Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Sensory Analyses

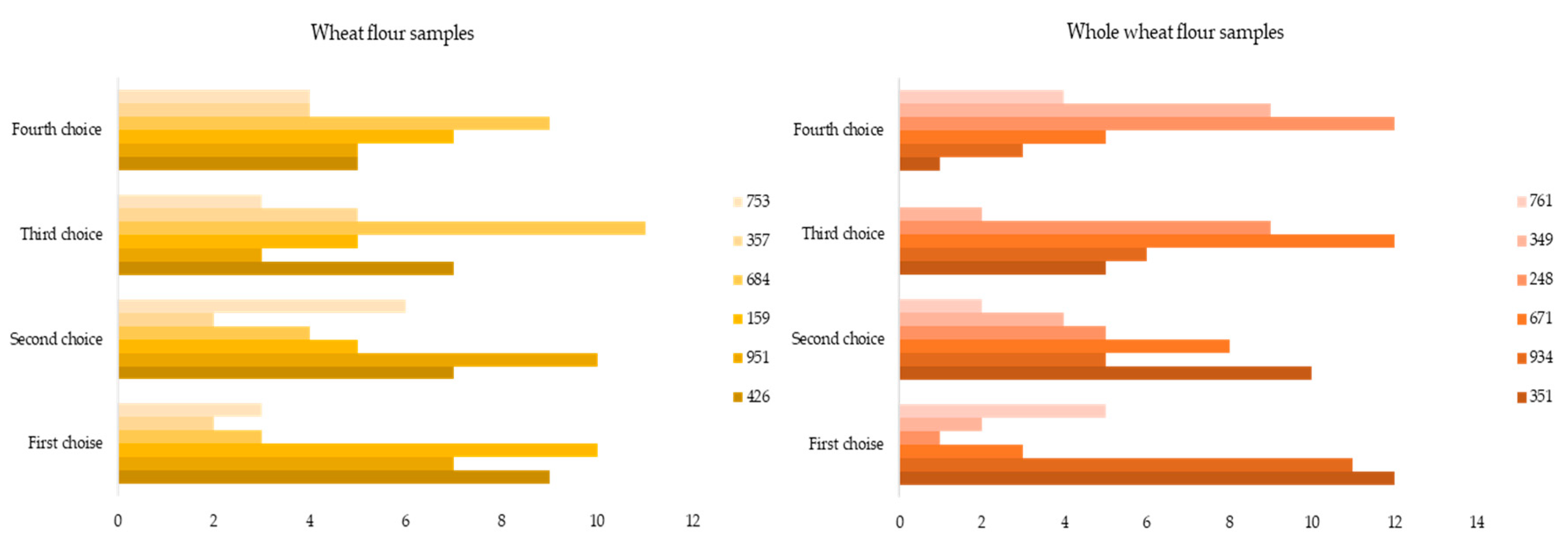

2.1.1. Preferential (Hedonic) Sensory Analysis

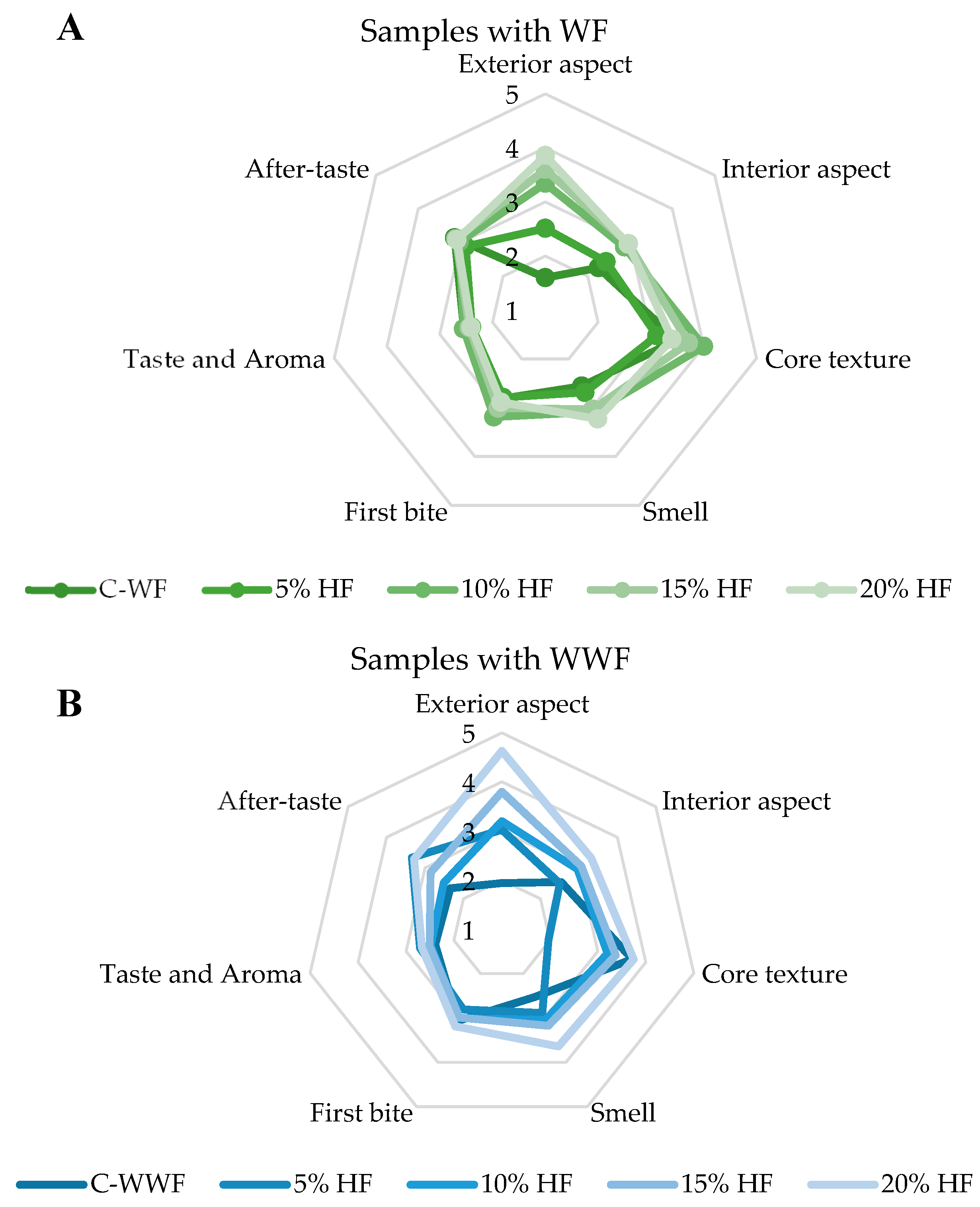

2.1.2. Descriptive Sensory Analysis

2.2. Physical Properties

2.2.1. Texture Measurements

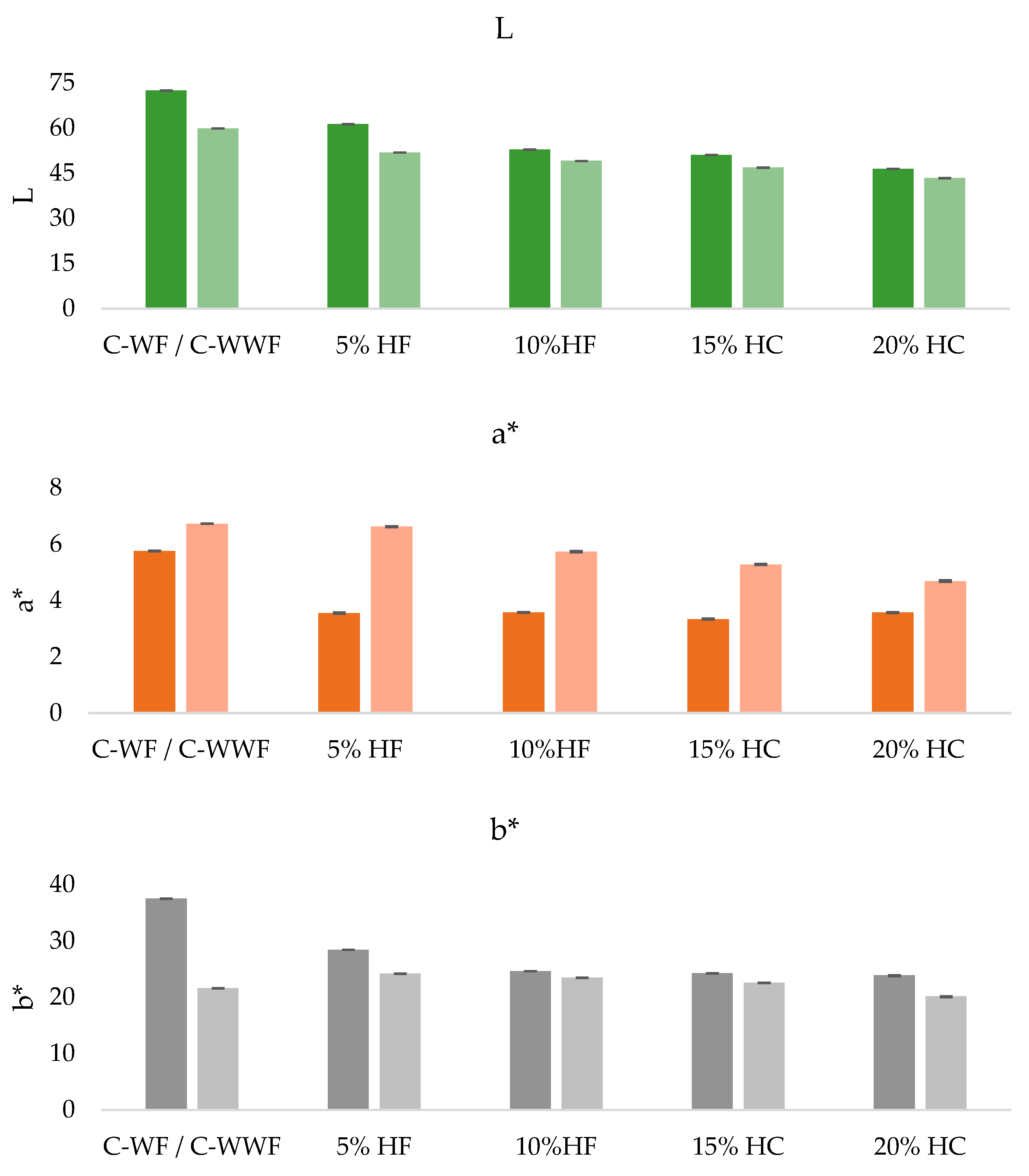

2.2.2. Color Measurements

2.3. Microbiology Analysis

2.4. Physicochemical Analyses

3. Materials and Methods

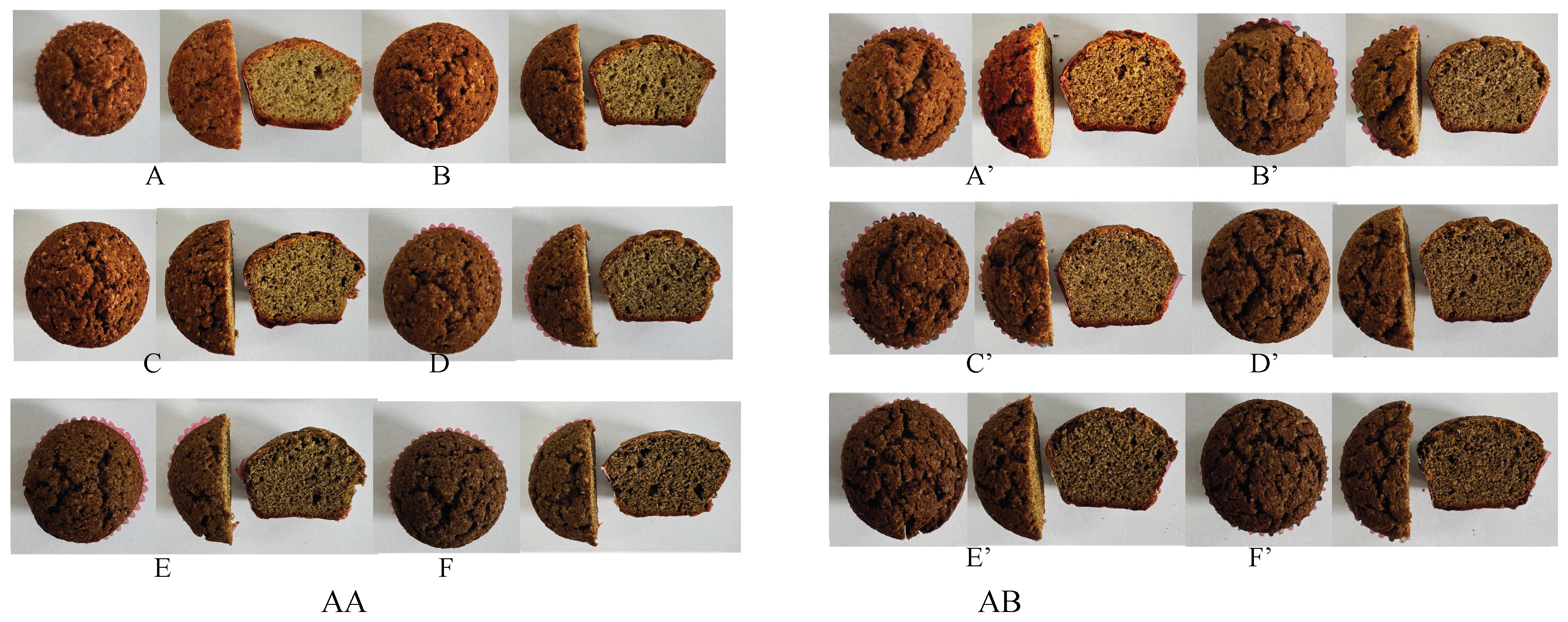

3.1. Preparation of Samples

3.2. Analyses performed.

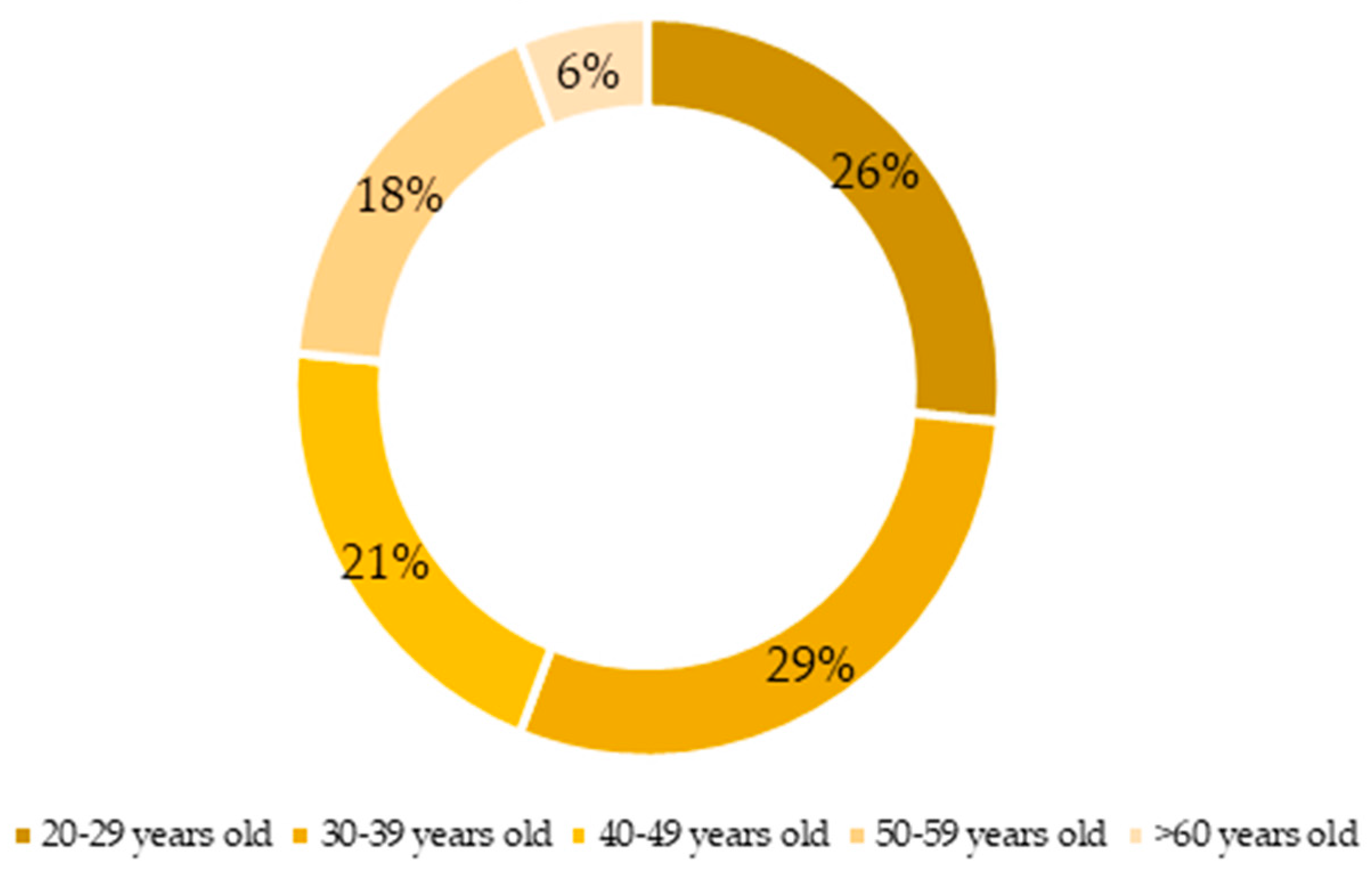

3.2.1. Preferential (Hedonic) Sensory Analysis

3.2.2. Descriptive Sensory Analysis

- Blind coding: Samples were labeled with randomized three-digit codes to eliminate bias.

- Randomized presentation: Samples were served in a random order to prevent order effects influencing judgments.

- Controlled environment: The evaluations took place in individual sensory booths under neutral lighting to avoid visual bias.

- Portion size: Uniform-sized muffin pieces were provided to ensure equal exposure to texture and flavor attributes.

- Palate cleansing: Consumers were instructed to rinse their mouths with water between samples to reset taste perception.

3.2.3. Texture Analysis

- Firmness (N): Maximum force required to compress the sample, indicating hardness.

- Cohesiveness: The ratio of the second compression peak to the first, reflecting the structural integrity of the muffin crumb.

- Elasticity (Springiness): The ability of the muffin to return to its original shape after compression.

- Gumminess (N): The product of firmness and cohesiveness, representing the energy required to chew the muffin [29].

3.2.4. Color Analysis

3.2.5. Microbiological Analysis

3.2.6. Physicochemical Analyses

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Crocq, M.-A. History of cannabis and the endocannabinoid system. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 22, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvijic, A.; Bauer, B. History and medicinal properties of cannabis. Phcog. Rev. 2024, 18, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinon B., Molinari R., Costantini L., Merendino N. The seed of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.): nutritional quality and potential functionality for human health and nutrition. Nutr., 2020, 12, 1-59. [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, A. , Zafar U, Ahmed W., Shabbir M.A., Sameen A., Sahar A., Bhat Z.F., Kowalczewski P.L., Jarzebski M., Aadil R.M. Applications of cannabis sativa L. in food and its therapeutic potential: from a prohibited drug to a nutritional supplement, Mol. 2021, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanknecht, E.; Bachari, A.; Nassar, N.; Piva, T.; Mantri, N. Phytochemical constituents and derivatives of cannabis sativa; bridging the gap in melanoma treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Bai, M.; Song, H.; Yang, L.; Zhu, D.; Liu, H. Hemp (Cannabis sativa subsp. sativa) Chemical Composition and the Application of Hempseeds in Food Formulations. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2022, 77, 355–365. [CrossRef]

- Fike, J. Industrial hemp: renewed opportunities for an ancient crop. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2016, 35, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Davis, A.; Kumar, S.K.; Murray; B.; Zheljazkov, V.D. Industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa subsp. sativa) as an emerging source for value-added functional food ingredients and nutraceuticals. Mol. 2020, 25, 4078. [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.Y.; Corbo, F.; Crupi, P.; Clodoveo, M.L. Hemp: An Alternative Source for Various Industries and an Emerging Tool for Functional Food and Pharmaceutical Sectors. Processes. 2023, 11(3), 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raihan, A; Bijoy, T. R. A review of the industrial use and global sustainability of Cannabis sativa. Glob. Sust. Res. 2023, 2, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.A.; Andres, M.; Cole, M.; Cowley, J.M.; Augustin, M.A. Industrial hemp seed: from the field to value-added food ingredients. J. Cannabis Res. 2022, 4, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strzelczyk, M.; Lochynska, M.; Chudy, M. Systematics and Botanical Characteristics of Industrial Hemp Cannabis sativa L. J. Nat. Fibers. 2021, 19, 5804–5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michels, M; Brinkmann, A; Mußhoff, O. Economic, ecological and social perspectives of industrial hemp cultivation in Germany: a qualitative analysis. J. Environ. Manage. 2025, 389, 126117. [CrossRef]

- Basak, M.; Broadway, M.; Lewis, J.; Starkey, H.; Bloomquist, M.; Peszlen, I.; Davis, J.; Lucia, L.A.; Pal, L. A critical review of industrial fiber hemp anatomy, agronomic practices, and valorization into sustainable bioproducts. BioResources 2025, 20, 5030–5070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayit, F.; Balıkcı, E.; Yazıcı, L.; Beşcanlar, S. Investigation of the usability of hemp flour in the production of gluten-free cakes. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2024, 22, e2357282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korus, J.; Witczak, M.; Ziobro, R.; Juszczak, L. Hemp (Cannabis sativa subsp. sativa) flour and protein preparation as natural nutritional and structure-forming agents in gluten-free starch bread. Food Chem., 2017, 223, 51-59. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Sanchez, R.; Hayeard, J.; Henderson, D.; Duncan, G. D.; Russel, W. R.; Duncan, S. H.; Neacsu, M. Hemp Seed-Based Foods and Processing By-Products Are Sustainable Rich Sources of Nutrients and Plant Metabolites Supporting Dietary Biodiversity, Health, and Nutritional Needs. Foods, 2025, 14, 875. [CrossRef]

- Svec, I.; Hruskova, M. ; Properties and nutritional value of wheat bread enriched by hemp products. Potr. S. J. F. Sci. 2015, 9, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukin, A.; Bitiutskikh, K. On potential use of hemp flour in bread production. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Brasov Ser. II, 2017, 10, 117–123.

- Kowalski, S.; Mikulec, A., Litwinek, D.; Mickowska, B.; Skotnicka, M.; Oacz, J.; Karwowska, K.; Wiweocka-Gurgul, A.; Sabat, R.; Platta, A. The influence of fermentation technology on the functional ans densory propertiez of hemp bread. Mol. 2024, 29, 5455. [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs – Horizontal method for the enumeration of yeasts and moulds – Part 2: Colony count technique in products with water activity ≤ 0.95; ISO 21527-2:2008; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Wichchukit, S.; O’Mahony, M. The 9-point hedonic scale and hedonic ranking in food science: some reappraisals and alternatives. J. Sci Food Agric. 2014, 95, 2167–2178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peryam, D.R.; Pilgrim, F.J. Hedonic scale method of measuring food preferences. Food Technol. 1957, 11, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lawless, H.T.; Heymann, H. Sensory evaluation of food: Principles and practices. In Sensory Evaluation of Food, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–596. [Google Scholar]

- Stone, H.; Bleibaum, R.; Thomas, H.A. Sensory Evaluation Practices, 4th ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–448. [Google Scholar]

- Meilgaard, M.; Civille, G.V.; Carr, B.T. Sensory Evaluation Techniques, 4th ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; pp. 1–464. [Google Scholar]

- Marques, C.; Correia, E.; Dinis, L.-T.; Vilela, A. An overview of sensory characterization techniques: from classical descriptive analysis to the emergence of novel profiling methods. Foods, 2022, 11(3), 255.

- Sensory Evaluation Practices, 4th ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; pp. 1–448.

- Trinh, K.T.; Glasgow, S. On the Texture Profile Analysis Test. In Proceedings of the Food Science Conference, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand, 25–27 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pathare, P.B.; Opara, U.L.; Al-Said, F.A.-J. Colour measurement and analysis in fresh and processed foods: A review. Food Bioproc. Technol. 2013, 6, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Microbiology of food and animal feeding stuffs – Horizontal method for the detection and enumeration of Enterobacteriaceae – Part 2: Colony-count method; 21528-2:2004; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Cereals and cereal products — Determination of moisture content — Reference method; ISO 712:2009; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Vartolomei, N.; Turtoi, M. The influence of the addition of rosehip powder to wheat flour on the dough farinographic properties and bread physico-chemical characteristics. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 12035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Cereals, pulses and by-products — Determination of ash yield by incineration; ISO 2171:2023; German version DIN EN ISO 2171:2010; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Animal feeding stuffs — Determination of crude fibre content — Method with intermediate filtration; ISO 6865:2000; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO). Cereals and cereal products — Determination of starch — Method using α-amylase and amyloglucosidase. ISO 20483:2013; ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Romanian Standards Association (ASRO). SR 91:2007 – Cereals and derived products – Determination of starch content – Enzymatic method (item 13.2). ASRO: Bucharest, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu, I.; Ungureanu, E.L.; Popa, E.E.; Geicu-Cristea, M.; Drăghici, M.; Miteluț, A.C.; Mustatea, G.; Popa, M.E. The experimental development of bread with enriched nutritional properties using organic sea buckthorn pomace. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanian Standards Association (ASRO). SR 91:2007 – Cereals and derived products – Determination of starch content – Gravimetric method (item 14) . ASRO: Bucharest, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

| Attribute | Samples with WF | Samples with WWF | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | This set of samples demonstrates a more varied range of appearance scores, with some formulations receiving slightly higher ratings. This may suggest that the flour composition in this group resulted in a more visually appealing muffin, possibly due to improved crumb distribution or a lighter color. | The samples in this group exhibit moderate variation in appearance scores. The darker coloration and denser crumb structure associated with higher HF concentrations may have influenced consumers' ratings. The presence of HF can lead to a more compact crumb, affecting uniformity. | The W-HF1 samples generally have a more favorable appearance rating, which may indicate that these formulations maintained a more visually appealing structure despite HF incorporation. However, the differences are not extreme, suggesting that both groups were influenced by similar factors, such as the darkening effect of HF and crumb uniformity. |

| Aroma | The samples in this group exhibit a more pronounced variation in aroma scores. Some samples scored lower, potentially indicating that HF at higher concentrations masked the typical vanilla or buttery notes found in muffins. | The aroma scores in this group are relatively uniform, with moderate variability between samples. The addition of HF, known for its nutty and slightly earthy scent, may have altered the aroma profile. However, none of the samples seemed to have been overwhelmingly strong or unpleasant in their aroma. | The WW-HF2 samples appear to have more balanced aroma scores across different formulations, whereas Figure 4. A - samples show more variation, suggesting that HF concentration may have affected aroma perception differently between these two sample groups. |

| Texture | The texture ratings in this set appear slightly more consistent, suggesting that these formulations may have maintained a better balance between softness and elasticity. The ability of the muffin crumb to retain moisture while avoiding excessive gumminess may have contributed to these results. | The texture ratings in this group show noticeable variations, likely due to the impact of HF on crumb structure and moisture retention. Some formulations may have been perceived as too dense or firm, especially at higher HF concentrations. | The W-HF samples generally exhibit a more stable texture profile, which may indicate that this formulation group resulted in muffins with a more desirable crumb structure. Figure 4. B - samples appear to have more variability, possibly due to increased firmness or dryness in some formulations. |

| Taste | Taste ratings have slightly more variation, suggesting that some samples may have exhibited stronger taste alterations due to HF addition. Higher concentrations of HF might have contributed to more pronounced nutty and earthy notes. | Taste ratings in this group show a moderate spread, with some formulations receiving higher ratings. The influence of HF, particularly at higher concentrations, may have introduced a mild bitterness, which could have affected perception. | The WW-HF samples exhibit a more controlled spread in taste ratings, whereas Figure 4. A-samples show greater variability. This suggests that the impact of HF on taste was more noticeable in the W-HF samples, possibly due to differences in base flour or ingredient interactions. |

| Overall acceptability | The acceptability ratings in this group show more divergence, indicating that some samples were significantly preferred over others. This may imply that the formulations in this set had greater variations in sensory properties, leading to a stronger differentiation among consumers. | The overall acceptability ratings are relatively consistent, with most samples clustering around the mid-to-high range. This suggests that despite minor variations in texture, taste, and appearance, these formulations were generally well received. | The WW-HF samples exhibit a more balanced overall acceptability, while the W-HF samples show greater variation in preference. This suggests that the W-HF formulations had more noticeable differences in sensory attributes, leading to stronger opinions among consumers. |

| Sample | Firmness (N) | Cohesiveness | Elasticity | Gumminess | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| C – WF1 | 6.29 | ± 1.47 | 0.2 | ± 0.13 | 1.62 | ± 0.38 | 1.84 | ± 1.15 |

| 5% HF3 | 4.08 | ± 0.19 | 0.12 | ± 0.08 | 1.56 | ± 0.14 | 0.74 | ± 0.50 |

| 10% HF | 7.81 | ± 1.36 | 0.18 | ± 0.18 | 1.55 | ± 0.93 | 1.72 | ± 1.82 |

| 15% HF | 5.06 | ± 0.37 | 0.06 | ± 0.07 | 1.20 | ± 0.38 | 0.50 | ± 0.63 |

| 20% HF | 5.04 | ± 0.06 | -0.01 | ± 0.22 | 2.42 | ± 0.30 | -1.53 | ± 2.93 |

| C – WWF2 | 5.28 | ± 1.95 | -0.67 | - | 3.52 | - | -8.67 | - |

| 5% HF | 4.10 | ± 0.50 | 0.22 | ± 0.03 | 1.63 | ± 0.024 | 1.44 | ± 0.24 |

| 10% HF | 7.89 | ± 1.28 | 0.14 | ± 0.05 | 1.95 | ± 0.12 | 2.19 | ± 0.96 |

| 15% HF | 6.87 | ± 0.56 | 0.15 | ± 0.02 | 2.04 | ± 0.32 | 2.12 | ± 0.14 |

| 20% HF | 8.05 | ± 2.70 | 0.13 | ± 0.02 | 1.94 | ± 0.93 | 2.36 | ± 1.37 |

| Sample | Yeast and molds (CFU/g) |

|---|---|

| C – WF1 | < 10 |

| 5% HF3 | < 10 |

| 10% HF | < 10 |

| 15% HF | < 10 |

| 20% HF | < 10 |

| C – WWF2 | < 10 |

| 5% HF | < 10 |

| 10% HF | < 10 |

| 15% HF | < 10 |

| 20% HF | < 10 |

| Sample | Enterobacteriaceae (CFU/g) |

|---|---|

| C – WF1 | < 10 |

| 5% HF3 | < 10 |

| 10% HF | < 10 |

| 15% HF | < 10 |

| 20% HF | < 10 |

| C – WWF2 | < 10 |

| 5% HF | < 10 |

| 10% HF | < 10 |

| 15% HF | < 10 |

| 20% HF | < 10 |

| Sample | Moisture% | Ash% | Crude fiber% | Protein% | Fat% | Sugar% | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| C – WF1 | 17.59 | ± 0.014 | 0.95 | ± 0.028 | 2.79 | ± 0.099 | 6.89 | ± 0.028 | 27.41 | ± 0.014 | 32.05 | ± 0.007 |

| 5% HF3 | 14.58 | ± 0.014 | 1.10 | ± 0.064 | 3.98 | ± 0.191 | 8.07 | ± 0.085 | 26.08 | ± 0.219 | 39.95 | - |

| 10% HF | 14.10 | ± 0.014 | 1.25 | ± 0.021 | 5.45 | ± 0.233 | 8.59 | ± 0.021 | 26.24 | ± 0.191 | 31.40 | ± 0.014 |

| 15% HF | 14.62 | - | 1.35 | ± 0.042 | 4.64 | ± 0.269 | 8.68 | ± 0.078 | 26.18 | ± 0.014 | 29.07 | ± 0.007 |

| 20% HF | 14.45 | ± 0.007 | 1.44 | ± 0.071 | 5.87 | ± 0.099 | 9.26 | ± 0.049 | 26.09 | ± 0.049 | 29.07 | - |

| C – WWF2 | 12.88 | ± 0.007 | 1.35 | ± 0.014 | 3.64 | ± 0.304 | 8.82 | ± 0.007 | 26.66 | ± 0.042 | 31.07 | ± 0.007 |

| 5% HF | 13.80 | - | 1.38 | ± 0.014 | 4.38 | ± 0.019 | 9.29 | ± 0.042 | 26.28 | ± 0.014 | 27.76 | - |

| 10% HF | 12.78 | ± 0.007 | 1.42 | ± 0.035 | 5.66 | ± 0.453 | 9.54 | - | 26.62 | ± 0.071 | 30.40 | ± 0.007 |

| 15% HF | 13.10 | ± 0.014 | 1.59 | ± 0.014 | 7.00 | ± 0.247 | 9.81 | ± 0.021 | 26.55 | ± 0.028 | 32.33 | ± 0.071 |

| 20% HF | 10.76 | ± 0.007 | 1.67 | ± 0.007 | 7.59 | ± 0.057 | 9.95 | ± 0.028 | 27.02 | ± 0.049 | 30.73 | ± 0.007 |

| Sample | WF (%) | WWF (%) | HF (%) | Sugar (%) | Butter (%) | Eggs (%) | Baking soda (%) | Flavor (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C – WF1 | 30.44 | – | – | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| 5% HF3 | 28.92 | – | 1.52 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| 10% HF | 27.40 | – | 3.04 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| 15% HF | 25.88 | – | 4.57 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| 20% HF | 24.35 | – | 6.09 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| 30% HF | 21.31 | – | 9.13 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| 40% HF | 18.26 | – | 12.18 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| C – WWF2 | – | 30.44 | – | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| 5% HF | – | 28.92 | 1.52 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| 10% HF | – | 27.40 | 3.04 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| 15% HF | – | 25.88 | 4.57 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| 20% HF | – | 24.35 | 6.09 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| 30% HF | – | 21.31 | 9.13 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

| 40% HF | – | 18.26 | 12.18 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 22.83 | 0.76 | 0.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).