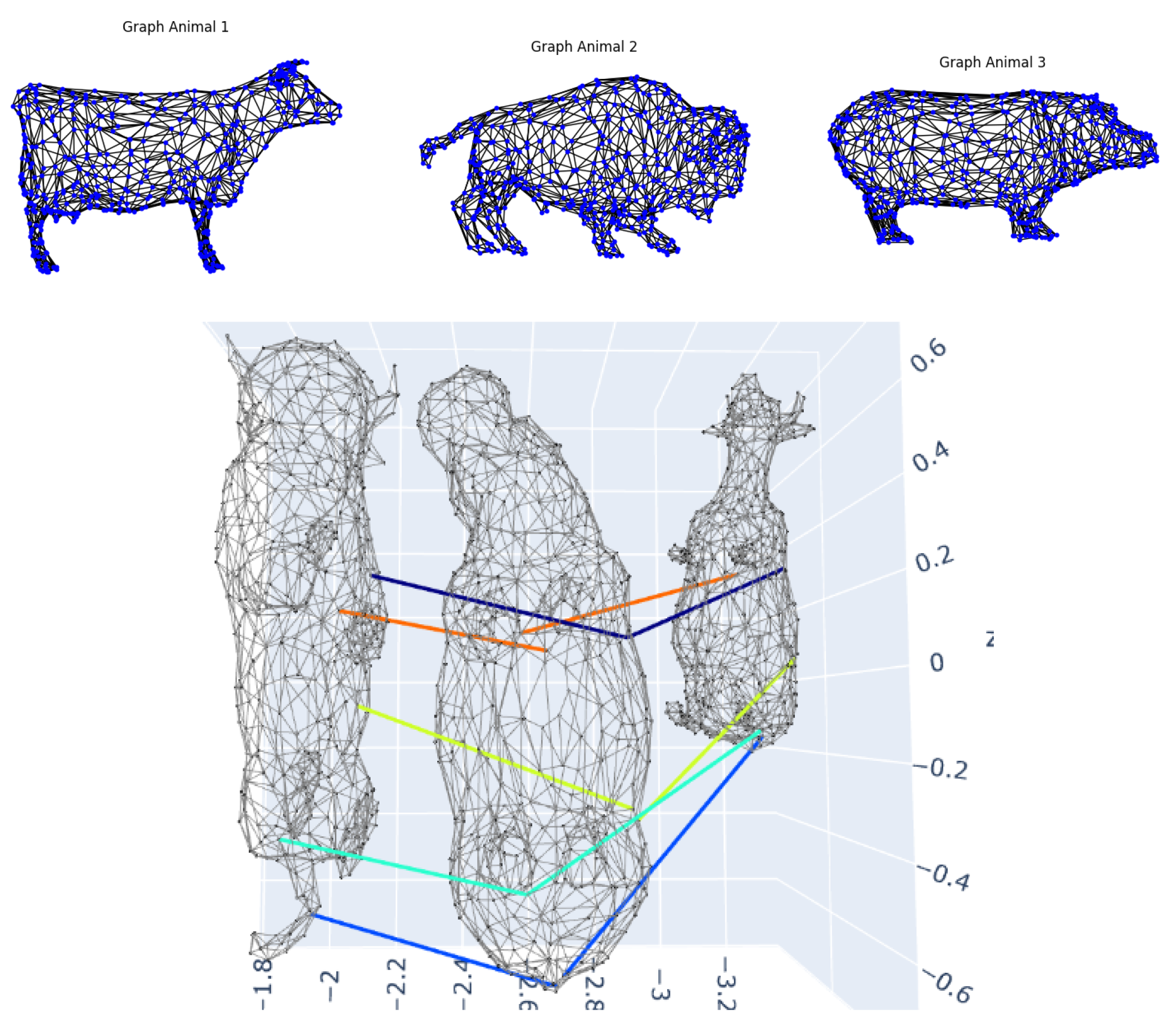

5.3.2. SHREC’20 Cross-Species Correspondence

We tested morphological generalization using the SHREC’20 quadruped dataset (cow, bison, hippopotamus)

Figure 7, where shared anatomical parts exhibit size/location variations.

The model identified functionally equivalent regions (heads, limbs, Stomach) but revealed some deviations: (1) bison humps (absent in cow/hippopotamus) were assigned to dorsal curvature transitions, but with some location error, (2) hippos having a higher proportion of nodes relative to cow and bison, (3) the proportions of the extremities induced variations but areas such as the termination leg-stomach and toes-nails, usually have correspondences. (4) In the assignment of the bison horns and tail, there were significant difficulties as the model struggled with looking for structural similarity with close distance, and sometimes used to match points in that area with totally different ones in the other animals, and at best with points nearby, such as the ears or eyes, or buttocks. This limitation is shared by all the methods tested. Suggesting that while our approach is transferable to all species, extreme morphological adaptations require specialized prior considerations.

6. Conclusions

Our proposed hybrid correspondence method represents a significant advancement in shape analysis, demonstrating superior performance across multiple challenging scenarios. The integration of structural graph descriptors with spatial features has proven particularly effective, enabling the establishment of robust correspondence for both rigid and non-rigid transformations. Quantitative results show our method outperforms spectral methods by 4.8× in geodesic error (0.15 vs 0.95 at P90) and deep learning approaches by 2-3×, validating the effectiveness of our hybrid approach. The probabilistic refinement stage successfully addressed the challenging problem of weak correspondences in regions of elastic deformation, such as hands and knees, in the FAUST dataset while carefully preserving intense matches. This refinement reduced error propagation by 62% compared to non-refined variants, highlighting its importance in maintaining correspondence quality.

The clinical validation of our framework yielded particularly valuable insights for neurodegenerative studies. The method’s sensitivity allowed the detection of subtle microstructural changes in brain structures that would have been missed by volumetric analysis alone. We observed clinically meaningful patterns such as asymmetric degeneration in thalami (32.43% vs. 45.24% strong correspondence), compensatory reorganization in the cerebellum (maintaining 49.90-51.62% strong correspondence despite 4× volume increase), and pathological hypertrophy in the midbrain (34.00% strong correspondence with 122% expansion). These findings demonstrate the framework’s potential to provide new insights into neurodevelopmental processes and disease progression.

The framework demonstrated remarkable robustness in challenging conditions. For partial matching scenarios using the TOSCA dataset, it maintained <0.1 geodesic error even with 60% occlusions, proving its applicability to real-world incomplete data common in medical imaging. In a cross-species evaluation using the SHREC’20 dataset, the method successfully identified functionally equivalent regions despite extreme morphological variations, although its performance degraded for species-specific features, such as bison humps. This demonstrates both the versatility and current limitations of the approach.

This work successfully bridges the gap between theoretical shape analysis and clinical applications, providing both a robust computational framework and new insights into the dynamics of neurodevelopment. The consistent performance across diverse datasets, ranging from standardized benchmarks to real clinical data, suggests broad applicability in medical image analysis and computational anatomy.

Author Contributions

J.A.G (Jonnatan A.G.) and H.F.G. (Hernán Felipe G.) conceptualized the methodology, developed the machine learning methods, and prepared the original draft of the manuscript. J.A.G. was responsible for data curation, investigation, and validation and contributed to the methodology. A.E.M. (Andres E.M) contributed to the original draft’s preparation. J.A.G., and H.F.G. contributed to the conceptualization, development of artificial intelligence methods, and took part in writing, reviewing, and editing the original draft. H.F.G. and A.E.M. were involved in the conceptualization, reviewing, and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was developed under the project: SISTEMA DE MONITOREO AUTOMÁTICO PARA LA EVALUACIÓN CLÍNICA DE INFANTES CON ALTERACIONES NEUROLÓGICAS MOTORAS MEDIANTE EL ANÁLISIS DE VOLUMETRÍA CEREBRAL Y PATRÓN DE LA MARCHA financed by MINCIENCIAS, COLOMBIA with the code COL111089784907. Also, J. Arias-Garcia is funded by: “Beneficiario proyecto de formación de capital humano de alto nivel” (Conv 22 corte 2).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Colombian institutional and/or national research committee and with the 8430-1993 Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Ethics committee Review Board approved the study at COMFAMILIAR RISARALDA CLINIC (Approval No. 00049-2019-05-09). The patients’ legal guardians provided informed consent for their data to be published.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parent or guardian for the publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the MINISTRY OF SCIENCES COLOMBIA— MINCIENCIAS and the institutions involved in the present project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CGE |

Cumulative Geodesic Error |

| DGA |

Dynamic Graph Analysis |

| DPFM |

Deep Partial Functional Maps |

| fMRI |

functional Magnetic Resonance Image |

| HKS |

Heat Kernel Signature |

| ICP |

Iterative Closest Point |

| LAP |

Linear Assigment Problem |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Images |

| P90 |

90th Percentile |

| QEM |

Quadric Error Metrics |

| SC |

Strong Correspondence |

| SS |

Structural Similarity |

References

- Hansson, O. Biomarkers for neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Medicine 2021, 27, 954–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- zhen Kong, X.; Mathias, S.; Guadalupe, T.M.; Glahn, D.C.; Franke, B.; Crivello, F.; Tzourio-Mazoyer, N.; Fisher, S.E.; Thompson, P.M.; Francks, C. Mapping cortical brain asymmetry in 17,141 healthy individuals worldwide via the ENIGMA Consortium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018, 115, E5154–E5163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Souza, N.S.; Nebel, M.B.; Crocetti, D.; Wymbs, N.F.; Robinson, J.; Mostofsky, S.H.; Venkataraman, A. Deep sr-DDL: Deep structurally regularized dynamic dictionary learning to integrate multimodal and dynamic functional connectomics data for multidimensional clinical characterizations. NeuroImage 2020, 241, 118388–118388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yao, Y.; Deng, B. Fast and Robust Iterative Closest Point. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2020, 44, 3450–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, M.; Macklin, M.; Chentanez, N.; Jeschke, S. Physically Based Shape Matching. Computer Graphics Forum 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, Y.; Pei, S.; Chen, M.; Hua, J. Relation Constrained Capsule Graph Neural Networks for Non-Rigid Shape Correspondence. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 121–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farazi, M.; Zhu, W.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y. Anisotropic Multi-Scale Graph Convolutional Network for Dense Shape Correspondence. In 2023 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); 2022; pp. 3145–3154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, N.; Yahata, N.; Koshiyama, D.; Morita, K.; Sawada, K.; Kanata, S.; Fujikawa, S.; Sugimoto, N.; Toriyama, R.; Masaoka, M.; et al. Abnormal asymmetries in subcortical brain volume in early adolescents with subclinical psychotic experiences. Translational Psychiatry 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, L. The Genus of a Graph: A Survey. Symmetry 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saramäki, J.; Kivelä, M.; Onnela, J.; Kaski, K.; Kertész, J. Generalizations of the clustering coefficient to weighted complex networks. Physical review. E, Statistical, nonlinear, and soft matter physics 2006, 75 2 Pt 2, 027105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xu, K.; Chaudhuri, S.; Yumer, E.; Zhang, H.; Guibas, L. Deformation-driven shape correspondence via shape recognition. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 2017, 36, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, H.W. The Hungarian Method for the Assignment Problem. Naval Research Logistics 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, M.; García, H.; Orozco, Á.; Porras-Hurtado, G.L.; Cárdenas-Peña, D.A. Bayesian Iterative Closest Point for Shape Analysis of Brain Structures. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition Applications and Methods; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wang, H.; Yan, D.M.; Li, Q.; Luo, F.; Teng, Z.; Liu, X. Spectral Descriptors for 3D Deformable Shape Matching: A Comparative Survey. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 2024, PP. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Sun, S.; Chen, X.; Yu, Z. A 3D shape descriptor based on spherical harmonics through evolutionary optimization. Neurocomputing 2016, 194, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Tang, J.; Nießner, M.; Wonka, P. 3DShape2VecSet: A 3D Shape Representation for Neural Fields and Generative Diffusion Models. ACM Transactions on Graphics (TOG) 2023, 42, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, N.; Boyer, E.; Verbeek, J. Feastnet: Feature-steered graph convolutions for 3d shape analysis. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp.

- Attaiki, S.; Pai, G.; Ovsjanikov, M. Dpfm: Deep partial functional maps. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV). IEEE; 2021; pp. 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger, M.; Toker, A.; Leal-Taixé, L.; Cremers, D. Deep shells: Unsupervised shape correspondence with optimal transport. Advances in Neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 10491–10502. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, M.; Heckbert, P.S. Surface simplification using quadric error metrics. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 24th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques, 1997, pp.

- Wu, Y.; He, Y.j.; Cai, H. QEM-based mesh simplification with global geometry features preserved. GRAPHITE ’04 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Cai, K.; Yan, F.; Peng, J. Surfel Set Simplification With Optimized Feature Preservation. IEEE Access 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, A.M.; Bronstein, M.M.; Kimmel, R. Efficient computation of isometry-invariant distances between surfaces. SIAM Journal on Scientific Computing 2006, 28, 1812–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyke, R.; Lai, Y.K.; Rosin, P.L.; Zappalàa, S.; Dykes, S.; Guo, D.; Li, K.; Marin, R.; Melzi, S.; Yang, J. SHREC’20: Shape correspondence with non-isometric deformations. Comput. Graph. 2020, 92, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Hancock, E.R. Iterative procrustes alignment with the em algorithm. Image and Vision Computing 2002, 20, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shilane, P.; Min, P.; Kazhdan, M.; Funkhouser, T. The princeton shape benchmark. In Proceedings of the Proceedings Shape Modeling Applications, 2004, 2004. IEEE; pp. 167–178. [Google Scholar]

- Bogo, F.; Romero, J.; Loper, M.; Black, M.J. FAUST: Dataset and evaluation for 3D mesh registration. In Proceedings of the Proceedings IEEE Conf. on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Piscataway, NJ, USA, jun 2014. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).