Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples Preparation

2.2. Characterization Techniques

3. Results and Discussions

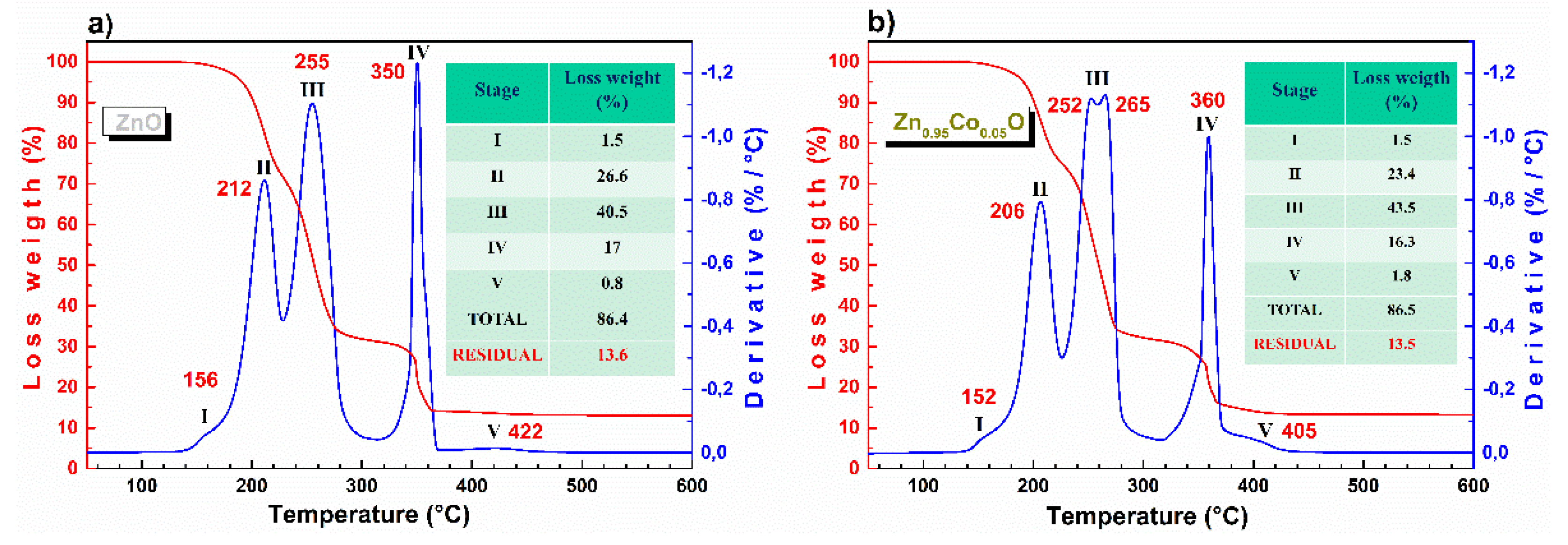

3.1. Thermogravimetric Analysis

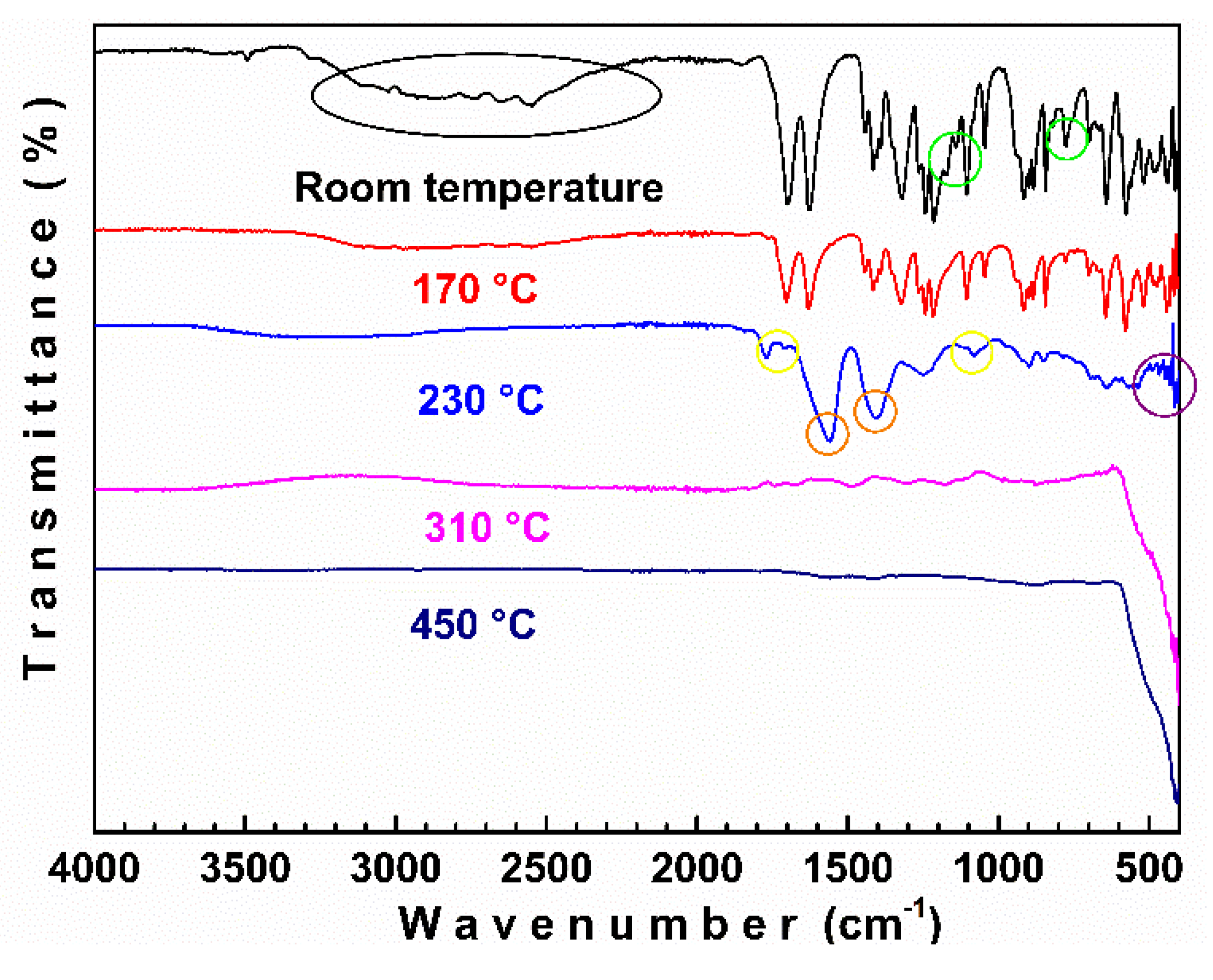

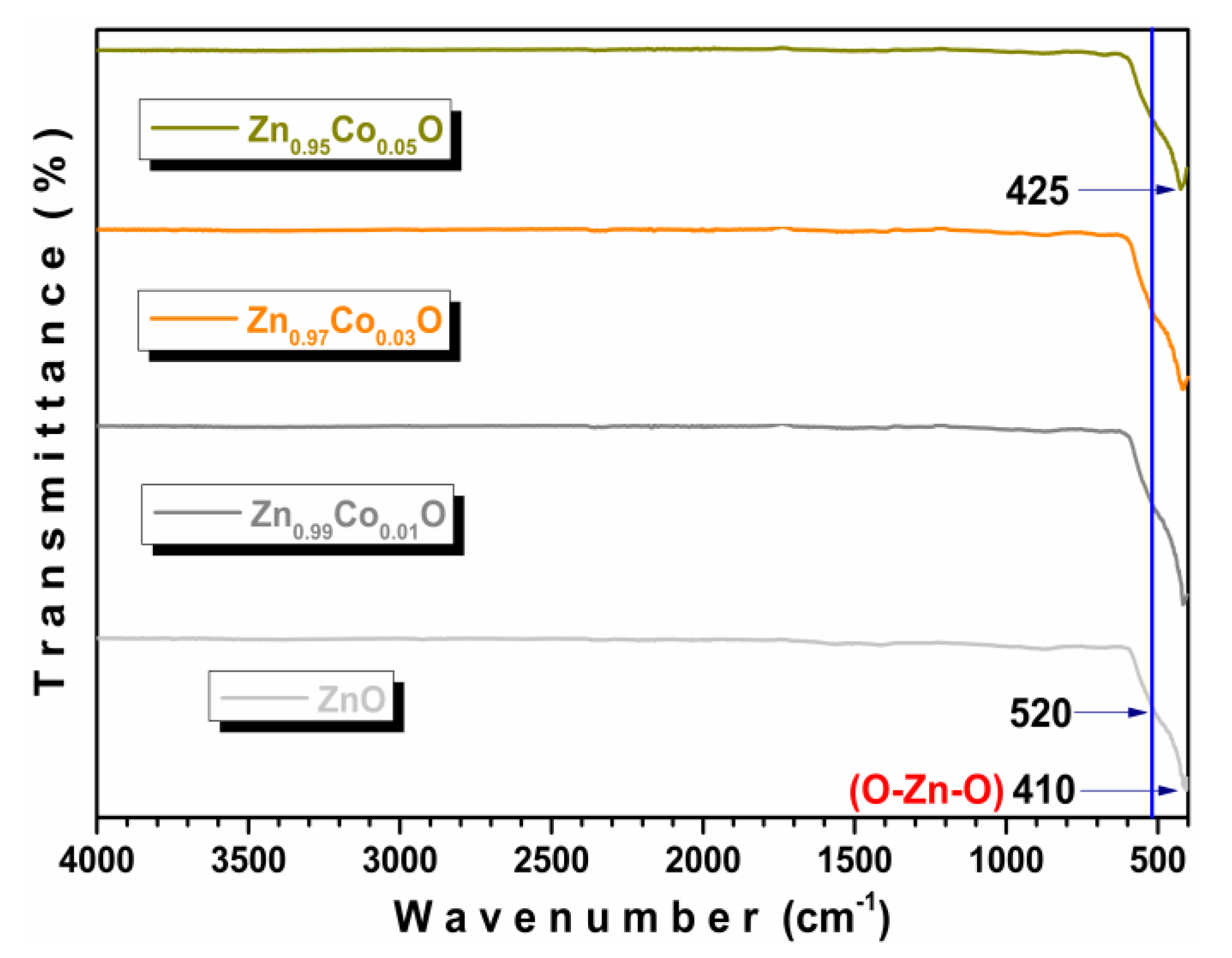

3.2. FTIR-ATR

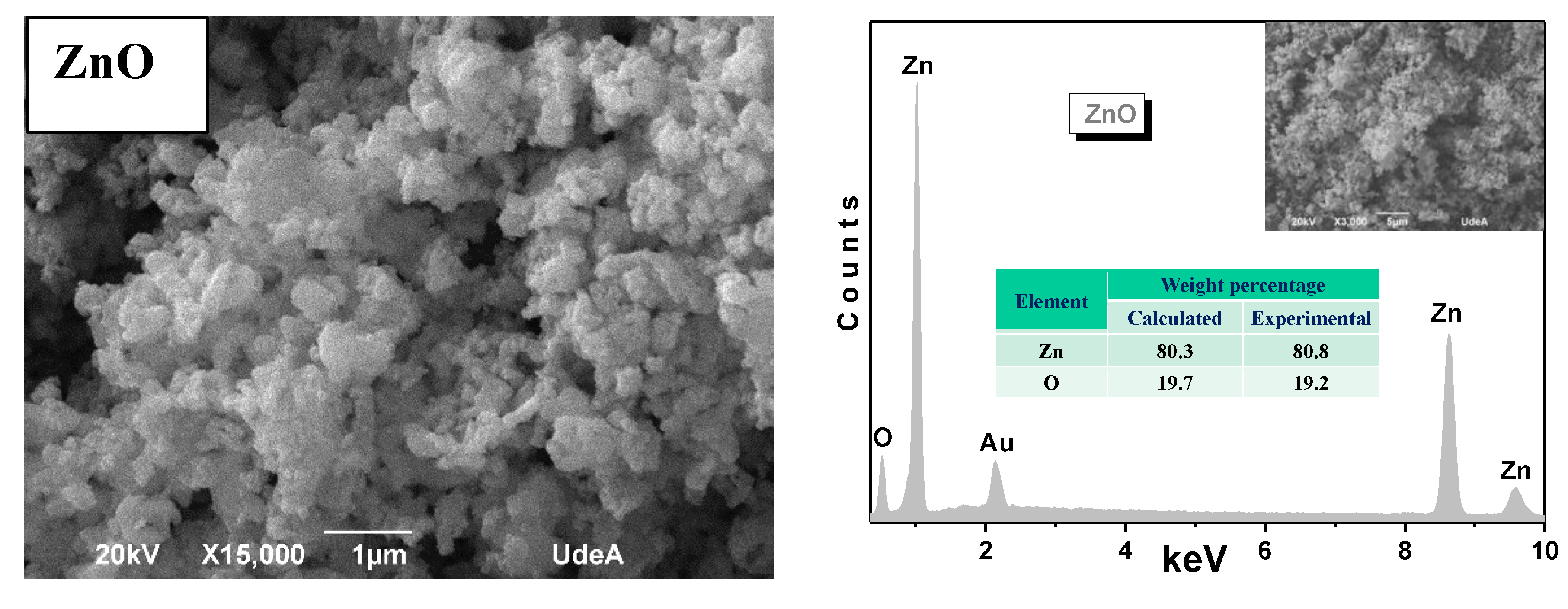

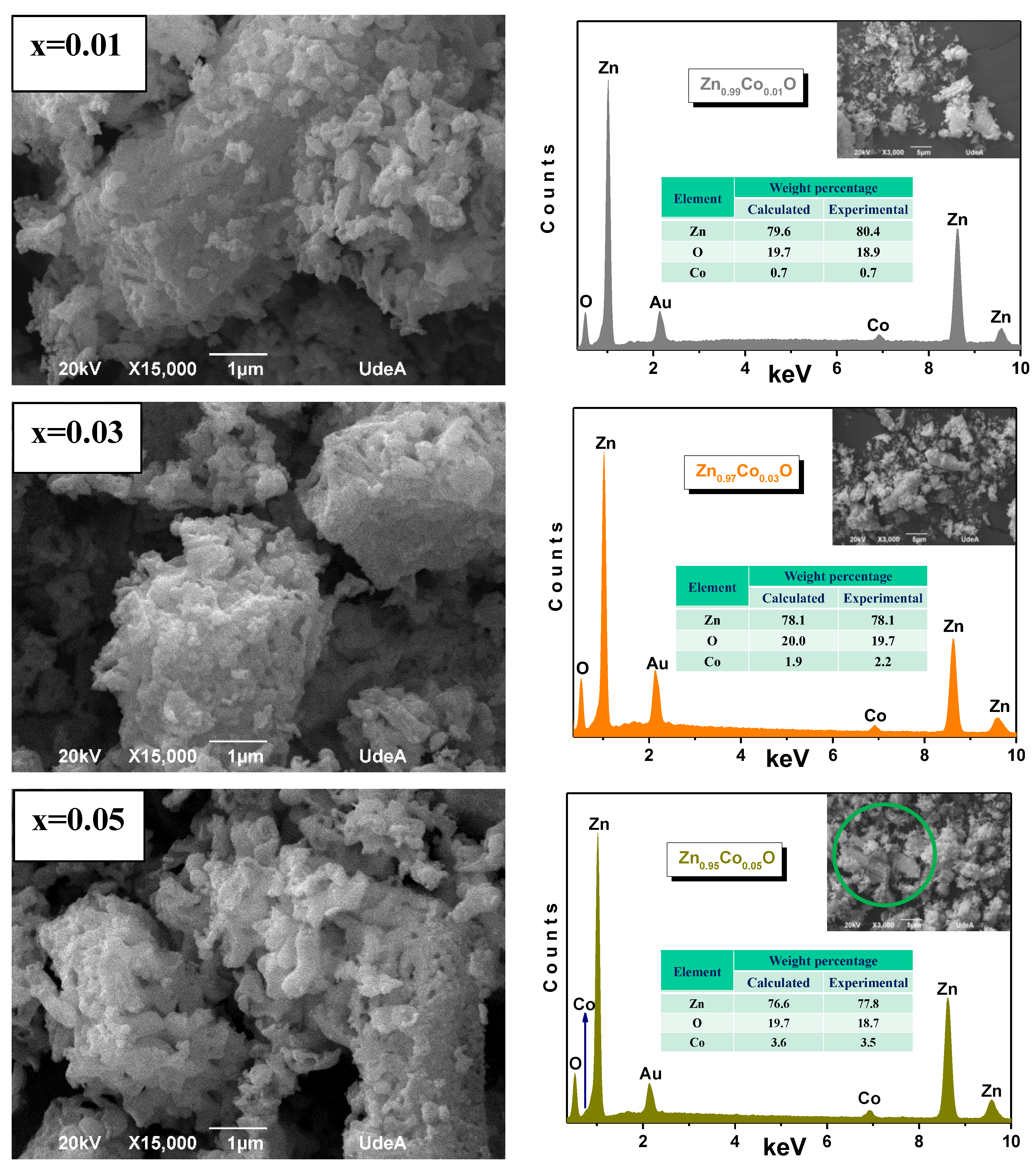

3.3. SEM Micrographs

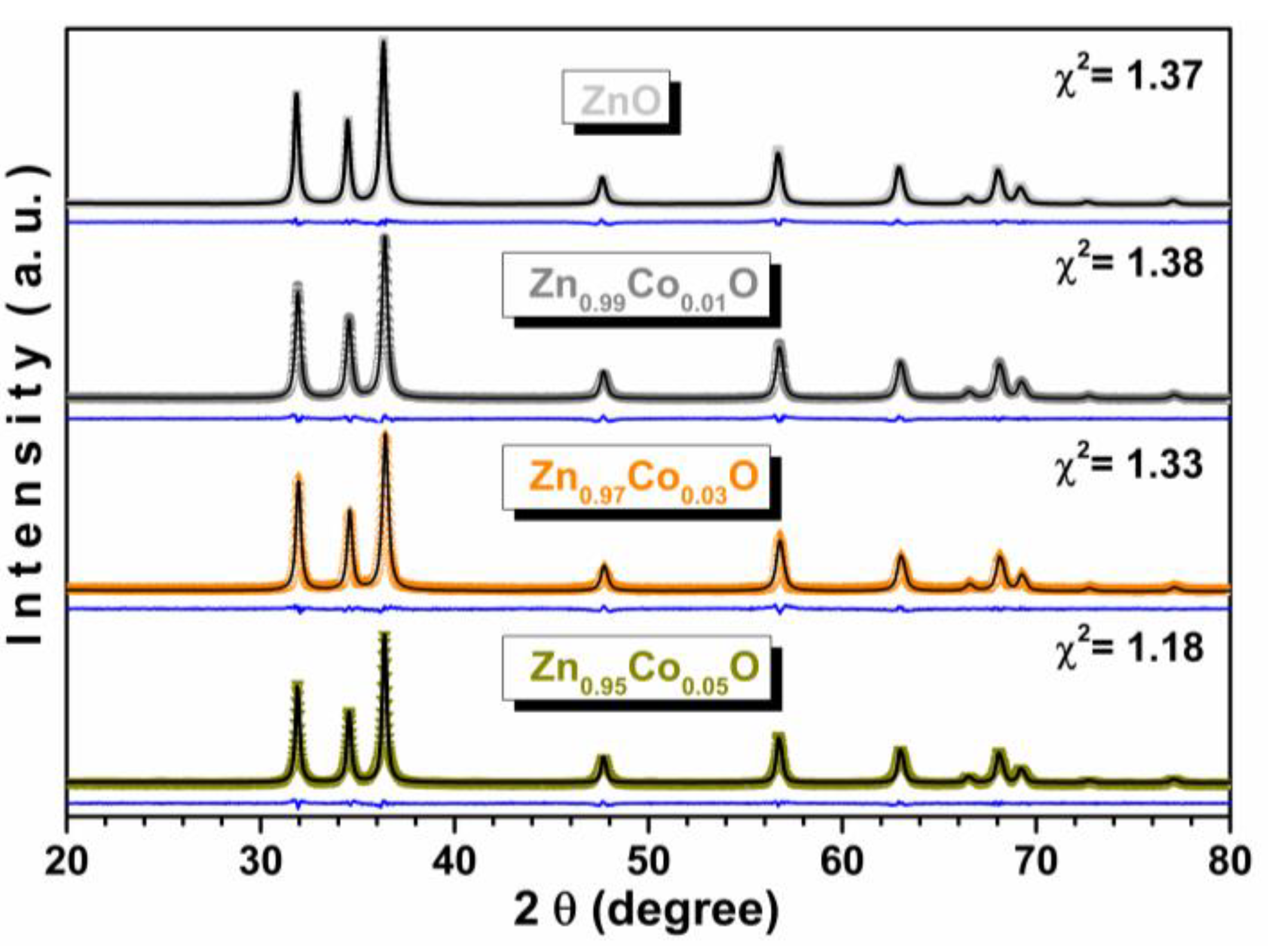

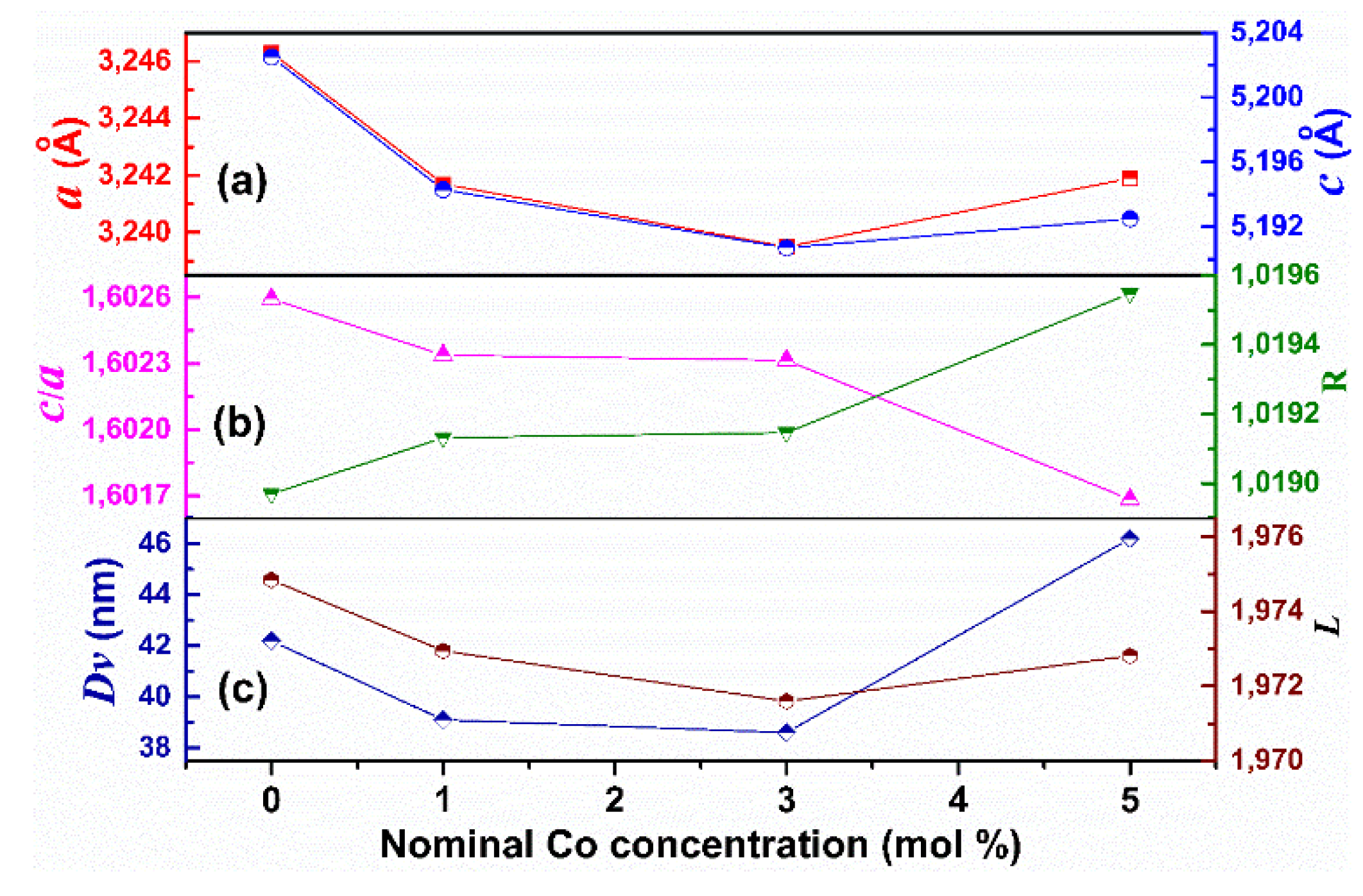

3.4. XRD

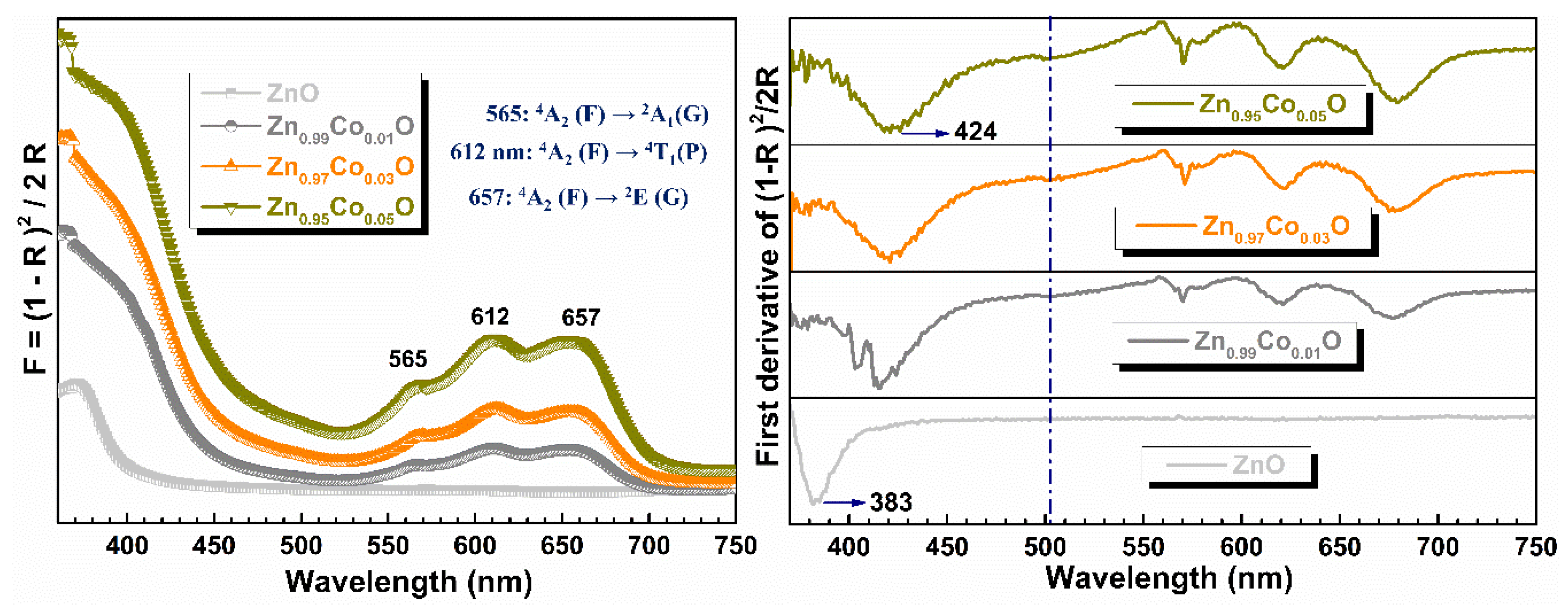

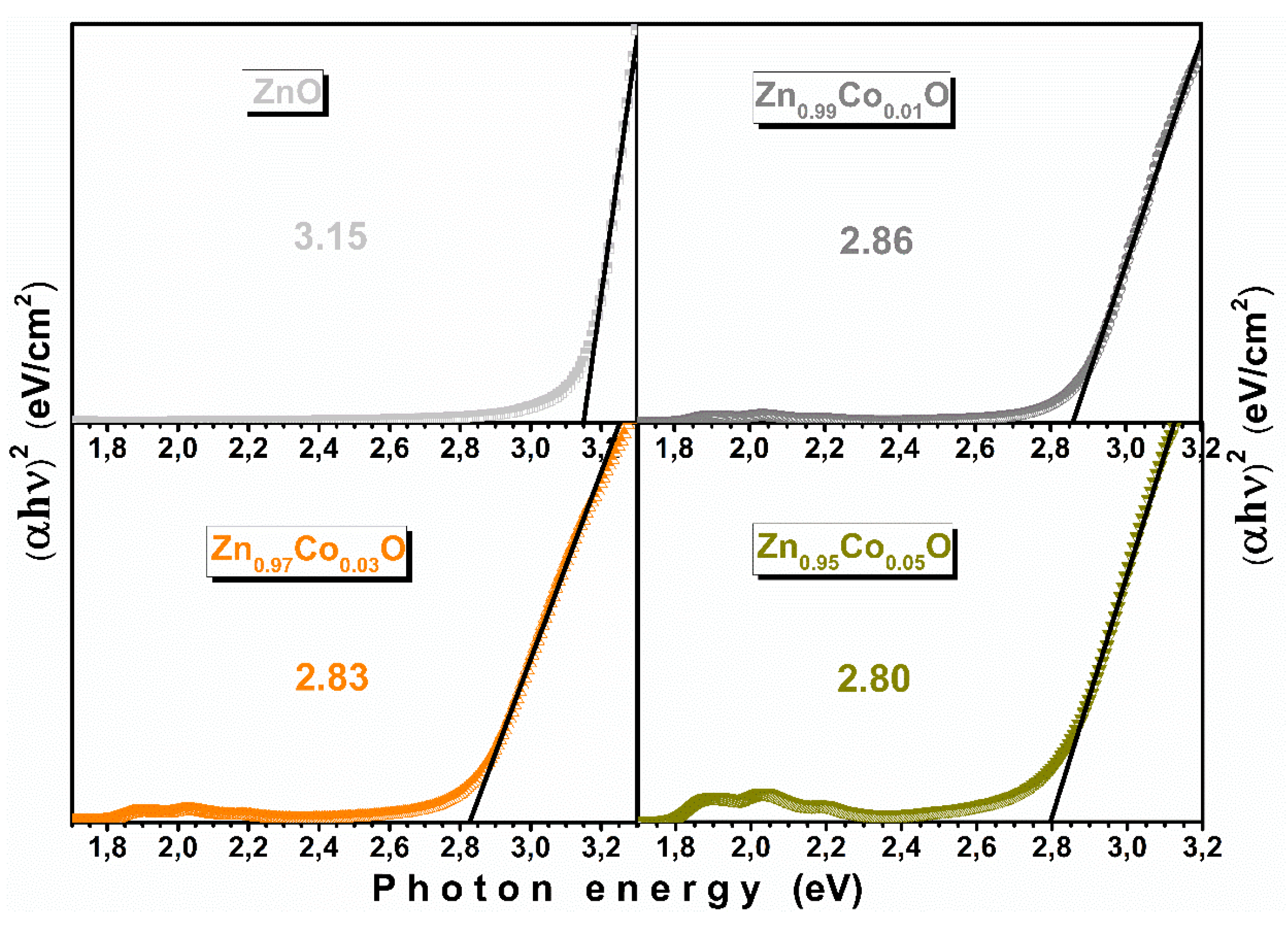

3.5. Optical Properties

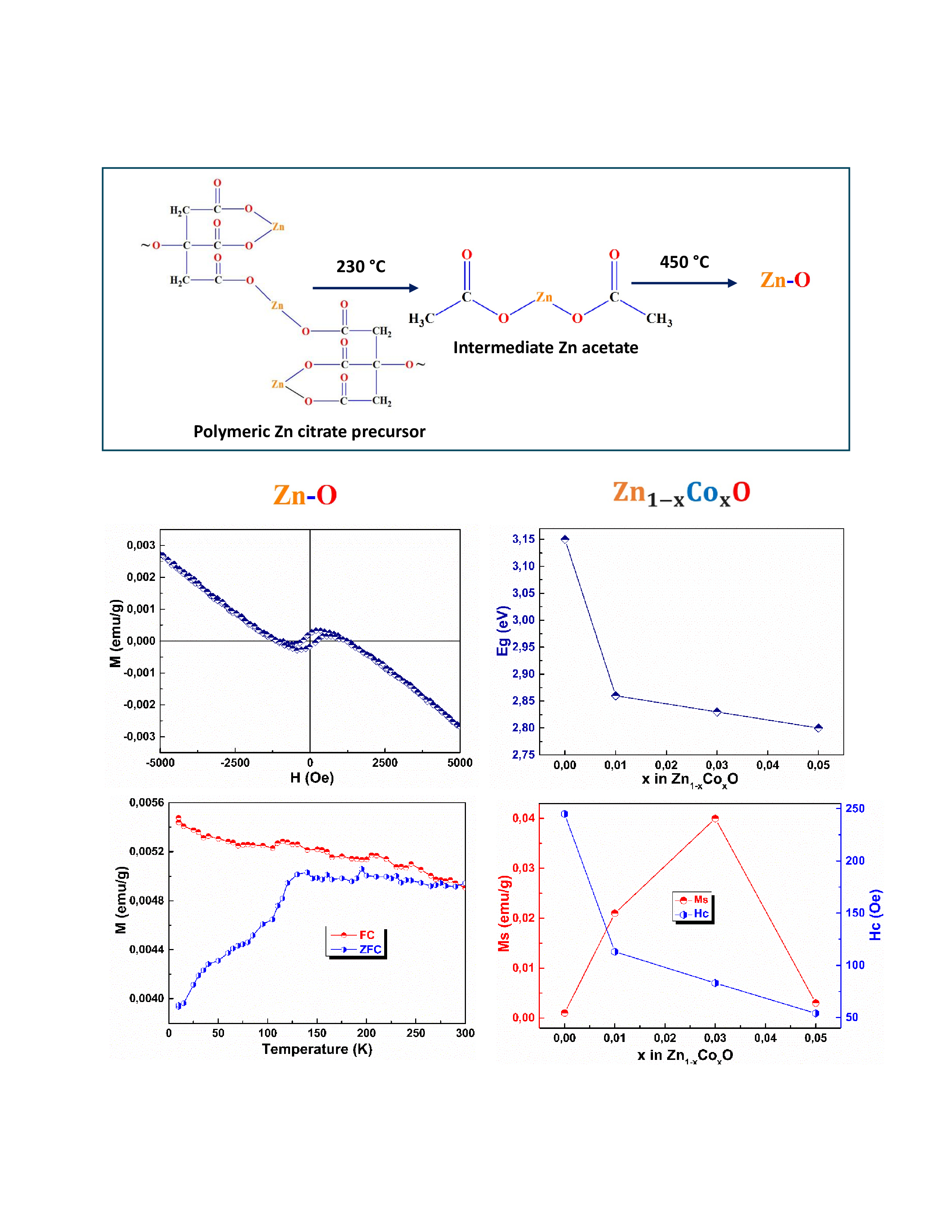

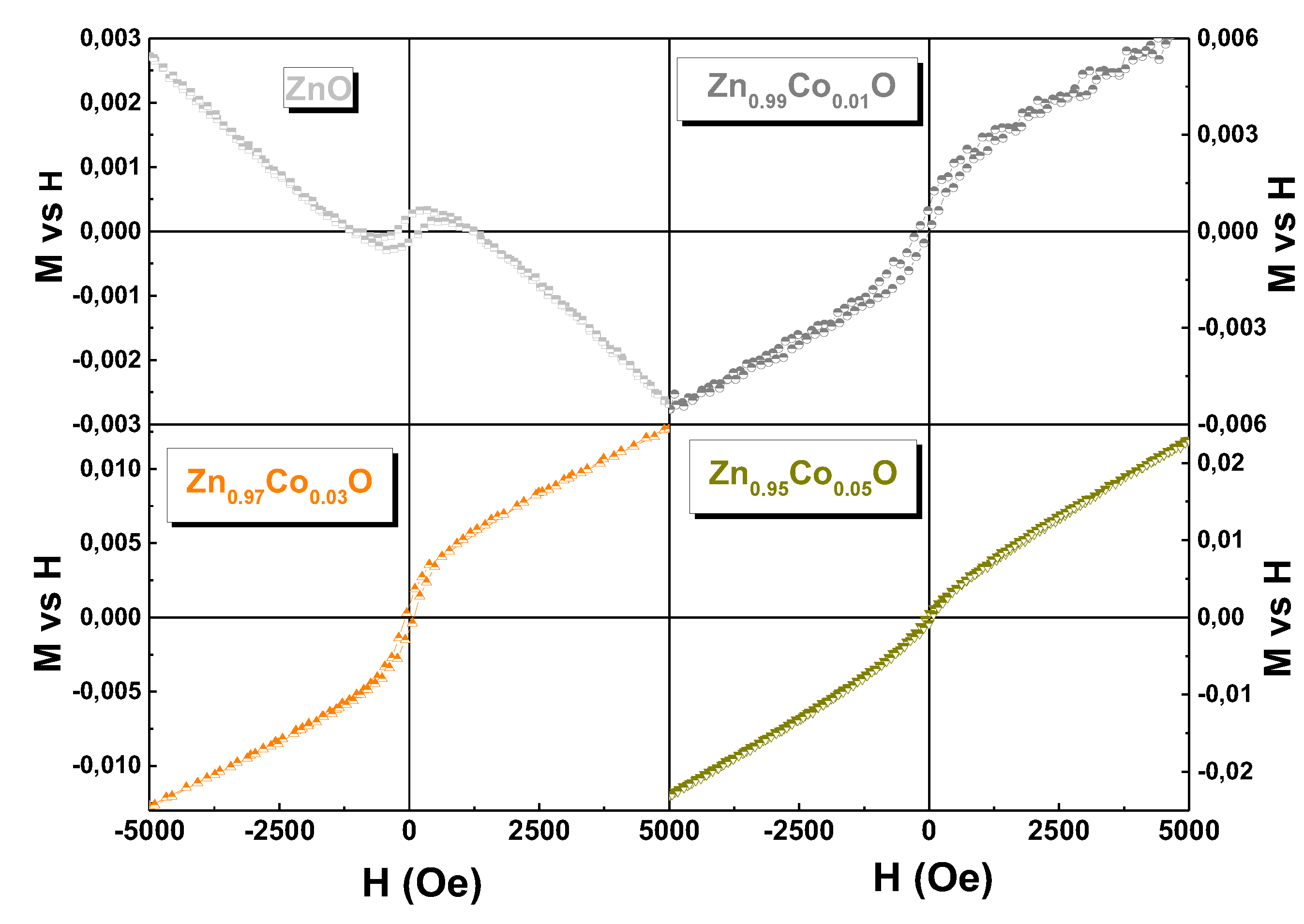

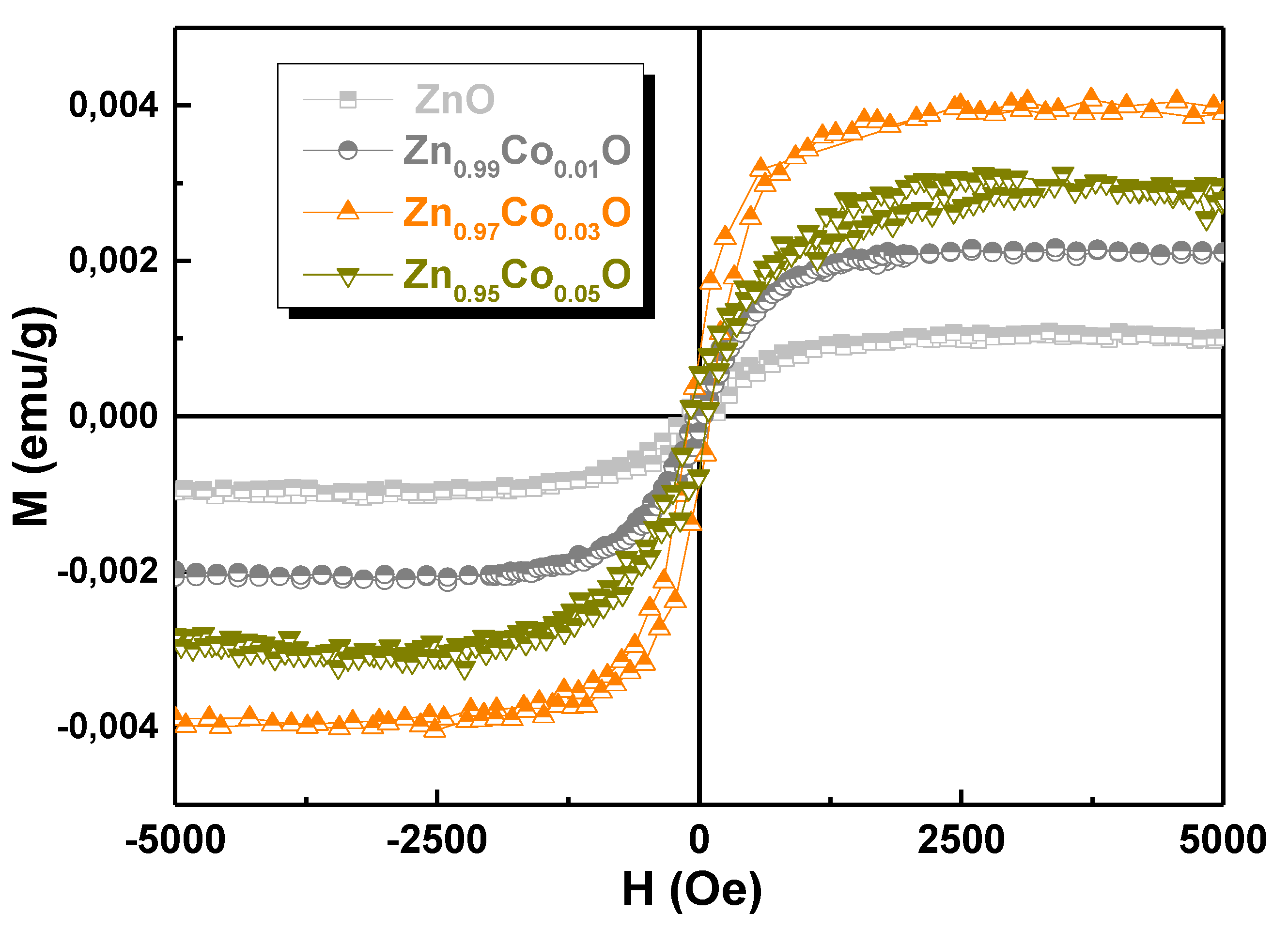

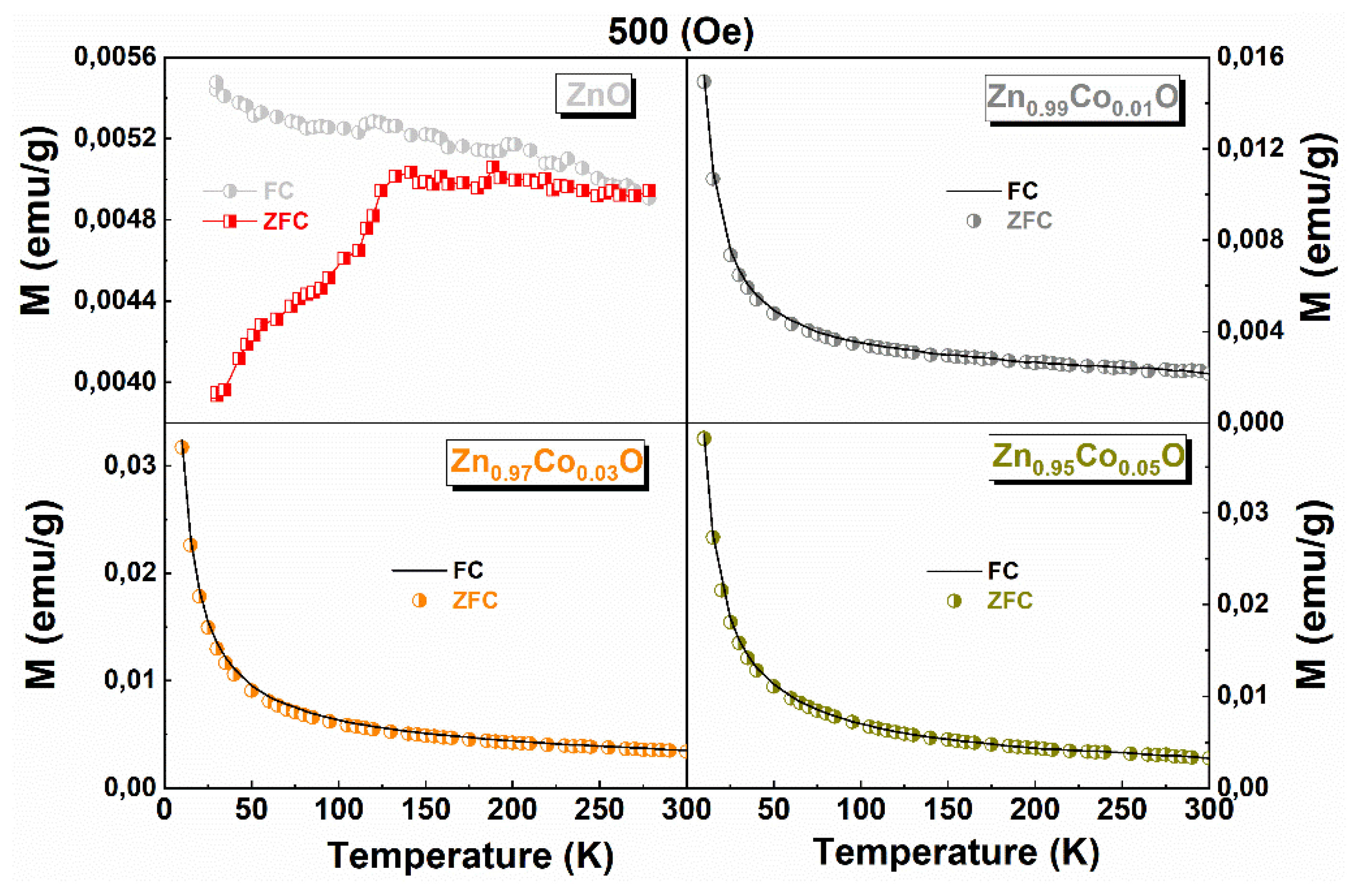

3.6. Magnetic Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hossain, N.; Afroz, M.F.; Alam, M.; Shuvo, M.A.I.; Mohiuddin, M., Hossen, M.N.; Iqbal, A.; Rahman, M.A.; Rahman, M.M. Advances and significances of nanoparticles in semiconductor applications – A review. Results Eng. 2023, 19, 101347. [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.A.; Ansari, M.O.; Alomari, M.; Alshahrani, T.; Rather, H.A.; Ahmad, R.; Ansari, S.A. ZnO nanostructures – Future frontiers in photocatalysis, solar cells, sensing, supercapacitor, fingerprint technologies, toxicity, and clinical diagnostics. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 515, 215942. [CrossRef]

- Noman, M.T.; Amor, N.; Petru, M. Synthesis and applications of ZnO nanostructures (ZONSs): a review. Crit. Rev. Solid State Mater. Sci.2022, 47(2), 99–141. [CrossRef]

- Raha, S.; Ahmaruzzaman, M. ZnO nanostructured materials and their potential applications: progress, challenges and perspectives. Nanoscale Adv. 2022, 4(8), 1868–1925. [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Saha, A.; Shukla, A.; Anand, A.; Kar, K.K.; Tiwari, A. A critical review on zinc oxide nanoparticles: Synthesis, properties and biomedical applications. Intell. Pharm. 2024, 3(1), 53–70. [CrossRef]

- Kalita, H.; Bhushan, M.; Singh, L.R. A comprehensive review on theoretical concepts, types and applications of magnetic semiconductors. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2023, 288, 116201. [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, A.; Rehman, M.A.; Khan, M.Y.; Abro, M.I.; Ullah, R.; Naqvi, S.R.; Laref, A. Robust ferromagnetism in rare-earth and transition metal co-doped ZnO nanoparticles for spintronics applications. Mater. Lett. 2022, 310, 131479. [CrossRef]

- Tun Naziba, A.; Paiman, S.; Rusop, M.; Sahdan, M.Z.; Dimyati, K. Structural, optical, and magnetic properties of Co-doped ZnO nanorods: Advancements in room temperature ferromagnetic behavior for spintronic applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2024, 593, 171836. [CrossRef]

- Habanjar, K.; Chakraborty, P.; Sharma, P.; Sharma, T.K.; Kumar, R. Magneto-optical effect of (Sm, Co) co-doping in ZnO semiconductor. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 2020, 598(July), 412444. [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, I.; Ahmad, M.; Nazir, S.; Ghaffar, A.; Arshad, S.; Khan, F.; Abbas, G.; Ali, M. Diluted magnetic semiconductor properties in TM doped ZnO nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2022, 12(21), 13456–13463. [CrossRef]

- Zelekew, O.A.; Almomani, F.; Haddad, R.; Ayele, D.W. Green synthesis of Co-doped ZnO via the accumulation of cobalt ion onto Eichhornia crassipes plant tissue and the photocatalytic degradation efficiency under visible light. Mater. Res. Express 2021, 8(2), 025010. [CrossRef]

- Ogwuegbu, M.C.; Olatunde, O.C.; Pfukwa, T.M.; Mthiyane, D.M.N.; Fawole, O.A.; Onwudiwe, D.C. Green synthesis, characterization and antimicrobial activity of ZnO and Co-doped ZnO nanoparticles obtained using aqueous extracts of Platycladus orientalis leaves. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5(1). [CrossRef]

- Arruda, L.B.; Leite, D.M.G.; Orlandi, M.O.; Ortiz, W.A.; Lisboa-Filho, P.N. Sonochemical synthesis and magnetism in co-doped ZnO nanoparticles. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2013, 26(7), 2515–2519. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, K.; Kumar, M.; Chauhan, S.; Raman, R.S. Microwave-assisted sol-gel synthesis of Li-Co doped zinc oxide nanoparticles: Investigating the effects of codoping on structural, optical, and magnetic properties for spintronic applications. J. Cryst. Growth 2025, 652, 128053. [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Cai, C.; Zhou, S.; Liu, W. Structure, photoluminescence, and magnetic properties of Co-doped ZnO nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron.2018, 29(15), 12917–12926. [CrossRef]

- Elilarassi, R.; Chandrasekaran, G. Influence of Co-doping on the structural, optical and magnetic properties of ZnO nanoparticles synthesized using auto-combustion method. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2013, 24(1), 96–105. [CrossRef]

- Salkar, K.Y.; Tangsali, R.B.; Gad, R.S.; Jeyakanthan, M.; Subramanian, U. Preparation characterization and magnetic properties of Zn(1-x)CoxO nanoparticle dilute magnetic semiconductors. Superlattices Microstruct. 2019, 126, 158–173. [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, J.J.; Barrero, C.A.; Punnoose, A. Identifying the sources of ferromagnetism in sol-gel synthesized Zn(1-x)CoxO (0≤x≤0.10) nanoparticles. J. Solid State Chem. 2016, 240, 30–42. [CrossRef]

- Badhusha, M.S.M.; Kavitha, B.; Rajarajan, M.; Tharmaraj, P.; Suganthi, A. Synthesis of Co and Cu codoped ZnO nanoparticles by citrate gel combustion method: Photocatalytic and antimicrobial activity. J. Water Environ. Nanotechnol. 2022, 7(2), 143–154. [CrossRef]

- Bhagwat, M.; Shah, P.; Ramaswamy, V. Synthesis of nanocrystalline SnO2 powder by amorphous citrate route. Mater. Lett. 2003, 57(9–10), 1604–1611. [CrossRef]

- Pimpang, P.; Sumang, R.; Choopun, S. Effect of Concentration of Citric Acid on Size and Optical Properties of Fluorescence Graphene Quantum Dots Prepared by Tuning Carbonization Degree. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2018, 45(5), 2005–2014. [CrossRef]

- Farbun, I.A.; Romanova, I.V.; Terikovskaya, T.E.; Dzanashvili, D.I.; Joo, S.W.; Kirillov, S.A. Complex Formation in the Course of Synthesis of Zinc Oxide from Citrate Solutions. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2007, 80(11), 1798–1803. [CrossRef]

- Poorna, K.S.V.; Patra, D.; Qureshi, A.A.; Gopalan, B.J. Metal citrate nanoparticles: a robust water-soluble plant micronutrient source. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 20370. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, D.; Aziz, D.; Aziz, S. Zinc metal complexes synthesized by a green method as a new approach to alter the structural and optical characteristics of PVA: new field for polymer composite fabrication with controlled optical band gap. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 26362. [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Anusuya, S.; Anbazhagan, V. Anticancer, anti-diabetic, antimicrobial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles: A comparative analysis. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1263, 133139. [CrossRef]

- Dillip, G.R.; Banerjee, A.N.; Anitha, V.C.; Prasad Raju, B.D.; Joo, S.W.; Min, B.K. Oxygen Vacancy-Induced Structural, Optical, and Enhanced Supercapacitive Performance of Zinc Oxide Anchored Graphitic Carbon Nanofiber Hybrid Electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8(7), 5025–5039. [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, J.J.; Barrero, C.A.; Punnoose, A. Relationship between ferromagnetism and formation of complex carbon bonds in carbon doped ZnO powders. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21(17), 8808–8819. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Pal, U.; Serrano, J.G.; Ucer, K.B.; Williams, R.T. Photoluminescence and FTIR study of ZnO nanoparticles: The impurity and defect perspective. Phys. Status Solidi C 2006, 3(10), 3577–3581. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.P.; Li, W.; Wu, W., Yu, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z. Adsorption behaviors of gas molecules on the surface of ZnO nanocrystals under UV irradiation. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 2019, 62(12), 2226–2235. [CrossRef]

- Sahu, S.; Samanta, P.K. Peak Profile Analysis of X-ray Diffraction Pattern of Zinc Oxide Nanostructure. J. Nano Electron. Phys. 2021, 13(5), 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-sotelo, A.; Avila-meza, M.; Melendez-lira, M.A.; Fernandez-muñoz, J.L.; Zelaya-angel, O. Modification of the crystalline structure of ZnO nanoparticles embedded within a SiO2 matrix due to thermal stress effects. Mater. Res. 2019, 22(4). [CrossRef]

- Musolino, M.G.; Busacca, C.; Mauriello, F.; Pietropaolo, R. Aliphatic carbonyl reduction promoted by palladium catalysts under mild conditions. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2010, 379(1–2), 77–86. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, C.; Zhu, C.; Ouyang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y. Synthesis and low-temperature sensing property of the porous ZnCo2O4 nanosheets. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30(6), 5357–5365. [CrossRef]

- Hays, J.; Ramsier, R.D.; Chase, L.L.; Bowman, M.K.; Muntele, C.; Muntele, I..; Nastasi, M. Effect of Co doping on the structural, optical and magnetic properties of ZnO nanoparticles. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2007, 19(26), 266203 . [CrossRef]

- Shannon Radii. (2020) Database of Ionic Radii. [Online] Available from: http://abulafia.mt.ic.ac.uk/shannon/ptable.php.

- Shi, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y. Structural, optical and magnetic properties of Co-doped ZnO nanorods prepared by hydrothermal method. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 576, 59–65. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, J.; Liu, Y.; Hao, W.; Li, B. Controllable synthesis and magnetic investigation of ZnO: Co nanowires and nanotubes. Mater. Lett. 2012, 87, 101–104. [CrossRef]

- Beltrán, J.J.; Barrero, C.A.; Punnoose, A. Understanding the role of iron in the magnetism of Fe doped ZnO nanoparticles. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 15284–15296. [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, S.; Güner, S.; Koseoglu, Y.; M.-n. J.; Adamu, B. Simple method for the determination of band gap of a nanopowdered sample using Kubelka Munk theory. J. Niger. Assoc. Math. Phys. 2016, 35, 241–246.

- Repp, S.; Erdem, E. Controlling the exciton energy of zinc oxide (ZnO) quantum dots by changing the confinement conditions. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2016, 152, 637–644. [CrossRef]

- Motaung, D.E.; Ngoepe, P.N.; Nakonde, H.; Singh, M.; Swart, H.C. Shape-selective dependence of room temperature ferromagnetism induced by hierarchical ZnO nanostructures. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 8981–8995. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xu, C.; Dai, J.; Hu, J.; Li, F.; Zhang, S. Size dependence of defect-induced room temperature ferromagnetism in undoped ZnO nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 8813–8818. [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.B.; Rao, G.H.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.C. Ferromagnetism of lightly Co-doped ZnO nanoparticles. Solid State Commun. 2008, (11–12), 525–528. [CrossRef]

- Moura, K.O.; Lima, R.J.S.; Jesus, C.B.R.; Duque, J.G.S.; Meneses, C.T. Fe-doped NiO nanoparticles: Synthesis, characterization, and magnetic properties. J. Magn. Magn. Mater 2012, 58(3), 167–170. [CrossRef]

- Punnoose, A.; Philip, J.; Rice, J.T.; Kim, B.I.; Rabiei, S.; Healy, K.; Seebauer, E.G. Development of high-temperature ferromagnetism in SnO₂ and paramagnetism in SnO by Fe doping. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 054402. [CrossRef]

| x in Zn1-xCoxO | Mo (emu/g) | C (emu K/g Oe) | θ (K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.01 | 0.94 | 0.15 | 1.26 |

| 0.03 | 1.29 | 0.33 | 1.41 |

| 0.05 | 1.09 | 0.45 | 2.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).