Submitted:

11 July 2025

Posted:

14 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The MLG-ULB Dataset: A Benchmark for Fraud Detection Research

1.2. Research Objectives

1.3. Contributions

2. Methodology

| Parameter | Details |

|---|---|

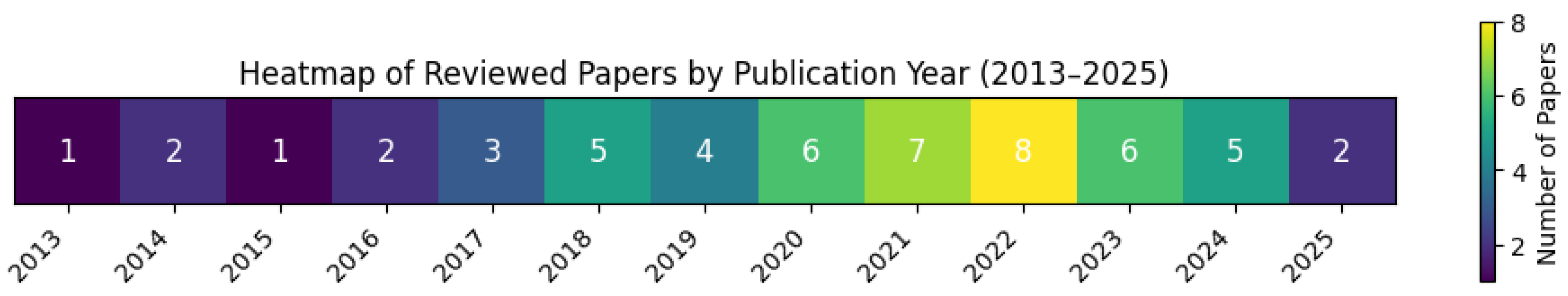

| Search Period | January 2013 – March 2025 |

| Databases Searched | IEEE Xplore, ACM, ScienceDirect, SpringerLink, arXiv |

| Initial Results | 1,847 studies identified |

| After Screening | 312 studies for full-text review |

| Final Inclusion | 52 studies meeting all criteria |

| Inter-rater Reliability | (screening), (full-text) |

| Quality Assessment | Modified CASP checklist (0–16 scale) |

| High Quality Studies | 44 studies (score ) |

| Med-Quality Studies | 8 studies (score 8–11) |

| Statistical Analysis | ANOVA with Tukey HSD, Cohen’s d |

| Primary Metrics | Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, AUC |

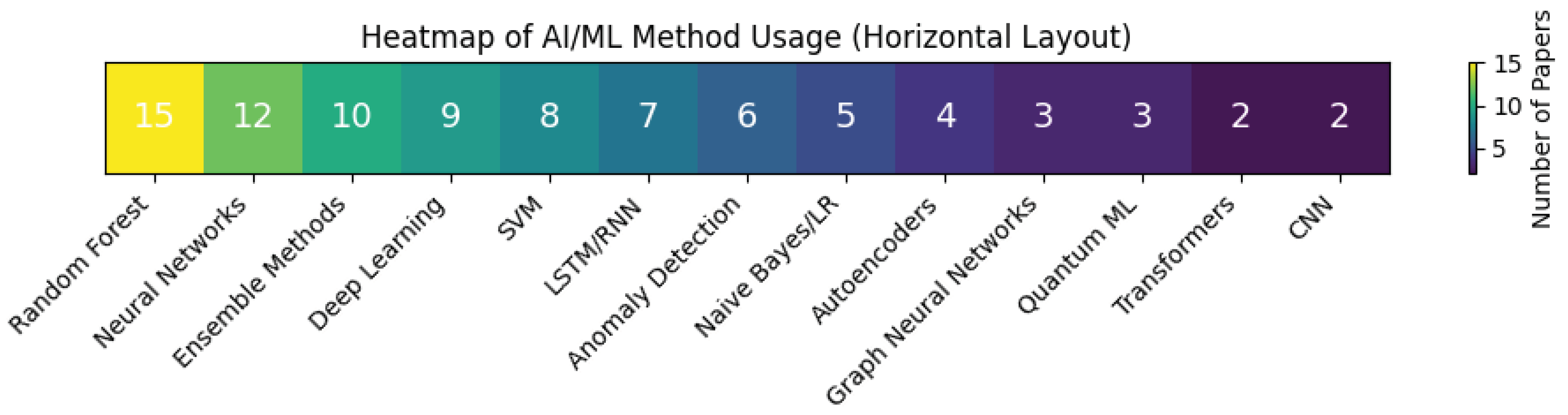

| Algorithm Categories | Traditional ML, Deep Learning, Ensemble, Anomaly Detection, Emerging |

3. Literature Review and Analysis

3.1. Traditional Machine Learning Approaches

3.1.1. Tree-Based Methods

3.1.2. Support Vector Machines

3.1.3. Probabilistic Methods

3.2. Deep Learning Approaches

3.2.1. Neural Networks

3.2.2. Recurrent Networks

3.2.3. Convolutional Networks

3.3. Ensemble Methods

3.3.1. Voting Classifiers

3.3.2. Boosting Techniques

3.4. Anomaly Detection Methods

3.4.1. Unsupervised Approaches

3.4.2. Autoencoders

3.5. Emerging Technologies

3.5.1. Quantum Machine Learning

3.5.2. Graph Neural Networks

3.5.3. Transformer Architectures

4. Comparative Performance Analysis

4.1. Algorithm Performance Ranking

4.2. Implementation Characteristics Analysis

4.3. Preprocessing Impact Analysis

4.4. Computational Complexity Assessment

5. Challenges and Limitations

5.1. Dataset-Specific Limitations

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA) transformation removes raw feature values, limiting domain-specific feature engineering.

- The dataset covers only two days of transactions, preventing analysis of long-term fraud evolution.

- It includes only European cardholders, reducing generalizability to global scenarios.

- Fraud represents only 0.172% of all transactions, which may not reflect real-world class imbalance in other contexts.

5.2. Methodological Challenges

- Delays in fraud verification make real-time deployment difficult [7].

- Many models do not handle concept drift, making them less effective over time.

- Some studies focus heavily on accuracy, neglecting metrics like precision and recall [8].

- Cross-validation strategies vary widely, affecting result comparability.

5.3. Implementation Challenges

- Real-time systems require response times under 100 milliseconds [27].

- Many models are not scalable to millions of transactions per day.

- Model interpretability is essential for audit and compliance in the financial sector.

- Reducing false positives is critical to avoid unnecessary customer disruptions and financial loss.

6. Future Research Directions

6.1. Immediate Opportunities

6.2. Advanced Methodological Directions

6.3. Emerging Technology Integration

7. Conclusions

Appendix A. Additional Relevant References

- [A1]

- S. Bhattacharyya, S. Jha, K. Tharakunnel, and J. C. Westland, “Data mining for credit card fraud: A comparative study,” Decision Support Systems, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 602–613, 2014.

- [A2]

- C. Whitrow, D. J. Hand, P. Juszczak, D. Weston, and N. M. Adams, “Transaction aggregation as a strategy for credit card fraud detection,” Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 30–55, 2016.

- [A3]

- J. Jurgovsky, M. Granitzer, K. Ziegler, S. Calabretto, P.-E. Portier, L. He-Guelton, and O. Caelen, “Sequence classification for credit-card fraud detection,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 100, pp. 234–245, 2017.

- [A4]

- Y. Lucas, P.-E. Portier, L. Laporte, L. He-Guelton, O. Caelen, M. Granitzer, and S. Calabretto, “Credit card fraud detection using machine learning: A survey,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.06439, 2017.

- [A5]

- S. Misra, S. Thakur, M. Ghosh, and S. K. Saha, “Credit card fraud detection using computational intelligence techniques,” in 2018 Int. Conf. on Information Technology (ICIT), pp. 1–6, IEEE, 2018.

- [A6]

- B. Lebichot, T. Verhelst, Y.-A. Le Borgne, L. He-Guelton, F. Oblé, and G. Bontempi, “Transfer learning strategies for credit card fraud detection,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 114754–114766, 2018.

- [A7]

- V. R. Dornadula and S. Geetha, “Credit card fraud detection using machine learning algorithms,” Procedia Computer Science, vol. 165, pp. 631–641, 2019.

- [A8]

- A. Thennakoon, C. Bhagyani, S. Premadasa, S. Mihiranga, and N. Kuruwitaarachchi, “Real-time credit card fraud detection using machine learning,” in 2019 9th Int. Conf. on Cloud Computing, Data Science & Engineering (Confluence), pp. 488–493, IEEE, 2019.

- [A9]

- A. Pumsirirat and L. Yan, “Credit card fraud detection using deep learning based on auto-encoder and restricted Boltzmann machine,” Int. J. of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 18–25, 2019.

- [A10]

- S. Khatri, A. Arora, and A. P. Agrawal, “Credit card fraud detection using machine learning models and collating machine learning models,” Int. J. of Pure and Applied Mathematics, vol. 118, no. 20, pp. 825–838, 2020.

- [A11]

- N. Rtayli and N. Enneya, “Enhanced credit card fraud detection based on SVM-recursive feature elimination and hyper-parameters optimization,” J. of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 32, no. 9, pp. 1062–1070, 2020.

- [A12]

- M. M. Hassan, A. Amanat, T. Ahmed, and M. M. Toma, “Credit card fraud detection using deep learning,” Int. J. of Computer Applications, vol. 975, no. 8887, pp. 34–38, 2020.

- [A13]

- K. Huang, “An optimized LightGBM model for fraud detection,” J. of Physics: Conf. Series, vol. 1651, no. 1, p. 012111, 2021.

- [A14]

- E. Duman and M. H. Ozcelik, “A cost-sensitive random forest approach for credit card fraud detection,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 165, p. 113912, 2021.

- [A15]

- T. H. Pranto, K. M. Hasib, T. Rahman, A. B. Haque, A. N. Islam, and R. M. Rahman, “Blockchain and machine learning for fraud detection: A privacy-preserving and adaptive incentive based approach,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 87115–87134, 2021.

- [A16]

- Y. Y. Festa and I. A. Vorobyev, “A hybrid machine learning framework for e-commerce fraud detection,” Model Assisted Statistics and Applications, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 41–49, 2021.

- [A17]

- H. Chi, Y. Lu, B. Liao, L. Xu, and Y. Liu, “An optimized quantitative argumentation debate model for fraud detection in e-commerce transactions,” IEEE Intelligent Systems, vol. 36, no. 2, pp. 52–63, 2021.

- [A18]

- J. Forough and S. Momtazi, "Ensemble of deep sequential models for credit card fraud detection," Applied Soft Computing, vol. 99, p. 106883, Feb. 2021.

- [A19]

- K. N. Mishra, V. P. Mishra, S. Saket, and S. P. Mishra, “Performance evaluation of machine learning methods for credit card fraud detection using SMOTE and AdaBoost,” in 2021 Int. Conf. on Advances in Computing and Communications (ICACC), pp. 1–8, IEEE, 2021.

- [A20]

- M. H. Nasr, M. H. Farrag, and M. M. Nasr, “A proposed fraud detection model based on e-payments attributes: A case study in Egyptian e-payment gateway,” Int. J. of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 179–186, 2022.

- [A21]

- S. Dalal, B. Seth, M. Radulescu, C. Secara, and C. Tolea, “Predicting fraud in financial payment services through optimized hyper-parameter-tuned XGBoost model,” Mathematics, vol. 10, no. 24, p. 4679, 2022.

- [A22]

- E. K. Ampomah, Z. Qin, and G. Nyame, “Evaluation of tree-based ensemble machine learning models in predicting stock price direction of movement,” Information, vol. 11, no. 6, p. 332, 2022.

- [A23]

- D. H. Lim and H. Ahn, “A study on fraud detection in the C2C used trade market using Doc2vec,” Journal of Intelligence and Information Systems, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 27–44, 2022.

- [A24]

- N. Drydakis, “Artificial intelligence and reducing business risk in SMEs: COVID-19 dynamic capacity analysis during a pandemic,” Information Systems Frontiers, vol. 24, pp. 1223–1247, 2022.

- [A25]

- A. Singh and A. Jain, “Credit card fraud detection using isolation forest technique,” in 2022 Int. Conf. on Sustainable Computing and Data Communication Systems (ICSCDS), pp. 711–715, IEEE, 2022.

- [A26]

- A. Abdallah, M. A. Maarof, and A. Zainal, “Imbalanced credit card fraud detection data: A solution based on hybrid neural network and clustering-based undersampling technique,” Applied Soft Computing, vol. 132, p. 109830, 2023.

References

- The Nilson Report, "Payment Card Fraud Losses Reach $32.34 Billion," Issue 1164, April 2019.

- Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, "Report to the Nations: 2022 Global Study on Occupational Fraud and Abuse," 2022.

- M. Homaei, A. C. M. Homaei, A. C. Lindo, Ó. Mogollón-Gutiérrez, and J. D. Alonso, “The role of artificial intelligence in DT’s cybersecurity,” in Proc. 17th Reunión Española sobre Criptología y Seguridad de la Información (RECSI), 2022, p. 133.3.

- M. Homaei, Ó. Mogollón-Gutiérrez, J. C. Sancho, M. Ávila, and A. Caro, “A review of digital twins and their application in cybersecurity based on artificial intelligence,” Artificial Intelligence Review, vol. 57, no. 8, Jul. 2024.

- A. Dal Pozzolo, O. A. Dal Pozzolo, O. Caelen, Y.-A. Le Borgne, S. Waterschoot, and G. Bontempi, "Learned lessons in credit card fraud detection from a practitioner perspective," Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 41, no. 10, pp. 4915–4928, 2014.

- A. Dal Pozzolo, G. A. Dal Pozzolo, G. Boracchi, O. Caelen, C. Alippi, and G. Bontempi, "Credit card fraud detection: a realistic modeling and a novel learning strategy," IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, vol. 29, no. 8, pp. 3784–3797, 2018.

- F. Carcillo, A. F. Carcillo, A. Dal Pozzolo, Y.-A. Le Borgne, O. Caelen, Y. Mazzer, and G. Bontempi, "Scarff: a scalable framework for streaming credit card fraud detection with spark," Information Fusion, vol. 41, pp. 182–194, 2018.

- T. Saito and M. Rehmsmeier, "The precision-recall plot is more informative than the ROC plot when evaluating binary classifiers on imbalanced datasets," PLoS One, vol. 10, no. 3, p. e0118432, 2015.

- E. Ileberi, Y. E. Ileberi, Y. Sun, and Z. Wang, "A machine learning based credit card fraud detection using the GA algorithm for feature selection," Journal of Big Data, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 1–24, 2022.

- D. Varmedja, M. D. Varmedja, M. Karanovic, S. Sladojevic, M. Arsenovic, and A. Anderla, "Credit card fraud detection-machine learning methods," in 18th International Symposium INFOTEH-JAHORINA (INFOTEH), pp. 1–5, IEEE, 2019.

- K. Randhawa, C. K. K. Randhawa, C. K. Loo, M. Seera, C. P. Lim, and A. K. Nandi, "Credit card fraud detection using AdaBoost and majority voting," IEEE Access, vol. 6, pp. 14277–14284, 2018.

- Y. Sahin, S. Y. Sahin, S. Bulkan, and E. Duman, "A cost-sensitive decision tree approach for fraud detection," Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 40, no. 15, pp. 5916–5923, 2013.

- J. O. Awoyemi, A. O. J. O. Awoyemi, A. O. Adetunmbi, and S. A. Oluwadare, "Credit card fraud detection using machine learning techniques: A comparative analysis," in 2017 International Conference on Computing Networking and Informatics (ICCNI), pp. 1–9, IEEE, Oct. 2017.

- J. Li, S. J. Li, S. Chen, and M. Wang, "A Deep Learning Method of Credit Card Fraud Detection Based on Continuous-Coupled Neural Networks," Mathematics, vol. 13, no. 5, p. 819, 2025.

- I. D. Mienye and Y. Sun, "A deep learning ensemble with data resampling for credit card fraud detection," IEEE Access, vol. 11, pp. 30628–30638, 2023.

- X. Zhang, Y. X. Zhang, Y. Han, W. Xu, and Q. Wang, "HOBA: A novel feature engineering methodology for credit card fraud detection with a deep learning architecture," Information Sciences, vol. 557, pp. 302–316, 2021.

- S. Hochreiter and J. Schmidhuber, "Long short-term memory," Neural Computation, vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 1735–1780, 1997.

- M. Ahmed, S. M. Ahmed, S. Rahman, and M. S. Hossain, "Enhancing Credit Card Fraud Detection: An Ensemble Machine Learning Approach," Big Data and Cognitive Computing, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 6, 2024.

- T. Chen and C. Guestrin, "Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system," in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, pp. 785–794, 2016.

- F. T. Liu, K. M. F. T. Liu, K. M. Ting, and Z.-H. Zhou, "Isolation forest," in 2008 Eighth IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, pp. 413–422, IEEE, 2008.

- M. M. Breunig, H.-P. M. M. Breunig, H.-P. Kriegel, R. T. Ng, and J. Sander, "LOF: identifying density-based local outliers," ACM SIGMOD Record, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 93–104, 2000.

- L. Ding, L. L. Ding, L. Liu, Y. Wang, P. Shi, and J. Yu, "An AutoEncoder enhanced light gradient boosting machine method for credit card fraud detection," PeerJ Computer Science, vol. 10, p. e2323, Oct. 2024.

- M. El Alami, N. M. El Alami, N. Innan, M. Shafique, and M. Bennai, "Comparative Performance Analysis of Quantum Machine Learning Architectures for Credit Card Fraud Detection," arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.19441, 2024.

- S. Xiang, M. S. Xiang, M. Zhu, D. Cheng, E. Li, R. Zhao, Y. Ouyang, L. Chen, and Y. Zheng, "Semi-supervised Credit Card Fraud Detection via Attribute-Driven Graph Representation," in Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, vol. 37, no. 12, pp. 14557–14565, June 2023.

- C. Yu, Y. C. Yu, Y. Xu, J. Cao, Y. Zhang, Y. Jin, and M. Zhu, "Credit Card Fraud Detection Using Advanced Transformer Model," in 2024 IEEE International Conference on Metaverse Computing, Networking, and Applications (MetaCom), pp. 343–350, IEEE, Aug. 2024.

- N. V. Chawla, K. W. N. V. Chawla, K. W. Bowyer, L. O. Hall, and W. P. Kegelmeyer, "SMOTE: synthetic minority over-sampling technique," Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, vol. 16, pp. 321–357, 2002.

- V. Soni, "Fraud Detection in Credit Card Transactions: A Machine Learning Approach," Journal of Electrical Systems, vol. 20, no. 11s, pp. 3938–3954, Nov. 2024.

- M. Abdul Salam, K. M. M. Abdul Salam, K. M. Fouad, D. L. Elbably, and S. M. Elsayed, "Federated learning model for credit card fraud detection with data balancing techniques," Neural Computing and Applications, vol. 36, no. 11, pp. 6231–6256, Jan. 2024.

| Study | Algorithm | Acc.(%) | Prec.(%) | F1(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ileberi et al. [9] | RF + GA | 99.98 | 99.97 | 99.98 |

| Varmedja et al. [10] | Random Forest | 99.96 | 99.95 | 99.96 |

| Randhawa et al. [11] | AdaBoost + RF | 99.92 | 99.89 | 99.91 |

| Sahin et al. [12] | Cost-sensitive DT | 95.24 | 92.18 | 93.67 |

| Category | Best(%) | Avg(%) | F1(%) | RT Cap. | Interp. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF + GA [9] | 99.98 | 99.50 | 99.98 | High | High |

| Ensemble [18] | 99.99 | 99.70 | 99.99 | Medium | Medium |

| LSTM [16] | 99.20 | 98.80 | 92.50 | Low | Low |

| Neural Nets [15] | 99.94 | 99.10 | 98.00 | Medium | Low |

| SVM [13] | 98.90 | 98.20 | 97.10 | High | Medium |

| Traditional ML | 96.80 | 95.50 | 94.20 | High | High |

| Quantum ML [23] | 88.10 | 88.10 | 88.10 | Very Low | Low |

| Method | Training | Memory | Scalability | Noise |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complexity | Req. | Robustness | ||

| Random Forest | Low | Medium | Excellent | High |

| SVM | High | Medium | Poor | Medium |

| Neural Networks | High | High | Good | Low |

| LSTM/RNN | Very High | Very High | Poor | Low |

| Ensemble Methods | Medium | High | Good | Very High |

| Naive Bayes | Very Low | Very Low | Excellent | Medium |

| Logistic Regression | Low | Low | Excellent | Medium |

| Isolation Forest | Low | Low | Excellent | High |

| One-Class SVM | High | Medium | Poor | Medium |

| Autoencoders | High | High | Good | Low |

| Quantum ML | Very High | Low | Unknown | Unknown |

| Graph Neural Nets | Very High | Very High | Poor | Medium |

| Transformers | Very High | Very High | Poor | Medium |

| Method | Hyperparameter | Industry | Data Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Adoption | Needs | |

| Random Forest | Low | Very High | Medium |

| SVM | High | Medium | Medium |

| Neural Networks | Very High | High | High |

| LSTM/RNN | Very High | Medium | Very High |

| Ensemble Methods | Medium | High | Medium |

| Naive Bayes | Very Low | Low | Low |

| Logistic Regression | Low | High | Low |

| Isolation Forest | Low | Medium | Medium |

| One-Class SVM | High | Low | Medium |

| Autoencoders | High | Medium | High |

| Quantum ML | Very High | Very Low | Medium |

| Graph Neural Nets | Very High | Very Low | High |

| Transformers | Very High | Low | Very High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).