1. Introduction

Traumatic Brain Injuries (TBI) represent a leading cause of mortality and long-term disability worldwide, with approximately 1.3 million new cases reported annually. These injuries, caused by external mechanical forces such as blunt trauma, falls, or vehicle accidents, can lead to a range of outcomes from full recovery to severe neurological impairment or death. A major factor influencing the prognosis of TBI patients is the development of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) [

1,

2], a condition where the pressure inside the skull exceeds normal levels, often leading to severe complications such as cerebral herniation and, ultimately, death. According to studies, the risk of complications like disability following a TBI can be as high as 50%, with increased ICP being a key contributor to such adverse outcomes [

3].

In Thailand, traumatic brain injuries are a significant public health concern. Data from the Ministry of Public Health reveals that the country experiences a mortality rate of 36 per 100,000 population annually due to brain injuries. This statistic highlights the urgent need for improved clinical protocols to manage TBI patients, especially in mitigating the effects of increased ICP. The financial burden associated with managing TBI cases is also considerable, with over 2.46 billion baht spent annually in the healthcare system to treat these patients, underscoring the economic importance of efficient treatment strategies and preventive measures.

Samut Prakan Hospital, a regional trauma care center in Thailand, has played a pivotal role in managing TBI cases, having been designated as an Excellent Trauma Center Level 3 between 2020 and 2022 [

4]. The hospital treats an average of 358 brain injury patients annually, with reported mortality rates of 15.43%, 18.47%, and 15.92% over the three-year period. These mortality rates are closely associated with increased intracranial pressure (IICP) [

2,

3,

4,

5], which commonly occurs within the first 72 hours following brain trauma or surgery. Research shows that the risk of IICP is highest within the first six hours after surgery, making timely detection and intervention critical to improving survival rates [

6].

The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), a widely used clinical tool for assessing consciousness in TBI patients, is strongly linked to the development of ICP. Studies have consistently demonstrated that patients with a GCS score of less than 8 are at a significantly higher risk of developing IICP, which correlates with higher mortality rates. Monitoring changes in the GCS over time, particularly eye-opening, motor response, and verbal response, provides valuable insights into the neurological status of the patient and can serve as an early warning sign for impending IICP.

However, while GCS remains an essential component of TBI management, other clinical indicators also play a crucial role in the early detection of ICP. Cushing’s reflex—a triad of physiological responses characterized by increased systolic blood pressure, irregular breathing patterns (bradypnea), and a slow heart rate (bradycardia)—is a key clinical marker for increased ICP. Vital signs such as respiratory rate, pulse rate, and blood pressure fluctuations within the first 72 hours post-injury [

7] are critical in the early identification of patients at risk for IICP, particularly those with severe TBI. Despite the established significance of these clinical parameters, reliable external detection tools for ICP remain limited, highlighting the need for further research and technological advancements in this area. In clinical settings, the absence of direct, non-invasive methods for monitoring ICP presents a challenge for healthcare professionals. Invasive methods, such as ventriculostomy and intracranial pressure monitoring devices, though effective, are associated with complications like infection and hemorrhage. As such, there is an ongoing need for the development of reliable, non-invasive tools that can accurately predict ICP using available clinical data, including GCS and vital signs. Identifying risk factors associated with ICP in TBI patients, particularly in the early stages, can lead to better-targeted interventions, reducing the incidence of complications and improving long-term outcomes.

Given the high mortality and morbidity rates associated with TBI and the economic burden on healthcare systems, a systematic approach to assessing and monitoring ICP is vital. Early detection of ICP and timely intervention can significantly reduce complications, shorten hospital stays, and lower healthcare costs. Research has shown that improving ICP assessment tools and implementing preventive strategies could reduce hospital mortality by up to 11.6 times in certain populations. Moreover, enhancing the accuracy of ICP detection within the critical window—typically the first 72 hours [

7] following brain trauma—can lead to substantial improvements in patient outcomes.

This research seeks to validate early detection methods for ICP and identify the key risk factors associated with its development in adult TBI patients. The study will focus on assessing clinical parameters such as GCS, respiratory rate, pulse rate, and blood pressure in the first 72 hours after injury. By identifying the critical indicators of ICP and developing a reliable detection model, the findings aim to contribute to the development of standardized nursing practices that improve patient safety, reduce mortality, and enhance the overall quality of care for TBI patients.

The objectives of this our study align with the broader goals of the Ministry of Public Health in Thailand, which emphasize the importance of building high-performance healthcare organizations capable of delivering world-class patient care. Developing effective ICP assessment tools and protocols will not only help to prevent complications in TBI patients but will also serve as a model for improving trauma care across the healthcare system. This research holds the potential to inform national health policy and contribute to the ongoing efforts to reduce the mortality and disability burden associated with traumatic brain injuries.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This descriptive study was conducted at Samut Prakan Hospital, a regional trauma center in Samut Prakan, Thailand. The data collection period spanned from October 10, 2023, to October 10, 2024. The study focused on validating early detection methods for increased intracranial pressure (ICP) and identifying risk factors associated with ICP in patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI). The hospital serves as a Level 3 Excellent Trauma Center, and the study was approved by the Samut Prakan Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB No. Oh00567).

Study Sample

A sample size of 215 subjects was calculated using the Krejcie and Morgan formula [

8], ensuring a representative population size for statistical analysis. Purposive sampling was used to select participants who met the inclusion criteria. The study population consisted of TBI patients aged 12 years or older, admitted to Samut Prakan Hospital within 72 hours of injury onset. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they exhibited symptoms of TBI requiring monitoring for potential ICP elevation.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (1) patients aged ≥ 12 years, (2) admitted within 72 hours post-injury, and (3) diagnosed with TBI. Exclusion criteria included: (1) a history of prior head surgery before this admission, (2) pre-existing psychiatric disorders or neurological conditions, and (3) multiple traumas affecting the function and mobility of other organs.

Data Collection

Data was collected from electronic nursing records, which included detailed patient information such as demographics, clinical characteristics, and monitoring results. The primary clinical tools used for assessing the severity of TBI were the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) [

9] and the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) [

10]. The GCS was used at baseline and throughout the hospital stay to evaluate consciousness and neurological function, while the GOS was used to measure patient recovery at discharge. Additional clinical parameters, such as vital signs (temperature, respiratory rate, pulse rate, and blood pressure), were recorded at regular intervals to detect changes that could indicate elevated ICP. Cushing’s reflex characterized by an abnormal respiratory rate, elevated blood pressure, and bradycardia was specifically monitored as a key indicator of ICP. Patient outcomes, including mortality and recovery status, were assessed at discharge using the GOS. Hospital-related factors, such as length of stay and costs, were also recorded for further analysis.

Definitions

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): Defined as an injury to the brain caused by external mechanical force, potentially leading to temporary or permanent neurological dysfunction.

Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP): Defined as intracranial pressure exceeding 15 mmHg, which can result in compression of brain structures and impaired cerebral perfusion.

Cushing’s Reflex: A physiological response to increased ICP, involving elevated systolic blood pressure, decreased heart rate (bradycardia), and abnormal respiratory patterns (bradypnea).

Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS): A clinical scale used to assess the level of consciousness in TBI patients, with scores ranging from 3 (severe impairment) to 15 (normal) [

9].

Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS): A scale used to assess the long-term recovery of TBI patients, with scores ranging from 1 (death) to 5 (good recovery) [

10].

Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Samut Prakan Hospital Ethics Committee (IRB No. Oh00567), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians before data collection. The study adhered to the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring participant confidentiality and the right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequences. Personal identifying information was anonymized, and all data was securely stored to prevent unauthorized access.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software, version 27.0.1. Descriptive statistics, such as mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage, were used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. For inferential statistics, Chi-square tests were used to assess associations between categorical variables. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to examine relationships between continuous variables, such as GCS scores and vital signs, and their impact on ICP levels.

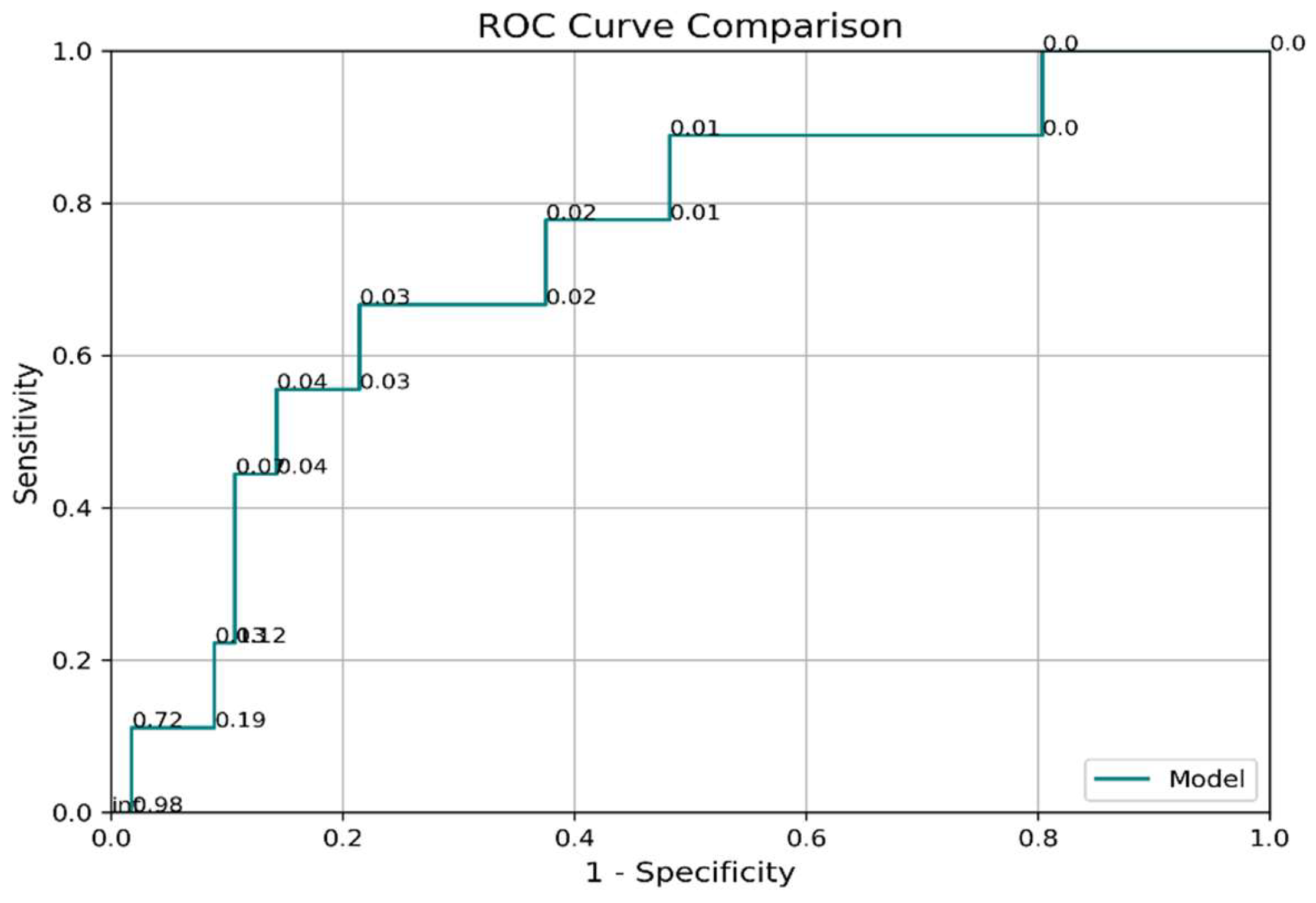

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare the means of different groups, including those with mild, moderate, and severe TBI based on the GCS. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify the factors associated with the early detection of ICP, with p-values less than 0.05 considered statistically significant. The predictive accuracy of the detection model was assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), providing an indication of the model’s overall performance.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome of the study was the rate of elevated ICP, diagnosed by physicians based on clinical signs and imaging findings. Secondary outcomes included the hospital mortality rate and the GOS score at discharge. Patients’ recovery was categorized according to the GOS as follows: (1) death, (2) persistent vegetative state, (3) severe disability, (4) moderate disability, and (5) good recovery.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Data

A total of 215 patients meeting the inclusion criteria were enrolled, with the majority being male (79.1%). The most represented age group was 21–40 years (29.3%). A significant proportion (71.2%) of participants had no pre-existing medical conditions, while 28.8% presented with comorbidities, predominantly non-communicable diseases (97.2%) such as diabetes and hypertension. Additionally, 93% of participants had not received anticoagulant therapy prior to admission, minimizing potential confounders in the clinical progression of TBI. These characteristics provided a diverse yet clinically relevant population for the study. (

Table 1).

3.2. Correlation Between Clinical Parameters and Increased Intracranial Pressure (ICP)

Key clinical parameters demonstrated significant associations with increased ICP. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) scores, particularly the components for eye-opening, motor response, and verbal response, negatively correlated with ICP both in the initial phase of injury and during subsequent changes in patient status (p < .001). Hospitalization-related factors such as length of stay and treatment costs were positively correlated with elevated ICP (p < .001), indicating the economic and resource implications of severe TBI.

Respiratory rate changes, a key element of Cushing’s reflex, showed borderline significance (p = 0.069). However, other vital signs, such as systolic blood pressure and pulse rate, were less predictive of increased ICP in isolation. These findings emphasize the multifaceted nature of ICP dynamics in TBI management (

Table 1).

3.4. Predictive Accuracy of Cushing’s Reflex for Increased ICP

Logistic regression analysis evaluated the utility of Cushing’s reflex as an early detection tool for increased ICP. While the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the model was moderate at 0.74 (95% CI: 0.54–0.93), sensitivity (67%) and specificity (78%) indicated limited predictive reliability in clinical settings. Importantly, the delayed manifestation of Cushing’s reflex—characterized by increased blood pressure and reduced heart rate—reflects advanced stages of ICP increase, often correlating with brainstem compression or herniation (

Table 3,

Figure 1). Ability to Detect ICP Using Cushing’s Reflex

3.3. Factors Associated with Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) Scores

The Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) was used to evaluate patient recovery at discharge, highlighting the impact of clinical and physiological factors on outcomes. Initial and evolving GCS scores were strongly associated with GOS categories, with lower GCS scores linked to poorer outcomes such as death or severe disability (p < .001). Physiological indicators like pulse rate and respiratory rate also exhibited statistically significant associations with recovery trajectories (p < .05), underscoring the importance of continuous monitoring during hospitalization (

Table 2).

Hospitalization duration and associated costs were higher among patients with poorer outcomes, suggesting that more severe ICP increases lead to longer and more expensive care.

Table 2.

ANOVA Test for Factors and Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS).

Table 2.

ANOVA Test for Factors and Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS).

| Variables |

F |

p-value |

Significant Pairwise Comparison |

GCS score (initial phase)

Eye score (initial phase) |

26.63 |

<.001** |

(1) vs. (3), (2) vs. (3) |

| 13.23 |

<.001** |

(2) vs. (3) |

Motor score (initial phase)

Verbal score (initial phase) |

20.56 |

<.001** |

(1) vs. (3), (2) vs. (3) |

| 28.56 |

<.001** |

(1) vs. (3), (2) vs. (3) |

| Pulse rate (initial phase) |

3.68 |

0.027* |

(1) vs. (3), (1) vs. (3) |

GCS score (changed phase)

Eye score (changed phase)

Motor score (changed phase)

Verbal score (changed phase) |

50.08 |

<.001** |

(1) vs. (3), (2) vs. (3) |

| 33.60 |

<.001** |

(1) vs. (3), (2) vs. (3) |

| 46.92 |

<.001** |

(1) vs. (3), (2) vs. (3) |

| 30.77 |

<.001** |

(1) vs. (3), (2) vs. (3) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure (changed phase) |

3.18 |

0.043* |

(1) vs. (3), (1) vs. (3) |

| Respiratory rate (changed phase) |

7.95 |

<.001** |

(1) vs. (3), (2) vs. (3) |

| Length of stay |

25.08 |

<.001 |

(1) vs. (2), (2) vs. (3) |

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Analysis for Cushing’s Reflex and ICP Detection.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Analysis for Cushing’s Reflex and ICP Detection.

| Variables |

Odds Ratio |

95% CI |

p-Value |

| GCS score |

0.45 |

0.32–0.67 |

<.001** |

| Respiratory rate |

1.15 |

0.97–1.38 |

0.074 |

| Pulse rate |

1.12 |

0.89–1.46 |

0.093 |

| Systolic Blood Pressure |

1.04 |

0.98–1.09 |

0.131 |

4. Discussion

The findings of this study emphasize the importance of early detection in managing elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) among patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI). Timely identification of ICP is critical to initiating interventions that mitigate the risk of secondary brain injury, ultimately improving patient outcomes. This study reinforces the utility of clinical tools such as the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and vital sign monitoring, including components of Cushing’s reflex, as essential methods for predicting and managing ICP in TBI patients.

Predictive Value of GCS and Vital Signs

The significant correlation between lower GCS scores and elevated ICP underscores the reliability of GCS as a primary tool in neurological assessments. Patients with lower scores in the eye-opening, motor response, and verbal response categories were more likely to experience elevated ICP. This finding is consistent with previous research that highlights GCS as a robust predictor of TBI outcomes, particularly during the acute phase of injury [

12,

13,

14]. These results underline the necessity of continuous GCS monitoring during the first critical 72 hours post-injury when ICP risks are highest.

In addition to GCS, changes in vital signs, such as respiratory rate—an element of Cushing’s reflex—also correlated significantly with ICP. This observation supports existing evidence that respiratory irregularities, elevated systolic blood pressure, and bradycardia are physiological responses to increased ICP [

16,

17,

18,

19]. However, it is important to note that reliance on Cushing’s reflex for detection may be limited by its late-stage manifestation, which often coincides with severe brainstem compression or herniation. These findings suggest that while vital signs remain valuable components of ICP monitoring, they should be used in conjunction with other early detection methods to enhance accuracy and timeliness.

Hospital Outcomes and Clinical Implications

The association between elevated ICP and adverse hospital outcomes, such as prolonged length of stay and increased treatment costs, highlights the significant resource burden associated with severe TBI. Patients with higher ICP required longer hospitalization and more intensive care, reflecting the complexity of managing ICP-related complications. These findings underscore the economic and logistical advantages of improving early detection and intervention for ICP.

Aggressive monitoring and prompt therapeutic strategies for high-risk patients could stabilize ICP more effectively, reducing hospitalization durations and associated healthcare costs. Early implementation of ICP monitoring, combined with targeted treatments such as osmotherapy, hyperventilation, or decompressive craniectomy, may yield improved outcomes and resource efficiency. These strategies align with prior research suggesting that timely ICP management contributes to better recovery trajectories and reduced healthcare expenditure [

21,

22].

Comparison with Previous Studies

This study’s findings are in agreement with earlier research, such as Gotts and Matthay [

22], which identified older patients with comorbidities—especially non-communicable diseases like diabetes and hypertension—as being at higher risk for complications, including elevated ICP and sepsis. In our cohort, patients with underlying conditions were disproportionately represented among those with increased ICP, emphasizing the need for individualized monitoring and treatment plans in this population.

Regarding the predictive accuracy of our logistic regression model, the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) of 0.74 indicates moderate reliability for detecting ICP based on GCS and vital sign changes. While lower than the predictive performance reported in some studies, such as Ghanem-Zoubi et al. [

25], this discrepancy may reflect variations in sample size, settings, or the specific patient populations studied. Future research incorporating larger, more diverse samples and advanced predictive models, such as machine learning algorithms, could enhance the sensitivity and specificity of ICP detection methods and improve their generalizability across clinical settings.

Implications and Limitations

The study provides insights into the utility of GCS and Cushing’s reflex as clinical tools for monitoring ICP in TBI patients. However, reliance on Cushing’s reflex as a predictive indicator is problematic due to its late-stage presentation, which occurs after critical physiological thresholds are crossed. This emphasizes the need for integrating earlier, more sensitive indicators alongside multimodal monitoring strategies to improve ICP management and outcomes.

Although this study provides valuable insights, certain limitations warrant consideration. First, the reliance on GCS and Cushing’s reflex may overlook other early biomarkers of ICP. Additionally, the study’s moderate predictive accuracy highlights the need for further refinement of detection models. Future studies should explore the integration of multimodal monitoring tools, including advanced imaging and intracranial sensors, to complement clinical assessments and improve early detection of ICP. Furthermore, research focusing on early interventions and their cost-effectiveness in reducing hospital stays and improving outcomes will be essential for guiding clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the utility of GCS and vital sign monitoring in predicting elevated ICP in TBI patients while recognizing the limitations of relying on late-stage indicators such as Cushing’s reflex. By integrating these tools with early intervention strategies and exploring advanced detection methods, healthcare providers can optimize outcomes and resource use for patients at risk of elevated ICP.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the design, methodology, data collection, and analysis of this study. Specifically, [Author A] contributed to the research concept and data analysis, [Author B] was involved in patient recruitment and data collection, and [Author C] took the lead in writing and revising the manuscript. All authors were actively engaged in critical discussions and interpretation of the findings. The final manuscript was thoroughly reviewed and unanimously approved by all authors.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Institute of Rangsit University, grant number 35/2566. The APC (Article Processing Charge) was also funded by the Research Institute of Rangsit University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rangsit University (protocol code 35/2566 and date of approval: [4 April 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has also been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper, where applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the reported results are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for observational studies.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI or AI-assisted tools were not used in drafting any aspect of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their sincere gratitude to Samut Prakan Hospital and Rangsit University for their invaluable support, including the provision of a research grant that made this study possible. Special thanks are extended to the medical and nursing staff at Samut Prakan Hospital, whose cooperation and dedication were crucial in conducting this research. We also acknowledge the patients and their families for their participation and trust during the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest related to this study. All aspects of the research, from study design to data interpretation, were conducted with full transparency and without any influence from external parties.

References

- World Health Organization. Road traffic injuries [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- McNamara, R.; Meka, S.; Anstey, J.; Fatovich, D.; Haseler, L.; Jeffcote, T.; et al. Development of traumatic brain injury-associated intracranial hypertension prediction algorithms: A narrative review. J. Neurotrauma 2023, 40, 416–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Royal College of Neurological Surgeons of Thailand. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Traumatic Brain Injury; Prosperous Plus: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Samutprakan Hospital. Annual Statistical Report 2020–2022 [Internet]. 2022. Available online: http://www.spko.moph.go.th/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/1 (accessed on 11 September 2024). (In Thai).

- Jiamsakul, S.; Prachusilpa, G. A study of nursing outcomes quality indicators for patients with neurosurgery. J. Royal Thai Army Nurses 2017, 18, 147–154. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Khoshfetrat, M.; Yaghoubi, M.A.; Hosseini, B.M.; Farahmandrad, R. The ability of GCS, FOUR, and APACHE II in predicting the outcome of patients with traumatic brain injury: A comparative study. Biomed Res. Ther. 2020, 7, 3614–3621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salottolo, K.; Carrick, M.; Johnson, J.; Gamber, M.; Bar, O.D. A retrospective cohort study of the utility of the modified early warning score for interfacility transfer of patients with traumatic injury. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uakarn, C.; Chaokromthong, K.; Sintao, N. Sample size estimation using Yamane and Cochran, Krejcie and Morgan, and Green formulas and Cohen statistical power analysis by G*Power and comparisons. APHEIT Int. J. 2021, 10, 76–87. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Wongtimarat, K.; Chaengsuthiworawat, P.; Durongbhandhu, T.; Chawarntunpipat, V. Comparison between full outline of unresponsiveness and Glasgow Coma Scale for predicting survival in hemorrhagic stroke patients. Thai J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 3, 2–13. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Songwathana, P.; Kitrungrote, L.; Anumas, N.; Nimitpan, P. Predictive factors for health-related quality of life among Thai traumatic brain injury patients. J. Behav. Sci. 2018, 131, 82–90. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Brain Trauma Foundation. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://braintrauma.org/coma/guidelines/guidelines-for-the-management-of-severe-tbi-4th-ed (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Najafia, Z.; Zakerib, H.; Mirhaghic, A. The accuracy of acuity scoring tools to predict 24-h mortality in traumatic brain injury patients: A guide to triage criteria. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2018, 26, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.K.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, B.K.; Cho, Y.S.; Ryu, S.J.; Jung, Y.H. Performance of modified early warning score (MEWS) for predicting in-hospital mortality in traumatic brain injury patients. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 10, 1915–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.D.; Lopez, B.P.; Miquel, C.M.; Vinuela, A.; Conty, J.L.M.; Izquierdo, R.L. Comparison of nine early warning scores for identification of short-term mortality in acute neurological disease in emergency department. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 53, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, S.D.; Chao, E.; Chen, S.J.; Hueng, D.Y.; Lan, H.Y.; Chiang, H.H. Machine learning algorithms to predict in-hospital mortality in patients with traumatic brain injury. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deen, H.G. Head trauma. In ClinicalGate [Internet]. 2020. Available online: https://clinicalgate.com/head-trauma-2/ (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Hutauruk, M.M.D.; Dharmawati, I.; Setiawan, P. Profile of airway patency, respiratory rate, PaCO2, and PaO2 in severe traumatic brain injury patients (GCS <9) in emergency room Dr. Soetomo Hospital Surabaya. Indones. J. Anesthesiol. Reanim. 2020, 1, 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D.; Chen, T.; Yuan, X. Predictive value of the trauma rating index in age, Glasgow coma scale, respiratory rate, and systolic blood pressure score (TRIAGES) for the short-term mortality of older patients with isolated traumatic brain injury: A retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2024, 71, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asmar, S.; Chehab, M.; Bible, L.; Khurrum, M.; Castanon, L.; Ditillo, M.; Joseph, B. The emergency department systolic blood pressure relationship after traumatic brain injury. J. Surg. Res. 2021, 257, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, G.F.; DePadilla, L.; Xu, L. Costs of nonfatal traumatic brain injury in the United States, 2016. Med. Care 2021, 59, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Dijck, J.T.J.M.; Mostert, C.Q.B.; Greeven, A.P.A.; Kompanje, E.J.O.; Peul, W.C.; DeRuiter, G.C.W.; Polinder, S. Functional outcome, in-hospital healthcare consumption and in-hospital costs for hospitalised traumatic brain injury patients. Acta Neurochir. (Wien) 2020, 162, 1607–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suwanpitak, W.; Vipavakarn, S.; Prakeetavatin, B. Development of clinical nursing practice guideline for patients with mild traumatic brain injury in Krabi Hospital. South Coll. Netw. J. Nurs. Public Health 2017, 4, 140–156. (In Thai) [Google Scholar]

- Gotts, J.E.; Matthay, M.A. Sepsis: Pathophysiology and clinical management. BMJ 2016, 353, i1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; He, Z.; Li, Z.; Gong, R.; Hui, J.; Weng, W.; Wu, X.; Yang, C.; Jiang, J.; Xie, L.; Feng, J. Traumatic brain injury in elderly population: A global systematic review and meta-analysis of in-hospital mortality and risk factors among 2.22 million individuals. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 99, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanem-Zoubi, N.O.; Vardi, M.; Laor, A.; Weber, G.; Bitterman, H. Assessment of disease-severity scoring systems for patients with sepsis in general internal medicine departments. Crit. Care 2018, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).