1. Introduction

Achieving the net-zero emission target by mid-century requires a paradigm shift in the energy sector and radical decarbonisation. The transition towards low-carbon emission energy systems has accelerated the integration of large-scale renewable energy sources (RES), such as solar PV and wind, into the power system. The accelerated integration of renewable energy sources (RES) is displacing traditional power generation by synchronous generators. While RES are critical to decarbonization, their inherent intermittency significantly challenges power system reliability and flexibility [

1]. In addition, the phasing out of synchronous generation is causing low system strength due to low inertia, further degrading power system stability. Due to the low system inertia, frequency stability is emerging as a more dominant issue in high RES power grids [

2]. One solution to mitigate this issue is to ensure that adequate frequency control ancillary services (FCAS) are provided. Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) are considered a good energy source to maintain supply and demand, mitigate intermittency, and ensure grid stability. BESS can provide fast and precise responses, making it an ideal candidate for FCAS services [

3]. With the advancement of technologies, BESS offers a wide range of energy storage solutions, enabling frequency regulation, voltage support, energy arbitrage, peak shaving, and smoothing ancillary services that support the grid with higher penetration of RES [

3,

4,

5,

15].

Despite BESS’s technical capabilities to provide frequency response in seconds, many electricity markets lack clarity on the role of BESS in the ancillary markets [

15]. The market rules are predominantly designed for thermal generation, with minimum durations, response rates, and ramp rates that are suitable for traditional generating units [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Furthermore, while BESS provides FCAS, frequent cycling and high-power discharges accelerate battery degradation [

11,

12]. Without proper degradation-aware control strategies and compensation, BESS operators may face challenges of accelerated degradation and reach the end of life (EOL) much sooner, resulting in a financial loss. The primary contribution of this paper is to provide a comprehensive overview of global energy markets and a critical analysis of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) participation in Frequency Control Ancillary Services (FCAS) markets.

1.1. Contribution of This Paper

Understanding the rapid changes in the energy market and emerging technical challenges has become imperative. This review synthesises the current state of knowledge on the evolution of the energy market, the role of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) in providing grid stability, particularly frequency control services, with a focus on their integration into evolving high-renewable energy (RES) market structures. While much of the existing literature has focused on the technical aspects of battery storage, this review goes a step further by connecting these technologies to real-world market dynamics and policy developments. It brings together insights from engineering, economics, and regulation to highlight the role of BESS in grid stability and flexibility, as well as the challenges that BESS face in evolving electricity markets.

2. Energy Market Overview

Globally, the energy market is undergoing a drastic transformation. The projections show a significant increase in global electricity demand, estimated at 16,885 GW by 2030, up 39% from 2020, and increasing further to 30,227 GW by 2050, equating to a 166% increase from 2020. The higher penetration of RES, primarily the generation of wind and solar photovoltaics (PV), has also accelerated the modernisation of power systems. In the next few decades, the integration of RES is expected to grow significantly. A recent study suggests that RES achieved a major milestone in 2023, when RES exceeded 30% of global electricity generation for the first time [

14]. This showed a steady increase in 2% RES from 27% in 2019 to 29% in 2020 [

18,

19]. The years 2020 to 2024 show a notable increase in RES, with installed capacity growing by about 117%, rising from 270.1 GW in 2020 to 585.2 GW in 2024 (

Table 1). This growth accounts for 46% of the global power capacity by the end of 2024 [

16]. Notably, supportive policies and the decline in the costs of renewable technologies are the main driver of growth. By 2030, RES capacity is projected to be 10,300 GW, representing 61% of the installed capacity worldwide, and projected to reach 26,600 GW by 2050 (

Table 2), accounting for 88% of total installed capacity[

17].

2.1. Solar PV and Wind

Solar PV technology demonstrated the most rapid expansion among all technologies, achieving a 245% increase in installed capacity between 2020 and 2024, while wind energy remained stable throughout this time frame (

Table 1). Studies suggest that the rapid development of RES is driven by lowering technological costs, commitments to net-zero, increased investment in major global energy markets, including China, the European Union, the United States, and geopolitical uncertainty in fuel and energy supply [

17,

20,

22]. A recent report from IRENA [

16] claimed that current growth is geographically concentrated in China, the European Union and the United States, which account for 489 GW (83.6%) of renewable capacity installed in 2024.

Recently, at the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP28, 130 countries pledged to accelerate the energy transition and committed to triple the RES with an installed capacity of at least 11,000 GW by 2030 [

23]. The tripling RES goal aligns with the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C [

24]. Despite the challenges, recent forecasts (

Table 2) predict that by 2050, approximately 90% of electricity generation could come from RES, with around 61% supplied by solar PV and wind [

17,

21].

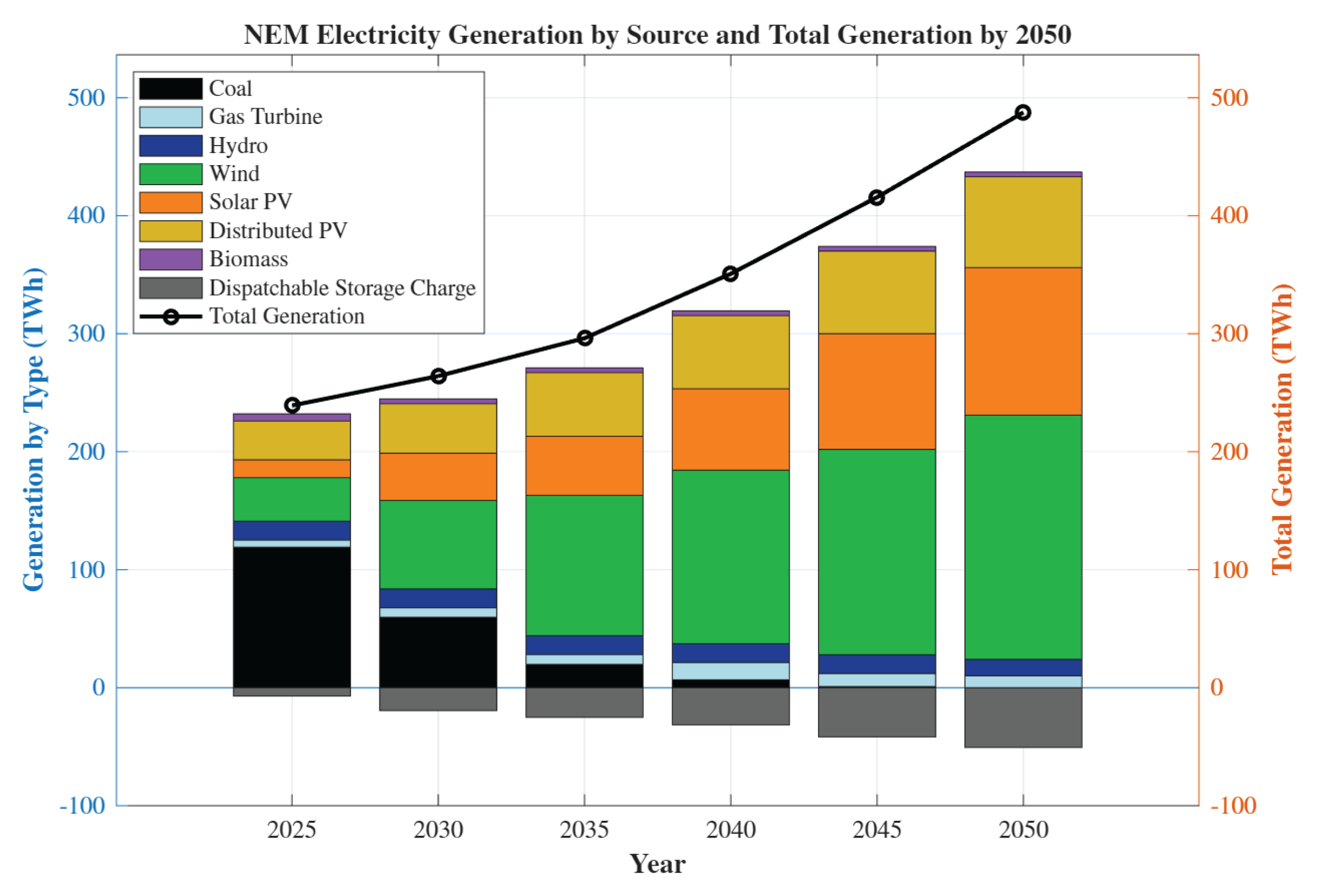

In Australia, a CSIRO forecast (

Figure 1) indicates that the transformation of the National Electricity Market (NEM) follows global trends, and it is expected that total generation will increase from 225 TWh in 2025 to 439 TWh in 2050, an increase of 95%. Study have shown rapid growth in RES, particularly solar PV with an increase of 200% and wind by an increase of 113% by 2050, making it 64% variable energy source by 2030 and 95% by 2050, predominantly solar PV and wind. The CSIRO forecast projects an exponential growth in dispatchable storage from 10 TWh in 2025 to 75 TWh by 2050, with an increase in capacity 650%. The BESS growth also follows the RES trends, and the expected dispatchable electricity storage capacity by 6.3 GW in 2023 and 44- 96 GW/550-950 GWh, respectively by 2050 [

15,

42,

44].

The synthesis of the studies and recent data presented above supports the conclusion that RES is growing rapidly. Specifically, solar PV and wind energy are emerging as the main drivers of RES expansion, accounting for approximately 61% of the global market share. This substantial integration of variable RES technologies is progressively displacing conventional synchronous generation, leading to a reduction in overall system inertia. As a result, the decline in system inertia poses a significant challenge to the stability and security of power systems.

2.2. Battery Energy Storage System (BESS)

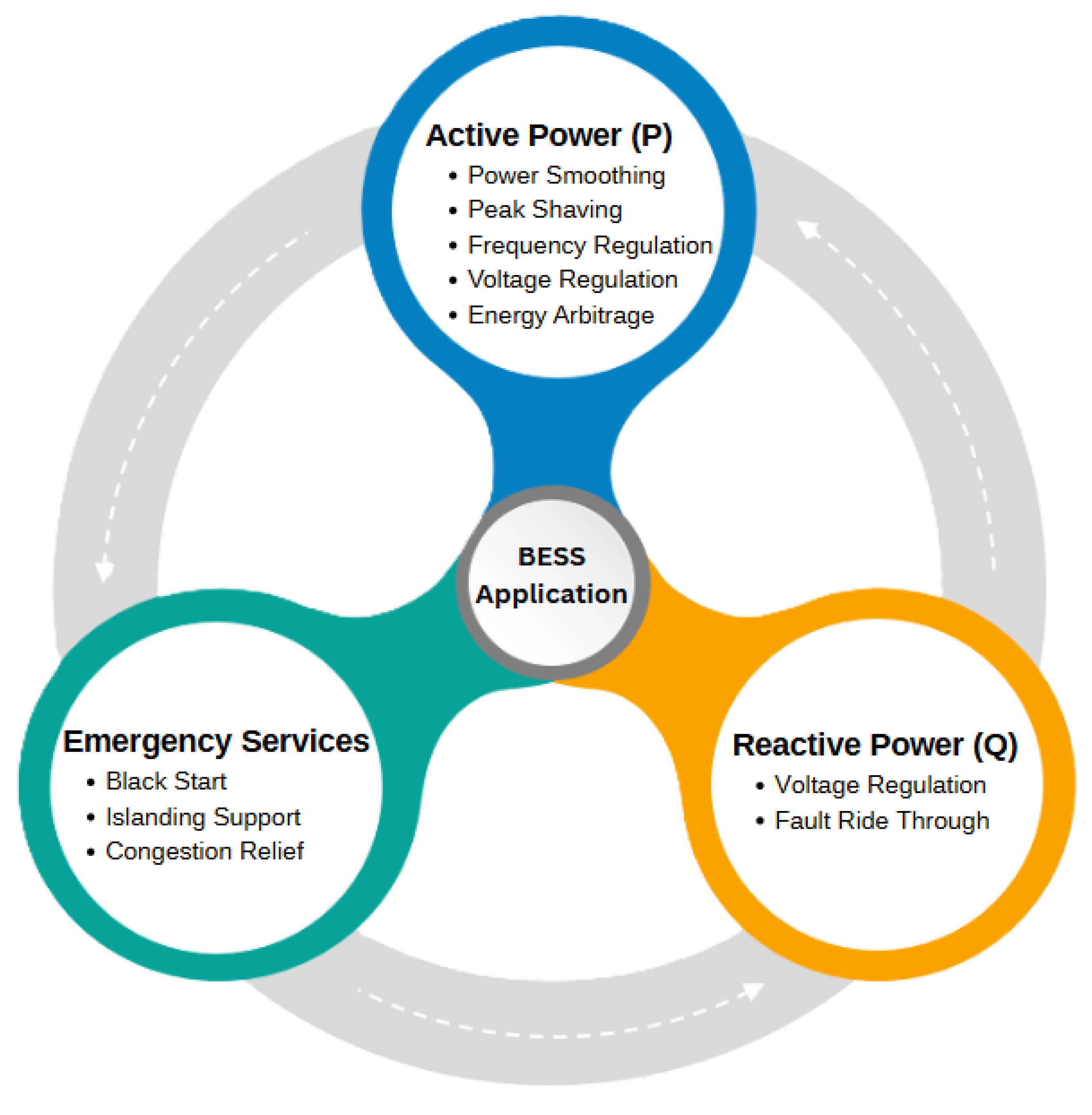

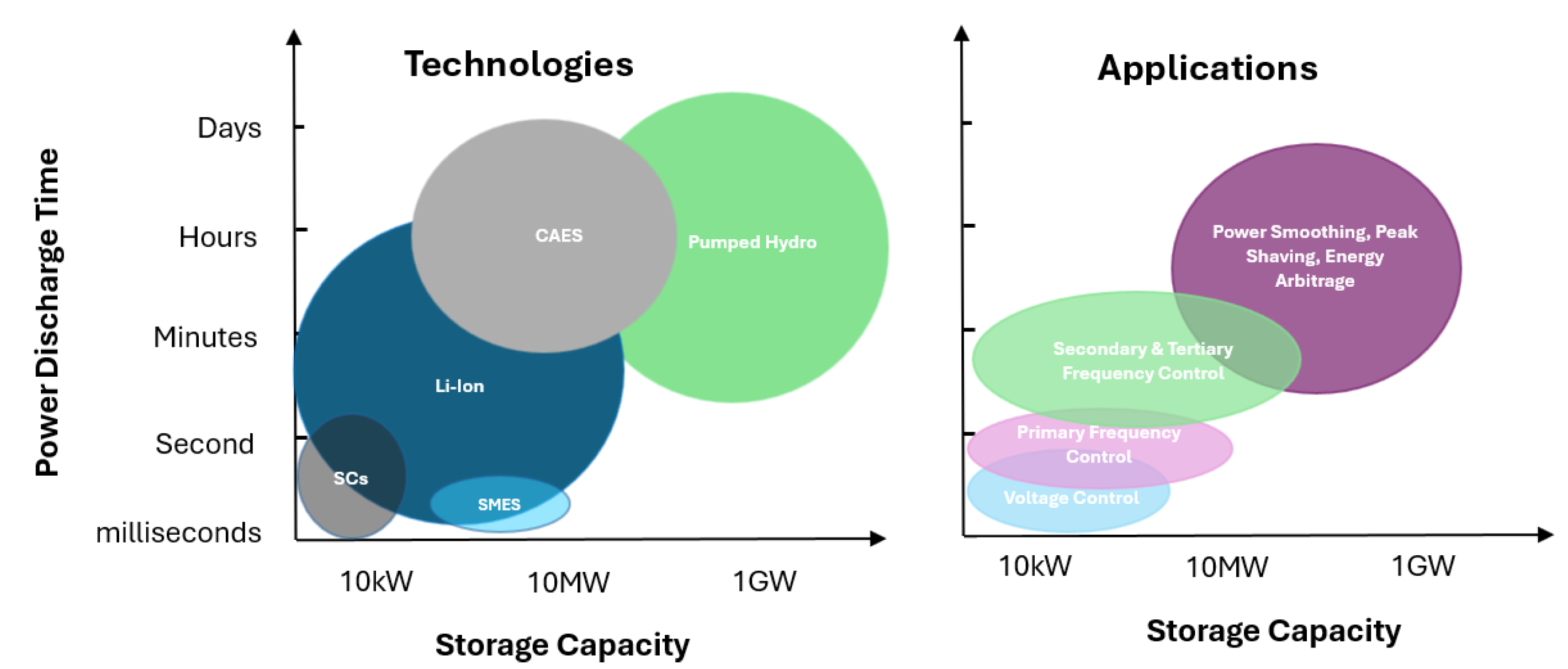

In recent years, technological advancements have positioned the Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) as a viable solution to address emerging security risks of the system. Research on electricity storage technologies has underscored the critical role of BESS in grid applications [

25]. Compared to alternative technologies, BESS offers greater flexibility in storage capacity, scalability, and rapid response capabilities, making it an effective solution to enhance grid stability. BESS provides voltage and frequency control, load follow, Black Start capability, deferral of power line upgrades, and other vital services (

Figure 2).

In recent years, the deployment of BESS has experienced exponential growth. Global BESS additions surged in 2023 and 2024, reaching a cumulative capacity of approximately 150 GW / 363 GWh by the end of 2024 [

26]. Recent research suggests that China, the United States, Europe, and Australia are emerging as key growth drivers in the global battery energy storage system (BESS) market [

15]. In 2023, the global BESS capacity saw significant growth, with China added 23 GW, the United States 8 GW, Europe 6 GW, and Australia 1.3 GW. [

15].

Table 3.

Global & Key Regional BESS Installed Capacity Additions (GW/GWh), 2023-2024.

Table 3.

Global & Key Regional BESS Installed Capacity Additions (GW/GWh), 2023-2024.

| Region |

Year |

Added Capacity (GW) |

Added Capacity (GWh) |

Cumulative Capacity End-2024 (GW/GWh) |

Sources |

| Global |

2023 |

42-45 |

90-97 |

90-97/190 |

[15,31,32] |

| Global |

2024 |

150 |

363 |

150/363 |

[26] |

| China |

2024 |

36-42 |

101-107 |

74/168 |

[27,28] |

| USA |

2024 |

10.4 |

28 |

26/72 |

[28,33] |

| Europe |

2024 |

11.9 |

22.4 |

35/58.3 |

[30,34] |

| Australia |

2024 |

2 |

4 |

5/11 |

[27,35] |

The IEA Net Zero Emission by 2050 (NZE) scenario reported strong growth in BESS and suggested that 1,200-1,500 GW of storage may be required by 2030. This growth is expected to be 8-fold by 2050 from the estimated installed capacity of 150 GW of BESS in 2024. The BESS capacity project under various scenarios, shown in

Table 4. Technological advancement and a steep decline in manufacturing costs, i.e., from USD

$2,511/kW in 2010 to USD

$274/kW in 2023, have contributed to the rapid expansion of battery energy storage systems (BESS) [

21,

43].

The outlook for the growth of the battery energy storage system (BESS) is increasingly promising, driven by a combination of strong policy support, growing market interest, commitments to net-zero emissions, and rapid technological advancements. Ambitious scenarios, such as the IEA Net Zero Emissions (NZE) pathway, highlight the crucial role storage could play in building a cleaner and more resilient energy system. Even conservative projections like the IEA’s STEPS forecast indicate consistent growth aligned with the current trend.

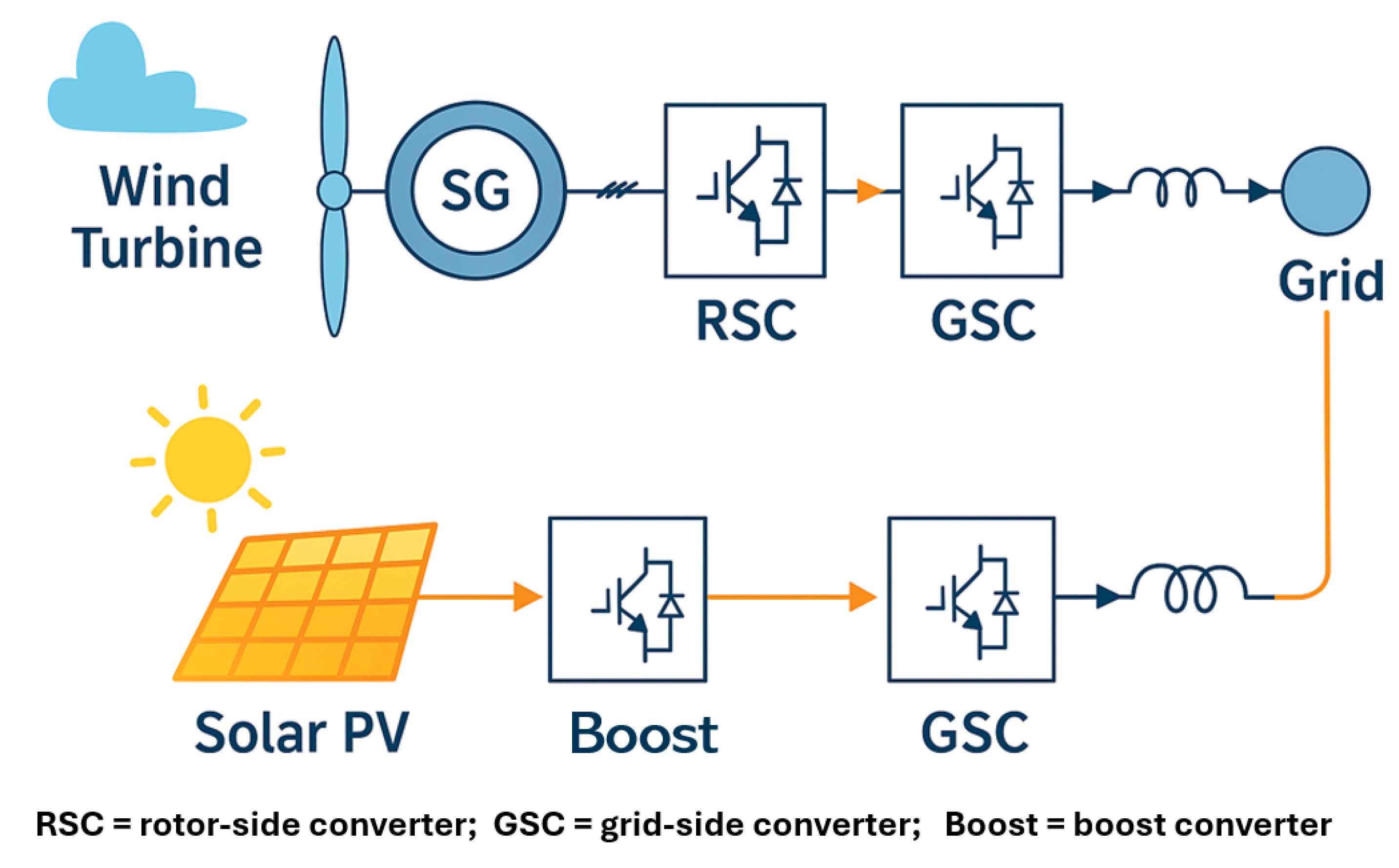

3. High RES Impact on Power System Frequency

The primary concern is the reduction of system inertia, which is critical to maintaining grid stability during disturbance events [

44]. RESs are inverter-based resources (IBRs), which are not directly connected to the power grid, but are behind converters and decouple the RESs from the power systems (

Figure 3). This decoupling reduces the natural support provided by the kinetic energy stored in the form of inertia and weakens the power system [

63,

64,

65]. In addition, solar photovoltaic systems do not have a rotating mass and do not provide inertia support. The weak grid with low system inertia introduces a higher rate of change of frequency (RoCoF), lower frequency nadir (the minimum level the frequency reached after a disturbance event) and weakens the damping performance, making grids more susceptible to frequency fluctuations [

66]. The RoCoF (Hz/s) reflects the speed with which the system frequency changes following a disturbance event and indicates the strength of the system. The aggressive RoCoF may not provide sufficient time for under-frequency load shed (UFLS) schemes to operate and poses a risk of system blackouts [

67].

In low-inertia systems, following a disconnection of loads/generators, the RoCoF increases rapidly [

56,

65,

66,

67]. The RoCoF is the time derivative of the power system frequency (df/dt). The average RoCoF for N synchronous generators and loads are computed using the equation below:

Where

is a frequency deviation from the initial frequency

at time

just a moment after the disconnection of loads/generation

. The

and

are the inertia constant and the apparent power of the synchronous generator unit

i, with

i ranging from 1 to

N[

56]. Haque et al.[

67] investigated the frequency stability at 10%, 20%, 30% and 40% of RES integration into the power system and concluded that the frequency nadir

(Hz) decreases and RoCoF increases with an increase in RES. A similar investigation was conducted by Saleem and Saha [

65] at 0%, 10%, 30%, 50% and 70% RES, and concluded that with an increase in RES, the

decreased and RoCoF increased significantly. Wind and solar energy inherently depend on environmental conditions and exhibit significant intermittency, variability and uncertainty. This intermittent and variable nature of RES introduces operational risk to the power system security and causes frequency, voltage and ramp rate stability issues [

43]. As an example, wind gusts cause rapid fluctuations in power generation and ramp rate. Similarly, cloud cover and irradiation intensity are the primary causes of power generation and ramp rate fluctuations in solar PV generation [

71]. Power generation variability and ramp rate fluctuations cause frequency deviations in power systems. The system frequency deviation is determined by taking into account the dynamic effects of loads and generations, including inertia, primary, and secondary control [

72]. The system frequency deviation is as follows:

In the above equations, means the Area Control Error, means initial wind power change, means generated power from wind-generating systems, is the initial solar power change, means generated power from Solar PV systems, means power generated by turbines, is the virtual inertia constant, is the virtual damping constant, is the time constant of the inverter-based ESS, and means virtual inertia power. The and are industrial and residential loads, respectively.

Equations (2), (6), and (7) support the notion that active power variation (

and/or

) due to environmental factors such as irradiation and wind influences grid frequency. A recent investigation by Buch [

68] has demonstrated that solar photovoltaic (PV) systems exhibit significant variations in power generation due to changes in irradiation under cloudy conditions. Similarly, a study by Yan et al. [

69] concluded that fluctuations in irradiation lead to rapid changes in ramp rate, which consequently affect power output and system frequency. Liu et al. [

70] investigated the effects of wind fluctuation and its impact on power system security, concluding that wind fluctuations greatly influence power output.

The increasing integration of renewable energy sources (RES) represents a critical advancement toward achieving net zero emission targets. However, with increasing RES, the system inertia is expected to reduce significantly. This will increase the rate of change of frequency (RoCoF) in power systems, thereby elevating the risk to power system stability and reliability. In this context, Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) are becoming a viable and effective solution for addressing RES intermittency, thereby promoting grid stability, enhancing system reliability, and enabling the increased deployment of low-carbon energy technologies.

4. BESS Role in Modern Power Systems

BESS is playing a critical role in modern power systems with a high integration of RES. BESS provides active power support through power smoothing when coupled with solar PV and wind generation. It also offers power levelling during low and high demand periods and peak shaving during high demand periods. In addition, BESS contributes to voltage and frequency regulation. BESS also provides reactive power support and helps regulate power system voltage, as well as fault ride-through capabilities [

3,

45]. Grid-forming inverter technology positions BESS as an ideal solution for delivering emergency services such as black start capability, islanding grid support, and congestion relief. Due to the intermittent nature of RES, voltage and frequency control have become a challenge for utilities. This problem is worsening with increasing RES and decreasing system inertia [

46]. This is a well-recognised issue that necessitates a better approach to managing safe and reliable grid operation.

Globally, grid frequency is managed through various mechanisms, including frequency control services and mandatory frequency support. The frequency regulation market design varies with markets and network conditions. The section below summarises the frequency control services in different global markets and their characteristics.

4.1. Frequency Control Ancillary Services (FCAS)

Historically, grid stability, particularly frequency stability, has been supported by the inherent physical property of inertia provided by large, rotating synchronous generators (e.g., thermal, hydro). The kinetic energy stored in these rotating masses naturally resists changes in system frequency, slowing down the rate at which frequency deviates (Rate of Change of Frequency, RoCoF) following a disturbance, such as the sudden loss of a large generator or load. As the RES are asynchronous generation and typically behind the inverters, the inertial support from the RES is limited [

48,

49]. Transmission System Operators (TSO) or Independent System Operators (ISO) procure grid support services commonly known as Ancillary Services to regulate grid frequency within the acceptable range. Among the most critical services are the Frequency Control Ancillary Services (FCAS) in the National Electricity Market (NEM), the Frequency Co-Optimised Essential System Services (FCESS) in the Wholesale Electricity Market (WEM), and Frequency Response Services, Balancing Services and Frequency Containment Reserve (ENTSOE), particularly within European electricity markets [

8,

50,

51,

52,

53].

Several studies have explored the various frequency control services across major electricity markets and suggest that frequency control is typically achieved through a layered approach, involving different types of responses acting over various timescales following a frequency disturbance [

54]. These layers work collaboratively to arrest the initial frequency deviation, stabilise the frequency of the system, restore it to its nominal value, and restore the reserves utilised [

47]. Typically, the response is required when grid frequency operates outside the defined deadbands (

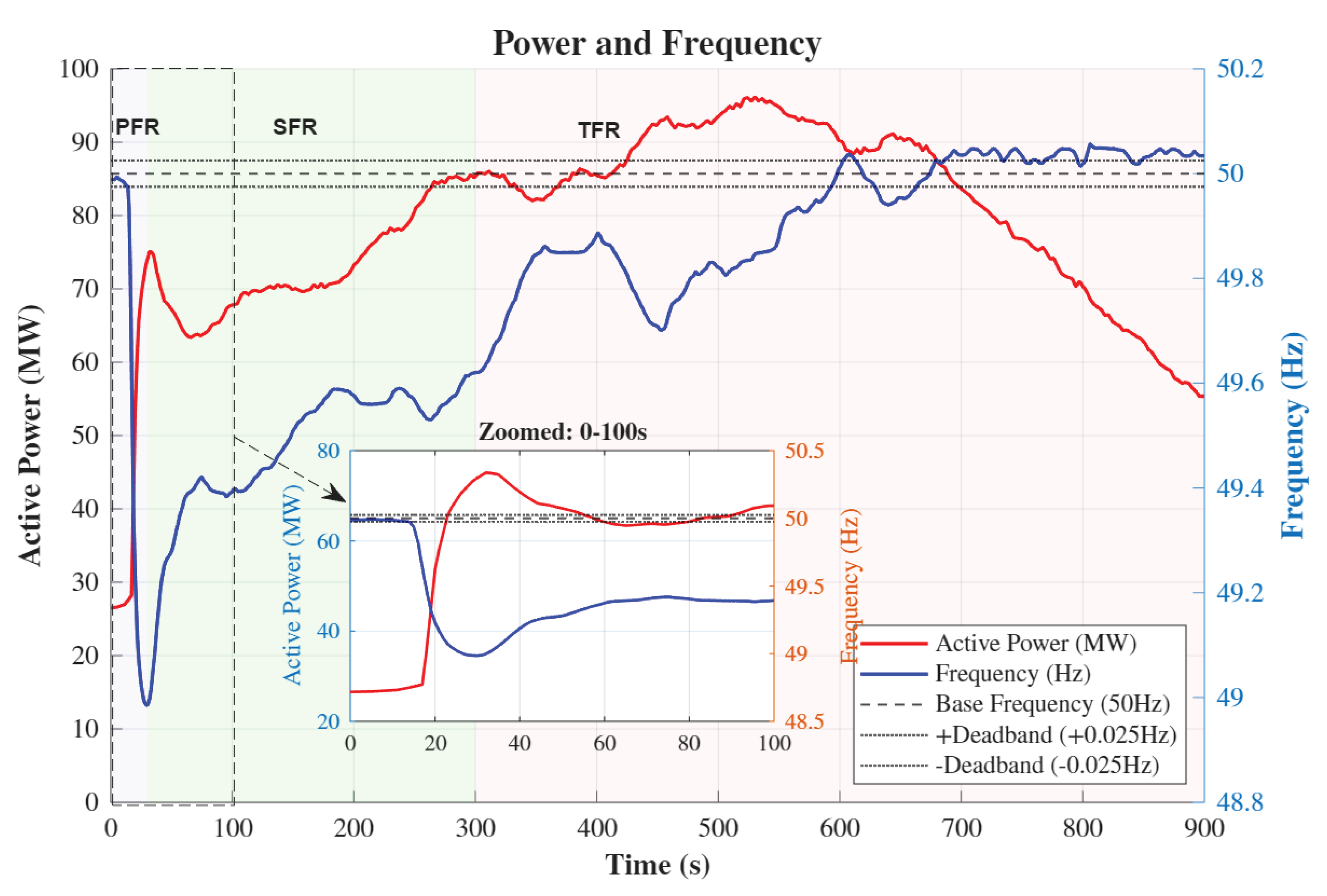

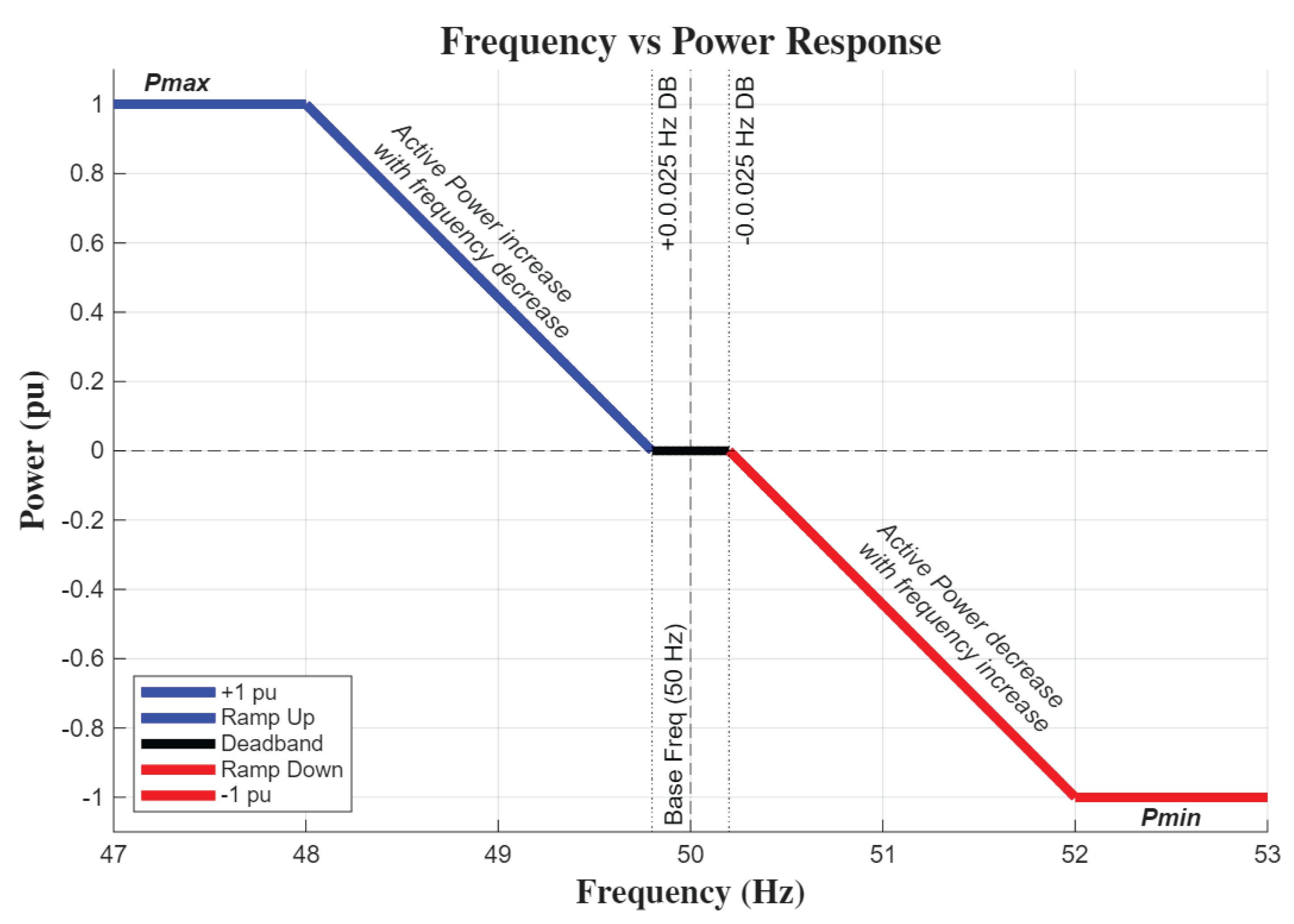

Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Fundamental frequency control principle [

47].

Figure 5.

Fundamental frequency control principle [

47].

Figure 6.

Primary Frequency Regulation in 50Hz markets.

Figure 6.

Primary Frequency Regulation in 50Hz markets.

The commonly known frequency responses are the following.

4.1.1. Inertial Response

This is the near-instantaneous (sub-second) response inherent in the physics of synchronous machines (

Figure 5). When frequency changes, the kinetic energy stored in their rotating mass is naturally released (during events of low frequency) or absorbed (during events of high frequency), counteracting the change [

56]. However, BESS does not have any rotating mass and cannot provide inertia support. With technological advancements, BESS with grid-forming inverters (GFM) can provide synthetic inertia by mimicking the active power response proportional to RoCoF [

103].

4.1.2. Fast Frequency Response (FFR)

Fast frequency response services require an injection or rejection of active power (MW) in a couple of seconds to maintain grid stability [

6,

57,

58]. FFR responds to frequency excursions much faster than conventional generators and is the first responder after the inertia response. AEMC presents a comprehensive study on this subject, highlighting the close interaction between FFR services and the response to inertia [

57]. The study identifies the challenge of differentiating FFR from the inertia response during the initial stage of the frequency response and the difficulty in explicitly distinguishing their contributions.

In the Australian electricity market, the Fast Frequency Response (FFR) provision must be activated within one second of a frequency disturbance event[

8,

57]. The United Kingdom market also has a similar response requirement, with the addition of sustained response for an additional 15 minutes [

52]. In contrast, in the US and Canadian markets, the service is called Inertial Control and requires a full response in 0-12 seconds, offering flexibility. Due to its rapid response capabilities, BESS can deliver FFR in 1-2 seconds. However, this rapid power alteration at a very high C-rate might induce a high current in the BESS, leading to a quick temperature increase and accelerated battery degradation.

4.1.3. Primary Frequency Response (PFR)

This is the first active control response, typically activated within seconds of a frequency deviation, typically within 30 seconds, as shown in

Figure 5, [

59]. PFR or Frequency Containment Reserve (FCR) resources independently adjust their power output in proportion to the magnitude of the frequency deviation based on the droop settings. The primary goal of the PFR is to arrest frequency fall or rise outside of the predefined frequency deadbands. This response is generally sustained for several minutes until slower acting reserves, typically secondary frequency response (SFR), can take over [

8].

The PFR response requirements in the Australian and UK markets are similar but differ slightly in their support for the response. There are no sustained response requirements in the National Electricity Market (NEM), but the Wholesale Market (WEM) on the West Coast of Australia requires sustained response for 15 minutes. In contrast, the UK market requires a sustained response of 20 seconds. Similar to FFR, the PFR response is required within a short timeframe, resulting in higher C-rate charge or discharge cycles for BESS. In BESS during PFR, a high C-rate with a deep depth of discharge (DoD) leads to rapid temperature rises, resulting in capacity and power degradation.

4.1.4. Secondary Frequency Response (SFR)

Following the initial containment by PFR/FCR, SFR/aFRR is activated to restore the system frequency to its nominal value. The SFR response is typically slow compared to FFR and PFR, typically 30 seconds to a few minutes. The SFR/aFRR response is typically remotely controlled by the TSO/ISO, which sends automated signals (usually through automatic generation control (AGC) systems) to participating generating units, instructing them to adjust their power output [

60]. The activation time for SFR/aFRR is slower than that of PFR/FCR, ranging from tens of seconds to several minutes. In Europe, this is known as aFRR. Markets like PJM differentiate within this category, offering signals such as RegD (dynamic regulation) tailored for faster and more precise adjustments, alongside traditional regulation signals (RegA). Similarly, CAISO procures the Regulation Up and Regulation Down services. BESS performance within SFR offers better safety compared to FFR and PFR, primarily due to its regulated charge-discharge rates and moderate temperature rise, which result in less battery wear and an extended BESS lifespan.

4.1.5. Tertiary Frequency Response (TFR)

The TFR services are executed to manage ongoing current and future contingencies. This is the slowest response frequency regulation service, typically activated manually by grid operators over minutes to hours. TFR/mFRR involves adjusting the dispatch of generation units (or large loads) using SCADA to fully restore the balance between generation and load in the longer term, replenish the faster-acting reserves (PFR/FCR and SFR/aFRR), and manage anticipated changes or persistent imbalances. In the TFR market, BESS undergoes frequent minor charge and discharge cycles. The long-term impact of repeated charging and discharging in micro- and mini-cycles has not been sufficiently studied and warrants further research.

4.2. Regulatory Requirements: Grid code, Generator Performance Standards

Grid codes, also known as Generator Performance Standard (GPS) in some energy markets, are comprehensive technical documents that outline the rules, regulations, operational mandates, and performance benchmarks for power-generating units. In Western Australia, for instance, GPS are formally defined within Chapter 3A and Appendix 12 of the Wholesale Electricity Market (WEM) Rules [

7]. These standards are designed to ensure that each connected generation asset adheres to its operational obligations and specified parameters, thus mitigating risks such as cascading failures and maintaining voltage and frequency within acceptable limits [

53]. The current market rules are generic in nature and do not distinguish between traditional generators and Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS).

To regulate frequency, generating units such as BESS must supply and sustain active power output according to the specified droop setting. The droop sets the rate of the active power response with respect to a frequency change, that is, in WEM, a 5% active power change is required with every 0.1 Hz frequency change, making it a 4% droop response. In some markets, BESS is expected to provide a rapid response, i.e., FFR, PFR, LVRT, HVRT, FDRT, FRT, which causes a rapid charge or discharge of energy into the grid within a short timeframe (

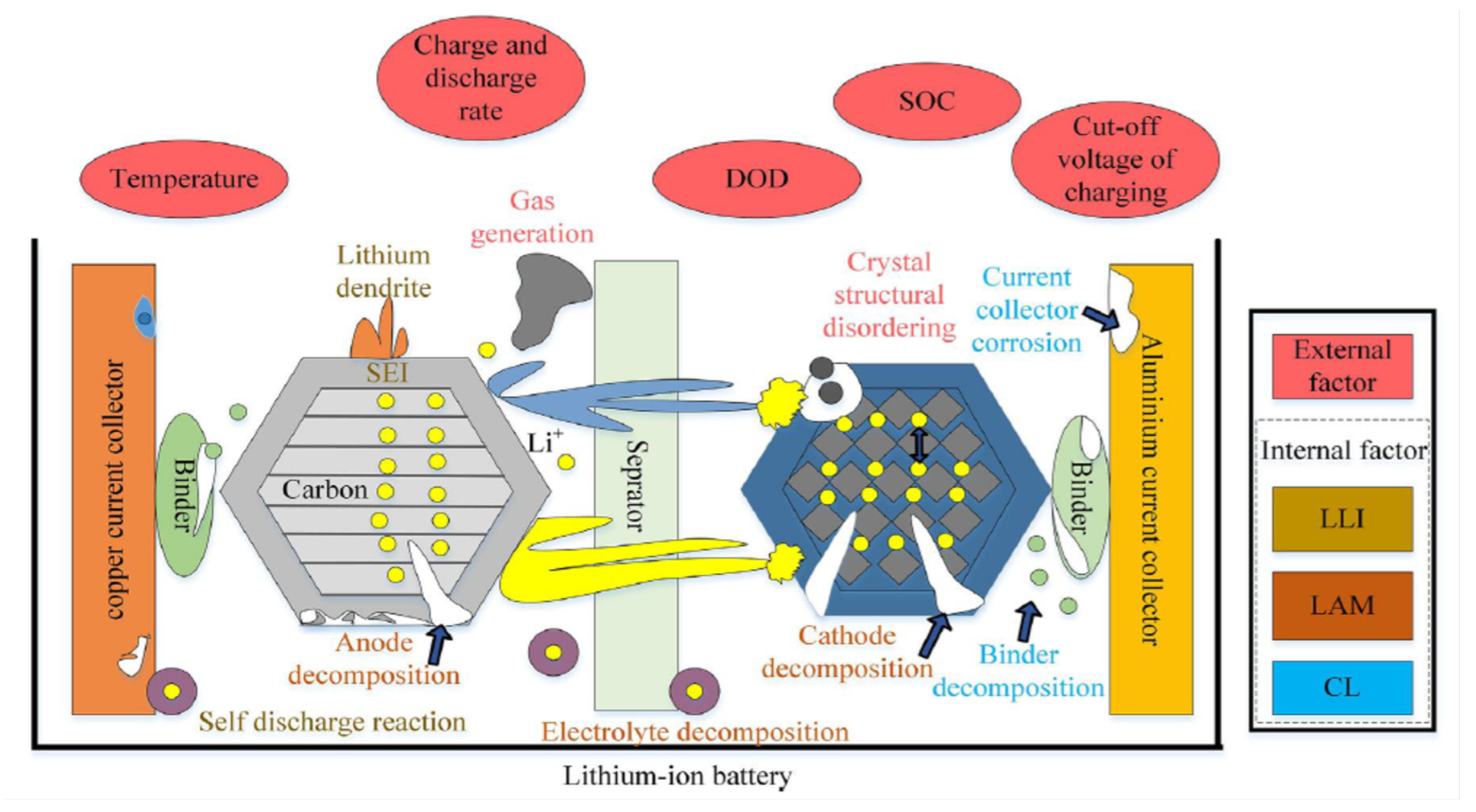

Table 5). This rapid charge and discharge cycle at elevated C-rates increases battery temperature, lithium depletion, and accelerates capacity degradation. Furthermore, BESS has limited stored energy to support the grid during such an event and may not sustain a response beyond a certain level. This causes a lack of visibility and uncertainty in grid stability.

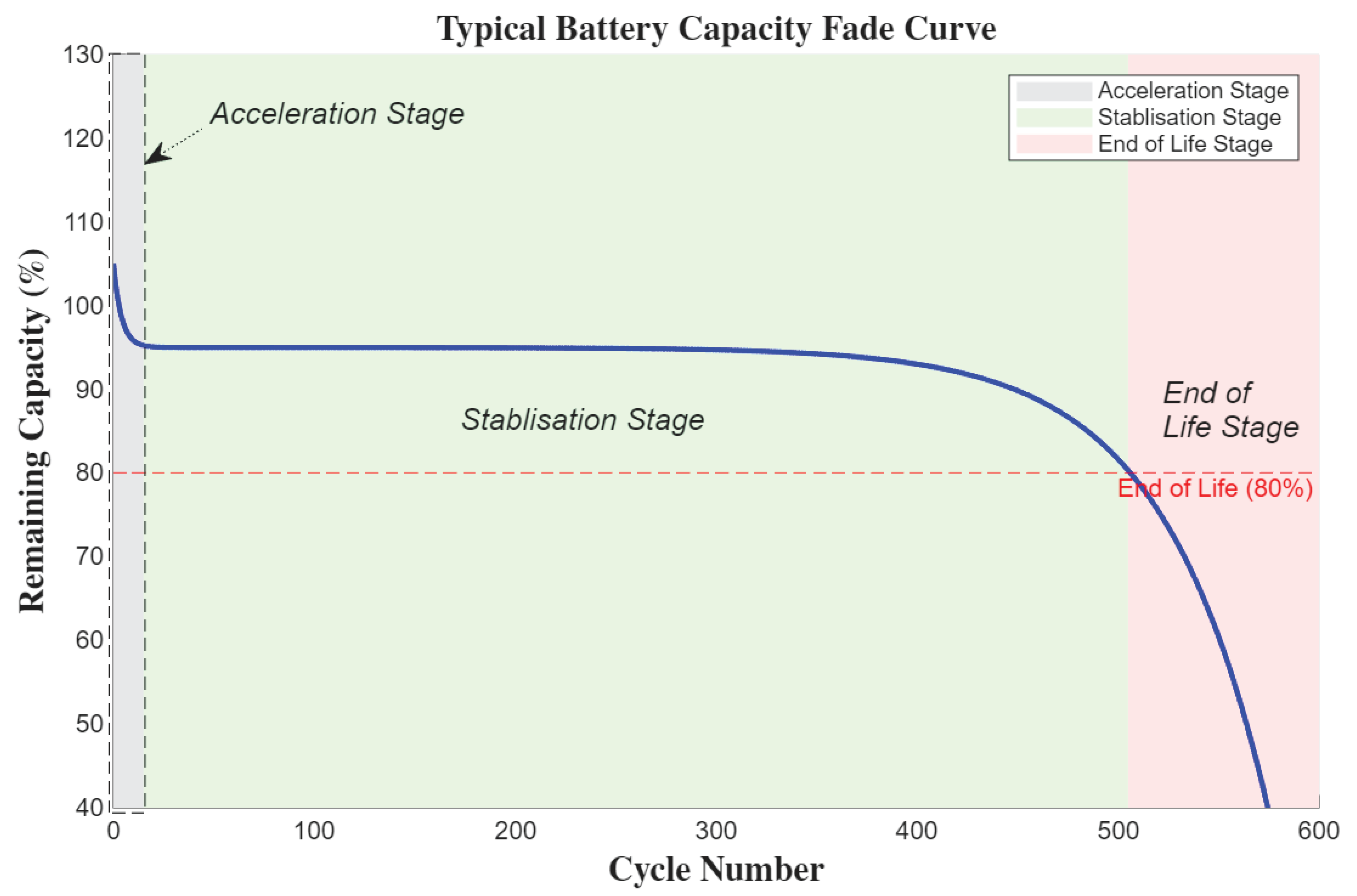

5. FCAS Impact on BESS’s Operational Life

When providing FCAS services, many factors significantly influence the performance of BESS, including the nature of charge/ discharge and the depth of discharge, the temperature and the chemistry of the battery cell. BESS undergoes many micro, mini, partial, and full charge and discharge cycles throughout its lifecycle [

73,

74,

75]. Under these dynamic conditions, predicting the remaining useful life (RUL), typically 70-80% of full capacity of BESS [

83,

84], is a significant challenge that substantially impacts its reliability and process safety.

Evidence from previous studies suggests that BESS can provide a fast and flexible response, making it a suitable candidate for FCAS. However, there is a lack of clarity on power and capacity degradation, failure modes, and appropriate control measures to manage the emerging risk of BESS failure.

There are three stages in battery capacity degradation shown in

Figure 7. The first stage, the acceleration stage, is believed to be caused by the formation of the initial solid electrolyte interphase layer (SEI), which causes a rapid increase in the internal resistance of the battery and, consequently, a rapid decrease in capacity [

76]. The second stage is the stabilisation stage, also known as Useful Life or Linear Aging, where the battery operates under normal conditions, providing energy and FCAS support. This stage is more useful, stable, and predictable in terms of the BESS response [

76,

77]. The third and final stage is the saturation stage, also known as non-linear aging. This stage occurs predominantly due to the loss of lithium, acid dissolution, or the higher internal resistance of the batteries. Batteries are considered unsafe to operate once they reach this stage. The point where the saturation stage starts, also known as the knee point, is considered the End of Life (EOL) of a battery [

76,

77,

78].

Battery performance deteriorates sharply beyond the knee point, and the failure rate increases significantly. Therefore, manufacturers recommend stopping the operation when the knee point is reached or when the saturation stage is reached. To manage BESS effectively in FCAS and energy markets, several control strategies are deployed in grid-connected BESS. The next section discusses the commonly used control strategies.

5.1. Calendar Aging Impact

The aging degradation in BESS is mainly due to variations in ambient temperature. Several studies have investigated the impact of temperature on battery aging. A recent review study by Zhang et al. [

43] investigated factors affecting the life expectancy of a lithium-ion battery and highlighted the importance of temperature on battery life. Zhang, et al. [

43] pointed out that battery performance is ideal at room temperature 25°C, and performance varies if used at higher or lower temperatures. In lithium-ion batteries, low temperature is one of the major contributors to irreversible depletion of lithium ions and dendrite formation [

87]. Similarly, recent studies on the high-temperature impact on batteries discovered that battery aging degradation accelerates at high temperatures, and the major contributing factor to degradation is the growth of Solid Electrolyte Interface (SEI) (Deshpande et al. 2017) [

87]. Guan, et al. [

89] experimental data suggest that at elevated temperatures (45°C ), a thick and unstable layer of SEI forms on the cathode, which contributes to the battery’s higher internal resistance and leads to a battery performance decrease. The study also emphasised that 75% of capacity degradation on the Anode is caused by SEI formation. Recently, Yang, et al. [

90] study revealed that continuous growth of the SEI layer leads to a reduction in anode porosity and presence of lithium-Ion accelerate the reduction of anode porosity and promote lithium plating. Much of the research cited related to aging degradation can apply to BESS when providing FCAS services. Thus, aging degradation is considered linear and is out of the scope of this research. A study by Baghdadi et al. [

98] highlighted that at higher temperatures, calendar aging prevails over total aging.

5.2. Cyclic Aging

Unlike aging degradation, cyclic degradation is more nonlinear and primarily caused by various internal and external factors such as SEI layer growth, lithium plating, mechanical stress on electrodes, electrolyte-electrodes reaction, loss of lithium, thermal effects, electrolyte decomposition particles cracking, dendrites formation, excessive temperature due to rapid charging and discharging and cycling loading [

85,

90].

5.2.1. Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) Formation

The Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) Formation is one of the major causes of Battery performance degradation. The SEI formation process results in lithium-ion loss and, consequently, performance degradation [

91]. This relationship was further supported in a recent study [

76], which suggests that SEI formation interacts with other degradation mechanisms such as lithium plating. The SEI formation continues in both resting and operating modes, accelerating with high temperatures and high current throughputs, which leads to irreversible capacity loss and an increase in internal battery impedance [

92].

During FCAS support, a battery undergoes various magnitudes of depth of discharge (DoD) and energy throughput. This results in elevated temperatures in battery cells, which are directly related to the formation of the SEI and cracking.

5.2.2. Lithium Plating and Loss of Active Material

The lithium plating occurs on the surface of the Negative Electrode (NE) during charging [

93]. The low-temperature operation leads to poor solid diffusivity, which restricts the movement of lithium ions and results in their accumulation on the electrode surface. The factors affecting the lithium plating include fast charging. These findings are closely related to FCAS services, where the response from BESS is expected within a short period. This lithium plating increases the risk of short-circuiting within the cell and is a contributing factor in the loss of cyclable life. Numerous studies have confirmed that lithium plating is an irreversible process and one of the primary reasons for dendrite formation in battery cells [

76,

90,

93].

5.3. Temperature impact

BESS’s temperature is another critical parameter that determines the state of health (SoH) and readiness of the BESS for the FCAS. If the temperature exceeds the permissible level, it can lead to accelerated battery performance degradation and thermal runaway [

94,

95]. The performance degradation of BESS is categorised into two categories, Capacity and Power degradation [

99]. During both charging and discharging, BESS experience heat production because of internal resistance and electrochemical activity. Furthermore, the temperature and reactions within the cell cause the depletion of active materials like Lithium Ion, leading to a reduction in BESS capacity. Ali et al. [

97] examined the behaviour of lithium-ion batteries at temperatures exceeding 40°C and determined that elevated temperatures accelerate chemical degradation processes, such as the dissolution of LiFePO4 particles and thickening of the SEI layer, resulting in increased internal resistance and reduced capacity. The study also highlighted that at higher temperatures, the battery causes the evaporation of electrolyte solvents, which increases the internal pressure and poses safety risks. At higher C-rates during BESS charging and discharging, the internal and surface temperatures of the battery increase, which accelerates battery degradation. Bandhauer et al. [

99] reviewed thermal challenges in Lithium-Ion batteries, noting a reduction in power output with rising internal impedance.

5.3.1. Main causes of heat generation in BESS

There are four fundamental sources of heat generation in BESS: (1) Ohmic losses (Joule heat losses) resulting from the movement of electrons and the internal impedance of the battery, (2) electrochemical reactions, (3) phase changes and (4) mixing effects. Bernardi et al. [

101] propose a comprehensive and general formulation of the energy balance for an electrochemical system, under the assumptions of uniform temperature and negligible pressure effects. The Bernardi et al. [

101] equation can be simplified to::

Where is the rate of heat generated or consumed, M is the mass per unit area of one cell, means specific heat capacity at constant pressure in J/g-K, T is absolute temperature in K.

The equation (

10) is reformulated as follows:

For simplification, the equation (

11) can be rearranged,

Here, V is the cell potential and U is the thermodynamic (open-circuit) potential of a reaction, evaluated at a reference electrode of a given kind. The term (V - U) is a potential drop equivalent to the term IR. Therefore, the equation (

12) can be simplified as follows.

In equation (

13), the first term

represents ohmic loss, which is irreversible heat loss and is directly related to C rates, that is, at a higher C rate, when battery discharge or charge at higher current, the losses

, which result in increased battery temperature. Heat generation varies under different operating conditions, such as State of Charge (SoC). In equation (

13), the second term,

, denotes the entropic heat coefficient. This term reflects the variation in open-circuit voltage, U, as a function of temperature T, related to reversible entropic heat. Liu et al. [

70] examined thermal generation in lithium-ion batteries during charging and discharging, considering several influencing variables. The investigation concluded that heat generation is largely determined by operational factors such as ambient temperature, state of charge, and C-rates, which impact both irreversible and reversible heat losses. The term

characterises the rate of change of the internal temperature of the battery over time, and is due to the electrochemical reactions and phase changes.

6. Conclusions

The rapid integration of renewable energy sources (RES) into the evolving electricity market presents a significant risk to power system stability. Previous studies indicate that Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS), with their fast response capability, are suitable for enhancing grid stability. This review has analysed the evolving energy market and the role of Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) in frequency regulation. It also examines the technical, regulatory, and economic factors that shape the operation of BESS in these markets, as well as the associated challenges and opportunities.

The analysis revealed that the RES market share is projected to reach 61% by 2030, with solar photovoltaic (PV) and wind power collectively contributing 40%. By 2050, it is projected to increase to 88% of RES, with solar photovoltaic (PV) and wind energy collectively accounting for 68%. BESS integration is also forecasted to grow significantly, reaching 1,200 GW by 2030, reflecting an increase of 1,050 GW since 2024. This upward trajectory is expected to persist, reaching 3,100 GW by 2050.

Rapidly changing market conditions, high integration of RES and BESS integration into frequency control ancillary service (FCAS) operations without fully understanding the BESS limitations in the FCAS market present several challenges. The main challenges include degradation from cycling, thermal management challenges at high C-rates, and system-level risks arising from poor visibility of BESS State of Health (SoH) and uncertainties in state-of-charge (SOC) and the effects of partial cycling. These factors can significantly impact the economic viability and reliability of BESS deployments, particularly in long-duration or high-frequency response applications. The effects of mini-, micro- and partial cycles have not yet been thoroughly investigated, potentially disadvantaging BESS operators in capacity payment markets such as the wholesale electricity market (WEM), where BESS operators receive compensation for variable cost elements.

Despite recent advancements, significant hurdles remain in optimising BESS performance and extending lifespan. Future research should focus on the development of advanced degradation models, adaptive control algorithms, and novel hybrid system configurations, such as battery energy storage systems (BESS) integrated with tailored algorithms and a deeper understanding of cyclic ageing mechanisms to address these gaps and unlock further performance improvements.

In conclusion, while BESS has certain drawbacks, its role in frequency control markets is projected to increase. Ongoing research and regulatory advancements are crucial to overcome current barriers and fully exploit BESS and low-emission energy systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, G.G.; Investigation, G.G.; Methodology, G.G.; Supervision, S.A., K.E., S.G.J.; Writing—original draft, G.G.; Writing—review and editing, G.G., S.A., K.E., S.G.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Australian Government, Department of Education, under National Industry PhD Program Grant - 40403.

Data Availability Statement

The relevant data are presented in the form of tables and graphs within this review paper.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no direct or indirect conflict of interest in this review paper.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BESS |

Battery Energy Storage System |

| BOL |

Beginning of Life |

| DoD |

Depth of Discharge |

| EMS |

Energy Management System |

| EOL |

End of Life |

| FCAS |

Frequency Control Ancillary Services |

| FFR |

Fast Frequency Response |

| GFL |

Grid Following |

| GFM |

Grid Forming |

| PFR |

Primary Frequency Response |

| PLL |

Phase Locked Loop |

| RES |

Renewable Energy Source |

| SFR |

Secondary Frequency Response |

| SOC |

State of Charge |

| SoC |

State of Charge |

| SoH |

State of Health |

| TFR |

Tertiary Frequency Response |

| VSC |

Voltage Source Converter |

References

- Liu, Y.; Chen, M.; Xie, B.; Ban, M. Integrated control strategy of BESS in primary frequency modulation considering SOC recovery. IET. Renew. Power Gener. 2024, 18, 875–886, doi:10.1049/rpg2.12959.

- Ratnam, K.S.; Palanisamy, K.; Yang, G. Future low-inertia power systems: Requirements, issues, and solutions - A review. Renewable Sustainable Energy 2020, 124, 109773, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.109773.

- Prakash, K.; Ali, M.; Siddique, M.N.I.; Chand, A.A.; Kumar, N.M.; Dong, D.; Pota, H.R. A review of battery energy storage systems for ancillary services in distribution grids: Current status, challenges and future directions. Frontiers in Energy Research 2022, 10.

- Argiolas, L.; Stecca, M.; Ramirez-Elizondo, L.M.; Soeiro, T.B.; Bauer, P. Optimal Battery Energy Storage Dispatch in Energy and Frequency Regulation Markets While Peak Shaving an EV Fast Charging Station. IEEE Open Access Journal of Power and Energy 2022, 9, 374–385, doi:10.1109/oajpe.2022.3198553.

- Brivio, C.; Mandelli, S.; Merlo, M. Battery energy storage system for primary control reserve and energy arbitrage. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks 2016, 6, 152–165, doi:10.1016/j.segan.2016.03.004.

- Fernández-Muñoz, D.; Pérez-Díaz, J.I.; Guisández, I.; Chazarra, M.; Fernández-Espina, Á. Fast frequency control ancillary services: An international review. em Renewable Sustainable Energy 2020, 120, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2019.109662.

- Energy Policy WA. (2024). Wholesale Electricity Market Rules (WEM Rules). Energy Policy WA - Government of Western Australia 2024, 918.

- Australian Energy Market Operator. (2023). Market Ancillary Service Specification (MASSA). Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). 2023; 39.

- Australian Energy Market Commission. (2025), National Electricity Rules. Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC). 2025; 39 224, [Accessed: March. 21, 2025].

- Australian Energy Market Operator. (2024). Summary of Frequency Co-optimised Essential System Services (FCESS). Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). 2024.

- Wu, C.H.; Jhan, J.Z.; Ko, C.H.; Kuo, C.C. Evaluating and Analyzing the Degradation of a Battery Energy Storage System Based on Frequency Regulation Strategies. Applied Sciences. 2022, 12, 6111.

- Shamarova, N.; Suslov, K.; Ilyushin, P.; Shushpanov, I. Review of Battery Energy Storage Systems Modeling in Microgrids with Renewables Considering Battery Degradation. Energies. 2022, 15, doi:10.3390/en15196967.

- Alcaide-Godinez, I.; Bai, F.; Saha, T.K.; Castellanos, R. Contingency reserve estimation of fast frequency response for battery energy storage system. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems 2022, 143, doi:10.1016/j.ijepes.2022.108428.

- Ember. (2024) World passes 30% renewable electricity milestone. Available online: https://ember-energy.org/latest-updates/world-passes-30-renewable-electricity-milestone/ (accessed on 21/04/2025).

- International Energy Agency (2024). Batteries and Secure Energy Transitions; International Energy Agency. 2024, 159.

- International Renewable Energy Agency. (2025), Renewable capacity statistics 2025. International Renewable Energy Agency Abu Dhabi, 2025, 75.

- International Energy Agency. (2021) Net Zero by 2050 - A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector. International Energy Agency France, 2021, 224.

- International Energy Agency. (2021) Global Energy Review 2021. International Energy Agency France, 2021, 32.

- International Energy Agency. (2024) International Energy Agency, France, 2024, 177.

- International Renewable Energy Agency. (2024) World Energy Transitions Outlook 2024: 1.5°C Pathway. International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi, 2024, 142.

- International Energy Agency. (2024) World Energy Outlook 2024; International Energy Agency, France, 2024, 396.

- Hassan, Q.; Viktor, P.; J. Al-Musawi, T.; Mahmood Ali, B.; Algburi, S.; Alzoubi, H.M.; Khudhair Al-Jiboory, A.; Zuhair Sameen, A.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. The renewable energy role in the global energy Transformations. Renewable Energy Focus, 2024, 48, 100545.

- United Nations Climate Change Conference. (2023) Summary of Global Climate Action at COP 28. United Nations Climate Change Conference, [Accessed: May 31, 2025].

- Rose, S.K.; Richels, R.; Blanford, G.; Rutherford, T. The Paris Agreement and next steps in limiting global warming. Climatic Change, 2017, 142, 255–270, doi:10.1007/s10584-017-1935-y.

- International Energy Agency. (2014) The Power of Transformation: Wind, Sun and the Economics of Flexible Power Systems. International Energy Agency, Paris, 2014.

- Pindar, R. Battery Report 2024: BESS surging in the ’Decade of Energy Storage’. Available online: www.mewburn.com/news-insights/battery-report-2024-bess-surging-in-the-decade-of-energy-storage (accessed on 22/4/2025).

- Rayner, T. Volta’s 2024 Battery Report: Falling costs drive battery storage gains. PV Magazine - Energy Storage, Jan 29, 2025, Available online: www.ess-news.com/2025/01/29/voltas-2024-battery-report-falling-costs-drive-battery-storage-gains/ (accessed on 22/4/2025).

- U.S. Energy Information Administration. (2025) Preliminary Monthly Electric Generator Inventory (based on Form EIA-860M as a supplement to Form EIA-860). U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2025 Available online: www.eia.gov/electricity/data/eia860m/ (accessed on 22/5/2025).

- Colthorpe, A. Europe installed 12GW of energy storage in 2024; EU state aid boost to come. Available online: https://www.energy-storage.news/europe-12gw-energy-storage-2024-eu-state-aid-boost-to-come/ (accessed on 25/04/2025).

- A. Rendón, M.; R. Novgorodcev, A.; De A. Fernandes, D. Mathematical Model of a 106 MW Single Shaft Heavy-Duty Gas Turbine. In Proceedings of the Anais do Simpósio Brasileiro de Sistemas Elétricos, 2020–08–13, 2020.

- Gagné, J.F. Battery Storage Unlocked: Lessons Learned from Emerging Economies. National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), November 2024, 2024, 48.

- Nsitem, N. Global Energy Storage Market Records Biggest Jump Yet. Available online: https://about.bnef.com/blog/global-energy-storage-market-records-biggest-jump-yet/ (accessed on 23/04/2025).

- Energy Information Administration. U.S. battery capacity increased 66% in 2024. Available: www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/ detail.php?id=64705# (Accessed: May 31, 2025).

- Arruebo, A.; Lits, C.; Rossi, R.; Schmela, M.; Acke, D.; Augusto, C.; Osenberg, J.; Chevillard, N.; Dupond, S.; SolarPower Europe. European Market Outlook for Battery Storage 2024-2028. SolarPower Europe, Brussels, Belgium, 2024.

- Clean Energy Council. (2024) Clean Energy Australia 2024. Clean Energy Council, Australia; 96.

- International Energy Agency. (2021) Net Zero by 2050 - A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector. International Energy Agency France, October 2021, 2021; 224.

- Jarbratt, G.; Jautelat, S.; Linder, M.; Sparre, E.; Rijt, A.v.d.; Wong, Q.H. Enabling renewable energy with battery energy storage systems. Available online: www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/enabling-renewable-energy-with-battery-energy-storage-systems#/ (accessed on 23/04/2025).

- Blair, N.; Augustine, C.; Cole, W.; Denholm, P.; Frazier, W.; Geocaris, M.; Jorgenson, J.; McCabe, K.; Podkaminer, K.; Prasanna, A.; Sigrin B. Storage Futures Study: Key Learnings for the Coming Decades. National Renewable Energy Laboratory [NREL], Golden, Colorado, USA, 2022, 28.

- European Association for Storage of Energy. (2022) Energy Storage Targets 2030 and 2050: Ensuring Europe’s Energy Security in a Renewable Energy System. European Association for Storage of Energy (EASE), Brussels, Belgium, 2022.

- Council of the European Union. (2023) Energy Storage - Underpinning a decarbonised and secure EU energy system. 2023.

- Lomax, J. Battery Storage Connection Queue Double the Grid’s Requirement for 2030. Available online: www.cornwall-insight.com/press-and-media/press-release/battery-storage-connection-queue-double-the-grids-requirement-for-2030/ (accessed on 23/04/2025).

- CSIRO. Renewable Energy Storage Roadmap. CSIRO, Black Mountain ACT 2601, Australia, 2023; 200.

- Zhang, Z.; Ding, T.; Zhou, Q.; Sun, Y.; Qu, M.; Zeng, Z.; Ju, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, K.; Chi, F. A review of technologies and applications on versatile energy storage systems. Renewable Sustainable Energy, 2021, 148, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.111263.

- He, C.; Geng, H.; Rajashekara, K.; Chandra, A. Analysis and Control of Frequency Stability in Low-Inertia Power Systems: A Review. IEEE/CAA Journal of Automatica Sinica, 2024, 11, 2363–2383, doi:10.1109/JAS.2024.125013.

- Datta, U.; Kalam, A.; Shi, J. A review of key functionalities of battery energy storage system in renewable energy integrated power systems. Energy Storage. 2021, 3, doi:10.1002/est2.224.

- Mexis, I.; Todeschini, G. Battery energy storage systems in the United Kingdom: a review of current state-of-the-art and future applications. Energies, 2020, 13, 3616.

- Fernández-Guillamón, A.; Gómez-Lázaro, E.; Muljadi, E.; Molina-Garcia, Á. A review of virtual inertia techniques for renewable energy-based generators. Renewable Energy-Technologies and Applications, 2020.

- Australian Energy Market Operator (2023). Inertia in the NEM explained. Available online: https://aemo.com.au/-/media/files/initiatives/engineering-framework/2023/inertia-in-the-nem-explained.pdf, (Accessed: May 31, 2025).

- Obaid, Z.A.; Cipcigan, L.M.; Abrahim, L.; Muhssin, M.T. Frequency control of future power systems: reviewing and evaluating challenges and new control methods. Journal of Modern Power Systems and Clean Energy, 2019, 7, 9–25.

- Australian Energy Market Operator. (2024) WEM Procedure Frequency Co-optimised Essential System Services (FCESS) Accreditation. Australian Energy Market Operator (aemo), 2024, 45.

- Modig, N., Eriksson, R., Ruokolainen, P., Ødegård, J. N., Weizenegger, S., Fechtenburg, T. D. Overview of Frequency Control in the Nordic Power System. Nordic Analysis Group, 2022, 20.

- National Energy System Operator. (2024) Frequency response services. Available online: https://www.nationalgrideso.com/industry-information/balancing-services/frequency-response-services (accessed on 29/08/2024).

- EirGrid. (2024) EirGrid Grid Code, EirGrid Grid Code Version 14.2, 461.

- Shoeb, M.A.; Shahnia, F.; Shafiullah, G.M. A multilayer optimization scheme to retain the voltage and frequency in standalone microgrids. IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies-Asia (ISGT-Asia), 2017, 1–6.

- Fernández-Guillamón, A.; Gómez-Lázaro, E.; Muljadi, E.; Molina-Garcia, Á. A review of virtual inertia techniques for renewable energy-based generators. Renewable Energy-Technologies and Applications, 2020.

- Broderick, C. Rate of change of frequency (RoCoF) withstand capability. ENTSO-E, Brussels, Belgium, 2018.

- Australian Energy Market Commission. (2021) Fast frequency response market ancillary services. Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC), 2021, 2.

- Greenwood, D.M.; Lim, K.Y.; Patsios, C.; Lyons, P.F.; Lim, Y.S.; Taylor, P.C. Frequency response services designed for energy storage. Applied Energy, 2017, 203, 115–127, doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.06.046.

- Bryant, M.J.; Ghanbari, R.; Jalili, M.; Sokolowski, P.; Meegahapola, L. Frequency control challenges in power systems with high renewable power generation: An Australian perspective. RMIT University, 2019.

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation (2020). Fast Frequency Response Concepts and Bulk Power System Reliability Needs. The North American Electric Reliability Corporation, Atlanta, USA, 2020; 29.

- Meng, L.; Zafar, J.; Khadem, S.K.; Collinson, A.; Murchie, K.C.; Coffele, F.; Burt, G.M. Fast Frequency Response From Energy Storage Systems—A Review of Grid Standards, Projects and Technical Issues. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 2020, 11, 1566–1581, doi:10.1109/TSG.2019.2940173.

- Andrenacci, N.; Chiodo, E.; Lauria, D.; Mottola, F. Life cycle estimation of battery energy storage systems for primary frequency regulation. Energies, 2018, 11, 3320.

- Shair, J.; Li, H.; Hu, J.; Xie, X. Power system stability issues, classifications and research prospects in the context of high-penetration of renewables and power electronics. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2021, 145, 111111.

- Alam, M.S.; Al-Ismail, F.S.; Salem, A.; Abido, M.A. High-Level Penetration of Renewable Energy Sources Into Grid Utility: Challenges and Solutions. IEEE Access, 2020, 8, 190277–190299, doi:10.1109/access.2020.3031481.

- Saleem, M.I.; Saha, S. Assessment of frequency stability and required inertial support for power grids with high penetration of renewable energy sources. Electric Power Systems Research, 2024, 229, 110184, doi:10.1016/j.epsr.2024.110184.

- Xiong, L.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y. Performance Comparison of Typical Frequency Response Strategies for Power Systems With High Penetration of Renewable Energy Sources. IEEE Journal on Emerging and Selected Topics in Circuits and Systems, 2022, 12, 41–47, doi:10.1109/jetcas.2022.3141691.

- Haque, M.A.; Hasib, M.A.; Jawad, A.; Islam, M.Z. Investigation of Frequency and Voltage Stability of High Renewable Penetrated Grid. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 11th Region 10 Humanitarian Technology Conference (R10-HTC), 16–18 Oct. 2023, 2023; 132–137.

- Buch, K. Ramp-Rate Limiting Inverter Control Using Predicted Irradiance. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Texas Power and Energy Conference (TPEC), 12–13 Feb. 2024, 2024; 1–5.

- Yan, H.W.; Beniwal, N.; Farivar, G.G.; Pou, J. A power ramp rate control strategy with reduced energy storage utilization for grid-connected photovoltaic systems. In 2023 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), 29 October - 02 November 2023, 2023; 657–662.

- Liu, J.; Song, Y.W.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, H.L.; Zheng, S.Q. Effect of Fluctuation of Wind Power Output on Power System Risk. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2014, 513-517, 2971–2974, doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.513-517.2971.

- Senarathna, N.T.; Somathilaka, S.P.; Hemapala, K.; Banda, H.W. Frequency Stability in Renewable-Rich Power Systems with High Solar Ramps. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Electrical, Control and Instrumentation Engineering (ICECIE), 2024–11–23, 2024; 1–5.

- Kerdphol, T.; Rahman, F.S.; Watanabe, M.; Mitani, Y.; Turschner, D.; Beck, H.-P. Enhanced virtual inertia control based on derivative technique to emulate simultaneous inertia and damping properties for microgrid frequency regulation. IEEE Access, 2019, 7, 14422–14433.

- Soto, A.; Berrueta, A.; Mateos, M.; Sanchis, P.; Ursúa, A. Impact of micro-cycles on the lifetime of lithium-ion batteries: An experimental study. Journal of Energy Storage, 2022, 55, 105343, doi:10.1016/j.est.2022.105343.

- Guo, J.; Li, Z.; Pecht, M. A Bayesian approach for Li-Ion battery capacity fade modeling and cycles to failure prognostics. Journal of Power Sources, 2015, 281, 173–184.

- Nuroldayeva, G.; Serik, Y.; Adair, D.; Uzakbaiuly, B.; Bakenov, Z. State of Health Estimation Methods for Lithium-Ion Batteries. International Journal of Energy Research, 2023, 2023, 1–21, doi:10.1155/2023/4297545.

- Edge, J.S.; O’Kane, S.; Prosser, R.; Kirkaldy, N.D.; Patel, A.N.; Hales, A.; Ghosh, A.; Ai, W.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; et al. Lithium ion battery degradation: what you need to know. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 2021, 23, 8200–8221, doi:10.1039/d1cp00359c.

- Attia, P.M.; Bills, A.; Brosa Planella, F.; Dechent, P.; Dos Reis, G.; Dubarry, M.; Gasper, P.; Gilchrist, R.; Greenbank, S.; Howey, D.; et al. Review—“Knees” in Lithium-Ion Battery Aging Trajectories. Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 2022, 169, 060517, doi:10.1149/1945-7111/ac6d13.

- IEEE Recommended Practice for Sizing Lead-Acid Batteries for Stationary Applications. IEEE Std 485-2020 (Revision of IEEE Std 485-2010), 2020, 1–69, doi:10.1109/IEEESTD.2020.9103320.

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Y.; Du, X.; Wei, Z. Research on Low Voltage Ride Through Control Strategy of BESS Considering Fault Recovery Characteristics. In 2023 IEEE Sustainable Power and Energy Conference (iSPEC), 2023; pp. 1–4.

- Howlader, A.M.; Senjyu, T. A comprehensive review of low voltage ride through capability strategies for the wind energy conversion systems. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2016, 56, 643–658, doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.11.073.

- Mahela, O.P.; Gupta, N.; Khosravy, M.; Patel, N. Comprehensive Overview of Low Voltage Ride Through Methods of Grid Integrated Wind Generator. IEEE Access, 2019, 7, 99299–99326, doi:10.1109/access.2019.2930413.

- North American Electric Reliability Corporation. (2021) Balancing and Frequency Control Reference Document Prepared by the NERC Resources Sub-committee; North American Electric Reliability Corporation, Atlanta, USA, 11/05/2021, 2021; 41.

- Wang, X.T.; Gu, Z.Y.; Ang, E.H.; Zhao, X.X.; Wu, X.L.; Liu, Y. Prospects for managing end-of-life lithium-ion batteries: Present and future. Interdisciplinary Materials, 2022, 1, 417–433, doi:10.1002/idm2.12041.

- Bergveld, H.J.; Kruijt, W.S.; Notten, P.H.; Bergveld, H.J.; Kruijt, W.S.; Notten, P.H. Battery management systems; Springer, 2002.

- Tian, H.; Qin, P.; Li, K.; Zhao, Z. A review of the state of health for lithium-ion batteries: Research status and suggestions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2020, 261, 120813.

- Zhang, X.; Han, Y.; Zhang, W. A review of factors affecting the lifespan of lithium-ion battery and its health estimation methods. Transactions on Electrical and Electronic Materials, 2021, 22, 567–574.

- Chen, J.; Han, X.; Sun, T.; Zheng, Y. Analysis and prediction of battery aging modes based on transfer learning. Applied Energy, 2024, 356, doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.122330.

- Deshpande, R.D.; Bernardi, D.M. Modeling Solid-Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) Fracture: Coupled Mechanical/Chemical Degradation of the Lithium Ion Battery. Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 2017, 164, A461–A474, doi:10.1149/2.0841702jes.

- Guan, T.; Sun, S.; Gao, Y.; Du, C.; Zuo, P.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yin, G. The effect of elevated temperature on the accelerated aging of LiCoO2/mesocarbon microbeads batteries. Applied Energy, 2016, 177, 1–10, doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.05.101.

- Yang, X.-G.; Leng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Ge, S.; Wang, C.-Y. Modeling of lithium plating induced aging of lithium-ion batteries: Transition from linear to nonlinear aging. Journal of Power Sources, 2017, 360, 28–40, doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.05.110.

- Xu, K. Nonaqueous Liquid Electrolytes for Lithium-Based Rechargeable Batteries. Chemical Reviews, 2004, 104, 4303–4418, doi:10.1021/cr030203g.

- Bhattacharya, S.; Riahi, A.R.; Alpas, A.T. Thermal cycling induced capacity enhancement of graphite anodes in lithium-ion cells. Carbon, 2014, 67, 592–606, doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2013.10.032.

- Mehta, R.; Gupta, A. Mathematical modelling of electrochemical, thermal and degradation processes in lithium-ion cells—A comprehensive review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2024, 192, 114264.

- Spotnitz, R.; Franklin, J. Abuse behavior of high-power, lithium-ion cells. Journal of Power Sources, 2003, 113, 81–100, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7753(02)00488-3.

- Kumar, R.R.; Bharatiraja, C.; Udhayakumar, K.; Devakirubakaran, S.; Sekar, K.S.; Mihet-Popa, L. Advances in Batteries, Battery Modeling, Battery Management System, Battery Thermal Management, SOC, SOH, and Charge/Discharge Characteristics in EV Applications. IEEE Access, 2023, 11, 105761–105809, doi:10.1109/access.2023.3318121.

- Mdachi, N. K., Chang, C.K. Comparative review of thermal management systems for BESS. Batteries, 2024, 10, 224. doi.org/10.3390/batteries10070224.

- Alipour, M.; Esen, E.; Varzeghani, A.R.; Kizilel, R. Performance of high capacity Li-ion pouch cells over wide range of operating temperatures and discharge rates. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry, 2020, 860, 113903, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelechem.2020.113903.

- Baghdadi, I.; Briat, O.; Delétage, J.-Y.; Gyan, P.; Vinassa, J.M. Lithium battery aging model based on Dakin’s degradation approach. Journal of Power Sources, 2016, 325, 273–285, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.06.036.

- Bandhauer, T. M., Garimella, S., Fuller, T. F. A critical review of thermal issues in lithium-ion batteries. Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 158(3), R1, doi https://doi.10.1149/1.3515880.

- Thomas, K. E., Newman, J. Thermal modeling of porous insertion electrodes. Journal of the Electrochemical Society, 2003, 150(2), A176.

- Bernardi, D., Pawlikowski, E., & Newman, J. A general energy balance for battery systems. Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 1984, 132(5), 5-12.

- Liu, G., Ouyang, M., Lu, L., Li, J., & Han, X. Analysis of the heat generation of lithium-ion battery during charging and discharging considering different influencing factors. Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry, 2014, 116, 1001–1010.

- Silva, M. F., Guimarães, G. C., Moura, F. A. M., Rodrigues, D. B., Souza, A. C., & Silva, L. R. C. System frequency support by synthetic inertia control via BESS. In 2019 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference - Latin America (ISGT Latin America), 2019, 1–6.

- Chen, H., Cong, T. N., Yang, W., Tan, C., Li, Y., & Ding, Y. Progress in electrical energy storage system: A critical review. Progress in Natural Science, 2009, 19(3), 291–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnsc.2008.07.014.

- Mexis, I., & Todeschini, G. Battery energy storage systems in the United Kingdom: A review of current state-of-the-art and future applications. Energies, 2020, 13(14), 3616.

- Sahoo, S., & Timmann, P. (2023). Energy storage technologies for modern power systems: A detailed analysis of functionalities, potentials, and impacts. IEEE Access, 11, 49689–49729.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).