Introduction

Decisions are ubiquitous in everyday life. Choosing what, when, and how much to eat, whether to drink alcohol, when and when not to take prescription medications, whether to try illicit drugs, whether to drive recklessly, and whether to call your mother on her birthday are all examples of choices that can significantly impact individual well-being. Decisions are not only the linchpins of behavior in everyday life, they are the driving force behind most of the data collected in, not only the decision neuroscience laboratory, but almost all psychology laboratories, including those studying animal models of behavior. Therefore, how and why people make the choices they do is important for improving well-being, but it is also important for answering fundamental questions about cognitive science, philosophy of mind, and clinical diagnoses.

Using “choice” and “decision” interchangeably in the above paragraph was done intentionally to provoke some consideration of the usage and definition of them as terms that describe not only behavior, but also mental states and their underlying mechanisms. In common usage, decision and choice are interchangeable and this is also the tendency in decision neuroscience. However, decision and choice have different dictionary definitions and also distinct definitions in philosophy (Nowell-Smith, 1958). A decision is a determination made after some consideration, whereas a choice is the act of selecting between options. More specifically, a decision refers only to the internal phenomenon experienced by the actor, whereas a choice always involves an overt action that may also be accompanied by an internal experience (Schall, 2001). Decisions are private, mental phenomena, whereas choices involve actions and can be observed. Widespread acceptance of the conflated definition has led neuroscientists to codify certain assumptions about the underlying neural mechanisms of decisions/choices.

The purpose of this paper is to establish a new direction for decision neuroscience. Decision neuroscience is a very broad field that spans a large variety of mental phenomena and behaviors (Serra, 2021). Therefore, it is important to specify that this paper will address the part of decision neuroscience that uses relatively simple tasks to study what have been called “classic decisions” (Gordon et al., 2021). More complex tasks that involve lengthy intervals of reasoning, simulating, or problem solving are outside the purview. Section 1 reviews four common assumptions about the mechanisms of classic decisions. Section 2 contrasts classic decisions with “embodied decisions” to pose challenges to the four assumptions. Section 3 dissects how cognitive/decision neuroscience theories confuse and misrepresent mental/psychological phenomena, behavior/action, and neural mechanisms/systems. Section 4 examines logical fallacies about cause and effect in cognitive/decision neuroscience theory. Section 5 applies the lessons of sections 2-4 to describing a new approach to theorizing for decision neuroscience.

1) Assumptions based on classic decisions

An over-reliance on classic decisions for theorizing and experimentation in neuroscience has led to several theoretical assumptions, of which four will be examined. Principle among these assumptions is that classic decisions occur in

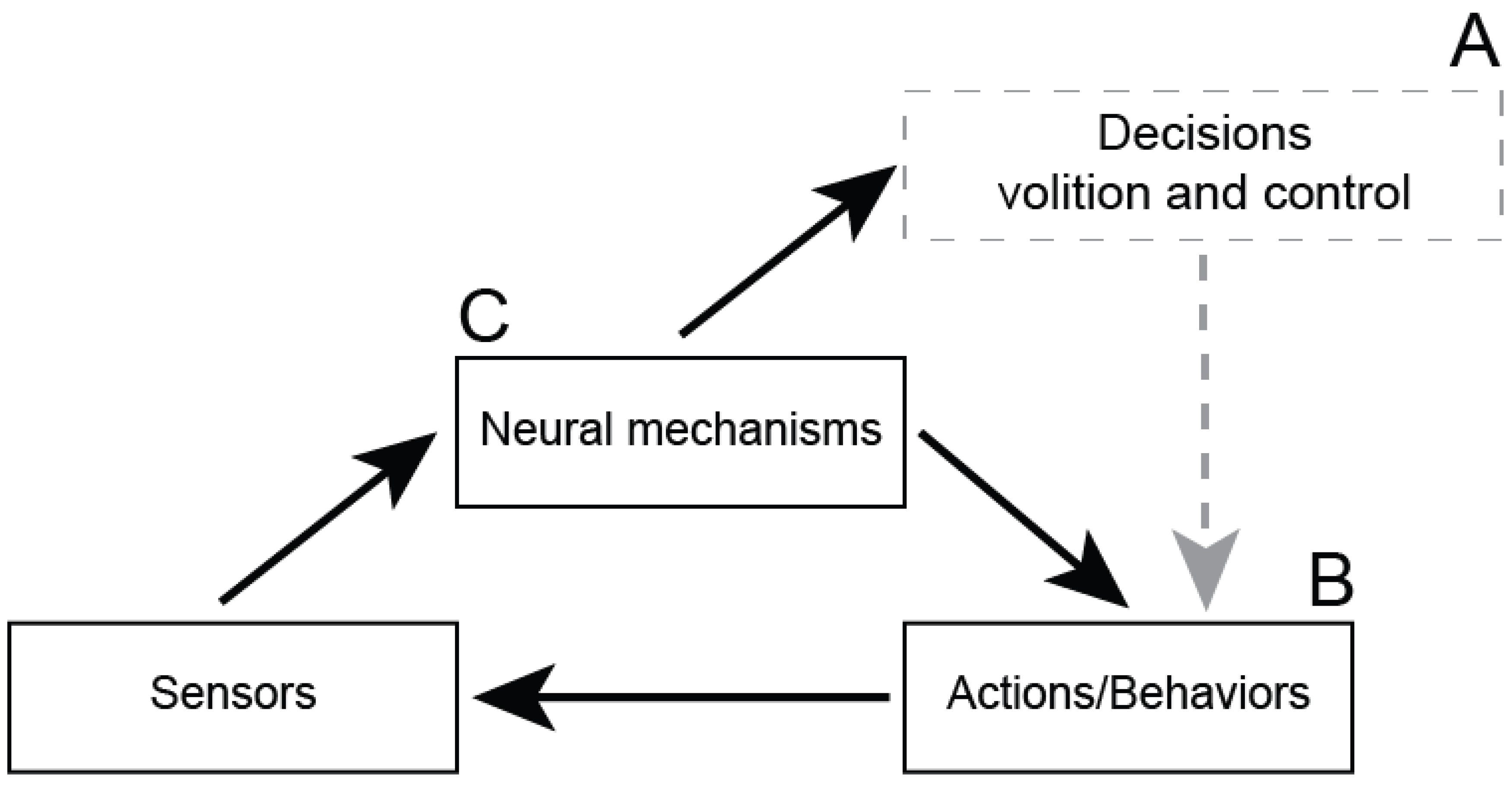

discrete processing stages (Fodor, 1983; Miller, 1988; Pylyshyn, 1980; Sternberg, 1969). At the most general level, these discrete processes would be sensation/perception, cognition/decision making, and action/motor output (

Figure 1). In robotics, this model is called sense-think-act or sense-decide-act (Cisek, 1999; Pfeifer & Verschure, 1992). The separation of sensory, cognitive (understanding), and motor function can be traced back to Alcmaeon of Croton in sixth century BCE and to Aristotle’s “rational psyche” and “sensitive psyche” (Celesia, 2012; Hurley, 2001; Vanderwolf, 1998). More recently, these separations have been referred to as the “sandwich” model of the mind (Hurley, 2001, 2008).

The second assumption is linear causality. The assumed discrete stages of processing, sense, think, and act, are further assumed to occur in a linearly-causal sequence. This assumption was emphasized in the work of “behaviorists” in the early 1900s, who adopted a strictly linearly-causal, stimulus-response experimental paradigm that clung tightly to a theoretical sense-act model of behavior (Guerin, 2024; Watson, 1913). Although the cognitive revolution was highly critical of many behaviorist doctrines—notably, it put the “think” back into sense-think-act -- one that they embraced was linear causality (Hurley, 2001). Discrete processes (or modules) were thought to interact based on proscriptive rules that allowed their interactions to be described similar to computer programs, which also operated in a linearly-causal sequence at the time (Fodor, 1983; Newell & Simon, 1959; Pylyshyn, 1980). Like Aristotle’s psyches, cognitivism considered that sensing, thinking, and acting were not only discrete processing stages, but also occurred in a strictly linearly-causal sequence of sense, then-think, then-act.

A third assumption is internal representation. Motivation for internal representation was a secondary assumption that the impoverished nature of stimuli necessitated a kind of innate “knowledge” to scaffold learning from sensory signals (Guerin, 2024). Chomsky’s universal grammar and language acquisition device were early examples (Chomsky, 1959). Later contributors like Fodor described all of cognition as the “language of thought” and coined the phrase “modularity of mind” (Fodor, 1975; Fodor, 1983). The study of “perception” as distinct from action presupposes that the goal of perception is to internally represent the external world (Skinner, 1985). Likewise, the study of “memory” is the study of how sensory data are encoded, transformed, stored, and consolidated in internal representations that are able to be recovered, retrieved, and reconsolidated (Squire et al., 2004; Sridhar et al., 2023). Pylyshyn applied these same ideas to decision making, claiming that decisions cannot be based on raw sensory data, but instead must be based on meaningful internal representations of the outside world constructed from the raw data (Pylyshyn, 1980; Pylyshyn, 1984).

Most cognitive models -- sequential sampling, reinforcement learning, Bayesian, to name a few large classes of models—assume that sensory data are internally represented (Ma, 2019; Russo et al., 2018; Shakya et al., 2023). Motor command theories also rely on internal representations, with efference copy being used to produce corollary discharge, which is a sensory estimate derived by transformation of one internal representation into another (Floegel et al., 2023; Grünbaum & Christensen, 2024; Wolpert & Ghahramani, 2000). Marr’s model of object perception, which continues to inspire researchers in computational vision science, contends that raw visual data is transformed multiple times into multiple different internal representations before objects can be meaningfully represented in three-dimensions (Marr, 1982). Although the connectionist movement of the 1980s refuted that representations must be symbolic, they did not refute that internal representations were necessary (Pfeifer & Verschure, 1992; Raja & Anderson, 2019).

Internal representations are a key premise of almost all cognitive neuroscience theories, including models of object, word, face, and scene recognition (Downing et al., 2006; Kanwisher, 2014); the distinction between dorsal and ventral streams for perception and action (Arnott et al., 2004; Goodale & Humphrey, 1998; James et al., 2003; James et al., 2007); and especially work on memory systems (Squire et al., 2004; Sridhar et al., 2023; Tulving & Schacter, 1990). Decision neuroscience theories make extensive use of representations for many variables that are computed from sensory data and represented in different brain regions, including value, utility, errors, salience, uncertainty, and others (Dennison et al., 2022; Gold & Shadlen, 2007; Menon & Uddin, 2010; Smith & Huettel, 2010).

The fourth assumption is that classic decisions are volitional. Discussions of volition and intention date back to at least Aristotle’s concept of the “rational psyche” (located physically in the heart) that gave humans their “will” or ability to think and reason and then choose between courses of action (Celesia, 2012). The “rational psyche”—the “think” in sense-think-act -- was considered separate from the “sensitive psyche,” which was responsible for perception (sense) and action (act). That classic decisions are volitional is still tightly linked to the sense-think-act model, where the positioning of “thinking” as a discrete processing stage that always precedes action presupposes that thinking causes action and that the actor is in control. This conception of volition as control of action is tightly aligned with constructs in psychology like self-control, self-regulation, cognitive control, and executive function (Alvarez & Emory, 2006; Braver, 2012; Diamond, 2013; Heatherton, 2011; Koechlin et al., 2003; Miyake et al., 2000). All of these concepts rely heavily on the premise of a high-level, top-down, central controller that executes commands to lower-level, bottom-up sensory and motor modules (Crapse & Sommer, 2008; Eisenreich et al., 2017; Warren, 2006).

In summary, decision neuroscience theories are based almost solely on classic decisions. The definition of classic decision conflates the definitions of decision and choice -- of internal, private deliberation with external, observable action. Not only is this confusing, it neglects the study of choice behavior that does not involve deliberation. This has led to decision neuroscience theories codifying four common assumptions about classic decisions: 1) they involve discrete processing stages, 2) the stages are linearly causal, 3) they involve internal representations, and 4) they are volitional. These four assumptions are all consistent with the cognitivist ideology that brains represent the external world and perform computations on those representations to produce behavior (Newell & Simon, 1959; Sejnowski et al., 1988). The conclusion is that decision neuroscience theories are almost entirely based on various forms of cognitivism, computationalism, or rationalism, rather than other perspectives.

2) Challenges to “classic decision” assumptions

The core ideas behind the four assumptions of classic decisions originated before the common era and survived largely unchanged to the time psychology became a field. Since then, all of them have been challenged to some degree. The earliest counter theories were actually reactions to behaviorism and developed in parallel with cognitivism and computationalism (Guerin, 2024). Examples are Gibson’s ecological psychology, from which much of embodied cognition has sprung (Bingham, 1988; Gibson, 1966; Turvey & Carello, 1986; Warren, 2006), and the cybernetics movement (Rosenblueth et al., 1943; Wiener, 1948) of which a particularly potent version was Powers’ perceptual control theory (Powers, 1973a, 1973b; Powers et al., 1960). A later surge of anti-computationalist views emerged around the early 1990s, having in common that they were mostly built on ecological or embodied principles and also invoked some form of dynamical systems theory (Beer, 1995; Brooks, 1986; Diedrich & Warren, 1995; Hendriks-Jansen, 1996; Marken & Powers, 1989; Pfeifer & Verschure, 1992; Skarda & Freeman, 1987; Thelen & Smith, 1994; Van Gelder & Port, 1995). Despite the constant challenges, the four assumptions remain dominant themes in almost all decision neuroscience theories. One reason for this may be the emphasis on classic decisions in experimentation.

While classic decisions have been the focus of study in decision neuroscience, other kinds of choices have been neglected. A recent article labels these less-studied kinds of actions/choices “embodied decisions” (Gordon et al., 2021). “Embodied” refers to explanations of behavior put forward by the embodied cognition movement in cognitive science (Raja & Anderson, 2019; Thelen & Smith, 1994; Wilson & Golonka, 2013), but similar distinctions have been made using different terms (Cisek, 2019; Pessoa et al., 2021). To illustrate the difference between classic and embodied decisions, imagine choosing to order an item at a restaurant by pointing to it on the menu. Determining an item to order seems to follow the cognitivist processing stages of sense-think-act: read multiple item descriptions from the menu (sense), deliberate about which will lead to the best meal (think), point to the item you decided (act). However, while reading the items, you likely made dozens of eye movements and each of those movements was an action that required selecting among multiple options, that is, each was a choice (Gordon et al., 2021; Muller et al., 2024; Schall, 2001). Further, while moving your arm to point at the menu, your core muscles were acting to keep your torso in an upright posture despite being unbalanced by the shifting weight of the arm. Those postural adjustments also reflect choices from among almost infinite options. If we consider that hundreds of embodied decisions can be made in the time it takes to deliberate about one classic decision, it could be argued that, due to their sheer majority, embodied decisions are just as important, if not more important, to understanding behavior than classic decisions.

The most obvious difference between classic and embodied decisions is that classic decisions feel volitional. The behaviorists simply avoided questions of volition; they theorized that actions were caused by stimuli. The cognitivists reintroduced volition, conceptualizing it as a central controller or executive. Sensing was considered passive and the cause of action was taken out of the environment and put inside the organism as “thinking.” This introduced two problems, 1) the troubling recursive concern of a “little man” as the central controller or cause of volitional action (Braver, 2012) and 2) it provided no rationale for how nonvolitional, reflexive movements (embodied decisions) were caused (Gordon et al., 2021). Cybernetics had already proposed a likely solution that appears to have been ignored by cognitivists (Powers et al., 1960). What distinguishes living things from non-living is that their actions are purposeful. A rock falling down a hill has no means of resisting, of controlling its environment. On the other hand, organisms are purposeful and use behavior to control their environment. Actions are reflexes in negative feedback loops that rely on internal set points that are updated based on changes in the environment. Actions appear to be goal-directed not because of explicit internal goal-states, but because actions are continually adjusting sensed environmental variables (“percepts”) to match internal set points (reference inputs). Ecological psychology has similar ideas, considering that actions are as much for sensing as sensing is for acting (Gibson, 1966). Organisms are constantly using action (exploring) to uncover new sensory patterns that are useful for survival. If all sensing and acting is purposive, then proposing a “little man” as the cause of only “volitional” actions is unnecessary.

On the surface, discrete processing of sensory, cognitive, and motor information seems intuitive. At the least, sensors do something different from muscles (actuators), and the neurons in between sensors and muscles do something different again. But, this is not the same as theorizing that perception is supported by different systems from cognition and from action. An even larger problem is that the mental constructs themselves are intertwined and overlapping, not discrete. For example, object recognition is usually considered a perceptual processes, whereas categorization is usually considered a cognitive process, even though object recognition and cognition share many characteristics (Palmeri & Gauthier, 2004). Trying to place constructs such as attention and memory within any one discrete processing stage causes even more confusion. In response, the attempt to classify the neural transactions between sensors and muscles into discrete processing stages has started to give way to more continuous models of information flow (McKinstry et al., 2008). Nevertheless, the idea that perception, cognition, and action are discrete processes persists.

It is worthwhile noting that a testing environment where actions are temporally-contingent on stimulus presentation cannot disconfirm the linear causality assumption, it can only reify it (Anderson, 2011; Marken, 1980). Constrained experimental environments hide the fact that acting-to-sense can be as important as sensing-to-act (Gibson, 1966; Guerin, 2024; Pleskac & Hertwig, 2023; Turvey & Carello, 1986). Actions in naturalistic environments are used to provide important updates to sensory information. These simultaneous dynamic relations between sensing and acting are impossible to describe using a linearly-causal model like sense-think-act. However, researchers studying classic decisions have been able to ignore the impact of acting-to-sense, because the classic decision experiment environment does not allow interaction with dynamic stimuli and does not allow the subject any agency. Studies in more naturalistic environments, where sensing and acting co-inform each other, show that choices are better described as simultaneously or circularly causal, not linearly causal (Marken & Powers, 1989; Pleskac & Hertwig, 2023).

That internal representations are necessary for behavior has been disputed since before they were first proposed (Guerin, 2024). Most vocal among its critics have been the ecological psychologists, who are echoed by many proponents of embodied cognition. These critics emphasize that the synergy among the brain, body and environment alleviates the need for internal representations (Beer, 1995; Brooks, 1986; Diedrich & Warren, 1995; Gibson, 1966; Thelen & Smith, 1994; Turvey & Carello, 1986; Wilson & Golonka, 2013). Walter Freeman and Christine Skarda tell an intriguing story in one of their papers that, only after discarding the idea of representations, were they able to make progress in understanding the dynamic neural mechanisms involved in olfaction (Freeman & Skarda, 1990). Another challenge is that maintaining internal representations of the external world is computationally impossible without a host of accommodations (Guerin, 2024; Raja & Anderson, 2019). The ecological perspective, in which sensing and acting co-inform, can account for most, if not all, of the answers that internal representations provide, but does not require any of the computational accommodations that internal representations need (Pfeifer & Verschure, 1992; Raja & Anderson, 2019). Although it is too detailed to recite here, Hendricks-Jansen provides one of the best arguments against internal representations (and the computational account more generally), finishing with “an adequate answer requires an abandonment of all attempts to seek explanatory principles or entities inside the creature’s head.” He concludes that behavior can only be understood by examining an organism’s evolutionary and developmental history (Hendriks-Jansen, 1996). Finally, the term “representation” in contemporary psychology, philosophy, and neuroscience, has many different meanings that are not agreed on, making the term “epistemically sterile” (Favela & Machery, 2023, 2025; Pessoa et al., 2021). In sum, internal representations are theoretically unlikely and unnecessary, their current definition is unclear, and their use in theory has impeded scientific progress.

3) Neural mechanisms and mental phenomena

The four assumptions are also part of even deeper theoretical problems. Similar to other areas of cognitive neuroscience, most decision neuroscience theory is borrowed from philosophy of mind and cognitive science, almost exclusively from cognitivist traditions. As a result cognitive neuroscience experiments use behavior as a proxy for mental phenomena (Hommel, 2020; Pessoa et al., 2021; Vanderwolf, 1998). This practice can lead to confusion about the roles and definitions of mental/psychological phenomena, behavior/action, and neural mechanisms/systems. In almost all cases, decision neuroscience studies involve creating a task where specific, constrained behaviors or actions (observable) are used as markers of mental phenomena (unobservable) and are correlated with activation in brain regions. Thus, activation in brain regions is interpreted as the “neural mechanism” of a mental phenomenon (Hommel, 2020; Ross & Bassett, 2024; Westlin et al., 2023). Using behaviors as markers of mental phenomena may be somewhat reliable in the constrained lab setting, but an unanswered question is whether this generalizes to real environments. Beyond that, this approach has provoked significant debate in the field about whether cognitive neuroscience theories are even about neural mechanisms and whether neural activation can tell us anything about mental or psychological phenomena (Buzsáki & Tingley, 2023; Coltheart, 2006; Hommel, 2020; Pessoa et al., 2021; Ross & Bassett, 2024; Vanderwolf, 1998; Vanderwolf, 2001).

An excellent historical example, based on brain injury rather than brain activation, is from the study of memory in neuropsychology. In the 1960s, new observations demonstrated that patients with amnesia -- like patient H.M. and others who had bilateral injury or removal of the medial temporal lobe—could improve a motor skill with practice, even though they couldn’t remember practicing (Milner et al., 1968; Penfield & Milner, 1958). At the time, memory phenomena were considered to be underpinned by a unitary memory system. The response to the new observations was to fractionate memory into two sub-phenomena, things that H.M. could do, labeled “implicit” memory, and things H.M. could not do, labeled “explicit” memory. On the surface, there is nothing wrong with categorizing mental phenomena—categorization is an effective tool used throughout the sciences. Importantly, though, it is common in cognitive neuroscience to assume one-to-one mappings of mental phenomena onto brain regions and to consider that link a “neural mechanism” (Hommel, 2020; Westlin et al., 2023). Thus, not only were memory phenomena categorized into explicit and implicit memory sub-phenomena, it was assumed that separate implicit and explicit neural systems/mechanisms were necessary to support them. This approach may not necessarily be wrong. What is wrong is that fractionation of underlying neural mechanisms based on categorization of mental phenomena has become a staple in cognitive neuroscience, causing a proliferation of theories about not only memory, but other phenomena, including attention and executive function (Alvarez & Emory, 2006; Anderson, 2011; Diamond, 2013; Hommel et al., 2019; Miyake et al., 2000).

A network model of insula function (Menon & Uddin, 2010) provides an example of a modern theory that has had a significant impact on decision neuroscience (it has more than 6000 citations) and is still archetypal (Molnar-Szakacs & Uddin, 2022; Uddin et al., 2019). It proposes that the anterior insula and other regions of the “salience” or midcingulo-insular network perform a switching function between the regions of the “central executive” or lateral frontoparietal network and the “default mode” or medial frontoparietal network. This theory is clearly about mental phenomena, i.e., salience, executive function, and “dynamic reconfiguration of associative representations based on current goal-states.” The neural mechanisms invoked are one-to-one mappings between the mental phenomena and brain regions. However, that the lateral frontoparietal network is a central executive, that the insula is for salience, and that the medial frontoparietal network is for mind wandering (to choose just one of the myriad mental phenomena the medial frontoparietal network has been assigned as its function), provides little insight into the actual neural mechanisms that are responsible for executive function, mind wandering, or salience. Cognitive neuroscience theories almost uniformly specify underlying neural mechanisms that are just reflections of the mental phenomena they are supposed to support, as if the mental states were echoes of the physical states (Hendriks-Jansen, 1996; Hommel, 2020). This practice has many negative impacts. First, it confuses the role of mental phenomena with actual neural mechanisms (Hommel, 2020; Westlin et al., 2023). Second, it insinuates that studying mental phenomena is the only means to study behaviors (Hommel, 2020; Pessoa et al., 2021). Finally, it reifies the claim that mental phenomena are the causes of behavior (Anderson, 2011; Hommel, 2020).

4) The causes of behaviors and mental phenomena

This brings us to another problem with cognitive neuroscience theorizing, that the confusions between mental phenomena, behaviors, and neural mechanisms are often specifically at odds with a perspective likely held by most neuroscientists, that of physicalism. The philosophical view of physical reductionism (also reductive physicalism) is that all phenomena, including mental phenomena, can be understood in terms of the laws of physics. The alternative view would be one of the forms of dualism, that mental phenomena and behavior are caused by something non-physical, like a mind or soul. Physicalists can also believe in a mind or soul, but it cannot be causally related to physical things, like behavior. To be clear, physicalism is not reductionism, that understanding of complex things is best achieved by studying their simpler parts. Trying to explain behavior and mental phenomena in terms of only the interactions among the brain, body, and environment is not reductionist, it is physicalist.

Within neuroscience, we can define physical things as bodies and brains, the sensors and muscles in bodies and the neurons in brains. Electromagnetic radiation, volatile chemicals, tendon stretch, and other “energies” in the environment that the body’s sensors transduce are also physical. Actions are physical and so choices are physical, because they involve action, but decisions and other private, mental phenomena are not physical. Just because phenomena are non-physical does not mean they cannot be understood from a physicalist perspective. The key difference between physicalism and dualism (with respect to philosophy of mind) is that physicalism seeks to understand mental phenomena like decisions with only physical transactions among the brain, body, and environment, whereas dualism allows causation by additional, non-physical substances.

For a physicalist, the causes of behavior can be described like this: the environment/body causes signals in sensors that cause activity in neurons that activate more neurons (and then maybe even more neurons) that cause contractions of muscles that cause actions. Note that ecological psychologists (who are likely also mostly physicalists) would warn against the assumption of linear causality and emphasize that actions also simultaneously cause changes to the body and environment that cause important changes in the signals in sensors, and so on. Either way, the key point is that behavior (action) is caused by physical things or, more specifically, it is the result of a causal sequence of physical transactions.

Decision neuroscience needs to theorize not only about physical transactions and the role of behavior, but also about the role of mental phenomena, otherwise it could face the same criticisms that behaviorism faced (Eliasmith, 2003). In his attempt to explain mentalistic constructs like the self and consciousness, Dennett proposed an analogy for the role of mental phenomena based on the abstract construct of a center of gravity (Dennett, 1992). That analogy will be elaborated here to include mental phenomena, behaviors/actions, and neural mechanisms (

Figure 2). An object, which is physical, has many physical properties, but also some non-physical. The spatial relations among its parts, the distances, angles, mass, and so forth, are physical properties. The center of gravity is an example of a non-physical property, it exists only as an abstract description of the object itself or the object’s spatial relations of parts. Moving a part of the object (a physical transaction)

causes a change to the spatial relations of parts (a physical effect) and also

causes a change to the center of gravity (a non-physical effect). Dennett emphasized that physical transactions

cause non-physical effects, but the reversed premise, that non-physical effects cause physical transactions, is considered a category mistake, a type of logical fallacy (Dennett, 1992; Ryle, 1949). In other words, the only way to change an object’s center of gravity is to make a change to the object. The object

cannot be changed by changing its center of gravity. To generalize, changes to non-physical entities are always an

effect of changes to physical entities; changes to non-physical entities cannot cause changes to physical entities.

Relating this analogy to decision neuroscience, the causal sequence of physical transactions (environment, sensors, neurons, muscles) that produces behavior is analogous to the “object.” A decision is analogous to the object’s center of gravity; it is a description of the physical neural transactions. Changing a single neural transaction causes changes throughout the sequence of (physical) neural transactions that causes a difference in (physical) behavior. This is analogous to changing the relative spatial relations among parts of the object. Changing neural transactions also causes changes in one’s mental experience, for instance, whether a decision was made or not and, if so, what decision was made. Importantly, despite the illusion that decisions cause actions, it is actually that decisions and actions are both effects of neural transactions. Decisions and actions are often highly correlated, but decisions don’t cause actions; decisions and actions are both caused by a third variable, the neural mechanisms. Within the physicalist view, considering a decision (non-physical) to be the cause of an action (physical) or any of the other physical transaction is a category mistake. The potent feeling that decisions cause our actions is illusory (Dennett, 2016).

Here is a more specific example. When a person steps on a sharp object, the act causes activity in mechanical nociceptors that causes activity in afferent neurons, that causes activity in efferent neurons, that causes the action of screaming. This sequence of neural transactions is analogous to Dennett’s “object.” The particular sequence and pattern of neural activities is analogous to the spatial relations among parts of the object. The neural transactions also cause the mental phenomenon of pain, which is a description, and is analogous to the center of gravity. Even though it is tempting to think that the pain caused the scream, it is actually that the scream and the pain were both effects of the neural transactions. The scream and the pain are correlated effects, not causally linked. Now consider what happens if the sensors at the site of harm were anesthetized. This blocks the neural activity and changes both the behavior and the mental phenomenon, analogous to changing both the spatial relations among object parts and the center of gravity of the object. The person does not scream and also does not feel pain. Again, it is tempting to conclude that the absence of the scream is because of the absence of pain, but actually the absence of both effects is due to blocking the neural activity.

With the center of gravity example, that the reverse premise is false is relatively obvious. It may be helpful to use an example where the lure to mistakenly accept the reverse premise as true is more tempting. An example that illustrates this can be adapted from Gilbert Ryle’s “The concept of mind” (Ryle, 1949). Imagine a group of students at a university has been encamped in protest for many weeks, when another group of students starts a counter protest that produces some complaints of violence. To protect the safety of the students, the university gets a squad of state police to quell the disturbance. In this example, it may seem reasonable to say that the university caused the police to act. For a physicalist, however, this would be a category mistake. The university is an abstract construct, a non-physical entity, a description of buildings and people. The university cannot cause the police officers (real people) to act. However, the president of the university (a real person) could get the police officers to act. Stating it this way does not change the effect, which is still that the police quell the disturbance for the university; however, it correctly specifies the sequence of physical transactions that produced the effect, without invoking non-physical entities as causal. The reason that this example tempts us to commit a category mistake is that our common-usage definitions routinely conflate non-physical descriptions, such as “the university,” with physical agents and/or objects such as “the president.” Unfortunately, this conflation also routinely happens with scientific definitions in cognitive neuroscience.

The pain example could be considered an embodied rather than a classic decision and may not be generalizable. Let’s go back to an example with more deliberation, ordering at a restaurant. The “highest-level” cognition that would influence the kinds of decisions addressed in this paper are likely beliefs or schemas. For instance, to even know to pick up and look at the menu, there needs to be a schema based on previous experience ordering in restaurants or witnessing others doing it. Even if you have never seen a particular menu before, it is likely that you will look near the top of it for the appetizers, because that is where they were on previous menus. But, did the belief that appetizers are at the top of menus cause you to look there? Schemas, beliefs, rules, templates, knowledge, and memories are not physical. Just like it was the president and not the university that caused the police to act, it is the physical neural changes based on experience (learning), not the schema, that caused you to pick up the menu and look at the top of it for the appetizers. A schema is an excellent shorthand description of this learned behavior, but it cannot be the cause of behavior.

A feature of the neural mechanisms in these examples is that, by involving only physical transactions, they involve only afferent and efferent pathways, they involve only sensing and acting. They don’t involve pathways or brain regions for “thinking” or “deciding.” Thus, the sense-think-act model, including its assumptions of discrete processing stages, linear causality, volition, and internal representation is incompatible with physical reductionism. Sandwiching thinking between sensing and acting is a category mistake (Hurley, 2001, 2008). The sense-think-act model posits a false causal influence of thinking and decisions on behavior. From a physicalist view, mental phenomena like decisions must only be effects of neural mechanisms, of activity in afferent and efferent pathways (Anderson, 2011; Buzsáki & Tingley, 2023; Vanderwolf, 1998). It is misleading to theorize that mental phenomena such as schemas, attention, memory, executive function, and decisions are “mechanisms” (Hommel, 2020; Pessoa et al., 2021).

5) New directions for decision neuroscience

As mentioned earlier, no part of the argument above is new. Behaviorists, ecological psychologists, and cyberneticists all argued against some of the four assumptions and deprioritized the causal role of mental phenomena (Bingham, 1988; Gibson, 1966; Guerin, 2024; Powers, 1973a; Skinner, 1985; Turvey & Carello, 1986; Warren, 2006; Wiener, 1948). The strongest and most numerous arguments were made throughout the 1990s and involved replacement of computationalism with a combination of dynamical systems theory and embodied cognition. Dynamic systems theory had been around since the late 1800s, but was not applied to behavior until Walter Freeman used it to model EEG signals from the olfactory bulb (Freeman, 1979). About a decade later, Skarda and Freeman proposed an early version of the dynamic embodied view (Skarda, 1986; Skarda & Freeman, 1987). At the same time, autonomous roboticists like Rodney Brooks and Valentino Braitenberg were demonstrating that dynamical embodied robots produced unexpectedly complex behavior in naturalistic environments (Braitenberg, 1986; Brooks, 1986; Malcolm et al., 1989). Another decade later, Ester Thelen and Linda Smith proposed their dynamic systems theory of development (Spencer et al., 2012; Thelen & Smith, 1994). Similar to the autonomous robot research, their focus was on behaviors in naturalistic environments; they examined the development of behaviors like crawling and walking in children. The idea that dynamical systems and embodiment would replace computationalism was burgeoning (Beer, 1995; Cisek, 1999; Diedrich & Warren, 1995; Hendriks-Jansen, 1996; Mataric & Brooks, 1990; Pfeifer & Verschure, 1992). Why this idea was not more broadly accepted in neuroscience is something of a mystery.

To some, the argument above will be reminiscent of one of the arguments of behaviorism, an argument to cease studying mental phenomena in favor of studying behavior. But, that is not the argument being posed. The nervous system produces both behavior and mental phenomena and, as such, neuroscientists are compelled to explain both. Therefore, the argument is not to eliminate mental phenomena from the neuroscientist’s purview. Instead, the argument is that mental phenomena are being misrepresented in cognitive neuroscience theory and this is leading to a field-wide problem. Cognitive neuroscience is seen as a main contributor to the replication crisis in psychology and neuroscience and is being called out for a lack of reliability and a lack of scientific progress (Huber et al., 2019; Pereira, 2017; Shimamura, 2010; Stelzer et al., 2014). The basis for the crisis could be statistical, as some have suggested, but is more likely a combination of methodological and theoretical problems. The argument, therefore, is that part of the remedy to the crisis is to accurately represent mental/psychological phenomena, behaviors/actions, and neural mechanisms in decision neuroscience theories (or cognitive neuroscience more broadly).

A critical piece of the argument is that mental phenomena do not cause behavior, that decisions do not cause actions. However, the four assumptions combined with standard highly-constrained, linearly-causal test environments have led to conflation of the terms decision, choice, and action. At the very least, decisions and actions should be studied as separate phenomena, decisions as mental phenomena and actions as physical phenomena. This would surely lead to the development of distinct methodological approaches for studying decisions versus studying actions that would likely result in progress in understanding the separate phenomena, their relations, and their connection to underlying neural mechanisms. For instance, rather than studying decisions using simplistic actions like button presses, it seems more could be learned about decisions by using variations of techniques like think-aloud (Ericsson & Simon, 1980; Fonteyn et al., 1993; Güss, 2018). Admittedly, speaking and pressing buttons are both actions, which is the only way to access mental phenomena, but the unconstrained nature of the think-aloud technique should provide a much more detailed account of a private experience like a decision than, for example, a two-alternative forced-choice (2AFC) button press. Therefore, use of think-aloud seems much more suited to studying decisions and understanding how deliberation, reasoning, and thinking contribute to a subject’s overall subjective experience (Dennett, 2003).

On the other hand, tasks like 2AFC do seem better suited than think aloud for studying actions/choices. As already described above, however, a major problem with too much reliance on linearly-causal procedures like 2AFC is the reification of the sense-think-act model and its assumptions of linear causality and discrete processing stages. Data from tasks like 2AFC -- where actions are always made temporally-contingent on stimulus presentation -- will appear to have been produced by an underlying neural system that is linearly-causal and has discrete processing stages, even if it does not. As covered earlier, a tenet of ecological psychology is that acting-to-sense is just as important for behavior as sensing-to-act (Bingham, 1988; Gibson, 1966; Turvey & Carello, 1986). From this perspective, linearly-causal tasks like 2AFC are, at best, capturing only half of what is important. Using test environments that engage and measure active sensing allows for analysis of the full range of brain, body, and environment interactions that are part of an organism’s behavioral repertoire (Diedrich & Warren, 1995; Gordon et al., 2021; Thelen & Smith, 1994). This will require developing tasks that are dynamic and time-sensitive (Meyer et al., 2019; Murty et al., 2023) and that are interactive and invoke a sense of agency (Levitas & James, 2024; Ni et al., 2025). The data sets produced by these tasks will have many variables that are collected through time and it is highly likely the variables will be correlated. Thus, progress will also require developing analysis methods that can make use of rich data sets, and an acceptance of the correlated (some would call it confounded) character of naturalistic environments (Levitas & James, 2024; Pessoa et al., 2021).

In addition to updating experimental environments to effectively test active sensing, a major shift is needed in theorizing about sensory and motor systems. It has already been said here and elsewhere that the common theoretical conflation of neural mechanisms with mental phenomena is holding back progress (Anderson, 2011; Hommel, 2020; Pessoa et al., 2021). What is needed is a different approach to theorizing about neural mechanisms. The arguments above converge on the idea that sensory and motor processes influence each other (are simultaneously causal) and not influenced by mental phenomena like thinking and deciding. Additionally, sensory and motor processes are seen as integrated, they are not discrete or modular. Given that this position is radically different from current theories in decision neuroscience, what is available to scaffold this potential new direction?

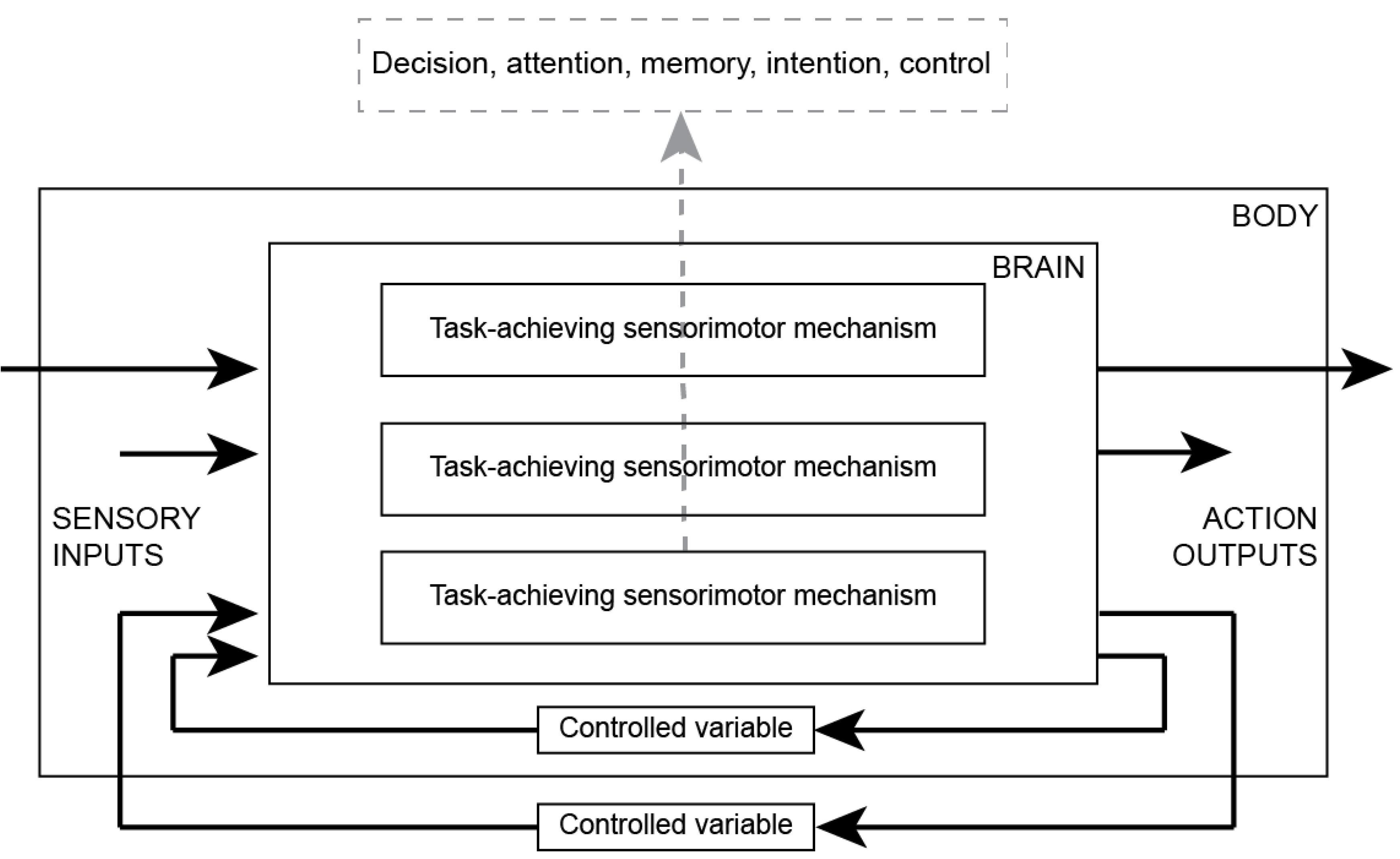

A specific subfield of autonomous robotics research may provide a blueprint. Researchers have different labels for the particular approach, including subsumption architecture, distributed adaptive control, or adaptive behavior, but they all converge on the same set of factors that differentiate it from the “rationalist” approach to robotics (Beer, 1995; Beer, 2003; Brooks, 1986; Hendriks-Jansen, 1996; Mataric & Brooks, 1990; Pfeifer & Verschure, 1992). Instead of using constrained environments, the robots need to function in natural environments and therefore must be flexible and robust to unanticipated environmental changes. Instead of a control system engineered to perform a specific complex behavior, a formally-specified procedure, or specific acts on specific objects, the approach combines multiple, much simpler control systems or modules. None of the modules alone produce a complex procedure, it is only through their interactions with each other and with the naturalistic environment that recognizable, complex, and even unanticipated behaviors are produced. Each module is envisioned as a

sensorimotor or sense-act circuit—there are no “thinking” components. Sensorimotor circuits form negative feedback loops with the environment, allowing for simultaneous acting-to-sense and sensing-to-act. Clearly, these designs are all embodied dynamical systems, inspired in one way or another by ecological psychology. For the purpose of neuroscientists, the embodied dynamic approach in robots may provide an analogy for generating mechanistic explanations for how complex behavior emerges from sequences of physical transactions between brain, body, and environment in living organisms (

Figure 3).

Neuroscience parallels robotics in having two approaches to theorizing. In robotics, this manifests in how the robots are designed and, in neuroscience, this manifests as theories about neural mechanisms. A well-studied example in robotics is wall-following behavior. A typical rationalist approach would be to design the robot with an internal representation of the environment (a map) occupied by discrete objects (including walls) and imbue it with formal rules to navigate among the objects. If wall-following behavior was desirable to the designer, rules would be added to ensure wall-following behavior occurred. Thus, the rationalistic approach is to design internal mechanisms that explicitly mimic some targeted complex (mental) phenomenon. This is different from the embodied dynamic approach described above, which is to design mechanisms for simple actions that do not resemble the target phenomenon, but nonetheless are able to produce it given some specific environmental conditions. In one particular example (Pfeifer & Verschure, 1992), the robot is designed with a set of simple sensorimotor circuits (they call them “reflexes”), for example “if a target sensor detects something, turn toward it” and “if a collision sensor detects something, reverse and turn away from it.”

1 In a standard environment, the embodied robot navigates successfully, but unlike the rationalistic robot, it does not show wall-following behavior. However, if the environment is structured such that targets are usually found in small alcoves along walls—i.e., using wall following makes it easier to find the targets -- the wall-following behavior emerges from specific combinations of the simpler reflexes. The rationalistic robot can

only use wall-following, even when not necessary, and cannot develop other complex forms of behavior to find targets. For the embodied robot, wall-following behavior

emerges when the environment affords it, but other complex behavioral patterns can also emerge when the environment affords them.

An analogy in neuroscience can be made with respect to mental phenomena and neural mechanisms. The classic Stroop effect can be used as an example. Anyone who has tried the Stroop task has experienced two mental phenomena during incongruent trials. One is the feeling of cognitive interference between the two stimulus dimensions. The second is the feeling that the interfering dimension was successfully inhibited on successful trials. Typical of cognitive neuroscience theorizing, the neural mechanism ascribed to brain regions that activate more for incongruent trials (like anterior cingulate cortex) is inhibition or cognitive control (e.g., Leung et al., 2000). Assigning “cognitive control” as the neural mechanism of the anterior cingulate is similar to explicitly programing wall-following behavior into the rationalistic robot and raises similar concerns.

On top of that, assigning cognitive control as a “neural mechanism” is an example of the misrepresentation problem in cognitive neuroscience theorizing. Cognitive control is a mental phenomenon, not a neural mechanism, but assigning it as a neural mechanism also assigns it a causal role in determining behavior. Under a dualist stance, cognitive control can cause behavior, but its definition then becomes precariously close to that of an internal observer or “little man,” which is usually unpalatable to physicalists (Skinner, 1985). What is needed to align with the physicalist stance is to hypothesize a neural mechanism that can cause both the performance changes and feelings of inhibition and cognitive control that are elicited by the Stroop environment. Admittedly, this is a simplified description of the Stroop effect and cognitive control compared to current theories (e.g., Banich, 2019), however, the approach to theorizing is not affected by this simplification.

The comparison of the two approaches to theorizing in robotics and in neuroscience just described has been described more formally as the difference between the “analytic” versus “synthetic” approach in psychology and neuroscience (Hommel & Colzato, 2015). The goal of both approaches is to explain mental and behavioral phenomena. The analytic approach starts with a phenomenon (usually mental) and theorizes “downward” to the physical mechanisms. It is typically assumed that a phenomenon is produced by an underlying neural “system” and that system’s function is typically identified as the phenomenon itself. The memory example with patient H.M. and the cognitive control example with the Stroop effect both follow this approach. Decision neuroscience also largely follows this approach, identifying neural mechanisms with abstract, subjective qualities like value, utility, uncertainty, and risk (Dennison et al., 2022; Smith & Huettel, 2010). It has been observed that, historically, scientific fields use the analytic approach in their early stages, making little progress until they move beyond theorizing that the underlying mechanisms must resemble the phenomena they are supposed to explain (Hendriks-Jansen, 1996).

The synthetic approach starts with the mechanisms and works “upward” to the phenomena. The challenge is to identify fundamental mechanisms of an organism that, when exposed to a specific environment, will produce the phenomenon. One way to conceive of the mechanisms is that they are similar to the “reflexes” in the embodied robots. For humans, uncovering good candidates may involve examining the types of reflexive actions that are highlighted by “embodied decisions.” One reason to start here is that reflexive movements may represent sensorimotor “primitives” across both embodied and classic decisions, regardless of the mental phenomena that accompany them. In many ways, this exercise resembles the work done in behavior ecology and ethology, which is regarded by some as a more appropriate way to identify the phenomena that should be the targets of investigation in cognitive neuroscience (Cisek, 1999; Pessoa et al., 2021).

Theories and models from cybernetics and from embodied dynamical systems have in common that they do not rely on the four assumptions. Although both involve feedback from the environment, one difference is the prevalence in cybernetics of control theory principles that focus on negative feedback and reference signals as fundamental to the architecture (Rosenblueth et al., 1943; Wiener, 1948). In perceptual control theory, reference signals are the physical mechanism underlying goals, with the organism producing actions to bring sensory signals in line with the reference signal (Marken & Powers, 1989; Powers, 1973a). Negative feedback loops are the basis of many physiological systems and it would not be surprising if they were also implemented in the nervous system for controlling behavior. Therefore, it is worth considering that one way (and potentially a primary way) that sensorimotor modules or primitives may interact with each other is through reference input signals, rather than only sensory input signals.

Perceptual control theory also introduced the idea of the “controlled variable,” that behavior can be best understood from a control theory perspective and that organisms are continuously attempting to “control” specific variables in the environment. According to control theory, the key attribute that distinguishes living things from non-living things is that they are homeostatic (or more aptly rheostatic). Whereas the behaviorists conceived of organisms as reactive to their environment, the cyberneticists viewed organisms as controlling their environment based on internal purposes or goals (Marken & Powers, 1989; Rosenblueth et al., 1943). Note that despite the use of the terms purpose and goal, their view is still consistent with physicalist principles. Reference signals are physical transactions that cause changes in efferent pathways and likely also cause the mental phenomenon of a goal. The goal cannot cause actions that control environmental variables, but the reference signal can. Based on this control theory premise, an important component for understanding behavior is understanding the environmental variables that an organism is attempting to control. For research, experiments can be designed with this premise in mind, and researchers can more purposefully direct subjects to control specific variables in the experimental environment. Mapping brain activation with controlled variables may have a greater chance of isolating negative feedback loops between the environment and specific sensorimotor reflexes.