1. Introduction

Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) is an arbovirus transmitted by mosquitoes that causes severe disease outbreaks affecting humans and livestock in sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East and the Indian Ocean islands [

1]. Seasons of heavy rainfall favours the overgrowth of mosquito species capable of trans-ovarial transmission of the virus, which is associated with outbreaks in endemic countries. RVFV or

phlebovirus riftense (fam.

Phenuiviridae, class

Bunyaviricetes) is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus with a tri-segmented genome of negative and ambisense polarity [

2,

3]. Despite the available effective RVF vaccines in Africa, the often hard-to-predict nature of RVF outbreaks after long inter-epizootic periods makes it difficult to establish annual vaccination programs [

4,

5]. A potential strategy to overcome this problem would be the use of multivalent vaccines, which could provide immunity against a prevailing disease for which vaccination is obligatory, while immunizing against other diseases of a more sporadic nature.

Peste des petits ruminants virus (PPRV) is a Morbillivirus into the

Paramyxoviridae family that mainly affects domestic and wild ruminants. PPRV is the etiological agent of peste des petits ruminants (PPR or goat plague), a disease that causes substantial economic losses, with greater consequences in developing countries across Africa, the Middle East and Asia where it is considered to be endemic. Mass vaccination is considered an effective way to control the spread of the disease as it was proven during the 2009-2011 campaigns in Morocco [

6] that kept the virus unseen until June 2015. Currently, live attenuated PPR vaccines are being used in endemic regions [

7] and inactivated vaccines in the rest of the countries[

8]. Live-attenuated PPR vaccines induce a high level of protection for at least three years [

9] but they have the risk of reversion to virulence. On the other hand, inactivated vaccines are a safer choice, but they do not induce an immunity as good as live attenuated vaccines. Therefore, the development of improved vaccines, safe and with DIVA properties (differentiation of infected from vaccinated animals) is a necessary step to improve the quality of the prophylactic measures. The development of DIVA vaccines would also facilitate the global PPR eradication program launched by the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH, former OIE) in 2014. Vectored vaccines are perfect for the development of DIVA strategies. In the case of PPRV there are already several recombinant viral vectors, either poxvirus, herpesvirus or adenovirus, that express PPRV proteins and can induce immunity and protection [

10,

11,

12]. Besides these well-established vaccine platforms, RVFV can also be engineered to support the expression of foreign antigens [

13]. Previously, we also demonstrated that recombinant RVFV can express bluetongue virus antigens [

14] that were able to elicit specific and protective immune responses in vivo.

In this work, we have reverse engineered two recombinant RVFVs expressing either the PPRV hemagglutinin (H) or the fusion (F) proteins. The expression of both proteins was able to induce an immune response in mice and sheep to levels that correlate with protection [

15,

16]. We therefore advocate the use of RVFV vectored vaccines as a novel strategy to provide simultaneous immunity against PPR and RVF. The main benefit of using RVFV as a viral vaccine vector is that it could provide protection against RVF and other ruminant diseases, including peste des petits ruminants, a very appealing strategy, particularly in the context of the current OIE and FAO global eradication plan for PPR. This could be seen as a good test to provide immunity against an endemic illness such as PPR while keeping animals protected against the unpredictable outbreaks of RVF.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cells

The cell lines used for this study were HEK293T (human embryonic kidney 293 cells, ATCC CRL-3216), Vero (African green monkey kidney cells, ATCC CCL-81) and BHK-21 (baby hamster kidney fibroblasts, ATCC CCL-10). Vero dog SLAM cells (VDS) cells had been kindly provided by Dr S. Parida (IAH, Pirbright, UK). All cell lines were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% 100X non-essential amino acids, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin. All cells were incubated at 37° C in the presence of 5% CO2.

2.2. Mice and Sheep

129 Sv/Ev mice and autochthonous sheep of the Spanish Churra breed were used for the in vivo studies. Female mice 8 week old were obtained in our breeding facilities at the Department of Animal Reproduction (INIA-CSIC). Adult, 4-month-old female Churra sheep of around 40kg were purchased from a local breeder. The sheep were housed and acclimatized for a week before the commencement of the experiment. During the whole experiment the animals had free range of movements (no restrainers) with underlying stray. Water and food were supply ad libitum. All experimental procedures were performed in accordance with EU guidelines (Directive 2010/63/EU), and protocols approved by the Animal Care and Biosafety Ethics’ Committees of Centro Nacional Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Tecnología Agraria y Alimentaria (INIA-CSIC) and Comunidad de Madrid (authorization decision PROEX 079.6/22).

2.3. Plasmid Construction and Recombinant RVFV Rescue

The two plasmids encoding the fusion (F) and hemagglutinin (H) gene sequences from the Nigeria 75/1 PPRV strain (GenBank accession KY628761.1) were provided by a commercial supplier (Biomatik). Both sequences were chemically synthetized, flanked by specific restriction site sequences (AflII and NotI) and cloned into vector pCDNA3.1 to generate plasmids pCDNA3.1-F

PPRV and pCDNA3.1-H

PPRV. Two restriction enzyme sites (XhoI and NcoI), internal to the 5’ and 3’ flanking sequences, were introduced for further subcloning. The 9-amino acid short epitope V5 tag (IPNPLLGLD) sequence and the foot and mouth disease virus (FMDV) Cs8c1 site A sequence (recognized by the mAb SD6 [

17]) were added at the 3’ end of each PPRV gene construct. The F and H genes (

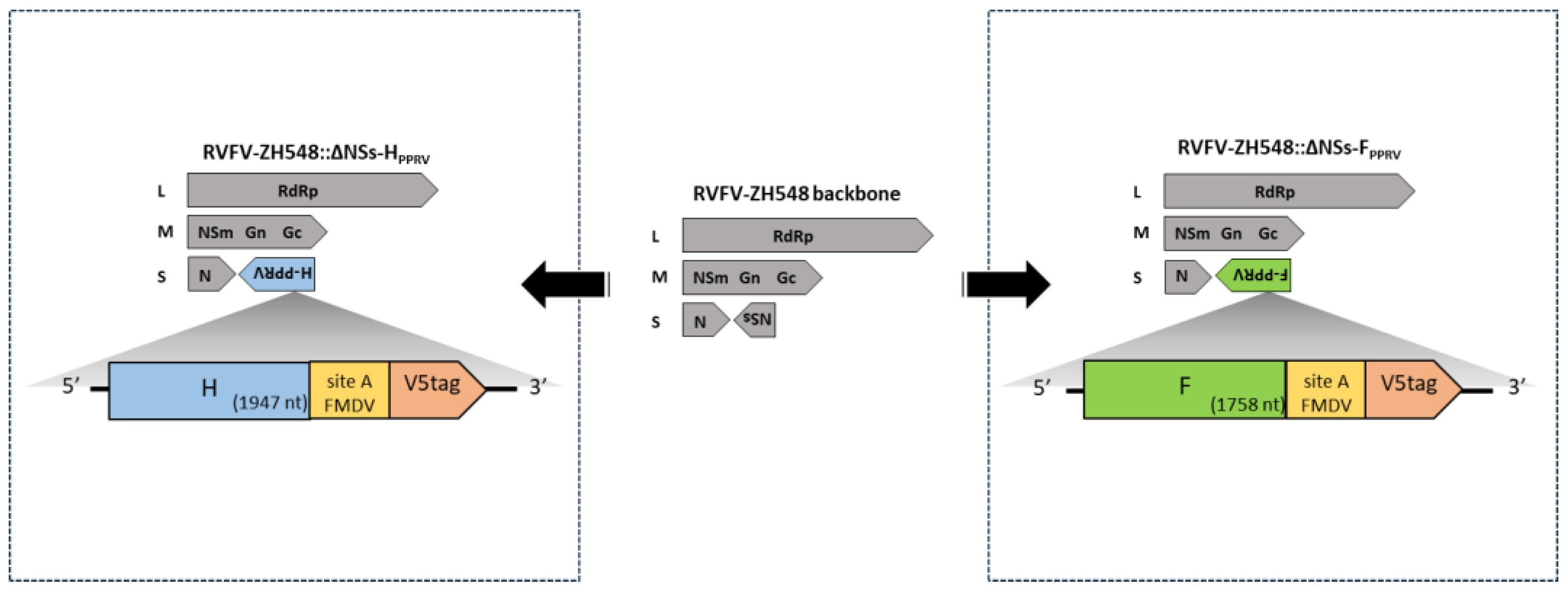

Figure 1) were extracted from the above-mentioned plasmids through restriction enzymes and inserted in the pHH21-RVFV-vN_TCS plasmid [

18] previously digested. The other rescue plasmids were already available and have been previously described [

14,

18].

For recombinant virus generation, a RNA pol I/II-based rescue system was used [

18]. Three pHH21 plasmids provide the three viral RNA segments of the ZH548 RVFV strain. Two pI.18 plasmids encode N or L sequences for expression of the viral nucleoprotein and RdRp polymerase, respectively. Briefly, a co-culture of BHK21 and HEK293T cells were transfected with pHH21-RVFV-vL, pHH21-RVFV-vM, either pHH21-RVFV-vN-F

PPRV or pHH21-RVFV-vN-H

PPRV, pI.18-RVFV-L and pI.18-RVFV-N. Supernatants were harvested at different time points after transfection and screened for the induction of cytopathic effect (cpe) in Vero cell cultures. When viral cpe was confirmed, viral stocks were generated by subculture in Vero cells and used for the following experiments. The viruses generated lack the NSs gene (ΔNSs).

2.4. Viral Plaque Assay

Vero cells grown in 12-well plates were inoculated with ten-fold serial dilutions of supernatants from infected cells in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After 1 h incubation at 37°C, the inoculum was removed and cells were overlaid with semi-solid medium (Eagle’s Minimun Essential Medium (EMEM)-1% carboxymethylcellulose) and further incubated for 3 days at 37°C for rZH548ΔNSs::F

PPRV or 5 days at 37°C for rZH548ΔNSs::H

PPRV. Cells were fixed with 10% formaldehyde, stained with 2% crystal violet and titers were calculated from the plaque numbers obtained for each dilution. Alternatively, viral plaques were visualized by immunostaining using the anti-RVFV nucleoprotein mAb 2B1, as previously described [

19].

2.5. Indirect Immunofluorescence Assay

In order to verify the expression of the heterologous genes upon infection, Vero cells were infected with each recombinant virus at an MOI of 0.5. At 24 hours post-infection cells were fixed with 1:1 methanol-acetone solution and incubated 20 minutes at -20°C. Methanol-acetone was removed and PBS-FBS 20% added and incubated for one hour at room temperature. After washing once with PBS the primary antibody was added (diluted 1:200 in PBS-FCS 20% for serum and 1:500 for monoclonal antibody). A polyclonal rabbit serum [

20] was used for the detection of RVFV and a mouse monoclonal antibody against the V5 epitope tag (clone MCA 1360, Bio-Rad) was used for the detection of either H or F proteins. Primary antibodies were incubated for one hour at 37°C or 4°C overnight. After incubation with the primary antibody, cells were washed three times with PBS-T (PBS with 0.05% Tween-20) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 or goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (Thermo), followed again by three PBS-T washes. Labeling of endoplasmic reticulum was achieved by mAb AHP516 (anti-calreticulin, Bio-Rad). For FMDV detection, BHK-21 cells were infected with FMDV C-S8c1 and fixed 8 hpi and incubated with either mice or sheep sera. Nuclei were visualized by DAPI staining (Thermo). Stained cells were visualized and images obtained using a Zeiss LSM880 confocal laser microscope (Gmbn, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.6. Western Blot and Immunoblotting

Western blot analysis were carried out to evaluate the kinetics of vaccine antigen expression and to indirectly assess their genetic stability. For the kinetics of the antigen expression, monolayers of Vero cells were infected with rZH548ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548ΔNSs::FPPRV. After 24, 48 and 72 hours, cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed in SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Whatmann). The membranes were incubated for one hour with 5% skimmed fat milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Upon blocking, an anti-V5 epitope specific mAb (MCA1360, Bio-Rad) was added diluted 1:1000 in 5% milk-TBS-T (TBS with 0.05% Tween-20) and incubated at 4°C overnight. The membranes were then washed three times with TBS-T and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with an anti-mouse polyvalent immunoglobulins-HRPO conjugated antibody (Sigma). The membrane was washed again three times with TBS-T before adding luminescent substrate (ECL-GE Healthcare). Gel images were visualized using a ChemiDoc Imaging System (Bio-Rad).

For the genetic stability analysis, Vero cell supernatants upon a first, second, third, fourth and fifth serial passages of each recombinant virus were titrated and used to infect Vero cell monolayers using a MOI of 1. After 24 hours, cells were collected and analyzed by SDS-PAGE as above. Upon blocking, the membranes were incubated with the anti-V5 epitope mAb (for transgene expression detection) and the 2B1 anti-RVFV-N mAb [

20] diluted 1:1000 in 5% milk-TBST (for infection reference normalization).

2.7. Mouse and Sheep Immunization and Sampling

Five groups of 129 Sv/Ev mice (n=5) were inoculated intraperitoneally with 105 (high dose, HD) or 5x102 (low dose, LD) pfu/mouse of either rZH548ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548ΔNSs::FPPRV. One group of mice was kept as mock-inoculated control. Mice were monitored daily after inoculation and bled at different time points (2, 3, 4, 5, 14 and 21 days post-infection) to check for viremia and specific antibodies induction. Four weeks after inoculation (immunization), the mice were sacrificed and their spleens collected for intracellular cytokine staining assay (ICS).

Three groups of four sheep were immunized with 107 pfu/sheep of rZH548ΔNSs::FPPRV or 105 pfu/sheep of rZH548ΔNSs::HPPRV or were kept unimmunized. After immunization, animals were monitored and bled at different time points (7, 14 and 21 dpi) to evaluate the humoral and cellular immune response induced by the recombinant virus.

2.8. Anti-PPRV IgG ELISA

IgG anti-PPRV detection was performed as described previously [

12]. Shortly, ELISA plates (Maxisorp, Nunc) were coated and incubated overnight at 4°C with 10

4 pfu per well of saccharose cushion-purified PPRV Nigeria 75/1. Washes and blockage were performed with 0.1% Tween in PBS and 10% FBS in PBS, respectively. PPRV-specific IgGs were detected with a secondary donkey anti-sheep IgG horseradish peroxidase conjugated antibody (Serotec) diluted 1:6666 in PBS + 0.5% FBS or HRPO-conjugated goat-anti-mouse IgG antibody. Liquid Substrate System (Sigma) of 3,3’,5,5’-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) was used as developer agent, and reactions stopped with 3 M sulfuric acid before reading. Optical densities (OD) were read at 450 nm in an ELISA FLUOstar Omega (BMG Labtech) plate reader. The measurements were made in triplicate and considered valid with standard deviations below 10% of the average. Anti- PPRV IgG titer in serum was defined as the serum dilution necessary to achieve readings twice that of pre-immune sera from the same sheep or mouse, and was calculated using a linear regression of serum dilutions vs. OD readings at 450 nm.

2.9. Anti-RVFV-N IgG and Competition ELISAs

ELISA plates (Maxisorp, Nunc) were coated and incubated overnight at 4°C with 50 -100ng/ well of purified recombinant RVFV-N protein diluted in carbonate/bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6. Washes and blockage steps were performed with PBS 0.1% Tween (PBS-T) and 5% skim milk in PBS, respectively. Sera from inoculated mice or sheep were serially diluted in PBS supplemented with 5% skim milk prior to addition to the plate. After three consecutive washing steps, bound antibodies were detected using either HRPO-conjugated goat-anti-mouse or goat-anti-sheep antibodies (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) diluted 1:1000. ELISA signaling and measurements was performed as above. Antibody titers were estimated as reciprocals of the highest dilutions giving value readings twice over those of preimmune (control) sera. The competition ELISA for the detection of RVFV serum nucleoprotein N-specific antibodies was carried out by means of IDVet RVF screen Kit (IDVet, France).

2.10. RVFV Neutralization Test

Sera from vaccinated animals (either mice or sheep) were heat-inactivated at 56°C for 30 minutes, two-fold serially diluted in DMEM (starting 1:20) and mixed with an equal volume (50 μl) of medium containing 103 pfu (per well) of a viral stock (RVFV-MP12 strain). After one hour of incubation at 37°C, the mixture was added to Vero cell monolayers seeded in 96-well plates and incubated at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. After 3 days the cells were fixed and stained with a solution containing 2% crystal violet in 10% formaldehyde. The titer of neutralizing antibodies was determined as the highest dilution that reduced the CPE by 50%.

2.11. PPRV Neutralization Test (VNT)

Sheep or mouse serum samples were tested for the presence of neutralizing antibodies as described previously [

21,

22]. Briefly, Nigeria 75/1 PPRV stock (100 pfu/well) was incubated with serial dilutions of inactivated (30 min 56°C) sheep sera for 1 h at 37ºC in 96 multiwell plates (M-96). Then, VDS cells (2x10

4 cells/well) were added to the mixtures and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO

2. Elapsed 5 days, they were fixed with 2% formaldehyde and stained with crystal violet. All dilutions were performed in duplicate and the neutralization titer is expressed as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of sera at which virus infection is blocked.

2.12. Intracellular Cytokine Staining

Collected spleen cells were stimulated with a peptide pool of three F- and two H-specific peptides from PPRV Nigeria 75 (10 μg/ml each) (GenBank #CAJ01699.1 and #CAJ01700.1 respectively) (

Table 1) as previously described [

23], with ConA mitogen (8 μg/ml) or were left untreated in 10% FCS supplemented RPMI 1640 medium for 6 hours. After stimulation, the spleen cells were washed, stained with surface markers, fixed, permeabilized and stained intracellularly using appropriate fluorochromes. For immunostaining, the following fluorochrome-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies were used: anti-CD8-PE, anti-IFNγ-FITC and anti-CD4-APC (Miltenyi). Data were acquired by FACS analysis on a Cube 8 (Sysmex). Data analyses were performed using the FlowJo software version X0.7 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). The number of lymphocyte-gated events was 5 x 10

4.

2.13. Detection of IFNγ in Sheep Plasma Samples by Capture ELISA

IFNγ capture ELISA was carried out as previously described [

24,

25]. 100 µL of heparinized blood, collected at different time points before and after inoculation from each animal were incubated in multiwell plates with a peptide pool of three F- and two H-specific peptides from PPRV Nig’75 (10 μg/ml each) (

Table 1) or purified recombinant Gn or NP protein for 48 h. Next, the plates were centrifuged and plasma was collected and kept at −80 °C until use. 50 µL of plasma from each time point sample was assayed in the capture ELISA. After washing steps biotinylated anti bovine IFNγ (clone MT307, Mabtech) was added. Streptavidin-HRPO (Becton-Dickinson) was used for detection of immunocomplexes upon addition of TMB peroxidase substrate (Sigma-Aldrich). Absorbance values were determined at 450 nm by an automated reader (BMG, Labtech)

2.14. Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 10 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences in antibody levels, T-cell responses, serum biochemical parameters, fever and viremia between vaccine groups were calculated by ANOVA tests. Survival data were analyzed using a log rank test with mice grouped by immunization strategy. A significance level of P < 0.05 was set in all analyses.

4. Discussion

Vaccination is a potential means of controlling RVF in ruminants. From a One-Health perspective, immunising ruminants would reduce the impact of this disease on humans. However, despite the availability of effective live-attenuated RVFV vaccines, implementing a vaccination policy in most African countries is challenging due to the prolonged inter-epizootic periods between RVF outbreaks. Vaccination is usually only adopted after epizootic outbreaks have occurred, often too late to prevent the virus being transmitted between animals and humans. This makes it difficult for herd owners to perceive RVF vaccination as a necessity. One potential solution is to integrate RVF prevention activities with other vaccination programs for small ruminants. Implementing a routine preventive vaccination programme would be highly beneficial, as it would maintain protective levels of immunity and prevent the rapid spread of an outbreak. Co-immunisation of livestock with vaccines against RVF and other prevalent ruminant diseases requiring regular vaccination campaigns, such as PPR, could be an effective strategy, particularly in the context of the current global PPR eradication campaign.

The use of viral vectored vaccines expressing PPRV H and F antigens induces a humoral and cellular response that is able to protect animals against a PPRV challenge [

23,

26,

27]. Similarly, the expression of RVFV glycoproteins Gn and Gc is sufficient to ensure protective immune responses in ruminant species [

28,

29]. Different viral vectored vaccines have been proposed for both viruses such as adenovirus platforms [

12,

30,

31], poxvirus [

32,

33,

34] and herpesvirus [

35,

36] among them. Combining PPR and RVF vaccines has been also proposed as an ease mean to improve vaccination coverage and efficacy [

37]. Here, we propose the use of attenuated RVFV as a viral vector encoding heterologous vaccine antigens as shown in previous studies [

13,

14]. The attenuation of the virus is achieved by deleting the virulence–associated NSs gene, non-essential for the productive replication of the virus in cell culture [

38]. NSs gene deletion generates an insertion site that, in agreement to the previously demonstrated genome plasticity of RVFV [

39], allows the insertion of theoretically any gene of interest. Inoculation of adult animals with these recombinant, NSs deleted, viral vaccines expressing tagged PPRV H and F genes was safe and induced no adverse effects. Animals monitored after inoculation showed no viremia, fever, any other biochemical, or hematological alterations.

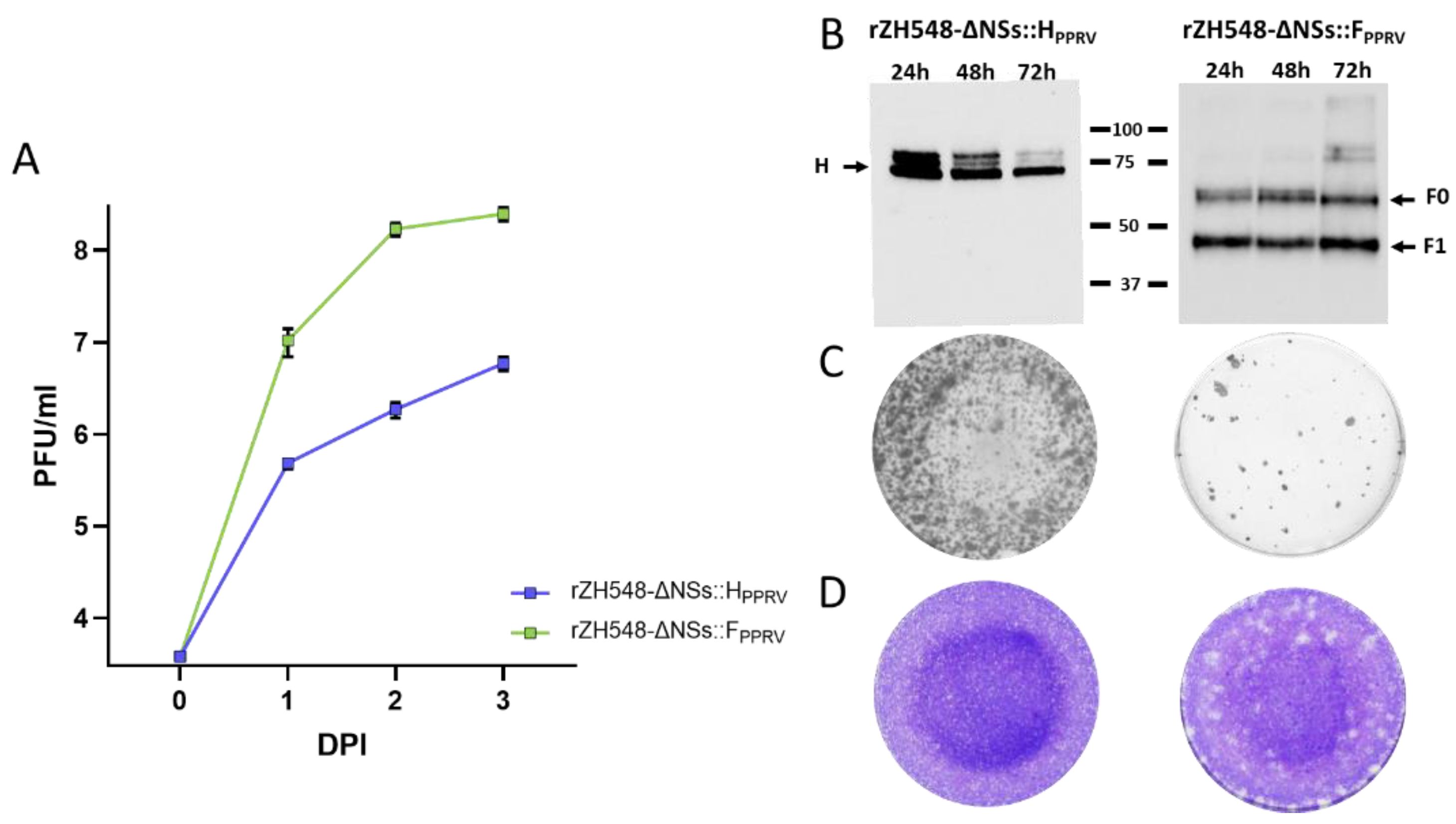

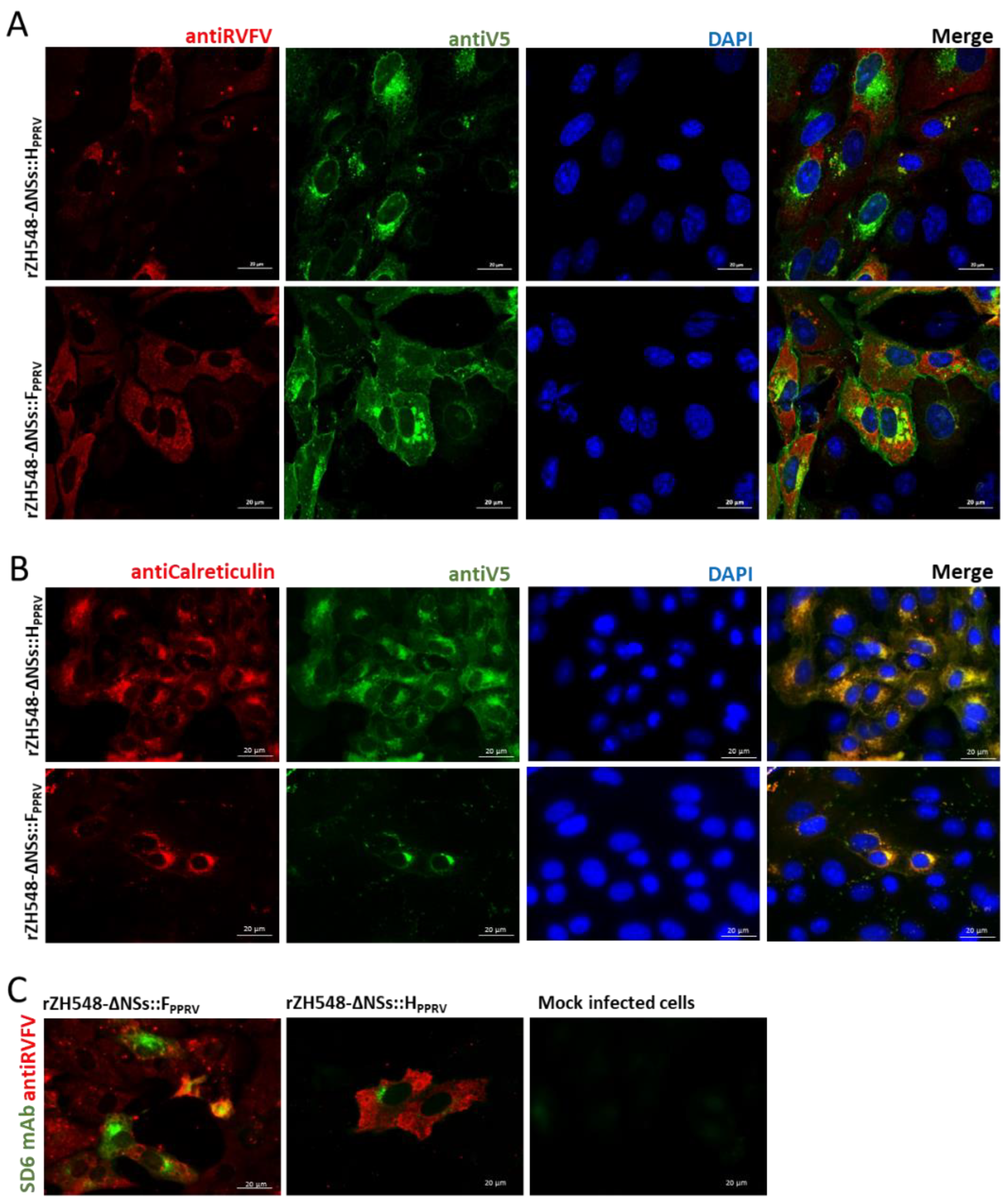

The expression of both H and F proteins by means of the RVFV vector was highly satisfactory. Both full-length proteins were detectable in association to intracellular membranes, suggesting that proper intracellular trafficking through the cell secretory pathway and post-translational protein modifications took place. Both heterologous antigens were stable in vitro, with little or no signs of degradation during the time course of infection and upon serial propagation. Moreover, the PPRV-Fusion protein was proteolytically processed as expected, in agreement with the protein fragment sizes observed in the western blot analysis. The molecular weights of these processed forms fit well with what has been described for measles virus (MeV) envelope glycoproteins and other morbilliviruses (around 60kDa and 41kDa for F0 and F1, respectively) [

23,

40,

41]. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the expression of both proteins mimics those of an authentic PPRV infection, thus providing similar antigen presenting properties, facilitating the induction of the adequate immune responses.

In our study, we have shown that delivery of either H or F antigens by using a recombinant RVFV is able to elicit presumably protective B and T-cell responses. It is known that both responses are useful in protection, since the induction of IgG and neutralizing antibodies are necessary to avoid or prevent reinfections and a good cellular response is key to rapidly target and eliminate infected cells. After a single immunization with rZH548-ΔNSs::H

PPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::F

PPRV, both no neutralizing and neutralizing PPRV specific antibodies were detected in mice and sheep sera, the later with titers that could be considered protective according to reported literature data [

12] and therefore, predictive of vaccine efficacy [

22]. In both animal models, anti-RVFV neutralizing titers were also produced at protective levels, as previously reported [

42]. As was the case with the previously mentioned virus, antibodies against FMDV were also elicited, though these were non-neutralising in both animal models. The lack of FMDV-neutralising capabilities of these sera may suggests that the sequence of the site A fused to either the recombinant H or F proteins is not properly exposed, as it is in the native conformation of FMDV capsids If this is the case, redesigning the inserted site A sequence to make it similar to that of FMDV particles would be an interesting improvement to add additional protective features to these recombinant viruses..

Our results warrant further experiments to test the in vivo protective capacity against PPRV challenge in either sheep or goats. An efficacy/challenge study in target hosts was not attempted in this study because the immune responses against PPRV in sheep were not homogeneous (3 out of 8 vaccinated animals did not show detectable serum neutralizing antibodies). These discrepancies could be partly explained by the low inoculation dose of rZH548-ΔNSs::H

PPRV administered to the sheep (which was as low as that used in the mouse experiment). It would be necessary to raise the inoculation dose of rZH548-ΔNSs::H

PPRV before undertaking costly efficacy experiments. On the other hand, since the inoculation of 10

7 pfu/sheep with rZH548-ΔNSs::F

PPRV was completely safe in healthy animals, with no evidence of viremia, it may be possible to test a higher dose, e.g. 10⁸ PFU per animal, to guarantee more uniform immunity in all vaccinated individuals. Another possible explanation for the lower and delayed anti-PPRV-H antibody responses could be related to the lower protein expression level and slower growth kinetics exhibited by rZH548-ΔNSs::H

PPRV in Vero cells. (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Since infection with rZH548-ΔNSs::H

PPRV was less cytopathogenic than that of rZH548-ΔNSs::F

PPRV, it could be suggestive of an interfering effect of the PPRV hemagglutinin with the normal RVFV cell cycle. Attempts to grow rZH548-ΔNSs::H

PPRV to reach higher titers in other more permissive cell lines are in progress.

Currently, new generation PPR vaccines are sought to be also capable of inducing a cellular immune response because it is known that T-cell activation contributes to the protection against infection and confers a cross-protective immunity [

43]. Immunization with both recombinant viruses also elicited PPRV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses, reflecting the potential of protecting against multiple PPRV strains. Although differences were not significant, lower induction of cellular and humoral responses were detected after inoculation with rZH548-ΔNSs::H

PPRV compared to rZH548-ΔNSs::F

PPRV, in line with the lower expression levels achieved for the hemagglutinin antigen, as discussed above.

Although it is not yet clear whether combining H and F expression will improve protection, some studies suggest that using both antigens can induce better protection than using one antigen alone [

16,

44]. Therefore, the combination of both RVFV-vectored PPR vaccines is another aspect to consider for future efficacy experiments. Having proven these strategies successful, combining recombinant RVFV vaccines could provide a new research opportunity to test vaccine cocktails for simultaneous immunization against multiple ruminant diseases. Previous studies have shown that a rRVFV expressing either bluetongue virus VP2 or NS1 antigens can elicit protective immune responses against a BTV-4 challenge [

14]. Therefore, it would be feasible in the future to provide immunity against RVFV and other small ruminant diseases by combining rRVFV vaccines in a single dose approach.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B. and A.B.; methodology, S.M., G.L., B.B., V.M. and C.A..; validation, S.M., A.B. and B.B.; formal analysis, B.B. and A.B.; investigation, S.M., G.L, V.M., C.A.; B.B; resources, A.B., S.M., F.W.; data curation, S.M, A.B and B.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, A.B.; visualization, B.B. and A.B.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, A.B.; funding acquisition, B.B. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the genomic structure of the rRVFV-PPRV rescued by reverse genetics system. The foreign sequences to be inserted by means of two pHH21-vN constructs are detailed (not to scale). The V5 tag epitope and the FMDV Cs8c1 site A sequence (recognized by the SD6 mAb) were added at the 3’ end of each PPRV ORF for detection purposes. Inverted writing denotes the coding orientation with respect to the nucleoprotein ORF in the viral genome. Nucleotide numbers indicates the size of the inserted PPRV sequences.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the genomic structure of the rRVFV-PPRV rescued by reverse genetics system. The foreign sequences to be inserted by means of two pHH21-vN constructs are detailed (not to scale). The V5 tag epitope and the FMDV Cs8c1 site A sequence (recognized by the SD6 mAb) were added at the 3’ end of each PPRV ORF for detection purposes. Inverted writing denotes the coding orientation with respect to the nucleoprotein ORF in the viral genome. Nucleotide numbers indicates the size of the inserted PPRV sequences.

Figure 2.

Characterization of rescued RVFVs. A. Growth kinetics of rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV and rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV. Vero cells were infected with a MOI of 0.01 and supernatants were harvested at the indicated time points (days post infection). Viral titers (mean ± SD) were determined by plaque assay upon infection of Vero cells with serial dilutions of the supernatants. Titrations were performed in duplicates. B. Western blot analysis of rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV infected Vero cells at different times post infection. Anti-V5tag mAb was used for the detection of either H or F recombinant proteins. The arrows point the detection of F0 (unprocessed), F1 (processed) and H proteins. C-D. Plaque phenotypes of the rescued recombinant viruses. Cell lysis was visualized at 3–5 days post infection: immunostaining with anti-N mAb 2B1 (c) or Crystal violet staining (d).

Figure 2.

Characterization of rescued RVFVs. A. Growth kinetics of rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV and rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV. Vero cells were infected with a MOI of 0.01 and supernatants were harvested at the indicated time points (days post infection). Viral titers (mean ± SD) were determined by plaque assay upon infection of Vero cells with serial dilutions of the supernatants. Titrations were performed in duplicates. B. Western blot analysis of rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV infected Vero cells at different times post infection. Anti-V5tag mAb was used for the detection of either H or F recombinant proteins. The arrows point the detection of F0 (unprocessed), F1 (processed) and H proteins. C-D. Plaque phenotypes of the rescued recombinant viruses. Cell lysis was visualized at 3–5 days post infection: immunostaining with anti-N mAb 2B1 (c) or Crystal violet staining (d).

Figure 3.

Detection of recombinant PPRV transgene expression in RVFV infected cell cultures. A. Indirect immunofluorescence analysis (IFA) of rescued RVFVs infected Vero cells. A rabbit anti-RVFV polyclonal serum was used for the detection of RVFV antigens (red fluorescence). Mouse anti-V5tag antibody was used for H and F detection (green fluorescence). B. Subcellular location of the recombinant proteins in infected cells. H and F antigens were detected with anti-V5tag antibody (green fluorescence) and anti-calreticulin (red fluorescence) used to localize ER. DAPI staining was used to show cell nuclei. Magnification 63X. C. Detection of the FMDV site A tag by SD6 mAb (green fluorescence). RVFV antigens (red fluorescence).

Figure 3.

Detection of recombinant PPRV transgene expression in RVFV infected cell cultures. A. Indirect immunofluorescence analysis (IFA) of rescued RVFVs infected Vero cells. A rabbit anti-RVFV polyclonal serum was used for the detection of RVFV antigens (red fluorescence). Mouse anti-V5tag antibody was used for H and F detection (green fluorescence). B. Subcellular location of the recombinant proteins in infected cells. H and F antigens were detected with anti-V5tag antibody (green fluorescence) and anti-calreticulin (red fluorescence) used to localize ER. DAPI staining was used to show cell nuclei. Magnification 63X. C. Detection of the FMDV site A tag by SD6 mAb (green fluorescence). RVFV antigens (red fluorescence).

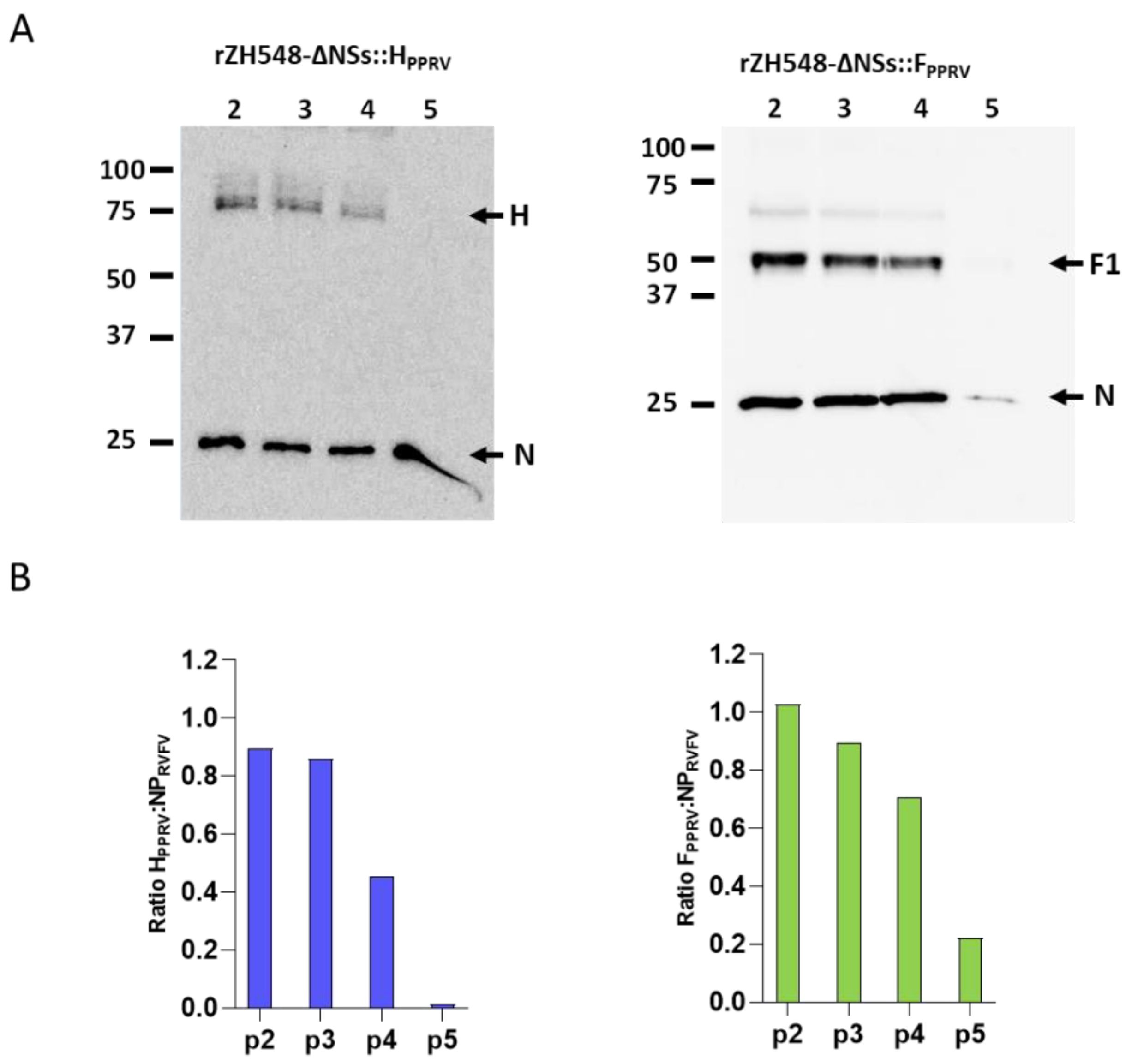

Figure 4.

Stability of recombinant antigen expression. A. Expression upon cell passage of rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV. Total cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to western blot transfer.. Anti-V5tag mAb was used for the detection of either H or F recombinant proteins. Anti-N mAb 2B1 was used to detect the expression of RVFV nucleoprotein N. Molecular mass in kDa. B. Relative detection of H/N or F/N ratios derived from densitometric WB values at different passages.

Figure 4.

Stability of recombinant antigen expression. A. Expression upon cell passage of rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV. Total cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to western blot transfer.. Anti-V5tag mAb was used for the detection of either H or F recombinant proteins. Anti-N mAb 2B1 was used to detect the expression of RVFV nucleoprotein N. Molecular mass in kDa. B. Relative detection of H/N or F/N ratios derived from densitometric WB values at different passages.

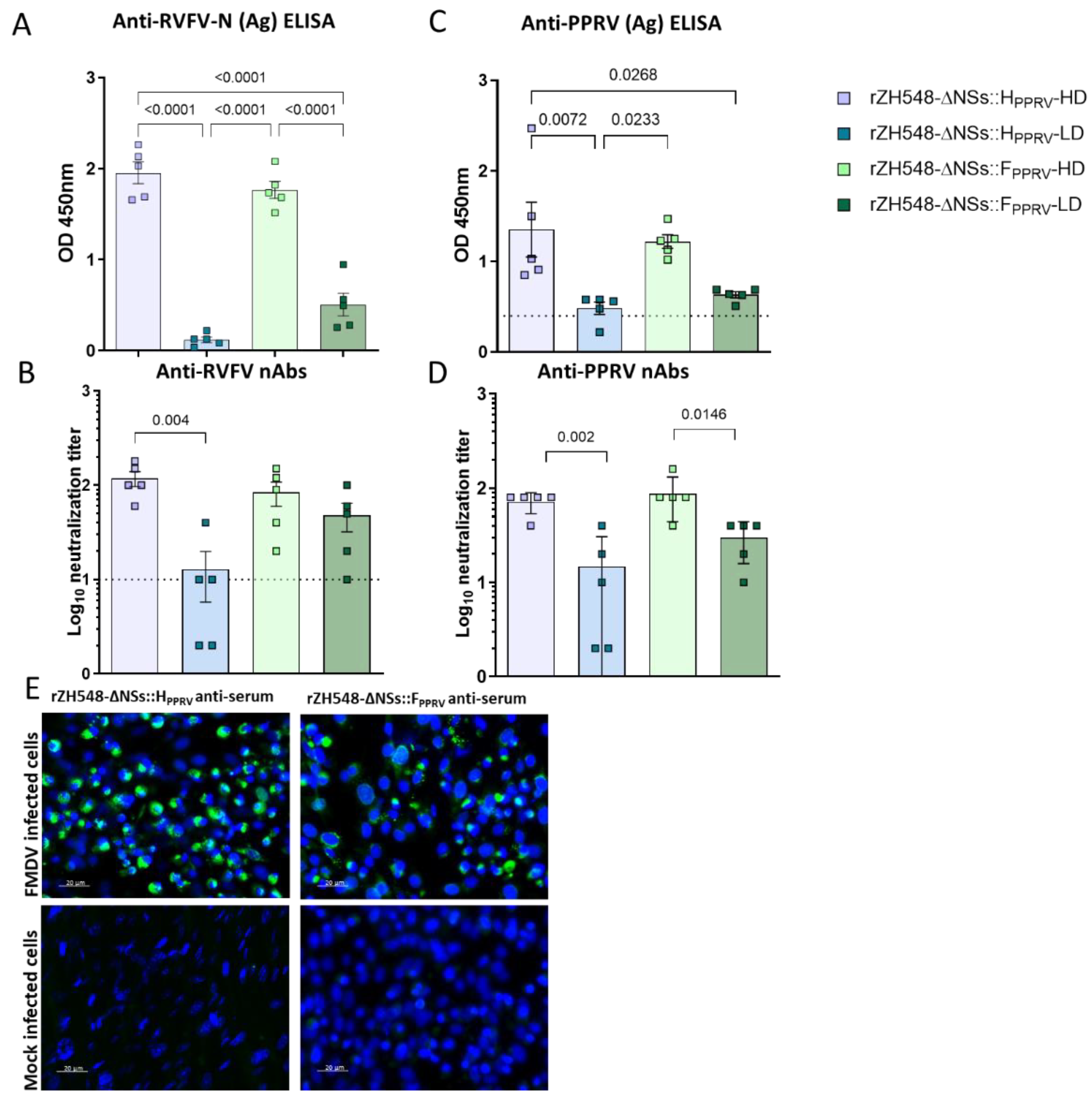

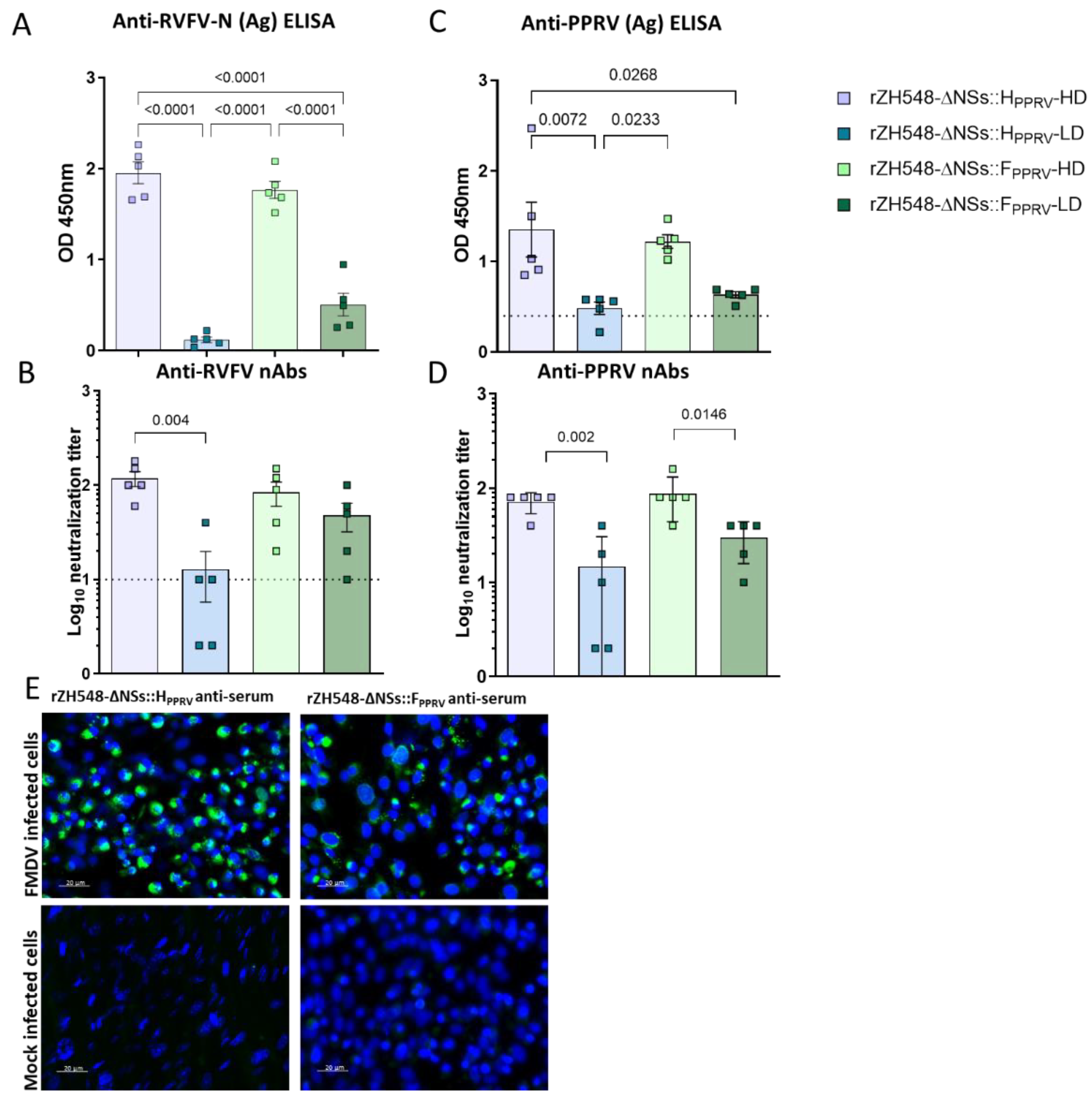

Figure 5.

Humoral responses upon single dose rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV inoculation of mice. A. Detection by ELISA of anti-N serum antibodies upon inoculation of two different doses of the recombinant viruses. ELISA plates were coated with recombinant purified nucleoprotein N. Serum samples diluted 1/100 were obtained 30 days post inoculation. Anti-NP titers are expressed as the last dilution of serum (log10) giving an OD reading at 450 nm over 2X the background value B. Neutralizing antibody induction against RVFV after immunization. C. Detection by ELISA of anti-PPRV serum antibodies. ELISA plates were coated with semi purified PPRV infected antigen lysate. D. Neutralizing antibody induction against PPRV after immunization. Horizontal dotted lines represent assays’ sensitivity limits. E. PPRV-H or F transfected and FMDV infected BHK-21 cells were detected using sera from mice inoculated with 105 pfus of rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV. HD: High dose, 105 pfu/ml; LD: Low dose, 500 pfu/ml. Data (A-D) are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical comparisons were performed using a one-way ANOVA.

Figure 5.

Humoral responses upon single dose rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV inoculation of mice. A. Detection by ELISA of anti-N serum antibodies upon inoculation of two different doses of the recombinant viruses. ELISA plates were coated with recombinant purified nucleoprotein N. Serum samples diluted 1/100 were obtained 30 days post inoculation. Anti-NP titers are expressed as the last dilution of serum (log10) giving an OD reading at 450 nm over 2X the background value B. Neutralizing antibody induction against RVFV after immunization. C. Detection by ELISA of anti-PPRV serum antibodies. ELISA plates were coated with semi purified PPRV infected antigen lysate. D. Neutralizing antibody induction against PPRV after immunization. Horizontal dotted lines represent assays’ sensitivity limits. E. PPRV-H or F transfected and FMDV infected BHK-21 cells were detected using sera from mice inoculated with 105 pfus of rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV. HD: High dose, 105 pfu/ml; LD: Low dose, 500 pfu/ml. Data (A-D) are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical comparisons were performed using a one-way ANOVA.

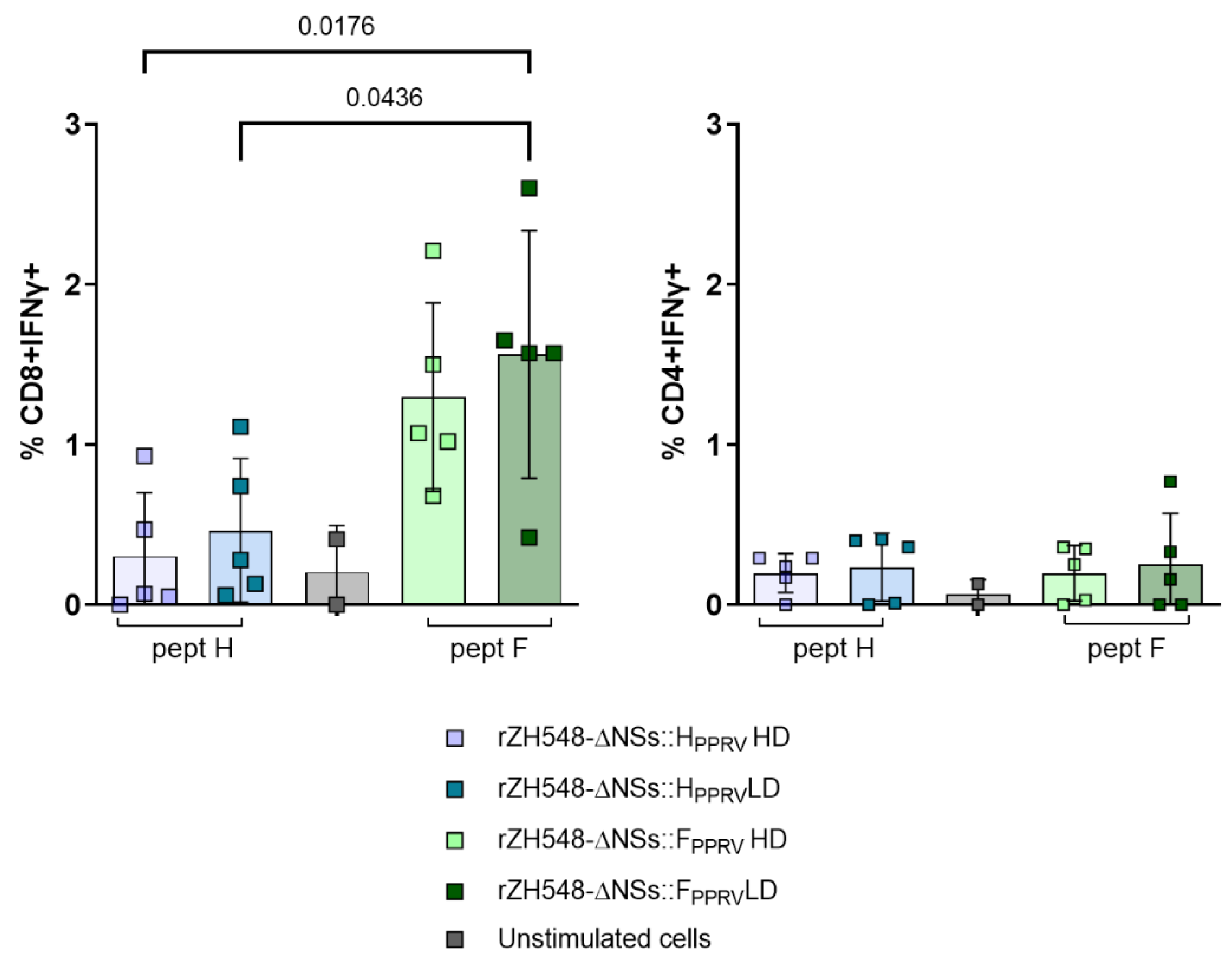

Figure 6.

Detection of transgene-specific cellular responses. Intracellular cytokine cell staining (ICCS). Percentage of CD8+ & CD4+ IFNγ+ T-cells after re-stimulation with a pool of H or F peptides. Data are presented as mean percentages of IFNγ+ T cells normalized to RPMI medium stimulated cells for each mouse. HD: High dose, 105 pfu/ml; LD: Low dose, 500 pfu/ml. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical comparisons were performed using a one-way ANOVA. Individual data points are plotted to represent biological replicates.

Figure 6.

Detection of transgene-specific cellular responses. Intracellular cytokine cell staining (ICCS). Percentage of CD8+ & CD4+ IFNγ+ T-cells after re-stimulation with a pool of H or F peptides. Data are presented as mean percentages of IFNγ+ T cells normalized to RPMI medium stimulated cells for each mouse. HD: High dose, 105 pfu/ml; LD: Low dose, 500 pfu/ml. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical comparisons were performed using a one-way ANOVA. Individual data points are plotted to represent biological replicates.

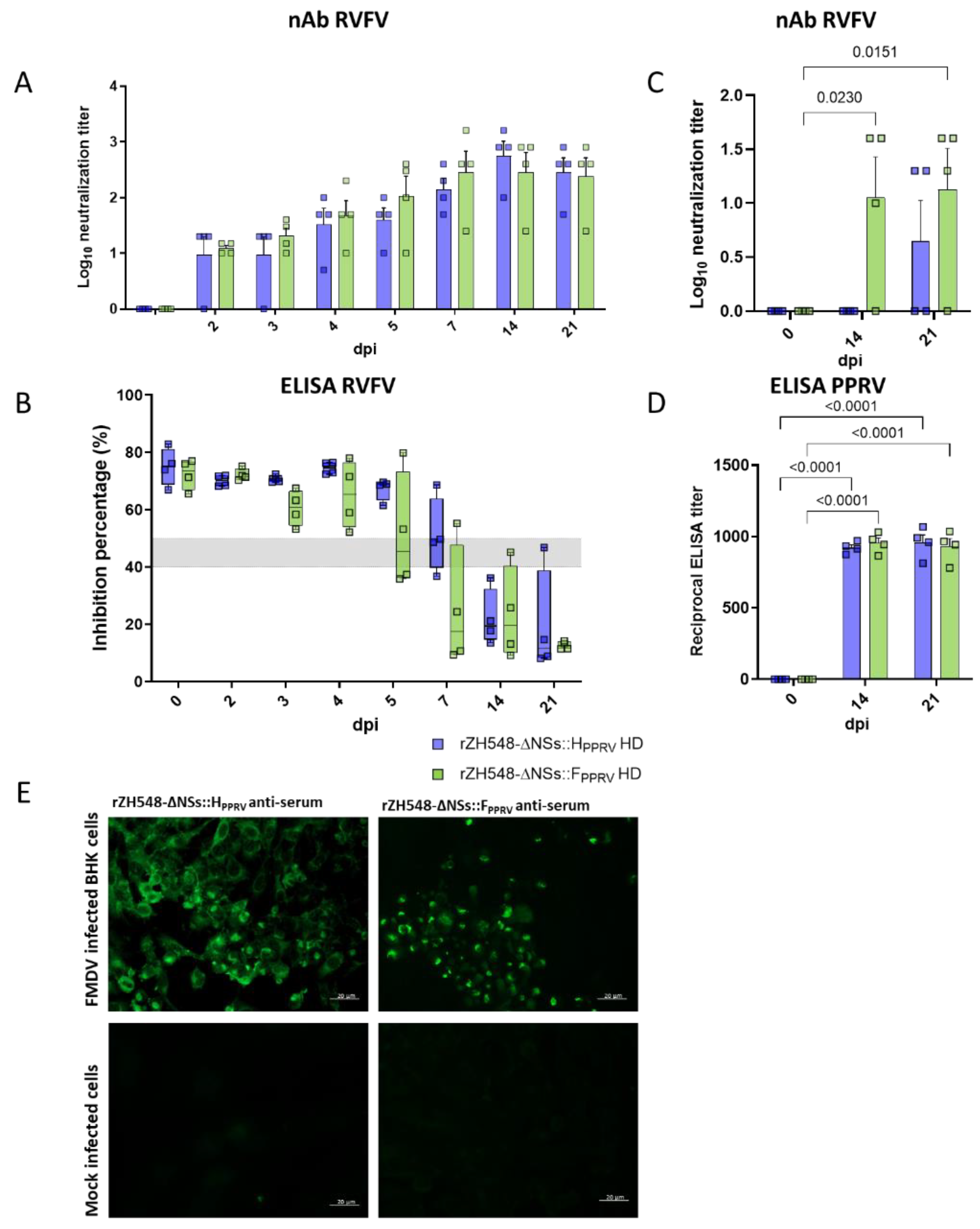

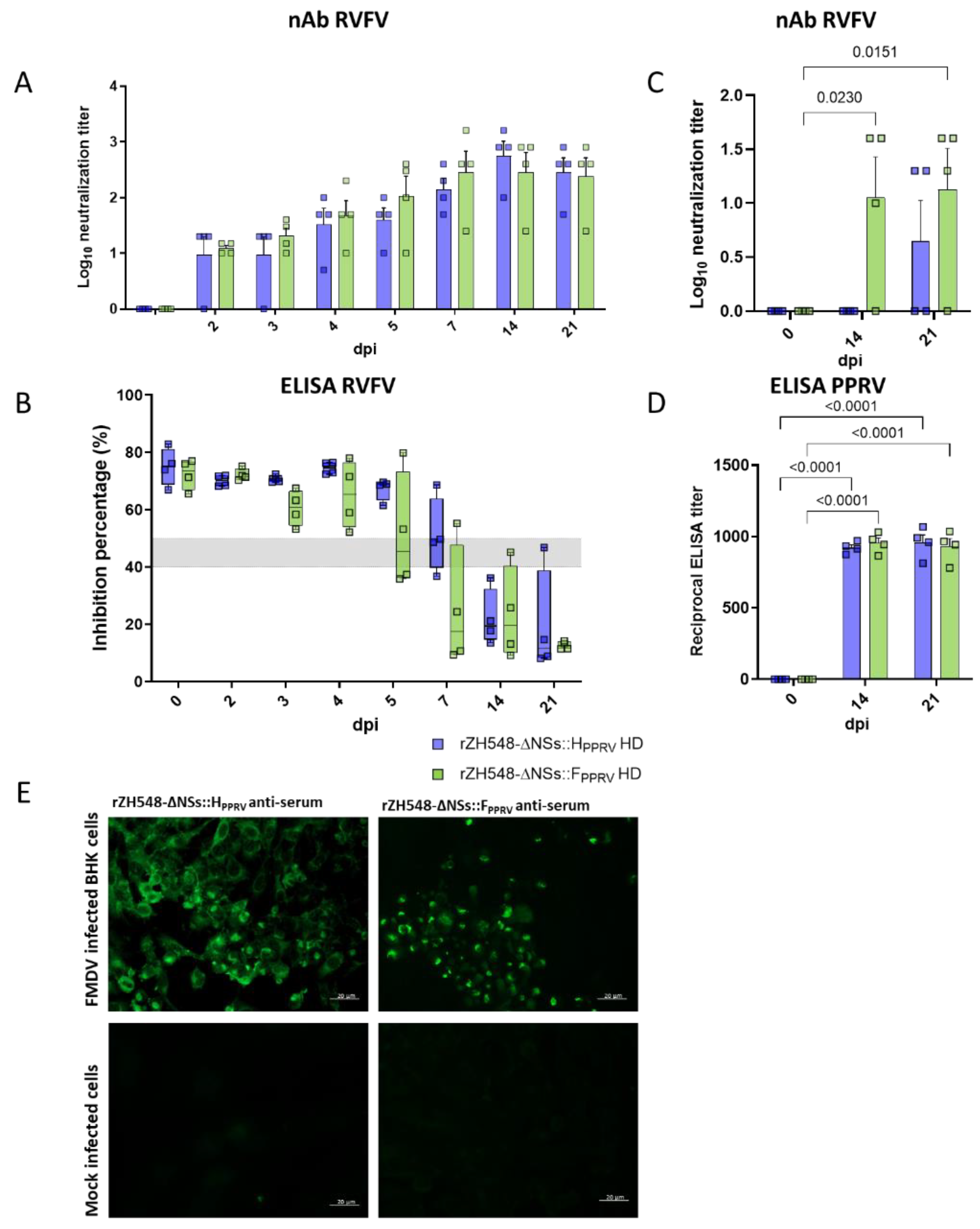

Figure 7.

Humoral immune response upon single dose rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV inoculation of sheep. A. Kinetics of RVFV neutralizing antibody induction in sheep after a single dose of the vaccines. B. Detection by ELISA of anti-NP serum antibodies at 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 14 and 21 days post-inoculation. C. Serum samples obtained at days 14 and 21 post-immunization were analyzed for PPRV-specific IgG by ELISA using Nigeria 75/1 PPRV coated plates. Data are presented as 1/ X IgG titer for each animal. D. Neutralizing antibodies titers against PPRV Nigeria 75/1 were determined for the same animal groups described in A and expressed as the reciprocal of the last dilution of serum that blocked 50% of the virus-specific cytopathic effect in flat bottom 96 plates. E. Detection of FMDV infected BHK-21 cells by indirect immunofluorescence with serum from a sheep inoculated with rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV. Data (A, C and D) are expressed as mean ± SEM, with individual values shown as dots. Data (B) is expressed as median with interquartile range, with individual data points representing biological replicates. Significance (C &D) was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA.

Figure 7.

Humoral immune response upon single dose rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV inoculation of sheep. A. Kinetics of RVFV neutralizing antibody induction in sheep after a single dose of the vaccines. B. Detection by ELISA of anti-NP serum antibodies at 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 14 and 21 days post-inoculation. C. Serum samples obtained at days 14 and 21 post-immunization were analyzed for PPRV-specific IgG by ELISA using Nigeria 75/1 PPRV coated plates. Data are presented as 1/ X IgG titer for each animal. D. Neutralizing antibodies titers against PPRV Nigeria 75/1 were determined for the same animal groups described in A and expressed as the reciprocal of the last dilution of serum that blocked 50% of the virus-specific cytopathic effect in flat bottom 96 plates. E. Detection of FMDV infected BHK-21 cells by indirect immunofluorescence with serum from a sheep inoculated with rZH548-ΔNSs::HPPRV or rZH548-ΔNSs::FPPRV. Data (A, C and D) are expressed as mean ± SEM, with individual values shown as dots. Data (B) is expressed as median with interquartile range, with individual data points representing biological replicates. Significance (C &D) was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA.

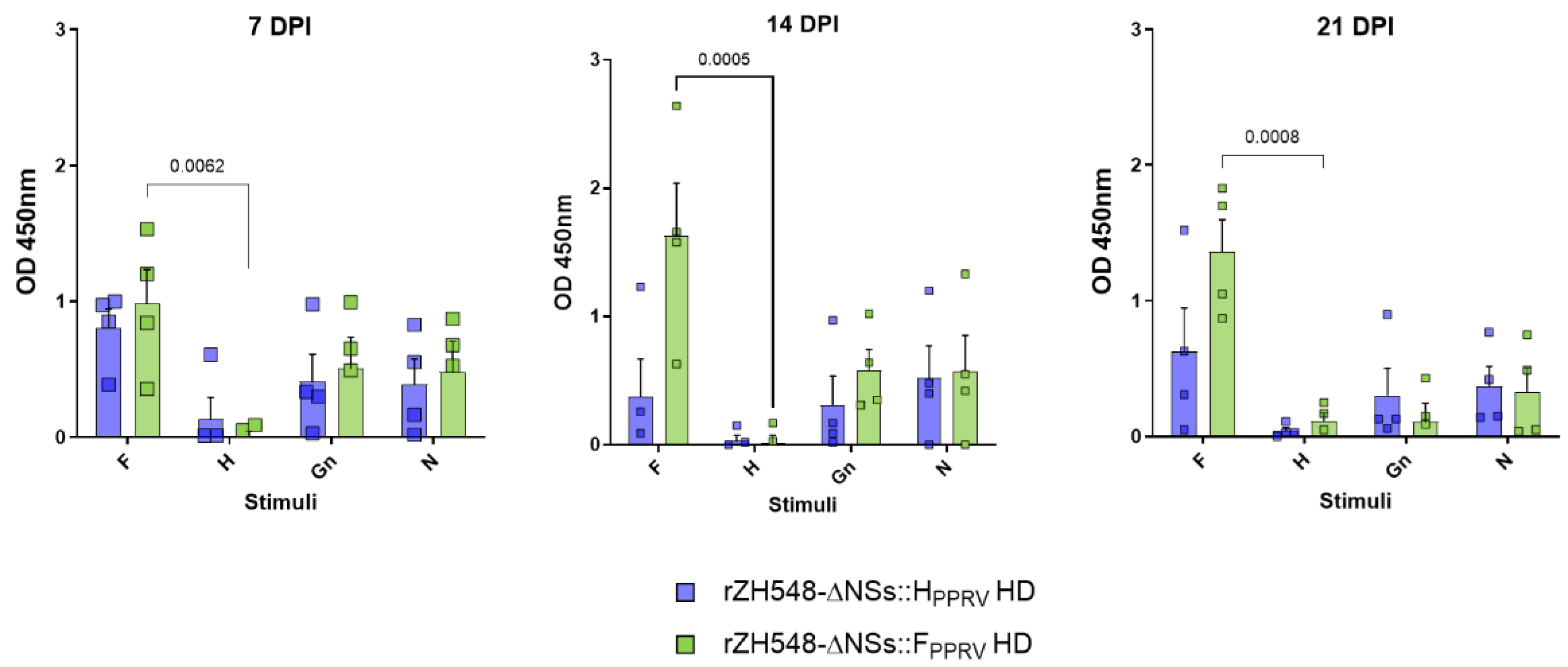

Figure 8.

Detection of plasmatic levels of IFNγ after immunization. Blood samples were collected and re-stimulated with RPMI, ConA or recombinant PPRV (F and H) or RVFV (Gn and N) proteins, and the levels of IFN-γ were measured in the plasma recovered from the samples. Background (i.e., the value determined in unstimulated controls) was subtracted from each sample. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance between groups across conditions was assessed using two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test to correct for multiple testing. Individual data points are overlaid on the bars.

Figure 8.

Detection of plasmatic levels of IFNγ after immunization. Blood samples were collected and re-stimulated with RPMI, ConA or recombinant PPRV (F and H) or RVFV (Gn and N) proteins, and the levels of IFN-γ were measured in the plasma recovered from the samples. Background (i.e., the value determined in unstimulated controls) was subtracted from each sample. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance between groups across conditions was assessed using two-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test to correct for multiple testing. Individual data points are overlaid on the bars.

Table 1.

PPRV peptides used in the ICS assay for re-stimulation of mouse spleen cells.

Table 1.

PPRV peptides used in the ICS assay for re-stimulation of mouse spleen cells.

| Peptide name |

PPRV protein (aa position) |

Sequence |

Predicted H-2 allele binding |

| F8 |

F (117-131) |

VALGVATAAQITAGV |

I-Ab

|

| F9 |

F (341-355) |

QNALYPMSPLLQECF |

I-Ab

|

| F10 |

F (284-298) |

LSEIKGVIVHKIEAI |

I-Ab

|

| H5 |

H (551–559) |

YFYPVRLNF |

Db

|

| Kb

|

| H9 |

H (427-441) |

ITSVFGPLIPHLSGM |

I-Ab

|