Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUBMC | American University of Beirut Medical Center |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| DTR | Difficult to treat |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| MDR | Multidrug-resistant |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| PA | Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| PAB | Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia |

| SD | Standard deviation |

References

- Tam, V.H., Rogers, C.A., Chang, K.T., Weston, J.S., Caeiro J.P., Garey K.W. Impact of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia on patient outcomes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010, 54, 3717-22. [CrossRef]

- Alhussain, F.A., Yenugadhati, N., Al Eidan, F.A., Al Johani, S., Badri, M. Risk factors, antimicrobial susceptibility pattern and patient outcomes of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection: A matched case-control study. J Infect Public Health 2021, 14, 152-7. [CrossRef]

- Rojas, A., Palacios-Baena, Z.R., Lopez-Cortes L.E., Rodriguez-Bano, J. Rates, predictors and mortality of community-onset bloodstream infections due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019, 25, 964-970. [CrossRef]

- Thaden, J.T., Park, L.P., Maskarinec S.A., Ruffin F., Fowler Jr, V.G., van Duin, D. Results from a 13-Year Prospective Cohort Study Show Increased Mortality Associated with Bloodstream Infections Caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa Compared to Other Bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017, 61, e02671-16. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H., Su, T.Y., Ye, J.J., Hsu, P.C., Kuo A.J., Chia J.H., Lee, M.H. Risk factors and clinical significance of bacteremia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant only to carbapenems. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2017, 50, 677-83. [CrossRef]

- Migiyama, Y., Yanagihara, K., Kaku, N., Harada, Y., Yamada, K., Nagaoka, K., Morinaga, Y., Akamatsu, N., Matdusda, J., Izumikawa, K., Kohrogi, H., Kohno, S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Bacteremia among Immunocompetent and Immunocompromised Patients: Relation to Initial Antibiotic Therapy and Survival. Jpn J Infect Dis 2016, 69, 91-6. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, K.L., Paterson, D.L. Community-acquired Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection: a classification that should not falsely reassure the clinician. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2017, 36, 703-11. [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E., Carrara, E., Savoldi, A., Harbarth, S., Mendelson, M., Monnet, D.L., Pulcini, C., et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, 318-27. [CrossRef]

- Raman, G., Avendano, E.E., Chan, J., Merchant, S., Puzniak, L. Risk factors for hospitalized patients with resistant or multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2018, 7, 79. [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z., Raudonis, R., Glick, B.R., Lin, T.J., Cheng, Z. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: mechanisms and alternative therapeutic strategies. Biotechnol Adv 2019, 37, 177-92. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, E., Gastmeier, P., Deja, M., Schwab, F. Antibiotic consumption and resistance: data from Europe and Germany. Int J Med Microbiol 2013, 303, 388-95.

- Sindeldecker, D., Stoodley, P. The many antibiotic resistance and tolerance strategies of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biofilm 2021, 3, 100056. [CrossRef]

- Hancock, R.E. Resistance mechanisms in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other nonfermentative gram-negative bacteria. Clin Infect Dis 1998, 27, S93-9. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, M., Anju, C.P., Biswas, L., Kumar, V.A., Mohan, C.G., Biswas, R. Antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and alternative therapeutic options. Int J Med Microbiol 2016, 306, 48-58. [CrossRef]

- Breidenstein, E.B., de la Fuente-Núñez, C., Hancock R.E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: all roads lead to resistance. Trends Microbiol 2011, 19, 419-26. [CrossRef]

- Soares, A., Alexandre, K., Etienne, M. Tolerance and persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in biofilms exposed to antibiotics: molecular mechanisms, antibiotic strategies and therapeutic perspectives. Front Microbiol 2020, 11, 2057. [CrossRef]

- Cigana, C., Bernardini, F., Facchini, M., Alcala-Franco, B., Riva, C., De Fino, I., Rossi, A., et al. Efficacy of the novel antibiotic POL7001 in preclinical models of Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016, 60, 4991-5000. [CrossRef]

- El-Herte, R.I., Kanj, S.S., Matar, G.M., Araj, G.F. The threat of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Lebanon: an update on the regional and local epidemiology. J Infect Public Health 2012, 5, 233-43. [CrossRef]

- Abbara, A., Rawson, T.M., Karah, N., El-Amin W., Hatcher, J., Tajaldin, B.Dar, O., et al. Antimicrobial resistance in the context of the Syrian conflict: drivers before and after the onset of conflict and key recommendations. Int J Infect Dis 2018, 73, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Osman, M., Halimeh, F.B., Rafei, R., Mallat, H., El Tom, J., Raad, E.B., Diene, S.M., et al. Investigation of an XDR-Acinetobacter baumannii ST2 outbreak in an intensive care unit of a Lebanese tertiary care hospital. Future Microbiol 2020, 15, 1535-42. [CrossRef]

- Dabbousi, A.A., Dabboussi, F., Hamze, M., Osman, M., Kassem, I.I. The emergence and dissemination of multidrug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Lebanon: current status and challenges during the economic crisis. Antibiotics (Basel) 2022, 11, 687. [CrossRef]

- Sakr, S., Ghaddar, A., Hamam, B., Sheet, I. Antibiotic use and resistance: An unprecedented assessment of university students’ knowledge, attitude and practices (KAP) in Lebanon. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 535. [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, E.B., Cottreau, J.M., Chang, K.T., Caeiro, J.P., Johnson, M.L., Tam, V.H. A model to predict mortality following Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2012, 72, 97-102. [CrossRef]

- Teelucksingh, K., Shaw., E. Clinical characteristics, appropriateness of empiric antibiotic therapy, and outcome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia across multiple community hospitals. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2022, 41, 53-62. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.K., Kim, H.A., Ryu, S.Y., Lee, E.J., Lee, M.S., Kim, J., Park, S.Y., et al. Tree-structured survival analysis of patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: A multicenter observational cohort study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2017, 87, 180-7. [CrossRef]

- Joo, E.J., Kang, C.I., Ha, Y.E., Park, S.Y., Kang, S.J., Wi, Y.M., Lee, N.Y., et al. Impact of inappropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy on outcome in Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemia: a stratified analysis according to sites of infection. Infection 2011, 39, 309-18. [CrossRef]

- Parkins, M.D., Gregson, D.B., Pitout, J.D., Ross, T., Laupland, K.B. Population-based study of the epidemiology and the risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection. Infection 2010, 38, 25-32. [CrossRef]

- Moghnieh, R.A., Kanafani, Z.A., Tabaja, H.Z., Sharara, S.L., Awad, L.S., Kanj, S.S. Epidemiology of common resistant bacterial pathogens in the countries of the Arab league. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, e379-94. [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.I., Kim, S.H., Kim, H.B., Park, S.W., Choe, Y.J., Oh, M.D., Kim, E.C., et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: risk factors for mortality and influence of delayed receipt of effective antimicrobial therapy on clinical outcome. Clin Infect Dis 2003, 37, 745-51. [CrossRef]

- Babich, T., Naucler, P., Valik, J.K., Giske, C.G., Benito, N., Cardona, R., Rivera, A., et al. Risk factors for mortality among patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemia: a retrospective multicentre study. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020, 55, 105847. [CrossRef]

- Lodise, T.P. Jr, Patel, N., Kwa, A., Graves, J., Furuno, J. P., Graffunder, E., Lomaestro, B. et al. Predictors of 30-day mortality among patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections: impact of delayed appropriate antibiotic selection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2007, 51, 3510-5. [CrossRef]

- Furtado, G.H., Bergamasco, M.D., Menezes, F.G., Marques, D., Silva, A., Perdiz, L.B., Wey, S.B. et al. Imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection at a medical surgical intensive care unit: risk factors and mortality. J Crit Care 2009, 24, 625.e9-14. [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.I., Chung, D.R., Peck, K.R., Song, J.H. Clinical predictors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Acinetobacter baumannii bacteremia in patients admitted to the ED. Am J Emerg Med 2012, 30, 1169-75. [CrossRef]

- Hilf, M., Yu, V.L., Sharp, J., Zuravleff, J.J., Korvick, J.A., Muder, R.R. Antibiotic therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: outcome correlations in a prospective study of 200 patients. Am J Med 1989, 87, 540-6. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y., Chen, X.L., Huang, A.W., Liu S.L., Liu, W.J., Zhang, N., Lu X.Z. Mortality attributable to carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Emerg Microbes Infect 2016, 5, e27. [CrossRef]

- Peña, C., Suarez, C., Ocampo-Sosa, A., Murillas, J., Almirante, B., Pomar, V., Aguilar, M. et al. Effect of adequate single-drug vs combination antimicrobial therapy on mortality in Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections: a post Hoc analysis of a prospective cohort. Clin Infect Dis 2013, 57, 208-16. [CrossRef]

- Aviv, T., Lazarovitch, T., Katz, D., Zaidenstein, R., Dadon, M., Daniel, C., Tal-Jasper, R. et al. The epidemiological impact and significance of carbapenem resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections: a matched case-case-control analysis. Infect Control Hospital Epidemiol 2018, 39, 1262-5. [CrossRef]

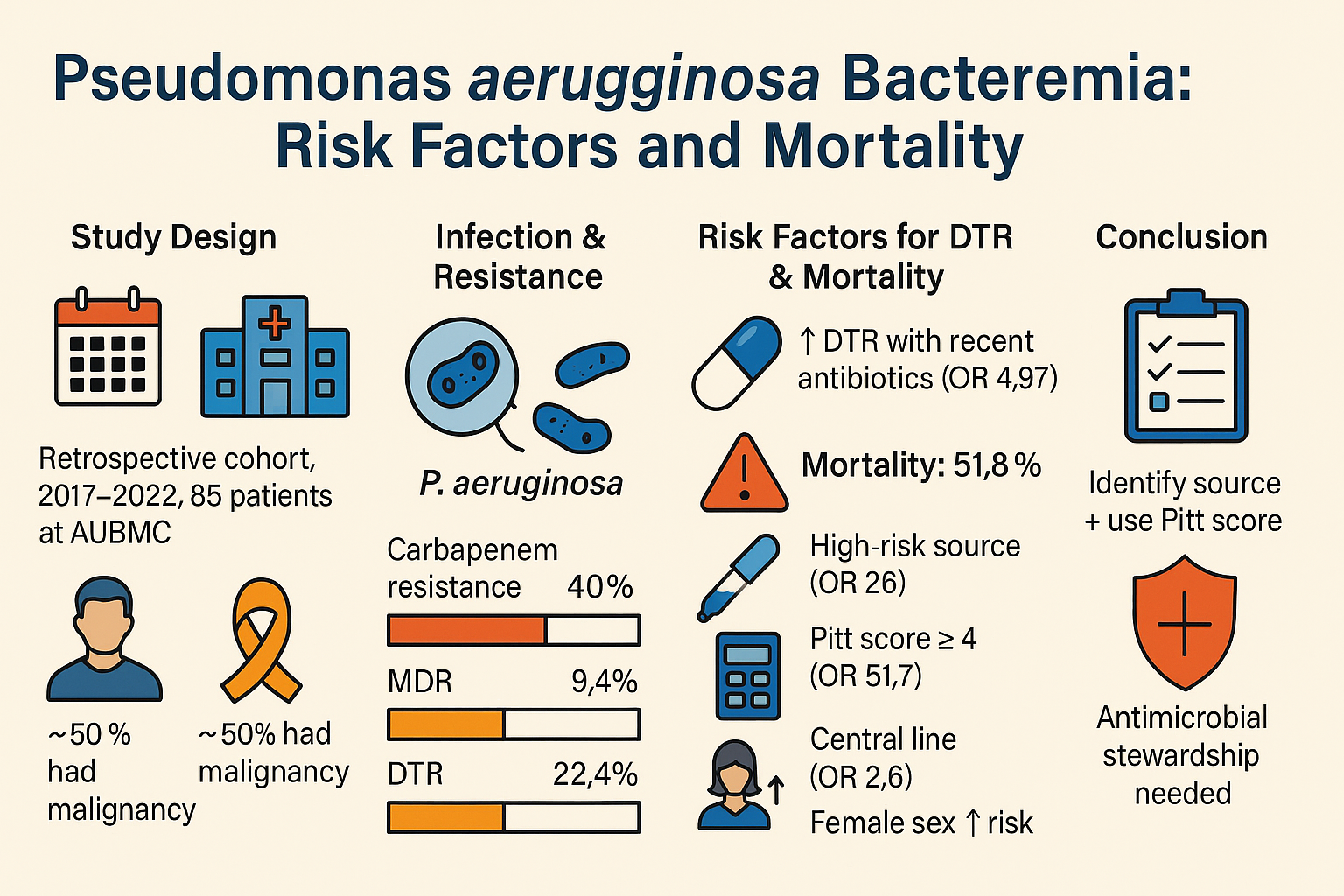

| Characteristic | Value (N = 85) |

|---|---|

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 64.5 ± 16.8 |

| Male sex | 60 (70.6) |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 27.6 ± 5.4 |

| Malignancy | 41 (48.2) |

| Solid | 23 (27.1) |

| Hematologic | 18 (21.2) |

| Diabetes | 27 (31.8) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 14 (16.5) |

| Hemodialysis | 6 (7.1) |

| COPD | 6 (7.1) |

| Burn injury | 3 (3.5) |

| HIV infection | 2 (2.4) |

| Hospital stay > 2 days* | 69 (81.2) |

| ICU stay > 2 days* | 45 (52.9) |

| Mechanical ventilation > 2 days* | 37 (43.5) |

| Central line > 2 days* | 56 (65.9) |

| Urinary catheter > 2 days* | 43 (50.6) |

| Nasogastric tube > 2 days* | 36 (42.4) |

| Steroid use* | 47 (55.3) |

| Surgery* | 21 (24.7) |

| Clean | 7 (8.2) |

| Clean-contaminated/contaminated | 14 (16.5) |

| Route of acquisition | |

| Hospital-acquired | 67 (78.8) |

| Community-acquired | 12 (14.1) |

| Healthcare-associated | 6 (7.1) |

| Pitt Bacteremia Score > 4 | 44 (51.8) |

| Complications | Frequency (N = 85) |

|---|---|

| Sepsis | 69 (81.2) |

| ICU admission | 54 (63.5) |

| Septic shock | 49 (57.6) |

| Acute renal failure | 48 (56.5) |

| Hospital-acquired infection | 45 (52.9) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 43 (50.6) |

| Cardiovascular event | 30 (35.3) |

| Persistence/progression of the infection | 29 (34.1) |

| Recurrent infection | 19 (22.4) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 9 (10.6) |

| Persistent bacteremia | 6 (7.1) |

| Cerebrovascular event | 5 (5.9) |

| Systemic embolism | 1 (1.2) |

| Variable | Unadjusted OR | p-Value | Adjusted OR | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pitt bacteremia score ≥ 4 | 28.2 | < 0.01 | 51.7 | < 0.01 |

| High-risk source† | 24.3 | < 0.01 | 26.0 | < 0.01 |

| Central line* | 6.0 | 0.02 | 2.6 | 0.03 |

| Male sex | 3.7 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.04 |

| COPD | 6.0 | 0.01 | ||

| Steroid use* | 8.5 | < 0.01 | ||

| Hospital stay* | 8.6 | < 0.01 | ||

| ]ICU stay* | 8.7 | < 0.01 | ||

| Mechanical ventilation* | 7.9 | < 0.01 | ||

| Route of acquisition | 5.7 | 0.02 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).