1. Introduction

Since the global outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in 2020, the emergence of new viral variants and the strain on healthcare resources have continued to impact healthcare systems and public health worldwide [

1,

2,

3]. Although the global infection situation has shown signs of stabilization, the COVID-19 experience has raised important questions regarding how to prepare for and respond to future infectious disease outbreaks [

4,

5].

Typical symptoms of COVID-19 include upper respiratory tract inflammation, fever, and disturbances in taste and smell. In addition, extrapulmonary complications such as cardiovascular involvement and thromboembolic events have also been reported [

6,

7]. Musculoskeletal impairments and declines in physical function have been frequently observed in patients with COVID-19 [

8,

9,

10]. In particular, elderly individuals and patients with more severe disease are susceptible to declines in activities of daily living, which may be associated with reduced physical activity due to prolonged isolation [

11,

12,

13]. These physical consequences may also negatively affect health-related quality of life and mental well-being [

14,

15,

16].

While pharmacological interventions and vaccines have evolved throughout the pandemic, the role of non-pharmacological approaches such as rehabilitation has also gained attention. Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) has been reported to be effective in post-acute or Long-COVID patients, and recent studies continue to support its benefits [

11,

17,

18,

19,

20]. However, limited evidence is available regarding the safety and effectiveness of PR interventions during the acute phase of hospitalization. In 2020, early bedside rehabilitation was recommended for patients with severe COVID-19 by an international task force [

21], but it remains unclear whether similar early interventions are needed or appropriate for patients with moderate disease severity who are isolated but not admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).

The purpose of this study was to investigate the safety of early multidisciplinary rehabilitation interventions at the bedside in non-ICU patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia under infection isolation. In addition, we aimed to evaluate their functional status and health-related quality of life.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This prospective, single-arm interventional study was conducted at the Kanagawa Cardiovascular and Respiratory Center, a specialized medical facility providing advanced care for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Kanagawa Cardiovascular and Respiratory Center served as a designated core hospital for managing COVID-19 patients in Kanagawa Prefecture—an urban region neighboring Tokyo and one of Japan's most populous areas. The hospital maintains an infectious isolation ward equipped for safe inpatient care during outbreaks. This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee (KCRC-20-0047), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

2.2. Study Population

Eligible participants were patients with COVID-19 pneumonia who were admitted to the infectious isolation ward. Patients who required invasive mechanical ventilation were not included, as our hospital does not manage patients with severe or critical COVID-19. All patients referred to PR after admission were screened. Inclusion criteria were as follows: diagnosed with COVID-19 pneumonia, oxygen saturation measured by pulse oximetry (SpO2) ≤ 95% at rest on room air, capacity to understand and perform the exercise program under infection control precautions. Exclusion criteria included: exercise-induced desaturation judged as clinically significant, limitations to exercise due to complications or physical disability, cardiac conditions contraindicating physical activity, physician's restriction against rehabilitation, dementia, visual or hearing impairments that interfered with participation in the program.

2.3. Intervention

The exercise training program was conducted entirely at the bedside or immediately adjacent to the bed within each patient’s isolation room. It was designed to be feasible, safe, and adaptable to varying functional levels. Three tiers of programs—supine, sitting, and standing—were implemented according to the patient’s physical status and progression. Supine program included lower limb strength exercises (leg raises and hip abductions using a stretch band, 5 repetitions each) and early mobilization tasks such as maintaining a sitting posture on the bed for up to 5 minutes. Sitting program consisted of seated respiratory stretching exercises (5 minutes), lower limb resistance training using elastic bands (10 repetitions each), and sit-to-stand exercises using a table for support (5 repetitions). Standing program included standing respiratory stretching (5 minutes), as well as lower limb strengthening exercises such as calf raises and squats with chair support (10 repetitions each). Progression from one program to the next was guided by clinical evaluation, allowing patients to move from the supine to the sitting and then standing program as their condition improved. In addition, breathing exercises and airway clearance techniques were actively encouraged. Patients were also recommended to maintain an awake prone position outside of training sessions when possible.

2.4. Assessments

Baseline demographic and clinical information was collected. During each training session, the Modified Borg Scale (MBS) for perceived exertion, SpO2, and heart rate (HR) were monitored to assess physical response and safety. Feasibility was evaluated based on the occurrence of adverse events and the adherence rate to the program. Adherence was calculated as the percentage of days on which rehabilitation was actually performed relative to the total scheduled days.

Functional and psychological outcomes were assessed both at baseline and at hospital discharge. 1-minute sit-to-stand test (1MSTST) was performed using a standard armless chair (seat height: 40 cm), with the number of repetitions recorded. MBS, SpO2, and HR were measured before and after the test. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Test (CAT) was used to assess respiratory symptoms. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was used to evaluate psychological well-being.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were presented as means with standard deviations, or medians with interquartile ranges for non-normally distributed data. Categorical data were summarized as counts and percentages. Comparisons between baseline and discharge values were made using the Mann–Whitney analysis. Associations between baseline characteristics and outcomes were explored using Spearman test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), with a significance threshold set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

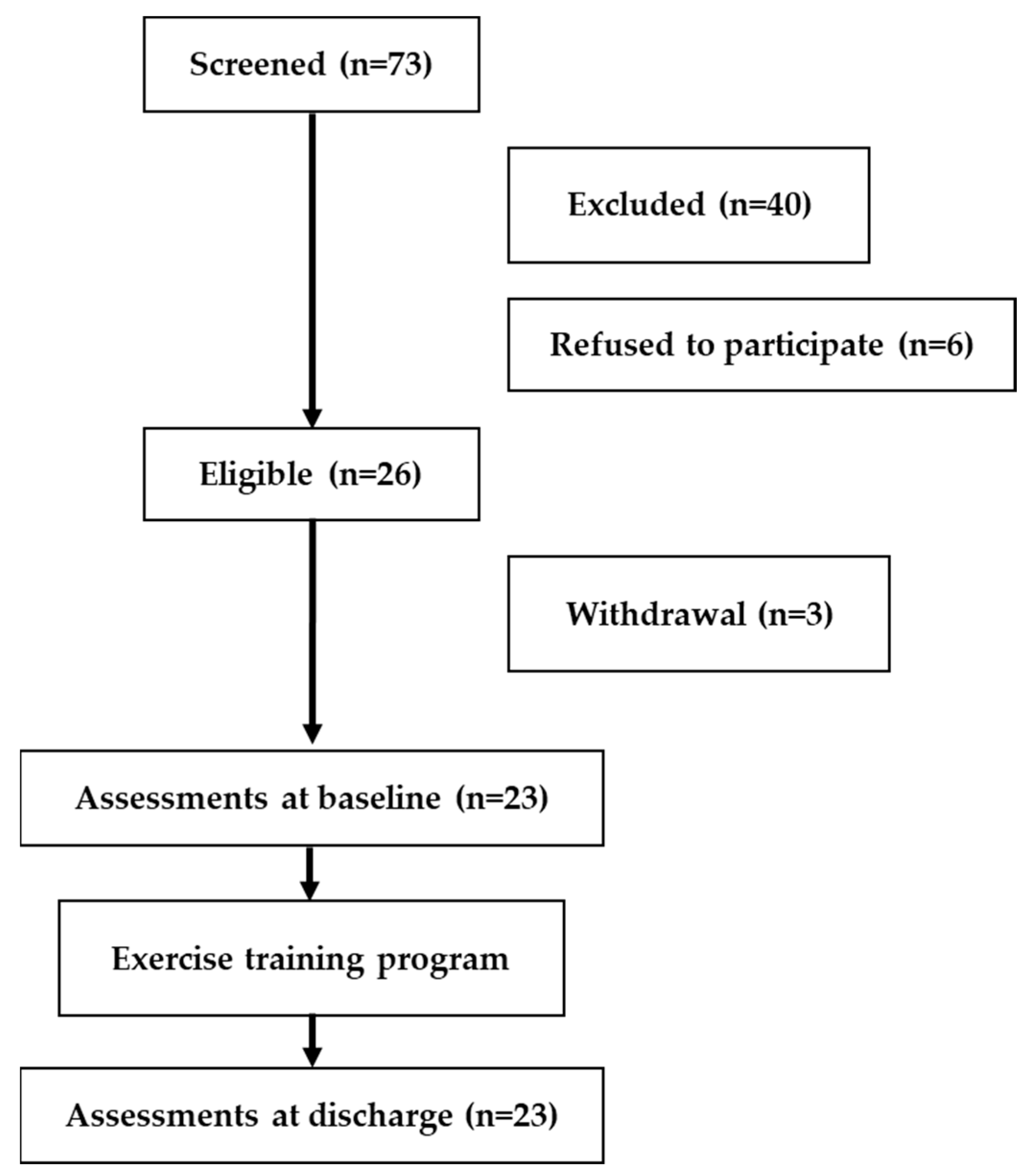

Between February and August 2021—corresponding to the latter half of the third to the middle of the fifth COVID-19 wave in Japan—73 newly hospitalized patients were referred to PR. Following eligibility screening (

Figure 1), 40 patients were excluded: 13 due to difficulty with exercise, 12 with dementia and severe frailty, 11 with significant exertional hypoxemia, 2 without physician authorization, and 2 due to language barriers. An additional 6 patients refused to participate. In total, 26 patients provided consent. Of these, three later withdrew due to worsening symptoms (e.g., disease progression, nausea/dizziness, or bradycardia), resulting in 23 participants who completed the program.

COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. While three participants had obstructive sleep apnea, none had chronic respiratory comorbidities such as COPD, asthma, or interstitial lung disease. At admission, 65% were receiving oxygen therapy, increasing to 70% during hospitalization. All participants were administered antiviral medication. The median (IQR) length of hospital stay was 13.0 days (12.0–19.0).

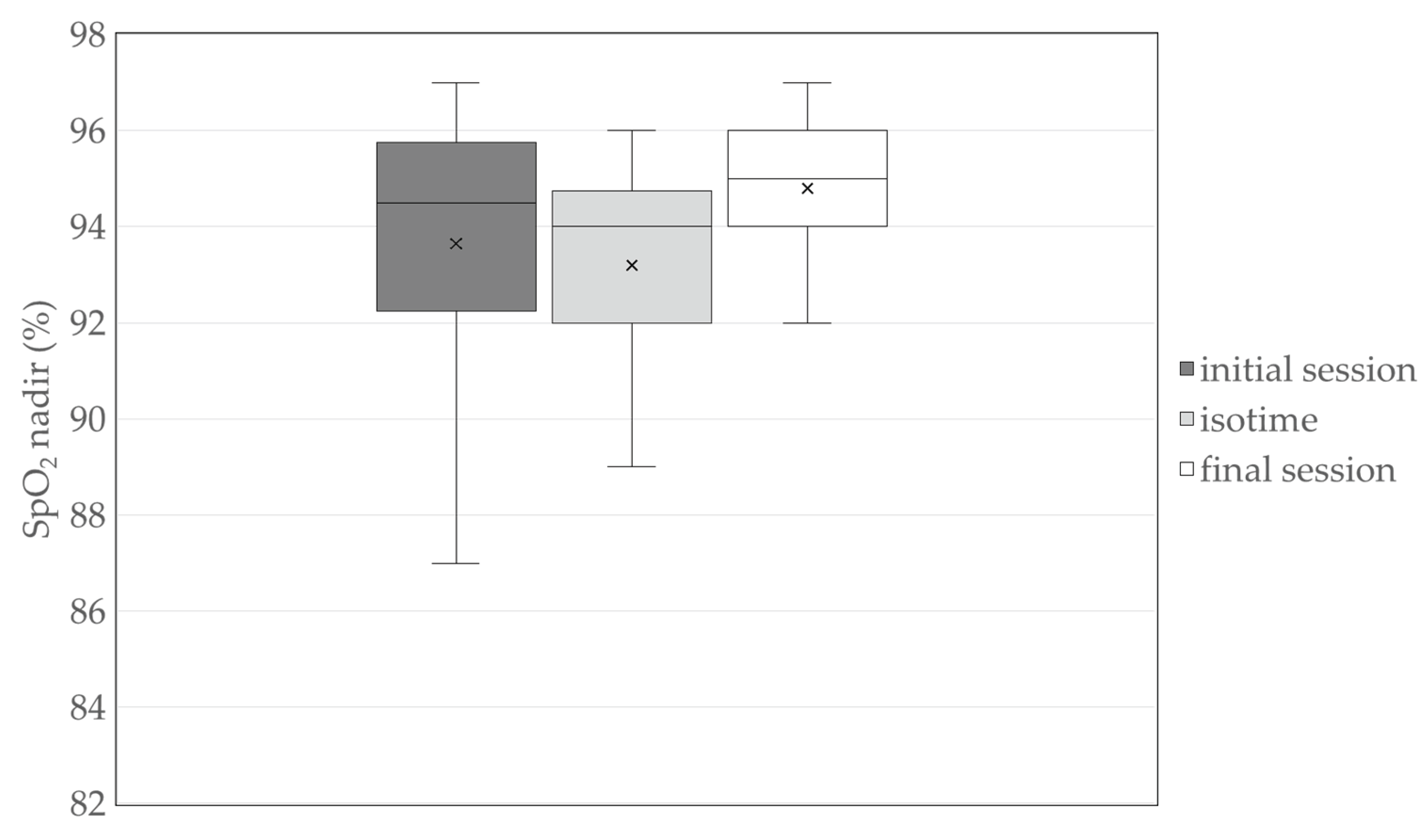

Participants underwent a median of 5.0 (3.0–7.0) bedside PR sessions, with an overall adherence rate of 71%. No adverse events or dropouts occurred during either the intervention or assessments. Desaturation (SpO2 < 90%) was observed in three participants during the initial session only. SpO2 nadir values across the initial session, final session, and isotime (the session with the lowest SpO2 nadir recorded between the initial and final sessions) are presented in

Figure 2.

3.2.1. MSTST Outcomes

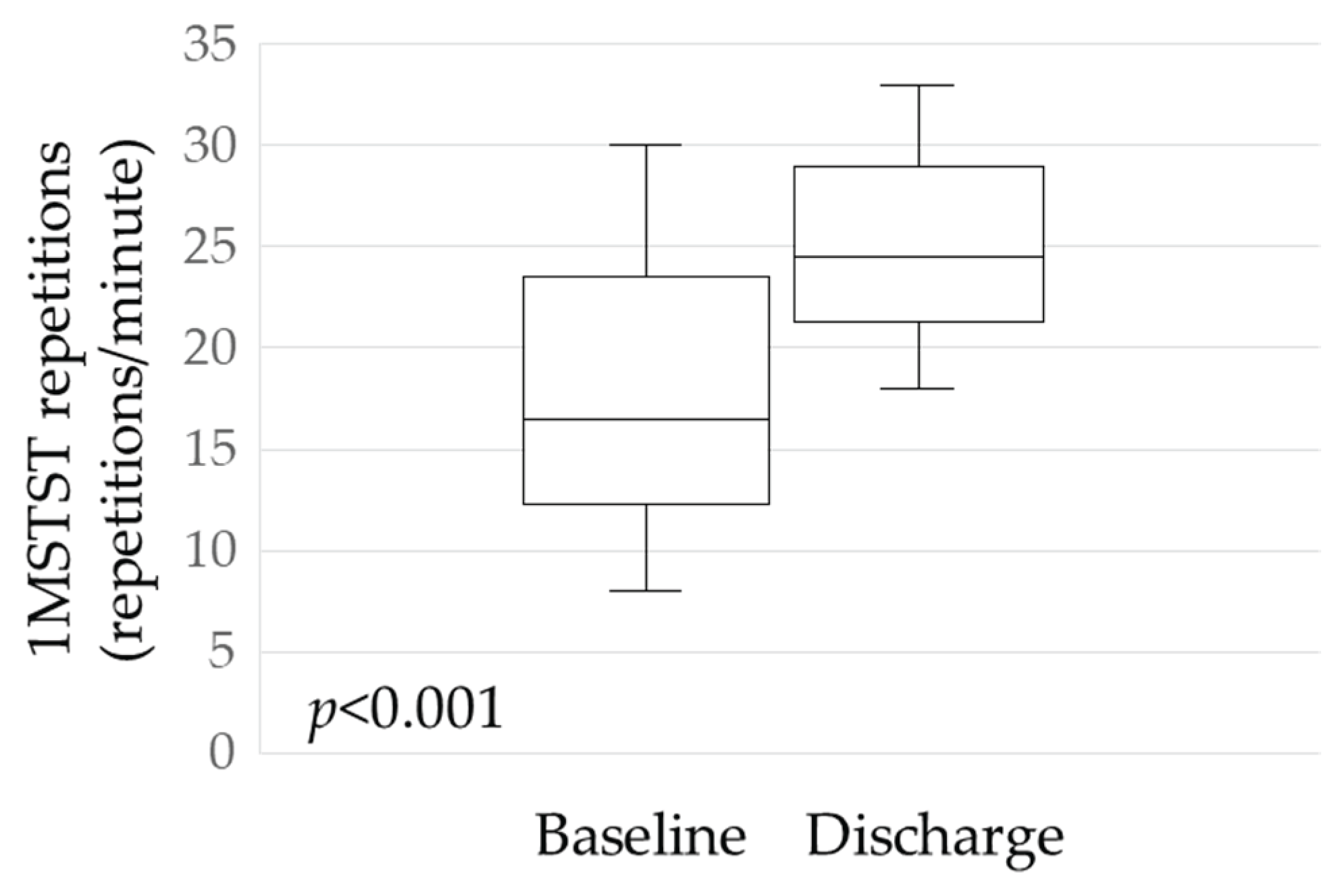

A significant change was observed in physical performance: the mean increase in 1MSTST repetitions from baseline to discharge was 7.6 (p < 0.001;

Figure 3).

Table 2 presents additional comparisons of cardiorespiratory parameters and MBS scores during the 1MSTST. Both SpO2 nadir and HR peak increased significantly (p = 0.013 and p < 0.001, respectively). However, no significant differences were seen in peak MBS scores or changes in SpO2, HR, and MBS between assessments.

1MSTST, 1-min sit-to-stand test.

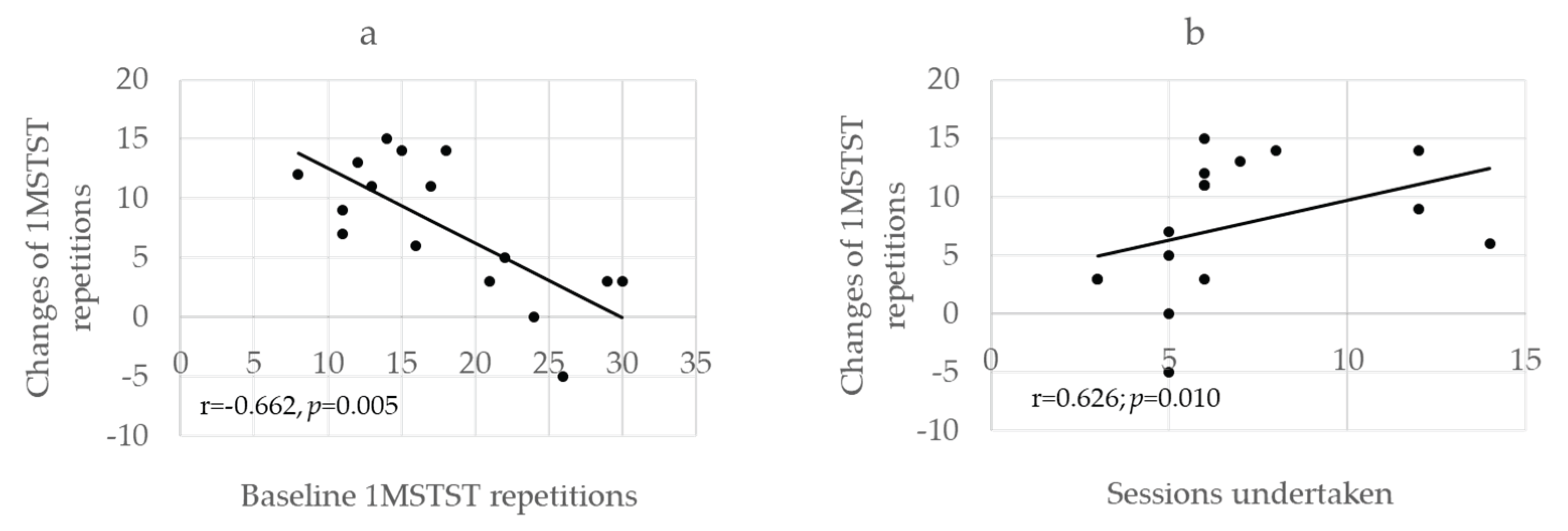

At baseline, four participants experienced desaturation below 90% during the 1MSTST despite receiving supplemental oxygen. A significant negative correlation was found between baseline 1MSTST repetitions and their changes after PR (r = –0.662, p = 0.005;

Figure 4a). Conversely, a significant positive correlation was observed between the number of sessions completed and the change in repetitions (r = 0.626, p = 0.010;

Figure 4b).

1MSTST, 1-min sit-to-stand test.

3.3. Health-Related Quality of Life Outcomes

Table 3 shows changes in CAT scores between baseline and discharge. Total scores, as well as individual items for cough and chest tightness, showed significant decrease.

Mental health status was assessed using HADS. At baseline, 18% and 14% of participants scored ≥11 for anxiety and depression, respectively. While the proportion of participants with anxiety remained similar at discharge (19%), the proportion with depression increased to 38%.

4. Discussion

This study implemented PR for non-ICU, moderately ill COVID-19 patients under isolation and explored the safety and clinical responses using 1MSTST, CAT, and HADS. All 23 patients completed the program without adverse events or early termination, underscoring the feasibility of such interventions even during the acute phase under isolation protocols. While the study followed a single-arm design, our findings suggest that these simple tools can be practically utilized for functional assessment and can reflect short-term changes in patients’ exercise tolerance, dyspnea, and quality of life.

Although PR at the bedside has been addressed in international guidelines by the ERS/ATS, Australian clinical practice recommendations, and Italian position statements, they primarily focus on patients recovering from critical illness or those in subacute stages [

21,

22,

23]. There is a notable lack of concrete evidence addressing rehabilitation during the acute phase in general wards. A recent study by Jianramas et al., which involved mild to moderate COVID-19 patients in isolated wards similar to our setting, examined the safety of physiotherapy with different frequencies and found no significant differences in complications, ICU transfers, or in-hospital mortality [

24]. While PR is not contraindicated in the acute phase, implementation remains challenging due to concerns over infection control. Our study addresses this critical gap by demonstrating both the safety and feasibility of such interventions.

Regarding safety, there were no significant adverse effects from the initial session onward, and the intervention was initiated at a mean of 11 days post-symptom onset. This timing aligns with previous evidence suggesting the importance of early rehabilitation within 3 weeks [

25], and complies with Chinese guidelines advising against initiating within the first 7 days [

26]. Combining this timing with a strategy of minimal yet direct contact—where physiotherapists, equipped with full personal protective equipment, provided instruction in person—helped establish a safe and structured protocol, which may serve as a reference for future program design.

The 1MSTST proved to be a valuable assessment tool, requiring minimal space or equipment and being executable in a short time [

27]. Previous observational research proposed its utility in triage of COVID-19 patients [

28], but our study extends this by incorporating concurrent assessments of psychological and quality-of-life parameters. A recent report by Bellone et al. also demonstrated significant correlations between initial Barthel Index scores and functional gains, as well as between the number of sessions and improvements—mirroring our findings regarding baseline and change in 1MSTST and its association with the number of sessions [

29]. These parallels support the reproducibility and potential efficacy of early individualized rehabilitation under isolation for moderately ill COVID-19 patients.

Furthermore, a significant increase in peak heart rate following the 1MSTST was observed, potentially reflecting improved cardiopulmonary responsiveness. However, autonomic dysfunction—such as postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome—has also been reported in the context of post-COVID sequelae [

30]. Recognizing such changes may contribute to developing safer acute-phase interventions and more tailored post-COVID rehabilitation strategies [

31].

Although the CAT was originally developed for COPD, our results indicate its applicability in quantitatively tracking symptom changes in acute-phase, isolated patients. Previous studies have shown its relevance in post-COVID recovery [

32,

33], and our findings suggest that the CAT may offer utility not only in the chronic or recovery phases, but also during the acute stage, supporting continuous symptom monitoring across the disease spectrum.

In terms of psychological impact, COVID-19 patients in isolation often exhibit heightened anxiety rather than depression [

34]. In our study, HADS-anxiety scores remained stable during hospitalization, while HADS-depression scores significantly worsened. This aligns with post-discharge follow-up data from Italian cohorts, which demonstrated greater physical recovery compared to limited improvements in mental health-related quality of life [

35]. These results underscore the need to integrate psychological support alongside physical interventions, especially for patients undergoing rehabilitation in isolated and stressful environments.

4.1. Study Limitations

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, as a single-arm retrospective study, establishing causality is inherently difficult. Second, the sample size was relatively small (n=23) and confined to a single institution, which may limit generalizability. Third, due to the decline in isolated COVID-19 wards, replication in multicenter studies may be challenging. Nevertheless, our findings represent a rare and valuable documentation of early PR during the acute isolation phase of COVID-19, potentially informing protocols for other infectious or acute respiratory conditions.

4.2. Clinical Implications

Looking ahead, the implementation model explored in this study may offer critical insights for future pandemic preparedness. PR under infection control constraints should be considered not as an exceptional measure, but as a fundamental component of acute care strategy during emerging infectious disease outbreaks.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the safety and feasibility of PR delivered under isolation during the acute phase of COVID-19 in patients with moderate pneumonia. The 1MSTST and CAT were suggested to be useful tools for evaluating both physiological responses—such as heart rate and SpO2—and subjective symptoms in the early phase of infection. A comprehensive assessment that includes psychological aspects may also contribute to the early detection and management of autonomic dysfunction and post-COVID conditions. These findings provide practical insights into the implementation and evaluation of rehabilitation interventions during the acute stage of COVID-19.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N., T.S. and T.O.; methodology, A.N. and T.S.; patient recruitment, Y.A. and S.I.; data collection, Y.A. and S.I.; formal analysis, A.N. and Y.A.; investigation, A.N. and Y.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N.; supervision, S.K., E.H. and T.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee (protocol code KCRC-20-0047) (date of approval: 9 February 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| COVID-19 |

Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| PR |

Pulmonary rehabilitation |

| ICU |

Intensive care unit |

| SpO2

|

Oxygen saturation |

| MBS |

Modified Borg Scale |

| HR |

Heart rate |

| 1MSTST |

1-minute sit-to-stand test |

| CAT |

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Test |

| HADS |

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

References

- Alakija, A. Leveraging lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic to strengthen low-income and middle-income country preparedness for future global health threats. Lancet Infect Dis 2023, 23, e310–e317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanoue, Y.; Cao, A.; Koda, M.; Harada, N.; Ghaznavi, C.; Nomura, S. Changes in Healthcare Utilization in Japan in the Aftermath of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Time Series Analysis of Japanese National Data Through November 2023. Healthcare (Basel) 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesińska, W.; Biernatek, M.; Lachowicz-Wiśniewska, S.; Piątek, J. Systematic Review of the Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Systems and Society-The Role of Diagnostics and Nutrition in Pandemic Response. J Clin Med 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauci, A.S.; Folkers, G.K. Pandemic Preparedness and Response: Lessons From COVID-19. J Infect Dis 2023, 228, 422–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.A.; Jones, C.H.; Welch, V.; True, J.M. Outlook of pandemic preparedness in a post-COVID-19 world. npj Vaccines 2023, 8, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, B.; Carius, B.M.; Chavez, S.; Liang, S.Y.; Brady, W.J.; Koyfman, A.; Gottlieb, M. Clinical update on COVID-19 for the emergency clinician: Presentation and evaluation. Am J Emerg Med 2022, 54, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Madhavan, M.V.; Sehgal, K.; Nair, N.; Mahajan, S.; Sehrawat, T.S.; Bikdeli, B.; Ahluwalia, N.; Ausiello, J.C.; Wan, E.Y.; et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med 2020, 26, 1017–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, L.K.; Deadwiler, B.; Haratian, A.; Bolia, I.K.; Weber, A.E.; Petrigliano, F.A. Effects of COVID-19 on the Musculoskeletal System: Clinician's Guide. Orthop Res Rev 2021, 13, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, P.; Patel, K.; Pinto, C.; Jaiswal, R.; Tirupathi, R.; Pillai, S.; Patel, U. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PCS) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL)-A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Virol 2022, 94, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Leon, S.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Perelman, C.; Sepulveda, R.; Rebolledo, P.A.; Cuapio, A.; Villapol, S. More than 50 Long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizarro-Pennarolli, C.; Sánchez-Rojas, C.; Torres-Castro, R.; Vera-Uribe, R.; Sanchez-Ramirez, D.C.; Vasconcello-Castillo, L.; Solís-Navarro, L.; Rivera-Lillo, G. Assessment of activities of daily living in patients post COVID-19: a systematic review. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, M.; Kasai, F.; Kawate, N. The Impact of Isolation on Elderly Patients with Mild to Moderate COVID-19. Prog Rehabil Med 2022, 7, 20220032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutos, M.L.; Cruzado, D.P.; Lunsford, D.; Orza, S.G.; Cantero-Téllez, R. Impact of Social Isolation Due to COVID-19 on Daily Life Activities and Independence of People over 65: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amdal, C.D.; Pe, M.; Falk, R.S.; Piccinin, C.; Bottomley, A.; Arraras, J.I.; Darlington, A.S.; Hofsø, K.; Holzner, B.; Jørgensen, N.M.H.; et al. Health-related quality of life issues, including symptoms, in patients with active COVID-19 or post COVID-19; a systematic literature review. Qual Life Res 2021, 30, 3367–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nshimirimana, D.A.; Kokonya, D.; Gitaka, J.; Wesonga, B.; Mativo, J.N.; Rukanikigitero, J.M.V. Impact of COVID-19 on health-related quality of life in the general population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS Glob Public Health 2023, 3, e0002137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Duru, E.E.; Weir, P.; Lee, S. Long COVID Is Associated with Decreased Quality of Life and Increased Mental Disability. COVID 2024, 4, 1719–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soril, L.J.J.; Damant, R.W.; Lam, G.Y.; Smith, M.P.; Weatherald, J.; Bourbeau, J.; Hernandez, P.; Stickland, M.K. The effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation for Post-COVID symptoms: A rapid review of the literature. Respir Med 2022, 195, 106782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pozas, O.; Meléndez-Oliva, E.; Rolando, L.M.; Rico, J.A.Q.; Corbellini, C.; Sánchez Romero, E.A. The pulmonary rehabilitation effect on long covid-19 syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiother Res Int 2024, 29, e2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Dai, B.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.; Hou, H.; Song, D.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Zhao, H.; et al. Effect of pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with long COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2025, 19, 17534666251323482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez-Oliva, E.; Martínez-Pozas, O.; Cuenca-Zaldívar, J.N.; Villafañe, J.H.; Jiménez-Ortega, L.; Sánchez-Romero, E.A. Efficacy of Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Post-COVID-19: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomedicines 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruit, M.A.; Holland, A.E.; Singh, S.J.; Tonia, T.; Wilson, K.C.; Troosters, T. COVID-19: interim guidance on rehabilitation in the hospital and post-hospital phase from a European Respiratory Society- and American Thoracic Society-coordinated international task force. Eur Respir J 2020, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.; Baldwin, C.; Bissett, B.; Boden, I.; Gosselink, R.; Granger, C.L.; Hodgson, C.; Jones, A.Y.; Kho, M.E.; Moses, R.; et al. Physiotherapy management for COVID-19 in the acute hospital setting: clinical practice recommendations. J Physiother 2020, 66, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitacca, M.; Carone, M.; Clini, E.M.; Paneroni, M.; Lazzeri, M.; Lanza, A.; Privitera, E.; Pasqua, F.; Gigliotti, F.; Castellana, G.; et al. Joint Statement on the Role of Respiratory Rehabilitation in the COVID-19 Crisis: The Italian Position Paper. Respiration 2020, 99, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jianramas, N.; Semphuet, T.; Nissapatorn, V.; Sivakorn, C.; Pereira, M.L.; Ratnarathon, A.C.; Salesingh, C.; Jaiyen, E.; Chaiyakul, S.; Piya-Amornphan, N.; et al. Effects of Different Bedside Physiotherapy Frequencies in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients, Focusing on Mild to Moderate Cases. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2025, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piquet, V.; Luczak, C.; Seiler, F.; Monaury, J.; Martini, A.; Ward, A.B.; Gracies, J.M.; Motavasseli, D. Do Patients With COVID-19 Benefit from Rehabilitation? Functional Outcomes of the First 100 Patients in a COVID-19 Rehabilitation Unit. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2021, 102, 1067–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.M.; Xie, Y.X.; Wang, C. Recommendations for respiratory rehabilitation in adults with coronavirus disease 2019. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020, 133, 1595–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, A.E.; Malaguti, C.; Hoffman, M.; Lahham, A.; Burge, A.T.; Dowman, L.; May, A.K.; Bondarenko, J.; Graco, M.; Tikellis, G.; et al. Home-based or remote exercise testing in chronic respiratory disease, during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: A rapid review. Chron Respir Dis 2020, 17, 1479973120952418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha Niyogi, S.; Agarwal, R.; Suri, V.; Malhotra, P.; Jain, D.; Puri, G.D. One minute sit-to-stand test as a potential triage marker in COVID-19 patients: A pilot observational study. Trends Anaesth Crit Care 2021, 39, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellone, F.; Tisano, A.; Leonardi, G.; Amato, D.; Borzelli, D.; Santoro, G.; Alito, A.; Cucinotta, F.; Portaro, S. Lesson from COVID-19-Adapting Respiratory Rehabilitation Through Early Multidisciplinary Care: An Opinion Paper from Retrospective Data. J Clin Med 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blitshteyn, S.; Whitelaw, S. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) and other autonomic disorders after COVID-19 infection: a case series of 20 patients. Immunol Res 2021, 69, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmam, I.; Dubé, M.O.; Zahouani, I.; Ramos, A.; Desmeules, F.; Best, K.L.; Roy, J.S. The impact of long COVID on physical and cardiorespiratory parameters: A systematic review. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0318707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daynes, E.; Gerlis, C.; Briggs-Price, S.; Jones, P.; Singh, S.J. COPD assessment test for the evaluation of COVID-19 symptoms. Thorax 2021, 76, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd-Evans, P.H.I.; Baldwin, M.M.; Daynes, E.; Hong, A.; Mills, G.; Goddard, A.C.N.; Chaplin, E.; Gardiner, N.; Singh, S.J. Early experiences of the Your COVID Recovery(®) digital programme for individuals with long COVID. BMJ Open Respir Res 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorman-Ilan, S.; Hertz-Palmor, N.; Brand-Gothelf, A.; Hasson-Ohayon, I.; Matalon, N.; Gross, R.; Chen, W.; Abramovich, A.; Afek, A.; Ziv, A.; et al. Anxiety and Depression Symptoms in COVID-19 Isolated Patients and in Their Relatives. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11, 581598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, M.; Sacerdote, C.; Ciccone, G.; Donarelli, E.; Kogevinas, M.; Rasulo, A.; Toscano, A.; Pagano, E.; Rosato, R. Long-term physical and mental Health-Related Quality of Life in Italian patients post COVID-19 hospitalisation. Qual Life Res 2025, 34, 1103–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).