1. Introduction

Madagascar holds approximately 5% of global biodiversity with high endemism[

1], yet faces escalating threats from wildlife trafficking, illegal logging, and habitat loss. The country has legally designated 125 protected areas and 1,444 through Community-based management (COBA or VOI) co-managed zones covering 3.8 million hectares[

2]. The Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MEDD) promotes decentralized conservation, aligning with international frameworks such as Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), while emphasizing social equity and ecological sovereignty. Ecotourism linked to protected areas contributes nearly 12% of Madagascar’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP)[

3].

Since the early 2000s, the Government of Madagascar has engaged in significant reforms in biodiversity governance, particularly with the establishment of the System of Protected Areas of Madagascar (SAPM

1) in 2005 and subsequent strategic partnerships with NGOs, donors, and communities[

4]. The Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MEDD) has since strengthened its legal frameworks, promoted the delegation of protected area management to civil society and local communities, and developed digital governance tools such as the “Système d’Information sur la Gestion des Aires Protégées” or SIGAP [

5].

The 2024 interim report of the National Strategy to Combat Wildlife Trafficking confirms that over 120 international seizures involving Malagasy species have been recorded since 2000, highlighting the urgent need for systemic responses [

6]. In addition to these threats, weak institutional coordination, corruption, and limited community incentives hinder the sustainability of conservation efforts.

This case study examines how these efforts affect protected area governance, especially through Community-based management (COBA or VOI), mapping technologies (SIGAP), and effectiveness assessments using the Integrative Management Effectiveness Tool (IMET) and Management effectiveness tracking Tool (METT). It aims to contribute lessons relevant to the Satoyama Initiative [

7]. and other socio-ecological production landscapes.

IMET is a structured, data-driven tool developed by IUCN and its partners to assess and enhance the management of protected and conserved areas. It enables site managers and stakeholders to evaluate management effectiveness, identify strengths and weaknesses, and prioritize actions for improvement. IMET focuses on key components such as planning, governance, resource management, threat assessment, and monitoring. It stands out by using a digital platform for standardized data collection and analysis, offering dashboards and maps to highlight spatial and operational gaps, and supporting adaptive management by linking indicators to decision-making. IMET is also typically implemented through collaborative workshops involving site managers, technical teams, and sometimes local communities. It has been used across many African and tropical countries, including Madagascar, to promote transparency, track performance, and build capacity in protected area management.

METT refers to the Management Effectiveness Tracking Tool, a standardized questionnaire-based assessment developed by WWF and the World Bank. It is used globally to evaluate how effectively protected areas are managed, based on criteria such as governance, enforcement, community engagement, and ecological outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This study employed a mixed-method, country-level case study approach to evaluate conservation governance in Madagascar, with a particular focus on responses to wildlife trafficking. The methodology integrates policy analysis, geospatial data interpretation, and stakeholder engagement to assess both institutional frameworks and on-the-ground implementation.

The analysis drew upon multiple validated datasets and documentation, including:

Official government reports, such as the 2024 Interim Report on the National Strategy to Combat Wildlife Trafficking [

6];

Legal texts and decrees, including Madagascar’s Environmental Charter, Law No. 2001-005 on Protected Areas (COAP), and the SAPM decree [

4];

Geospatial and performance data from the SIGAP platform, which tracks protected area management, VOI agreements, and IMET/METT scores [

5];

FAPB

2 financial and technical reports, documenting performance-based funding and co-management results in 37 protected areas cf. [

8];

External enforcement and seizure data sourced from TRAFFIC [

9], INTERPOL [

10], and the CITES Trade Database [

11].

Policy and institutional review assessed legal consistency, decentralization trends, and alignment with international conventions (e.g., CITES);

Geospatial analysis used participatory mapping data (Menabe Antimena, Makira) and SIGAP layers to examine conservation coverage and management dynamics; Governance effectiveness was evaluated using scores and narratives from IMET and METT assessments conducted between 2020 and 2023 across over 60 protected areas [

5]; The both provide structured assessments of how well protected areas are being managed. Though the both differ in complexity and scope, they share a common objective: to measure progress, identify gaps, and support adaptive management. The interpretation of score is typically expressed as percentages or cumulative values that reflect how well a site performs across key management criteria (e.g., governance, enforcement, biodiversity monitoring, resource allocation, community participation) : higher scores (e.g., above 75%) indicate strong and consistent management practices across multiple dimensions ; moderate scores (typically 40%–75%) suggest acceptable but uneven performance, often with specific weaknesses (e.g., limited staff capacity or funding), and lower scores (below 40%) signal significant management challenges or institutional weaknesses that may compromise the effectiveness of conservation outcomes. The score is used to perform monitoring activities (regular scoring enables site managers to track improvements or declines over time), strategic planning (results help prioritize actions by identifying thematic or geographic gaps); as a tool for donor reporting and justification (METT and IMET scores are often required by funding agencies, e.g., GEF, FAPBM) as indicators of impact and return on investment, and policy Feedback (aggregated results across multiple sites can inform national or regional conservation strategies, influencing policies and budget allocations). The both tools serve not as audit instruments but as decision-support systems. Their value lies in facilitating structured reflection and guiding evidence-based action at both site and system levels.

Quantitative indicators were constructed around three dimensions: (1) institutional/legal infrastructure, (2) community engagement and coverage, and (3) conservation and enforcement outcomes (e.g., 1,444 VOI, 80,000 logs seized, 30,000+ tortoises confiscated) [

9,

10,

11].

Triangulation was used to cross-validate findings: data from SIGAP were compared with independent reports (e.g., TRAFFIC, FAPBM or field reports from OMC), and legal sources to ensure reliability and identify discrepancies or implementation gaps. In Madagascar, the OMC (Organe Mixte de Conception) is a national and decentralized coordination platform created to improve natural resource governance in Madagascar that brings together a wide range of stakeholders to plan, align, and monitor development and conservation activities at the regional or local level. It typically includes representatives from Local and Regional authorities (communes, regions), Customary leaders, Technical ministries (e.g., Environment, Agriculture), Law enforcement and customs agencies, Judicial authorities (e.g., prosecutors), Civil society organizations, Community-based groups, Development partners, Protected area co-managers, and NGOs. The main roles of the OMC are to ensure coherence between development projects and territorial priorities, facilitate dialogue between actors on the ground, support integrated planning (e.g., land use, natural resource management), and monitor implementation of policies and projects in a participatory manner. The OMC is especially important in areas where environmental conservation, local livelihoods, and land use planning need to be harmonized.

All data used in this study were obtained from publicly available sources or shared by institutional partners under formal collaboration agreements. Sensitive data—such as community-level participatory mapping outputs and enforcement records—were handled in accordance with ethical research principles. When applicable, clearance was obtained from the relevant authorities (e.g., MEDD, regional directorates, FAPBM) prior to dissemination. No personal identifiers were used, and community engagement followed protocols for informed consent. Ethical clearance for field-based components was validated through institutional review procedures, and publication of any sensitive data was authorized by the data providers.

2.1. Case Study Approach

We adopted a country-level case study approach that combined policy analysis, geospatial data interpretation, and stakeholder engagement. The case study focused on Madagascar’s System of Protected Areas (SAPM) and its evolution under current governance reforms. We reviewed national legislation (e.g., Environmental Charter, Law 2015-005 on the Code of Protected Areas or COAP

3 legislation), the CITES implementation framework, and reports from the “Fondation pour les Aires Protégées et la Biodiversité de Madagascar, namely FAPBM[

8].

2.2. Indicators and Data

In addition to analyzing Community-based contracts (VOI) and FAPBM-supported sites, this study incorporates advanced mapping of over 50 critical biodiversity zones identified between 2020 and 2024, along with trafficking seizure data drawn from international reports (cf. [

9,

10,

11]). To evaluate conservation governance, we followed [

12], key indicators were selected across three dimensions: (1) institutional and legal infrastructurecf (cf. [

8,

13,

14,

15,

16]), (2) community engagement and co-management coverage (cf. [

17,

18]), and (3) conservation outcomes and enforcement activity (cf. [

10,

19,

20]). These indicators include: 1,444 active VOI agreements; million hectares under community-based management; using of IMET and METT tools in more than 60 protected areas; 121 recorded international seizures involving Malagasy species (2000–2021); 80,112 intercepted logs of rosewood and ebony (

Dalbergia and

Diospyros spp.); 30,875 radiated tortoises among 34,728 seized herpetofaunal species; over 8,000 geospatial entries in the SIGAP database; and 37 protected areas receiving performance-based funding from FAPBM.

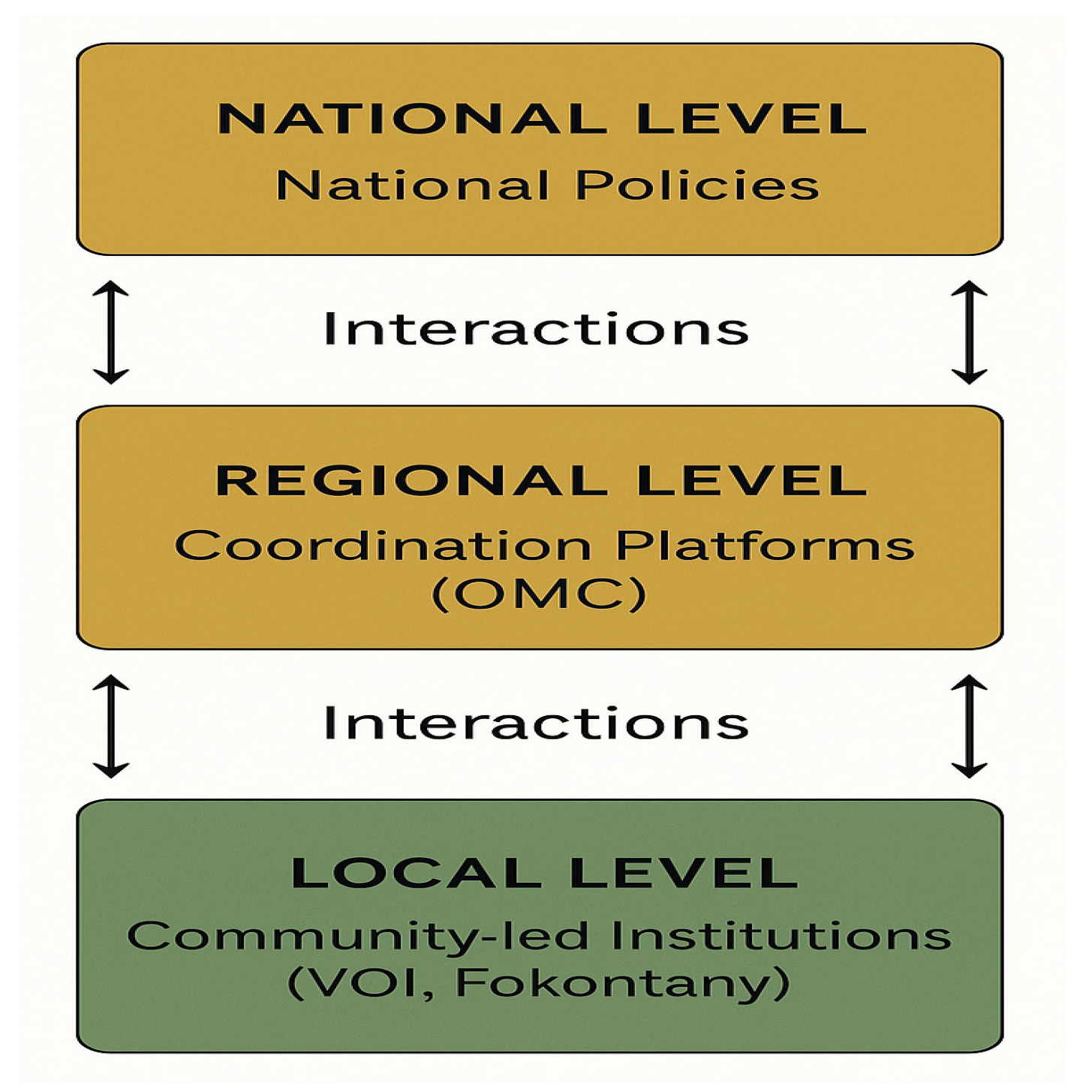

2.2. Analytical Framework

To guide analysis, we employed a multi-level governance framework assessing interactions between national policies, regional coordination platforms (OMC), and community-led institutions (President of VOI or Fokontany). This framework (

Figure 1) helped assess not only institutional coherence but also adaptability to ecological pressures

The evaluation followed a structured procedure using the multi-level governance framework:

Framework Definition: Governance was analyzed across three levels—national, regional, and local—to capture both vertical and horizontal institutional dynamics.

Data Collection: Multiple sources were used, including legal documents, official databases (e.g., SIGAP), IMET/METT assessments, and seizure records (CITES, TRAFFIC

4). Semi-structured interviews and participatory workshops were also conducted with key stakeholders at each level.

Interaction Mapping: Institutional roles, coordination mechanisms, and communication flows between actors were identified and assessed, focusing on how national policies are operationalized at local levels.

Cross-Level Analysis: The framework enabled evaluation of coherence, overlaps, or gaps across governance levels, and identified factors influencing adaptability to ecological threats (e.g., illegal logging, wildlife trafficking).

This integrated procedure allowed a comprehensive understanding of governance performance, institutional effectiveness, and areas needing reform or reinforcement.

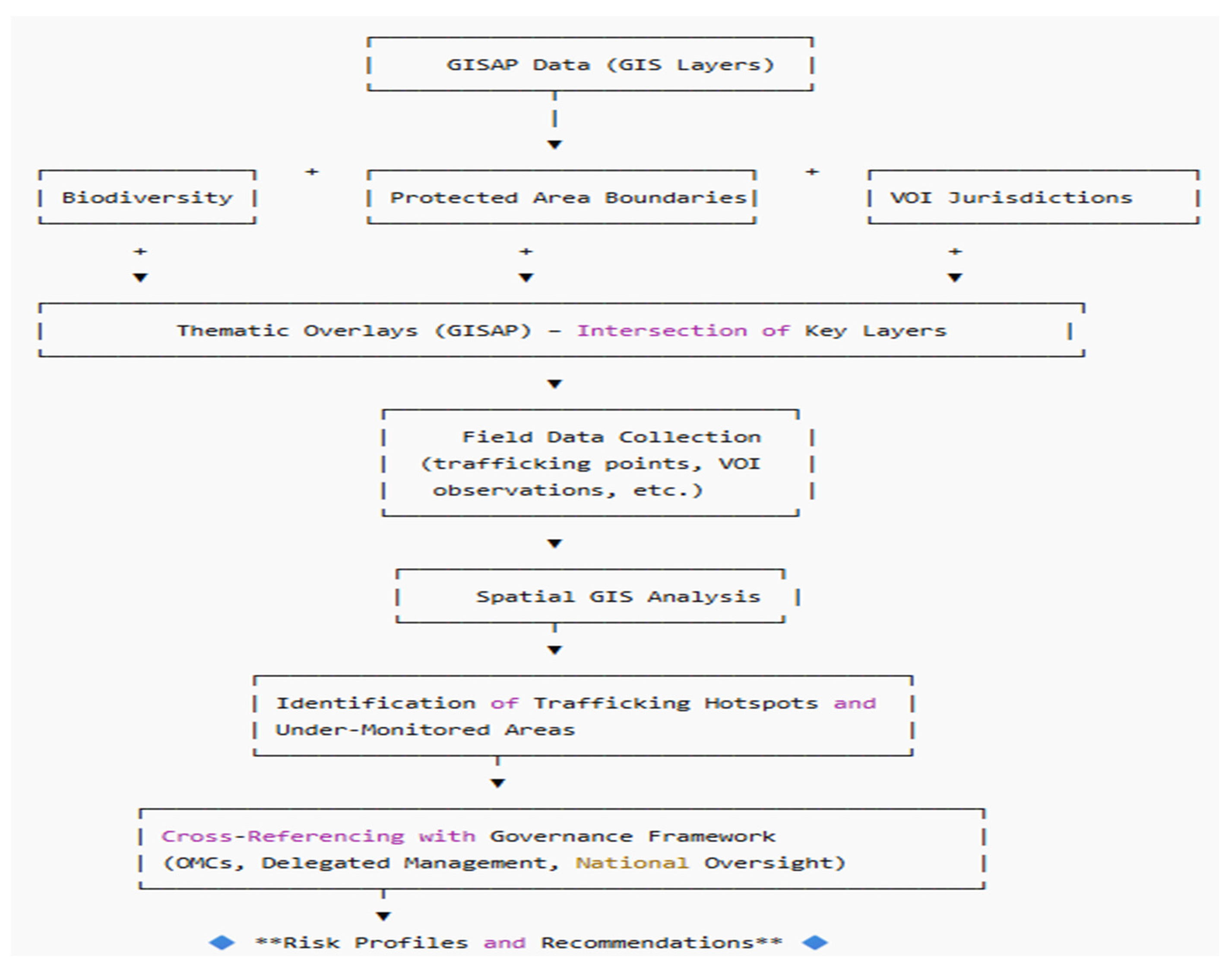

Geospatial analysis was conducted using SIGAP’s GIS layers combined with field-verified shapefiles to identify high-risk trafficking corridors and under-monitored zones (

Figure 2). Thematic overlays included protected area boundaries, VOI jurisdictions, biodiversity density, and reported trafficking events. Mapping outputs were used to generate risk profiles and identify spatial gaps in enforcement and monitoring coverage. We used a multi-level governance framework to analyze the coherence between national and regional enforcement mechanisms, including OMCs and co-management models. GIS methods were used to identify trafficking hotspots and gaps in enforcement according observed and analyzed sources from [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28].

The use of SIGAP (Geospatial Information System for Protected Areas) provides a structured and data-informed approach to analyzing wildlife trafficking risks. The process begins by importing all relevant spatial data layers into the GIS platform. These layers include the official boundaries of protected areas, the jurisdictions managed by community-based organizations (VOIs), biodiversity corridors, and species distribution maps—especially for threatened or key indicator species.

Once these foundational layers are in place, field data is added to enrich the spatial context. This includes GPS coordinates from reported trafficking incidents, as well as qualitative field observations recorded by protected area managers or VOI members. These data points offer crucial on-the-ground insights that complement the static spatial datasets.

Next, thematic overlays are conducted using GIS tools such as QGIS or ArcGIS. By intersecting layers—such as zones of high biodiversity with areas of limited surveillance, or known trafficking locations with zones of weak institutional presence—analysts can visually pinpoint areas of concern. This is followed by density analysis, typically through Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) or heatmaps, to identify wildlife trafficking hotspots and patterns of risk concentration.

To ensure comprehensive coverage, a gap analysis is also conducted. This helps locate under-monitored zones that fall outside the jurisdiction of VOIs or formal patrol routes. Areas that are institutionally “invisible”—so-called “white zones”—are flagged for attention.

The final output of this SIGAP-based process is a series of thematic maps. These maps clearly indicate areas with high trafficking risk, governance or surveillance gaps, and potential biodiversity corridors. The results can then be used to guide targeted management actions, enhance surveillance strategies, and support participatory co-management with local communities.

3. Results

This section presents key findings from spatial analysis, policy review, and institutional performance monitoring. Results are organized by thematic axis: ecological threat mapping, trafficking trends, community management coverage, and institutional capacity and coordination.

3.1. Mapping Critical Threat Zones

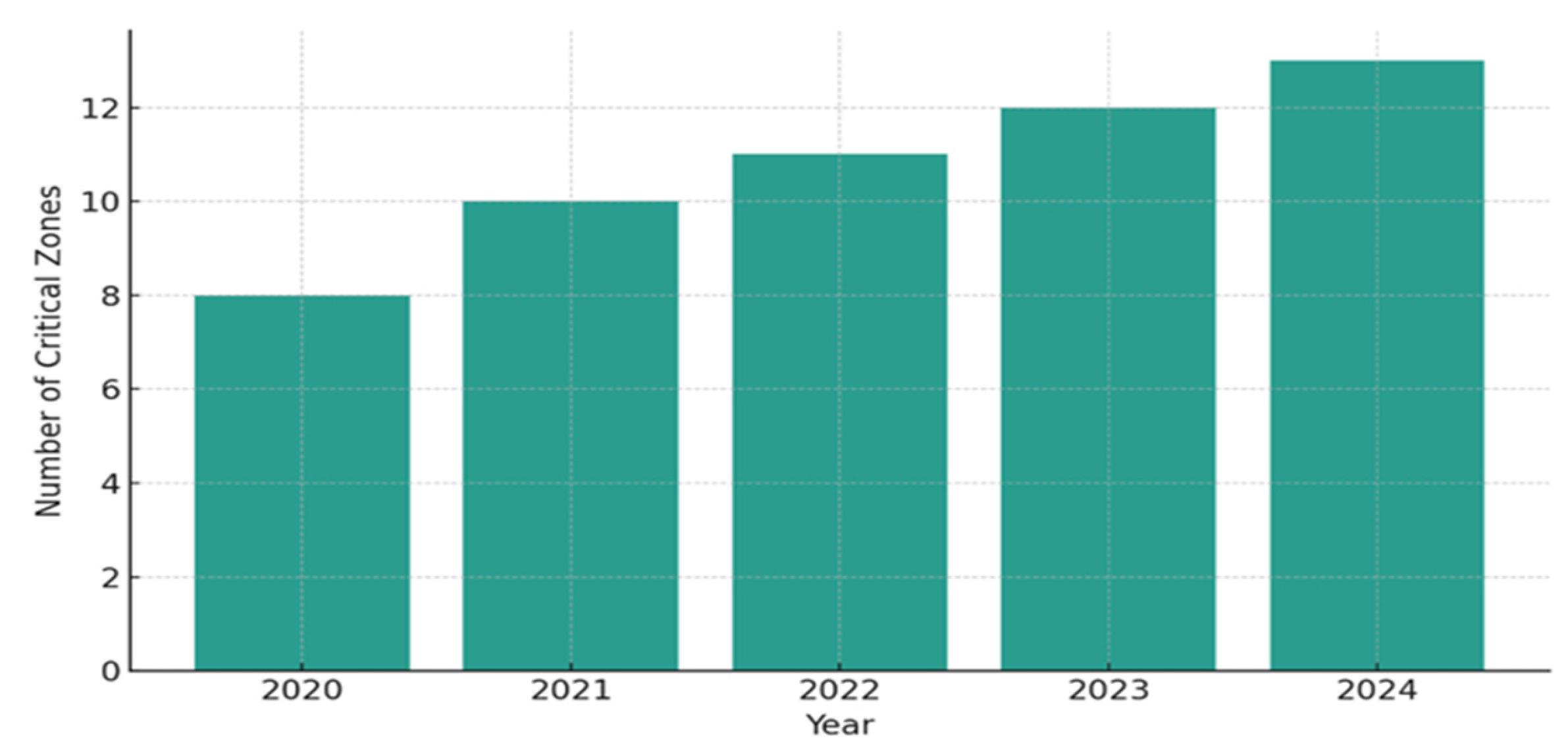

Between 2020 and 2024, advanced spatial analysis conducted by the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MEDD) and its partners identified over 50 critical biodiversity zones under intense anthropogenic pressure. These were identified using satellite imagery, biodiversity indices, land-use change data, and GIS overlays in SIGAP.

The most prominent areas include:

Menabe Antimena, affected by illegal maize farming and timber exploitation;

Makira, a corridor rich in lemur species, impacted by artisanal mining and bushmeat hunting;

Ankarafantsika, hosting threatened tortoise populations exposed to habitat degradation and trafficking.

Figure 3 shows the rising number of critical biodiversity zones identified over the 2020–2024 period. This illustrates both an expansion of detection capacity and a growing spatial spread of threats. The increase highlights the urgency to intervene in these high-risk zones with both conservation action and governance responses. The spatial mapping process has successfully identified priority zones for conservation, confirming that integrating GIS data and biodiversity indicators enhances threat detection and guides strategic interventions.

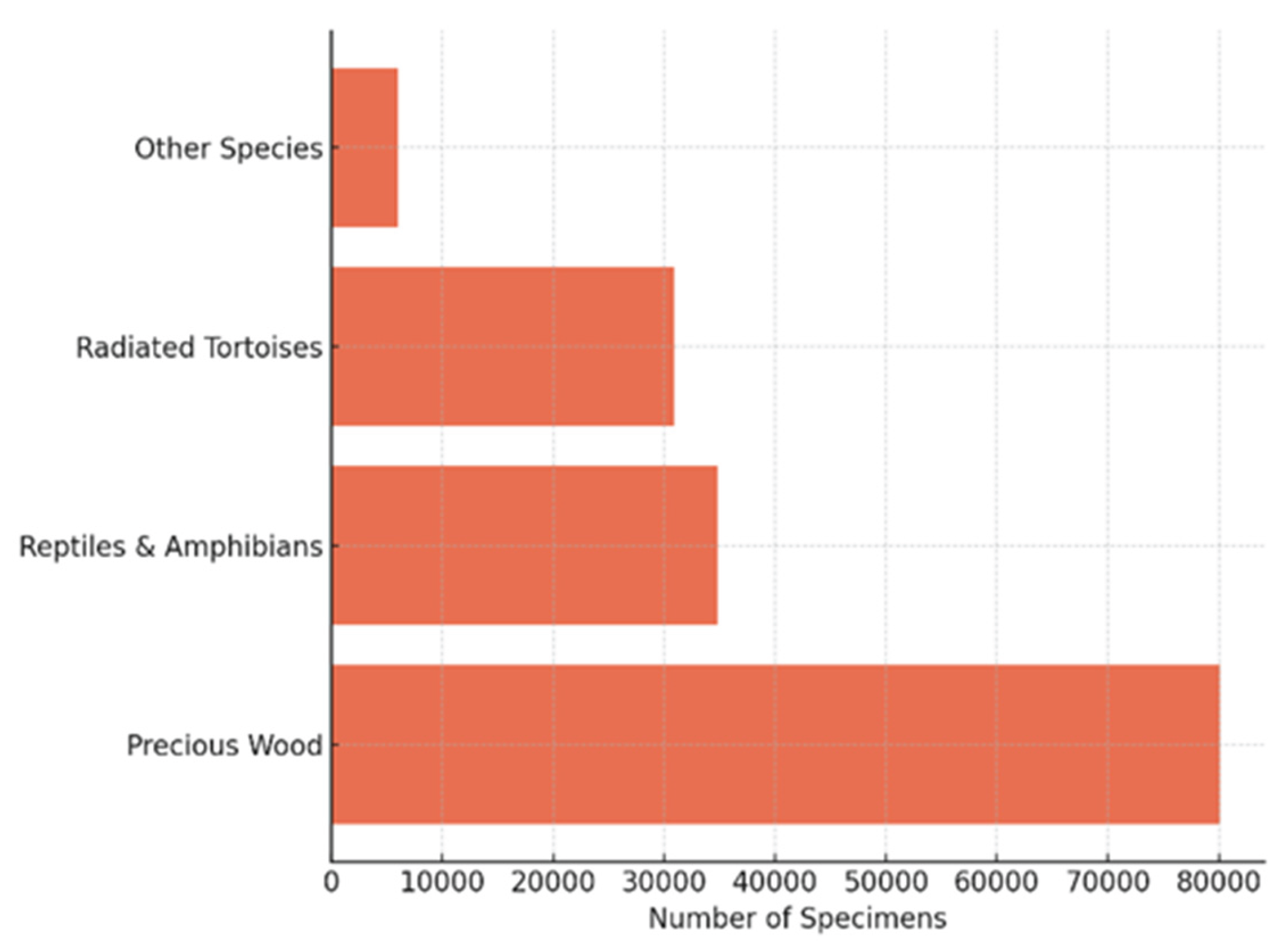

3.2. Trafficking Trends

According to the 2024 interim national strategy, Madagascar was linked to 121 international seizures between 2000 and 2021, underscoring the persistent threat of organized wildlife crime despite legal and policy reforms. These seizures involved approximately 80,112 logs of rosewood and ebony (

Dalbergia and

Diospyros spp.), primarily destined for Asian markets, and 34,728 herpetofaunal species, including 30,875 radiated tortoises (

Astrochelys radiata) from the arid south, as well as thousands of frogs (

Mantella spp.) and Chameleons (

Furcifer spp.) (

Figure 4). The largest recorded operation occurred in May 2024, when 1,117 live animals smuggled from Madagascar were intercepted in Thailand. The report notes sharp increases in seizure events following periods of political instability, notably post-2009 and again between 2021 and 2023, exacerbated by enforcement disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic.

These statistics above confirm the persistence of organized wildlife crime despite legal efforts.

Socioeconomic factors are equally significant: over 70% of rural Malagasy households depend on natural resources. Without alternative livelihoods, communities may participate—knowingly or unknowingly—in illegal wildlife trade. Conservation strategies must therefore address economic vulnerability and incorporate customary knowledge.

Table 1 illustrates historical export volumes of selected Malagasy species that were legally traded under CITES regulations between the 1990s and early 2000s. This legal trade, though regulated, reached substantial volumes and may have created precedents or pathways for overexploitation, especially where enforcement and monitoring capacity was limited.

The high historical export volumes for species such as Mantella frogs and chameleons illustrate sustained pressure, even under regulated systems. Though legal, such trade often paved the way for unsustainable practices or laundering mechanisms.

Wildlife trafficking persists as a multifaceted issue, driven by external demand, internal vulnerabilities, and governance fragility. Addressing it requires coordinated law enforcement, socioeconomic support for rural communities, and adaptive conservation policies.

3.3. Institutional and Monitoring Capacity

The capacity-building and institutional tools have significantly expanded in recent years:

More than 60 protected areas across Madagascar now apply IMET and METT frameworks to monitor and improve management effectiveness.

The SIGAP geospatial platform, which includes over 8,000 mapped entries, plays a crucial role in supporting zonation, tracking ecological pressures, and targeting investments.

In parallel, the FAPBM provides performance-based funding to 37 protected areas, linking financial support to measurable conservation outcomes.

Coordination has also improved through MEDD-led inter-ministerial committees, which align national and regional strategies with the participation of judiciary bodies, customs authorities, and local stakeholders, reinforcing governance coherence and institutional accountability.

4. Discussion

Madagascar’s environmental governance reforms reflect a productive convergence between technological innovation and traditional governance systems. Through structures like the Operational Monitoring Committees (OMCs) and the Regional Committees for the Orientation and Regulation of Forest and Agricultural Development (CRORFAD

6), decentralization has enabled more localized and responsive enforcement mechanisms [

29,

30]. The integration of tools such as the Geospatial Information System for Protected Areas (SIGAP) has enhanced transparency, improved spatial planning, and facilitated the formal recognition of customary land rights [

31,

32]. These institutional advances—driven by the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development (MEDD)—have strengthened coordination and responsiveness at the regional level, better aligning conservation efforts with local land-use dynamics and socio-cultural realities.

Nevertheless, persistent challenges remain, notably in terms of uneven institutional capacity, weak enforcement, overlapping mandates, and insufficient, unstable funding across regions [

33,

34]. The MEDD’s approach demonstrates that geospatial innovation combined with inclusive governance frameworks can help resist biodiversity erosion and support community resilience. A just and resilient policy framework requires sustained institutional strengthening, empowered community-based organizations (VOIs), culturally grounded policies, transparent funding allocation, and robust anti-corruption measures [

35]. GIS-based platforms like SIGAP have not only improved spatial planning and stakeholder communication but also promoted evidence-based decision-making and the integration of traditional ecological knowledge through participatory mapping [

36,

37].

Despite notable progress, the sustainability of conservation outcomes remains at risk unless a more coherent national coordination framework is implemented, accountability mechanisms are reinforced, and long-term capacity-building efforts for local actors are scaled up. Addressing these structural weaknesses is crucial to consolidate recent achievements and to foster long-term ecological and social resilience. Future research could further explore how these governance innovations influence livelihoods, and how adaptive management approaches can better integrate climate adaptation needs into conservation strategies.

5. Conclusions

This case study demonstrates that the integration of geospatial innovation, participatory governance, and institutional reform can significantly enhance biodiversity conservation in contexts of limited enforcement capacity. Madagascar’s response to escalating wildlife trafficking—through local empowerment, performance-based monitoring, and multi-level governance coordination—offers important lessons for other biodiversity-rich countries facing similar pressures.

Despite structural limitations such as funding constraints, enforcement fragmentation, and political volatility, Madagascar’s approach illustrates that progress is possible when policy reform is paired with community ownership and transparent data systems. Protected areas managed by VOIs show greater resilience to illegal extraction when supported by inclusive platforms like OMCs and digital monitoring tools like SIGAP.

Looking forward, further institutional strengthening, regional cooperation (particularly across the western Indian Ocean), and long-term investment in local conservation economies are critical to ensuring the sustainability of these gains. The Madagascar experience reinforces the idea that biodiversity protection is inseparable from social justice and territorial sovereignty.

Madagascar’s strategy offers lessons for other biodiversity-rich yet vulnerable countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software, formal analysis, investigation, resources, writing—original draft preparation, and funding acquisition : S.R.; validation, writing—review and editing, visualization, and supervision : N.H.C.R.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting to this study are accessible through SIGAP, MEDD archives, and the Interim national trafficking strategy.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the MEDD, FAPBM, SIGAP team, regional task forces, and all VOI representatives.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| VOI |

Vondron’Olona Ifotiny (Community-based management) |

| CITES |

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora |

| GDP |

Growth development |

| SAPM |

Systèmes des Aires Protégées de Madagascar |

| NGO |

Non-gouvernemental Organisation |

| SIGAP |

Système d’Information pour la Gestion des Aires Protégées |

| IMET |

Integrative Management Effectiveness Tool |

| METT |

Management Effectiveness Tracking Tool |

| COBA |

Communauté de base |

| COAP |

Codes de gestion des Aires protégées |

| FAPBM |

Fondation pour les Aires Protégées et de la Biodiversité de Madagascar |

| OMC |

Organe Mixte de Conception |

| GIS |

Global Information System |

| SMART |

Spatial monitorting and Reporting tool |

| CRORFAD |

Comité Régional d’Orientation et de Régulation des Forêts et du Développement Agricole |

References

- Goodman, S. M.; Benstead, J. P. The Natural History of Madagascar. Goodman, S. M.; Benstead, J. P., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago and London, 2003; 1709 pp. ISBN 0-226-3036-3.

- Réseau des Aires Protégées de Madagascar (REAP). Base de données SIGAP sur les Aires Protégées et VOI. Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable : Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2023 ; 65 pp.

- World Bank. Madagascar Country Economic Memorandum: Charting a New Course for Growth. World Bank Group : Washington, DC ; World Bank : Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2020.

- République de Madagascar. Création du Système des Aires Protégées de Madagascar (SAPM) ; Décret n°2005-848 ; 2005.

- MEDD ; UNDP. Bilan des outils numériques de gouvernance environnementale à Madagascar : SIGAP, IMET, et eCDS; Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable: Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2022.

- MEDD. Stratégie Nationale de Lutte contre le Trafic des Espèces Sauvages. Rapport intérimaire. Ministère de l’Environnement et du développement Durable : Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2024.

- IPSI Secretariat. Guidelines for the Satoyama Initiative and Socio-Ecological Production Landscapes. Annual Report 2023. In Satoyama Initiative; United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability (UNU-IAS): Tokyo, Japan, 2024; 32 pp.; Http://Satoyama-Initiative.Org.

- Fondation pour les Aires Protégées et la Biodiversité de Madagascar (FAPBM). Rapport Annuel 2022–2023; FAPBM: Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2023; 83 pp. https://www.fapbm.org/rapport_annuel/rapport-annuel-2023/.

- Chng, S.C.L.; Ratsimbazafy, C.; Rajeriarison, A.; Rejado, S.; Newton. An Assessment of Wildlife Trade between Madagascar and Southeast Asia. Traffic Report. Traffic International: Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2023; 33 pp.

- UNODC; WWC. Trafficking in Protected Species. WWC Report 2024. United Nations Publications; World Wildlife Crime: Vienna, 2024; 241 pp. ISSN: 2521-6155.

- Conservation International; Biotope; Missouri Botanical Garden; Asity Madagascar. Madagascar and the Indian Ocean Islands: Biodiversity Hotspot: Ecosystem Profile. Vieille, M.; Andriambololonera, S.; Manjato, N. et al., Eds. The CEPF 2022 Update. Conservation International. Arlington, Washington, USA, 2022; 330 pp. Www.Cepf.Net.

- Coad, L.; Leverington, F.; Knights, K.; Geldmann, J.; et al. Measuring Impact of Protected Area Management Interventions: Current and Future Use of the Global Database of Protected Area Management Effectiveness. The Royal Society Publishing. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370: 20140281. Pp. 1-10. 2014. Htpp://dx.doi.Org/10.1098/Rstb.2014.028.

- Républiqque de Madagscar. Mise en œuvre du Programme Environnemental Phase III de Madagascar. Rapport Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable: Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2022.

- Paolini, C. ; Rakotobe, D. Malette pédagogique pour l’outil intégré sur l’efficacité de gestion : guide pour évaluer et améliorer l’efficacité de gestion des Aires Protégées. IUCN and BIOPAMA. Gland, Suisse, 2022; pp. 1-65. ISBN: 978-2-8317-2194-1 (PDF). Fr. [CrossRef]

- Hocking, M.; Stolton, S.; Leverington, F.; Dudley, N.; Courrau, J. Evaluating Effectiveness: A Framework for Assessing Management Effectiveness of Protected Areas. 2nd Edition. Best Practice Protected Area; Guidelines Series (14). IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK; World Commission on Protected Area Guidelines; 2006. Xiv + 105 Pp. ISBN-10: 2-8317-0939-3 ; ISBN-13: 978-2-8317-0939-0.

- Stolton, S.; Dudley. METT Handbook: A Guide to Using the Management Effectiveness Tracking Tool (METT). WWF-UK, Woking. United Kingdom, 2016. 1- 74 pp. ISBN 978-1-5272-0060-9.

- REBIOMA ; MEDD. Base de données SIGAP – Système d’Information pour la Gestion des Aires Protégées, 2023. Antananarivo, Madagascar.

- MEDD. État des lieux de la gouvernance communautaire des ressources naturelles à Madagascar. Rapport interne. Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable. 2020.Antananarivo, Madagascar.

- CITES Secretariat. World Wildlife Trade Report 2022: Madagascar Seizures 2000-2001: 2022.

- UNEP-WCMC. Analysis of Dalbergia and Diospyros Trade under CITES. 2022.

- Turtle Survival. Radiated Tortoise Trafficking and Seizures; Turtle Survival Alliance: 2023; 54 pp.

- UNODC. World Wildlife Crime: Trafficking in protected species; World Wildlife Crime; UNODC: 2020.

- Mongabay Series and EAGLE Network Reports.

- DeFries, R.; Hansen, A.; Newton, A.C.; Hansen, M.C. Increasing Isolation of Protected Areas in Tropical Forests over the Past Twenty Years. Ecol. Appl., 2005 ,15 (1), 19–26. [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.; Sanjavan, M. A. Global Review of Biodiversity Loss and Its Spatial Drivers. Science, 2006, 373 (5790), 790–793.

- Coad, L.; Burgess, N.D.; Fish, L.; et al. Measuring Impact of Protected Area Management Interventions on Poaching: Methods and Results in African Sites. Plos ONE, 2015, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J.C. Democratic Decentralization of Natural Resources. In Beyond Structural Adjustment The Institutional Context of African Development; Van De Walle, N., Ball, N., Ramachandran, V., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, 2003; pp. 159–182. ISBN 978-1-4039-8128-8.

- Leach, M.; Mearns, R.; Scoons, I. Environmental Entitlements: Dynamics and Institutions in Community-Based Natural Resource Management. World Dev. 1999, 27, 225–247. [CrossRef]

- Andriamalala, G.; Gardner, C.J. L’émergence Des Transferts de Gestion Communautaire Des Ressources Naturelles à Madagascar: Enjeux et Perspectives. Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2010, 5, 95–99. [CrossRef]

- Poudyal, M.; Ramamonjisoa, B.S.; Hockley, N. et al. Can REDD+ Social Safeguards Reach the ‘Right’People? Lessons from Madagascar. Glob. Environ. Change 2016, 37, 31–42. [CrossRef]

- Kull, C.A.; Tassin, J.; Rangan, H.; Dafour-Dror, J.M. The Introduced Flora of Madagascar. Biol. Invasions 2015, 17, 357–396. [CrossRef]

- MEDD. Rapport Sur La Mise En Œuvre Des Outils Géospatiaux Pour La Gestion Des Aires Protégées à Madagascar; Ministère de l’Environnement et du Développement Durable: Antananarivo, Madagascar, 2023.

- Corson, C. From Rhetoric to Practice: How High-Profile Politics Impeded Community Consultation in Madagascar’s New Protected Areas. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2012, 25, 336–351. [CrossRef]

- Raik, D.B.; Decker, D.J. A Multisector Framework for Assessing Community-Based Forest Management: Lessons from Madagascar. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 14. [CrossRef]

- Bertrand, A.; Rasolohery, A.; Rabenandrasana, J. Strengthening Environmental Governance through Local Empowerment: Lessons from Madagascar. Environ. Policy Gov. 2023, 33, 55–68. [CrossRef]

- Urech, Z.L.; Sorg, J.P.; Felber, H.R. Challenges for Community-Based Forest Management in Madagascar: The Case of the Menabe Region. Environ. Dev. 2013, 6, 113–127. [CrossRef]

- Scales, I. The Future of Conservation and Development in Madagascar: Time for a New Paradigm? Madag. Conserv. Dev. 2014, 9, 5–12. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

The SAPM (Protected Areas System of Madagascar) is the national network of protected areas officially recognized by the Malagasy government. It was established to conserve Madagascar’s exceptional biodiversity and ensure the sustainable use of its natural resources. The SAPM includes various types of protected areas managed by public institutions, private organizations, and local communities. It goes beyond the historical network managed by Madagascar National Parks (MNP) to include new conservation sites under collaborative and decentralized governance. The system aims to represent all of Madagascar’s unique ecosystems, safeguard endangered species, and support local development through conservation. |

| 2 |

The Malagasy Foundation for Protected Areas and Biodiversity (FAPBM) is a national environmental trust fund created in 2005. Its mission is to ensure the sustainable financing of Madagascar’s protected areas and biodiversity conservation efforts. FAPBM provides long-term financial support to protected areas across the country, helping with their management, community development around conservation sites, and ecological monitoring. It works in partnership with the Malagasy government, international donors, NGOs, and local communities to strengthen biodiversity protection and promote sustainable livelihoods. |

| 3 |

The Code of Protected Areas of Madagascar (COAP) is the legal framework that governs the creation, classification, and management of protected areas in the country. It was adopted in 2001 and revised in 2015 to better reflect national and international conservation standards. It defines different types of protected areas (strict nature reserves, national parks, community-managed areas, etc.) and sets out the rules for access, permitted activities, and governance. It emphasizes participatory management, allowing communities, NGOs, and the private sector to be involved in conservation efforts.

The COAP is essential for biodiversity protection, sustainable development, and the fight against environmental crimes such as illegal logging and wildlife trafficking.

|

| 4 |

TRAFFIC is a leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants, aiming to ensure that wildlife trade is not a threat to the conservation of nature. |

| 5 |

SMART (Spatial Monitoring and Reporting Tool): it is an open-source software platform used by conservation managers and rangers to collect, manage, and analyze data from patrols, enabling more effective and adaptive management of protected areas. |

| 6 |

CRORFAD (Regional Committee for the Orientation and Regulation of Forest and Agricultural Development) is a regional participatory governance structure established in Madagascar. It aims to coordinate actions related to forest management and agricultural development at the regional level while aligning local and national priorities. The committee brings together various stakeholders, including government representatives, local authorities, community organizations, and actors from the private sector and civil society. It facilitates integrated land-use planning, monitoring of conservation initiatives, and harmonization of land-use practices. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).