Submitted:

12 July 2025

Posted:

16 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background:

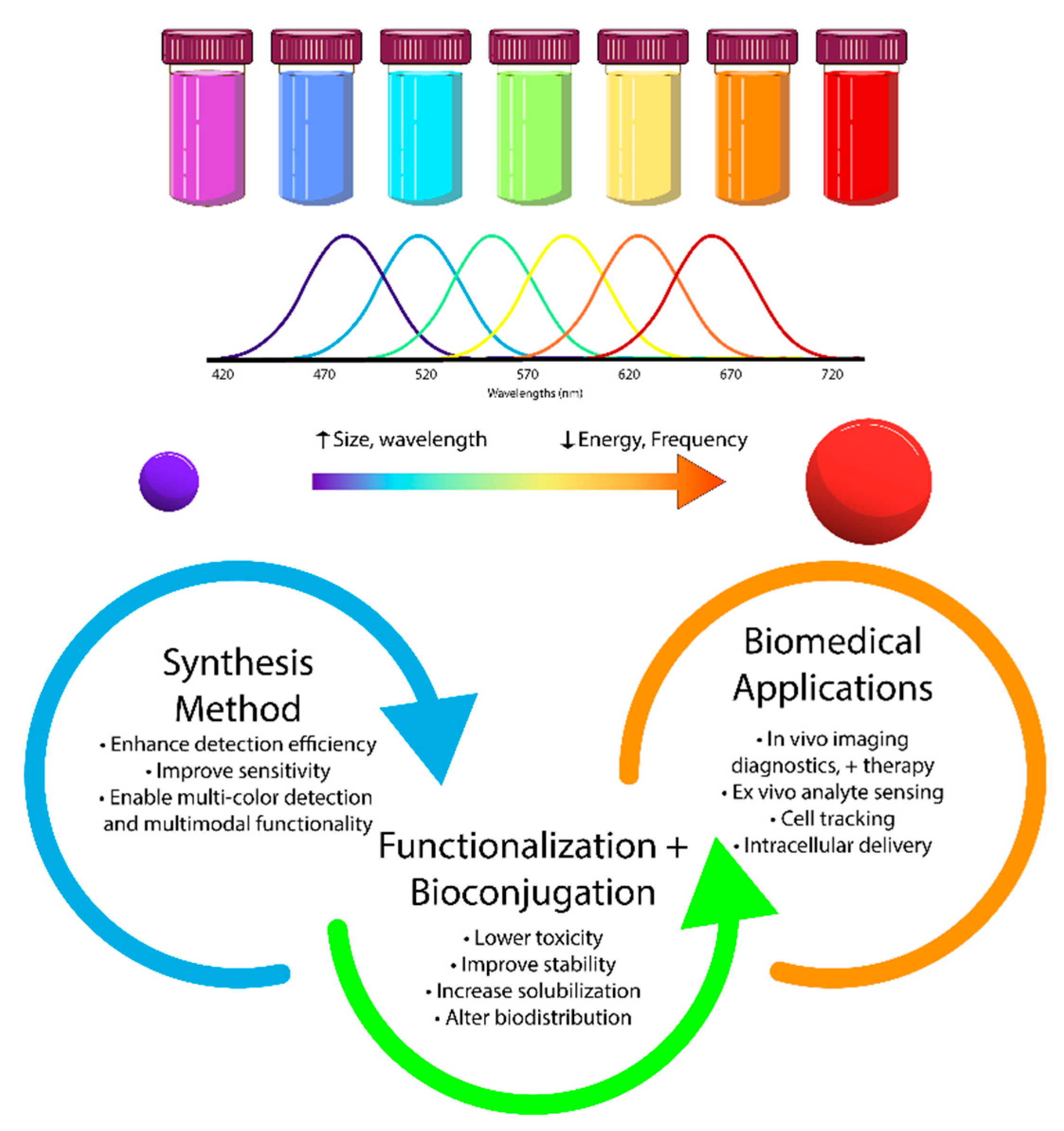

1.1. An In-Depth Examination of Quantum Dots: Properties and Applications in Nanomedicine

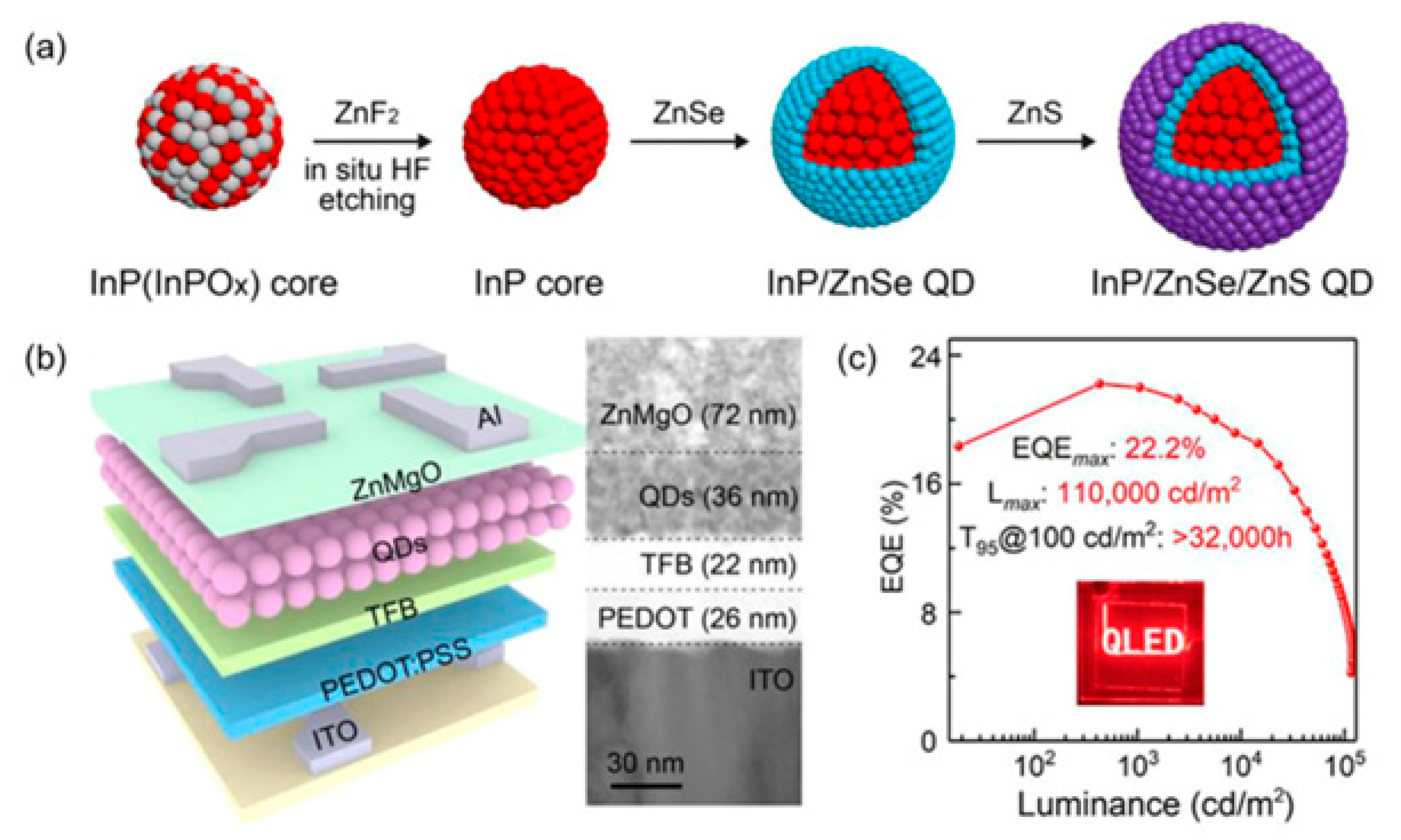

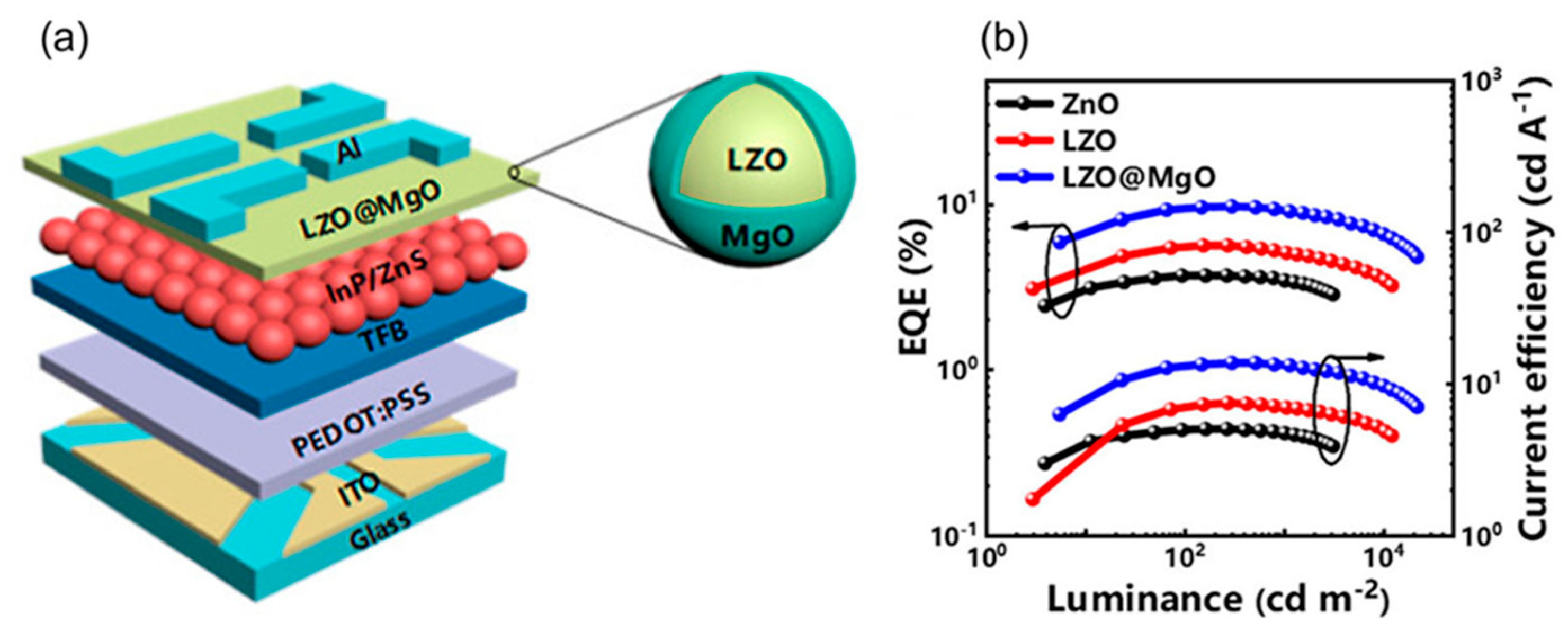

1.1.1. Heavy Metal–Free QD Platforms

1.1.2. Carbon-Based Quantum Dots and Silicon Quantum Dots

1.1.3. Green Synthesis Approaches (Eco-friendly methods)

1.2. The Transformative Role of Quantum Dots in Healthcare and Pharmaceutical Innovation

1.2.1. QD Integration in Point-of-Care Devices

1.2.2. Regulatory and safety considerations for quantum dots

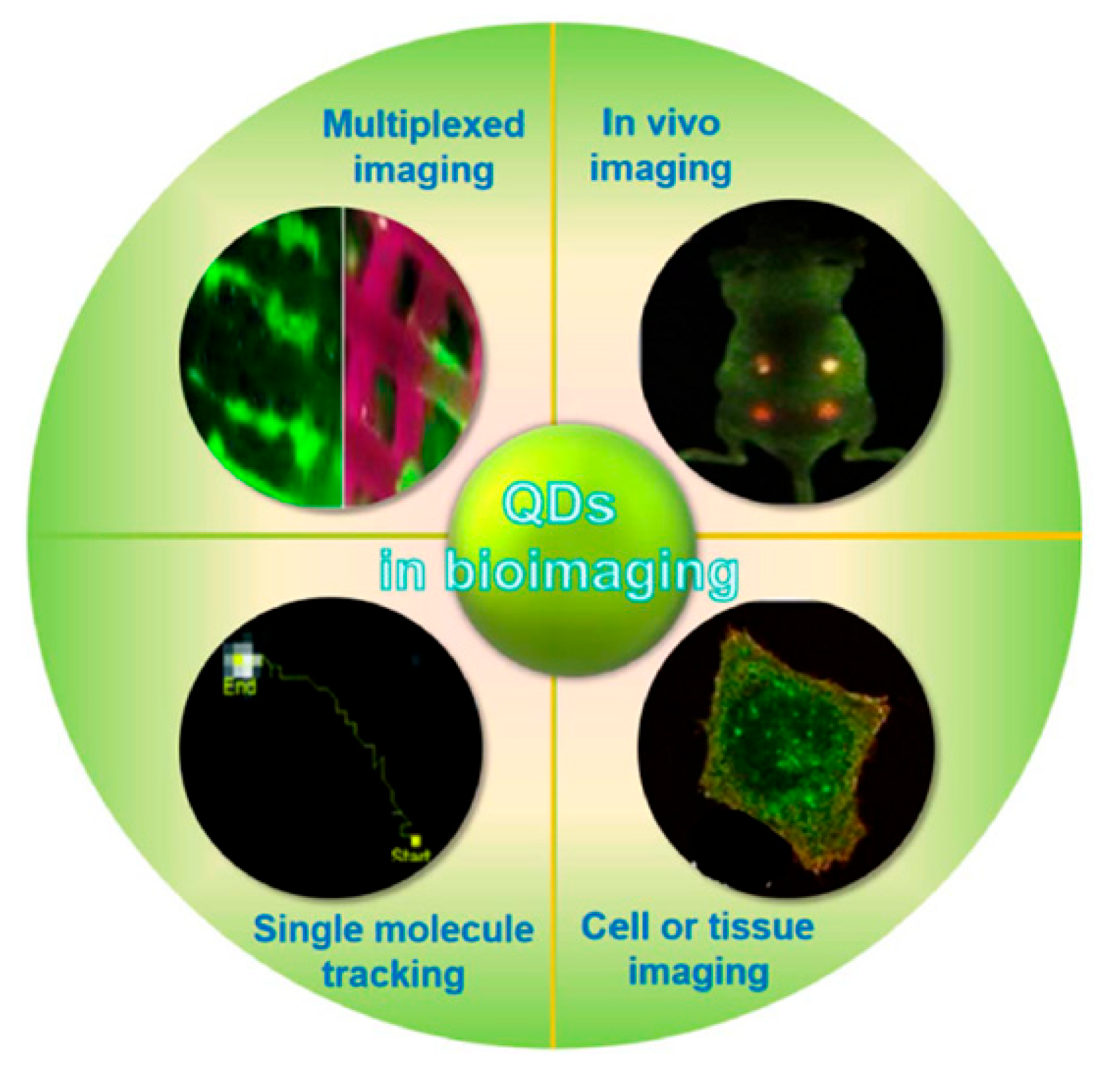

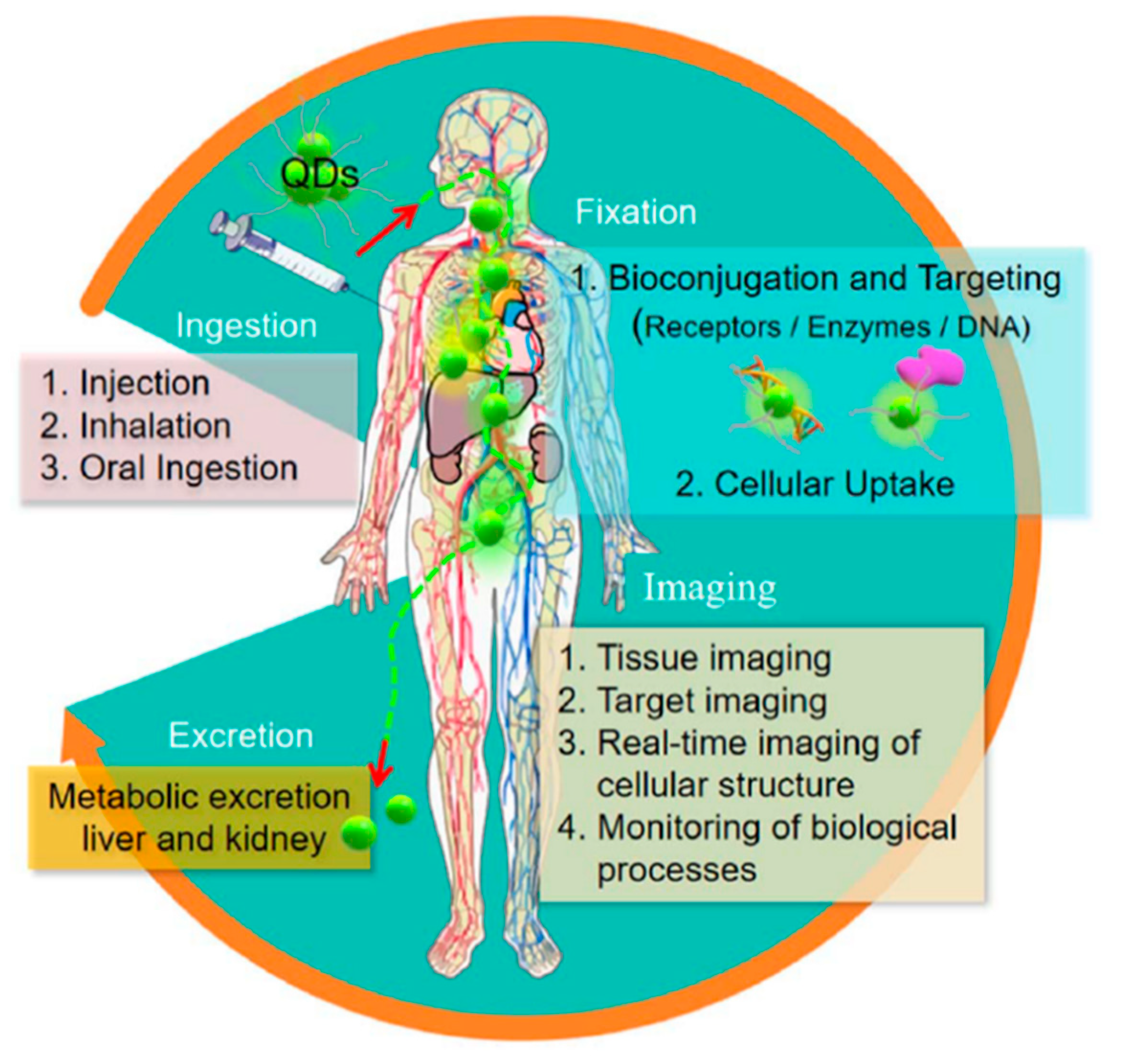

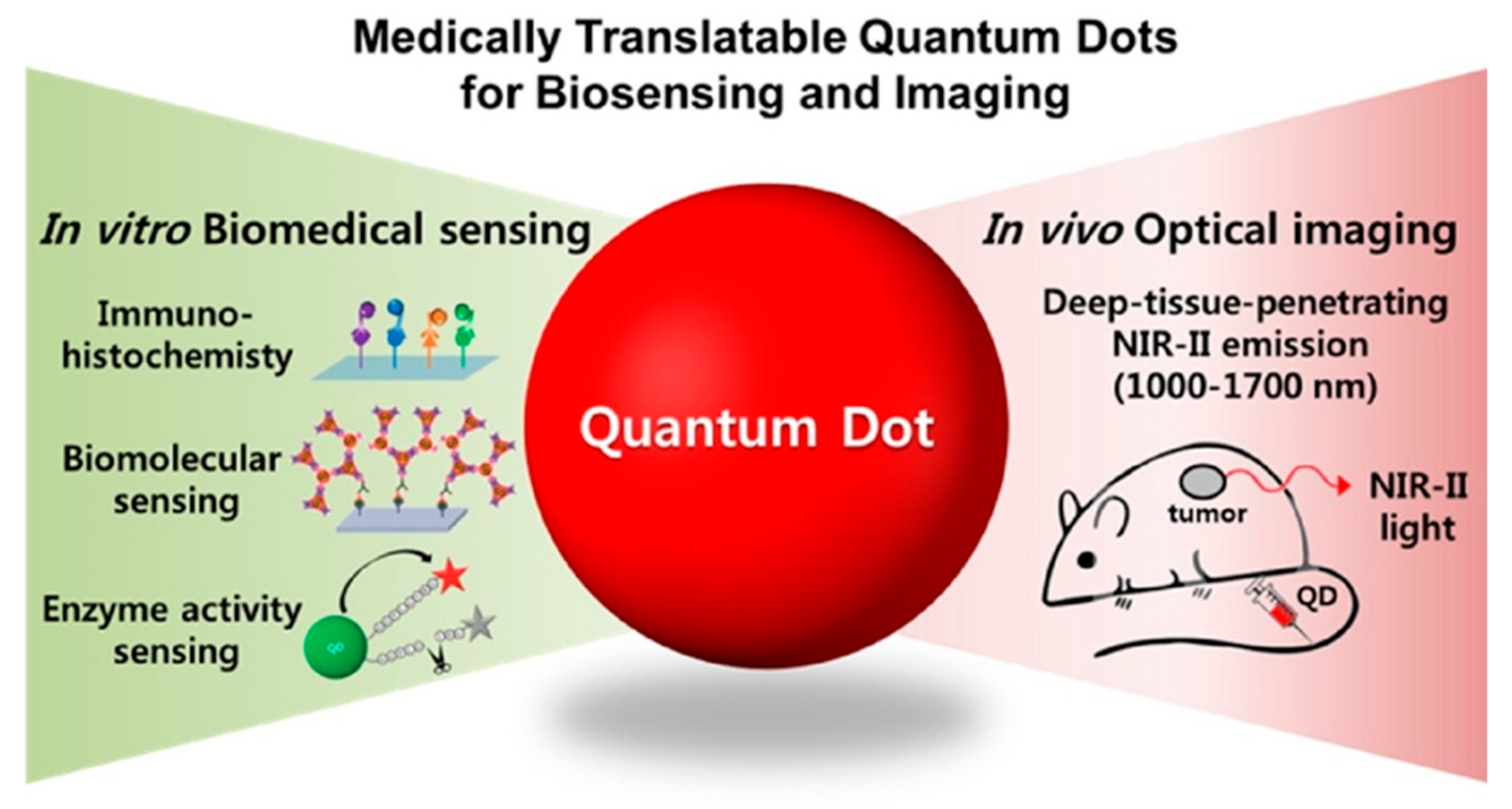

2. Bioimaging Applications

2.1. Advancing Medical Imaging: The Impact of Quantum Dots on Diagnostic Technologies:

2.1.1. NIR-Emitting QD Imaging Probes: Deeper Tissue Imaging

2.1.2. QD-Based Photoacoustic Imaging: Harnessing QD Optical Absorption

2.1.3. Multimodal Imaging: Combining QDs with MRI/PET

2.1.4. AI-Enhanced Hyperspectral QD Imaging: Machine Learning for QD Biomarker Quantification

2.2. Revolutionizing Dental Diagnostics: The Role of Quantum Dots in Imaging Techniques:

2.2.1. Wearable Quantum Dots-Based Biosensors for Real-Time Oral Monitoring

2.2.1.1. Uniqueness of the Oral Environment for QD Biosensing

2.2.1.2. Mouthguard Sensors Functionalized with QDs

2.2.1.3. Retainer and Dental Implant-Based QD Sensors

2.2.1.4. Multiplexing Capability

2.2.1.5. Signal Acquisition and Data Handling

2.2.1.6. Design Challenges and Strategies for Improvement

2.2.1.7. Clinical Integration and Future Perspectives

2.2.2. Quantum Dots Labeling for Stem Cell Tracking in Regenerative Dentistry

2.2.3. Augmented reality Integration in quantum dots Imaging for Dental Procedures

3. Synthesis and Modification of Quantum Dots

3.1. Cutting-Edge Synthesis Techniques for Quantum Dots in Biomedical Contexts:

3.1.1. Green Synthesis of QDs: Plant Extracts, Biogenic Methods

3.1.2. Hybrid Quantum Dot –Gold Nanostar Nanocomposites

3.1.3. QD/MoS₂ Hybrid Nanocomposites

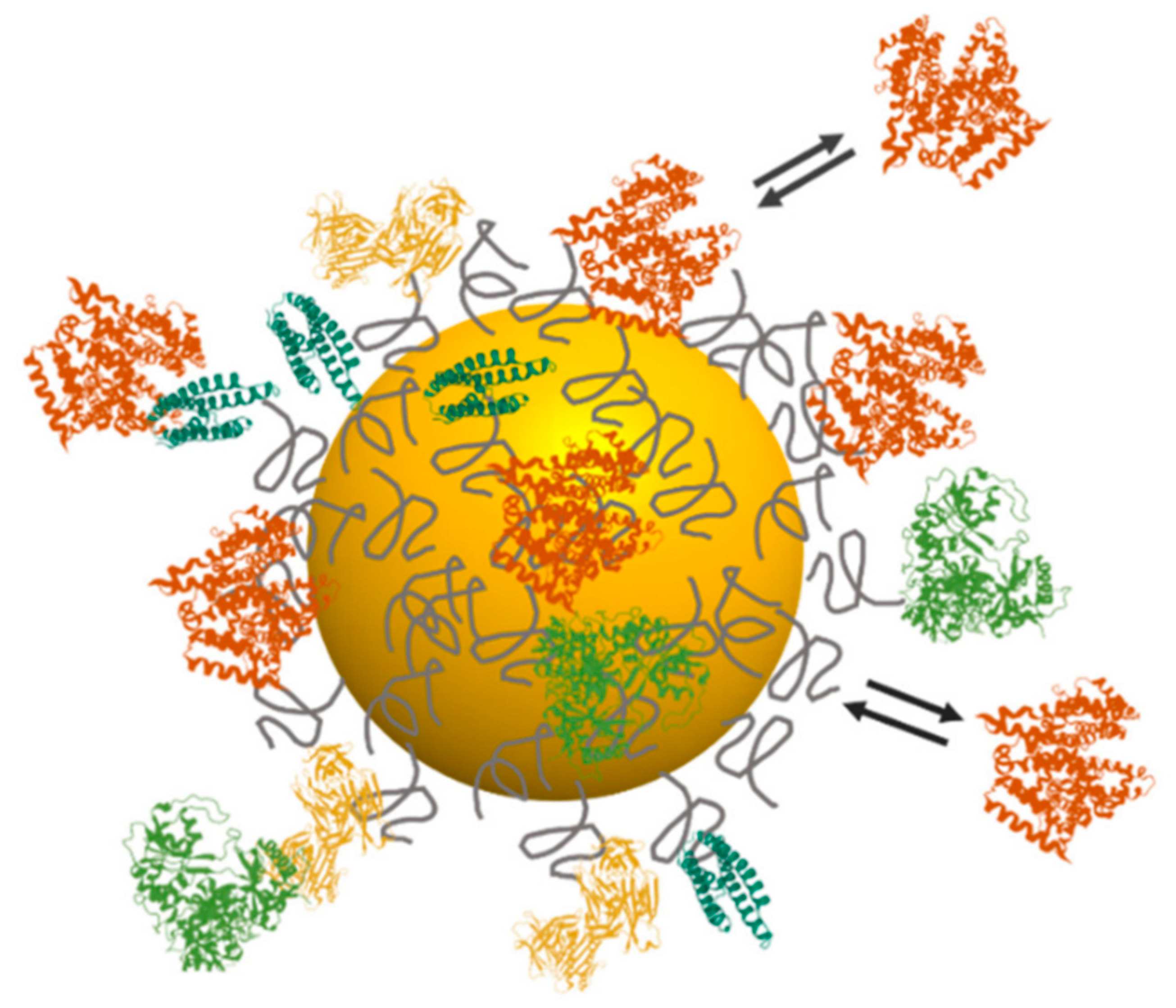

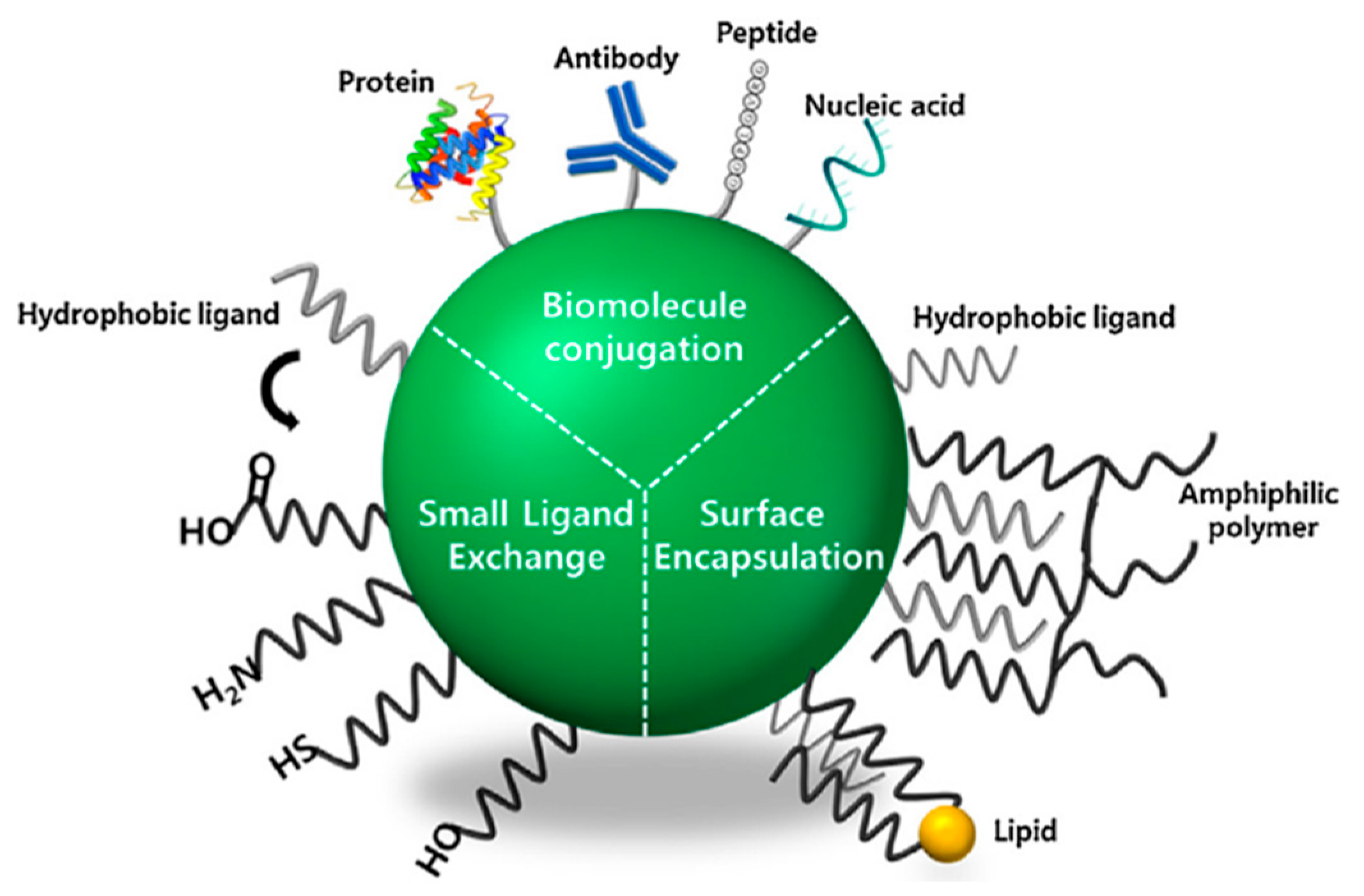

3.2. Optimizing Surface Modifications to Augment the Biocompatibility of Quantum Dots:

3.2.1. Advanced Surface Passivation Techniques

3.2.2. Zwitterionic Polymer-Coated QDs: Minimizing Non-Specific Binding

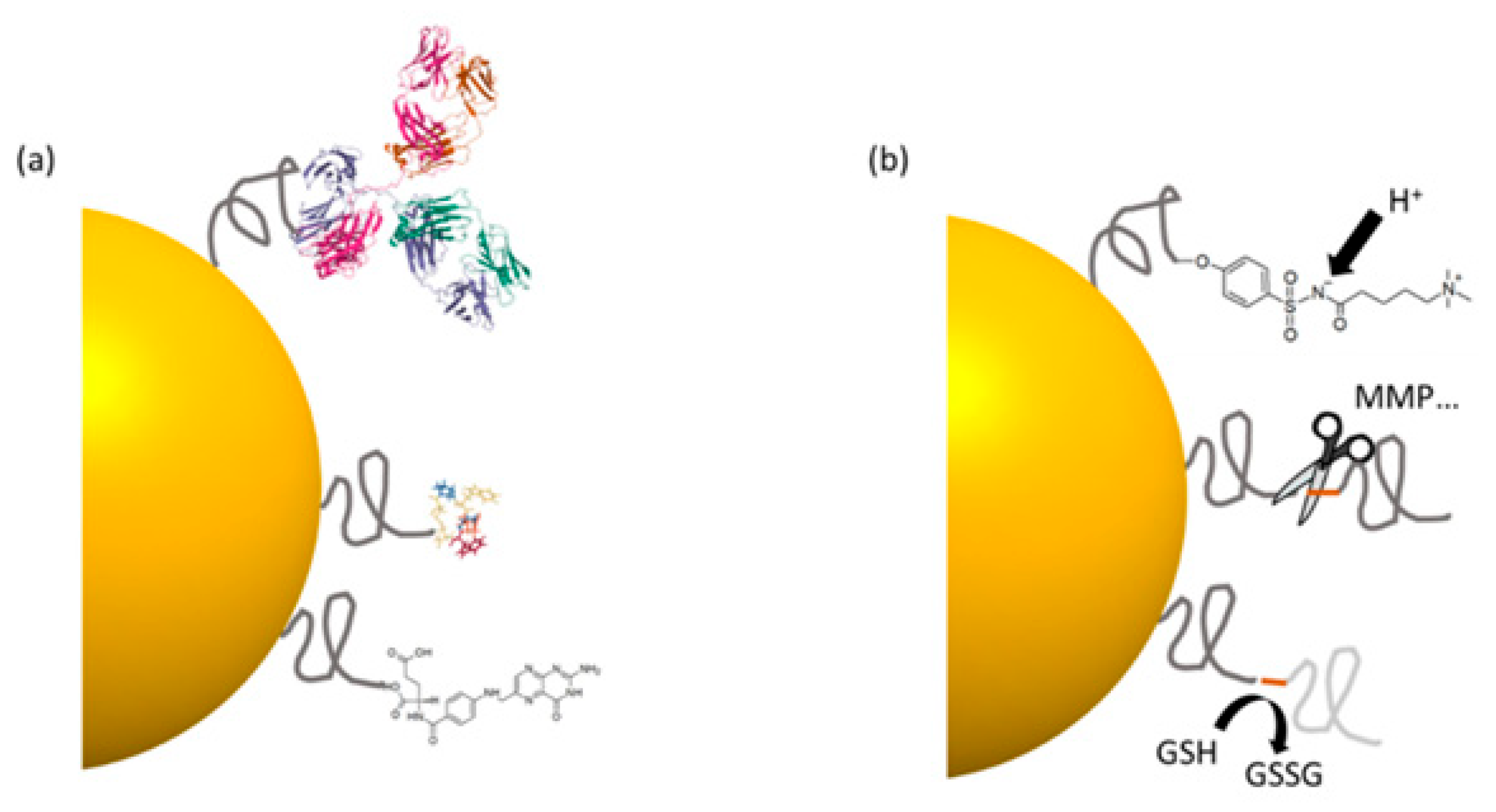

3.2.3. pH-Sensitive and Enzyme-Responsive QD Systems: Smart Delivery

4. Quantum Dots in Drug Delivery

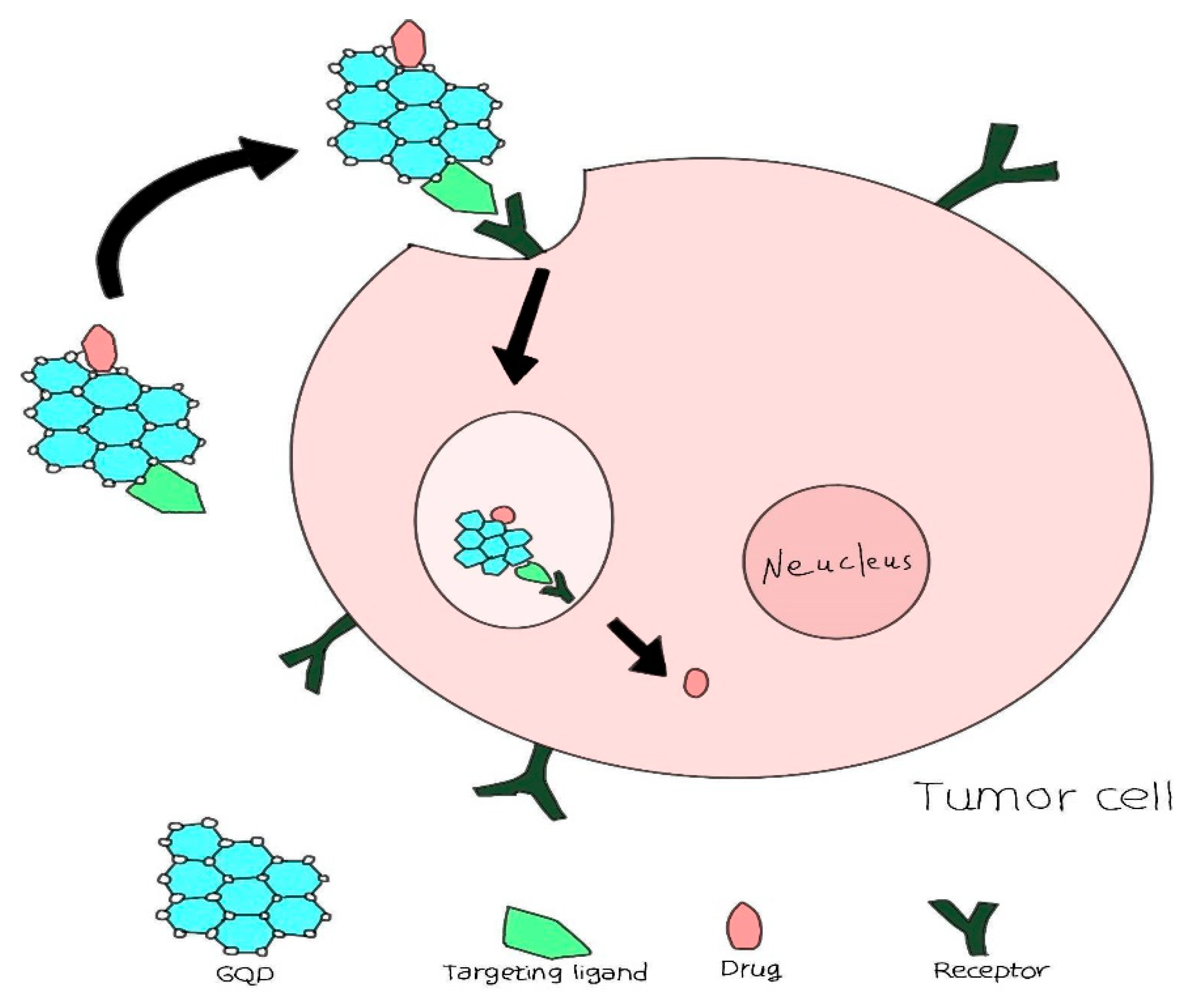

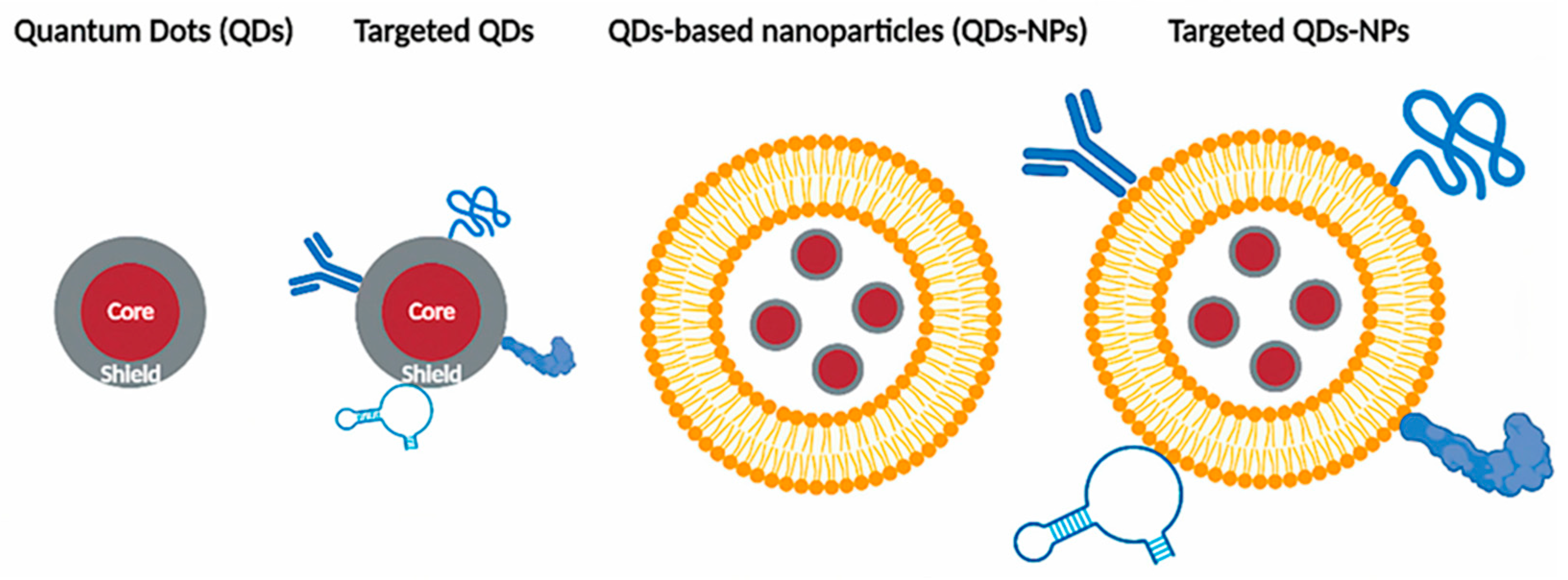

4.1. Harnessing Quantum Dots for Enhanced Precision in Targeted Drug Delivery Systems:

4.2. Innovative Drug Delivery Mechanisms: The Integration of Quantum Dots in Pharmaceutical Applications:

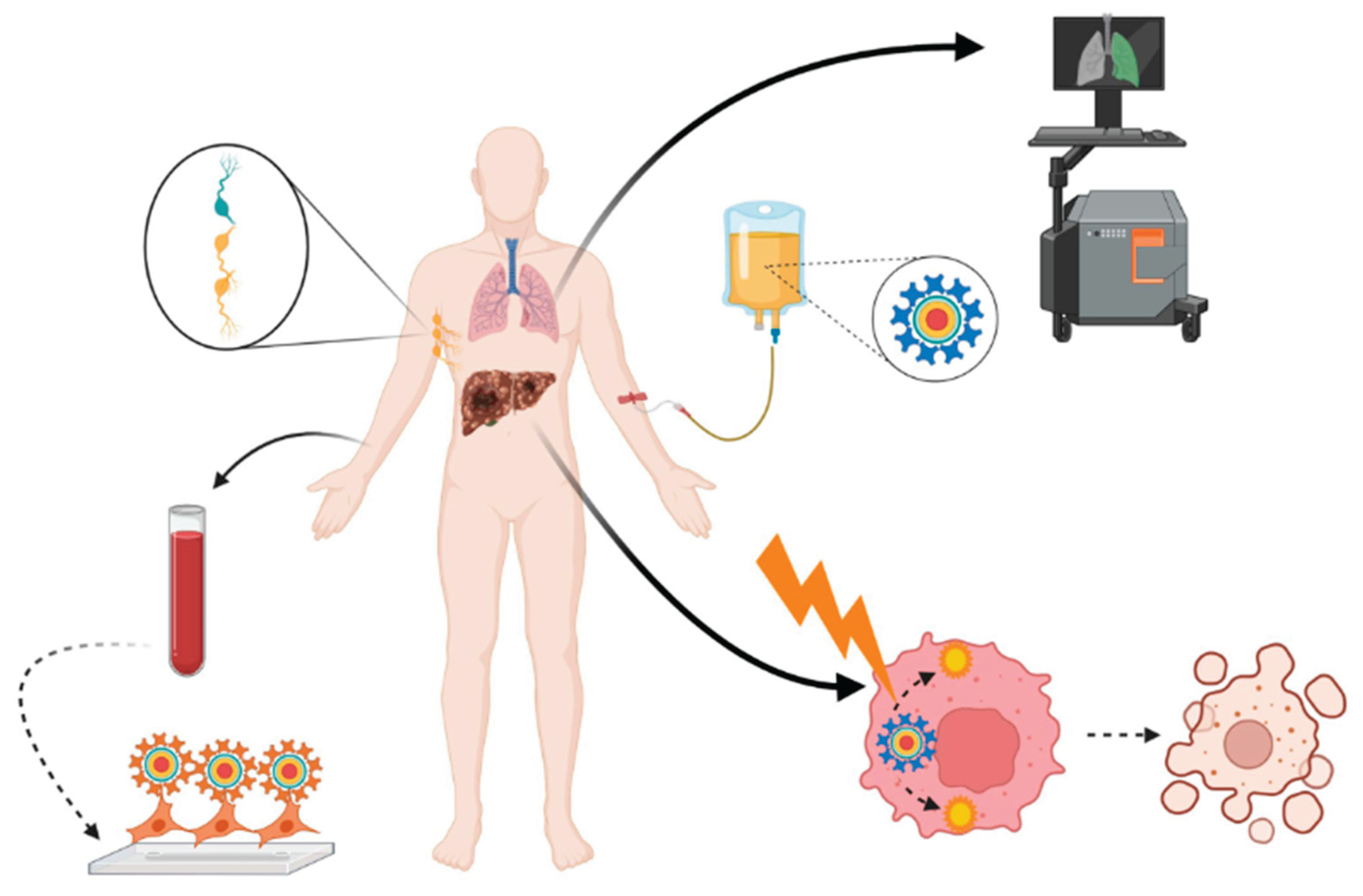

5. Therapeutic Applications

5.1. Innovative Applications of Quantum Dots in Photothermal and Photodynamic Therapeutics:

5.2. Advancing Dental Therapeutics: The Role of Quantum Dots in Treatment Strategies:

5.3. Exploring the Potential of Quantum Dots in Cancer Diagnosis and Therapeutic Interventions:

6. Future prospects and innovations

6.1. Recent Advancements in Quantum Dot Technology: Paving the Way for New Applications:

6.2. Anticipating Breakthroughs: The Future of Quantum Dots in Biomedical Applications:

7. Conclusions

- Unresolved Questions

Funding

List of abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Form |

| 0D | Zero-Dimensional |

| AgBr | Silver Bromide |

| AgNPs | Silver Nanoparticles |

| AKs | Actinic Keratosis |

| AlAs | Aluminum Arsenide |

| AlP | Aluminum Phosphide |

| AlSb | Aluminum Antimonide |

| ASCs | Adipose Tissue-Derived Stem Cells |

| Au NPs | Gold Nanoparticles |

| AuNPs | Gold Nanoparticles |

| AuQDs | Gold Quantum Dots |

| BCCs | Basal Cell Carcinomas |

| Bi QDs | Bismuth Quantum Dots |

| CaTiO₃ | Calcium Titanium Oxide |

| CAs | Contrast Agents |

| CDs | Carbon Dots |

| CQDs | Carbon Quantum Dots |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CsFe₃O₄@Au | Core–Satellite Fe₃O₄@Au Nanoparticles |

| cys-GQDs | Cysteine-Functionalized Graphene Quantum Dots |

| DDA | Dodecyl Amine |

| DLU2-NPs | Nanohybrid Particles Combining Dendron-Bearing Lipids, Quantum Dots, and Magnetic Nanoparticles |

| DNP | Nano Dumbbell |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| EQE | External Quantum Efficiency |

| Fe₃O₄NPs | Iron Oxide Nanoparticles |

| FGS | Fluorescence-Guided Surgery |

| FRET | Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer |

| GQDs | Graphene Quantum Dots |

| GOQDs | Graphene Oxide Quantum Dots |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| HNP | Hybrid Nanoparticle |

| LEDs | Light-Emitting Diodes |

| LNPs | Lipid Nanoparticles |

| MIP | Molecularly Imprinted Polymer |

| MMPs | Matrix Metalloproteinases |

| MOFs | Metal–Organic Frameworks |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| MXene | Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Carbides, Nitrides, or Carbonitrides |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| NIR-II | Near-Infrared II |

| NIR-IIb | Near-Infrared IIb |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| 2PA | Two-Photon Absorption |

| PAI | Photoacoustic Imaging |

| Pc4 | Silicon Phthalocyanine 4 |

| PDT | Photodynamic Therapy |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| PDs | Polymer Dots |

| PEI | Polyethylenimine |

| PL | Photoluminescence |

| PSs | Photosensitizers |

| PTT | Photothermal Therapy |

| P dots | Polymer Dots |

| QDs | Quantum Dots |

| QLEDs | Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes |

| RGD | Arginine-Glycine-Aspartic Acid Peptide |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| SCCs | Squamous Cell Carcinomas |

| SHEDs | Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth |

| TME | Tumor Microenvironment |

| TMDCs | Transition Metal Dichalcogenides |

| TSC | Thiosemicarbazide |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| UV–vis | Ultraviolet–Visible Spectroscopy |

| ZnF₂ | Zinc Fluoride |

| ZnO | Zinc Oxide |

| CdTe | Cadmium Telluride |

| PbS | Lead Sulfide |

| PbSe | Lead Selenide |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| CRISPR/Cas9 | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats / CRISPR-associated protein 9 |

| MinION | Portable Nanopore Sequencer (by Oxford Nanopore Technologies) |

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| fs | Femtosecond |

Statements and Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication

Availability of data and material

Competing interests

Declaration Regarding the Use of AI-Assisted Readability Enhancement

Authors' contributions

Acknowledgments

Authors’ information:

References

- Liu, Q., Zou, J., Chen, Z., He, W., & Wu, W. (2023). Current research trends of nanomedicines. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B, 13(11), 4391–4416. [CrossRef]

- Shin, M. D., Shukla, S., Chung, Y. H., Beiss, V., Chan, S. K., Ortega-Rivera, O. A., Wirth, D. M., Chen, A., Sack, M., Pokorski, J. K., & Steinmetz, N. F. (2020). COVID-19 vaccine development and a potential nanomaterial path forward. Nature Nanotechnology, 15(8), 646–655. [CrossRef]

- Jiao, M., Zhang, P., Meng, J., Li, Y., Liu, C., Luo, X., & Gao, M. (2018). Recent advancements in biocompatible inorganic nanoparticles towards biomedical applications. Biomaterials Science, 6(4), 726–745. [CrossRef]

- McNamara, K., & Tofail, S. a. M. (2016). Nanoparticles in biomedical applications. Advances in Physics X, 2(1), 54–88. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X., Zhang, X., Ren, X., Li, J., Cui, J., Li, L., Wang, S., Wang, Q., & Huang, Y. (2013). Realization of Stranski–Krastanow InAs quantum dots on nanowire-based InGaAs nanoshells. Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 1(47), 7914. [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, A. a. H., Younis, M. A., Alsharidah, M., Rugaie, O. A., & Tawfeek, H. M. (2022). Biomedical applications of Quantum dots: Overview, challenges, and clinical potential. International Journal of Nanomedicine, Volume 17, 1951–1970. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., & Zang, Z. (2022). Advances in perovskite quantum dots and their devices: a new open special issue in materials. Materials, 15(18), 6232. [CrossRef]

- Pons, T., Bouccara, S., Loriette, V., Lequeux, N., Pezet, S., & Fragola, A. (2019). In vivo imaging of single tumor cells in Fast-Flowing bloodstream using Near-Infrared quantum dots and Time-Gated imaging. ACS Nano, 13(3), 3125–3131. [CrossRef]

- Gao, J., Chen, K., Xie, R., Xie, J., Lee, S., Cheng, Z., Peng, X., & Chen, X. (2010). Ultrasmall Near-Infrared Non-cadmium Quantum Dots for in vivo Tumor Imaging. Small, 6(2), 256–261. [CrossRef]

- Kuno, Masaru, and Andrew J. Nozik. "Quantum Dots: A New Class of Fluorescent Probes for Biological Imaging." Nature Reviews Chemistry 4, no. 12 (2020): 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Zhou, Z. K., Yu, Y., Gather, M., & Di Falco, A. (2017, August). Nanophotonic enhanced quantum emitters. In Quantum Nanophotonics (Vol. 10359, pp. 10-15). SPIE. [CrossRef]

- Fang, M., Peng, C., Pang, D., & Li, Y. (2012). Quantum dots for cancer research: current status, remaining issues, and future perspectives. PubMed, 9(3), 151–163. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A. M., Knipe, J. M., Orive, G., & Peppas, N. A. (2019). Quantum dots in biomedical applications. Acta Biomaterialia, 94, 44–63. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Peng, L., Schreier, J., Bi, Y., Black, A., Malla, A., Goossens, S., & Konstantatos, G. (2024). Silver telluride colloidal quantum dot infrared photodetectors and image sensors. Nature Photonics, 18(3), 236–242. [CrossRef]

- Yaghini, E., Turner, H. D., Marois, A. M. L., Suhling, K., Naasani, I., & MacRobert, A. J. (2016). In vivo biodistribution studies and ex vivo lymph node imaging using heavy metal-free quantum dots. Biomaterials, 104, 182–191. [CrossRef]

- Xu, R., Lai, S., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, X. (2024). Research Progress of Heavy-Metal-Free Quantum Dot Light-Emitting diodes. Nanomaterials, 14(10), 832. [CrossRef]

- Wojtynek, N. E., & Mohs, A. M. (2020). Image-guided tumor surgery: The emerging role of nanotechnology. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology, 12(4). [CrossRef]

- McHugh, K. J., Jing, L., Behrens, A. M., Jayawardena, S., Tang, W., Gao, M., Langer, R., & Jaklenec, A. (2018). Biocompatible semiconductor quantum dots as cancer imaging agents. Advanced Materials, 30(18). [CrossRef]

- Kargozar, S., Hoseini, S. J., Milan, P. B., Hooshmand, S., Kim, H., & Mozafari, M. (2020). Quantum Dots: A Review from Concept to Clinic. Biotechnology Journal, 15(12). [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X., Fan, Z., Luo, L., & Wang, L. (2022). Advances and challenges in Heavy-Metal-Free INP Quantum Dot Light-Emitting Diodes. Micromachines, 13(5), 709. [CrossRef]

- Beri, D. (2023). Silicon quantum dots: surface matter, what next? Materials Advances, 4(16), 3380–3398. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, B., & Shirahata, N. (2014). Colloidal silicon quantum dots: synthesis and luminescence tuning from the near-UV to the near-IR range. Science and Technology of Advanced Materials, 15(1), 014207. [CrossRef]

- Kong, J., Wei, Y., Zhou, F., Shi, L., Zhao, S., Wan, M., & Zhang, X. (2024). Carbon Quantum Dots: Properties, preparation, and applications. Molecules, 29(9), 2002. [CrossRef]

- Morozova, S., Alikina, M., Vinogradov, A., & Pagliaro, M. (2020). Silicon Quantum Dots: Synthesis, encapsulation, and application in Light-Emitting diodes. Frontiers in Chemistry, 8. [CrossRef]

- Medina-Berríos, N., Pantoja-Romero, W., Flores, A. L., Vélez, S. C. D., Guadalupe, A. C. M., Mulero, M. T. T., Kisslinger, K., Martínez-Ferrer, M., Morell, G., & Weiner, B. R. (2024). Synthesis and characterization of Carbon-Based quantum dots and doped derivatives for improved andrographolide’s hydrophilicity in drug delivery platforms. ACS Omega. [CrossRef]

- Guan, X., Li, Z., Geng, X., Lei, Z., Karakoti, A., Wu, T., Kumar, P., Yi, J., & Vinu, A. (2023). Emerging Trends of Carbon-Based Quantum Dots: Nanoarchitectonics and Applications. Small, 19(17). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J., Huang, J., Chen, H., Samanta, A., Linnros, J., Yang, Z., & Sychugov, I. (2021). Low-Cost Synthesis of Silicon Quantum Dots with Near-Unity Internal Quantum Efficiency. The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters, 12(37), 8909–8916. [CrossRef]

- Alqutaibi, A. Y., Aljohani, R., Almuzaini, S., & Alghauli, M. A. (2025). Physical–mechanical properties and accuracy of additively manufactured resin denture bases: Impact of printing orientation. Journal of Prosthodontic Research. [CrossRef]

- Baslak, C., Demirel, S., Dogu, S., Ozturk, G., Kocyigit, A., & Yıldırım, M. (2024). Green synthesis capacitor of carbon quantum dots from Stachys euadenia. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy, 43(3). [CrossRef]

- Bressi, V., Ferlazzo, A., Iannazzo, D., & Espro, C. (2021). Graphene Quantum Dots by Eco-Friendly Green Synthesis for Electrochemical Sensing: Recent advances and future Perspectives. Nanomaterials, 11(5), 1120. [CrossRef]

- Desmond, L. J., Phan, A. N., & Gentile, P. (2021). Critical overview on the green synthesis of carbon quantum dots and their application for cancer therapy. Environmental Science Nano, 8(4), 848–862. [CrossRef]

- Gedda, G., Sankaranarayanan, S. A., Putta, C. L., Gudimella, K. K., Rengan, A. K., & Girma, W. M. (2023). Green synthesis of multi-functional carbon dots from medicinal plant leaves for antimicrobial, antioxidant, and bioimaging applications. Scientific Reports, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, A., Tripathi, K. M., Singh, N., Choudhary, S., & Gupta, R. K. (2016). Green synthesis of carbon quantum dots from lemon peel waste: applications in sensing and photocatalysis. RSC Advances, 6(76), 72423–72432. [CrossRef]

- Sarangi, M. K., Padhi, S., Rath, G., Nanda, S. S., & Yi, D. K. (2022). Success of nano-vaccines against COVID-19: a transformation in nanomedicine. Expert Review of Vaccines, 21(12), 1739–1761. [CrossRef]

- Sa-Nguanmoo, N., Namdee, K., Khongkow, M., Ruktanonchai, U., Zhao, Y., & Liang, X. (2021). Review: Development of SARS-CoV-2 immuno-enhanced COVID-19 vaccines with nano-platform. Nano Research, 15(3), 2196–2225. [CrossRef]

- Alphandéry, E. (2022). Nano dimensions/adjuvants in COVID-19 vaccines. Journal of Materials Chemistry B, 10(10), 1520–1552. [CrossRef]

- Mufamadi, M. S. (2020). Nanotechnology shows promise for next-generation vaccines in the fight against COVID-19. MRS Bulletin, 45(12), 981–982. [CrossRef]

- Balkrishna, A., Arya, V., Rohela, A., Kumar, A., Verma, R., Kumar, D., Nepovimova, E., Kuca, K., Thakur, N., Thakur, N., & Kumar, P. (2021). Nanotechnology Interventions in the Management of COVID-19: Prevention, diagnosis and Virus-Like Particle Vaccines. Vaccines, 9(10), 1129. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., Dhawan, A., Karhana, S., Bhat, M., & Dinda, A. K. (2020). Quantum Dots: an emerging tool for Point-of-Care testing. Micromachines, 11(12), 1058. [CrossRef]

- Najib, M. A., Selvam, K., Khalid, M. F., Ozsoz, M., & Aziah, I. (2022). Quantum Dot-Based Lateral Flow Immunoassay as Point-of-Care Testing for Infectious Diseases: A Narrative Review of its Principle and performance. Diagnostics, 12(9), 2158. [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S. M., Kalashgrani, M. Y., Gholami, A., Omidifar, N., Binazadeh, M., & Chiang, W. (2023). Recent advances in quantum Dot-Based lateral flow immunoassays for the rapid, Point-of-Care diagnosis of COVID-19. Biosensors, 13(8), 786. [CrossRef]

- Pelley, J. L., Daar, A. S., & Saner, M. A. (2009). State of academic knowledge on toxicity and biological fate of quantum dots. Toxicological Sciences, 112(2), 276–296. [CrossRef]

- Hardman, R. (2005). A toxicologic review of quantum dots: Toxicity depends on physicochemical and environmental factors. Environmental Health Perspectives, 114(2), 165–172. [CrossRef]

- İlem-özdemir, D., & Santos-Oliveira, R. (2024). Can radiopharmaceuticals be delivered by quantum dots? Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery, 1–3. [CrossRef]

- Matea, C., Mocan, T., Tabaran, F., Pop, T., Moșteanu, O., Puia, C., Iancu, C., & Mocan, L. (2017). Quantum dots in imaging, drug delivery and sensor applications. International Journal of Nanomedicine, Volume 12, 5421–5431. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., & Huang, G. (2024). The utilization of quantum dot labeling as a burgeoning technique in the field of biological imaging. RSC Advances, 14(29), 20884–20897. [CrossRef]

- Deerinck, T. J. (2008). The application of fluorescent quantum dots to confocal, multiphoton, and electron microscopic imaging. Toxicologic Pathology, 36(1), 112–116. [CrossRef]

- Delille, F., Pu, Y., Lequeux, N., & Pons, T. (2022). Designing the surface chemistry of inorganic nanocrystals for cancer imaging and therapy. Cancers, 14(10), 2456. [CrossRef]

- Park, Y., Jeong, S., & Kim, S. (2017). Medically translatable quantum dots for biosensing and imaging. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology C Photochemistry Reviews, 30, 51–70. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Zhao, L., Wang, Z., Liu, S., & Pang, D. (2021). Near-Infrared-II quantum dots for in vivo imaging and cancer therapy. Small, 18(8). [CrossRef]

- Chinnathambi, S., & Shirahata, N. (2019). Recent advances on fluorescent biomarkers of near-infrared quantum dots forin vitroandin vivoimaging. Science and Technology of Advanced Materials, 20(1), 337–355. [CrossRef]

- Gil, H. M., Price, T. W., Chelani, K., Bouillard, J. G., Calaminus, S. D., & Stasiuk, G. J. (2021). NIR-quantum dots in biomedical imaging and their future. iScience, 24(3), 102189. [CrossRef]

- Martinić, I., Eliseeva, S. V., & Petoud, S. (2016). Near-infrared emitting probes for biological imaging: Organic fluorophores, quantum dots, fluorescent proteins, lanthanide(III) complexes and nanomaterials. Journal of Luminescence, 189, 19–43. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M., Yue, J., Cui, R., Ma, Z., Wan, H., Wang, F., Zhu, S., Zhou, Y., Kuang, Y., Zhong, Y., Pang, D., & Dai, H. (2018). Bright quantum dots emitting at ∼1,600 nm in the NIR-IIb window for deep tissue fluorescence imaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(26), 6590–6595. [CrossRef]

- Furey, B. J., Stacy, B. J., Shah, T., Barba-Barba, R. M., Carriles, R., Bernal, A., Mendoza, B. S., Korgel, B. A., & Downer, M. C. (2022). Two-Photon excitation spectroscopy of silicon quantum dots and ramifications for Bio-Imaging. ACS Nano, 16(4), 6023–6033. [CrossRef]

- Nadtochiy, A., Suwal, O. K., Kim, D., & Korotchenkov, O. (2022, October 5). Photocurrent and photoacoustic detection of plasmonic behavior of CdSe quantum dots grown in Au nanogaps. arXiv: 2210.02542. [CrossRef]

- Guo, T., Tang, Q., Guo, Y., Qiu, H., Dai, J., Xing, C., Zhuang, S., & Huang, G. (2020). Boron Quantum Dots for photoacoustic Imaging-Guided photothermal therapy. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 13(1), 306–311. [CrossRef]

- Bodian, S., Colchester, R. J., Macdonald, T. J., Ambroz, F., De Gutierrez, M. B., Mathews, S. J., Fong, Y. M. M., Maneas, E., Welsby, K. A., Gordon, R. J., Collier, P., Zhang, E. Z., Beard, P. C., Parkin, I. P., Desjardins, A. E., & Noimark, S. (2021). CUINS 2 Quantum Dot and polydimethylsiloxane nanocomposites for All-Optical ultrasound and Photoacoustic Imaging. Advanced Materials Interfaces, 8(20). [CrossRef]

- Lamb, J., & Holland, J. P. (2017). Advanced methods for radiolabeling multimodality nanomedicines for SPECT/MRI and PET/MRI. Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 59(3), 382–389. [CrossRef]

- Ni, D., Ehlerding, E. B., & Cai, W. (2018). Multimodality Imaging Agents with PET as the Fundamental Pillar. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 58(9), 2570–2579. [CrossRef]

- Seibold, U., Wängler, B., Schirrmacher, R., & Wängler, C. (2014). Bimodal Imaging probes for combined PET and OI: recent developments and future directions for hybrid agent development. BioMed Research International, 2014, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S., Yukawa, H., Yamada, K., Murata, Y., Jo, J., Yamamoto, M., Sugawara-Narutaki, A., Tabata, Y., & Baba, Y. (2022). In vivo multimodal imaging of stem cells using nanohybrid particles incorporating quantum dots and magnetic nanoparticles. Sensors, 22(15), 5705. [CrossRef]

- Tang, T., Garcia, J., & Louie, A. Y. (2016). PET/SPECT/MRI multimodal nanoparticles. In Springer eBooks (pp. 205–228). [CrossRef]

- Rajamanickam, K. (2019). Multimodal molecular imaging strategies using functionalized nano probes. Journal of Nanotechnology Research, 1(4), 119-135.

- Allara, L., Bertolotti, F., & Guagliardi, A. (2024). A deep learning approach for quantum dots sizing from wide-angle X-ray scattering data. Npj Computational Materials, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Cheng, J. Y. X., Chua, J. J., & Olivo, M. (2022). Characterization of Quantum Dots with Hyperspectral Fluorescence Microscopy for Multiplexed Optical Imaging of Biomolecules. bioRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory). [CrossRef]

- Le, N., & Kim, K. (2023). Current advances in the biomedical applications of quantum dots: promises and challenges. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(16), 12682. [CrossRef]

- Udoisoh, M. G., & Onyemere, R. O. (2024). Machine Learning-Driven Optimization of Quantum Dot Superlattices for Enhanced Photonic Properties. European Journal of Applied Science, Engineering and Technology, 2(5), 130-141. [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S. M., Hashemi, S. A., Kalashgrani, M. Y., Omidifar, N., Lai, C. W., Rao, N. V., Gholami, A., & Chiang, W. (2022). The Pivotal Role of Quantum Dots-Based Biomarkers Integrated with Ultra-Sensitive Probes for Multiplex Detection of Human Viral Infections. Pharmaceuticals, 15(7), 880. [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Perez, P., Tsoutsi, D., Xu, R., & Rivera_Gil, P. (2018). Hyperspectral-Enhanced dark field microscopy for single and collective nanoparticle characterization in biological environments. Materials, 11(2), 243. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Chua, J. J., Tang, W. Y. H., Cheng, J. Y. X., Li, X., & Olivo, M. (2023). An ultrathin fiber-based fluorescent imaging probe based on hyperspectral imaging. Frontiers in Physics, 10. [CrossRef]

- Lai, C., Karmakar, R., Mukundan, A., Natarajan, R. K., Lu, S., Wang, C., & Wang, H. (2024). Advancing hyperspectral imaging and machine learning tools toward clinical adoption in tissue diagnostics: A comprehensive review. APL Bioengineering, 8(4). [CrossRef]

- Khonina, S. N., Kazanskiy, N. L., Oseledets, I. V., Nikonorov, A. V., & Butt, M. A. (2024). Synergy between Artificial Intelligence and Hyperspectral Imagining—A Review. Technologies, 12(9), 163. [CrossRef]

- Yamada, S., Yukawa, H., Yamada, K., Murata, Y., Jo, J., Yamamoto, M., Sugawara-Narutaki, A., Tabata, Y., & Baba, Y. (2022). In vivo multimodal imaging of stem cells using nanohybrid particles incorporating quantum dots and magnetic nanoparticles. Sensors, 22(15), 5705. [CrossRef]

- Hembury, M., Chiappini, C., Bertazzo, S., Kalber, T. L., Drisko, G. L., Ogunlade, O., Walker-Samuel, S., Krishna, K. S., Jumeaux, C., Beard, P. C., Kumar, C. S. S. R., Porter, A. E., Lythgoe, M. F., Boissière, C., Sánchez, C., & Stevens, M. M. (2015). Gold–silica quantum rattles for multimodal imaging and therapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(7), 1959–1964. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y., Xu, Z., Hu, Y., Hu, L., Zi, Y., Wang, M., Feng, X., & Huang, W. (2022). Bismuth Quantum Dot (Bi QD)/Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Nanocomposites with Self-Cleaning and Antibacterial Activity for Dental Applications. Nanomaterials, 12(21), 3911. [CrossRef]

- Devi, S., Kumar, M., Tiwari, A., Tiwari, V., Kaushik, D., Verma, R., Bhatt, S., Sahoo, B. M., Bhattacharya, T., Alshehri, S., Ghoneim, M. M., Babalghith, A. O., & Batiha, G. E. (2022). Quantum Dots: an emerging approach for cancer therapy. Frontiers in Materials, 8. [CrossRef]

- Alves, L. P., Pilla, V., Murgo, D. O. A., & Munin, E. (2010). Core–shell quantum dots tailor the fluorescence of dental resin composites. Journal of Dentistry, 38(2), 149–152. [CrossRef]

- Xu, R., Lai, S., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, X. (2024). Research Progress of Heavy-Metal-Free Quantum Dot Light-Emitting diodes. Nanomaterials, 14(10), 832. [CrossRef]

- Vo, D., & Trinh, K. L. (2024). Advances in wearable biosensors for healthcare: current trends, applications, and future perspectives. Biosensors, 14(11), 560. [CrossRef]

- Guk, K., Han, G., Lim, J., Jeong, K., Kang, T., Lim, E., & Jung, J. (2019). Evolution of Wearable Devices with Real-Time Disease Monitoring for Personalized Healthcare. Nanomaterials, 9(6), 813. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., Badea, M., Tiwari, S., & Marty, J. L. (2021). Wearable Biosensors: an alternative and practical approach in healthcare and disease monitoring. Molecules, 26(3), 748. [CrossRef]

- Song, Z., Zhou, S., Qin, Y., Xia, X., Sun, Y., Han, G., Shu, T., Hu, L., & Zhang, Q. (2023). Flexible and wearable biosensors for monitoring health conditions. Biosensors, 13(6), 630. [CrossRef]

- Santos, C. C. D., Lucena, G. N., Pinto, G. C., Júnior, M. J., & Marques, R. F. (2020). Advances and current challenges in non-invasive wearable sensors and wearable biosensors—A mini-review. Medical Devices & Sensors, 4(1). [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Tang, H., Liu, Y., Qiao, Y., Xia, H., & Zhou, J. (2022). Oral wearable sensors: Health management based on the oral cavity. Biosensors and Bioelectronics X, 10, 100135. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. A., Li, R., & Tse, Z. T. H. (2023). Reshaping healthcare with wearable biosensors. Scientific Reports, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Archer, N., Ladan, S., Lancashire, H. T., & Petridis, H. (2024). Use of Biosensors within the Oral Environment for Systemic Health Monitoring—A Systematic Review. Oral, 4(2), 148–162. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Zhang, X., & Bi, S. (2022). Two-Dimensional Quantum Dot-Based electrochemical biosensors. Biosensors, 12(4), 254. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M., Mahajan, P., Alsubaie, A. S., Khanna, V., Chahal, S., Thakur, A., Yadav, A., Arya, A., Singh, A., & Singh, G. (2024). Next-Generation nanomaterials-based biosensors: Real-Time biosensing devices for detecting emerging environmental pollutants. Materials Today Sustainability, 101068. [CrossRef]

- Rajan, A., Vishnu, J., & Shankar, B. (2024). Tear-Based Ocular Wearable biosensors for human health monitoring. Biosensors, 14(10), 483. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Ahmad Ahmad Odah (2024). Unveiling the potential of quantum dots in revolutionizing stem cell tracking for regenerative medicine. African Research Journal of Medical Sciences. 1(2), 62-74. [CrossRef]

- Yan, X., An, N., Zhang, Z., Qiu, Q., Yang, D., Wei, P., … Guo, J. (2024). Graphene Oxide Quantum Dots-Preactivated Dental Pulp Stem Cells/GelMA Facilitates Mitophagy-Regulated Bone Regeneration. International Journal of Nanomedicine, 19, 10107–10128. [CrossRef]

- Jahed, V., Vasheghani-Farahani, E., Bagheri, F., Zarrabi, A., Jensen, H. H., & Larsen, K. L. (2020). Quantum dots-βcyclodextrin-histidine labeled human adipose stem cells-laden chitosan hydrogel for bone tissue engineering. Nanomedicine Nanotechnology Biology and Medicine, 27, 102217. [CrossRef]

- Majood, M., Garg, P., Chaurasia, R., Agarwal, A., Mohanty, S., & Mukherjee, M. (2022). Carbon quantum dots for stem cell imaging and deciding the fate of stem cell differentiation. ACS Omega, 7(33), 28685–28693. [CrossRef]

- Fasbender, S., Zimmermann, L., Cadeddu, R., Luysberg, M., Moll, B., Janiak, C., Heinzel, T., & Haas, R. (2019). The Low Toxicity of Graphene Quantum Dots is Reflected by Marginal Gene Expression Changes of Primary Human Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Scientific Reports, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Puleio, F., Tosco, V., Pirri, R., Simeone, M., Monterubbianesi, R., Lo Giudice, G., & Lo Giudice, R. (2024). Augmented Reality in Dentistry: Enhancing Precision in Clinical Procedures—A Systematic Review. Clinics and Practice, 14(6), 2267–2283. [CrossRef]

- Bonny, T., Nassan, W. A., Obaideen, K., Mallahi, M. N. A., Mohammad, Y., & El-Damanhoury, H. M. (2023). Contemporary role and applications of artificial intelligence in dentistry. F1000Research, 12, 1179. [CrossRef]

- Macrì, M., D’Albis, G., D’Albis, V., Timeo, S., & Festa, F. (2023). Augmented Reality-Assisted surgical exposure of an impacted tooth: a pilot study. Applied Sciences, 13(19), 11097. [CrossRef]

- Akulauskas, M., Butkus, K., Rutkūnas, V., Blažauskas, T., & Jegelevičius, D. (2023). Implementation of augmented reality in dental Surgery using HoloLens 2: An in vitro study and accuracy assessment. Applied Sciences, 13(14), 8315. [CrossRef]

- Monterubbianesi, R., Tosco, V., Vitiello, F., Orilisi, G., Fraccastoro, F., Putignano, A., & Orsini, G. (2022). Augmented, Virtual and Mixed Reality in Dentistry: A narrative review on the existing platforms and future challenges. Applied Sciences, 12(2), 877. [CrossRef]

- Zebibula, A., Alifu, N., Xia, L., Sun, C., Yu, X., Xue, D., Liu, L., Li, G., & Qian, J. (2017). Ultrastable and biocompatible NIR-II quantum dots for functional bioimaging. Advanced Functional Materials, 28(9). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., Yoo, P., Feng, Y., Sankar, A., Sadr, A., & Seibel, E. J. (2019). Towards AR-assisted visualisation and guidance for imaging of dental decay. Healthcare Technology Letters, 6(6), 243–248. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, E. D., Hafeji, S., Khurshid, Z., Imran, E., Zafar, M. S., Saeinasab, M., & Sefat, F. (2022). Biophotonics in dentistry. Applied Sciences, 12(9), 4254. [CrossRef]

- Song, T., Yang, C., Dianat, O., & Azimi, E. (2018). Endodontic guided treatment using augmented reality on a head-mounted display system. Healthcare Technology Letters, 5(5), 201–207. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y., & Lee, C. H. (2017). Augmented reality for personalized nanomedicines. Biotechnology Advances, 36(1), 335–343. [CrossRef]

- Mela, C. A. (2018). MULTIMODAL IMAGING, COMPUTER VISION, AND AUGMENTED REALITY FOR MEDICAL GUIDANCE (Doctoral dissertation, University of Akron).

- Kalyani, N. T., Dhoble, S. J., Domanska, M. M., Vengadaesvaran, B., Nagabhushana, H., & Arof, A. K. (Eds.). (2023). Quantum dots: emerging materials for versatile applications. Woodhead Publishing. eBook ISBN: 9780323852791.

- Park, J. H., Jin, S., Lee, E., & Ahn, H. S. (2021). Electrochemical synthesis of core–shell nanoparticles by seed-mediated selective deposition. Chemical Science, 12(40), 13557–13563. [CrossRef]

- Lau, E. C. H. T., Åhlén, M., Cheung, O., Ganin, A. Y., Smith, D. G. E., & Yiu, H. H. P. (2023). Gold-iron oxide (Au/Fe3O4) magnetic nanoparticles as the nanoplatform for binding of bioactive molecules through self-assembly. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 10. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M. D., Tran, H., Xu, S., & Lee, T. R. (2021). FE3O4 nanoparticles: structures, synthesis, magnetic properties, surface functionalization, and emerging applications. Applied Sciences, 11(23), 11301. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Wang, H., Xu, S., Li, H., Lu, Y., & Zhu, C. (2023). Recyclable Multifunctional magnetic FE3O4@SIO2@AU Core/Shell nanoparticles for SERS Detection of HG (II). Chemosensors, 11(6), 347. [CrossRef]

- De Jesús Ruíz-Baltazar, Á. (2021). Sonochemical activation-assisted biosynthesis of Au/Fe3O4 nanoparticles and sonocatalytic degradation of methyl orange. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 73, 105521. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q., Zhou, J., & Wong, C. J. (2021). A balanced strategy for the FFBS operator integrating dispatch area, route, and depot based on multimodel technologies. Journal of Advanced Transportation, 2021, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- De Jesús Ruíz-Baltazar, Á., Böhnel, H. N., Ordaz, D. L., Cervantes-Chávez, J. A., Méndez-Lozano, N., & Reyes-López, S. Y. (2023). Green Ultrasound-Assisted Synthesis of Surface-Decorated Nanoparticles of Fe3O4 with Au and Ag: Study of the Antifungal and Antibacterial Activity. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 14(6), 304. [CrossRef]

- Bonilla, C. A. M., & Kouznetsov, V. V. (2016). “Green” Quantum Dots: Basics, Green Synthesis, and Nanotechnological Applications. Green Nanotechnology-Overview and Further Prospects, 1, 174-192. [CrossRef]

- Kulah, Jonathan & Aykac, Ahmet. (2022). Synthesis and Characterization of Silver Quantum Dots from Moringa Oleifera Leaves & Seeds Extracts. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Badilla, A., Calderon-Ayala, G., Delgado-Beleño, Y., Heras-Sánchez, M. C., Hurtado, R. B., Leal-Pérez, J. E.,… & Cortez-Valadez, M. (2023). Green Synthesis for Carbon Quantum Dots via Opuntia ficus-indica and Agave maximiliana: Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Sensing Applications. ACS omega, 8(37), 33342-33348. [CrossRef]

- Ngoc, L. T. N., Moon, J. Y., & Lee, Y. C. (2023). Plant Extract-Derived Carbon Dots as Cosmetic Ingredients. Nanomaterials, 13(19), 2654. [CrossRef]

- Kadyan, P., Thillai Arasu, P., & Kataria, S. K. (2024). Graphene Quantum dots: Green Synthesis, characterization, and antioxidant and antimicrobial potential. International Journal of Biomaterials, 2024(1), 2626006. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., Das, K., Chatterjee, S., Sahoo, P., Kundu, S., Pal, M.,… & Ghosh, C. K. (2023). Facile and green synthesis of novel fluorescent carbon quantum dots and their silver heterostructure: An in vitro anticancer activity and imaging on colorectal carcinoma. ACS omega, 8(5), 4566-4577. [CrossRef]

- Praseetha, P. K., Litany, R. J., Alharbi, H. M., Khojah, A. A., Akash, S., Bourhia, M.,… & Shazly, G. A. (2024). Green synthesis of highly fluorescent carbon quantum dots from almond resin for advanced theranostics in biomedical applications. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 24435. [CrossRef]

- Anooj, E. S., & Praseetha, P. K. (2020). GREEN SYNTHESIS AND CHARACTERIZATION OF GRAPHENE QUANTUM DOTS FROM ROSA GALLICA PETALEXTRACT. Plant Archives, 20(2), 6151-6155.

- Fang, X. W., Chang, H., Wu, T., Yeh, C. H., Hsiao, F. L., Ko, T. S.,… & Lin, Y. W. (2024). Green Synthesis of Carbon Quantum Dots and Carbon Quantum Dot-Gold Nanoparticles for Applications in Bacterial Imaging and Catalytic Reduction of Aromatic Nitro Compounds. ACS omega, 9(22), 23573-23583. [CrossRef]

- Pete, A. M., Ingle, P. U., Raut, R. W., Shende, S. S., Rai, M., Minkina, T. M.,… & Gade, A. K. (2023). Biogenic synthesis of fluorescent carbon dots (CDs) and their application in bioimaging of agricultural crops. Nanomaterials, 13(1), 209. [CrossRef]

- Kurochkina, M., Konshina, E., Oseev, A., & Hirsch, S. (2018). Hybrid structures based on gold nanoparticles and semiconductor quantum dots for biosensor applications. Nanotechnology, science and applications, 15-21. [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S., Duadi, H., Fleger, Y., & Fixler, D. (2022). Design and use of a gold nanoparticle–carbon dot hybrid for a FLIM-based implication nano logic gate. ACS omega, 7(26), 22818-22824. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M., Urvoas, A., Even-Hernandez, P., Burel, A., Mériadec, C., Artzner, F.,… & Marchi, V. (2020). Hybrid gold nanoparticle–quantum dot self-assembled nanostructures driven by complementary artificial proteins. Nanoscale, 12(7), 4612-4621. [CrossRef]

- Abolghasemi-Fakhri, Z., & Amjadi, M. (2021). Gold nanostar@ graphene quantum dot as a new colorimetric sensing platform for detection of cysteine. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 261, 120010. [CrossRef]

- Karadurmus, L., Ozcelikay, G., Vural, S., & Ozkan, S. A. (2021). An overview on quantum dot-based nanocomposites for electrochemical sensing on pharmaceutical assay. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research: IJPR, 20(3), 187. [CrossRef]

- Miao, X., Wen, S., Su, Y., Fu, J., Luo, X., Wu, P.,… & Zhu, J. J. (2019). Graphene quantum dots wrapped gold nanoparticles with integrated enhancement mechanisms as sensitive and homogeneous substrates for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Analytical chemistry, 91(11), 7295-7303. [CrossRef]

- Kurochkina, M., Konshina, E., Oseev, A., & Hirsch, S. (2018). Hybrid structures based on gold nanoparticles and semiconductor quantum dots for biosensor applications. Nanotechnology, science and applications, 15-21. [CrossRef]

- Abrishami, A., Bahrami, A. R., Nekooei, S., Sh. Saljooghi, A., & Matin, M. M. (2024). Hybridized quantum dot, silica, and gold nanoparticles for targeted chemo-radiotherapy in colorectal cancer theranostics. Communications Biology, 7(1), 393. [CrossRef]

- Raj, D., Kumar, A., Kumar, D., Kant, K., & Mathur, A. (2024). Gold–Graphene Quantum Dot Hybrid Nanoparticle for Smart Diagnostics of Prostate Cancer. Biosensors, 14(11), 534. [CrossRef]

- Gong, L., Feng, L., Zheng, Y., Luo, Y., Zhu, D., Chao, J.,… & Wang, L. (2022). Molybdenum disulfide-based nanoprobes: Preparation and sensing application. Biosensors, 12(2), 87. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y., & Li, J. (2020). MoS2 quantum dots: synthesis, properties and biological applications. Materials Science and Engineering: C, 109, 110511. [CrossRef]

- Kabel, J., Sharma, S., Acharya, A., Zhang, D., & Yap, Y. K. (2021). Molybdenum disulfide quantum dots: properties, synthesis, and applications. C, 7(2), 45. [CrossRef]

- Namita, Khan, A., Arti, Alam, N., Sadasivuni, K. K., & Ansari, J. R. (2024). MoS2 quantum dots and their diverse sensing applications. Emergent Materials, 1-31. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P. K., Ulla, H., Satyanarayan, M. N., Rawat, K., Gaur, A., Gawali, S.,… & Bohidar, H. B. (2020). Fluorescent MoS2 quantum dot–DNA nanocomposite hydrogels for organic light-emitting diodes. ACS Applied Nano Materials, 3(2), 1289-1297. [CrossRef]

- Ali, L., Subhan, F., Ayaz, M., Hassan, S. S. U., Byeon, C. C., Kim, J. S., & Bungau, S. (2022). Exfoliation of MoS2 quantum dots: recent progress and challenges. Nanomaterials, 12(19), 3465. [CrossRef]

- Fei, X., Liu, Z., Hou, Y., Li, Y., Yang, G., Su, C.,… & Guo, Z. (2017). Synthesis of Au NP@ MoS2 quantum dots core@ shell nanocomposites for SERS bio-analysis and label-free bio-imaging. Materials, 10(6), 650. [CrossRef]

- Kabel, J., Sharma, S., Acharya, A., Zhang, D., & Yap, Y. K. (2021). Molybdenum disulfide quantum dots: properties, synthesis, and applications. C, 7(2), 45. [CrossRef]

- Ragib, A. A., Amin, A. A., Alanazi, Y. M., Kormoker, T., Uddin, M., Siddique, M. a. B., & Barai, H. R. (2023). Multifunctional carbon dots in nanomaterial surface modification: a descriptive review. Carbon Research, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Mandal, M., Banik, D., Karak, A., Manna, S. K., & Mahapatra, A. K. (2022). Spiropyran–Merocyanine based Photochromic fluorescent probes: Design, synthesis, and applications. ACS Omega, 7(42), 36988–37007. [CrossRef]

- Ragib, A. A., Amin, A. A., Alanazi, Y. M., Kormoker, T., Uddin, M., Siddique, M. a. B., & Barai, H. R. (2023). Multifunctional carbon dots in nanomaterial surface modification: a descriptive review. Carbon Research, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., et al. (2020). Synthesis of highly luminescent carbon quantum dots using organosilane as a coordinating solvent. Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 8(12), 4105-4112. [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, J., Attar, R. E., Thuau, D., Estrany, F., Abbas, M., & Torras, J. (2024). Carbon quantum dots composite for enhanced selective detection of dopamine with organic electrochemical transistors. Microchimica Acta, 191(10). [CrossRef]

- Hamidu, A., Pitt, W. G., & Husseini, G. A. (2023). Recent breakthroughs in using quantum dots for cancer imaging and drug delivery purposes. Nanomaterials, 13(18), 2566. [CrossRef]

- Fatima, I., Rahdar, A., Sargazi, S., Barani, M., Hassanisaadi, M., & Thakur, V. K. (2021). Quantum dots: synthesis, antibody conjugation, and HER2-Receptor targeting for breast cancer therapy. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 12(4), 75. [CrossRef]

- Mohkam, M., Sadraeian, M., Lauto, A., Gholami, A., Nabavizadeh, S. H., Esmaeilzadeh, H., & Alyasin, S. (2023). Exploring the potential and safety of quantum dots in allergy diagnostics. Microsystems & Nanoengineering, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Tam, K. C., et al. (2021). Facile synthesis of cysteine-functionalized graphene quantum dots for a fluorescence probe for mercury ions. RSC Advances, 11(12), 6789-6796. [CrossRef]

- Karami, M. H., & Abdouss, M. (2024). Recent advances of carbon quantum dots in tumor imaging. Nanomedicine Journal, 11(1). [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente, M., & López, J. A. (2023). Photodynamic therapy in cancer treatment: Mechanisms, applications, and perspectives. Frontiers in Oncology, 13, 1081774. [CrossRef]

- Smith, L., Harbison, K. E., Diroll, B. T., & Fedin, I. (2023). Acceleration of Near-IR Emission through Efficient Surface Passivation in Cd3P2 Quantum Dots. Materials, 16(19), 6346. [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, N., Monchen, J. O., Crisp, R. W., Grimaldi, G., Bergstein, H. A., Du Fossé, I.,… & Houtepen, A. J. (2018). Finding and fixing traps in II–VI and III–V colloidal quantum dots: the importance of Z-type ligand passivation. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 140(46), 15712-15723. [CrossRef]

- Azam, N., Najabat Ali, M., & Javaid Khan, T. (2021). Carbon quantum dots for biomedical applications: review and analysis. Frontiers in Materials, 8, 700403. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., Kumar, D., Saikia, M., & Subramania, A. (2023). A review on plant derived carbon quantum dots for bio-imaging. Materials Advances, 4(18), 3951-3966. [CrossRef]

- Yan, S., Tang, S., Luo, M., Xue, L., Liu, S., Elemike, E. E.,… & Li, Q. (2021). Surface passivation by congeneric quantum dots for high-performance and stable CsPbBr 3-based photodetectors. Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 9(31), 10089-10100. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., & Dong, T. (2018). Photoluminescence tuning in carbon dots: surface passivation or/and functionalization, heteroatom doping. Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 6(30), 7944-7970. [CrossRef]

- Pechnikova, N. A., Domvri, K., Porpodis, K., Istomina, M. S., Iaremenko, A. V., & Yaremenko, A. V. (2024). Carbon Quantum Dots in Biomedical Applications: Advances, Challenges, and Future Prospects. Aggregate, e707. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., Che, F., Jo, J. W., Choi, J., García de Arquer, F. P., Voznyy, O.,… & Sargent, E. H. (2019). A Facet-Specific Quantum Dot Passivation Strategy for Colloid Management and Efficient Infrared Photovoltaics. Advanced Materials, 31(17), 1805580. [CrossRef]

- Joo, S. Y., Park, H. S., Kim, D. Y., Kim, B. S., Lee, C. G., & Kim, W. B. (2018). An investigation into the effective surface passivation of quantum dots by a photo-assisted chemical method. AIP Advances, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Trapiella-Alfonso, L., Pons, T., Lequeux, N., Leleu, L., Grimaldi, J., Tasso, M.,… & Varenne, A. (2018). Clickable-zwitterionic copolymer capped-quantum dots for in vivo fluorescence tumor imaging. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 10(20), 17107-17116. [CrossRef]

- Debayle, M., Balloul, E., Dembele, F., Xu, X., Hanafi, M., Ribot, F.,… & Lequeux, N. (2019). Zwitterionic polymer ligands: an ideal surface coating to totally suppress protein-nanoparticle corona formation?. Biomaterials, 219, 119357. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., Delille, F., Bartier, S., Pons, T., Lequeux, N., Louis, B.,… & Gacoin, T. (2022). Zwitterionic Polymers toward the Development of Orientation-Sensitive Bioprobes. Langmuir, 38(34), 10512-10519. [CrossRef]

- Han, Z., Sarkar, S., & Smith, A. M. (2020). Zwitterion and oligo (ethylene glycol) synergy minimizes nonspecific binding of compact quantum dots. ACS nano, 14(3), 3227-3241. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L., Jiang, H., Dong, J., Zhang, W., Dang, G., Yang, M.,… & Dong, L. (2020). PEGylated MoS2 quantum dots for traceable and pH-responsive chemotherapeutic drug delivery. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces, 185, 110590. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. F., Kundu, D., Gogoi, M., Shrestha, A. K., Karanth, N. G., & Patra, S. (2020). Enzyme-responsive and enzyme immobilized nanoplatforms for therapeutic delivery: An overview of research innovations and biomedical applications. Nanopharmaceuticals: Principles and Applications Vol. 3, 165-200. [CrossRef]

- Franke, M., Leubner, S., Dubavik, A., George, A., Savchenko, T., Pini, C.,… & Richter, A. (2017). Immobilization of pH-sensitive CdTe quantum dots in a poly (acrylate) hydrogel for microfluidic applications. Nanoscale research letters, 12, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J., Zhang, R., Li, J., Sang, Y., Tang, W., Rivera Gil, P., & Liu, H. (2015). Fluorescent graphene quantum dots as traceable, pH-sensitive drug delivery systems. International journal of nanomedicine, 6709-6724. [CrossRef]

- Cai, X., Luo, Y., Zhang, W., Du, D., & Lin, Y. (2016). pH-Sensitive ZnO quantum dots–doxorubicin nanoparticles for lung cancer targeted drug delivery. ACS applied materials & interfaces, 8(34), 22442-22450. [CrossRef]

- Bao, W., Ma, H., Wang, N., & He, Z. (2019). pH-sensitive carbon quantum dots− doxorubicin nanoparticles for tumor cellular targeted drug delivery. Polymers for Advanced Technologies, 30(11), 2664-2673. [CrossRef]

- Meher, M. K., & Poluri, K. M. (2020). pH-sensitive nanomaterials for smart release of drugs. In Intelligent Nanomaterials for Drug Delivery Applications (pp. 17-41). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., He, L., Yu, B., Chen, Y., Shen, Y., & Cong, H. (2018). ZnO quantum dots modified by pH-activated charge-reversal polymer for tumor targeted drug delivery. Polymers, 10(11), 1272. [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z., Zhou, S., Garcia, C., Fan, L., & Zhou, J. (2017). pH-Responsive fluorescent graphene quantum dots for fluorescence-guided cancer surgery and diagnosis. Nanoscale, 9(15), 4928-4933. [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, E. S., Ghanbari, N., Salehi, Z., Derakhti, S., Amoabediny, G., Akbari, M., & Tokmedash, M. A. (2023). Smart pH-responsive magnetic graphene quantum dots nanocarriers for anticancer drug delivery of curcumin. Materials Chemistry and Physics, 297, 127336. [CrossRef]

- Matea, C., Mocan, T., Tabaran, F., Pop, T., Moșteanu, O., Puia, C., Iancu, C., & Mocan, L. (2017). Quantum dots in imaging, drug delivery and sensor applications. International Journal of Nanomedicine, Volume 12, 5421–5431. [CrossRef]

- Ezike, T. C., Okpala, U. S., Onoja, U. L., Nwike, P. C., Ezeako, E. C., Okpara, J. O., Okoroafor, C. C., Eze, S. C., Kalu, O. L., Odoh, E. C., Nwadike, U., Ogbodo, J. O., Umeh, B. U., Ossai, E. C., & Nwanguma, B. C. (2023). Advances in drug delivery systems, challenges and future directions. Heliyon, 9(6), e17488. [CrossRef]

- Gour, A., Ramteke, S., & Jain, N. K. (2021). Pharmaceutical applications of quantum dots. AAPS PharmSciTech, 22(7). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C., Song, X., Liu, Y. et al. Synthesis of graphene quantum dots and their applications in drug delivery. J Nanobiotechnol 18, 142 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Dirheimer, L., Pons, T., Marchal, F., & Bezdetnaya, L. (2022). Quantum Dots Mediated Imaging and Phototherapy in cancer spheroid Models: State of the art and perspectives. Pharmaceutics, 14(10), 2136. [CrossRef]

- Nir, Shlomo, and Shimon Shaltiel. "Nanomaterials for Phototherapy: Current Status and Future Directions." Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology, and Medicine 29 (2020): 102254. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Wei, et al. "Fluorophores for Biological Imaging." Nature Reviews Chemistry 5, no. 10 (2021): 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R., and M. A. R. M. O. A. "Fluorophores: A New Avenue for Biological Imaging." Chemical Society Reviews 49, no. 5 (2020): 1630-1654. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Zhang, X. (2022). The integration of fluorescence imaging in clinical settings: Challenges and opportunities. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, 19(3), 169-185. [CrossRef]

- Vahrmeijer AL, Hutteman M, van der Vorst JR, van de Velde CJH, Frangioni JV. Image-guided cancer surgery using nearinfrared fluorescence. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013;10:50713. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., & Wang, K. (2021). Advances in fluorescence imaging for cancer detection and treatment. Frontiers in Oncology, 11, 618345. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Ying, et al. "Recent Advances in Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer Treatment." Journal of Controlled Release 304 (2019): 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, S., & Mroz, P. (2021). Photodynamic therapy: Mechanisms and applications in clinical practice. Cancers, 13(16), 3946. [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, S., et al. "Mechanisms of Photodynamic Therapy: A Review of the Current Understanding of the Role of Reactive Oxygen Species." Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 27 (2019): 262-270. [CrossRef]

- Zohuri, Bahman. (2024). Photodynamic Therapy (PDT): Mechanisms, Applications, Benefits, and Limitations. Medical & Clinical Research. 9. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Kessel, D., & Oleinick, N. L. (2021). Photodynamic therapy: A review of the mechanisms and clinical applications. Journal of Biomedical Optics, 26(5), 050901. [CrossRef]

- Gurney, M., & Kearney, S. (2022). Advances in photodynamic therapy: Mechanisms and clinical applications. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy, 38, 102746. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. E., & Chang, J. (2023). Recent studies in photodynamic therapy for cancer treatment: From basic research to clinical trials. Pharmaceutics, 15(9), 2257. [CrossRef]

- Azzolini, C., & Bianchi, M. (2021). Photodynamic therapy for age-related macular degeneration: A review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(3), 456. [CrossRef]

- Aebisher D, Serafin I, Batóg-Szczęch K, Dynarowicz K, Chodurek E, Kawczyk-Krupka A, Bartusik-Aebisher D. Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Cancer—The Selection of Synthetic Photosensitizers. Pharmaceuticals. 2024; 17(7):932. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Advances in Nanomaterial-Mediated Photothermal Cancer Therapies: Toward Clinical Applications. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 12, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Selective photothermolysis – precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation. Science 1983;220(4596):524_7. [CrossRef]

- Jin CS, Lovell JF, Chen J, Zheng G. Ablation of hypoxic tumors with dose-equivalent photothermal, but not photodynamic, therapy using a nanostructured porphyrin assembly. ACS Nano 2013;7(3):2541_50. [CrossRef]

- Xin Yang, Qi Zhao, JingWen Chen, Jiayue Liu, Jiacheng Lin, Jiaxuan Lu, Wenqing Li, Dongsheng Yu, Wei Zhao, "Graphene Oxide Quantum Dots Promote Osteogenic Differentiation of Stem Cells from Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth via the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway", Stem Cells International, vol. 2021, Article ID 8876745, 12 pages, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Hu, L.; Zi, Y.; Wang, M.; Feng, X.; Huang, W. Bismuth Quantum Dot (Bi QD)/Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) Nanocomposites with Self-Cleaning and Antibacterial Activity for Dental Applications. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3911. [CrossRef]

- Dirheimer, L.; Pons, T.; Marchal, F.; Bezdetnaya, L. Quantum Dots Mediated Imaging and Phototherapy in Cancer Spheroid Models: State of the Art and Perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2136. [CrossRef]

- Dirheimer, L.; Pons, T.; Marchal, F.; Bezdetnaya, L. Quantum Dots Mediated Imaging and Phototherapy in Cancer Spheroid Models: State of the Art and Perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2136. [CrossRef]

- Devi S, Kumar M, Tiwari A, Tiwari V, Kaushik D, Verma R, Bhatt S, Sahoo BM, Bhattacharya T, Alshehri S, Ghoneim MM, Babalghith AO and Batiha GE-S (2022) Quantum Dots: An Emerging Approach for Cancer Therapy. Front. Mater. 8:798440. [CrossRef]

- Armăşelu, A., & Jhalora, P. (2023). Application of quantum dots in biomedical and biotechnological fields. In Quantum Dots (pp. 245-276). Elsevier. . [CrossRef]

- Gidwani, B., Sahu, V., Shukla, S. S., Pandey, R., Joshi, V., Jain, V. K., & Vyas, A. (2021). Quantum dots: Prospectives, toxicity, advances and applications. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology, 61, 102308. . [CrossRef]

- Le, N., & Kim, K. (2023). Current Advances in the Biomedical Applications of Quantum Dots: Promises and Challenges. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 24(16), 12682. . [CrossRef]

- Li, G., Liu, Z., Gao, W., & Tang, B. (2023). Recent advancement in graphene quantum dots based fluorescent sensor: Design, construction and bio-medical applications. Coordination Chemistry Reviews, 478, 214966. . [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A. M., Knipe, J. M., Orive, G., & Peppas, N. A. (2019). Quantum dots in biomedical applications. Acta biomaterialia, 94, 44-63. . [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, A. A., Younis, M. A., Alsharidah, M., Al Rugaie, O., & Tawfeek, H. M. (2022). Biomedical applications of quantum dots: overview, challenges, and clinical potential. International journal of nanomedicine, 1951-1970. . [CrossRef]

| Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| I B-VI A | Cu2S |

| I B-VII A | AgBr |

| II B-VI A | ZnSe, ZnS, ZnO, CdS, CdSe, CdTe, HgS |

| III A-V A | AlSb, AlAs, AlP, GaSb, GaAs, InAs, InP |

| IV A-VI A | PbS, PbSe, PbTe |

| IV A | C, Si, Graphene |

| V A | Black Phosphorus |

| I B-III A-VI A | CuInS2, CuInSe2, AgInS |

| P dots | NIR800 |

| TMDCs | TiSe2, TaS2, MoSe2 |

| MXenea | Nb2C, Ti3C2 |

| Perovskiteb | CsPbI3 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).