Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Epigenetic Signatures in Prostate Cancer

2.1. Overview of Epigenetics

2.1.1. Types of Epigenetic Modifications

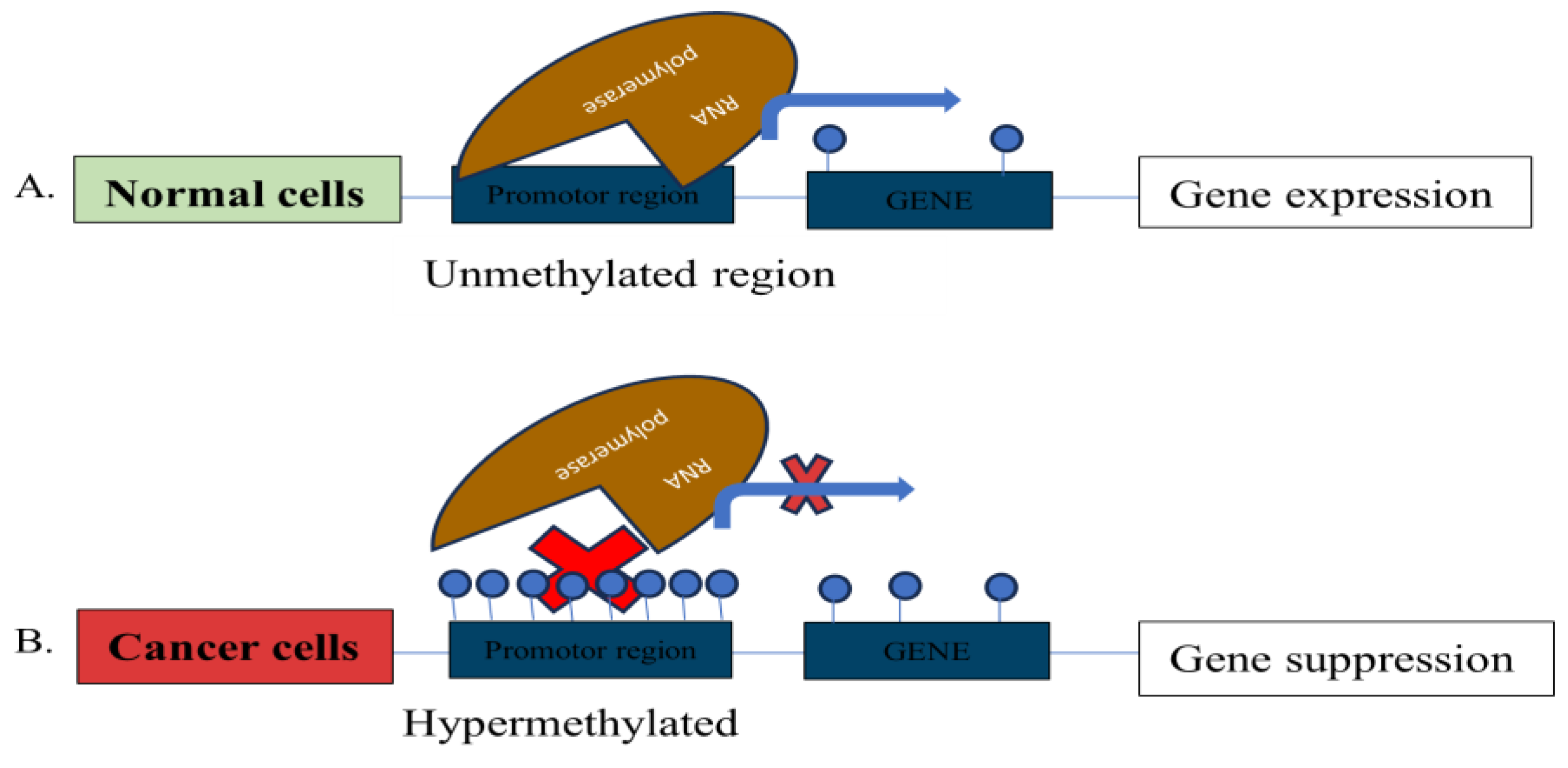

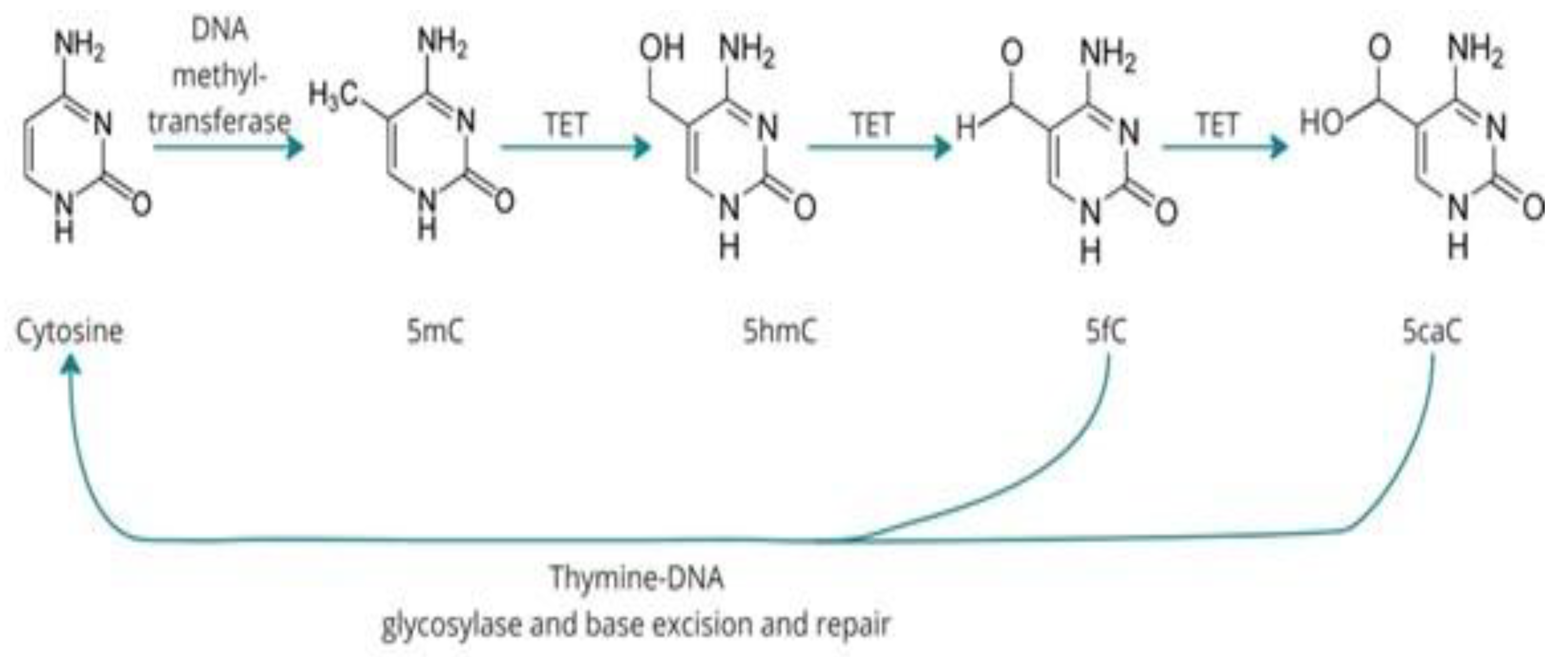

DNA Methylation

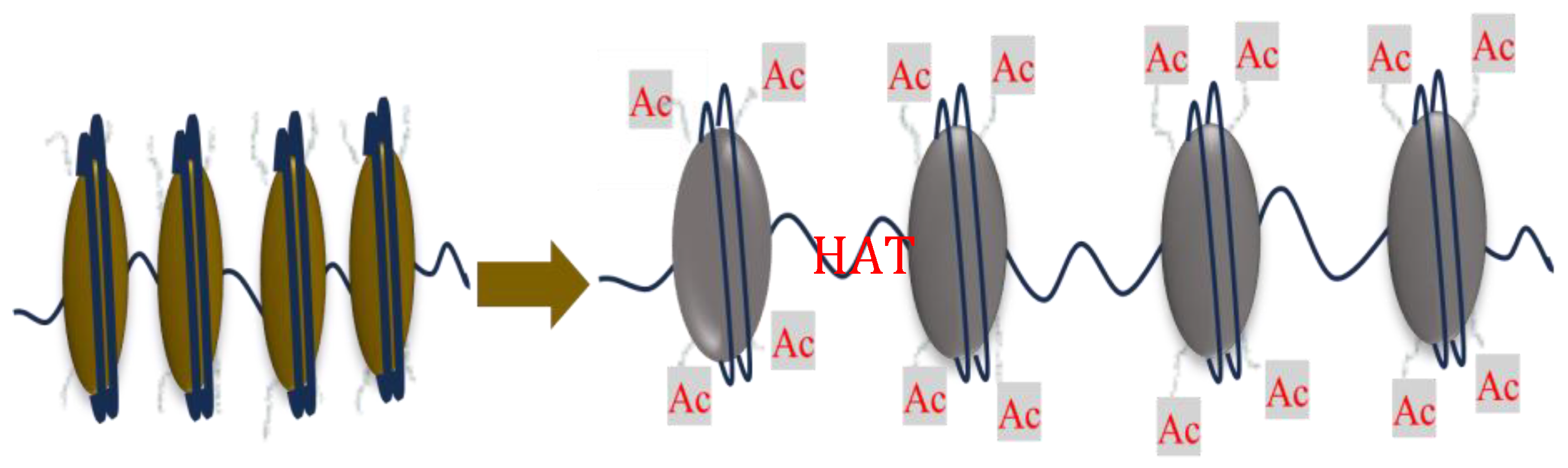

Histone Modification

Non-Coding RNAs Mediated Regulation

2.2. Common Epigenetic Markers Identified in Prostate Cancer

| Epigenetic Maker | Gene category | Gene | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA hypermethylation | DNA damage repair | GSTP 1 | [35] |

| MGMT | [41] | ||

| Cell adhesion | CDH1 | [42] | |

| T IMP3 | [43] | ||

| Tumour suppression and Apoptosis control |

RARβ2 | [44] | |

| APC | [45] | ||

| RASSF1 | [46] | ||

| CRACR2A | [34] | ||

| LGALS3 | [47] | ||

| DNA hypomethylation | Detoxification and hormone response | CYP1B1 | [48] |

| Tumor invasion | HPSE | [49] | |

| Histone modification | Increased methylation | H3K27me3 | [35] |

| Decreased methylation | SIRT7 | [36] | |

| Decreased acetylation | H3K9ac | [37] | |

| miRNAs | Upregulation | MicroRNA-21 | [38] |

| MicroRNA-18a-5p | [39] | ||

| MicroRNA-4534 | [40] | ||

| MicroRNA-375 | [50] |

Relevance to Early Detection: Stability, Specificity, and Detectability in Biofluids

2.3. Epigenetic Biomarkers in Sub-Saharan Populations

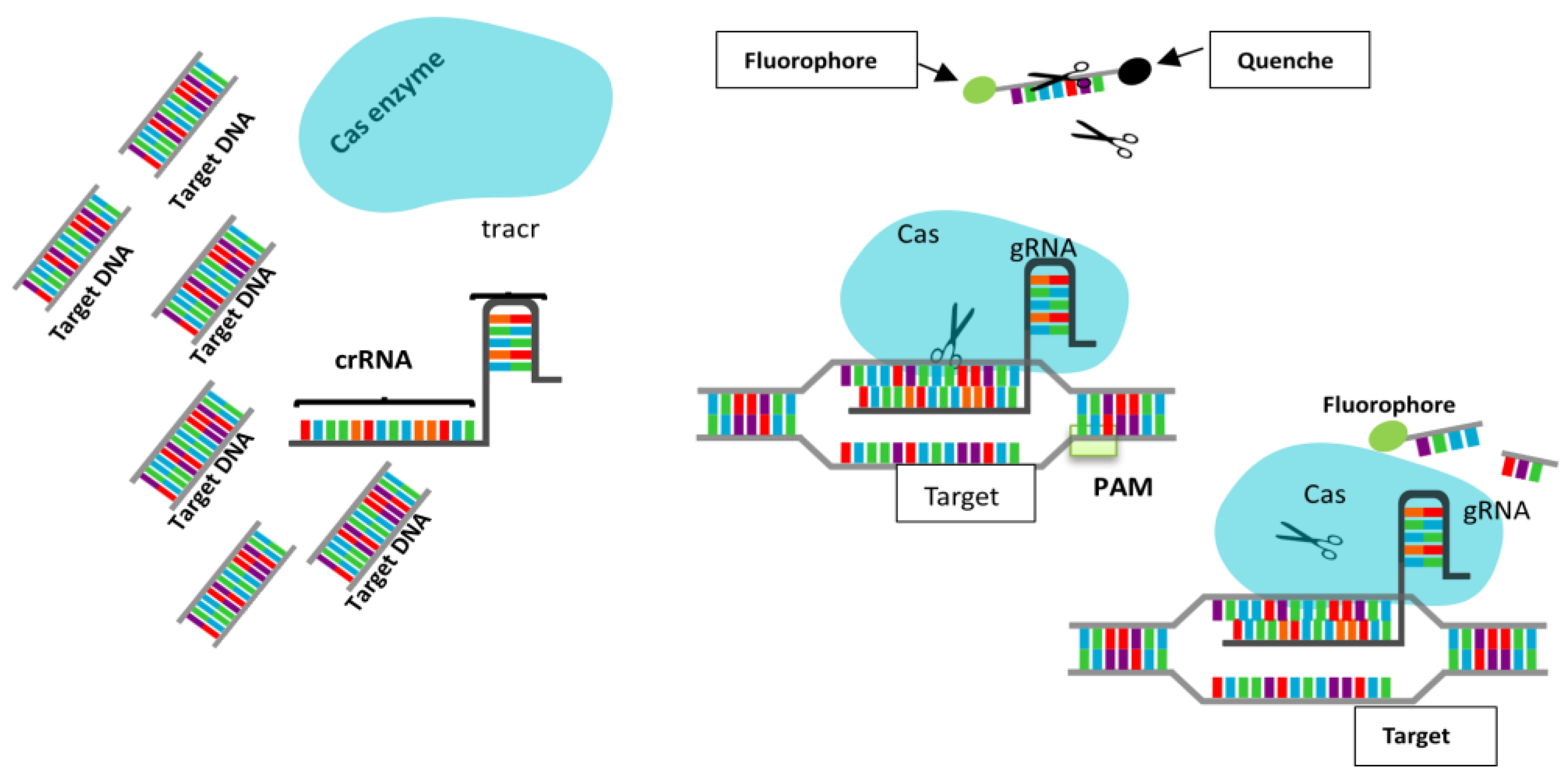

3. CRISPR-Cas12a Technology for DNA Detection

3.1. Mechanism of CRISPR-Cas12a

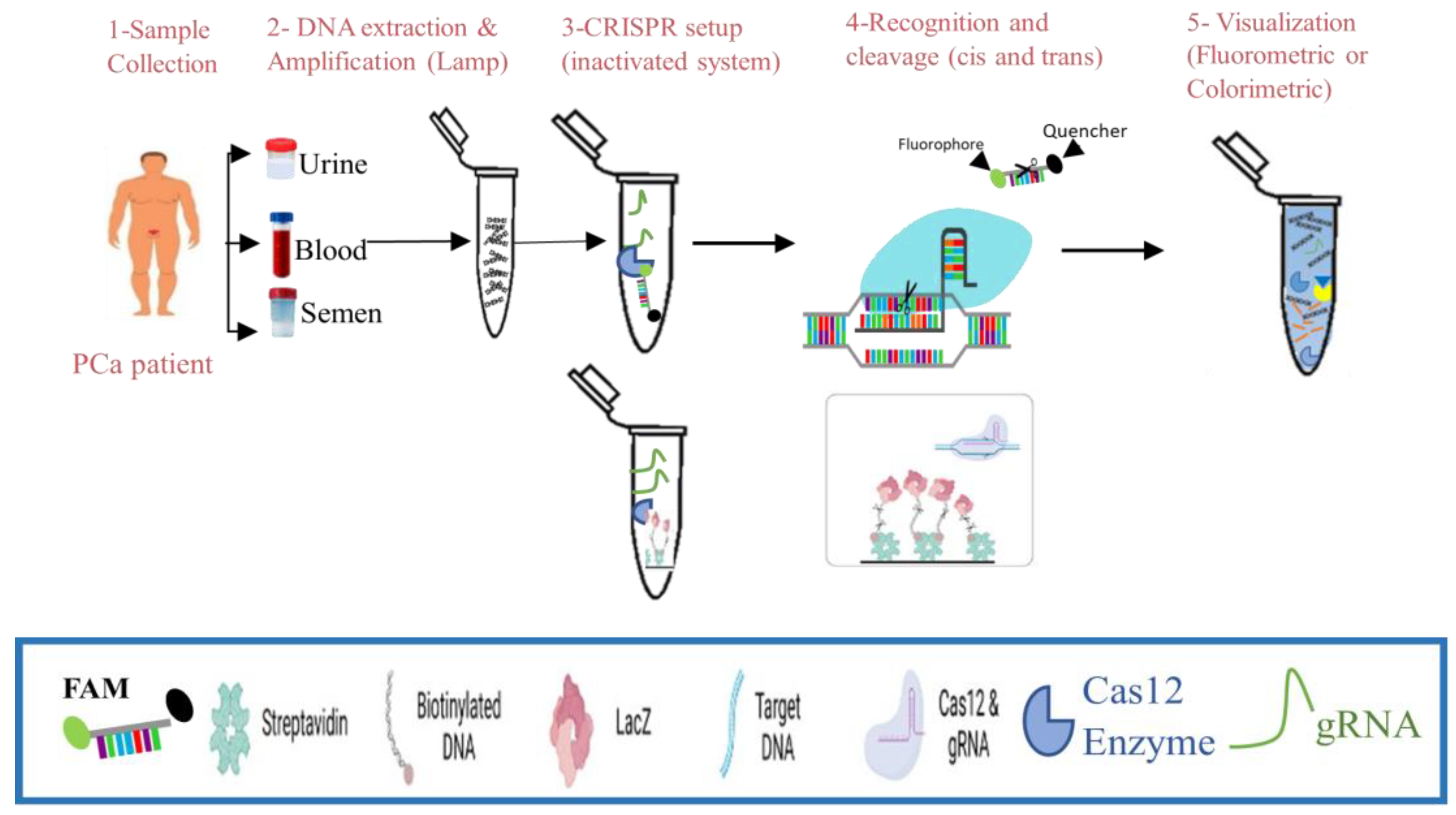

3.2. Workflow of CRISPR-Cas12a-Based Nucleic Acid Detection in Liquid Biopsies

3.3. Advances in CRISPR Diagnostics in Cancer

4. Synergistic Application: Epigenetics and CRISPR-Cas12a

4.1. Workflow Integration

4.2. Implementation in Resource-Limited Settings

5. Challenges and Considerations

Technical Challenges

6. Future Directions

7. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2021;71(3):209-249. [CrossRef]

- Jalloh M, Cassell A, Niang L, Rebbeck T. Global viewpoints: updates on prostate cancer in Sub-Saharan Africa. BJU International. 2024;133(1):6-13. [CrossRef]

- Gumenku L, Sekhoacha M, Abrahams B, Mashele S, Shoko A, Erukainure OL. Genetic Signatures for Distinguishing Chemo-Sensitive from Chemo-Resistant Responders in Prostate Cancer Patients. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2024;46(3):2263-2277. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Laversanne M, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I, Bray F. Cancer Today. 2024. Accessed April 2, 2024. https://gco.iarc.who.int/today/.

- Bello JO, Buhari T, Mohammed TO, et al. Determinants of prostate-specific antigen screening test uptake in an urban community in North-Central Nigeria. African Health Sciences. 2019;19(1):1665-1670. [CrossRef]

- Bosland MC, Shittu OB, Ikpi EE, Akinloye O. Potential New Approaches for Prostate Cancer Management in Resource-Limited Countries in Africa. Annals of Global Health. 2023;89(1). [CrossRef]

- Mbugua RG, Karanja S, Oluchina S. Effectiveness of a Community Health Worker-Led Intervention on Knowledge, Perception, and Prostate Cancer Screening among Men in Rural Kenya. Advances in Preventive Medicine. 2022;2022(1):4621446. [CrossRef]

- Rotimi SO, Rotimi OA, Salhia B. A Review of Cancer Genetics and Genomics Studies in Africa. Frontiers in Oncology. 2021;10. Accessed November 17, 2023. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.606400.

- Dumitrescu RG. Early Epigenetic Markers for Precision Medicine. In: Dumitrescu RG, Verma M, eds. Cancer Epigenetics for Precision Medicine : Methods and Protocols. Springer; 2018:3-17. [CrossRef]

- Tsou JH, Leng Q, Jiang F. A CRISPR Test for Rapidly and Sensitively Detecting Circulating EGFR Mutations. Diagnostics. 2020;10(2):114. [CrossRef]

- Zakari S, Niels NK, Olagunju GV, et al. Emerging biomarkers for non-invasive diagnosis and treatment of cancer: a systematic review. Front Oncol. 2024;14. [CrossRef]

- Sakai N. Prostate-Specific Antigen-Based Prostate Cancer Screening. In: Prostate Cancer - Leading-Edge Diagnostic Procedures and Treatments. IntechOpen; 2016. [CrossRef]

- Bae J, Kim Y. Cancer and epigenetics. Animal Cells and Systems. 2008;12(3):117-125. [CrossRef]

- Baylin SB. DNA methylation and gene silencing in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2005;2(1):S4-S11. [CrossRef]

- Ahuja N, Easwaran H, Baylin SB. Harnessing the potential of epigenetic therapy to target solid tumors. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(1):56-63. [CrossRef]

- Dawson MA, Kouzarides T. Cancer Epigenetics: From Mechanism to Therapy. Cell. 2012;150(1):12-27. [CrossRef]

- Nebbioso A, Tambaro FP, Dell’Aversana C, Altucci L. Cancer epigenetics: Moving forward. PLOS Genetics. 2018;14(6):e1007362. [CrossRef]

- Toh TB, Lim JJ, Chow EKH. Epigenetics in cancer stem cells. Mol Cancer. 2017;16(1):29. [CrossRef]

- Jin B, Li Y, Robertson KD. DNA methylation: superior or subordinate in the epigenetic hierarchy? Genes Cancer. 2011;2(6):607-617. [CrossRef]

- Zhang X, Zhang Y, Wang C, Wang X. TET (Ten-eleven translocation) family proteins: structure, biological functions and applications. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2023;8(1):297. [CrossRef]

- Puddu F, Johansson A, Modat A, et al. 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine are synergistic biomarkers for early detection of colorectal cancer. bioRxiv. Published online 2024:2024.10.30.621123. [CrossRef]

- Shi X, Zhai Z, Chen Y, Li J, Nordenskiöld L. Recent Advances in Investigating Functional Dynamics of Chromatin. Frontiers in Genetics. 2022;13. [CrossRef]

- Liu R, Wu J, Guo H, et al. Post-translational modifications of histones: Mechanisms, biological functions, and therapeutic targets. MedComm (2020). 2023;4(3):e292. [CrossRef]

- Xu Y, He Z, Du J, et al. Epigenetic modulations of immune cells: from normal development to tumor progression. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2023;19(16):5120.

- Das R, Thakur K, Shrivastava A, Puri A, Mutsuddi M. IDENTIFYING EPIGENETIC ENDPOINTS OF PESTICIDE EXPOSURE CAN CURTAIL RISK TO DEVELOP CANCER: A REVIEW. International Journal of Advanced Research. 2017;5:1093-1107. [CrossRef]

- López-Hernández L, Toolan-Kerr P, Bannister AJ, Millán-Zambrano G. Dynamic histone modification patterns coordinating DNA processes. Molecular Cell. 2025;85(2):225-237. [CrossRef]

- Nemeth K, Bayraktar R, Ferracin M, Calin GA. Non-coding RNAs in disease: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2024;25(3):211-232. [CrossRef]

- Baluchamy S, Srijyothi L, Ponne S, Prathama T, Ashok C. Roles of Non-Coding RNAs in Transcriptional Regulation. In: Kais G, ed. Transcriptional and Post-Transcriptional Regulation. IntechOpen; 2018.

- Tsai MC, Manor O, Wan Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science. 2010;329(5992):689-693.

- Conteduca V, Hess J, Yamada Y, Ku SY, Beltran H. Epigenetics in prostate cancer: clinical implications. Transl Androl Urol. 2021;10(7):3104-3116. [CrossRef]

- Majumdar S, Buckles E, Estrada J, Koochekpour S. Aberrant DNA methylation and prostate cancer. Curr Genomics. 2011;12(7):486-505. [CrossRef]

- Nakayama M, Bennett CJ, Hicks JL, et al. Hypermethylation of the human glutathione S-transferase-π gene (GSTP1) CpG island is present in a subset of proliferative inflammatory atrophy lesions but not in normal or hyperplastic epithelium of the prostate: a detailed study using laser-capture microdissection. The American journal of pathology. 2003;163(3):923-933.

- Van Neste L, Herman JG, Otto G, Bigley JW, Epstein JI, Van Criekinge W. The Epigenetic promise for prostate cancer diagnosis. The Prostate. 2012;72(11):1248-1261. [CrossRef]

- Pidsley R, Lam D, Qu W, et al. Comprehensive methylome sequencing reveals prognostic epigenetic biomarkers for prostate cancer mortality. Clinical and Translational Medicine. 2022;12(10):e1030. [CrossRef]

- Ngollo M, Lebert A, Daures M, et al. Global analysis of H3K27me3 as an epigenetic marker in prostate cancer progression. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):261. [CrossRef]

- Haider R, Massa F, Kaminski L, et al. Sirtuin 7: a new marker of aggressiveness in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(44):77309.

- Zhen L, Gui-Lan L, Ping Y, Jin H, Ya-Li W. The expression of H3K9Ac, H3K14Ac, and H4K20TriMe in epithelial ovarian tumors and the clinical significance. International journal of gynecological cancer. 2010;20(1):82-86.

- Seputra KP, Purnomo BB, Susianti H, Kalim H, Purnomo AF. miRNA-21 as reliable serum diagnostic biomarker candidate for metastatic progressive prostate cancer: meta-analysis approach. Medical Archives. 2021;75(5):347.

- Ibrahim NH, Abdellateif MS, Kassem SHA, Abd El Salam MA, El Gammal MM. Diagnostic significance of miR-21, miR-141, miR-18a and miR-221 as novel biomarkers in prostate cancer among Egyptian patients. Andrologia. 2019;51(10):e13384.

- Nip H, Dar AA, Saini S, et al. Oncogenic microRNA-4534 regulates PTEN pathway in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(42):68371.

- Sidhu S, Deep J, Sobti R, Sharma V, Thakur H. Methylation pattern of MGMT gene in relation to age, smoking, drinking and dietary habits as epigenetic biomarker in prostate cancer patients. Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology Journal. Published online 01 2010.

- Keil KP, Abler LL, Mehta V, et al. DNA methylation of E-cadherin is a priming mechanism for prostate development. Dev Biol. 2014;387(2):142-153. [CrossRef]

- Deng X, Bhagat S, Dong Z, Mullins C, Chinni SR, Cher M. Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-3 induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells and confers increased sensitivity to paclitaxel. European Journal of Cancer. 2006;42(18):3267-3273. [CrossRef]

- Jerónimo C, Henrique R, Hoque MO, et al. Quantitative RARβ2 hypermethylation: a promising prostate cancer marker. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(12):4010-4014.

- Rybicki BA, Rundle A, Kryvenko ON, et al. Methylation in benign prostate and risk of disease progression in men subsequently diagnosed with prostate cancer. International journal of cancer. 2016;138(12):2884-2893.

- Daniunaite K, Jarmalaite S, Kalinauskaite N, et al. Prognostic value of RASSF1 promoter methylation in prostate cancer. The Journal of urology. 2014;192(6):1849-1855.

- Abramovic I, Pezelj I, Dumbovic L, et al. LGALS3 cfDNA methylation in seminal fluid as a novel prostate cancer biomarker outperforming PSA. The Prostate. 2024;84(12):1128-1137. [CrossRef]

- Tokizane T, Shiina H, Igawa M, et al. Cytochrome P450 1B1 is overexpressed and regulated by hypomethylation in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(16):5793-5801. [CrossRef]

- Nowacka-Zawisza M, Wiśnik E. DNA methylation and histone modifications as epigenetic regulation in prostate cancer (Review). Oncol Rep. 2017;38(5):2587-2596. [CrossRef]

- Chu M, Chang Y, Li P, Guo Y, Zhang K, Gao W. Androgen receptor is negatively correlated with the methylation-mediated transcriptional repression of miR-375 in human prostate cancer cells. Oncology reports. 2014;31(1):34-40.

- David MK. LS. Prostate-Specific Antigen.

- Tidd-Johnson A, Sebastian SA, Co EL, et al. Prostate cancer screening: Continued controversies and novel biomarker advancements. Curr Urol. 2022;16(4):197-206. [CrossRef]

- Glinge C, Clauss S, Boddum K, et al. Stability of circulating blood-based microRNAs–pre-analytic methodological considerations. PloS one. 2017;12(2):e0167969.

- Zubakov D, Boersma AW, Choi Y, van Kuijk PF, Wiemer EA, Kayser M. MicroRNA markers for forensic body fluid identification obtained from microarray screening and quantitative RT-PCR confirmation. International journal of legal medicine. 2010;124:217-226.

- Halabian R, Valizadeh A, Ahmadi A, Saeedi P, Azimzadeh Jamalkandi S, Alivand MR. Laboratory methods to decipher epigenetic signatures: a comparative review. Cellular & Molecular Biology Letters. 2021;26(1):46. [CrossRef]

- Joo JE, Wong EM, Baglietto L, et al. The use of DNA from archival dried blood spots with the Infinium HumanMethylation450 array. BMC biotechnology. 2013;13:1-6.

- Collinson P. Evidence and cost effectiveness requirements for recommending new biomarkers. Ejifcc. 2015;26(3):183.

- García-Giménez JL, Seco-Cervera M, Tollefsbol TO, et al. Epigenetic biomarkers: Current strategies and future challenges for their use in the clinical laboratory. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2017;54(7-8):529-550. [CrossRef]

- Baden J, Adams S, Astacio T, et al. Predicting prostate biopsy result in men with prostate specific antigen 2.0 to 10.0 ng/ml using an investigational prostate cancer methylation assay. The Journal of urology. 2011;186(5):2101-2106.

- Van Neste L, Bigley J, Toll A, et al. A tissue biopsy-based epigenetic multiplex PCR assay for prostate cancer detection. BMC Urology. 2012;12(1):16. [CrossRef]

- Djomkam Zune AL, Olwal CO, Tapela K, et al. Pathogen-Induced Epigenetic Modifications in Cancers: Implications for Prevention, Detection and Treatment of Cancers in Africa. Cancers. 2021;13(23):6051.

- Oladipo EK, Olufemi SE, Adediran DA, et al. Epigenetic modifications in solid tumor metastasis in people of African ancestry. Front Oncol. 2024;14. [CrossRef]

- Moen EL, Zhang X, Mu W, et al. Genome-Wide Variation of Cytosine Modifications Between European and African Populations and the Implications for Complex Traits. Genetics. 2013;194(4):987-996. [CrossRef]

- Cronjé HT, Elliott HR, Nienaber-Rousseau C, Pieters M. Replication and expansion of epigenome-wide association literature in a black South African population. Clinical Epigenetics. 2020;12(1):6. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs A, and Ramsay M. Epigenetics and the Burden of Noncommunicable Disease: A Paucity of Research in Africa. Epigenomics. 2015;7(4):627-639. [CrossRef]

- Tristan-Flores FE, de la Rocha C, Pliego-Arreaga R, Cervantes-Montelongo JA, Silva-Martínez GA. Epigenetic Changes Induced by Infectious Agents in Cancer. In: Velázquez-Márquez N, Paredes-Juárez GA, Vallejo-Ruiz V, eds. Pathogens Associated with the Development of Cancer in Humans: OMICs, Immunological, and Pathophysiological Studies. Springer Nature Switzerland; 2024:411-457. [CrossRef]

- Kaminski MM, Abudayyeh OO, Gootenberg JS, Zhang F, Collins JJ. CRISPR-based diagnostics. Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5(7):643-656. [CrossRef]

- Pascual-Garrigos A, Lozano-Torres B, Das A, Molloy JC. Colorimetric CRISPR Biosensor: A Case Study with Salmonella Typhi. ACS Sens. Published online February 5, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Shao N, Han X, Song Y, Zhang P, Qin L. CRISPR-Cas12a Coupled with Platinum Nanoreporter for Visual Quantification of SNVs on a Volumetric Bar-Chart Chip. Anal Chem. 2019;91(19):12384-12391. [CrossRef]

- Zhou H, Tsou JH, Leng Q, Jiang F. Sensitive Detection of KRAS Mutations by Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats. Diagnostics. 2021;11(1):125. [CrossRef]

- Costa-Pinheiro P, Montezuma ,Diana, Henrique ,Rui, and Jerónimo C. Diagnostic and Prognostic Epigenetic Biomarkers in Cancer. Epigenomics. 2015;7(6):1003-1015. [CrossRef]

- Qu H, Zhang W, Li J, et al. A rapid and sensitive CRISPR-Cas12a for the detection of Fusobacterium nucleatum. Microbiology Spectrum. 2024;12(2):e03629-23. [CrossRef]

- Parveen S, Rizvi SF, Hasan A, Afaq U, Mir SS. Novel Insights into Epigenetic Control of Autophagy in Cancer. OBM Genetics. 2022;6(4):1-45. [CrossRef]

- Tsou JH, Leng Q, Jiang F. A CRISPR Test for Detection of Circulating Nuclei Acids. Translational Oncology. 2019;12(12):1566-1573. [CrossRef]

- Van Dongen JE, Berendsen JTW, Eijkel JCT, Segerink LI. A CRISPR/Cas12a-assisted platform for identification and quantification of single CpG methylation sites. Published online April 6, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sun Y, Wen T, Zhang P, Wang M, Xu Y. Recent Advances in the CRISPR/Cas-Based Nucleic Acid Biosensor for Food Analysis: A Review. Foods. 2024;13(20):3222. [CrossRef]

- Qiu M, Zhou XM, Liu L. Improved Strategies for CRISPR-Cas12-based Nucleic Acids Detection. J Anal Test. 2022;6(1):44-52. [CrossRef]

- Xiong Y, Zhang J, Yang Z, et al. Functional DNA Regulated CRISPR-Cas12a Sensors for Point-of-Care Diagnostics of Non-Nucleic-Acid Targets. J Am Chem Soc. 2020;142(1):207-213. [CrossRef]

- Lucia C, Federico PB, Alejandra GC. An ultrasensitive, rapid, and portable coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 sequence detection method based on CRISPR-Cas12. Published online March 2, 2020:2020.02.29.971127. [CrossRef]

- Chen W, Wu S, Li G, et al. Accurate diagnosis of prostate cancer with CRISPR-based nucleic acid test strip by simultaneously identifying PCA3 and KLK3 genes. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2023;220:114854. [CrossRef]

- Dong J, Feng W, Lin M, et al. Comparative Evaluation of PCR-Based, LAMP and RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a Assays for the Rapid Detection of Diaporthe aspalathi. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024;25(11):5773. [CrossRef]

- Etemadzadeh A, Salehipour P, Motlagh FM, et al. An Optimized CRISPR/Cas12a Assay to Facilitate the BRAF V600E Mutation Detection. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 2024;38(21):e25101. [CrossRef]

- Wu P, Cao Z, Wu S. New Progress of Epigenetic Biomarkers in Urological Cancer. Disease Markers. 2016;2016(1):9864047. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Zhan L, Qin Z, Sackrison J, Bischof JC. Ultrasensitive and Highly Specific Lateral Flow Assays for Point-of-Care Diagnosis. ACS Nano. 2021;15(3):3593-3611. [CrossRef]

- Hattori N, Ushijima T. Epigenetic impact of infection on carcinogenesis: mechanisms and applications. Genome Med. 2016;8(1):10. [CrossRef]

- Moetlhoa B, Nxele SR, Maluleke K, et al. Barriers and enablers for implementation of digital-linked diagnostics models at point-of-care in South Africa: stakeholder engagement. BMC Health Services Research. 2024;24(1):216. [CrossRef]

- Gul I, Raheem MA, Reyad-ul-Ferdous Md, et al. CRISPR diagnostics for WHO high-priority sexually transmitted infections. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2025;182:118054. [CrossRef]

- Lau A, Ren C, Lee LP. Critical review on where CRISPR meets molecular diagnostics. Prog Biomed Eng. 2020;3(1):012001. [CrossRef]

- Azhar Mohd, Phutela R, Kumar M, et al. Rapid and accurate nucleobase detection using FnCas9 and its application in COVID-19 diagnosis. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2021;183:113207. [CrossRef]

- Javalkote VS, Kancharla N, Bhadra B, et al. CRISPR-based assays for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2. Methods. 2022;203:594-603. [CrossRef]

- Tyumentseva M, Tyumentsev A, Akimkin V. CRISPR/Cas9 Landscape: Current State and Future Perspectives. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023;24(22):16077. [CrossRef]

- Su J, Ke Y, Maboyi N, et al. CRISPR/Cas12a Powered DNA Framework-Supported Electrochemical Biosensing Platform for Ultrasensitive Nucleic Acid Analysis. Small Methods. 2021;5(12). [CrossRef]

- Li C, Lin N, Feng Z, et al. CRISPR/Cas12a Based Rapid Molecular Detection of Acute Hepatopancreatic Necrosis Disease in Shrimp. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 2022;8. [CrossRef]

- Dai X, Shen L. Advances and Trends in Omics Technology Development. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:911861. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y, Lyu J, Han J, et al. A specific and ultrasensitive Cas12a/crRNA assay with recombinase polymerase amplification and lateral flow biosensor technology for the rapid detection of Streptococcus pyogenes. Microbiology Spectrum. 2024;12(10). [CrossRef]

- Hu M, Qiu Z, Bi ZR, Tian T, Jiang Y, Zhou X. Photocontrolled crRNA activation enables robust CRISPR-Cas12a diagnostics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2022;119(26). [CrossRef]

- Tan M, Liang L, Liao C, et al. A rapid and ultra-sensitive dual readout platform for Klebsiella pneumoniae detection based on RPA-CRISPR/Cas12a. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2024;14. [CrossRef]

- Chilunga FP, Henneman P, Venema A, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis on C-reactive protein among Ghanaians suggests molecular links to the emerging risk of cardiovascular diseases. npj Genom Med. 2021;6(1):1-9. [CrossRef]

- Harlemon M, Ajayi O, Kachambwa P, et al. A Custom Genotyping Array Reveals Population-Level Heterogeneity for the Genetic Risks of Prostate Cancer and Other Cancers in Africa. Cancer Research. 2020;80(13):2956-2966. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Qian F, Zheng Y, et al. Genetic variants demonstrating flip-flop phenomenon and breast cancer risk prediction among women of African ancestry. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;168(3):703-712. [CrossRef]

| Parameter | CRISPR-Cas12a | qPCR | Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (as low as 100 fM); enhanced by collateral cleavage [92] | Moderate–High; dependent on primer/probe design and efficiency | Very High; resolution dependent on sequencing depth [94] |

| Cost | Low to moderate; suitable for resource-limited settings [95] | Moderate; less expensive than NGS, but not easily multiplexed [93] | Highly costly reagents, equipment, and bioinformatics [94] |

| Speed | <2 hours ideal for point-of-care [96] | ~1–2 hours real-time readout | Slow (days); long prep and data analysis [94] |

| Scalability | Moderate; being improved for high-throughput screening | Low to moderate; limited multiplexing | Very High; excellent for large sample sets [94] |

| Required Infrastructure | Minimal; no need for complex equipment [97] | Basic molecular lab setup(thermocycler) | High-end sequencing and data analysis infrastructure required [94] |

| Suitability for Resource-Limited Settings | Excellent, portable and cost-effective | Moderate; requires thermal cycler | Poor, impractical without advanced infrastructure |

| Methylation Detection | Emerging; can detect methylation via enzyme-based pre-treatment + CRISPR [75] | Possible with Me-PCR or qMSP; limited to known targets | Comprehensive; can map genome-wide methylation [94] |

| miRNA Detection | Achievable using Cas12a/crRNA targeting mature miRNA; under development | Well established with TaqMan or SYBR Green assays | High-resolution profiling of the entire miRNome |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).