Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Dynamic Modeling

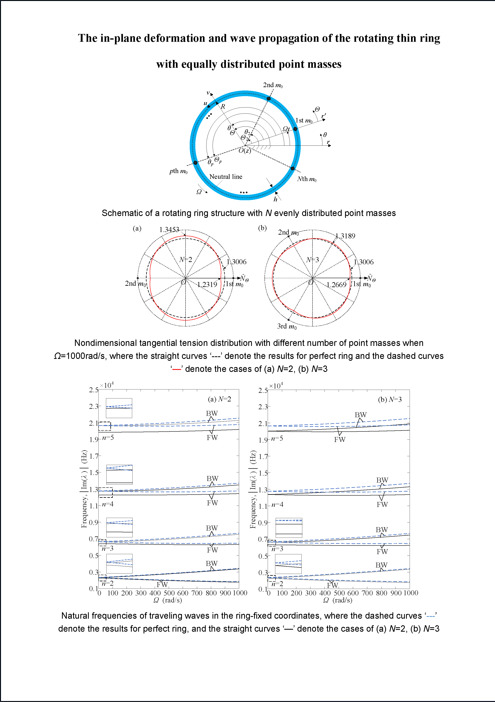

2.1. Model Description

2.2. Equations of Motion

3. Model Analysis

3.1. Solution Strategy

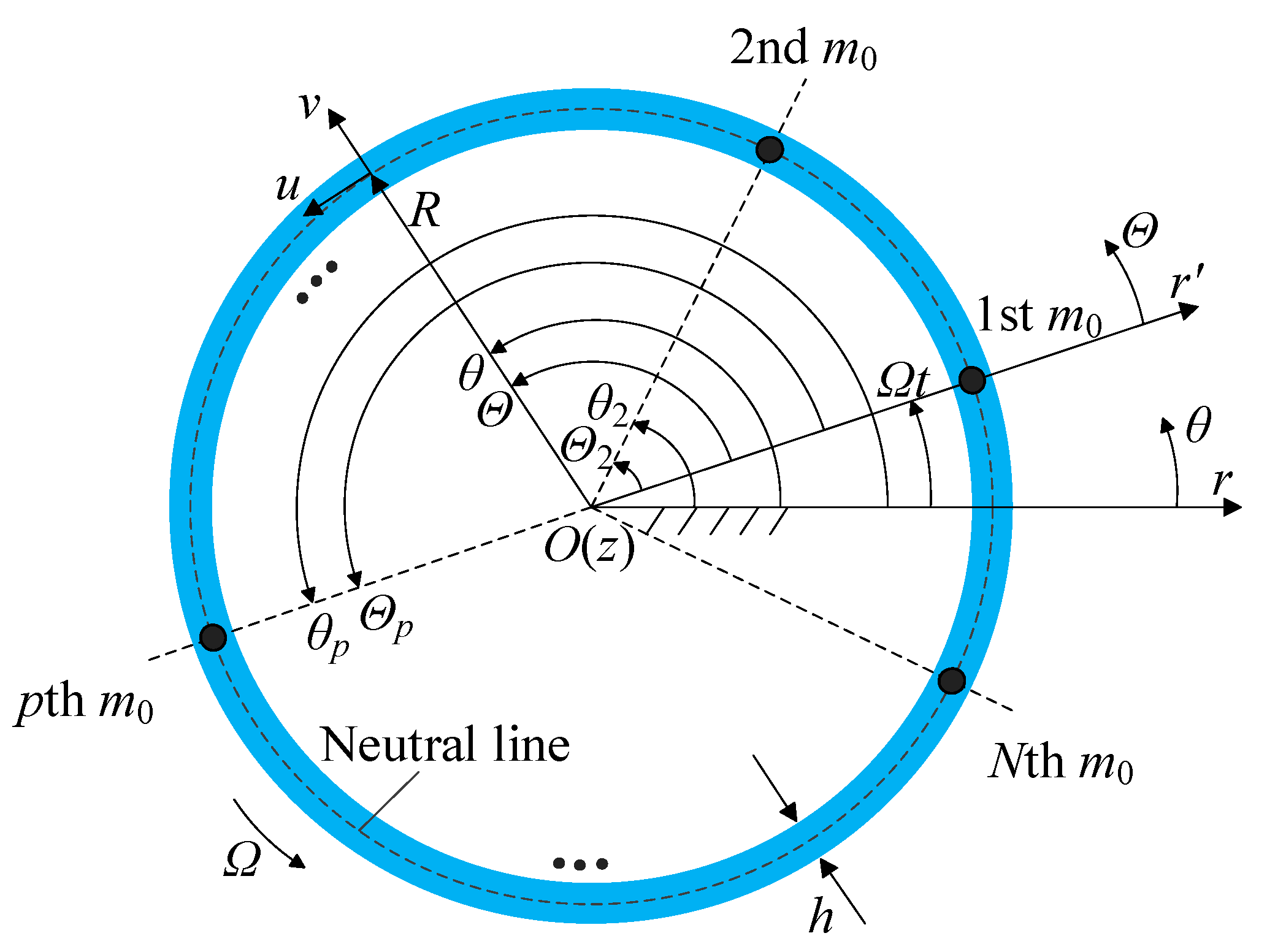

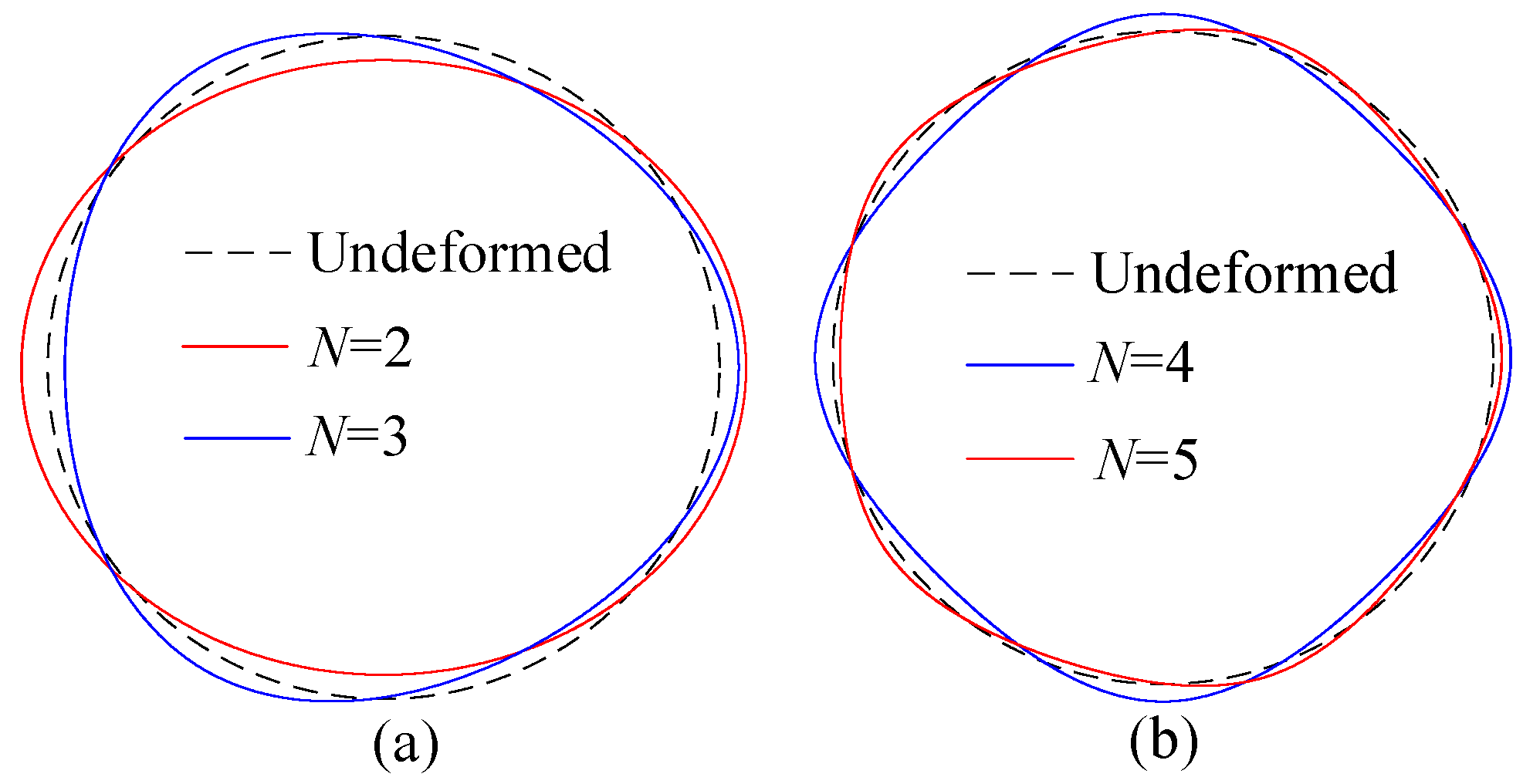

3.2. Steady Elastic Deformation

3.3. Free Response

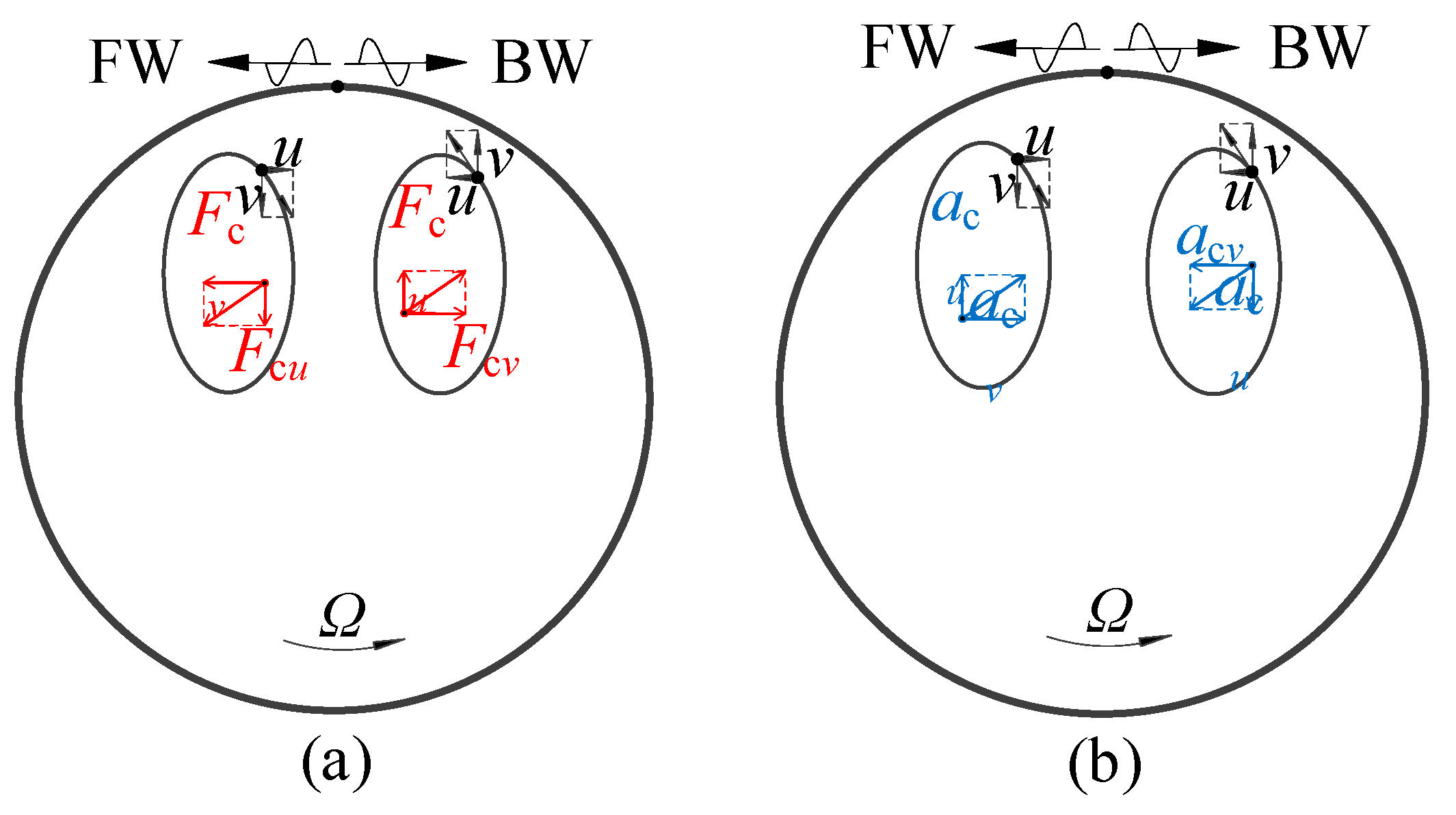

3.4. Qualitative Explanation of the Coriolis Effect

4. Numerical Results

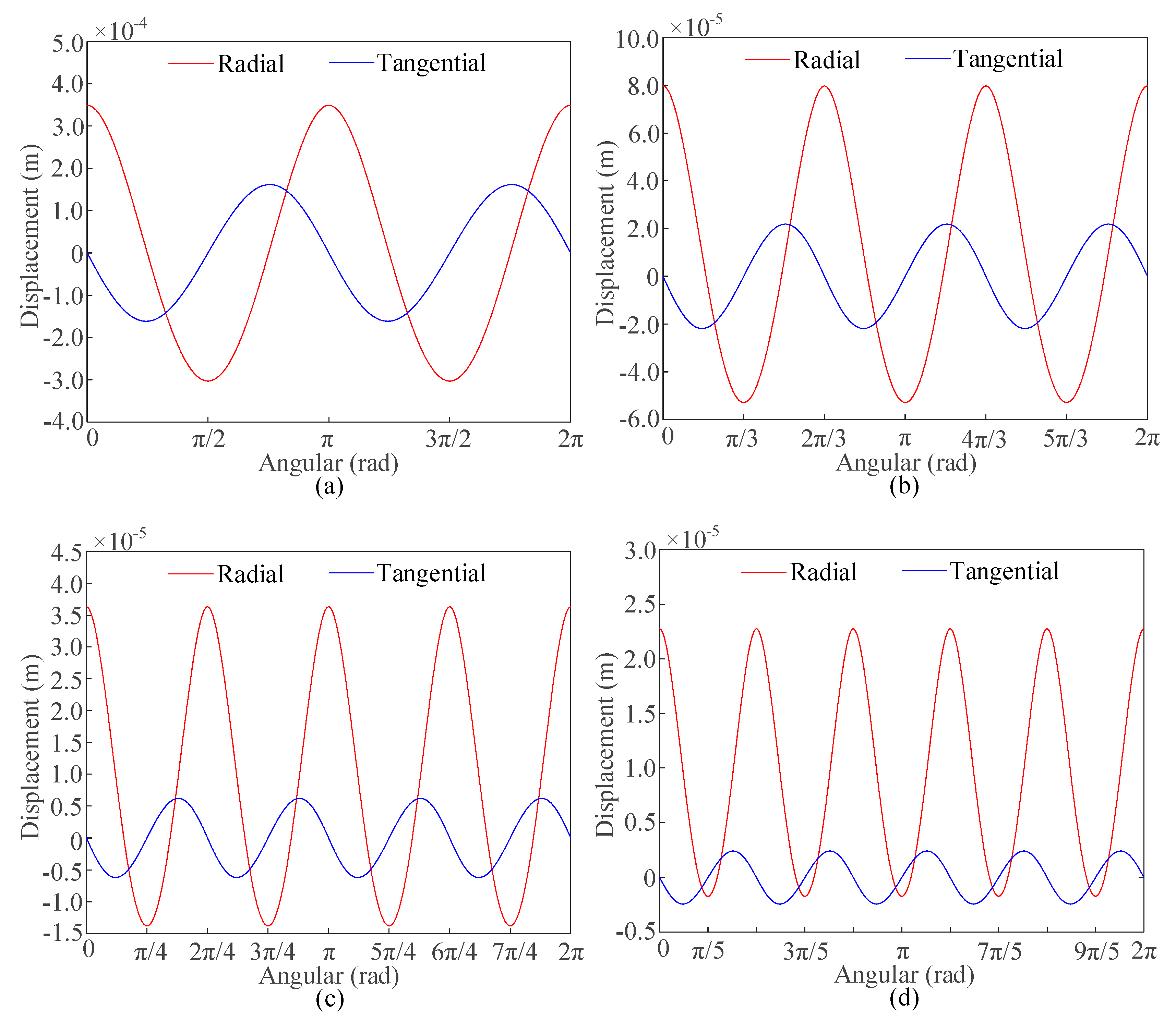

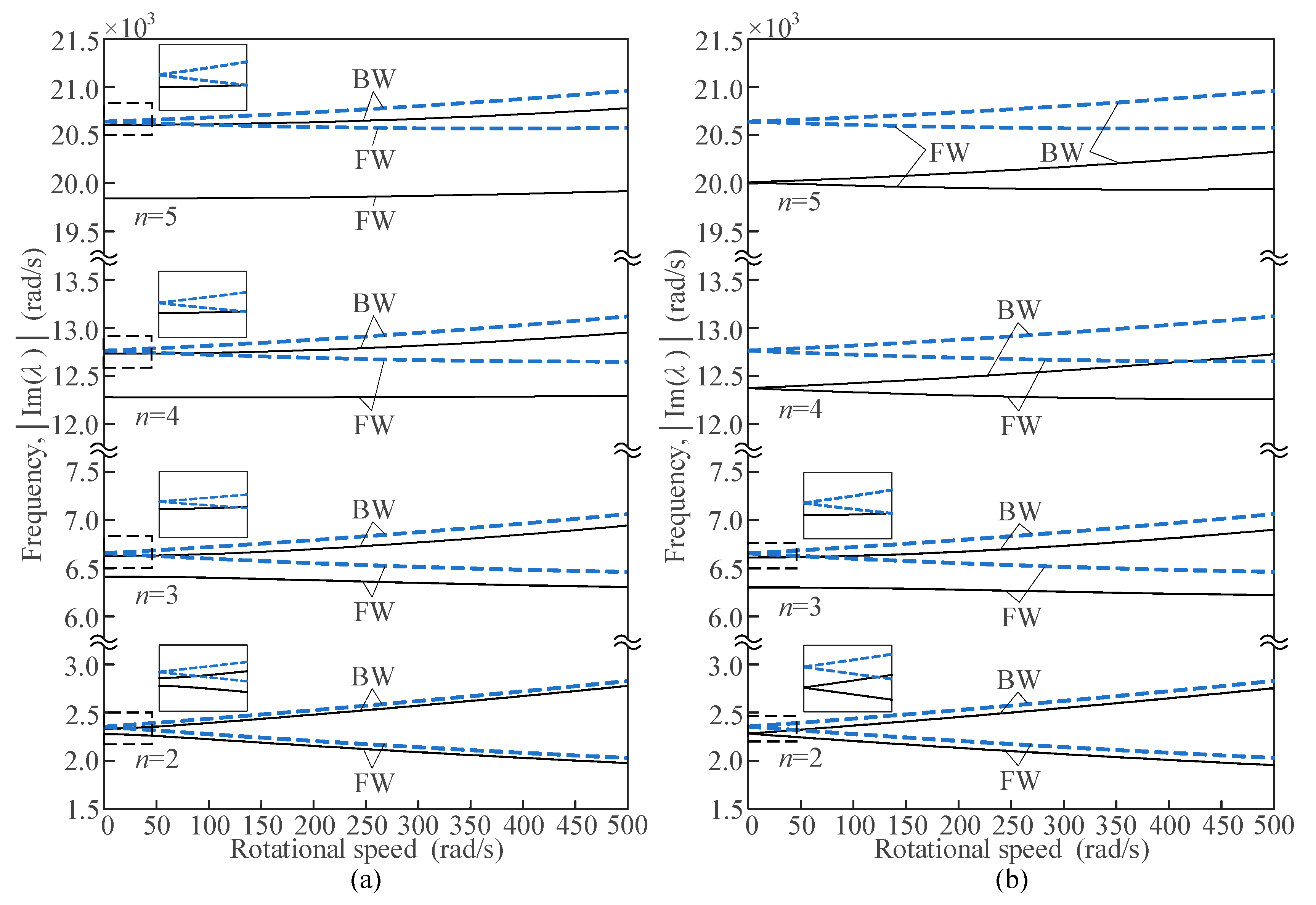

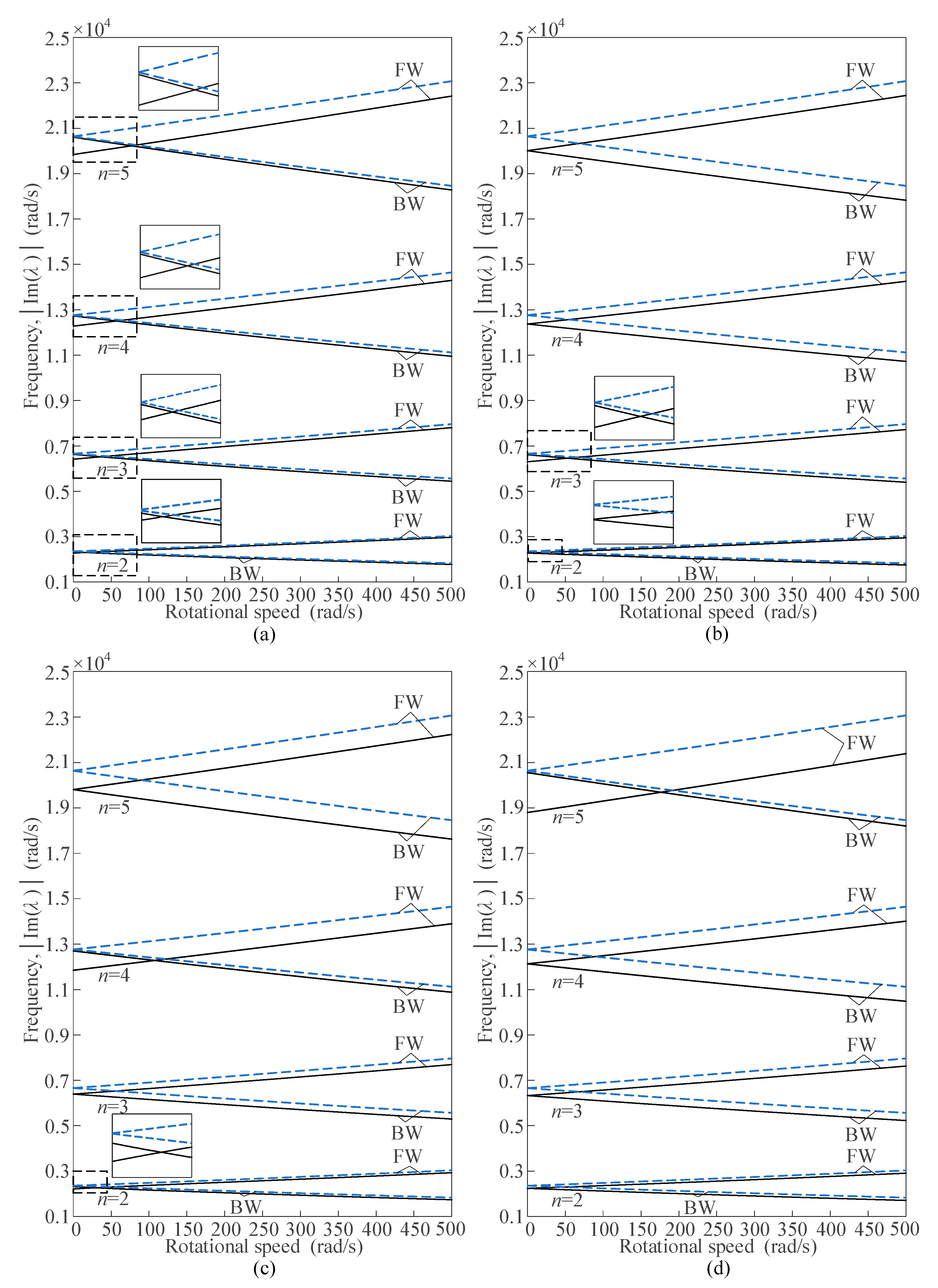

4.1. Nature Frequencies and the Validation

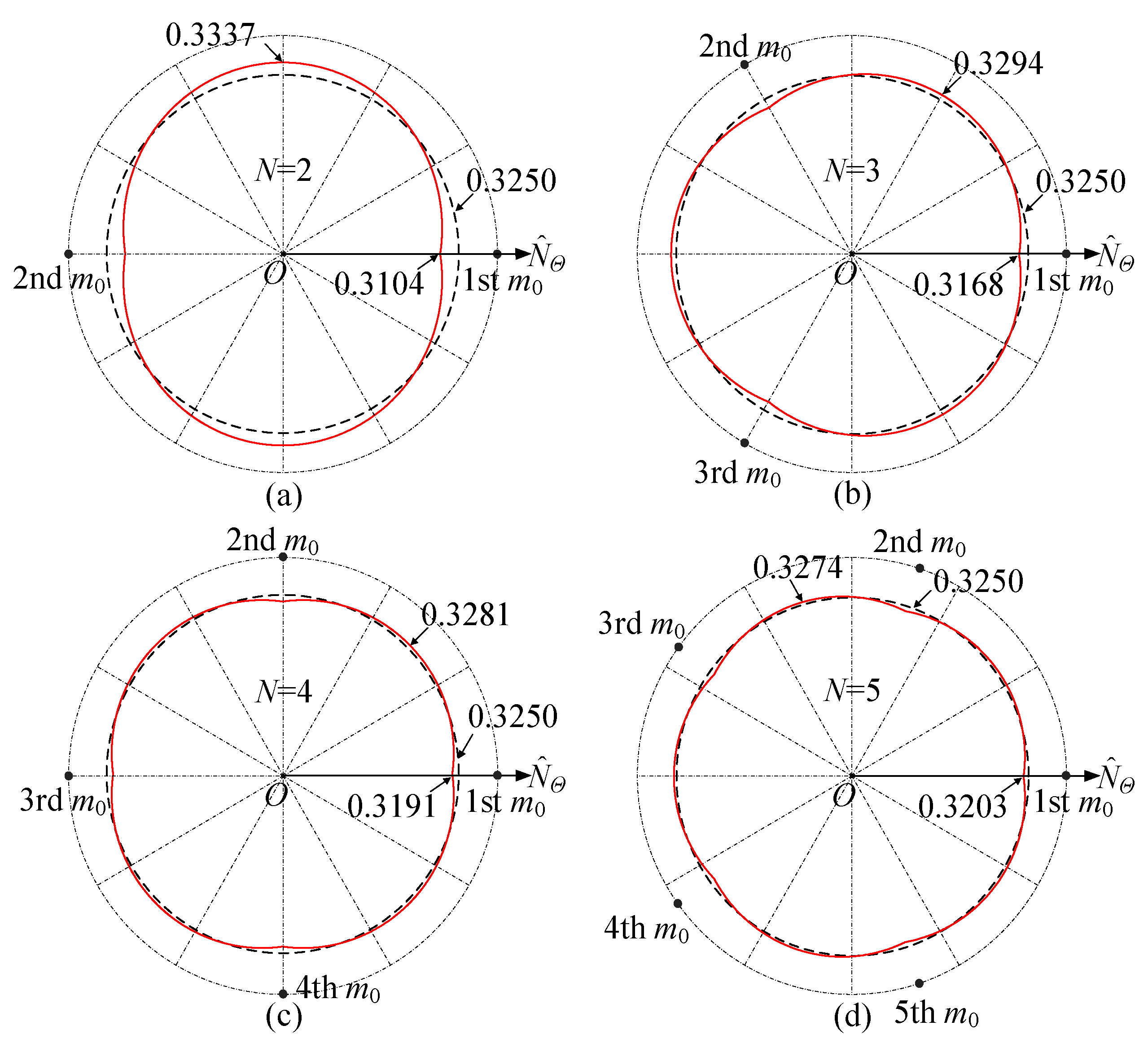

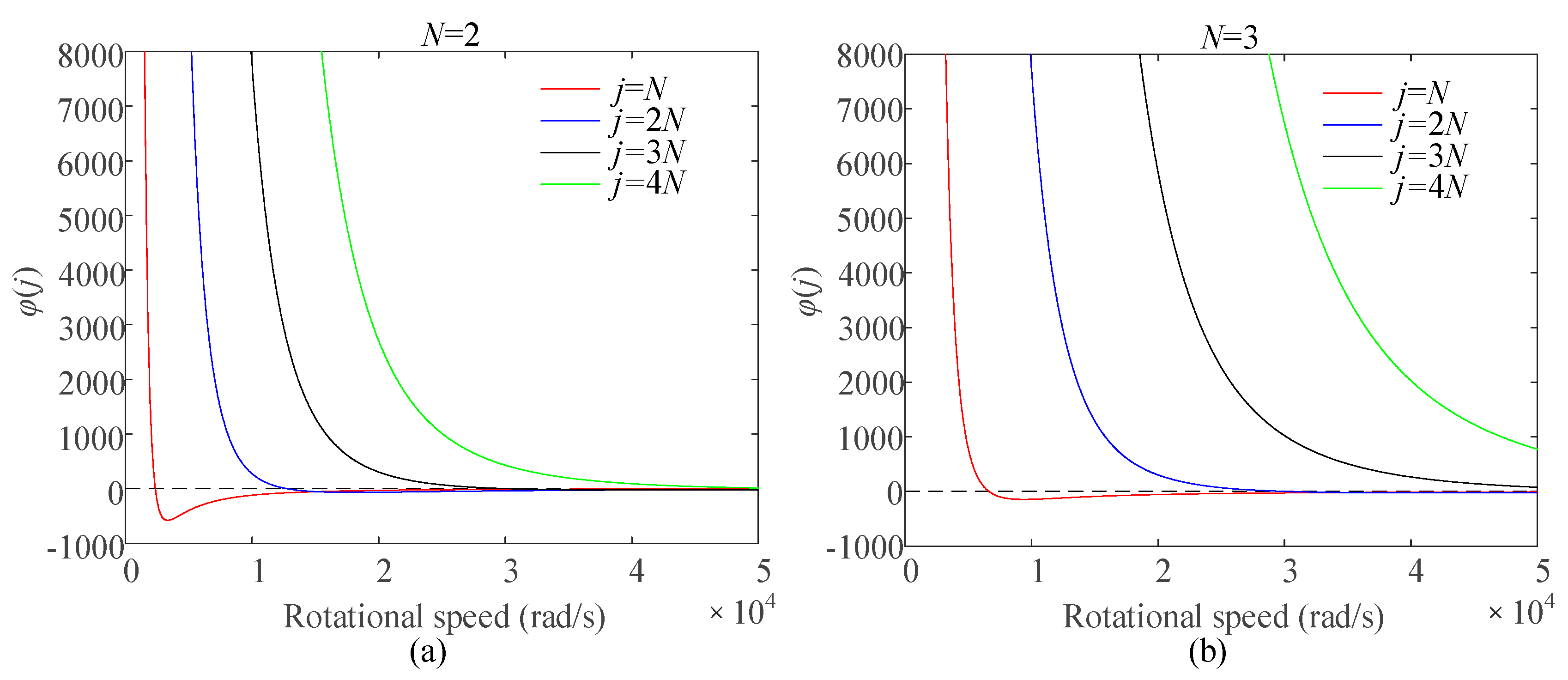

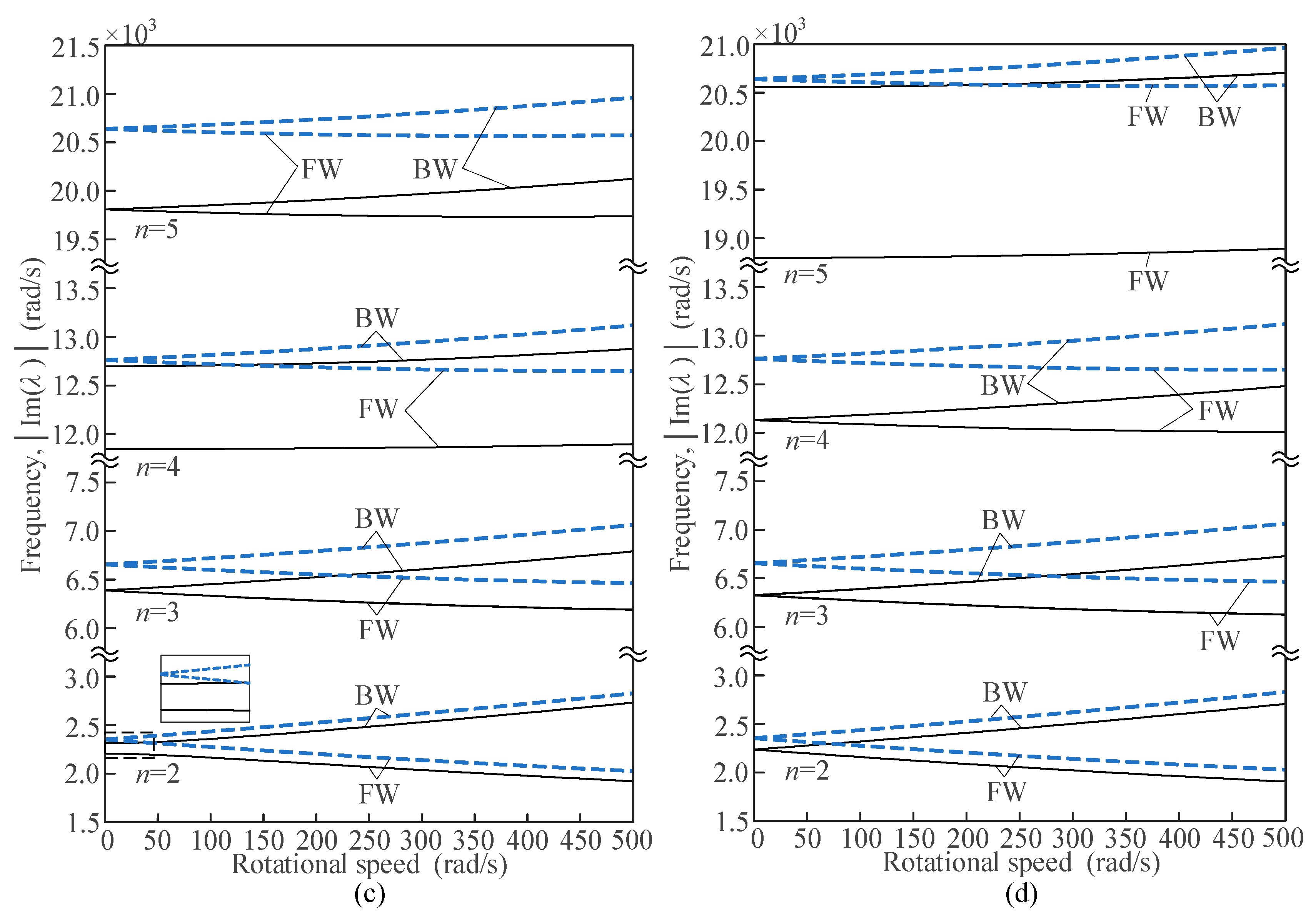

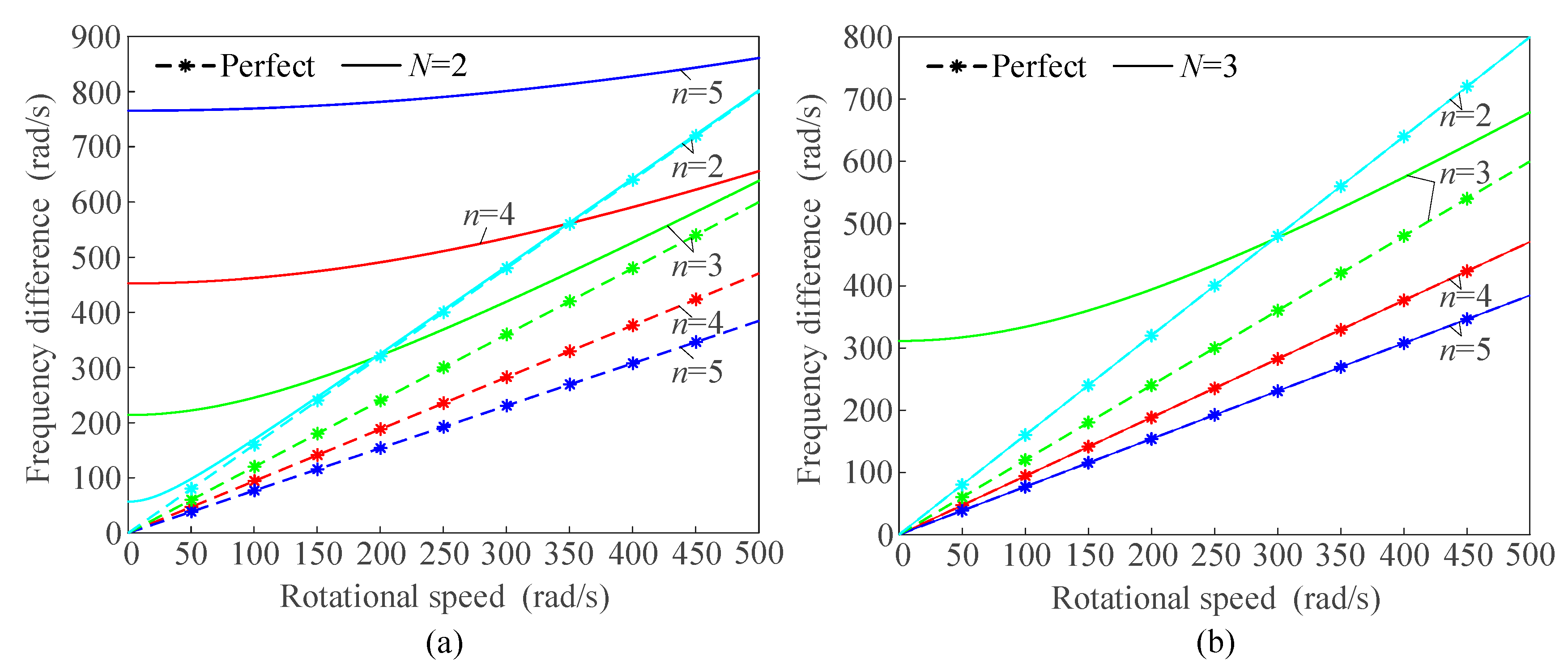

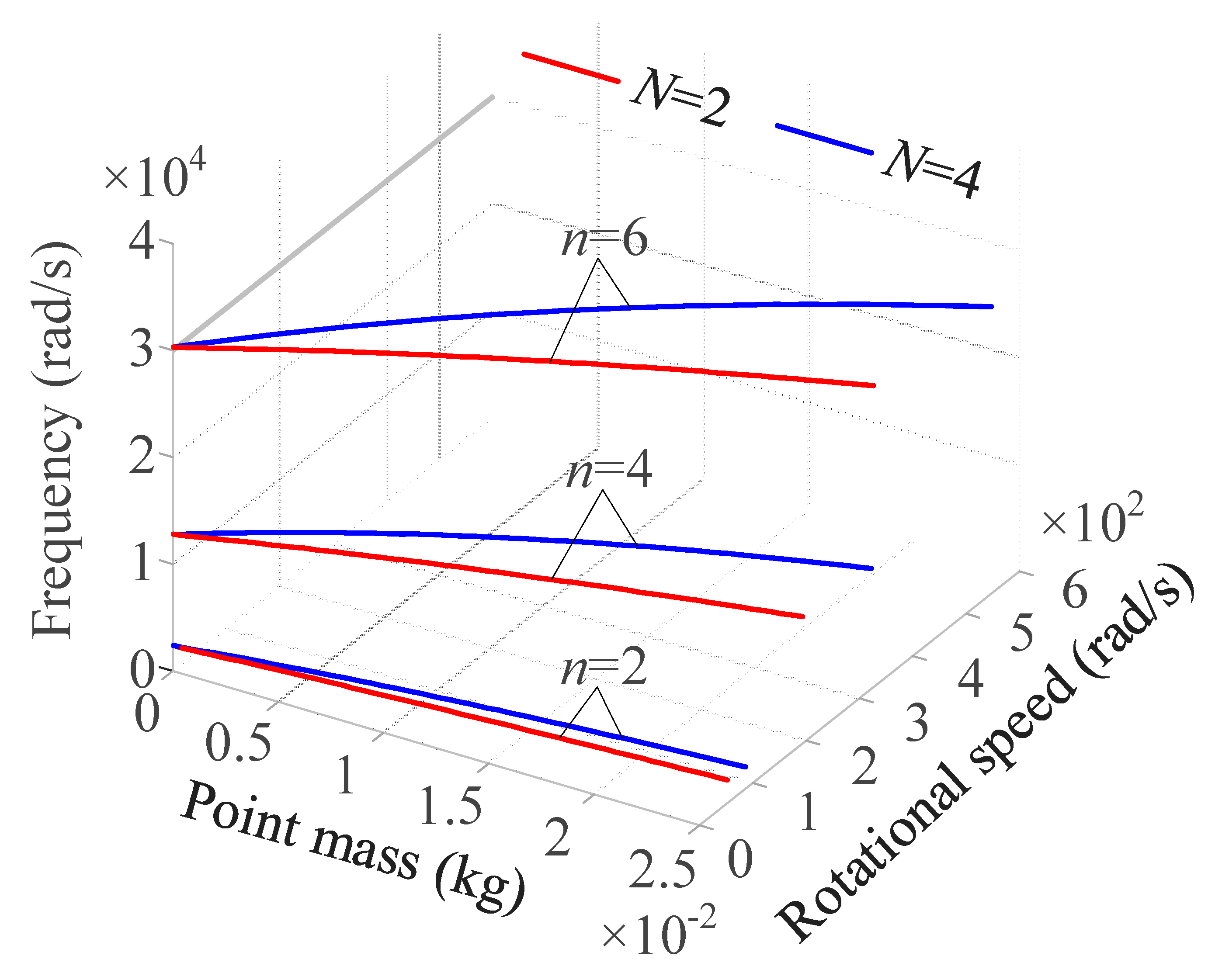

4.2. Crosspoints of the Natural Frequencies of FW and BW

5. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, R.; Wang, X.; Yan, K.; Chen, Z.; Ma, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, A.; Lu, Q. Interactive Errors Analysis and Scale Factor Nonlinearity Reduction Methods for Lissajous Frequency Modulated MEMS Gyroscope. Sensors 2023, 23, 9701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, J.R.; Xin, Z.; Sheng, Y.; Xue, Z.W.; Ding, B.X. Frequency-Modulated MEMS Gyroscopes: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 26426–26446. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Parker, R.G. Modal Properties of Planetary Gears With an Elastic Continuum Ring Gear. J. Appl. Mech. 2008, 75, 031014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z. Elimination of Magnetically Induced Vibration Instability of Ring-Shaped Stator of PM Motors by Mirror-Symmetric Magnets. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2019, 8, 695–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, S.W.; Lee, S.; Najafi, K. Vibration sensitivity analysis of MEMS vibratory ring gyroscopes. Sensors Actuators A: Phys. 2011, 171, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Xiong, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, J. A ring-type multi-DOF ultrasonic motor with four feet driving consistently. Ultrasonics 2017, 76, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soedel, W. Vibrations of Shells and Plates; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2004; ISBN 9780429216275. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.; Chung, J. FREE NON-LINEAR VIBRATION OF A ROTATING THIN RING WITH THE IN-PLANE AND OUT-OF-PLANE MOTIONS. J. Sound Vib. 2002, 258, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Soedel, W. Effects of coriolis acceleration on the free and forced in-plane vibrations of rotating rings on elastic foundation. J. Sound Vib. 1987, 115, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xiu, J.; Gu, J.; Xu, J.; Liu, J.; Shen, Z. Prediction and suppression of inconsistent natural frequency and mode coupling of a cylindrical ultrasonic stator. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C: J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2010, 224, 1853–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Tang, L.; Cao, R. Free vibration analysis of planar rotating rings by wave propagation. J. Sound Vib. 2013, 332, 4979–4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, C.G.; Parker, R.G. Vibration of high-speed rotating rings coupled to space-fixed stiffnesses. J. Sound Vib. 2014, 333, 2631–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kang, S.-J. Splitting of quality factors for micro-ring with arbitrary point masses. J. Sound Vib. 2017, 395, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Liang, D.-D.; Qian, Y.-J. Nonlinear Performance of MEMS Vibratory Ring Gyroscope. Acta Mech. Solida Sin. 2020, 34, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Kou, J.; Hu, Y.-C. Vibration of a Rotating Micro-Ring under Electrical Field Based on Inextensible Approximation. Sensors 2018, 18, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asokanthan, S.F.; Cho, J. Dynamic stability of ring-based angular rate sensors. J. Sound Vib. 2006, 295, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Kou, J.G.; Hu, Y.C. Vibrations of Rotating Ring Under Electric Field. J. Chin. Soc. Mech. Eng. 2021, 42, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Polunin, P.M.; Shaw, S.W. Self-induced parametric amplification in ring resonating gyroscopes. Int. J. Non-linear Mech. 2017, 94, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, C.G.; Parker, R.G. Limitations of an inextensible model for the vibration of high-speed rotating elastic rings with attached space-fixed discrete stiffnesses. Eur. J. Mech. - A/Solids 2015, 54, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Dynamic instability of an eccentrically rotating ring-shaped structure. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C: J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2024, 238, 4944–4958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H. Thermoelastic dissipation of rotating imperfect micro-ring model. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2016, 119, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beli, D.; Silva, P.B.; Arruda, J.R.d.F. Vibration Analysis of Flexible Rotating Rings Using a Spectral Element Formulation. J. Vib. Acoust. 2015, 137, 041003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canchi, S.V.; Parker, R.G. Parametric Instability of a Rotating Circular Ring With Moving, Time-Varying Springs. J. Vib. Acoust. 2005, 128, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, S.; Liu, J. Analytical Prediction for Free Response of Rotationally Ring-Shaped Periodic Structures. J. Vib. Acoust. 2014, 136, 041016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnley, T.; Perrin, R.; Mohanan, V.; Banu, H. Vibrations of thin rings of rectangular cross-section. J. Sound Vib. 1989, 134, 455–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, T.; Tanaka, S. Fully Differential Single Resonator FM Gyroscope Using CW/CCW Mode Separator. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 2018, 27, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, T.; Tanaka, S. Fully Differential Single Resonator FM Gyroscope Using CW/CCW Mode Separator. J. Microelectromechanical Syst. 2018, 27, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, T.; Tanaka, S. FM/rate integrating MEMS gyroscope using independently controlled CW/CCW mode oscillations on a single resonator. 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Inertial Sensors and Systems (INERTIAL); pp. 1–4.

| Parameters | Values and units |

| Neutral circle radius | R=0.1 m |

| Axial length | b=0.01 m |

| Young’s modulus | E =2.0×1011 N/m2 |

| Density | ρ=7.8×103 kg/m3 |

| Thickness | h=6×10-3 m |

| Magnitude of mass imperfection | m0=2π×10-3 kg |

| Rotational speed | Ω=500 rad/s |

| Conditions | λRe | λIm | |

| 0 | |||

| 0 | |||

| Conditions | λRe | λIm | |

| 0 | |||

| 0 | |||

| Modes n | Ω (rad/s) | fFW (Hz) | fBW (Hz) | ||||

| FEM | Numerical | Diff. (%) | FEM | Numerical | Diff. (%) | ||

| 2 | 0 | 350.74 | 351.30 | 0.16 | 367.72 | 368.32 | 0.16 |

| 250 | 325.50 | 329.55 | 1.22 | 391.45 | 395.52 | 1.03 | |

| 500 | 291.56 | 306.28 | 4.81 | 421.81 | 434.91 | 3.01 | |

| 3 | 0 | 1012.70 | 1016.83 | 0.41 | 1012.70 | 1016.83 | 0.41 |

| 250 | 987.99 | 997.04 | 0.91 | 1035.80 | 1044.79 | 0.86 | |

| 500 | 966.23 | 985.33 | 1.94 | 1061.10 | 1080.82 | 1.82 | |

| 4 | 0 | 1868.30 | 1885.35 | 0.90 | 2004.70 | 2021.11 | 0.81 |

| 250 | 1865.50 | 1887.26 | 1.15 | 2006.50 | 2028.43 | 1.08 | |

| 500 | 1860.00 | 1893.47 | 1.77 | 2024.90 | 2049.76 | 1.21 | |

| 5 | 0 | 3121.80 | 3153.02 | 0.99 | 3121.80 | 3153.02 | 0.99 |

| 250 | 3104.00 | 3142.67 | 1.23 | 3135.00 | 3173.23 | 1.20 | |

| 500 | 3103.20 | 3142.04 | 1.23 | 3148.40 | 3203.31 | 1.71 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).