Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

14 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Definition of Outcomes

Follow-Up

Statistical Analyses

3. Results

Study Population Characteristics

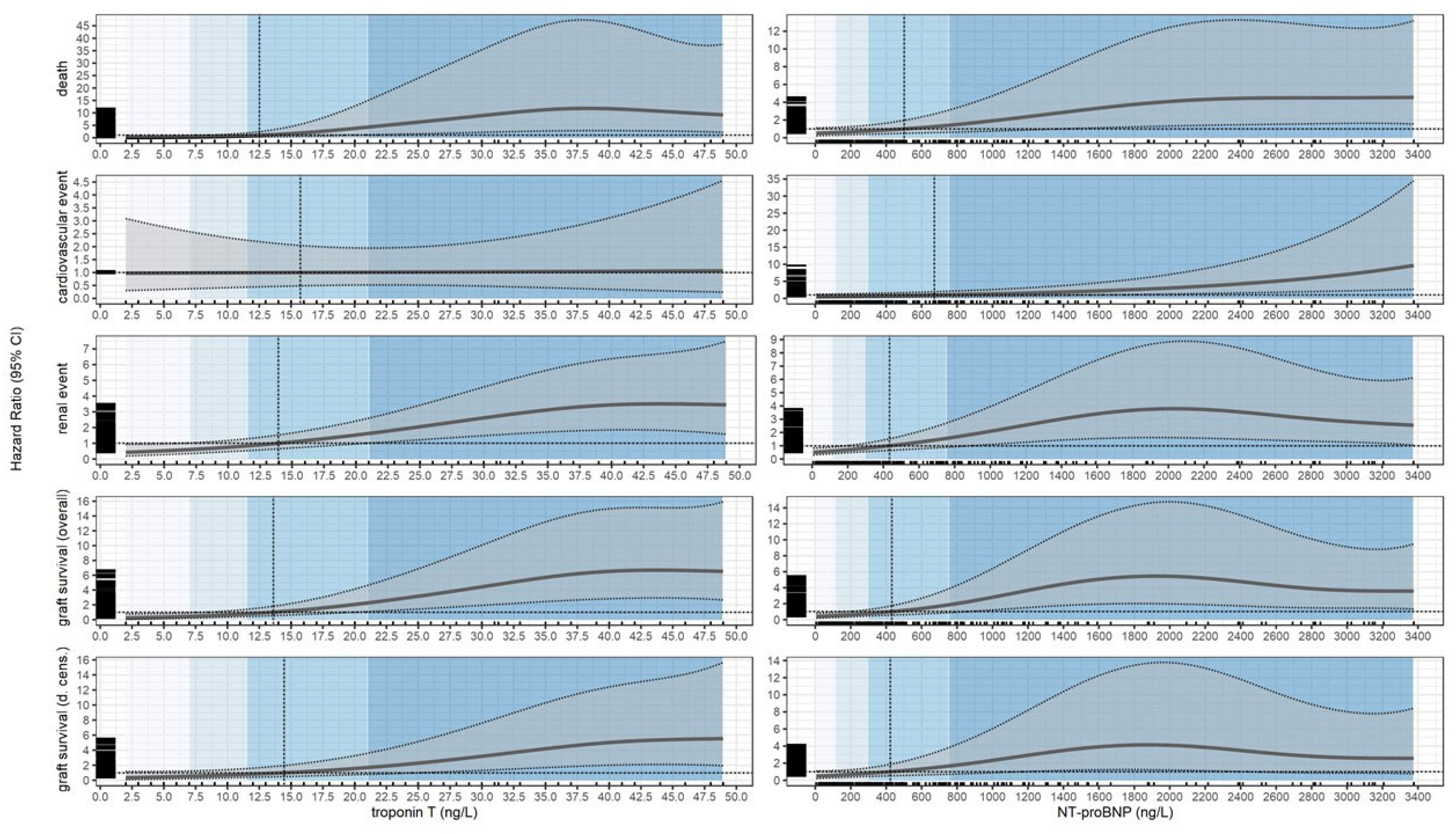

Death

Cardiovascular Events

Renal Events

Graft Loss

Graft Loss or Death

Summary of Cox Models

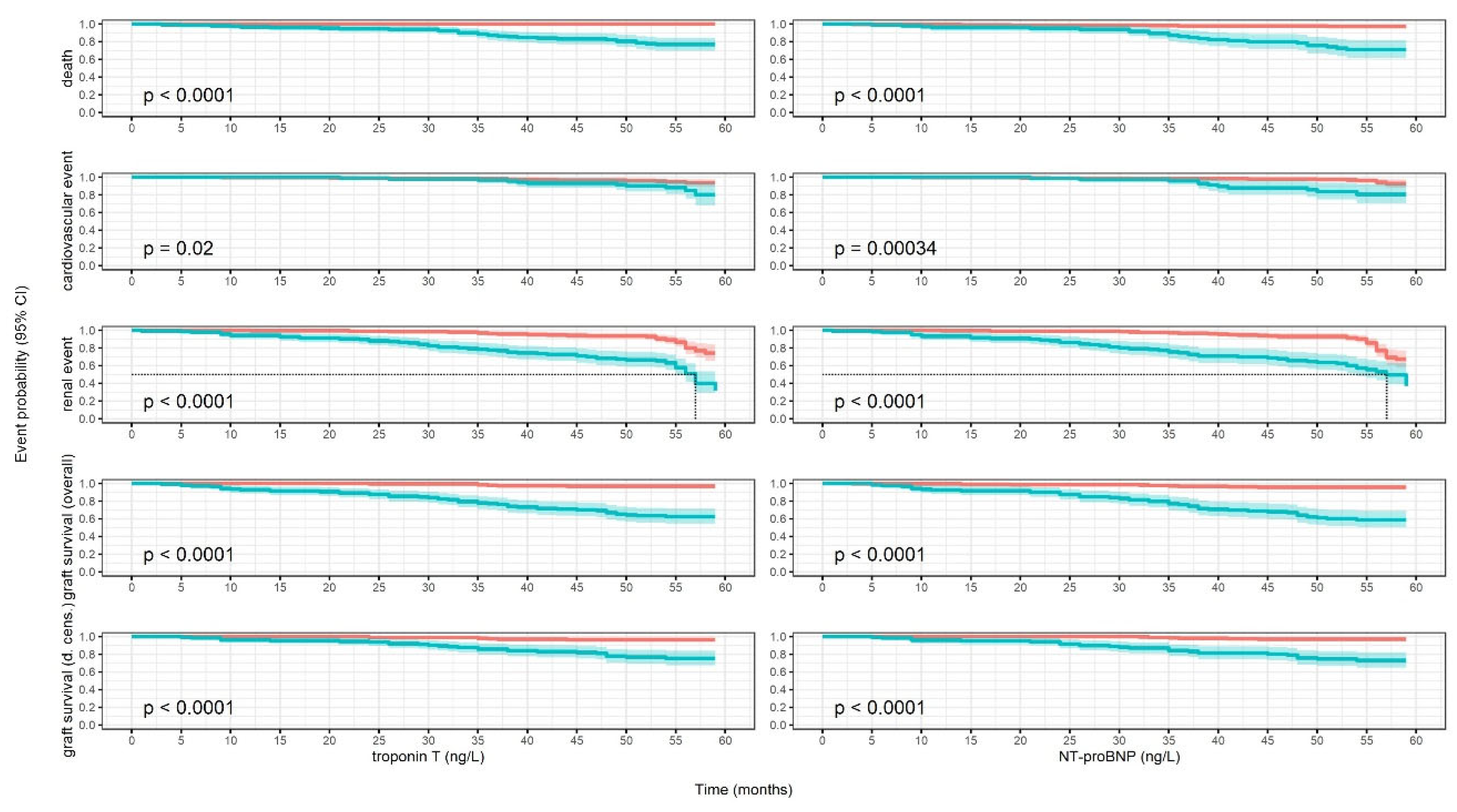

Kaplan-Meier Models

4. Discussion

Limitations

Pro

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| RTRs | Renal transplant recipients |

| cTnT | Cardiac Troponin T |

| NTproBNP | N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide |

| cTnI | Cardiac Troponin I |

| CVD | Cardio-vascular disease |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| BNP | B-type natriuretic peptide |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| HF | Heart failure |

| NPs | Natriuretic peptides |

References

- Knoll G. Trends in kidney transplantation over the past decade. Drugs. 2008; 6(suppl 1): 3-10.

- Kabani R, Quinn RR, Palmer S, et al. Risk of death following kidney allograft failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2014; 29: 1778-1786.

- Mayrdorfer M, Liefeldt L, Wu K, et al. Exploring the Complexity of Death-Censored Kidney Allograft Failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021; 32: 1513-1526.

- Mayrdorfer M, Liefeldt L, Osmanodja B, et al. A single centre in-depth analysis of death with a functioning kidney graft and reasons for overall graft failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2023; 38:1857-1866.

- Wolfe RA, Ashby VB, Milford EL, et al. Comparison of mortality in all patients on dialysis, patients on dialysis awaiting transplantation, and recipients of a first cadaveric transplant. N Engl J Med. 1999; 341: 1725-1730.

- Stoumpos S, Jardine AG, Mark PB. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality after kidney transplantation. Transpl Int. 2015; 28: 10–21.

- Heleniak Z, Illersperger S, Brakemeier S, et al. Obesity, Fat Tissue Parameters, and Arterial Stiffness in Renal Transplant Recipients. Transplant Proc. 2020; 52: 2341-2346.

- Heleniak Z, Illersperger S, Małgorzewicz S, et al. Arterial Stiffness as a Cardiovascular Risk Factor After Successful Kidney Transplantation in Diabetic and Nondiabetic Patients. Transplant Proc. 2022; 54: 2205-2211.

- Liefeldt L, Budde K. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in renal transplant recipients and strategies to minimize risk. Transpl Int. 2010; 23: 1191-1204.

- van der Linden N, Klinkenberg LJJ, Bekers O, et al. Prognostic value of basal high-sensitive cardiac troponin levels on mortality in the general population: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95: e5703.

- York MK, Gupta DK, Reynolds CF, et al. Natriuretic Peptide Levels and Mortality in Patients With and Without Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018; 71: 2079-2088.

- Rehman SU, Mueller T, Januzzi JL. Characteristics of the novel interleukin family biomarker ST2 in patients with acute heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008; 52: 1458-1465.

- Jarolim P. High sensitivity cardiac troponin assays in the clinical laboratories. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015; 53: 635-652.

- Apple FS, Murakami MM, Pearce LA, Herzog CA. Predictive value of cardiac troponin I and T for subsequent death in end-stage renal disease. Circulation. 2002; 106: 2941-2945.

- Pfortmueller CA, Funk GC, Marti G, et al. Diagnostic performance of high-sensitive troponin T in patients with renal insufficiency. Am J Cardiol. 2013; 112: 1968-1972.

- Saunders JT, Nambi V, de Lemos JA, et al. Cardiac troponin T measured by a highly sensitive assay predicts coronary heart disease, heart failure, and mortality in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Circulation. 2011; 123: 1367-1376.

- Jarolim P, Claggett BL, Conrad MJ, et al. B-Type Natriuretic Peptide and Cardiac Troponin I Are Associated With Adverse Outcomes in Stable Kidney Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2017; 101: 182-190.

- Keddis MT, El-Zoghby ZM, El Ters M, et al. Cardiac troponin T before and after kidney transplantation: determinants and implications for posttransplant survival. Am J Transplant. 2013; 13: 406-414.

- Heleniak Z, Illersperger S, Brakemeier S, et al. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade and arterial stiffness in renal transplant recipients - a cross-sectional prospective observational clinical study. Acta Biochim Pol. 2020; 67: 613-622.

- Schmidt D, Osmanodja B, Pfefferkorn M, et al. TBase - an Integrated Electronic Health Record and Research Database for Kidney Transplant Recipients. J Vis Exp. 2021; 13: 170.

- Wilcox, R. Trimming and Winsorization. In: Armitage P, Colton T, eds. Encyclopedia of Biostatistics. John Wiley and Sons, Chichester, UK; 2005: 5531–5533.

- Firth C, Shamoun F, Cha S, et al. Cardiac Troponin T Risk Stratification Model Predicts All-Cause Mortality Following Kidney Transplant. Am J Nephrol. 2018; 48: 242-250.

- Hickson LJ, Cosio FG, El-Zoghby ZM, et al. Survival of patients on the kidney transplant wait list: relationship to cardiac troponin T. Am J Transplant. 2008; 8: 2352-2359.

- Connolly GM, Cunningham R, McNamee PT, et al. Troponin T is an independent predictor of mortality in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008; 23: 1019-1025.

- Abbas NA, John RI, Webb MC, et al. Cardiac troponins and renal function in nondialysis patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Chem. 2005; 51: 2059-2066.

- Hassan HC, Howlin K, Jefferys A, et al. High-sensitivity troponin as a predictor of cardiac events and mortality in the stable dialysis population. Clin Chem. 2014 ; 60: 389-398.

- Meier-Kriesche HU, Baliga R, Kaplan B. Decreased renal function is a strong risk factor for cardiovascular death after renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2003; 27: 1291-1295.

- Cosio FG, Hickson LJ, Griffin MD, et al. Patient survival and cardiovascular risk after kidney transplantation: the challenge of diabetes. Am J Transplant. 2008; 8: 593-599.

- Adamo M, Gardner RS, McDonagh TA, Metra M. The ‘Ten Commandments’ of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2022; 43: 440-441.

- Pieske B, Tschöpe C, de Boer RA, et al. How to diagnose heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the HFA-PEFF diagnostic algorithm: a consensus recommendation from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur J Heart Fail. 2020; 22: 391-412.

- Han X, Zhang S, Chen Z, et al. Cardiac biomarkers of heart failure in chronic kidney disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2020; 510: 298-310.

- Wei TM, Jin L, Lv LC, et al. Changes in plasma B-type natriuretic peptide after allograft renal transplantation. Nephrology (Carlton). 2007; 12: 102-106.

- Bodlaj G, Hubmann R, Saleh K, et al. Serum levels of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide are associated with allograft function in recipients of renal transplants. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2009. 121: 631-637.

- Emrich IE, Scheuer AL, Rogacev KS, et al. Plasma biomarkers outperform echocardiographic measurements for cardiovascular risk prediction in kidney transplant recipients: results of the HOME ALONE study. Clin Kidney J. 2021; 15: 693-702.

- Kwon HM, Moon YJ, Kim KS, et al. Prognostic Value of B Type Natriuretic Peptide in Liver Transplant Patients: Implication in Posttransplant Mortality. Hepatology. 2021; 74: 336-350.

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 342a | [0,7], N = 108a | (7, 11.5], N = 63a | (11.5, 21], N = 86a | (21, 48.9], N = 85a | p-valueb |

| Age (years) | 53 (14) | 45 (12) | 51 (14) | 55 (13) | 62 (11) | <0.001 |

| Sex | <0.001 | |||||

| Female | 129/342 (38%) | 59/108 (55%) | 22/63 (35%) | 28/86 (33%) | 20 / 85 (24%) | |

| Male | 213/342 (62%) | 49/108 (45%) | 41/63 (65%) | 58/86 (67%) | 65/85 (76%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.6 (4.8) | 25.0 (4.7) | 25.9 (5.0) | 25.4 (4.6) | 26.4 (4.8) | 0.086 |

| Total weight (kg) | 76 (17) | 73 (17) | 77 (16) | 76 (17) | 81 (16) | 0.010 |

| DM type 2 (yes) | 45/342 (13%) | 7/108 (6.5%) | 10/63 (16%) | 10/86 (12%) | 18/85 (21%) | 0.023 |

| NODAT (yes) | 21/342 (6.1%) | 7/108 (6.5%) | 3/63 (4.8%) | 6/86 (7.0%) | 5/85 (5.9%) | >0.9 |

| CAD (yes) | 77/342 (23%) | 2/108 (1.9%) | 9/63 (14%) | 16/86 (19%) | 50/85 (59%) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure (yes) | 90/342 (26%) | 19/108 (18%) | 11/63 (17%) | 26/86 (30%) | 34/85 (40%) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension (yes) | 296/342 (87%) | 92/108 (85%) | 53/63 (84%) | 76/86 (88%) | 75/85 (88%) | 0.8 |

| Glomerulonephritis (yes) | 185/342 (54%) | 67/108 (62%) | 31/63 (49%) | 50/86 (58%) | 37/85 (44%) | 0.052 |

| Polycystic kidney disease (yes) | 55/342 (16%) | 12/108 (11%) | 11/63 (17%) | 14/86 (16%) | 18/85 (21%) | 0.3 |

| Tubulointerstitial nephritis (yes) | 69/342 (20%) | 27/108 (25%) | 12/63 (19%) | 12/86 (14%) | 18/85 (21%) | 0.3 |

| Hypertensive nephropathy (yes) | 18/342 (5.3%) | 1/108 (0.9%) | 2/63 (3.2%) | 6/86 (7.0%) | 9/85 (11%) | 0.013 |

| Unknown etiology (yes) | 10/342 (2.9%) | 1/108 (0.9%) | 7/63 (11%) | 2/86 (2.3%) | 0/85 (0%) | <0.001 |

| Time of RRT (months) | 59 (61) | 36 (53) | 67 (76) | 74 (60) | 68 (51) | <0.001 |

| Time post KTx (months) | 93 (80) | 100 (78) | 79 (83) | 89 (77) | 98 (81) | 0.13 |

| Preemptive KTX (yes) n(%) | 47/342 (14%) | 27/108 (25%) | 9/63 (14%) | 4/86 (4.7%) | 7/85 (8.2%) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.67 (0.81) | 1.29 (0.37) | 1.51 (0.51) | 1.69 (0.76) | 2.27 (1.06) | <0.001 |

| eGFR CKDEPI (mL/min/1.73m2) | 50 (20) | 62 (17) | 54 (18) | 48 (18) | 35 (17) | <0.001 |

| NT pro BNP (ng/L) | 684 (934) | 231 (357) | 411 (661) | 673 (816) | 1,473 (1,196) | <0.001 |

| Cyclosporine (yes) | 72/342 (21%) | 24/108 (22%) | 11/63 (17%) | 17/86 (20%) | 20/85 (24%) | 0.8 |

| Tacrolimus (yes) | 212/342 (62%) | 75/108 (69%) | 43/63 (68%) | 57/86 (66%) | 37/85 (44%) | <0.001 |

| Steroids (yes) | 176/342 (51%) | 38/108 (35%) | 37/63 (59%) | 45/86 (52%) | 56/85 (66%) | <0.001 |

| MMF (yes) | 150/342 (44%) | 45/108 (42%) | 23/63 (37%) | 44/86 (51%) | 38/85 (45%) | 0.3 |

| MPS (yes) | 170/342 (50%) | 59/108 (55%) | 35/63 (56%) | 40/86 (47%) | 36/85 (42%) | 0.3 |

| Betalacept (yes) | 41/342 (12%) | 8/108 (7.4%) | 6/63 (9.5%) | 9/86 (10%) | 18/85 (21%) | 0.023 |

| Calcium channel blocker (yes) | 157/342 (46%) | 37/108 (34%) | 29/63 (46%) | 48/86 (56%) | 43/85 (51%) | 0.018 |

| ACE inhibitor (yes) | 89/342 (26%) | 25/108 (23%) | 16/63 (25%) | 27/86 (31%) | 21/85 (25%) | 0.6 |

| Statines (yes) | 142/342 (42%) | 34/108 (31%) | 22/63 (35%) | 44/86 (51%) | 42/85 (49%) | 0.011 |

| AT1-R antagonists (yes) | 111/342 (32%) | 28/108 (26%) | 17/63 (27%) | 31/86 (36%) | 35/85 (41%) | 0.093 |

| aMean (SD); n/N (%). | ||||||

|

bOne-way ANOVA; Pearson’s Chi-squared test; Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test; Fisher’s exact test. SI conversion factor: for creatinine to convert mg/dL to µmol/L, multiply by 88.42 Abbreviations: BMI—body mass index, DM—diabetes mellitus, NODAT—new onset diabetes after transplantation, CAD—coronary artery disease, RRT—renal replacement therapy, Ktx—kidney transplantation, eGFR—estimated glomerular filtration rate, NT-proBNP—N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, ACE—angiotensin converting enzyme, AT1-R—angiotensin receptor 1. | ||||||

| Characteristic | Overall, N = 342a | [0, 113], N = 87a | (113, 298], N = 84a | (298, 754], N = 85a | (754, 3376], N = 86a | p-valueb |

| Age | 53 (14) | 46 (12) | 50 (13) | 56 (13) | 58 (14) | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.008 | |||||

| Female | 129/342 (38%) | 20/87 (23%) | 33/84 (39%) | 40/85 (47%) | 36/86 (42%) | |

| Male | 213/342 (62%) | 67/87 (77%) | 51/84 (61%) | 45/85 (53%) | 50/86 (58%) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.6 (4.8) | 25.8 (4.2) | 25.9 (5.0) | 25.1 (4.7) | 25.6 (5.3) | 0.6 |

| Total weight (kg) | 76 (17) | 79 (16) | 77 (17) | 74 (16) | 75 (18) | 0.2 |

| DM type 2 (yes) | 45/342 (13%) | 11/87 (13%) | 9/84 (11%) | 9/85 (11%) | 16/86 (19%) | 0.4 |

| NODAT (yes) | 21/342 (6.1%) | 8/87 (9.2%) | 5/84 (6.0%) | 3/85 (3.5%) | 5/86 (5.8%) | 0.5 |

| CAD (yes) | 77/342 (23%) | 3/87 (3.4%) | 9/84 (11%) | 22/85 (26%) | 43/86 (50%) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure (yes) | 90/342 (26%) | 17/87 (20%) | 12/84 (14%) | 26/85 (31%) | 35/86 (41%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension (yes) | 296/342 (87%) | 78/87 (90%) | 69/84 (82%) | 71/85 (84%) | 78/86 (91%) | 0.3 |

| Glomrulonephritis (yes) | 185/342 (54%) | 48/87 (55%) | 55/84 (65%) | 36/85 (42%) | 46/86 (53%) | 0.027 |

| Polycystic kidney disease (yes) | 55/342 (16%) | 11/87 (13%) | 14/84 (17%) | 20/85 (24%) | 10/86 (12%) | 0.14 |

| Tubulointerstitial nephritis (yes) | 69/342 (20%) | 23/87 (26%) | 10/84 (12%) | 17/85 (20%) | 19/86 (22%) | 0.12 |

| Hypertensive nephropathy (yes) | 18/342 (5.3%) | 2/87 (2.3%) | 2/84 (2.4%) | 7/85 (8.2%) | 7/86 (8.1%) | 0.12 |

| Unknown etiology (yes) | 10/342 (2.9%) | 1/87 (1.1%) | 3/84 (3.6%) | 6/85 (7.1%) | 0/86 (0%) | 0.020 |

| Time of RRT (months) | 59 (61) | 46 (69) | 59 (64) | 62 (54) | 71 (52) | <0.001 |

| Time post KTx (months) | 93 (80) | 97 (85) | 86 (77) | 84 (73) | 103 (82) | 0.4 |

| Preempitve KTX (yes) | 47/342 (14%) | 23/87 (26%) | 12/84 (14%) | 8/85 (9.4%) | 4/86 (4.7%) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.67 (0.81) | 1.38 (0.38) | 1.40 (0.44) | 1.60 (0.63) | 2.31 (1.14) | <0.001 |

| eGFR CKDEPI (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 50 (20) | 61 (16) | 57 (17) | 48 (19) | 34 (16) | <0.001 |

| Troponin T (ng/L) | 16 (13) | 8 (5) | 12 (10) | 17 (12) | 27 (14) | <0.001 |

| Cyclosporine (yes) | 72/342 (21%) | 15/87 (17%) | 17/84 (20%) | 18/85 (21%) | 22/86 (26%) | 0.6 |

| Tacrolimus (yes) | 212/342 (62%) | 61/87 (70%) | 53/84 (63%) | 54/85 (64%) | 44/86 (51%) | 0.077 |

| Steroids (yes) | 176/342 (51%) | 31/87 (36%) | 40/84 (48%) | 49/85 (58%) | 56/86 (65%) | <0.001 |

| MMF (yes) | 150/342 (44%) | 44/87 (51%) | 33/84 (39%) | 34/85 (40%) | 39/86 (45%) | 0.4 |

| MPS (yes) | 170/342 (50%) | 40/87 (46%) | 45/84 (54%) | 47/85 (55%) | 38/86 (44%) | 0.4 |

| Betalacept (yes) | 41/342 (12%) | 8/87 (9.2%) | 10/84 (12%) | 9/85 (11%) | 14/86 (16%) | 0.5 |

| Calcium channel blocker (yes) | 157/342 (46%) | 38/87 (44%) | 38/84 (45%) | 33/85 (39%) | 48/86 (56%) | 0.2 |

| ACE inhibitor (yes) | 89/342 (26%) | 19/87 (22%) | 21/84 (25%) | 24/85 (28%) | 25/86 (29%) | 0.7 |

| Statines (yes) | 142/342 (42%) | 35/87 (40%) | 35/84 (42%) | 29/85 (34%) | 43/86 (50%) | 0.2 |

| AT1-R antagonists (yes) | 111/342 (32%) | 23/87 (26%) | 24/84 (29%) | 32/85 (38%) | 32/86 (37%) | 0.3 |

| aMean (SD); n/N (%). | ||||||

|

bOne-way ANOVA; Pearson’s Chi-squared test; Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test; Fisher’s exact test. SI conversion factor: for creatinine to convert mg/dL to µmol/L, multiply by 88.42 Abbreviations: BMI—body mass index, DM—diabetes mellitus, NODAT—new onset diabetes after transplantation, CAD—coronary artery disease, RRT—renal replacement therapy, Ktx—kidney transplantation, eGFR—estimated glomerular filtration rate, NT-proBNP—N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide, ACE—angiotensin converting enzyme, AT1-R—angiotensin receptor 1. | ||||||

| Substance | Event | Quartile | Estimate 1 | p-value | Cutoff | Estimate 2 | p-value |

| Overall HR | |||||||

| Troponin T (ng/L) | Death | 7.00 | 0.29 (0.10; 0.87) | 0.026 | 12.53 | 1.00 (0.42; 2.38) | >0.9 |

| 11.50 | 0.80 (0.35; 1.85) | 0.6 | |||||

| 21.00 | 4.25 (1.22; 14.78) | 0.023 | |||||

| 48.95 | 9.20 (2.26; 37.52) | 0.002 | |||||

| Conditional HR | |||||||

| Troponin T (ng/L) | Death | [2.00, 7.00) | 0.17 (0.04; 0.78) | 0.022 | [2.00, 12.53) | 0.31 (0.09; 1.03) | 0.055 |

| [7.00, 11.50) | 0.49 (0.20; 1.20) | 0.11 | |||||

| [11.50, 21.00) | 2.01 (0.71; 5.75) | 0.2 | [12.53, 48.95] | 6.55 (1.80; 23.81) | 0.004 | ||

| [21.00, 48.95] | 9.03 (2.34; 35.16) | 0.001 | |||||

| Overall HR | |||||||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | Death | 113.00 | 0.59 (0.30; 1.15) | 0.12 | 501.89 | 1.00 (0.51; 1.94) | >0.9 |

| 298.50 | 0.76 (0.41; 1.40) | 0.4 | |||||

| 753.50 | 1.41 (0.64; 3.10) | 0.4 | |||||

| 3376.05 | 4.54 (1.57; 13.16) | 0.005 | |||||

| Conditional HR | |||||||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | Death | [6.00, 113.00) | 0.54 (0.26; 1.12) | 0.10 | [6.00, 501.89) | 0.71 (0.37; 1.36) | 0.3 |

| [113.00, 298.50) | 0.66 (0.35; 1.26) | 0.2 | |||||

| [298.50, 753.50) | 1.03 (0.52; 2.03) | >0.9 | [501.89, 3376.05] | 3.16 (1.16; 8.58) | 0.024 | ||

| [753.50, 3376.05] | 3.49 (1.25; 9.78) | 0.017 | |||||

| Overall HR | |||||||

| Troponin T (ng/L) | Cardiovascular event | 7.00 | 0.98 (0.37; 2.58) | >0.9 | 15.72 | 1.00 (0.49; 2.04) | >0.9 |

| 11.50 | 0.99 (0.44; 2.25) | >0.9 | |||||

| 21.00 | 1.01 (0.53; 1.94) | >0.9 | |||||

| 48.95 | 1.07 (0.25; 4.55) | >0.9 | |||||

| Conditional HR | |||||||

| Troponin T (ng/L) | Cardiovascular event | [2.00, 7.00) | 0.98 (0.34; 2.80) | >0.9 | [2.00, 15.72) | 0.99 (0.40; 2.46) | >0.9 |

| [7.00, 11.50) | 0.99 (0.41; 2.39) | >0.9 | |||||

| [11.50, 21.00) | 1.00 (0.49; 2.03) | >0.9 | [15.72, 48.95] | 1.03 (0.42; 2.56) | |||

| [21.00, 48.95] | 1.04 (0.40; 2.69) | >0.9 | |||||

| Overall HR | |||||||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | Cardiovascular event | 113.00 | 0.63 (0.31; 1.27) | 0.2 | 670.56 | 1.00 (0.52; 1.91) | >0.9 |

| 298.50 | 0.73 (0.37; 1.44) | 0.4 | |||||

| 753.50 | 1.07 (0.56; 2.04) | 0.8 | |||||

| 3376.05 | 9.65 (2.70; 34.49) | <0.001 | |||||

| Conditional HR | |||||||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | Cardiovascular event | [6.00, 113.00) | 0.60 (0.29; 1.22) | 0.2 | [6.00, 670.56) | 0.76 (0.39; 1.49) | 0.4 |

| [113.00, 298.50) | 0.68 (0.34; 1.35) | 0.3 | |||||

| [298.50, 753.50) | 0.89 (0.46; 1.70) | 0.7 | [670.56, 3376.05] | 3.10 (1.30; 7.46) | 0.011 | ||

| [753.50, 3376.05] | 3.22 (1.34; 7.77) | 0.009 | |||||

| Overall HR | |||||||

| Troponin T (ng/L) | Renal event | 7.00 | 0.60 (0.36; 1.01) | 0.056 | 13.94 | 1.00 (0.66; 1.52) | >0.9 |

| 11.50 | 0.83 (0.54; 1.28) | 0.4 | |||||

| 21.00 | 1.62 (1.02; 2.58) | 0.042 | |||||

| 48.95 | 3.45 (1.59; 7.48) | 0.002 | |||||

| Conditional HR | |||||||

| Troponin T (ng/L) | Renal event | [2.00, 7.00) | 0.51 (0.27; 0.95) | 0.036 | [2.00, 13.94) | 0.64 (0.38; 1.09) | 0.10 |

| [7.00, 11.50) | 0.70 (0.44; 1.13) | 0.14 | |||||

| [11.50, 21.00) | 1.17 (0.76; 1.80) | 0.5 | [13.94, 48.95] | 2.41 (1.38; 4.22) | 0.002 | ||

| [21.00, 48.95] | 2.83 (1.57; 5.10) | <0.001 | |||||

| Overall HR | |||||||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | Renal event | 113.00 | 0.60 (0.41; 0.90) | 0.011 | 434.42 | 1.00 (0.66; 1.51) | >0.9 |

| 298.50 | 0.82 (0.56; 1.18) | 0.3 | |||||

| 753.50 | 1.56 (0.90; 2.70) | 0.11 | |||||

| 3376.05 | 2.55 (1.06; 6.11) | 0.036 | |||||

| Conditional HR | |||||||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | Renal event | [6.00, 113.00) | 0.55 (0.36; 0.85) | 0.007 | [6.00, 434.42) | 0.71 (0.48; 1.05) | 0.088 |

| [113.00, 298.50) | 0.70 (0.49; 1.01) | 0.053 | |||||

| [298.50, 753.50) | 1.14 (0.72; 1.79) | 0.6 | [434.42, 3376.05] | 2.69 (1.28; 5.70) | 0.009 | ||

| [753.50, 3376.05] | 2.97 (1.36; 6.42) | 0.006 | |||||

| Overall HR | |||||||

| Troponin T (ng/L) | Graft survival (overall) | 7.00 | 0.44 (0.22; 0.89) | 0.021 | 13.61 | 1.00 (0.56; 1.79) | >0.9 |

| 11.50 | 0.77 (0.44; 1.37) | 0.4 | |||||

| 21.00 | 2.25 (1.11; 4.59) | 0.026 | |||||

| 48.95 | 6.52 (2.68; 15.89) | <0.001 | |||||

| Conditional HR | |||||||

| Troponin T (ng/L) | Graft survival (overall) | [2.00, 7.00) | 0.32 (0.13; 0.79) | 0.013 | [2.00, 13.61) | 0.49 (0.24; 1.01) | 0.052 |

| [7.00, 11.50) | 0.59 (0.32; 1.08) | 0.089 | |||||

| [11.50, 21.00) | 1.35 (0.73; 2.53) | 0.3 | [13.61, 48.95] | 3.86 (1.79; 8.41) | <0.001 | ||

| [21.00, 48.95] | 4.95 (2.20; 11.13) | <0.001 | |||||

| Overall HR | |||||||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | Graft survival (overall) | 113.00 | 0.51 (0.30; 0.89) | 0.015 | 431.05 | 1.00 (0.58; 1.72) | >0.9 |

| 298.50 | 0.76 (0.47; 1.24) | 0.3 | |||||

| 753.50 | 1.86 (0.89; 3.86) | 0.10 | |||||

| 3376.05 | 3.57 (1.35; 9.45) | 0.010 | |||||

| Conditional HR | |||||||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | Graft survival (overall) | [6.00, 113.00) | 0.46 (0.25; 0.84) | 0.012 | [6.00, 431.05) | 0.64 (0.38; 1.08) | 0.10 |

| [113.00, 298.50) | 0.63 (0.38; 1.02) | 0.060 | |||||

| [298.50, 753.50) | 1.20 (0.66; 2.18) | 0.6 | [431.05, 3376.05] | 3.60 (1.48; 8.85) | 0.005 | ||

| [753.50, 3376.05] | 4.06 (1.62; 10.28) | 0.003 | |||||

| Overall HR | |||||||

| Troponin T (ng/L) | Graft survival (d. cens.) | 7.00 | 0.53 (0.23; 1.21) | 0.13 | 14.45 | 1.00 (0.52; 1.94) | >0.9 |

| 11.50 | 0.78 (0.40; 1.53) | 0.5 | |||||

| 21.00 | 1.69 (0.80; 3.56) | 0.2 | |||||

| 48.95 | 5.53 (1.96; 15.62) | 0.001 | |||||

| Conditional HR | |||||||

| Troponin T (ng/L) | Graft survival (d. cens.) | [2.00, 7.00) | 0.43 (0.16; 1.16) | 0.094 | [2.00, 14.45) | 0.59 (0.26; 1.34) | 0.2 |

| [7.00, 11.50) | 0.64 (0.31; 1.35) | 0.2 | |||||

| [11.50, 21.00) | 1.15 (0.58; 2.29) | 0.7 | [14.45, 48.95] | 3.06 (1.31; 7.10) | 0.009 | ||

| [21.00, 48.95] | 3.74 (1.55; 9.03) | 0.003 | |||||

| Overall HR | |||||||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | Graft survival (d. cens.) | 113.00 | 0.59 (0.31; 1.11) | 0.11 | 424.30 | 1.00 (0.54; 1.85) | >0.9 |

| 298.50 | 0.81 (0.46; 1.43) | 0.5 | |||||

| 753.50 | 1.67 (0.73; 3.81) | 0.2 | |||||

| 3376.05 | 2.57 (0.78; 8.41) | 0.12 | |||||

| Conditional HR | |||||||

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | Graft survival (d. cens.) | [6.00, 113.00) | 0.53 (0.26; 1.07) | 0.080 | [6.00, 424.30) | 0.70 (0.38; 1.30) | 0.3 |

| [113.00, 298.50) | 0.69 (0.38; 1.23) | 0.2 | |||||

| [298.50, 753.50) | 1.17 (0.59; 2.32) | 0.6 | [424.30, 3376.05] | 2.80 (0.96; 8.25) | 0.060 | ||

| [753.50, 3376.05] | 3.10 (1.01; 9.49) | 0.048 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).