Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

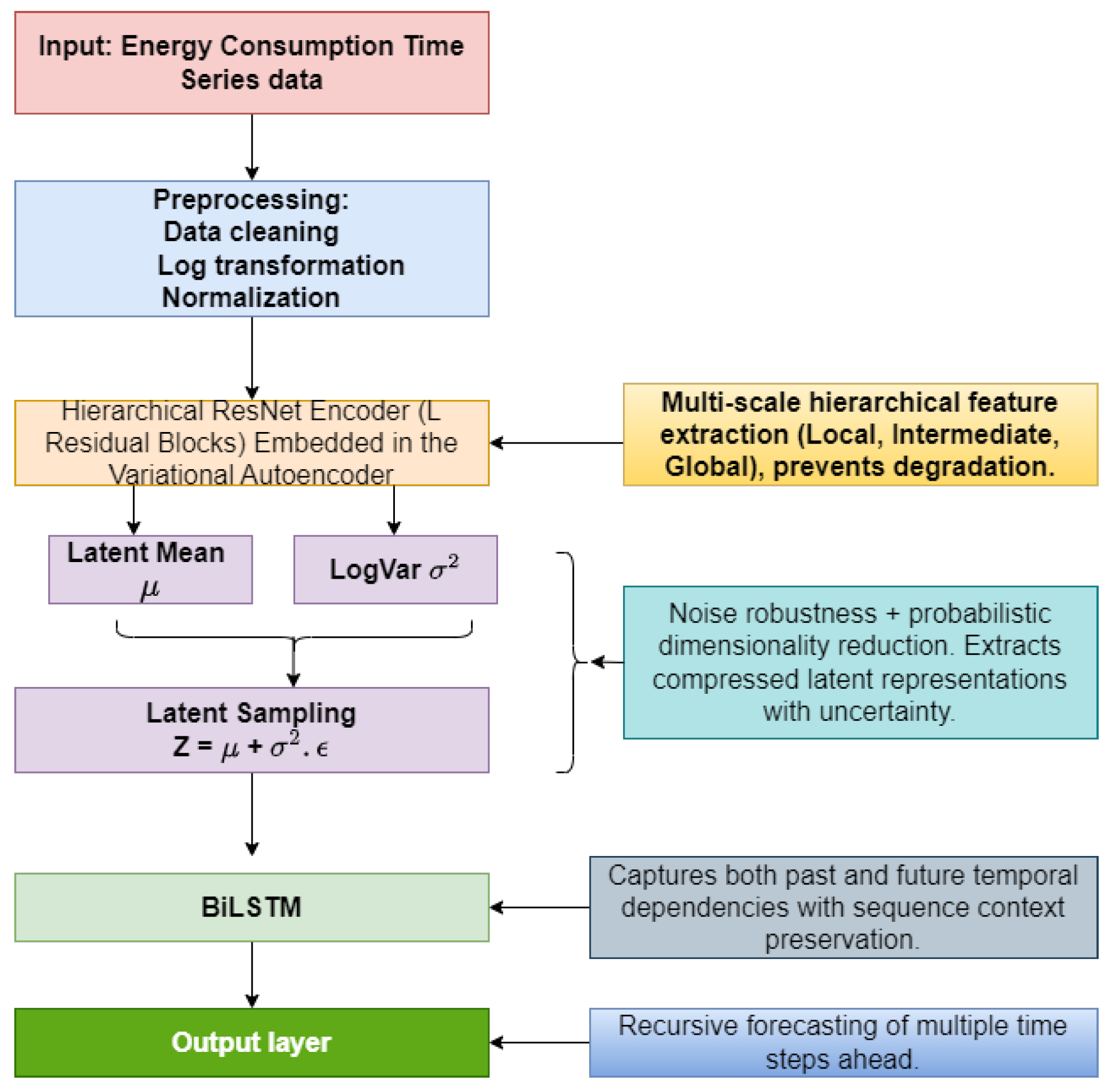

- We introduce an innovative dimensionality reduction-based hybrid deep learning framework algorithm that integrates a ResNet-embedded VAE with a BiLSTM architecture to improve feature extraction, uncover hidden patterns, and effectively address multi-seasonality and irregularities in energy consumption data.

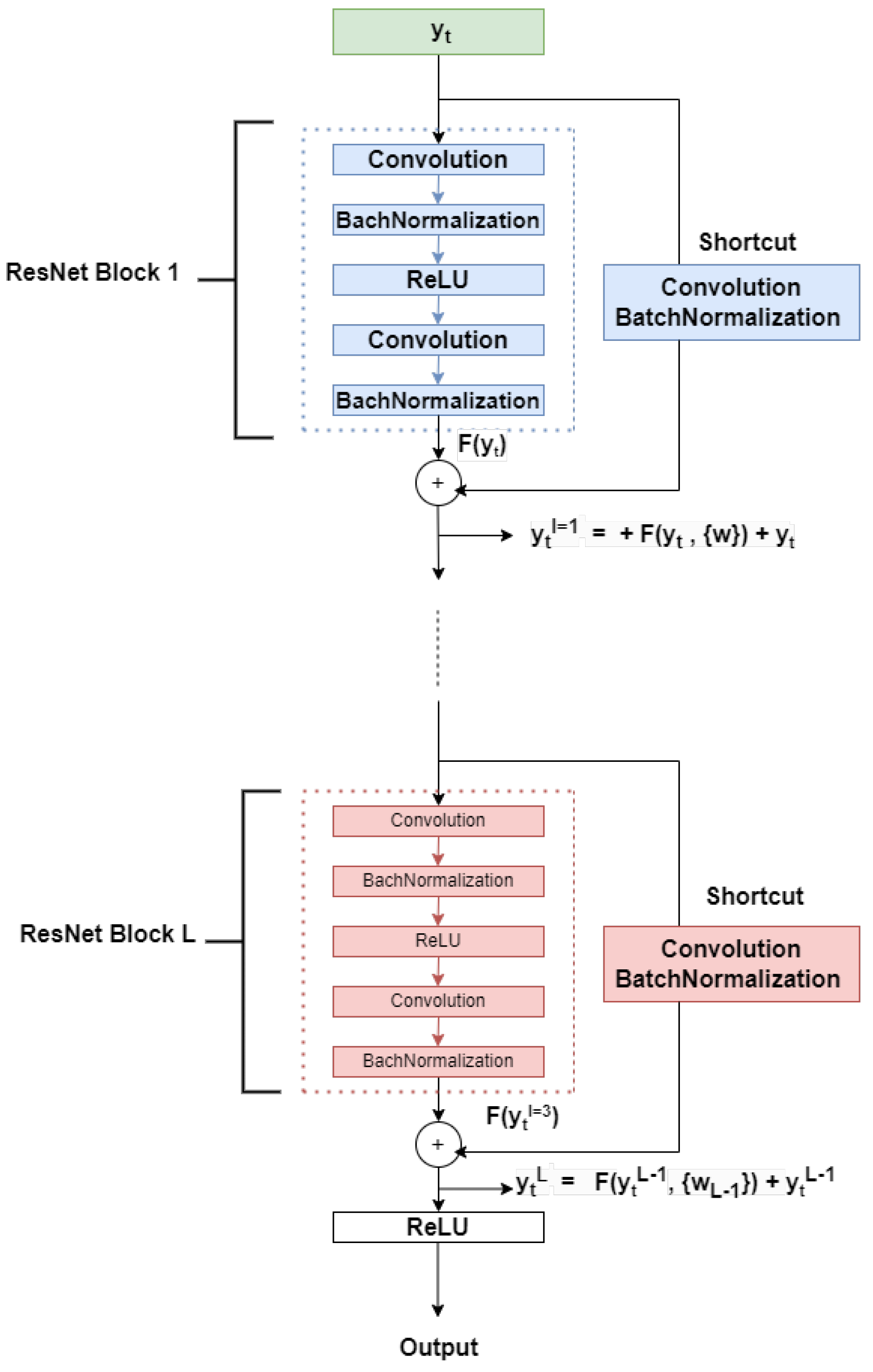

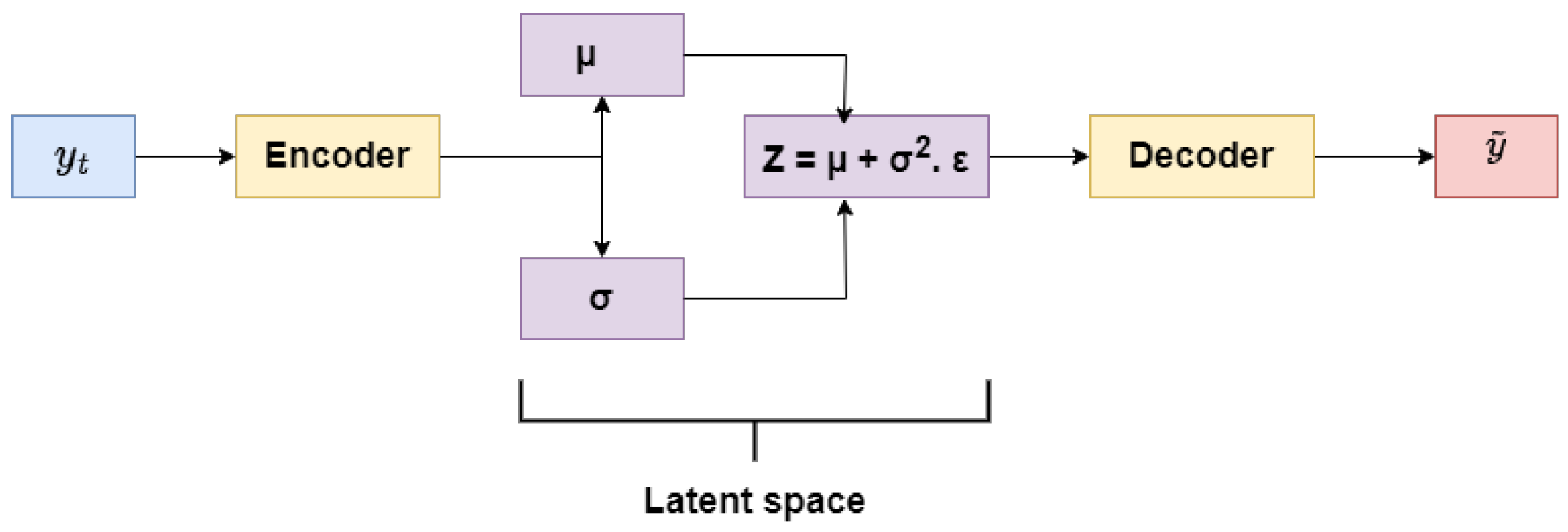

- The hybrid forecasting model integrates ResNet-embedded VAEs with BiLSTM networks to improve forecasting accuracy. VAEs reduce dimensionality and denoise data, while ResNet addresses the vanishing gradient problem in deeper networks using skip connections, enabling efficient training and multi-scale feature extraction. BiLSTM further enhances performance by capturing temporal dependencies from past and future data.

- To the best of our knowledge, this work is the first to introduce a ResNet-embedded VAE for time series forecasting, leveraging ResNet’s ability, initially developed for image recognition, to enhance local, mid-term, and global feature extraction. At the same time, overcoming vanishing gradients in deep VAEs improves the accuracy of energy consumption forecasts.

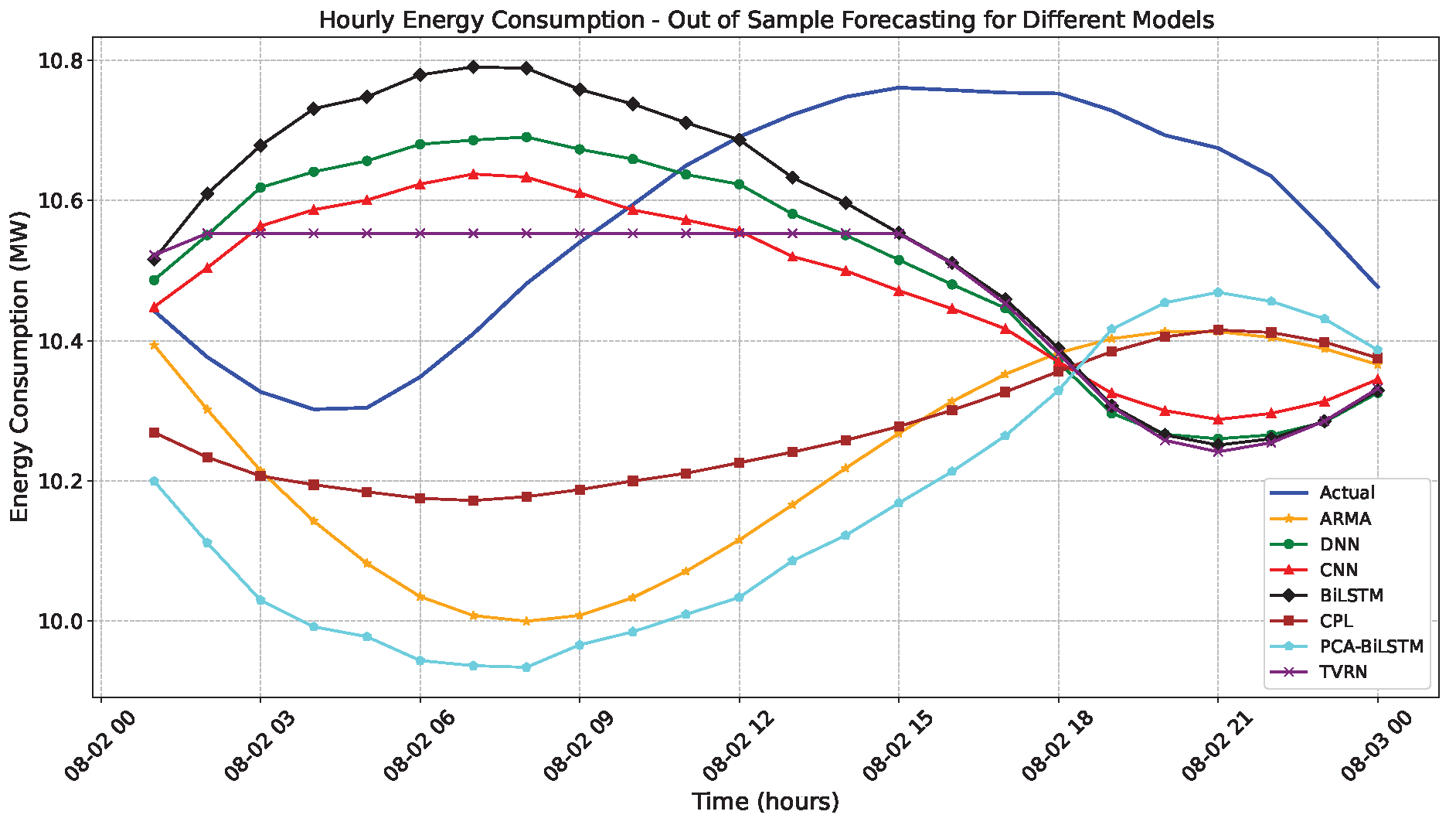

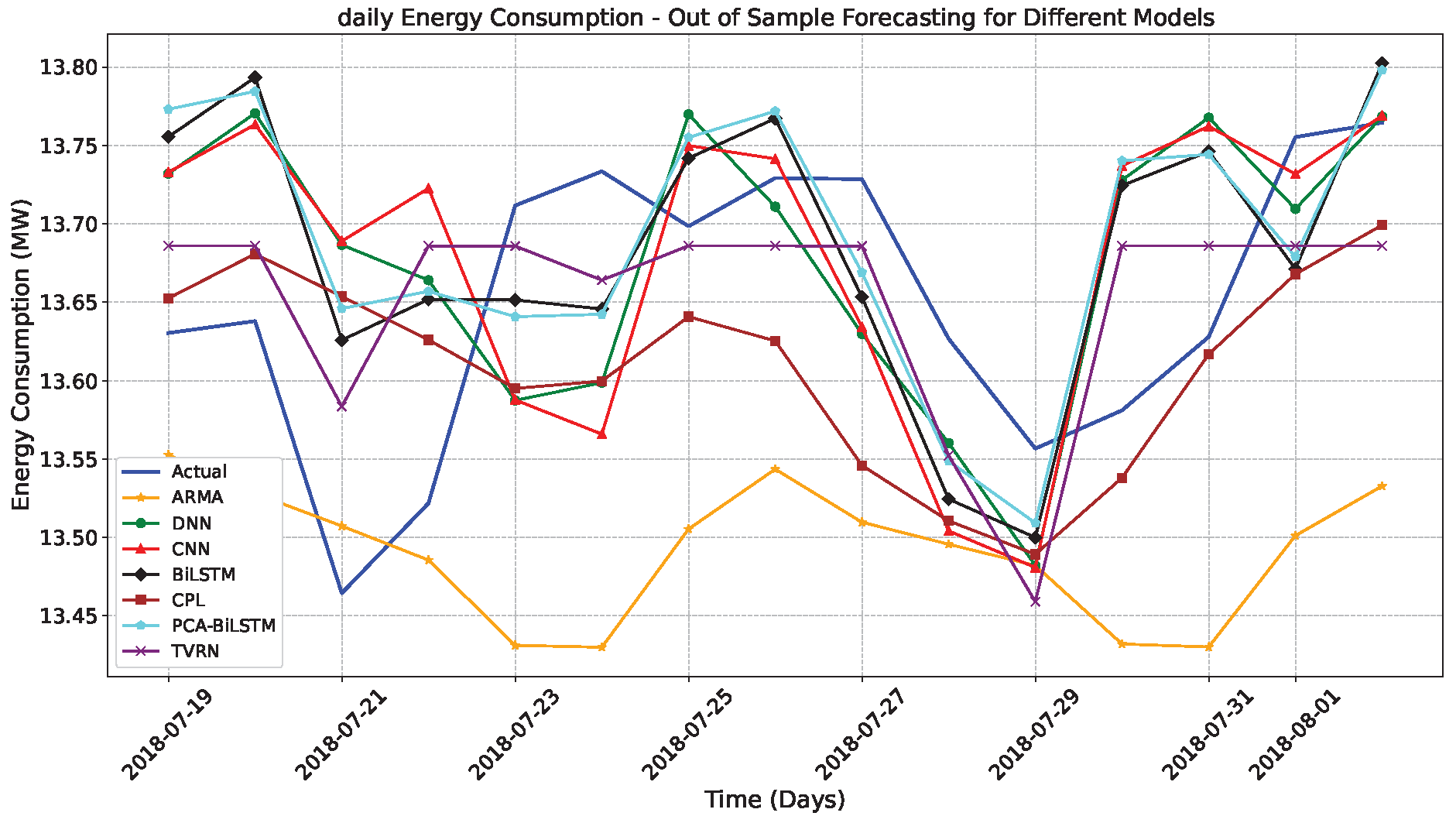

- The proposed model, TVRN, is evaluated by comparing its performance against traditional models, such as ARIMA, as well as key deep learning architectures, including DNN, CNN, and BiLSTM, and hybrid solutions, including PCA-BiLSTM and CPL, with a particular emphasis on hourly and daily energy consumption data.

2. Methodology

2.1. TVRN Algorithm Arichitecture

2.2. ResNet-embedded VAE

2.3. Modeling a BiLSTM to capture energy demand dependencies using a latent space representation

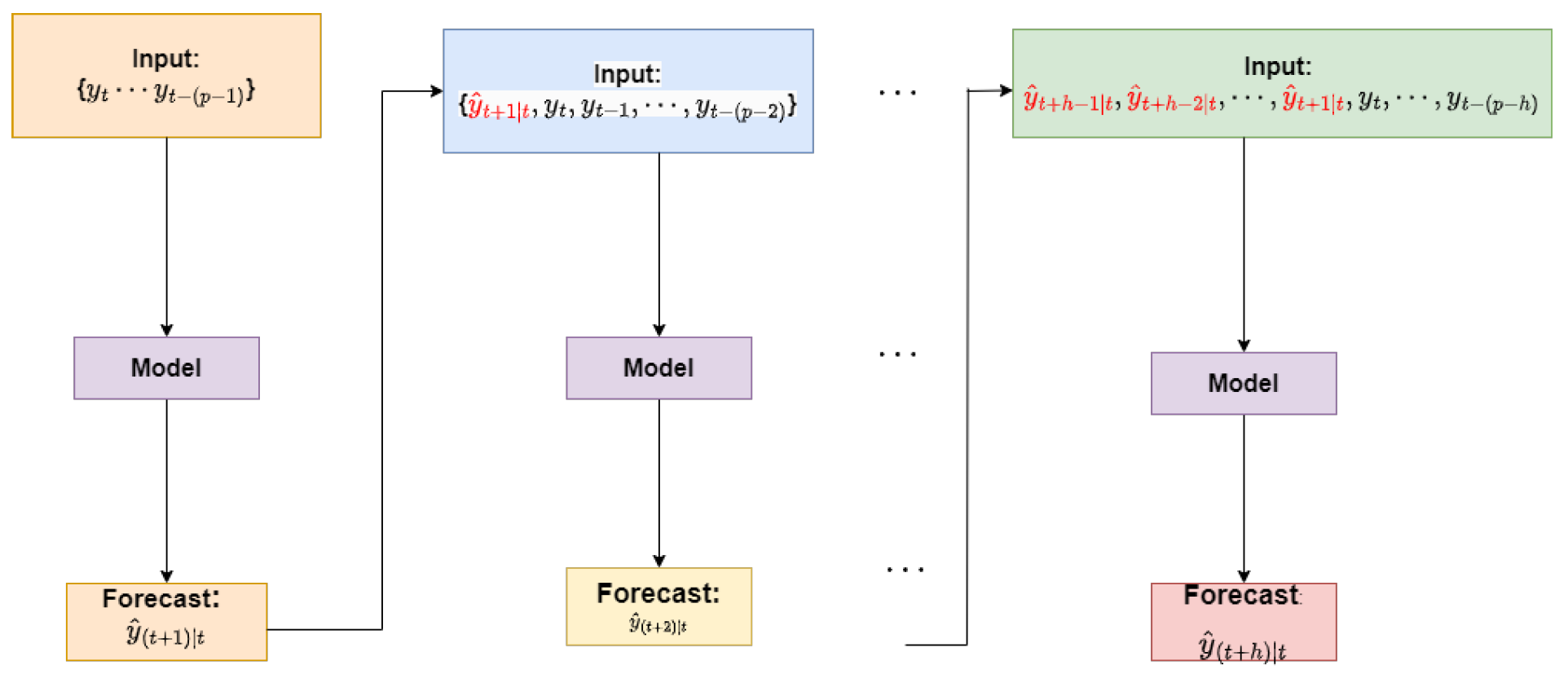

2.4. Out-of-Sample Energy Demand Forecasting Using Recursive Algorithms and Evaluation Metrics

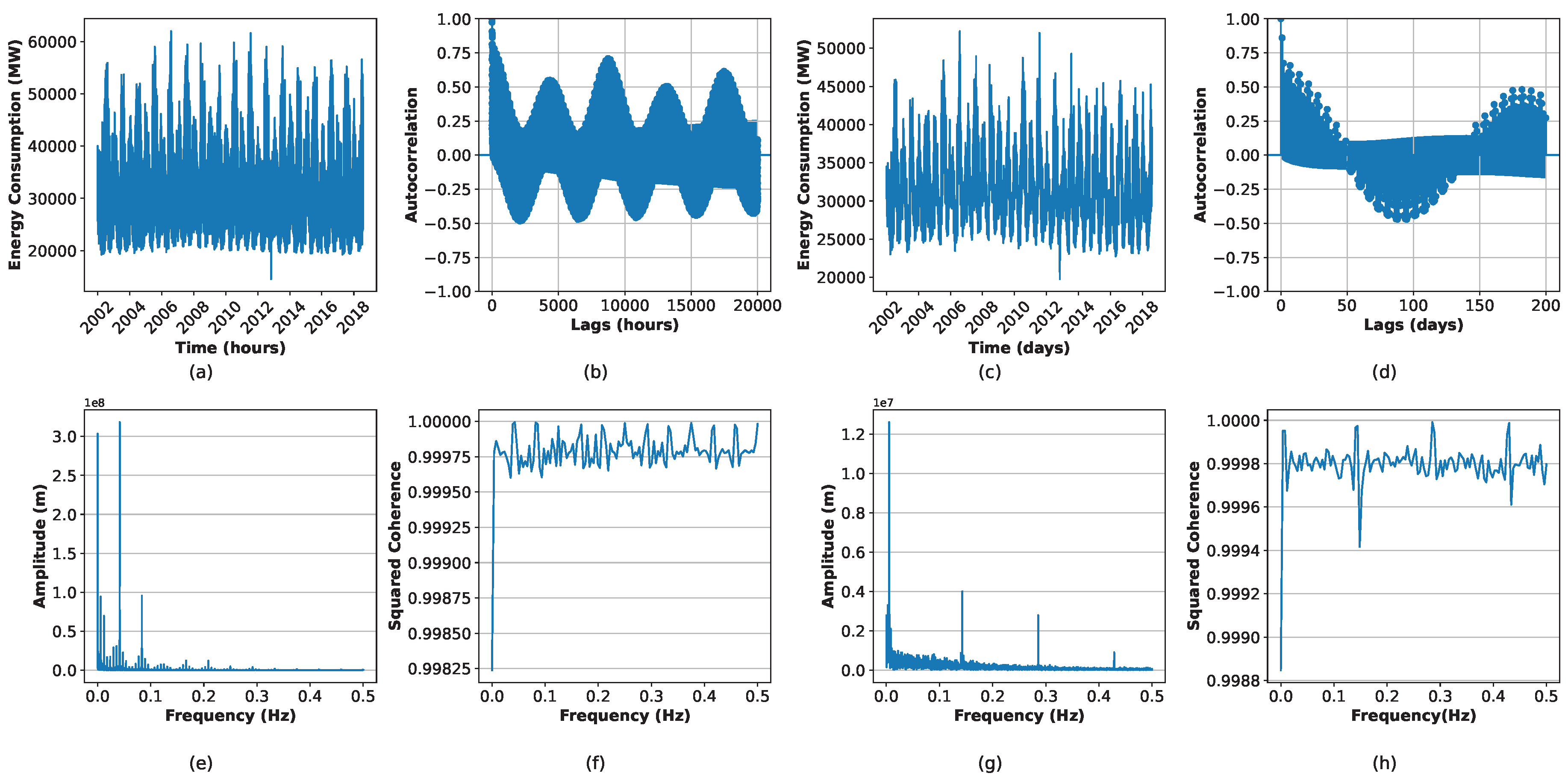

3. Data Descriptions

3.1. Design and Optimization of Hyperparameters

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TVRN | TEMPORAL VARIATIONAL RESIDUAL NETWORK |

| ARIMA | Autoregressive integrated moving average |

| ARMAX | AutoRegressive Moving Average with eXogenous |

| GARCH | Generalized AutoRegressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity |

| ARX | AutoRegressive with eXtra input |

| TARX | Threshold AutoRegressive with eXogenous |

| SVM | Support Vector Machines |

| ANNs | Artificial Neural Networks |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural NEtwork |

| CNNs | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| LSTM | Long Short Term Memory |

| BiLSTM | Bidirectional Long Short Term Memory |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| CEEMD | complementary ensemble empirical 81 mode decomposition |

| AE | Autoencoder |

| VAE | Varational Autoencoder |

| MWDN | Multilevel wavelet decomposition networks |

| (SVD) | Singular Value Decomposition |

References

- U.S. Energy Information Administration (2023), International Energy Outlook 2023.

- Suganthi, L., & Samuel, A. A. (2012). Energy models for demand forecasting—A review. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews, 16(2), 1223-1240.

- Chen, S. (2025). Data centres will use twice as much energy by 2030-driven by AI. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H. X., & Magoulès, F. (2012). A review on the prediction of building energy consumption. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 16(6), 3586-3592. [CrossRef]

- Wei, N., Li, C., Peng, X., Zeng, F., & Lu, X. (2019). Conventional models and artificial intelligence-based models for energy consumption forecasting: A review. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering, 181, 106187. [CrossRef]

- Klyuev, R. V., Morgoev, I. D., Morgoeva, A. D., Gavrina, O. A., Martyushev, N. V., Efremenkov, E. A., & Mengxu, Q. (2022). Methods of forecasting electric energy consumption: A literature review. Energies, 15(23), 8919. [CrossRef]

- National Renewable Energy Laboratory. (2022). Best practices in electricity load modeling and forecasting for long-term power sector planning (NREL/TP-6A20-81897). U.S. Department of Energy.

- Cuaresma, J. C., Hlouskova, J., Kossmeier, S., & Obersteiner, M. (2004). Forecasting electricity spot-prices using linear univariate time-series models. Applied Energy, 77(1), 87-106. [CrossRef]

- Bakhat, M., & Rosselló, J. (2011). Estimation of tourism-induced electricity consumption: The case study of the Balearic Islands, Spain. Energy economics, 33(3), 437-444. [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R. C., Contreras, J., Van Akkeren, M., & Garcia, J. B. C. (2005). A GARCH forecasting model to predict day-ahead electricity prices. IEEE transactions on power systems, 20(2), 867-874. [CrossRef]

- Moghram, I., & Rahman, S. (1989). Analysis and evaluation of five short-term load forecasting techniques. IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, 4(4), 1484-1491. [CrossRef]

- Weron, R., & Misiorek, A. (2008). Forecasting spot electricity prices: A comparison of parametric and semiparametric time series models. International journal of forecasting, 24(4), 744-763. [CrossRef]

- Dong, B., Cao, C., & Lee, S. E. (2005). Applying support vector machines to predict building energy consumption in tropical region. Energy and Buildings, 37(5), 545-553. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F., Cardeira, C., & Calado, J. M. F. (2014). The daily and hourly energy consumption and load forecasting using artificial neural network method: a case study using a set of 93 households in Portugal. Energy Procedia, 62, 220-229. [CrossRef]

- Lahouar, A., & Slama, J. B. H. (2015). Day-ahead load forecast using random forest and expert input selection. Energy Conversion and Management, 103, 1040-1051. [CrossRef]

- Taieb, S. B., & Hyndman, R. J. (2014). A gradient boosting approach to the Kaggle load forecasting competition. International journal of forecasting, 30(2), 382-394.

- Shi, H., Xu, M., & Li, R. (2017). Deep learning for household load forecasting—A novel pooling deep RNN. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 9(5), 5271-5280. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Z., Li, G. Q., Wang, G. B., Peng, J. C., Jiang, H., & Liu, Y. T. (2017). Deep Learning-Based Ensemble Approach for Probabilistic Wind Power Forecasting. Applied Energy, 188, 56-70. [CrossRef]

- Bedi, J., & Toshniwal, D. (2019). Deep Learning Framework for Forecasting Electricity Demand. Applied energy, 238, 1312-1326. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T. Y., & Cho, S. B. (2019). Predicting residential energy consumption using CNN-LSTM neural networks. Energy, 182, 72-81. [CrossRef]

- Xuan, W., Shouxiang, W., Qianyu, Z., Shaomin, W., & Liwei, F. (2021). A multi-energy load prediction model based on deep multi-task learning and an ensemble approach for regional integrated energy systems. International Journal of Electrical Power & Energy Systems, 126, 106583. [CrossRef]

- Wu, K., Wu, J., Feng, L., Yang, B., Liang, R., Yang, S., & Zhao, R. (2021). An attention-based CNN-LSTM-BiLSTM model for short-term electric load forecasting in an integrated energy system. International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems, 31(1), e12637.

- Maćkiewicz, A., & Ratajczak, W. (1993). Principal components analysis (PCA). Computers & Geosciences, 19(3), 303-342.

- Lee, D., & Seung, H. S. (2000). Algorithms for non-negative matrix factorization. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 13.

- Hinton, G. E., & Salakhutdinov, R. R. (2006). Reducing data dimensionality with neural networks. science, 313(5786), 504-507.

- Ng, A. (2011). Sparse autoencoder. CS294A Lecture notes, 72(2011), 1-19.

- Kingma, D. P., & Welling, M. (2013, December). Auto-encoding variational bayes.

- Kingma, D. P., & Welling, M. (2019). An introduction to variational autoencoders. Foundations and Trends® in Machine Learning, 12(4), 307-392.

- Zhang, Y. A., Yan, B., & Aasma, M. (2020). A novel deep learning framework: Prediction and analysis of finanEmpirical Mode Decomposition: A Noise-Assisted Data Analysis Methodions, 159, 113609.

- Wang, J., Wang, Z., Li, J., & Wu, J. (2018, July). Multilevel Wavelet Decomposition Network for Interpretable Time Series Analysis. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining (pp. 2437-2446).

- Dragomiretskiy, K., & Zosso, D. (2013). Variational mode decomposition. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, 62(3), 531-544.

- Kim, T., Lee, D., & Hwangbo, S. (2024). A deep-learning framework for forecasting renewable demands using variational auto-encoder and bidirectional long short-term memory. Sustainable Energy, Grids and Networks, 38, 101245. [CrossRef]

- Cai, B., Yang, S., Gao, L., & Xiang, Y. (2023). Hybrid variational autoencoder for time series forecasting. Knowledge-Based Systems, 281, 111079. [CrossRef]

- He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. (2016). Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition (pp. 770-778).

- Kingma, D. P., & Welling, M. (2013, December). Auto-encoding variational bayes.

- Chen, K., Chen, K., Wang, Q., He, Z., Hu, J., & He, J. (2018). Short-term load forecasting with deep residual networks. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 10(4), 3943-3952. [CrossRef]

- Orr, G. B., & Müller, K. R. (Eds.). (1998). Neural networks: tricks of the trade. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., Courville, A., & Bengio, Y. (2016). Deep learning (Vol. 1, No. 2). Cambridge: MIT press.

- Ioffe, S., & Szegedy, C. (2015, June). Batch normalization: Accelerating deep network training by reducing internal covariate shift. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 448-456). pmlr.

- Li, Z., Liu, F., Yang, W., Peng, S., & Zhou, J. (2021). A survey of convolutional neural networks: analysis, applications, and prospects. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, 33(12), 6999-7019.

- Doersch, C. (2016). Tutorial on variational autoencoders. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.05908.

- Siami-Namini, S., Tavakoli, N., & Namin, A. S. (2019, December). The performance of LSTM and BiLSTM in forecasting time series. In 2019 IEEE International conference on big data (Big Data) (pp. 3285-3292). IEEE.

- Hochreiter, S., & Schmidhuber, J. (1997). Long short-term memory. Neural computation, 9(8), 1735-1780.

- Cheng, H., Tan, P. N., Gao, J., & Scripps, J. (2006). Multistep-ahead time series prediction. In Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining: 10th Pacific-Asia Conference, PAKDD 2006, Singapore, April 9-12, 2006. Proceedings 10 (pp. 765-774). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Sorjamaa, A., Hao, J., Reyhani, N., Ji, Y., & Lendasse, A. (2007). Methodology for long-term prediction of time series. Neurocomputing, 70(16-18), 2861-2869. [CrossRef]

- Chevillon, G. (2007). Direct multi-step estimation and forecasting. Journal of Economic Surveys, 21(4), 746-785. [CrossRef]

- Aras, S., & Kocakoç, İ. D. (2016). A new model selection strategy in time series forecasting with artificial neural networks: IHTS. Neurocomputing, 174, 974-987. [CrossRef]

- Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W. A. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American statistical association, 74(366a), 427-431.

- Kwiatkowski, D., Phillips, P. C., Schmidt, P., & Shin, Y. (1992). Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root: How sure are we that economic time series have a unit root?. Journal of econometrics, 54(1-3), 159-178.

- Ullah, S., Xu, Z., Wang, H., Menzel, S., Sendhoff, B., & Bäck, T. (2020, July). Exploring clinical time series forecasting with meta-features in variational recurrent models. In 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) (pp. 1-9). IEEE.

- Chen, W., Tian, L., Chen, B., Dai, L., Duan, Z., & Zhou, M. (2022, June). Deep variational graph convolutional recurrent network for multivariate time series anomaly detection. In International conference on machine learning (pp. 3621-3633). PMLR.

- Choi, H., Ryu, S., & Kim, H. (2018, October). Short-term load forecasting based on ResNet and LSTM. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Control, and Computing Technologies for Smart Grids (SmartGridComm) (pp. 1-6). IEEE.

- Kim, T. Y., & Cho, S. B. (2019). Predicting residential energy consumption using CNN-LSTM neural networks. Energy, 182, 72-81. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z., & Huang, N. E. (2009). Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition: A Noise-Assisted Data Analysis Method. Advances in adaptive data analysis, 1(01), 1-41. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. A., Yan, B., & Aasma, M. (2020). A novel deep learning framework: Prediction and analysis of financial time series using CEEMD and LSTM. Expert systems with applications, 159, 113609. [CrossRef]

- Gensler, A., Henze, J., Sick, B., & Raabe, N. (2016, October). Deep Learning for solar power forecasting—An approach using AutoEncoder and LSTM Neural Networks. In 2016 IEEE international conference on systems, man, and cybernetics (SMC) (pp. 002858-002865). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Song, X., Wu, Q., & Cai, Y. (2023, May). Short-term power load forecasting based on GRU neural network optimized by an improved sparrow search algorithm. In Eighth International Symposium on Advances in Electrical, Electronics, and Computer Engineering (ISAEECE 2023) (Vol. 12704, pp. 736-744). SPIE.

| Operation | Forward LSTM | Backward LSTM |

|---|---|---|

| Forget Gate | ||

| Input Gate | ||

| Output Gate | ||

| Cell Input | ||

| Cell State | ||

| Hidden State |

| Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Convolution | 64 Filters, Kernel Size 3, Stride 1 | Initial layer settings |

| ResNet Block 1 | 64 Filters, Stride 1, Kernel Size 3 | Includes Shortcut |

| ResNet Block 2 | 32 Filters, Stride 1, Kernel Size 3 | Includes Shortcut |

| ResNet Block 3 | 16 Filters, Stride 1, Kernel Size 3 | Includes Shortcut |

| ResNet Block 4 | 16 Filters, Stride 1, Kernel Size 3 | Includes Shortcut |

| Pooling Type | MaxPooling, Size 2, Stride 1, padding=’same’ | Pooling settings |

| Activation Functions | ReLU, Tanh | Types of activation used |

| Regularization | L2 (0.0001) | Regularization for BiLSTMlayers |

| Batch Normalization | Applied | Used in all ResNet blocks and shortcuts |

| Horizon | ARIMA | DNN | BiLSTM | CNN | CPL | PCA-BiLSTM | TVRN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | |||||||

| train | 0.228 | 0.070 | 0.024 | 0.034 | 0.175 | 0.015 | 0.076 |

| h = 1 | 0.052 | 0.079 | 0.028 | 0.032 | 0.259 | 0.021 | 0.003 |

| h = 12 | 0.424 | 0.209 | 0.298 | 0.250 | 0.270 | 0.304 | 0.158 |

| h = 24 | 0.402 | 0.304 | 0.324 | 0.297 | 0.297 | 0.322 | 0.261 |

| MAE | |||||||

| train | 0.182 | 0.058 | 0.023 | 0.027 | 0.139 | 0.013 | 0.038 |

| h = 1 | 0.052 | 0.079 | 0.028 | 0.032 | 0.259 | 0.021 | 0.003 |

| h = 12 | 0.369 | 0.177 | 0.258 | 0.212 | 0.269 | 0.261 | 0.132 |

| h = 24 | 0.363 | 0.269 | 0.291 | 0.264 | 0.296 | 0.288 | 0.224 |

| Horizon | ARIMA | DNN | BiLSTM | CNN | CPL | PCA-BiLSTM | TVRN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSE | |||||||

| train | 0.186 | 0.062 | 0.061 | 0.062 | 0.125 | 0.060 | 0.068 |

| h = 1 | 0.077 | 0.073 | 0.083 | 0.078 | 0.059 | 0.099 | 0.005 |

| h = 7 | 0.180 | 0.128 | 0.114 | 0.125 | 0.200 | 0.118 | 0.079 |

| h = 15 | 0.178 | 0.129 | 0.120 | 0.133 | 0.167 | 0.123 | 0.086 |

| MAE | |||||||

| train | 0.047 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.048 | 0.095 | 0.047 | 0.050 |

| h = 1 | 0.077 | 0.073 | 0.083 | 0.078 | 0.059 | 0.099 | 0.005 |

| h = 7 | 0.149 | 0.107 | 0.094 | 0.106 | 0.190 | 0.100 | 0.069 |

| h = 15 | 0.159 | 0.111 | 0.103 | 0.115 | 0.147 | 0.106 | 0.074 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).