Submitted:

10 July 2025

Posted:

11 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- –

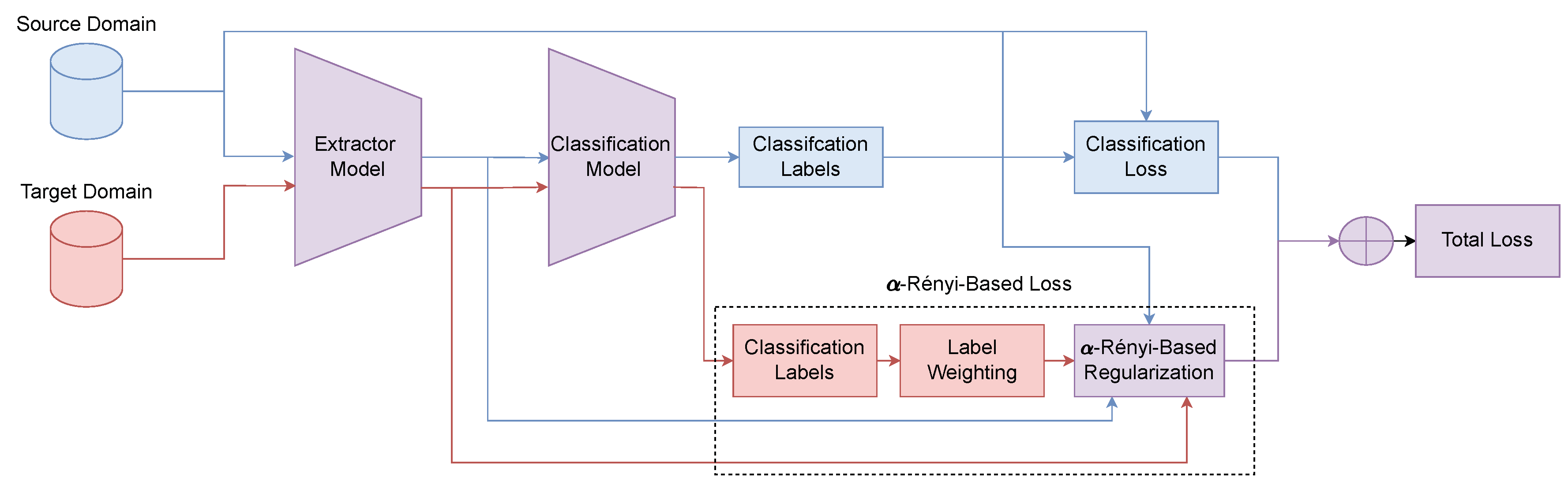

- Deep Feature Extraction: A shared ResNet-18 backbone encodes samples from both source and target domains into a latent representation space.

- –

- Noise-Aware Label Weighting: An entropy-derived confidence score is used to down-weight low-confidence pseudo-labels in the target domain, improving robustness against noisy or ambiguous predictions.

- –

- Class-Conditional Alignment via Rényi-based entropy: A novel entropy-based regularization term is applied over kernel Gram matrices to minimize divergence between class-wise source and target feature distributions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Kernel Methods Fundamentals

2.2. Kernel-based -Rényi’s Entropy Estimation

- –

- Non-parametric: It makes no prior assumptions about the underlying data distribution, making it highly suitable for the complex and high-dimensional feature spaces learned by neural networks.

- –

- Differentiable: The entropy loss is a function of the Gram matrix elements, which are themselves differentiable functions of the feature vectors produced by a given network. This allows gradients to be backpropagated through the kernel computations to the network’s parameters, enabling end-to-end training.

- –

- Robust: The entropy is calculated based on the collective geometric structure of the data, as captured by all pairwise interactions in the Gram matrix. This makes the measure inherently robust to outliers, which would have a limited impact on the overall sum of kernel values.

- –

- Joint Entropy - (JE). Let and be the Gram matrices computed from the feature sets of X and Y, respectively. The joint entropy based on the -Rényi estimator is defined as [58]:where , and ⊙ denotes the Hadamard product. Of note, the joint matrix captures the similarity between pairs of samples in the joint feature space.

- –

- Mutual Information - (MI). It quantifies the statistical dependence between two variables. In the matrix-based framework, it is defined in analogy to its classic information-theoretic definition:where each entropy term is computed from its respective (normalized) Gram matrix. Maximizing MI is a common objective in representation learning, as it encourages a representation to retain information about a relevant variable.

- –

-

Conditional Entropy - (CE). It measures the remaining uncertainty in a variable X given that Y is known. It is defined as:Minimizing conditional entropy is equivalent to making X more predictable from Y.

2.3. Domain Adaptation with -Rényi Entropy-based Label Weighting and Regularization

3. Experimental Set-Up

3.1. Tested Datasets

- –

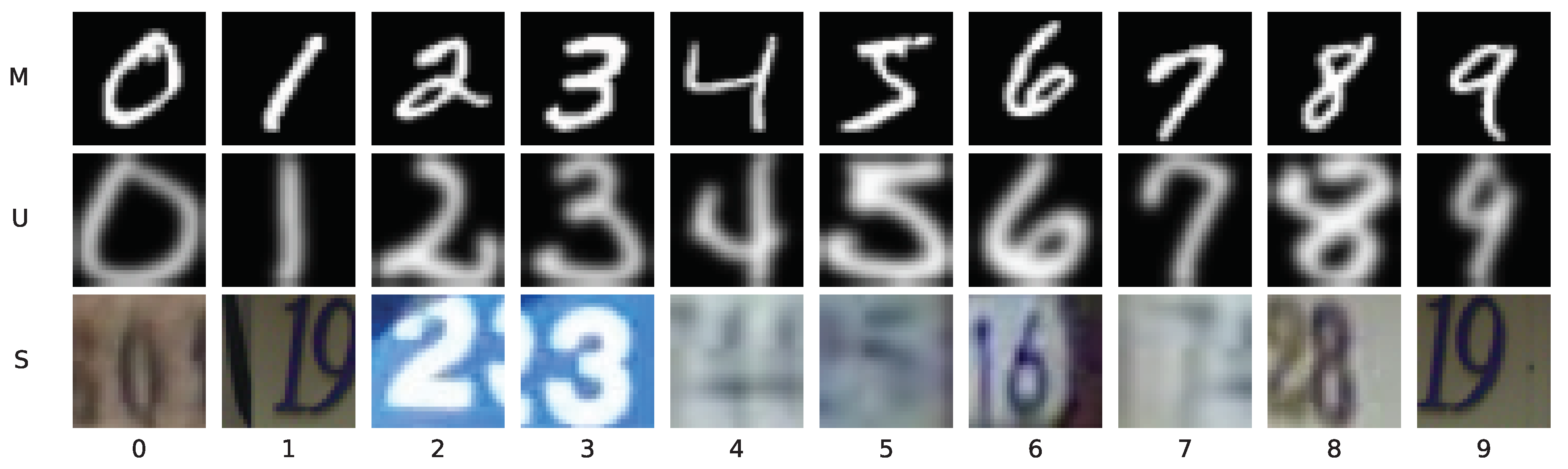

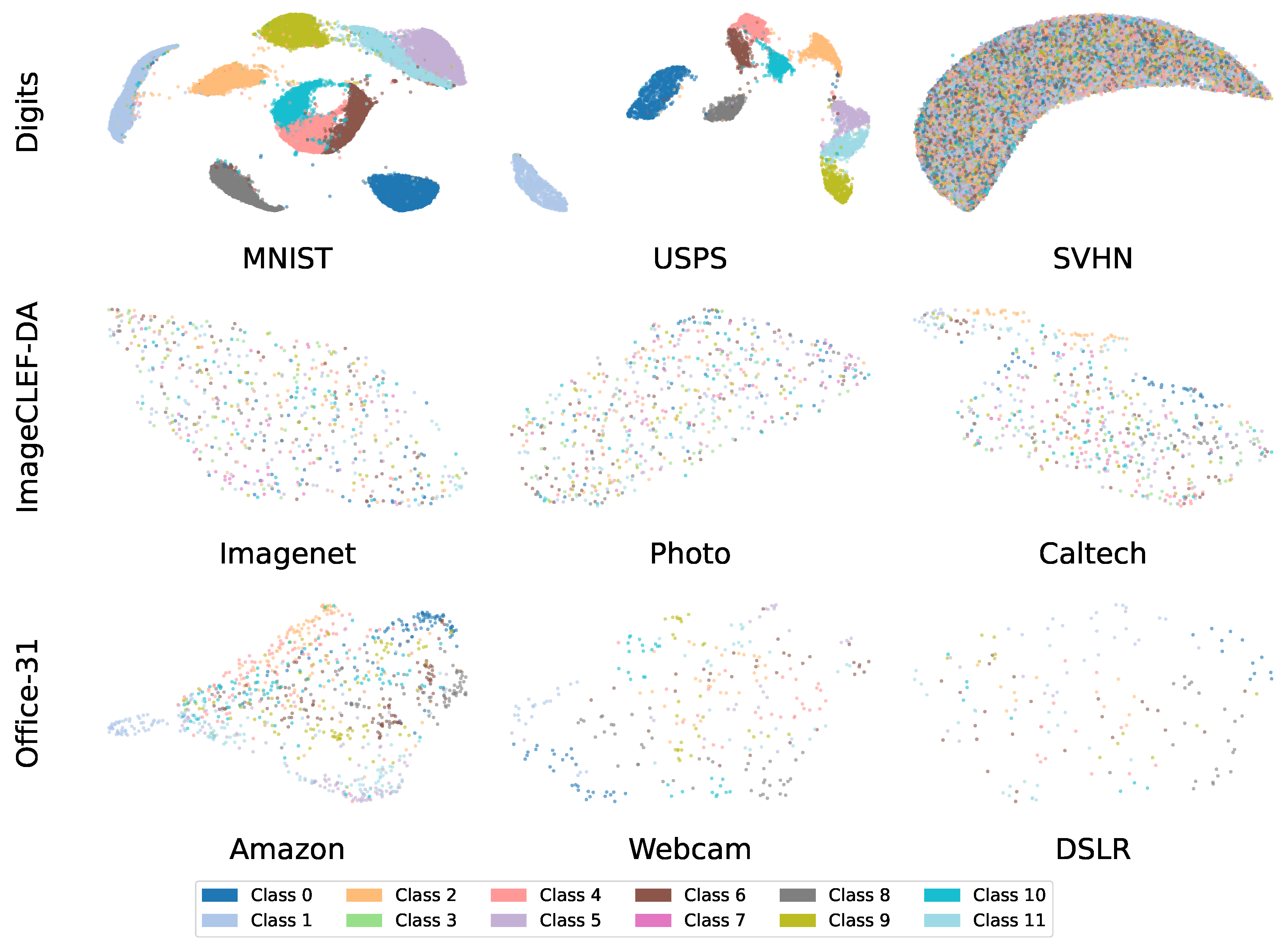

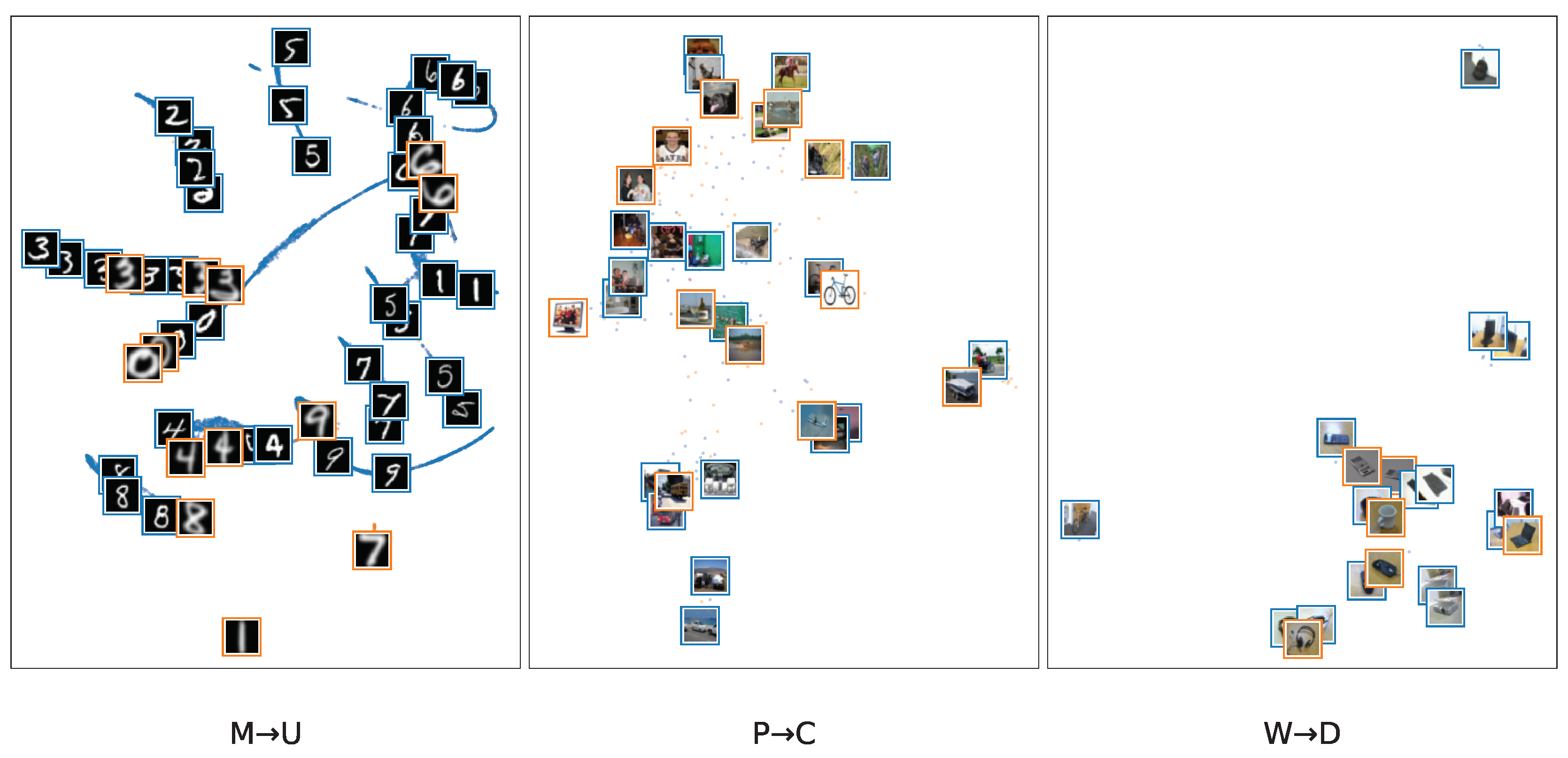

- Digits: This benchmark suite is designed for evaluating domain adaptation on digit recognition tasks, spanning both handwritten and natural-scene digits. It comprises three standard datasets: MNIST (M), a large database of handwritten digits; USPS (U), another handwritten digit set characterized by its lower resolution; and SVHN (S), which contains house numbers cropped from real-world street-level images [60]. Notably, the S domain is particularly challenging due to its significant variability in lighting, background clutter, and visual styles compared to M and U (see Figure 2).

- –

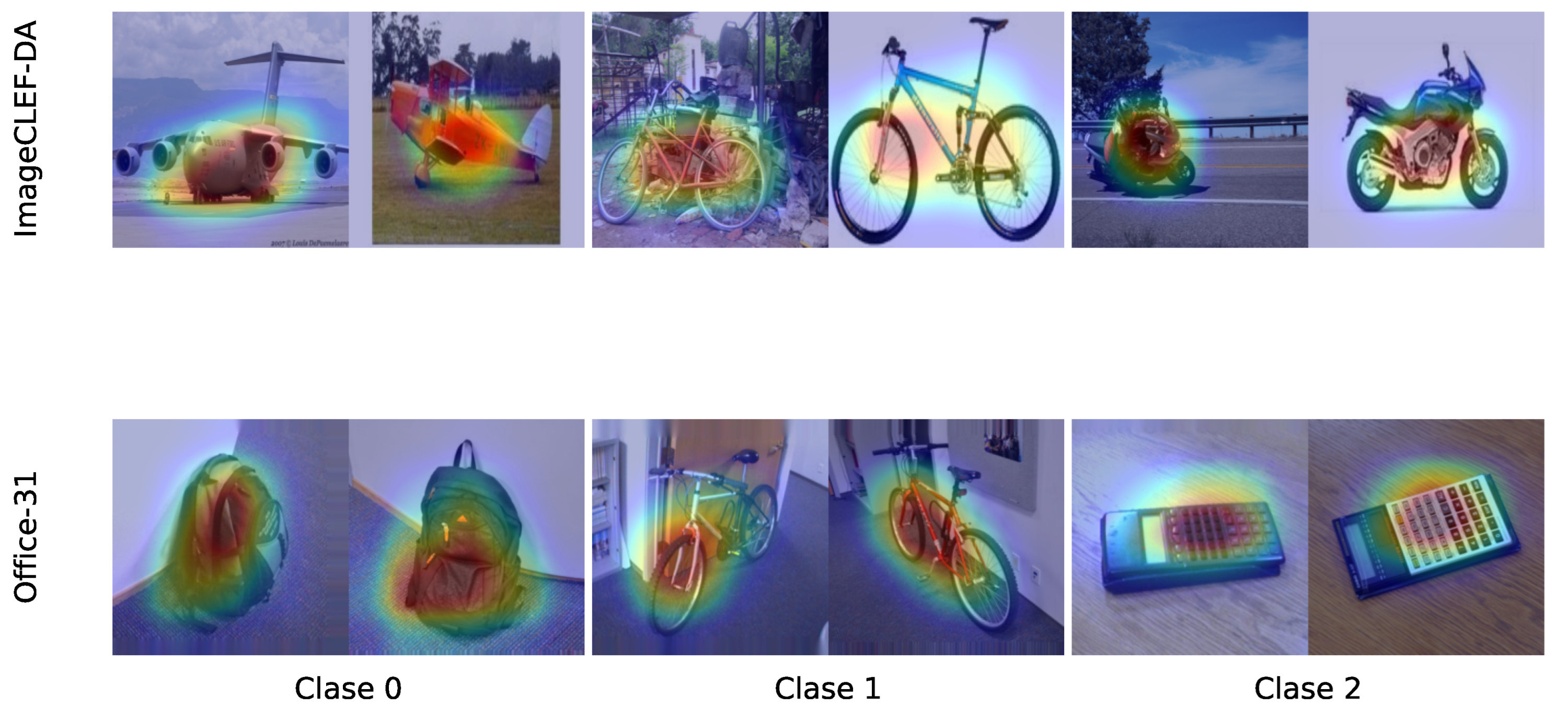

- ImageCLEF-DA: This is a standard benchmark for unsupervised domain adaptation, organized as part of the ImageCLEF evaluation campaign. It comprises 12 common object classes shared across three distinct visual domains: Caltech-256 (C), ImageNet ILSVRC 2012 (I), and Pascal VOC 2012 (P), see Figure 3. Each domain contains 600 images, with a balanced distribution of 50 images per class [61]. All images are resized to pixels.

- –

- Office-31: This is one of the most widely used benchmarks for visual domain adaptation. It consists of 4110 images across 31 object classes, sourced from three domains with distinct visual characteristics: Amazon (A), which features centered objects on a clean, white background under controlled lighting; Webcam (W), containing low-resolution images with typical noise and color artifacts; and DSLR (D), which includes high-resolution images with varying focus and lighting conditions [62]. For this study, we selected a subset of ten shared classes, see Figure 4.

3.2. Deep Learning Architectures

3.3. Assessment and Method Comparison

- –

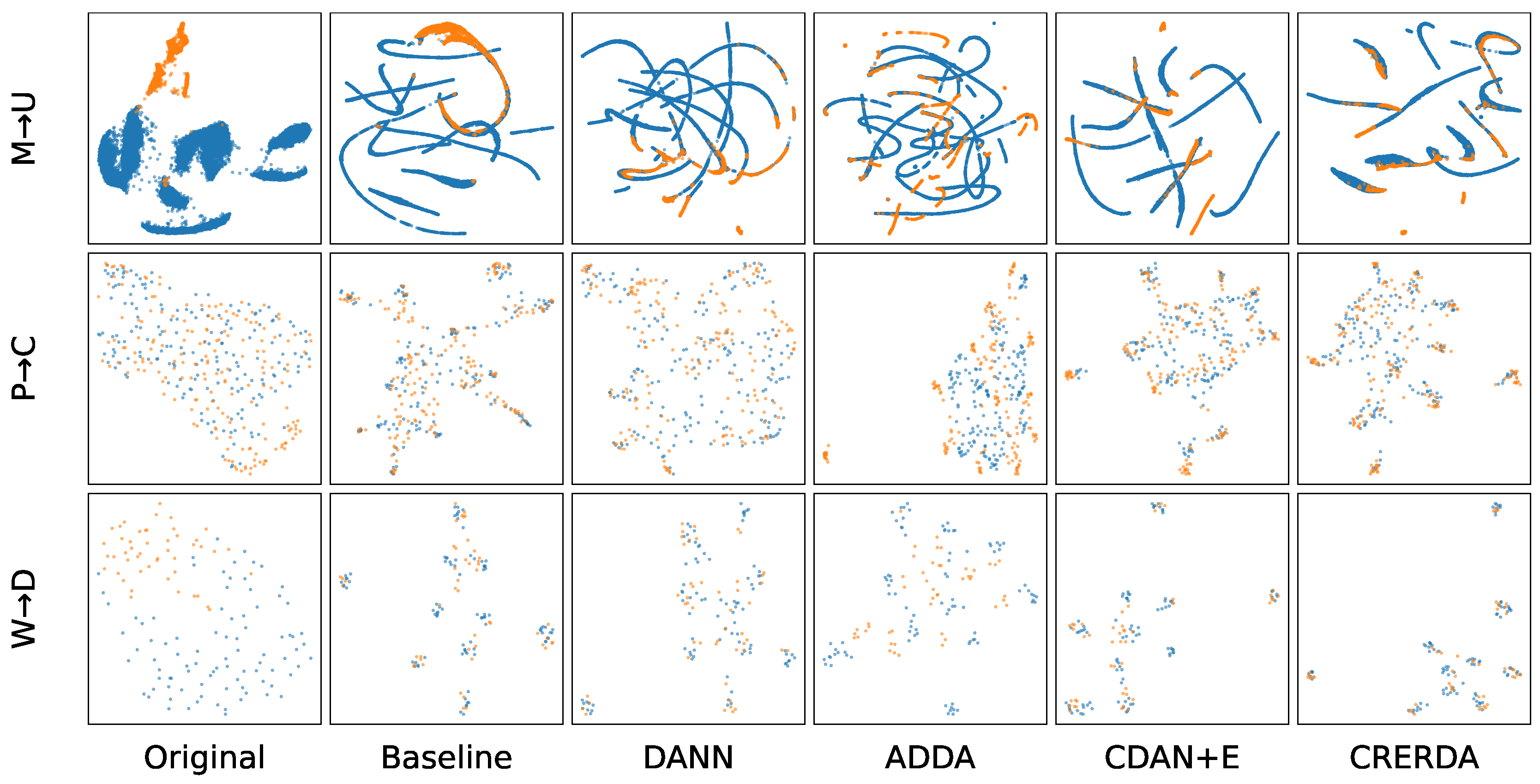

- DANN: The Domain-Adversarial Neural Network incorporates a domain discriminator linked via a Gradient Reversal Layer (GRL), enabling adversarial training of the feature extractor [63]. This configuration encourages the learning of domain-invariant features while preserving class separability.

- –

- ADDA: The Adversarial Discriminative Domain Adaptation framework separates training into two stages: an initial supervised phase for training the source encoder and classifier, followed by adversarial fine-tuning of the target encoder (initialized with source weights) to align the source and target distributions [64]. The classifier remains fixed during this second phase.

- –

- CDAN+E: The Conditional Domain Adversarial Network with Entropy Minimization extends adversarial adaptation by feeding the domain discriminator with multilinear features, obtained as the outer product between feature representations and soft classifier predictions [65]. Additionally, an entropy regularization term is applied to the target predictions to encourage confident and well-structured outputs [66].

- –

- CREDA: Our proposed method integrates a supervised classification loss with a conditional divergence term based on Rényi entropy. The objective is to promote intra-class compactness and inter-domain alignment through class-wise kernel-based weighting schemes, yielding representations that are simultaneously discriminative and domain-invariant.

3.4. Training Details

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Lu, X.; Yao, X.; Jiang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Xu, F.; Zhu, Q. Remaining useful life prediction model of cross-domain rolling bearing via dynamic hybrid domain adaptation and attention contrastive learning. Computers in Industry 2025, 164, 104172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Shi, C.; Yue, S.; Zhu, F.; Jin, Z. Domain Adaptation Network Based on Multi-Level Feature Alignment Constraints for Cross Scene Hyperspectral Image Classification. Knowledge-Based Systems, 2025, p. 113972.

- Huang, X.Y.; Chen, S.Y.; Wei, C.S. Enhancing Low-Density EEG-Based Brain-Computer Interfacing With Similarity-Keeping Knowledge Distillation. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2023, 8, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Zhao, S.; Zhu, J.; Tang, W.; Xu, Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, G.; Xing, T.; Xu, P.; Yao, H. Multi-source domain adaptation for panoramic semantic segmentation. Information Fusion 2025, 117, 102909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, M.N.; Khan, N. Towards Practical Emotion Recognition: An Unsupervised Source-Free Approach for EEG Domain Adaptation. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2504.03707 2025.

- Wang, J.; Lan, C.; Liu, C.; Ouyang, Y.; Qin, T.; Lu, W.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, W.; Yu, P.S. Generalizing to unseen domains: A survey on domain generalization. IEEE transactions on knowledge and data engineering 2022, 35, 8052–8072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galappaththige, C.J.; Baliah, S.; Gunawardhana, M.; Khan, M.H. Towards generalizing to unseen domains with few labels. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2024, pp. 23691–23700.

- Zhu, H.; Bai, J.; Li, N.; Li, X.; Liu, D.; Buckeridge, D.L.; Li, Y. FedWeight: mitigating covariate shift of federated learning on electronic health records data through patients re-weighting. npj Digital Medicine 2025, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Liang, J.; Chen, T. Addressing Domain Shift via Imbalance-Aware Domain Adaptation in Embryo Development Assessment. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2501.04958 2025.

- Yuksel, G.; Kamps, J. Interpretability Analysis of Domain Adapted Dense Retrievers. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2501.14459 2025.

- Adachi, K.; Yamaguchi, S.; Kumagai, A.; Hamagami, T. Test-time Adaptation for Regression by Subspace Alignment. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2410.03263 2024.

- Zhang, G.; Zhou, T.; Cai, Y. CORAL-based Domain Adaptation Algorithm for Improving the Applicability of Machine Learning Models in Detecting Motor Bearing Failures. Journal of Computational Methods in Engineering Applications, 2023, pp. 1–17.

- Wang, J.; Feng, W.; Chen, Y.; Yu, H.; Huang, M.; Yu, P.S. Visual domain adaptation with manifold embedded distribution alignment. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th ACM international conference on Multimedia, 2018, pp. 402–410.

- Yun, K.; Satou, H. GAMA++: Disentangled Geometric Alignment with Adaptive Contrastive Perturbation for Reliable Domain Transfer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.152412025.

- Sanodiya, R.K.; Yao, L. A subspace based transfer joint matching with Laplacian regularization for visual domain adaptation. Sensors 2020, 20, 4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.; Xu, X.; Jia, T.; Zhang, D.; Wu, X. A multi-source transfer joint matching method for inter-subject motor imagery decoding. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering 2023, 31, 1258–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battu, R.S.; Agathos, K.; Monsalve, J.M.L.; Worden, K.; Papatheou, E. Combining transfer learning and numerical modelling to deal with the lack of training data in data-based SHM. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2025, 595, 118710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, M.O.; Figueiredo, E.; da Silva, S.; Cury, A. Foundations and applicability of transfer learning for structural health monitoring of bridges. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2023, 204, 110766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Li, L.; Zu, W.; Feng, W.; Hang, W. Adaptive deep feature representation learning for cross-subject EEG decoding. BMC bioinformatics 2024, 25, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Xiang, D.; Liu, T.; Xu, F.; Fang, K. Deep discriminative domain adaptation network considering sampling frequency for cross-domain mechanical fault diagnosis. Expert Systems with Applications 2025, 280, 127296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Lan, C.; Zeng, W.; Chen, Z. Metaalign: Coordinating domain alignment and classification for unsupervised domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2021, pp. 16643–16653.

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, L.; Jin, R.; Tan, T. Free lunch for domain adversarial training: Environment label smoothing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.027532023.

- Lu, M.; Huang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, D. DaMSTF: Domain adversarial learning enhanced meta self-training for domain adaptation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.02753, arXiv:2308.02753 2023.

- Wu, Y.; Spathis, D.; Jia, H.; Perez-Pozuelo, I.; Gonzales, T.I.; Brage, S.; Wareham, N.; Mascolo, C. Udama: Unsupervised domain adaptation through multi-discriminator adversarial training with noisy labels improves cardio-fitness prediction. In Proceedings of the Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference. PMLR; 2023; pp. 863–883. [Google Scholar]

- Mehra, A.; Kailkhura, B.; Chen, P.Y.; Hamm, J. Understanding the limits of unsupervised domain adaptation via data poisoning. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 17347–17359. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhuang, F.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Shi, Z.; Wu, W.; He, Q. Multi-representation adaptation network for cross-domain image classification. Neural Networks 2019, 119, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madadi, Y.; Seydi, V.; Sun, J.; Chaum, E.; Yousefi, S. Stacking Ensemble Learning in Deep Domain Adaptation for Ophthalmic Image Classification. In Proceedings of the Ophthalmic Medical Image Analysis: 8th InternationalWorkshop, OMIA 2021, Held in Conjunction with MICCAI 2021, Strasbourg, France, September 27, 2021, Proceedings 8. Springer, 2021, pp. 168–178.

- Zhu, Y.; Zhuang, F.; Wang, J.; Ke, G.; Chen, J.; Bian, J.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. Deep subdomain adaptation network for image classification. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2020, 32, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, H.; Li, S.; Wei, D.; Zou, X.; Si, L.; Shao, H. Multi-kernel weighted joint domain adaptation network for cross-condition fault diagnosis of rolling bearings. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2025, 261, 111109. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Chen, H.; Wei, Z.; Jin, X.; Tan, X.; Jin, Y.; Chen, E. Reusing the task-specific classifier as a discriminator: Discriminator-free adversarial domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2022, pp. 7181–7190.

- Lu, W.; Luu, R.K.; Buehler, M.J. Fine-tuning large language models for domain adaptation: Exploration of training strategies, scaling, model merging and synergistic capabilities. npj Computational Materials 2025, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Liu, Z.; Wu, B. Teacher-student competition for unsupervised domain adaptation. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th international conference on pattern recognition (ICPR). IEEE; 2021; pp. 8291–8298. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, E.; Rodriguez, J.; Young, E. An In-Depth Analysis of Adversarial Discriminative Domain Adaptation for Digit Classification. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2412.19391 2024.

- Kumar, A.; Raghunathan, A.; Jones, R.; Ma, T.; Liang, P. Fine-tuning can distort pretrained features and underperform out-of-distribution. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.100542022.

- Liu, Y.; Wong, W.; Liu, C.; Luo, X.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J. Mutual Learning for SAM Adaptation: A Dual Collaborative Network Framework for Source-Free Domain Transfer. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 42nd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2025. Poster presentation.

- Gao, Y.; Baucom, B.; Rose, K.; Gordon, K.; Wang, H.; Stankovic, J.A. E-ADDA: Unsupervised Adversarial Domain Adaptation Enhanced by a New Mahalanobis Distance Loss for Smart Computing. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Smart Computing (SMARTCOMP). IEEE; 2023; pp. 172–179. [Google Scholar]

- Dan, J.; Jin, T.; Chi, H.; Dong, S.; Xie, H.; Cao, K.; Yang, X. Trust-aware conditional adversarial domain adaptation with feature norm alignment. Neural Networks 2023, 168, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Naidu, R.; Michael, J.; Kundu, S.S. Ss-cam: Smoothed score-cam for sharper visual feature localization. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2006.14255 2020.

- Mirkes, E.M.; Bac, J.; Fouché, A.; Stasenko, S.V.; Zinovyev, A.; Gorban, A.N. Domain adaptation principal component analysis: base linear method for learning with out-of-distribution data. Entropy 2022, 25, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.; Park, J.; Shin, S.; Seo, J. Stop Misusing t-SNE and UMAP for Visual Analytics. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.08725, arXiv:2506.08725 2025.

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Melville, J. Umap: Uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.034262018.

- Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Rudin, C.; Browne, E.P. Towards a comprehensive evaluation of dimension reduction methods for transcriptomic data visualization. Communications biology 2022, 5, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, G.; Lan, C.; Zeng, W.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z. Toalign: Task-oriented alignment for unsupervised domain adaptation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2021, 34, 13834–13846. [Google Scholar]

- Langbein, S.H.; Koenen, N.; Wright, M.N. Gradient-based Explanations for Deep Learning Survival Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.049702025.

- Santos, R.; Pedrosa, J.; Mendonça, A.M.; Campilho, A. Grad-CAM: The impact of large receptive fields and other caveats. Computer Vision and Image Understanding, 2025, p. 104383.

- Singh, A.K.; Chaudhuri, D.; Singh, M.P.; Chattopadhyay, S. Integrative CAM: Adaptive Layer Fusion for Comprehensive Interpretation of CNNs. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2412.01354 2024.

- Ahmad, J.; Rehman, M.I.U.; ul Islam, M.S.; Rashid, A.; Khalid, M.Z.; Rashid, A. LAYER-WISE RELEVANCE PROPAGATION IN LARGE-SCALE NEURAL NETWORKS FOR MEDICAL DIAGNOSIS.

- Ding, R.; Liu, J.; Hua, K.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Shao, M.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J. Leveraging data mining, active learning, and domain adaptation for efficient discovery of advanced oxygen evolution electrocatalysts. Science Advances 2025, 11, eadr9038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K.P. Probabilistic machine learning: an introduction; MIT press, 2022.

- Scholkopf, B.; Smola, A.J. Learning with kernels: support vector machines, regularization, optimization, and beyond; MIT press, 2018.

- Wilson, A.; Adams, R. Gaussian process kernels for pattern discovery and extrapolation. In Proceedings of the International conference on machine learning. PMLR; 2013; pp. 1067–1075. [Google Scholar]

- Principe, J.C. Information theoretic learning: Renyi’s entropy and kernel perspectives; Springer Science & Business Media, 2010.

- Bishop, C.M.; Nasrabadi, N.M. Pattern recognition and machine learning; Vol. 4, Springer, 2006.

- Silverman, B.W. Density estimation for statistics and data analysis; Routledge, 2018.

- Xu, J.W.; Paiva, A.R.; Park, I.; Principe, J.C. A reproducing kernel Hilbert space framework for information-theoretic learning. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing 2008, 56, 5891–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromiley, P. Products and convolutions of Gaussian probability density functions. Tina-Vision Memo 2003, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Giraldo, L.G.S.; Rao, M.; Principe, J.C. Measures of entropy from data using infinitely divisible kernels. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 2014, 61, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, L.G.S.; Principe, J.C. Information theoretic learning with infinitely divisible kernels. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1301.3551 2013.

- Hatefi, E.; Karshenas, H.; Adibi, P. Probabilistic similarity preservation for distribution discrepancy reduction in domain adaptation. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2025, 158, 111426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaranarayanan, S.; Balaji, Y.; Castillo, C.D.; Chellappa, R. Generate to adapt: Aligning domains using generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2018, pp. 8503–8512.

- Cheng, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, B.; Zhou, K.; Da, Q.; Yang, Y. Foreground object structure transfer for unsupervised domain adaptation. International Journal of Intelligent Systems 2022, 37, 8968–8987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odusami, M.; Maskeliūnas, R.; Damaševičius, R.; Krilavičius, T. Analysis of Features of Alzheimer’s Disease: Detection of Early Stage from Functional Brain Changes in Magnetic Resonance Images Using a Finetuned ResNet18 Network. Diagnostics 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Song, X.; Yang, Y.; Hei, X.; Feng, N.; Yang, X. An improved multi-channel and multi-scale domain adversarial neural network for fault diagnosis of the rolling bearing. Control Engineering Practice 2025, 154, 106120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, H.; Ma, N.; Zhu, S. Cross working conditions manufacturing process monitoring using deep convolutional adversarial discriminative domain adaptation network. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture, 2025, p. 09544054251324677.

- Deng, M.; Zhou, D.; Ao, J.; Xu, X.; Li, Z. Bearing fault diagnosis of variable working conditions based on conditional domain adversarial-joint maximum mean discrepancy. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 2025, pp. 1–18.

- Feng, Y.; Liu, P.; Du, Y.; Jiang, Z. Cross working condition bearing fault diagnosis based on the combination of multimodal network and entropy conditional domain adversarial network. Journal of Vibration and Control 2024, 30, 5375–5386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Ma, X.; Fan, J. Federated t-sne and umap for distributed data visualization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2025, Vol. 39, pp. 20014–20023.

- Raveenthini, M.; Lavanya, R.; Benitez, R. Grad-CAM based explanations for multiocular disease detection using Xception net. Image and Vision Computing, 2025, p. 105419.

- Long, M.; Cao, Z.; Wang, J.; Jordan, M.I. Conditional adversarial domain adaptation. Advances in neural information processing systems 2018, 31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhuo, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, S.; Fang, Y. Rethinking Effectiveness of Unsupervised Domain Adaptation Models: a Smoothness Perspective. In Proceedings of the ACCV, 2022. shows diminishing gains of UDA methods with ResNet-50 vs stronger backbones [76]. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, K.; Kim, D.; Teterwak, P.; Sclaroff, S.; Darrell, T.; Saenko, K. Tune it the Right Way: Unsupervised Validation of Domain Adaptation via Soft Neighborhood Density. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2108.10860 2021. highlights the importance of hyperparameter tuning in UDA without target labels [?].

- Chen, Q.; Zhuang, X. Incorporating Pre-training Data Matters in Unsupervised Domain Adaptation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 2023. addresses pre-training and mentions source-free and few-shot scenarios [? ].

- Deng, Z.; Zhou, K.; Yang, Y.; Xiang, T. Domain Attention Consistency for MultiSource Domain Adaptation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Belal, A.; et al. Attention-based Class-Conditioned Alignment for Multi-Source Domain Adaptation of Object Detectors. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2403.09918 2024.

| Layer name | Type | Input shape | Output shape | Param. # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | InputLayer | 0 | ||

| Conv1 | Conv2D + BN + ReLU | 9,408 | ||

| MaxPool | MaxPooling | 0 | ||

| Layer1 | Residual Block ×2 | 73,728 | ||

| Layer2 | Residual Block ×2 | 230,144 | ||

| Layer3 | Residual Block ×2 | 919,040 | ||

| Layer4 | Residual Block ×2 | 3,674,112 | ||

| AvgPool | GlobalAvgPooling | 0 | ||

| Flatten | Flatten | 0 |

| Layer name | Type | Input shape | Output shape | Param. # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | InputLayer | 0 | ||

| FC1 | Dense | 131,328 | ||

| BN1 | BatchNorm | 512 | ||

| ReLU1 | Activation | 0 | ||

| FC2 | Dense | 32,896 | ||

| BN2 | BatchNorm | 256 | ||

| ReLU2 | Activation | 0 | ||

| Output | Dense | |||

| Softmax | Activation | 0 |

| Layer name | Type | Input shape | Output shape | Param. # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input | InputLayer | 0 | ||

| FC1 | Dense | 131,328 | ||

| ReLU1 | Activation | 0 | ||

| FC2 | Dense | 32,896 | ||

| ReLU2 | Activation | 0 | ||

| Output | Dense (Sigmoid) | 129 |

| Method | M → U | M → S | U → M | U → S | S → M | S → U | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 24.19 ± 15.66 | 19.59 ± 13.82 | 76.64 ± 15.49 | 9.68 ± 10.60 | 55.82 ± 18.09 | 72.94 ± 17.30 | 43.81 ± 15.83 |

| DANN | 87.20 ± 12.26 | 22.39 ± 14.68 | 82.90 ± 13.07 | 24.19 ± 15.66 | 82.11 ± 13.27 | 76.87 ± 14.64 | 62.61 ± 13.76 |

| ADDA | 94.33 ± 7.11 | 40.51 ± 18.16 | 91.66 ± 9.56 | 26.95 ± 15.20 | 77.26 ± 14.92 | 66.91 ± 16.06 | 66.60 ± 13.83 |

| CDAN | 88.57 ± 10.33 | 19.22 ± 14.07 | 81.54 ± 12.98 | 15.48 ± 12.90 | 85.33 ± 12.76 | 84.55 ± 12.89 | 62.45 ± 12.99 |

| CREDA | 98.17 ± 4.68 | 30.48 ± 17.10 | 89.29 ± 10.79 | 25.98 ± 15.75 | 76.48 ± 14.64 | 83.73 ± 12.53 | 67.69 ± 12.92 |

| Method | I → P | I → C | P → I | P → C | C → I | C → P | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 58.00 ± 21.71 | 76.83 ± 21.52 | 68.00 ± 19.30 | 76.50 ± 19.05 | 49.83 ± 24.44 | 38.67 ± 25.60 | 61.64 ± 20.65 |

| DANN | 61.11 ± 23.13 | 62.22 ± 16.39 | 70.00 ± 16.10 | 55.56 ± 27.35 | 62.22 ± 18.04 | 51.11 ± 23.13 | 60.70 ± 19.36 |

| ADDA | 52.22 ± 21.21 | 72.22 ± 18.81 | 77.78 ± 15.39 | 75.56 ± 15.84 | 58.89 ± 22.82 | 47.78 ± 22.27 | 64.07 ± 19.72 |

| CDAN+E | 53.33 ± 22.69 | 80.00 ± 11.31 | 71.11 ± 14.92 | 76.67 ± 16.96 | 64.44 ± 22.19 | 52.22 ± 20.53 | 66.63 ± 18.43 |

| CREDA | 52.22 ± 21.21 | 76.67 ± 11.92 | 74.44 ± 13.55 | 80.00 ± 19.58 | 65.56 ± 17.54 | 54.44 ± 18.72 | 67.56 ± 17.72 |

| Method | A → W | A → D | D → A | D → W | W → A | W → D | Avg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 50.51 ± 29.45 | 55.41 ± 25.37 | 46.56 ± 34.31 | 78.98 ± 28.90 | 54.91 ± 34.50 | 96.82 ± 7.98 | 63.03 ± 26.76 |

| DANN | 73.33 ± 12.62 | 66.67 ± 28.87 | 36.81 ± 18.92 | 77.78 ± 9.41 | 51.39 ± 23.83 | 95.83 ± 7.22 | 66.30 ± 16.81 |

| ADDA | 84.44 ± 14.61 | 91.67 ± 7.22 | 20.14 ± 12.23 | 71.11 ± 7.36 | 14.58 ± 10.72 | 79.17 ± 7.22 | 60.19 ± 9.56 |

| CDAN+E | 80.00 ± 18.96 | 66.67 ± 26.02 | 60.42 ± 20.22 | 93.33 ± 6.85 | 56.94 ± 16.73 | 91.67 ± 7.22 | 74.17 ± 16.50 |

| CREDA | 82.22 ± 17.08 | 79.17 ± 19.09 | 70.83 ± 17.15 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 71.53 ± 11.98 | 100.00 ± 0.00 | 81.07 ± 13.85 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).