This section presents an active learning algorithm that integrates adversarial training with feature fusion for boundary data samples. This method employs adversarial training to enhance model efficiency, thereby strengthening performance when processing noisy and complex environmental data. Simultaneously, the active learning strategy reduces the required number of training samples, lowering overall training costs. Specifically, in our boundary data feature fusion approach for active learning, samples selected in each round are initially augmented through adversarial training to generate adversarial counterparts. These adversarial samples are subsequently merged with the existing labeled pool, enabling the model to fully exploit the augmented data during updates.

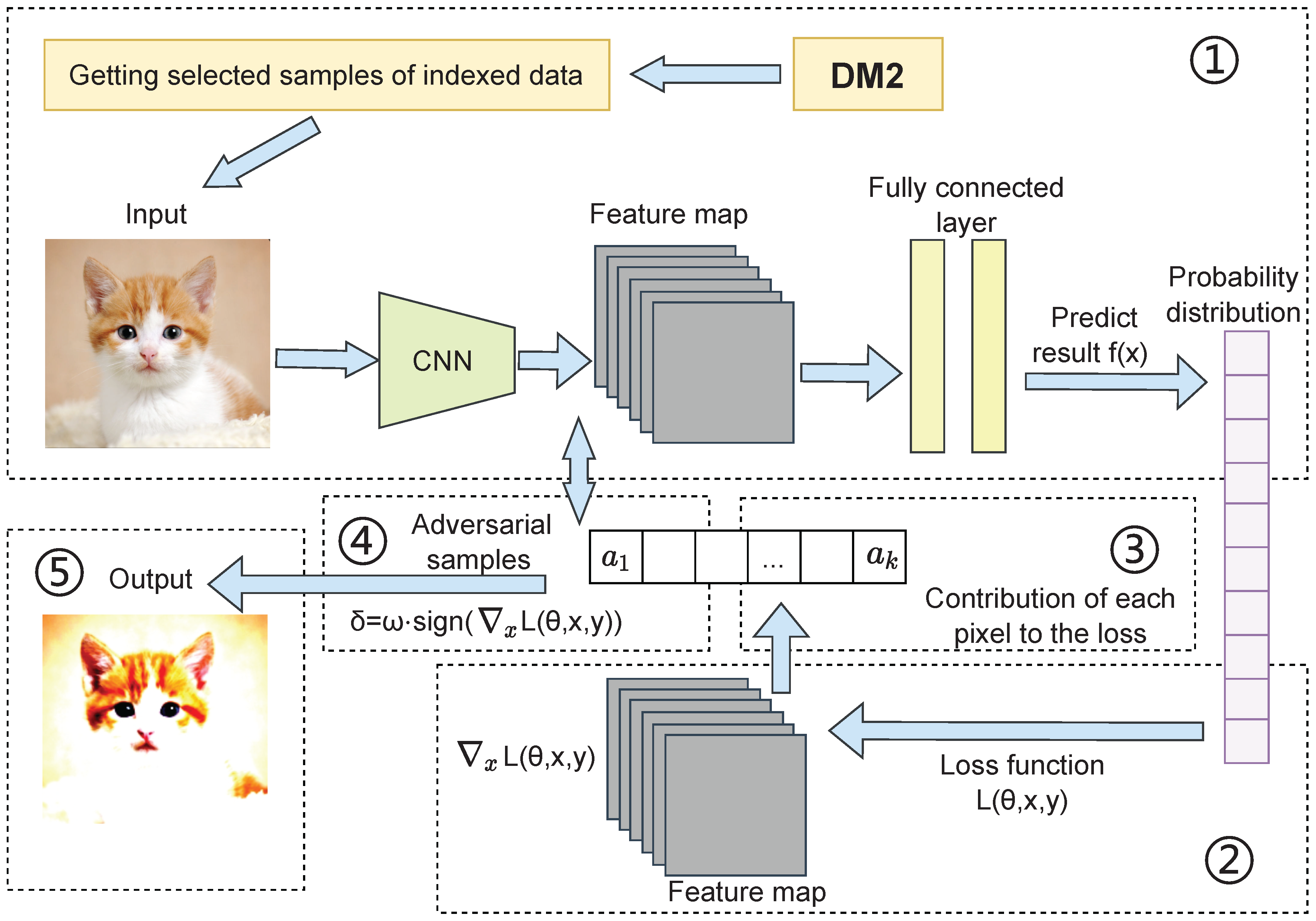

The advantage of this approach lies in its incorporation of active learning properties to reduce labeled data requirements while leveraging adversarial training to enhance the model’s classification capabilities, particularly when confronting noise and interference in real-world scenarios. Through this combination, the model’s information recognition performance is significantly improved, achieving more accurate classification in complex environments and demonstrating adaptability across diverse application scenarios. This algorithm not only improves model stability and classification accuracy but also reduces training sample requirements while adapting to large-scale dataset challenges, offering substantial practical value, especially in applications requiring rapid deployment and efficient training. The complete methodological process is illustrated in

Figure 3.

4.1. FGSM Confrontation Training

Adversarial training serves as a method to improve model generalization by incorporating adversarial samples into the training dataset during the training process. This approach compels the model to learn from these challenging examples, thereby enhancing its ability to defend against adversarial perturbations. The Fast Gradient Sign Method (FGSM) represents one of the most widely used techniques for generating adversarial samples, and FGSM adversarial training constitutes a training methodology that employs FGSM to generate adversarial samples and incorporate them into the training set [

33].

FGSM is an algorithm that efficiently generates adversarial perturbations by computing the gradient of the loss function with respect to the input. The fundamental principle involves applying a small perturbation along the direction of the loss function’s gradient to input samples, thereby causing the model to produce erroneous predictions. This perturbation is computed individually for each input sample, making it inherently "sample-specific" [

34]. The FGSM generation process follows these specific steps:

Calculate the gradient: For each input sample and its corresponding label, we first compute the gradient of the loss function with respect to the input:

where

represents the loss function with model parameters

, input sample

x, and true label

y. This gradient indicates the direction in which small changes to the input would most significantly increase the loss.

Using the computed gradient to generate adversarial perturbations, the key principle of FGSM involves computing the sign of the gradient (representing the gradient’s direction) and adding perturbations along that direction. The perturbation magnitude is controlled by a small constant parameter:

where

is the sign function that extracts the sign of each element in the gradient vector, and

is the hyperparameter that controls the perturbation magnitude. This formula represents the process of applying a small perturbation to input samples along the direction of the loss function’s gradient. The sign function ensures that the perturbation moves in the direction that would maximally increase the loss, while the

parameter bounds the perturbation size to maintain the adversarial sample’s similarity to the original input.

The generated adversarial samples are incorporated alongside the original samples during the training process, enabling the model to learn correct predictions when confronted with adversarially perturbed inputs. This approach enhances the model’s robustness by exposing it to challenging examples that lie near the decision boundary.

In adversarial training, the training process comprises two complementary components. First, positive sample training follows the traditional approach by utilizing original data for model training. Second, adversarial sample training incorporates adversarial samples generated using FGSM into the training data. During each training step, a batch of data is selected from the training set, where each sample consists of an input x and its corresponding label y. FGSM is then applied to generate adversarial perturbations for each sample, producing the corresponding adversarial examples.

The training procedure calculates losses for both the original samples and their adversarial counterparts, combining these losses for backpropagation to update model parameters:

where represents the loss computed on the original sample and denotes the loss computed on the adversarial sample. This combined loss function ensures that the model simultaneously learns to make correct predictions on both normal and adversarially perturbed inputs.

FGSM adversarial training constitutes an effective method for improving model robustness. By generating adversarial samples and incorporating them into the training data, this approach enhances the model’s ability to adapt to input perturbations, enabling the model to maintain performance when confronted with adversarial examples during inference.

4.2. Adversarial Training for Sample Selection

This method combines the principles of active learning and adversarial training to enhance model stability and performance. The specific process unfolds as follows:

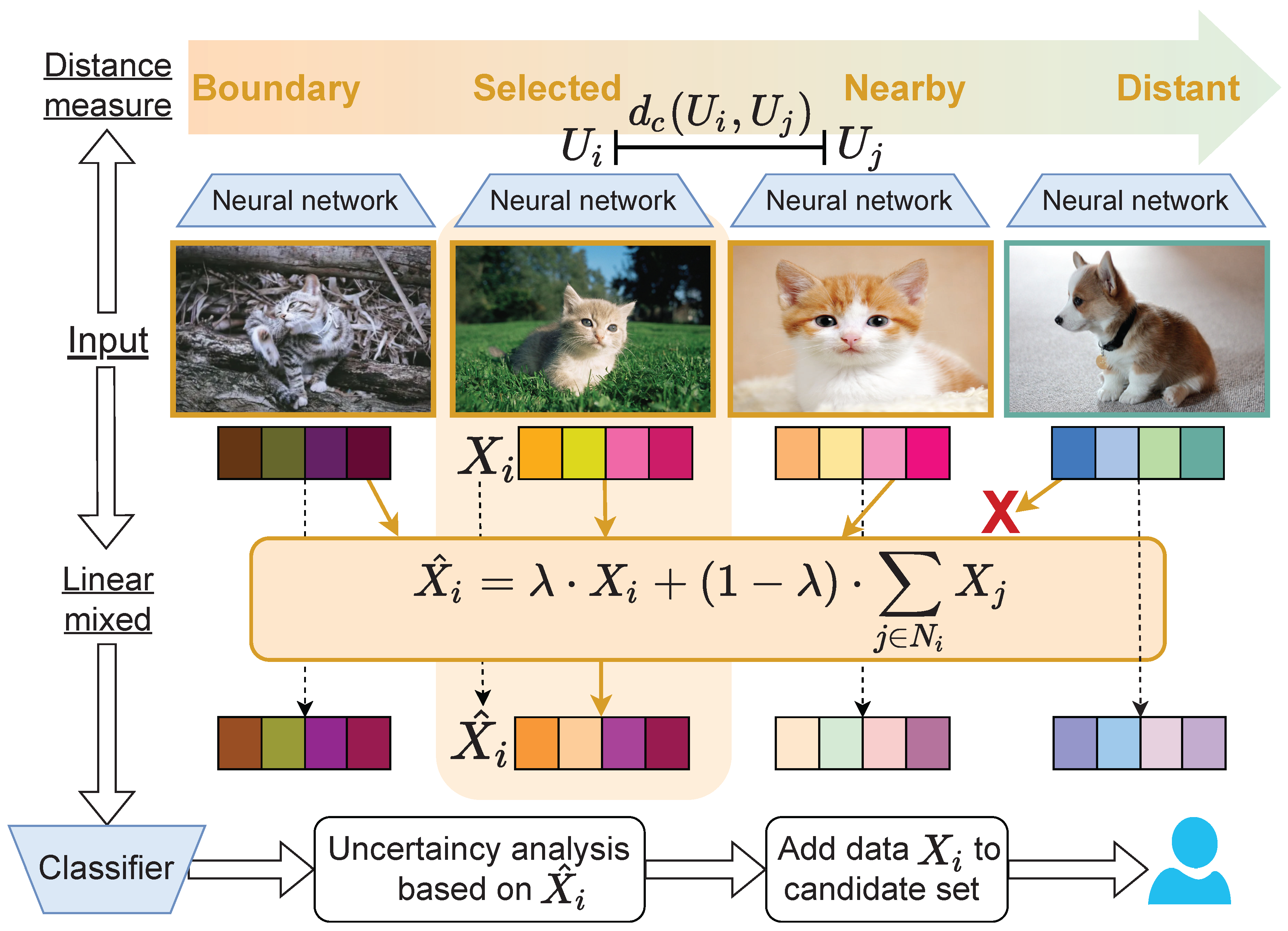

Initially, the trained model performs forward propagation to obtain feature representations from the final layer for each sample, as expressed in Equation . This process effectively represents the information contained within samples as high-dimensional feature vectors. Subsequently, the most representative samples are selected through similarity calculations between samples. We employ a combination of Manhattan and Euclidean distances to produce a more reliable and efficient distance measure, as demonstrated in Equation . This combination leverages the strengths of both distance metrics to achieve more stable similarity calculations, particularly when handling features with varying scales.

Through inter-sample similarity calculations, we identify the most similar batch of samples for subsequent fusion and training. The n most similar samples are then merged using the MixUp fusion method, where samples are linearly combined to generate new training instances that enhance model generalization capability, as shown in Equation . Classification confidence is obtained by evaluating the model, and the corresponding index list is returned for active learning selection.

Following sample selection by the boundary data feature fusion algorithm, the original images undergo forward propagation through the neural network. Prediction results are obtained via the fully connected layer, yielding probability distributions as outputs. FGSM then calculates the gradient of the loss function with respect to the input image through backpropagation. This gradient indicates each pixel’s contribution to the loss function, revealing how individual pixels should be modified during the perturbation process to maximize the loss. Larger gradient magnitudes indicate greater pixel impact on the loss function.

Finally, the perturbation is computed and adversarial samples are generated according to:

In this formulation, represents the perturbation step size, denotes the gradient of the loss function with respect to input sample x, is the model’s loss function, and is the sign function. The parameter determines the magnitude of the adversarial perturbation, with larger values producing more pronounced perturbations. For simpler tasks such as MNIST or SVHN, a smaller value of is typically chosen. For more complex tasks like CIFAR-10, a larger value of is selected to enable the model to handle more substantial perturbations. The greater the difference between generated adversarial samples and their original counterparts, the more challenging it becomes to train the model for robust performance.

The calculated perturbations are added to the original samples to generate adversarial samples:

where

H represents the adversarial sample resulting from adding the perturbation

to the original input

x.

|

Algorithm 2 Distance-Measured Data Mixing with Adersarial Training |

- 1:

Inputs: unlabeled pool U, labeled pool L, model , loss , batch B, group size n, Beta(), step , epochs E - 2:

while not converged do

- 3:

Extract final-layer features for all

- 4:

For each , compute mixed distances s(x,x’) using L1+L2; get top-n neighbors

- 5:

Build fused set S via MixUp on pairs from with

- 6:

Score S by model confidence; select B lowest-confidence indices Q - 7:

for each do

- 8:

compute

- 9:

compute ,

- 10:

end for

- 11:

Acquire labels for ; update

- 12:

for epoch = 1 to E do

- 13:

for mini-batch from L with paired if present do

- 14:

; update

- 15:

end for

- 16:

end for

- 17:

Remove labeled items from U; refresh features as needed - 18:

end while - 19:

Return

|

The proposed method integrates active learning with adversarial training to improve robustness and efficiency in boundary-focused sample selection. In each iteration, the model first extracts final-layer features for all unlabeled samples and computes pairwise similarities using a hybrid of L1 and L2 distances to identify top-n neighbors per seed sample. Candidate training instances are then synthesized via MixUp over seed–neighbor pairs, and the model’s confidence on these fused samples is evaluated to select a batch of the most uncertain (near-boundary) examples. For each selected instance, FGSM is applied to generate an adversarial counterpart by taking the sign of the input gradient, scaling by a perturbation step, and adding it to the input. The original fused samples and their adversarial variants are labeled and added to the labeled pool.

Model updates combine natural and adversarial losses with equal weight in mini-batch training over several epochs, promoting accurate predictions on both clean and perturbed inputs. By repeatedly selecting uncertain, feature-near-boundary samples constructed via MixUp and augmenting them with FGSM adversaries, the algorithm reduces labeling requirements while enhancing robustness against noise and perturbations.