Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Virtual Surgical Planning, Computer-Aided Design and Manufacturing Technologies in Clinical Cases

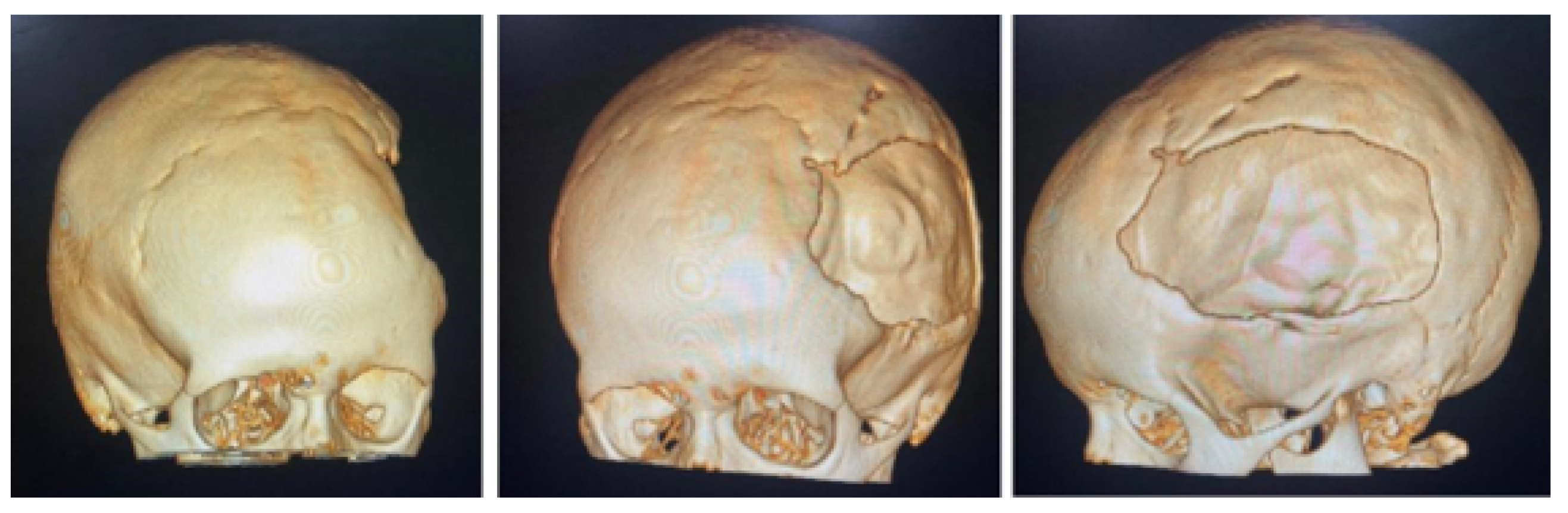

3.1. Case 1: Skull Trauma Sequel

3.1.1. Diagnosis and Analysis

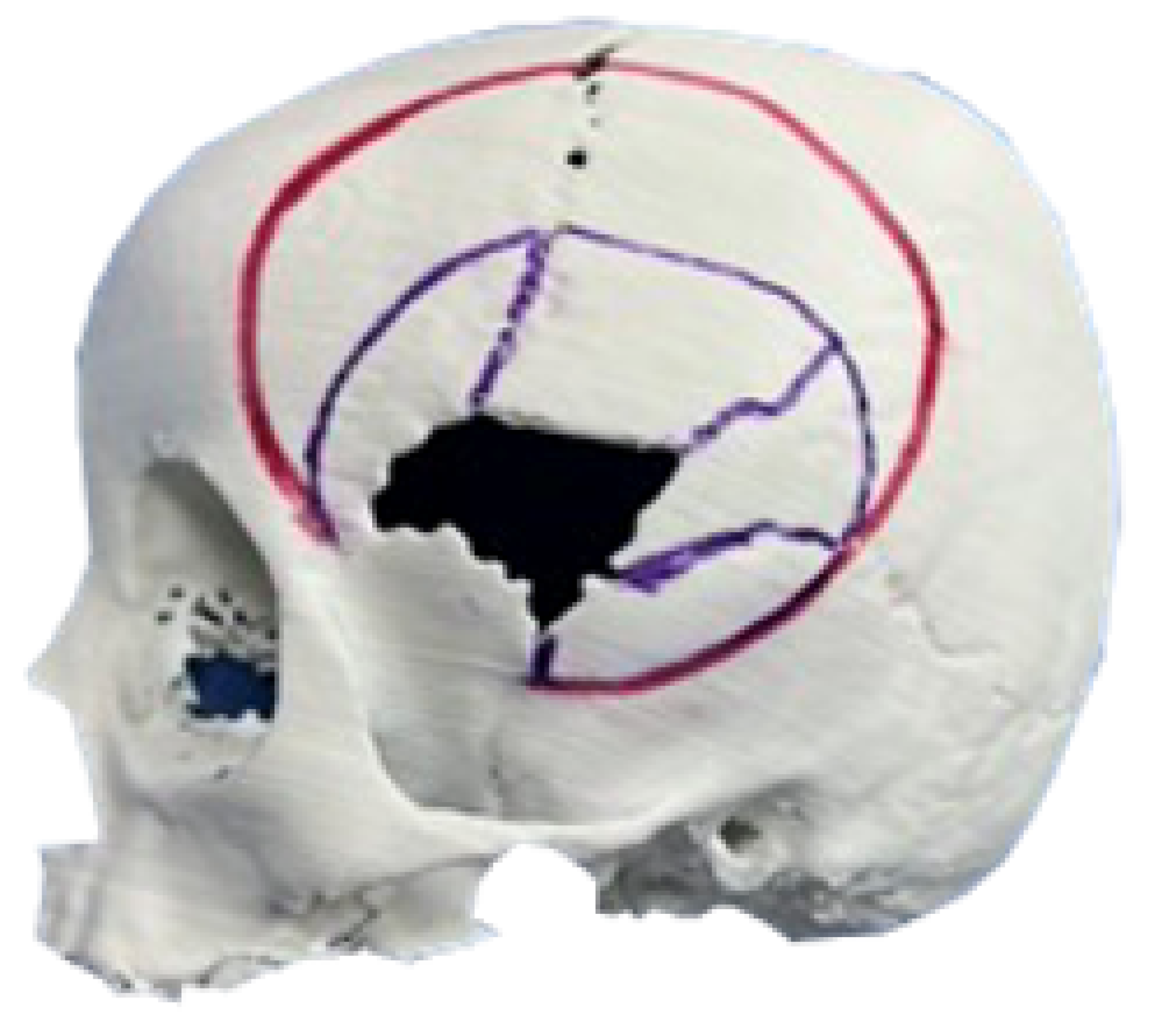

3.1.2. Surgical Planning

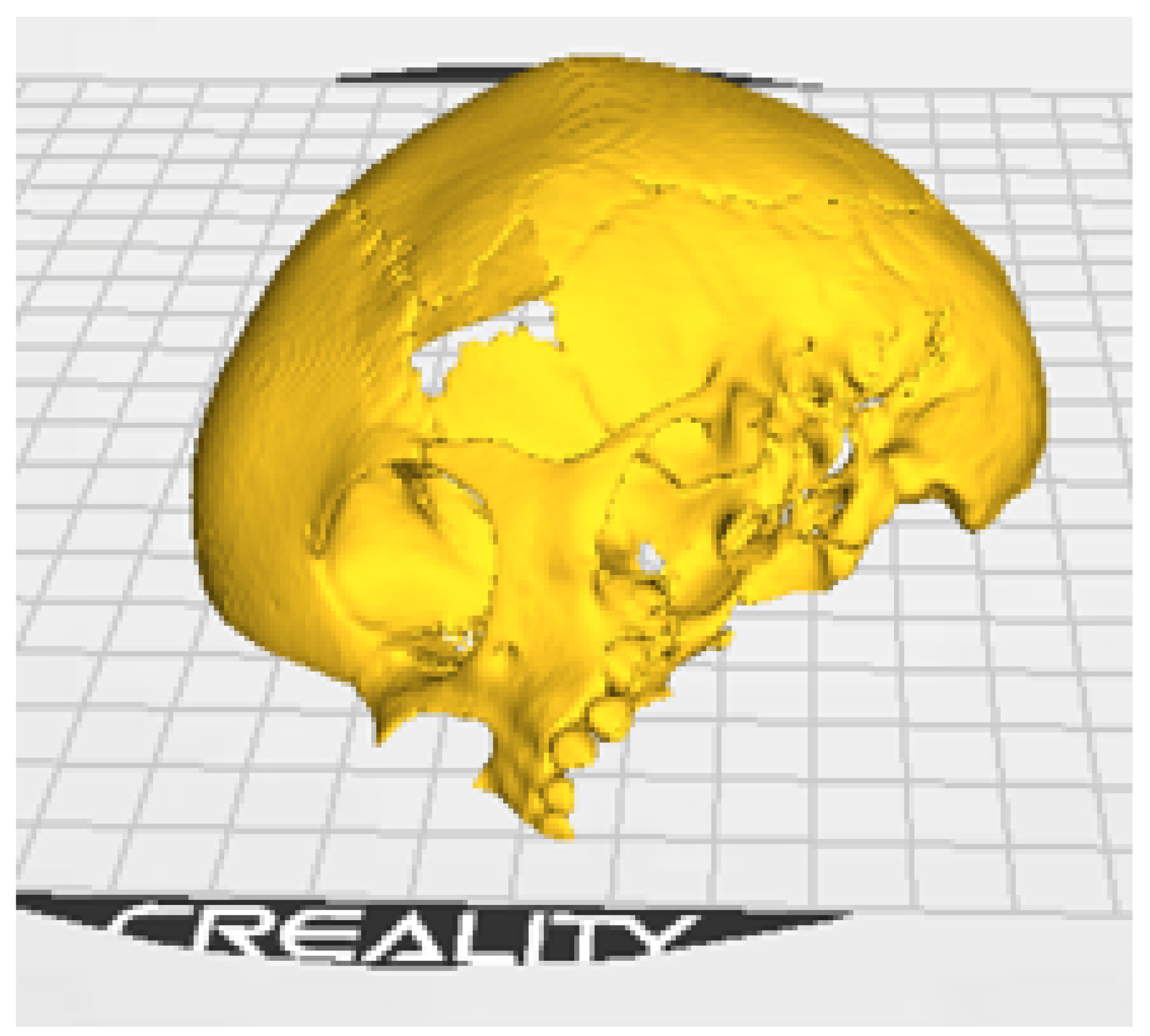

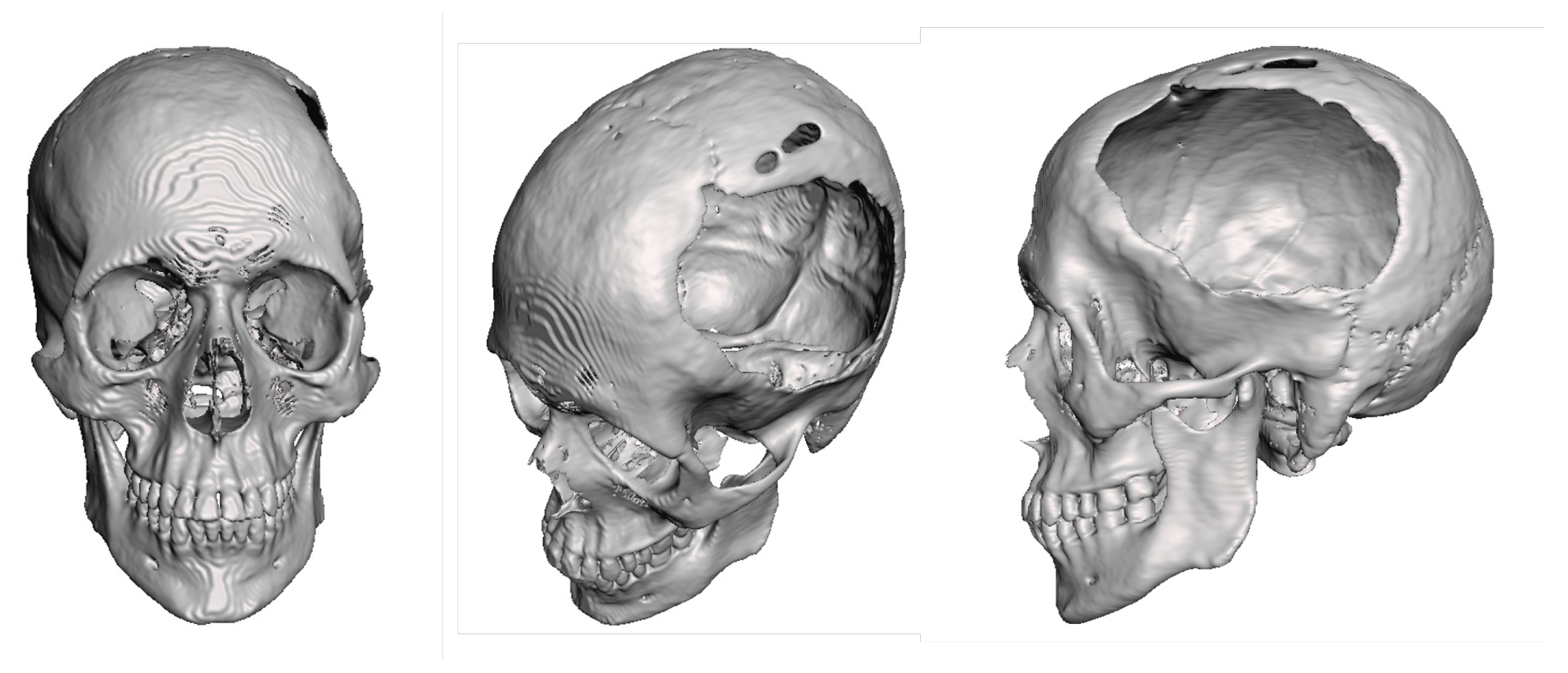

3.1.3. Planning and Printing Anatomical Model

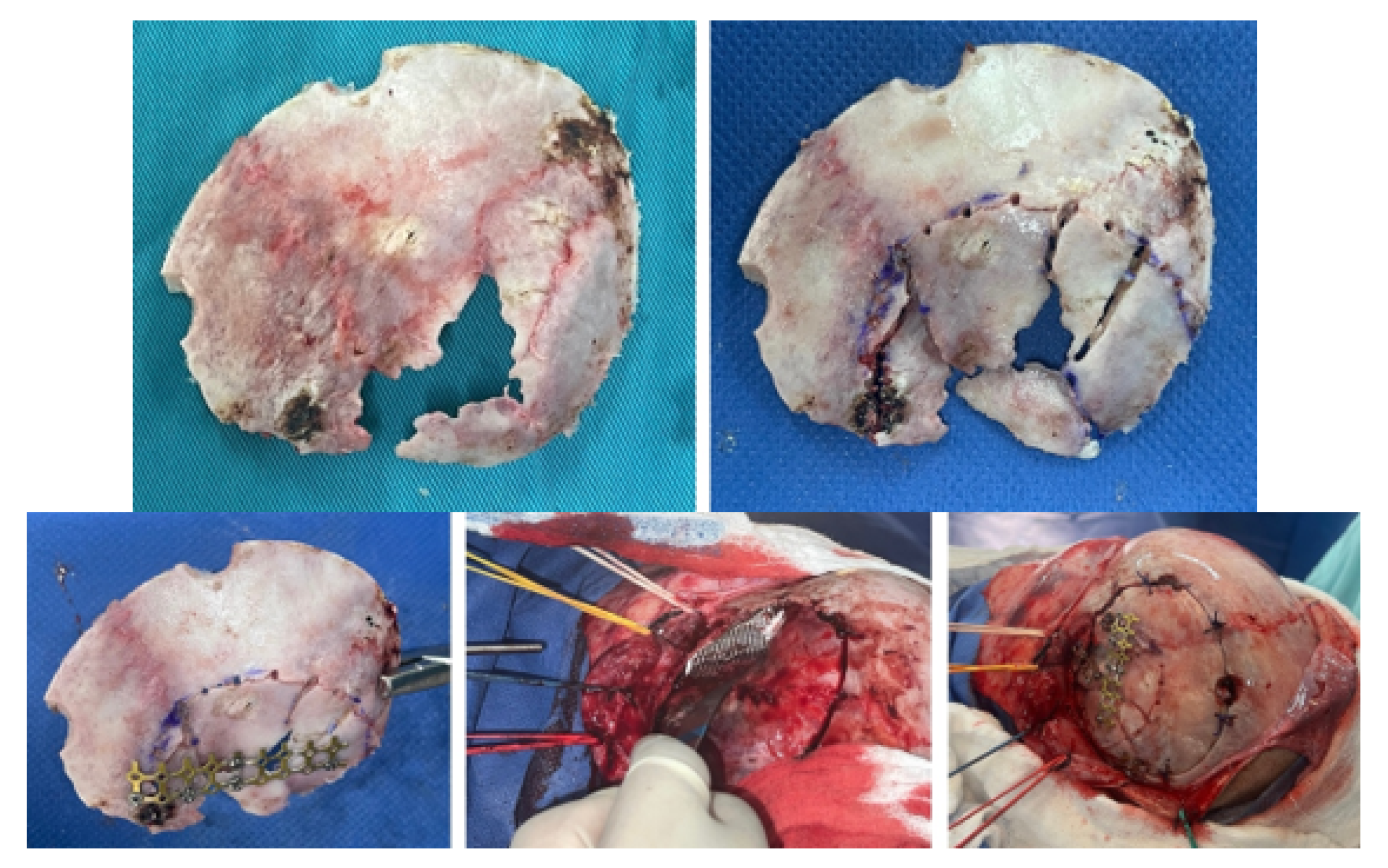

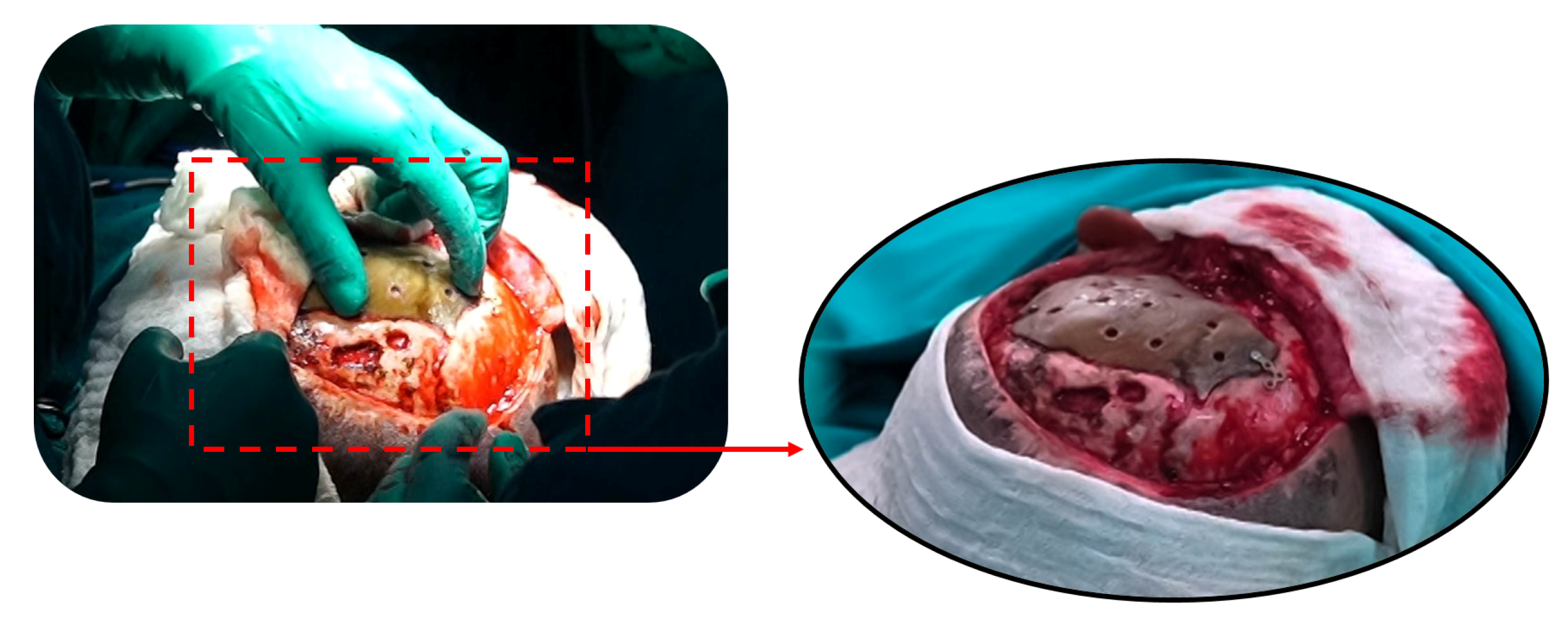

3.1.4. Intraoperative Approach

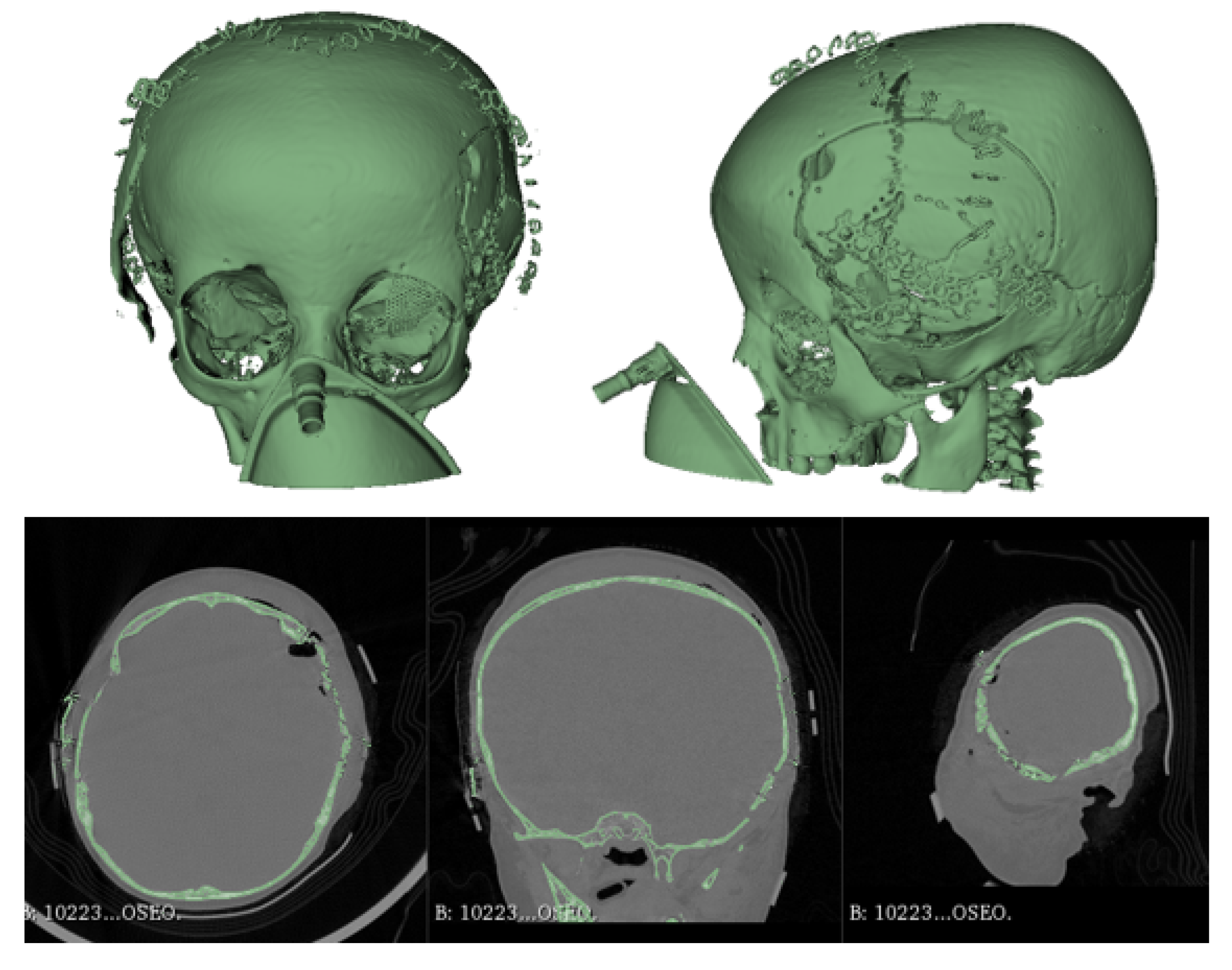

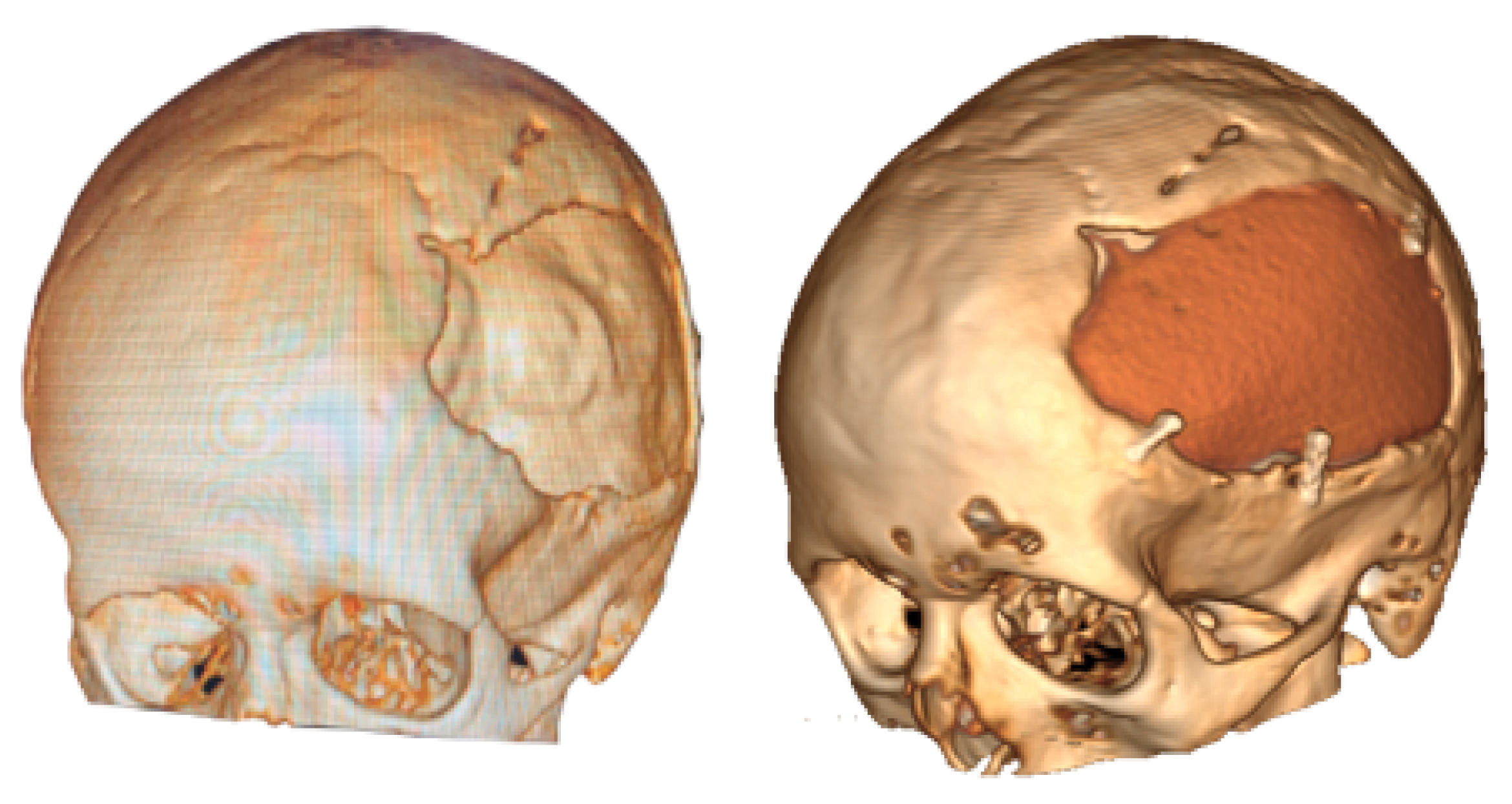

3.1.5. Postoperative

3.2. Case 2: Skull Trauma Sequel

3.2.1. Diagnosis and Analysis

3.2.2. Surgical Planning

3.2.3. Anatomical Model Printing

3.2.4. Intraoperative Approach

3.2.5. Post-Operative Results

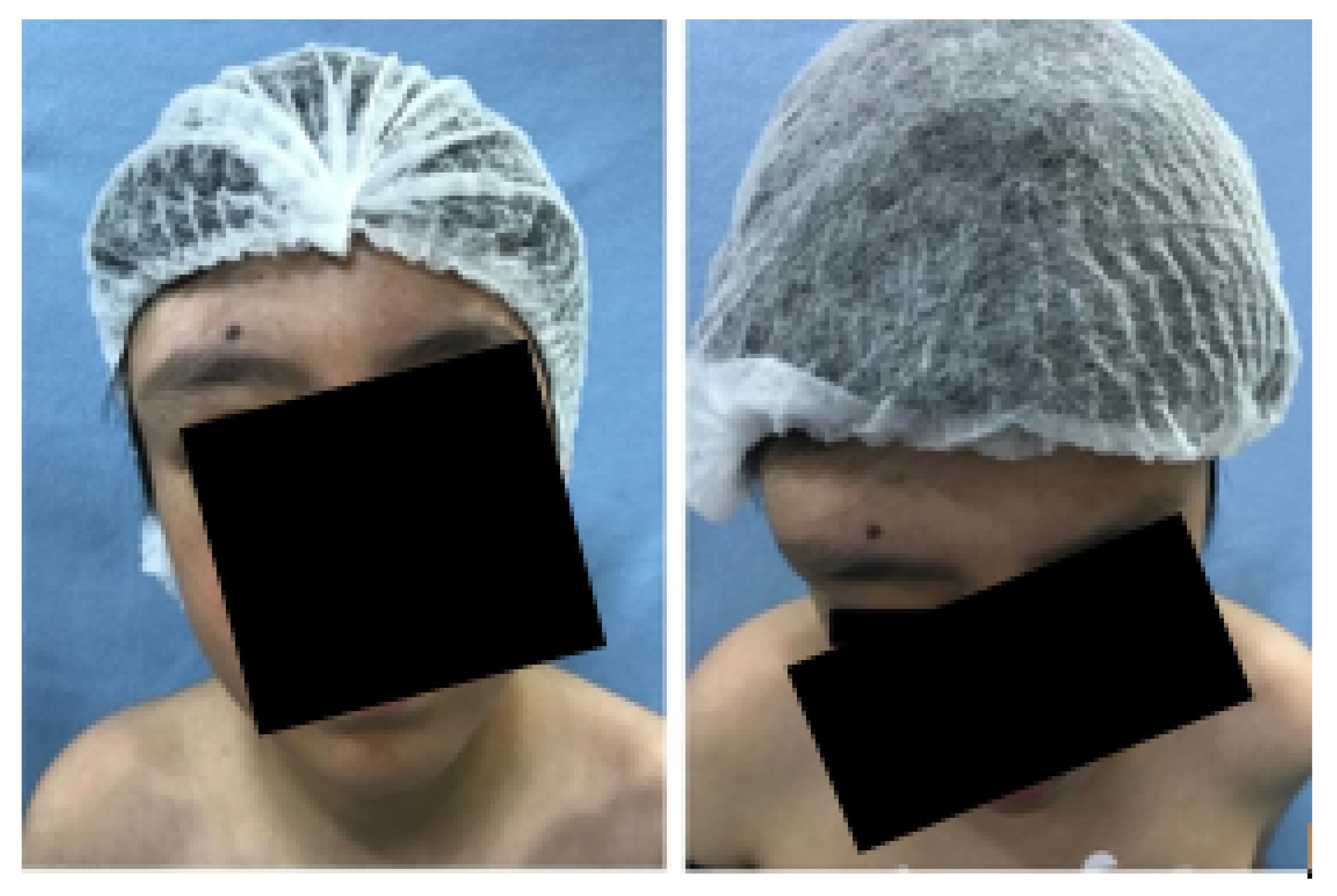

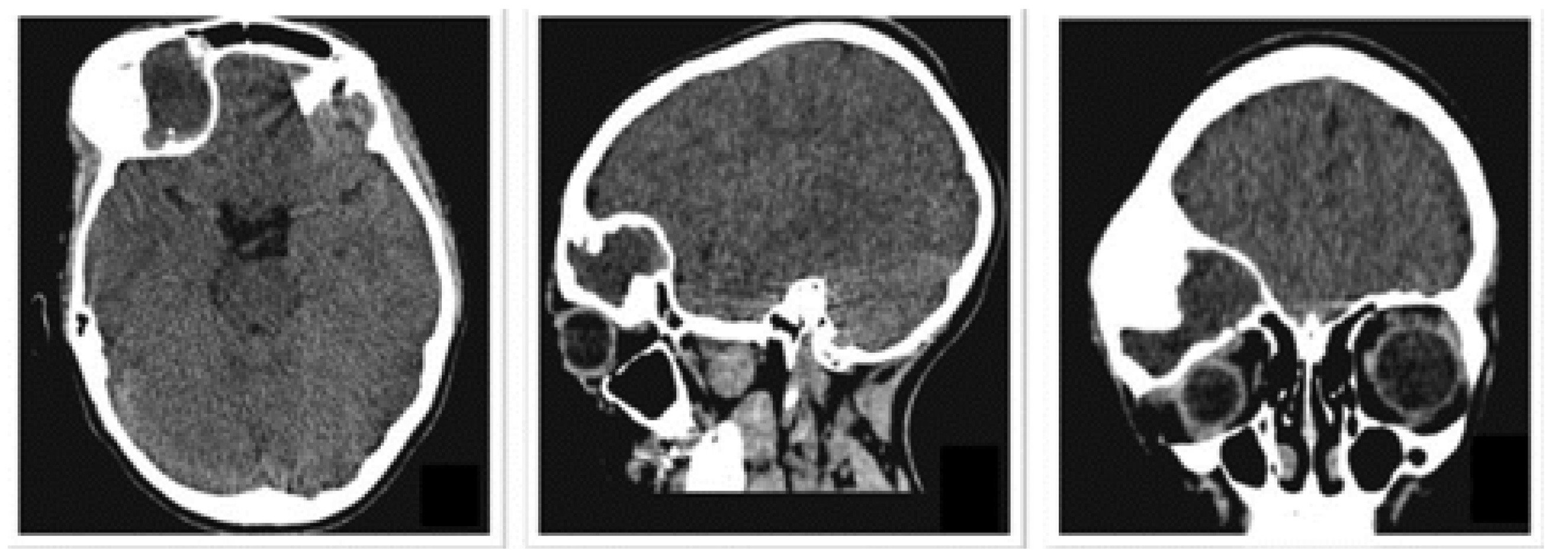

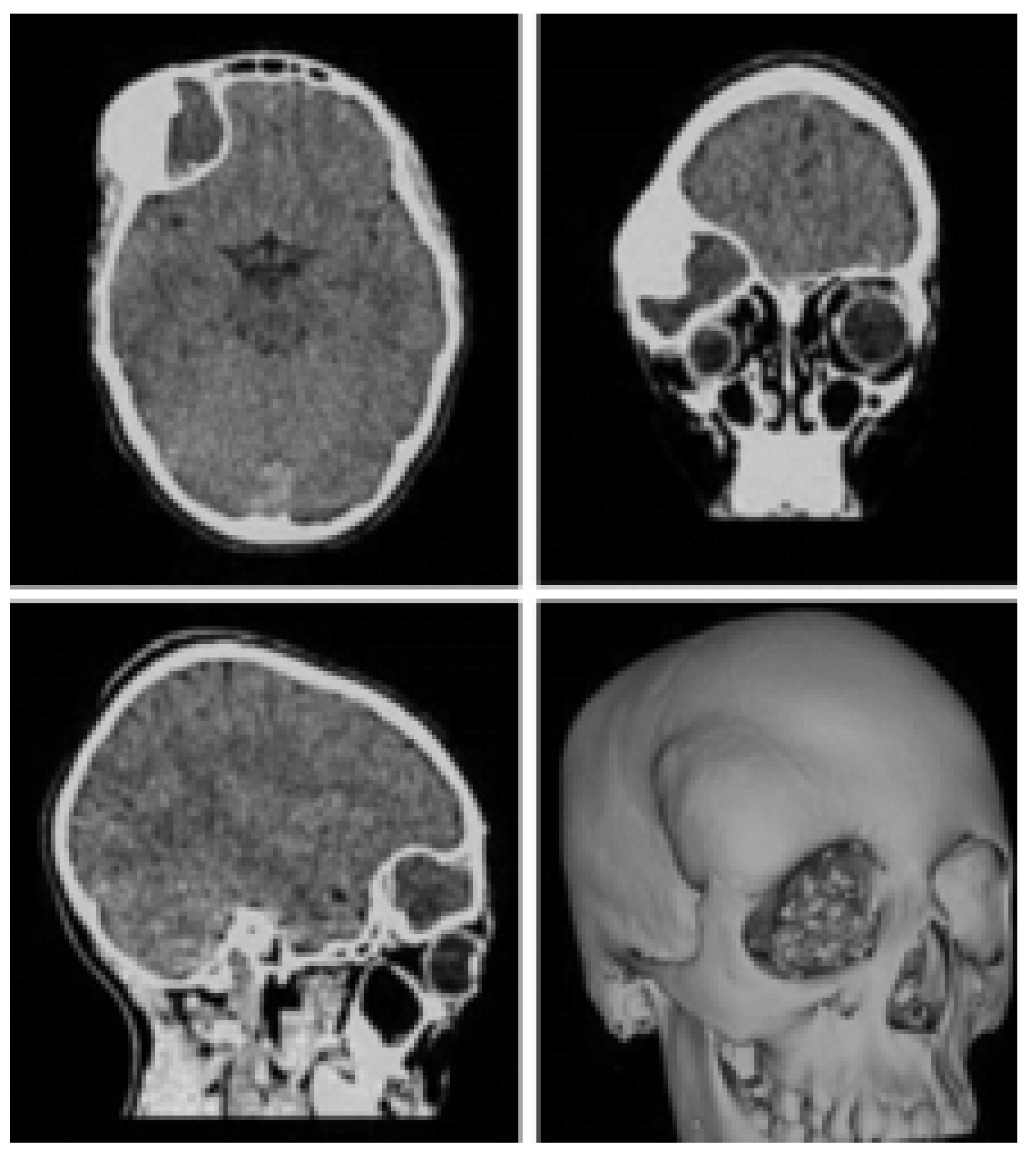

3.3. Case 3: Osteofibrous Dysplasia

3.3.1. Diagnosis and Analysis

3.3.2. Surgical Planning

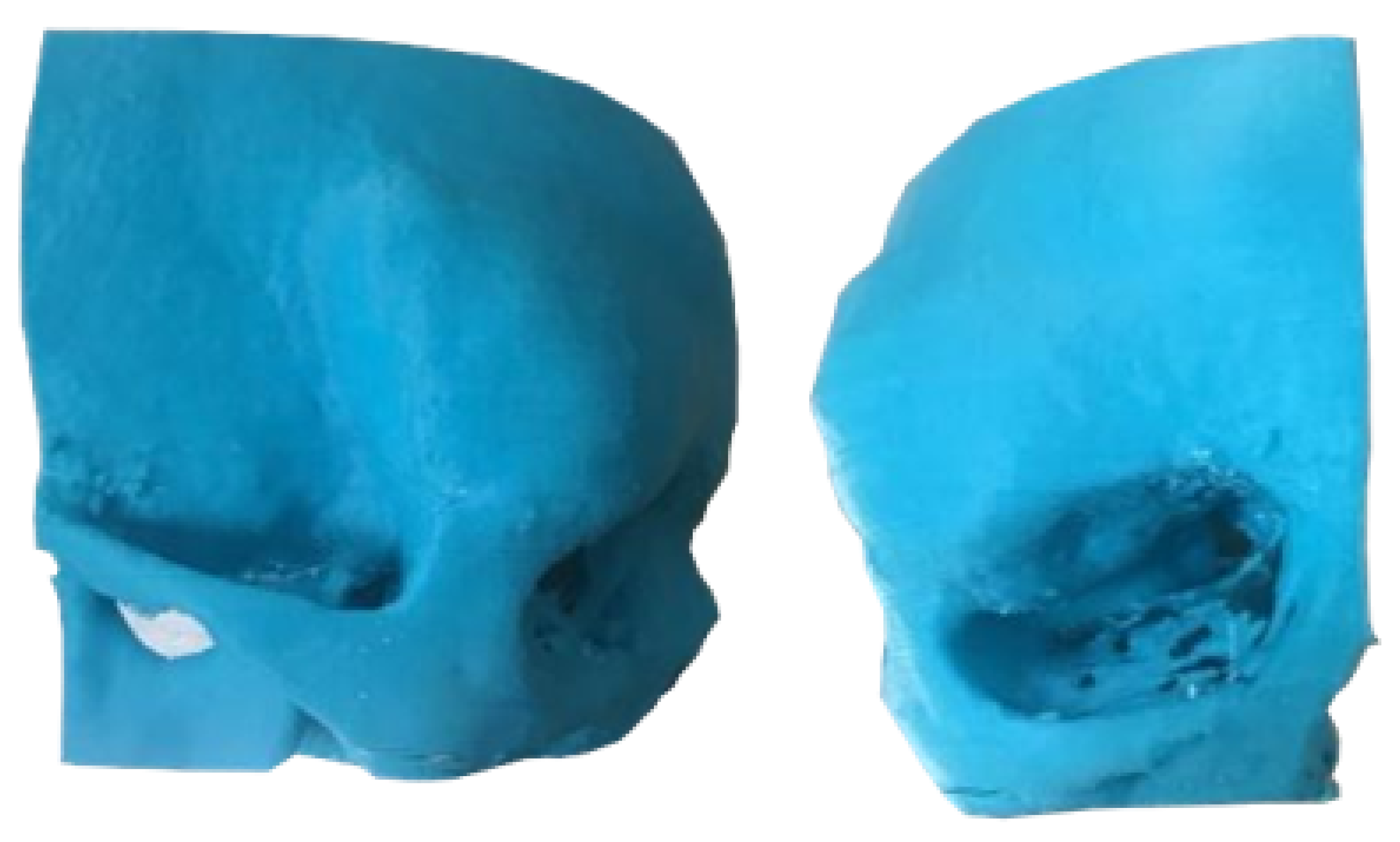

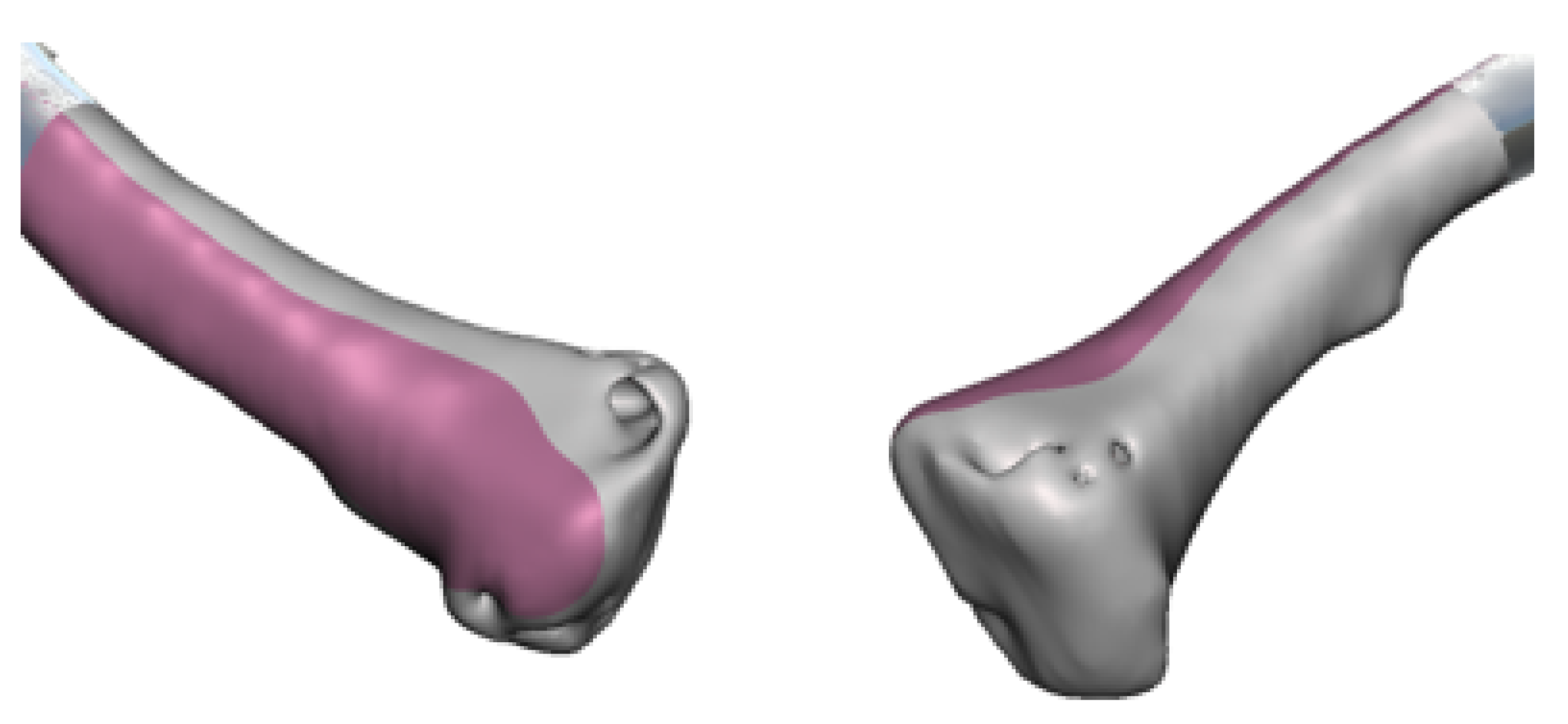

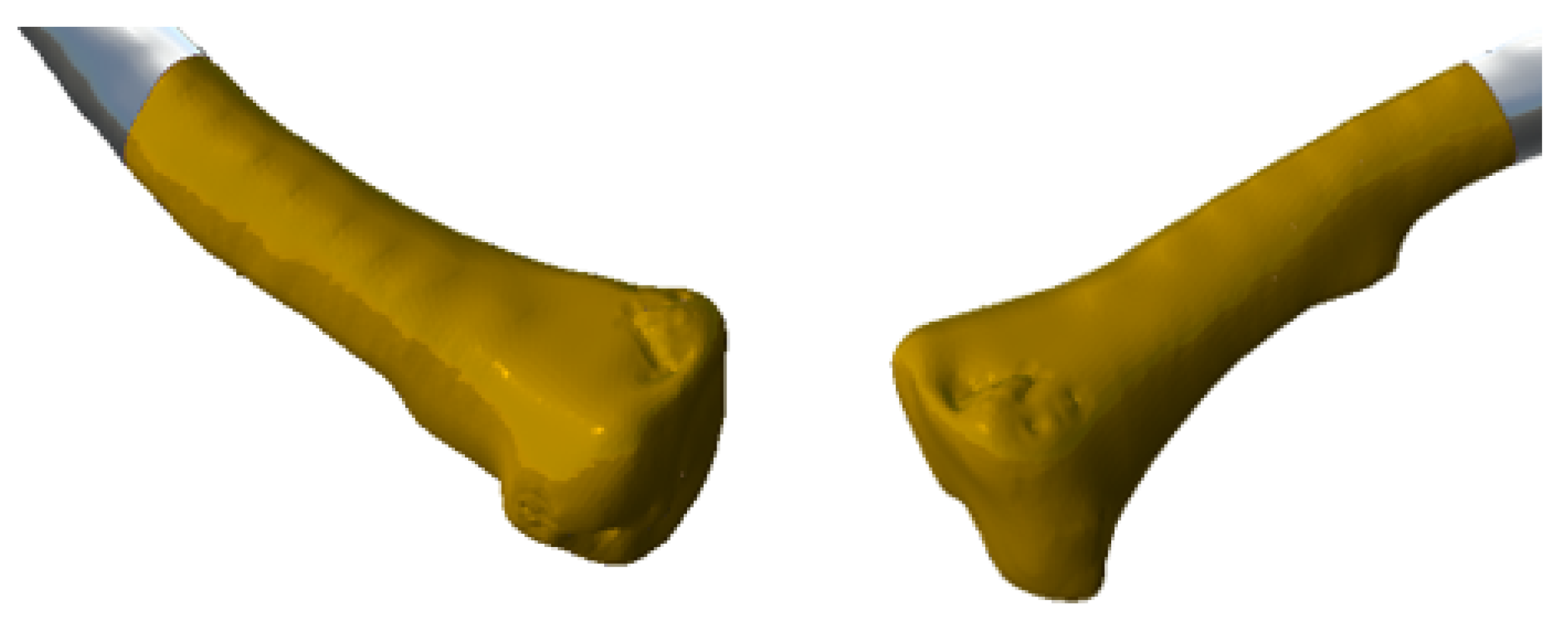

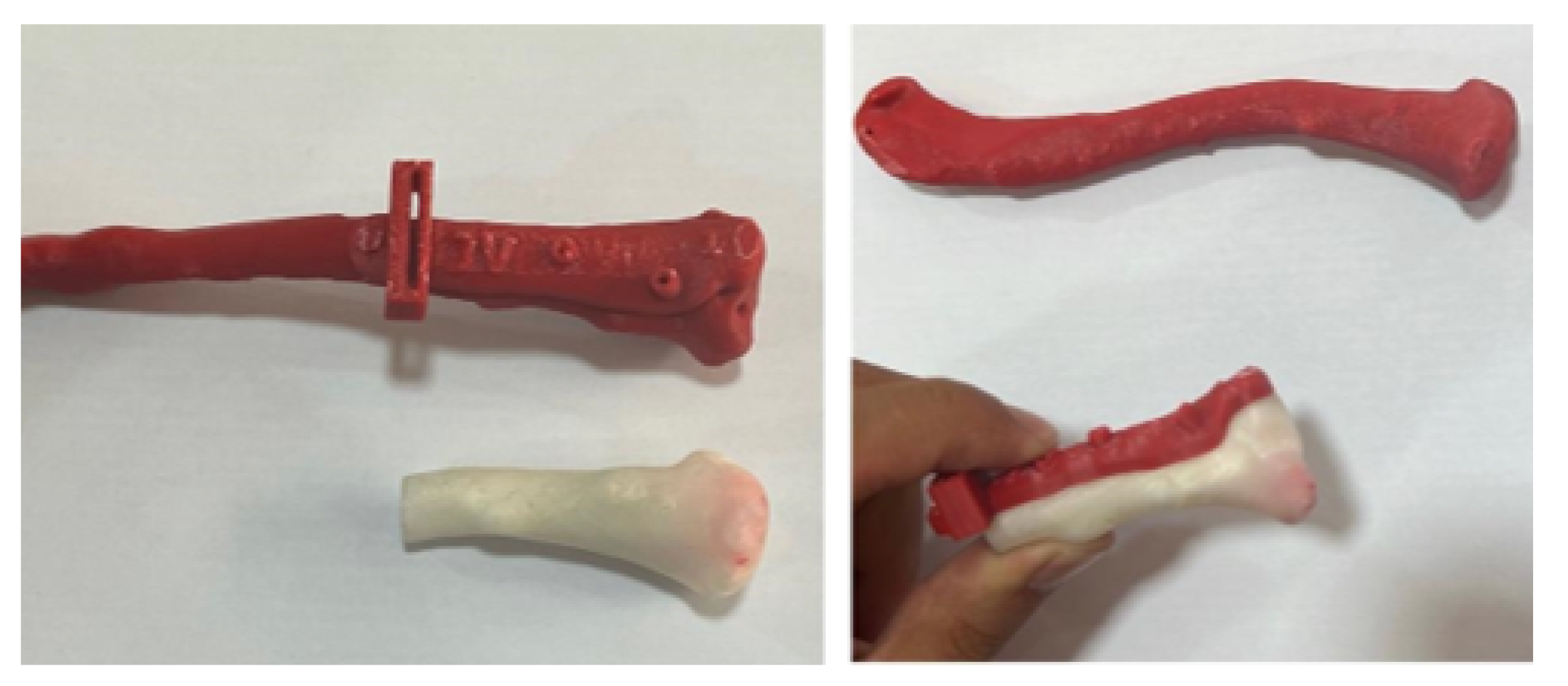

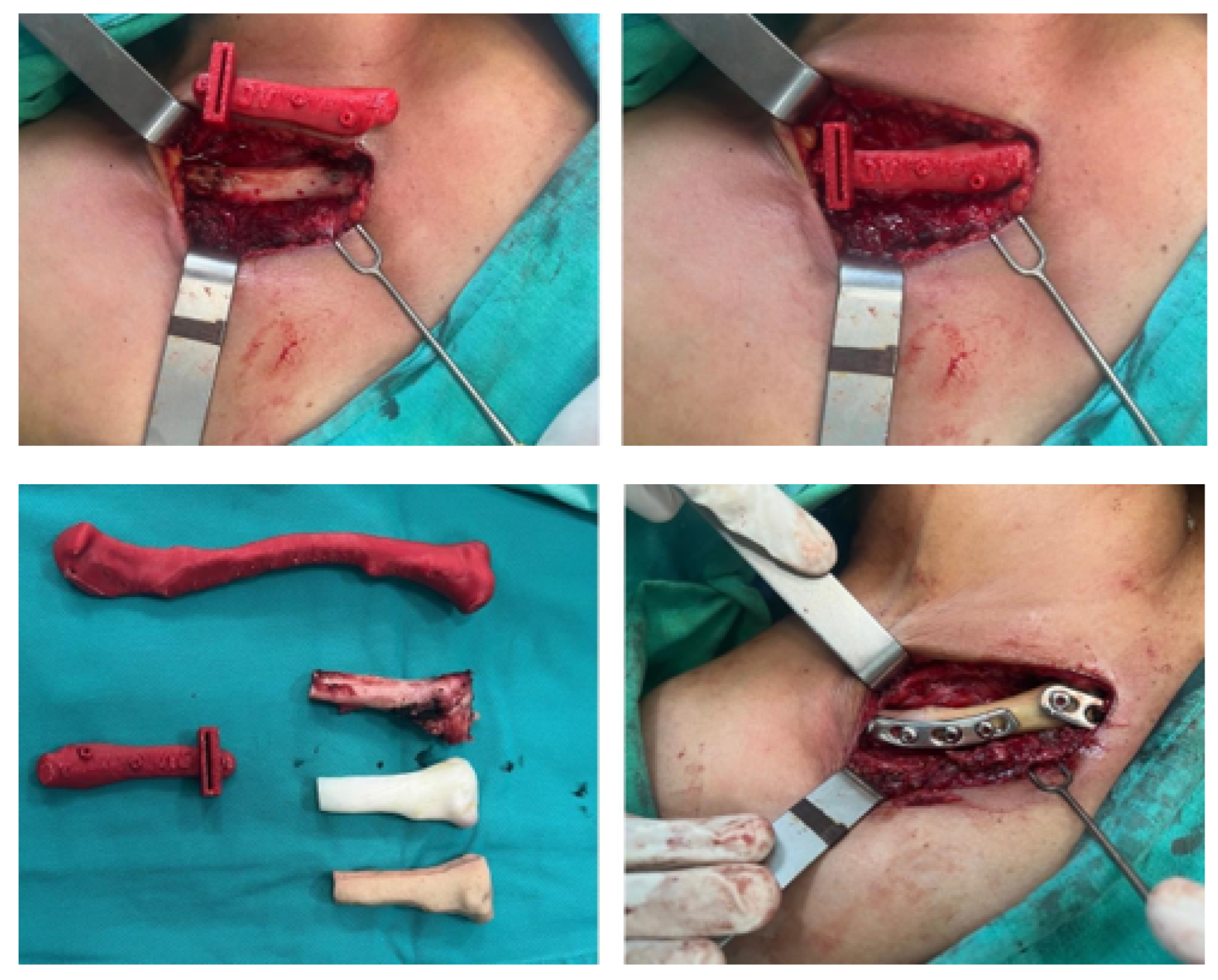

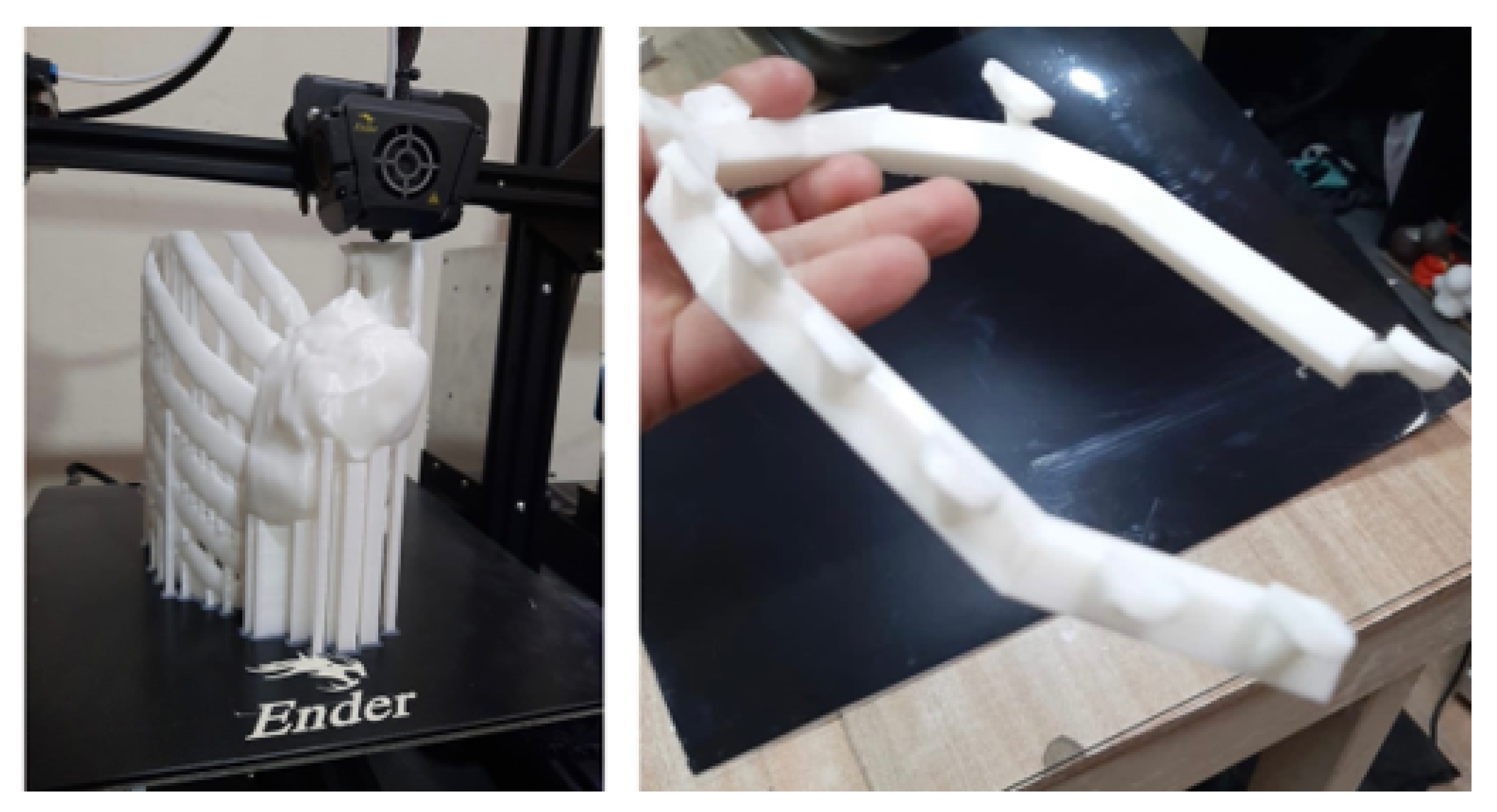

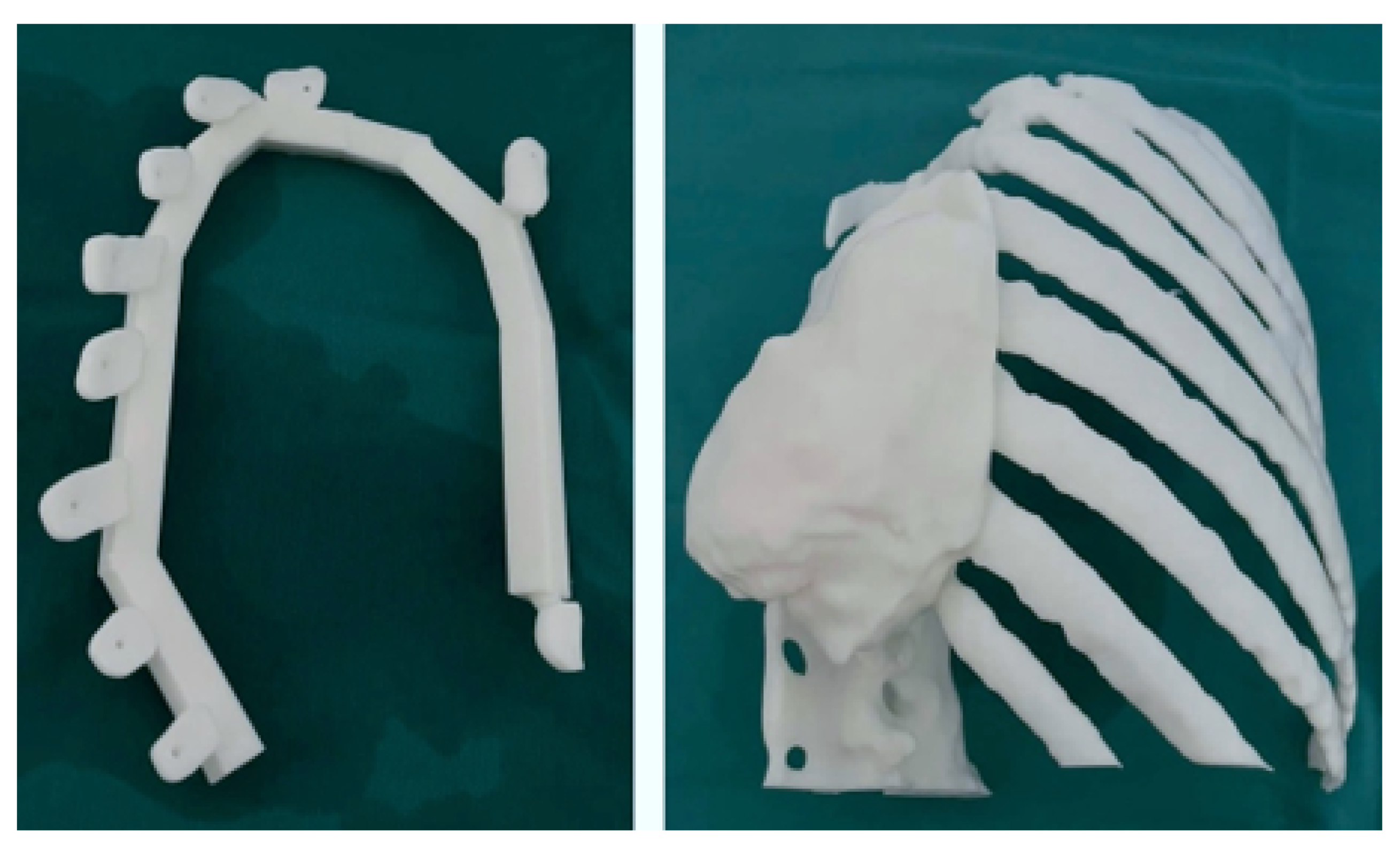

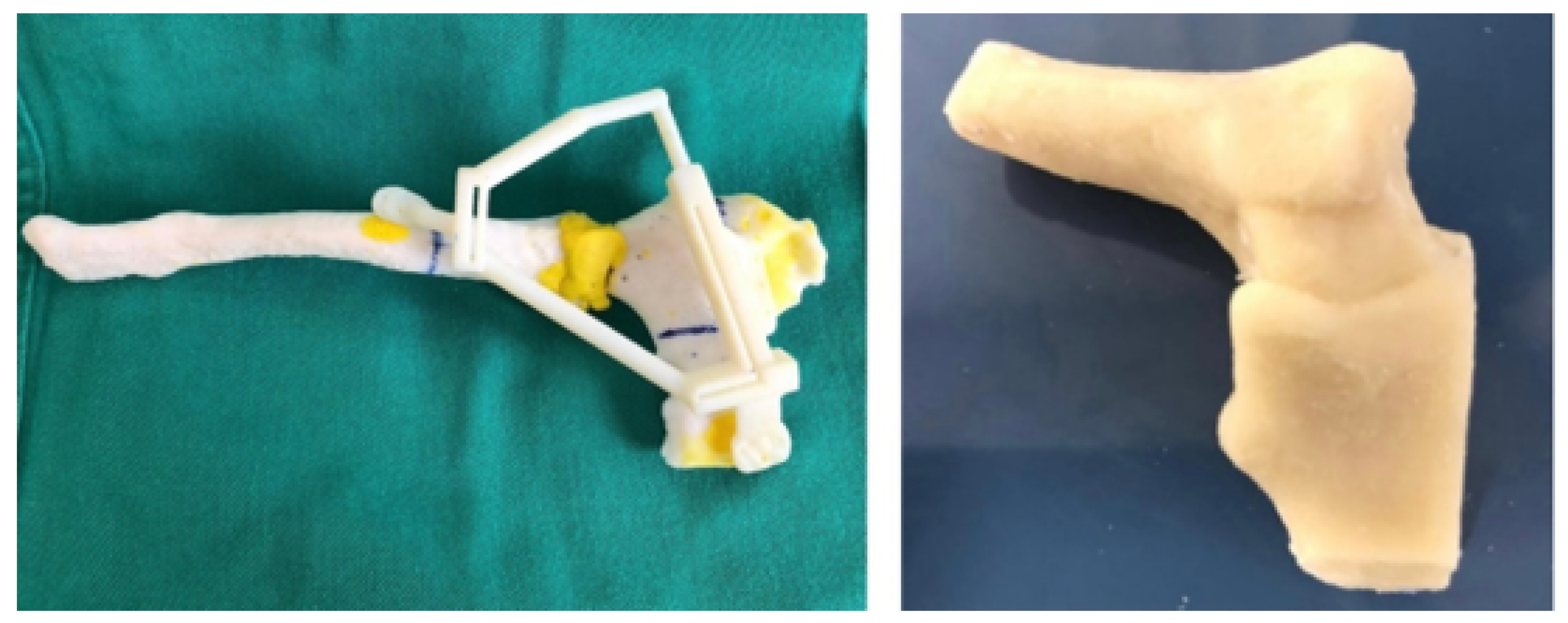

3.3.3. Planning and Printing Anatomical Models

3.3.4. Intraoperative Approach

3.3.5. Post-Operative Results

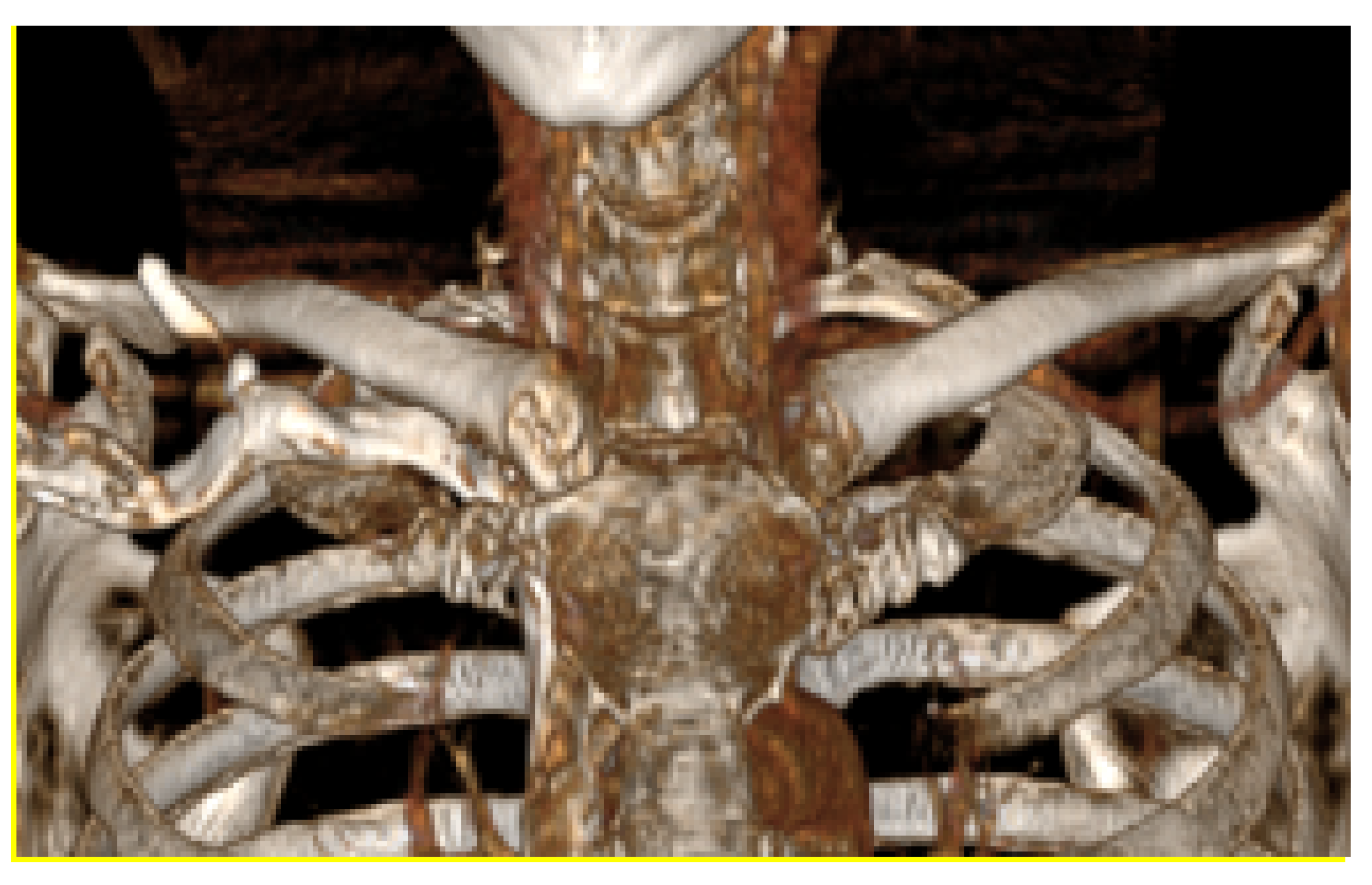

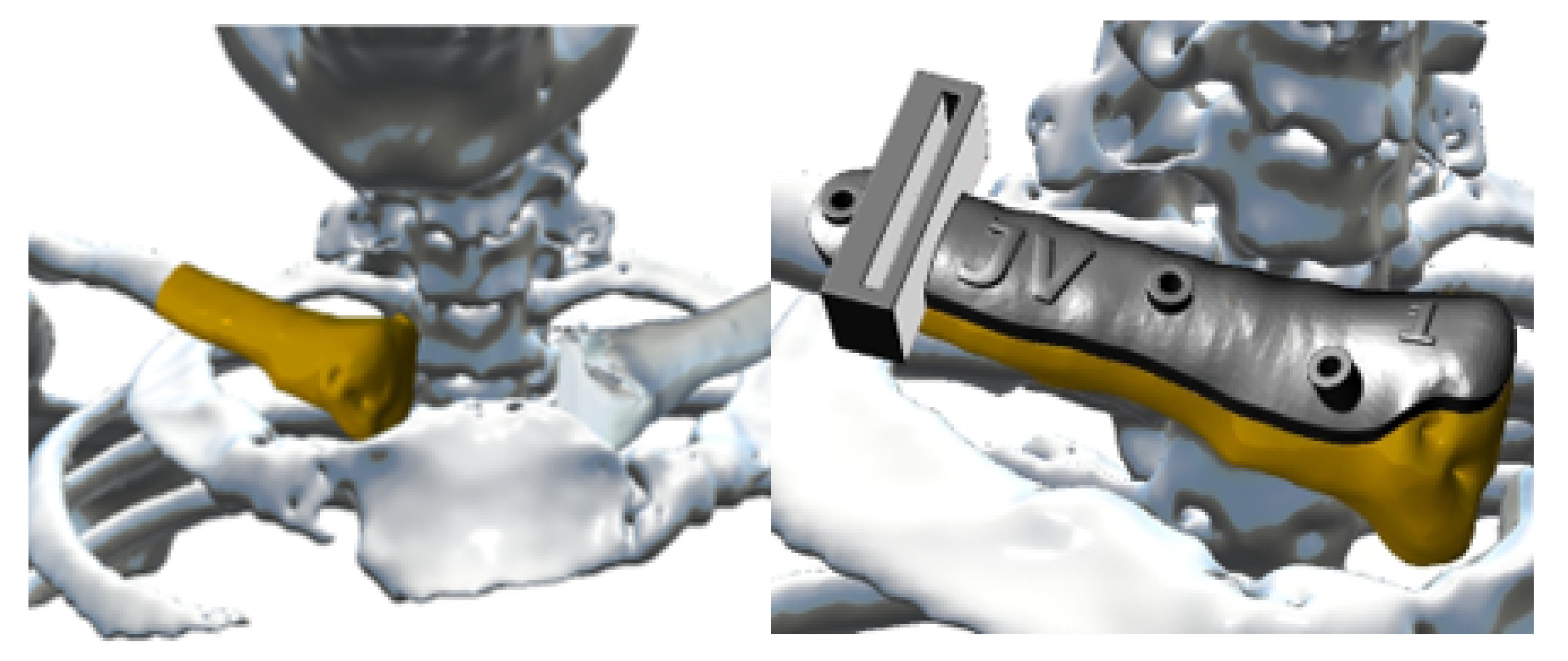

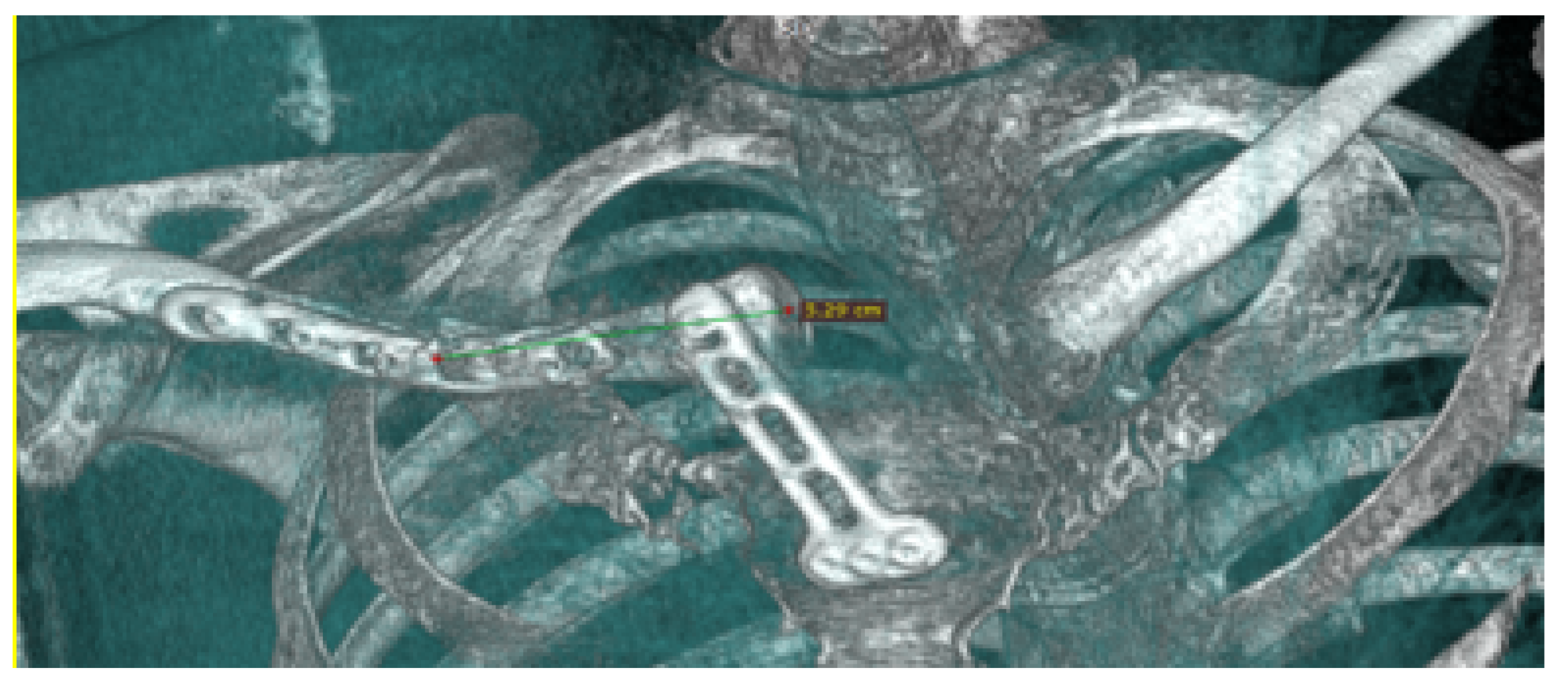

3.4. Case 4: Right Sternoclavicular Joint Tumour

3.4.1. Diagnosis and Analysis

3.4.2. Surgical Planning

3.4.3. Design and Printing of Anatomical Models

3.4.4. Intraoperative Approach

3.4.5. Post-Operative Results

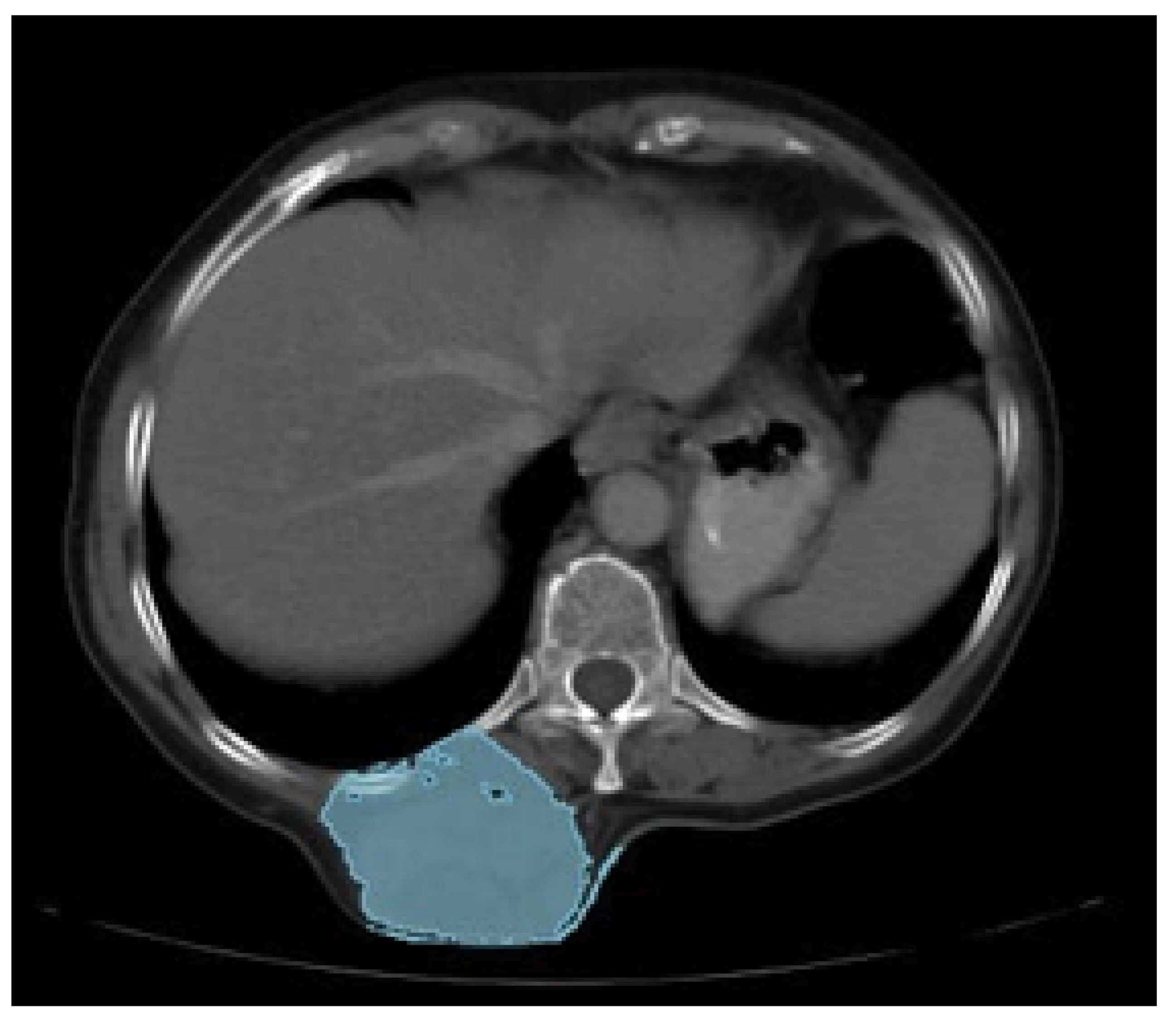

3.5. Case 5: Posterior Chest Tumour

3.5.1. Diagnosis and Analysis

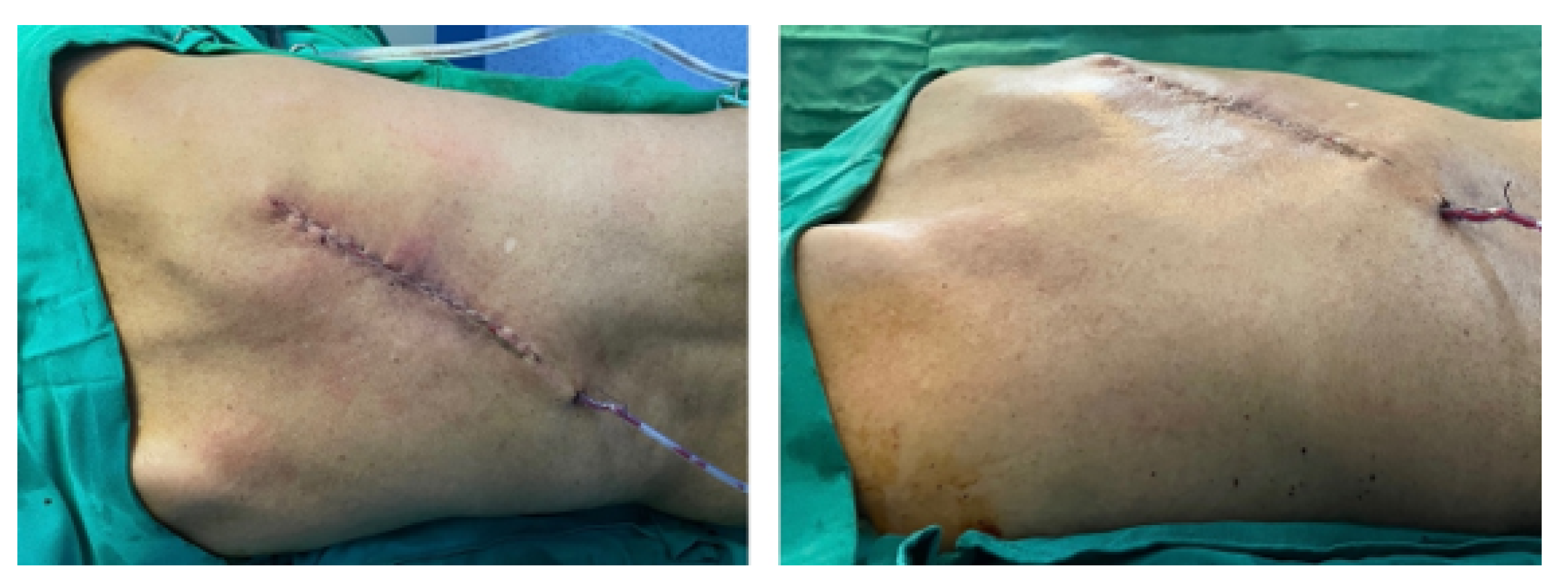

3.5.2. Surgical Planning

3.5.3. Design and Printing of Anatomical Models

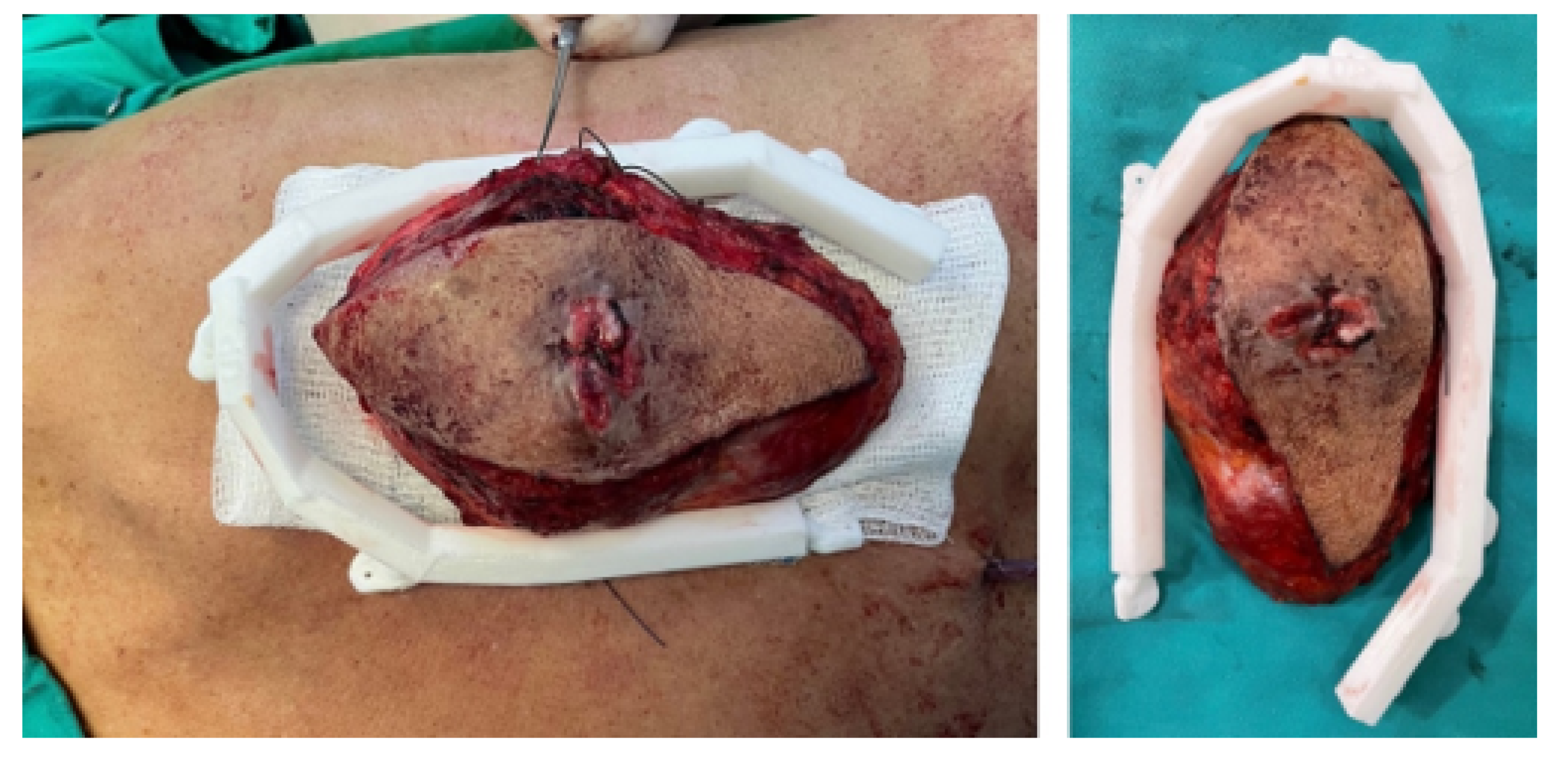

3.5.4. Intraoperative Approach

3.5.5. Post-Operative Results

3.6. Case 6: Right Sternoclavicular Tumour

3.6.1. Diagnosis and Analysis

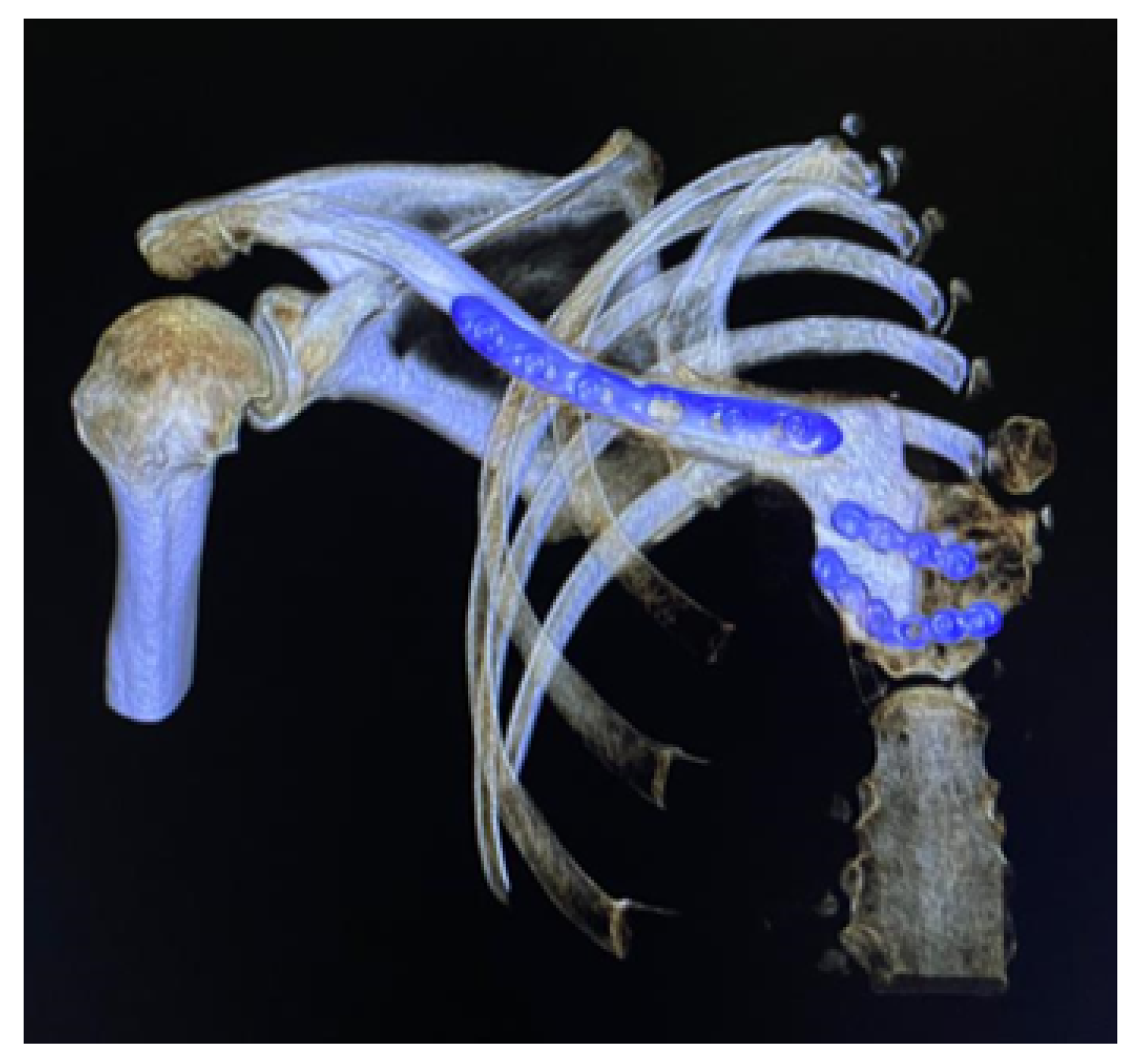

3.6.2. Surgical Planning

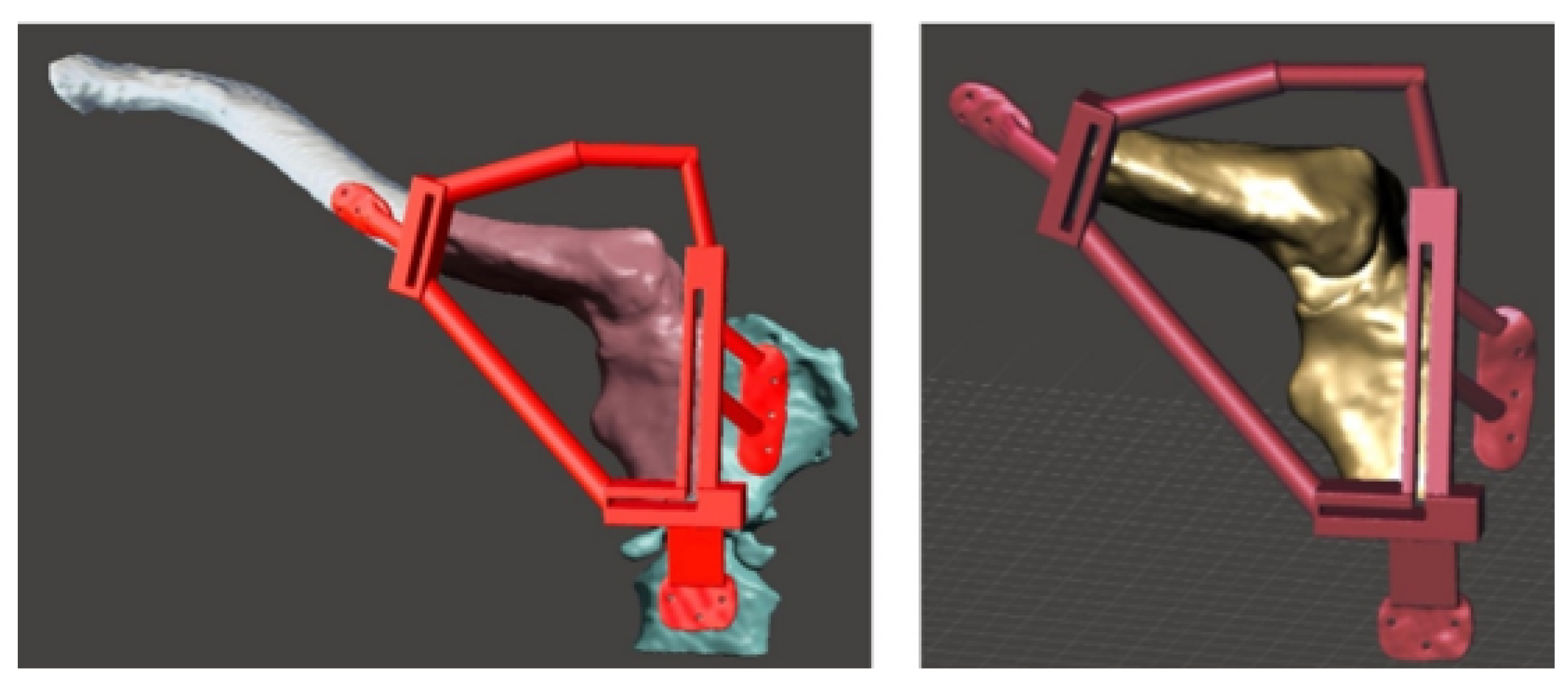

3.6.3. Design and Printing of Anatomical Models

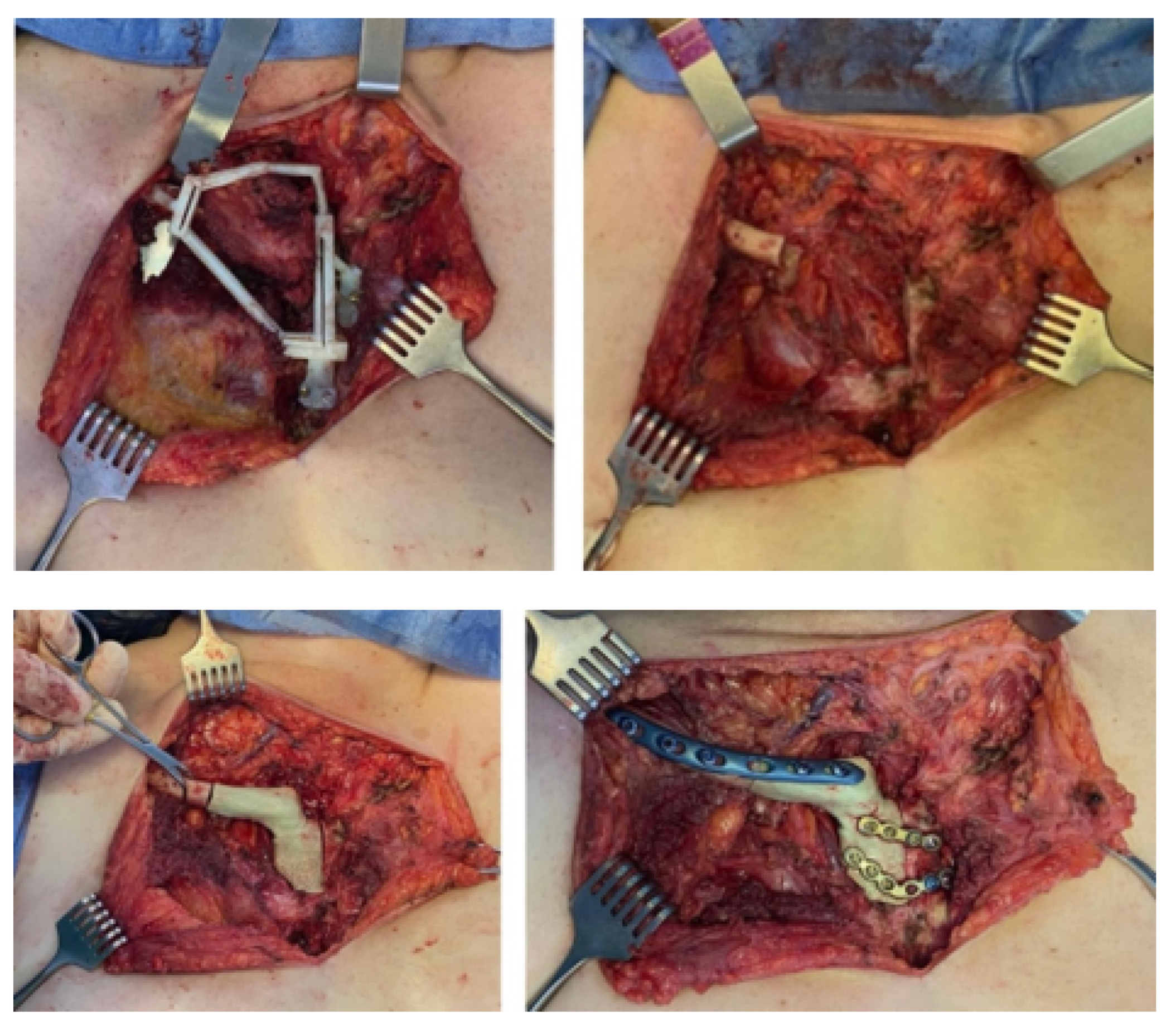

3.6.4. Intraoperative Approach

3.6.5. Post-Operative Results

3.7. Case 7: Metopic Craniosynostosis and Trigonocephaly

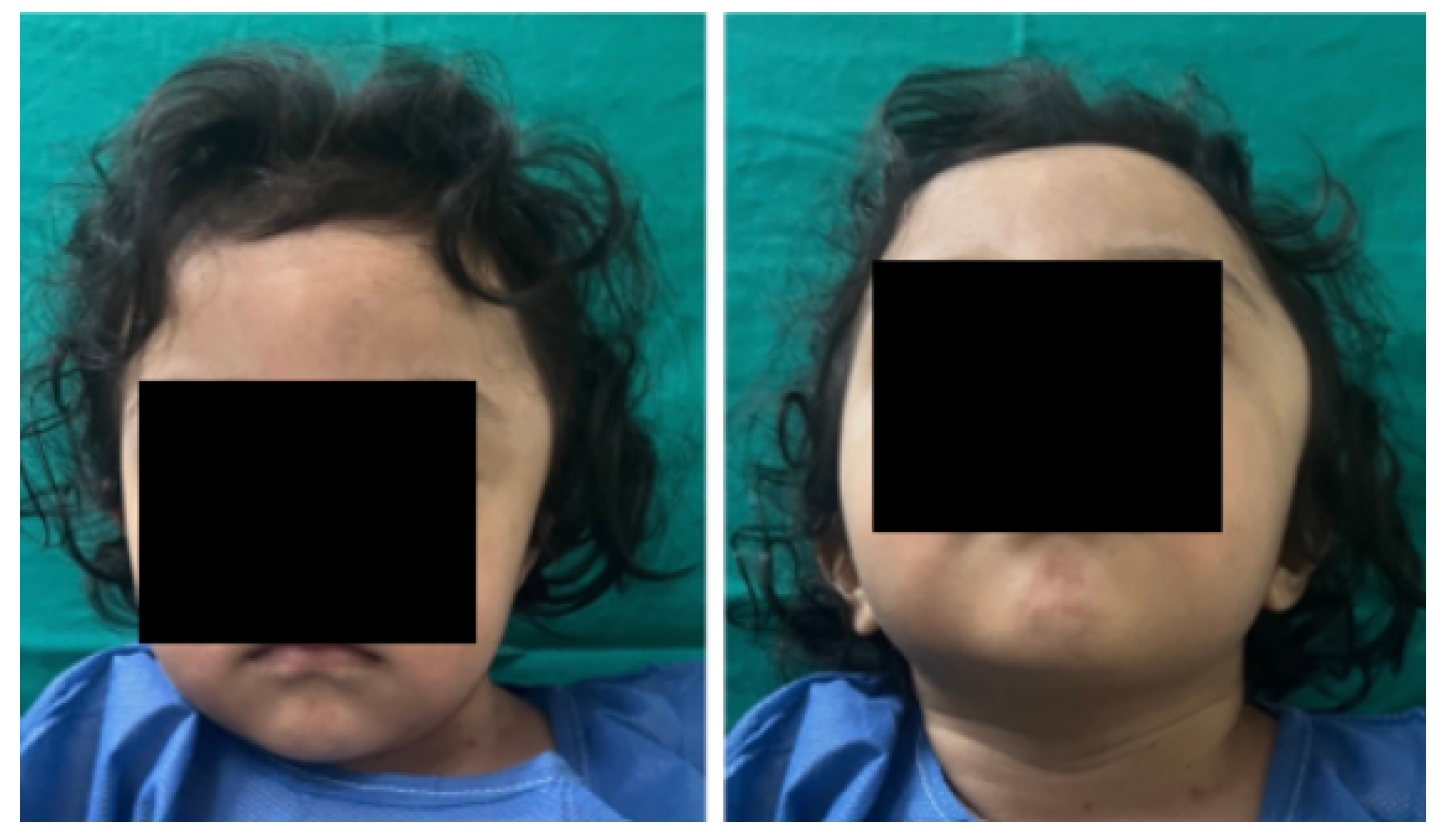

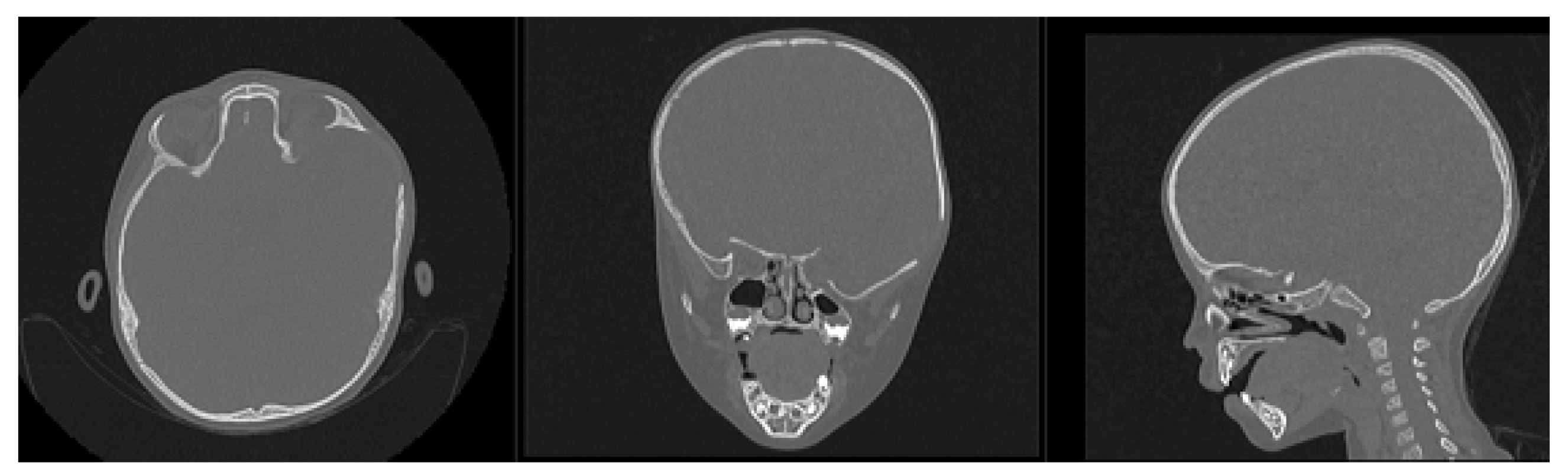

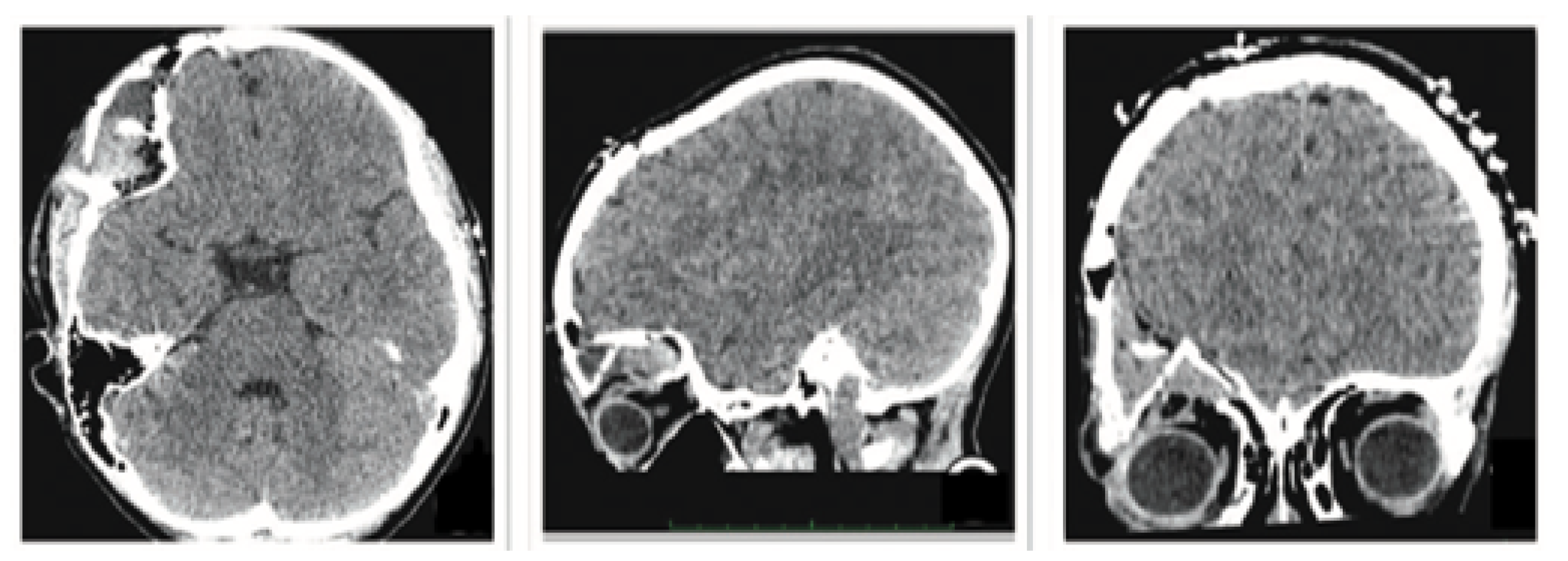

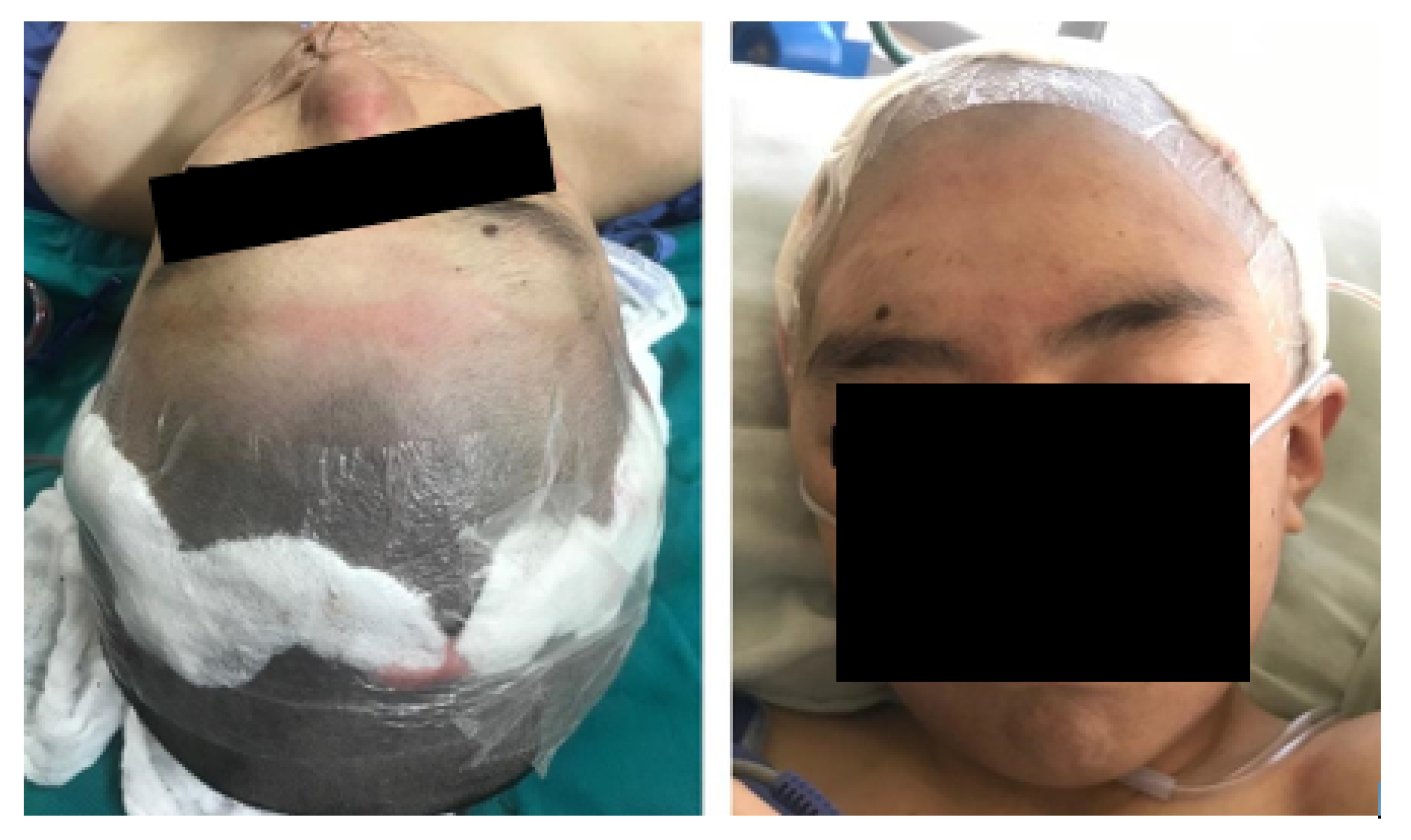

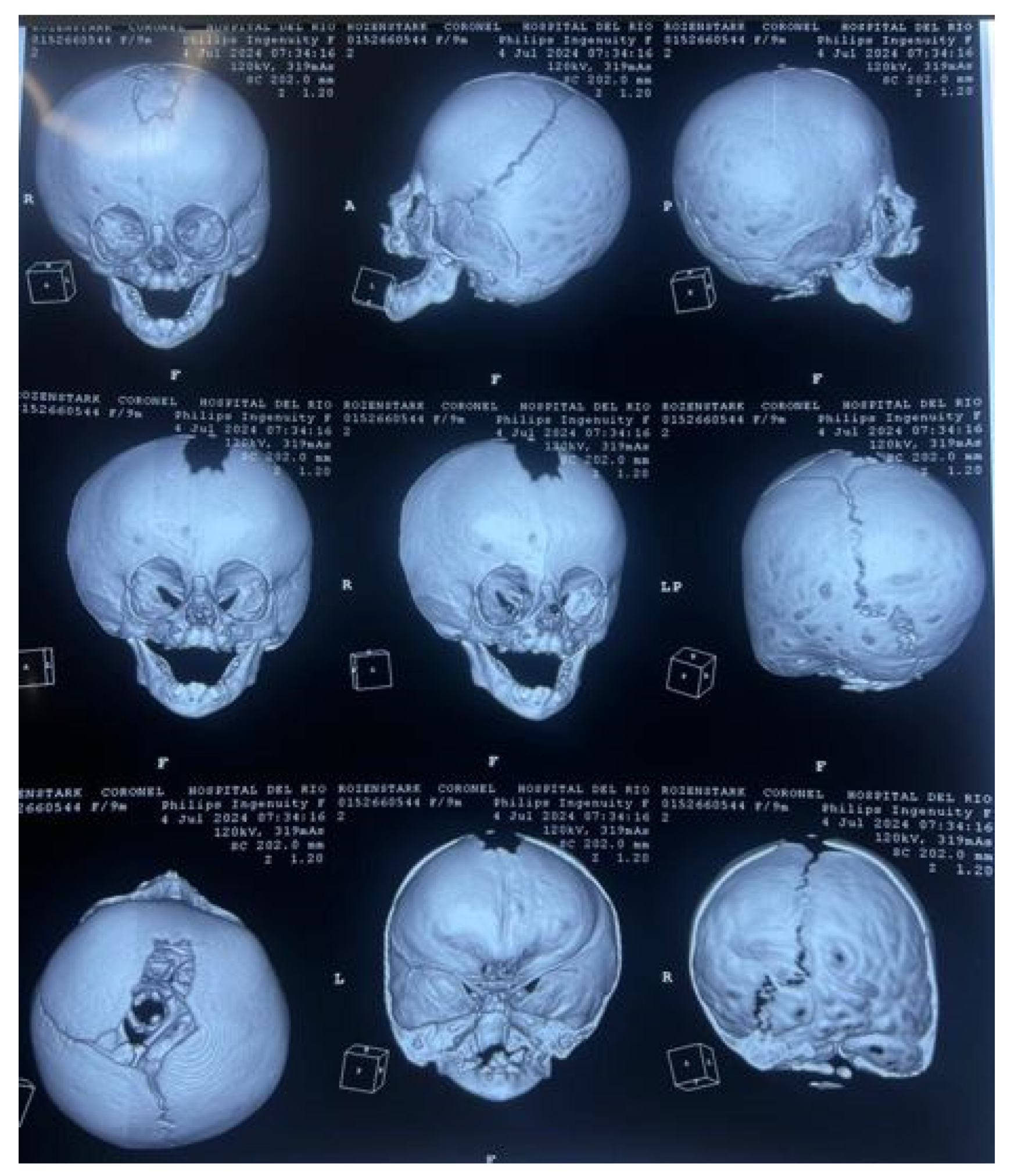

3.7.1. Diagnosis and Analysis

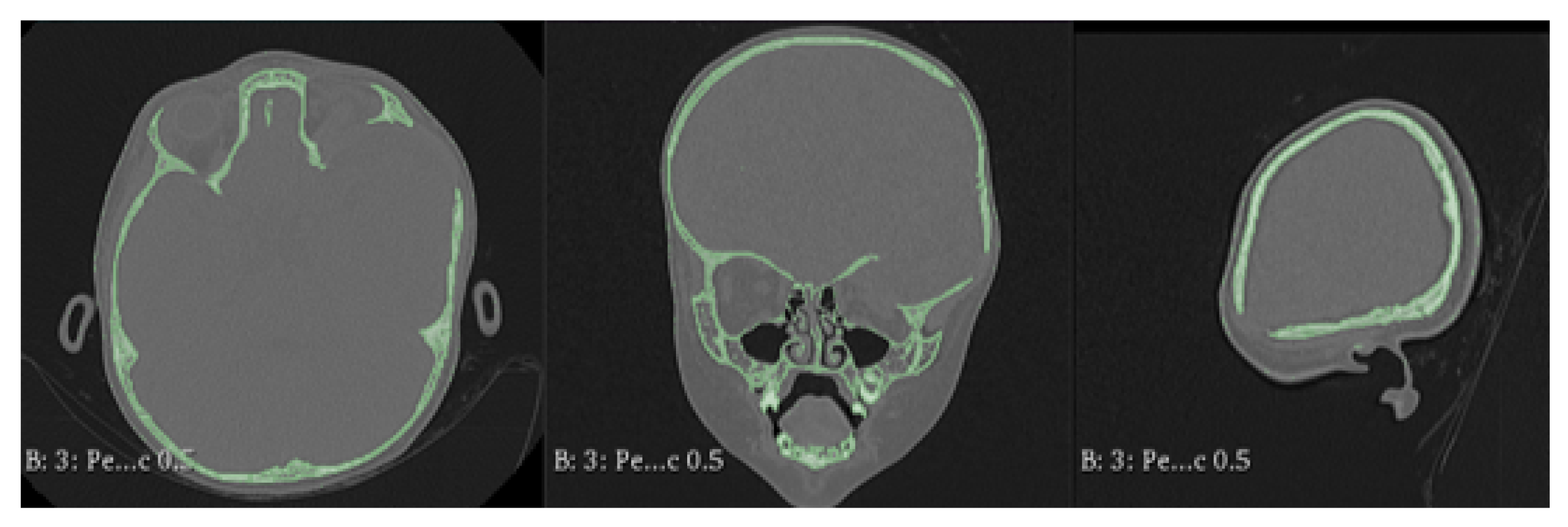

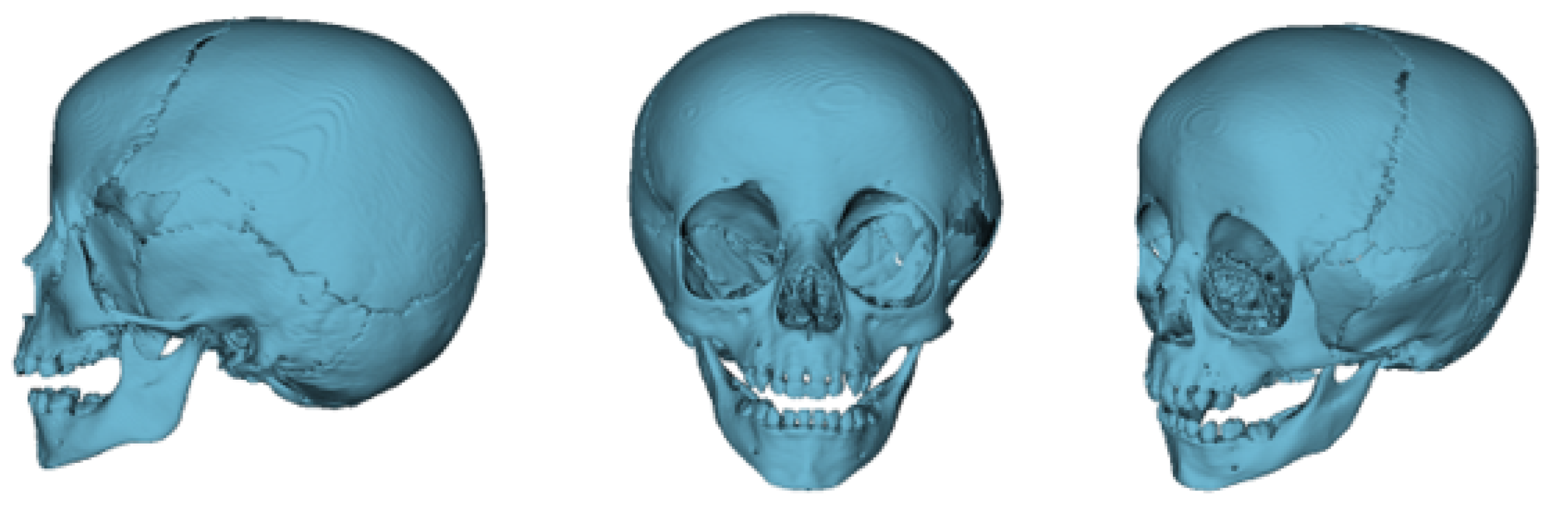

3.7.2. Surgical Planning

3.7.3. Design and Printing of Anatomical Models

3.7.4. Intraoperative Approach

3.7.5. Post-Operative Results

4. Results and Discussion

- The utilisation of scale 1:1 models for simulated surgery and trial-and-error testing with the corresponding anatomical models is pivotal in appropriate surgical approach selection, and the individualised planning of surgery for each patient.

- The additive manufacturing of surgical guides facilitates the execution of precise incisions, with sufficient margins to ensure both oncological efficacy and defect reconstruction.

- The fabrication of custom-made prostheses for bone reconstruction and restoration circumvents the morbidity associated with the donor site and the augmented anaesthetic-surgical time, which is concomitant with freehand manufacturing. The prosthesis is custom-made to fit each patient’s specific defect, offering both anatomical and aesthetic benefits.

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Di Bella, S.; Mineo, R. The Engineer’s Point of View. In 3D Printing in Bone Surgery; Springer, 2022; pp. 39–51.

- Soni, N.; Leo, P. Artificial recreation of human organs by additive manufacturing. Mechanical Engineering in Biomedical Applications: Bio-3D Printing, Biofluid Mechanics, Implant Design, Biomaterials, Computational Biomechanics, Tissue Mechanics 2024, pp. 23–42.

- Glennon, A.; Esposito, L.; Gargiulo, P. Implantable 3D printed devices—technologies and applications. In Handbook of Surgical Planning and 3D Printing; Elsevier, 2023; pp. 383–407.

- Geng, Z.; Bidanda, B. Medical applications of additive manufacturing. Bio-materials and prototyping applications in medicine 2021, pp. 97–110.

- Delgado, J.; Blasco, J.R.; Portoles, L.; Ferris, J.; Hurtos, E.; Atorrasagasti, G. FABIO project: Development of innovative customized medical devices through new biomaterials and additive manufacturing technologies. Annals of DAAAM & Proceedings 2010, pp. 1541–1543.

- Wolf, C.; Juchem, D.; Koster, A.; Pilloy, W. Generation of Customized Bone Implants from CT Scans Using FEA and AM. Materials 2024, 17, 4241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, T.y.; Dedhia, R.; Cervenka, B.; Tollefson, T.T. 3D printing: current use in facial plastic and reconstructive surgery. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery 2017, 25, 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Tack, P.; Victor, J.; Gemmel, P.; Annemans, L. 3D-printing techniques in a medical setting: a systematic literature review. Biomedical engineering online 2016, 15, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-García, L.F.; Kornbluth, Y. Biomedical applications of metal 3D printing. Annual review of biomedical engineering 2021, 23, 307–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larosa, M.; Jardini, A.; Bernardes, L.; Wolf Maciel, M.; Maciel Filho, R.; Zaváglia, C.; Zaváglia, F.; Calderoni, D.; Kharmandayan, P. Custom-built implants manufacture in titanium alloy by Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS). In Proceedings of the High Value Manufacturing: Advanced Research in Virtual and Rapid Prototyping-Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Advanced Research and Rapid Prototyping, VR@ P, Vol. 2014; 2013; pp. 297–301. [Google Scholar]

- Germaini, M.M.; Belhabib, S.; Guessasma, S.; Deterre, R.; Corre, P.; Weiss, P. Additive manufacturing of biomaterials for bone tissue engineering–A critical review of the state of the art and new concepts. Progress in Materials Science 2022, 130, 100963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Saxena, K.K.; Dixit, A.K.; Singh, R.; Mohammed, K.A. Role of additive manufacturing and various reinforcements in MMCs related to biomedical applications. Advances in Materials and Processing Technologies 2024, 10, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.B. Transforming healthcare: a review of additive manufacturing applications in the healthcare sector. Engineering Proceedings 2024, 72, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Vicent, A.; Tambuwala, M.M.; Hassan, S.S.; Barh, D.; Aljabali, A.A.; Birkett, M.; Arjunan, A.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Fused deposition modelling: Current status, methodology, applications and future prospects. Additive manufacturing 2021, 47, 102378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardini, A.; Larosa, M.; Macedo, M.; Bernardes, L.; Lambert, C.; Zavaglia, C.; Maciel Filho, R.; Calderoni, D.; Ghizoni, E.; Kharmandayan, P. Improvement in cranioplasty: advanced prosthesis biomanufacturing. Procedia Cirp 2016, 49, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovan, H.; Jozef, Ž.; Teodor, T.; Jaroslav, M.; Martin, L. Evaluation of custom-made implants using industrial computed tomography. In Proceedings of the The 10th International Conference on Digital Technologies 2014. IEEE; 2014; pp. 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hudák, R.; Živčák, J.; Tóth, T.; Majerník, J.; Lisỳ, M. Usage of industrial computed tomography for evaluation of custom-made implants. In Applications of Computational Intelligence in Biomedical Technology; Springer, 2015; pp. 29–45.

- Rontescu, C.; Amza, C.G.; Bogatu, A.M.; Cicic, D.T.; Anania, F.D.; Burlacu, A. Reconditioning by welding of prosthesis obtained through additive manufacturing. Metals 2022, 12, 1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardini, A.L.; Larosa, M.A.; de Carvalho Zavaglia, C.A.; Bernardes, L.F.; Lambert, C.S.; Kharmandayan, P.; Calderoni, D.; Maciel Filho, R. Customised titanium implant fabricated in additive manufacturing for craniomaxillofacial surgery: This paper discusses the design and fabrication of a metallic implant for the reconstruction of a large cranial defect. Virtual and physical prototyping 2014, 9, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsch, M. Laser additive manufacturing of customized prosthetics and implants for biomedical applications. In Laser additive manufacturing; Elsevier, 2017; pp. 399–420.

- Abouel Nasr, E.; Al-Ahmari, A.M.; Moiduddin, K.; Al Kindi, M.; Kamrani, A.K. A digital design methodology for surgical planning and fabrication of customized mandible implants. Rapid Prototyping Journal 2017, 23, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardini, A.L.; Larosa, M.A.; Maciel Filho, R.; de Carvalho Zavaglia, C.A.; Bernardes, L.F.; Lambert, C.S.; Calderoni, D.R.; Kharmandayan, P. Cranial reconstruction: 3D biomodel and custom-built implant created using additive manufacturing. Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 2014, 42, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M. Role of CT and MRI in the design and development of orthopaedic model using additive manufacturing. Journal of clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma 2018, 9, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, C.J.A.; Setti, J.A.P. 3d printing in orthopedic surgery. In Personalized Orthopedics: Contributions and Applications of Biomedical Engineering; Springer, 2022; pp. 375–409.

- Wong, K.C. 3D-printed patient-specific applications in orthopedics. Orthopedic research and reviews 2016, pp. 57–66.

- Almeida, H.A.; Vasco, J.; Correia, M.; Ruben, R. Layer Thickness Evaluation Between Medical Imaging and Additive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the VipIMAGE 2019: Proceedings of the VII ECCOMAS Thematic Conference on Computational Vision and Medical Image Processing, October 16–18, 2019, Porto, Portugal. Springer, 2019, pp. 693–701.

- Peel, S.; Bhatia, S.; Eggbeer, D.; Morris, D.S.; Hayhurst, C. Evolution of design considerations in complex craniofacial reconstruction using patient-specific implants. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part H: Journal of Engineering in Medicine 2017, 231, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscaccianti, V.; Fragnaud, H.; Hascoët, J.Y.; Crenn, V.; Vidal, L. Digital chain for pelvic tumor resection with 3D-printed surgical cutting guides. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2022, 10, 991676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, D.; Laptoiu, D.; Marinescu, R.; Botezatu, I. Design and 3D printing customized guides for orthopaedic surgery–lessons learned. Rapid Prototyping Journal 2018, 24, 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.; Ventura, F.; Gaspar, M.; Fontes, R.; Mateus, A. Customized implant development for maxillo-mandibular reconstruction. In Virtual and Rapid Manufacturing; CRC Press, 2007; pp. 159–166.

- Cholkar, A.; Kinahan, D.J.; Brabazon, D. Topology and FEA modeling and optimization of a patient-specific zygoma implant. DORAS: DCU Research Repository 2021.

- Larosa, M.A.; Jardini, A.L.; Zavaglia, C.A.d.C.; Kharmandayan, P.; Calderoni, D.R.; Maciel Filho, R. Microstructural and mechanical characterization of a custom-built implant manufactured in titanium alloy by direct metal laser sintering. Advances in Mechanical Engineering 2014, 6, 945819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, S.H.; Moiduddin, K.; Abdo, B.M.; Sayeed, A.; Alkhalefah, H. Modelling and evaluation of meshed implant for cranial reconstruction. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2022, pp. 1–19.

- Fedorov, A.; Beichel, R.; Kalpathy-Cramer, J.; Finet, J.; Fillion-Robin, J.C.; Pujol, S.; Bauer, C.; Jennings, D.; Fennessy, F.; Sonka, M.; et al. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magnetic resonance imaging 2012, 30, 1323–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moncayo-Matute, F.P.; Pena-Tapia, P.G.; Vázquez-Silva, E.; Torres-Jara, P.B.; Abad-Farfán, G.; Moya-Loaiza, D.P.; Andrade-Galarza, A.F. Description and application of a comprehensive methodology for custom implant design and surgical planning. Interdisciplinary Neurosurgery 2022, 29, 101585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, C. Impression 3D de dispositifs médicaux utilisés en chirurgie: quelles recommandations pour l’élaboration d’un modèle d’évaluation médico-économique? PhD thesis, Université Paris-Saclay, 2020.

- Sazzad, F.; Ramanathan, K.; Moideen, I.S.; Gohary, A.E.; Stevens, J.C.; Kofidis, T. A systematic review of individualized heart surgery with a personalized prosthesis. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2023, 13, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moncayo-Matute, F.P.; Peña-Tapia, P.G.; Vázquez-Silva, E.; Torres-Jara, P.B.; Moya-Loaiza, D.P.; Abad-Farfán, G. Surgical planning for the removal of cranial espheno-orbitary meningioma through the use of personalized polymeric prototypes obtained with an additive manufacturing technique. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Electrical, Computer, Communications and Mechatronics Engineering (ICECCME). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–7.

- Daniels, A.H.; Singh, M.; Knebel, A.; Thomson, C.; Kuharski, M.J.; De Varona, A.; Nassar, J.E.; Farias, M.J.; Diebo, B.G. Preoperative Optimization Strategies in Elective Spine Surgery. JBJS reviews 2025, 13, e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.H.; Shim, J.H.; Lee, H.; Kim, B.Y.; Lee, J.S.; Jung, J.W.; Yun, W.S.; Baek, C.H.; Rhie, J.W.; Cho, D.W. Reconstruction of complex maxillary defects using patient-specific 3D-printed biodegradable scaffolds. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery–Global Open 2018, 6, e1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kämmerer, P.W.; Müller, D.; Linz, F.; Peron, P.F.; Pabst, A. Patient-specific 3D-printed cutting guides for high oblique sagittal osteotomy—an innovative surgical technique for nerve preservation in orthognathic surgery. Journal of Surgical Case Reports 2021, 2021, rjab345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Rickey, D.; Hayakawa, T.; Pathak, A.; Dubey, A.; Sasaki, D.; Harris, C.; Buchel, E.; Alpuche, J.; McCurdy, B.M.; et al. Utilization of 3D Printing in Surgical Oncology: An Institutional Review of Cost and Time Effectiveness. Cureus Journal of Medical Science 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Broeck, J.; Wirix-Speetjens, R.; Vander Sloten, J. Preoperative analysis of the stability of fit of a patient-specific surgical guide. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering 2015, 18, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiti, G.; Dobbe, J.G.; Strijkers, G.J.; Strackee, S.D.; Streekstra, G.J. Positioning error of custom 3D-printed surgical guides for the radius: influence of fitting location and guide design. International journal of computer assisted radiology and surgery 2018, 13, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics and manufacturing parameters | Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) |

|---|---|

| Company and model | Creality CR-X Pro (2019 Updated) |

| Maximum build envelope | |

| Nozzle diameter | |

| Positioning resolution | |

| Selected layer thickness | |

| Printed filament line width |

| Characteristics | PLA (FDM) | PMMA | Resin PolyJet |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer | Thermoplastic | Thermoplastic | Photopolymer |

| Manufacturer | Creality HP | Veracril, New Stetic S.A. | Stratasys |

| Commercial | HP-PLA | PMMA | MED610 |

| Color | White (Bone) | Transparent | Transparent |

| Density | |||

| Tensile strength | |||

| Print/molding temperature | |||

| Filament diameter | - | - | |

| Printed diameter | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).