1. Introduction

Rehabilitating wildlife species and understanding the effects of pathogens and infectious diseases are crucial aspects of veterinary medicine. These efforts improve the health and survival of wildlife and safeguard human populations from zoonotic threats [

1]. Infectious diseases pose a significant threat to the conservation of wild species, such as the southern pudu (

Pudu puda), one of the smallest deer species in the world. Their conservation status is vulnerable, with declining populations mainly due to anthropogenic effects, including roadkill, forest fires, and free-roaming dog attacks [

2]. There is molecular and serological evidence of the presence of potential pathogens in the southern pudu [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Therefore, the only documented case linking specific infectious agents to disease in this species is the association of mycotic pneumonia caused by Aspergillus fumigatus or Mucor spp. and encephalitis caused by

Curvularia spicifera in zoo-captive southern pudus [

7].

Wildlife microbiology forensic science is currently an underexplored field; however, it can help to investigate the causes of unusual wildlife mortality or death in individuals in captivity in rehabilitation centers [

8]. The whole genome sequencing (WGS) is a valuable and versatile tool, and its use in clinical settings has been proposed to investigate the genomics of infectious diseases [

9]. Its application in the forensic field is noteworthy, as it allows genomic epidemiology and microbial genomics, identifying the origin and potential spread of infectious pathogens [

10].

This study aims to analyze the genomic characteristics of infection-causing bacterial pathogens and investigate the cause of death of a specimen of P. puda, admitted to a Wildlife Rehabilitation Center in Chile.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Background and Sample Collection

In 2023, during the forest fires in the south-central zone of Chile, the Wildlife Rehabilitation Center at the University of Concepcion received an adult male southern pudu from Florida, Biobio region, Chile. The patient had wounds in the lumbosacral area attributed to dog bites and burned right hind limb, both of which showed signs of infection. The deer received empiric fluoroquinolone (i.e.

, enrofloxacin, 5 mg/kg, IM, q. 24 h), with unsuccessful results. Swabs from both injuries were taken for microbiological culture. The patient passed away thirteen days after being admitted. At necropsy, an intracardiac blood sample was collected. Additionally, an oval nodule measuring 70 x 100 mm was identified in the abdominal cavity. It had a smooth external surface, firm consistency, and calcified yellowish-white content, which was also sampled (

Figure S1).

2.2. Isolation and Bacterial Identification

For samples from wounds and the internal abdominal nodule, microbiological cultures were performed using brain-heart agar, blood agar, and MacConkey agar, and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. For an intracardiac blood sample, the culture was initially grown in brain-heart infusion broth for 24 hours at 37°C, and subsequently transferred to brain-heart agar, blood agar, and MacConkey agar for an additional 24-hour incubation at 37°C. Preliminary bacterial identification was performed through API

® 20E

TM or API

® 20NE

TM systems (BioMérieux, France). For the susceptibility testing, the selection of antibiotics varied according to the analyzed bacteria, including cefazolin, cefovecin, ceftriaxone, cefoperazone, ceftazidime, cefoxitin, cefoxitin, cefotaxime, cefepime, amoxicillin/clavulanate, piperacillin/tazobactam, imipenem, meropenem, tetracycline, gentamicin, amikacin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, enrofloxacin, and levofloxacin. Susceptibility interpretation followed the protocols and cutoff points established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [

11,

12].

Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as a control strain.

2.3. Whole Genome Sequencing and Genomic Characterization

Total genomic DNA of the bacterial isolates was extracted using the InstaGene™ Matrix (Bio-Rad Laboratories) extraction method and subjected to WGS using the Illumina NextSeq 2000 platform. Genomic assembly was performed using the Shovill (Version 1.1.0) with the SKESA assembler, available in the Galaxy web-based platform (

https://usegalaxy.org/). For

E. coli, multilocus sequence type (MLST), resistome, serotype prediction, and plasmid replicons were identified using MLST 2.0, ResFinder 4.1.0, SerotypeFinder 2.0, and PlasmidFinder 2.1, respectively, available from the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (

http://genomicepidemiology.org/). For the virulome analysis, the VFDB database (

https://www.mgc.ac.cn/VFs/) was used. For

Klebsiella oxytoca, the MLST, resistome, virulome, and plasmid replicons were analyzed using the same databases as those for

E. coli. For

Acinetobacter baumannii, the Pasteur scheme was used for MLST analysis available in the PubMLST database (

https://pubmlst.org/organisms/acinetobacter-baumannii); while resistome and virulome were obtained from ResFinder 4.1.0 and VFDB, respectively. The

A. baumannii capsule was also typed using the Kaptive online tool (

https://kaptive-web.erc.monash.edu/) to predict serotypes (K-type and O-type). For all strains, mutations in quinolone resistance-determining regions (QRDR) were searched using the CARD database (

https://card.mcmaster.ca/home). For all predicted resistance genes, a ≥ 97% identity/coverage threshold was used as a filter for identification. For virulome and plasmid replicons, the default results were considered for each database. The raw data is available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1269607.

2.4. Phylogenetic and Clonality Analysis

To elucidate the phylogenetic relationship of the two

E. coli ST224, the genomic sequences of our isolates were deposited in the Enterobase database (

https://enterobase.warwick.ac.uk/). Subsequently, a phylogenomic analysis was conducted using the cgMLST V1 + HierCC V1 scheme and MSTree V2 algorithms. This analysis included 737 available genome sequences of

E. coli ST224, containing information regarding the sample origin, country, and collection year (

Table S1). To determine clonality among strains, the clade including our

E. coli ST224 strains was subjected to single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis using the CSI Phylogeny 1.4 platform of the Center for Genomic Epidemiology, and clonality was interpreted according to Schürch et al. (2018). Closely related genome assemblies (less than 100 SNP differences) were selected to construct the final SNP-based phylogenetic tree (

Table S2). The resistome of the closely related genome assemblies was obtained using the databases previously utilized with

E. coli to compare genomic and epidemiological data.

3. Results

3.1. Bacterial Isolation and Antimicrobial Susceptibility

From infected wounds in the lumbosacral area attributed to dog bites, a

K. oxytoca MVL-12-23 strain was isolated. From burn wounds on extremities and intracardiac blood samples,

E. coli MVL-11-23 and MVL-123-23 strains were isolated, respectively. Finally, from the oval nodule detected at the necropsy, the

A. baumannii MVL-13-23 strain was detected.

K. oxytoca MVL-12-23 strain exhibits phenotypic resistance to cefazolin, tetracycline, gentamicin, chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and enrofloxacin. The two

E. coli, MVL-11-23 and MVL-123-23 strains, displayed resistance to cefazolin, cefovecin, ceftriaxone, gentamicin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, enrofloxacin, and intermediate resistance to cefoperazone, amoxicillin/clavulanate, and amikacin. A. baumannii MVL-13-23 strain exhibits intermediate resistance to cefotaxime (

Table 1).

3.2. Genomic Characterization of Infection-Causing Bacteria in Southern Pudu

The

K. oxytoca MVL-12-23 strain belonged to the ST145 lineage, carrying resistance determinant genes against beta-lactams (

blaOXY-2-10), aminoglycosides [

aadA1,

aadA5,

aac(3)-Iia], macrolides [

mph(A)], phenicols (

catA1), tetracyclines [

tet(B)], sulfonamides (

sul1), and trimethoprim (

dfrA17). In addition, it has mutations in the

gyrA (S83I) and

gyrB (S463A) QRDR, associated with fluoroquinolone resistance (

Table 2). The virulome comprised genes conferring bacterial adherence

, iron uptake, secretion systems, efflux pumps, nutritional factor, virulence regulation, cell surface components, magnesium uptake, protease, and stress adaptation (

Table S3). The plasmid replicons detected were

IncFIB(K) and

IncM1 (

Table 2).

The two

E. coli strains belonged to the same ST224 lineage. The resistome was composed of genes conferring resistance to beta-lactams (

blaCTX-M-1), aminoglycosides [

aac(3)-IId,

aph(3’)-Ia,

aph(3’’)-Ib,

aph(6)-Id], macrolides [

mph(A)], sulfonamides (

sul2), and trimethoprim (

dfrA17). In addition,

E. coli strains displayed mutations in QRDR

gyrA (D87N and S83L) and

parC (S80I) genes, which confer resistance to fluoroquinolones. The serotype prediction of both

E. coli strains was O126:H23 (

Table 2).

For

E. coli MVL-11-23 strain the virulome includes virulence factors associated to adherence, invasion, iron uptake, toxin, autotransporter, non-lee encoded ttss effectors, secretion system, and

Yersinia O antigen (

Table S3). On the other hand,

E. coli MVL-123-23 strain carried a virulome composed by genes encoding for adherence

, invasion, iron uptake, secretion systems, toxins, endotoxin, serum resistance, immune evasion, antiphagocytosis, magnesium uptake, quorum sensing, motility, autotransporter, non-lee encoded ttss effectors, virulence regulation, aminoacid and purine metabolism, anaerobic respiration, cell surface components, chemotaxis and motility, efflux pump, enolase enzyme, lipid and fatty acid metabolism, nutritional virulence, stress adaptation, acyltransferases and

Yersinia O antigen (

Table S3).

The plasmid replicons detected were IncM1, p0111, and IncQ1 for E. coli MVL-11-23 strain and p0111 and IncQ1 for E. coli MVL-123-23 strain.

The

A. baumannii MVL-13-23 strain belonged to ST1365 and serotype KL138, OCL1. It harbored a resistance gene

blaOXA-413 that confers resistance to beta-lactams, as well as mutations in

parC (V104I and D105E) QRDR. The virulome comprises genes that confer characteristics such as bacterial adherence, biofilm formation, iron uptake, quorum sensing, phospholipases, immune evasion, serum resistance, sensor kinases, and catalase (

Table S3).

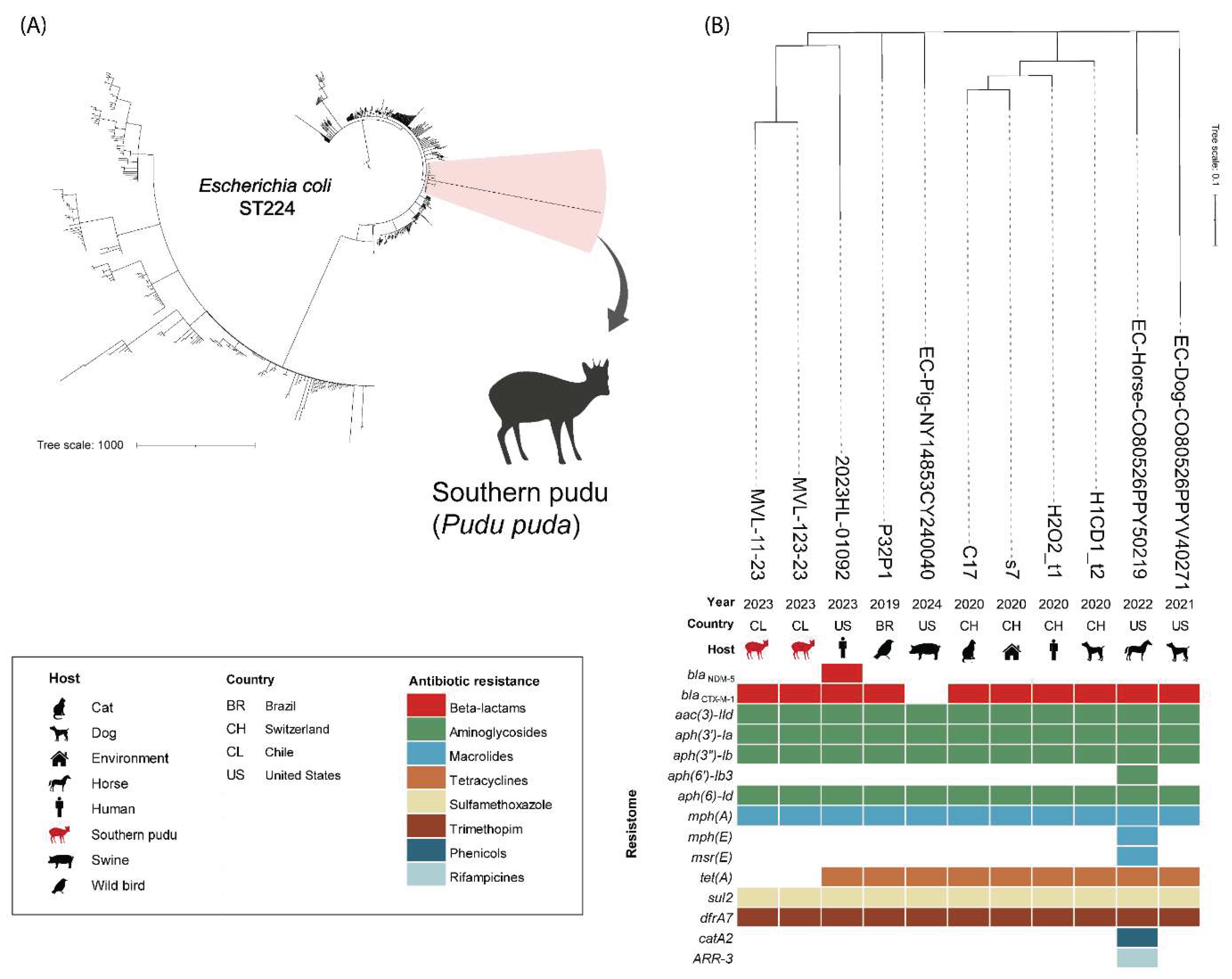

3.3. Phylogenetic and Clonality Analysis of E. coli ST224

The initial phylogeny of

E. coli ST224 was conducted with 737 genome assemblies from different countries around the world that met the established criteria (host, country, and year of collection data) (

Table S2). The two

E. coli strains isolated from

P. puda were closely related (<100 SNPs of difference) to strains from Brazil (wild bird), Switzerland (human, cat, dog, and house environment), and the United States (human, pig, horse, and dog) (

Table S2).

The collection years ranged from 2019 to 2024 (

Figure 1). The resistome comparison of the strains includes resistance genes to beta-lactams (

blaNDM-5,

blaCTX-M-1), aminoglycosides [

aac(3)-IId,

aph(3’)-Ia,

aph(3’’)-Ib,

aph(6’’)-Ib3, aph(6)-Id], macrolides [

mph(A), mph(E), msr(E)], tetracyclines [

tet(A)], sulfamethoxazole (

sul2) trimethoprim

(dfrA17), phenicols (

catA2) and rifampicin (

ARR-3) antibiotics (

Figure 1). The

E. coli MVL-11-23 strain isolated from the infected wound differed by five SNPs from the

E. coli MVL-123-23 strain isolated from the cardiac blood sample.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the genomic characteristics of a triple bacterial co-infection in a vulnerable P. puda impacted by anthropogenic activities with a fatal outcome, using WGS as a relevant tool in the forensic field.

Wildfires result in the loss of millions of hectares annually due to uncontrolled blazes, severely impacting the environment, wildlife, and human life [

14]. These disasters have a profound impact on biodiversity, leading to habitat loss, reductions in the population sizes of both flora and fauna, alterations in ecosystems, and environmental pollution [

15,

16,

17]. While wildlife has evolved an escape response to fire, this does not guarantee survival in the face of such events [

18,

19,

20]. As in the case described in this paper, disoriented escaped animals can be seen as prey of domestic or wild carnivores. On the other hand, wildlife that survives wildfires may be directly impacted by secondary infections due to wound contamination, which reduces the chances of survival for the burned animals [

21].

E. coli is a diverse bacterial species comprising both commensal and pathogenic strains capable of causing intestinal and extraintestinal diseases in humans and animals. Advances in genomics have revealed that acquiring virulence-associated genes through horizontal gene transfer plays a key role in its pathogenic potential [

22]. In this context, the southern pudu suffered from a secondary bacterial infection in its burned right hind limb caused by a multidrug-resistant CTX-M-1-producing

E. coli ST224, progressing from local soft tissue infection to fatal sepsis. This was confirmed by SNP and virulome analyses, which verified that it was an

E. coli ST224 clone identified in the bloodstream sample (with five SNPs of difference) [

13]. However, the strain recovered from blood carried a more extensive virulome, which may have contributed to an increased pathogenic potential. Detected genes that encode for bacterial invasion, iron uptake, hemolysins, antiphagocytosis, chemotaxis and motility, endotoxin, immune evasion, quorum sensing, serum resistance, and stress adaptation could have facilitated the septicemia and fatal outcome of the case [

23,

24]. Unfortunately, we cannot confirm the specific mobile genetic elements (MGEs) carrying this extra virulome due to the short-read sequencing that does not allow a correct assembly of plasmids or other MGEs [

25]. On the other hand, limited therapeutic options due to the antimicrobial resistance determinants, including the production of the extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) CTX-M-1 by the strain, contributed to the death of the animal. ESBL-producing Enterobacterales are classified within the critical priority group of the WHO list, and the presence of this type of enzyme produced by

E. coli complicates the treatment of patients [

26]. Identifying

E. coli ST224 lineage in the southern pudu adds to those reported worldwide in diverse hosts such as humans, pets, livestock, wildlife, and the environment [

27]. This demonstrates that this One Health lineage adapts to different species and hospital and wild environments.

In addition to the

E. coli infection, the patient had an infection in a dog bite wound where a multidrug-resistant

K. oxytoca ST145 was isolated, being the first report in wildlife. This lineage has been described in Poland, China, and Spain as an emerging pathogen primarily causing nosocomial post-surgical or wound infections in humans [

28,

29,

30,

31]. This increases the need to monitor the environment of wildlife rehabilitation centers and wild patients with secondary wound infections. Both

E. coli ST224 and

K. oxytoca ST145 were resistant to fluoroquinolones due to point mutations in quinolone resistance-determining regions, leading to the therapeutic failure with the empiric enrofloxacin administered.

Finally,

A. baumannii ST1365 was a pathological finding in the southern pudu, establishing the first confirmed report of this bacterium by WGS in wildlife. While not characteristic, such presentations highlight the potential of

A. baumannii to induce focal, nodular pathology under certain clinical conditions [

32,

33]. The duration and underlying causes of the lesion caused by

A. baumannii in the southern pudu remain unknown. Although this pathogen is well studied in human medicine, its pathogenic potential in animals warrants further investigation [

34,

35].

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the utility of whole genome sequencing (WGS) as a powerful tool for forensic microbiology in wildlife, enabling the precise characterization of pathogens responsible for fatal infections. The investigation of a deceased southern pudu revealed a complex case of a triple bacterial infection involving E. coli ST224, K. oxytoca ST145, and A. baumannii ST1365, exhibiting significant antimicrobial resistance and extensive virulence gene repertoires. The detection of CTX-M-1-producing E. coli ST224 emphasizes the One Health implications of multidrug-resistant bacteria circulating across human, animal, and environmental reservoirs. This study demonstrates that the same E. coli ST224 clone, initially isolated from a wound infection, could cause fatal septicemia in the southern pudu, underscoring the pathogen’s adaptability and virulent potential in wildlife hosts. The findings also underscore the underexplored role of opportunistic pathogens such as A. baumannii and K. oxytoca in wildlife health. This case study exemplifies the importance of implementing genomic epidemiology in wildlife rehabilitation settings to detect, monitor, and understand the emergence and spread of infectious diseases, ultimately contributing to wildlife conservation efforts and safeguarding public health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org, Figure S1: Photography of lesions in the southern pudu during the necropsy. A, wounds in the lumbosacral area; B, burn wounds; C, internal abdominal nodule detected at the necropsy; Table S1: Epidemiological data of genomic assemblies of

Escherichia coli ST224 available in the Enterobase database; Table S2: Matrix of SNP-based phylogeny analysis of closely related genome assemblies of

Escherichia coli ST224; Table S3: Virulence genes (virulome) according to the virulence factor class of

Klebsiella oxytoca,

Escherichia coli, and

Acinetobacter baumannii strains isolated from southern pudu.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.A. and D.F.; methodology, V.A. and F.R.; validation, N.L., P.A. and D.F.; formal analysis, V.A. and D.F.; investigation, V.A., F.R. and C.M.; resources, P.A.; data curation, D.F.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A.; writing—review and editing, N.L. and D.F.; supervision, P.A. and D.F.; funding acquisition, V.A. and D.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (ANID), FONDECYT Iniciación grant number 11241097, and BECAS/DOCTORADO NACIONAL grant number 21242196, and Vicerrectoría de Investigacion y Desarrollo Universidad de Concepción (VRID) grant number 2023000789INI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data are available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1269607.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Servicio Agricola y Ganadero (SAG) of Chile, the entire medical staff at the Hospital Clínico Veterinario of the Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad de Concepción, and all the volunteers at the Centro de Rehabilitación de Fauna Silvestre, Universidad de Concepción.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WGS |

Whole-genome sequencing |

| MLST |

Multilocus sequence type |

| ST |

Sequence type |

| ESBL |

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase |

References

- Cunningham, A.A.; Daszak, P.; Wood, J.L.N. One health, emerging infectious diseases and wildlife: two decades of progress? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2017, 372, 20160167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SIMBIO Pudu puda Molina, 1782 Available online:. Available online: https://simbio.mma.gob.cl/Especies/Details/4604#estadoconservacion (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Hidalgo-Hermoso, E.; Celis, S.; Cabello, J.; Kemec, I.; Ortiz, C.; Lagos, R.; Verasay, J.; Moreira-Arce, D.; Vergara, P.M.; Vera, F.; Esperon, F. Molecular survey of selected viruses in pudus (Pudu Puda) in Chile revealing first identification of Caprine Herpesvirus—2 (CpHV-2) in South American ungulates. Veterinary Quarterly 2023, 43, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mengual-Chuliá, B.; Wittstatt, U.; Olias, P.; Bravo, I.G. Genome sequences of two novel Papillomaviruses isolated from healthy skin of Pudu Puda and Cervus Elaphus deer. Genome Announc 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verdugo, C.; Jiménez, O.; Hernández, C.; Álvarez, P.; Espinoza, A.; González-Acuña, D. Infection with Borrelia Chilensis in Ixodes Stilesi ticks collected from Pudu puda deer. Ticks Tick Borne Dis 2017, 8, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hidalgo-Hermoso, E.; Verasay Caviedes, S.; Pizarro-Lucero, J.; Cabello, J.; Vicencio, R.; Celis, S.; Ortiz, C.; Kemec, I.; Abuhadba-Mediano, N.; Asencio, R.; et al. High exposure to livestock pathogens in southern pudu (Pudu Puda) from Chile. Animals 2024, 14, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, R.S.; Cole, G.A.; LaDouceur, E.E.B.; McAloose, D.; Sykes, J.M.; Dennison-Gibby, S.; D’Agostino, J. Mycotic pneumonia and encephalitis in southern pudu (Pudu puda). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine 2021, 52, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, A.; Lennard, C.; Roux, C. Forensic science: where to from here? Forensic Sci Int 2025, 366, 112285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brlek, P.; Bulić, L.; Bračić, M.; Projić, P.; Škaro, V.; Shah, N.; Shah, P.; Primorac, D. Implementing whole genome sequencing (WGS) in clinical practice: advantages, challenges, and future perspectives. Cells 2024, 13, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Massey, S.E. Comparative microbial genomics and forensics. Microbiol Spectr 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CLSI CLSI M100 Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2025; ISBN 9781684402625.

- CLSI CLSI VET01STM Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated From Animals. A CLSI Supplement for Global Application. 7th Edition; 7th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2024; ISBN 9781684402113.

- Schürch, A.C.; Arredondo-Alonso, S.; Willems, R.J.L.; Goering, R.V. Whole genome sequencing options for bacterial strain typing and epidemiologic analysis based on single nucleotide polymorphism versus gene-by-gene–based approaches. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2018, 24, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, Z.A.; Khorram-Manesh, A.; Goniewicz, K. Global Health Impacts of Wildfire Disasters From 2000 to 2023: A comprehensive analysis of mortality and injuries. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2024, 18, e230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S.M.; Harrisson, K.A.; Clarke, R.H.; Bennett, A.F.; Sunnucks, P. Limited population structure, genetic drift and bottlenecks characterise an endangered bird species in a dynamic, fire-prone ecosystem. PLoS One 2013, 8, e59732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, L.T.; Giljohann, K.M.; Duane, A.; Aquilué, N.; Archibald, S.; Batllori, E.; Bennett, A.F.; Buckland, S.T.; Canelles, Q.; Clarke, M.F.; Fortin, M.; Hermoso, V.; Herrando, S.; Keane, R.; Lake, F.; McCarthy, M.; Morán-Ordóñez, A.; Parr, C.; Pausas, J.; Penman, T.; Regos, A.; Rumpff, L.; Santos, J.; Smith, A.; Syphard, A.; Tingley, M.; Brotons, L. Fire and Biodiversity in the Anthropocene. Science (1979) 2020, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ballarin, C.S.; Mores, G.J.; Alcarás de Goés, G.; Fidelis, A.; Cornelissen, T. Trends and gaps in the study of fire effects on plant–animal interactions in Brazilian ecosystems. Austral Ecol 2024, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hairston, N.G.; Ellner, S.P.; Geber, M.A.; Yoshida, T.; Fox, J.A. Rapid evolution and the convergence of ecological and evolutionary time. Ecol Lett 2005, 8, 1114–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, T.; Morrissey, M.B.; de Villemereuil, P.; Alberts, S.C.; Arcese, P.; Bailey, L.D.; Boutin, S.; Brekke, P.; Brent, L.J.N.; Camenisch, G.; Charmantier, A.; Clutton-Brock, T.; Cockburn, A.; Coltman, D.; Courtiol, A.; Davidian, E.; Evans, S.; Ewen, J.; Festa-Bianchet, M.; de Franceschi, C.; Gustafsson, L.; Höner, O.; Houslay, T.; Keller, L.; Manser, M.; McAdam, A.; McLean, E.; Nietlisbach, P.; Osmond, H.; Pemberton, J.; Postma, E.; Reid, J.; Rutschmann, A.; Santure, A.; Sheldon, B.; Slate, J.; Teplitsky, C.; Visser, M.; Wachter, B.; Kruuk, L. Genetic variance in fitness indicates rapid contemporary adaptive evolution in wild animals. Science (1979) 2022, 376, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geary, W.L.; Doherty, T.S.; Nimmo, D.G.; Tulloch, A.I.T.; Ritchie, E.G. Predator responses to fire: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Animal Ecology 2020, 89, 955–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albery, G.F.; Turilli, I.; Joseph, M.B.; Foley, J.; Frere, C.H.; Bansal, S. From flames to inflammation: how wildfires affect patterns of wildlife disease. Fire Ecology 2021, 17, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desvaux, M.; Dalmasso, G.; Beyrouthy, R.; Barnich, N.; Delmas, J.; Bonnet, R. Pathogenicity factors of genomic islands in intestinal and extraintestinal Escherichia coli. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, A.C.M.; Zidko, A.C.M.; Pignatari, A.C.; Silva, R.M. Assessing the diversity of the virulence potential of Escherichia coli isolated from bacteremia in São Paulo, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research 2013, 46, 968–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankel, G.; Eliora, Z.R. Escherichia coli, a Versatile Pathogen, Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; 242.

- De Maio, N.; Shaw, L.P.; Hubbard, A.; George, S.; Sanderson, N.D.; Swann, J.; Wick, R.; AbuOun, M.; Stubberfield, E.; Hoosdally, S.J.; Crook, D.; Peto, T.; Sheppard, A.; Bailey, M.; Read, D.; Anjum, M.; Walker, A.; Stoesser, N. Comparison of long-read sequencing technologies in the hybrid assembly of complex bacterial genomes. Microb Genom 2019, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sati, H.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Hansen, P.; Garlasco, J.; Campagnaro, E.; Boccia, S.; Castillo-Polo, J.A.; Magrini, E.; Garcia-Vello, P.; Wool, E.; Gigante, V.; Duffy, E.; Cassini, A.; Huttner, B.; Pardo, P.; Naghavi, M.; Mirzayev, F.; Zignol, M.; Cameron, A.; Tacconelli, E.; Aboderin, A.; Al Ghoribi, M.; Al-Salman, J.; Amir, A.; Apisarnthanarak, A.; Blaser, M.; El-Sharif, A.; Essack, S.; Harbarth, S.; Huang, X.; Kapoor, G.; Knight, G.; Muhwa, J.; Monnet, D.; Ousassa, T.; Sacsaquispe, R.; Severin, J.; Sugai, M.; Taneja, N.; Umubyeyi Nyaruhirira, A. The WHO bacterial priority pathogens list 2024: a prioritisation study to guide research, development, and public health strategies against antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect Dis 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, M.M.; Sellera, F.P.; Furlan, J.P.R.; Aravena-Ramírez, V.; Fuentes-Castillo, D.; Fuga, B.; dos Santos Fróes, A.J.; de Sousa, A.L.; Garino Junior, F.; Lincopan, N. Gut colonization of semi-aquatic turtles inhabiting the Brazilian Amazon by international clones of CTX-M-8-producing Escherichia coli. Vet Microbiol 2025, 301, 110344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Izdebski, R.; Baraniak, A.; Żabicka, D.; Sękowska, A.; Gospodarek-Komkowska, E.; Hryniewicz, W.; Gniadkowski, M. VIM/IMP carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in Poland: epidemic Enterobacter hormaechei and Klebsiella oxytoca lineages. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2018, 73, 2675–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabello, M.; Hernández-García, M.; Maruri-Aransolo, A.; Michelena, M.; Pérez-Viso, B.; Ponce-Alonso, M.; Cantón, R.; Ruiz-Garbajosa, P. Occurrence of multi-carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales in a tertiary hospital in Madrid (Spain): a new epidemiologic scenario. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2024, 38, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, W.; Yang, X.; Yu, H.; Wang, M.; Jia, W.; Huang, B.; Qu, F.; Shan, B.; Tang, Y.-W.; Chen, L.; Du, H. Genomic characterization of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella Oxytoca complex in China: a multi-center study. Front Microbiol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biedrzycka, M.; Urbanowicz, P.; Żabicka, D.; Hryniewicz, W.; Gniadkowski, M.; Izdebski, R. Country-wide expansion of a VIM-1 carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella Oxytoca ST145 lineage in Poland, 2009–2019. European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 2023, 42, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslow, J.M.; Meissler, J.; Hartzell, R.R.; Spence, P.B.; Truant, A.; Gaughan, J.; Eisenstein, T.K. Innate immune responses to systemic Acinetobacter Baumannii infection in mice: neutrophils, but not interleukin-17, mediate host resistance. Infect Immun 2011, 79, 3317–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dexter, C.; Murray, G.L.; Paulsen, I.T.; Peleg, A.Y. Community-acquired Acinetobacter Baumannii : clinical characteristics, epidemiology and pathogenesis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2015, 13, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kolk, J.H.; Endimiani, A.; Graubner, C.; Gerber, V.; Perreten, V. Acinetobacter in veterinary medicine, with an emphasis on Acinetobacter Baumannii. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2019, 16, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Kolk, J.H. Acinetobacter Baumannii as an underestimated pathogen in veterinary medicine. Veterinary Quarterly 2015, 35, 123–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).