Submitted:

12 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Diversity of EF and Its Influencing Factors

2.1. Classification of EF

2.2. Influencing Factors of EF Biodiversity

2.2.1. Effect of Temperature and Humidity on the EF

2.2.2. Landscape Composition Could Affect the Community Structure of EF

2.2.3. The Infestation of Host Insects by EF Is Influenced by Different Host Types and Insect States

2.2.4. Agricultural Activities Can Affect Soil EF

2.2.5. Altitude Is an Important Environmental Factor Affecting EF Community

2.2.6. The Effect of the Niche on EF

3. Interactions Between EF and Host Insects

3.1. The Process by Which EF Infects Insects

3.2. Molecular Basis of Evolutionary Adaptation in EF

3.3. Diffusion of EF Spores

3.4. EF Completes the Parasitic Life Cycle in the Host

3.5. Strategies for Insect Response to EF

4. EF Colonize Plants

4.1. EF Promotes Plant Growth

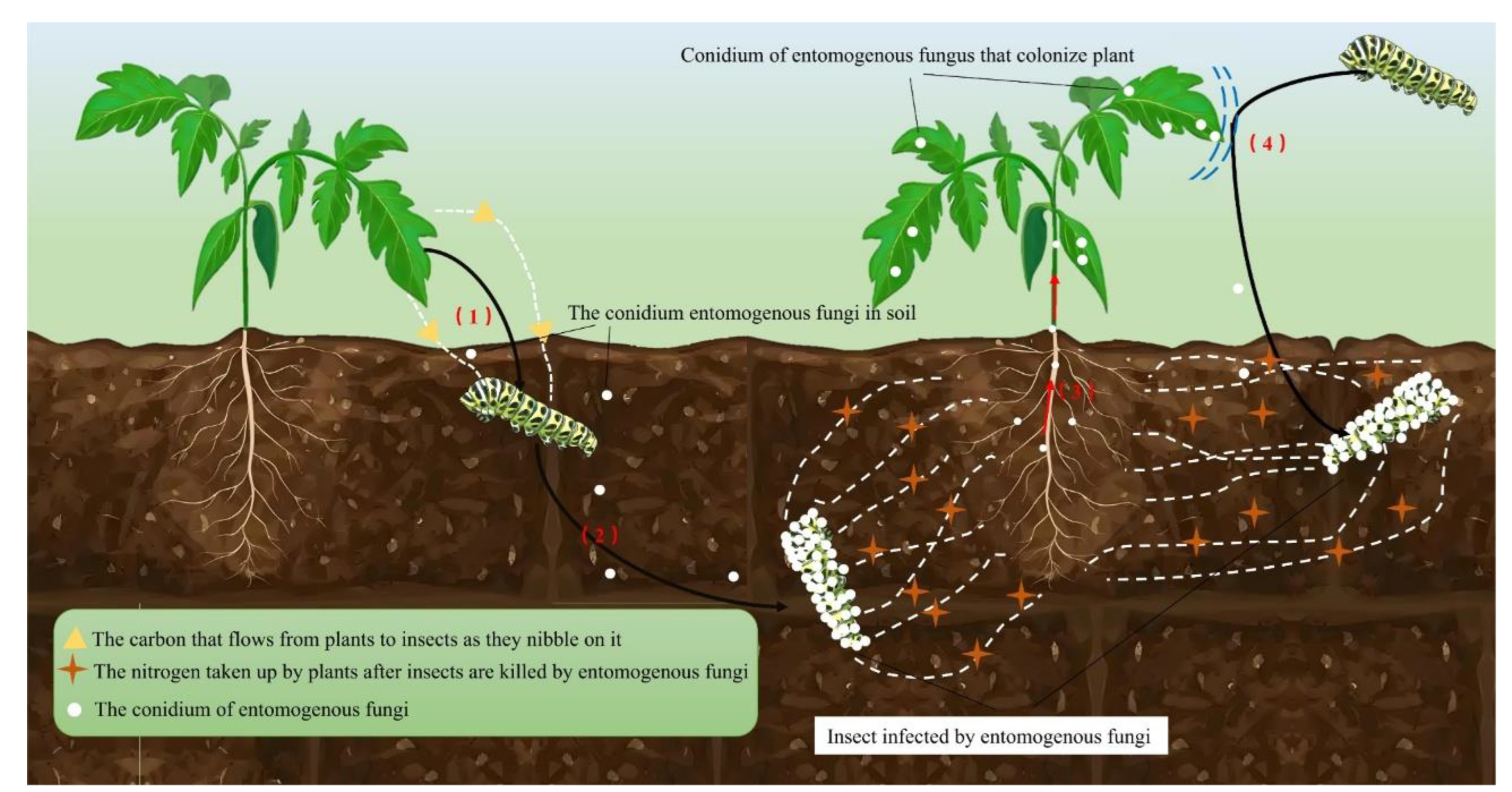

4.2. EF-Insect-Plant Interaction

5. EF Controls Agricultural Pests

6. Mycelia of EF Participated in the Construction of Mycelial Network System

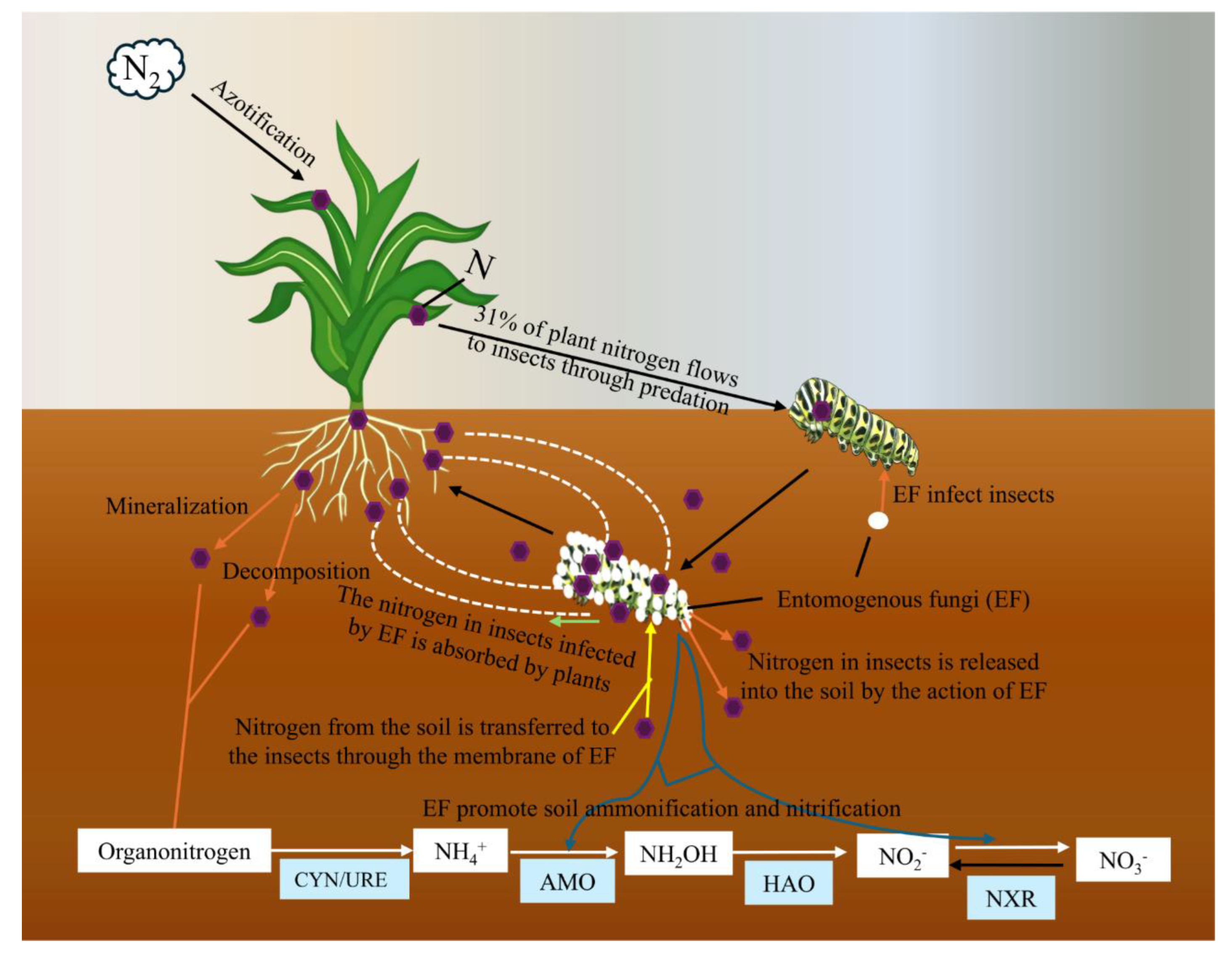

7. EF Participate in Soil Nitrogen Cycling

8. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

8.1. Fully Develop the Medicinal and Edible Values of CF

8.2. Make Full Use of the Potential of EF Biological Control Agents

8.3. Environmental Driving Mechanisms and Technical Analysis of EF Biodiversity

8.4. The Multi-Dimensional Ecological Roles and Molecular Regulatory Mechanisms of EF Hyphae

8.5. Multi-Functional Ecological Interaction Mechanisms of EF and Their Agricultural Application Prospects

8.6. The Mechanism of Soil Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling Mediated by EF

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EF | entomogenous Fungi |

| CF | cordyceps fungi |

| EPF | entomophthoralean fungi |

References

- Yan, J. Q.; Bau, T. Cordyceps ningxiaensis sp. nov.; a new species from dipteran pupae in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region of China. Nova hedwigia 2015, 100, 251–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saminathan, N.; Subramanian, J.; Sankaran Pagalahalli, S.; Theerthagiri, A.; Mariappan, P. Entomopathogenic fungi: translating research into field applications for crop protection. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 2025, 19, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, M.A.; Castilho, A.M.; Fraga, M.E. Classification and infection mechanism of entomopathogenic fungi. Arquivos do Instituto Biológico 2017, 84, e0552015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wint, F.C.; Nicholson, S.; Koid, Q.Q.; Zahra, S.; Chestney-Claassen, G.; Seelan, J.S.; Xie, J.; Xing, S.; Fayle, T.M.; Haelewaters, D. Introducing a global database of entomopathogenic fungi and their host associations. Scientific Data 2024, 11, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantzoukas, S.; Kitsiou, F.; Natsiopoulos, D.; Eliopoulos, P.A. Entomopathogenic fungi: interactions and applications. Encyclopedia 2022, 2, 646–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, S. Insect pathogenic fungi, genomics, molecular interactions, and genetic improvements. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2017, 62, 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, W.; Adnan, M.; Shabbir, A.; Naveed, H.; Abubakar, Y.S.; Qasim, M.; Tayyab, M.; Noman, A.; Nisar, M.S.; Khan, K.A.; Ali, H. Insect-fungal-interactions: A detailed review on entomopathogenic fungi pathogenicity to combat insect pests. Microb. Pathog. 2021, 159, 105122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.; Zou, X.; Cao, W.; Xu, Z.; Liang, Z. Two new species of Hirsutella (Ophiocordycipitaceae, Sordariomycetes) that are parasitic on lepidopteran insects from China. MycoKeys 2021, 82, 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brockerhoff, E.G.; Barbaro, L.; Castagneyrol, B.; Forrester, D.I.; Gardiner, B.A.; González-Olabarria, J.R.; Lyver, P.O.B.; Meurisse, N.; Oxbrough, A.; Taki, H.; et al. Forest biodiversity, ecosystem functioning and the provision of ecosystem services. Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 26, 3005–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Hong, Y.; Mai, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Guo, L. Internal and external microbial community of the Thitarodes moth, the host of Ophiocordyceps sinensis. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behie, S.W.; Bidochka, M.J. Carbon translocation from a plant to an insect-pathogenic endophytic fungus. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovett, G.M.; Christenson, L.M.; Groffman, P.M.; Jones, C.G.; Hart, J.E.; Mitchell, M.J. Insect defoliation and nitrogen cycling in forests. BioScience 2002, 52, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behie, S.W.; Zelisko, P.M.; Bidochka, M.J. Endophytic insect-parasitic fungi translocate nitrogen directly from insects to plants. Science 2012, 336, 1576–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuypers, M.M.M.; Marchant, H.K.; Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Cheng, X.; Liu, X.; Xiang, M. Genome Studies on Nematophagous and Entomogenous Fungi in China. J. Fungi 2016, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J.; Zou, X.; Yu, L.Q.; Zhang, J.; Han, Y.; Zou, X. A new entomopathogenic fungus, Ophiocordyceps ponerus sp. nov., from China. Phytotaxa 2018, 343, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z. Transcriptomic analysis of the orchestrated molecular mechanisms underlying fruiting body initiation in Chinese cordyceps. Gene 2020, 763, 145061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebremariam, A.; Chekol, Y.; Assefa, F. Phenotypic, molecular, and virulence characterization of entomopathogenic fungi, Beauveria bassiana (Balsam) Vuillemin, and Metarhizium anisopliae (Metschn.) Sorokin from soil samples of Ethiopia for the development of mycoinsecticide. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litwin, A.; Nowak, M.; Różalska, S. Entomopathogenic fungi: unconventional applications. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 19, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, G.; Shin, H.S.; Leyva-Gómez, G.; Del Prado-Audelo, M.L.; Cortés, H.; Singh, Y.D.; Panda, M.K.; Mishra, A.P.; Nigam, M.; Saklani, S.; et al. Cordyceps spp.: A review on its immune-stimulatory and other biological potentials. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 602364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukhari, T.; Middelman, A.; Koenraadt, C.J.; Takken, W.; Knols, B.G. Factors affecting fungus-induced larval mortality in Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles stephensi. Malar. J. 2010, 9, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Y.; Feng, P.; Wang, C. Fungi that infect insects: altering host behavior and beyond. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, M.; Cao, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, K.; Wang, C. A life-and-death struggle: interaction of insects with entomopathogenic fungi across various infection stages. Front. Immunol. 2024, 14, 1329843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S.; Shang, J.; Sun, Y.; Tang, G.; Wang, C. Fungal infection of insects: molecular insights and prospects. Trends Microbiol. 2024, 32, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.Q.; Wang, N.; Qu, L.H.; Li, T.H.; Zhang, W.M. Determination of the anamorph of Cordyceps sinensis inferred from the analysis of the ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacers and 5.8 S rDNA. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2001, 29, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kepler, R.M.; Rehner, S.A.; Aime, M.C.; Smith, K.E.; Rossman, A.Y.; Chaverri, P.; Shrestha, B.; Spatafora, J.W. A phylogenetically-based nomenclature for Cordycipitaceae (Hypocreales). IMA Fungus 2017, 8, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, G.H.; Hywel-Jones, N.L.; Sung, J.M.; Luangsa-Ard, J.J.; Shrestha, B.; Spatafora, J.W. Phylogenetic classification of Cordyceps and the clavicipitaceous fungi. Stud. Mycol. 2007, 57, 5–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kepler, R.M.; Sung, G.H.; Ban, S.; Nakagiri, A.; Chen, M.; Huang, B.; Li, Z.; Spatafora, J.W. The phylogenetic placement of hypocrealean insect pathogens in the genus Polycephalomyces: an application of One Fungus One Name. Fungal Biol. 2013, 117, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mongkolsamrit, S.; Noisripoom, W.; Thanakitpipattana, D.; Wutikhun, T.; Spatafora, J.W.; Luangsa-ard, J.J. Molecular phylogeny and morphology reveal cryptic species in Blackwellomyces and Cordyceps (Cordycipitaceae) from Thailand. Mycol. Prog. 2020, 19, 957–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, E.H.; Yang, D.R.; Jiang, J.J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.B.; Yao, N.Y.; Ge, X.J.; et al. The caterpillar fungus, Ophiocordyceps sinensis, genome provides insights into highland adaptation of fungal pathogenicity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahsan, S.M.; Rauf, A.; Rehman, S.; Ahmad, P. Plant-Entomopathogenic fungi interaction: recent progress and future prospects on endophytism-mediated growth promotion and biocontrol. Plants 2024, 13, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, S.; Li, C. Cordycepin extracted from Cordyceps militaris mitigated CUMS-induced depression of rats via targeting GSK3β/β-catenin signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 340, 119249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.; Chen, Z.; Malik, K.; Li, C. Comparative metabolite profiling between Cordyceps sinensis and other Cordyceps by untargeted UHPLC-MS/MS. Biology 2025, 14, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Guo, M.; Wang, J.; Li, Y. Preparation, characterization, bioactivity, and safety evaluation of PEI-modified PLGA nanoparticles loaded with polysaccharide from Cordyceps militaris. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, F.; Wu, W. Application of UHPLC-ESI-MS/MS-based metabonomic techniques to analyze the Cordyceps cicadae metabolic profile changes to the CO(NH₂)₂ response mechanism in the process of ergosterol synthesis. Fermentation 2025, 11, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippou, C.; Coutts, R.H.A.; Kotta-Loizou, I.; El-Kamand, S.; Papanicolaou, A. Transcriptomic analysis reveals molecular mechanisms underpinning mycovirus-mediated hypervirulence in Beauveria bassiana infecting Tenebrio molitor. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y. Fungal evasion of Drosophila immunity involves blocking the cathepsin-mediated cleavage maturation of the danger-sensing protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2419343122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; He, D. Potential geographical distribution of Cordyceps cicadae and its two hosts in China under climate change. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1519560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y. Antioxidant and anti-aging activities of polysaccharides from Cordyceps cicadae. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 157, 394–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Zou, X. A strain of Talaromyces assiutensis provides multiple protection effects against insect pests and a fungal pathogen after endophytic settlement in soybean plants. Biol. Control 2025, 201, 105703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Qi, H.; Zhang, F. Parasitism by entomopathogenic fungi and insect host defense strategies. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, G.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, H.; Zou, X. Filtration effect of Cordyceps chanhua mycoderm on bacteria and its transport function on nitrogen. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e01179–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Z.; Li, X.; Malik, K.; Li, C. Metagenomic analysis: alterations of soil microbial community and function due to the disturbance of collecting Cordyceps sinensis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, X. Research and development of Cordyceps resources from an ecological perspective. In Cordyceps and Allied Species; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 27–62. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, M.E. Helminth-host-environment interactions: Looking down from the tip of the iceberg. J. Helminthol. 2023, 97, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shashidhar, M.G.; Giridhar, P.; Sankar, K.U.; Manohar, B. Bioactive principles from Cordyceps sinensis: A potent food supplement - A review. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1013–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, W.T.; Lee, C.H.; Chen, C.C.; Chen, L.C.; Huang, C.Y.; Lee, Y.J. Protective effects of Cordyceps militaris against hepatocyte apoptosis and liver fibrosis induced by high palmitic acid diet. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 15, 1438997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. Efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine Cordyceps sinensis as an adjunctive treatment in patients with renal dysfunction: a systematic-review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2025, 11, 1477569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastirčáková, K.; Zemek, R. Biodiversity and ecology of organisms associated with woody plants. Forests 2025, 16, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, J. Impact of Cordyceps sinensis on coronary computed tomography angiography image quality and renal function in a beagle model of renal impairment. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1538916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Y. Revisiting fermented buckwheat: a comprehensive examination of strains, bioactivities, and applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doan, U.V.; Mendez Rojas, B.; Kirby, R. Unintentional ingestion of Cordyceps fungus-infected cicada nymphs causing ibotenic acid poisoning in Southern Vietnam. Clin. Toxicol. 2017, 55, 893–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, C.N.; de Sousa Santos, Y.; de Rezende, R.R.; Alfenas-Zerbini, P. Identification of a novel polymycovirus infecting the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium robertsii. Arch. Virol. 2025, 170, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mushyakhwo, K.; Maxwell, L.A.; Nai, Y.S.; Srinivasan, R.; Hwang, S.Y. Beauveria bassiana-based management of Thrips palmi in greenhouse. BioControl 2025, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Gou, J.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zou, X. Endophytic colonization via Cordyceps cateniannulata induces a growth-enhancing effect and increases the resistance of tomato plants against Tetranychus urticae (Koch). Crop Prot. 2025, 193, 107182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mushtaq, A.R.; Bukhari, S.A.; Mushtaq, M.A.; Hussnain, M.; Rehman, U.U. Entomopathogenic fungi: Revolutionary allies in sustainable pest management and the overcoming of challenges in large-scale field applications. Sci. Res. Timelines J. 2025, 3, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa, E.Z.; Housseiny, M.M.; Omran, A.A. Fungicidal efficiency of silver and copper nanoparticles produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens ATCC 17397 against four Aspergillus species: a molecular study. J. Clust. Sci. 2019, 30, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, B.; Bilgo, E.; Diabate, A.; St. Leger, R.J. A review of progress toward field application of transgenic mosquitocidal entomopathogenic fungi. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2316–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salazar-Cerezo, S.; de Vries, R.P.; Garrigues, S. Strategies for the development of industrial fungal producing strains. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, M.; Chen, Y.; Guo, D.; Li, J. Traditional uses, origins, chemistry and pharmacology of Bombyx batryticatus: A review. Molecules 2017, 22, 1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Insumrong, K.; Chaiyana, W.; Sae-Lim, N.; Chansakaow, S.; Okonogi, S. In vitro skin penetration of 5α-reductase inhibitors from Tectona grandis L.f. leaf extracts. Molecules 2025, 30, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Tang, J.; Tu, J.; Guo, X. Solvent fractionation and LC-MS profiling, antioxidant properties, and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of Bombyx batryticatus. Molecules 2025, 30, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Y.P.; Wen, T.C.; Chen, C.D.; Hsieh, C.W.; Sung, J.M. Polycephalomycetaceae, a new family of clavicipitoid fungi segregates from Ophiocordycipitaceae. Fungal Divers. 2023, 120, 1–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, N.; Sharma, A.; Bora, P. Expanding the functional landscape of microbial entomopathogens in agriculture beyond pest management. Folia Microbiol. 2025, 70, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sami, A.; Ali, S.; Khan, A.; Khan, S.; Khan, S.; Khan, A.; Khan, A.; Khan, A.; Khan, A.; Khan, A.; et al. CRISPR-Cas9-based genetic engineering for crop improvement under drought stress. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 5814–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Dijk, A.; Fourie, G.; van der Nest, M.A.; van der Waals, J.E.; Wingfield, M.J. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing reveals that the Pgs gene of Fusarium circinatum is involved in pathogenicity, growth and sporulation. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2025, 177, 103970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Půža, V.; Tarasco, E. Interactions between entomopathogenic fungi and entomopathogenic nematodes. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, R.R.; Buckner, J.S.; Freeman, T.P. Cuticular lipids and silverleaf whitefly stage affect conidial germination of Beauveria bassiana and Paecilomyces fumosoroseus. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2003, 84, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.Q.; Zhang, K.Q. Microbial control of plant-parasitic nematodes: a five-party interaction. Plant Soil 2006, 288, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Sit, W.H.; Lee, C.Y.; Wan, J.M. Cordyceps cicadae induces G2/M cell cycle arrest in MHCC97H human hepatocellular carcinoma cells: a proteomic study. Chin. Med. 2014, 9, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Borneman, J.; Ruegger, P.; Liang, L.; Zhang, K.Q. Molecular mechanisms of the interactions between nematodes and nematophagous microorganisms. In Plant Defence: Biological Control; Springer: Cham, 2020; pp. 421–441. [Google Scholar]

- Gotti, I.A.; Ríos-Donato, N.; Pelizza, S.A.; López-Lastra, C.C.; Scorsetti, A.C. Blastospores from Metarhizium anisopliae and Metarhizium rileyi are not always as virulent as conidia are towards Spodoptera frugiperda caterpillars and use different infection mechanisms. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francis, F.; Fingu-Mabola, J.C.; Ben Fekih, I. Direct and endophytic effects of fungal entomopathogens for sustainable aphid control: a review. Agriculture 2022, 12, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, Y.; Tang, X.; Li, G.; Qiu, R. Metabolism of Penicillium oxalicum-mediated microbial community reconstructed by nitrogen improves stable aggregates formation in bauxite residue: a field-scale demonstration. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 493, 144963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Guo, S.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Genomic, transcriptomic, and ecological diversity of Penicillium species in cheese rind microbiomes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2024, 171, 103862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Y.; Yang, T.; Zhang, K.; Shen, C.; Chu, H. Fungal communities along a small-scale elevational gradient in an alpine tundra are determined by soil carbon nitrogen ratios. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veres, A.; Petit, S.; Conord, C.; Lavigne, C. Does landscape composition affect pest abundance and their control by natural enemies? A review. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 166, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, F.P.; Moura, D.S.; Vivanco, J.M.; Silva-Filho, M.C. Plant-insect-pathogen interactions: a naturally complex ménage à trois. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2017, 37, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tkaczuk, C.; Majchrowska-Safaryan, A. Temperature requirements for the colony growth and conidial germination of selected isolates of entomopathogenic fungi of the Cordyceps and Paecilomyces genera. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Dong, X.; Xu, S.; Cai, Q. Species diversity and distribution characteristics of entomogenous fungi in Zipeng Mountain National Forest Park. Chin. J. Biol. Control 2018, 34, 568. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, T.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, Y.; Hu, Q. Isolation and classification of fungal whitefly entomopathogens from soils of Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and Gansu Corridor in China. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0156087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philippot, L.; Chenu, C.; Kappler, A.; Rillig, M.C.; Fierer, N. The interplay between microbial communities and soil properties. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozo, M.J.; Zabalgogeazcoa, I.; Vázquez de Aldana, B.R.; Martínez-Medina, A. Untapping the potential of plant mycobiomes for applications in agriculture. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 60, 102034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, E.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Soil pH and nutrients shape the vertical distribution of microbial communities in an alpine wetland. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. Assessing the structure and diversity of fungal community in plant soil under different climatic and vegetation conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1288066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labouyrie, M.; Routh, D.; Taudière, A.; Cébron, A.; Turpault, M.P.; Uroz, S. Patterns in soil microbial diversity across Europe. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Yang, Z.; He, K.; Zhou, W.; Feng, W. Soil fungal community diversity, co-occurrence networks, and assembly processes under diverse forest ecosystems. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Q.; Chen, Q.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Soil microbial distribution depends on different types of landscape vegetation in temperate urban forest ecosystems. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 858254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. Differences in soil microbial communities across soil types in China’s temperate forests. Forests 2024, 15, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, G.X.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. A new entomopathogenic fungus, Ophiocordyceps xifengensis sp. nov., from Liaoning, China. Phytotaxa 2024, 642, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldmann, K.; Schöning, I.; Buscot, F.; Wubet, T. Forest management type influences diversity and community composition of soil fungi across temperate forest ecosystems. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adnan, M.; Islam, W.; Gang, L.; Chen, H.Y. Advanced research tools for fungal diversity and its impact on forest ecosystem. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 45044–45062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qayyum, M.A.; Wakil, W.; Arif, M.J.; Sahi, S.T.; Dunlap, C.A. Diversity and correlation of entomopathogenic and associated fungi with soil factors. J. King Saud Univ. Sci. 2021, 33, 101520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.P.M.; Hughes, D.P. Diversity of entomopathogenic fungi: which groups conquered the insect body? Adv. Genet. 2016, 94, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vukicevich, E.; Lowery, D.T.; Bennett, J.A.; Hart, M. Influence of groundcover vegetation, soil physicochemical properties, and irrigation practices on soil fungi in semi-arid vineyards. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadyś, M.; Kennedy, R.; West, J.S. Potential impact of climate change on fungal distributions: analysis of 2 years of contrasting weather in the UK. Aerobiologia 2016, 32, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbessenou, A.; Tounou, A.K.; Dannon, E.A.; Agboton, C.; Srinivasan, R.; Pittendrigh, B.R.; Tamò, M. Temperature-dependent modelling and spatial prediction reveal suitable geographical areas for deployment of two Metarhizium anisopliae isolates for Tuta absoluta management. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.P.; Sun, M.H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.Z.; Chen, S.Y. Development of biphasic culture system for an entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana PfBb strain and its virulence on a defoliating moth Phauda flammans (Walker). J. Fungi 2025, 11, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, H.; Pell, J.K.; Alderson, P.G.; Clark, S.J.; Pye, B.J. Laboratory evaluation of temperature effects on the germination and growth of entomopathogenic fungi and on their pathogenicity to two aphid species. Pest Manag. Sci. 2003, 59, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, G.E. Pathogenicity of three entomopathogenic fungi to the southern pine beetle at various temperatures and humidities. Environ. Entomol. 1973, 2, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Kumar, P.; Malik, A. Effect of temperature and humidity on pathogenicity of native Beauveria bassiana isolate against Musca domestica L. J. Parasit. Dis. 2015, 39, 697–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michereff-Filho, M.; Rezende, J.M.; Venzon, M.; Gondim, M.G.C. The effect of spider mite-pathogenic strains of Beauveria bassiana and humidity on the survival and feeding behavior of Neoseiulus predatory mite species. Biol. Control 2022, 176, 105083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Bai, P.; Liu, B.; Yu, J. On the virulence of two Beauveria bassiana strains against the fall webworm, Hyphantria cunea (Durry) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae), larvae and their biological properties in relation to different abiotic factors. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2021, 31, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranga, R.O.; Kaaya, G.P.; Mueke, J.M.; Hassanali, A. Effects of combining the fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae on the mortality of the tick Amblyomma variegatum (Ixodidae) in relation to seasonal changes. Mycopathologia 2005, 159, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Duan, M.; Yu, Z. Agricultural landscapes and biodiversity in China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2013, 166, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Carmona, N.; Sánchez, A.C.; Remans, R.; Jones, S.K. Complex agricultural landscapes host more biodiversity than simple ones: A global meta-analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2203385119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartual, A.M.; Potts, S.G.; Woodcock, B.A.; Dicks, L.V. The potential of different semi-natural habitats to sustain pollinators and natural enemies in European agricultural landscapes. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2019, 279, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinnert, A.; Krimmer, E.; Martin, E.A.; Scherber, C.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Tscharntke, T. Landscape features support natural pest control and farm income when pesticide application is reduced. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyling, N.V.; Eilenberg, J. Ecology of the entomopathogenic fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae in temperate agroecosystems: potential for conservation biological control. Biol. Control 2007, 43, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.E.; Posada, F.; Aime, M.C.; Pava-Ripoll, M.; Infante, F.; Rehner, S.A. Entomopathogenic fungal endophytes. Biol. Control 2008, 46, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fine Licht, H.H.; Jensen, A.B.; Eilenberg, J. Insect hosts are nutritional landscapes navigated by fungal pathogens. Ecology 2025, 106, e70015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murindangabo, Y.T.; Yobo, K.S.; Laing, M.D. Relevance of entomopathogenic fungi in soil-plant systems. Plant Soil 2024, 495, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallsworth, J.E.; Magan, N. Water and temperature relations of growth of the entomogenous fungi Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae, and Paecilomyces farinosus. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 1999, 74, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagchi, R.; Gallery, R.E.; Gripenberg, S.; Gurr, S.J.; Narayan, L.; Addis, C.E.; Freckleton, R.P.; Lewis, O.T. Pathogens and insect herbivores drive rainforest plant diversity and composition. Nature 2014, 506, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y. Enhancing soil health and nutrient cycling through soil amendments: Improving the synergy of bacteria and fungi. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 923, 171332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y. Distributional patterns of soil nematodes in relation to environmental variables in forest ecosystems. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2021, 3, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagimu, N.; Ferreira, T.; Malan, A.P. The attributes of survival in the formulation of entomopathogenic nematodes utilised as insect biocontrol agents. Afr. Entomol. 2017, 25, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkaczuk, C.; Król, A.; Majchrowska-Safaryan, A.; Nicewicz, Ł. The occurrence of entomopathogenic fungi in soils from fields cultivated in conventional and organic systems. J. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 15, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Bravo, M.; Garrido-Jurado, I.; Valverde-García, P.; Quesada-Moraga, E. Land-use type drives soil population structures of the entomopathogenic fungal genus Metarhizium. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tscharntke, T.; Steffan-Dewenter, I.; Kruess, A.; Thies, C. Contribution of small habitat fragments to conservation of insect communities of grassland-cropland landscapes. Ecol. Appl. 2002, 12, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.J.J.A.; Booij, C.J.H.; Tscharntke, T. Sustainable pest regulation in agricultural landscapes: a review on landscape composition, biodiversity and natural pest control. Proc. R. Soc. B 2006, 273, 1715–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duru, M.; Therond, O.; Martin, G.; Martin-Clouaire, R.; Magne, M.A.; Justes, E.; Journet, E.P.; Aubertot, J.N.; Savary, S.; Bergez, J.E.; et al. How to implement biodiversity-based agriculture to enhance ecosystem services: a review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 35, 1259–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, M.; Opatovsky, I. A review on nutritional and non-nutritional interactions of symbiotic and associated fungi with insects. Symbiosis 2023, 91, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcoto, M.O.; de Souza, D.J.; de Queiroz, A.C.; de Azevedo, R.S.; de Paula, M.S.; Pupo, M.T. Fungus-growing insects host a distinctive microbiota apparently adapted to the fungiculture environment. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aung, O.M.; Soytong, K.; Hyde, K.D. Diversity of entomopathogenic fungi in rainforests of Chiang Mai Province, Thailand. Fungal Divers. 2008, 30, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gindin, G.; Samish, M.; Zangi, G.; Mishoutchenko, A.; Glazer, I. The susceptibility of different species and stages of ticks to entomopathogenic fungi. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 2002, 28, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samish, M.; Gindin, G.; Alekseev, E.; Glazer, I. Pathogenicity of entomopathogenic fungi to different developmental stages of Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae). J. Parasitol. 2001, 87, 1355–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.M.; Xie, W.; Zhi, J.R.; Zou, X. Frankliniella occidentalis pathogenic fungus Lecanicillium interacts with internal microbes and produces sublethal effects. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 97, 105679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soth, S.; Lacey, L.A.; Mercadier, G. You are what you eat: fungal metabolites and host plant affect the susceptibility of diamondback moth to entomopathogenic fungi. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mäder, P.; Edenhofer, S.; Boller, T.; Wiemken, A.; Niggli, U. Arbuscular mycorrhizae in a long-term field trial comparing low-input (organic, biological) and high-input (conventional) farming systems in a crop rotation. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2000, 31, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, E.H.; Jaronski, S.T.; Hodgson, E.W.; Gassmann, A.J. Abundance of soil-borne entomopathogenic fungi in organic and conventional fields in the Midwestern USA with an emphasis on the effect of herbicides and fungicides on fungal persistence. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0133613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Qu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, Y.; Sun, H. Soil fungal community and potential function in different forest ecosystems. Diversity 2022, 14, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, Y.; Portal, O.; Lysøe, E.; Meyling, N.V.; Klingen, I. Diversity and abundance of Beauveria bassiana in soils, stink bugs and plant tissues of common bean from organic and conventional fields. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2017, 150, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klingen, I.; Eilenberg, J.; Meadow, R. Effects of farming system, field margins and bait insect on the occurrence of insect pathogenic fungi in soils. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 91, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perazzolli, M.; Antonielli, L.; Storari, M.; Puopolo, G.; Pancher, M.; Giovannini, O.; Pertot, I. Resilience of the natural phyllosphere microbiota of the grapevine to chemical and biological pesticides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 3585–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goble, T.A.; Dames, J.F.P.; Hill, M.; Moore, S.D. The effects of farming system, habitat type and bait type on the isolation of entomopathogenic fungi from citrus soils in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. BioControl 2010, 55, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, M.; Ma, K.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Contrasting floristic diversity of the Hengduan Mountains, the Himalayas and the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau sensu stricto in China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, J. Diversity and correlation analysis of endophytes and top metabolites in Phlomoides rotata roots from high-altitude habitats. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, K.S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.Q. Evolutionary origin of species diversity on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Syst. Evol. 2021, 59, 1142–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglis, G.D.; Duke, G.M.; Goettel, M.S.; Kabaluk, J.T.; Ortega-Polo, R. Biogeography and genotypic diversity of Metarhizium brunneum and Metarhizium robertsii in northwestern North American soils. Can. J. Microbiol. 2019, 65, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowther, T.W.; Maynard, D.S.; Crowther, T.R.; Peccia, J.; Smith, D.P.; Bradford, M.A. Untangling the fungal niche: the trait-based approach. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrego, N.; Ovaskainen, O.; Somervuo, P.; Huotari, T.; Norberg, A.; Nyman, J.; Roslin, T. Airborne DNA reveals predictable spatial and seasonal dynamics of fungi. Nature 2024, 631, 835–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaloner, T.M.; Gurr, S.J.; Bebber, D.P. Geometry and evolution of the ecological niche in plant-associated microbes. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Urquiza, A.; Keyhani, N.O. Molecular genetics of Beauveria bassiana infection of insects. Adv. Genet. 2016, 94, 165–249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rohlfs, C.; Trenkamp, M.; Pötsch, L.; Steinmetz, H.; Dahse, H.M.; Hertweck, C. Variation in physiological host range in three strains of two species of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0199199. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, A.V.; Northfield, T.D. Tropical occurrence and agricultural importance of Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, C.J. Dirt and disease: the ecology of soil fungi and plant fungi that are infectious for vertebrates. In Understanding Terrestrial Microbial Communities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 289–405. [Google Scholar]

- Masiulionis, V.E.; Samuels, R.I. Investigating the biology of leaf-cutting ants to support the development of alternative methods for the control and management of these agricultural pests. Agriculture 2025, 15, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.N.; Feng, G.M. The time-dose-mortality modeling and virulence indices for the two entomophthoralean species Pandora delphacis and P. neoaphidis against the green peach aphid Myzus persicae. Biol. Control 2000, 17, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, D.J.; Keyhani, N.O. Adhesion of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria (Cordyceps) bassiana to substrata. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 5260–5266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-Urquiza, A.; Keyhani, N.O. Action on the surface: entomopathogenic fungi versus the insect cuticle. Insects 2013, 4, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Yao, Y.; Xu, B.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C. Infection process and genome assembly provide insights into the pathogenic mechanism of destructive mycoparasite Calcarisporium cordycipiticola with host specificity. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.L.; He, K.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C. An entomopathogenic fungus exploits its host humoral antibacterial immunity to minimize bacterial competition in the hemolymph. Microbiome 2023, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, S. Cross-talk between immunity and behavior: insights from entomopathogenic fungi and their insect hosts. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 48, fuae003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedrini, N. Molecular interactions between entomopathogenic fungi (Hypocreales) and their insect host: perspectives from stressful cuticle and hemolymph battlefields and the potential of dual RNA sequencing for future studies. Fungal Biol. 2018, 122, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyling, N.V.; Eilenberg, J. Isolation and characterisation of Beauveria bassiana isolates from phylloplanes of hedgerow vegetation. Mycol. Res. 2006, 110, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, S. Entomopathogenic fungal-derived metabolites alter innate immunity and gut microbiota in the migratory locust. J. Pest Sci. 2024, 97, 853–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, C. An iron-binding protein of entomopathogenic fungus suppresses the proliferation of host symbiotic bacteria. Microbiome 2024, 12, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Wei, X.; Fang, W.; Huang, X.; Zhang, X. The secretory protein COA1 enables Metarhizium robertsii to evade insect immune recognition during cuticle penetration. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández-Chávez, M.J.; Pérez-García, L.A.; Niño-Vega, G.A.; Mora-Montes, H.M. Fungal strategies to evade the host immune recognition. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vidhate, R.P.; Dawkar, V.V.; Punekar, S.A.; Giri, A.P. Genomic determinants of entomopathogenic fungi and their involvement in pathogenesis. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 85, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unuofin, J.O.; Okaiyeto, K.; Oluwaseun, O.; Oguntibeju, O.O.; Nwonuma, C.O.; Lebelo, S.L. Chitinases: expanding the boundaries of knowledge beyond routinized chitin degradation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 38045–38060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohlfs, M.; Churchill, A.C.L. Fungal secondary metabolites as modulators of interactions with insects and other arthropods. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2011, 48, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Orozco, R.; Wijeratne, E.M.K.; Gunatilaka, A.A.L.; Stock, S.P.; Molnár, I. Biosynthesis of the cyclooligomer depsipeptide beauvericin, a virulence factor of the entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria bassiana. Chem. Biol. 2008, 15, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, C. A secreted effector with a dual role as a toxin and as a transcriptional factor. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; St Leger, R.J. The Metarhizium anisopliae perilipin homolog MPL1 regulates lipid metabolism, appressorial turgor pressure, and virulence. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 21110–21115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becklin, S.; Jin, Y.; Rebarber, R.; Tenhumberg, B. Spatial dynamics of a pest population with stage-structure and control. J. Math. Biol. 2025, 90, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serva, D.; Krofel, M.; Cerasoli, F.; Biondi, M.; Iannella, M. Supporting reintroduction planning: a framework integrating habitat suitability, connectivity and individual-based modelling. A case study with the Eurasian lynx in the Apennines. Divers. Distrib. 2025, 31, e70024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Yu, L.Q.; Zhang, J.; Han, Y.; Zou, X. A new entomopathogenic fungus, Ophiocordyceps ponerus sp. nov., from China. Phytotaxa 2018, 343, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, J. Spore dispersal—its role in ecology and disease, the British contribution to fungal aerobiology. Mycol. Res. 1996, 100, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custer, G. F. , Bresciani, L., Dini-Andreote, F. Ecological and Evolutionary Implications of Microbial Dispersal. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 855859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trail, F. , Gaffoor, I., Vogel, S. Ejection Mechanics and Trajectory of the Ascospores of Gibberella zeae (Anamorph Fusarium graminearum). Fungal Genet. Biol. 2005, 42, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snyder, R. E. , Chesson, P. Local Dispersal Can Facilitate Coexistence in the Presence of Permanent Spatial Heterogeneity. Ecol. Lett. 2010, 6, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, V. , Ranius, T., Snäll, T. Epiphyte Metapopulation Dynamics Are Explained by Species Traits, Connectivity, and Patch Dynamics. Ecology 2012, 93, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udayababu, P. , Sunil, Z. Evaluation of Entomopathogenic Fungi for the Management of Tobacco Caterpillar Spodoptera litura (Fabricius). Indian J. Plant Prot. 2012, 40, 214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Muok, A. R. , Claessen, D., Briegel, A. Microbial Hitchhiking: How Streptomyces Spores Are Transported by Motile Soil Bacteria. ISME J. 2021, 15, 2591–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golan, J. J. , Pringle, A. Long-Distance Dispersal of Fungi. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nitayavardhana, S. , Rakshit, S. K., Grewell, D., Van Leeuwen, J., Khanal, S. K. Ultrasound Improved Ethanol Fermentation from Cassava Chips in Cassava-Based Ethanol Plants. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 2741–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santi, L. , Silva, W. O. B., Silva, C. P., Beys da Silva, W. O., Schrank, A., Vainstein, M. H. The Entomopathogen Metarhizium anisopliae Can Modulate the Secretion of Lipolytic Enzymes in Response to Different Substrates Including Components of Arthropod Cuticle. Fungal Biol. 2010, 114, 911–916. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, F. C. , Martinelli, A. H., John, E. B., Ligabue-Braun, R. Microbial Hydrolytic Enzymes: Powerful Weapons Against Insect Pests. Microbes for Sustainable Insect Pest Management: Hydrolytic Enzyme; Secondary Metabolite 2021, 2, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Amiri-Besheli, B. , Khambay, B., Cameron, S., Deadman, M. L., Butt, T. M. Inter- and Intra-Specific Variation in Destruxin Production by Insect Pathogenic Metarhizium spp. and Its Significance to Pathogenesis. Mycol. Res. 2000, 104, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. R. , Hu, Q. B., Yu, X. Q., Ren, S. X. Effects of Destruxins on Free Calcium and Hydrogen Ions in Insect Hemocytes. Insect Sci. 2014, 21, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zdybicka-Barabas, A. , Stączek, S., Kunat-Budzyńska, M., Cytryńska, M. Innate Immunity in Insects: The Lights and Shadows of Phenoloxidase System Activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J. , Feng, Y., Zou, X., Zhou, Y., Cao, W. Transcriptome and Proteome Analyses Reveal Genes and Signaling Pathways Involved in the Response to Two Insect Hormones in the Insect-Fungal Pathogen Hirsutella satumaensis. mSystems 2024, 9, e00166–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ost, K. S. , Round, J. L. Commensal Fungi in Intestinal Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, C. , Zhang, L., Li, Y., Wang, Y., Li, J., Zhang, X. The Symbiont Acinetobacter baumannii Enhances the Insect Host Resistance to Entomopathogenic Fungus Metarhizium anisopliae. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, G. , Lai, Y., Wang, G., Chen, X., Li, F., Wang, S., Jin, D., Peng, Y., Lin, Z. Insect Pathogenic Fungus Interacts with the Gut Microbiota to Accelerate Mosquito Mortality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 5994–5999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, J. , Zou, X., Yu, J., Zhou, Y. The Conidial Mucilage, Natural Film Coatings, Is Involved in Environmental Adaptability and Pathogenicity of Hirsutella satumaensis Aoki. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, H. , Wang, C., Zhang, S., Lin, Z., Wang, L., Luo, L. Altered Immunity in Crowded Mythimna separata Is Mediated by Octopamine and Dopamine. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, F. P. , Fávero, A. C., de Castro, É. C., de Moraes, L. A., Rodrigues, F. Å., Lourenção, A. L., Furtado, E. L., Quecine, M. C., Azevedo, J. L., Pizzirani-Kleiner, A. A. Fungal Phytopathogen Modulates Plant and Insect Responses to Promote Its Dissemination. ISME J. 2021, 15, 3522–3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, S. , Wang, M., Li, H., Guo, X., Zhang, Y., Chen, X. Insect-Microorganism Interaction Has Implicates on Insect Olfactory Systems. Insects 2022, 13, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, S. , Sun, Y., Chen, H., Wang, C. Suppression of the Insect Cuticular Microbiomes by a Fungal Defensin to Facilitate Parasite Infection. ISME J. 2023, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbot, P. Defense in Social Insects, Diversity, Division of Labor, and Evolution. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2022, 67, 407–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, Y. , Nakamura, Y., Yoshida, M., Sakamoto, K., Matsumoto, S., Imanishi, S., Yamakawa, M. Comparative Analysis of Seven Types of Superoxide Dismutases for Their Ability to Respond to Oxidative Stress in Bombyx mori. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2170. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. , Wang, L., Li, Y., Wang, M., Yang, Y., Wang, Y., Zhang, X., Cuthbertson, A. G. S., Qiu, B. Impact of Beauveria bassiana on Antioxidant Enzyme Activities and Metabolomic Profiles of Spodoptera frugiperda. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2023, 198, 107929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A. , Nair, S. Epigenetic Processes in Insect Adaptation to Environmental Stress. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2024, 7, 101294. [Google Scholar]

- Heidel-Fischer, H. M. , Vogel, H. Molecular Mechanisms of Insect Adaptation to Plant Secondary Compounds. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 8, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q. , Ren, M., Liu, X., Xia, H., Chen, K. Peptidoglycan Recognition Proteins in Insect Immunity. Mol. Immunol. 2019, 106, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahrestani, P. , Müller, P., Wertheim, B., van Doorn, G. S. Sexual Dimorphism in Drosophila melanogaster Survival of Beauveria bassiana Infection Depends on Core Immune Signaling. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, T. , Chang, X., Sen, S., Ye, G. Downregulation and Mutation of a Cadherin Gene Associated with Cry1Ac Resistance in the Asian Corn Borer, Ostrinia furnacalis (Guenée). Toxins 2014, 6, 2676–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qayyum, M. A. , Wakil, W., Arif, M. J., Sahi, S. T., Dunlap, C. A. Infection of Helicoverpa armigera by Endophytic Beauveria bassiana Colonizing Tomato Plants. Biol. Control 2015, 90, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamisile, B. S. , Dash, C. K., Akutse, K. S., Keppanan, R., Wang, L. Fungal Endophytes: Beyond Herbivore Management. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakil, W. , Tahir, M., Al-Sadi, A. M., Shapiro-Ilan, D. Interactions between Two Invertebrate Pathogens: An Endophytic Fungus and an Externally Applied Bacterium. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 522368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, W. , Zhang, J., Zhang, X., Li, C., Wang, L., Li, D., Li, T., Wang, M. Endophytic Colonization of Beauveria bassiana Enhances Drought Stress Tolerance in Tomato via “Water Spender” Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 11949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. J. , Goettel, M. S., Gillespie, D. R. Evaluation of Lecanicillium longisporum, Vertalec® for Simultaneous Suppression of Cotton Aphid, Aphis gossypii, and Cucumber Powdery Mildew, Sphaerotheca fuliginea, on Potted Cucumbers. Biol. Control 2008, 45, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, L. R. , Ownley, B. H. Can We Use Entomopathogenic Fungi as Endophytes for Dual Biological Control of Insect Pests and Plant Pathogens? Biol. Control 2018, 116, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqar, S. , Bhat, A. A., Khan, A. A. Endophytic Fungi: Unravelling Plant-Endophyte Interaction and the Multifaceted Role of Fungal Endophytes in Stress Amelioration. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2024, 206, 108174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamisile, B. S. , Akutse, K. S., Siddiqui, J. A., Xu, Y. Model Application of Entomopathogenic Fungi as Alternatives to Chemical Pesticides: Prospects, Challenges, and Insights for Next-Generation Sustainable Agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 741804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leger, R. J. The Evolution of Complex Metarhizium-Insect-Plant Interactions. Fungal Biol. 2024, 128, 2513–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alquichire-Rojas, S. , Escobar, E., Bascuñán-Godoy, L., González-Teuber, M. Root Symbiotic Fungi Improve Nitrogen Transfer and Morpho-Physiological Performance in Chenopodium quinoa. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1386234. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. , Yang, Y., Wang, B. Entomopathogenic Fungi Beauveria bassiana and Metarhizium anisopliae Play Roles of Maize (Zea mays) Growth Promoter. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 15706. [Google Scholar]

- Imoulan, A. , El Meziane, A., Alaoui, A., El Aouami, A., El Khourassi, A., El Harti, A., El Alaoui, A. Entomopathogenic Fungus Beauveria: Host Specificity, Ecology and Significance of Morpho-Molecular Characterization in Accurate Taxonomic Classification. J. Asia-Pac. Entomol. 2017, 20, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barelli, L. , Moonjely, S., Behie, S. W., Bidochka, M. J. Fungi with Multifunctional Lifestyles: Endophytic Insect Pathogenic Fungi. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016, 90, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKinnon, A. C. , Saari, S., Moran-Diez, M. E., Meyling, N. V., Raad, M., Glare, T. R. Beauveria bassiana as an Endophyte: A Critical Review on Associated Methodology and Biocontrol Potential. BioControl 2017, 62, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, L. , Li, Y., Li, J., Zhang, X., Wang, C. Endophytic Beauveria bassiana Promotes Plant Biomass Growth and Suppresses Pathogen Damage by Directional Recruitment. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1227269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noman, A. , Aqeel, M., Qasim, M., Haider, I., Lou, Y. Plant-Insect-Microbe Interaction: A Love Triangle between Enemies in Ecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699, 134181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, M. , Chen, Q., Guo, Q., Liu, B., Ying, S. Assessment of Beauveria bassiana for the Biological Control of Corn Borer, Ostrinia furnacalis, in Sweet Maize by Irrigation Application. BioControl 2023, 68, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzhuppillymyal-Prabhakarankutty, L. , Rajendran, G., Karthikeyan, G., Senthil-Nathan, S., Al-Dhabi, N. A., Arasu, M. V., Duraipandiyan, V., Samiyappan, R. Endophytic Beauveria bassiana Promotes Drought Tolerance and Early Flowering in Corn. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eilenberg, J. , Hajek, A., Lomer, C. Suggestions for Unifying the Terminology in Biological Control. BioControl 2001, 46, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D. C. , Zhan, J. S., Xie, L. H. Problems, Challenges and Future of Plant Disease Management: From an Ecological Point of View. J. Integr. Agric. 2016, 15, 705–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G. , Li, Y., Zhang, Y., Dong, S., Chen, S., Wang, M., Sun, C., Khashnobish, A., Li, Y., Wang, C. Biosynthesis of Antibiotic Leucinostatins in Bio-Control Fungus Purpureocillium lilacinum and Their Inhibition on Phytophthora Revealed by Genome Mining. PLoS Pathog. 2016, 12, e1005685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, F. M. , Silva, M., Molina-Cruz, A., Barillas-Mury, C. Molecular Mechanisms of Insect Immune Memory and Pathogen Transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2022, 18, e1010939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ligne, L. , Van den Bulcke, J., Van Acker, J., De Baets, B. Analysis of Spatio-Temporal Fungal Growth Dynamics under Different Environmental Conditions. IMA Fungus 2019, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L. , Fasoyin, O. E., Molnár, I., Xu, Y. Secondary Metabolites from Hypocrealean Entomopathogenic Fungi: Novel Bioactive Compounds. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2020, 37, 1181–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parveen, S. S. , Rashtrapal, P. S. Integrated Pest Management Strategies Using Endophytic Entomopathogenic Fungi. Plant Sci. Today 2024, 11, 568–574. [Google Scholar]

- Bartling, M. T. , Brandt, A., Hollert, H., Vilcinskas, A. Current Insights into Sublethal Effects of Pesticides on Insects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrick, N. J. , Cloyd, R. A. Direct and Indirect Effects of Pesticides on the Insidious Flower Bug (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae) under Laboratory Conditions. J. Econ. Entomol. 2017, 110, 931–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quesada-Moraga, E. , Landa, B. B., Muñoz-Ledesma, F., Santiago-Álvarez, C. Key Role of Environmental Competence in Successful Use of Entomopathogenic Fungi in Microbial Pest Control. J. Pest Sci. 2024, 97, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, C.; Schmidt, B.; Stephan, D.; Meyer, V. Investigation of the interface of fungal mycelium composite building materials by means of low-vacuum scanning electron microscopy. J. Microsc. 2024, 294, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warmink, J.A.; Elsas, J.D. van. Migratory response of soil bacteria to Lyophyllum sp. strain Karsten in soil microcosms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 2820–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuno, S.; Remer, R.; Chatzinotas, A.; Harms, H.; Wick, L.Y. Use of mycelia as paths for the isolation of contaminant-degrading bacteria from soil. Microb. Biotechnol. 2012, 5, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, N.; Zhang, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, T.; Yang, H.; Luo, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Alternative transcription start site selection in Mr-OPY2 controls lifestyle transitions in the fungus Metarhizium robertsii. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocking, E.C. Endophytic colonization of plant roots by nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Plant Soil 2003, 252, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behie, S.W.; Bidochka, M.J. Ubiquity of insect-derived nitrogen transfer to plants by endophytic insect-pathogenic fungi: an additional branch of the soil nitrogen cycle. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 1553–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilger-Casagrande, M.; Lima, R.; Andrade, G.; Ribeiro, A.; Campos, E.V.R.; Fraceto, L.F.; Oliveira, H.C.; de Oliveira, J.L. Beauveria bassiana biogenic nanoparticles for the control of Noctuidae pests. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 1325–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarathchandra, S.U.; Ghani, A.; Yeates, G.W.; Burch, G.; Cox, N.R. Effect of nitrogen and phosphate fertilisers on microbial and nematode diversity in pasture soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2001, 33, 953–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Sun, M.H.; Liu, X.Z.; Che, Y.S. Effects of carbon concentration and carbon to nitrogen ratio on the growth and sporulation of several biocontrol fungi. Mycol. Res. 2007, 111, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reingold, V.; Halperin, O.; Shalaby, S.; Dubov, D.; Freilich, S.; Zakin, V.; Golani, Y.; Dubey, A.; Prasad, R.; Bhat, B.N.; Rav-David, D.; Sharon, A.; Freeman, S. Transcriptional reprogramming in the entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium brunneum and its aphid host Myzus persicae during the switch between saprophytic and parasitic lifestyles. BMC Genomics 2024, 25, 917. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gu, F.T.; Li, H.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Metabolic outcomes of Cordyceps fungus and Goji plant polysaccharides during in vitro human fecal fermentation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 350, 123019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booi, H.N.; Zhang, T.; Li, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L. Evidence to support cultivated fruiting body of Ophiocordyceps sinensis (Ascomycota)’s role in relaxing airway smooth muscle. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2025, 336, 118727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. Innovative mycelium-based food: Advancing one health through nutritional insights and environmental sustainability. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, B.; Li, S. Cordyceps as an herbal drug for anti-aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 134, 111142. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Agrocybe cylindracea polysaccharides repair the intestinal mucosal barrier in DSS-induced colitis by modulating the gut microbiota-macrophage axis. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness 2025, 15, in, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J. Cordycepin affects Streptococcus mutans biofilm and interferes with its metabolism. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, C.M.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, T.T. Low-glycemic index cookies supplemented with Cordyceps militaris substrate: nutritional values, physicochemical properties, antioxidant activity, bioactive constituents, and bioaccessibility. Food Chem. X 2025, 23, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.Q.; Van Pham, T.; Andriana, Y.; Truong, M.N. Cordyceps militaris-derived bioactive gels: therapeutic and anti-aging applications in dermatology. Gels 2025, 11, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devi, W.M.; Saha, H.; Irungbam, S.; Saha, R.K. A novel approach in valorization of spent mushroom substrate of Cordyceps militaris as in-feed antibiotics in Labeo rohita against Aeromonas hydrophila infection. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 62305–62314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y. The composition and function of bacterial communities in Bombyx mori (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae) changed dramatically with infected fungi: a new potential to culture Cordyceps cicadae. Insect Mol. Biol. 2024, 33, 613–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Fermentation design and process optimization strategy based on machine learning. BioDesign Res. 2025, 7, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacey, L.A.; Grzywacz, D.; Shapiro-Ilan, D.I.; Frutos, R.; Brownbridge, M.; Goettel, M.S. Insect pathogens as biological control agents: Back to the future. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2015, 132, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, P.K.; Singh, V.; Singh, R.; Singh, R. Physio-biochemical insights of endophytic microbial community for crop stress resilience: an updated overview. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 5, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, F.E.; Meyling, N.V.; Luangsa-ard, J.J.; Blackwell, M. Fungal entomopathogens: new insights on their ecology. Fungal Ecol. 2009, 2, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, T.C.; Nauen, R. IRAC: Mode of action classification and insecticide resistance management. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2015, 121, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Defense and inhibition integrated mesoporous nanoselenium delivery system against tomato gray mold. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Faria, M.R.; Wraight, S.P. Mycoinsecticides and mycoacaricides: a comprehensive list with worldwide coverage and international classification of formulation types. Biol. Control 2007, 43, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, A.M.; Hashem, A.H.; Abd-Elsalam, K.A.; Attia, M.S. Biodiversity of fungal endophytes. In Fungal Endophytes Volume I: Biodiversity and Bioactive Materials; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, R.H.; Anslan, S.; Bahram, M.; Wurzbacher, C.; Baldrian, P.; Tedersoo, L. Mycobiome diversity: high-throughput sequencing and identification of fungi. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias-Aravena, M.; Altimira, F.; Gutiérrez, D.; Ling, J.; Tapia, E. Identification of exoenzymes secreted by entomopathogenic fungus Beauveria pseudobassiana RGM 2184 and their effect on the degradation of cocoons and pupae of quarantine pest Lobesia botrana. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borsato, N.D.; Morais, D.K.; Silva, J.C.; Silva, D.B. Identification of potential insect ecological interactions using a metabarcoding approach. PeerJ 2025, 13, e18906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Quantifying potentially suitable geographical habitat changes in chinese caterpillar fungus with enhanced MaxEnt model. Insects 2025, 16, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Xia, Y. Host-pathogen interactions between Metarhizium spp. and locusts. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Gahtyari, N.C.; Chhabra, R.; Kumar, D. Role of microbes in improving plant growth and soil health for sustainable agriculture. Diversity 2020, 12, 207–256. [Google Scholar]

- Tarfeen, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Microbial remediation: a promising tool for reclamation of contaminated sites with special emphasis on heavy metal and pesticide pollution: a review. Processes 2022, 10, 1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanuja, A.; Rahman, S.J.; Rajanikanth, P.; Bhat, B.N. Combined effect of entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae (Metschinkoff) and novel insecticides on the cellular and humoral immune mechanisms of Spodoptera litura (Fabricius). Plant Arch. 2025, 25, 1234–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Yildiz, M.; Romanazzi, G.; Oguz, M.C. Bio-based strategies for biotic and abiotic stress management in sustainable agriculture. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 15, 1536460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Beauveria bassiana induces strong defense and increases resistance in tomato to Bemisia tabaci. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorahinobar, M.; Eslami, S.; Shahbazi, S.; Najafi, J. A mutant Trichoderma harzianum improves tomato growth and defense against Fusarium wilt. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2025, 172, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, V.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, D.; Chhabra, R.; Kumar, D. Isolation, characterisation of major secondary metabolites of the Himalayan Trichoderma koningii and their antifungal activity. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2014, 47, 1063–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranco, L.; Fiorilli, V.; Venice, F.; Bonfante, P. Strigolactones cross the kingdoms: plants, fungi, and bacteria in the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 2175–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, P.K.; Singh, V.; Singh, R.; Singh, R. Integrative approaches to improve litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) plant health using bio-transformations and entomopathogenic fungi. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kleber, M.; Sollins, P.; Sutton-Grier, A. Dynamic interactions at the mineral-organic matter interface. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2021, 2, 402–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Species diversity and vertical distribution characteristics of entomogenous fungi in soils of northern Gaoligong Mountains. J. Yunnan Agric. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

| Cordyceps fungi | Biocontrol fungi | |

|---|---|---|

| Morphological characteristics | Fruiting bodies are formed, and ascospores are released through the perithecia [17]. | The mycelium is white or green, and the conidia are arranged in chains [18]. |

| Infection process | Spores invade the host → Hyphae slowly occupy the body cavity → Fruiting body formation after host death (weeks to months) [30]. | Spore attachment host → Secretase breaks down the body wall → Hyphae proliferate to kill the host (3-7 d) → Secondary transmission of the spores is facilitated through insect carcasses [31]. |

| Major metabolites | Cordycepin [32], adenosine [33], polysaccharide [34], ergosterol [35], etc | Beauvericin [36], cyclic peptide toxins [36], etc |

| Core function | Edible and medicinal dual-purpose: immunoregulation [37], antineoplastic [38], antioxidant [39], etc. | Agriculture and forest pest control: broad-spectrum insecticidal and fungicidal activity [40]. |

| Host specificity | Highly specialized (e.g.; C. sinensis only parasites bat moth larvae) [40]. | Broad spectrum (Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Homoptera, etc.) [41]. |

| Ecological function | By modulating the populations of specific insects, insect carcasses contribute to soil nitrogen cycling, while decomposed fruiting bodies participate in soil carbon cycling [42,43,44]. | The capacity for cross-host transmission is robust [45], making it highly suitable for extensive agricultural and forestry pest management programs. |

| Primary application domains | Health supplements [46,47], medicines [48], food processing [46], etc. | Agricultural pest control [41], forest pest management [41,49], etc. |

| Typical products | C. sinensis capsule [50], C. militaris functional beverage [51], C. chanhua wine [52], etc. | M. anisopliae granule [53], B. bassiana agent [54], C. cateniannulata agent [55], etc. |

| Similarities | 1) Both cordyceps fungi and biocontrol fungi participate in ecological balance by parasitizing or inhibiting insects [40,41,44]; 2) Both of them can replace chemical pesticides to reduce environmental pollution [2,41,56]; 3) Genetic engineering, nano-preparation and other technologies can improve the application performance of the two fungi [57,58,59]. |

|

| Relationships | Metabolite complementation: 1) Extracts from cordyceps fungi, including polysaccharides, can serve as synergistic agents for biocontrol agents. 2) Certain biocontrol fungi also contain active compounds with medicinal and edible value. For instance, Bombyx batryticatus, formed by the infection of B. mori L. larvae with B. bassiana, is a rare traditional Chinese medicine [60]. It contains various bioactive components such as proteins, peptides, fatty acids, flavonoids, nucleosides, steroids, legumes, and polysaccharides [61,62]. Both cordyceps fungi and biocontrol fungi target insects and contribute to sustainable agriculture. Future research should focus on enhancing comprehensive benefits through interdisciplinary approaches, such as gene editing and drug combination. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).