| Policy Opinion Paper with Framework |

| Executive Summary |

2 |

| Introduction |

3 |

| Methodology |

4 |

| Study Design and Approach |

4 |

| Data Sources and Document Review |

4 |

| Comparative Model Adaptation |

4 |

| Framework Development Process |

4 |

| Ethical Considerations |

5 |

| Public Health at Risk: Impacts of Waste Mismanagement in Kampala |

5 |

| Systemic Failures in Kampala’s Waste Management |

9 |

| Kigali’s Waste Management Model: Successes and Limitations |

10 |

| Comparative Insights: Tailoring Lessons from Kigali to Kampala |

12 |

| Limitations in Kigali’s Model: What Kampala Must Avoid |

13 |

| The KIWR Framework: Building on Kigali, Advancing Further |

13 |

| Strategic Takeaways for Kampala |

14 |

| Implementation Roadmap and Policy Recommendations |

14 |

| Phase 1: Foundation Laying |

14 |

| Phase 2: System Expansion in the 2nd year |

14 |

| Phase 3: Optimization and Resilience (the following year) |

15 |

| Policy Recommendations |

15 |

| 1. Anchor Waste Management in National Health Strategy |

15 |

| 2. Reform Waste Regulation and Enforcement |

15 |

| 3. Institutionalize Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) with Equity Goals |

15 |

| 4. Fund Decentralized Composting and Waste-to-Energy Infrastructure |

15 |

| 5. Establish a Kampala Waste Observatory |

15 |

| Expected Outcomes by the 5th year |

15 |

| Risks and Mitigation Strategies |

16 |

| Conclusion: From Collapse to Resilience |

16 |

| Glossary of Key Terms |

17 |

| 1. Circular Economy |

17 |

| 2. Public-Private Partnership (PPP) |

17 |

| 3. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) |

17 |

| 4. Composting |

17 |

| 5. Waste-to-Energy (WTE) |

17 |

| 7. Sanitation Infrastructure |

17 |

| 8. Waste Segregation |

17 |

| 10. Methane Capture |

17 |

| 11. IoT-Enabled Waste Monitoring |

18 |

| 12. Health Risk Surveillance |

18 |

| 13. Informal Settlements |

18 |

| 15. Environmental Health |

18 |

Executive Summary

Kampala, Uganda’s capital, faces an escalating solid waste management crisis driven by rapid urbanization, inadequate infrastructure, and weak regulatory enforcement. With an estimated 2,500 tonnes of waste generated daily, only 40–60% is formally collected, leaving large volumes uncollected, illegally dumped, or burned particularly in informal settlements. This has resulted in widespread environmental degradation and rising public health risks, including waterborne diseases, respiratory illnesses, and increased exposure to toxic waste, especially among vulnerable urban populations.

Despite existing regulations such as the National Environment (Waste Management) Regulations, 2020, enforcement remains inconsistent, and institutional coordination is weak. The 2024 Kiteezi landfill collapse, which claimed dozens of lives, exemplifies the consequences of infrastructure failure and policy inertia. At the same time, current strategies in Kampala do not adequately incorporate waste minimization, public health protections, or circular economy principles, which are essential for long-term resilience.

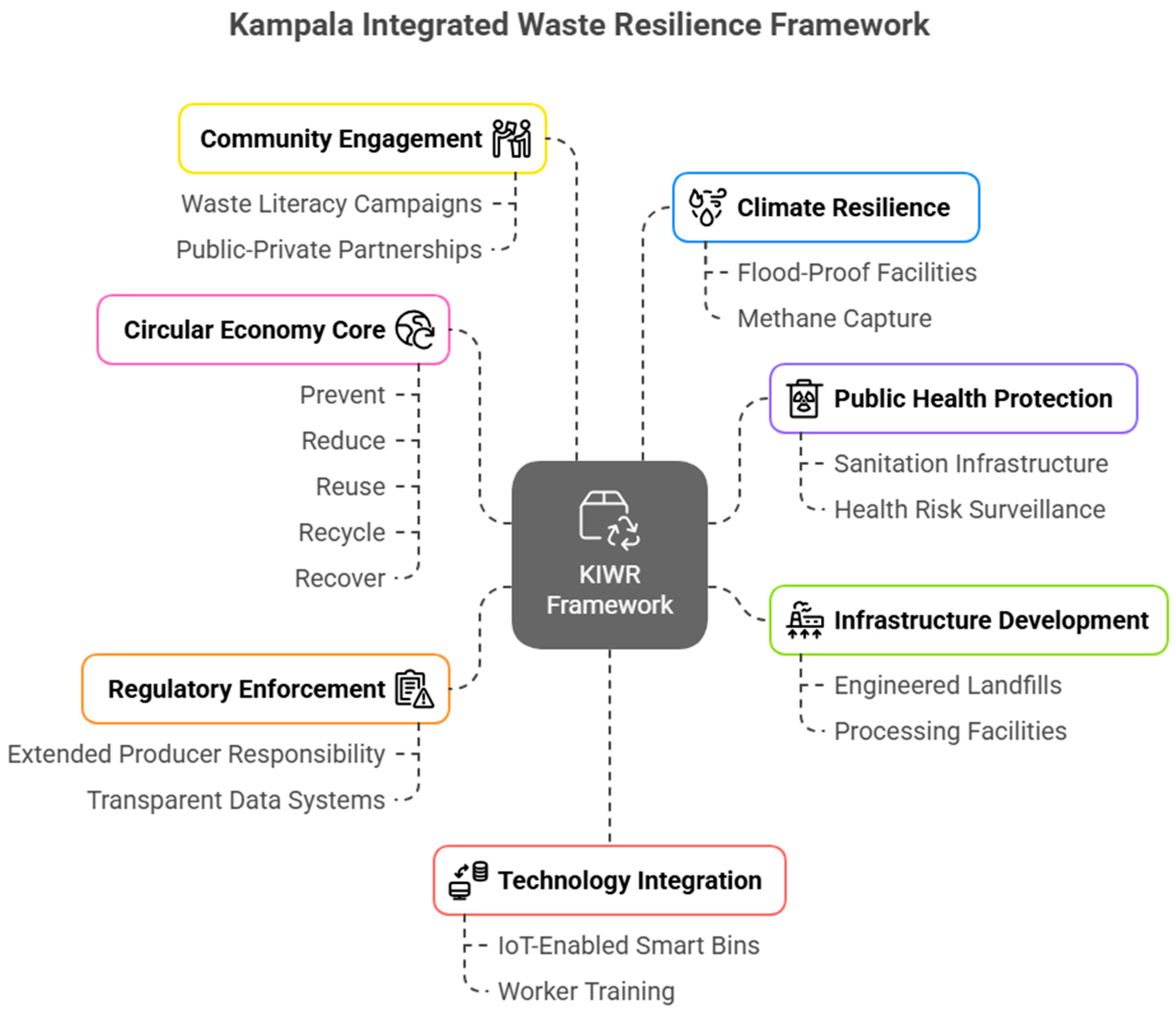

In response, this paper proposes the Kampala Integrated Waste Resilience (KIWR) Framework a comprehensive, health-centered model grounded in six pillars:

Circular Economy Core (Prevent, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Recover)

Public Health Protection

Infrastructure Development

Regulatory Enforcement

Community Engagement

Climate Resilience and Technology Integration

Drawing lessons from Kigali’s waste success while addressing its limitations, the KIWR Framework emphasizes decentralization, waste-to-resource innovation, flood-resilient infrastructure, and inclusive public-private partnerships (PPPs). It also introduces modern solutions such as IoT-based waste monitoring, methane capture, and community-led composting, aiming to increase collection coverage to 80% and reduce landfill dependency.

This framework offers a transformative roadmap for Kampala’s transition toward a cleaner, healthier, and more sustainable urban future. It aligns with Uganda’s national waste strategy and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and serves as a replicable model for other rapidly urbanizing African cities grappling with similar challenges.

Introduction

Kampala, Uganda’s capital, has undergone rapid urbanization, with its population surpassing 1.5 million and daily commuter influxes amplifying urban pressures (Local Governments (Kampala City Council) (Solid Waste Management) Ordinance, 2000). This growth has intensified the city’s waste management crisis, with approximately 2,500 tonnes of solid waste generated daily, of which only 40–60% is collected (NEMA, 2019). The catastrophic collapse of the Kiteezi landfill on August 10, 2024, which killed over 23 people and displaced around 1,000, underscores the dire consequences of inadequate waste management infrastructure (Parliament of Uganda, 2024). Operating since 1997, Kiteezi exceeded its capacity by 2005, yet continued to receive waste, forming unstable slopes that collapsed under heavy rainfall, highlighting systemic failures in regulation, infrastructure, and planning (Aryampa et al., 2021).

The Local Governments (Kampala City Council) (Solid Waste Management) Ordinance (2000) prohibits improper waste disposal in public spaces, which contributes to environmental hazards like water contamination and urban flooding (Para. 5). Uncollected waste, often dumped in drainage systems or burned openly, exacerbates air and water pollution, posing significant public health risks, including respiratory diseases and waterborne illnesses (CISL, 2024). The Kiteezi disaster exposed vulnerabilities such as insufficient funding, weak regulatory enforcement, and lack of public awareness, compounded by the absence of modern waste processing facilities like recycling or incineration plants (Parliament of Uganda, 2024). The government’s response includes plans to decommission Kiteezi, establish a 200-meter buffer zone, and explore alternative disposal sites in Menvu, Nansana, and Busumamura, alongside adopting sustainable practices like incineration and recycling (Parliament of Uganda, 2024).

This paper advocates for a circular economy approach to address Kampala’s waste crisis, emphasizing reduction, reuse, recycling, and reclamation to mitigate public health and environmental impacts. By aligning with the ordinance’s provisions for recycling and reclamation (Local Governments (Kampala City Council) (Solid Waste Management) Ordinance, 2000, Paras. 33, 38), and drawing on innovative models like waste-to-energy systems, Kampala can transform waste into a resource, reduce landfill dependency, and foster sustainable urban development.

Methodology

Study Design and Approach

This paper employed a policy research and conceptual framework development approach grounded in integrated environmental health theory, urban waste governance analysis, and comparative systems thinking. The design was qualitative, analytical, and exploratory, with the objective of developing a contextualized, evidence-based model termed the Kampala Integrated Waste Resilience (KIWR) Framework to address the persistent public health and waste management challenges in Kampala, Uganda.

Data Sources and Document Review

The study utilized secondary data from a diverse and validated set of sources, including:

Government regulatory documents, such as Uganda’s National Environment (Waste Management) Regulations, 2020; Policy briefs, including Reducing the Waste Burden in Ugandan Cities (Paetow & Womer, 2024);

Sectoral analyses, such as the GIZ Sector Brief on Waste and Recycling in Uganda (2023);

Peer-reviewed scientific literature, with emphasis on: Environmental sanitation (Fuhrimann et al., 2016), Healthcare and e-waste practices (Wafula et al., 2019; Nuwematsiko et al., 2021), Community-level health risk perspectives (Ssemugabo et al., 2020), Food waste reuse (Ssepuuya et al., 2023);

Comparative insights from Rwanda’s waste management model, especially Kigali’s enforcement and PPP system, extracted from publicly available governance and urban sanitation performance reports.

These documents were critically reviewed using content analysis, with thematic coding focused on: Waste governance gaps, Public health consequences, Infrastructure challenges, and Best practices from comparator cities. This document analysis informed the strategic layering of the proposed framework and ensured alignment with both local realities and regional best practices.

Comparative Model Adaptation

A comparative case methodology was used to assess and adapt elements of Rwanda’s Kigali waste model. Specific focus was placed on collection coverage rates, public-private partnership enforcement, licensing structures, and civic engagement strategies. Kigali’s achievements such as 95% waste collection coverage and fine-based compliance systems were contrasted with Kampala’s performance data (40–60% collection rates, overreliance on Kiteezi landfill, minimal community education), as captured in the reviewed reports.

This cross-case analysis enabled the identification of both transferable strategies and limitations requiring contextual adjustment. For example, whereas Kigali demonstrated strong centralized enforcement, the KIWR Framework emphasizes decentralization and community resilience to address Kampala’s informality, flooding, and high organic waste composition.

Framework Development Process

The KIWR Framework was developed through a stepwise synthesis of findings into six operational pillars each mapped to critical gaps observed across the reviewed data:

The Circular Economy Core (Prevent, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, Recover) was placed at the center to guide each pillar’s actions and feedback loops. This central concept was informed by both global environmental health theory and Kampala’s specific waste profile dominated by organic waste and poor source segregation.

Framework validation was conducted through internal consistency testing, where each pillar’s actions were aligned with real-world gaps and challenges. For example, the proposal for flood-resilient waste infrastructure was derived directly from literature highlighting Kampala’s vulnerability to waste-related flooding and leachate contamination (GIZ, 2023; Fuhrimann et al., 2016).

Ethical Considerations

As the study relied exclusively on publicly available documents and published data, no human participants were involved, and ethical approval was not required. However, all sources have been appropriately acknowledged, and data usage complies with open-access licensing and academic standards for attribution.

Public Health at Risk: Impacts of Waste Mismanagement in Kampala

Kampala’s growing waste crisis is not only an environmental and infrastructural failure, it is a severe and ongoing public health emergency, especially in low-income and informal settlements. As the city produces an estimated 2,000 to 2,500 tons of waste per day, only 60% is collected, leaving the rest to accumulate in open spaces, drainage systems, and informal dumpsites (GIZ, 2023). This unmanaged waste directly contributes to a rising burden of infectious, respiratory, parasitic, and psychosocial illnesses, particularly in slum communities like Bwaise, Kisenyi, and Katwe.

In areas with limited or no waste collection, burning garbage is a common disposal method. This releases toxic pollutants including dioxins, furans, and fine particulate matter (PM2.5), which cause asthma, chronic bronchitis, cardiovascular complications, and neurological disorders. Vulnerable groups such as children, pregnant women, and the elderly are at elevated risk (Paetow & Womer, 2024; Ssemugabo et al., 2020). The cumulative exposure to smoke contributes to long-term respiratory illness and reduced lung function, often unnoticed in public health reporting.

Uncollected plastic and organic waste often clog drainage systems, especially during the rainy season, resulting in widespread flooding. Floodwaters in Kampala mix with human waste, garbage, and leachates, creating vectors for cholera, typhoid, dysentery, and intestinal parasitic infections (Okaali et al., 2022; Fuhrimann et al., 2016). Inhabitants of informal settlements suffer recurrent disease outbreaks due to exposure to contaminated floodwater, poor sanitation, and a lack of safe drinking water.

Poor communities bear the heaviest health burden from waste mismanagement. In areas where municipal collection is absent, open dumping is prevalent, exposing residents to decomposing organic matter, animal waste, medical refuse, and e-waste (GIZ, 2023; Nicholas, 2017). Children playing in or near these sites are at risk of skin infections, parasitic diseases, injuries from sharp objects, and long-term toxic exposure. The August 2024 trash landslide at Kiteezi landfill, which killed over 30 residents, exemplifies the human cost of ignoring urban waste hazards (Paetow & Womer, 2024).

Leachates from overused landfills like Kiteezi and informal dumpsites introduce heavy metals, pathogens, and industrial toxins into the soil and groundwater. Residents relying on shallow wells and boreholes for water face exposure to chemicals linked to kidney and liver disease, reproductive problems, developmental issues in children, and cancer (Nicholas, 2017; GIZ, 2023). The absence of regular water testing or monitoring amplifies these hidden risks.

With only 1% of Kampala’s population connected to a central sewer system, most residents depend on on-site sanitation systems, which are often poorly constructed or overflowing (GIZ, 2023). During floods, fecal sludge mixes with solid waste, creating a dangerous environmental health threat. Urban farmers in wetlands and around drainage areas face especially high risks of intestinal parasitic infections (Fuhrimann et al., 2016).

In addition to domestic waste, Kampala struggles with healthcare waste from clinics and e-waste from electronic devices. A 2019 study found that many health workers lacked training in healthcare waste disposal, resulting in open dumping or improper incineration (Wafula et al., 2019). E-waste, which contains lead, mercury, cadmium, and brominated flame retardants, is frequently dismantled in unsafe conditions, exposing informal workers to chronic toxicity (Nuwematsiko et al., 2021).

While over 90% of households recognize food waste as a usable resource, the lack of structured composting or animal feed recycling results in unhygienic disposal, which attracts vermin and contaminates water supplies (Ssepuuya et al., 2023). Poor handling of decaying organic waste, especially near food markets and informal kitchens, contributes to bacterial infections, fly-borne disease transmission, and poor urban hygiene.

Living near piles of decomposing garbage, toxic smoke, and sewage-contaminated floodwater affects not just physical health but also mental well-being. Studies among Kampala’s youth have revealed that garbage-related odors, environmental filth, and persistent disease threats increase feelings of anxiety, depression, and helplessness (Ssemugabo et al., 2020). These emotional burdens are particularly heavy for women, children, and slum-dwelling families who are unable to relocate or improve their environment.

In summary, the cumulative health effects of poor waste management in Kampala are far-reaching, disproportionately affecting the urban poor, informal workers, women, and children. From cholera to cancer, and from anxiety to asthma, the current model of waste handling fails to safeguard the public’s well-being. Despite community-led coping efforts and some private sector innovations, the scale and severity of the crisis demand a citywide transformation anchored in public health protection and circular economy principles.

In the next section, we explore the limitations of existing waste strategies and why Kampala must adopt a health-sensitive, inclusive, and sustainable waste management model.

Current Waste Strategies and Gaps in Kampala

The current waste management strategies in Kampala, Uganda, operate under a growingly robust but still incomplete legal and institutional framework. The Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) serves as the lead local government body responsible for municipal waste management, guided by both the amended Public Health Act (Cap. 281) and the National Environment (Waste Management) Regulations, 2020. The Public Health (Amendment) Act, 2023, now clarifies the mandate of both KCCA and local governments by explicitly assigning them responsibility for safeguarding public health (Public Health Amendment Act, 2023, s.5). Section 5A further empowers medical officers to take action to prevent and control disease outbreaks, which includes conditions arising from poor waste handling. Although this reform modernizes the institutional language and repeals outdated provisions: such as Sections 76–85 dealing with sewers it remains largely silent on emerging urban waste streams, waste segregation enforcement, and climate-resilient infrastructure planning.

KCCA has recently taken steps to address these operational and infrastructural gaps through its 2024/2025 waste management agenda. Unveiled by Executive Director Dorothy Kisaka in July 2024, the KCCA Smart City plan aims to improve garbage collection, expand public access to disposal points, and enhance recycling rates (KCCA, 2024). Key milestones include the installation of 20 new garbage storage units and 400 street litter bins, a fleet of 40 garbage trucks with five additional tractors and cesspool trucks, and the planned decommissioning of the Kiteezi landfill. The latter is aligned with a phased shift toward the Dundu landfill, which is expected to include a waste-to-energy component. This transition is not only strategic but legally necessary: under the 2020 Waste Management Regulations, all landfills must be engineered and comply with stringent water protection and leachate treatment measures (Reg. 74).

The Guidelines for the Management of Landfills in Uganda (2020) set out rigorous requirements for site selection, design, and engineering of new landfills, emphasizing the need for proper location, liner systems, and leachate management to protect soil and water resources (Chapters 3–6)1. For example, all engineered landfills must include multi-layer liner systems, leachate collection and storage, and groundwater monitoring to prevent contamination. The planned Dundu landfill must therefore comply with these technical standards, which go beyond general regulatory requirements and provide detailed operational benchmarks.

The Guidelines specify that leachate drainage, collection, and removal systems are essential for all landfill operations, with detailed criteria for storage and recirculation (Chapter 6)1. Additionally, landfill gas management systems are required to capture, monitor, and, where feasible, utilize methane and other gases generated by decomposing waste (Chapter 7)1. These provisions are critical for both environmental protection and public health, supporting the legal requirements under the 2020 Waste Management Regulations.

Nevertheless, Kampala’s waste legislation and practical operations still face several structural deficiencies. The 2020 Regulations now legally enforce the waste management hierarchy, requiring all actors from households to municipalities to prioritize waste prevention, reduction, reuse, recycling, recovery, and only as a last resort, disposal (Reg. 7). While KCCA's new strategy includes a target to recycle 5% of garbage (38,325 tons), this remains a modest figure in light of the legal requirement to minimize waste generation and maximize material recovery. Further integration of Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), as outlined in Regulations 35–39, would help shift more accountability to manufacturers and importers for take-back and recycling schemes, particularly for plastic and electronic products.

A critical area of neglect continues to be electronic waste and healthcare waste management. The 2020 Regulations specifically prohibit the disposal of electronic and infectious healthcare waste in landfills (Reg. 70) and mandate that local governments establish e-waste collection centers and work with manufacturers to manage this stream safely (Reg. 40–44). Yet Kampala lacks visible infrastructure or policy to meet these obligations. The absence of e-waste collection hubs or incentives at the community level points to a significant compliance gap, which undermines environmental safety and public health.

KCCA’s record-keeping, public reporting, and environmental monitoring also need improvement. Regulation 73 requires waste handlers to maintain a detailed waste database tracking types, quantities, sources, and treatment methods of landfilled waste which must be retained for at least 10 years and made available to NEMA on request. There is little evidence that this requirement is being consistently implemented or that KCCA publishes these data for public or institutional scrutiny.

The Guidelines for the Management of Landfills in Uganda (2020) elaborate on environmental monitoring protocols, including baseline groundwater and surface water quality, leachate composition, landfill gas emissions, and operational impacts (Chapter 10)1. They also require regular reporting, specifying the frequency, structure, and content of environmental monitoring reports to ensure transparency and regulatory oversight. These detailed requirements reinforce the obligations under Regulation 73 and provide a framework for KCCA to improve its compliance and public accountability.

The issue of public engagement in waste management remains equally underdeveloped. Regulation 11(2)(k) mandates that all waste generators, handlers, and local governments implement an information, education, and communication (IEC) strategy as part of their environmental management systems. Effective community engagement is highlighted in the Guidelines, which recommend involving local stakeholders in landfill planning, operation, and closure (Chapter 9.5)1. The document also addresses occupational safety, health, and security for landfill workers, an area often overlooked in municipal waste management plans. These aspects are crucial for developing trust, promoting waste literacy, and ensuring safe working conditions for all personnel involved. While Kisaka has emphasized the importance of civic responsibility calling on all city dwellers to take ownership of littering and domestic waste, this rhetoric has not yet been translated into a structured, citywide behavioral change campaign. Informal settlements and low-income neighborhoods continue to suffer disproportionately due to this lack of targeted waste literacy and infrastructure.

Institutional enforcement remains weak. Despite the clarity of Regulations 6, 27, and 104–106 on duties, licensing, and penalties for improper waste handling or littering, illegal dumping and unregulated waste collection remain widespread in Kampala. The 2020 Regulations give KCCA full legal backing to license collectors, require approved disposal routes, and penalize non-compliant actors including citizens, businesses, and informal transporters. However, poor coordination between KCCA, NEMA, and the Ministry of Local Government dilutes enforcement power and undermines accountability.

The National Strategy for Promoting Plastics Circularity in Uganda 2023-2028 emphasizes a comprehensive approach to tackling plastic pollution through five strategic objectives: mitigating plastic waste leakage, promoting recycling and reuse, reducing plastic generation, fostering innovation, and enhancing public awareness (PAGE11). This framework, supported by the National Environment (Waste Management) Regulations, 2020, mandates a waste management hierarchy prioritizing prevention, reduction, reuse, recycling, recovery, and disposal (Reg. 7). However, Kampala’s current waste management practices fall short in implementing these objectives, particularly in enforcing Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes and establishing infrastructure for specialized waste streams like electronic and healthcare waste (PAGE12, Reg. 40–44). Integrating these national priorities into KCCA’s Smart City plan, through targeted EPR programs and public-private partnerships, could significantly enhance the city’s capacity to achieve a circular plastics economy and reduce environmental and public health risks.

In conclusion, Kampala’s waste management landscape is evolving in promising directions, but the reforms remain partial. The Public Health (Amendment) Act, 2023, has improved the statutory responsibilities of local governments and the medical health system, while the National Environment (Waste Management) Regulations, 2020, have introduced modern tools for responsible waste handling, extended producer obligations, and environmental risk mitigation. KCCA’s Smart City strategy for 2024/2025 aligns with several legal mandates particularly on landfill reform and leachate treatment but still falls short in critical areas such as public engagement, electronic waste management, and policy harmonization with national regulations. A deeper institutionalization of the waste hierarchy, enforcement of data and reporting duties, operationalization of EPR, and establishment of inclusive IEC frameworks will be vital for sustainable and lawful waste governance in Uganda’s capital.

Systemic Failures in Kampala’s Waste Management

In August 2024, Kampala’s waste management system suffered a catastrophic setback when a massive landslide occurred at the Kiteezi landfill, killing between 26 and 35 people, burying homes, and leaving dozens missing. Triggered by heavy rains but fundamentally caused by chronic mismanagement and overcapacity, this disaster exposed severe weaknesses in the city’s waste governance and infrastructure. Investigations revealed that Kiteezi had been operating beyond its design capacity for years, with illegal encroachment of homes within the mandatory 200–500 meter buffer zone significantly amplifying the human toll. The tragedy not only highlighted the physical risks of poor landfill management but also underscored the failure of regulatory enforcement and urban planning in protecting vulnerable communities (Reuters, 2024).

Following the disaster, President Museveni took decisive action by dismissing Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) top officials, including Executive Director Dorothy Kisaka, citing criminal negligence. The Uganda Law Society condemned the incident as a “grave failure in urban planning and governance,” emphasizing that warnings about Kiteezi’s overcapacity had been ignored since at least 2019. This leadership shake-up reflects the urgent need for accountability and systemic reform in Uganda’s waste management institutions. The government has since launched investigations and tasked the Prime Minister with relocating residents near the landfill, while also confirming plans to decommission Kiteezi and search for alternative landfill sites (Daily Monitor, 2025).

The operational aftermath of the disaster has been deeply disruptive. Private waste collectors, facing longer travel distances to alternative disposal sites, raised service fees significantly from UGX 5,000 to 25,000 per month triggering public dissatisfaction and unrest. Many displaced residents describe the affected area as a “ghost town,” living in fear of further landslides. Moreover, recurrent fires at the closed landfill, linked to methane build-up, continue to pose environmental and health risks. Although authorities are actively stabilizing the site through flattening and drainage, funding gaps and community resistance have delayed the development of replacement landfills such as Dundu, Katikolo, Nansana, and Nkumba. Despite government efforts to preserve buffer zones and activate emergency response systems, many residents still live within unsafe proximities, highlighting ongoing vulnerabilities (Daily Monitor, 2025), (Kampala Post, 2024).

Figure 1.

KITEEZI WASTE DISASTER.

Figure 1.

KITEEZI WASTE DISASTER.

Kigali’s Waste Management Model: Successes and Limitations

Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, has frequently been cited as a model of urban cleanliness and organized waste management in sub-Saharan Africa. The city has achieved notable success in public sanitation, institutional coordination, and private sector involvement, particularly when compared to cities like Kampala. These outcomes are the result of regulatory reforms, licensing enforcement, and a culture of civic responsibility most visibly expressed through the national clean-up initiative, Umuganda (Squire & Nkurunziza, 2022).

One of Kigali’s most celebrated achievements is its high collection efficiency. Waste is collected once a week from households and daily in public areas, facilitated by 12 licensed waste service providers regulated by the Rwanda Utilities Regulatory Authority (RURA). Each provider must operate a minimum of three trucks, and they serve clients based on tiered user fees adjusted to household income (Squire & Nkurunziza, 2022). Moreover, routine street cleaning, often conducted six days a week, is mandated and monitored for compliance, contributing to Kigali’s visible cleanliness. These efforts are complemented by Umuganda, a mandatory monthly national clean-up day, which, despite varying participation, reinforces a sense of civic duty and collective responsibility (Squire & Nkurunziza, 2022).

Kigali also enforces strict licensing and protective standards for waste handlers. Service providers must prove compliance with occupational safety standards, including PPE use, and failure to meet these requirements can attract fines between RWF 10,000 20,000 (approx. USD 10–20). These safety protocols resonate with the recommendations in Kampala's KIWR Framework, which also advocates for PPE enforcement among waste workers (see KIWR Framework section in your document).

Despite these operational strengths, Kigali's waste management system exhibits critical limitations in sustainability and integration. The model remains heavily centered on collection and disposal, with little emphasis on waste minimization, composting, or recycling. This is concerning given that approximately 70% of Kigali’s waste stream is organic, a proportion that mirrors Kampala’s and offers significant potential for composting and urban agriculture if properly harnessed (Squire & Nkurunziza, 2022).

Moreover, recycling is underdeveloped, due to factors such as poor source separation, lack of incentives, and a weak market for recycled products. Recyclers in Kigali often face challenges in accessing consistent feedstock and covering high energy costs, which are not offset by government subsidies. This gap is addressed directly in the KIWR Framework, which proposes composting hubs, buy-back centers, and subsidies to catalyze a viable circular economy in Kampala.

A further limitation is Kigali’s reliance on the Nduba open dumpsite, which lacks modern leachate management and methane capture systems. While the site is organized and monitored, it cannot be classified as an engineered sanitary landfill. This poses long-term environmental and health risks, particularly from toxic leachates and methane emissions, as documented by Squire and Nkurunziza (2022). In contrast, Kampala’s KIWR Framework proposes investment in engineered landfills like Dundu and Katikolo to replace the failed Kiteezi site and prevent a repeat of its catastrophic collapse.

Institutionally, waste governance in Kigali is fragmented. RURA, REMA, WASAC, and the City Council all play overlapping roles, which can lead to inefficiencies despite the system’s external appearance of success. The City of Kigali lacks autonomous policy-making authority and must depend on directives from national agencies. This top-down structure limits responsiveness and local innovation, a challenge the KIWR Framework seeks to overcome by promoting municipal empowerment and decentralized decision-making within Kampala’s context.

In summary, Kigali’s waste model offers valuable operational insights particularly in enforcement, fee structures, and cleanliness norms which Kampala can adapt. However, its over-reliance on collection and disposal, the absence of modern landfill infrastructure, and a lack of circular economy integration undermine its sustainability. Kampala’s KIWR Framework builds on Kigali’s strengths while addressing these critical gaps, positioning itself as a next-generation urban waste management model tailored to East African cities.

The KIWR Framework: A Resilient Policy Model for Kampala

The Kampala Integrated Waste Resilience (KIWR) Framework presents a holistic model that reimagines urban waste management through an integrated, systems-based lens tailored to Kampala’s unique urban challenges. At the core of this framework lies the Circular Economy Core, built on the globally recognized principles of preventing, reducing, reusing, recycling, and recovering waste. This central philosophy ensures that all waste is viewed not as a burden but as a potential resource, thereby minimizing its environmental and public health impacts.

Surrounding this core are six interlinked pillars, each designed to operationalize key interventions across policy, infrastructure, public engagement, and innovation. The first pillar, Public Health Protection, focuses on expanding sanitation infrastructure: such as sewer connections and latrine upgrades while instituting robust health risk surveillance to monitor and mitigate diseases linked to uncollected or poorly managed waste. The Infrastructure Development pillar seeks to modernize the city’s physical capacity by replacing the collapsed Kiteezi landfill with engineered sites like Dundu and Katikolo, and establishing composting and waste-to-energy facilities to handle Kampala’s 2,500-ton daily waste load.

The third pillar, Regulatory Enforcement, strengthens oversight through mechanisms like Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) for plastics and e-waste, and the creation of transparent waste data systems in line with Uganda’s National Waste Regulations. Community Engagement, the fourth pillar, ensures inclusive participation by launching waste literacy campaigns, especially in informal settlements, and expanding public-private partnerships (PPPs) to improve service delivery and boost collection coverage to over 80%.

To address climate-related vulnerabilities, the fifth pillar Climate Resilience introduces flood-proof waste facilities and methane capture technologies, mitigating risks associated with Kampala’s frequent flooding and unregulated landfill emissions. Lastly, Technology Integration strengthens efficiency and capacity by deploying smart bins, route optimization tools, and workforce training programs aimed at improving operational tracking and building local expertise.

The KIWR Framework functions as a cyclical and adaptive system, flowing through seven key stages: waste prevention and reduction, collection and sorting, processing and resource recovery, health and safety interventions, infrastructure and climate resilience, regulatory enforcement, and continuous feedback for improvement. Each stage is reinforced by cross-pillar collaboration and dynamic feedback loops, ensuring sustainability, resilience, and inclusivity.

By combining lessons from Kigali’s successful PPP and enforcement model with Kampala’s specific needs such as informal settlement health risks, urban flooding, and high organic waste levels the KIWR Framework delivers a pragmatic, health-centered, and climate-conscious solution that can guide Kampala toward a cleaner, safer, and more sustainable future.

Figure 2.

Kampala Integrated Waste Resilience (KIWR).

Figure 2.

Kampala Integrated Waste Resilience (KIWR).

Comparative Insights: Tailoring Lessons from Kigali to Kampala

The comparison between Kigali and Kampala offers valuable insights into how effective waste management models can be adapted, rather than copied, to fit unique urban contexts. Both cities are capitals in East Africa, face rapid urbanization, produce predominantly organic waste, and contend with large informal settlements. However, their governance structures, socio-political environments, and institutional capacities differ considerably. While Kigali has been widely praised for its cleanliness and collection efficiency, Kampala presents a more fragmented and decentralized landscape that requires a tailored and inclusive approach. This section critically examines what Kampala can learn from Kigali, what it must avoid, and how the KIWR Framework offers a more contextualized and sustainable policy pathway.

Kigali’s waste management success stems primarily from its strong central authority, structured licensing systems, and embedded civic culture of cleanliness. As detailed by Squire and Nkurunziza (2022), Kigali maintains over 95% collection coverage through a network of 12 licensed waste service providers, each required to own a minimum of three trucks. These providers operate under strict regulatory oversight by the Rwanda Utilities Regulatory Authority (RURA), and user fees are stratified according to household income ensuring financial sustainability without excluding low-income users.

Kigali’s enforcement system is another best practice Kampala can emulate. Waste workers are required to use personal protective equipment (PPE), and failure to comply results in fines ranging from RWF 10,000 to RWF 20,000. This model resonates with Kampala’s proposed KIWR Framework, which includes PPE enforcement, licensing reform, and data-driven regulatory action to ensure health and safety compliance.

In addition, Kigali has successfully embedded civic responsibility through initiatives such as Umuganda, the national monthly community cleaning day. Although enforcement and participation vary by socioeconomic background, the concept itself cultivates a shared sense of environmental stewardship. Kampala can adapt this principle through localized waste literacy campaigns, particularly targeting informal settlements such as Bwaise and Katwe.

Limitations in Kigali’s Model: What Kampala Must Avoid

Despite its strengths, Kigali’s waste management model is primarily focused on waste collection and disposal, with minimal emphasis on waste minimization or circular economy strategies. As Squire and Nkurunziza (2022) observe, recycling, composting, and reuse remain significantly underdeveloped. This is problematic considering that over 70% of Kigali’s waste stream is organic, mirroring Kampala’s situation. The lack of structured composting or waste-to-energy infrastructure represents a missed opportunity for resource recovery and environmental sustainability.

Additionally, Kigali continues to rely on the Nduba dumpsite, which, while better organized than Kampala’s Kiteezi landfill, is still an unlined, non-engineered open dump lacking methane capture or leachate treatment. This poses long-term environmental risks and stands in contrast to the KIWR Framework’s proposal for engineered landfills at Dundu and Katikolo, designed to meet both public health and climate resilience standards.

Institutional fragmentation also presents a governance challenge in Kigali. Waste-related responsibilities are divided among RURA, REMA, WASAC, and the City Council, leading to overlap and inefficiencies. The City of Kigali lacks autonomous policymaking authority and is largely dependent on national directives. Kampala, with its decentralized administrative setup under KCCA and the Ministry of Water and Environment, must avoid this top-down rigidity by empowering municipal divisions and strengthening multi-sectoral coordination.

The KIWR Framework: Building on Kigali, Advancing Further

The Kampala Integrated Waste Resilience (KIWR) Framework draws inspiration from Kigali’s operational strengths but goes further by integrating public health protection, waste minimization, climate resilience, and technological innovation. While Kigali’s model effectively emphasizes enforcement and collection efficiency, KIWR recognizes the importance of decentralized, inclusive, and circular approaches to suit Kampala’s high waste volume, flooding risks, and slum-dominated urban fabric.

A comparative analysis highlights this evolution:

| Feature |

Kigali Model |

Kampala (KIWR Framework) |

| Waste Collection Coverage |

95% via 12 licensed PPPs |

Target 80% via PPP + integration of informal sector |

| Recycling & Composting |

Limited infrastructure and low prioritization |

Citywide composting, buy-back centers, and reuse incentives |

| Enforcement & PPE |

Strict fines for noncompliance |

Expanded regulation with EPR, PPE mandates, and audit systems |

| Landfill Infrastructure |

Nduba dumpsite, lacking engineering or gas capture |

Engineered landfills (Dundu, Katikolo) with methane systems |

| Community Engagement |

Umuganda (monthly) and basic awareness efforts |

Continuous IEC campaigns in local languages, school programs |

| Health Integration |

Minimal health monitoring |

Disease tracking, sanitation expansion, PPE for waste workers |

| Technology Integration |

Absent |

IoT waste monitoring, GIS route optimization, data dashboards |

This table demonstrates how KIWR contextualizes and extends Kigali’s model, particularly in addressing neglected areas such as food waste, flood resilience, informal settlement inclusion, and real-time data usage.

Strategic Takeaways for Kampala

In tailoring Kigali’s lessons, Kampala must strike a careful balance: adopt Kigali’s discipline and partnership structure, but avoid its overly centralized, disposal-heavy approach. Instead, Kampala’s KIWR model should serve as a next-generation urban waste policy framework, advancing beyond Kigali by embedding resilience, circularity, public health safeguards, and technological capacity all essential for a sustainable and equitable waste future.

By learning what to replicate and what to reform, Kampala has the opportunity to become a leader in urban waste transformation in Africa, rather than a city reacting to crisis. KIWR offers that blueprint.

Implementation Roadmap and Policy Recommendations

Addressing Kampala’s waste crisis demands more than visionary frameworks; it requires clear, phased implementation and actionable policy interventions grounded in Uganda’s urban realities. The Kampala Integrated Waste Resilience (KIWR) Framework provides a comprehensive model, but its success hinges on a realistic roadmap, strong governance, sustained funding, and inclusive stakeholder engagement. This section outlines a three-phase roadmap and presents evidence-based policy recommendations tailored for Kampala's urban health, environmental sustainability, and institutional capacity.

Three-Phase Implementation Roadmap

Objective: Establish enabling systems and address emergency risks

Key Actions:

Declare waste and sanitation a public health priority in Kampala District Development Plans

Finalize and fund Dundu engineered landfill (OR a more appropriate landfill) as a replacement for Kiteezi

Roll out 10 pilot PPPs in underserved divisions (e.g., Kawempe, Makindye)

Launch citywide IEC campaigns in 5 local languages targeting slums and markets

Enforce PPE and licensing regulation for all registered waste collectors (align with Regulations 6, 27, 104–106)

Begin IoT waste monitoring pilot using smart bins and digital dashboards in central Kampala

Objective: Scale infrastructure, integrate community systems

Key Actions:

Commission composting plants for food and organic waste near Nakasero, Nakawa, and Owino markets

Launch Buy-Back Centers to support informal recyclers and incentivize plastics recovery

Integrate informal collectors into KCCA database and offer equipment support

Implement EPR obligations on plastic packaging and e-waste producers, backed by Parliament

Mandate transparent waste audits from private waste firms and city divisions

Objective: Institutionalize circular economy, build climate and health resilience

Key Actions:

Install methane capture systems at Dundu and Katikolo landfills

Subsidize biogas units and solar composters for schools and health centres

Train 1,000 waste workers and regulators in circular economy operations

Digitize waste-to-health tracking: Link waste exposure with disease surveillance in Bwaise, Katwe

Integrate KIWR monitoring into Uganda’s national urban health indicator framework

Policy Recommendations

-

Anchor Waste Management in National Health Strategy

Integrate urban waste governance into Uganda’s Health Sector Development Plan (HSDP V)

Recognize sanitation, flooding, and e-waste exposure as major public health threats

-

Reform Waste Regulation and Enforcement

-

Institutionalize Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) with Equity Goals

Use performance-based contracts to reward coverage in informal settlements

Allow fee subsidization for low-income households (e.g., through utility bills or local revenue sharing)

-

Fund Decentralized Composting and Waste-to-Energy Infrastructure

-

Establish a Kampala Waste Observatory

Expected Outcomes by the 5th year

| Indicator |

Baseline (2024) |

Target (2030) |

| Collection coverage |

40–60% |

≥80% |

| Composting of organic waste |

<5% |

≥60% of total organic |

| Informal waste worker inclusion |

Unregistered |

≥75% formally integrated |

| Disease outbreaks (waste-related) |

Frequent in slums |

Reduced by ≥50% |

| EPR compliance rate (plastic/e-waste) |

<10% |

≥70% |

| Sanitary landfill coverage |

1 collapsed (Kiteezi) |

2 modern landfills active |

| Waste data transparency |

Irregular |

Real-time digital access |

Risks and Mitigation Strategies

| Risk |

Mitigation |

| Resistance to regulation |

Use IEC campaigns and participatory planning |

| PPP underperformance |

Introduce KPIs, enforce performance contracts |

| Budget constraints |

Mobilize donor and city co-financing, EPR levies |

| Informal sector marginalization |

Create inclusive legal framework and support units |

| Flood-related disruption |

Invest in flood-proof infrastructure and planning |

Conclusion: From Collapse to Resilience

Kampala’s waste management system stands at a critical crossroads. Years of underinvestment, weak enforcement, infrastructural collapse epitomized by the 2024 Kiteezi landfill disaster and neglect of informal settlements have culminated in a public health crisis with far-reaching environmental, social, and economic consequences. Yet, this collapse also presents a unique opportunity: to reimagine urban waste governance through a lens of health equity, environmental justice, and circular economy resilience.

This paper has demonstrated that while Kigali’s model provides valuable operational insights notably in terms of waste collection efficiency, licensing, and civic engagement it is not a one-size-fits-all solution. Kigali’s centralized, collection-focused system falls short in areas critical to Kampala’s context, such as organic waste recovery, decentralized infrastructure, informal sector inclusion, and climate-sensitive planning. Thus, mere replication of Kigali’s model would be inadequate and potentially regressive.

The Kampala Integrated Waste Resilience (KIWR) Framework, proposed in this study, is a contextualized, multi-dimensional model rooted in six pillars: Circular Economy, Public Health Protection, Infrastructure Development, Regulatory Enforcement, Community Engagement, and Climate & Technology Integration. By embedding health systems thinking into waste management and placing resilience at the core of urban policy, KIWR responds not only to the current waste crisis but to the broader development and equity challenges Kampala faces.

Implementation of the KIWR Framework requires strategic planning, phased investment, intersectoral coordination, and inclusive governance. It also necessitates a shift from reactive waste collection to preventive, regenerative, and data-driven interventions that protect public health, reduce environmental risk, and create economic opportunities especially for marginalized communities in informal settlements. With proper execution, Kampala can transition from a state of unmanaged collapse to a model of resilience, setting a precedent for other rapidly urbanizing African cities confronting similar dilemmas.

Ultimately, solving Kampala’s waste crisis is not simply a matter of infrastructure, it is a question of urban health justice. Resilience in waste governance must be people-centered, environmentally sustainable, and informed by locally driven policy innovation. This paper serves as a foundation for that vision and a call to action for policymakers, researchers, funders, and communities alike.

Glossary of Key Terms

-

1.

Circular Economy

A regenerative economic model that aims to minimize waste and pollution by emphasizing prevention, reduction, reuse, recycling, and recovery of materials in a closed-loop system.

-

2.

Public-Private Partnership (PPP)

A cooperative arrangement between government and private sector entities for the delivery of public services or infrastructure such as waste collection often involves cost-sharing and joint management.

-

3.

Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR)

An environmental policy approach that holds manufacturers and importers legally responsible for the post-consumer lifecycle of their products, particularly packaging, plastics, and e-waste.

-

4.

Composting

The biological decomposition of organic waste (such as food and yard waste) into a nutrient-rich soil amendment, used as a sustainable alternative to chemical fertilizers and landfilling.

-

5.

Waste-to-Energy (WTE)

A process that converts non-recyclable waste materials into usable forms of energy—such as electricity or heat—through combustion, gasification, or anaerobic digestion.

-

6.

Engineered Landfill

A scientifically designed and regulated site for waste disposal that incorporates liners, leachate collection, and gas extraction systems to prevent environmental contamination.

-

7.

Sanitation Infrastructure

Physical systems and services such as sewer lines, latrines, and waste treatment plants that enable the safe disposal of human excreta and protect public health.

-

8.

Waste Segregation

The process of separating waste into different categories (organic, plastic, medical, recyclable) at the source to facilitate efficient recycling, treatment, or disposal.

-

9.

Leachate

A polluted liquid that drains from landfills or waste piles and may contaminate soil, groundwater, or surface water if not properly managed.

-

10.

Methane Capture

The process of collecting methane gas released from decomposing organic waste in landfills for energy use or flaring to prevent greenhouse gas emissions.

-

11.

IoT-Enabled Waste Monitoring

Use of Internet of Things (IoT) technology: such as smart bins and GPS tracking to monitor waste levels, optimize collection routes, and improve operational efficiency.

-

12.

Health Risk Surveillance

Systematic monitoring and analysis of disease trends and environmental hazards to detect and respond to public health threats related to poor waste management.

-

13.

Informal Settlements

Densely populated urban areas with inadequate access to basic services such as sanitation, clean water, and regulated waste collection commonly referred to as slums.

-

14.

Climate Resilience

The capacity of infrastructure and communities to anticipate, withstand, and recover from climate-related shocks such as flooding and extreme weather events.

-

15.

Environmental Health

A branch of public health concerned with how environmental factors: including waste, water, air, and housing affect human health and well-being.

References

- Squire, J. N. T., & Nkurunziza, J. (2022). Urban Waste Management in Post-Genocide Rwanda: An Empirical Survey of the City of Kigali. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 57(4), 760–772. [CrossRef]

- Aryampa, S., Maheshwari, B., Sabiiti, E. N., Bateganya, N. L., & Olobo, C. (2021). Adaptation of EVIAVE methodology to landfill environmental impact assessment in Uganda – A case study of Kiteezi landfill. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 183, 104310.

- CISL. (2024). Kiteezi landfill collapse exposes critical need for waste management reform. Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership. Retrieved from www.cisl.cam.ac.uk.

- Local Governments (Kampala City Council) (Solid Waste Management) Ordinance. (2000). Uganda Legal Information Institute.

- NEMA. (2019). National Environment Management Authority Report on Waste Management in Uganda.

- Parliament of Uganda. (2024). Kiteezi Landfill to be decommissioned after tragic collapse. Retrieved from www.parliament.go.ug.

- Behuria, P. (2021). Journal of Modern African Studies, 59(2), 223–252.

- Fuhrimann, S., Stalder, M., Winkler, M. S., Niwagaba, C. B., Babu, M., Masaba, G., ... & Utzinger, J. (2016). Microbial and chemical contamination of water, sediment and soil in the Nakivubo wetland area in Kampala, Uganda. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 188(5), 1–17. [CrossRef]

- GIZ. (2023). Sector Brief Uganda: Waste and Recycling. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/giz2023-en-sectorbrief-uganda-waste.pdf.

- KCCA. (2020). Waste Management PPP Project Report. Kampala Capital City Authority.

- Public Health (Amendment) Act, 2023.

- Nuwematsiko, R., Nabirye, R., Oria, H., & Iramiot, J. (2021). Practices and challenges of e-waste management in Kampala, Uganda: A cross-sectional study. Environmental Health Insights, 15, 11786302211022460. [CrossRef]

- National Environment (Waste Management) Regulations, 2020 (S.I. No. 49 of 2020).

- National Environment Management Authority (2024). National Strategy for Promoting Plastics Circularity in Uganda 2023-2028. Kampala.

- Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA). (July 19, 2024). Press conference on the Smart City Waste Management Strategy FY 2024/2025. Mayor’s Parlor, Kampala.

- Okaali, D. A., Nyenje, P. M., & Mbabazi, W. (2022). Linking urbanization, flooding, and health risks in Kampala city, Uganda. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 32(1), 27–41. [CrossRef]

- Paetow, M., & Womer, A. (2024). Reducing the Waste Burden in Ugandan Cities. International Growth Centre (IGC). https://theigc.org/publications/reducing-the-waste-burden-in-ugandan-cities/.

- Ssemugabo, C., Wafula, S. T., Ndejjo, R., & Musoke, D. (2020). Perceptions and practices on waste management among urban youth in Kampala, Uganda. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2020, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Ssepuuya, G., Ekou, J., Okello, S., Atukunda, G., & Kugonza, D. R. (2023). Household food waste and its public health implications in urban Uganda: An exploratory study. BMC Public Health, 23(1), 642. [CrossRef]

- Wafula, S. T., Ssemugabo, C., Ndejjo, R., & Musoke, D. (2019). Healthcare waste management among health workers and associated challenges in primary health facilities in Kampala, Uganda. Scientific African, 4, e00103. [CrossRef]

- Daily Monitor. (2025, January 28). Four months after garbage disaster, Kiteezi turns into ghost town.

-

https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/news/national/four-months-after-garbage-disaster-kiteezi-turns-into-ghost-town-4854844.

- Kampala Post. (2024, August 16). KCCA blames external factors for Kiteezi landfill disaster. https://kampalapost.com/content/kcca-blames-external-factors-kiteezi-landfill-disaster.

- Reuters. (2024, August 10). Landslide kills eight in Ugandan capital. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/landslide-kills-eight-ugandan-capital-2024-08-10/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).