1. Introduction

Tungsten carbide–cobalt (WC-Co) is an engineered material widely used in wear-resistant tools due to the composite’s exceptional hardness, strength, and thermal stability. WC-Co consists of hard tungsten (WC) grains held together by a softer, ductile, cobalt (Co) binder phase. The combination of toughness and wear resistance makes the material ideal for cutting, drilling, and forging operations. However, these same properties make WC-Co extremely difficult to machine.

During grinding, the Co binder undergoes plastic deformation, extrudes from the matrix, and adheres to the abrasive surface. This leads to frequent wheel dress interruptions and inconsistent cutting behavior. Even when wheel loading is managed, WC-Co remains challenging to grind. At high material removal rates (MRR), the composite often cracks due to the difference in mechanical behavior between the WC and Co phases and the high energy required to shear through the hard matrix. To limit surface and subsurface damage WC-Co parts are ground slowly in multiple low-depth passes.

In grinding brittle fracture is key to removing large amounts of material quickly. The high hardness (up to 85 HRC) and quasi ductility of WC-Co requires high energy input for modest fracture. For example, WC-Co’s specific grinding energy ranges anywhere from 50 to 200 J/mm³ [

1]. To put this amount of energy in perspective, it’s significantly higher than that needed for even difficult to grind hardened tools steels like ANSI 4140 (25–40 J/mm³) or D3 (40 to 80 J/mm³).

At the core of the WC-Co grindability problem is how the hard WC grains and softer Co binder interact. During grinding, the cobalt phase is compressed from the intergranular regions of the WC lattice rather than causing fracture of the WC grains. This leads to abrasive wheel loading and reduced efficiency [

1]. Many studies have sought to overcome MRR inefficiencies by promoting brittle fracture over ductile flow [

2]. However, even under conditions optimized for brittle fracture, MRRs grinding WC-Co typically remain below 10 mm³/min [

3].

LAM has emerged as a promising technique to enhance WC-Co machinability. The Co binder embrittles in this process thereby reducing energy required for grinding [

4]. Karpuschewski et al. conducted foundational LAM research of WC-Co using a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. Their work showed laser parameters such as pulse repetition rate, beam intensity, and scanning speed significantly influenced surface roughness, layer removal rate, and thermal damage. They also found that grain size played a critical role in laser-material interaction. Specifically, finer grains were found to yield smoother surfaces and more uniform ablation [

4].

Within the LAM field, advances in nanosecond pulsed laser ablation (PLA) showed promise. Unfortunately, in the case of WC-Co, thermal damage problems such as recast layers and spatter redeposition were common [

5]. To address these issues researchers turned to ultrashort pulse lasers (USPLs) on the order of picoseconds and femtoseconds. However, You and Fang found very large amounts of energy input (e.g., 300 W) were needed for modest (e.g., 45 mm³/min) material removal rates [

6]. Subsequent researchers such as Lickschat et al. were able to produce some MRR improvements by further shortening pulse durations [

7].

Hybrid techniques emerged as possible solutions to WC-Co material removal challenges. Laser-ultrasonically assisted turning (LUAT) and laser-assisted diamond turning (LADT) both combined thermal crack softening from laser heating with turning. For example, in LUAT, the combination of ultrasonic vibration and laser heating significantly reduced cutting forces and tool wear [

8]. LADT, on the other hand, enabled mirror-finish surfaces on binderless WC achieving roughness as low as 0.92 nm [

9]. Additional studies with finite element modeling further improved LADT tool life and machining precision [

10].

To address tool wear problems inherent to both LUAT and LDT, researchers studied noncontact methods of WC-Co cutting such as electrochemical and electrical discharge machining (e.g., ECM and EDM respectively). Singh et al. focused their MRR efforts on electrolyte optimization [

11] while Schubert et al. explored current densities [

12]. Indeed, ECM and EDM solve the tool wear problem of machining WC-Co, but the issues of microcracking and recast layers persist [

13]. Direct Laser Deposition (DLD) attempts to turn the recasting issue encountered in subtractive manufacturing into an advantage. Recasting is a core feature in additive manufacturing. DLD researchers have focused their efforts on optimum laser parameters to control both surface roughness and crack formation during deposition [

14].

A common thread among all LAM methods (i.e., LUAT, LDT, EDM, ECM, USPL, PLA, LAM, DLM) is a reliance upon high levels of energy which produce enough heat to induce cracks. Hazzan et al. went so far as to develop a laser induced crack classification system [

15]. This research sought to advance LAM by answering two questions:

Was it possible using pulsed irradiation to melt Co within the WC lattice without damaging the WC phase?

If so, could the HAZ be ground defect-free at MRRs significantly higher than untreated WC-Co?

2. Materials and Methods

In this proof-of-concept work focused on WC-Co with a 10% Co binder. Twelve samples (25mm wide x 25mm thick x 50 mm long) were evenly divided into three groups (e.g., Group #1, Group #2, and Group #3). Irradiation area in each group measured 242 mm2 (e.g., 6.35mm wide x 38.1mm long). Control samples were not irradiated.

Irradiation was done with a Nd:YAG solid state laser. Laser pulse (<10 ps), wavelength (1032 nm), and spot size (0.01mm) were the same in all tests. Achieving a 0.01mm spot size required a series of progressively focusing convex lenses followed by a final objective lens. Remaining laser parameters, per

Table 1, were:

During irradiation (

Figure 1) a FLIR thermal camera was used to confirm surface temperature met that required to melt cobalt (1,495°C).

After irradiation samples were analyzed using Grazing Incidence X-Ray Diffraction (GIXRD) over 2θ diffraction angles from 20° to 90°. Over this range the shallow penetration of X-rays allowed for evaluation of potential lattice changes near the material’s surface. Of particular interest was possible diffraction peak shifts and/or intensity changes indicative of structural modifications from irradiation

Irradiated and nonirradiated samples were ground with a Chevalier SMART-B818IV horizontal spindle CNC Surface & Profile Grinder. Normal and tangential grinding forces (per

Figure 2) were measured with a Kistler 9251a force transducer sensor. A Labview program was created to record force data using an NI DAQ system.

In Grind Test #1, MRR was 3.6 Q’ (mm3/min/mm). A Bakelite bonded, diamond, abrasive wheel 6.35mm wide of 100 concentration and 100 grit was used to grind samples. The wheel spun at 35 m/s and was fed across samples at 254 mm/min. Test #1 was repeated with a more aggressive, copper bonded, diamond, abrasive wheel of higher concentration (125), higher grit (600), and higher hardness (R).

In Grind Test #2, wheel speed and feed rate were the same as Test #1. The only difference was MRR. In Grind Test #2 MRR was increased nearly 75% to 6.2 Q’. The increase in MRR was achieved by increasing the depth of cut from 0.014mm in Test #1 to 0.024mm in #2. The decision to only increase depth of cut (as opposed to increasing feed rate) was based on heat. Screening tests indicated that an increase in feed rate produced localized heating. Researchers attributed this to higher friction and shorter contact time. In contrast, increasing the depth of cut distributed the energy input from grinding over a larger volume of material. Researchers, therefore, tested higher MRRs at increased depths of cut as it would help manage potential surface damage from heat generation.

In Grind Test #3, MRR was increased to 7.6 Q’. This was achieved by increasing depth of cut from 0.024mm in Test #2 to 0.030mm in #3. Wheel specification, speed and feed in Grind Test #3 were identical to Test #2.

In all tests researchers used two methods to assess surface damage. A Zygo NewView 7000 gauge measured surface roughness with a 150 µm bipolar scan. And a Keyence VHX 7000 Digital Microscope provided topography images at 500x and 1000x magnifications.

Researchers hypothesized:

Irradiation would melt the Co binder phase without altering WC.

Grinding in the HAZ would be defect free at very productive MRRs.

Griding nonirradiated WC-Co would show surface damage.

3. Results

3.1. Irradiation

Under laser conditions described in the

Materials and Methods section, surface temperate of irradiated WC-Co samples reached 1,500°C which was sufficient to melt Co. After irradiation, GIXRD measurements were taken at four penetration depths: (e.g., a (0.001 mm), b (0.030 mm), c (0.045 mm), and d (0.060 mm)) per

Figure 3. Across all deoths no shifts in peak positions were observed for either Co or WC.

However, Co intensities at 44.5° and 52° in

Figure 3 did show changes. Co intensities were lower at shallower depths (a) and (b) as compared to depth (c) and (d). WC peak intensities remained consistent across all depths. To ensure all material removal remained in the HAZ, all samples were ground no deeper 0.030 mm (e.g., depth (b) in

Figure 3).

3.2. Grinding

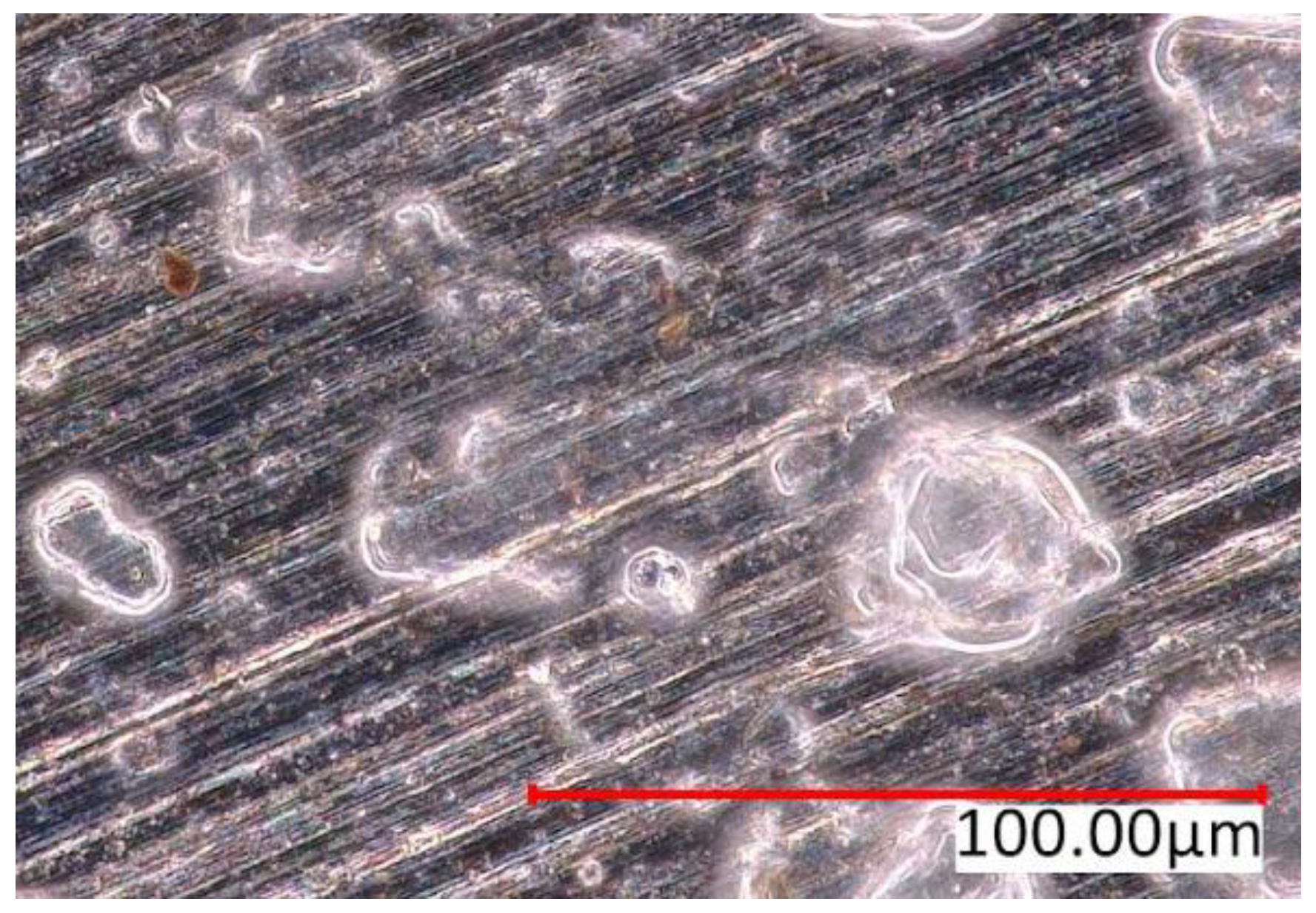

In Grind Test #1 (conducted at a 0.014 mm depth of cut at a 3.6 Q’ with a Bakelite bonded, diamond, abrasive wheel) no surface damage was found grinding irradiated samples. Fn averaged 56N and Ft 4.2N (e.g., the coefficient of grinding friction μ was .075). Grind Test #1 was repeated removing an additional 0.014 mm to a depth of 0.028mm. Fn and Ft average values were once again 56N and Ft 4.2N. When the same abrasive and process parameters were used to grind nonirradiated samples all showed evidence of surface damage (

Figure 4). Fn values in the control group averaged 62N and Ft was 8.3 N (μ=.134).

Test #1 was repeated grinding irradiated samples with a more aggressive diamond wheel of copper bond, 6x finer grit, and 25% higher hardness. The result was a 31% increase in the coefficient of grinding friction. Average Fn and Ft values increased to 72N and 7.1N (μ=.099) respectively. No cracks were observed in any of the test samples.

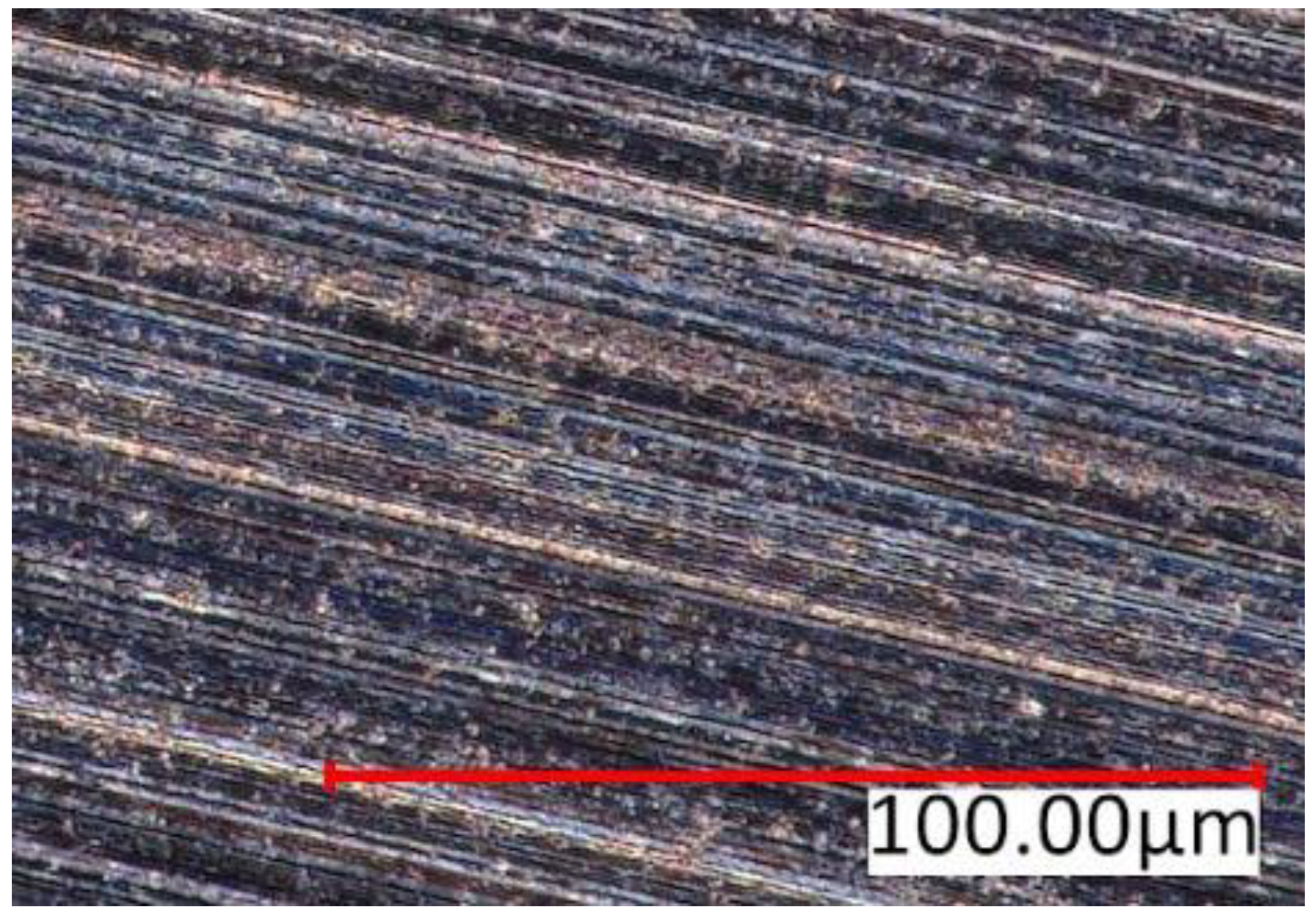

Grind Test #2 was conducted with the more aggressive abrasive from Test #1. All process parameters in Test #2 were identical to Test #1 with the exception that depth of cut was increased 72% to 0.024 mm. Grinding at 6.2 Q’ produced no cracks in any of the irradiated samples. Fn and Ft averaged 89N and 8.9N (μ=.10) respectively. When grinding nonirradiated samples average Fn was 94N and average Ft was 8.6N (μ=.09). All nonirradiated samples showed surface damage (

Figure 5).

In Grind Test #3 the abrasive and process parameters were unchanged compared to Test #2. Only the depth of cut increased in Test #3 to 0.03 mm. When grinding at 7.6 Q’ researchers found Fn and Ft averaged 91N and 7.5N respectively (μ=.08). No cracks were observed after grinding any of the irradiated samples (

Figure 6).

3.3. Experimental Conclusions

None of the samples which were laser heated to the melting point of Co showed any evidence of grind damage in any region of the 0.030mm deep HAZ from the minimum MRR tested (3.6 Q’) to the maximum (7.6 Q’). In contracts, all nonirradiated samples showed grind damage at every MRR tested.

Under minimum MRR conditions when grinding irradiated WC-Co with the least aggressive abrasive, the coefficient of cutting friction was 44% lower than grinding nonirradiated WC-Co. At lower cutting friction μ it followed that irradiated material removal occurred a markedly lower Fn (-10%) and Ft (-49%). Lower frictional forces and lower grinding forces explained the absence of cracking, but only under minimal MRR conditions.

When a more aggressive abrasive was used at 72% higher MRR, the frictional and grinding force differences between irradiated and nonirradiated were far less pronounced:

8.5% difference in μ

5.6% difference in Fn

3.3% difference in Ft

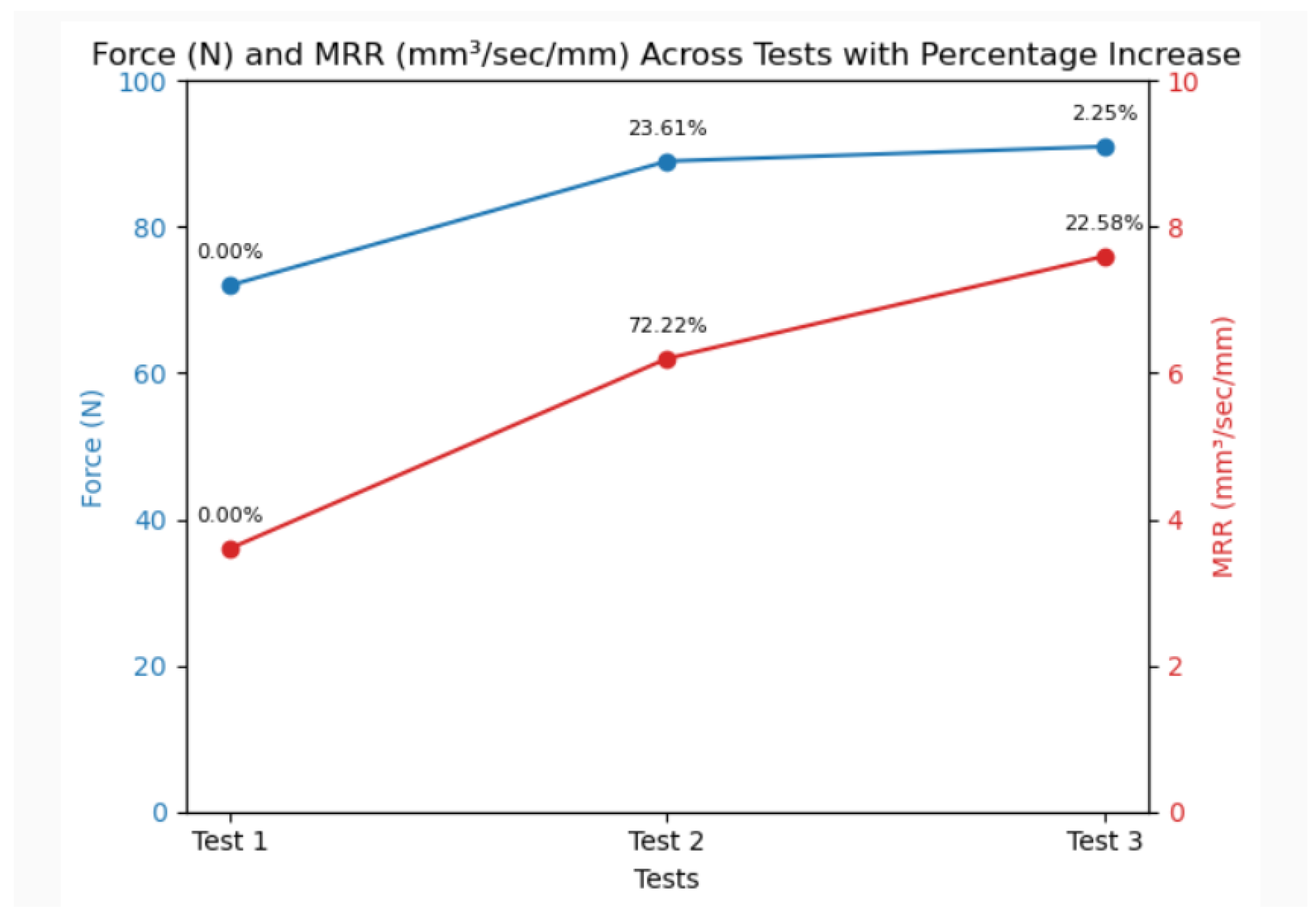

Even with these modest differences, none of the irradiated samples cracked, while all the nonirradiated ones did. Moreover, all irradiated samples ground defect free at higher normal and tangential forces than that which cracked nonirradiated samples. Clearly, irradiating samples to the melting temperature of the Co binder changed subsequent material removal dynamics. For instance, across Tests #1, #2, and #3 the percent increases in normal cutting force (+23.61% and +2.25% as shown in

Figure 7) lagged significantly behind the rate MRR increased (72.22% and 22.58%). Moreover, the rate of normal force increase rose at a decreasing rate.

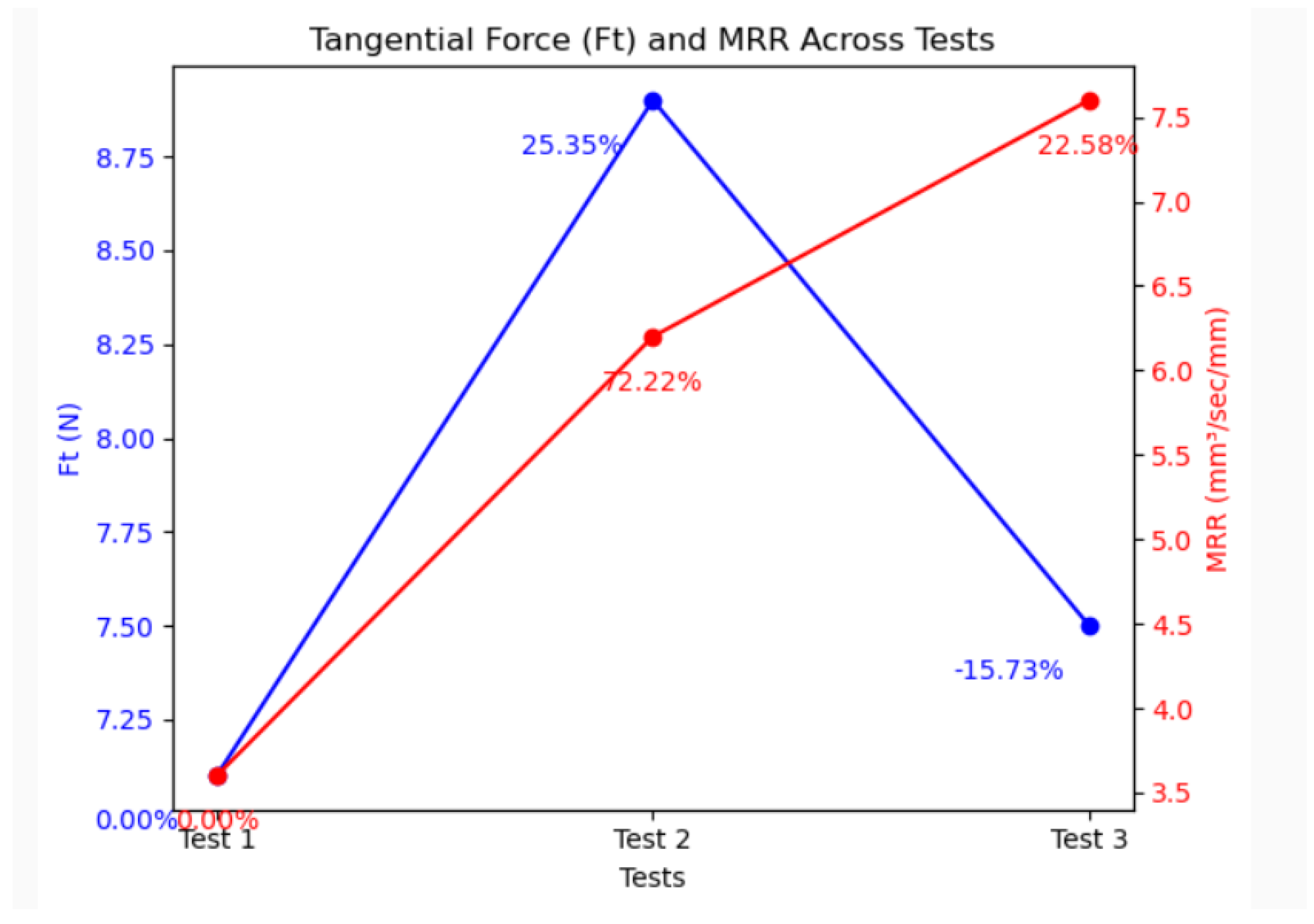

In the case of tangential forces, initially they too rose with the increase in normal force. However, as

Figure 8 shows, as MRR continued to rise tangential grinding force fell suggesting that removal of irradiated material became easier in sheer at very high loads.

What didn’t change was how irradiated material removal behaved at different depths in the HAZ. Two, successive, 0.014 mm grinds at the same MRR in the HAZ averaged the same Fn and Ft suggesting homogeneity in HAZ structure.

4. Discussion

Improvement in grindability of WC-Co after irradiation was attributed to several factors. For example, irradiating at 1,500°C with 10 ps pulses repeating every 400 kHz at a 1 mm/sec scan speed delivered sufficient thermal energy to melt Co (melting point ~1,495 °C) while leaving the WC phase (melting point ~2,870 °C) solid. Indeed, GIXRD data showed unchanged WC peak intensities and positions confirming structural stability of the WC phase. Measured reductions in Co peak intensities near the surface suggested localized binder modification without bulk phase transformation. Possible binder modifications attributed to laser heating included Co migration, thinning, or even partial vaporization. Melting relaxed residual stresses in the binder and at grain boundaries thereby reducing resistance to grain pull-out during grinding. Melting also exposed WC grain edges facilitating brittle-mode microfracture during grinding. Melting, therefore, explained both the improvement in MRR as well as observed lowering of tangential forces required for chip formation. After melting rapid re-solidification of Co prompted an unequal distribution of elements at Co-WC interfaces. Weakened interfacial bonds, therefore, formed in the partially amorphous structure near the surface. In this way, both melting and re-solidification explained observed loss of yield strength and improved ductility under load.

Researchers found under a very high MRR (7.6 Q′) irradiated samples remained defect-free despite only modest reductions in grinding forces. This suggested that the strength of the laser-induced, amorphous, HAZ structure near the surface was reduced just enough to ease material removal while also remaining high enough to prevent stress localizations that would otherwise have triggered cracking. Researchers, likewise, found consistent force measurements after repeated 0.014 mm grinding passes at the same MRR within HAZ produced. This indicated uniform microstructural changes down to at least 0.030 mm. At deeper levels (e.g., 0.045 mm and 0.060 mm), GIXRD data showed consistent Co and WC diffraction intensities suggesting (a) the HAZ did not extend beyond 0.045 mm and (b) the material below the HAZ retained its original properties.

This research opened the door to use of laser-assisted rough grinding to quickly near-net shape WC-Co followed by shallow finish grinding (approximately 0.015 mm) to restore the original material. However, further research is necessary to better understand the precise geometry and depth of the HAZ as it transitions back to the original material. To do this, cross-sectional techniques such as electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) are needed to reveal variations in grain orientation and crystallographic texture. Secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) will also provide valuable data on Co distribution. Addition tests to characterize the functional properties of the HAZ as it transitions back to its original state should include microhardness measurements (to detect recovery of baseline mechanical properties), ball-on-disc wear tests (to evaluate surface durability), and four-point probe conductivity testing (to assess the restoration of the Co network responsible for electrical conductivity). Once the depth at which material functional recovery is known, grinding parameters will need to be optimized to this depth.

Funding

This research was funded by the Timken Foundation Center for Precision Manufacturing

Data Availability Statement

Data associated with study has not been deposited into a publicly available repository, but data is available upon request.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Lukas Seggi for assisting in the set up and conducting of experiments as well as Wu Xubiao assisting in the research of existing literature.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANSI |

American National Standards Institute |

| CNC |

Computer Numerical Control |

| Co |

Cobalt |

| D3 |

AISI D3 Tool Steel |

| DAQ |

Data Acquisition |

| DLD |

Direct Laser Deposition |

| EBSD |

Electron Backscatter Diffraction |

| ECM |

Electrochemical Machining |

| EDM |

Electrical Discharge Machining |

| FLIR |

Forward Looking Infrared |

| Fn |

Normal Force |

| Ft |

Tangential Force |

| GIXRD |

Grazing Incidence X-ray Diffraction |

| HAZ |

Heat-Affected Zone |

| LADT |

Laser-Assisted Diamond Turning |

| LAM |

Laser-Assisted Machining |

| LDT |

Laser Diamond Turning |

| LUAT |

Laser-Ultrasonically Assisted Turning |

| MRR |

Material Removal Rate |

| Nd:YAG |

Neodymium-doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet |

| NI |

National Instruments |

| PLA |

Pulsed Laser Ablation |

| ps |

Picosecond(s) |

| Q′ |

Specific Material Removal Rate (mm³/min/mm) |

| SIMS |

Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry |

| USPL |

Ultrashort Pulse Laser |

| WC |

Tungsten Carbide |

| WC-Co |

Tungsten Carbide–Cobalt |

References

- Kadivar, M.; Azarhoushang, B.; Daneshi, A. Study of specific energy in grinding of tungsten carbide. Proceedings of the XIVth International Conference on High Speed Machining 2018.

- Burek, J.; Sałata, M.; Bazan, A. Influence of grinding parameters on the surface quality in the process of single-pass grinding of flute in solid carbide end mill. Mechanik 2018, 91(10), 808–810. [CrossRef]

- Calderón Urbina, J.P.; Daniel, C.; Emmelmann, C. Experimental and analytical investigation of cemented tungsten carbide ultra-short pulse laser ablation. Lasers in Manufacturing Conference 2013. [CrossRef]

- Karpuschewski, B.; Wolf, E.; Krause, M. Laser machining of cobalt cemented tungsten carbides. In: Towards Synthesis of Micro-/Nano-systems; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007.

- Marimuthu, S.; Dunleavey, J.; Smith, B. Picosecond laser machining of tungsten carbide. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2020, 92, 105318.

- You, K.; Fang, F. High effective laser assisted diamond turning of binderless tungsten carbide. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2022, 306, 117505. [CrossRef]

- Lickschat, P.; Möhwald, K.; Weidlich, P.; Römer, G. Femtosecond laser ablation of tungsten carbide: A study on efficiency and quality. Journal of Laser Applications 2019, 31(2), 022201.

- Zhang, C.; Cao, Y.; Jiao, F.; Wang, J. Wear mechanism analysis and its effect on the cutting process of CBN tools during laser ultrasonically assisted turning of tungsten carbide. International Journal of Refractory Metals and Hard Materials 2023, 113, 106498. [CrossRef]

- Gadalla, A.M.; Tsai, W. Electrical discharge machining of tungsten carbide–cobalt composites. Journal of the American Ceramic Society, in press. [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Zhang, X. Optimization of laser-assisted diamond turning of tungsten carbide. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2021, 64, 1–10.

- Singh, R.; Qureshi, A.J.; Pandey, P.M. Electrochemical machining of hard materials: A review. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2020, 278, 116–123.

- Wojciechowski, S.; Nowakowski, Z.; Majchrowski, R.; Królczyk, G. Surface texture formation in precision machining of direct laser deposited tungsten carbide. Advances in Manufacturing 2017, 5(3), 251–260. [CrossRef]

- Schubert, A.; Zeidler, H.; Röpcke, J. Electrochemical machining of tungsten carbide: Mechanisms and surface quality. Procedia CIRP 2015, 31, 201–206.

- Wojciechowski, S.; Nowakowski, Z.; Majchrowski, R.; Królczyk, G. Surface texture formation in precision machining of direct laser deposited tungsten carbide. Advances in Manufacturing 2017, 5(3), 251–260. [CrossRef]

- Hazzan, K.E.; Pacella, M.; See, T.L. Understanding the surface integrity of laser surface engineered tungsten carbide. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2022, 118(3–4), 1141–1163. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).