Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Bi-Sn alloy: Furnace set at 300 °C (peak 320 °C due to ±20 °C tolerance). After thermal stabilization, pre-weighed Bi and Sn were introduced.

- Bi-Sn-Sb alloy: Furnace set at 650 °C (peak 670 °C). After stabilization, Sb was added to the pre-melted Bi-Sn matrix.

- Bi-Sn-Ag alloy: Furnace set at 980 °C (peak 1000 °C). Ag was melted first, followed by the addition of Bi and Sn.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of Bi-Sn Based Solder Alloys

3.1.1. Chemical Composition

3.1.2. Optical Microscopy

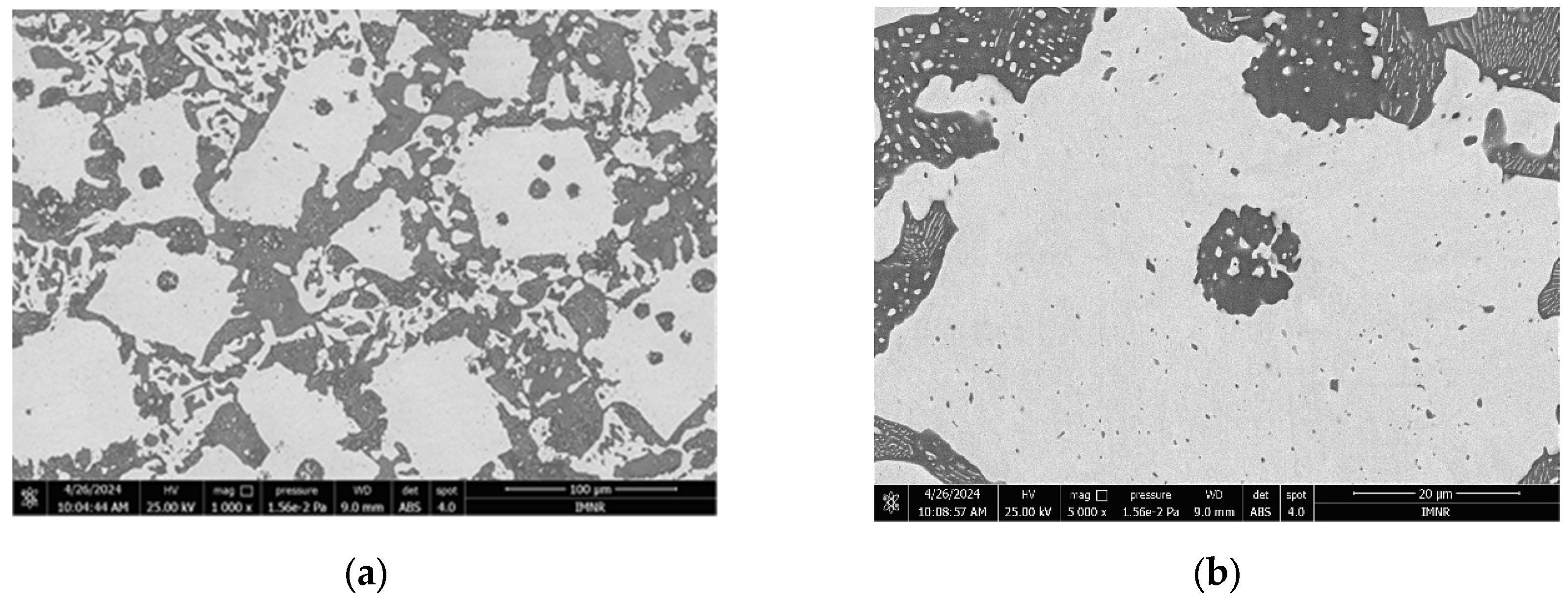

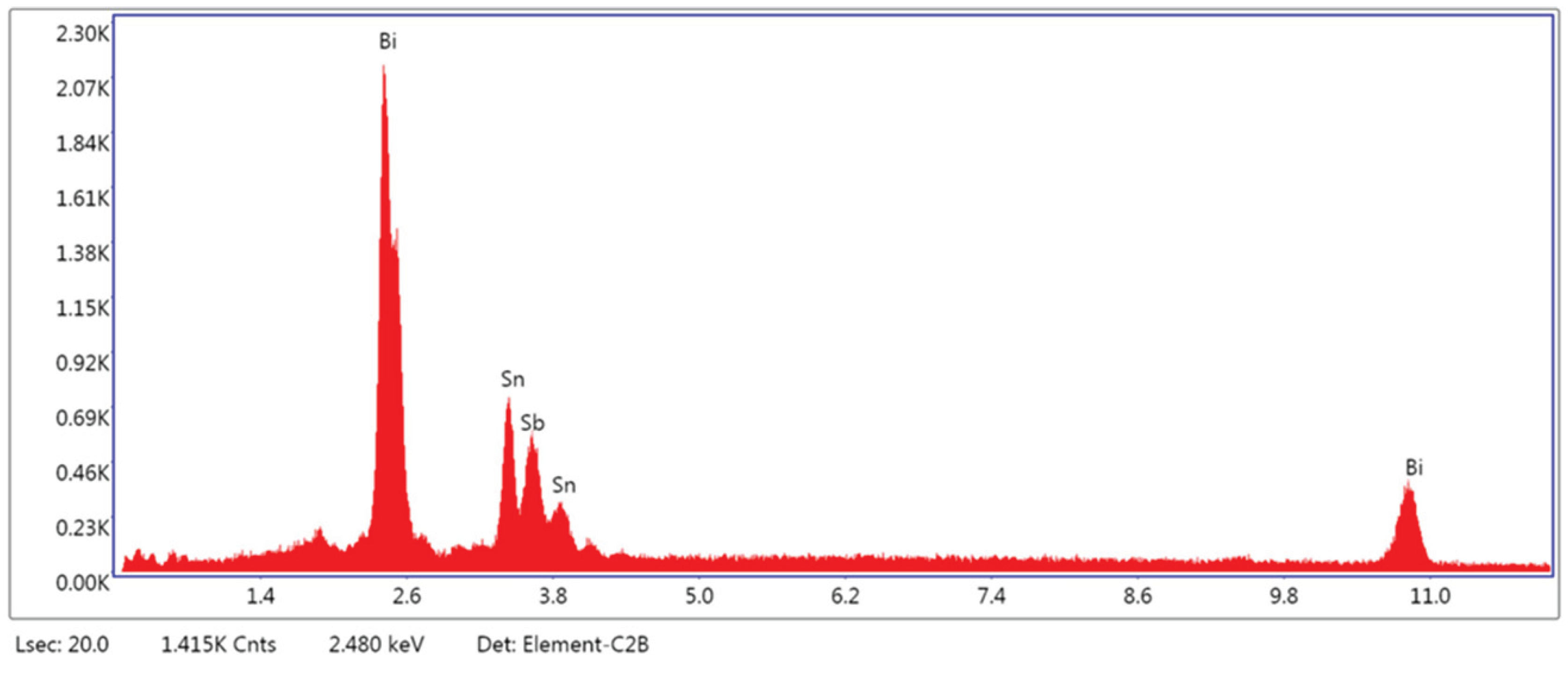

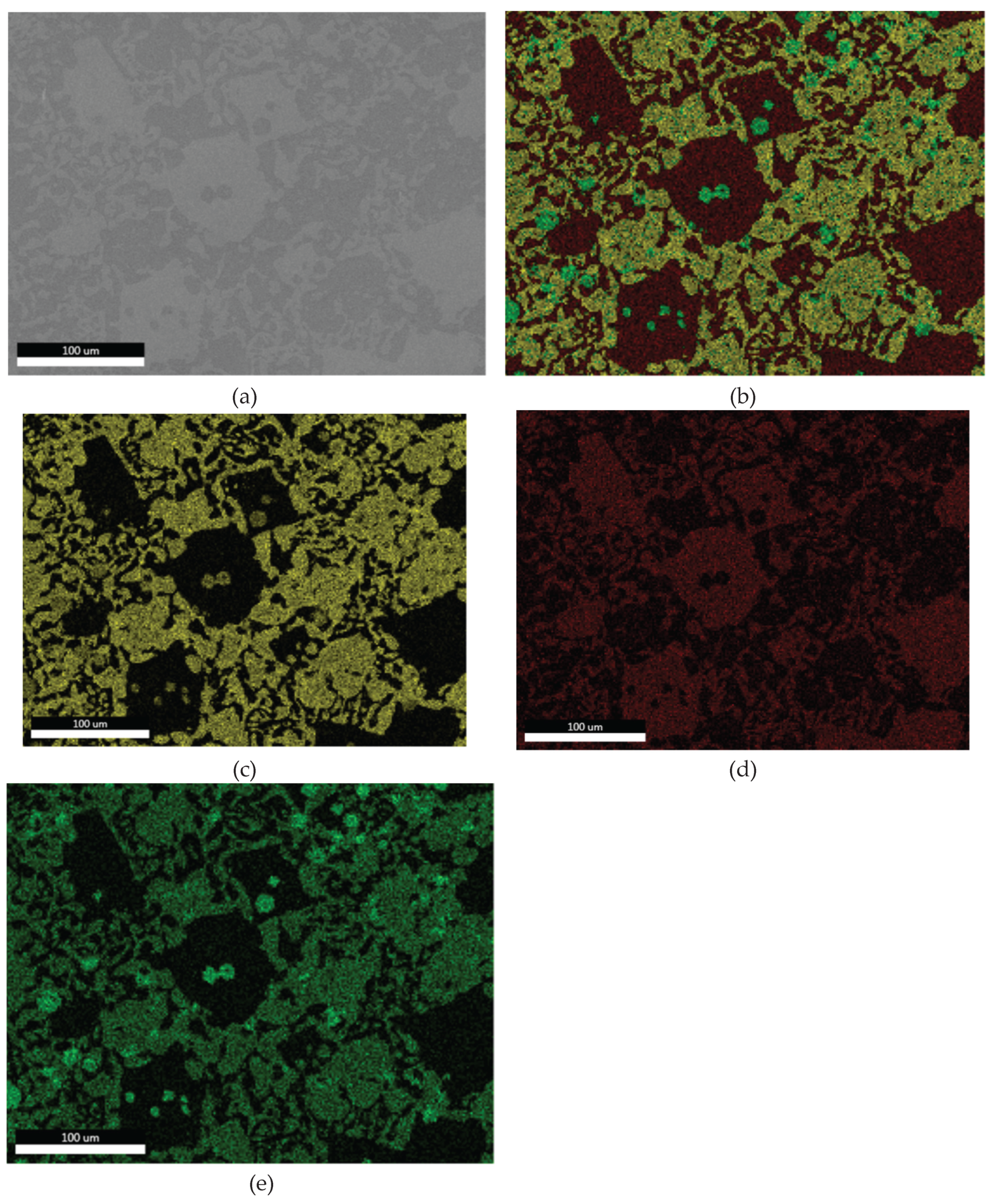

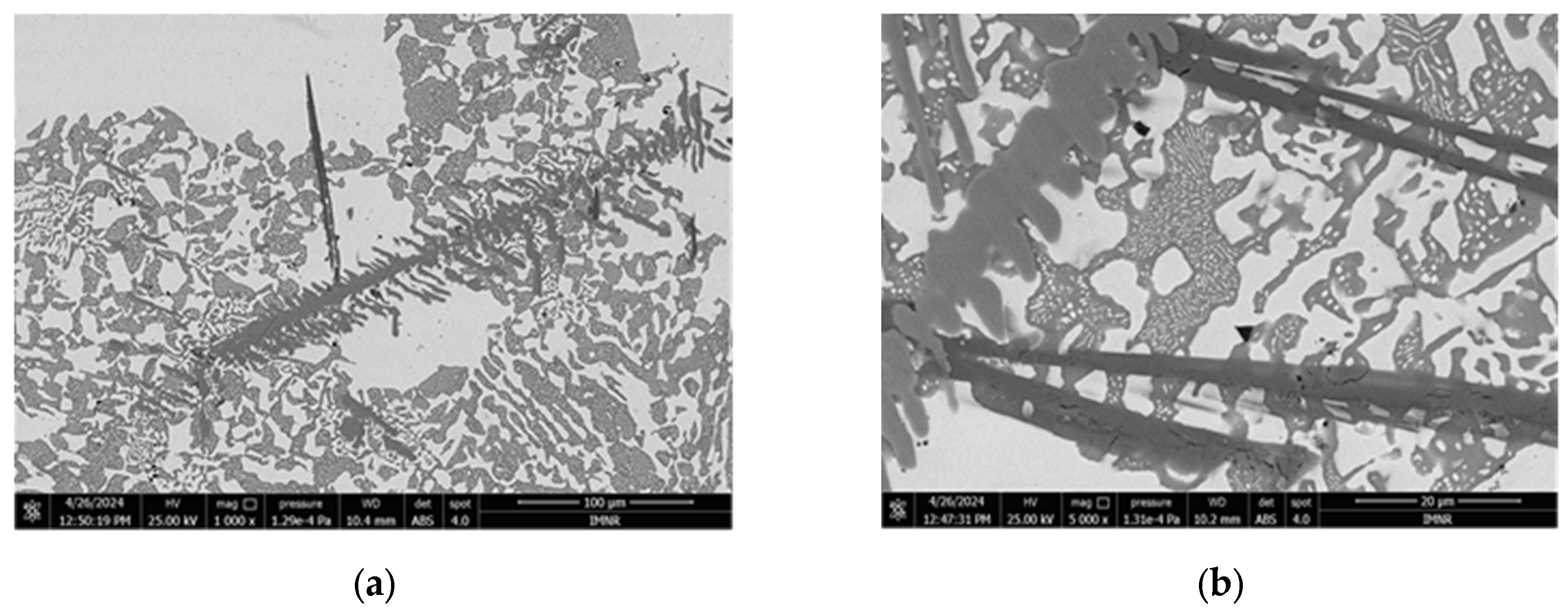

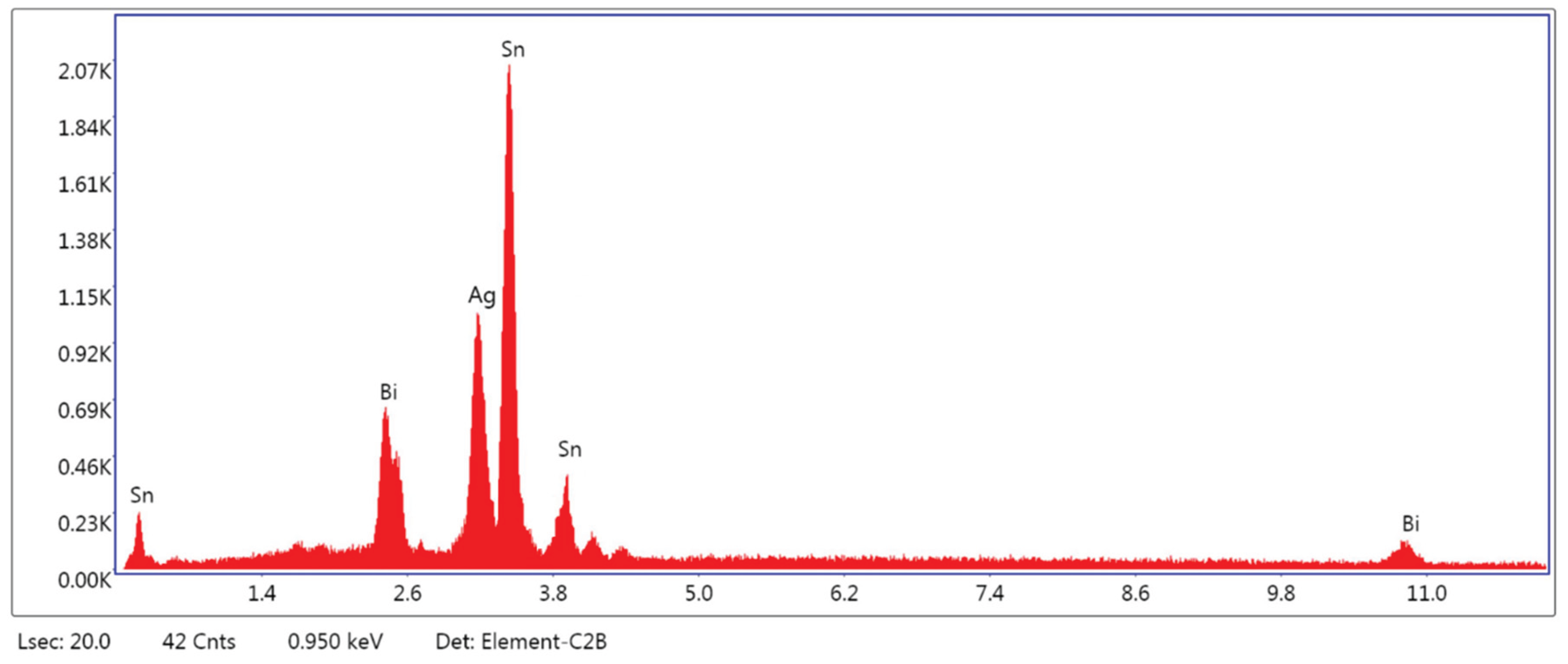

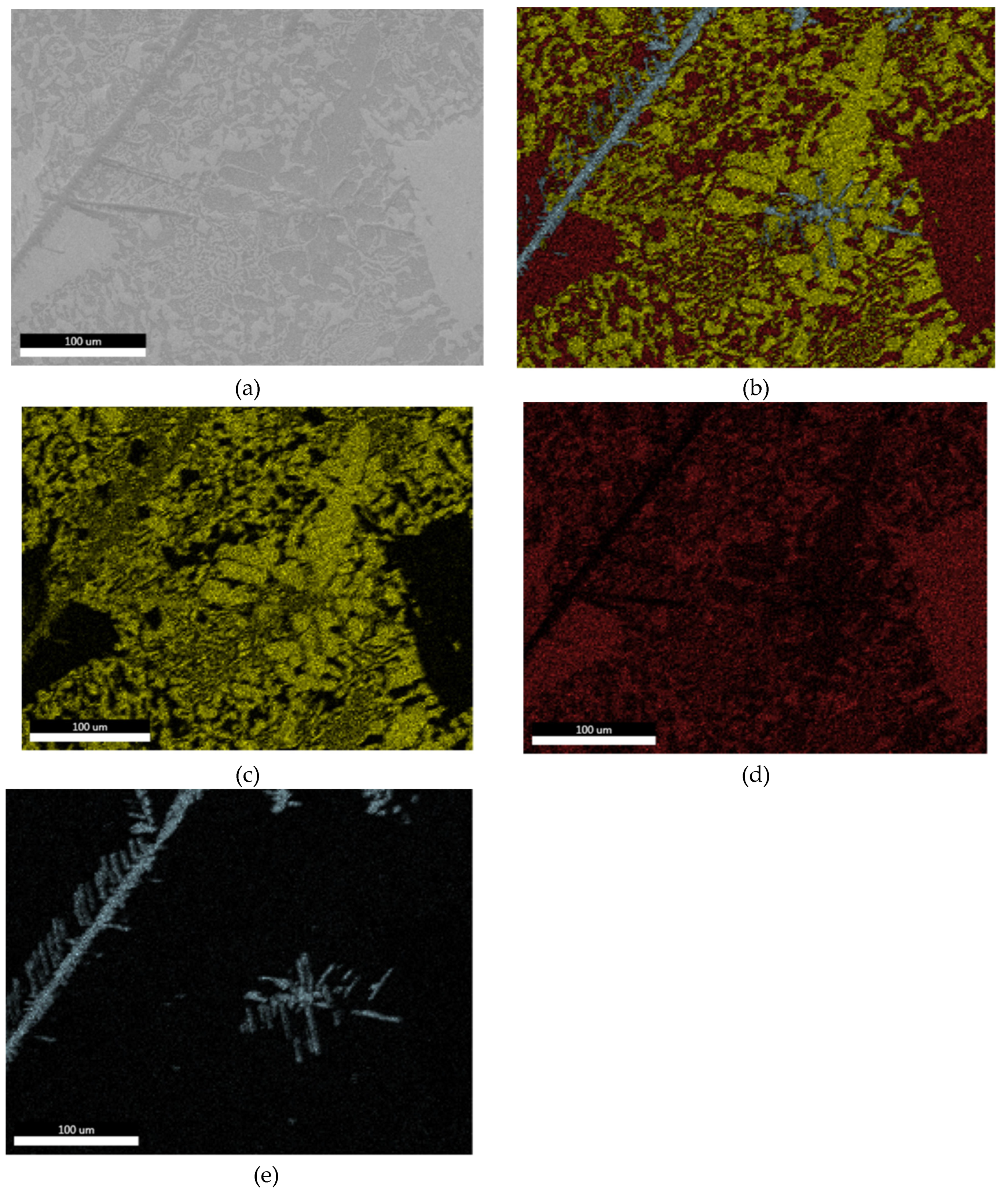

3.1.3. Microstructural and Compositional Analysis by SEM-EDX and BSE Imaging

3.2. Thermal and Electrical Conductivity of Bi-Sn Based Solder Alloys

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Balakrishnan, R.B.; Anand, K.P.; Chiya, A.B. Electrical and electronic waste: a global environmental problem. Waste Manag. Res. 2007, 25, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apurva, G.; Snehal, M.; Girish, R.P. An Overview of Digital Transformation and Environmental Sustainability: Threats, Opportunities, and Solutions. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaf, S.; Babbitt, C.W. Disruption risks to material supply chains in the electronics sector. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 167, 105248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abtew, M.; Selvaduray, G. Lead-free Solders in Microelectronics. Mater. Sci. Eng.: R.: Rep. 2000, 27, 95–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xue, Sb.; Gao, Ll.; et al. Development of Sn–Zn lead-free solders bearing alloying elements. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2009, 21, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Lim, S.; Hanifah, M.M.M.; Matteini, P.; Yusoff, W.Y.W.; Hwang, B. An Introductory Overview of Various Typical Lead-Free Solders for TSV Technology. Inorganics 2025, 13, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA – European Environment Agency. European zero pollution dashboards Progress in regulating lead (Signal). Available online: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/european-zero-pollution-dashboards/indicators/progress-in-regulating-lead-signal (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- EUR-Lex. Document 52023SC0760, COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT EVALUATION of Directive 2011/65/EU on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment Accompanying the document REPORT FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS on the review of the Directive on the restriction of the use of certain hazardous substances in electrical and electronic equipment, SWD/2023/760 final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=SWD%3A2023%3A760%3AFIN (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Ho, K. Understanding RoHS (Restriction of Hazardous Substances) Compliance: A Comprehensive Guide. Nemko. 2024. Available online: https://www.nemko.com/blog/rohs-explained-a-comprehensive-guide (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Razak, N.R.A.; Salleh, M.A.A.M.; Saud, N.; Said, R.M.; Ramli, M.I.I. Influence of Bismuth in Sn-Based Lead-Free Solder – A Short Review. Solid State Phenom. 2018, 273, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Rajendran, S.H.; Jung, J.P. Low Melting Temperature Sn-Bi Solder: Effect of Alloying and Nanoparticle Addition on the Microstructural, Thermal, Interfacial Bonding, and Mechanical Characteristics. Metals 2021, 11, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koleňák, R.; Provazník, M.; Kostolný, I.; Kar, A. Soldering by the Active Lead-Free Tin and Bismuth-Based Solders. In Lead Free Solders; Kar, A., Ed.; IntechOpen, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianco, P.T.; Rejent, J.; Grant, R. Development of Sn-Based, Low Melting Temperature Pb-Free Solder Alloys. Mater. Trans. 2004, 45, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribas, M.; Kumar, A.; Kosuri, D.; Rangaraju, R.R.; Choudhury, P.; Suresh, S.; Sarkar, S. Low temperature soldering using Sn-Bi alloys. Proceedings of SMTA International, Rosemont, IL, USA, Date of Conference (17-21 September 2017). [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, M.S.; Osman, S.A.; Efzan, E. The Development of Low-Temperature Lead-Free Solders using Sn-Bi Solders Alloys. Int. J. Recent Technol. Eng. 2019, 8, 11956–11962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Xue, S.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Tatsumi, H.; Nishikawa, H. Influence of Isothermal Aging on Microstructure and Shear Property of Novel Epoxy Composite SAC305 Solder Joints. Polymers 2023, 15, 4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.A.; Chen, F.Y.; Gao, R.; Ho, C.E.; Nishikawa, H.; Chen, C.M. Effect of Bi Addition on Melting Behavior, Solder Joint Strength, and Thermal Aging Resistance of Sn-3.5Ag/Cu Joints. JOM 2025, 77, 4206–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straubinger, D.; Khan, Z.; Koltay, P.; Zengerle, R.; Kartmann, S.; Shu, Z. Additively Manufactured Flexible Electronics with Selectively Soldered Surface-mounted Devices Utilising StarJet Technology. IEEE 10th Electronics System-Integration Technology Conference (ESTC), Berlin, Germany, Date of Conference (11-13 September 2024). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, Z.; Zhou, H.; Li, R.; et al. Challenges and recent prospectives of 3D heterogeneous integration. e-Prime - Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. 2022, 2, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, J.H. Recent Advances and New Trends in Nanotechnology and 3D Integration for Semiconductor Industry. IEEE International 3D Systems Integration Conference (3DIC), Osaka, Japan, Date of Conference (31 January 2012 - 02 February 2012). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Khan, A.J.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Y. Advancements in Enhancing Structural Reliability and Functional Properties in 3D Printed Materials. In Production Engineering PART OF IntechOpen Book Series: Industrial Engineering and Management; Korhan, O., Ed.; Publisher IntechOpen, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Collins, M.N. Improved Reliability and Mechanical Performance of Ag Microalloyed Sn58Bi Solder Alloys. Metals 2019, 9, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, K.S.; Hwang, C.W.; Suganuma, K. Effect of composition and cooling rate on microstructure and tensile properties of Sn–Zn–Bi alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2003, 352, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Tan, X.F.; McDonald, S.D.; Nogita, K. Phase Transformations and Mechanical Properties in In–Bi–Sn Alloys as a Result of Low-Temperature Storage. Materials 2024, 17, 3669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.L.; Reinhart, G.; Nguyen-Thi, H.; Mangelinck-Noël, N.; Garcia, A.; Spinelli, J.E. Microstructural development and mechanical properties of a near-eutectic directionally solidified Sn–Bi solder alloy. Mater. Charact. 2015, 107, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tu, K.N. Low melting point solders based on Sn, Bi, and In elements. Mater. Today Adv. 2020, 8, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Tan, X.F.; McDonald, S.D.; Nogita, K. Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of Binary In-Sn Alloys for Flexible Low Temperature Electronic Joints. Materials 2022, 15, 8321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, S.M.; Yow, H.K.; Yeoh, K.H. Lead-Free BiSnAg Soldering Process for Voidless Semiconductor Packaging. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 13, 1310–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, A.; Nowottnick, M. Composite Soldering Materials Based on BiSnAg for High-Temperature Stable Solder Joints. J. Microelectron. Packag. 2022, 19, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianco, P.T.; Rejent, J.A. Properties of ternary Sn-Ag-Bi solder alloys: Part I—Thermal properties and microstructural analysis. J. Electron. Mater. 1999, 28, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavan, J.S.; Pazhani, A.; Amer, M.; Patel, N.; Unnikrishnan, T.G. Microstructural Evolution and Phase Transformation on Sn–Ag Solder Alloys under High-Temperature Conditions Focusing on Ag3Sn Phase. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2400660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Sharma, A.; Jung, J.P. Low-melting and thermal-conducting Sn-Bi-Ag solder enhanced with SnO₂ nanoparticles for reliable mini-LED microsystems. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2025, 36, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavan, J.S.; Kadavath, G.; Honecker, D.; Pazhani, A. Small-angle neutron scattering analysis in Sn-Ag Lead-free solder alloys: A focus on the Ag3Sn intermetallic phase. Mater. Charact. 2024, 217, 114385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.A. Influence of Ag and Zn on the Microstructure and Properties of Sn-40 Bi Alloy for Improved Soldering Applications. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 8084–8093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacob, G.; Ghica, V.G.; Petrescu, M.I.; Niculescu, F.; Butu, M.; Stancel, C.D.; Stanescu, M.M.; Ilie, A.A. Research on the development and characterization of Bi-Sn, Bi-Sn-Sb and Bi-Sn-Ag solder alloys. UPB Sci. Bull. B Chem. Mater. Sci. 2024, 86, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, J.R.d.S.; Reyes, R.A.V.; Gouveia, G.L.d.; Coury, F.G.; Spinelli, J.E. Evaluation of Solidification and Interfacial Reaction of Sn-Bi and Sn-Bi-In Solder Alloys in Copper and Nickel Interfaces. Metals 2024, 14, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Hou, Z.; Xie, X.; Lin, P.; Huo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X. Mechanical properties and microstructure evolution of Sn–Bi-based solder joints by microalloying regulation mechanism. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 31, 3226–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandy, B.; Briggs, E.; Lasky, R. Advantages of Bismuth-based Alloys for Low Temperature Pb-Free Soldering and Rework. Indium Corporation. Available online: https://smtnet.com/library/files/upload/advantages_of_bismuth_based_alloys_for_low_temp_soldering.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Keck, J.; Page, E.; Lee, N.C. Reliability of BGA assembled with lead-free low melting and medium melting mixed solder alloys. 15th International Conference on Electronic Packaging Technology, Chengdu, China; 2014; pp. 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaruzzaman, L.S.; Goh, Y. Microstructure and tensile properties of Sn–Bi–Co solder alloy. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2023, 34, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, E.L.; Buzatu, M.; Petrescu, M.I.; Butu, M.; Iacob, G.; Niculescu, F.; Florea, B.; Marcu, D.F.; Stancel, C.D.; Stanescu, M.M. Thermodynamic calculation of the binary systems Bi-Sn by implementing a JAVA interface. UPB Sci. Bull. B Chem. Mater. Sci. 2021, 83, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, E.; Iacob, G.; Niculescu, F.; Pencea, I.; Buzatu, M.; Petrescu, M.I.; Marcu, D.M.; Turcu, R.N.; Geanta, V.; Butu, M. Experimental Determination of the Activities of Liquid Bi-Sn Alloys. J. Phase Equilib. Diff. 2021, 42, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Composition (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Element | Bi60Sn40 | Bi60Sn35Sb5 | Bi60Sn35Ag5 |

| Bi | 59.437 | 59.411 | 58.804 |

| Sn | 39.475 | 34.533 | 34.271 |

| Sb | 0.0167 | 4.88 | 0.0177 |

| Ag | 0 | 0 | 4.93 |

| Cu | 0.122 | 0.182 | 1.63 |

| Fe | 0.018 | 0.029 | 0.024 |

| A.E.* | Bal. | Bal. | Bal. |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Analysis | Element | Weight % | Atomic % | Net Int. | Error % | P/B Ratio | R | F |

| EDS | SnL | 31.51 | 44.75 | 411.53 | 7.86 | 167.6377 | 1.0575 | 1.0067 |

| BiL | 68.49 | 55.25 | 280.07 | 12.92 | 182.9532 | 1.1144 | 1.0457 | |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Analysis | Element | Weight % | Atomic % | Net Int. | Error % | P/B Ratio | R | F |

| EDS | SnL | 20.20 | 29.05 | 371.86 | 8.01 | 101.1552 | 1.0578 | 1.0071 |

| SbL | 9.87 | 13.84 | 185.19 | 11.58 | 49.3374 | 1.0601 | 1.0073 | |

| BiL | 69.93 | 57.12 | 351.90 | 13.20 | 175.2969 | 1.1150 | 1.0456 | |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Analysis | Element | Weight % | Atomic % | Net Int. | Error % | P/B Ratio | R | F |

| EDS | SnL | 68.09 | 71.90 | 1394.17 | 6.89 | 329.1566 | 1.0388 | 1.0063 |

| AgL | 25.82 | 24.78 | 340.73 | 9.98 | 121.4951 | 1.0443 | 1.0038 | |

| BiL | 6.09 | 3.32 | 11.19 | 63.37 | 16.6575 | 1.0880 | 1.0600 | |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Solder alloy | Temp. (°C) | α (m²/s) | λ (W/m·K) | ρ (Ω·m) | σ (S/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi60Sn40 | 25 | 10.75·10-6 | 16.9316 | 3.80·10⁻⁷ | 2.63·10⁶ |

| 50 | 11.85·10-6 | 18.9363 | 4.45·10⁻⁷ | 2.25·10⁶ | |

| 75 | 12.90·10-6 | 20.9289 | 5.10·10⁻⁷ | 1.96·10⁶ | |

| 100 | 13.93·10-6 | 22.9343 | 6.35·10⁻⁷ | 1.57·10⁶ | |

| 125 | 14.93·10-6 | 24.9331 | 7.60·10⁻⁷ | 1.32·10⁶ | |

| 140 | 16.06·10-6 | 26.9261 | 8.35·10⁻⁷ | 1.20·10⁶ | |

| Bi60Sn35Ag5 | 25 | 11.91·10-6 | 18.2788 | 1.52·10⁻⁷ | 6.54·10⁶ |

| 50 | 11.56·10-6 | 18.2486 | 1.66·10⁻⁷ | 6.15·10⁶ | |

| 75 | 10.80·10-6 | 17.5224 | 1.77·10⁻⁷ | 5.69·10⁶ | |

| 100 | 10.46·10-6 | 17.4294 | 1.89·10⁻⁷ | 5.33·10⁶ | |

| 125 | 9.89·10-6 | 16.9133 | 2.01·10⁻⁷ | 4.98·10⁶ | |

| 140 | 9.56·10-6 | 16.7682 | 2.08·10⁻⁷ | 4.81·10⁶ | |

| Bi60Sn35Sb5 | 25 | 9.71·10-6 | 13.8968 | 1.53·10⁻⁷ | 6.52·10⁶ |

| 50 | 9.11·10-6 | 13.5846 | 1.63·10⁻⁷ | 6.12·10⁶ | |

| 75 | 8.66·10-6 | 13.4331 | 1.76·10⁻⁷ | 5.67·10⁶ | |

| 100 | 7.23·10-6 | 11.6486 | 1.88·10⁻⁷ | 5.30·10⁶ | |

| 125 | 6.81·10-6 | 11.3805 | 2.00·10⁻⁷ | 4.86·10⁶ | |

| 140 | 6.22·10-6 | 10.6610 | 2.08·10⁻⁷ | 4.79·10⁶ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).