Submitted:

09 July 2025

Posted:

10 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Data Collection Process

2.6. Study Risk of Bias Assessment

2.7. Effect Measures and Synthesis Methods

2.8. Certainty Assessment

3. Results

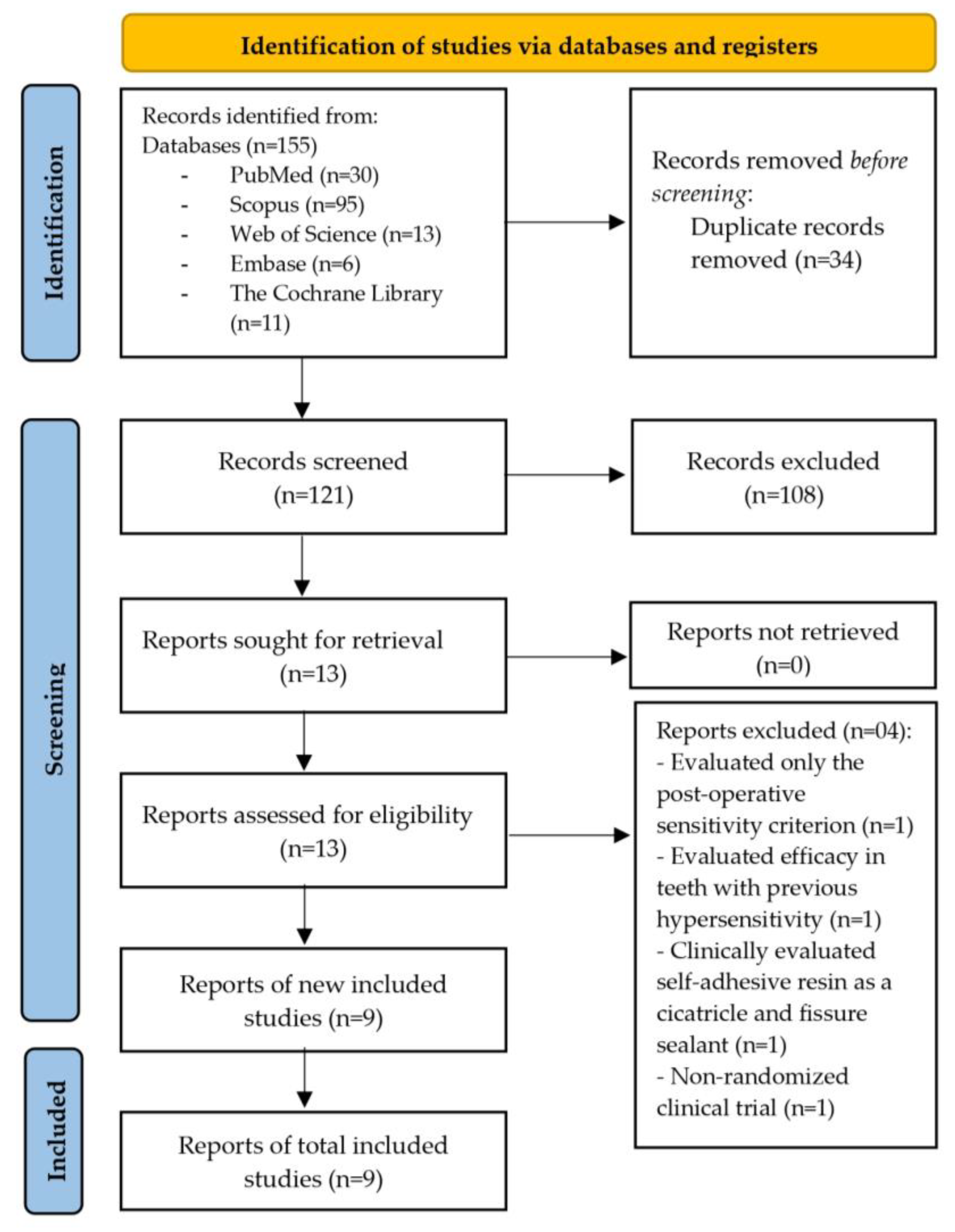

3.1. Study Selection

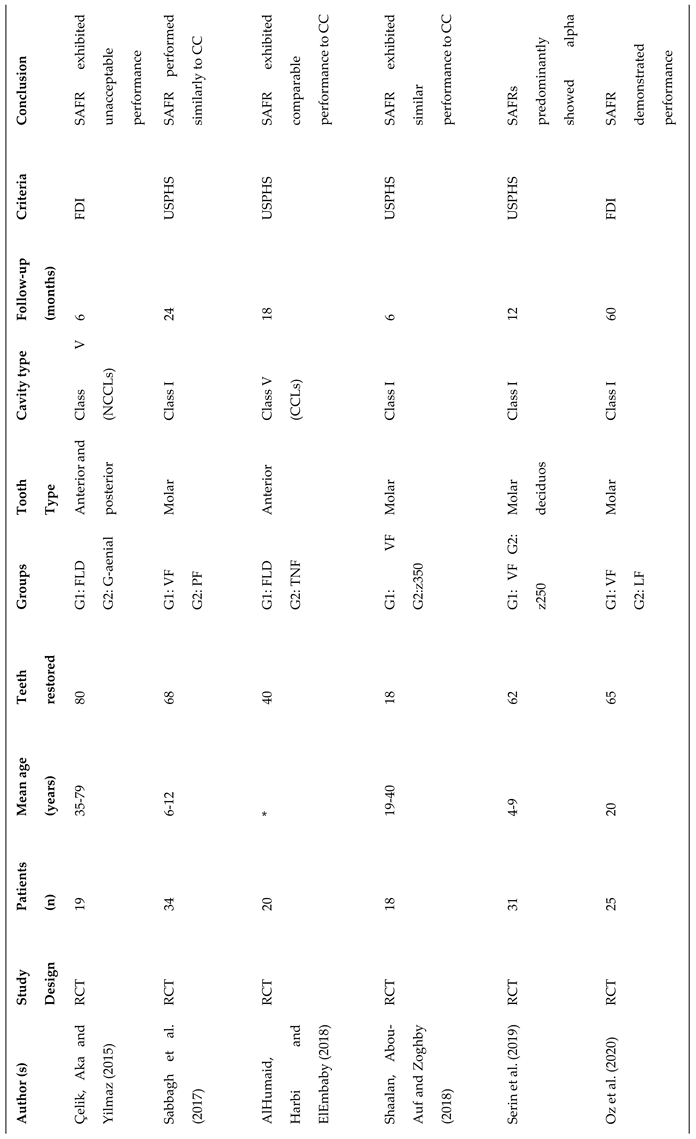

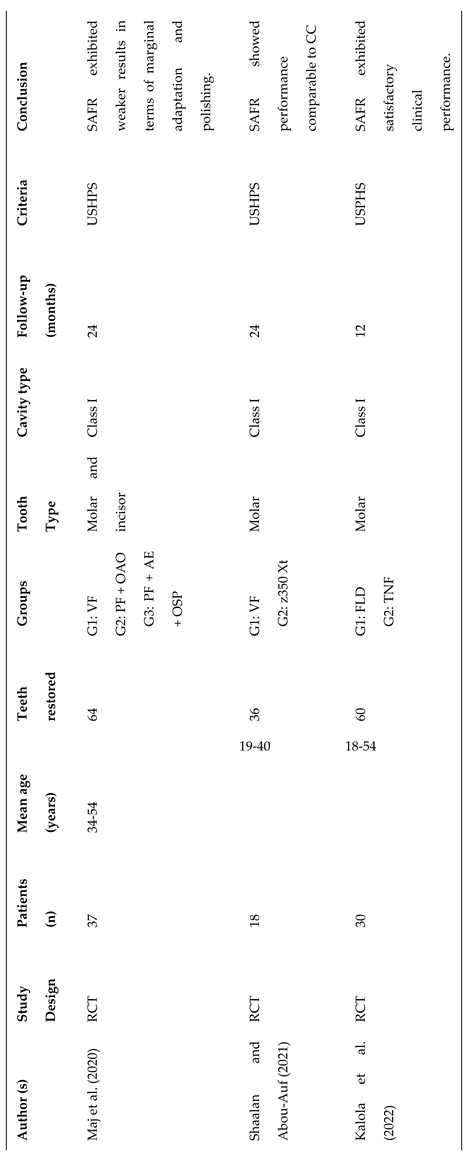

3.2. Study Characteristics

3.3. Risk of Bias in Studies

3.4. Results of Syntheses

3.5. Certainty of Evidence

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Miletic, V. Development of Dental Composites. Dental Composite Materials for Direct Restorations 2018, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, J.M.A.S.; da Silva, L.E.E.; Souza, C.C.B.; et al. Utilização de resinas compostas em dentes anteriores REAS 2021, 132, 1-7.

- David, C., Cardoso de Cardoso, G.; Isolan, C.P., Piva, E.; Moraes, R.R., Cuevas-Suarez, C.E. Bond strength of self-adhesive flowable composite resins to dental tissues: A systematic review and meta-analysis of in vitro studies. J Prosthet Dent 2022, 128, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, J.; Rizk, M.; Hoch, M.; Wiegand, A. Bonding performance of self-adhesive flowable composites to enamel, dentin and a nano-hybrid composite. Odontology 2018, 106, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordehi, A.Y.; Shahabi, M.S.; Akbari, A. Comparison of self-adhering flowable composite microleakage with several types of bonding agent in class V cavity restoration. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2019, 16, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, P.; Goswami, M.; Singh, D. Comparative evaluation of shear bond strength and nanoleakage of conventional and self-adhering flowable composites to primary teeth dentin Contemp Clin Dent 2016, 7, 326-331.

- Sismanoglu, S. Efficiency of self-adhering flowable resin composite and different surface treatments in composite repair using a universal adhesive Niger J Clin Pract 2019, 22, 1675-1679.

- Kalola, A.V.; Sreejith, S.U.; Kanodia, S.; Parmar, A.; Iyer, J.V.; Parmar, G.J. Comparative clinical evaluation of a self-adhering flowable composite with conventional flowable composite in Class I cavity: An in vivo study. J Conserv Dent 2022, 25, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhwa, S.; Nayak, U.; Kappadi, D.; Prajapati, D.; Sharma, R.; Pawar, A. Comparative Clinical Evaluation of Resin-based Pit and Fissure Sealant and Self-adhering Flowable Composite: An In Vivo Study Int J Clin Pediatr Dent 2018, 11, 430-434.

- Mine, A.; De Munck, J.; Van Ende, A.; Poitevin, A.; Matsumoto, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Kuboki, T.; Van Landuyt, K.L.; Yatani, H.; Van Meerbeek, B. Limited interaction of a self-adhesive flowable composite with dentin/enamel characterized by TEM. Dent Mater 2017, 33, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brueckner, C.; Schneider, H.; Haak, R. Shear Bond Strength and Tooth-Composite Interaction With Self-Adhering Flowable Composites Oper Dent 2017, 42, 90-100.

- Gayatri, C.; Rambabu, T.; Sajjan, G.; Battina, P.; Priyadarshini, M.S.; Sowjanya, B.L. Evaluation of Marginal Adaptation of a Self-Adhering Flowable Composite Resin Liner: A Scanning Electron Microscopic Stud. Contemp Clin Dent 2013, 9, 1497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maj, A.; Trzcionka, A.; Twardawa, H.; Tanasiewicz, M. A comparative clinical study of the self-adhering flowable composite resin vertise flow and the traditional flowable composite resin premise flowable Coatings 2020, 10, 800.

- Abusamra, E.M.M.; Elsharkawy, M.M.; Mahmoud, E.M.; El Mahy, W.E.M. Clinical evaluation of self-adhering flowable composite in non-carious cervical lesion. Egypt 2016, 62, 757–764. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement PLoS Med 2009, 6, e1000097.

- Paolone, G.; Mazzitelli, C.; Josic, U.; Scotti, N.; Gherlone, E.; Cantatore, G.; Breschi, L. Modeling Liquids and Resin-Based Dental Composite Materials-A Scoping Review Materials (Basel) 2022, 15, 3759.

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan — a web and mobile app for systematic reviews Systematic Reviews 2016, 5, 210.

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Green, S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Cochrane Training 2008. Available online: https://training.cochrane.

- de Oliveira, N.G.; Lima, A.S.L.C.; da Silveira, M.T.; de Souza Araújo, P.R.; Monteiro, G.Q.d.M; de Vasconcelos, M.C. Evaluation of postoperative sensitivity in restorations with self-adhesive resin: a randomized split-mouth design-controlled study Clin Oral Investig 2020, 24, 1829-1835.

- Pinna, R.; Bortone, A.; Sotgiu, G.; Dore, S.; Usai, P.; Milia, E. Clinical evaluation of the efficacy of one self-adhesive composite in dental hypersensitivity Clin Oral Investig 2015, 19, 1663-72.

- Çelik, E.U.; Aka, B.; Yilmaz, F. Six-month Clinical Evaluation of a Self-adhesive Flowable Composite in Noncarious Cervical Lesions J Adhes Dent 2015, 17, 361-8.

- Sabbagh, J.; Dagher, S.; El Osta, N.; Souhaid, P. Randomized Clinical Trial of a Self-Adhering Flowable Composite for Class I Restorations: 2-Year Results. Int J Dent 2017, 2017, 5041529. [Google Scholar]

- AlHumaid, J.; Al Harbi, F.A.; ElEmbaby, A.E. Performance of Self-adhering Flowable Composite in Class V Restorations: 18 Months Clinical Study J Contemp Dent Pract 2018, 19(7), 785-791.

- Shaalan, O.O.; Abou-Auf, E.; El Zoghby, A.F. Clinical evaluation of self-adhering flowable composite versus conventional flowable composite in conservative Class I cavities: Randomized controlled trial J Conserv Dent 2018, 21, 485-490.

- Serin, B.A.; Yazicioglu, I.; Deveci, C.; Dogan, M.C. Clinical evaluation of a self-adhering flowable composite as occlusal restorative material in primary molars: one-year results Eur Oral Res 2019, 53, 119-124.

- Oz, F.D.; Ergin, E.; Cakir, F.Y.; Gurgan, S. Clinical Evaluation of a Self-Adhering Flowable Resin Composite in Minimally Invasive Class I Cavities: 5-year Results of a Double Blind Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial Acta Stomatol Croat 2020, 54, 10-21.

- Shaalan, O.O.; Abou-Auf, E. A 24-Month Evaluation of Self-Adhering Flowable Composite Compared to Conventional Flowable Composite in Conservative Simple Occlusal Restorations: A Randomized Clinical Trial Contemp Clin Dent 2021, 12, 368-375.

- Brueckner, C.; Schneider, H.; Haak, R. Shear Bond Strength and Tooth-Composite Interaction With Self-Adhering Flowable Composites Oper Dent 2017, 42, 90-100.

- Vertise Flow Instructions for Use Kerr. [(accessed on 06 December 2024)]. Available online: https://www.ultimatedental.com/uploads/KaVoKerr-VertiseFlowIFU.pdf.

- Fusion Liquid Dentin Instructions for Use Pentrol Clinical Technologies. [(accessed on 06 December 2024)]. Available online: https://docplayer.net/167674922-Liquid-dentin-a-fusion-of-composite-adhesive-technology.html.

- Hickel, R.; Roulet, J.F.; Bayne, S.; Heintze, S.D.; Mjör, I.A.; Peters, M.; Rousson, V.; Randall, R.; Schmalz, G.; Tyas, M.; Vanherle, G. Recommendations for conducting controlled clinical studies of dental restorative materials Clin Oral Investig 2007, 11, 5-33.

- Valizadeh, S.; Asiaie, Z.; Kiomarsi, N.; Kharazifard, M.J. Color stability of self-adhering composite resins in different solutions Dent Med Probl 2020, 57, 31-38.

- Marquillier, T.; Doméjean, S.; Le Clerc, J.; Chemla, F.; Gritsch, K.; Maurin, J. C.; Millet, P.; Pérard, M.; Grosgogeat, B.; Dursun, E. The use of FDI criteria in clinical trials on direct dental restorations: A scoping review. J Dent 2018, 68, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshinawy, F.M.; Abu, A.E.; Khallaf, Y.S. Evaluation Of Clinical Performance Of Self-Adhering Flowable Composite Vs Conventional Flowable Composite In Cervical Carious Lesions: A Randomized Clinical Trial ADJC 2023, 5, 186-194.

- Arbildo-Vega, H.I.; Lapinska, B.; Panda, S. Clinical Effectiveness of Bulk-Fill and Conventional Resin Composite Restorations: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizi, F.; Ezoji, F.; Khafri, S.; Esmaeili, B. Surface Micro-Hardness and Wear Resistance of a Self-Adhesive Flowable Composite in Comparison to Conventional Flowable Composites Front Dent 2023, 20, 10.

- Veloso, S.R.M.; Lemos, C.A.A.; de Moraes, S.L.D.; Vasconcelos, B.C.d.E.; Pellizzer, E.P.; Monteiro, G.Q.d.M. Clinical performance of bulk-fill and conventional resin composite restorations in posterior teeth: a systematic review and meta-analysis Clin Oral Investig 2019, 23, 221-233.

| Database | Search strategy |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (Self-Adhesive Composite) OR (Self-Adhering Composite) OR (Self-Adherent Composite) AND (Restorations, Permanent Dental) OR (Restoration, Permanent Dental) OR (Dental Permanent Fillings) OR (Dental Permanent Filling) AND (Flowable hybrid composite) OR (flowable composite) OR (flowline) |

| Embase | ‘Self-Adhesive Composite’ OR ‘Self-Adhering Composite’ OR ‘Self-Adherent Composite’ AND ‘dental restorarion’/exp OR ‘dental restotarion’ OR ‘Restorations, Permanent Dental’ OR ‘Restoration, Permanent Dental’ OR ‘Dental Permanent Fillings’ OR ‘Dental Permanent Filling’ AND ‘Flowable hybrid composite’/exp ‘Flowable hybrid composite’ OR ‘flowable composite’ OR ‘flowline’ |

| Web of Science | TS= ((Self-Adhesive Composite) OR (Self-Adhering Composite) OR (Self-Adherent Composite)) AND TS= ((Restorations, Permanent Dental) OR (Restoration, Permanent Dental) OR (Dental Permanent Fillings) OR (Dental Permanent Filling)) AND TS= ((Flowable hybrid composite) OR (flowable composite) OR (flowline)) |

| The Cochrane Library | (Self-Adhesive Composite OR Self-Adhering Composite OR Self-Adherent Composite) AND (Restorations, Permanent Dental OR Restoration, Permanent Dental OR Dental Permanent Fillings OR Dental Permanent Filling) AND (Flowable hybrid composite OR Flowable composite OR flowline) |

| Scopus | ‘Restorations, AND permanent AND dental’ OR ‘restoration, AND permanent AND dental’ OR ‘dental AND permanent AND fillings’ OR ‘dental AND permanent AND filling' AND ‘self-adhesive AND composite’ OR ‘self-adhering’ AND composite’ OR ‘self-adherent AND composite' AND ‘Flowable hybrid composite’ OR ‘flowable composite’ OR ‘flowline’ |

| The USPHS criteria |

|---|

|

Retention Alpha (A): Restoration is present. Delta (D): Restoration is partially or totally missing. Color match Alpha (A): The restoration matches the adjacent tooth tissue in color, shade, or translucency. Bravo (B): There is a slight mismatch in color, shade, or translucency, but within the normal range of adjacent tooth structure. Charlie (C): There is a slight mismatch in color, shade, or translucency, but outside of the normal range of adjacent tooth structure. |

|

Marginal discoloration Alpha (A): There is discoloration anywhere along the margin between the restoration and the adjacent tooth structure. Bravo (B): Discoloration is present, but has not penetrated along the margin in a pulpal direction. Charlie (C): Discoloration has penetrated along the margin in a pulpal direction. |

|

Recurrent caries Alpha (A): No caries are present at the margin of the restoration, as evidenced by softness, opacity, or etching at the margin. Bravo (B): There is evidence of caries at the margin of the restoration. |

|

Surface roughness Alpha (A): The restoration surface is as smooth as surrounding enamel. Bravo (B): The restoration surface is rougher than the surrounding enamel. Charlie (C): Surface pitting is sufficiently coarse to inhibit the continuous movement of an explorer across the surface. |

|

Marginal integrity Alpha (A): There is no visible evidence of a crevice along the margin into which the explorer penetrates. Bravo (B): There is visible evidence of a crevice along the margin into which the explorer penetrates or catches. Charlie (C): The explorer penetrates the crevice, and dentin or base is exposed. Delta (D): The restoration is mobile, or missing, either in part or total. |

|

Postoperative sensitivity Alpha (A): Normal reaction to cold spray compared with that of no restored teeth. Bravo (B): Increased cold sensitivity. Charlie (C): Spontaneous pain. Delta (D): Nonvital. |

| The FDI criteria |

|---|

|

Aesthetic properties

Surface gloss Score 1: Gloss similar to enamel. Score 2: Slightly opaque; Some isolated pores. Score 3: Opaque surface but acceptable if covered by saliva; Multiple pores in more than half of the surface. Score 4: Rough surface, where polishing is not sufficient. Score 5: Very rough surface, unacceptable. Staining Score 1: No superficial or marginal staining. Score 2: Minimal staining, easily removable. Score 3: Moderate staining, also present in other teeth and aesthetically acceptable. Score 4: Unacceptable staining in the restoration, intervention necessary. Score 5: Severe generalized or localized staining, without access for intervention. Color stability or translucency Score 1: Good coloration and translucency compared to neighboring teeth. Score 2: Minimal color and translucency deviation. Score 3: Clear deviation, but without affecting aesthetics. Score 4: Localized clinical deviation that can be corrected by repair. Score 5: Unacceptable, replacement necessary. Anatomic shape Score 1: Ideal shape. Score 2: Shape slightly deviates from normal. Score 3: Shape differs from normal but does not compromise aesthetics. Score 4: Shape is affected and aesthetically unacceptable. Intervention/correction is necessary. Score 5: Unacceptable or lost. Requires replacement. |

|

Functional properties

Fractures and retention Score 1: No fractures or cracks. Score 2: Small crack. Score 3: Cracks that do not affect marginal adaptation. Score 4: Chips that damage marginal adaptation or contact point. Score 5: Partial or total loss of the restoration. Marginal adaptation Score 1: Harmonious line without gaps or discoloration. Score 2: Small marginal fracture removable with polishing. Score 3: Gap less than 150µm, not removable; Several small fractures in enamel and dentin. Score 4: Gap larger than 250 µm or exposed dentin; Chips damage margin; Noticeable fracture in enamel or dentin. Score 5: Large gaps or widespread irregularities. Anatomic shape Score 1: Normal contact point (dental floss or 25 µm metal foil can pass through; Normal contour. Score 2: Slightly too strong contact but without disadvantage (dental floss or 25 µm metal foil can only pass with pressure); Slightly deficient contour. Score 3: Somewhat weak contact, no indication of damage to the tooth, gum, or periodontal structures; 50 µm metal foil can pass; Visibly deficient contour. Score 4: Too weak and possible damage due to food impaction; 100 µm metal foil can pass; Inadequate contour; Repair possible. Score 5: Too weak and/or clear damage due to food impaction and/or pain/gingivitis; Insufficient contour, requires replacement. |

|

Biological properties

Post-operative sensitivity Score 1: No hypersensitivity; normal vitality. Score 2: Low hypersensitivity for a short period of time; normal vitality. Score 3: Moderate hypersensitivity; Weak sensitivity that does not require treatment. Score 4: Intense hypersensitivity; Negative sensitivity; intervention necessary, but no replacement. Score 5: Very intense, pulpitis or non-vital. Endodontics necessary and restoration replacement. Caries recurrence Score 1: No secondary or primary caries. Score 2: Small and localized; Demineralization. Score 3: Larger areas of lesion without dentin exposure. Score 4: Caries with cavitation. Score 5: Deep secondary caries or exposed dentin, not accessible for repair or restoration |

|

|

| Author, year | Conventional resin composite | Self-Adhering Resin Flowable | ||

| Failure | Total | Failure | Total | |

| Çelik, Aka and Yilmaz (2015) | Marginal adaptation (n=0) Retention (n=0) Post-operative sensibility (n=0) Marginal staining (n=0) Color Match (n=0) Secondary caries (n=0) Anatomical Form (n=0) |

40 40 40 40 40 40 40 |

Marginal adaptation (n=0) Retention (n=27) Post-operative sensibility (n=0) Marginal staining (n=0) Color Match (n=0) Secondary caries (n=0) Anatomical Form (n=0) |

13 40 13 13 10 13 13 |

| Sabbagh et al. (2017) |

* | * | ||

| AlHumaid, Harbi and ElEmbaby (2018) | Marginal adaptation (n=3) Marginal staining (n=1) Color match (n=2) Surface roughness (n=1) |

20 20 20 20 |

Marginal adaptation (n=0) Marginal staining (n=0) Color match (n=0) Surface roughness (n=0) |

20 20 20 20 |

| Shaalan, Abou-Auf and Zoghby (2018) | Marginal adaptation (n=0) Retention (n=0) Post-operative sensibility (n=0) Marginal Staining (n=0) Color Match (n=0) |

18 18 18 18 |

Marginal adaptation (n=0) Retention (n=0) Post-operative sensibility (n=0) Marginal Staining (n=0) Color Match (n=0) |

18 18 18 18 |

| Serin et al. (2019) | Retention (n=0) Post-operative sensibility (n=0) Marginal Staining (n=0) Anatomical form (n=0) |

29 29 29 29 |

Retention (n=0) Post-operative sensibility (n=0) Marginal Staining (n=0) Anatomical form (n=0) |

29 29 29 29 |

| Maj et al. (2020) | Retention (n=0) Marginal Staining (n=0) Color Match (n=0) Proper Smoothness (n=0) Anatomical form (n=0) |

22 22 22 22 22 |

Retention (n=1) Marginal Staining (n=0) Color Match (n=1) Proper Smoothness (n=0) Anatomical form (n=0) |

22 22 22 22 22 |

| Oz et al. (2020) | Marginal adaptation (n=0) Retention (n=1) Post-operative sensibility (n=0) Marginal staining (n=0) Color Match (n=0) Proper Smoothness (n=0) Secondary caries (n=0) |

24 24 24 24 24 24 24 |

Marginal adaptation (n=0) Retention (n=0) Post-operative sensibility (n=0) Marginal staining (n=0) Color Match (n=0) Proper Smoothness (n=0) Secondary caries (n=0) |

22 22 22 22 22 22 22 |

| Shaalan e Abou-Auf (2021) | Marginal adaptation (n=0) Marginal staining (n=0) Color Match (n=0) Proper Smoothness (n=0) Secondary caries (n=0) Anatomical Form (n=0) |

18 18 18 18 18 |

Marginal adaptation (n=0) Marginal staining (n=0) Color Match (n=0) Proper Smoothness (n=0) Secondary caries (n=0) Anatomical Form (n=0) |

18 18 18 18 18 |

| Kalola et al. (2022) | Retention (n=0) Post-operative sensibility (n=0) Marginal staining (n=0) Color Match (n=0) Surface roughness (n=0) Secondary caries (n=0) Anatomical Form (n=0) |

30 30 30 30 30 30 30 |

Retention (n=0) Post-operative sensibility (n=2) Marginal staining (n=0) Color Match (n=0) Surface roughness (n=0) Secondary caries (n=0) Anatomical Form (n=0) |

30 30 30 30 30 30 30 |

| Certainty assessment | № of patients | Effect | Certainty | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies | Study design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | SARFs | CFR | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute (95% CI) | ||

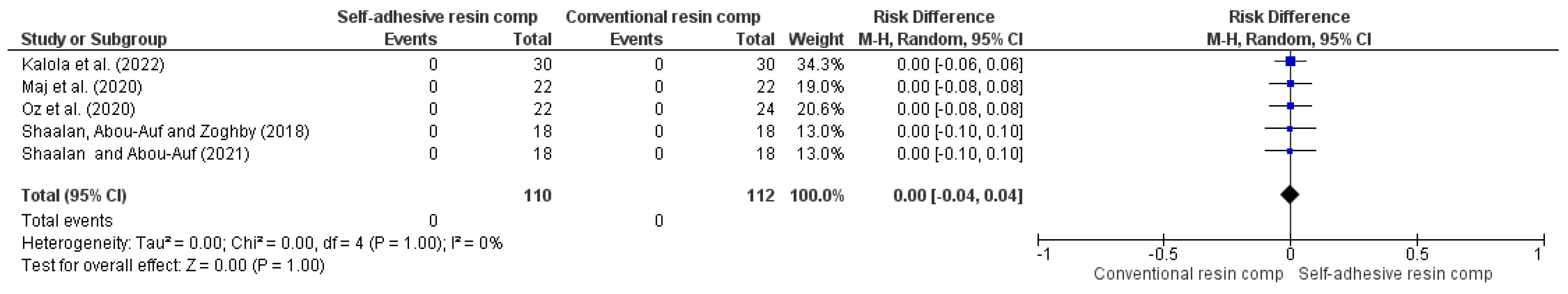

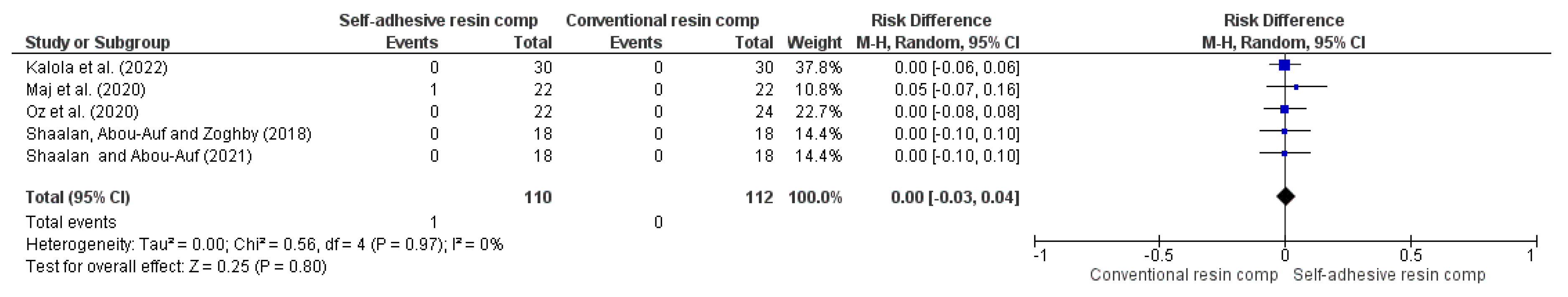

| Marginal Adaptation (follow-up: range 6 months to 5 years) | ||||||||||||

| 5 | RCT | NSa | NSb | NSc | NSd | VSAe | 0/110 (0.0%) | 0/112 (0.0%) | RR 0.00 (-0.04 to 0.04) | -- per 1.000 (from 0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | |

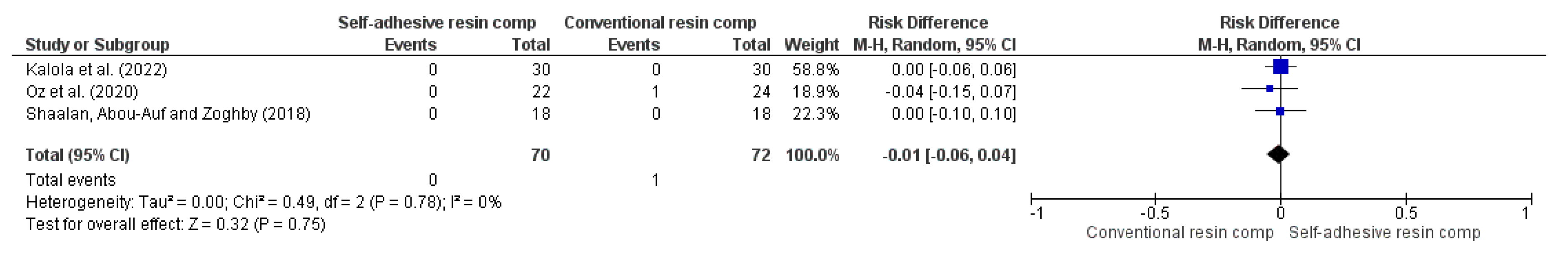

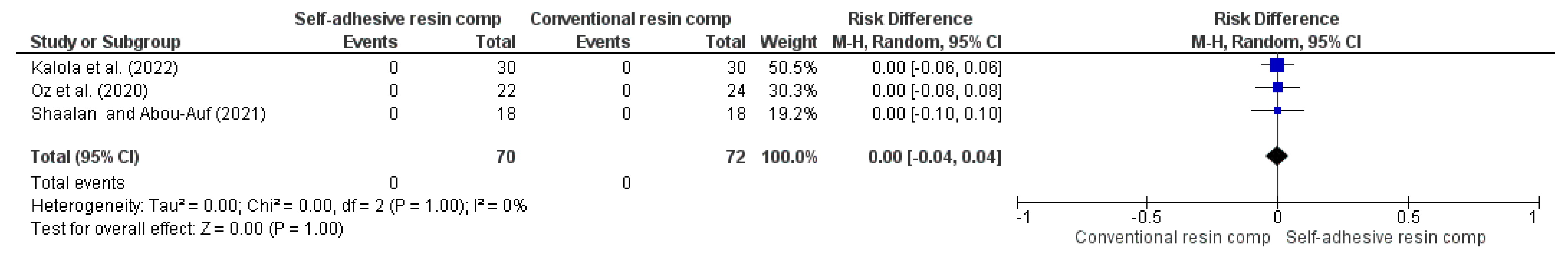

| Retention (follow-up: range 6 months to 5 years) | ||||||||||||

| 3 | RCT | NSe | NSb | NSc | NSd | VSAe | 0/70 (0.0%) | 1/72 (1.4%) | RR -0.01 (-0.06 to 0.04) | 14 fewer per 1.000 (from 15 fewer to 13 fewer) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | |

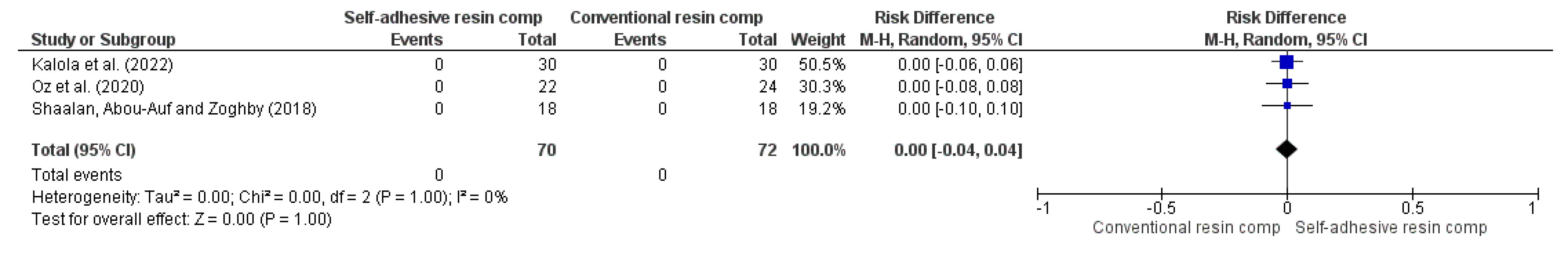

| Post-operative sensibility (follow-up: range 6 months to 5 years) | ||||||||||||

| 3 | RCT | NSe | NSb | NSc | NSd | VSAe | 0/70 (0.0%) | 0/72 (0.0%) | RR 0.00 (-0.04 to 0.04) | -- per 1.000 (from 0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | |

| Color match (follow-up: range 1 years to 5 years) | ||||||||||||

| 5 | RCT | NSa | NSb | NSc | NSd | VSAe | 1/110 (0.9%) | 0/112 (0.0%) | RR 0.00 (-0.03 to 0.04) | -- per 1.000 (from 0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | |

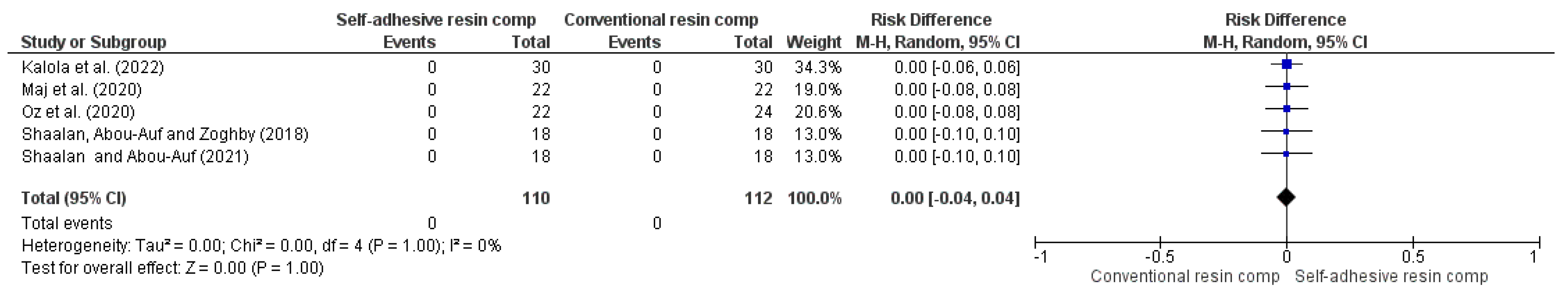

| Marginal descoloration (follow-up: range 6 months to 5 years) | ||||||||||||

| 5 | RCT | NS | NS | NS | NS | VSAe | 0/110 (0.0%) | 0/112 (0.0%) | RR 0.00 (-0.04 to 0.04) | -- per 1.000 (from 0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | |

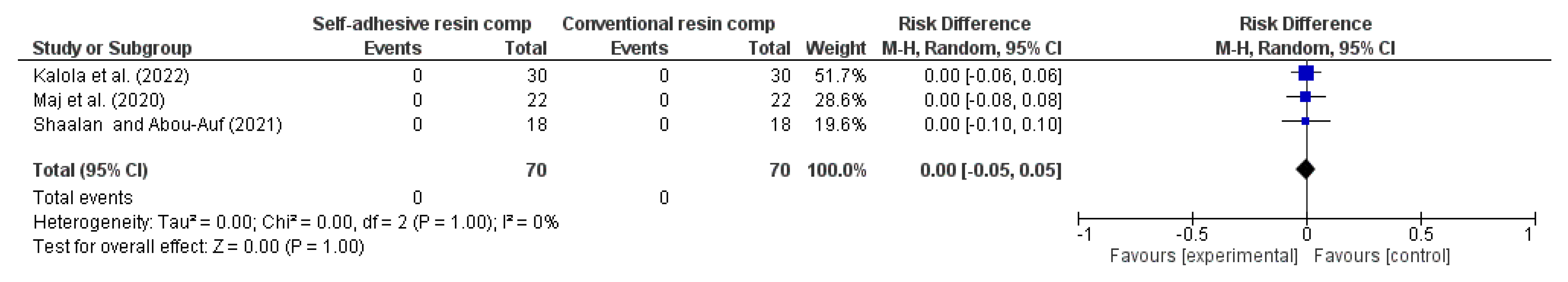

| Anatomic Form (follow-up: range 1 years to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 3 | RCT | NS | NS | NS | NS | VSAe | 0/70 (0.0%) | 0/70 (0.0%) | RR 0.00 (-0.05 to 0.05) | -- per 1.000 (from 0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | |

| Secondary caries (follow-up: range 1 years to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 3 | RCT | NS | NS | NS | NS | VSAe | 0/70 (0.0%) | 0/72 (0.0%) | RR 0.00 (-0.04 to 0.04) | -- per 1.000 (from 0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | |

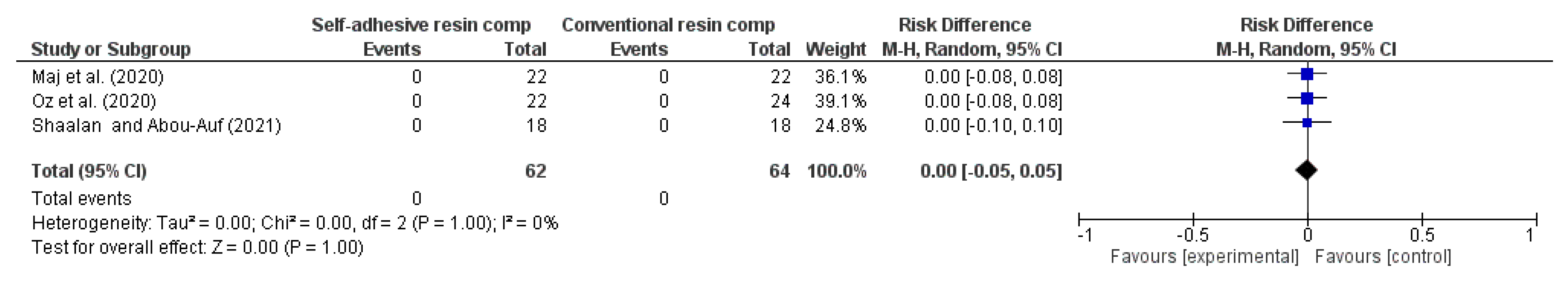

| Smoothness (follow-up: range 1 years to 2 years) | ||||||||||||

| 3 | RCT | NS | NS | NS | NS | VSAe | 0/62 (0.0%) | 0/63 (0.0%) | RR 0.00 (-0.05 to 0.05) | -- per 1.000 (from 0 fewer to 0 fewer) | ⨁⨁⨁⨁ High | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).