1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) emerge as the primary cause of mortality worldwide. In 2019, they were responsible for almost 17.9 million deaths, which equates to 32% of all deaths globally [

1]. Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a chronic condition that reduces blood flow to the heart muscle, causing morbidity and mortality worldwide. In 2016, over half a million people in the European Union lost their lives to coronary diseases. Those over 65, were mostly affected. Death rates from these heart conditions have decreased in recent years. However, men seem to be more vulnerable to CAD than women [

2]. Coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG) is a standard treatment alternative for CAD since 1960 [

3]. In Greece, 473.2 CABG procedures per million population were performed in 2022, which is among the highest rates in Europe [

4]. In the United States of America (USA), almost 40,000 such surgeries are being performed a year [

5]. Surgical site infections (SSIs) are estimated to take place in around 8.6% of patients undergoing CABG in the UK [

6].

A plethora of risk factors may affect the development of SSIs that occur in patients after CABG. SSIs are one of the most significant complications in surgical patients and are associated with many adverse outcomes. Monitoring SSIs is considered a promising strategy for reducing infection rates and serves as a valuable tool for evaluating the impact of various infection prevention interventions [

7,

8]. SSIs are highly associated with increased mortality rates, length of stay, readmission, and healthcare costs. The healthcare costs, due to SSIs in the USA, can reach up to US

$900 million a year [

9,

10]. SSIs, which develop following CABG surgery, can involve only the superficial layers of the incision or extend deeper into the tissues [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. The epitome of SSIs after CABG are considered to be sternal wound infections (SWIs) and especially deep sternal wound infections (DSWIs). DSWI is a rare but serious postoperative complication, linked to higher short-term and long-term mortality rates [

18]. It is common, during CABG, the saphenous vein to be harvested from the lower limb in order to be used as a graft. Complications in wound healing at the saphenous vein harvest site are much more common, with SSI rates reported between 2% and 20% [

19,

20,

21]. Leg wound infections at donor sites are responsible for over 70% of severe infection cases following cardiac surgery [

22]. An important proportion of SSIs are diagnosed only after hospital discharge. That way, the actual burden of infection may be underestimated, especially in studies that focus exclusively on data that are collected only when patients are still in the hospital [

23].

Many studies have looked into the risk factors linked to SSIs after CABG, paying special attention to DSWIs, which tend to be more serious and carry higher risks for patients. One of the risk factors that often show up when it comes to DSWI after CABG is diabetes mellitus, particularly in patients requiring insulin or with poor glycaemic control. Obesity (especially when BMI exceeds 30) also stands out as a major factor. Age and female sex have been linked to increased vulnerability, as well as COPD and chronic kidney disease. Furthermore, the use of bilateral internal mammary arteries, extended surgical duration, and perioperative blood transfusions are all associated with increased DSWI risk. A hospital stay longer than 24 hours before surgery, along with postoperative complications such as prolonged mechanical ventilation and the need for sternal re-exploration, have all been independently linked to DSWIs [

24,

25,

26,

27].

The risk factors for SSIs in general (sternotomy or at the leg incision site used for graft harvesting), following CABG, include clinical and surgical characteristics. Obesity, defined as a body mass index over 30, stands out as a key factor that increases SSIs after CABG. Diabetes, especially when it’s poorly controlled or requires insulin, also significantly raises the chances of developing SSIs. Age and gender play a role, too, with older patients and women being more susceptible. Reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (below 45%), peripheral vascular disease, prolonged surgery time (particularly surgeries that tend to last over five hours), as well as the need for re-exploration or multiple blood transfusions, also affect the SSI rates. Extended preoperative hospital stays, undergoing emergency surgery, and poor glycemic control (such as an HbA1c level above 7.5%) can also increase the likelihood of developing an infection [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

The present study aimed to investigate the incidence of infections in patients at intermediate to high risk undergoing CABG and to identify the factors contributing to their development. While previous studies have reported on the field of SSIs among CABG patients, this study attempted to provide updated data on the infection incidence, highlighting risk factors that should be taken into account when healthcare administrators and clinicians design targeted preventive interventions with a particular focus on patients at intermediate and high risk for developing postoperative SSIs.

2. Materials and Methods

This study followed a prospective observational design. The dependent variable was the incidence of SSIs. SSIs include infections that may occur at the sternotomy site or the leg incision site after CABG. So, SSIs may present as SSWI, DSWI, and saphenous vein harvest site infections. Independent variables included patient sociodemographic characteristics (age, biological sex, marital status, level of education), comorbidities (diabetes, obesity), lifestyle factors (smoking status), as well as clinical and operative parameters, including hospital length of stay and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF).

The study was conducted in the cardiothoracic surgery department and intensive care unit of a large tertiary general hospital in the Attica region of Greece. Eligibility for study participation was determined based on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. To be eligible, participants had to be 18 years of age or older, scheduled to undergo CABG via median sternotomy, to able to read and write in Greek and to be classified as intermediate or high risk, based Brompton Harefield Infection Score (BHIS), a stratification tool for predicting risk of surgical site infection after coronary artery bypass grafting [

33]. Additionally, written informed consent was required. Exclusion criteria included recent substance or alcohol abuse, as well as active infection within two weeks before surgery. Patients with a preoperative hospital stay longer than two days, those undergoing combined surgical procedures involving the aorta or heart valves, or those scheduled for emergency or urgent CABG were also excluded. Further exclusion criteria involved re-sternotomy for bleeding control or cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and incomplete sternal closure at the time of ICU admission.

Based on the above criteria, a convenience sampling method was used to recruit participants who underwent isolated CABG between April 2024 and January 2025, resulting in a final sample of 51 patients. Forty patients were excluded: 5 declined participation, 10 failed to complete their follow-up checks as planned, 2 died, and 23 were classified as low risk for SSI.

Patients scheduled to undergo CABG who met the inclusion criteria were approached. Demographic and medical data were collected from each patient's medical records (both paper and electronic) and via clinical assessment. Patients arrived at least 24 hours before the scheduled surgery. A demographic data form was completed, and written informed consent for participation in the study was obtained. Risk stratification for the development of SSIs after CABG was performed for each patient using the Brompton Harefield Infection Score (BHIS) [

33]. This tool helps predict the risk of SSIs after CABG. Developed in the UK in 2015 by Raja et al., it analyzed 41 variables and identified five key risk factors: diabetes or HbA1c >7.5%, BMI over 35, female gender, urgent surgery, and LVEF below 45%. Points are assigned as follows: 1 point for diabetes or 3 points for HbA1c >7.5%; 2 points for BMI >35; 2 points for female gender; 2 points for urgent surgery; and 1 point for LVEF <45%. Scores are added to classify patients into low (0–1), intermediate (2–3), or high risk (≥4) for developing an SSI after CABG [

33]. Permission to use the scoring system was obtained from its original developers. Stratification was conducted preoperatively, on the day before surgery. Based on the preoperative risk assessment, patients that identified as intermediate or high risk for developing SSIs were included in the study sample.

The presence of an SSI was assessed daily, clinically, and by using the ASEPSIS scoring method [

34,

35] on each surgical wound that was carried by the patient. ASEPSIS is a tool used to assess surgical wound infections, developed in England in 1986 by Wilson et al. [

34]. It evaluates wounds based on symptoms such as serous discharge, redness, pus, and wound breakdown after cardiac surgery. Additional points are assigned for factors including antibiotic treatment, pus drainage, surgical cleaning under anesthesia, bacterial isolation, and hospital stays longer than 14 days. The highest weekly score determines the infection severity: 0–10 indicates satisfactory healing, 11–20 disturbed healing, 21–30 mild infection, 31–40 moderate infection, and over 40 severe infection. Use of ASEPSIS was authorized by its creators and the team who translated and validated it for the Greek population [

34,

35]. The assessment was conducted by the research team. A formal evaluation of patients' wounds, using the ASEPSIS tool, was also performed at the time of discharge. A close follow-up for possible SSI development was conducted on postoperative day 14, which is in accordance with the scheduled suture removal. On postoperative day 30, patients returned to the hospital for wound reassessment. For the first three months, follow-up evaluations were conducted at hospital facilities every 15 days, and subsequently monthly for an additional three months, during which the ASEPSIS tool was consistently used. All patients were informed that they could contact their physician or the research investigator at any time if they experienced symptoms of an SSI (such as redness, drainage, etc.), whether they were in or out of the hospital. Each patient was monitored for an SSI for 6 months after CABG.

The study protocol was approved by the hospital's Ethics Committee (approval number: 513/29.11.2023) and the Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 7414/10.01.2024). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion. The study was conducted under the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. All personal information is kept confidential, and participants have the right to withdraw from the study at any time without penalty.

The statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables were shown as counts (percentages). To examine the relationship between a continuous and a dichotomous variable, the Spearman correlation coefficient (ρ) was used. The phi coefficient (φ) was applied to assess the association between two dichotomous variables. For all tests, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The study sample consisted of 51 patients, 39 men (76.5%) and 12 women (23.5%), with a mean age of 67.2 ± 8 years. Forty-six (90.2%) patients were married or cohabiting. Twenty-five (49%) had primary education, 24 (47.1%) had secondary education, and the remaining 2 (3.9%) had tertiary education. Eighteen (35.3%) were obese, 36 (70.6%) had diabetes, and 29 (56.9%) were smokers. Seven (13.7%) had an ejection fraction less than or equal to 45%. The mean length of hospital stay was 6 ± 1.1 days.

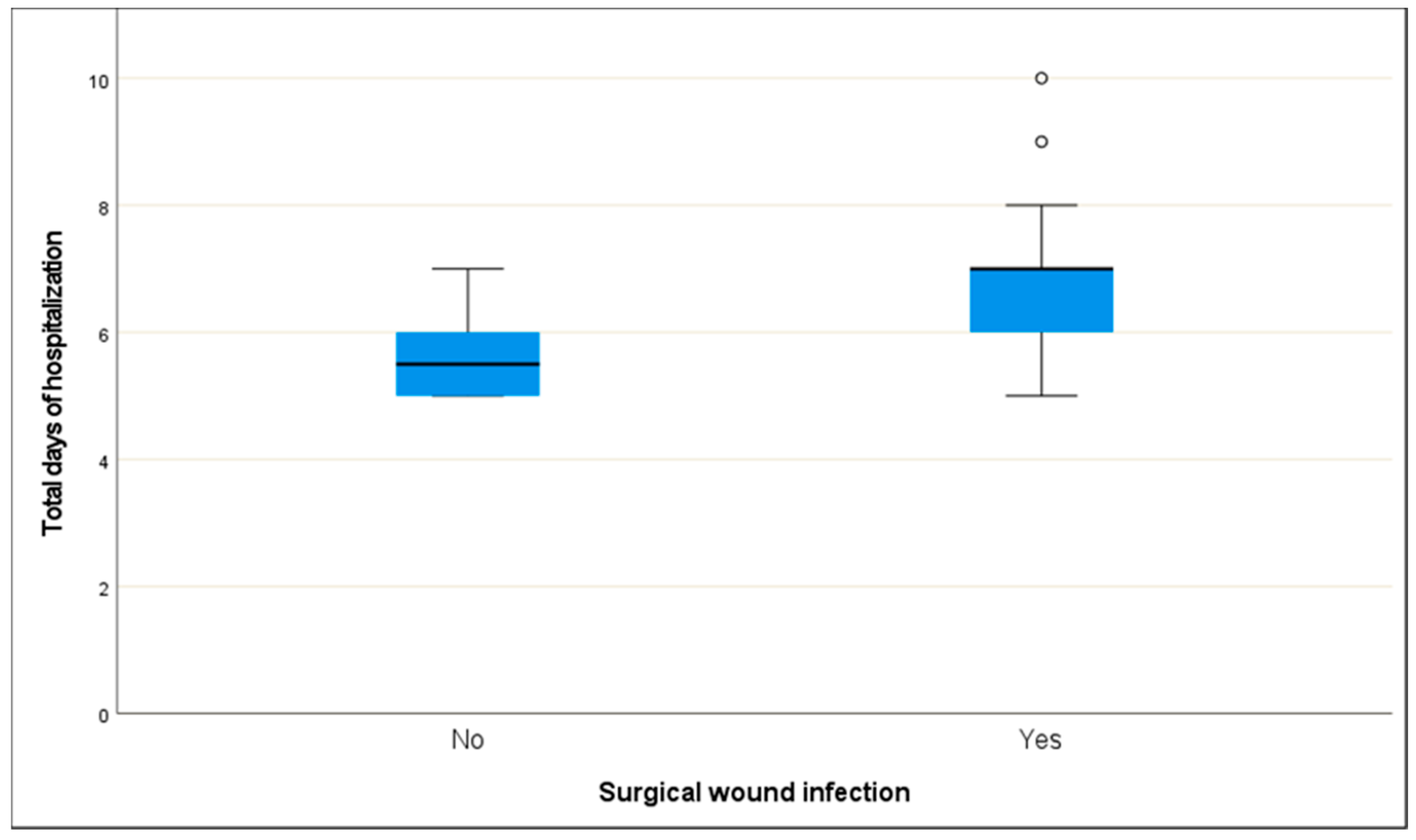

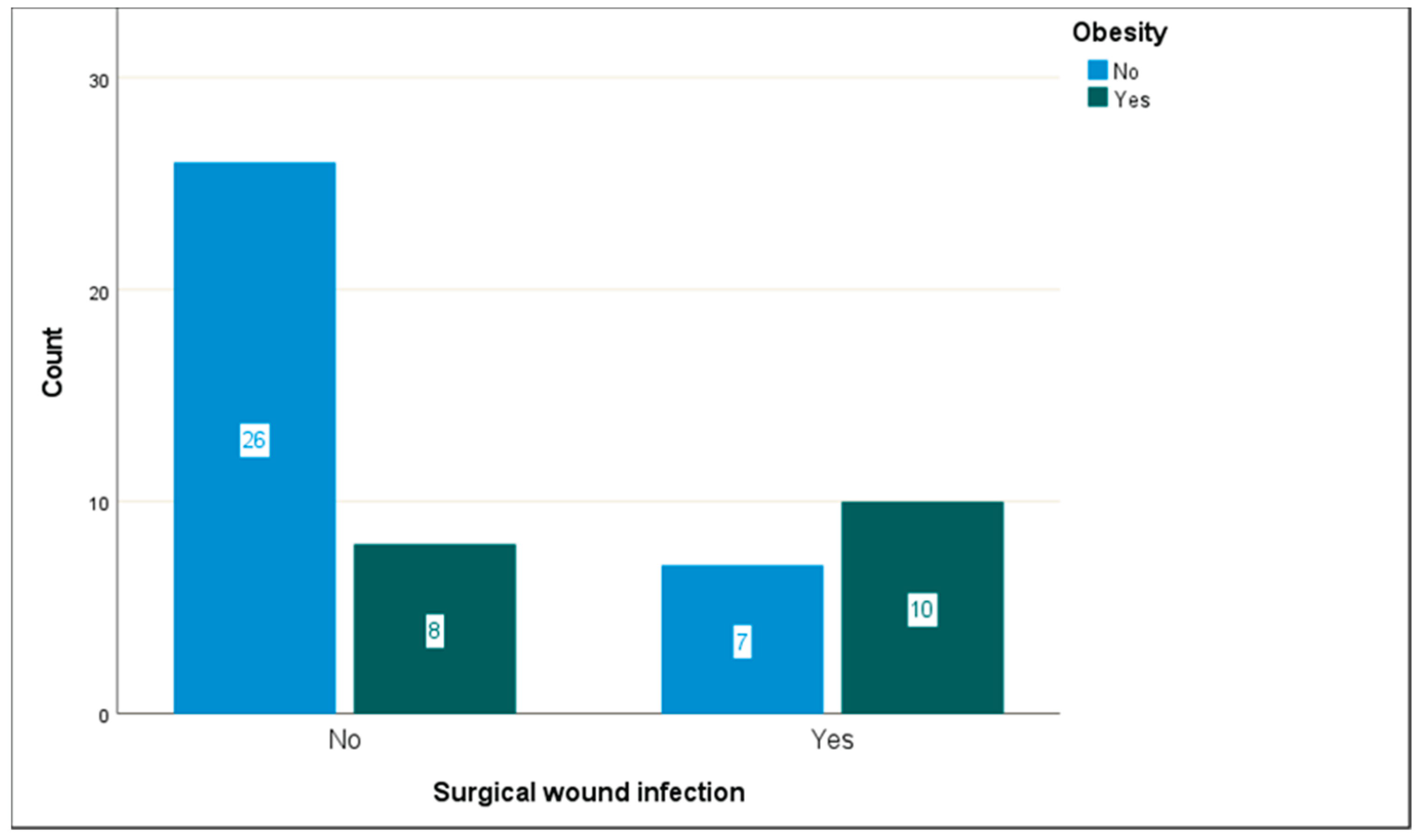

SSIs occurred in 17 of the 51 patients (33.3%). The presence of infection was found to be statistically significantly related to days of hospitalization (ρ = 0.512, p < 0.001) and obesity (f = 0.348, p = 0.013). Specifically, more days of hospitalization and obesity correspond to higher rates of SSIs. Age (ρ = 0.014, p = 0.922), biological sex (f = 0.196, p = 0.161), smoking (f = 0.140, 0.318), diabetes mellitus (f < 0.001, p = 0.999), and ejection fraction (f = 0.040, 0.774) are not associated with the occurrence of SSI.

Table 1.

Socio-demographics and clinical characteristics of the study’s sample.

Table 1.

Socio-demographics and clinical characteristics of the study’s sample.

| |

N = 51 |

N % |

| Surgical wound infection |

No |

34 |

66.7% |

| Yes |

17 |

33.3% |

| Biological sex |

Female |

12 |

23.5% |

| Male |

39 |

76.5% |

| Marital status |

Single/ Divorced/ Widowed |

5 |

9.8% |

| Married/ Ιn a civil partnership |

46 |

90.2% |

| Higher level of education |

Up to primary education |

25 |

49.0% |

| Secondary education |

24 |

47.1% |

| Higher education |

2 |

3.9% |

| Obesity |

No |

33 |

64.7% |

| Yes |

18 |

35.3% |

| Diabetes |

No |

15 |

29.4% |

| Yes |

36 |

70.6% |

| Smoking |

No |

22 |

43.1% |

| Yes |

29 |

56.9% |

| LVEF <45% |

No |

44 |

86.3% |

| Yes |

7 |

13.7% |

| LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction |

Table 2.

Age and days of hospitalization concerning the occurrence of SSIs.

Table 2.

Age and days of hospitalization concerning the occurrence of SSIs.

| |

Surgical wound infection |

Test, p-value |

| No |

Yes |

| Mean |

Standard Deviation |

Mean |

Standard Deviation |

| Age |

66.9 |

7.5 |

67.7 |

9.3 |

ρ(51) = 0.014, p = 0.922 |

| Total days of hospitalization |

5.6 |

0.7 |

6.8 |

1.3 |

Ρ(51) = 0.512, p < 0.001 |

Table 3.

Biological sex, obesity, diabetes, and smoking concerning the occurrence of SSIs.

Table 3.

Biological sex, obesity, diabetes, and smoking concerning the occurrence of SSIs.

| |

Surgical wound infection |

Test, p-value |

| No |

Yes |

| Biological sex |

Female |

6 |

6 |

f = 0.196, p = 0.161 |

| Male |

28 |

11 |

| Obesity |

No |

26 |

7 |

f = 0.348, p = 0.013 |

| Yes |

8 |

10 |

| Diabetes |

No |

10 |

5 |

f < 0.001, p = 0.999 |

| Yes |

24 |

12 |

| Smoking |

No |

13 |

9 |

f = 0.140, 0.318 |

| Yes |

21 |

8 |

| LVEF <45% |

No |

29 |

15 |

f = 0.040, 0.774 |

| Yes |

5 |

2 |

| LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction |

Figure 1.

Days of hospitalization concerning the occurrence of SSIs.

Figure 1.

Days of hospitalization concerning the occurrence of SSIs.

Figure 2.

Obesity concerning the occurrence of SSIs.

Figure 2.

Obesity concerning the occurrence of SSIs.

4. Discussion

In our study, we found that approximately one in three patients developed an SSI following CABG. Among the various parameters examined, obesity and prolonged hospital stay stood out as the main factors associated with the occurrence of SSIs. On the other hand, no clear associations were observed between SSIs and other factors, including diabetes, patient age, smoking status, or left ventricular ejection fraction.

As aforementioned, an SSI incidence of 33.3% in CABG patients, in our study, is being presented. This seems to be higher than what has been reported in the existing literature, where SSI incidence typically ranges between 2% and 10% [

36,

37]. SSIs at the saphenous vein harvesting location are a frequent complication, with incidence rates ranging from 2% to 20% [

19,

20,

38]. It is important to note, however, that our study population consisted solely of patients at intermediate or high risk for developing an SSI. Therefore, a higher incidence rate is not unexpected when compared to studies that include lower-risk patient groups. Apart from the higher-risk profile of our patients, there are a couple of other factors that may help explain this difference in incidence. Firstly, the variation in research methods across different studies is of primary importance. For example, some studies use active post-discharge surveillance to identify infections, whereas others rely exclusively on clinician documentation. Some studies do not include structured follow-up after hospital discharge, which likely leads to underestimation of SSI incidence. All the previous can result in underreporting of SSIs. Reported rates may differ depending on how long patients are monitored, what counts as an SSI, and the specific diagnostic criteria used. In the study [

23], one significant finding was that in patients who underwent CABG, most SSIs were diagnosed after the patient was discharged from the hospital, suggesting that it is possible an SSI to be missed. Hospital protocols, antibiotic use, surgical methods, and wound care practices are major factors that can explain why the SSI rates vary among studies.

A lot of research has looked into what might increase the chances of SSI. The most commonly identified risk factors include obesity and diabetes mellitus, as well as perioperative and postoperative complications [

36,

39,

40,

41,

42]. The influence of patients' relative body weight on both early and long-term outcomes following cardiac surgery has been a topic of ongoing debate. Obesity comes up as an important factor that can increase the chance of infections after CABG. Adipose tissue produces some cytokines that have effects on immune cells. That way, the body’s ability to fight infections can be impaired. A general trend of increasing risk of SSIs has been observed as BMI increased from normal levels to morbid obesity across nearly all types of surgeries [

43]. In terms of CABG, morbidly obese patients are generally at a higher risk for SSIs, with obesity being an undeniably major risk factor in the development of SSIs [

44].

Also, as stated earlier, it is well-known that people with diabetes tend to develop infections after surgery [

45]. Diabetics are more likely to get SWIs after CABG compared to non-diabetic patients [

46]. While diabetes is often deemed a major factor on its own for SSIs [

45], we didn’t find a significant association in this particular group of patients. This result was somewhat unexpected, considering what has been found by other researchers. Possible explanations include the relatively small sample size, the single-centre design of our study, and the high proportion of diabetics within our cohort, reducing the variability needed to unveil differences. We also didn’t observe a clear association between other factors like age, smoking, or ejection fraction and SSIs. A possible explanation is the relatively limited sample size in our study, which may have made it harder to discover smaller differences. It might also be that our patient group was relatively homogenous in certain characteristics (for example, age), limiting the ability of these factors to emerge as significant.

Another important finding of our study was the strong association between the incidence of SSIs and the length of patient hospitalization, which is likely bidirectional. Staying in the hospital longer, on its own, can increase a patient's exposure to hospital-acquired germs, which raises the chance of developing an infection. The longer someone stays, the more likely it is that bacteria will settle on their body, making post-surgical infections more likely. Prolonged pre-operative hospitalization has been recognized as a significant risk factor for healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). In the study [

47], extended pre-operative stays were associated with increased incidence of SSIs among cardiac surgery patients. Even so, there's not a lot of research that focuses specifically on how longer hospital stays affect SSI rates in CABG patients. This particular aspect needs to be looked at more closely. Understanding this link better could help us find ways to lower the risk of SSIs.

Despite the new data provided to the current body of literature, which could be utilized for the early identification of high-risk patients and the planning of preventive strategies in the field of SSIs in the CABG setting, our study has several limitations. One clear limitation of our study is the small sample size, which makes it harder to apply these findings to larger or more diverse groups of patients. Also, since all the data came from just one hospital, the results might not reflect what happens in other settings, where treatment protocols and patient profiles can differ. We also examined only a limited number of risk factors, due to our small sample size, which means we might have missed other important contributors. Finally, without a multivariate analysis, we couldn’t fully explore which factors were truly driving to SSIs, since we weren’t able to adjust for potential cofounders

5. Conclusions

Our study highlights that prolonged hospital stay and obesity are significant factors associated with an increased risk of SSIs in patients undergoing CABG. These findings underscore the importance of early risk stratification, close postoperative monitoring, and the implementation of targeted preventive strategies, especially for intermediate to high-risk patient groups. Nurse-led interventions, strict wound care protocols, and enhanced surveillance may help reduce infection rates and improve patient outcomes. Despite the valuable insights provided, the results should be interpreted with caution due to the study’s limitations, including the small sample size, single-center design, and lack of multivariate analysis. Future multicenter studies with larger sample sizes, a broader range of studied variables, and the use of multivariate analysis are needed to validate these findings and to support the development of evidence-based infection prevention protocols for this patient population.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used: Conceptualization, P.K., A.E.P., T.K., E.P., L.A.P., J.K., I.S., and K.G.; Data curation, P.K., T.K., and K.G.; Formal analysis, P.K., A.E.P., T.K., I.S., and K.G.; Investigation, P.K., A.E.P., T.K., I.S., and K.G.; Methodology, P.K., A.E.P., T.K., E.P., and K.G.; Resources, P.K., E.P., and K.G.; Software, P.K., A.E.P., and K.G.; Supervision, K.G.; Validation, P.K., A.E.P., T.K., L.A.P., J.K., and K.G.; Visualization, P.K. and T.K.; Writing – original draft, P.K., A.E.P., T.K., L.A.P., and K.G.; Writing – review & editing, P.K., A.E.P., T.K., E.P., L.A.P., J.K., I.S., and K.G.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the research ethics committees of both the Hellenic Mediterranean University (7414/ 10 January 2024) and Evangelismos General Hospital of Athens (513/29 November 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Precautions were taken to protect participants’ privacy and anonymity, as well as the confidentiality of their data. Furthermore, participants were provided with and signed a relevant informed consent form.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their voluntary participation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

-

World Health Organization. (2024). Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). WHO Fact Sheets. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

- Eurostat. (2020, September 28). Deaths due to coronary heart diseases in the EU. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/edn-20200928-1.

-

Palmerini, T., Serruys, P., Kappetein, A. P., Genereux, P., Riva, D. D., Reggiani, L. B., Christiansen, E. H., Holm, N. R., Thuesen, L., Makikallio, T., Morice, M. C., Ahn, J. M., Park, S. J., Thiele, H., Boudriot, E., Sabatino, M., Romanello, M., Biondi-Zoccai, G., Cavalcante, R., Sabik, J. F., … Stone, G. W. Clinical outcomes with percutaneous coronary revascularization vs coronary artery bypass grafting surgery in patients with unprotected left main coronary artery disease: A meta-analysis of 6 randomized trials and 4,686 patients. Am. Heart J. 2017, 190, 54–63. [CrossRef]

-

European Society of Cardiology. Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery per million inhabitants. ESC Atlas of Cardiology n.d.. Available from: https://eatlas.escardio.org/Atlas/ESC-Atlas-of-Cardiology/Cardiovascular-healthcare-delivery/Cardiac-surgery/sipcp_cabg_1m_r-coronary-artery-bypass-graft-surgery-cabg-per-million-people (accessed on June 29, 2025).

-

Ghandakly, E. C.; Iacona, G. M.; Bakaeen, F. G. Coronary Artery Surgery: Past, Present, and Future. Rambam Maimonides Med. J. 2024, 15(1), e0001. [CrossRef]

- Cardiothoracic Interdisciplinary Research Network. (2020). National survey of variations in practice in the prevention of surgical site infections in adult cardiac surgery, United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland. Journal of Hospital Infection, 106, 812–819.

-

Gastmeier, P.; Sohr, D.; Just, H.M.; Nassauer, A.; Daschner, F.; Rüden, H. How to survey nosocomial infections. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2000, 21, 366–370.

-

Haley, R.W.; Culver, D.H.; White, J.W.; Morgan, W.M.; Emori, T.G.; Munn, V.P.; Hooton, T.M. The efficacy of infection surveillance and control programs in preventing nosocomial infections in US hospitals. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1985, 121, 182–205.

-

AlRiyami, F. M.; Al-Rawajfah, O. M.; Al Sabei, S.; Al Sabti, H. A. Incidence and risk factors of surgical site infections after coronary artery bypass grafting surgery in Oman. J. Infect. Prev. 2022, 23(6), 285–292. [CrossRef]

-

de Lissovoy, G.; Fraeman, K.; Hutchins, V.; et al. Surgical site infection: Incidence and impact on hospital utilization and treatment costs. Am. J. Infect. Control 2009, 37(5), 387–397. [CrossRef]

-

Priyadharshanan, M.; Loubani, M. Risk factors and mortality associated with deep sternal wound infections following coronary bypass surgery with or without concomitant procedures in a UK population: A basis for a new risk model? Interact. CardioVasc. Thorac. Surg. 2010, 11(5), 543–551. [CrossRef]

-

Balachandran, S.; Lee, A.; Denehy, L.; Lin, K.-Y.; Royse, A.; Royse, C.; El-Ansary, D. Risk factors for sternal complications after cardiac operations: A systematic review. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2016, 102(6), 2109–2117. [CrossRef]

-

Filsoufi, F.; Castillo, J. G.; Rahmanian, P. B.; Broumand, S. R.; George, S.; Carpentier, A.; Adams, D. H. Epidemiology of deep sternal wound infection in cardiac surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2009, 23(4), 488–494. [CrossRef]

-

Heilmann, C.; Stahl, R.; et al. Wound complications after median sternotomy: A single-centre study. Interact. CardioVasc. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 16(5), 643–650. [CrossRef]

-

Kubota, H.; Miyata, H.; Motomura, N.; et al. Deep sternal wound infection after cardiac surgery. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2013, 8, 132. [CrossRef]

-

Lola, I.; Levidiotou, S.; Petrou, A.; Arnaoutoglou, H.; Apostolakis, E.; Papadopoulos, G. S. Are there independent predisposing factors for postoperative infections following open heart surgery? J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2011, 6, 151. [CrossRef]

-

Siddiqi, M. S. Saphenous vein harvest wound complications: Risk factors, identification. Chronic Wound Care Manag. Res. 2016, 3, 53–62. [CrossRef]

-

Ruka, E.; Dagenais, F.; Mohammadi, S.; Chauvette, V.; Poirier, P.; Voisine, P. Bilateral mammary artery grafting increases postoperative mediastinitis without survival benefit in obese patients. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2016, 50(6), 1188–1195. [CrossRef]

-

Hassoun-Kheir, N.; Hasid, I.; Bozhko, M.; et al. Risk factors for limb surgical site infection following coronary artery bypass graft using open great saphenous vein harvesting: A retrospective cohort study. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2018, 27(4), 530–535. [CrossRef]

-

Swenne, C.L.; Lindholm, C.; Borowiec, J.; Carlsson, M. Surgical-site infections within 60 days of coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J. Hosp. Infect. 2004, 57(1), 14–24. [CrossRef]

-

Risnes, I.; Abdelnoor, M.; Lundblad, R.; Baksaas, S.T.; Svennevig, J.L. Leg wound closure after saphenous vein harvesting in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: A prospective randomized study comparing intracutaneous, transcutaneous and zipper techniques. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2002, 36(6), 378–382. [CrossRef]

-

Shroyer, A. L.; Coombs, L. P.; Peterson, E. D.; Eiken, M. C.; DeLong, E. R.; Chen, A.; et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons: 30-day operative mortality and morbidity risk models. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2003, 75, 1856–1864. [CrossRef]

-

Berg, T.C.; Kjørstad, K.E.; Akselsen, P.E.; Seim, B.E.; Løwer, H.L.; Stenvik, M.N.; Sorknes, N.K.; Eriksen, H.-M. National surveillance of surgical site infections after coronary artery bypass grafting in Norway: Incidence and risk factors. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2011, 40(6), 1291–1297. [CrossRef]

- Kamensek, T., Kalisnik, J. M., Ledwon, M., Santarpino, G., Fittkau, M., Vogt, F. A., & Zibert, J. (2024). Improved early risk stratification of deep sternal wound infection risk after coronary artery bypass grafting. Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery, 19(1), 93. [CrossRef]

- Al-Zaru IM, Ammouri AA, Al-Hassan MA, Amr AA. Risk factors for deep sternal wound infections after cardiac surgery in Jordan. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(13-14):1873–81. [CrossRef]

- Gatti G, Dell'Angela L, Barbati G, Benussi B, Forti G, Gabrielli M, Rauber E, Luzzati R, Sinagra G, Pappalardo A. A predictive scoring system for deep sternal wound infection after bilateral internal thoracic artery grafting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49(3):910–7. [CrossRef]

- Borger MA, Rao V, Weisel RD, Ivanov J, Cohen G, Scully HE, David TE. Deep sternal wound infection: risk factors and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65(4):1050–6. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia JY, Pandey K, Rodrigues C, Mehta A, Joshi VR. Postoperative wound infection in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a prospective study with evaluation of risk factors. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2003;21(4):246–51. [CrossRef]

- Harrington G, Russo P, Spelman D, Borrell S, Watson K, Barr W, Martin R, Edmonds D, Cocks J, Greenbough J, Lowe J, Randle L, Castell J, Browne E, Bellis K, Aberline M. Surgical-site infection rates and risk factor analysis in coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25(6):472–6. [CrossRef]

- Russo PL, Spelman DW. A new surgical-site infection risk index using risk factors identified by multivariate analysis for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23(7):372–6. [CrossRef]

- Raja SG, Rochon M, Jarman JWE. Brompton Harefield Infection Score (BHIS): development and validation of a stratification tool for predicting risk of surgical site infection after coronary artery bypass grafting. Int J Surg. 2015;16(Pt A):69–73. [CrossRef]

- Abuzaid AA, Zaki M, Al Tarief H. Potential risk factors for surgical site infection after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting in a Bahrain cardiac centre: a retrospective, case-controlled study. Heart Views. 2015;16(3):79–84. [CrossRef]

- Raja S.G., Rochon M., Jarman J.W.E. Brompton Harefield Infection Score (BHIS): development and validation of a stratification tool for predicting risk of surgical site infection after coronary artery bypass grafting. International Journal of Surgery. 2015;16(Pt A):69–73. [CrossRef]

- Wilson A.P., Treasure T., Sturridge M.F., Grüneberg R.N. A scoring method (ASEPSIS) for postoperative wound infections for use in clinical trials of antibiotic prophylaxis. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):311–313. [CrossRef]

- Copanitsanou, P., Kechagias, V. A., Galanis, P., Grivas, T. B., & Wilson, P. (2019). Translation and validation of the Greek version of the "ASEPSIS" scoring method for orthopaedic wound infections. International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing, 33, 18–26. [CrossRef]

-

Ridderstolpe, L.; Gill, H.; Granfeldt, H.; et al. Superficial and deep sternal wound complications: Incidence, risk factors, and mortality. Eur. J. Cardio-Thorac. Surg. 2001, 20, 1168–1175. [CrossRef]

-

Al Salmi, H.; Elmahrouk, A.; Arafat, A. A.; Edrees, A.; Alshehri, M.; Wali, G.; Zabani, I.; Mahdi, N. A.; Jamjoom, A. Implementation of an evidence-based practice to decrease surgical site infection after coronary artery bypass grafting. J. Int. Med. Res. 2019, 47, 3491–3501. [CrossRef]

-

Risnes, I.; Abdelnoor, M.; Lundblad, R.; Baksaas, S.T.; Svennevig, J.L. Leg wound closure after saphenous vein harvesting in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting: A prospective randomized study comparing intracutaneous, transcutaneous and zipper techniques. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2002, 36(6), 378–382. [CrossRef]

- Medalion, B.; Mohr, R.; Frid, O.; et al. Should Bilateral Internal Thoracic Artery Grafting Be Used in Elderly Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting? Circulation 2013, 127, 2186–2193. [CrossRef]

- Lepelletier, D.; Perron, S.; Bizouarn, P.; et al. Surgical-Site Infection After Cardiac Surgery: Incidence, Microbiology, and Risk Factors. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2005, 26, 466–472. [CrossRef]

- Parisian Mediastinitis Study Group. Risk Factors for Deep Sternal Wound Infection After Sternotomy: A Prospective, Multicenter Study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1996, 111, 1200–1207. [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Lu, Z.; Zhu, H.; Xue, S.; Lian, F. Bilateral Internal Mammary Artery Grafting and Risk of Sternal Wound Infection: Evidence from Observational Studies. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2013, 95, 1938–1945. [CrossRef]

-

Meijs, A. P.; Koek, M. B. G.; Vos, M. C.; Geerlings, S. E.; Vogely, H. C.; de Greeff, S. C. The Effect of Body Mass Index on the Risk of Surgical Site Infection. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2019, 40(9), 991–996. [CrossRef]

-

Yeung, E.; Smith, S.; Scharf, M.; Wung, C.; Harsha, S.; Lawson, S.; Rockwell, R.; Reitknecht, F. BMI Disparities in Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Outcomes: A Single Center Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Database Analysis. Surg. Pract. Sci. 2022, 10, 100110. [CrossRef]

-

Martin, E.T.; Kaye, K.S.; Knott, C.; et al. Diabetes and risk of surgical site infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2016, 37(1), 88–99. [CrossRef]

- Lenz K., Brandt M., Fraund-Cremer S., Cremer J. Coronary artery bypass surgery in diabetic patients - risk factors for sternal wound infections. GMS Interdiscip Plast Reconstr Surg DGPW. 2016;5:Doc18. [CrossRef]

-

Sulzgruber, P.; Schnaubelt, S.; Koller, L.; Laufer, G.; Pilz, A.; Kazem, N.; Winter, M.P.; Steinlechner, B.; Andreas, M.; Fleck, T.; et al. An extended duration of the pre-operative hospitalization is associated with an increased risk of healthcare-associated infections after cardiac surgery. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8006. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).