Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

15 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Isolation of the Strain

2.2. Phenotypic and Morphological Characterization

2.3. Definitive Identification

2.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.5. Essential Oil and Antiseptic Susceptibility Testing

3. Results

3.1. Cultural Characterization

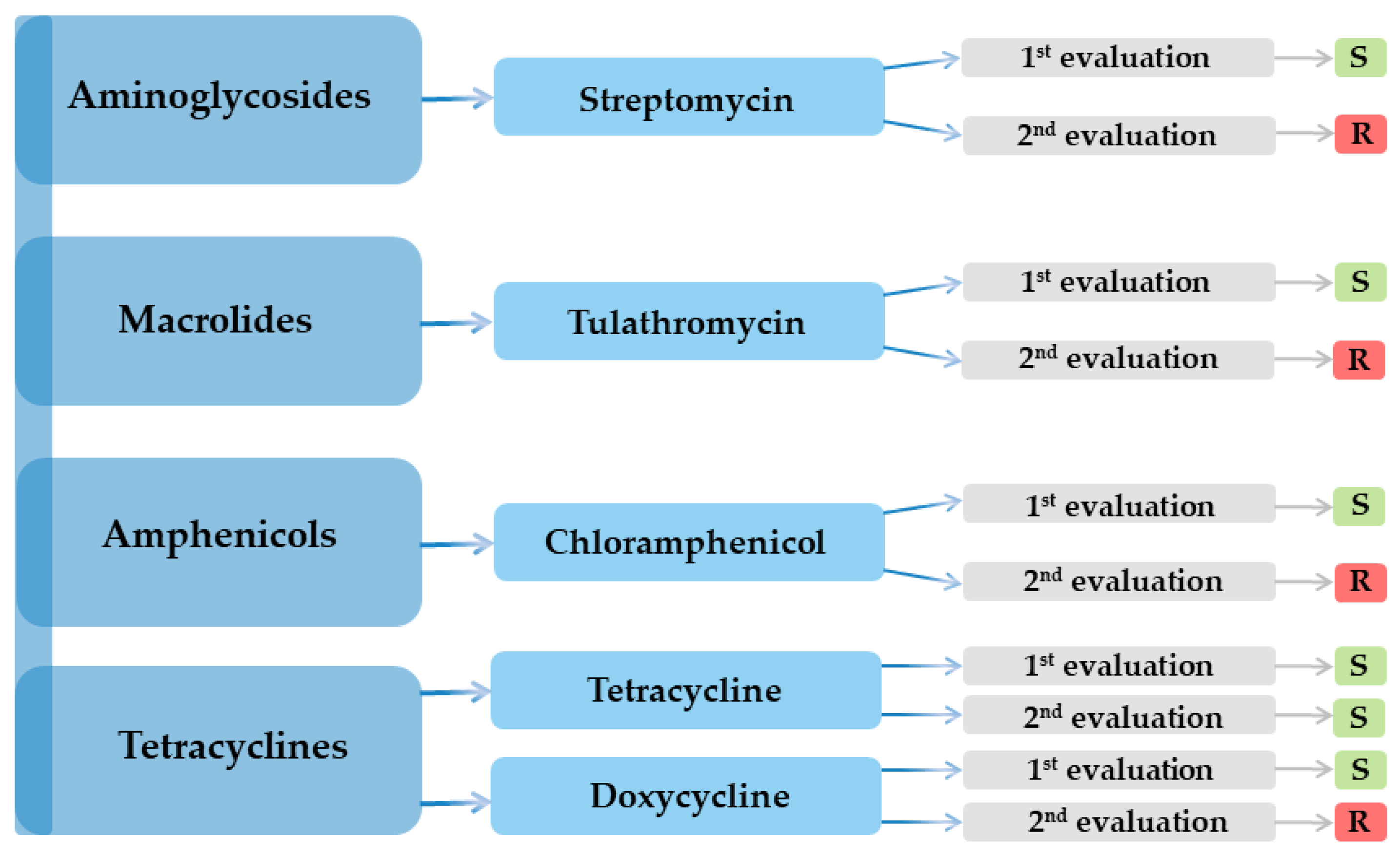

3.2. Antibiotic Susceptibility Testing

3.3. Essential oils susceptibility testing

4. Discussion

- Eugenol - a guaiacol derivative in clove, nutmeg, basil, and bay oils—acts as a bactericidal antiseptic. At 0.2 mg mL−1 it damages the cell membrane of carbapenem-resistant K. pneumoniae and blocks biofilm formation [54].

- Cinnamon bark oil (Cinnamomum verum) induces oxidative stress in KPC-producing K. pneumoniae, disrupts the phospholipid bilayer, and leads to loss of major outer-membrane proteins and cell viability [45].

- Thymol (from thyme) displays strong synergy with streptomycin or kanamycin, both inhibiting biofilm formation and destroying pre-formed K. pneumoniae biofilm [55].

- Purified EO from hibiscus rosa-sinensis inhibits biofilm formation; scanning electron microscopy shows marked morphological alteration [56].

- Ylang-ylang and vanilla/patchouli oils stabilized on iron-oxide nanostructures prevent K. pneumoniae adhesion and biofilm development [57].

- Tea tree and thyme EOs exhibit potent activity against MDR K. pneumoniae and cause severe loss of cellular integrity under electron microscopy [51].

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Holt, K.E.; Wertheim, H.; Zadoks, R.N.; Baker, S.; Whitehouse, C.A.; Dance, D.; Jenney, A.; Connor, T.R.; Hsu, L.Y.; Severin, J.; et al. Genomic analysis of diversity, population structure, virulence, and antimicrobial resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae, an urgent threat to public health. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015, 112, 27–E3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karampatakis, T.; Tsergouli, K.; Behzadi, P. Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: Virulence Factors, Molecular Epidemiology and Latest Updates in Treatment Options. Antibiotics. 2023, 12, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennart, M.; Guglielmini, J.; Bridel, S.; Maiden, M.C.; Jolley, K.A.; Criscuolo, A.; Brisse, S. A dual barcoding approach to bacterial strain nomenclature: genomic taxonomy of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2022, 39, 7–msac135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.C.; Tang, H.L.; Chiou, C.S.; Lin, Y.C.; Chiang, M.K.; Tung, K.C.; Lai, Y.C.; Lu, M.C. Prevalence and Virulence Profiles of Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolated From Different Animals. Veterinary Medicine and Science. 2025, 11, 2–e70243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Antimicrobial Resistance, Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae—Global Situation. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2024-DON527 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Blin, C.; Passet, V.; Touchon, M.; Rocha, E.P.; Brisse, S. Metabolic diversity of the emerging pathogenic lineages of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Environmental microbiology. 2017, 19, 5–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyres, K.L.; Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Froumine, R.; Tokolyi, A.; Gorrie, C.L.; Lam, M.M.; Duchêne, S.; Jenney, A.; Holt, K.E. Distinct evolutionary dynamics of horizontal gene transfer in drug resistant and virulent clones of Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLoS genetics. 2019, 15, 4–e1008114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, C.; Menezes, J.; Belas, A.; Aboim, C.; Cavaco-Silva, P.; Trigueiro, G.; Telo Gama, L.; Pomba, C. Klebsiella pneumoniae causing urinary tract infections in companion animals and humans: population structure, antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2019, 74, 3–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrosillo, N.; Taglietti, F.; Granata, G. Treatment options for colistin resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: present and future. Journal of clinical medicine. 2019, 8, 7–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, A.H.; Porto, W.F.; de Faria Jr, C.; Dias, S.C.; Alencar, S.A.; Pickard, D.J.; Hancock, R.E.; Franco, O.L. Genomic insights into the diversity, virulence and resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae extensively drug resistant clinical isolates. Microbial Genomics. 2021, 7, 8–000613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, N.; Yang, X.; Chan, E.W.; Zhang, R.; Chen, S. Klebsiella species: Taxonomy, hypervirulence and multidrug resistance. EBioMedicine. 2022, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyres, K.L.; Holt, K.E. Klebsiella pneumoniae population genomics and antimicrobial-resistant clones. Trends in microbiology. 2016, 24, 12–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, K.A.; Miller, V.L. The intersection of capsule gene expression, hypermucoviscosity and hypervirulence in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Current opinion in microbiology. 2020, 54, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Ferrer, S.; Peñaloza, H.F.; Budnick, J.A.; Bain, W.G.; Nordstrom, H.R.; Lee, J.S.; Van Tyne, D. Finding order in the chaos: outstanding questions in Klebsiella pneumoniae pathogenesis. Infection and immunity. 2021, 89, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kochan, T.J.; Nozick, S.H.; Medernach, R.L.; Cheung, B.H.; Gatesy, S.W.; Lebrun-Corbin, M.; Mitra, S.D.; Khalatyan, N.; Krapp, F.; Qi, C.; Ozer, E.A. Genomic surveillance for multidrug-resistant or hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae among United States bloodstream isolates. BMC infectious diseases. 2022, 22, 1–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.Y.; Ong, E.L. Positive string test in hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae liver abscess. Oxford Medical Case Reports. 2022, 4, omac035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wyres, K.L.; Lam, M.M.; Holt, K.E. Population genomics of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2020, 18, 6–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochońska, D.; Brzychczy-Włoch, M. Klebsiella Pneumoniae–Taxonomy, Occurrence, Identification, Virulence Factors and Pathogenicity. Advancements of Microbiology. 2024, 63, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, T.A.; Olson, R.; Fang, C.T.; Stoesser, N.; Miller, M.; MacDonald, U.; Hutson, A.; Barker, J.H.; La Hoz, R.M.; Johnson, J.R. Identification of biomarkers for differentiation of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae from classical K. pneumoniae. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2018, 56, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, T.A.; Marr, C.M. Hypervirulent klebsiella pneumoniae. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2019, 32, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, P.; Hu, D. The making of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 2022, 36, 12–e24743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, M.M.; Wyres, K.L.; Duchêne, S.; Wick, R.R.; Judd, L.M.; Gan, Y.H.; Hoh, C.H.; Archuleta, S.; Molton, J.S.; Kalimuddin, S.; Koh, T.H. Population genomics of hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae clonal-group 23 reveals early emergence and rapid global dissemination. Nature communications. 2018, 9, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, P.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yu, Y. A global perspective on the convergence of hypervirulence and carbapenem resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Journal of global antimicrobial resistance. 2021, 25, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, T.S.; Opstrup, K.V.; Christiansen, G.; Rasmussen, P.V.; Thomsen, M.E.; Justesen, D.L.; Schønheyder, H.C.; Lausen, M.; Birkelund, S. Complement mediated Klebsiella pneumoniae capsule changes. Microbes and infection. 2020, 22, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Zhao, G.; Chao, X.; Xie, L.; Wang, H. The characteristic of virulence, biofilm and antibiotic resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2020, 17, 17–6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diago-Navarro, E.; Calatayud-Baselga, I.; Sun, D.; Khairallah, C.; Mann, I.; Ulacia-Hernando, A.; Sheridan, B.; Shi, M.; Fries, B.C. Antibody-based immunotherapy to treat and prevent infection with hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 2017, 24, 1–e00456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Li, X.; An, H.; Wang, J.; Ding, M.; Wang, L.; Li, L.; Ji, Q.; Qu, F.; Wang, H.; Xu, Y. Capsule type defines the capability of Klebsiella pneumoniae in evading Kupffer cell capture in the liver. PLoS Pathogens. 2022, 18, 8–e1010693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, S.; Murphy, C.N. Epidemiology and virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Urinary Tract Infections: Molecular Pathogenesis and Clinical Management, 2017; 435-57. [Google Scholar]

- Chapelle, C.; Gaborit, B.; Dumont, R.; Dinh, A.; Vallee, M. Treatment of UTIs due to Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producers: how to use new antibiotic drugs? A narrative review. Antibiotics. 2021, 10, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarnagda, H.; Sagna, T.; Nadembega, W.M.; Ouattara, A.K.; Traoré, L.; Ouedraogo, R.A.; Bado, P.; Bazie, B.V.; Bouda, N.; Zongo, L.; Djigma, F.W. Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance of Urinary Tract Pathogens, with Molecular Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Acinetobacter spp., Using Multiplex Real-Time PCR. American Journal of Molecular Biology. 2024, 14, 4–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filev, R.; Lyubomirova, M.; Bogov, B.; Kolevski, A.; Pencheva, V.; Kalinov, K.; Rostaing, L. Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae and Prolonged Treatment with Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, M.M.; Wick, R.R.; Watts, S.C.; Cerdeira, L.T.; Wyres, K.L.; Holt, K.E. A genomic surveillance framework and genotyping tool for Klebsiella pneumoniae and its related species complex. Nature communications. 2021, 12, 1–4188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, V.B.; Singh, B.B.; Priyadarshi, N.; Chauhan, N.K.; Rajamohan, G. Role of novel multidrug efflux pump involved in drug resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae. PLoS One. 2014, 9, 5–e96288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kapoor, Garima; Saigal, Saurabh; Elongavan, Ashok. Action and resistance mechanisms of antibiotics: A guide for clinicians. Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology. 2017, 33, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousquet, A.; Henquet, S.; Compain, F.; Genel, N.; Arlet, G.; Decré, D. Partition locus-based classification of selected plasmids in Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica spp.: An additional tool. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2015, 110, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, A.; Hansen, L.H.; Sørensen, S.J. Conjugative plasmids: vessels of the communal gene pool. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2009, 364, 1527–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doménech-Sánchez, A.; Martínez-Martínez, L.; Hernández-Allés, S.; del Carmen Conejo, M.; Pascual, A.; Tomás, J.M.; Albertí, S.; Benedí, V.J. Role of Klebsiella pneumoniae OmpK35 porin in antimicrobial resistance. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2003, 47, 3332–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doorduijn, D.J.; Rooijakkers, S.H.; van Schaik, W.; Bardoel, B.W. Complement resistance mechanisms of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Immunobiology. 2016, 221, 1102–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedrakyan, A.; Gevorgyan, Z.; Zakharyan, M.; Arakelova, K.; Hakobyan, S.; Hovhannisyan, A.; Aminov, R. Molecular Epidemiology and In-Depth Characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Isolates from Armenia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025, 26, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Li, Y.; Ren, P.; Tian, D.; Chen, W.; Fu, P.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Jiang, X. Molecular epidemiology of hypervirulent carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2021, 11, 661218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, R.; Khanna, N.R.; Safadi, A.O.; et al. Bacitracin Topical. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. 2025. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536993/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Mezzatesta, M.L.; La Rosa, G.; Maugeri, G.; Zingali, T.; Caio, C.; Novelli, A.; Stefani, S. In vitro activity of fosfomycin trometamol and other oral antibiotics against multidrug-resistant uropathogens. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2017, 49, 763–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirel, L.; Héritier, C.; Tolün, V.; Nordmann, P. Emergence of oxacillinase-mediated resistance to imipenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2004, 48, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, G.-A.; Codiță, I.; Szekely, E.; Șerban, R.; Ruja, G.; Tălăpan, D. Ghid privind Enterobacteriaceele producătoare de carbapenemaze. 2016. ISBN 978-973-0-22283-8.

- Yang, S.K.; Yusoff, K.; Ajat, M.; Thomas, W.; Abushelaibi, A.; Akseer, R.; Lim, S.H.; Lai, K.S. Disruption of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae membrane via induction of oxidative stress by cinnamon bark (Cinnamomum verum J. Presl) essential oil. PloS one. 2019, 14, e0214326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, W.; Li, K.; Ji, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Shi, M.; Mi, Z. Carbapenem and cefoxitin resistance of Klebsiella pneumoniae strains associated with porin OmpK36 loss and DHA-1 β-lactamase production. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2013, 44, 435–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murri, R.; Fiori, B.; Spanu, T.; Mastrorosa, I.; Giovannenze, F.; Taccari, F.; Palazzolo, C.; Scoppettuolo, G.; Ventura, G.; Sanguinetti, M.; Cauda, R. Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole therapy for patients with carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae infections: retrospective single-center case series. Infection. 2017, 45, 209–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motley, M.P.; Fries, B.C. A new take on an old remedy: generating antibodies against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in a postantibiotic world. MSphere. 2017, 2, 10–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, B.M.; Hussein, A.H.; Hakim, T.A.; Fayez, M.S.; El-Shibiny, A. Phages for treatment of Klebsiella pneumoniae infections. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 2023, 200, 207–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nazzaro, F.; Fratianni, F.; De Martino, L.; Coppola, R.; De Feo, V. Effect of essential oils on pathogenic bacteria. Pharmaceuticals. 2013, 6, 1451–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Demerdash, A.S.; Alfaraj, R.; Farid, F.A.; Yassin, M.H.; Saleh, A.M.; Dawwam, G.E. Essential oils as capsule disruptors: enhancing antibiotic efficacy against multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2024, 15, 1467460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baptista, C.T.; Cerveira, M.M.; Barboza, V.; Maria, E.; Ferrer, K.; Miller, R.G.; Souza, T.D.; Zank, P.D.; Blanke, A.D.; Klein, V.P.; Rosado, R.P. A Systematic Review of Essential Oils’ Antimicrobial and Antibiofilm Activity against Klebsiella pneumoniae. Current Research in Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 2022; 6, 2577–201. [Google Scholar]

- Fournomiti, M.; Kimbaris, A.; Mantzourani, I.; Plessas, S.; Theodoridou, I.; Papaemmanouil, V.; Kapsiotis, I.; Panopoulou, M.; Stavropoulou, E.; Bezirtzoglou, E.E.; Alexopoulos, A. Antimicrobial activity of essential oils of cultivated oregano (Origanum vulgare), sage (Salvia officinalis), and thyme (Thymus vulgaris) against clinical isolates of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella oxytoca, and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Microbial ecology in health and disease. 2015, 26, 23289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, W.; Sun, Z.; Wang, T.; Yang, M.; Liu, M.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y. Antimicrobial activity of eugenol against carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and its effect on biofilms. Microbial pathogenesis. 2020, 139, 103924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisso Ndezo, B.; Tokam Kuaté, C.R.; Dzoyem, J.P. Synergistic antibiofilm efficacy of thymol and piperine in combination with three aminoglycoside antibiotics against Klebsiella pneumoniae biofilms. Canadian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Medical Microbiology. 2021, 1, 7029944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Rajivgandhi, G.N.; Ramachandran, G.; Alharbi, N.S.; Kadaikunnan, S.; Khaled, J.M.; Almanaa, T.N.; Manoharan, N. Preparative HPLC fraction of Hibiscus rosa-sinensis essential oil against biofilm forming Klebsiella pneumoniae. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2020, 27, 2853–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilcu, M.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Oprea, A.E.; Popescu, R.C.; Mogoșanu, G.D.; Hristu, R.; Stanciu, G.A.; Mihailescu, D.F.; Lazar, V.; Bezirtzoglou, E.; et al. Efficiency of Vanilla, Patchouli and Ylang Ylang Essential Oils Stabilized by Iron Oxide@C14 Nanostructures against Bacterial Adherence and Biofilms Formed by Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae Clinical Strains. Molecules. 2014, 19, 17943–17956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Antimicrobial class | Nr. | Antibiotic | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st evaluation | 2nd evaluation | |||

| Aminoglycosides | 1 | Amikacin (AK) | R | R |

| 2 | Streptomycin (S) | S | R | |

| 3 | Gentamicin (GME) | R | R | |

| Penicillins | 4 | Penicillin (PEN) | R | R |

| 5 | Oxacillin (OX) | R | R | |

| 6 | Ampicillin–sulbactam (SAM) | R | R | |

| 7 | Piperacillin (PRL) | R | R | |

| 8 | Mecillinam (MEC) | R | R | |

| 9 | Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (AMC) | R | R | |

| Macrolides | 10 | Azithromycin (AZM) | R | R |

| 11 | Clarithromycin (CLR) | R | R | |

| 12 | Tulathromycin (TUL) | S | R | |

| 13 | Spiramycin (SP) | R | R | |

| Polypeptides | 14 | Bacitracin (DTD) | R | R |

| Polymyxins | 15 | Colistin (CT) | R | R |

| Phosphonic acid derivatives | 16 | Fosfomycin (FF) | R | R |

| Cephalosporins ⮚ 1st generation |

17 | Cefadroxil (CFR) | R | R |

| 18 | Cephradine (CE) | R | R | |

| 19 | Cefacetrile (CEF) | R | R | |

| 20 | Cephalothin (CH) | R | R | |

| ⮚ 2nd generation | 21 | Cefaclor (CEC) | R | R |

| 22 | Cefotetan (CTT) | R | R | |

| 23 | Cefuroxime (CXM) | R | R | |

| 24 | Cefamandole (MA) | R | R | |

| ⮚ 3rd generation | 25 | Ceftriaxone (CRO) | R | R |

| 26 | Ceftazidime (CAZ) | R | R | |

| 27 | Cefoperazone (CEP) | R | R | |

| 28 | Ceftiofur (FUR) | R | R | |

| 29 | Cefixime (CFM) | R | R | |

| 30 | Ceftazidime-avibactam (CZA) | R | R | |

| ⮚ 4th generation | 31 | Cefquinome (CFQ) | R | R |

| Carbapenems | 32 | Meropenem (MEM) | R | R |

| 33 | Imipenem (IMI) | R | R | |

| Streptogramins | 34 | Pristinamycin (PT) | R | R |

| Aminocoumarins | 35 | Novobiocin (NV) | R | R |

| Fluoroquinolones | 36 | Norfloxacin (NX) | R | R |

| 37 | Ofloxacin (OFX) | R | R | |

| 38 | Marbofloxacin (MAR) | R | R | |

| Tetracyclines | 39 | Tetracycline (TET) | S | S |

| 40 | Doxycycline (DOX) | S | R | |

| Rifamycins | 41 | Rifampicin (RD) | R | R |

| Amphenicols | 42 | Chloramphenicol (C) | S | R |

| Fusidic acid | 43 | Fusidic acid (FA) | R | R |

| Chemotherapeutic agents | 44 | Furazolidone (FX) | R | R |

| 45 | Nitrofurantoin (F) | R | R | |

| 46 | Metronidazole (MET) | R | R | |

| Sulfonamides | 47 | Sulfonamide compound (S3) | R | R |

| 48 | Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (SXT) | R | R | |

| 06 Feb 2024 – Urine culture with antibiogram: > 100,000 CFU mL−1, K. pneumoniae | ||

|---|---|---|

| Susceptible to three agents: colistin, gentamicin, and fosfomycin. | Resistance to 17 agents: amikacin, ampicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, aztreonam, ceftazidime, cefuroxime, cefepime, cefotaxime, ciprofloxacin, imipenem, nitrofurantoin, piperacillin, tobramycin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, piperacillin–tazobactam, meropenem, and ertapenem. |

Observations Treatment with fosfomycin Over time, the strain became resistant to fosfomycin. |

| 05 Mar 2024 – Urine culture: < 1,000 CFU mL−1; not clinically significant. | ||

| 23 Sep 2024 – Urine culture: < 1 000 CFU mL−1; not clinically significant. | ||

| 22 Nov 2024 – Urine culture with antibiogram: > 100,000 CFU mL−1, K. pneumoniae | ||

|

Susceptible to four agents: amikacin, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, gentamicin, and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole Intermediate susceptibility to two agents: ceftazidime and cefepime |

Resistant to two agents: piperacillin–tazobactam and levofloxacin | Treatment with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole |

| 13 Dec 2024 – Urine culture with antibiogram: > 100,000 CFU mL−1, K. pneumoniae | ||

| Susceptible to two agents: colistin and tigecycline | Resistant to 14 agents: amikacin, aztreonam, ceftazidime, cefepime, cefotaxime, ciprofloxacin, gentamicin, imipenem, tobramycin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, piperacillin–tazobactam, meropenem, levofloxacin, and ertapenem | Over time, the strain became resistant to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole |

| 26 Feb 2025 – Urine culture: < 1 000 CFU mL−1; not clinically significant. | ||

| 25 Apr 2025 – Urine culture with antibiogram: 10,000–100,000 CFU mL−1, K. pneumoniae | ||

| Susceptible to two agents: gentamicin and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole | Resistant to ten agents: ampicillin, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefpodoxime, ciprofloxacin, meropenem, levofloxacin, ertapenem, and cefixime | Susceptibility to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole is once again observed. |

| International name | Latin name/composition | Inhibition area diameter (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| Palmarosa | Cymbopogon martini | 11 |

| Geranium | Pelargonium graveolens | R |

| Frankincense | Boswellia carteri | R |

| Laurel | Laurus nobilis | 12 |

| Tea tree | Melaleluca alternifolia | 20 |

| Citronella | Cymbopogon nardus | R |

| Thyme | Thymus vulgaris | 22 |

| Propolis | Apis mellifera propolis | R |

| Biomicin urinar® (A20) |

Origani aetheroleum + Cinnamomun verum + Salvia officinalis + Thymi aetheroleum |

12 (resistant colonies) |

| Biomicin forte® (A3) |

Thymi aetheroleum + Caryophylli floris aetheroleum |

30 |

| Methylene blue 3% | - | 13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).