1. Introduction

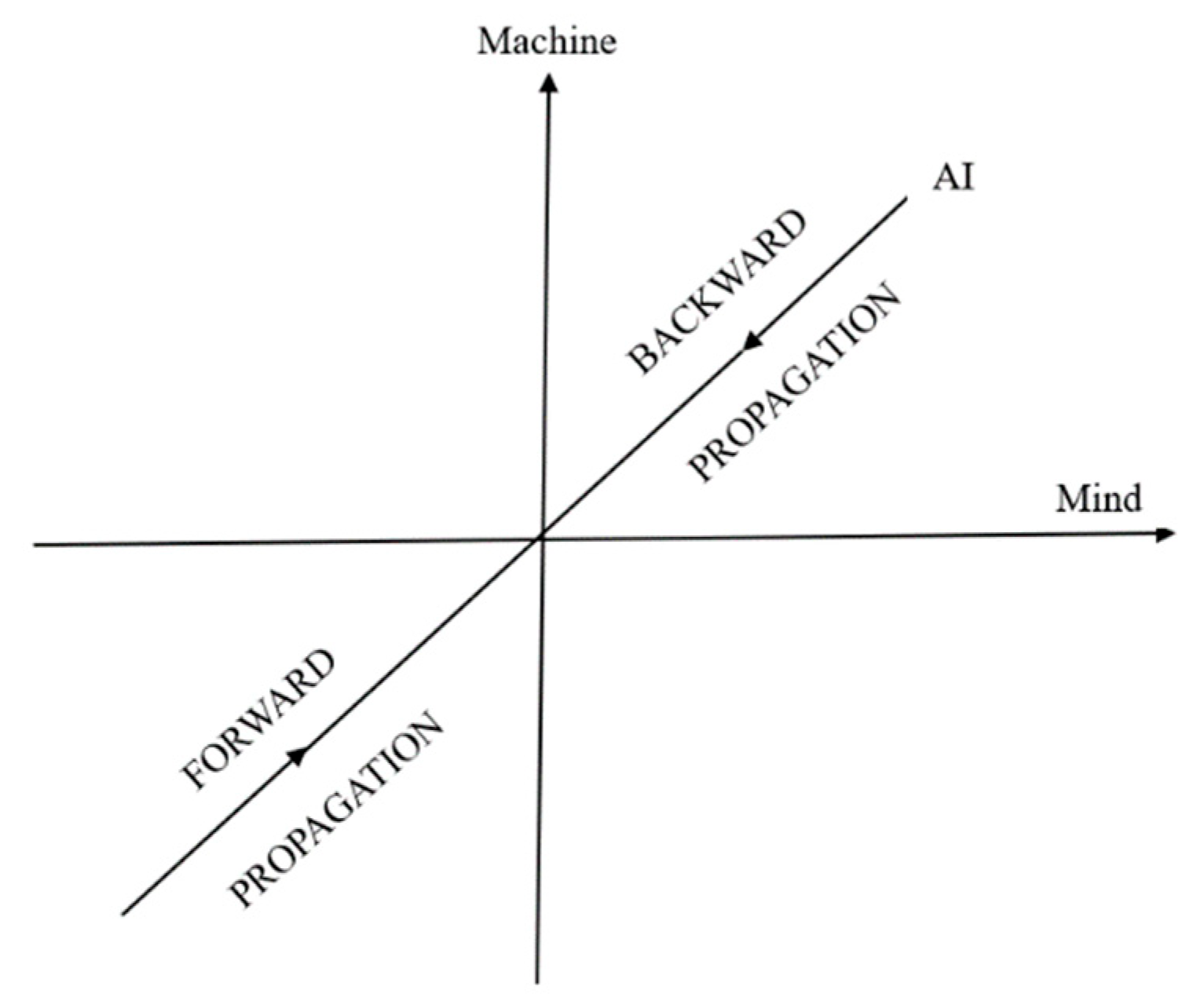

Perhaps you have heard the witticism: “What is mind? No matter. What is matter? Never mind.” In this paper, we refer matter to machine, i.e., the computer. Though of course open to debate, the general thrust of this quip seems to be that the mental is nonphysical (or at least not profitably studied as if it were physical) and that the study of the physical should be ignored by those studying the mind. Regardless of whether or not the aphorism was originally intended to convey this, there’s no denying that this dark interpretation is found congenial by many. Is there anything between mind and matter (machine)? This question refers to the Mind-Machine problem. To the question, the old answer is no; the new answer is yes, but why and how? This paper proposes a four-stage model in answering this question. We assume our working hypothesis as follows:

The Mind-Machine Hypothesis: Mind and machine are two eigenstates of the AI-dynamics. All other AI states are superpositions of the two eigenstates. The AI-dynamics can be achieved in four stages, and each stage is modeled by a particular Riemann surface.

Figure 1 shows that the mind and the matter are treated as two orthogonal dimensions while artificial intelligence as a superposition of mind and matter (machine). In other words, consider an AI system. It has two eigenstates, one is the mental state and the other is the physical (machine) state, and all other artificial states are superpositions of two eigenstates.

This paper aims to further develop the idea above into a mathematical model. The modeling method is Riemann Surface Analysis. It first constructs a mend-matter Riemann surface. Second, we develop a two-state analysis with Wyle spinor. Third, we do a four-state analysis with Dirac spinor. All the Riemann surface analyses will follow Penrose (2004, Chapters 8, and 22, and 29). Thus, the references from Penrose (2004) are omitted from the contexts. To put it in a straightforward way: in this paper, the ideas are mine but all the descriptions about Riemann surface are from Penrose. Readers only need to check if my ideas match Penrose’s explanations.

In an interview with Guyon Espiner, Geoffrey Hinton claims, “There isn’t this magical barrier between machines and people, when we people have something very special machine could never have. There is nothing about us that a machine couldn’t duplicate.” Yang (2025) reframes Hinton’s statement as a hypothesis as follows.

Hinton Hypothesis: We assume as our working hypothesis that everything about human species could be duplicated by artificial intelligence (machine).

We now extend this hypothesis to an advanced version: Theories are viewed as information of mind or matter. We assume as our working hypothesis that all the theories in physics and social sciences could be duplicated by artificial intelligence.

2. Riemann Surface by Duplicating Mind on Machine

Let us first review Penrose’s explanations about Riemann surface, “The Idea of Riemann Surface. There is of understanding what is going on with this analytic continuation of the logarithm function – or of any other many-valued function’ – in terms of what are called Riemann surface. Riemann’s idea was to think of such a function as being defined on a domain which is not simply a subset of the complex plane, but as a many-sheeted region. In the case of log z, we can picture this as a kind of spiral ramp flattened down vertically to the complex plane. … There is no conflict between different values of the logarithm now, because its domains this more extended winding space – and example of a Riemann surface – a space subtly different from the complex plane itself. (p.135)

To my way of thinking, there was a brutal mutilation of a sublime mathematical structure. Riemann taught us we must think of things differently. Holomorphic functions rest uncomfortably with the now usual notion of a ‘function’, which maps from a fixed domain to a definite target space. As we have seen, with analytic continuation, a holomorphic function ‘has a mind of its own’ and decides itself what its domain should be, irrespective of the region of the complex plane which we ourselves may have initially allotted to it. While we may regard the function’s domain to be represented by the Riemann surface associated with the function, the domain is not given ahead of time; it is the explicit from the function itself that tells us which Riemann surface the domain actually is.” (p.136)

Assume that there are two information systems, one is of the mind and the other is of the machine. Denote the as the information system of mind (purely mental) and the information system of machine purely physical). Further, assume both and are functions of a complex field. A key concept used in this paper is the so-called Analytical Continuation, which allows us to convert and into a continuous function as a manifold. A well-known and successful example of applying this method is the formulation of the Riemann Hypothesis.

3. Stage 1: Shannon Information and Riemann Surface of Logarithms

By the Hinton Hypothesis and its extension stated in

Section 1, we assume that there is an AI system which can duplicate a scientific theory such as quantum electrodynamics (QED). Regardless of the issue of understanding, what the AI duplicates is much of the information from QED. Shannon defines the notion of information mathematically in terms of the logarithm of probability. Self-information is mathematically defined as follows:

We know that in LLMs, the transformer embeds the input knowledge into vectors with a probability distribution. Thus, we may obtain the corresponding self-information by the Shannon definition. In differential geometry, the logarithm is an example of a Riemann surface. Specifically, the logarithm is a periodic function and accordingly, its Riemann surface has multiple zero points. This characterization is particularly important in machine learning.

Analogical analysis is an essential method in advancing sciences, even more so for interdisciplinary studies and integration science. Not only is it important to new scientific discoveries, but it is also a cognitive routine for us to understand a structure embodied in different theories. This idea conforms to the structuralism of the Bourbaki school of mathematical thought. Suppose an AI-agent is trained to learn some particular structure, say, the gauge structure with U(1) symmetry. This structure can be learned from the context of QED, or from other contexts such as market dynamics (Yang, 2023, 2024) or reasoning dynamics (Yang, 2024). Training and learning processes of a structure from different contexts are not necessarily periodic. However, from cognitive perspectives, multiple trainings are obviously helpful to our understanding. Thus, mathematically, multiple zero points of the Riemann surface of the logarithmic function allow repeated learning over multiple trainings. In general, the stronger the training of an AI-agent, the better the cognitive attractor.

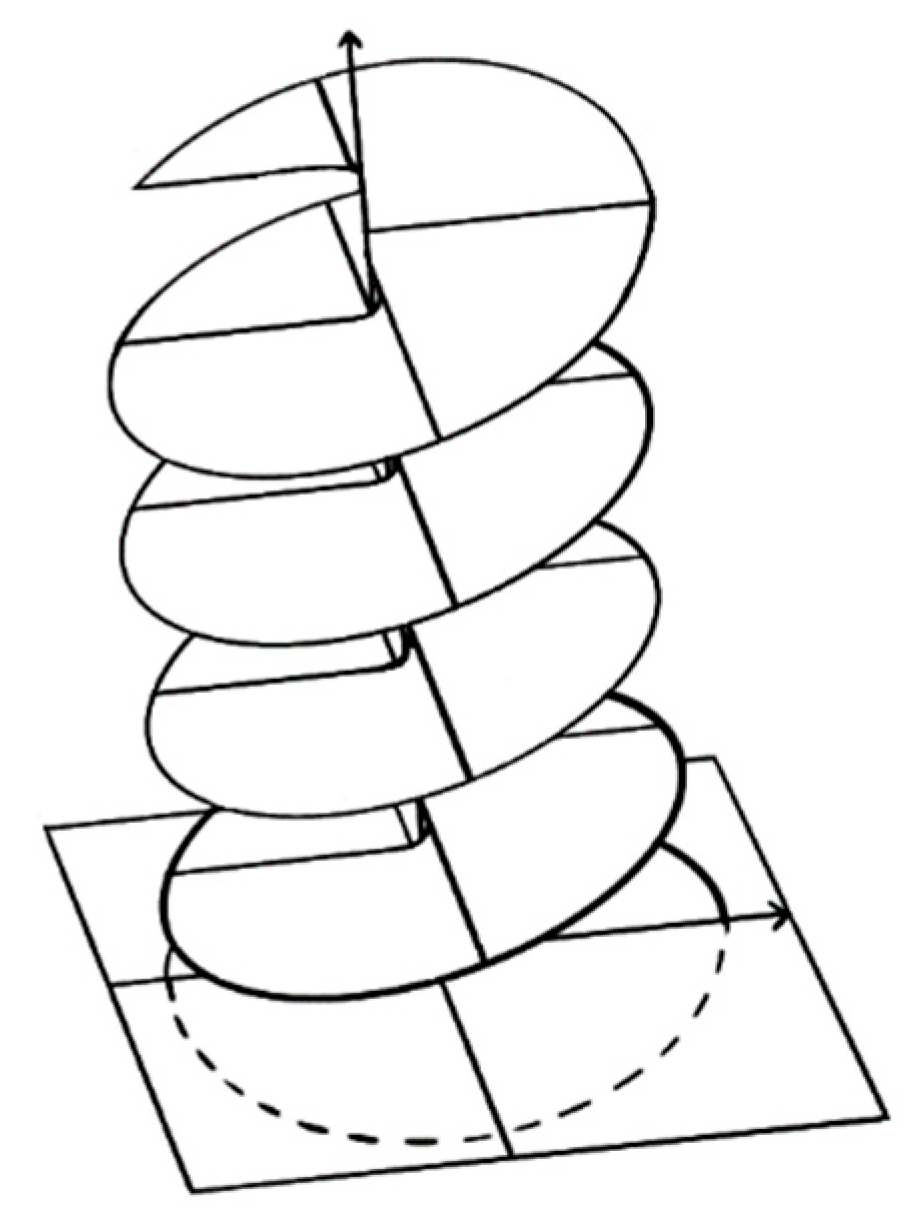

More interestingly, and ideally, assume that after repeated duplications of the same structure from multiple contexts, the AI-agent starts to understand the structure as Hinton predicts. If this happened, then the AI-agent could apply this structure to develop new contexts; i.e., to develop new theories. In this case, we may reasonably assume the learning processes are periodic with certain probabilities. As such, the information duplications form a perfect logarithmic function. Logarithmic function is a many-valued function, whose analytic continuation is a special Riemann surface. To explain, let us quote from Penrose (2004, §8.1):

“

There is a way to understand what is going on with this analytic continuation of the logarithm function – or of any other ‘many-valued function’ – in terms of what is called Riemann surface. Riemann’s idea was to think of such functions as being defined on a domain which is not simply a subset of the complex plane, but as a many-sheeted region. In the case of log , we can picture this as a kind of spiral ramp flattened down vertically to the complex plane. I have tried to indicate this in Fig. 8.1 (see

Figure 2 below).

The logarithm is single-valued on this winding many-sheeted version of the complex plane because each time we go around the origin, and has to be added to the logarithm, we find ourselves on another sheet of the domain. There is no conflict between the different values of the logarithm now, because its domain is this more extended winding space – an example of a Riemann surface – a space subtly different from the complex plane itself.”

4. Stage 2: Complex Mapping and Möbius Transformation

Human mind has created many beautiful scientific theories and hypotheses. For example, the following is the well-known Schrödinger equation in quantum mechanics:

This is a complex differential equation in which the imaginative i indicates that this equation is formulated on the complex field denoted as . Suppose an AI-agent is capable of duplicating this equation with its context of quantum mechanics into the machine: it would first assume that ‘another complex plane’ has been duplicated into the machine; denote this duplicated complex plane as Such a duplication function is called complex mapping. This is obviously a conformal mapping. Note that in LLM, all the verbal components of knowledge are first embedded into vectors, which can be represented as complex numbers (when it is 2-dimensional).

We define the transformation from complex plane

to

as a holomorphic function

:

; so that we have

, which satisfies

. The general transformation is as below:

where

, so that the numerator is not a fixed multiple of the denominator. This is called a

bilinear or

Möbius transformation, which is one of the simplest complex mapping.

Note that the point removed from the -plane is that value which would give ‘’; correspondingly, the point removed from the w-plane is that value ( which would be achieved by ‘’. In fact, the whole transformation would make more global sense if we were to incorporate a quantity ‘’ into both the domain and target. This is one way of thinking about simplest (compact) Riemann surface of all: the Riemann sphere.

Also note that

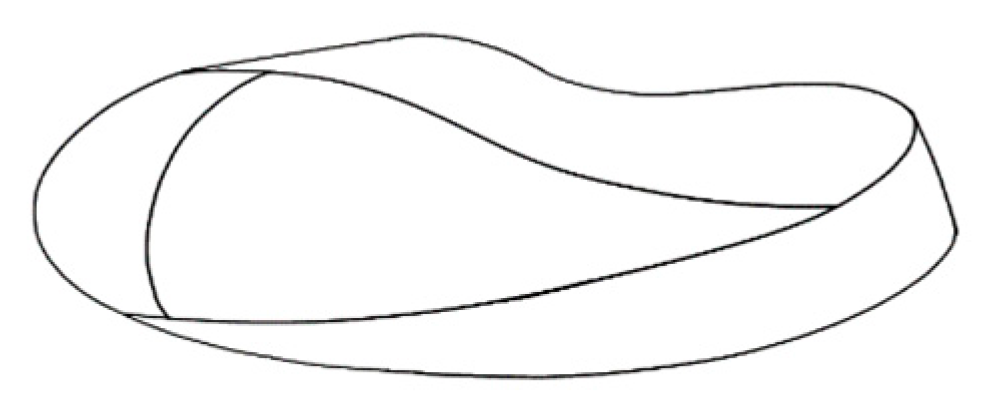

Möbius transformation above has nothing to do with the well-known

Möbius strip. Below we show the picture of

Möbius strip (see

Figure 3 below) only because it is a special kind of Riemann surface.

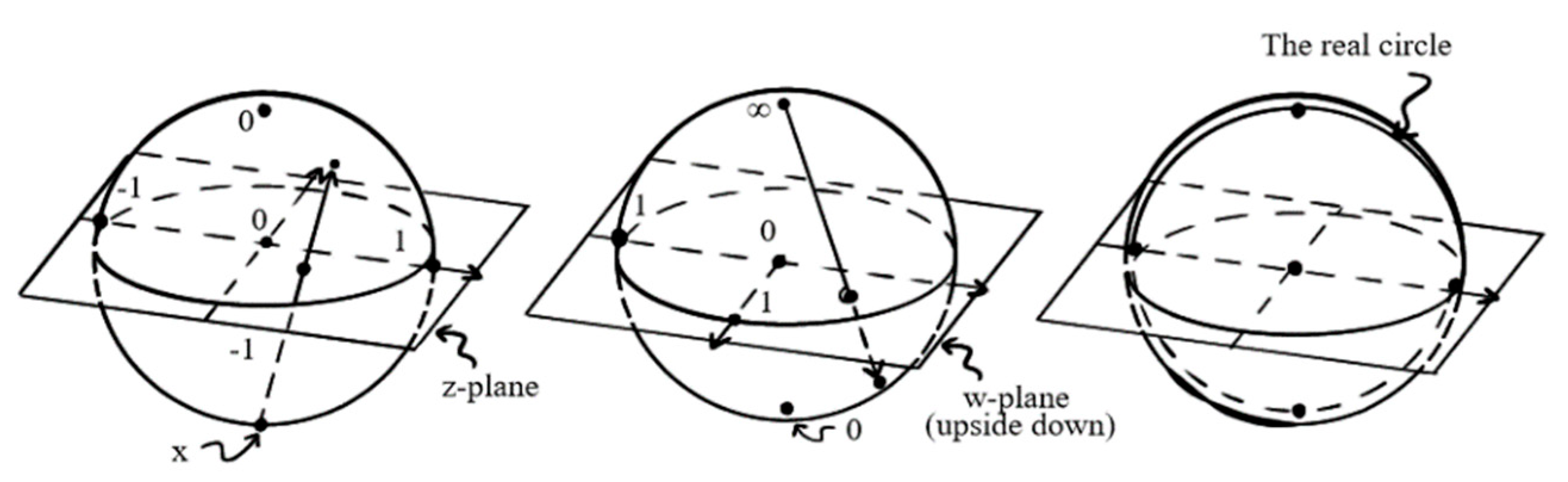

5. Stage 3: Merge Mind and Machine into Riemann Sphere

Now we assume that a theory as a piece of mind has been duplicated on machine as part of artificial intelligence based on the complex

-plane and the

w-plane respectively. The next step is to merge the complex planes into the so-called Riemann sphere. We regard the sphere is constructed from two ‘coordinate patches’: One of which is the

-plane and the other the

-plane. All but put two points of the sphere are assigned both a

-coordinate and a

-coordinate (related by the Möbius transformation above). But one point has only

-coordinate (where

w would be ’infinity’),and another has only

w-coordinate (where

z would be ’infinity’). We use

,

or both in order to define the needed conformal structure and, where we use both, we get the same conformal structure using either, because the relation between the two coordinates is holomorphic. In fact, for this, we do not need such a complicated transformation between

and

as the general Möbiu

s transformation. It suffices to consider the particularly simple Möbius transformation given by

where

and

, would each give

in the opposite patch. All this defines the Riemann sphere in a rather abstract way. See Penrose (2004, §8.3, pp.142-143) for further explanation.

One could not help himself to make a comment: Riemann Sphere provides a beautiful picture for a path toward the unified account of mind and machine.

Figure 4.

Riemann sphere from two complex planes.

Figure 4.

Riemann sphere from two complex planes.

6. Stage 4: Riemann Sphere of Two-State Systems Toward AI-Dynamics

The Riemann sphere above is called the conformal sphere, which puts mind and machine in one system through artificial intelligence. In this section, we introduce another kind of Riemann sphere with more structures, which is called the metric sphere. This new Riemann sphere is a two-state system that makes the AI-agent a dynamic system.

Consider an AI agent, like an electron, which has an internal space. The AI-agent possesses an intrinsic property called spin which is the momentum of its internal rotation. The AI-spin has two basic eigenstates: one is purely mental and the other is purely machinery, denoted as

(called spin-up) and

respectively. We assume the two eigenstates are orthogonal, and their linear superpositions are denoted by

. It can be defined as follows,

where

and

are not just complex numbers but are amplitudes with certain Born probabilities. This is the reason why the corresponding Riemann sphere is a metric sphere that will be introduced shortly. The AI-agent has a spin of 1/2, which is similar to an electron or quark. Each state has a complex phase. The difference between two state-phases yields new a phase (by linear superposition) called the dynamic or relative phase. Here, the set of all dynamic phases satisfy mathematical U(1) symmetry. For more detailed discussions, please see Penrose (2004, §22.9).

The above AI-system of the two-state (mind vs machine) can be projected to the Riemann sphere of two-states. For the Riemann sphere with a two-state system, the key concept is the notion of

antipodal points, which is part of the sphere’s structure. We use the north pole to represent the spin state

. In the two-state AI system, the north pole represents the mind and the south pole represents the machine, see

Figure 5 below.

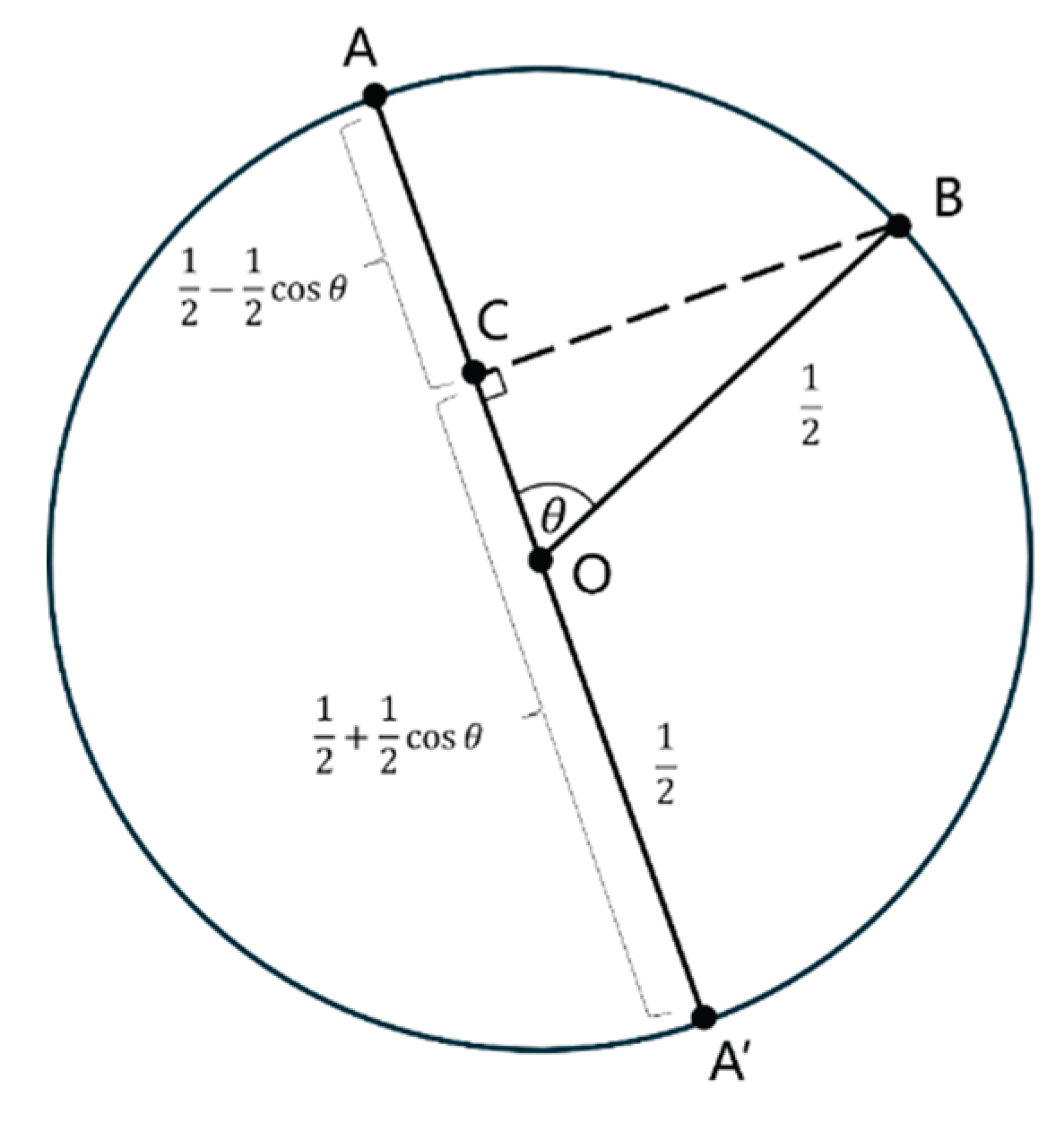

Suppose that the initial state of a two-state system is represented by the point B on the Riemann sphere and we wish to perform a Yes/No measurement corresponding to some other point on the sphere, where YES would find the state at A, and No would find it at the point , antipodal to A. If we take the sphere to have radius 1/2, and projecting B orthogonally to C on the axis , we find that the probability of YES is the length , which is and the probability of NO is the length CA, which is assuming that the angle is between OB and CA with the sphere’s centre being O.

Not that the ‘Riemann sphere’ used here has more structure than that of conformal sphere and celestial sphere in that now the notion of ‘antipodal point’ is part of the sphere’s structure (in order that we can tell which states are ‘orthogonal’ in the Hilbert-space sense. The sphere is now a ‘metric sphere’ rather than a ‘conformal sphere’, so that its symmetries are given by rotations in the ordinary sense, and we lose the conformal motions that were exhibited in aberration effects on the celestial sphere.

7. Concluding Remarks

Remark 1. The repeated advancements of artificial intelligence provide a new angle for us to reengage the old mind-machine problem. This paper claims the artificial intelligence has two eigenstates: mind and machine. The other AI states are supposition of the two eigenstates.

Remark 2. This paper formulates a four-stage model toward AI-dynamics; each stage is characterized by a different Riemann surface or sphere.

Remark 3. The further topics along this line is about high spin of the AI system. It involves mathematical models such as the Ising model, Majorana picture, and Penrose Twistor.

Remark 4. In LLMs, currently the relative angle between two token-vectors are treated as scaling angle distance. Another possible approach is to treat relative phases as dynamic phases. This is the way that leads to the gauge-field-theoretic modeling.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks my students at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute who did proofreading of the present paper. Particularly, I want to thank Aliya Yang, Laura Phan, and Xin Fu for their help in preparing figures used in this paper.

References

- Penrose, R. (2004). The Road to Reality: A complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Alfred, A. Knopf, New York.

- Yang, Y. (2024). Principles of Market Dynamics: Economic Dynamics and Standard Model (II). Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. (2024). Principles of Reasoning Dynamics. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).