1. Introduction

Detecting consciousness remains one of the most challenging tasks in clinical practice, and unsurprisingly, there is no universally accepted, objective definition of consciousness. Since consciousness cannot be directly observed, clinical assessment primarily relies on behavioral observations and inferences about the individual´s underlying conscious state, especially in patients with disorders of consciousness (DoC).

Typically, consciousness is characterized by two key components: wakefulness, defined as periods of spontaneous eye opening, and awareness, which refers to the ability to respond coherently to both internal and external stimuli. However, clinical evaluations often fall short in accurately identifying consciousness. Differentiating among various DoC categories - such as coma, vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (VS/UWS), and minimally conscious state (MCS) – as well as ruling out other neurological conditions like locked-in syndrome or akinetic mutism, is complex and prone to error. The diagnostic uncertainty leads to significant rates of misdiagnosis, which in turn affects treatment decisions, the allocation of diagnostic and rehabilitation resources, and the guidance provided to families regarding patient´s functional prognosis [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Diagnostic accuracy is significantly improved when standardized scales are used [

1,

3,

4], when patients are evaluated serially and at different times of the day [

5], given normal fluctuations in consciousness, and when complementary functional studies are incorporated [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Because the diagnosis determines the rehabilitation strategy and is highly correlated with the functional outcome, an accurate diagnosis is critical in the clinical approach to patients with disorders of consciousness. Various tools are employed in both clinical and research settings to assess consciousness following brain injury. For over twenty years, the Coma Recovery Scale–Revised (CRS-R) has been the most extensively utilized behavioral instrument for evaluating DoC, largely due to its robust psychometric qualities [

11].

Nevertheless, the CRS-R presents certain limitations [

12]. First, it is time-intensive as health professionals achieve an accurate diagnosis only after they observe people for a period and on more than one occasion. Second, it requires training, practice and mentorship from a healthcare professional experienced in using the scale. Lastly, while the scale yields total scores, these should not be used in isolation to determine a definitive diagnosis.

Recently, the Simplified Evaluation of CONsciousness Disorders (SECONDs) scale has been introduced as a brief assessment tool designed to evaluate the level of consciousness in patients with severe brain injury [

12,

13,

14,

15]. The same research team demonstrated that focusing the CRS-R assessment on its five most observed items - fixation, visual pursuit, reproducible movement to command, automatic motor response, and localization to noxious stimulation – was able to identify 99% of patients in a MCS [

16]. Based on these results, the SECONDs scale has been developed and has been validated in French [

12], in Spanish [

15], in Mandarin [

14], and in Italian [

17].

The objective of this study was to assess the validity of the Argentine adaptation of the SECONDs scale in adults with chronic DoC resulting from acquired brain injury by examining: (1) its concurrent validity against the widely accepted diagnostic standard for DoC; (2) its internal consistency as well as inter-rater and intra-rater reliability; and, (3) its clinical utility, evaluated through administration time and diagnostic agreement in identifying DoC.

2. Materials and Methods

Sampling and Study Design

This cross-sectional psychometric validation study was carried out between April and June 2024. We enrolled 29 DoC patients, 19 UWS/VS, 8 MCS, and 2 emergences from MCS (EMCS) hosted in the Santa Catalina Clinic in a dedicated unit for long-term brain injury care.

Inclusion criteria were as follows (1): age of 18 years or older, (2): impaired consciousness as determined by the attending physician based on CRS-R criteria for UWS, MCS, or EMCS (see

Table 1), (3): at least 4 weeks post traumatic or non-traumatic brain injury resulting in coma, defined by a Glasgow Coma Scale score below 8 at the time of acute admission. No upper limit was set for time since injury to better capture the clinical heterogeneity of this population; and (4): native Spanish speakers.

Exclusion criteria included diagnosed with coma, including irreversible coma or brain death; those who had received neuromuscular blocking agents or sedative medications within 24 hours prior to clinical evaluation; individuals with injuries affecting both eyes, tympanic membranes, or inner ears, patients with severe trauma to both upper or lower limbs: or those in unstable physical condition (e.g., absence of mechanical ventilation, ongoing sedation, active infection, or seizures).

Assessment

We designed a standardized neurobehavioral protocol specifically for patients with chronic DoC within the rehabilitation setting. The clinical evaluation aims to assess the patient's level of alertness in response to verbal and painful stimuli, establish the severity of consciousness impairment, and inform ongoing monitoring and therapeutic decision-making. Based on international recommendations, the clinical protocol aims to: 1) rule out all those confounding clinical factors; 2) use a standardized and validated scale such as the CRS-R [

18] and SECONDs [

12]; 3) avoid making a diagnosis only with the first evaluation, trying as far as possible to plan at least 5 evaluation sessions in the term of 2 weeks; 4) review the pharmacological scheme that allows planning a gradual and progressive decrease of drugs that alter neuroplasticity and the incorporation of drugs that stimulate consciousness in adequate doses; 5) request the necessary complementary methods to improve the precision of the clinical interpretation and to exclude other causes; 6) if available, functional studies (MRI and/or EEG) can be requested when there is suspicion of covert consciousness.

Measures

1. Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R)

The CRS-R [

18] comprises six subscales designed to evaluate auditory function, receptive and expressive language, visuoperception, communication abilities, motor functions, and arousal level. These subscales included hierarchically organized items that reflect behaviors mediated by brainstem, subcortical, and cortical regions: auditory, visual, motor, oromotor/verbal, communication, and arousal functions. The total CRS-R score is obtained by summing the six subscale scores, ranging from 0 to 23.

Within each subscale, the lowest scoring items correspond to reflexive responses, while the scores indicate cognitively mediated behaviors. Scoring follows standardized criteria based on the presence or absence of clearly defined behavioral responses. Additionally, the scoring form links specific behaviors to diagnostic categories, facilitating clinical interpretation.

2. Simplified Evaluation of CONsciousness Disorders (SECONDs)

The SECONDs scale [

12,

13] is composed of eight items arranged in order of increasing complexity, adapted from the CRS-R: arousal response (scored 1), localization to pain (2), visual fixation (3), visual pursuit (4), oriented behaviors (5), command-following (6), intentional communication (scored 7), and functional communication (8). The total score corresponds to a diagnostic category, ranging from 0 (coma), 1 (UWS), 2-5 (MCS-), 6-7 (MCS+) to 8 (EMCS).

Additionally, the authors propose an index score calculated by summing the points earned across all items assessed, with a possible range from 0 to 100. The SECONDs scale has demonstrated to be a rapid, reliable and user-friendly tool for diagnosing DoC.

Translation

With the original author´s permission [

12,

13], the SECONDs scale was translated into Spanish following a rigorous process. The original English version of the SECONDs includes detailed administration guidelines to ensure standardized and reproducible use [

13]. First, a native Spanish speaker translated the scale from English to Spanish. Subsequently, a professional translator performed a back-translation from Spanish to English. This back-translated version was reviewed by the validation’s team, and after two rounds of revisions, the final Argentine Spanish Version of the SECONDs was approved. The same process was repeated with the Spanish version [

15].

Procedure

Throughout the evaluation period, all patients continued to receive standard medical treatment and rehabilitation. The study involved three physical therapists (Raters A, B, and C), all of whom were new to using the SECONDs scale. Prior to data collection, the raters underwent training on the administration of the SECONDs following the published guidelines [

13].

Patients were diagnosed with UWS, MCS, or EMCS based on CRS-R assessments according to the Aspen Workgroup criteria, by a senior neurologist (see

Table 1).

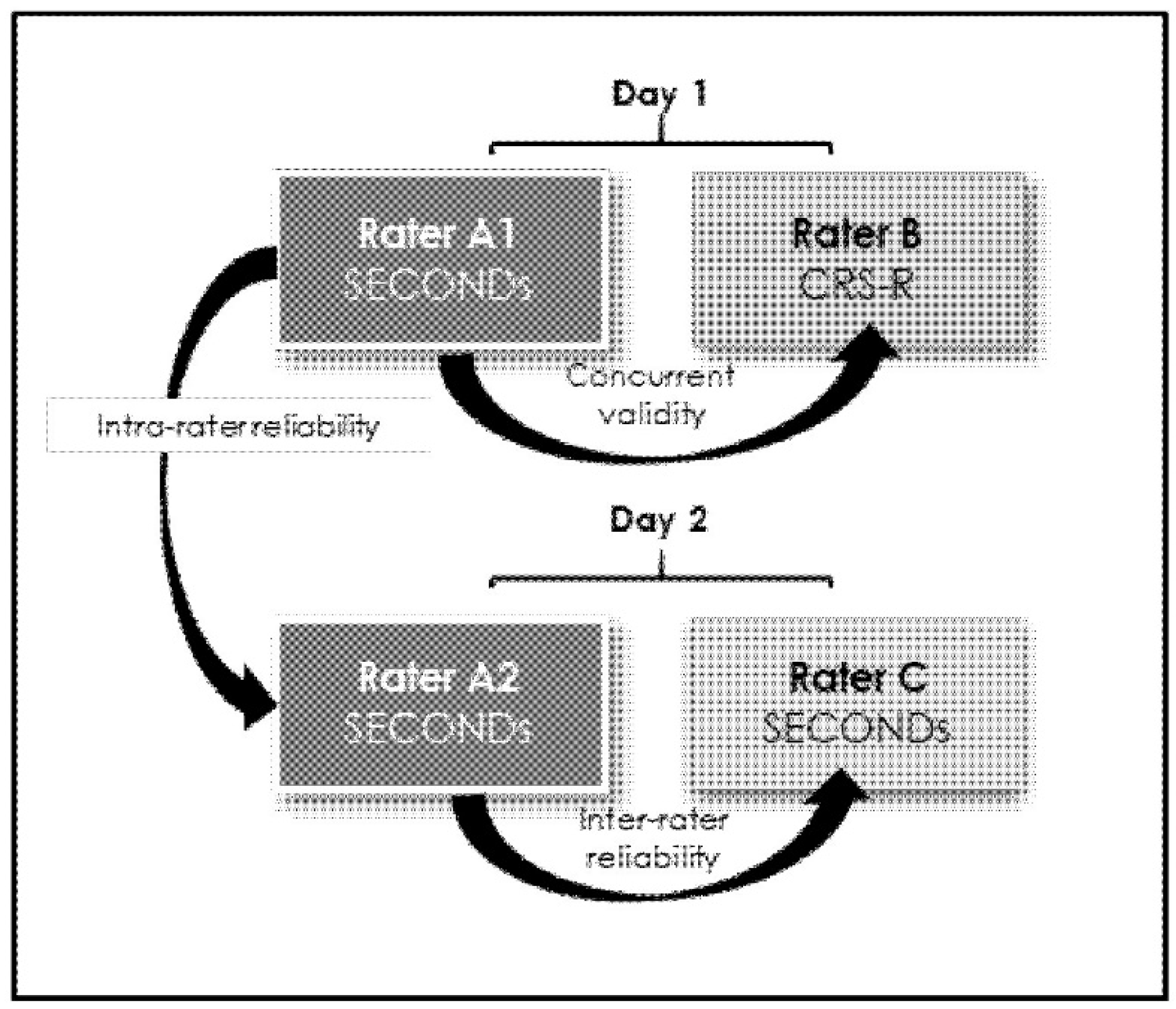

On the first day, Rater A performed the initial SECONDs assessment (A1), while Rater B conducted the CRS-R evaluation on the same day. To minimize fluctuations in patients’ responsiveness and avoid fatigue, a 40 to 60-minute interval was maintained between the two assessments. The order of these assessment (A1 and B) was randomized. Although both raters visited the patients simultaneously, only one conducted the assessment while the other waited outside, preventing observation or knowledge of each other´s results; assessments were submitted independently.

On the following day, Rater A repeated the SECONDs assessment (A2), and Rater C administered de SECONDs once. The same time interval was maintained between these two evaluations (see

Figure 1). All raters applied diagnostic criteria consistent with senior neurologists to classify patients’ levels of consciousness impairment as UWS, MCS, or EMCS.

Statistical Analysis

Data analyses were performed using SPSS statistics (version 22, IBM Corp., Chicago, IL). Normally distributed continuous variables are presents as mean with standard deviations, while for non-normally distributed variables are reported as medians with interquartile ranges. Categorical data are summarized using counts and prevalence rates.

To assess concurrent validity, Spearman´s partial correlation was used to examine relationships between the SECONDs subscales, the additional index and the total SECONDs score compared to the total CRS-R score. Internal consistency of the SECONDs was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and inter-subscale correlation coefficients.

Inter-rater and intra-rater reliability were estimated through intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC), with values between .60 and .74 indicating good clinical significance, and values ≥.75 considered excellent. Agreement between diagnoses made by CRS-R and SECONDs raters was assessed with weighted Kappa coefficients.

The Mann-Whitney U test was employed to compare administration times between the SECONDs and the CRS-R. Statistical significance was set at p <.05 with a 95% confidence interval for all tests.

3. Results

A total of 29 individuals with DoC were evaluated over two consecutive days by three independent, blinded raters. On one day, each participant underwent both a CRS- R and a SECONDs assessment, while on the other day, two SECONDs assessments were administered. The mean age of the cohort was 55.48 years (SD=16.28), with 16 participants (55%) being male. Regarding etiology, 5 individuals (17%) had experienced a stroke, 9 (31%) had sustained traumatic brain injury, and 15 (52%) had an anoxic brain injury. The median time since brain injury was 20 months (interquartile range: 51.50 months).

Table 2 depicts the characteristics of this study’s participants.

3.1. Concurrent validity

Table 3 presents the correlation coefficients between the SECONDs scale and the CRS-R. The Spearman correlation was significant for the total scores of the SECONDs and CRS-R (r = .73; p < .001), as well as for the additional index score of the SECONDs (r = .81, p < .001). Each subscale of the SECONDs additional index also showed significant associations with the CRS-R, with correlation coefficients ranging from .43 to .73 (all p < .05).

3.2. Internal Consistency

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the additional index score of the SECONDs scale was .77, indicating a reasonably homogeneous measure of neurobehavioral function in patients with DoC. Removing any individual subscale had minimal impact on the overall Cronbach’s alpha. Correlations among the subscales (see

Table 4) were generally satisfactory for most items, except for the Arousal and Pain localization subscales, which showed weaker correlations. The strongest interrelationships were observed among the Oriented behaviors, Visual pursuit, and Visual fixation subscales.

3.3. Reliability

Table 5 summarizes the intra-rater and inter-rater correlation coefficients (ICCs) for both the total score and the additional index score of the SECONDs scale. Intra-rater reliability was nearly perfect (ICC = .98; p < .001), demonstrating excellent consistency when assessments were repeated by the same evaluator. All ICC values were statistically significant except for the Pain Localization subscale.

Inter-rater reliability for the total SECONDs score was also high (ICC = .86; p < .001), indicating the diagnostic accuracy remained robust across different raters. However, the Pain Localization and Arousal subscales showed lower inter-rater reliability and did not reach statistical significance.

3.4. Clinical Utility

The median administration time for the SECONDs scale was significantly shorter than that of the CSR-R (10 minutes, IQR 9-12 versus 15 minutes, IQR 10-16; U = 172.5, p < 0.001).

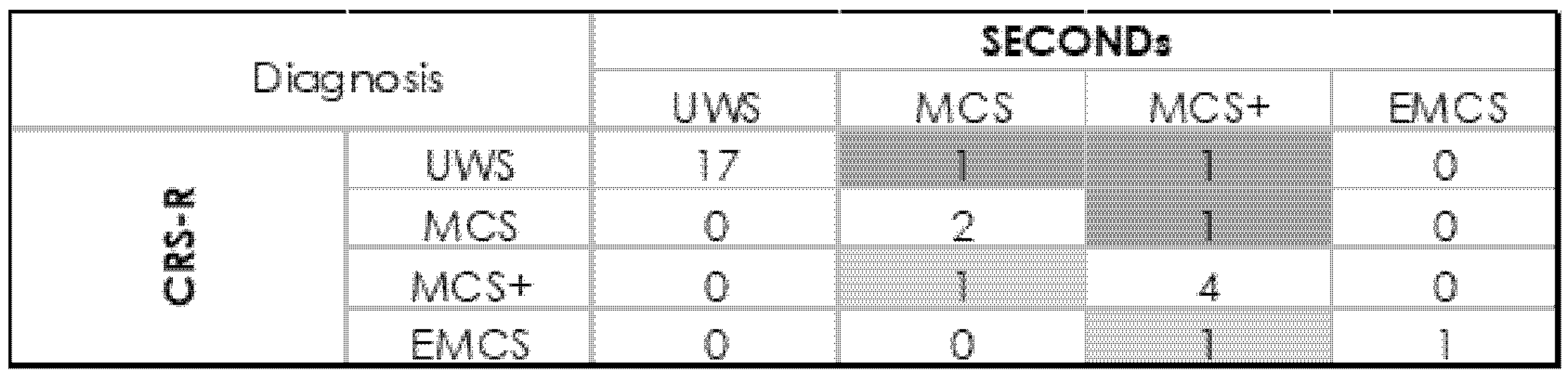

In this study, 29 participants were assessed using the CRS-R, yielding diagnoses of EMCS in 2 patients, MCS in 8, and UWS in 18. Diagnostic agreement between raters was high: 25 out of 29 cases (κ = .75; p<.001) between Raters A1 and B, 26 out of 29 (κ = .82; p<.001) between A1 and A2, and 26 out of 29 (κ = .82; p<.001) between A1 and C.

When distinguishing between MCS - and MCS+ categories (see

Figure 2), diagnostic disagreement between the SECONDs and CRS-R scales occurred in 5 of 29 participants (17%). Among these, 3 participants received a higher level of awareness diagnosis with the SECONDs compared to the CRS-R, while 2 participants were better classified by the CRS-R. These discrepancies primary involved differences in detecting visual pursuit (observed only with SECONDs in 1 participant and only with CRS-R in another) and command-following (detected only with SECONDs in 2 participants and only with CRS-R in 1 participant).

4. Discussion

This study constitutes the first validation of the Argentine adaptation of the SECONDs scale in a cohort of patients with DoC secondary to acquired brain injury. Our findings demonstrate that the SECONDs scale is a valid, reliable, and efficient tool for assessing of consciousness in this population.

We found strong concurrent validity with the established CRS-R scale, demonstrated by significant correlations between the total scores of both instruments, which increased further when including the additional SECONDs index. These findings align with previous research [

12,

14,

15,

17], confirming that the Argentine version of the SECONDs scale effectively measures levels of consciousness.

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient supports good structure validity for the additional index score. Although the Arousal and Pain Localization subscales showed weaker correlations, their exclusion did not affect the scale´s overall internal consistency. The Pain Localization subscale is conditional and scores zero on the additional index when command-following is present; fluctuations in arousal can significantly impact behavioral responsiveness. While arousal changes naturally influence total SECONDs scores, this study did not specifically examine this effect. The additional index aims to capture subtle clinical changes over repeated assessments without altering the overall diagnosis [

13]. Thus, evaluating arousal and pain localization remains essential to reflect DoC diagnoses accurately.

Our results align with previous validation studies. For instance, Aubinet et al. [

12] reported excellent inter-rater reliability (ICC = .93) and strong concurrent validity with the CRS-R (r = .80), findings that are comparable to those observed in our study (inter-rater ICC = .86; concurrent validity r = .73). Similarly, the Mandarin [

14], Spanish [

15], and Italian [

17] versions showed excellent reliability and validity, supporting the scale´s robustness across languages and cultures. Our study confirms adequate reliability for both the total and additional index scores, demonstrating stability across raters and repeated measures.

Regarding diagnostic agreement, our kappa values (κ = .75 to .82) are in line with the original validation (κ = .84) [

12], Spanish version (κ = .87) [

15], and Italian version (κ = .83) [

17], reinforcing the SECONDs´ capacity to distinguish consciousness reliably. Discrepancies with the CRS-R mainly involved behaviors assessed differently, particularly in visual pursuit and command-following subscales. Variations in assessment conditions and patient variability likely contributed [

12].

A practical advantage of the SECONDs scales is its shorter administration time compared to the CRS-R (median 10 minutes vs. 15 minutes; U = 172.5, p < 0.001), facilitating its use in settings with limited staff or time constraints [12, 17].

Clinical implications

The Argentine version of the SECONDs scale provides valuable advantages for evaluating patients with prolonged DoC, particularly in low- and middle-income countries where resources and specialized training are often limited. Its brevity and ease of use enable more frequent monitoring, potentially leading to earlier detection of clinical changes and timely rehabilitation adjustments. Strong concordance with CRS-R supports its use as an alternative or complementary tool. The validated Spanish version fills a critical gap, as most DoC tools are in English or other major languages.

Study Limitations

The small sample size (n = 29) may limit generalizability. Larger multicenter studies are needed to confirm psychometric properties across diverse populations. Participants came from a single specialized rehabilitation center, possibly introducing selection bias. Raters were physical therapists trained in SECONDs; performance by other professionals or in less controlled settings remains to be evaluated.

This study did not assess sensitivity to subtle changes over time or intervention response; future research should explore longitudinal utility.

Future Directions

Further studies in larger, heterogeneous samples, and other Spanish-speaking countries is needed. Studies on responsiveness to clinical change and predictive value for outcomes would be valuable. Comparing SECONDs with neuroimaging and electrophysiological markers could clarify its role in multimodal assessments.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms the Argentine SECONDs scale as a valid, reliable, and efficient tool for evaluating prolonged DoC. Its integration into neurobehavioral assessments may improve diagnostic accuracy and patient care, particularly in resource-limited settings. Ongoing research will further elucidate its added value in comprehensive evaluation and management.

Author Contributions

MJR was responsible for conceptualization, data management, investigation, methodology design, project oversight, supervision, drafting the initial manuscript, and revising and editing the final text. MPS contributed to data collection, participated in the investigation, and assisted in the review and editing of the manuscript. PA, VG, YG, MM, and FD were involved in data acquisition, investigation, and provided critical feedback during manuscript revision and editing. HP participated in the investigation and was involved in the review and editing process.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Santa Catalina Neurorehabilitación Clínica (protocol code 2025-01, approval date January 31, 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all patients and their families for their participation and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CRS-R |

Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R) |

| DoC |

Disorders of Consciousness |

| SECONDs |

Simplified Evaluation of Disorders of

Consciousness |

References

- Bodien, Y.G.; Carlowicz, C.A.; Chatelle, C.; Giacino, J.T. Sensitivity and specificity of the coma recovery scale-revised total score in detection of conscious awareness. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016, 97, 490–492.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatelle, C.; Bodien, Y.G.; Carlowicz, C.; Wannez, S.; Charland-Verville, V.; Gosseries, O.; et al. Detection and Interpretation of Impossible and Improbable Coma Recovery Scale-Revised Scores. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016, 97, 1295–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosco, A.; Lancioni, G.E.; Belardinelli, M.O.; Singh, N.N.; O’Reilly, M.F.; Sigafoos, J. Vegetative state: Efforts to curb misdiagnosis. Cogn Process 2010, 11, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnakers, C.; Vanhaudenhuyse, A.; Giacino, J.; Ventura, M.; Boly, M.; Majerus, S.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the vegetative and minimally conscious state: Clinical consensus versus standardized neurobehavioral assessment. BMC Neurol. 2009, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wannez, S.; Heine, L.; Thonnard, M.; Gosseries, O.; Laureys, S. The repetition of behavioral assessments in diagnosis of disorders of consciousness. Ann Neurol 2017, 81, 883–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stender, J.; Gosseries, O.; Bruno, M.A.; Charland-Verville, V.; Vanhaudenhuyse, A.; Demertzi, A.; et al. Diagnostic precision of PET imaging and functional MRI in disorders of consciousness: a clinical validation study. Lancet 2014, 384, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curley, W.H.; Forgacs, P.B.; Voss, H.U.; Conte, M.M.; Schiff, N.D. Characterization of EEG signals revealing covert cognition in the injured brain. Brain 2018, 141, 1404–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Napolitani, M.; Bodart, O.; Canali, P.; Seregni, F.; Casali, A.; Laureys, S.; et al. Transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with high-density EEG in altered states of consciousness. Brain Inj 2014, 28, 1180–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodien, Y.G.; Giacino, J.T.; Edlow, B.L. Functional MRI Motor Imagery Tasks to Detect Command Following in Traumatic Disorders of Consciousness. Front Neurol 2017, 8, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billeri, L.; Filoni, S.; Russo, E.F.; Portaro, S.; Militi, D.; Calabrò, R.S.; et al. Toward improving diagnostic strategies in chronic disorders of consciousness: An overview on the (re-)emergent role of neurophysiology. Brain Sci 2020, 10, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giacino, J.T.; Whyte, J.; Nakase-Richardson, R.; Katz, D.I.; Arciniegas, D.B.; Blum, S.; et al. Minimum Competency Recommendations for Programs That Provide Rehabilitation Services for Persons With Disorders of Consciousness: A Position Statement of the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living and Rehabilitation Research Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2020, 101, 1072–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubinet, C.; Cassol, H.; Bodart, O.; Sanz, L.R.D.; Wannez, S.; Martial, C.; et al. Simplified evaluation of CONsciousness disorders (SECONDs) in individuals with severe brain injury: A validation study. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2021, 64, 101432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanz, L.R.D.; Aubinet, C.; Cassol, H.; Bodart, O.; Wannez, S.; Bonin, E.A.C.; et al. Seconds administration guidelines: A fast tool to assess consciousness in brain-injured patients. J Vis Exp 2021, 168, 10.3791–61968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Sun, L.; Cheng, L.; Hu, N.; Chen, Y.; Sanz, L.R.D.; et al. Validation of the simplified evaluation of consciousness disorders (SECONDs) scale in Mandarin. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2023, 66, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noe, E.; Llorens, R.; Colomer, C.; Navarro, M.; o´Valle, M.; Moliner, B.; et al. Spanish validation of the Simplified Evaluation of Consciousness disorders (SECONDS). Neuroloogie & Rehabilitation 2023, 29(S1), S102.

- Wannez, S.; Gosseries, O.; Azzolini, D.; Martial, C.; Cassol, H.; Aubinet, C.; et al. Prevalence of coma-recovery scale-revised signs of consciousness in patients in minimally conscious state. Neuropsychol Rehabil 2018, 28, 1350–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakiki. B.; Pancani, S.; De Nisco, A.; et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and multicentric validation of the Italian version of the Simplified Evaluation of CONsciousness Disorders (SECONDs). PLoS One 2025, 20, e0317626. [CrossRef]

- Giacino, J.T.; Kalmar, K.; Whyte, J. The JFK Coma Recovery Scale-Revised: Measurement characteristics and diagnostic utility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004, 85, 2020–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossuyt, P.M.; Reitsma, J.B.; Bruns, D.E.; Gatsonis, C.A.; Glasziou, P.P.; Irwig, L.M.; et al. The STARD statement for reporting studies of diagnostic accuracy: explanation and elaboration. The Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy Group. Croat Med J 2003, 44, 639–650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).