1. Introduction

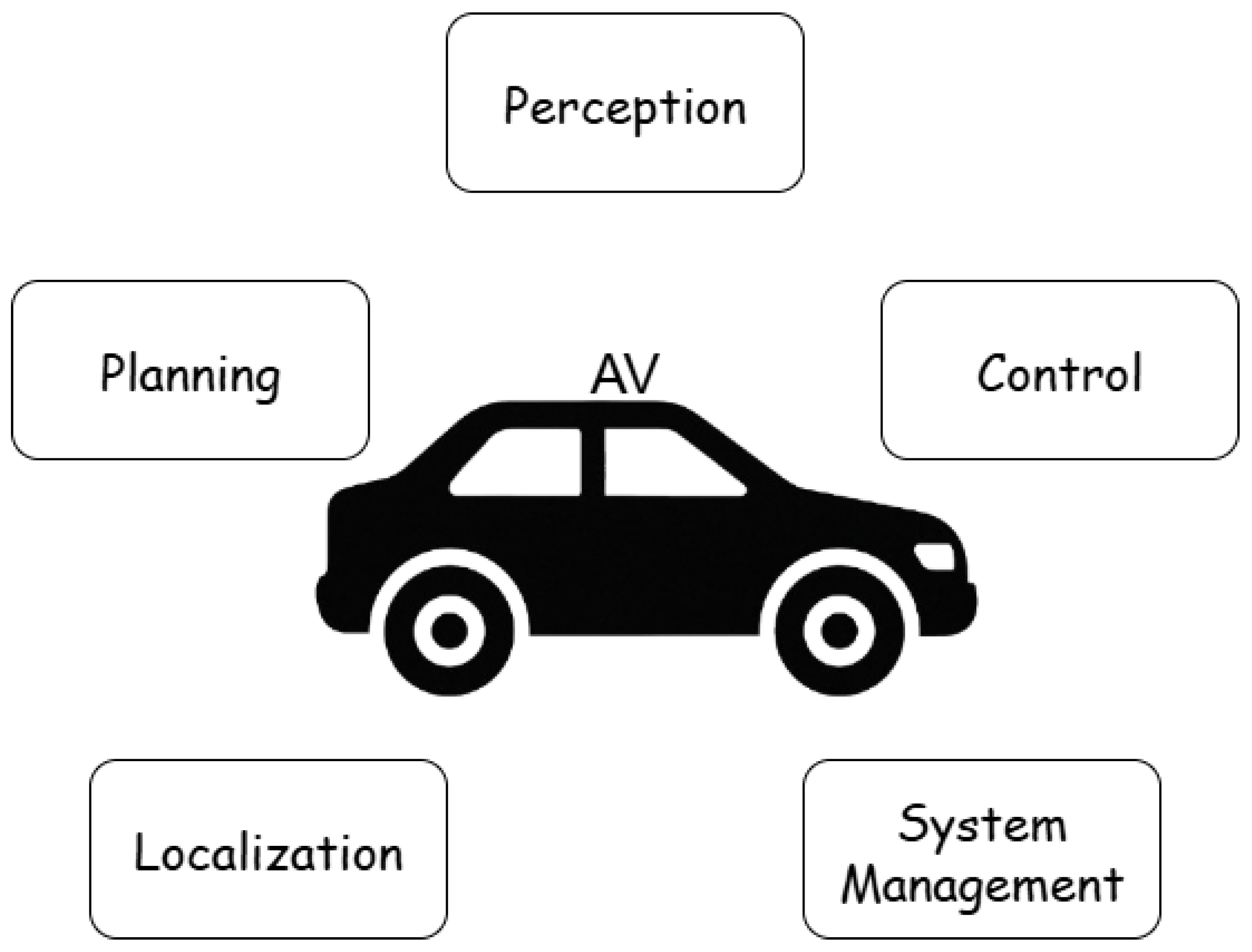

In recent years, autonomous driving has evolved into a complex and rapidly progressing research area. As an inherently multidisciplinary challenge, it brings together elements of robotics, computer vision, control theory, embedded systems, and artificial intelligence. While many architectural decompositions are possible, for clarity, we distinguish five core functional domains in autonomous vehicles: perception, localization, planning, control, and system-level management (see

Figure 1). These components do not operate in isolation — they are highly interdependent and must be tightly integrated to achieve safe and reliable autonomous behavior. For instance, accurate localization relies on perception, planning depends on both localization and perception, and control must faithfully execute decisions made by the planning module. This functional breakdown serves as a foundation for understanding where and how RL and IL techniques can be effectively applied .

In the following subsection, we briefly review each of these five domains to provide context for the role of learning-based methods in autonomous driving.

Perception refers to the set of capabilities that allow an autonomous vehicle to interpret its surroundings based on raw sensor data. It typically involves processing inputs from cameras, LiDAR, radar, and ultrasonic sensors to detect and classify objects, recognize lanes and traffic signals, and estimate environmental conditions such as lighting and weather. The output of the perception module provides a structured, machine-readable representation of the environment, serving as a critical input for localization, planning, and decision-making components. Robust perception must operate in real time and remain reliable under diverse and challenging conditions, including occlusions, sensor noise, and adverse weather.

Localization enables an autonomous vehicle to estimate its precise position and orientation within a known or partially known environment. It typically combines data from GPS, inertial measurement unit, LiDAR, and cameras using techniques such as simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) or map-matching algorithms. Accurate localization is essential for safe navigation, as it allows the vehicle to interpret its surroundings relative to static maps and dynamic objects. Robust performance is required even in GPS-denied environments, under sensor drift, or when landmarks are temporarily occluded.

Planning is responsible for determining the vehicle’s future actions to navigate safely and efficiently toward its destination. It operates on two levels: behavior planning, which selects high-level maneuvers (e.g., lane changes, yielding), and motion planning, which generates detailed, dynamically feasible trajectories. Planning relies on inputs from perception and localization to avoid obstacles, follow traffic rules, and ensure passenger comfort. It must operate in real time and adapt continuously to changing environments.

Control translates planned trajectories into low-level commands that drive the vehicle’s actuators, such as steering, throttle, and brake. Its goal is to follow the desired path accurately while maintaining stability, comfort, and responsiveness. Common approaches include PID controllers, model predictive control (MPC), and learning-based policies. The control must operate at high frequency and remain robust to disturbances, delays, and variations in vehicle dynamics.

System management oversees the coordination, reliability, and safety of all modules within the autonomous driving stack. It handles task scheduling, resource allocation, health monitoring, fault detection, and interprocess communication. This layer ensures that all components operate cohesively under real-time constraints and provides fallback strategies in case of failures, making it critical for reliable production-grade autonomy.

This work focuses primarily on the planning and control components of autonomous driving, where RL and IL have demonstrated the greatest practical relevance. In these domains, learning-based agents are trained to make tactical decisions and execute low-level maneuvers based on sensor-derived representations of the environment. Approaches vary from end-to-end policies that directly map observations to actions, to modular designs where planning and control are learned separately. In contrast, components such as perception and localization are typically treated as fixed inputs—often provided by the simulator in the form of semantic maps, LiDAR projections, or ground-truth poses—and are not the target of learning. Similarly, system-level management is generally handled using conventional software architectures and falls outside the scope of learning.

Figure 1.

Functional Components of Autonomous Driving.

Figure 1.

Functional Components of Autonomous Driving.

Among the range of machine learning techniques applied in this domain, reinforcement learning (RL) -exemplified by algorithms such as Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) and Deep Q Networks (DQN) - has emerged as one of the most promising approaches [

1]. Consequently, the field of RL continues to advance at a remarkable pace, with increasingly sophisticated methods producing superior performance across a growing spectrum of applications [

2,

3].

This review focuses on RL and IL strategies implemented in the CARLA simulation platform. CARLA is uniquely suited to this task due to its open-source nature, full-stack simulation capabilities, and strong support for AI integration, making it one of the most widely used platforms for academic research on learning-based AV agents.. CARLA is a widely adopted high-fidelity simulator for autonomous driving research that offers extensive support for sensor realism, weather variability, and urban driving scenarios [

4,

5]. Reviewing the state-of-the-art literature helps identify prevailing agent architectures, design decisions, and gaps that may inform the development of improved driving agents.

The technical analysis in this paper is grounded in representative RL-based studies [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. For each work, we extract the definitions of the agent’s state and action spaces and examine the structure and effectiveness of the associated reward function. The studies, though diverse in their technical formulations, share a common foundation: the use of DRL in the CARLA environment for autonomous navigation and control. We synthesize the insights from these papers to compare strategies, identify trade-offs, and understand how varying model architectures impact policy learning and performance.

Additionally, three studies [

12,

13,

14] present IL–based approaches that do not rely on environmental rewards but instead learn behaviors by mimicking expert demonstrations. These IL methods are assessed in parallel to the RL models to identify complementary strengths and limitations. Their inclusion is critical, as IL is increasingly integrated with RL to enhance learning efficiency, policy generalization, and safety, especially in data-constrained or high-risk environments [

15,

16].

Beyond these core studies, recent research has pushed the boundaries of RL in autonomous driving further. For example, Sakhai and Wielgosz proposed an end-to-end escape framework for complex urban settings using RL [

41], while Kołomański et al. extended the paradigm to pursuit-based driving, emphasizing policy adaptability in adversarial contexts [

42]. Furthermore, Sakhai et al. explored biologically inspired neural models for real-time pedestrian detection using spiking neural networks and dynamic vision sensors in simulated adverse weather conditions [

43]. Recent studies have also explored the robustness of AV sensor systems against cyber threats. Notably, Sakhai et al. conducted a comprehensive evaluation of RGB cameras and Dynamic Vision Sensors (DVS) within the CARLA simulator, demonstrating that DVS exhibit enhanced resilience to various cyberattack vectors compared to traditional RGB sensors [

62]. These contributions showcase the evolving versatility of RL architectures and their capacity to address safety-critical tasks under uncertainty.

Despite the rapid progress in learning-based autonomous driving, existing systems face several persistent challenges. Studies have shown that end-to-end RL agents often suffer from significant performance degradation—up to 35%—when deployed in conditions that differ from their training environments, such as novel towns or adverse weather [

57]. Similarly, Imitation Learning (IL) agents trained solely on expert demonstrations have demonstrated up to 40% higher collision rates when exposed to previously unseen driving contexts [

58]. Moreover, a key difficulty in RL lies in the careful tuning of reward functions; poorly calibrated rewards have been linked to over 20% of policy failures in simulation settings [

59,

60]. Finally, RL agents often overfit to narrow task domains, with generalization failures reaching up to 60% when encountering dynamic obstacles not seen during training [

61]. These limitations underscore the need for more robust, transferable, and sample-efficient learning frameworks that integrate the strengths of both RL and IL paradigms.

In general, this review aims to provide a comprehensive synthesis of RL and IL research in the CARLA simulator, highlighting how these learning paradigms contribute to the development of intelligent autonomous driving systems. Compared to widely cited reviews such as [

55] and [

56], our work provides a more detailed and structured analysis of reinforcement learning methods specifically in the context of autonomous driving control within simulation environments. While previous surveys focus largely on algorithmic taxonomies or general architectural roles, we examine RL approaches through a set of concrete implementation descriptors: state representation, action space, and reward design. This framing enables direct comparison of control strategies and learning objectives across studies, which is largely missing from earlier work. We also include visual summaries of reward functions and highlight differences in how these functions guide policy learning. Furthermore, our focus on the CARLA simulator as a common experimental platform allows for a more consistent and grounded discussion of evaluation strategies and training setups, bridging the gap between theory and practical deployment.

2. Reinforcement Learning in Autonomous Driving

2.1. Overview of Reinforcement Learning

Reinforcement learning (RL) is a cornerstone of modern machine learning, particularly as deep learning has expanded its applicability to complex, real-world problems

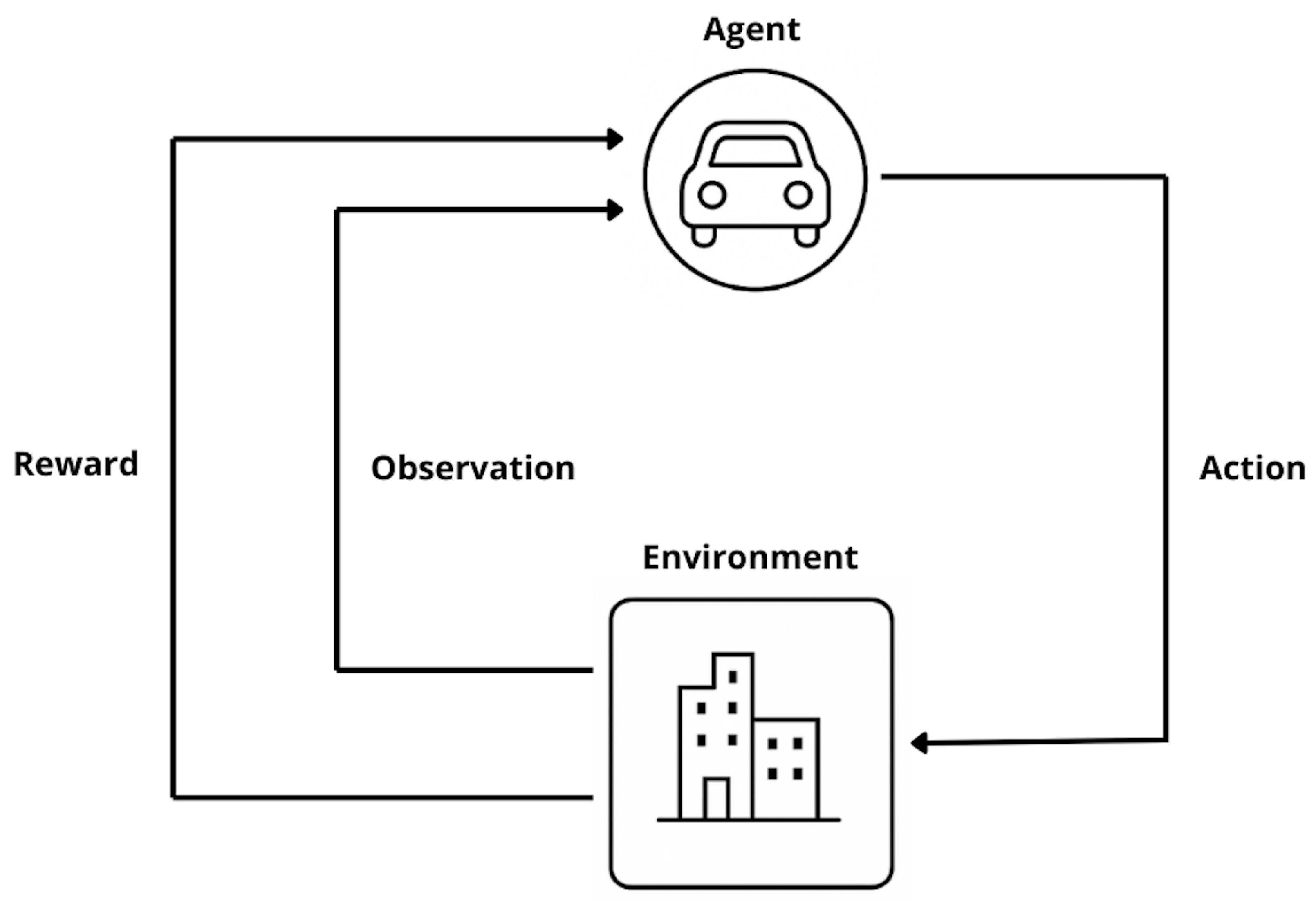

[17]. In the RL paradigm, an agent interacts with its environment by performing actions and receiving feedback in the form of rewards, which guide its future behavior

[18,19,20]. This closed-loop interaction between agent and environment lies at the heart of autonomous decision-making systems.

During training, the agent uses a policy to select actions, while the environment responds by returning a new observation and a scalar reward that reflects the value of the action taken

[21]. The reward function is pivotal—it defines the learning objective and directly influences the agent’s trajectory through the learning space

[23,24]. A schematic of this interaction is shown in

Figure 1, where the feedback loop is emphasized.

A key strength of RL lies in its emphasis on long-term cumulative reward optimization

[25]. Instead of maximizing immediate payoff, the agent learns policies that favor long-term outcomes, often sacrificing short-term gain for strategic advantages. Each learning episode starts in an initial state and ends upon reaching a terminal condition

[26], making RL particularly suitable for sequential decision-making tasks such as autonomous driving.

In this framework, the

agent serves as the autonomous controller, making decisions from within a predefined

action space [27]. These actions may be discrete (e.g., lane switch) or continuous (e.g., steering angle adjustment)

[28,29]. A

state encodes relevant environmental information at a given moment, and the complete collection of possible states defines the

state space [30]. The action space defines all possible maneuvers the agent can execute

[31].

A crucial function in this setup is the

reward function, which provides evaluative feedback for the agent’s choices. This scalar signal not only reinforces beneficial actions but also penalizes poor decisions, shaping the agent’s future policy

[23,24]. The

policy maps states to probabilities over actions, and the agent’s objective is to approximate or discover an

optimal policy that maximizes expected cumulative rewards across episodes

[22].

RL is distinct from supervised and unsupervised learning, the other two main branches of machine learning

[32]. While supervised learning relies on labeled data and unsupervised learning discovers structure from unlabeled data, RL learns directly through real-time interaction. The episodic nature of RL generates diverse, temporally rich training samples that improve generalization and robustness in dynamic settings.

Reinforcement learning methodologies are commonly categorized into the following types:

Model-based vs. Model-free: Model-based methods construct a predictive model of environment dynamics to plan actions. Model-free methods, in contrast, learn policies or value functions directly from experience

[22,33,34].

Policy-based vs. Value-based: Policy-based methods directly learn the policy function, often using gradient methods. Value-based methods estimate action values and derive policies by selecting actions with the highest value

[22,35].

On-policy vs. Off-policy: On-policy methods optimize the same policy used to generate data, ensuring data-policy alignment. Off-policy methods allow learning from historical or exploratory policies, improving sample efficiency

[22,36,37].

Recent studies have explored diverse reinforcement learning approaches in autonomous driving. For instance, Toromanoff et al. (2020) presented a model-free RL strategy leveraging implicit affordances for urban driving [

76]. Wang et al. (2021) introduced the InterFuser, a sensor-fusion transformer-based architecture enhancing the safety and interpretability of RL agents [

77]. Additionally, Chen et al. (2021) developed cooperative multi-vehicle RL agents for complex urban scenarios in CARLA, highlighting significant improvements in collaborative navigation [

78].

Prominent examples that embody these categories include Q-learning, REINFORCE, Actor-Critic algorithms, Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), Deep Q-Networks (DQN)

[38,39] and Model Predictive Control (MPC)

[47,48].

Table 1 summarizes the key characteristics of some of the most popular reinforcement learning methods, classifying them based on their use of models, policy/value orientation, and policy type.

2.2. CARLA Simulator as an Evaluation Platform

CARLA (Car Learning to Act)

[5] is an open-source, high-fidelity driving simulator developed to support research in autonomous vehicles and intelligent transportation systems. Its detailed urban environments, physics engine, and API flexibility make it a preferred tool for training and evaluating RL agents in realistic conditions

[40].

Key features of CARLA include:

Management and control of both vehicles and pedestrians.

Environment customization (e.g., weather, lighting, time of day).

Integration of diverse sensors such as LiDAR, radar, GPS, and RGB cameras.

Python/C++ APIs for interaction and simulation control.

These capabilities support deterministic and repeatable scenarios, essential for reproducible experimentation in RL-based driving. CARLA’s integration with RL frameworks has facilitated breakthroughs in tasks ranging from basic lane following to dynamic obstacle avoidance and multi-agent coordination. While commercial tools like CarSim offer high-fidelity physics models suitable for vehicle dynamics and control prototyping, they are less suited for the end-to-end training of autonomous agents using RL or imitation learning (IL). CARLA, on the other hand, provides native APIs, multi-modal sensor integration, and supports adversarial and interactive driving scenarios crucial for benchmarking learning-based policies.

Benchmarking the performance and robustness of RL algorithms has been significantly streamlined by CARLA. Zeng et al. (2024) provided a comprehensive benchmarking study, assessing autonomous driving systems in dynamic simulated traffic conditions [

81]. Similarly, Jiang et al. (2025) analyzed various RL algorithms in CARLA, focusing on their stability, robustness, and performance consistency across multiple driving tasks [

87]

Moreover, CARLA distinguishes itself from other traffic simulators by virtue of its expansive, collaborative community—which continually shares improvements, assets, and best practices—and its exceptionally flexible architecture. This elasticity enables the rapid creation and deployment of a wide array of simulation scenarios, ranging from complex urban intersections to varied environmental conditions.

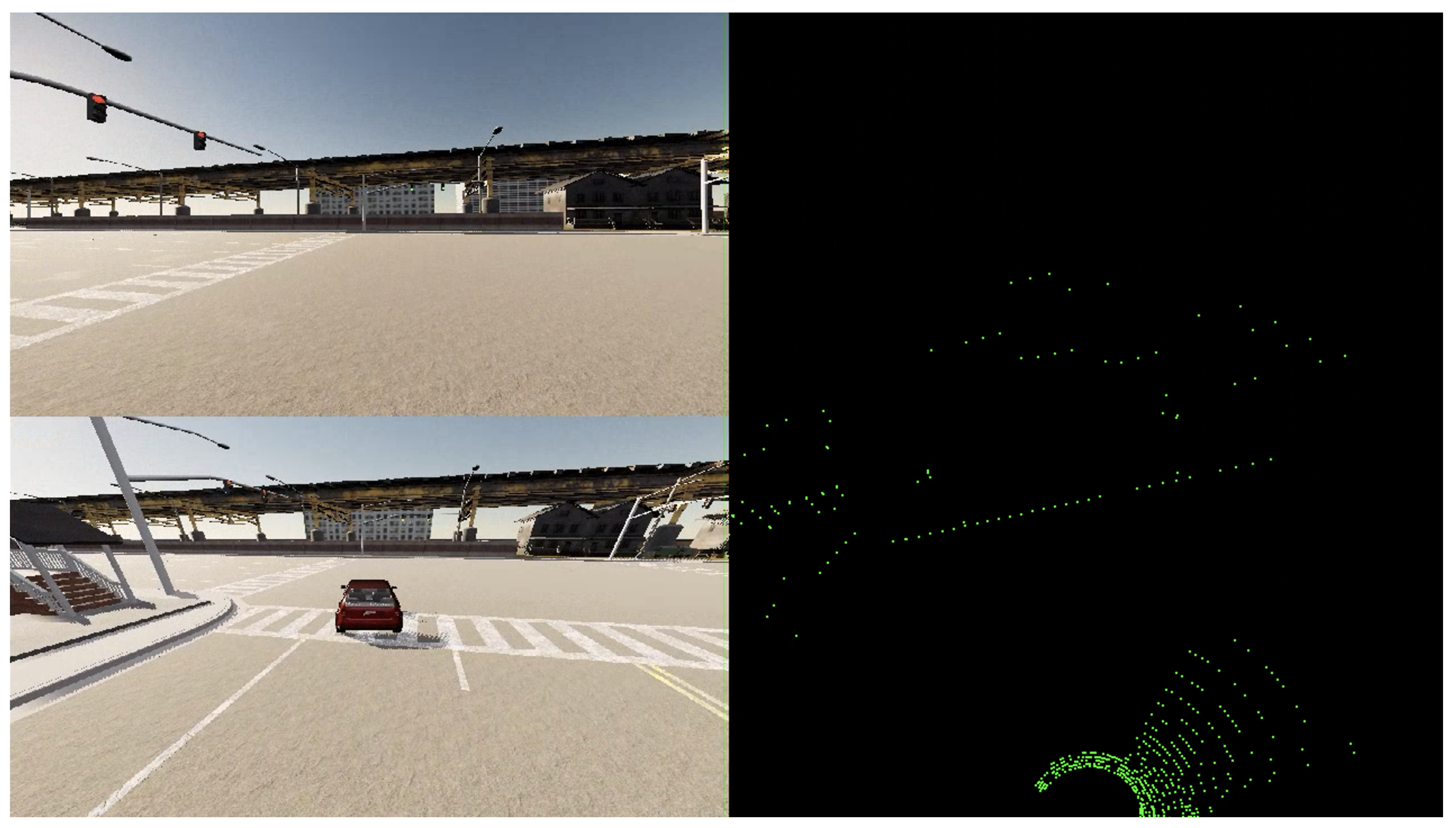

Figure 2 illustrates exemplar outputs generated by the CARLA simulator. Parts of figure on the left side show outputs from RGB front camera and RGB camera behind the vehicle. Part of figure on the right shows point-cloud output from LiDAR sensor.

2.3. Related Works About Autonomus Driving

Several contemporary investigations have harnessed the CARLA simulator to push the boundaries of reinforcement-learning–based autonomous driving. For instance, Raw2Drive: Reinforcement Learning with Aligned World Models for End-to-End Autonomous Driving (implemented in CARLA v2)

[44] introduces a cohesive agent that fuses learned world models with policy optimization to achieve robust, end-to-end vehicle control. In CuRLA: Curriculum Learning Based Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving

[45], the authors confront the challenge of sluggish policy convergence in standard DRL agents by embedding a structured curriculum, thereby accelerating skill acquisition across progressively complex driving tasks. Finally, Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Personalized Autonomous Driving

[46] presents a novel framework in which a multi-objective RL agent not only navigates autonomously but dynamically modulates its driving style according to user-defined preferences, balancing safety, efficiency, and comfort.

3. Review of Reinforcement Learning Approaches

Autonomous driving has emerged as a focal area of scientific inquiry, with reinforcement learning methods occupying a central role due to their inherent suitability for sequential decision–making problems. In this thesis, we undertake a comprehensive review of the literature on artificial intelligence techniques applied to autonomous driving, placing particular emphasis on reinforcement learning approaches.

The tables below provide a systematic summary of the surveyed publications, detailing the state spaces, action spaces, and reward functions employed in prior work. The first table

Table 2 provides a concise but comprehensive overview of the state and action spaces employed across the surveyed studies. The second table

Table 3 then details, in corresponding sequence, the reward functions formulated and utilized within those same works, thereby facilitating direct comparison and analysis.

Table 2 and

Table 3 present a comparative overview of the reviewed studies, defining the state and action spaces of each actor alongside the corresponding reward functions utilized.

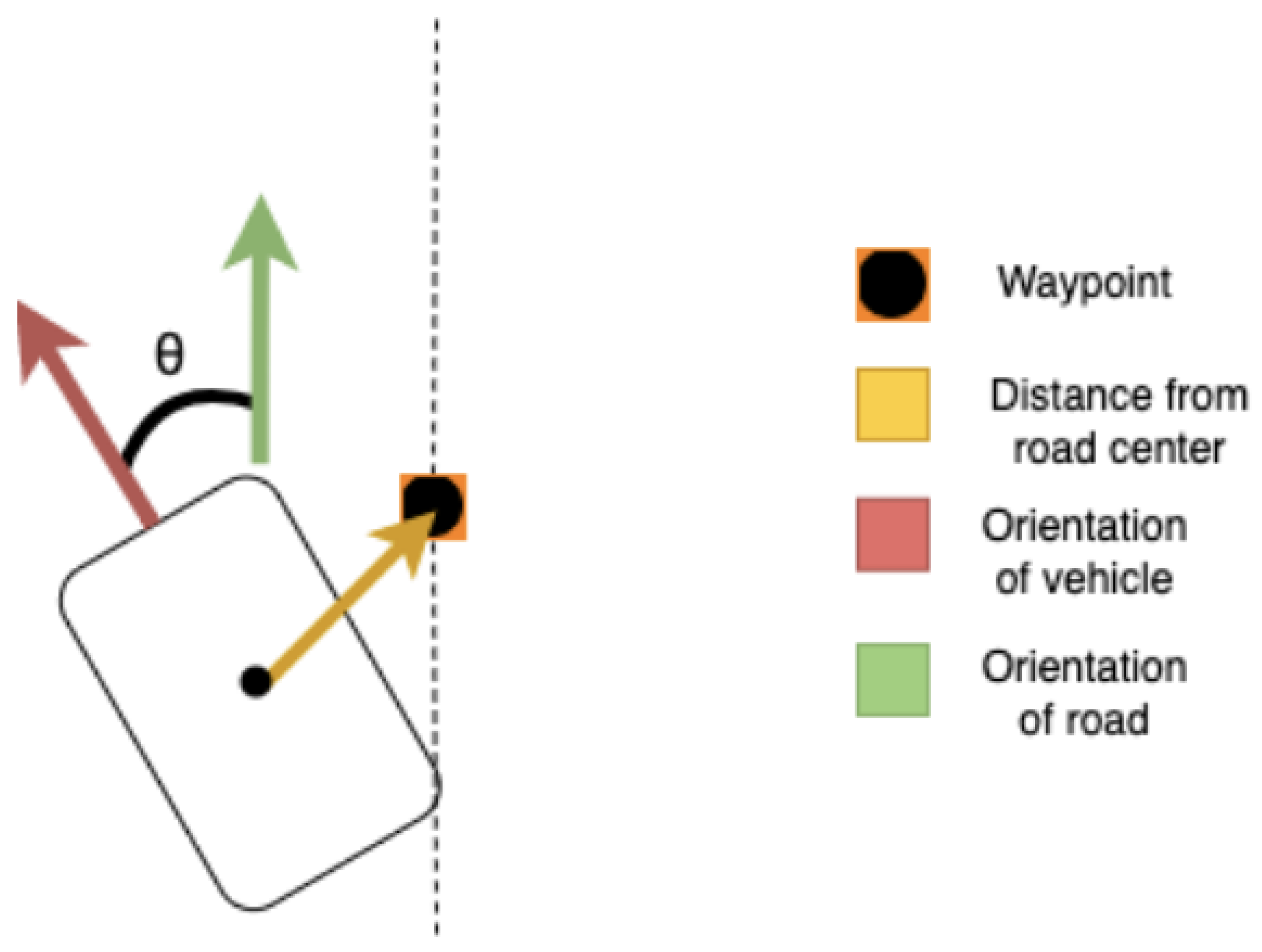

Authors in “Implementing a Deep Reinforcement Learning Model for Autonomous Driving[6],” describes an agent whose state representation includes the current throttle and brake input, the most recent steering command, the lateral distance to the closest waypoint, and the angular deviation between the vehicle’s orientation and the direction of the road.

Based on this observation space, the agent predicts the next steering, throttle, and brake values.

Figure 3 illustrates the model structure presented in this study.

Figure 3 illustrates the methodology employed in this work. The angular component of the state vector quantifies the deviation between the vehicle’s orientation and the tangent of the road curve at the vehicle’s current location.

The reward function is primarily driven by the vehicle’s velocity with respect to a defined speed range. It incorporates the following variables:

. The reward shaping term

is defined as:

The remaining variables are described in

Table 4, which provides their meanings and configuration details.

In their study on deep reinforcement learning for autonomous vehicle control in CARLA, Pérez-Gil et al. [

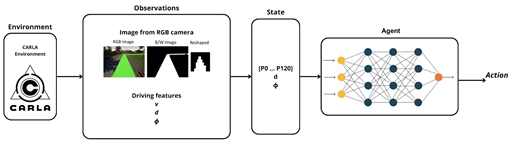

7] proposed four distinct agent architectures that differ primarily in their input preprocessing and neural network structures.

The first configuration, referred to as the DRL-Flatten-Image agent, processes RGB camera frames by converting them into binary images, reshaping them into an matrix, and flattening this into a 121-dimensional vector. This vector is then augmented with the vehicle’s lateral distance to the lane center and the angular deviation between the vehicle’s heading and the road’s tangent direction.

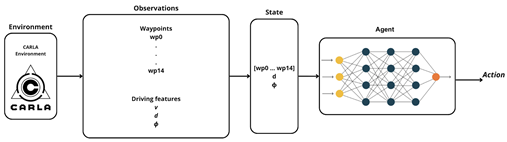

The second approach, known as DRL-CARLA-Waypoints, eliminates image processing altogether and instead leverages a 15-dimensional vector of route waypoints generated by the CARLA simulator. It retains the same geometric features used in the first agent: lane offset and heading deviation.

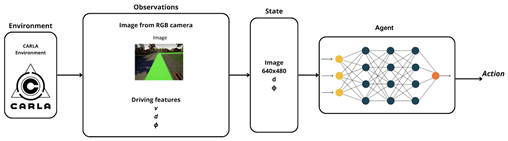

The third variant, DRL-CNN, directly ingests high-resolution RGB images () and employs a convolutional neural network to extract spatial features. These features are fused with geometric cues before being passed to the policy network.

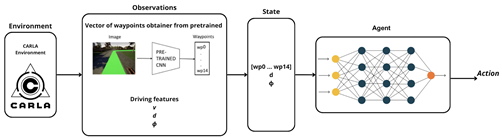

The fourth and final variant, DRL-Pre-CNN, introduces a pretrained convolutional backbone that processes the visual input externally to generate a waypoint vector. This output is combined with spatial features (distance and orientation) and used as input for the control model.

All agents use steering and throttle commands for control. Although braking is supported in the action space, it is unused in these experiments due to the lack of dynamic obstacles; regenerative braking was considered sufficient.

Each of the proposed agents applies the same reward function, described previously in

Table 3 and denoted

here. This function rewards lane-aligned forward motion, penalizes lateral drift and heading misalignment, and includes harsh penalties for collisions or unintended lane departures. Additionally, a terminal reward of 100 is awarded upon successfully reaching the target destination.

Table 5 below shows each of the approaches to system architecture for each agent proposed by Pérez-Gil et al. [

7]. The figures presented in the table show how the architecture worked and connect with the description for this article.

Gutierrez-Moreno et al. [

8] focused on reinforcement learning for intersection handling under dense traffic conditions. Their agent architecture was intentionally minimal, using only two continuous variables in the state space: the vehicle’s current speed and its distance from the intersection.

The action space was reduced to two discrete maneuvers: stop (set speed to 0 m/s) or proceed (set speed to 5 m/s). This reduction simplifies decision-making but limits adaptability to more complex traffic environments.

The reward function, shown in

Table 3, integrates multiple components to guide safe and efficient behavior. Standard driving rewards were scaled by a velocity coefficient

, while successful intersection traversal awarded a fixed positive reward. Collisions incurred a penalty of

, and each timestep included a diminishing time-based penalty of

, where

is the episode timeout threshold. This structure encourages timely and collision-free intersection negotiation.

Another widely cited benchmark in the field is the original CARLA simulator paper by Dosovitskiy et al. [

9]. Their agent was designed to perform autonomous urban driving using an A3C (Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic) algorithm.

The state input included two sequential RGB frames, as well as auxiliary features: current velocity, distance to the goal, and estimated collision damage. The action space comprised steering, throttle, and brake signals.

The reward function — listed in

Table 3 — was defined as a time-differential weighted sum of five terms: reduction in distance to goal, change in velocity, increase in collision damage, sidewalk intersection penalty, and opposite lane penalty.

Table 6 provides a detailed explanation of the individual terms in this reward function, which models progress and penalizes violations with granular time-based updates.

Li et al. [

10] introduced a model named Think2Drive, which integrates world modeling and latent representations to enhance policy learning efficiency in urban driving scenarios.

The agent’s state input is constructed from a bird’s eye view (BEV) semantic segmentation map of size , with 34 static object channels (e.g., lane markings) and 4 channels per dynamic object class (e.g., vehicles). Each dynamic object is annotated with a temporal mask , encoding its location history at the specified timesteps. The current velocity is also included in the input.

Unlike previous agents that learn continuous control directly, the Think2Drive agent selects from a discrete set of 30 predefined driving maneuvers. Each maneuver is represented by a fixed combination of steering, throttle, and braking values. This approach reduces policy complexity while allowing temporal reasoning through latent modeling.

The reward function — outlined in

Table 3 — is composed of four components: instantaneous velocity

, distance traveled

, deviation from lane center

, and steering smoothness

. These terms are weighted by task-specific coefficients

, respectively.

Table 7 summarizes each reward component and its intended contribution to the learning process.

Nehme et al. [

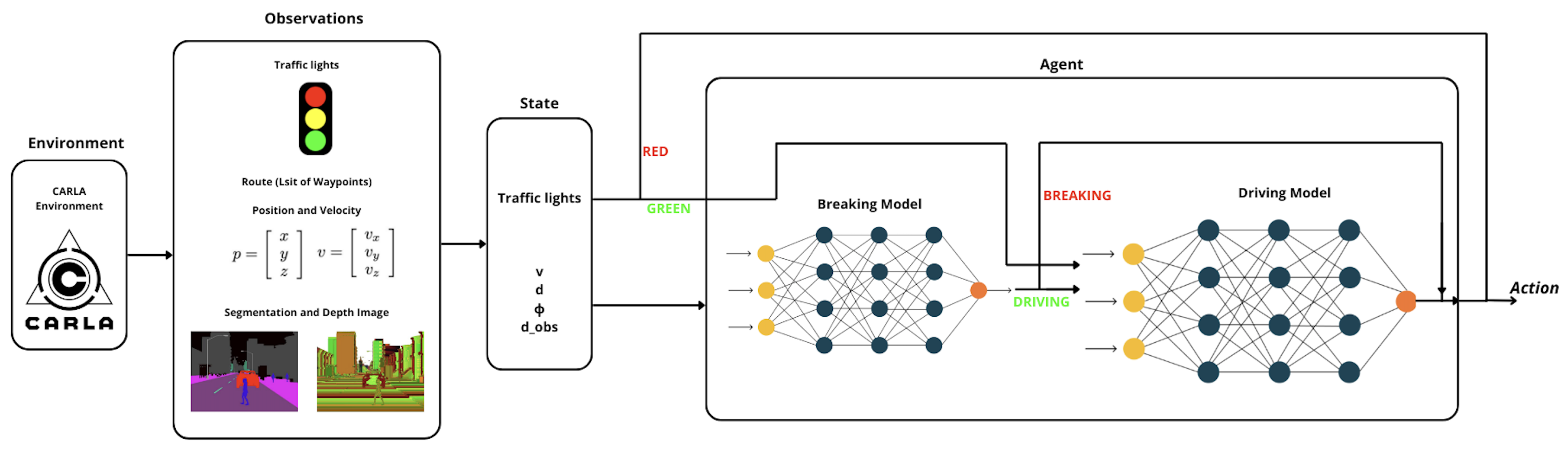

11] proposed a modular reinforcement learning framework for autonomous driving in urban environments, separating braking and maneuvering into two specialized sub-models. This architecture enables decoupled decision-making and improves interpretability.

The final agent integrates a braking model that determines whether to stop or continue driving, and a driving model that selects one of five maneuvers: go straight, turn left, turn right, turn slightly left, or turn slightly right. The input to the full system includes traffic light color, the agent’s lateral deviation d from the lane center, angular deviation from the road direction, velocity v, and distance to the nearest obstacle , computed from a depth map.

Figure 4 depicts the integrated system architecture, comprising both the braking and driving models. Solution proposed by Nehme et al. [

11] is composed from two models(breaking and driving) and final architecture which i composed from these two models is shows on figure below.

The reward design for this model is also bifurcated. The braking model’s reward function is based on whether the vehicle stops appropriately relative to its velocity and obstacle proximity, with positive rewards for correct braking and penalties for dangerous decisions or collisions.

The driving model’s reward incorporates deviation from lane center d, angular deviation , and the output of a suboptimal policy used as a performance baseline. Collisions result in a strong penalty, while safe trajectory tracking aligned with is positively reinforced.

The full reward formulation is provided in

Table 3, and each parameter is further described in

Table 8.

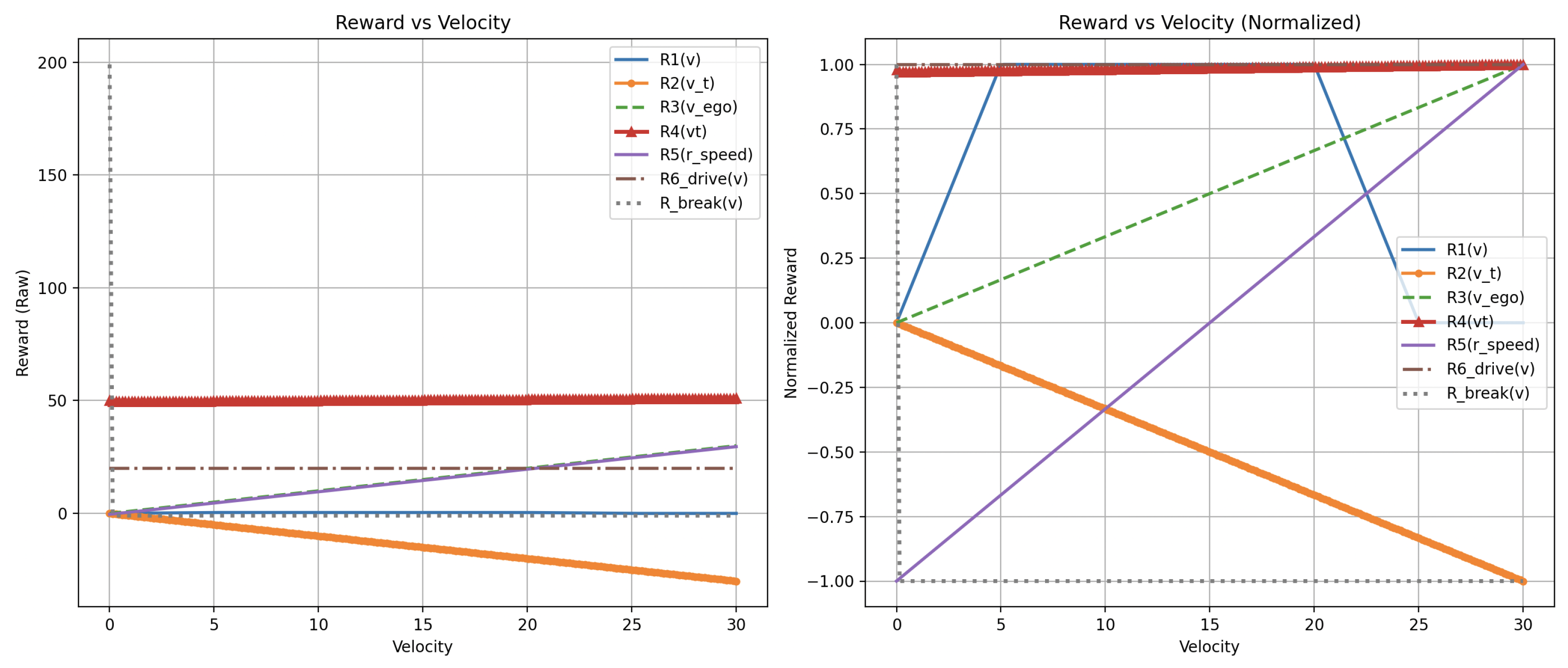

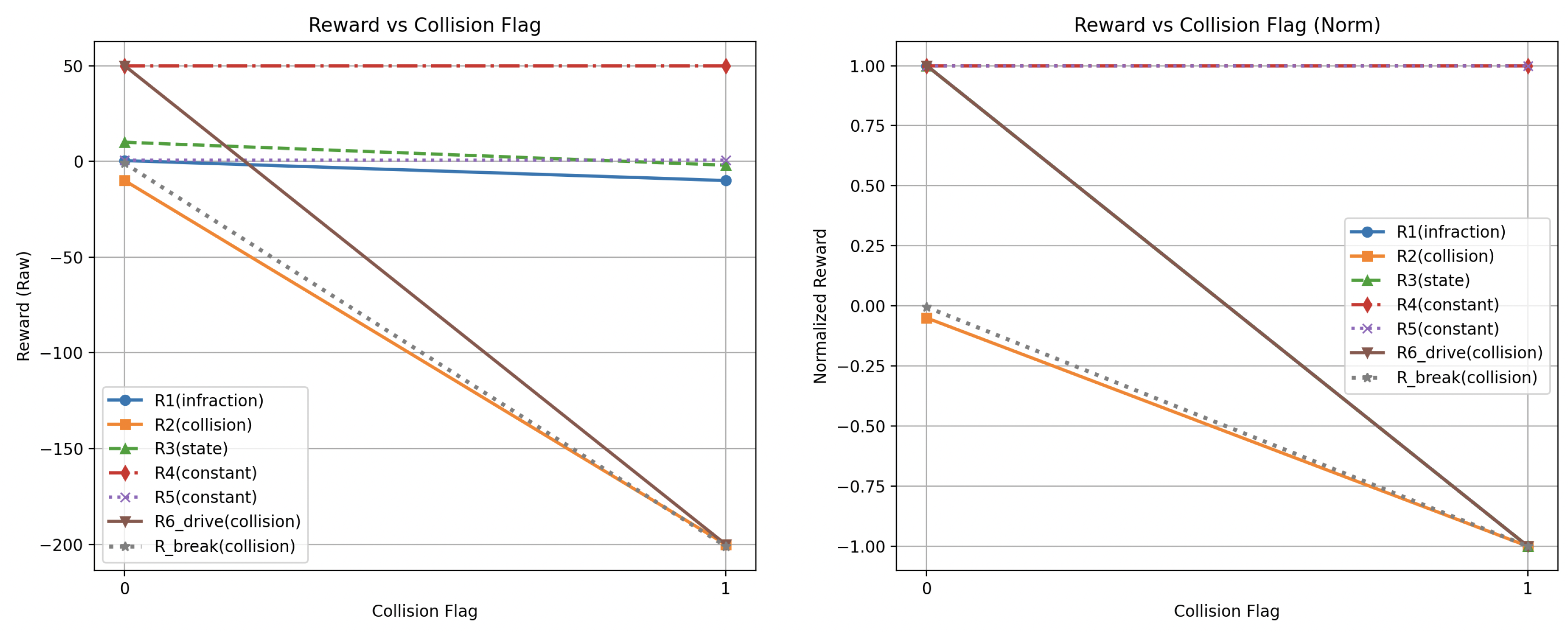

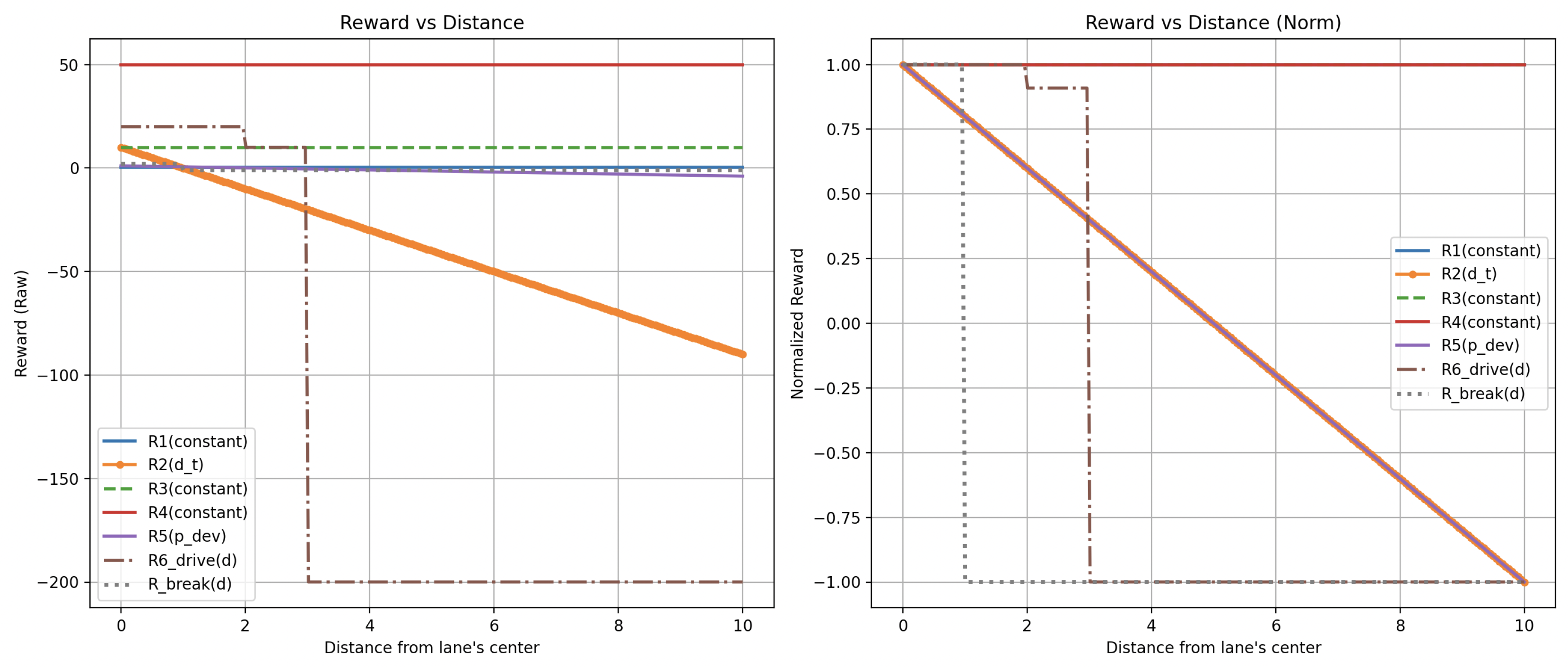

To further contextualize the reviewed works, a supplementary comparison of the reward functions is presented below. The following graphs visualize how different reward signals behave under variations in three critical variables:

- vehicle velocity - collision occurrence - lateral deviation from the lane center

For consistency and interpretability, other parameters in each reward equation were fixed at constant values to avoid scaling extremes. Additionally, flat reward terms—those not dependent on the parameter being evaluated—are included as horizontal lines to indicate their constant contribution.

Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 below illustrate how the reward function values reported in the reviewed articles vary in response to changes in a single parameter. The reward functions variable values have been evaluated by systematically varying three principal parameters within each function. When adjusting one parameter, the remaining parameters were held constant selected to minimize their influence on the reward outcome and to prevent the emergence of extreme reward values.

4. Gaps and Limitations in RL-Based Methods

While the previously reviewed studies present a diverse range of methodologies for autonomous driving within the CARLA simulation environment, several persistent challenges and open research questions remain. These gaps reflect both the limitations inherent in the design of current reinforcement learning agents and the complexities of real-world deployment scenarios. Identifying and understanding these issues is crucial for improving the scalability, safety, and applicability of RL-based systems in autonomous driving.

The primary limitations observed across the surveyed literature are as follows:

Limited Generalization to Real-World Scenarios — Some RL-based models exhibit strong performance within narrowly defined simulation environments but fail to generalize to the complexities of real-world driving. For instance, the agent described in

Reinforcement Learning-Based Autonomous Driving at Intersections in CARLA Simulator [8] was trained under constrained conditions using a binary action set (stop or proceed). Although suitable for intersection navigation in simulation, this minimalist approach lacks the flexibility and robustness required for dynamic urban environments characterized by unpredictable agent interactions, diverse traffic rules, and complex road layouts.

Pipeline Complexity and Practical Deployment Issues — Advanced RL systems often involve highly layered and interdependent components, which, while enhancing learning performance in simulation, may hinder real-time applicability. The architecture proposed in

Safe Navigation: Training Autonomous Vehicles using Deep Reinforcement Learning in CARLA [11] integrates multiple sub-models for driving and braking decisions. Despite its efficacy within the training context, the increased architectural complexity poses challenges in deployment scenarios, such as increased inference latency, reduced system interpretability, and difficulties in modular updates or extensions.

-

Reward Function Design and Safety Trade-offs — Crafting a reward function that effectively balances task completion with safe, rule-compliant behavior remains an ongoing challenge. Poorly calibrated rewards may inadvertently incentivize agents to exploit loopholes or adopt high-risk behaviors that maximize rewards at the cost of safety. The reward formulation presented in

Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Control for Autonomous Vehicles in CARLA [7] mitigates this risk by incorporating lane deviation, velocity alignment, and collision penalties. Nevertheless, even well-intentioned designs can result in unintended behaviors if the agent learns to over-prioritize specific features, highlighting the need for reward tuning and safety regularization.

Several works have specifically tackled these limitations by employing advanced RL strategies. Yang et al. (2021) developed uncertainty-aware collision avoidance techniques to enhance safety in autonomous vehicles [

85]. Fang et al. (2022) proposed hierarchical reinforcement learning frameworks addressing the complexity of urban driving environments [

86]. Cui et al. (2023) further advanced curriculum reinforcement learning methods to tackle complex and dynamic driving scenarios effectively [

84]. Feng et al. (2025) utilized domain randomization strategies to enhance the generalization of RL policies, significantly improving performance across varying simulated environments [

90].

5. Imitation Learning (IL) for Autonomous Driving

5.1. Core Concepts

Imitation Learning (IL) is a machine learning paradigm in which an agent learns to perform tasks by mimicking expert behavior, typically that of a human. Unlike reinforcement learning, where the agent discovers optimal actions through trial and error and reward feedback, IL infers a policy directly from expert demonstrations by mapping perceptual inputs to control outputs.

During training, the agent observes example trajectories and attempts to replicate the expert’s decisions in the same contexts. The aim is for the model to internalize the expert’s policy, enabling generalization to similar, unseen scenarios.

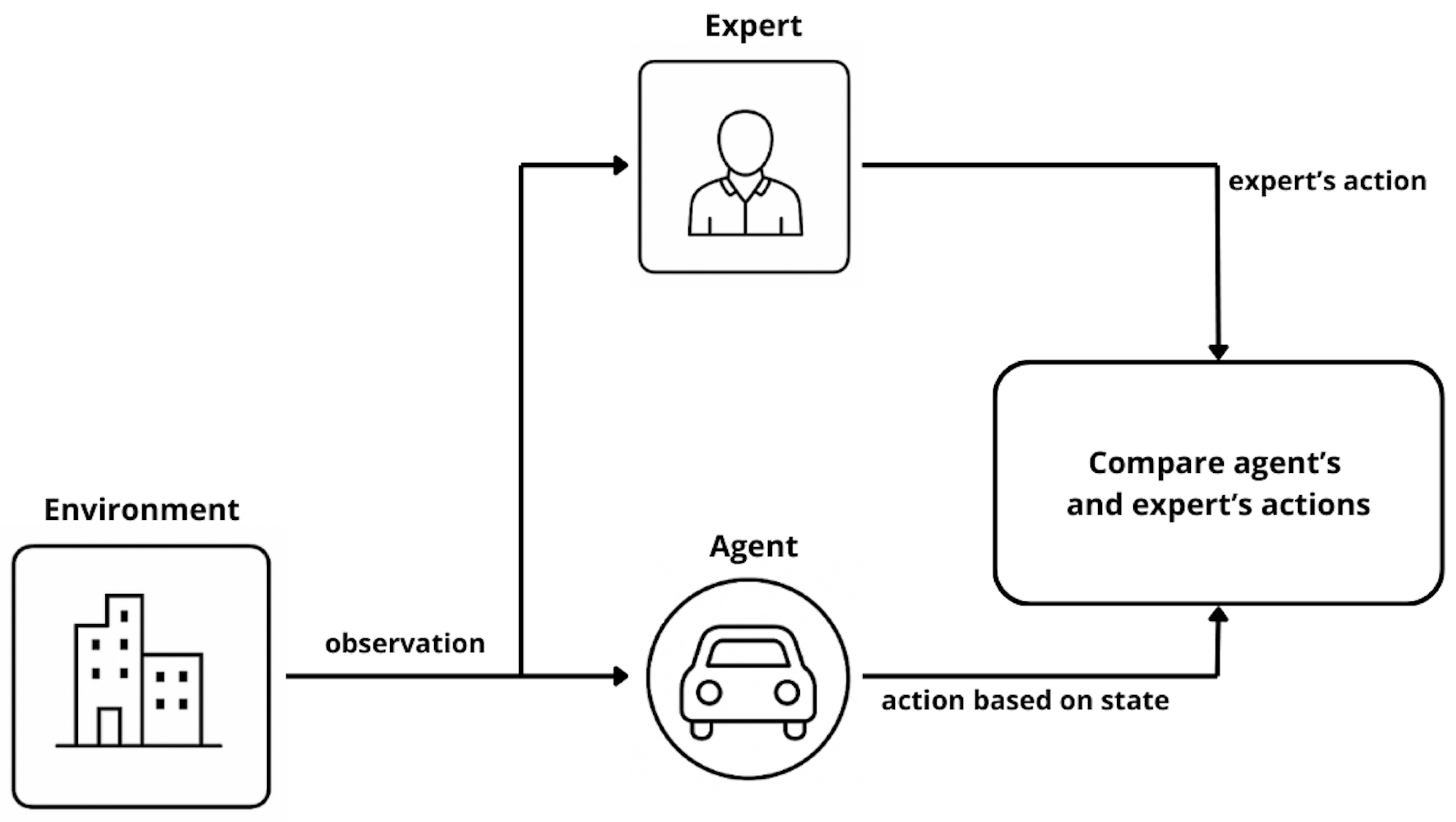

The overall process of IL is illustrated in

Figure 8.

As shown above, IL shares many components with reinforcement learning, though the learning mechanism differs. The key actors in the IL framework are:

Agent — The learner that interacts with the environment. Unlike in reinforcement learning, the agent does not rely on scalar rewards but instead learns to imitate the expert’s demonstrated behavior.

Expert — Typically a human operator or a pre-trained model that provides high-quality demonstration trajectories. These trajectories serve as the ground truth for training.

All remaining terminology, such as state, action, and environment, corresponds to the definitions previously introduced in Section 2.1 on reinforcement learning.

IL algorithms are typically categorized along two orthogonal dimensions:

Model-based vs. Model-free — Model-based approaches attempt to build a transition model of the environment and use it for planning. Model-free techniques rely solely on observed expert trajectories without reconstructing the environment’s internal dynamics.

Policy-based vs. Reward-based — Policy-based methods directly learn a mapping from states to actions, while reward-based methods (such as inverse reinforcement learning) infer the expert’s reward function before deriving a policy.

A selection of widely used IL techniques is summarized in

Table 9.

Recent advancements in imitation learning also demonstrate promising outcomes. Luo et al. (2023) improved behavioral cloning techniques by introducing adaptive data augmentation methods, significantly enhancing IL agents’ performance in novel driving scenarios [

92]. Moreover, Mohanty et al. (2024) utilized inverse reinforcement learning to achieve human-like autonomous driving behaviors in CARLA, emphasizing the effectiveness of learning from expert demonstrations [

93].

5.2. Reviewed IL-Based Architectures

IL has gained considerable traction in autonomous driving research due to its ability to leverage expert demonstrations and simplify policy learning. This section reviews key publications that implement IL-based approaches for autonomous vehicle control.

The reviewed works differ in their perceptual inputs, control representations, and agent architectures.

Table 10 summarizes the state and action spaces for each model discussed.

Table 10 offers a comparative overview of several IL approaches in autonomous driving, focusing on the modalities used for perception and control. Each agent architecture incorporates different combinations of visual, sensor, and navigation inputs to compute real-time driving decisions.

The model proposed by Codevilla et al. [

12], titled

End-to-End Driving via Conditional IL, was evaluated both in simulation (CARLA) and on a scaled-down physical platform (a 1/5-scale Traxxas Maxx truck). Although the physical agent used a multi-camera rig with three forward-facing lenses (center and ±30°), the simulation experiments relied solely on the central camera.

The agent received RGB frames and a high-level directional command (e.g., “turn left,” “go straight,” “turn right”) corresponding to an upcoming intersection. Based on these inputs, the policy network produced continuous steering and acceleration values.

In their work

Learning by Cheating, Chen et al. [

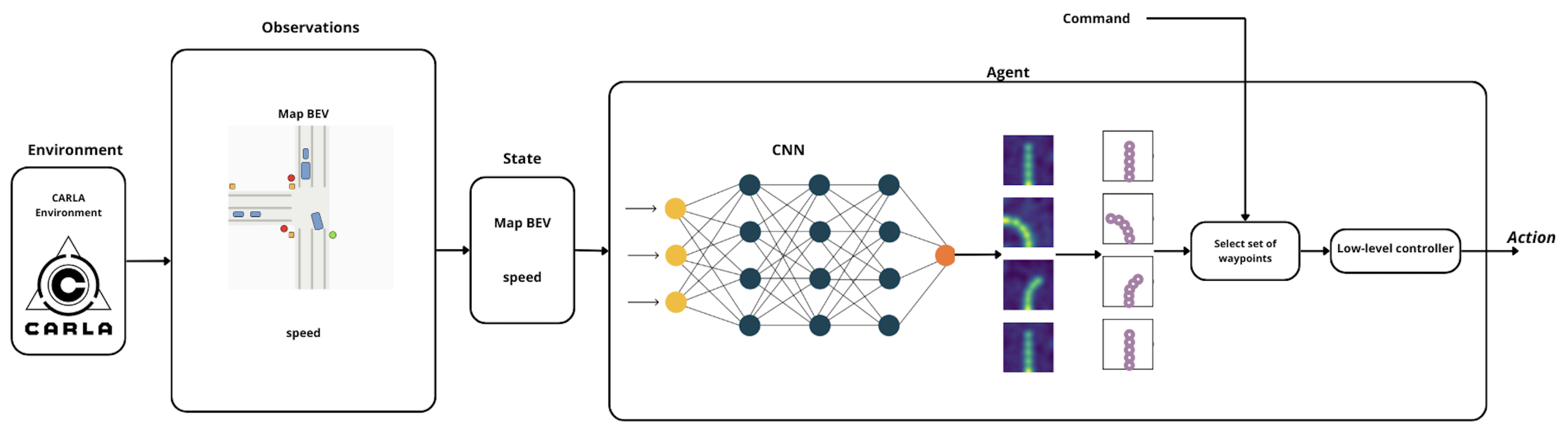

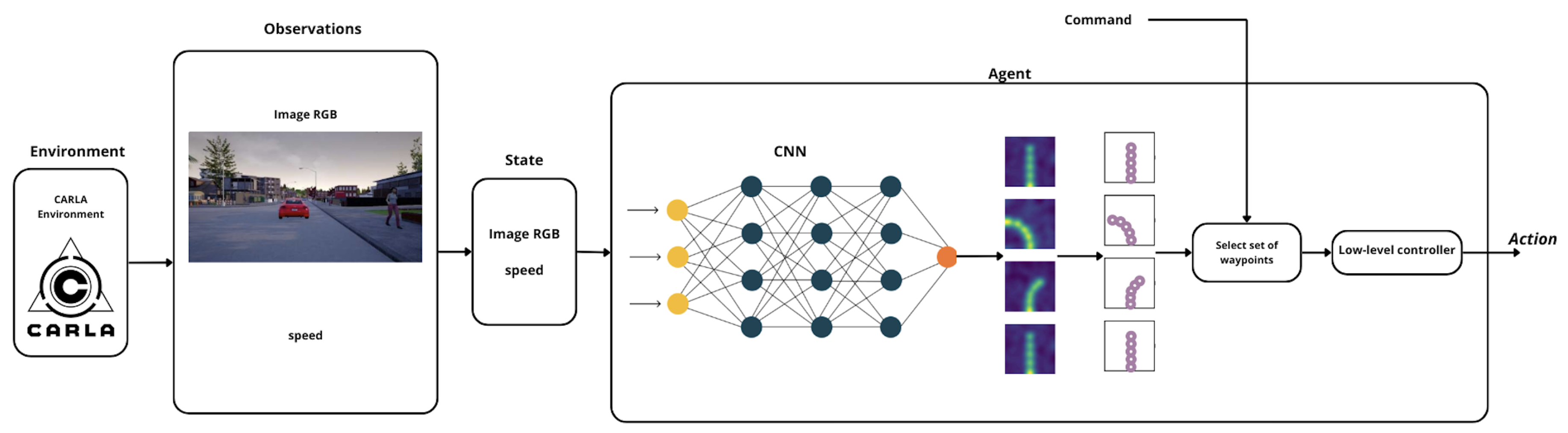

13] introduced a hierarchical two-stage training framework involving both privileged and sensorimotor agents.

The privileged agent is trained directly on expert demonstrations using a compact, bird’s-eye view (BEV) semantic map containing annotations for lanes, traffic lights, and dynamic agents, along with vehicle speed and navigation command. This privileged model outputs heatmaps of target waypoints, which are passed through a controller to produce steering, braking, and throttle commands.

In contrast, the sensorimotor agent has no access to semantic maps. Instead, it receives monocular RGB images, speed data, and commands and learns to mimic the outputs of the privileged agent. This imitation occurs in terms of heatmap prediction, enabling the sensorimotor agent to benefit from the intermediate spatial reasoning learned by the expert.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 visualize the architectures of the privileged and sensorimotor agents, proposed in

Learning by Cheating [

13] , respectively.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 highlight differences in architecture of privileged and sensorimotor approaches.

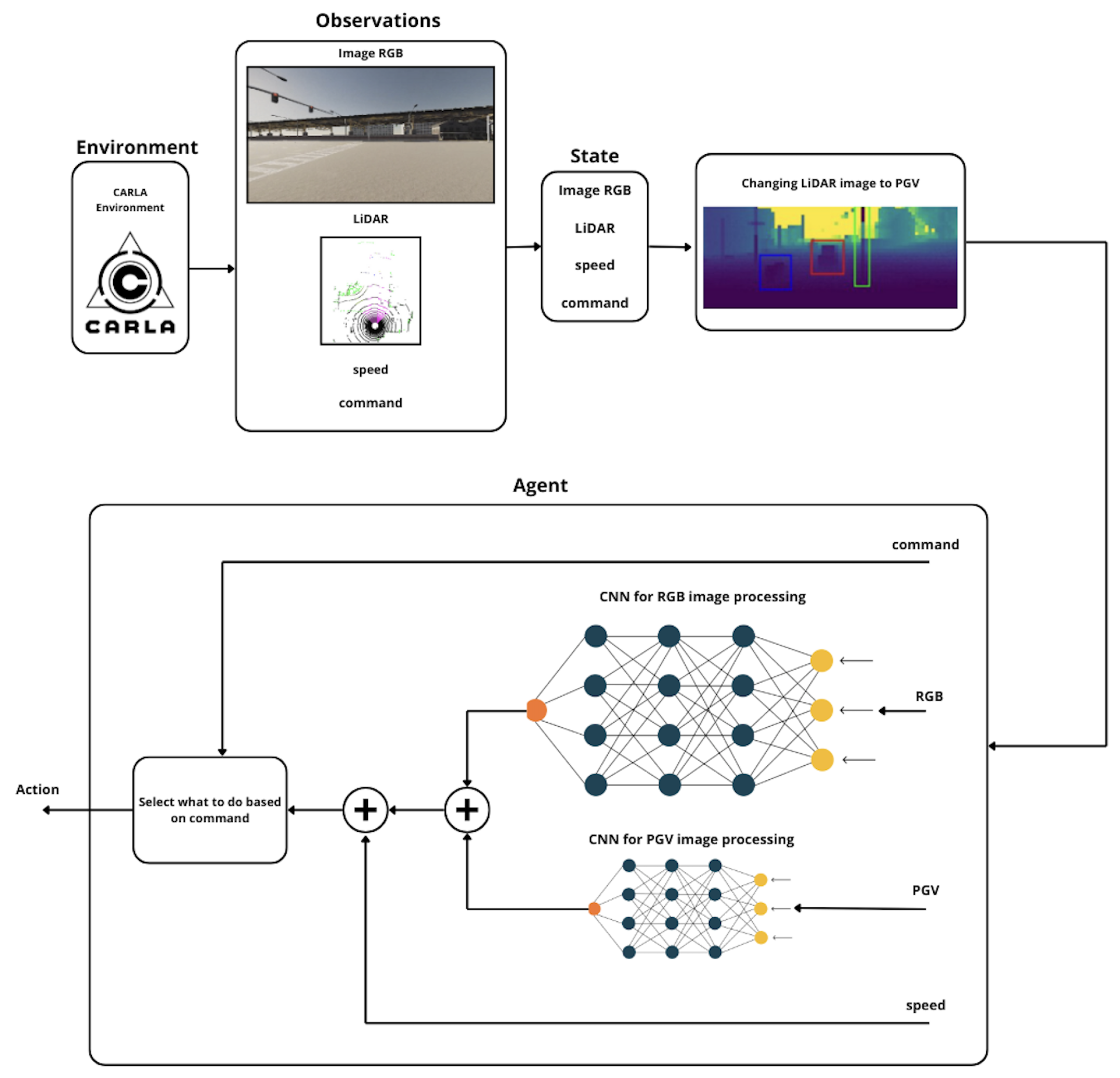

Eraqi et al. [

14] proposed a unified model titled

Dynamic Conditional IL for Autonomous Driving. The agent processes four types of inputs: RGB camera images, vehicle speed, LiDAR measurements, and a high-level navigation command.

LiDAR data are transformed into a polar grid view (PGV) representation and passed through a neural encoder. Based on the incoming command—e.g., “turn left,” “follow lane,” “go straight”—the model activates a corresponding conditional branch that outputs a three-element control vector: steering angle, brake intensity, and throttle.

The whole system proposed in

Dynamic Conditional IL for Autonomous Driving were shown in

Figure 11 below. The figure shows a simplified version of the full architecture from observation from the CARLA environment to finally agent choosing an action.

5.3. IL in the Context of This Paper - Hybrid Solutions

IL, while effective for quickly learning behaviors from expert demonstrations, struggles with limited generalization—agents often fail when encountering situations not covered in the training data. On the other hand, Reinforcement Learning excels at learning through exploration and can achieve high performance, but it is computationally expensive and prone to instability. Combining these two approaches helps to mitigate their weaknesses: expert demonstrations can guide and accelerate learning, reducing unsafe or inefficient exploration. At the same time, the reward-driven nature of RL enables agents to refine their behavior and adapt to novel scenarios. Within the scope of this review, it is important to highlight the increasing synergy between IL and reinforcement learning in autonomous driving systems.

One commonly adopted strategy involves using IL to initialize an agent’s policy based on expert demonstrations. This pretrained policy serves as a robust foundation for subsequent reinforcement learning, which further refines the policy through exploration and reward optimization. This two-stage learning process improves convergence, particularly in environments with sparse or delayed rewards. A practical example of this approach can be found in the paper "Driving in Real Life with Inverse Reinforcement Learning", where the authors successfully apply it to real-world urban driving scenarios, combining demonstration-based pretraining with reinforcement learning to handle complex traffic interactions [

51].

Another notable framework that bridges the gap between imitation and reinforcement learning is Generative Adversarial IL described, as introduced in the paper bearing the same title. GAIL eliminates the need for an explicit reward function by introducing a discriminator network that learns to distinguish between expert-generated and agent-generated trajectories. The agent, acting as a generator, is rewarded when its behavior successfully fools the discriminator into misclassifying it as expert behavior. This adversarial structure enables the agent to learn optimal behavior patterns directly from demonstrations without handcrafted reward engineering [

52].

In the paper "CIRL: Controllable Imitative Reinforcement Learning for Vision-based Self-driving", IL and reinforcement learning are combined in a two-stage process. First, the agent undergoes pretraining using expert demonstrations, learning basic behaviors through classical behavioral cloning. This allows the agent to begin exploration from a reasonable starting point, avoiding random and inefficient trial-and-error. Then, the policy is further optimized through reinforcement learning (using DDPG), where the agent learns to respond to rewards and refine its decisions. This combination accelerates learning, improves training stability, and enables the agent to discover strategies that surpass those demonstrated by the expert [

49].

The authors of "GRI: General Reinforced Imitation and Its Application to Vision-Based Autonomous Driving" propose a simple method for combining expert demonstrations and environment exploration within a unified training process. GRI is based on the assumption that expert data represent ideal behavior, and each expert action is assigned a constant, high reward. In practice, the RL agent learns from two sources: (1) exploration of the environment and (2) demonstration data, which are fed into a shared replay buffer with artificially assigned rewards. This allows the agent to benefit from expert knowledge continuously during training, without requiring a separate pretraining phase via IL. GRI is compatible with any off-policy RL algorithm, such as DQN or SAC, and has been shown to significantly improve learning efficiency and generalization, as demonstrated in both CARLA and Mujoco environments [

50].

In the paper "Learning to drive using sparse imitation reinforcement learning", the authors propose a method in which a reinforcement learning agent is guided by a so-called "sparse expert"—a simple set of rules that activate only in critical situations, such as avoiding collisions or responding to traffic lights. Instead of providing full expert trajectories, this sparse expert suggests correct actions only in selected states, significantly reducing the cost of expert supervision. During training, the agent doesn’t select actions solely based on its own policy but uses a probabilistic blending mechanism: its decisions are biased toward the expert’s suggestions when those are available. This allows the agent to remain safe in high-risk scenarios while retaining the ability to explore freely elsewhere. As a result, the agent quickly learns behaviors aligned with expert intuition, while still developing its own strategies that can achieve higher rewards than the hand-crafted rules alone [

53].

In "Soft Q IL (SQIL)", the researchers present a very simple and easy-to-implement method for training an agent using expert demonstrations. Instead of separating IL and reinforcement learning into distinct phases, SQIL uses a standard RL algorithm (Soft Q-Learning) with a simple yet effective reward structure: expert data are assigned a fixed reward of 1, while the agent’s own exploratory data receive a reward of 0. All experiences are placed in a single replay buffer and treated as regular RL transitions. As a result, the agent is naturally guided toward imitating expert-like behaviors, since only those yield positive rewards. Although originally applied to synthetic environments such as MuJoCo and Car Racing, this methodology holds strong potential for future use in autonomous driving, where cleanly integrating expert demonstrations into the RL framework remains a key challenge [

54].

These hybrid approaches represent a promising direction for training autonomous driving agents. They combine the sample efficiency and guidance of IL with the long-term optimization and robustness offered by reinforcement learning, making them particularly well-suited for complex, real-world driving environments.

Hybrid solutions combining imitation learning and reinforcement learning are gaining traction. Huang et al. (2024) proposed a hybrid architecture leveraging IL and RL to ensure safer autonomous driving behaviors, demonstrating enhanced generalization capabilities in CARLA [

89]. Kim and Cho (2025) similarly fused reinforcement and imitation learning methods, significantly improving vehicle safety in complex scenarios [

94].

6. Comparative Analysis and Research Implications

The comparative review of reinforcement learning and IL approaches for autonomous driving in the CARLA simulator reveals distinct strengths and limitations for each paradigm.

Reinforcement learning offers flexibility in agent design and supports end-to-end learning of control policies in diverse driving scenarios. Its fine-grained control capabilities and adaptability make it particularly effective in environments where reward signals can be precisely defined. However, RL methods are often highly sensitive to reward formulation and hyperparameter tuning. Poorly designed rewards can lead to suboptimal or unsafe behaviors, and even well-trained policies may fail to generalize when deployed under different conditions or sensor configurations.

IL, on the other hand, significantly reduces training time by leveraging expert knowledge and bypassing the need for explicit reward engineering. These methods typically converge faster and demonstrate smooth control behaviors in known environments. Nonetheless, they often suffer from limited generalization outside the distribution of demonstrated behaviors, making them susceptible to compounding errors in unfamiliar scenarios.

To address these limitations, hybrid approaches are gaining traction—particularly those that initialize policies via IL and then refine them using reinforcement learning. Such methods have shown promise in enhancing both sample efficiency and policy robustness by combining the advantages of both paradigms.

Future research should focus on advancing these hybrid techniques, particularly in areas such as transfer learning between simulation and real-world domains, domain randomization for robustness, and policy interpretability. There is also a growing need to design learning frameworks that maintain performance while ensuring explainability and safety under dynamic, real-world conditions.

Table 11 below summarizes the results from the articles discussed. Authors of discussed articles focused on slightly different things but results can be described as below.

Table 10 presents a consolidated overview of all reviewed studies, detailing each work’s primary objective, the complexity of its proposed architecture, the intricacy of its testing environment, and the total number of driving and route scenarios evaluated. To facilitate a standardized comparison, both architectural and environmental complexity are quantified on a three-point scale (1–3), with “3” denoting the highest level of complexity. For example, an architecture that integrates multiple distinct models (e.g., [

11]) is assigned a complexity score of 2, and likewise, an environment encompassing several urban centers or diverse traffic elements receives an environmental complexity rating of 2.

7. Discussion

RL and IL represent two of the most prominent paradigms in autonomous driving research. Both have been extensively applied in the CARLA simulator to develop and benchmark intelligent driving agents.

RL-based methods are particularly well-suited for dynamic environments where reward functions can be defined to align with desired driving behaviors. These approaches enable agents to learn through exploration, offering fine-grained control, adaptability to continuous state spaces, and task-specific policy optimization. The ability to encode safety, comfort, and efficiency directly into the reward formulation makes RL a powerful tool for learning complex maneuvers.

Conversely, IL capitalizes on expert demonstrations to directly learn policies from human drivers or high-performing models. IL methods typically involve fewer hyperparameters, require less tuning, and exhibit faster convergence. Their reliance on expert knowledge makes them especially useful in safety-critical contexts or scenarios where reward design is ambiguous or error-prone.

Each paradigm, however, comes with notable trade-offs.

Reinforcement learning, while offering high flexibility and autonomy, often struggles with sensitivity to hyperparameter choices and reward shaping. Designing a reward function that promotes safe, generalizable behavior without inducing unintended shortcuts remains a key challenge. Moreover, RL agents typically require extensive training time and simulation rollouts, limiting sample efficiency and making them computationally intensive.

IL reduces these barriers by bypassing the need for hand-crafted rewards. It excels in sample efficiency, especially when high-quality demonstrations are available. However, IL methods are prone to covariate shift, where small deviations from the expert’s trajectories can compound over time, leading to performance degradation in out-of-distribution or novel situations.

To mitigate these issues, recent research has increasingly focused on hybrid strategies. A prominent example is the use of IL to pretrain agent policies, followed by RL fine-tuning. This approach helps accelerate convergence while improving generalization. GAIL and inverse reinforcement learning (IRL) represent more sophisticated hybrids, where the agent learns reward signals implicitly by aligning its behavior with expert trajectories via adversarial or inverse optimization frameworks.

These methods have shown strong potential in combining the sample efficiency and human priors of IL with the long-term optimization capabilities of RL.

The findings from this review suggest several key directions for future research at the intersection of reinforcement and IL in autonomous driving.

First, there is a pressing need to improve the generalization of learned policies beyond the training domain. Most RL and IL models evaluated in CARLA demonstrate strong performance within controlled simulation environments but face challenges when exposed to unseen conditions, such as novel traffic configurations, dynamic obstacles, or adverse weather. Addressing this gap will require advances in domain adaptation, data augmentation, and transfer learning.

Second, developing agents that can learn effectively from limited data remains an open challenge. Techniques that combine IL for initialization with off-policy or model-based RL hold promise for improving sample efficiency, particularly when real-world deployment data is scarce or costly to collect.

Third, interpretability and safety remain critical concerns. While deep RL and IL models can achieve impressive performance, their black-box nature complicates validation and certification for safety-critical applications like autonomous vehicles. Future work should prioritize explainable policies and transparent evaluation frameworks that go beyond cumulative rewards.

Finally, the integration of human-in-the-loop strategies — such as interactive demonstrations, preference-based feedback, or shared autonomy — offers a promising direction for aligning agent behavior with human values and operational constraints.

Together, these challenges point toward a broader research agenda focused not only on policy performance, but also on robustness, safety, and real-world applicability.

8. Conclusions

This review has analyzed and synthesized recent reinforcement learning and IL approaches for autonomous driving, with a focus on studies implemented within the CARLA simulator. The surveyed literature demonstrates that both paradigms offer unique advantages and face specific limitations in the context of simulated driving environments.

Reinforcement learning enables agents to learn flexible, task-optimized behaviors through exploration and interaction with their environment. Its strength lies in its adaptability and end-to-end training pipeline. However, RL often requires carefully engineered reward functions and extensive simulation time, and it struggles with generalization and sample inefficiency.

IL, in contrast, allows agents to quickly acquire competent policies from expert demonstrations, avoiding the complexities of reward design. IL methods typically converge faster and demonstrate smoother behavior in constrained settings. Nonetheless, their dependence on demonstration quality and vulnerability to distributional shifts can limit robustness in novel or unpredictable scenarios.

Several hybrid approaches have emerged to combine the strengths of both paradigms, including policy pretraining, adversarial learning, and inverse reinforcement learning. These strategies hold promise for overcoming individual limitations and advancing the state of the art in learning-based driving agents.

Looking ahead, the field is poised to benefit from continued integration between reinforcement learning and IL frameworks. Emerging trends point toward greater emphasis on safety, explainability, and real-world transfer, particularly as simulation-to-reality gaps remain a persistent obstacle for deploying learned agents beyond synthetic benchmarks.

CARLA has played a central role in standardizing experimental evaluation for autonomous driving, enabling reproducible comparisons across studies. However, expanding benchmarks to incorporate dynamic human interactions, multi-agent negotiation, and diverse sensory conditions will be essential for realistic policy development.

CARLA’s role as an open, extensible, and reproducible platform makes it a cornerstone for research at the intersection of machine learning and autonomous driving, particularly in contrast to closed-source, physics-only simulators.

This review underscores the importance of modular, interpretable, and sample-efficient approaches that combine expert guidance with autonomous learning. As learning-based methods mature, the focus must shift toward robust, certifiable agents capable of operating in open-world settings.

Ultimately, the next generation of autonomous driving systems will likely emerge from frameworks that blend data-driven learning, structured policy priors, and adaptive reasoning — all grounded in rigorous simulation and human-centered design.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.C. and B.K.; methodology, P.C. and B.K.; validation, M.S. and M.W.; formal analysis, M.S. and M.W.; investigation, B.K., M.S.; resources, P.C. ; writing—original draft preparation, P.C. and B.K.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and M.W.; visualization, P.C., B.K., M.S.; supervision, M.S. and M.W.; project administration, M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| RL |

Reinforcement Learning |

| IL |

IL |

| CARLA |

Car Learning to Act (Autonomous Driving Simulator) |

| CNN |

Convolutional Neural Network |

| BEV |

Bird’s Eye View |

| PGV |

Polar Grid View |

| IRL |

Inverse Reinforcement Learning |

| GAIL |

Generative Adversarial IL |

| MDP |

Markov Decision Process |

| PPO |

Proximal Policy Optimization |

| DQN |

Deep Q-Network |

| A3C |

Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic |

| LiDAR |

Light Detection and Ranging |

| RGB |

Red-Green-Blue (Color Image Input) |

| BC |

Behavioral Cloning |

| DAgger |

Dataset Aggregation |

| PID |

Proportional-Integral-Derivative (Controller) |

| PGM |

Probabilistic Graphical Model |

References

- Dhinakaran, M., Rajasekaran, R.T., Balaji, V., Aarthi, V., Ambika, S. (2024). Advanced Deep Reinforcement Learning Strategies for Enhanced Autonomous Vehicle Navigation Systems.

- Govinda, S., Brik, B., Harous, S. (2025). A Survey on Deep Reinforcement Learning Applications in Autonomous Systems: Applications, Open Challenges, and Future Directions.

- Kong, Q., Zhang, L., Xu, X. (2021). Constrained Policy Optimization Algorithm for Autonomous Driving via Reinforcement Learning.

- Kim, S., Kim, G., Kim, T., Jeong, C., Kang, C.M. (2025). Autonomous Vehicle Control Using CARLA Simulator, ROS, and EPS HILS.

- Malik, S., Khan, M.A., El-Sayed, H. (2022). CARLA: Car Learning to Act – An Inside Out.

- Razak, A. I. (2022). Implementing a Deep Reinforcement Learning Model for Autonomous Driving.

- Pérez-Gil, Ó., Barea, R., López-Guillén, E., Bergasa, L. M., Gómez-Huélamo, C., Gutiérrez, R., Díaz-Díaz, A. (2022). Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Control for Autonomous Vehicles in CARLA.

- Gutiérrez-Moreno, R., Barea, R., López-Guillén, E., Araluce, J., Bergasa, L. M. (2022). Reinforcement Learning-Based Autonomous Driving at Intersections in CARLA Simulator.

- Dosovitskiy, A., Ros, G., Codevilla, F., López, A., Koltun, V. (2017). CARLA: An Open Urban Driving Simulator.

- Li, Q., Jia, X., Wang, S., Yan, J. (2024). Think2Drive: Efficient Reinforcement Learning by Thinking with Latent World Model for Autonomous Driving (in CARLA-V2).

- Nehme, G., Deo, T. Y. (2023). Safe Navigation: Training Autonomous Vehicles using Deep Reinforcement Learning in CARLA.

- Codevilla, F., Müller, M., López, A., Koltun, V., Dosovitskiy, A. (2017). End-to-end Driving via Conditional IL.

- Chen, D., Zhou, B., Koltun, V., Krähenbühl, P. (2019). Learning by Cheating.

- Eraiqi, H. M., Moustafa, M. N., HÖner, J. (2022). Dynamic Conditional IL for Autonomous Driving.

- Abdou, M., Kamai, H., El-Tantawy, S., Abdelkhalek, A., Adei, O., Hamdy, K., Abaas, M. (2019). End-to-End Deep Conditional IL for Autonomous Driving.

- Li, Z. (2021). A Hierarchical Autonomous Driving Framework Combining Reinforcement Learning and IL.

- Arulkumaran, K., Deisenroth, M. P., Brundage, M., Bharath, A. A. (2017). A Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Brief Survey.

- Shrestha, A., Mahmood, A. (2019). Review of Deep Learning Algorithms and Architectures.

- Elavarasan, D., Vincent, P.M.D. (2020). Crop Yield Prediction Using Deep Reinforcement Learning Model for Sustainable Agrarian Applications.

- Zhou, Z., Chen, X., Li, E., Zeng, L., Lue, K., Zhang, J. (2019). Edge Intelligence: Paving the Last Mile of Artificial Intelligence With Edge Computing.

- Sutton, R.S., Barto, A.G. (1998). Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction.

- Lapan, M. (2022) Głębokie uczenie przez wzmacnianie. Praca z chatbotami oraz robotyka, optymalizacja dyskretna i automatyzacja sieciowa w praktyce.

- Cui, J., Liu, Y., Arumugam, N. (2019). Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning-Based Resource Allocation for UAV Networks.

- Shaukat, K., Luo, S., Varadharajan, V., Hameed, I., Xu, M. (2020). A Survey on Machine Learning Techniques for Cyber Security in the Last Decade.

- Ye, H., Li, G.Y., Juang, B.F. (2019). Deep Reinforcement Learning Based Resource Allocation for V2V Communications.

- Le, L., Nguyen, T.N. (2022). DQRA: Deep Quantum Routing Agent for Entanglement Routing in Quantum Networks.

- Scholköpf, B., Locatello, F., Bauer, S., Ke, N.R., Kalchbrenner, N., Goyal, A., Bengio, Y. (2021). Toward Causal Representation Learning.

- Huang, C., Zhang, H., Wang, L., Luo, X., Song, Y. (2022). Mixed Deep Reinforcement Learning Considering Discrete-continuous Hybrid Action Space for Smart Home Energy Management.

- Sogabe, T., Malla, D.B., Takayama, S., Shin, S., Sakamoto, K., Yamaguchi, K., Singh, T.P., Sogabe, M., Hirata, T., Okada, Y. (2018). Smart Grid Optimization by Deep Reinforcement Learning over Discrete and Continuous Action Space.

- Guériau, M., Cardozo, N., Dusparic, I. (2019). Constructivist Approach to State Space Adaptation in Reinforcement Learning.

- Abdulazeez, D.H., Askar, S.K. (2023). Offloading Mechanisms Based on Reinforcement Learning and Deep Learning Algorithms in the Fog Computing Environment.

- Mahadevkar, S.V., Khemani, B., Patil, S., Kotecha, K., Vora, D.R., Abraham, A., Gabralla, L.A. (2022). A Review on Machine Learning Styles in Computer Vision—Techniques and Future Directions.

- Shukla, I., Dozier, H.R., Henslee, A.C. (2022). A Study of Model Based and Model Free Offline Reinforcement Learning.

- Hyang, Q. (2020). Model-Based or Model-Free, a Review of Approaches in Reinforcement Learning.

- Beyon, H. (2023). Advances in Value-based, Policy-based, and Deep Learning-based Reinforcement Learning.

- Liu, M., Wan, Y., Lewis, F.L., Lopez, V.G. (2020). Adaptive Optimal Control for Stochastic Multiplayer Differential Games Using On-Policy and Off-Policy Reinforcement Learning.

- Banerjee, C., Chen, Z., Noman, N., Lopez, V.G. (2022). Improved Soft Actor-Critic: Mixing Prioritized Off-Policy Samples With On-Policy Experiences.

- Nikpour, B., Sinodinos, D., Armanfard, N. (2022). Deep Reinforcement Learning in Human Activity Recognition: A Survey.

- Kim, J., Kim, G., Hong, S., Cho, S. (2024). Advancing Multi-Agent Systems Integrating Federated Learning with Deep Reinforcement Learning: A Survey.

- Hofbauer, M., Kuhn, C., Petrovic, G., Steinbach, E. (2020). TELECARLA: An Open Source Extension of the CARLA Simulator for Teleoperated Driving Research Using Off-the-Shelf Components.

- Sakhai, M.; Wielgosz, M. Towards End-to-End Escape in Urban Autonomous Driving Using Reinforcement Learning. In: Arai, K. (Ed.) Intelligent Systems and Applications. IntelliSys 2023. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 823. Springer, Cham, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kołomański, M.; Sakhai, M.; Nowak, J.; Wielgosz, M. Towards End-to-End Chase in Urban Autonomous Driving Using Reinforcement Learning. In: Arai, K. (Ed.) Intelligent Systems and Applications. IntelliSys 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, vol 544. Springer, Cham, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sakhai, M.; Mazurek, S.; Caputa, J.; Argasiński, J.K.; Wielgosz, M. Spiking Neural Networks for Real-Time Pedestrian Street-Crossing Detection Using Dynamic Vision Sensors in Simulated Adverse Weather Conditions. Electronics 2024, 13, 4280. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Jia, X., Li, Q., Yang, X., Yao, M., Yan, J. (2025). Raw2Drive: Reinforcement Learning with Aligned World Models for End-to-End Autonomous Driving (in CARLA v2).

- Uppuluri, B., Patel, A., Mehta, N., Kamath, S., Chakraborty, P. (2025). CuRLA: Curriculum Learning Based Deep Reinforcement Learning For Autonomous Driving.

- Surmann, H., de Heuvel, J., Bennewitz, M. (2025). Multi-Objective Reinforcement Learning for Adaptive Personalized Autonomous Driving.

- Bertsekas, D. P. (2024). Model Predictive Control and Reinforcement Learning: A Unified Framework Based on Dynamic Programming.

- Vu, T. M., Moezzi, R., Cyrus, J., Hlava, J. (2021). Model Predictive Control for Autonomous Driving Vehicles.

- Liang, X., Wang, T., Yang, L., & Xing, E. (2018). Cirl: Controllable imitative reinforcement learning for vision-based self-driving. In Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV) (pp. 584-599).

- Chekroun, R., Toromanoff, M., Hornauer, S., & Moutarde, F. (2023). Gri: General reinforced imitation and its application to vision-based autonomous driving. Robotics, 12(5), 127.

- Phan-Minh, T., Howington, F., Chu, T. S., Lee, S. U., Tomov, M. S., Li, N., ... & Wolff, E. M. (2022). Driving in real life with inverse reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.03004.

- Ho, J., & Ermon, S. (2016). Generative adversarial IL. Advances in neural information processing systems, 29.

- Han, Y., & Yilmaz, A. (2022, August). Learning to drive using sparse imitation reinforcement learning. In 2022 26th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR) (pp. 3736-3742). IEEE.

- Reddy, S., Dragan, A. D., & Levine, S. (2019). Sqil: IL via reinforcement learning with sparse rewards. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.11108.

- Kiran, B. R., Sobh, I., Talpaert, V., Mannion, P., Al Sallab, A. A., Yogamani, S., & Pérez, P. (2021). Deep reinforcement learning for autonomous driving: A survey. IEEE transactions on intelligent transportation systems, 23(6), 4909-4926.

- Zhu, Z., & Zhao, H. (2021). A survey of deep RL and IL for autonomous driving policy learning. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 23(9), 14043-14065.

- Dosovitskiy, A., Ros, G., Codevilla, F., López, A., & Koltun, V. (2017). CARLA: An open urban driving simulator. arXiv preprint arXiv:1711.03938.

- Codevilla, F., Müller, M., López, A., Koltun, V., & Dosovitskiy, A. (2017). End-to-end driving via conditional imitation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA) (pp. 4693–4700). Singapore, Singapore.

- Pérez-Gil, Ó., Barea, R., López-Guillén, E., Bergasa, L. M., Gómez-Huélamo, C., Gutiérrez, R., & Díaz-Díaz, A. (2022). Deep reinforcement learning based control for autonomous vehicles in CARLA. Electronics, 11(7), 1035. [CrossRef]

- Nehme, G., & Deo, T. Y. (2023). Safe navigation: Training autonomous vehicles using deep reinforcement learning in CARLA. Sensors, 23(18), 7611. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Jia, X., Wang, S., & Yan, J. (2024). Think2Drive: Efficient reinforcement learning by thinking with latent world model for autonomous driving (in CARLA-V2). IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles, Early Access. [CrossRef]

- Sakhai, M.; Sithu, K.; Soe Oke, M.K.; Wielgosz, M. Cyberattack Resilience of Autonomous Vehicle Sensor Systems: Evaluating RGB vs. Dynamic Vision Sensors in CARLA. Applied Sciences 2025, 15(13), 7493. [CrossRef]

- Aranceta-Bartrina, Javier. 1999a. Title of the cited article. Journal Title 6: 100–10.

- Aranceta-Bartrina, Javier. 1999b. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed. Edited by Editor 1 and Editor 2. Publication place: Publisher, vol. 3, pp. 54–96.

- Baranwal, Ajay K., and Costea Munteanu. 1955. Book Title. Publication place: Publisher, pp. 154–96. First published 1921 (op-tional).

- Berry, Evan, and Amy M. Smith. 1999. Title of Thesis. Level of Thesis, Degree-Granting University, City, Country. Identifi-cation information (if available).

- Cojocaru, Ludmila, Dragos Constatin Sanda, and Eun Kyeong Yun. 1999. Title of Unpublished Work. Journal Title, phrase indicating stage of publication.

- Driver, John P., Steffen Rohrs, and Sean Meighoo. 2000. Title of Presentation. In Title of the Collected Work (if available). Paper presented at Name of the Conference, Location of Conference, Date of Conference.

- Harwood, John. 2008. Title of the cited article. Available online: URL (accessed on Day Month Year).

- Azikiwe, H. and Bello, A. (2020a). Title of the cited article. Journal Title, Volume(Issue), Firstpage–Lastpage or Article Number.

- Azikiwe, H. and Bello, A. (2020b). Book title. Publisher Name.

- Davison, T. E. (2019). Title of the book chapter. In A. A. Editor (Ed.), Title of the book: Subtitle (pp. Firstpage–Lastpage). Publisher Name. (Original work published 1623) (Optional).

- Fistek, A., Jester, E., & Sonnenberg, K. (2017, Month Day). Title of contribution [Type of contribution]. Conference Name, Conference City, Conference Country.

- Hutcheson, V. H. (2012). Title of the thesis [XX Thesis, Name of Institution Awarding the Degree].

- Lippincott, T., & Poindexter, E. K. (2019). Title of the unpublished manuscript [Unpublished manuscript/Manuscript in prepara-tion/Manuscript submitted for publication]. Department Name, Institution Name.

- Toromanoff, M., Wirbel, E., Moutarde, F. (2020). End-to-end Model-free Reinforcement Learning for Urban Driving Using Implicit Affordances. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.09445.

- Wang, Y., Chitta, K., Liu, H., Chernova, S., Schmid, C. (2021). InterFuser: Safety-Enhanced Autonomous Driving Using Interpretable Sensor Fusion Transformer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.05499.

- Chen, Y., Li, H., Wang, Y., Tomizuka, M. (2021). Learning Safe Multi-Vehicle Cooperation with Policy Optimization in CARLA. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 6(2), 3568-3575.

- Huang, Y., Xu, X., Yan, Y., Liu, Z. (2022). Transfer Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving under Diverse Weather Conditions. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles, 7(3), 593-603.

- Chen, J., Peng, Y., Wang, X. (2023). Reinforcement Learning-Based Motion Planning for Autonomous Vehicles at Unsignalized Intersections. Transportation Research Part C, 158, 104945.

- Zeng, R., Luo, J., Wang, J. (2024). Benchmarking Autonomous Driving Systems in Simulated Dynamic Traffic Environments. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 25(1), 121-132.

- Liu, Y., Zhang, Q., Zhao, L. (2025). Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning for Cooperative Autonomous Vehicles in CARLA. Journal of Intelligent Transportation Systems, 29(2), 198-212.

- Jia, Z., Yang, Y., Zhang, S. (2020). Towards Realistic End-to-End Autonomous Driving with Model-Based Reinforcement Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2006.06713.

- Cui, X., Yu, H., Zhao, J. (2023). Adaptive Curriculum Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving in Complex Scenarios. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 72(8), 9874-9886.

- Yang, Z., Liu, J., Wu, H. (2021). Safe Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Vehicles with Uncertainty-Aware Collision Avoidance. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, 6(3), 6312-6319.

- Fang, Y., Yan, J., Luo, H. (2022). Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning Framework for Urban Autonomous Driving in CARLA. Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 158, 104212.

- Jiang, X., Zhao, H., Zeng, Y. (2025). Benchmarking Reinforcement Learning Algorithms in CARLA: Performance, Stability, and Robustness Analysis. Transportation Research Record, 2025(1), 247-258.

- Cheng, Y., Wu, J., Wang, Z. (2023). End-to-End Urban Autonomous Driving with Deep Reinforcement Learning and Curriculum Strategies. Applied Sciences, 13(9), 5432.

- Huang, X., Chen, H., Zhao, L. (2024). Hybrid Imitation and Reinforcement Learning for Safe Autonomous Driving in CARLA. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, Early Access.

- Feng, R., Xu, L., Luo, X. (2025). Generalization of Reinforcement Learning Policies in Autonomous Driving: A Domain Randomization Approach. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, Early Access.

- Li, Z., Zhang, S., Zhou, D. (2022). Behavioral Cloning and Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Driving: A Comparative Study. IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine, 14(4), 27-41.

- Luo, Y., Wang, Z., Zhang, X. (2023). Improving Imitation Learning for Autonomous Driving through Adaptive Data Augmentation. Sensors, 23(11), 4981.

- Mohanty, A., Lee, J., Patel, R. (2024). Inverse Reinforcement Learning for Human-Like Autonomous Driving Behavior in CARLA. IEEE Transactions on Human-Machine Systems, Early Access.

- Kim, J., Cho, S. (2025). Reinforcement and Imitation Learning Fusion for Autonomous Vehicle Safety Enhancement. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles, Early Access.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).