Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Data Synthesis

3. Results

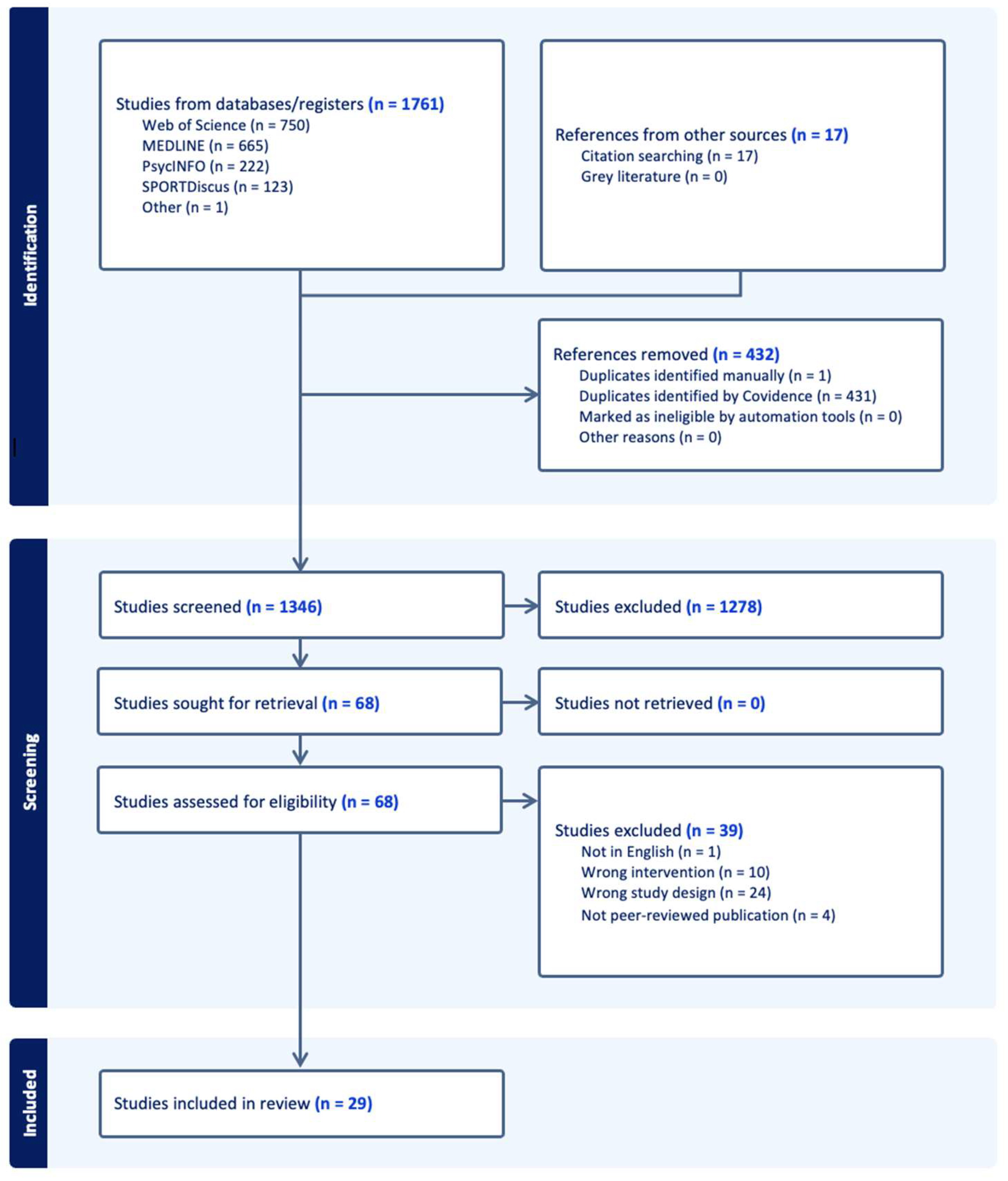

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Study and Participant Characteristics

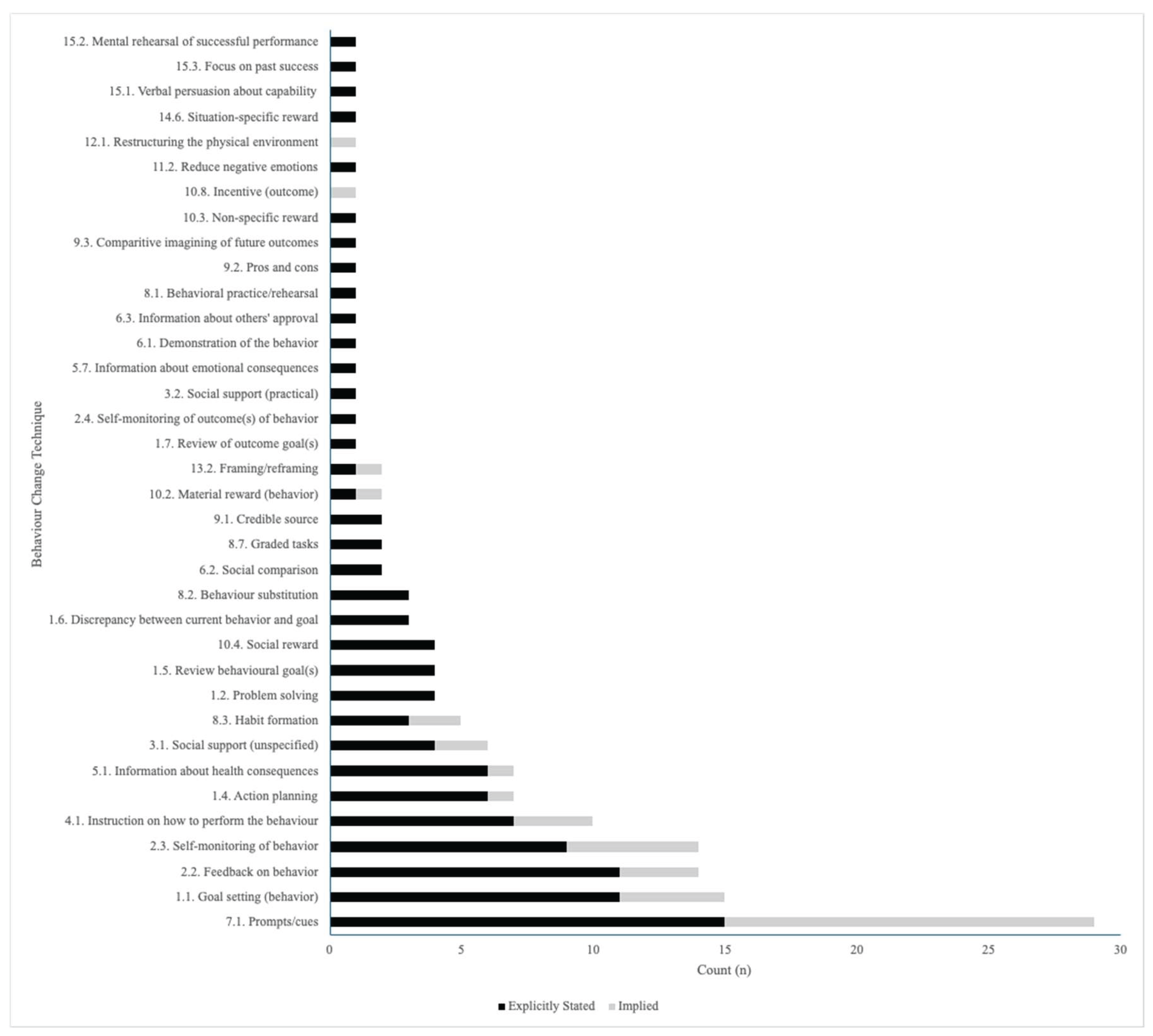

3.3. The Implementation of Behavior Change Theories and Techniques in PA JITAIs

3.4. JITAI Adaptive Algorithms

3.5. Changes in PA-Related Outcomes for JITAIs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| BCT | Behavior change technique |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| COM-B | Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behavior |

| JITAI | Just-in-time adaptive intervention |

| mERA | Mobile health evidence reporting and assessment |

| METs | Metabolic equivalents |

| mHealth | Mobile health |

| MVPA | Moderate-to-vigorous physical activty |

| PA | Physical activity |

Appendix A

| SECTION | ITEM | PRISMA-ScR CHECKLIST ITEM | REPORTED ON PAGE # |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 1-2 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 2 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | N/A |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 3 |

| Information sources* | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 2-4 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | Appendix B |

| Selection of sources of evidence† | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 2-4 |

| Data charting process‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | N/A |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 3 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence§ | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | N/A |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 3-4 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 4 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 4-5 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | N/A |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 5-10 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 5-10 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 10-12 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 12 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 12 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 12 |

Appendix B

| Search | Terms | Results |

| S1 | DE "Digital Health Resources" OR DE "Digital Interventions" OR DE "Mobile Phones" OR DE "Smartphones" OR DE "Mobile Health Applications" OR DE "Mobile Applications" OR DE "Mobile Health" OR DE "Mobile Devices" OR DE "Mobile Technology" OR DE "Wearable Devices" | 19,129 |

| S2 | TI (mhealth OR ehealth OR "digital health" OR “electronic health”) OR AB (mhealth OR ehealth OR "digital health" OR “electronic health”) OR KW (mhealth OR ehealth OR "digital health" OR “electronic health”) | 9,367 |

| S3 | TI ( ((cyber OR digital OR remote* OR distance* OR phone* OR internet OR “smart phone*” OR smartphone* OR mobile* OR iPhone* OR Android*) N5 (based OR app OR apps OR application* OR health OR intervention* OR delivery)) ) OR AB ( ((cyber OR digital OR remote* OR distance* OR phone* OR internet OR “smart phone*” OR smartphone* OR mobile* OR iPhone* OR Android*) N5 (based OR app OR apps OR application* OR health OR intervention* OR delivery)) ) OR KW ( ((cyber OR digital OR remote* OR distance* OR phone* OR internet OR “smart phone*” OR smartphone* OR mobile* OR iPhone* OR Android*) N5 (based OR app OR apps OR application* OR health OR intervention* OR delivery)) ) | 37,861 |

| S4 | TI ( (("activit* track*" OR "fitness track*" OR Fitbit OR Garmin OR TomTom OR Jawbone OR Withings OR “Apple Watch” OR smartwatch OR “smart watch” OR Amazfit OR “Google Pixel” OR “Galaxy Watch”)) ) OR AB ( (("activit* track*" OR "fitness track*" OR Fitbit OR Garmin OR TomTom OR Jawbone OR Withings OR “Apple Watch” OR smartwatch OR “smart watch” OR Amazfit OR “Google Pixel” OR “Galaxy Watch”)) ) OR KW ( (("activit* track*" OR "fitness track*" OR Fitbit OR Garmin OR TomTom OR Jawbone OR Withings OR “Apple Watch” OR smartwatch OR “smart watch” OR Amazfit OR “Google Pixel” OR “Galaxy Watch”)) ) | 1,197 |

| S5 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 | 53,154 |

| S6 | TI ( (("Just-in-time" OR “just in time” OR “just-in-time adaptive intervention*” OR JITAI OR “adaptive intervention*”) OR ("ecologic* momentary intervention*" OR EMI) OR (“experience sampling” OR “ambulatory assess*” OR “moment-to-moment measures” OR “daily diary” OR “repeat* assessment*” OR “ambulatory monitor*” OR “electronic diar*”) OR ("real time intervention*" OR "context* aware*" OR "context* trigger*" OR "context* tailor*" OR "dynamic tailor*" OR "real time tailor*" OR “real time intervention” OR “real time therapy” OR “real time tailor*” OR "sensor triggered" OR geofenc* OR "context* sens*" OR "real time context*" OR "persuasive technolog*" OR "sensing technolog*")) ) OR AB ( (("Just-in-time" OR “just in time” OR “just-in-time adaptive intervention*” OR JITAI OR “adaptive intervention*”) OR ("ecologic* momentary intervention*" OR EMI) OR (“experience sampling” OR “ambulatory assess*” OR “moment-to-moment measures” OR “daily diary” OR “repeat* assessment*” OR “ambulatory monitor*” OR “electronic diar*”) OR ("real time intervention*" OR "context* aware*" OR "context* trigger*" OR "context* tailor*" OR "dynamic tailor*" OR "real time tailor*" OR “real time intervention” OR “real time therapy” OR “real time tailor*” OR "sensor triggered" OR geofenc* OR "context* sens*" OR "real time context*" OR "persuasive technolog*" OR "sensing technolog*")) ) OR KW ( (("Just-in-time" OR “just in time” OR “just-in-time adaptive intervention*” OR JITAI OR “adaptive intervention*”) OR ("ecologic* momentary intervention*" OR EMI) OR (“experience sampling” OR “ambulatory assess*” OR “moment-to-moment measures” OR “daily diary” OR “repeat* assessment*” OR “ambulatory monitor*” OR “electronic diar*”) OR ("real time intervention*" OR "context* aware*" OR "context* trigger*" OR "context* tailor*" OR "real time tailor*" OR “real time intervention” OR “real time therapy” OR “real time tailor*” OR “dynamic tailor*” OR "sensor triggered" OR geofenc* OR "context* sens*" OR "real time context*" OR "persuasive technolog*" OR "sensing technolog*")) ) | 13,332 |

| S7 | TI ( ("daily life" or "real-time") N5 (intervention* OR aware* OR triggered OR tailor* OR sens* OR *measure* OR assessment* OR test* OR monitor*) ) OR AB (( ("daily life" or "real-time") N5 (intervention* OR aware* OR triggered OR tailor* OR sens* OR *measure* OR assessment* OR test* OR monitor*) ) OR KW ( ("daily life" or "real-time") N5 (intervention* OR aware* OR triggered OR tailor* OR sens* OR *measure* OR assessment* OR test* OR monitor*) ) | 4,540 |

| S8 | S6 OR S7 | 17,375 |

| S9 | DE "Physical Fitness" OR DE "Aerobic Exercise" OR DE "Running" OR DE "Walking" OR DE "Physical Activity" OR DE "Weightlifting" OR DE "Exercise" OR DE "Locomotion" OR DE “Active Living” | 78,438 |

| S10 | TI (“ physical activit*” OR "physical training" OR walk* OR exercis* OR fitness OR "physical fitness*" OR aerobics OR "aerobic* training" OR "aerobic* activit*" OR running OR jogging OR athletics OR cycling OR bike* OR biking OR bicycl* OR swim* OR hiking OR rollerblading OR roller-blading OR rollerskat* OR roller-skat* OR skating OR "physical exertion*" OR "active transport*" OR "circuit training" OR "strength training" OR calisthenics OR sport* OR "resistance training" OR "weight training" OR "endurance training" OR sport* OR pilates OR yoga) OR AB (“ physical activit*” OR "physical training" OR walk* OR exercis* OR fitness OR "physical fitness*" OR aerobics OR "aerobic* training" OR "aerobic* activit*" OR running OR jogging OR athletics OR cycling OR bike* OR biking OR bicycl* OR swim* OR hiking OR rollerblading OR roller-blading OR rollerskat* OR roller-skat* OR skating OR "physical exertion*" OR "active transport*" OR "circuit training" OR "strength training" OR calisthenics OR sport* OR "resistance training" OR "weight training" OR "endurance training" OR sport* OR pilates OR yoga) OR KW (“ physical activit*” OR "physical training" OR walk* OR exercis* OR fitness OR "physical fitness*" OR aerobics OR "aerobic* training" OR "aerobic* activit*" OR running OR jogging OR athletics OR cycling OR bike* OR biking OR bicycl* OR swim* OR hiking OR rollerblading OR roller-blading OR rollerskat* OR roller-skat* OR skating OR "physical exertion*" OR "active transport*" OR "circuit training" OR "strength training" OR calisthenics OR sport* OR "resistance training" OR "weight training" OR "endurance training" OR sport* OR pilates OR yoga) | 239,890 |

| S11 | S9 OR S10 | 249,104 |

| S12 | S5 AND S8 AND S11 | 222 |

Appendix C

| Author and Year | Location | Design | Sample Size | Participant Characteristics | Behavior Change Theory | BCTs | JITAI Description |

| Bardus et al., 2018 [33] | Lebanon | Protocol | Recruitment has not commenced | Healthy adult employees of an Academic Institution | Not Stated | Self-monitoring of behavior*, Goal setting (behavior)*, Feedback on behavior*, Social reward*, Social support* | Mobile coach that provides interactive counselling and feedback based on several outcomes |

| Boerema et al., 2019 [45] | The Netherlands | Quasi-experimental | n=14 | 50+ year old office workers who spend 50% of their time or more at a computer | Not Stated | Prompts/cues, Goal setting (behavior), Feedback on behavior | Focuses on reducing sedentary behavior with periodic prompts |

| Carey et al., 2024 [68] | United States | Protocol | n=196 | 18-to-75-year-olds with a traumatic SCI injury at C5 and below who are 6 months+ post injury and use a wheelchair as their primary means of transportation | COM-B Model | Goal setting (behavior)*, Feedback on behavior*, Prompts/cues*, | Microrandomized feedback prompts and activity recommendations |

| Coppens et al., 2024 [13,56] | Belgium | Randomized Controlled Trial | n=25 | Healthy, inactive adults | Self-Determination Theory | Prompts/cues*, Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Uses machine learning for personalized activity suggestions |

| Daryabeygi-Khotbehsara et al., 2023 [56] | Australia | Protocol | Recruitment has not commenced | Adults between 35 and 65 years old with Type II Diabetes | Not Stated | Behavior substitution*, Social support*, Problem-solving*, Instruction on how to perform the behavior*, Information about health consequences*, Prompts/cues*, Goal setting (behavior), Self-monitoring of behavior, Feedback on behavior* | Notifications to encourage either sedentary interruption or movement. |

| Ding et al., 2016 [46] | United States | Feasibility Trial | Total n=16, Control n=7, Intervention n=9 |

College students | Fogg Behavior Model, Locke and Latham’s Goal Setting Theory, Trans-theoretical Model | Goal setting (behavior)*, Prompts/cues* | Reminders were sent when participants overused their smartphone, were sedentary for extended periods, were walking (to encourage more walking), or had just finished a meal |

| Fiedler et al., 2023 [47] | Germany | Randomized Controlled Trial | n=80 | Families including at least one parent and at least one child who was 10 years of age or older and who were living together in a common household | Self-Determination Theory | Goal setting (behavior)*, Prompts/cues*, Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Notifications to disrupt bouts of sedentary behavior (50/60 minutes of the last hour). |

| Golbus et al., 2024a [32] | United States | Development Study | n=108 | Adults 18 to 75 years old enrolled in cardiac rehabilitation | Not Stated | Goal setting (behavior), Self-monitoring of behavior, Prompts/cues | Physical activity notifications are designed to disrupt sedentary behavior (eg, to stand up or stretch) and to encourage lowlevel physical activity (eg, bouts of 250 to 500 steps). |

| Golbus et al., 2024b [34] | United States | Microrandomized Trial | Recruitment has not commenced | Adults with self-reported hypertension and no contradictions to PA or a low-sodium diet | Not Stated | Goal setting (behavior)*, Prompts/cues*, Visualizations*, Feedback on behavior* | Static component (e.g., a mobile application that allowed for goal setting and activity tracking) and a dynamic component that consisted of micro-randomized text messages. |

| Hietbrink et al., 2023 [36] | Netherlands | Development Study |

n=9 | Adults with Type II Diabetes | HAPA model, Rothman’s Theory, Marlatt’s Relapse Prevention Theory | Goal-setting (behavior)*, Problem solving*, Action planning*, Review behavior goal*, Feedback on behavior*, Self-monitoring of behavior*, Self-monitoring of outcomes of behavior*, social support*, Social support (practical)*, Instruction on how to perform the behavior*, Information about health consequences*, Information about emotional consequences*, Information about others’ approval*, Prompts/cues*, Habit formation*, Credible source*, Pros and cons*, Comparative imagining of future outcomes*, Reduce negative emotions*, Framing and reframing*, Verbal persuasion about capability*, Focus on past success* | 425 motivational messages, consisting of content for each of the tailoring variables. Decision points took place at 2 semirandom times per day. |

| Hiremath et al., 2019 [48] | United States | Pilot Study | n=16 | Adults 18 to 65 years old with an SCI who are 6 months+ post injury and use a wheelchair as their primary means of transportation | Social Cognitive Theory | Self-monitoring of behavior, Feedback on behavior, Goal setting (behavior), Instruction on how to perform the behavior | Provided proactive, near-real-time feedback via smartphone (audio/vibration, based on user preference) and smartwatch (vibration) when participants engaged in moderate or higher intensity physical activity |

| Hojjatnia et al., 2021 [69] | United States | Quasi-Experimental | n=45 | Insufficiently active emerging and young adults (18-29 years old) | Not stated | Prompts/cues | Messages were sourced from three libraries (move more, sit less, inspirational quotes). Smartphone location data were used to retrieve local weather at message delivery. System identification and simulations evaluated responses to each message type under varying conditions, with extracted features summarizing dynamic response patterns. |

| Ismail et al., 2022 [49] | Qatar | Quasi-Experimental | Total n=58, Control n=29, Intervention n=29 |

Sedentary adult employees aged 23 to 39 years old | Not Stated | Prompts/cues, Material reward (behavior), Self-monitoring (behavior) | Personalized prompts that include user information, user goals, daily routine, and the surrounding environment |

| Klasnja et al., 2019 [50] | United States | Microrandomized Trial | n=44 | 18- to 60-year-old adults with a. regular schedule outside the home (employed or a student) | Not Stated | Prompts/cues, Self-monitoring of behavior | Contextually tailored activity suggestions to walk (intended to encourage bouts of 500-1000 steps) and suggestions to disrupt sedentary behavior (to stand up, stretch, and/or move around). |

| Kramer et al., 2019 [39] | Switzerland | Protocol | n=274 | Healthy adults not working night shifts | Not Stated | Problem solving*, Action planning*, Discrepancy between current behavior and goal*, Feedback on behavior*, Instruction on how to perform the behavior*, Material reward (behavior)*, Nonspecific reward*, Self-monitoring of behavior*, Prompts/cues* | Sent out intervention and step goal–related notifications at random points in time but within prespecified time windows that guaranteed delivery at appropriate times |

| Low et al., 2023 [51] | United States | Pilot Study | Total n=26, Control n=13, Intervention n=13 |

Patients scheduled for surgery for metastatic gastrointestinal cancer | Not Stated | Prompts/cues | Real-time mobile intervention that detects prolonged sedentary behavior during the perioperative period and delivers walking prompts tailored to daily self-reported symptoms |

| Mair et al., 2023 [41] | Singapore | Feasibility Study | n=31 | Older adults who use a smartphone | COM-B Model | Goal setting (behavior)*, Action Planning*, Prompts/cues*, Self-monitoring of behavior*, Feedback on behavior* | Personalized PA messaging was delivered by the JitaBug app to encourage participants to meet their daily PA goal. Messages were tailored to participants’ context. |

| Novak et al., 2024 [70] | Czech Republic | Development | n=14 | Adults with prediabetes | Self-regulation theory | Prompts/cues*, Habit formation*, Behavior substitution*, Review behavior goal*, Discrepancy between current behavior and goal*, Feedback on behavior*, Social reward*, Action planning*, Information about health consequences* | "Walk faster" notifications while walking and "stand up" notifications after prolonged sitting |

| Park et al., 2023 [57] | United States | Protocol | n=48 | Inactive adults aged 25 years or older | Social Cognitive Theory | Prompts/cues*, Goal setting (beahvior)*, Feedback on behavior* | |

| Pellegrini et al., 2021 [42] | United States | Feasibility Study | n=8 | Adults aged 21 to 70 years old with Type II Diabetes | Not Stated | Prompts/cues* | Using an external accelerometer (Shimmer), when a person is sedentary for >= 20 mins, they received a prompt to engage in light behavior for 2 mins |

| Rabbi et al., 2015 [52] | United States | Randomized Controlled Trial | Total n=17, Control n=8, Intervention n=9 |

Low to moderately active adults | Learning theory, social cognitive theory, Fogg's behavioral model | Self-monitoring of behavior, Prompts/cues | Used auto/manual logging of activity, location, and food; analyzed logs to detect behavior patterns; applied multi-armed bandit algorithm to deliver personalized suggestions (continue, avoid, or modify behaviors) |

| Sporrel et al., 2022 [40] | The Netherlands | Feasibility Study | Total n=20, Basic Intervention n=9, Smart Intervention n=11 |

Adults aged 18 to 55 years old who would like to become more active | Fogg's Behavioral Model | Goal setting (behavior)*, Review behavioral goals*, Self-monitoring of behavior*, Instruction on how to perform the behavior*, Demonstration of the behavior*, Behavioral practice/rehearsal*, Graded tasks*, Situation-specific reward*, Prompts/cues | Compared two app versions: Basic PAUL (random-timed JIT prompts) vs. Smart PAUL (JIT adaptive prompts for walking/running). |

| Thomas & Bond, 2015 [53] | United States | Quasi-experimental | n=30 | Overweight or obese men and women aged 21 to 70 years old | None reported | Prompts/cues | Three conditions: (1) 3-min break after 30 min sedentary; (2) 6-min break after 60 min; (3) 12-min break after 120 min. |

| van Dantzig et al., 2013 [43] | The Netherlands | Pilot Study | Total n=86, Control n=46, Intervention n=40 |

Healthy adult office workers | Social influence strategies defined by Cialdini. | Prompts/cues*, Goal setting (behavior), Feedback on the behavior, Social support, Habit formation | Not stated |

| Vandelanotte et al., 2023 [14] | Australia | Development Study | Recruitment has not commenced | Adults interested in becoming more physically active | Self-Determination Theory | Social support (unspecified), Information about health consequences, Action planning, Habit formation, Restructuring the physical environment, Incentive (outcome), Framing/ reframing, Prompts/cues | (1) NLP-based conversations to increase activity knowledge; (2) reinforcement learning-driven nudge engine using real-time data (activity, GPS, GIS, weather, user input); (3) generative AI Q&A for physical activity support. |

| Vetrovsky et al., 2023 [37] | Czech Republic | Protocol | Recruitment has not commenced | Adults aged 18 or older with a diagnosis of Prediabetes or Type II Diabetes according to Czech guidelines | Not Stated | Credible source*, Instruction on how to perform the behavior*, Action planning*, Information about health consequences*, Graded tasks*, Goal setting (behavior)*, Self-monitoring of behavior*, Prompts/cues*, Habit formation*, Behavior substitution*, Review behavioral goals*, Discrepancy between current behavior and goal*, Feedback on behavior*, Social reward*, Information about health consequences*, Problem solving*, Social support (unspecified)*, Graded tasks* | Just-in-time prompts to increase walking pace were triggered when the patient is walking for 5 consecutive minutes with an average steps per minute ranging between 60-100. Just-in-time prompts to interrupt sitting were sent when the patient sits for more than 30 min. |

| Vos et al., 2023 [38] | The Netherlands | Pilot Study | n=11 | Adults aged 45 years or older | Social Cognitive Theory | Action planning*, Social reward*, Feedback on behavior*, Social comparison*, Information about health consequences*, Instruction on how to perform the behavior*, Goal setting (behavior)*, Self-monitoring of behavior*, Review of outcome goals*, Prompts/cues | Not stated |

| Wang et al., 2021 [71] | The Netherlands | Feasibility Study | n=7 | Adults struggling to maintaining a healthy activity level who would like to be more physically active |

Behavior change wheel | Prompts/cues* | The reinforcement learning model would track user data and take input from physical activity logs to determine if it was the right time to send a prompt |

| Wunsch et al., 2024 [54] | Germany | Randomized Controlled Trial | Total n=156, Control n=68, Intervention n=88 |

Households comprising at least 1 adult caregiver and 1 child aged >10 years residing together |

Not stated | Goal setting (behavior)*, Feedback on behavior*, Self-monitoring of behavior*, Instruction on how to perform the behavior, Social comparison*, Prompts/cues | Not stated |

References

- World Health Organization, “Noncommunicable diseases,” World Health Organization. Accessed: May 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases.

- E. Anderson and J. L. Durstine, “Physical activity, exercise, and chronic diseases: A brief review,” Sports Medicine and Health Science, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 3–10, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization, “Nearly 1.8 billion adults at risk of disease from not doing enough physical activity,” World Health Organization. Accessed: May 28, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/26-06-2024-nearly-1.8-billion-adults-at-risk-of-disease-from-not-doing-enough-physical-activity.

- A. O’Regan et al., “How to improve recruitment, sustainability and scalability in physical activity programmes for adults aged 50 years and older: A qualitative study of key stakeholder perspectives,” PLoS One, vol. 15, no. 10, p. e0240974, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. G. Gavarkovs, S. M. Burke, and R. J. Petrella, “The Physical Activity–Related Barriers and Facilitators Perceived by Men Living in Rural Communities,” Am J Mens Health, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 1130–1132, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Gill, “How Many People Own Smartphones in the World? (2024-2029),” Priori Data.

- M. Zhang, W. Wang, M. Li, H. Sheng, and Y. Zhai, “Efficacy of Mobile Health Applications to Improve Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis for Physically Inactive Individuals,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 19, no. 8, p. 4905, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Spruijt-Metz et al., “Innovations in the Use of Interactive Technology to Support Weight Management,” Curr Obes Rep, vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 510–519, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang and L. C. Miller, “Just-in-the-Moment Adaptive Interventions (JITAI): A Meta-Analytical Review,” Health Commun, vol. 35, no. 12, pp. 1531–1544, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. Davis, R. Campbell, Z. Hildon, L. Hobbs, and S. Michie, “Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review,” Health Psychol Rev, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 323–344, Aug. 2015. [CrossRef]

- E. L. Deci and R. M. Ryan, “Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Springer Science & Business Media,” 1985.

- R. M. Ryan and E. L. Deci, “Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being.,” American Psychologist, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 68–78, 2000. [CrossRef]

- A. Bandura, “Social cognitive theory of self-regulation,” Organ Behav Hum Decis Process, vol. 50, no. 2, pp. 248–287, Dec. 1991. [CrossRef]

- S. Michie, C. Abraham, M. P. Eccles, J. J. Francis, W. Hardeman, and M. Johnston, “Strengthening evaluation and implementation by specifying components of behaviour change interventions: a study protocol,” Implementation Science, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 10, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- W. Hardeman, J. Houghton, K. Lane, A. Jones, and F. Naughton, “A systematic review of just-in-time adaptive interventions (JITAIs) to promote physical activity,” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 31, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- I. Coppens, T. De Pessemier, and L. Martens, “Exploring the added effect of three recommender system techniques in mobile health interventions for physical activity: a longitudinal randomized controlled trial,” User Model User-adapt Interact, vol. 34, no. 5, pp. 1835–1890, Nov. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Vandelanotte et al., “Increasing physical activity using an just-in-time adaptive digital assistant supported by machine learning: A novel approach for hyper-personalised mHealth interventions,” J Biomed Inform, vol. 144, p. 104435, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. McGowan et al., “Reporting scoping reviews—PRISMA ScR extension,” J Clin Epidemiol, vol. 123, pp. 177–179, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Babineau, “Product Review: Covidence (Systematic Review Software),” Journal of the Canadian Health Libraries Association / Journal de l’Association des bibliothèques de la santé du Canada, vol. 35, no. 2, p. 68, Aug. 2014. [CrossRef]

- P. Cotie, A. Willms, and S. Liu, “Implementation of Behavior Change Theories and Techniques for Physical Activity Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions: A Scoping Review,” 2025.

- S. Michie et al., “The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions,” Annals of Behavioral Medicine, vol. 46, no. 1, pp. 81–95, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. C. Bohlen et al., “Do Combinations of Behavior Change Techniques That Occur Frequently in Interventions Reflect Underlying Theory?,” Ann Behav Med, vol. 54, no. 11, pp. 827–842, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- A. Bandura, “Social foundations of thought and action,” Englewood Cliffs, NJ, vol. 1986, no. 23–28, p. 2, 1986.

- B. J. Fogg, “A behavior model for persuasive design,” in Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Persuasive Technology, in Persuasive ’09. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, Apr. 2009, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- S. Michie, M. M. Van Stralen, and R. West, “The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions,” Implementation Science, vol. 6, no. 1, p. 42, Dec. 2011. [CrossRef]

- R. Cialdini, Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade. Simon & Schuster, 2016.

- R. Schwarzer, “Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) as a Theoretical Framework to Understand Behavior Change,” Actualidades en Psicología, vol. 30, no. 121, p. 119, Dec. 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. Bandura, Social learning theory. Oxford, England: Prentice-Hall, 1977.

- M. E. Larimer, R. S. Palmer, and G. A. Marlatt, “Relapse prevention. An overview of Marlatt’s cognitive-behavioral model.,” Alcohol Res Health, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 151–60, 1999.

- J. O. Prochaska, C. A. Redding, and K. E. Evers, “The transtheoretical model and stages of change,” Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice, vol. 4, pp. 97–121, 2008.

- A. J. Rothman, “Toward a theory-based analysis of behavioral maintenance.,” Health Psychology, vol. 19, no. 1, Suppl, pp. 64–69, Jan. 2000. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Golbus et al., “A Physical Activity and Diet Just-in-Time Adaptive Intervention to Reduce Blood Pressure: The myBPmyLife Study Rationale and Design,” J Am Heart Assoc, vol. 13, no. 2, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Bardus, G. Hamadeh, B. Hayek, and R. Al Kherfan, “A Self-Directed Mobile Intervention (WaznApp) to Promote Weight Control Among Employees at a Lebanese University: Protocol for a Feasibility Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial,” JMIR Res Protoc, vol. 7, no. 5, p. e133, May 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Golbus et al., “Text Messages to Promote Physical Activity in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: A Micro-Randomized Trial of a Just-In-Time Adaptive Intervention,” Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes, vol. 17, no. 7, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Daryabeygi-Khotbehsara, D. W. Dunstan, S. M. S. Islam, Y. Zhang, M. Abdelrazek, and R. Maddison, “Just-In-Time Adaptive Intervention to Sit Less and Move More in People With Type 2 Diabetes: Protocol for a Microrandomized Trial,” JMIR Res Protoc, vol. 12, p. e41502, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. A. G. Hietbrink et al., “A Digital Lifestyle Coach (E-Supporter 1.0) to Support People With Type 2 Diabetes: Participatory Development Study,” JMIR Hum Factors, vol. 10, p. e40017, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Vetrovsky et al., “mHealth intervention delivered in general practice to increase physical activity and reduce sedentary behaviour of patients with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes (ENERGISED): rationale and study protocol for a pragmatic randomised controlled trial,” BMC Public Health, vol. 23, no. 1, p. 613, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Vos, G.-J. de Bruijn, M. C. A. Klein, J. Lakerveld, S. C. Boerman, and E. G. Smit, “SNapp, a Tailored Smartphone App Intervention to Promote Walking in Adults of Low Socioeconomic Position: Development and Qualitative Pilot Study,” JMIR Form Res, vol. 7, p. e40851, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J.-N. Kramer et al., “Investigating Intervention Components and Exploring States of Receptivity for a Smartphone App to Promote Physical Activity: Protocol of a Microrandomized Trial,” JMIR Res Protoc, vol. 8, no. 1, p. e11540, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Sporrel et al., “Just-in-Time Prompts for Running, Walking, and Performing Strength Exercises in the Built Environment: 4-Week Randomized Feasibility Study,” JMIR Form Res, vol. 6, no. 8, p. e35268, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. L. Mair, L. D. Hayes, A. K. Campbell, D. S. Buchan, C. Easton, and N. Sculthorpe, “A Personalized Smartphone-Delivered Just-in-time Adaptive Intervention (JitaBug) to Increase Physical Activity in Older Adults: Mixed Methods Feasibility Study,” JMIR Form Res, vol. 6, no. 4, p. e34662, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Pellegrini, S. A. Hoffman, E. R. Daly, M. Murillo, G. Iakovlev, and B. Spring, “Acceptability of smartphone technology to interrupt sedentary time in adults with diabetes,” Transl Behav Med, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 307–314, Sep. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. van Dantzig, G. Geleijnse, and A. T. van Halteren, “Toward a persuasive mobile application to reduce sedentary behavior,” Pers Ubiquitous Comput, vol. 17, no. 6, pp. 1237–1246, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- T. C. Hsu, P. Whelan, J. Gandrup, C. J. Armitage, L. Cordingley, and J. McBeth, “Personalized interventions for behaviour change: A scoping review of just-in-time adaptive interventions,” Br J Health Psychol, vol. 30, no. 1, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Boerema, L. van Velsen, and H. Hermens, “An intervention study to assess potential effect and user experience of an mHealth intervention to reduce sedentary behaviour among older office workers,” BMJ Health Care Inform, vol. 26, no. 1, p. e100014, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- X. Ding, J. Xu, H. Wang, G. Chen, H. Thind, and Y. Zhang, “WalkMore: promoting walking with just-in-time context-aware prompts,” in 2016 IEEE Wireless Health (WH), IEEE, Oct. 2016, pp. 1–8. [CrossRef]

- J. Fiedler, C. Seiferth, T. Eckert, A. Woll, and K. Wunsch, “A just-in-time adaptive intervention to enhance physical activity in the SMARTFAMILY2.0 trial.,” Sport Exerc Perform Psychol, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 43–57, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. V. Hiremath et al., “Mobile health-based physical activity intervention for individuals with spinal cord injury in the community: A pilot study,” PLoS One, vol. 14, no. 10, p. e0223762, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Ismail and D. Al Thani, “Design and Evaluation of a Just-in-Time Adaptive Intervention (JITAI) to Reduce Sedentary Behavior at Work: Experimental Study,” JMIR Form Res, vol. 6, no. 1, p. e34309, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Klasnja et al., “Efficacy of Contextually Tailored Suggestions for Physical Activity: A Micro-randomized Optimization Trial of HeartSteps,” Annals of Behavioral Medicine, vol. 53, no. 6, pp. 573–582, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. A. Low et al., “A Real-Time Mobile Intervention to Reduce Sedentary Behavior Before and After Cancer Surgery: Usability and Feasibility Study,” JMIR Perioper Med, vol. 3, no. 1, p. e17292, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Rabbi, A. Pfammatter, M. Zhang, B. Spring, and T. Choudhury, “Automated Personalized Feedback for Physical Activity and Dietary Behavior Change With Mobile Phones: A Randomized Controlled Trial on Adults,” JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, vol. 3, no. 2, p. e42, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. G. Thomas and D. S. Bond, “Behavioral response to a just-in-time adaptive intervention (JITAI) to reduce sedentary behavior in obese adults: Implications for JITAI optimization.,” Health Psychology, vol. 34, no. Suppl, pp. 1261–1267, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Wunsch, J. Fiedler, S. Hubenschmid, H. Reiterer, B. Renner, and A. Woll, “An mHealth Intervention Promoting Physical Activity and Healthy Eating in a Family Setting (SMARTFAMILY): Randomized Controlled Trial,” JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, vol. 12, p. e51201, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. E. Rhodes, “Multi-Process Action Control in Physical Activity: A Primer,” Front Psychol, vol. 12, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Daryabeygi-Khotbehsara, D. W. Dunstan, S. M. S. Islam, Y. Zhang, M. Abdelrazek, and R. Maddison, “Just-In-Time Adaptive Intervention to Sit Less and Move More in People With Type 2 Diabetes: Protocol for a Microrandomized Trial,” JMIR Res Protoc, vol. 12, p. e41502, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Park et al., “Advancing Understanding of Just-in-Time States for Supporting Physical Activity (Project JustWalk JITAI): Protocol for a System ID Study of Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions,” JMIR Res Protoc, vol. 12, p. e52161, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Gardner, P. Lally, and J. Wardle, “Making health habitual: the psychology of ‘habit-formation’ and general practice,” British Journal of General Practice, vol. 62, no. 605, pp. 664–666, Dec. 2012. [CrossRef]

- E. J. Mascha and T. R. Vetter, “Significance, Errors, Power, and Sample Size: The Blocking and Tackling of Statistics,” Anesth Analg, vol. 126, no. 2, pp. 691–698, Feb. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Hollman, S. Liu, M. Davenport, and R. E. Rhodes, “A critical review and user’s guide for conducting feasibility and pilot studies in the physical activity domain.,” Sport Exerc Perform Psychol, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 40–56, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Willms, R. E. Rhodes, and S. Liu, “The Development of a Hypertension Prevention and Financial-Incentive mHealth Program Using a ‘No-Code’ Mobile App Builder: Development and Usability Study,” JMIR Form Res, vol. 7, p. e43823, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Willms, R. E. Rhodes, and S. Liu, “Effects of Mobile-Based Financial Incentive Interventions for Adults at Risk of Developing Hypertension: Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial,” JMIR Form Res, vol. 7, p. e36562, Mar. 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Willms and S. Liu, “Exploring the Feasibility of Using ChatGPT to Create Just-in-Time Adaptive Physical Activity mHealth Intervention Content: Case Study,” JMIR Med Educ, vol. 10, p. e51426, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Haag et al., “The Last JITAI? The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Large Language Models in Issuing Just-in-Time Adaptive Interventions: Fostering Physical Activity in a Prospective Cardiac Rehabilitation Setting,” Pre-Print, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Agarwal et al., “Guidelines for reporting of health interventions using mobile phones: mobile health (mHealth) evidence reporting and assessment (mERA) checklist,” BMJ, p. i1174, Mar. 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Liu, H. La, A. Willms, and R. E. Rhodes, “A ‘No-Code’ App Design Platform for Mobile Health Research: Development and Usability Study,” JMIR Form Res, vol. 6, no. 8, p. e38737, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Willms, J. Rush, S. Hofer, R. E. Rhodes, and S. Liu, “Advancing physical activity research methods using real-time and adaptive technology: A scoping review of ‘no-code’ mobile health app research tools.,” Sport Exerc Perform Psychol, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

| Author, Year | PA Outcome | PA Measurement Tool | Length | Significant Results | Comparator |

| Boerema et al., 2019 [45] | PA Intensity | ProMove 3D Activity Sensor | 1 week | No significant PA results | Baseline |

| Ding et al., 2016 [46] | Weekly Steps | Smartphone and Smartwatch Accelerometers | 3 weeks | No significant PA results | Between-Group |

| Fiedler et al., 2023 [47] | Step Count, METs | Move 3/Move 4, or Movisens GmbH Accelerometer | 3 weeks | Increased step count in “engaged” condition vs “not engaged” (Δ: +256 steps) | Within-Person |

| Golbus, Shi, et al., 2024 [34] | Step Count | iPhone or Android Phone and Apple Watch Series 4 or Fitbit Versa 2 | 6 months | Increased step count in Fitbit group during initiation phase only (Δ: +17%) | Within-Person |

| Hiremath et al., 2019 [48] | Energy Expenditure (kcal) and Light PA time, MVPA time | Nexus 5 or 5X Smartphone, LG-Urbane Smartwatch, PanoBike Wheel Rotation Monitor | 3 months | No significant PA results | Within-Person |

| Ismail et al., 2022 [49] | Step Count, METs | Android Smartphone | 66 days | No significant PA results | Between-Group |

| Klasnja et al., 2019 [50] | Steps | Android Smartphone, Jawbone Smartwatch | 6 weeks | No significant PA results | Within-Person |

| Low et al., 2023 [51] | Step Count | Fitbit Versa Smartwatch, Google Pixel 2 Smartphone | Varied based on surgery and discharge dates. | No significant PA results | Within-Person |

| Pellegrini et al., 2021 [42] | % of Time Doing Light PA or MVPA | Shimmer, Intervention Accelerometer | 1 month | Increased Light PA (Δ: +7.8%) | Within-Person |

| Rabbi et al., 2015 [52] | Minutes per Day Walking | Self-Report | 3 weeks | Increased MVPA (Δ: +10.4 mins/day) | Between-Group |

| Sporrel et al., 2022 [40,53] | Minutes of Behavior | Actigraph Accelerometer | 4 weeks | No significant PA results | Between-Group, then Within-Person |

| Thomas & Bond, 2015 [53] |

Walking Time | SenseWear Mini Armband | 3 weeks | 3-min condition (Δ: +31 min/day), had a greater increase in Light PA compared to 12-min (Δ: +15.3 min/day) | Between-Group |

| van Dantzig et al., 2013 - Study 2 [43] | Proportion of Active Minutes | Accelerometer | 6 weeks | No significant PA results | Between-Group |

| Wunsch et al., 2024 [54] | Steps/Week, MVPA Time/Week | Move 3, Move 4, or Movisens Accelerometer | 3 weeks | No significant PA results | Between-Group |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).