Submitted:

14 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. Dietary Assessment

2.3. Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

2.4. Gut Microbiota Profiling

2.5. Bioinformatic Processing

2.6. Detection of Blastocystis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.8. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Dietary Quality and Blastocystis Status by Cohort

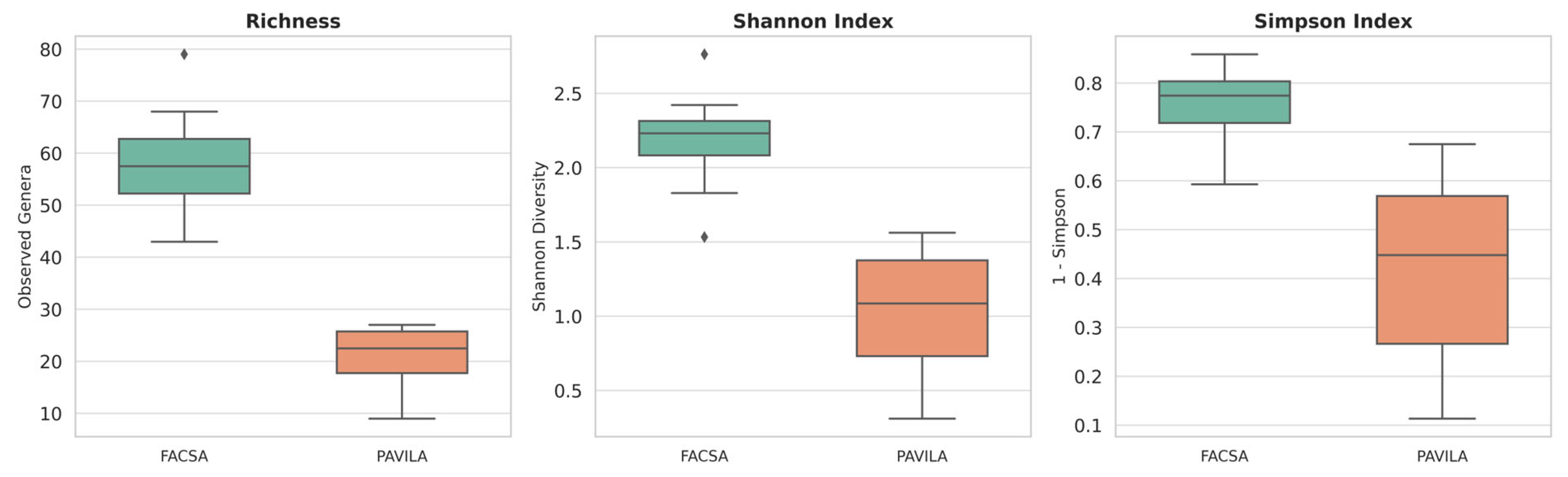

3.2. Alpha Diversity Analysis Between FACSA and PAVILA Cohorts

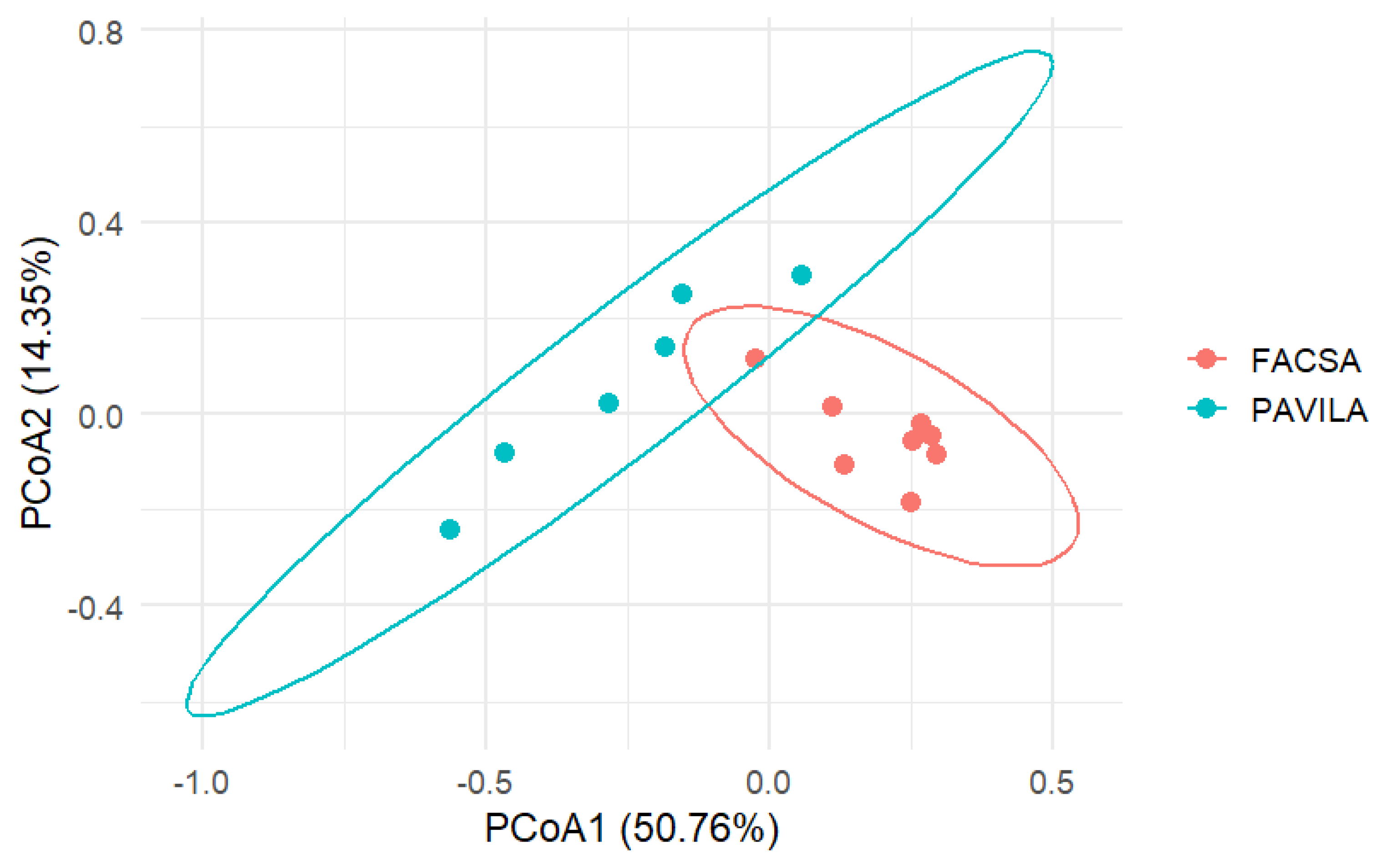

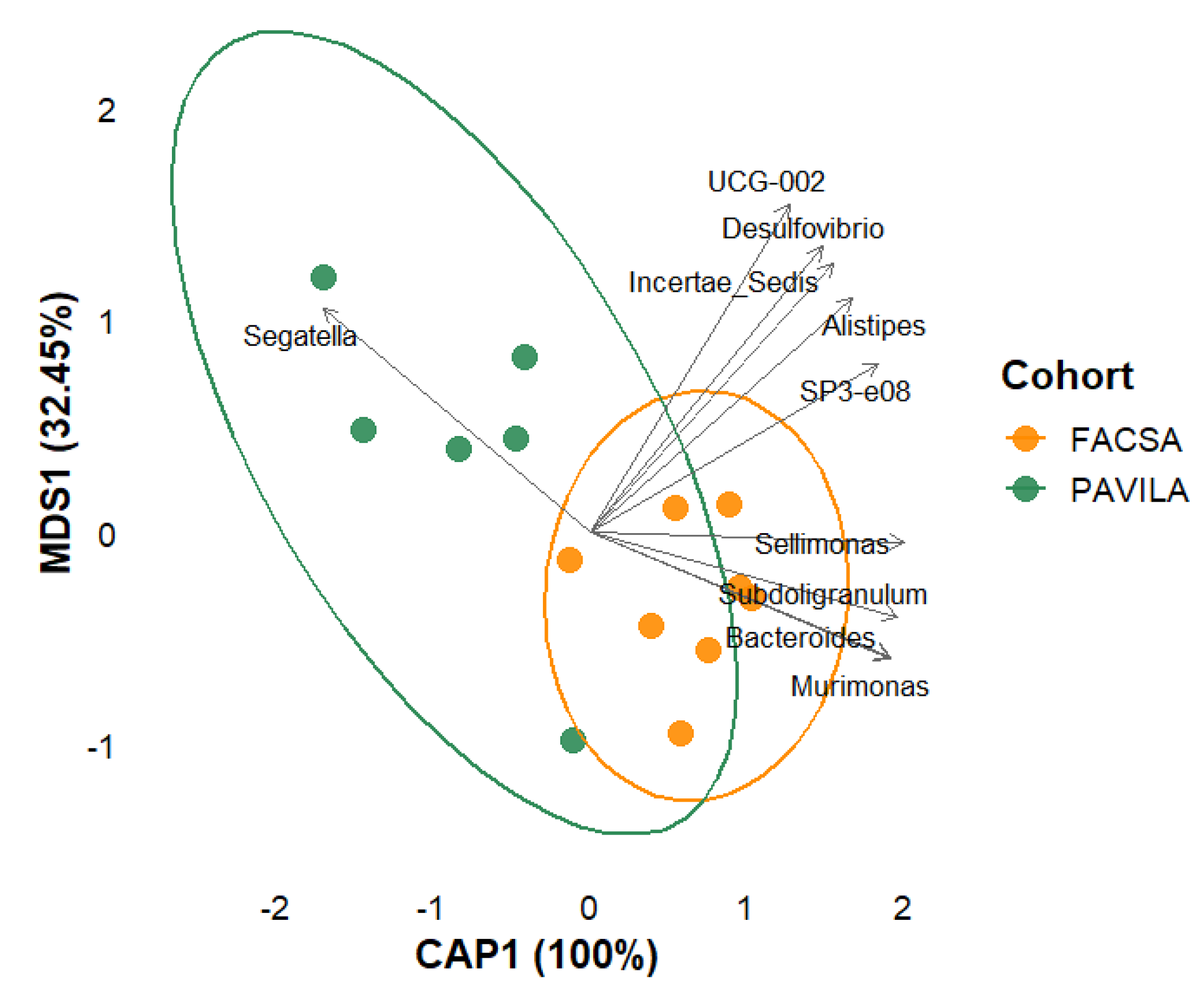

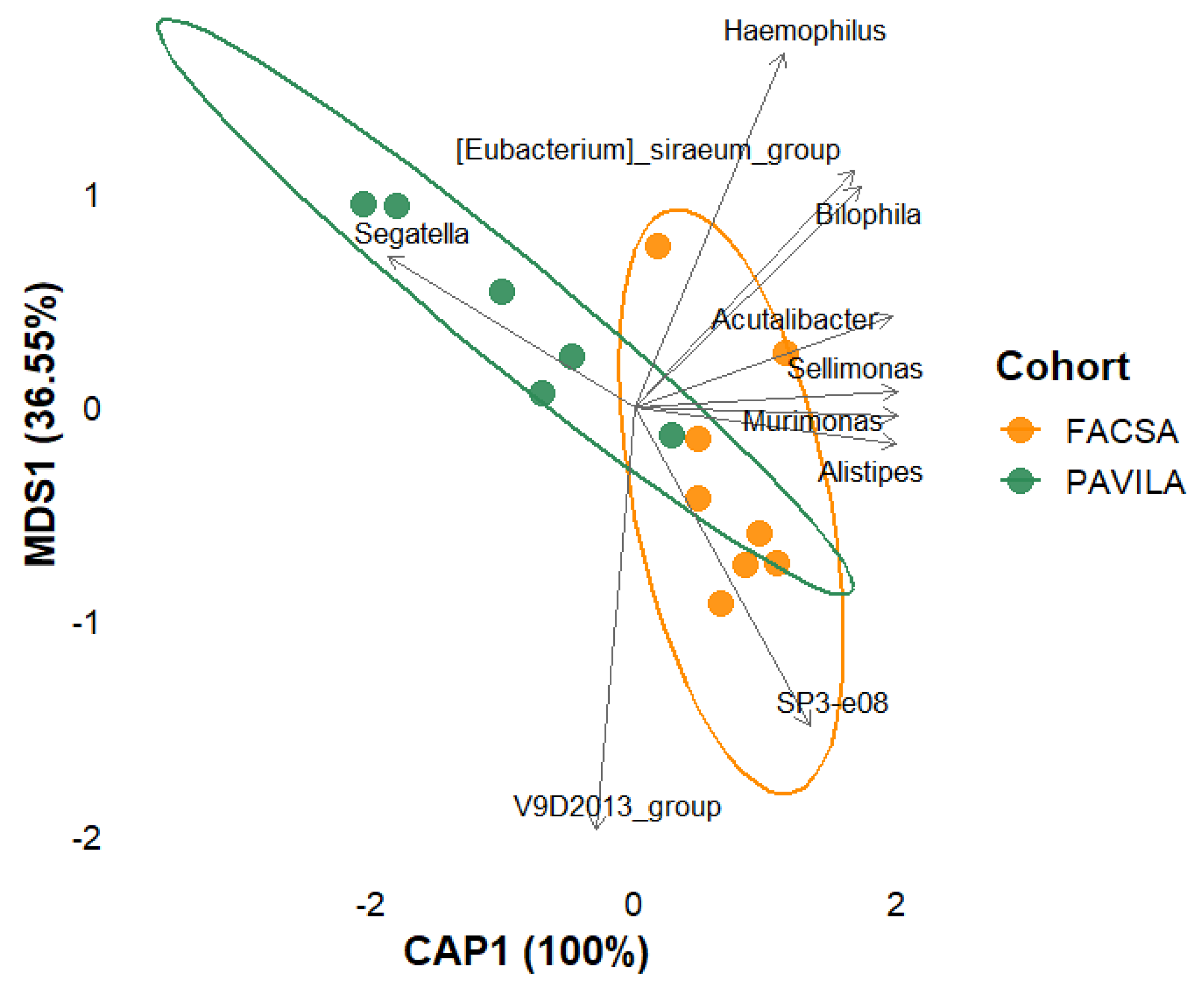

3.3. Beta Diversity Analysis

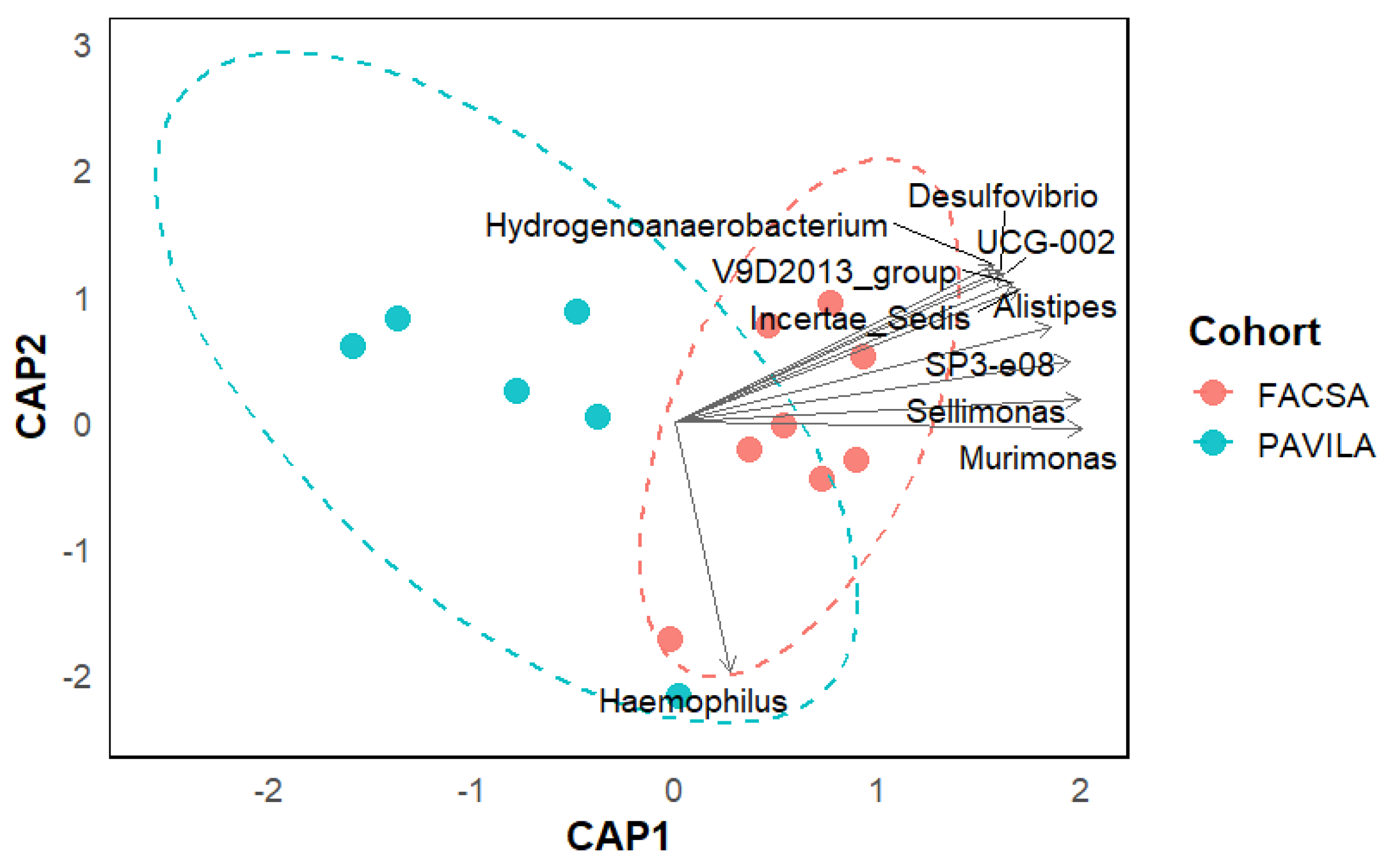

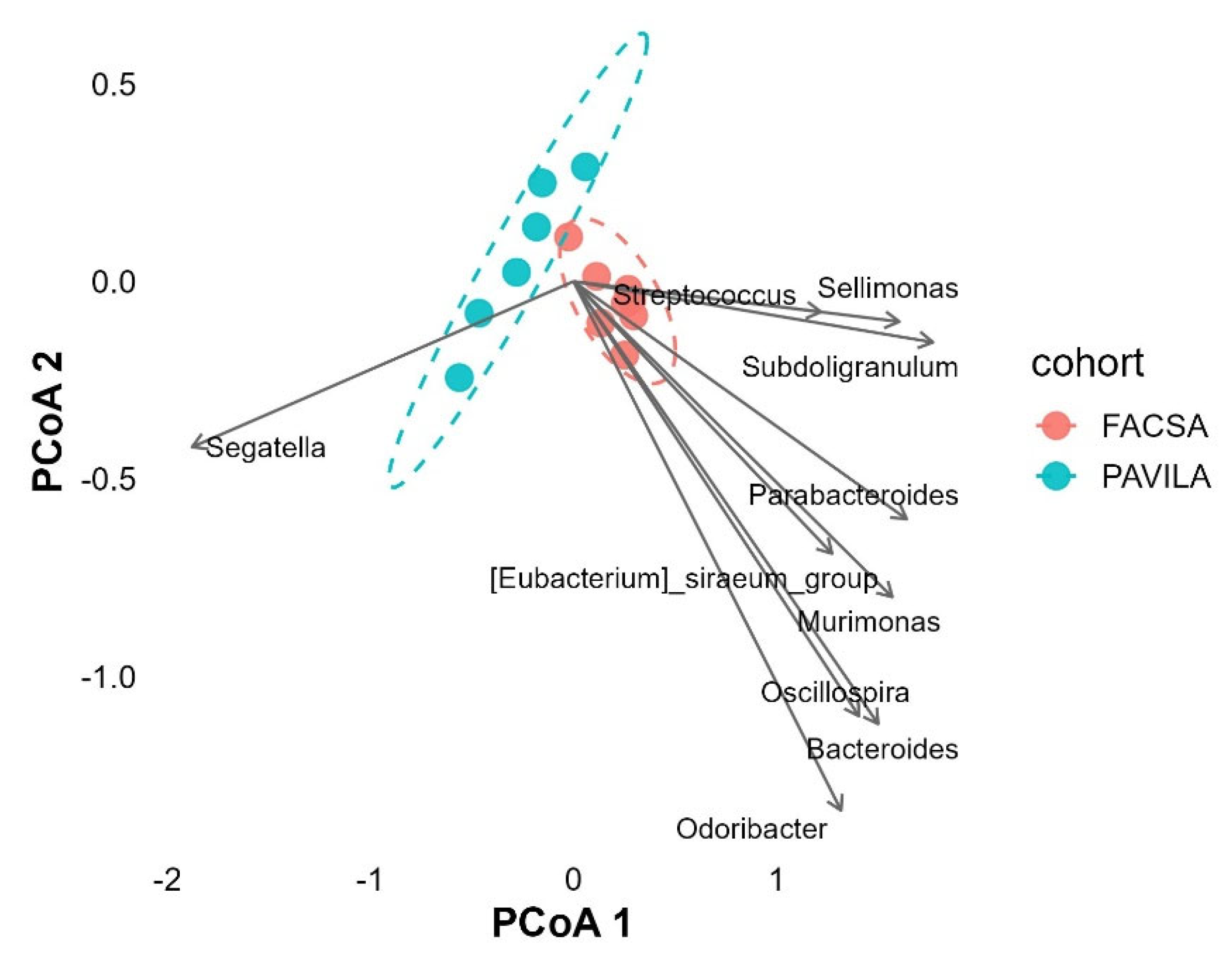

3.4. PCoA Biplot with Genus-Level Arrows

3.5. Diet–Microbiota Associations within Colonised Individuals

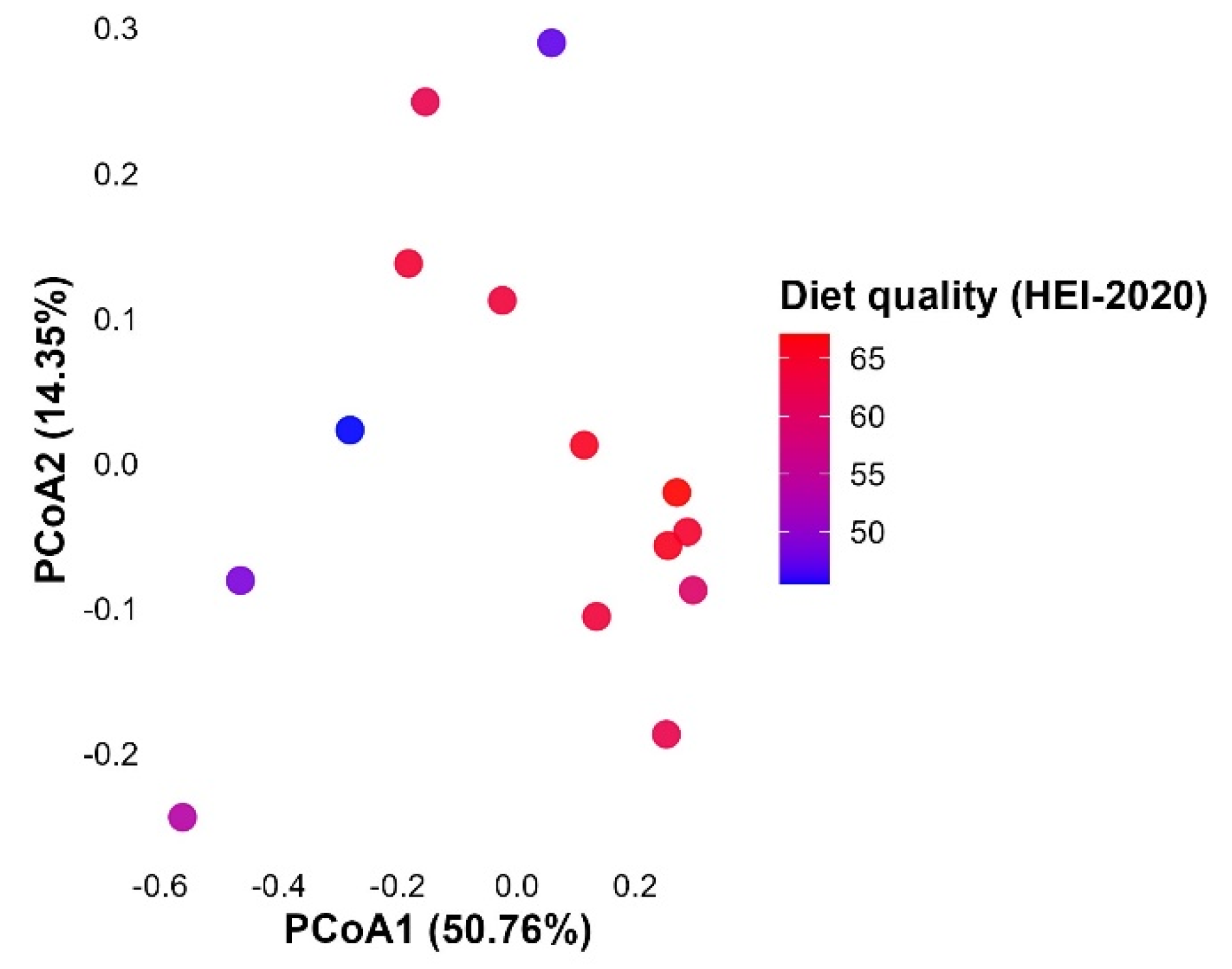

3.5.1. Beta Diversity and Diet Quality Score in Blastocystis-Colonised Individuals

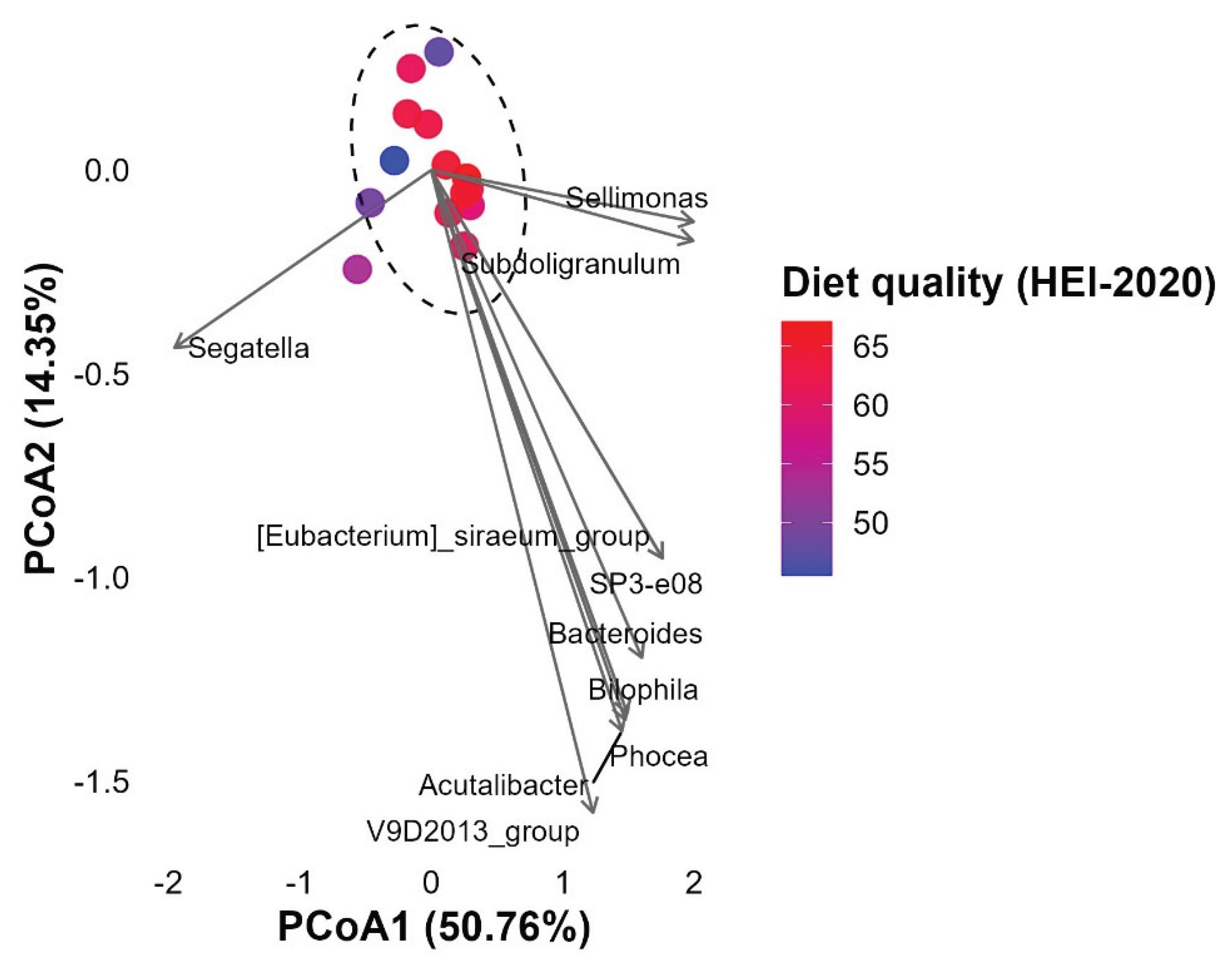

3.5.2. Microbial Composition Projected onto Dietary Quality Gradient

3.5.2. PERMANOVA Results by Dietary Component

3.5.3. db-RDA Analysis: Protein and Vegetable Intake

3.5.4. Multivariate analysis of the combined effect of protein and vegetable intake on gut microbiota composition in individuals colonised by Blastocystis

| Term | Df | Sum of Squares | R² | F | p-value |

| Model (Protein + Vegetables) | 2 | 0.66195 | 0.31268 | 2.5021 | 0.025 |

| Residual | 11 | 1.45506 | 0.68732 | ||

| Total | 13 | 2.11701 | 1.0 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PERMANOVA | Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance |

| HEI-2020 | Healthy Eating Index-2020 |

| 16S rRNA | 16S ribosomal Ribonucleic Acid |

| db-RDA | Distance-based Redundancy Analysis |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinates Analysis |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| SES | Socioeconomic Status |

| FFQ | Food Frequency Questionnaire |

| FINUT | Ibero-American Nutrition Foundation |

| BEDCA | Spanish Food Composition Database |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| IPAQ | International Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| MET | Metabolic Equivalent of Task |

| E.Z.N.A. | E.Z.N.A. stands for 'Easy Nucleic Acid', a brand of nucleic acid extraction kits |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| Bio-Tek, Inc | Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc. (a laboratory instrumentation company) |

| FastQC | Fast Quality Control (a tool for quality checking high throughput sequence data) |

| DADA2 | Divisive Amplicon Denoising Algorithm 2 |

| QIIME2 | Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology 2 |

| ASVs | Amplicon Sequence Variants |

| VSEARCH | Vectorized Search (open-source tool for metagenomics) |

| SILVA | SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project |

| MAFFT | Multiple Alignment using Fast Fourier Transform |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| IDT | Integrated DNA Technologies |

| Qiagen | Qiagen (biotech company for DNA/RNA extraction and analysis kits) |

| RT-PCR | Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| RNase | Ribonuclease |

| DNase | Deoxyribonuclease |

| CEI-FAMEN | Comité de Ética en Investigación de la Facultad de Medicina y Nutrición (ESP) |

| envfit | Environmental Fitting Function (in R vegan package) |

| CAP1 | Canonical Axis 1 (used in constrained ordination analyses) |

| MDS1 | Multidimensional Scaling Dimension 1 |

| F | F-statistic |

| p | p-value |

| Df | Degrees of Freedom |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| ST1 | Subtype 1 (Blastocystis subtype) |

| ST4 | Subtype 4 (Blastocystis subtype) |

| ST7 | Subtype 7 (Blastocystis subtype) |

References

- Illiano, P.; Brambilla, R.; Parolini, C. The Mutual Interplay of Gut Microbiota, Diet and Human Disease. FEBS Journal 2020, 287, 833–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemzer, B. V.; Al-Taher, F.; Kalita, D.; Yashin, A.Y.; Yashin, Y.I. Health-Improving Effects of Polyphenols on the Human Intestinal Microbiota: A Review. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severino, A.; Tohumcu, E.; Tamai, L.; Dargenio, P.; Porcari, S.; Rondinella, D.; Venturini, I.; Maida, M.; Gasbarrini, A.; Cammarota, G.; et al. The Microbiome-Driven Impact of Western Diet in the Development of Noncommunicable Chronic Disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2024, 72, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, K.; Wu, Z.X.; Chen, X.Y.; Wang, J.Q.; Zhang, D.; Xiao, C.; Zhu, D.; Koya, J.B.; Wei, L.; Li, J.; et al. Microbiota in Health and Diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2022, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jandhyala, S.M.; Talukdar, R.; Subramanyam, C.; Vuyyuru, H.; Sasikala, M.; Reddy, D.N. Role of the Normal Gut Microbiota. World J Gastroenterol 2015, 21, 8836–8847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, N.; Yang, H. Factors Affecting the Composition of the Gut Microbiota, and Its Modulation. PeerJ 2019, 2019, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, P.; Ishimoto, T.; Fu, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. The Gut Microbiota in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zou, R.; Guo, M.; Zheng, H. Characteristics of Gut Microbiota in People with Obesity. PLoS One 2021, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riggen-Bueno, V.; Del Toro-Arreola, S.; Baltazar-Díaz, T.A.; Vega-Magaña, A.N.; Peña-Rodríguez, M.; Castaño-Jiménez, P.A.; Sánchez-Orozco, L.V.; Vera-Cruz, J.M.; Bueno-Topete, M.R. Intestinal Dysbiosis in Subjects with Obesity from Western Mexico and Its Association with a Proinflammatory Profile and Disturbances of Folate (B9) and Carbohydrate Metabolism. Metabolites 2024, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piperni, E.; Nguyen, L.H.; Manghi, P.; Kim, H.; Pasolli, E.; Andreu-Sánchez, S.; Arrè, A.; Bermingham, K.M.; Blanco-Míguez, A.; Manara, S.; et al. Intestinal Blastocystis Is Linked to Healthier Diets and More Favorable Cardiometabolic Outcomes in 56,989 Individuals from 32 Countries. Cell 2024, 187, 4554–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aykur, M.; Malatyalı, E.; Demirel, F.; Cömert-Koçak, B.; Gentekaki, E.; Tsaousis, A.D.; Dogruman-Al, F. Blastocystis: A Mysterious Member of the Gut Microbiome. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaled, S.; Gantois, N.; Ly, A.T.; Senghor, S.; Even, G.; Dautel, E.; Dejager, R.; Sawant, M.; Baydoun, M.; Benamrouz-Vanneste, S.; et al. Prevalence and Subtype Distribution of Blastocystis Sp. In Senegalese School Children. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemati, S.; Zali, M.R.; Johnson, P.; Mirjalali, H.; Karanis, P. Molecular Prevalence and Subtype Distribution of Blastocystis Sp. In Asia and in Australia. J Water Health 2021, 19, 687–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marangi, M.; Boughattas, S.; De Nittis, R.; Pisanelli, D.; delli Carri, V.; Lipsi, M.R.; La Bella, G.; Serviddio, G.; Niglio, M.; Lo Caputo, S.; et al. Prevalence and Genetic Diversity of Blastocystis Sp. among Autochthonous and Immigrant Patients in Italy. Microb Pathog 2023, 185, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusaro, C.; Bernal, J.E.; Baldiris-Ávila, R.; González-Cuello, R.; Cisneros-Lorduy, J.; Reales-Ruiz, A.; Castro-Orozco, R.; Sarria-Guzmán, Y. Molecular Prevalence and Subtypes Distribution of Blastocystis Spp. in Humans of Latin America: A Systematic Review. Trop Med Infect Dis 2024, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebolla, M.F.; Silva, E.M.; Gomes, J.F.; Falcão, A.X.; Rebolla, M.V.F.; Franco, R.M.B. High Prevalence of Blastocystis Spp. Infection in Children and Staff Members Attending Public Urban Schools in São Paulo State, Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 2016, 58, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Power, S.E.; O’Toole, P.W.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P.; Fitzgerald, G.F. Intestinal Microbiota, Diet and Health. British Journal of Nutrition 2014, 111, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyhan, Y.E.; Güven, İ.; Aydın, M. Detection of Blastocystis Sp. in Ulcerative Colitis, Crohn’s and Chronic Diarrheal Patients by Microscopy, Culture and Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction. Microb Pathog 2023, 177, 106039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Arnoriaga-Rodríguez, M.; Garre-Olmo, J.; Puig, J.; Ramos, R.; Trelis, M.; Burokas, A.; Coll, C.; Zapata-Tona, C.; Pedraza, S.; et al. Presence of Blastocystis in Gut Microbiota Is Associated with Cognitive Traits and Decreased Executive Function. ISME Journal 2022, 16, 2181–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Wojciech, L.; Gascoigne, N.R.J.; Peng, G.; Tan, K.S.W. New Insights into the Interactions between Blastocystis, the Gut Microbiota, and Host Immunity. PLoS Pathog 2021, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yañez, C.M.; Hernández, A.M.; Sandoval, A.M.; Domínguez, M.A.M.; Muñiz, S.A.Z.; Gómez, J.O.G. Prevalence of Blastocystis and Its Association with Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes Ratio in Clinically Healthy and Metabolically Ill Subjects. BMC Microbiol 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda, S.; Tomiak, J.; Andersen, L.O.; Acosta, C.P.; Vasquez-A, L.R.; Stensvold, C.R.; Ramírez, J.D. Impact of Blastocystis Carriage and Colonization Intensity on Gut Microbiota Composition in a Non-Westernized Rural Population from Colombia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2025, 19, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castañeda, S.; Muñoz, M.; Villamizar, X.; Hernández, P.C.; Vásquez, L.R.; Tito, R.Y.; Ramírez, J.D. Microbiota Characterization in Blastocystis-Colonized and Blastocystis-Free School-Age Children from Colombia. Parasit Vectors 2020, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cena, H.; Calder, P.C. Defining a Healthy Diet: Evidence for the Role of Contemporary Dietary Patterns in Health and Disease. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wastyk, H.C.; Fragiadakis, G.K.; Perelman, D.; Dahan, D.; Merrill, B.D.; Yu, F.B.; Topf, M.; Gonzalez, C.G.; Van Treuren, W.; Han, S.; et al. Gut-Microbiota-Targeted Diets Modulate Human Immune Status. Cell 2021, 184, 4137–4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soldán, M.; Argalášová, Ľ.; Hadvinová, L.; Galileo, B.; Babjaková, J. The Effect of Dietary Types on Gut Microbiota Composition and Development of Non-Communicable Diseases: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaruddin, A.I.; Hamid, F.; Koopman, J.P.R.; Muhammad, M.; Brienen, E.A.T.; van Lieshout, L.; Geelen, A.R.; Wahyuni, S.; Kuijper, E.J.; Sartono, E.; et al. The Bacterial Gut Microbiota of Schoolchildren from High and Low Socioeconomic Status: A Study in an Urban Area of Makassar, Indonesia. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iddrisu, I.; Monteagudo-Mera, A.; Poveda, C.; Pyle, S.; Shahzad, M.; Andrews, S.; Walton, G.E. Malnutrition and Gut Microbiota in Children. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, K.M.; Mutasa, M.; Prendergast, A.J.; Humphrey, J.; Manges, A.R. Environmental Enteric Dysfunction Pathways and Child Stunting: A Systematic Review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2018, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tickell, K.D.; Atlas, H.E.; Walson, J.L. Environmental Enteric Dysfunction: A Review of Potential Mechanisms, Consequences and Management Strategies. BMC Med 2019, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaman Wahid, B.; Haque, M.A.; Gazi, M.A.; Fahim, S.M.; Faruque, A.S.G.; Mahfuz, M.; Ahmed, T. Site-Specific Incidence Rate of Blastocystis Hominis and Its Association with Childhood Malnutrition: Findings from a Multi-Country Birth Cohort Study. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2023, 108, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BEDCA Base de Datos Española de Composición de Alimentos. Available online: https://www.bedca.net/bdpub/index.php (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Fukagawa, N.K.; McKillop, K.; Pehrsson, P.R.; Moshfegh, A.; Harnly, J.; Finley, J. USDA’s FoodData Central: What Is It and Why Is It Needed Today? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2022, 115, 619–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shams-White, M.M.; Pannucci, T.R.E.; Lerman, J.L.; Herrick, K.A.; Zimmer, M.; Meyers Mathieu, K.; Stoody, E.E.; Reedy, J. Healthy Eating Index-2020: Review and Update Process to Reflect the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. J Acad Nutr Diet 2023, 123, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrera, Y.; Carrera, A.; Formación, Y. Cuestionario Internacional de Actividad Física (IPAQ). Revista Enfermería del Trabajo 2017, 7, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amore, R.; Ijaz, U.Z.; Schirmer, M.; Kenny, J.G.; Gregory, R.; Darby, A.C.; Shakya, M.; Podar, M.; Quince, C.; Hall, N. A Comprehensive Benchmarking Study of Protocols and Sequencing Platforms for 16S RRNA Community Profiling. BMC Genomics 2016, 17, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stensvold, C.R.; Ahmed, U.N.; Andersen, L.O.B.; Nielsen, H.V. Development and Evaluation of a Genus-Specific, Probe-Based, Internal-Process-Controlled Real-Time PCR Assay for Sensitive and Specific Detection of Blastocystis Spp. J Clin Microbiol 2012, 50, 1847–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippo, C.; Cavalieri, D.; Di Paola, M.; Ramazzotti, M.; Poullet, J.B.; Massart, S.; Collini, S.; Pieraccini, G.; Lionetti, P. Impact of Diet in Shaping Gut Microbiota Revealed by a Comparative Study in Children from Europe and Rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 14691–14696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deehan, E.C.; Yang, C.; Perez-Muñoz, M.E.; Nguyen, N.K.; Cheng, C.C.; Triador, L.; Zhang, Z.; Bakal, J.A.; Walter, J. Precision Microbiome Modulation with Discrete Dietary Fiber Structures Directs Short-Chain Fatty Acid Production. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 389–404.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Um, C.Y.; Peters, B.A.; Choi, H.S.; Oberstein, P.; Beggs, D.B.; Usyk, M.; Wu, F.; Hayes, R.B.; Gapstur, S.M.; McCullough, M.L.; et al. Grain, Gluten, and Dietary Fiber Intake Influence Gut Microbial Diversity: Data from the Food and Microbiome Longitudinal Investigation. Cancer Research Communications 2023, 3, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conlon, M.A.; Bird, A.R. The Impact of Diet and Lifestyle on Gut Microbiota and Human Health. Nutrients 2015, 7, 17–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Audebert, C.; Even, G.; Cian, A.; Blastocystis Investigation Group; Loywick, A.; Merlin, S.; Viscogliosi, E.; Chabé, M.; El Safadi, D.; Certad, G.; et al. Colonization with the Enteric Protozoa Blastocystis Is Associated with Increased Diversity of Human Gut Bacterial Microbiota. Sci Rep 2016, 6, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Stensvold, C.R.; Sørland, B.A.; Berg, R.P.K.D.; Andersen, L.O.; van der Giezen, M.; Bowtell, J.L.; El-Badry, A.A.; Belkessa, S.; Kurt, Ö.; Nielsen, H.V. Stool Microbiota Diversity Analysis of Blastocystis-Positive and Blastocystis-Negative Individuals. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tito, R.Y.; Chaffron, S.; Caenepeel, C.; Lima-Mendez, G.; Wang, J.; Vieira-Silva, S.; Falony, G.; Hildebrand, F.; Darzi, Y.; Rymenans, L.; et al. Population-Level Analysis of Blastocystis Subtype Prevalence and Variation in the Human Gut Microbiota. Gut 2019, 68, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, C.J.; Ajami, N.J.; O’Brien, J.L.; Hutchinson, D.S.; Smith, D.P.; Wong, M.C.; Ross, M.C.; Lloyd, R.E.; Doddapaneni, H.V.; Metcalf, G.A.; et al. Temporal Development of the Gut Microbiome in Early Childhood from the TEDDY Study. Nature 2018, 562, 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roswall, J.; Olsson, L.M.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Nilsson, S.; Tremaroli, V.; Simon, M.C.; Kiilerich, P.; Akrami, R.; Krämer, M.; Uhlén, M.; et al. Developmental Trajectory of the Healthy Human Gut Microbiota during the First 5 Years of Life. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippo, C.; Cavalieri, D.; Di Paola, M.; Ramazzotti, M.; Poullet, J.B.; Massart, S.; Collini, S.; Pieraccini, G.; Lionetti, P. Impact of Diet in Shaping Gut Microbiota Revealed by a Comparative Study in Children from Europe and Rural Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 14691–14696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korpela, K.; Salonen, A.; Virta, L.J.; Kekkonen, R.A.; De Vos, W.M. Association of Early-Life Antibiotic Use and Protective Effects of Breastfeeding: Role of the Intestinal Microbiota. JAMA Pediatr 2016, 170, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnenburg, E.D.; Smits, S.A.; Tikhonov, M.; Higginbottom, S.K.; Wingreen, N.S.; Sonnenburg, J.L. Diet-Induced Extinctions in the Gut Microbiota Compound over Generations. Nature 2016, 529, 212–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonnenburg, E.D.; Sonnenburg, J.L. The Ancestral and Industrialized Gut Microbiota and Implications for Human Health. Nat Rev Microbiol 2019, 17, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yatsunenko, T.; Rey, F.E.; Manary, M.J.; Trehan, I.; Dominguez-Bello, M.G.; Contreras, M.; Magris, M.; Hidalgo, G.; Baldassano, R.N.; Anokhin, A.P.; et al. Human Gut Microbiome Viewed across Age and Geography. Nature 2012, 486, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Nilsson, A.; Akrami, R.; Lee, Y.S.; De Vadder, F.; Arora, T.; Hallen, A.; Martens, E.; Björck, I.; Bäckhed, F. Dietary Fiber-Induced Improvement in Glucose Metabolism Is Associated with Increased Abundance of Prevotella. Cell Metab 2015, 22, 971–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Precup, G.; Vodnar, D.C. Gut Prevotella as a Possible Biomarker of Diet and Its Eubiotic versus Dysbiotic Roles: A Comprehensive Literature Review. British Journal of Nutrition 2019, 122, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Filippis, F.; Pasolli, E.; Tett, A.; Tarallo, S.; Naccarati, A.; De Angelis, M.; Neviani, E.; Cocolin, L.; Gobbetti, M.; Segata, N.; et al. Distinct Genetic and Functional Traits of Human Intestinal Prevotella Copri Strains Are Associated with Different Habitual Diets. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Singh, A.; Giometto, A.; Brito, I.L. Segatella Clades Adopt Distinct Roles within a Single Individual’s Gut. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, P.M.; Martins, A.F.; Ramalho, R.; Telo, G.H.; Leivas, G.; Maraschin, C.K.; Schaan, B.D. The Impact of Dietary, Surgical, and Pharmacological Interventions on Gut Microbiota in Individuals with Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2022, 189, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ajami, N.J.; El-Serag, H.B.; Hair, C.; Graham, D.Y.; White, D.L.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Plew, S.; Kramer, J.; et al. Dietary Quality and the Colonic Mucosa-Associated Gut Microbiome in Humans. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2019, 110, 701–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Bhat, Z.F.; Gounder, R.S.; Ahmed, I.A.M.; Al-Juhaimi, F.Y.; Ding, Y.; Bekhit, A.E.D.A. Effect of Dietary Protein and Processing on Gut Microbiota—A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ríos-Covián, D.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Margolles, A.; Gueimonde, M.; De los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G.; Salazar, N. Intestinal Short Chain Fatty Acids and Their Link with Diet and Human Health. Front Microbiol 2016, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, A.; De Vadder, F.; Kovatcheva-Datchary, P.; Bäckhed, F. From Dietary Fiber to Host Physiology: Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Key Bacterial Metabolites. Cell 2016, 165, 1332–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fackelmann, G.; Manghi, P.; Carlino, N.; Heidrich, V.; Piccinno, G.; Ricci, L.; Piperni, E.; Arrè, A.; Bakker, E.; Creedon, A.C.; et al. Gut Microbiome Signatures of Vegan, Vegetarian and Omnivore Diets and Associated Health Outcomes across 21,561 Individuals. Nat Microbiol 2025, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Sun, T. yu; He, Y.; Gou, W.; Zuo, L. shi yuan; Fu, Y.; Miao, Z.; Shuai, M.; Xu, F.; Xiao, C.; et al. Dietary Fruit and Vegetable Intake, Gut Microbiota, and Type 2 Diabetes: Results from Two Large Human Cohort Studies. BMC Med 2020, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz, M.; Guerrero-Araya, E.; Cortés-Tapia, C.; Plaza-Garrido, A.; Lawley, T.D.; Paredes-Sabja, D. Comprehensive Genome Analyses of Sellimonas Intestinalis, a Potential Biomarker of Homeostasis Gut Recovery. Microb Genom 2020, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kase, B.E.; Liese, A.D.; Zhang, J.; Murphy, E.A.; Zhao, L.; Steck, S.E. The Development and Evaluation of a Literature-Based Dietary Index for Gut Microbiota. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vacca, M.; Celano, G.; Calabrese, F.M.; Portincasa, P.; Gobbetti, M.; De Angelis, M. The Controversial Role of Human Gut Lachnospiraceae. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muralidharan, J.; Moreno-Indias, I.; Bulló, M.; Lopez, J.V.; Corella, D.; Castañer, O.; Vidal, J.; Atzeni, A.; Fernandez-García, J.C.; Torres-Collado, L.; et al. Effect on Gut Microbiota of a 1-y Lifestyle Intervention with Mediterranean Diet Compared with Energy-Reduced Mediterranean Diet and Physical Activity Promotion: PREDIMED-Plus Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2021, 114, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Component |

Blastocystis Present n=8 |

Blastocystis Absent=38 |

p-value | Adjusted p-value |

| Energy intake | 2812.75 ± 721.59 | 2728.89 ± 950.18 | 0.522 | 0.642 |

| Caloric activity | 2490.50 ± 622.20 | 2449.11 ± 650.75 | 0.805 | 0.882 |

| Fruits | 4.01 ± 1.21 | 2.82 ± 1.65 | 0.071 | 0.298 |

| Whole fruits | 1.56 ± 0.96 | 1.38 ± 1.74 | 0.195 | 0.390 |

| Vegetables | 2.53 ± 1.25 | 1.81 ± 0.77 | 0.172 | 0.390 |

| Legumes | 2.83 ± 0.79 | 3.35 ± 1.42 | 0.184 | 0.390 |

| Whole grains | 9.03 ± 2.43 | 7.75 ± 3.41 | 0.331 | 0.530 |

| Dairy | 4.12 ± 2.39 | 3.78 ± 2.47 | 0.503 | 0.642 |

| Protein foods | 3.32 ± 0.41 | 3.21 ± 0.53 | 0.485 | 0.642 |

| Seafood/plant protein | 3.28 ± 1.72 | 3.21 ± 1.64 | 0.835 | 0.882 |

| Fatty acid ratio | 4.77 ± 1.43 | 3.16 ± 2.20 | 0.020* | 0.163 |

| Refined grains | 9.18 ± 1.25 | 8.08 ± 2.32 | 0.262 | 0.466 |

| Added sugars | 1.10 ± 2.03 | 2.40 ± 2.58 | 0.193 | 0.390 |

| Saturated fat | 8.33 ± 2.12 | 6.15 ± 3.03 | 0.075 | 0.298 |

| Total HEI-2020 | 64.03 ± 2.36 | 56.67 ± 9.91 | 0.005* | 0.079 |

| Component |

Blastocystis Present n=8 |

Blastocystis Absent n=29 |

p-value | Adjusted p-value |

| Energy intake | 4678.75 ± 2245.32 | 3175.45 ± 1459.14 | 0.140 | 0.681 |

| Caloric activity | 2070.25 ± 396.57 | 2148.70 ± 752.25 | 0.981 | 0.981 |

| Fruits | 2.67 ± 2.06 | 3.50 ± 1.45 | 0.225 | 0.681 |

| Whole fruits | 2.29 ± 2.06 | 2.30 ± 1.77 | 0.961 | 0.981 |

| Vegetables | 0.55 ± 0.49 | 1.70 ± 0.72 | 0.001** | 0.018* |

| Legumes | 2.65 ± 1.98 | 3.40 ± 1.68 | 0.426 | 0.681 |

| Whole grains | 7.86 ± 3.51 | 6.41 ± 3.71 | 0.468 | 0.681 |

| Dairy | 4.57 ± 1.79 | 4.66 ± 3.05 | 0.788 | 0.901 |

| Protein foods | 2.72 ± 0.66 | 2.91 ± 0.63 | 0.654 | 0.805 |

| Seafood/plant protein | 2.62 ± 0.51 | 1.72 ± 1.82 | 0.246 | 0.681 |

| Fatty acid ratio | 4.58 ± 3.41 | 3.43 ± 3.35 | 0.445 | 0.681 |

| Refined grains | 7.78 ± 3.41 | 6.48 ± 3.21 | 0.412 | 0.681 |

| Added sugars | 2.79 ± 2.74 | 1.37 ± 3.24 | 0.065 | 0.520 |

| Saturated fat | 6.69 ± 4.80 | 6.09 ± 3.76 | 0.607 | 0.805 |

| Total HEI-2020 | 57.13 ± 7.20 | 53.78 ± 11.78 | 0.434 | 0.681 |

| Diet Component (HEI-2020) | R² | F | p-value |

| Protein foods score | 0.232 | 3.63 | 0.017* |

| Total vegetable score | 0.167 | 2.40 | 0.044* |

| Total fruit score | 0.132 | 1.82 | 0.117 |

| Whole fruit score | 0.135 | 1.88 | 0.117 |

| Legume score | 0.097 | 1.29 | 0.260 |

| Refined grains score | 0.092 | 1.21 | 0.279 |

| Whole grain score | 0.075 | 0.97 | 0.408 |

| Saturated fats score | 0.070 | 0.91 | 0.421 |

| Sodium score | 0.071 | 0.92 | 0.464 |

| Seafood and plant protein score | 0.064 | 0.82 | 0.482 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).