1. Introduction

The rapid urbanization and expansion of cities globally have underscored the necessity for precise and scalable methods to analyze and visualize urban environments. Roof segmentation, the process of identifying and delineating roof structures within satellite or aerial imagery, is a critical component in various urban applications. These applications range from urban planning and infrastructure management to the deployment of renewable energy systems such as solar panels, where accurate roof segmentation is crucial for assessing potential solar exposure areas [

1].

However, extracting meaningful information from satellite imagery presents several challenges, particularly in the context of roof segmentation. Satellite images often suffer from lower resolution compared to UAV images, making it difficult to accurately delineate small or intricate roof structures. The lower resolution results in a loss of fine details, which is critical for identifying and segmenting complex roof geometries, especially in densely built urban environments where buildings are closely packed, and roofs may overlap or be partially obscured by shadows or vegetation [

2]. This lack of detail can significantly impact the accuracy of segmentation, leading to errors in subsequent applications such as solar panel installation, where precise identification of available roof surfaces is essential.

In contrast, UAV images typically offer higher resolution and more detailed visual information, allowing for more precise segmentation of roofs and other urban features. Despite this advantage, the use of UAVs is often limited by regulatory constraints, cost, and the need for extensive flight planning in large urban areas. Consequently, satellite imagery remains a widely used data source, albeit with inherent challenges [

3].

Another critical aspect of roof segmentation is the identification of unused or underutilized roof surfaces. These areas hold significant potential for renewable energy projects, particularly in the context of urban solar energy generation. Accurately identifying and segmenting these surfaces from satellite imagery is vital for optimizing the deployment of solar panels, which requires precise calculations of available space and exposure to sunlight [

4]. The complexity of urban environments, combined with the limitations of satellite imagery, makes this task particularly challenging, necessitating the development and application of advanced deep learning models to improve segmentation accuracy.

Traditional image segmentation methods often struggle with the complexities inherent in urban scenes, which are characterized by roofs of varying shapes, sizes, materials, and colors. These methods frequently result in inaccurate or incomplete segmentation, particularly in dense urban areas where overlapping structures and shadows add to the challenge [

3]. To address these challenges, recent advancements in deep learning have introduced more sophisticated models capable of capturing intricate details in complex imagery. Among these, Mask R-CNN has emerged as a prominent model due to its ability to perform instance segmentation by accurately identifying and classifying individual objects within an image, making it particularly useful for segmenting roofs in heterogeneous urban landscapes [

1].

Despite the effectiveness of Mask R-CNN, its reliance on predefined categories and its limitations in handling very fine-grained details have led to the development of newer models such as MaskFormer. These limitations stem from the inherent architecture of traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs), which primarily focus on local features due to their reliance on convolutional layers. This focus on local regions can hinder the model's ability to capture global context and intricate details necessary for tasks such as roof segmentation in complex urban environments [

5].

The introduction of transformers into computer vision represents a significant advancement in overcoming the limitations of traditional convolutional neural networks (CNNs). Transformers, originally designed for natural language processing, utilize a self-attention mechanism that enables the model to weigh the importance of different elements across the entire input data [

6]. In the context of image segmentation, this mechanism allows the model to capture long-range dependencies and relationships between distant pixels, improving its ability to understand and segment objects that may be spread across an image or obscured by overlapping structures. Traditional CNNs primarily rely on local operations, processing small patches of the image with filters, which can make it challenging to effectively capture global context. By contrast, transformers apply attention mechanisms that consider the entire image at once, allowing the model to simultaneously capture both local and global features [

2].

Transformer architectures have gained significant traction in the field of computer vision due to their exceptional capacity to capture intricate patterns and relationships within image data. Prominent examples include the Vision Transformer (ViT), Data-efficient Image Transformers (DeiT), and the Swin Transformer, which introduces a hierarchical structure to enhance scalability and efficiency in high-resolution image processing [

2].

MaskFormer capitalizes on the strengths of transformers by combining them with convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to form a unified query-based framework adept at both semantic and instance segmentation tasks. Its ability to maintain a global perspective while focusing on specific image regions enhances segmentation accuracy, especially in complex environments like urban areas [

5]. MaskFormer also features a module that converts existing per-pixel classification models into a mask classification approach, using the set prediction mechanism from DETR [

7] to predict both the class and shape of roof segments, improving segmentation in dense urban settings.

This study aims to evaluate the performance of these advanced models Mask R-CNN, and MaskFormer, by analyzing quantitative metrics such as Intersection over Union (IoU), precision, recall, and F1-score, alongside qualitative assessments to contribute to more accurate urban imaging solutions.

2. Related Works

Roof segmentation has been a critical area of research due to its applications in urban planning, renewable energy deployment, 3D modeling, and infrastructure management. Traditional image processing techniques, such as edge detection, region growing, and manual annotation, were initially employed but were labor-intensive and error-prone, particularly in complex urban environments where roof structures vary significantly, leading to limited accuracy and scalability [

8].

The advent of deep learning revolutionized the field, with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) becoming the primary tool for image segmentation. Early examples, like the use of CNNs for aerial image segmentation, showed promise in detecting and segmenting buildings and roofs. The introduction of Fully Convolutional Networks (FCNs) further advanced the field by enabling pixel-wise segmentation of entire images, improving accuracy and efficiency in various segmentation tasks, including urban imagery [

9].

Building on these advancements, Mask R-CNN added a branch for predicting object masks, facilitating precise instance segmentation and becoming widely adopted for urban roof segmentation due to its ability to accurately delineate individual roofs in dense urban settings [

9].

The development of transformers marked the next significant leap. Originally designed for natural language processing, transformers utilize self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies within an image, particularly benefiting the segmentation of complex structures like roofs where global context is crucial [

8].

This approach was refined by Vision Transformers (ViTs), which effectively processed images as sequences of patches to capture both local and global [

10].

Recent studies have continued to push the boundaries of roof segmentation. For instance, Roof-Former introduced a deep learning model based on vision transformers that uses structural reasoning and edge-based refinement to accurately segment planar roof geometries, outperforming prior state-of-the-art methods [

10].

Additionally, transformer-based approaches have shown the ability to capture both macro and micro-level features in urban images, leading to more precise segmentation outcomes and underscoring the growing importance of transformers in handling the intricate details required for effective roof segmentation [

11].

The latest advancements, such as MaskFormer, combine the strengths of transformers with CNNs to enhance both semantic and instance segmentation tasks. MaskFormer integrates a unified query-based framework that excels in complex urban environments, particularly where conventional CNNs fall short [

12].

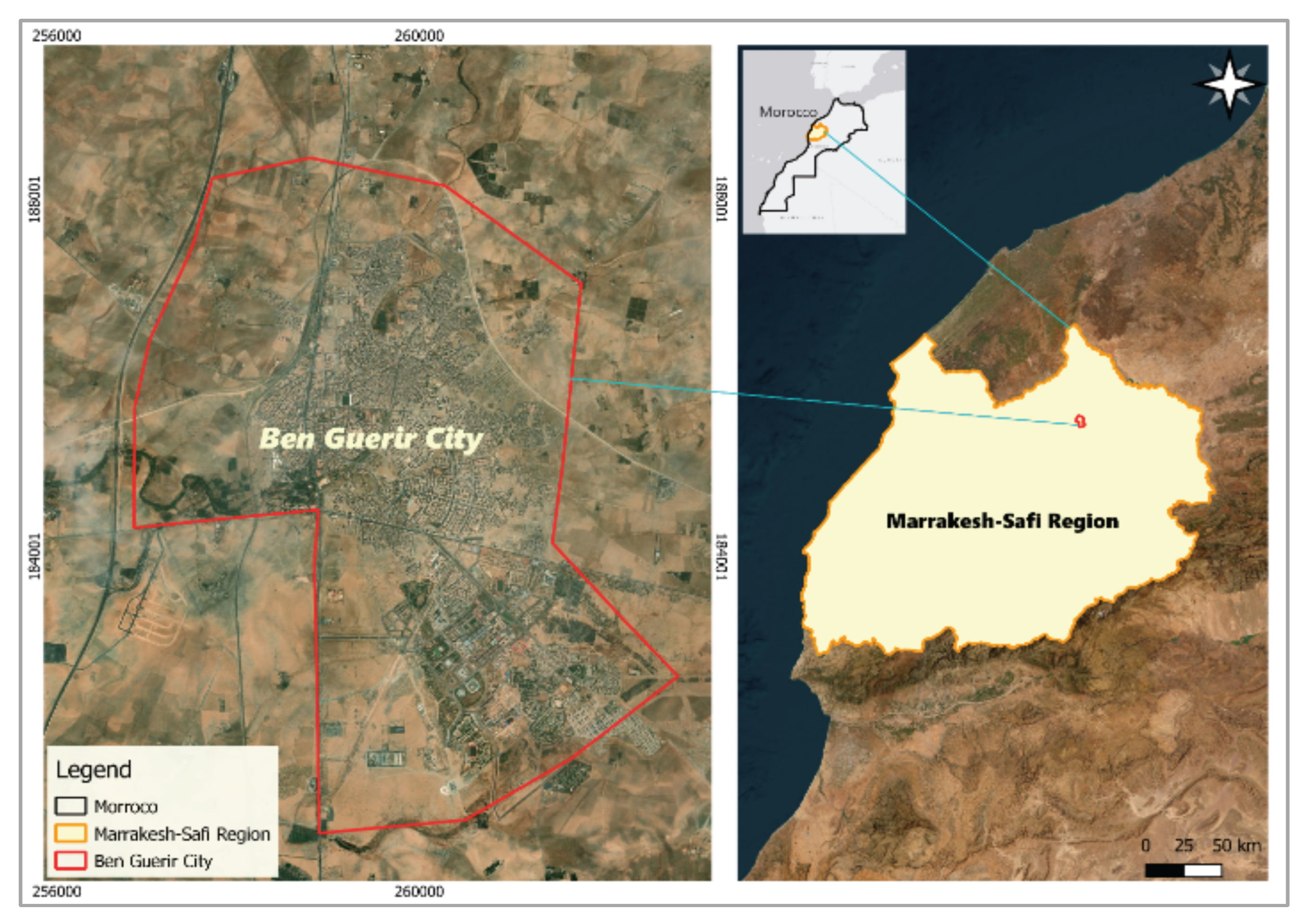

3. Study Area

The study focuses on Ben Guerir City, situated in the Rhamna Province of the Marrakesh-Safi region in central Morocco. Geographically, Ben Guerir is located at approximately 32.23° North latitude and 7.95° West longitude, encompassing an area of around 45 square kilometers [

13].

Ben Guerir serves as a strategic urban center due to its proximity to major economic hubs and its position along the transportation corridor connecting Casablanca and Marrakesh. The city has experienced significant growth, partly due to the establishment of the Mohammed VI Polytechnic University (UM6P), a research-intensive institution promoting innovation in science and technology [

14].

Economically, Ben Guerir is known for its phosphate mining industry and hosts one of the largest deposits managed by the OCP Group, a key contributor to Morocco’s phosphate exports and national economy [

15].

The city's population is estimated to be over 100,000 residents, reflecting its rapid urban expansion and demographic dynamism. Urban development efforts, including eco-districts and solar energy projects, have made Ben Guerir an important case for sustainable urban planning [

16].

Figure 1.

Location of Ben Guerir City within Morocco and the Marrakesh-Safi Region.

Figure 1.

Location of Ben Guerir City within Morocco and the Marrakesh-Safi Region.

Climatically, Ben Guerir experiences a semi-arid climate, with hot, dry summers and mild, wetted winters. The average annual temperature is around 19 °C, and total annual precipitation is about 300 mm, making the region suitable for solar energy development [

13].

The surrounding landscape features a mix of agriculture, native vegetation, and growing industrial zones. This heterogeneity supports research in urban-environmental interactions, and the city's combination of rapid growth, environmental constraints, and energy innovation makes it a prime location for spatial analysis using advanced roof segmentation and solar planning models.

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Collection and Sources

The spatial boundary of Ben Guerir City utilized in this study was derived from the "Administrative Division 2015" of Morocco, which provides the most recent and accurate delineation of administrative boundaries in the country. This administrative boundary data is essential for ensuring that the analysis is confined strictly within the city's official limits, thereby enhancing the precision and relevance of the study's findings [

17].

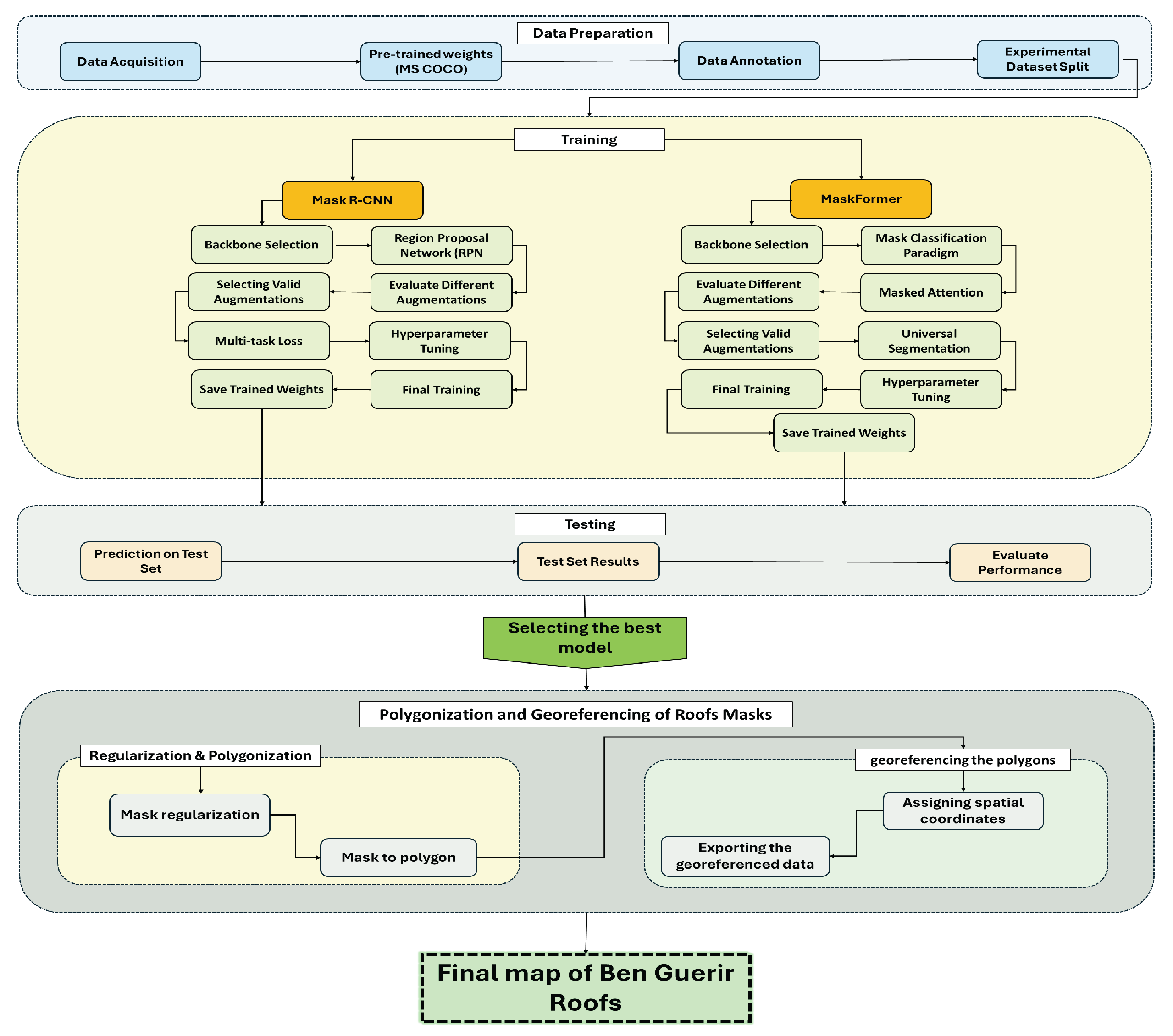

Figure 2.

End-to-End Workflow for Roof Segmentation and Georeferencing Using Deep Learning and Advanced Architectures.

Figure 2.

End-to-End Workflow for Roof Segmentation and Georeferencing Using Deep Learning and Advanced Architectures.

To obtain high-resolution satellite imagery for the study area, we used Google Earth imagery accessed through the QGIS software platform. The imagery for the Marrakesh-Safi region, with a specific focus on Ben Guerir, was acquired at a resolution of 0.3 meters. This high-resolution data is crucial for capturing detailed features of the urban landscape, particularly the roofs, which are the primary focus of this research [

13]. The choice of QGIS as the software tool allows for efficient handling and manipulation of the imagery, thanks to its powerful geospatial data processing capabilities [

13].

Once the imagery was acquired, the data was split into manageable patches of 512×512 pixels using a combination of Rasterio, NumPy, Pandas, and Shutil libraries. This step is essential for preparing the data for model training, as it allows the large images to be broken down into smaller, more uniform pieces that can be processed more efficiently by the segmentation models. The images, originally in TIFF format, were then converted to JPEG format using the Python Imaging Library (PIL). The conversion to JPEG is necessary to facilitate compatibility with the image annotation tools and to reduce the file size, making it easier to handle large datasets [

13].

The annotation process involved manually labeling the roofs in the images using Roboflow and makesense.ai, which are platforms designed for efficient and accurate image annotation. These tools provide user-friendly interfaces for drawing bounding boxes, polygons, and other shapes around objects of interest—in this case, roofs. The labels were then exported in COCO format, a popular format for object detection and segmentation tasks, which includes metadata such as the location and size of each labeled object.

To prepare these annotations for use in segmentation models, the labels were converted from the original text format into mask images using NumPy. This step involves creating binary mask images where each pixel belonging to a roof is marked, providing a ground truth for model training. The conversion process is critical for ensuring that the annotations are in a format compatible with deep learning frameworks, which typically require pixel-wise label information.

4.2. Image Preprocessing

4.2.1. Noise Reduction

To ensure the quality and accuracy of the roof segmentation process, it is essential to first address any noise present in the satellite images. Noise in satellite imagery can result from various sources, including sensor anomalies, atmospheric conditions, or compression artifacts. To mitigate these effects, techniques such as Gaussian filtering and Median filtering are employed. Gaussian filtering smooths the image by averaging the pixel values with their neighbors, effectively reducing random noise while preserving important edges. Median filtering, on the other hand, replaces each pixel's value with the median value of the surrounding pixels, which is particularly effective for removing salt-and-pepper noise without significantly blurring the image [

18]. These noise reduction techniques are crucial for enhancing the clarity of the images, thereby improving the accuracy of subsequent segmentation tasks.

4.2.2. Georeferencing and Resampling

After converting the satellite images from TIFF to JPEG format, metadata such as the geographical coordinates, projection, and pixel resolution extracted during the conversion process are used to georeferenced the images and their corresponding masks. Georeferencing involves aligning the images to a common coordinate system, which is critical for ensuring that the spatial relationships within the imagery are accurate and consistent across the dataset (Bolstad, 2016). This is done by associating the pixel coordinates in the image with real-world coordinates, typically using geographic information systems (GIS) tools such as QGIS. Once georeferenced, the images and masks are resampled to ensure they share a consistent resolution and projection, which is vital for maintaining the spatial integrity of the data during analysis. Resampling techniques such as nearest-neighbor interpolation or bilinear interpolation are often used to adjust the image resolution while preserving as much detail as possible [

13].

4.2.3. Data Augmentation

To enhance the robustness of the segmentation models and improve their ability to generalize across various scenarios, data augmentation is applied to the training dataset. Data augmentation involves generating additional training samples by applying random transformations to the original images, thereby increasing the diversity of the dataset without the need for additional labeled data. In this study, the application of data augmentation techniques results in a fivefold (x5) increase in the effective size of the training dataset. Common augmentation techniques include rotation, flipping, scaling, cropping, and brightness adjustments. These transformations help the model learn to recognize roofs under different orientations, lighting conditions, and scales, making the model more versatile and effective when applied to real-world images [

19]. Augmentation is particularly important in deep learning tasks where the available labeled data is limited, as it artificially increases the size of the dataset and helps prevent overfitting, ultimately leading to a significant expansion in training data, which is crucial for the success of the segmentation models [

20].

4.3. Segmentation Models

4.3.1. Training and Validation

The training and validation process forms the backbone of the model development pipeline, ensuring that the deep learning models are not only well-fitted to the training data but also capable of generalizing to new, unseen images. In this study, the dataset is meticulously split into three parts: 70% for training, 10% for validation, and 20% for testing. This distribution is chosen to maximize the model's exposure to a diverse range of scenarios during training while retaining a separate validation set to tune hyperparameters and prevent overfitting. The final testing set, which is entirely unseen during training, provides an unbiased assessment of the model’s performance.

For training the segmentation models, the binary cross-entropy loss is employed for binary segmentation tasks, where each pixel is classified as either roof or non-roof. For multi-class segmentation tasks, categorical cross-entropy loss is used, enabling the model to handle more complex scenarios involving multiple classes [

21]. Additionally, Intersection over Union (IoU) loss is integrated to refine the segmentation accuracy by focusing on the overlap between the predicted and actual roof areas, which is crucial for precise urban applications [

21].

Hyperparameters are carefully selected to optimize model training. A learning rate of 0.001 ensures that the model converges efficiently without overshooting the optimal solution. A batch size of 16 is used, striking a balance between computational feasibility and model performance. The models are trained over 50 epochs, with early stopping implemented to halt training if the validation loss plateaus, thereby avoiding overfitting [

22].

4.3.2. Model Selection

In this study, two state-of-the-art deep learning models Mask R-CNN and MaskFormer are selected for roof segmentation due to their proven effectiveness in complex image segmentation tasks. These models are chosen based on their architecture and their ability to accurately segment roofs in urban environments, which present unique challenges due to the variability in roof shapes, sizes, and materials.

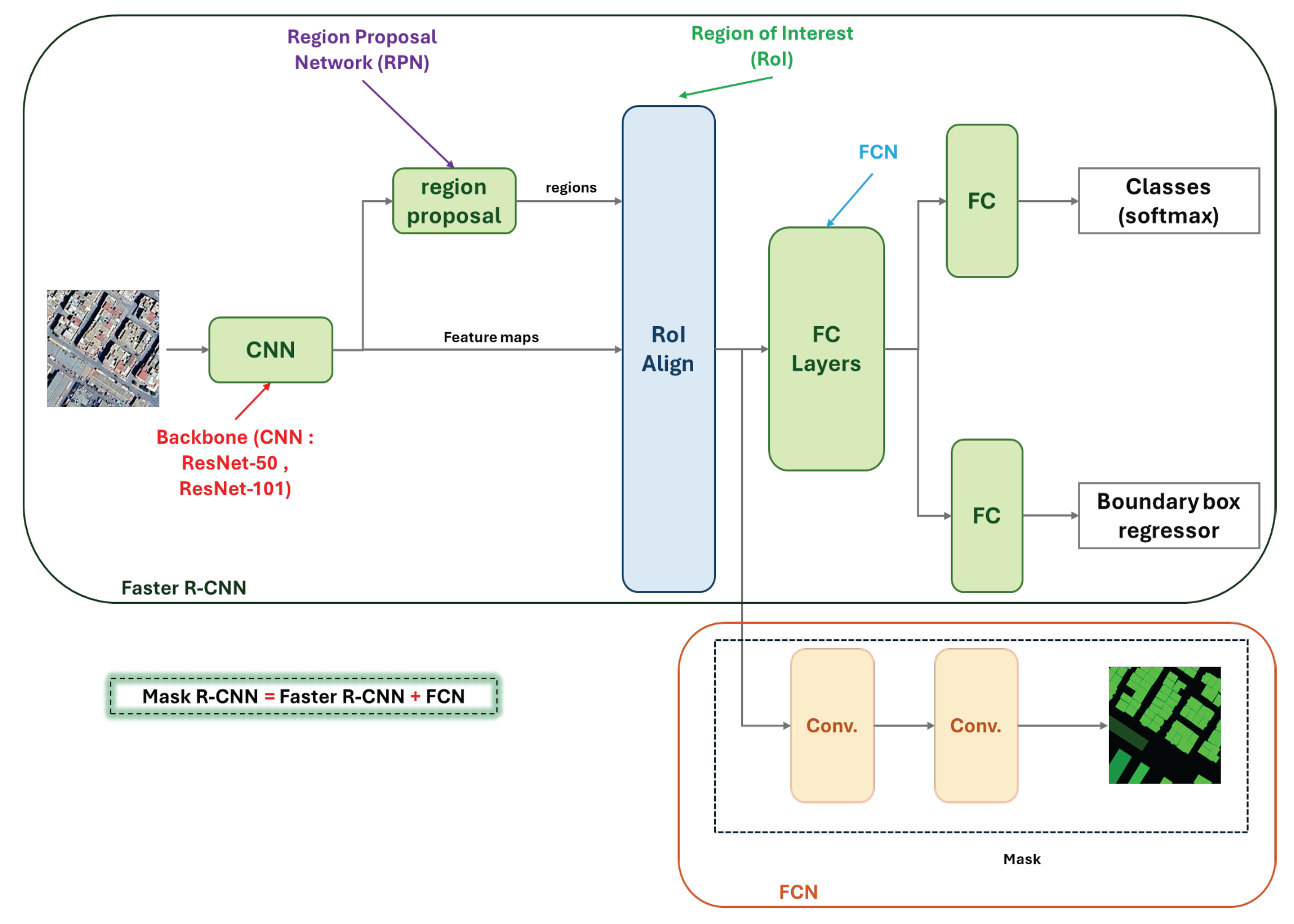

Mask R-CNN: Mask R-CNN extends Faster R-CNN by adding a branch for predicting segmentation masks on each Region of Interest (RoI), in parallel with the existing branch for classification and bounding box regression. This architecture is particularly advantageous for roof segmentation as it allows the model to simultaneously detect roofs and delineate their boundaries with high precision [

23]. The model’s ability to generate high-quality masks at the instance level makes it ideal for tasks where accurate roof delineation is essential, such as in urban planning and solar panel installation.

Figure 3.

Architecture of Mask R-CNN for Roof Segmentation.

Figure 3.

Architecture of Mask R-CNN for Roof Segmentation.

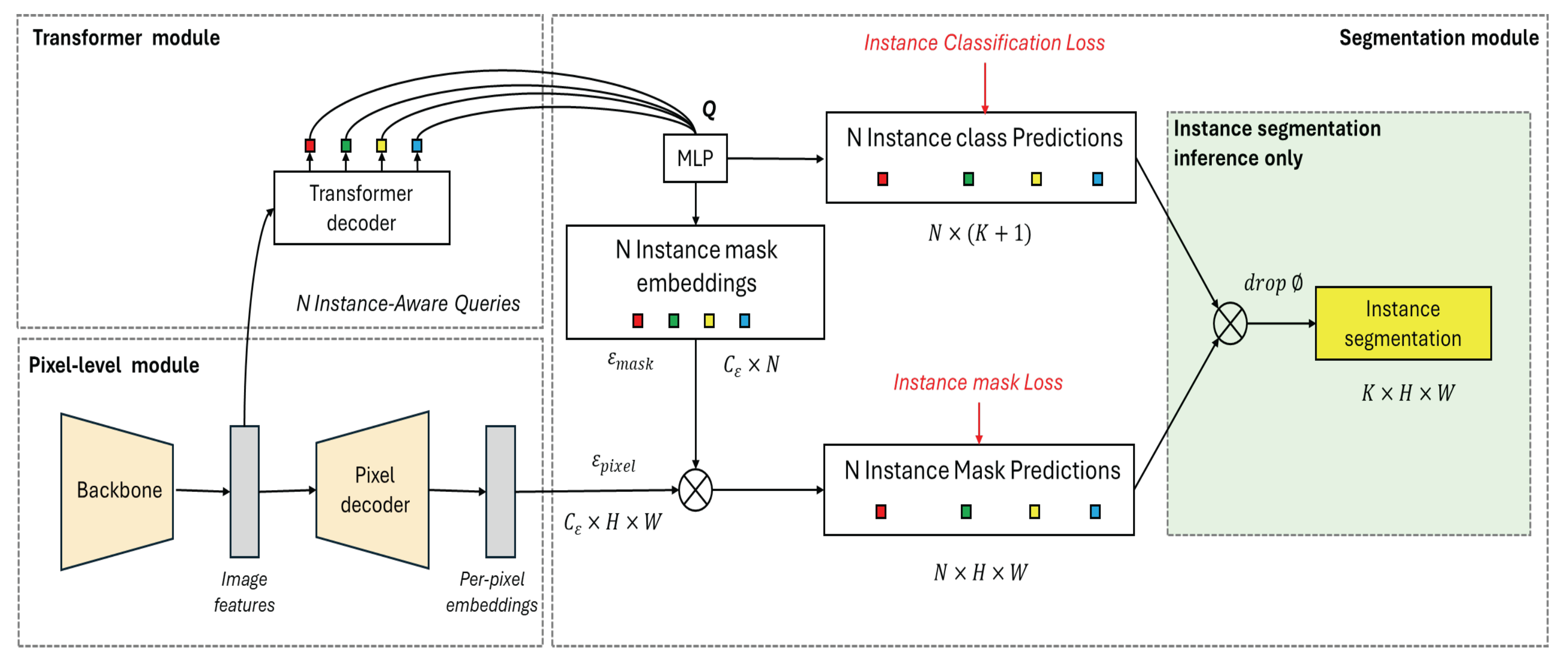

MaskFormer: MaskFormer represents a shift towards using transformers for segmentation tasks. Instead of relying on region proposals, MaskFormer treats image segmentation as a mask classification task, where each pixel is assigned to a specific class by leveraging attention mechanisms. This model excels in capturing global context and fine details, making it particularly effective for roof segmentation in dense urban environments where roofs can be obscured or partially visible [

22].

Figure 4.

Architecture of MaskFormer for Instance Segmentation.

Figure 4.

Architecture of MaskFormer for Instance Segmentation.

These models are selected not only for their cutting-edge architectures but also for their adaptability to the specific challenges posed by urban roof segmentation. Their integration into the study allows for a comprehensive analysis of their strengths and limitations in real-world applications.

4.4. Testing

After training, the models are evaluated on a separate test set to measure their performance. Predictions on the test data are compared to ground truth labels, and several performance metrics, including Intersection over Union (IoU), precision, recall, and F1-score, are calculated to assess model accuracy. These metrics follow standard practices in image segmentation and are widely adopted in remote sensing evaluations [

22]. Based on these evaluations, the model with the best performance—whether Mask R-CNN or MaskFormer—is selected for further use.

4.5. Post-Processing and Accuracy Assessment

After the initial segmentation process, raw segmentation outputs often require refinement to enhance the accuracy and usability of the results. This refinement is crucial for applications like urban planning and infrastructure management, where precise delineation of roofs is necessary.

4.5.1. Segmentation Refinement

To improve the quality of the segmentation outputs, post-processing techniques such as morphological operations and contextual filtering are employed. Morphological operations, including dilation and erosion, are used to clean up the segmentation masks by removing small artifacts and smoothing the boundaries of the segmented roofs [

24]. Dilation helps expand the boundaries of detected regions, connecting disjointed segments, while erosion shrinks the boundaries to remove noise. These operations are typically applied in sequence to achieve a balanced refinement of the segmentation output.

Contextual filtering further enhances segmentation by leveraging spatial information, ensuring that the segmented regions align with the expected shapes and sizes of roofs in the urban landscape. This process involves analyzing the spatial relationships between neighboring pixels and regions, refining the segmentation to better match real-world roof structures [

25]. By applying these techniques, model predictions are adjusted to produce more coherent and accurate roof segments, especially important in dense and complex urban scenes.

4.5.2. Accuracy Assessment

To quantitatively assess the performance of the segmentation models, several key metrics are used, including Intersection over Union (IoU), precision, recall, and F1-score.

- i.

-

Intersection over Union (IoU):

, also known as the Jaccard Index, measures the overlap between the predicted segmentation and the ground truth, normalized by their union. It is a widely used metric in image segmentation tasks as it directly evaluates the accuracy of the segmented regions. A higher IoU indicates better segmentation performance [

26].

is simply the average

across all categories or regions:

where

is the number of classes or regions, and

is the

for each individual class or region.

Mean IoU: It is the average of the IoU scores across all classes or regions. If there’s only one class or region, Mean IoU would be the same as IoU.

- ii.

-

Precision:

Precision measures the proportion of correctly identified roof pixels (true positives) against all pixels that were identified as roof pixels (true positives plus false positives). High precision indicates that the model is effective at minimizing false positives, which is crucial for reducing over-segmentation [

27].

- iii.

-

Recall:

Recall, also known as sensitivity, evaluates the proportion of correctly identified roof pixels out of all actual roof pixels (true positives plus false negatives). High recall indicates that the model successfully captures most of the roof pixels, reducing under-segmentation [

27].

- iv.

-

F1-Score:

The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances both. It is particularly useful when there is an uneven class distribution or when both false positives and false negatives are important to the task [

28].

These metrics ensure that the models are evaluated not only on their ability to segment roofs accurately but also on their capacity to minimize errors, which is especially important when dealing with complex urban scenes. By applying these refinement techniques and accuracy metrics, the segmentation outputs are optimized, delivering reliable and precise results that are essential for practical applications in urban planning and related fields.

4.6. Polygonization and Georeferencing of Roof Masks

The next step is the polygonization and georeferencing of the predicted roof masks. The masks are regularized to ensure smooth boundaries, a common post-processing step in segmentation tasks [

29]. These regularized masks are then converted into polygons, which represent the roof outlines.

The polygons are georeferenced by assigning them spatial coordinates, allowing the results to be mapped back onto their real-world geographic locations. This process is essential for integrating the segmented data into geographic information systems (GIS), a standard practice in remote sensing and geographic studies [

30].

The georeferenced polygons are exported in formats such as shapefiles or GeoJSON, enabling further spatial analysis or integration with GIS tools. This vectorization step ensures compatibility with downstream urban analytics and planning pipelines, where precise geometry and spatial accuracy are required [

31].

5. Results

5.1. Quantitative Evaluation

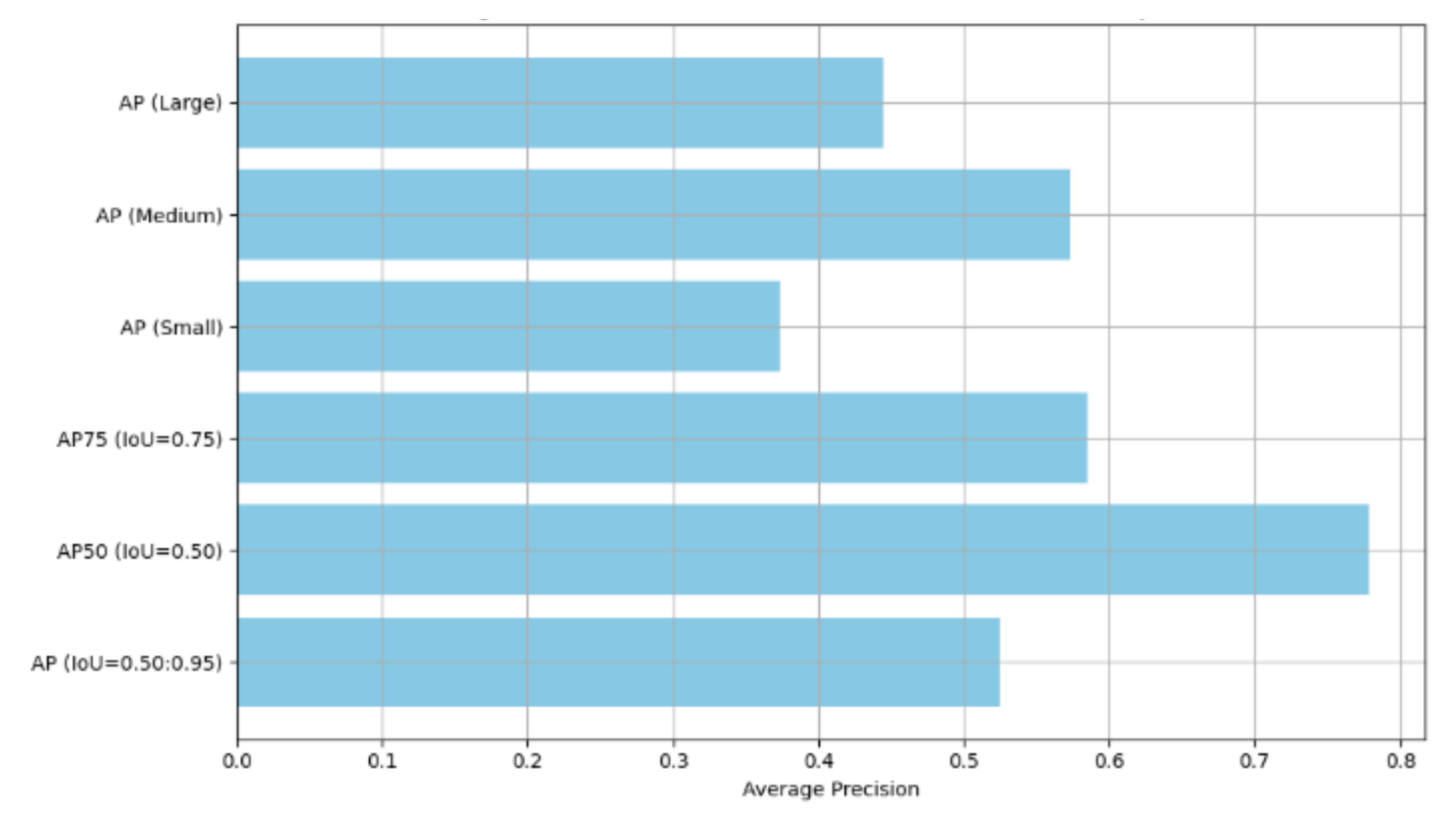

To assess the performance of the segmentation models, we evaluated Average Precision (AP) and Average Recall (AR) across different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds and object sizes (small, medium, and large). The evaluation is based on key metrics that reflect the model's ability to accurately detect and segment rooftops in Ben Guerir.

5.1.1. Average Precision (AP)

Figure 5 shows the AP results across various IoU thresholds and object sizes. Notably, the model performs best with large objects, achieving the highest precision at IoU thresholds of 0.50 (AP50). For smaller objects, the precision decreases, which is consistent with common challenges in instance segmentation tasks for small objects due to their fewer pixels and less distinct features.

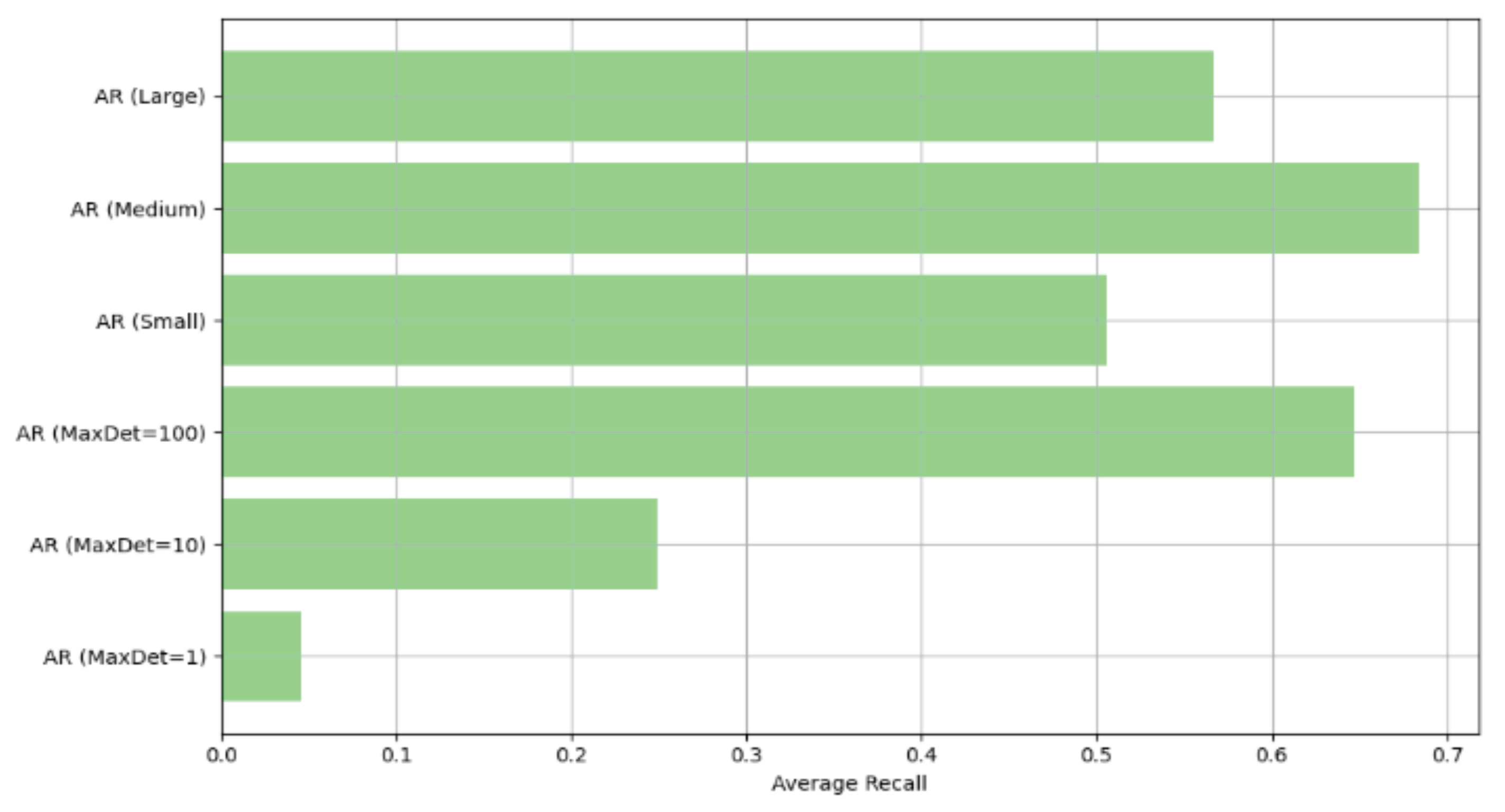

5.1.2. Average Recall (AR)

Figure 6 presents the AR results across different IoU thresholds and object sizes. Similar to the precision results, larger objects achieve higher recall values, indicating that the model is capable of capturing a significant portion of the rooftops in these cases. However, AR decreases for smaller objects and lower detection thresholds (e.g., MaxDet=1), where the model struggles to consistently detect and segment roofs in highly dense or complex urban areas.

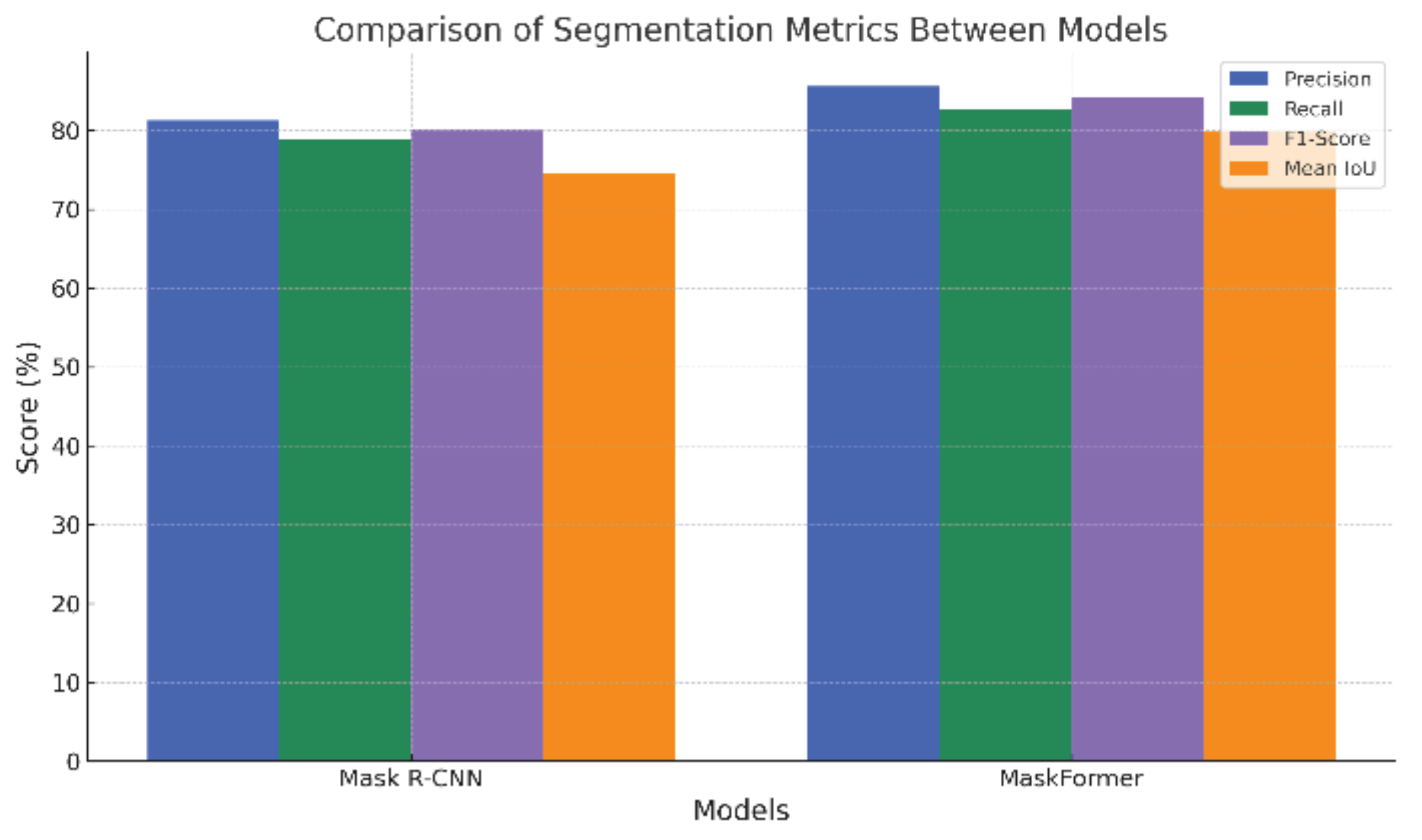

5.1.3. Comparative Metrics: Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and Mean IoU

To provide a detailed quantitative evaluation, four standard segmentation metrics: Precision, Recall, F1-Score, and Mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), were calculated and compared between the models. The results are summarized in

Figure 7.

To further benchmark the models,

Figure 7 presents a comparative evaluation based on four key metrics: Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Mean IoU. MaskFormer consistently achieves superior results, especially in Precision (+4.3%) and mIoU (+5.2%) compared to Mask R-CNN, highlighting its enhanced ability to capture complex rooftop geometries.

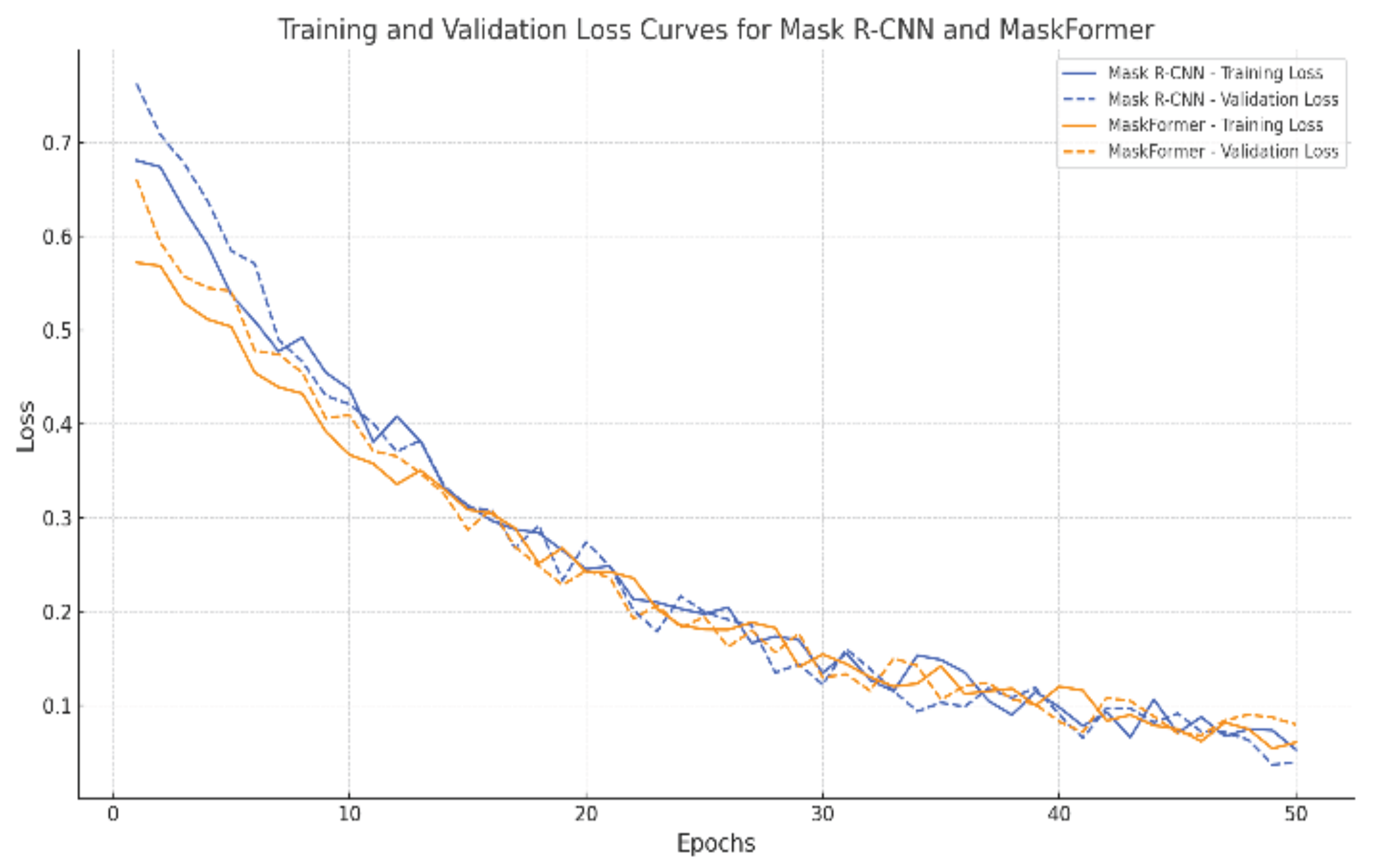

5.1.4. Training and Validation Loss Curves

The training and validation loss curves, shown in

Figure 8, illustrate the models’ convergence over 50 epochs. Both loss curves indicate stable and effective learning, demonstrating the robustness and generalization capability of the proposed segmentation models.

Figure 8 illustrates the training and validation loss curves for both Mask R-CNN and MaskFormer models. Both models demonstrate a steady decrease in training and validation loss, indicating effective learning. MaskFormer achieves a slightly smoother and lower validation loss compared to Mask R-CNN, suggesting better generalization capabilities on unseen satellite imagery. No significant overfitting was observed for either model.

Additionally,

Figure 8 presents the evolution of training and validation loss across 50 epochs. The gradual decline and stabilization of both losses without significant divergence indicate effective learning and minimal overfitting. The final convergence of validation loss near the training loss suggests that the models generalize well to unseen data, further validating the robustness of the training process.

5.2. Qualitative Results

In addition to quantitative evaluation, a qualitative assessment of the segmentation results was conducted to visually analyze the performance of Mask R-CNN and MaskFormer models. Representative examples from the test set were selected to illustrate how each model captures the roof structures in dense urban environments. Comparisons between the original satellite images, ground truth masks, and the predicted segmentation maps are presented in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10. These visual results provide further insights into the strengths and limitations of each model, particularly in handling small roofs, complex geometries, and occlusions such as shadows and vegetation.

5.2.1. Mask R-CNN

Figure 9 displays a representative example of rooftop segmentation results produced by the Mask R-CNN model. The original satellite image (Original image) shows a densely built urban environment with varying roof shapes and sizes. The ground truth mask (Ground Truth) accurately delineates individual rooftops with clear boundaries. The predicted mask (Segmented Map) demonstrates that Mask R-CNN successfully detects most medium and large roofs, closely matching the ground truth in many regions. However, some segmentation imperfections are noticeable, such as slight boundary smoothing, partial under-segmentation of smaller roofs, and minor misclassifications where rooftop edges are obscured by shadows or adjacent structures. Despite these challenges, the Mask R-CNN model achieves generally good performance in capturing the spatial extent of most rooftops.

5.2.2. MaskFormer

Figure 10 showcases the qualitative performance of the MaskFormer model on a dense urban area. The original satellite image (left) reveals a complex arrangement of tightly packed buildings with variable roof shapes and sizes. The predicted segmentation map (center) generated by MaskFormer accurately captures the rooftops with sharp boundaries and minimal false detections. Small, narrow, and irregularly shaped roofs are segmented with high fidelity, reflecting MaskFormer’s capacity to model fine-grained spatial features. The final georeferenced polygonized masks (right) demonstrate clean vectorized roof outlines, precisely matching the real-world structures. The results underline MaskFormer’s superior ability to handle complex roof geometries, occlusions, and high-density urban patterns, making it highly suitable for scalable urban analysis tasks.

5.3. Regularization Network for Roof Refinement

After the initial instance segmentation is performed by Mask R-CNN or MaskFormer, a second stage regularization network is employed to further refine each segmented roof. This additional step is critical to generate geometrically realistic and visually pleasing building masks, especially in dense urban environments where segmentation noise can degrade polygon extraction quality.

The regularization network is based on a modified version of the approach proposed by Zorzi & Fraundorfer [

32]. As illustrated in

Figure 11, the network architecture consists of a residual autoencoder that receives as input both the satellite intensity image and the predicted segmentation mask. It produces a refined mask by learning to align the segmentation more accurately with real building boundaries.

To train the regularization network, a combination of adversarial loss, reconstruction loss, and regularization loss is used:

- ▪

The reconstruction loss ensures that the refined mask closely resembles the initial segmentation.

- ▪

The regularization loss encourages the mask to align with the intensity patterns of the original image, promoting geometrically plausible structures.

- ▪

The adversarial loss is applied through a discriminator network, which forces the refined masks to be visually indistinguishable from ideal masks derived from OpenStreetMap data.

To address the mismatch between soft (0–1) regularized masks and binary (0 or 1) ideal masks, both real and fake masks are propagated through a common decoder (F) before being passed to the discriminator (D). This design stabilizes the adversarial training and ensures fair comparison between samples.

Encoders EG (for generated masks) and ER (for real masks) extract latent representations, which are jointly reconstructed by the common decoder F to produce the refined segmentation. This strategy helps mitigate format inconsistencies and enhances the overall stability and quality of training.

Finally, the refined regularized masks are used to extract building corners via a secondary lightweight CNN, followed by polygonization and filtering, resulting in clean, georeferenced building footprints ready for urban analysis.

This refinement stage significantly improves the quality and usability of the segmented outputs, enabling precise urban mapping applications such as building inventory, energy estimation, and urban resilience studies.

5.4. Final Rooftop Map Generation

The final output of this study is a detailed rooftop map of Ben Guerir, generated through the segmentation of high-resolution satellite imagery and subsequent georeferencing of the detected rooftops (see

Figure 12). This map provides a precise visualization of the spatial distribution and arrangement of roof structures across the urban landscape. The blue polygons represent the extracted rooftops, offering a comprehensive and accessible overview of the built environment.

This spatially accurate rooftop inventory constitutes a critical tool for urban planning, infrastructure management, and future development initiatives. By providing high-resolution spatial data, the map supports more efficient decision-making processes related to land use optimization, building management, and public services planning. Furthermore, the rooftop map serves as a foundational dataset for solar energy deployment studies, enabling researchers and planners to assess the solar potential of identified rooftops and to design targeted renewable energy strategies.

The segmentation and georeferencing approach adopted in this work demonstrates the scalability and automation potential of deep learning-based urban mapping methodologies. By leveraging convolutional and transformer-based models for segmentation, followed by regularization and polygon extraction techniques, the methodology ensures both high spatial precision and automation readiness.

Previous studies have highlighted the importance of rooftop mapping for sustainable urban development. For example, Castello in 2019 used CNNs to detect rooftop solar panels and demonstrated the feasibility of automated mapping at a national scale [

33]. Similarly, Qian et al. (2024) proposed a unified deep learning framework for large-scale rooftop segmentation and classification to support city-wide urban studies and policy development [

34].

The results presented here extend these efforts to the rapidly growing city of Ben Guerir. With its spatial accuracy and detailed coverage, the generated map offers a valuable resource for guiding future urban sustainability initiatives and renewable energy projects in the region.

6. Discussion

The evaluation of segmentation models through both quantitative metrics and qualitative analysis provides deep insights into their strengths and limitations when applied to rooftop extraction from high-resolution satellite imagery.

From the quantitative evaluation (

Section 5.1), MaskFormer consistently outperforms Mask R-CNN across all metrics, achieving higher precision, recall, F1-score, and mean Intersection over Union (mIoU). The superiority of transformer-based architectures is particularly evident in their ability to better capture global context, leading to improved delineation of complex roof structures. Additionally, training and validation loss curves reveal that MaskFormer converges more smoothly and reaches lower final loss values compared to Mask R-CNN, suggesting better generalization capabilities and robustness to overfitting.

The qualitative analysis (

Section 5.2) confirms these trends visually. MaskFormer generates cleaner and more accurate roof segmentations, with sharper boundary delineation and improved detection of small, irregularly shaped roofs. In contrast, Mask R-CNN performs adequately on larger rooftops but shows minor segmentation errors, such as boundary smoothing and under-segmentation, particularly in dense or shadowed areas.

While initial segmentation outputs are of high quality, especially for MaskFormer, the post-processing step introduced through the Regularization Network (

Section 5.3) significantly enhances the final results. By leveraging a residual autoencoder and adversarial training, the regularization network refines the masks to produce geometrically plausible, visually coherent building footprints. The integration of regularization, reconstruction, and adversarial losses allows the model to align the predicted masks closely with the real building boundaries visible in the satellite images. Moreover, by using a common decoder to process both real and generated masks before discrimination, the architecture effectively handles the mismatch between soft and binary mask formats, improving training stability.

Overall, the two-stage segmentation and regularization framework demonstrate strong performance, successfully addressing common challenges in rooftop extraction tasks, such as occlusions, variable building scales, and urban density. Nonetheless, certain limitations persist, such as slight inaccuracies in extremely small or heavily occluded buildings, highlighting avenues for future improvement through more advanced boundary refinement techniques or multimodal data fusion like combining optical imagery with elevation data.

These findings underscore the potential of deep learning and regularization techniques to advance large-scale urban mapping from satellite imagery, paving the way for more accurate, efficient, and automated building inventory generation.

7. Conclusions

This study has addressed the challenges of rooftop segmentation from satellite imagery by leveraging cutting-edge deep learning architectures and a two-stage processing pipeline. While traditional methods often struggle with complex roof geometries, occlusions, and dense urban settings, advanced instance segmentation models like Mask R-CNN and MaskFormer demonstrate superior performance. Through a comprehensive evaluation using metrics such as precision, recall, F1-score, and mean Intersection over Union (mIoU), MaskFormer emerged as the most effective, providing accurate delineation of rooftop structures across diverse urban landscapes.

Qualitative analysis further confirmed these results, with MaskFormer producing visually cleaner and more precise roof masks than Mask R-CNN, particularly in detecting small and irregular roofs. To enhance these results, a regularization network was introduced to refine the raw segmentation outputs. Based on a modified version of Zorzi's framework, the refinement stage employed adversarial, reconstruction, and regularization losses to produce masks that are not only geometrically plausible but also visually consistent with real building footprints. A common decoder was used to handle soft versus binary format mismatches during training, resulting in stable and accurate outputs.

The final result of this workflow is a high-resolution rooftop map of Ben Guerir, representing segmented, regularized, and georeferenced roof polygons. This map holds significant value for urban planning, infrastructure management, and renewable energy deployment, offering a scalable and automated solution for urban analysis. The approach also establishes a foundation for replicable mapping across other cities using minimal manual intervention.

In summary, the integration of transformer-based segmentation, regularization refinement, and spatial mapping demonstrates a robust pipeline for accurate and scalable urban imaging. These advancements offer meaningful contributions to geospatial intelligence, smart city planning, and sustainable development.

Future work will expand this pipeline to include rooftop height estimation and 3D visualization of the urban environment. Integrating elevation models with segmented roofs will enable the generation of realistic 3D city models, essential for evaluating solar panel feasibility, understanding building morphology, and enhancing decision-making processes in urban development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Hachem Saadaoui; Data curation, Saad Farah and Abdellatif Ghennioui; Funding acquisition, Hatim Lechgar; Methodology, Saad Farah; Project administration, Hachem Saadaoui and Hassan RHINANE; Resources, Hatim Lechgar; Software, Saad Farah; Supervision, Hassan RHINANE; Validation, Hachem Saadaoui, Hatim Lechgar and Abdellatif Ghennioui; Writing – original draft, Saad Farah; Writing – review & editing, Hachem Saadaoui and Hassan RHINANE.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used in this study, comprising Sentinel-2 satellite imagery and manually annotated rooftop segmentation masks for Ben Guerir City, Morocco, is not publicly available due to institutional and data-sharing restrictions. However, the data can be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request for academic and non-commercial use.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Green Energy Park (GEP) and Mohammed VI Polytechnic University (UM6P) for their technical support and access to computational resources. We also acknowledge the use of open-source libraries and platforms including Detectron2, Hugging Face Transformers, and Mapbox for visualization. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI GPT-4) for language enhancement and formatting assistance. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- P. Chaweewat, “Solar photovoltaic rooftop detection using satellite imagery and deep learning,” Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference, APPEEC, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Batchu, “Satellite Sunroof: High-res Digital Surface Models and Roof Segmentation for Global Solar Mapping,” Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Sariturk, D. Kumbasar, and D. Z. Seker, “Comparative Analysis of Different CNN Models for Building Segmentation from Satellite and UAV Images,” Photogramm Eng Remote Sensing, vol. 89, no. 2, pp. 97–105, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Lin et al., “A Dynamic Identification Algorithm for Large Urban Rooftop Solar Energy,” Chinese Control Conference, CCC, pp. 6363–6368, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. B. A. Gibril, R. Al-Ruzouq, J. Bolcek, A. Shanableh, and R. Jena, “Building Extraction from Satellite Images Using Mask R-CNN and Swin Transformer,” 34th International Conference Radioelektronika, RADIOELEKTRONIKA 2024 - Proceedings, pp. 1–5, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Vaswani et al., “Attention Is All You Need,” p. 1, Jun. 2017, Accessed: Jul. 07, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1706.03762.

- N. Carion, F. Massa, G. Synnaeve, N. Usunier, A. Kirillov, and S. Zagoruyko, “End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers,” Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), vol. 12346 LNCS, pp. 213–229, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Chetia, “Image Segmentation with transformers: An Overview, Challenges and Future,” Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Z. He, Y. Cai, H. He, X. Xian, and B. Barrett, “An Enhanced Trans-Involution Network for Building Footprint Extraction from High Resolution Orthoimagery,” International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), vol. 75, pp. 10030–10034, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhao, C. Persello, X. Lv, A. Stein, and M. Vergauwen, “Vectorizing planar roof structure from very high resolution remote sensing images using transformers,” Int J Digit Earth, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 1–15, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Q. Zhang, “Research of Land Surface Segmentation based on Convolutional Netword and Transformer Network,” 2022 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Mobile Networks and Wireless Communications, ICMNWC 2022, pp. 1–8, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Gan, “Research of Land Surface Segmentation based on Convolutional Netword and Transformer Network,” 2022 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Mobile Networks and Wireless Communications, ICMNWC 2022, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Saadaoui, A. Ghennioui, B. Ikken, H. Rhinane, and M. Maanan, “Using GIS and Photogrammetry for Assessing Solar Photovoltaic Potential on Flat Roofs in Urban Area Case of the City of Ben Guerir / Morocco,” ISPRS - International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, vol. 4212, no. 4/W12, pp. 155–166, Feb. 2019. [CrossRef]

- N. Rharbi and M. İNceoğlu, “Moroccan New Green Cities, Towards a Green Urban Transition,” Journal of Islamic Architecture, vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 296–305, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Rharbi and H. G. Demirkol, “Impact of Sustainability Transition in Moroccan Cities Identity: The Case of Benguerir,” Iconarp international journal architecture and planning, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 88–106, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. AZMI, C. S. TEKOUABOU KOUMETIO, E. B. DIOP, and J. Chenal, “Exploring the relationship between urban form and land surface temperature (LST) in a semi-arid region case study of Ben Guerir city - Morocco,” Environmental Challenges, vol. 5, p. 100229, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Rivet and A. Ben Mlih, “La articulación de la Administración Territorial del Protectorado francés en Marruecos,” Revista de Estudios Internacionales Mediterráneos, no. 9, p. 6, Dec. 2010. [CrossRef]

- N. Pal, S. Ramkrishna, H. Patil, N. Choudhary, and R. Soman, “TerraGrid: Harnessing Deep Learning Models for Satellite Image Segmentation,” Int J Comput Appl, vol. 186, no. 49, pp. 14–21, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Yuan, L. Lin, Q. Xin, Z. G. Zhou, and Q. Liu, “An Empirical Study on Data Augmentation for Pixel-Wise Satellite Image Time Series Classification and Cross-Year Adaptation,” IEEE J Sel Top Appl Earth Obs Remote Sens, vol. 18, pp. 1–18, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. A. A. Ghaffar, A. McKinstry, T. Maul, and T. T. Vu, “Data Augmentation Approaches for Satellite Image Super-Resolution,” ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, vol. 4, no. 2/W7, pp. 47–54, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Soujanya, Z. Alsalami, S. Srinath, J. Sengupta, and A. Das, “Rooftop Photovoltaic Panel Segmentation using Improved Mask Region-based Convolutional Neural Network,” 2nd IEEE International Conference on Data Science and Information System, ICDSIS 2024, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- N. Kolibarov, D. Wästberg, V. Naserentin, D. Petrova-Antonova, S. Ilieva, and A. Logg, “Roof Segmentation Towards Digital Twin Generation in LoD2+ Using Deep Learning,” Advances in Control and Optimization of Dynamical Systems, vol. 55, no. 11, pp. 173–178, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Amo-Boateng, N. Ekow Nkwa Sey, A. Ampah Amproche, and M. Kyereh Domfeh, “Instance segmentation scheme for roofs in rural areas based on Mask R-CNN,” The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 569–577, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Chen, L. Zhang, J. Li, and R. Liu, “Urban building roof segmentation from airborne lidar point clouds,” Journal of remote sensing, vol. 33, no. 20, pp. 6497–6515, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. Guo, J. Lu, D. Yu, X. Zhou, and Y. Lin, “A new approach for roof segmentation from airborne LiDAR point clouds,” Remote Sensing Letters, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 377–386, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Shi, K. N. Ngan, and S. Li, “Jaccard index compensation for object segmentation evaluation,” 2014 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, ICIP 2014, pp. 4457–4461, Oct. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Müller, I. Soto-Rey, and F. Kramer, “Towards a guideline for evaluation metrics in medical image segmentation,” BMC Res Notes, vol. 15, no. 1, Feb. 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Giraldo, “Precision, Recall and F1 score,” Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Maggiori, Y. Tarabalka, G. Charpiat, and P. Alliez, “Polygonization of remote sensing classification maps by mesh approximation,” Proceedings - International Conference on Image Processing, ICIP, vol. 2017-September, p. 5, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- N. Girard, D. Smirnov, J. Solomon, and Y. Tarabalka, “Polygonal Building Segmentation by Frame Field Learning,” ArXiv, pp. 1–30, Apr. 2020, Accessed: Jul. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2004.14875.

- M. R. Pettinati, “(PDF) The Role of Digital Generalization in Image Segmentation.” Accessed: Jul. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220913321_The_Role_of_Digital_Generalization_in_Image_Segmentation.

- S. Zorzi and F. Fraundorfer, “Regularization of Building Boundaries in Satellite Images using Adversarial and Regularized Losses,” pp. 5140–5143, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Castello, S. Roquette, M. Esguerra, A. Guerra, and J. L. Scartezzini, “Deep learning in the built environment: automatic detection of rooftop solar panels using Convolutional Neural Networks,” J Phys Conf Ser, vol. 1343, no. 1, p. 012034, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Qian et al., “Simultaneous extraction of spatial and attributional building information across large-scale urban landscapes from high-resolution satellite imagery,” Sustain Cities Soc, vol. 106, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).