1. Introduction

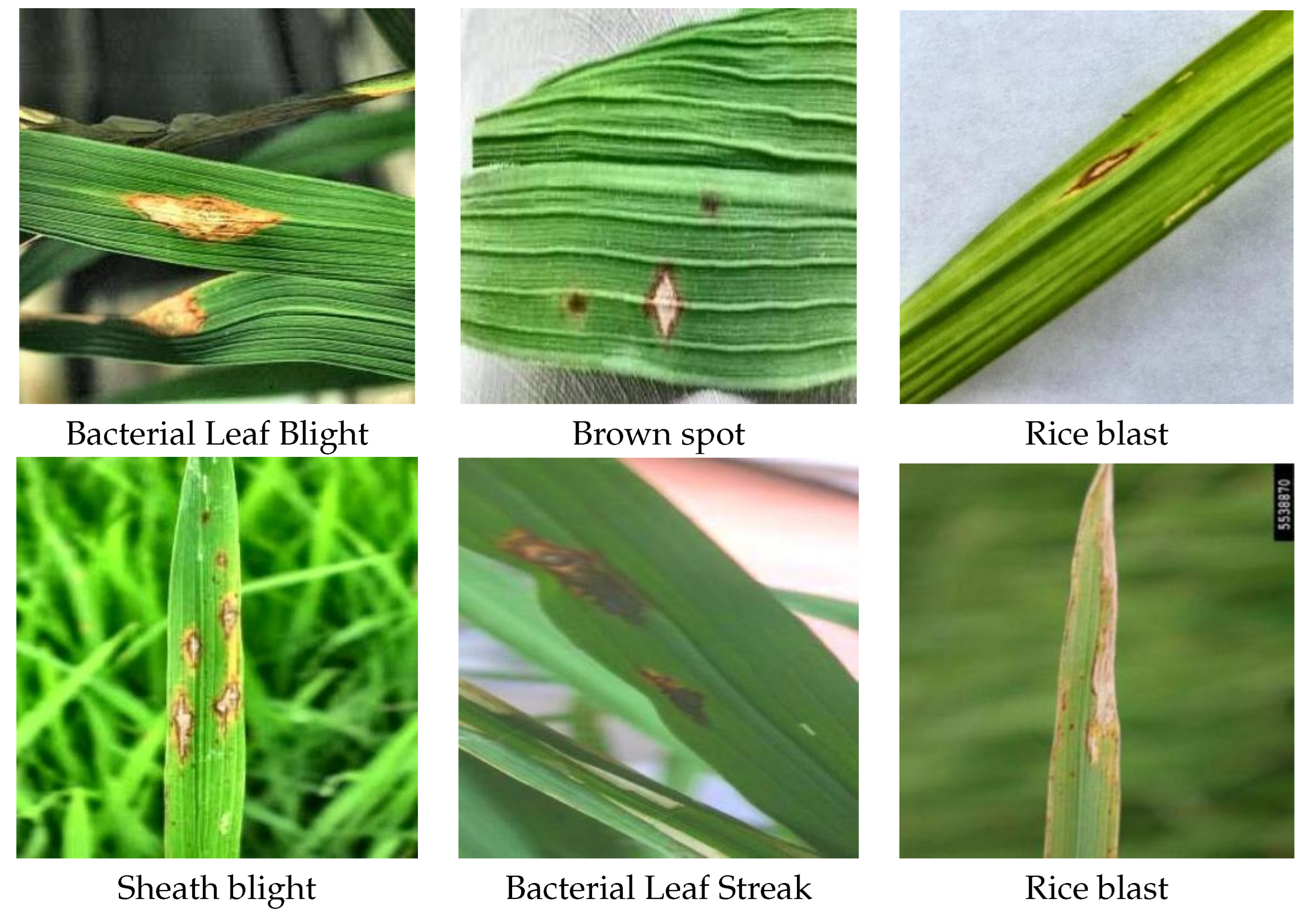

Rice is an irreplaceable staple food on which a large number of people around the world depend, and it dominates agricultural production in many Asian countries. Rice has a high yield per unit area and can efficiently utilize land resources; therefore, protecting the healthy growth of rice is to protect food security, which not only improves the economic efficiency of the land, but also maintains the ecological balance [

1,

2]. As the world’s largest producer and consumer of rice, China has ranked first in the world in terms of total rice production for many years. However, in recent years, with climate change, planting structure adjustment, and the occurrence of pests and diseases, rice production faces many challenges [

3]. Among them, a number of rice leaf diseases such as rice blast, brown spot, bacterial streak, and blight are particularly prominent, posing a serious threat to food security [

4]. Rice blast is a fungal disease caused by fungi and is the most complex and potentially harmful of all rice diseases. It can occur throughout the entire process of rice growth and is characterized by multiple sites of infestation and long duration of damage. The disease causes diamond-shaped, oval or fusiform spots on the leaves with gray or white centers and brown edges, which can lead to complete drying of the leaves in severe cases, affecting the photosynthesis and growth of rice, and ultimately resulting in reduced yields [

5]. Brown spot is also a fungal disease that appears as small oval spots that are initially light brown and then darken with a yellow halo. These spots cause necrosis of leaf tissue [

6]. Bacterial Stripe Disease A bacterial disease caused by bacteria. Under favorable conditions of warmth, high humidity, rainfall and deep water, the bacteria invade rice leaves and form small dark green translucent watery spots that gradually expand into yellowish brown streaks between the leaf veins [

7]. Stripe blight is a fungal disease caused by a fungus that infects rice stalks, leaf sheaths, or leaves at the base of the stalks, forming dark green water-soaked blotches with fuzzy edges, which eventually expand into cloudy spots. These spots can lead to leaf dieback, reduced seed fullness, and even collapse or dieback of the entire rice plant [

8]. Traditional disease detection methods mainly rely on manual experience, which is inefficient and subjective and difficult to meet the needs of modern agriculture. Therefore, the development of efficient and accurate disease detection technology is of great significance for improving disease prevention and control ability and guaranteeing food security [

9].

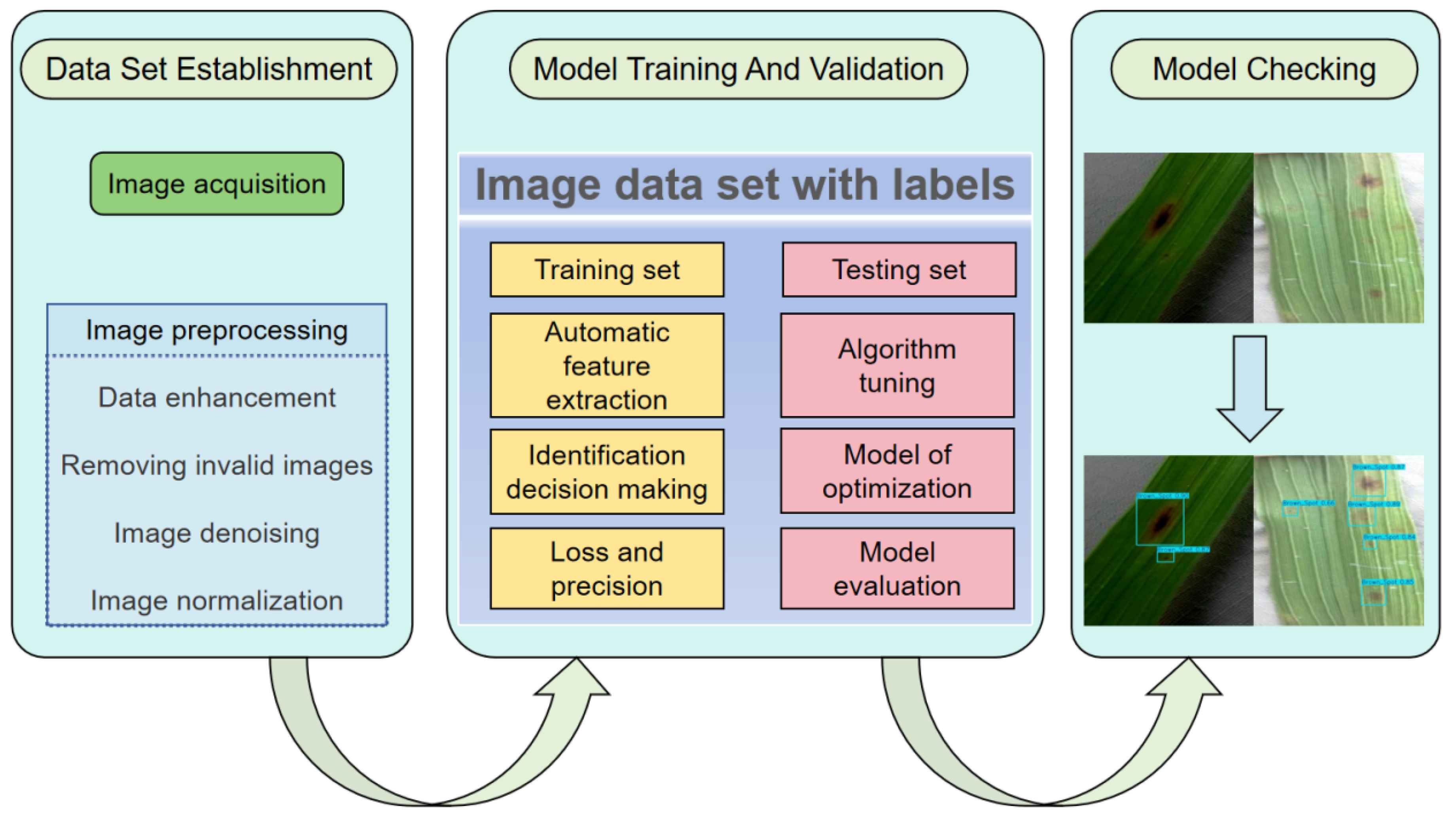

Early detection and precise identification of rice diseases are key aspects of disease prevention and control. In recent years, image-based target detection technology has gradually become a research hotspot in the field of disease detection due to its efficiency, objectivity and scalability [

10]. Early diagnosis and precise localization of diseases can be achieved by acquiring leaf images from high-resolution cameras or drones, combined with advanced image processing and machine learning algorithms [

11]. There are two main types of research on disease detection in rice or other plants in agriculture. One is a two-stage detection model based on candidate frames, which is typically represented by networks such as Faster R-CNN [

12] and Mask-RCNN [

13] , which are able to improve detection accuracy by generating candidate frames during the detection process. The other is a phase of regression-based detection networks such as YOLO [

14] and SSD [

15] , which are known for their remarkable real-time detection speed. Among them, the YOLO network has been iterated in several versions in recent years to further improve the detection accuracy and detection speed, and has been widely used in product defect detection in industry and large area detection of fruits and leaves in agriculture [

16].

Existing studies have made some progress in plant leaf detection, such as Ramadan,et al. [

17] Augmentation of rice leaf data using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) effectively enlarges the dataset size, increases the data diversity, and reduces the risk of fitting, thus improving the detection capability.Tao J, et al. [

18] Proposes a lightweight detection network based on YOLOv11n, CEFW- YOLO, through channel compression convolution and cross-channel attention, improves the ability to capture global features, and improves the detection accuracy and robustness. Wang, Chun, et al. [

19] By improving YOLOv8, it achieves a mAP as high as 94.8, which not only recognizes fresh leaves of tea tree, but also can be graded. Xu, Kang, et al. [

20]Proposed a new detection network SPLDPvB to accurately identify leaf spot disease and pests in sweetpotato. Zhou, Siyi, et al. [

21] contributed a new method for high-precision detection of gray spot disease in apple cultivation. Shi, Hang, et al. [

22] improved the detection accuracy of cabbage seedlings in the field by introducing CBAM [

23] and BiFPN [

24]. Abulizi, Abudukelimu, et al. fused the mAP in YOLOv9 with a high accuracy of 94.8 mAP, which not only can recognize fresh leaves of tea tree but also can grade them. [

25]Incorporating DySample [

26] in YOLOv9 enhances the extraction of small lesion features and suppresses the interference of the background environment, in addition to the use of MPDIoU [

27] for the learning of tomato leaf lesion edges, which improves the detection ability of the model. Zhou, Hongliang, et al. [

28] introduces cross-modal retrieval into the field of rice leaf lesion retrieval using ViT [

29] and BERT [

30] to extract the top-line rich fine-grained image and text feature sequences in the text, which are then augmented with bidirectional hybrid self-attention, and finally the warm-up bat algorithm is used to optimize the learning rate [

31] , which improves the detection accuracy of the model. Deari [

32] uses the combination of classification and detection networks to test the robustness of the rice leaf classification and eliminates the false predictions.

However, existing methods still face many challenges. Li, Pan, et al. [

33] solved the problems of field environment and inter- and intra-class differences, but still has the problem of detecting diseases in complex environments and multiple types of diseases. Li, Zhuqi, et al. [

34] proposed a tailor-made detection model for rice disease identification, which improves the accuracy, but also reveals the lack of model generalization ability, which is inappropriate for multi-type plant leaf detection. plant leaf detection. Fang, Kui, et al. [

35] proposed RLDD-YOLO to significantly improve the localization accuracy and robustness, but there exists a dependence on GPU computing power. Therefore, to address the above difficulties, this study aims to develop an efficient and robust method for rice leaf disease detection that addresses the key issues of complex environmental diversity, lightweighting, and improving the generalization ability of model detection. We proposed a joint multi-disease detection framework based on improved YOLOv11, verified its detection performance through large-scale experiments, and examined the generalization ability of the model through multiple datasets. The method can accurately identify multiple plant leaf disease types and also realize the precise localization of disease spots, which not only provides technical support for early warning and precise prevention and control of rice diseases, but also can be applied to leaf detection of more crops. The main contributions of this study are as follows:

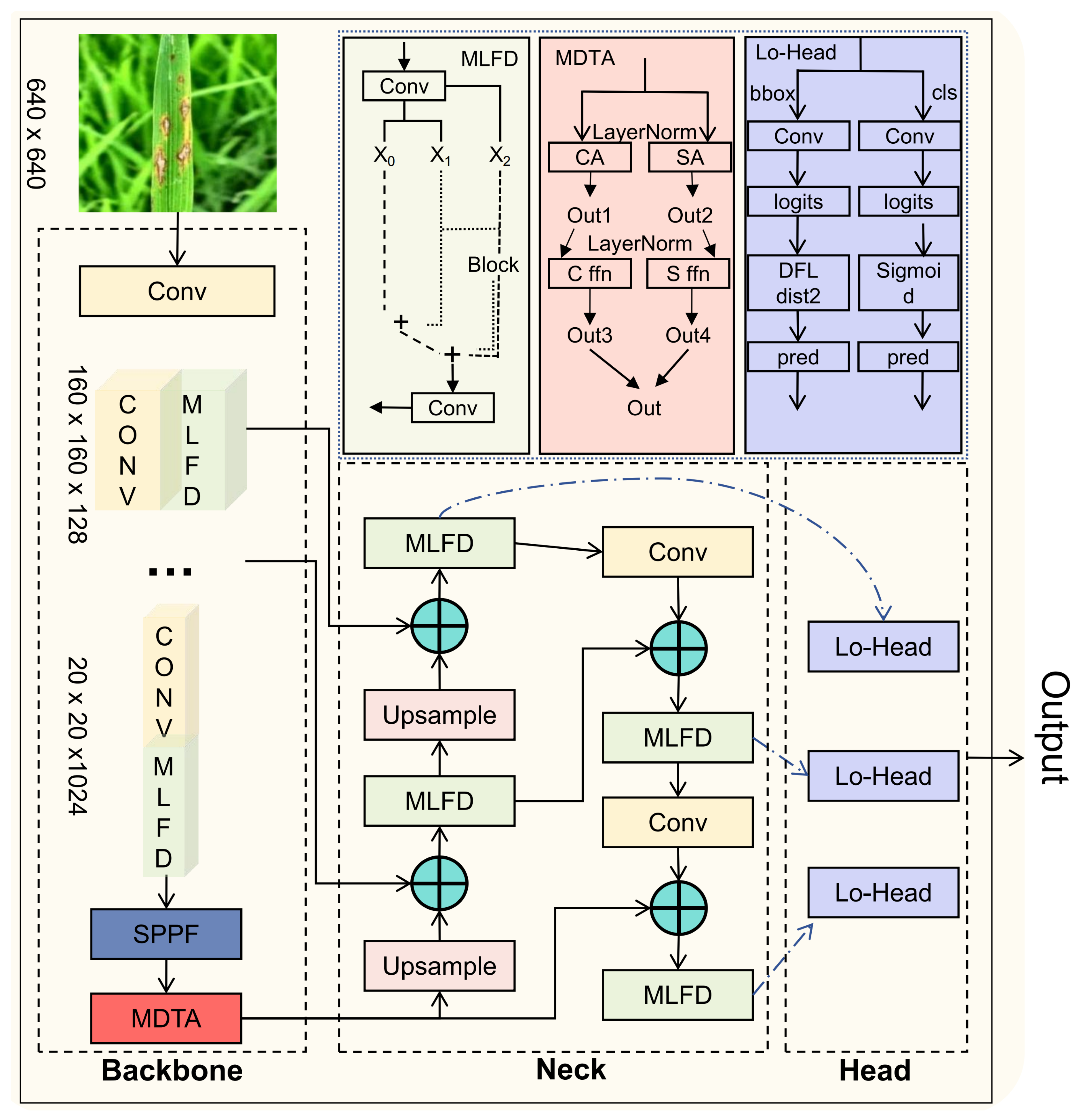

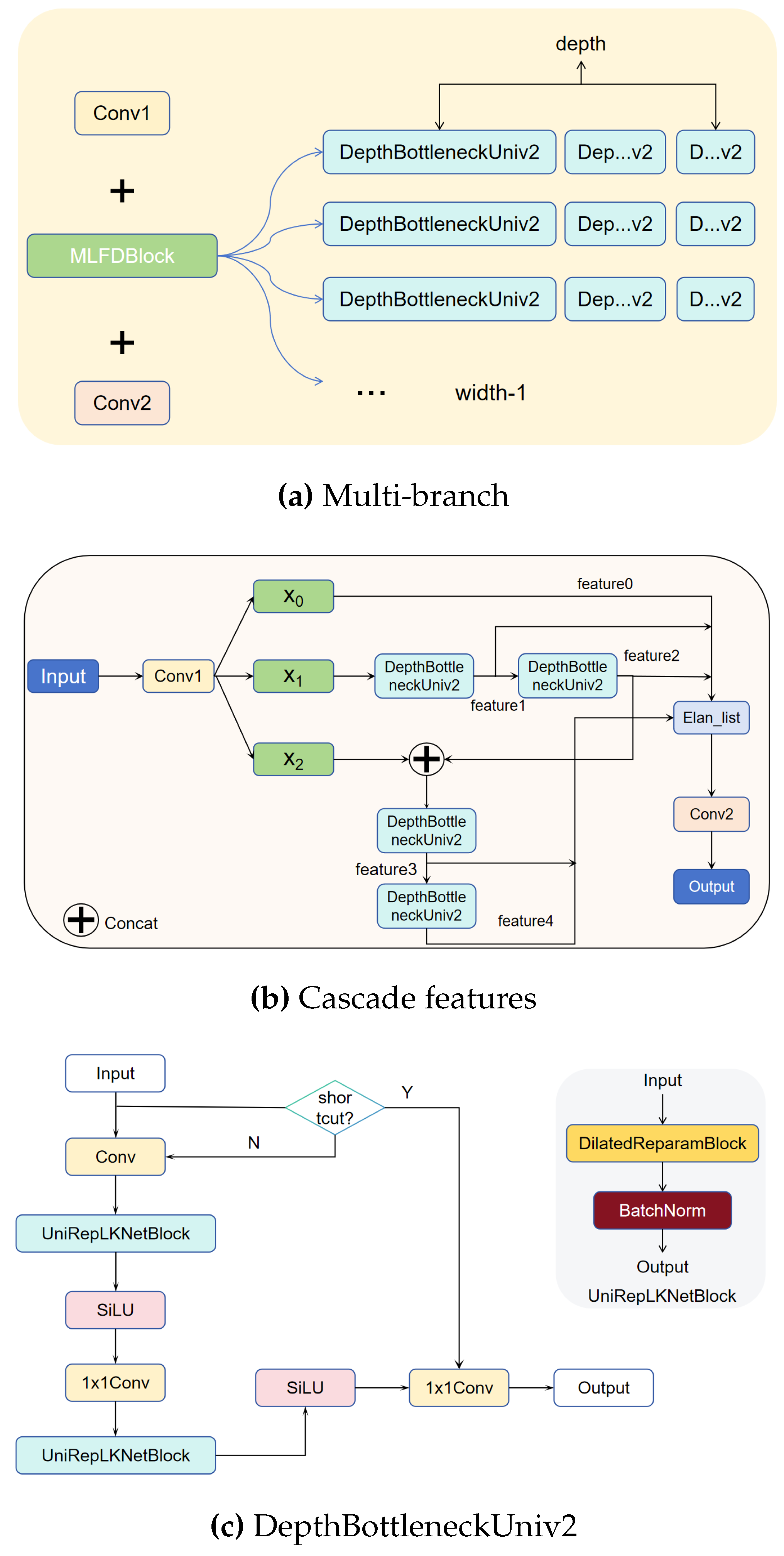

Multi-branch Large-kernel Fusion Depthwise (MLFD)module is introduced into the backbone, which utilizes the multi-branch structure to enhance the feature learning ability of the model, and at the same time adds a large convolutional kernel to extract a wide range of contextually complex features.

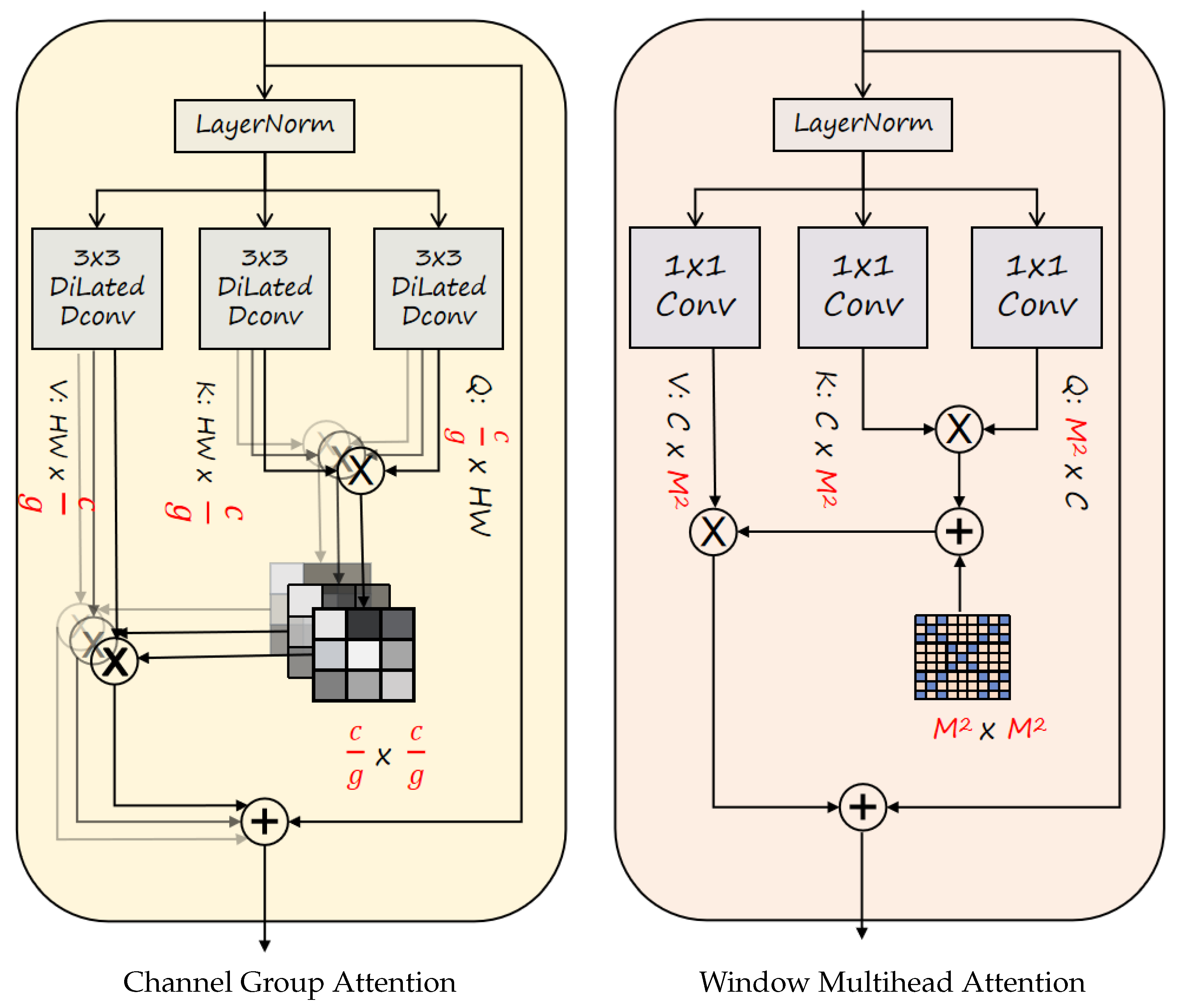

MDTA (Multi-scale Dilated Transformer Attention) module: Captures contextual dependencies in both channel and spatial dimensions via dilated self-attention.

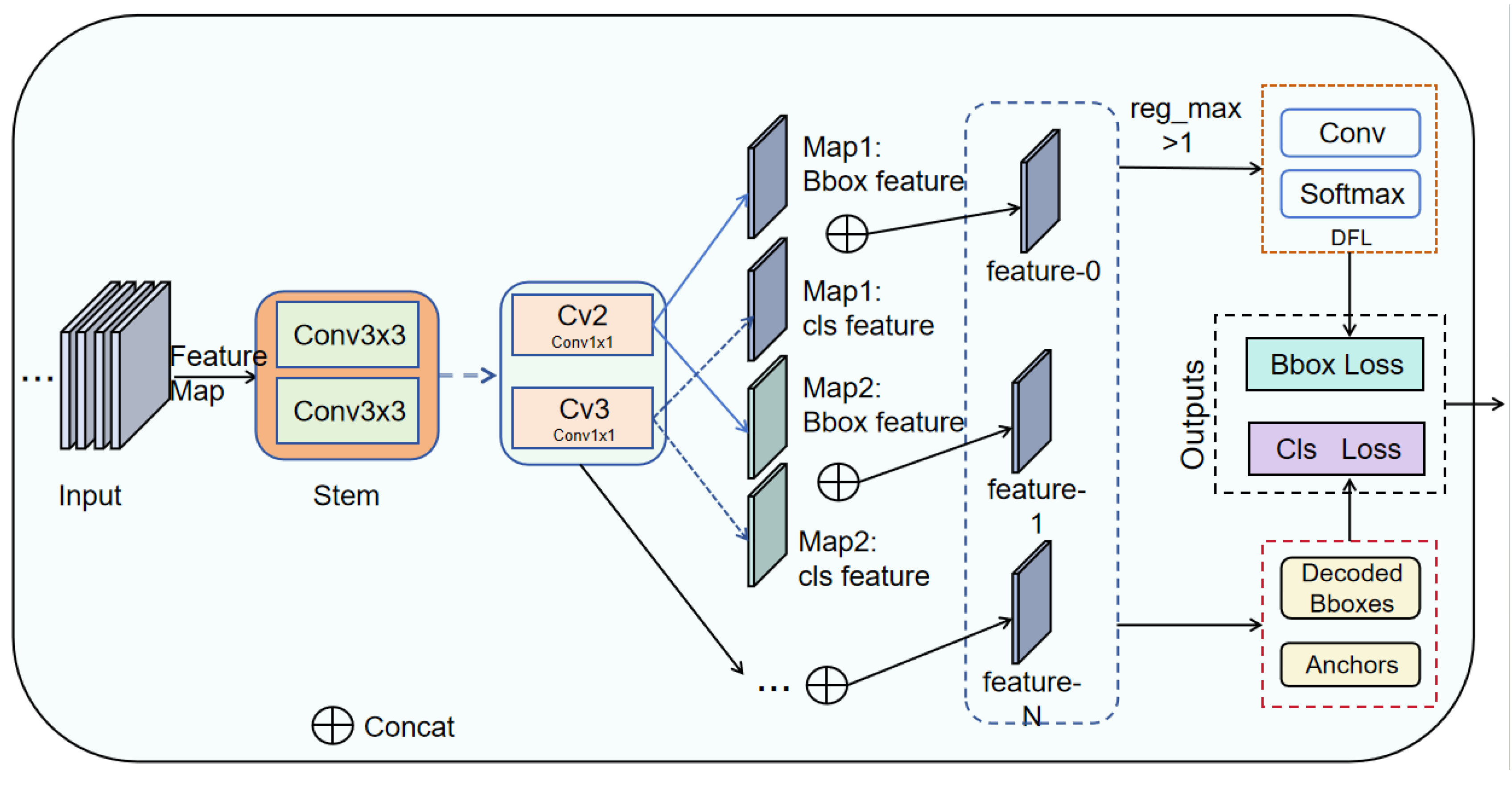

Lo-Head detection head:Reduces model complexity by optimizing the bounding box and classification branches using grouped and depthwise convolution strategies,enabling the model to achieve a better balance between efficiency and performance.

Multiple datasets such as rice leaves, potato leaves and tomato leaves were used for disease detection, and the results of the generalization experiments were compared, demonstrating the model’s excellent ability to detect diseases across plant classes.

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Baseline Model

Five versions of network models of YOLOv11 were used separately to train the research subjects of this experiment under the same experimental conditions to determine their efficacy in rice leaf disease detection, and the results are shown in the

Table 1. The analysis of this table shows that YOLOv11n has a lower P of 1.87%, 2.85%, 2.26%, 2.99%, and a lower R than Yolov11s, Yolov11m, Yolov11l, and Yolov11x, respectively, compared to the other versions. However, in terms of mAP@50 performance, the difference between the YOLOv11n version and the remaining four versions is less than 1%.The computational volume of YOLOv11n is 6.3GFLOPs, the number of parameters is 2.58M, and the size of the model is 5.2M, which are far better than the other four models, and also taking into account the differences in the model precision, the recall rate, and the mAP@50, and on the basis of guaranteeing the detection accuracy and network efficiency, YOLOv11n is selected as the benchmark model for this experiment.

3.2. Ablation Experiments

To evaluate the individual and combined contributions of the MLFD, MDTA, and Lo-Head modules within the proposed MML-YOLO framework, a series of ablation studies were conducted. The detailed results of these experiments are summarized in

Table 2. As shown in

Table 2, the incorporation of these custom-designed modules leads to substantial performance improvements over the baseline model. The original YOLOv11n architecture, used here as the benchmark, attains a precision of 0.9627, recall of 0.9517, mAP@0.5 of 0.9812, and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.7743, with a total model size of 5.2 MB. These baseline metrics provide a foundation for assessing the effectiveness of each architectural enhancement introduced in this work.

After the introduction of the MLFD module alone, its precision is improved from 0.9627 to 0.9754, and the recall is also improved to a lesser extent, with mAP@50 and mAP@50:95 increasing to 0.9820 and 0.7806, respectively. The computational demand rises from 6.3 to 7.2 GFLOPs compared to the baseline model, and the number of covariates increases from 2.58 to 2.92. Meanwhile, the FPS drops from the original 330.35 to 247.02. The improvement in precision demonstrates the advantage of the multi-branch multi-path learning of the MLFD module.

When only the MDTA module is introduced, its number of parameters and computation increase by 12% and 19%, respectively, compared with the benchmark model. However, its mAP@50:95 improves by 0.98 percentage points. There are also improvements in precision, recall, and mAP@50, but this also results in an increase in the model size. The introduction of the MDTA module fully demonstrates the effective enhancement brought to the overall network by its multi-head attention mechanism.

The addition of the Lo-Head detection head makes the overall number of parameters, computation, and model size of the network more lightweight. Its FPS performance is improved by nearly 25 compared to the original benchmark network. Although there is a slight decrease in accuracy, it does not affect the overall detection performance of the network. This reflects that the detection head is more concise and efficient in structure, and can achieve better detection results with lower computational cost, which is a significant improvement and enhancement compared with the original Detect detection head.

The combined use of the MLFD module and the MDTA module allows the overall network to reach its peak detection performance. Compared to the benchmark model, there is a total improvement of 1.98 percentage points in the mAP@50:95 metric. This enhancement highlights the excellent ability of the fusion of deeply separable convolution and large convolutional kernels with multi-head attention to handle complex features. At the same time, considering its disadvantages in terms of computation, number of parameters, FPS, and model size, continued experimentation is needed.

The fusion of the MDTA module and Lo-Head detection head gives the model a more balanced performance in terms of accuracy and lightweight. The mAP@50 is improved by 1.4 percentage points compared to the baseline model, and the model size for the fused network model of MDTA and Lo-Head is only 6MB, compared to 7.1MB for the MDTA module only. This result effectively demonstrates that the Lo-Detection Head can still perform lightweighting when fused with other modules. Similarly, the fusion of the MLFD module and the Lo-Head module also shows significant progress in terms of model lightweighting. Moreover, the FPS of the model is improved compared to when only the MLFD module is introduced.

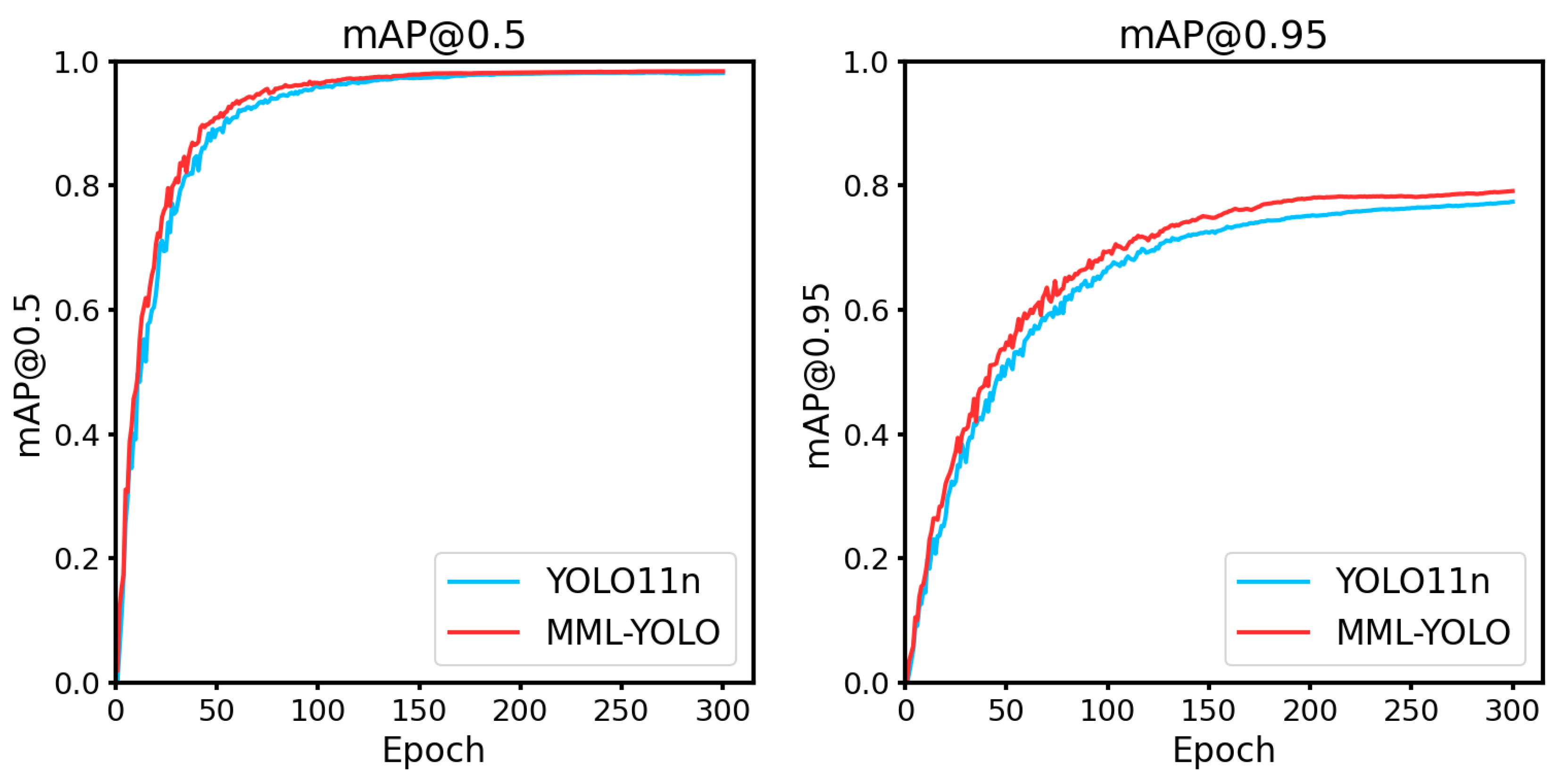

Combining the above experiments, this paper carried out the final fusion of the MLFD module, MDTA module, and Lo-Head model, i.e., MML-YOLO. The experimental results show that the precision of the three-module fusion has been improved from 0.9627 to 0.9726, and the recall has been improved from 0.9517 to 0.9553. The mAP@50 increases from 0.9812 to 0.9872, and the mAP@50:95 improves from 0.7743 to 0.7927, resulting in a total improvement of 1.98 percentage points. The model size is only 0.4 MB larger than the baseline model size, which is acceptable when considering its improvement in detection accuracy and the level of hardware deployed in practical applications. The integrated network shows significant improvement in the detection accuracy, robustness, and lightweighting for rice leaf diseases.

3.3. Comparison Experiment

In order to further validate the effectiveness of the MML-YOLO model for rice leaf disease detection, a comparison experiment was conducted in this section following the steps. These include FasterRCNN, YOLOv5n, YOLOv8n, YOLOv10n, and YOLOv11n. All of these experiments are trained in the same hardware and software environment and all use the same dataset. The experimental results are shown in

Table 3.

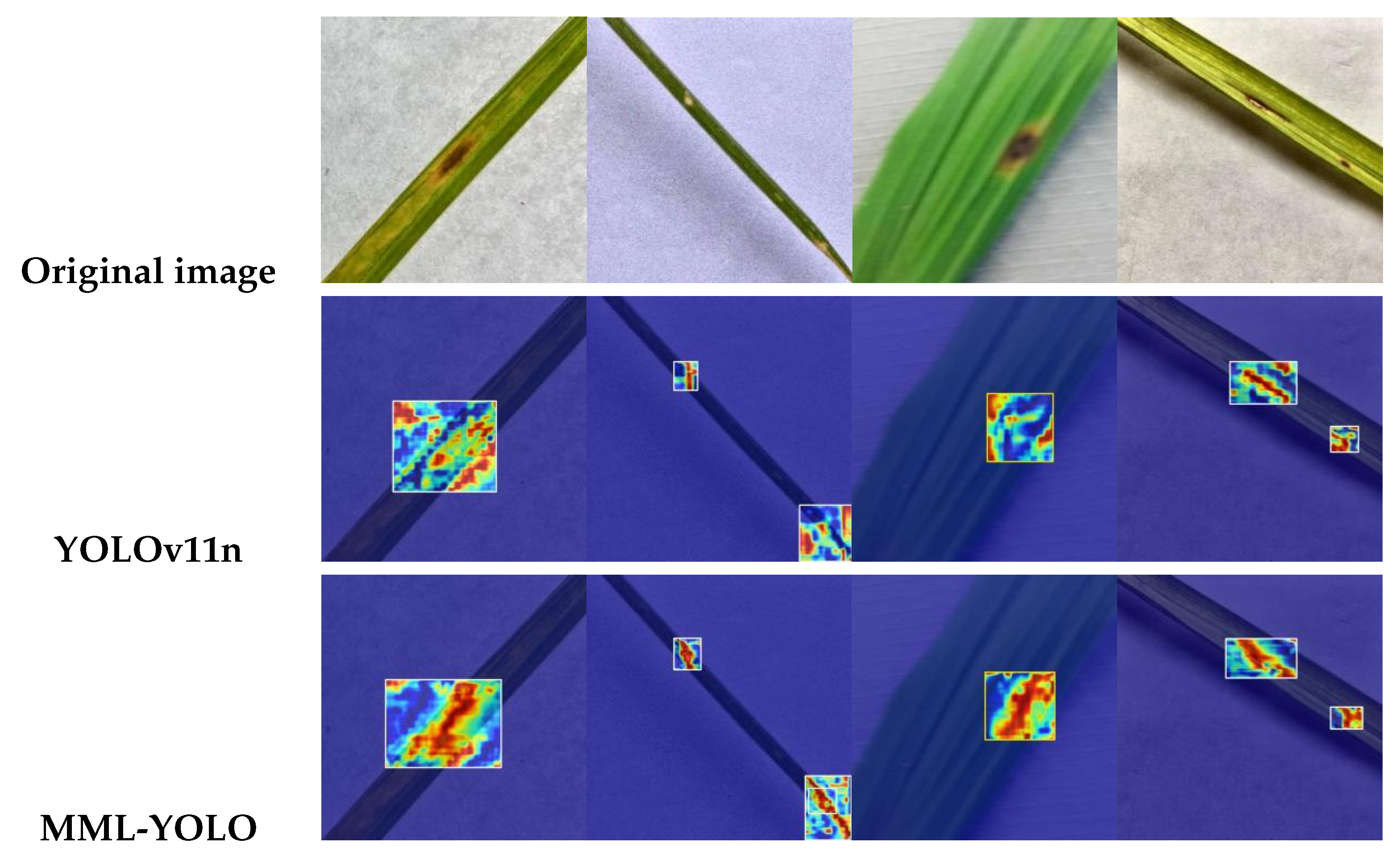

The proposed MML-YOLO model demonstrates superior performance compared to the classical two-stage detector Faster R-CNN. Specifically, Faster R-CNN achieves a precision of 0.842, recall of 0.827, mAP@0.5 of 0.9576, and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.676. In contrast, MML-YOLO attains substantially improved results across all key metrics, including a precision of 0.9726, recall of 0.9540, mAP@0.5 of 0.9872, and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 0.7927.In terms of inference speed, MML-YOLO achieves a frame rate of 248.67 FPS, significantly surpassing the 88.9 FPS reported for Faster R-CNN, thereby confirming its suitability for real-time applications. Moreover, the MML-YOLO model also excels in lightweight deployment aspects, including lower computational cost, reduced parameter count, and smaller model size. When compared to state-of-the-art lightweight detectors such as YOLOv5n (mAP@0.5:0.95 = 0.7396), YOLOv8n (0.7693), YOLOv10n (0.733), and the baseline YOLOv11n (0.7743), MML-YOLO consistently outperforms them in detection accuracy. These results collectively underscore the model’s comprehensive advantages in accuracy, speed, and deployment efficiency, making it a compelling choice for practical agricultural use cases.Furthermore, comparative analysis of visual outputs—particularly heatmaps derived from the input image, YOLOv11n, and MML-YOLO predictions—highlights the enhanced detection sensitivity of MML-YOLO in identifying lesion regions on rice leaves. As illustrated in

Figure 7, MML-YOLO provides more accurate localization and stronger activation responses than the baseline, reinforcing its effectiveness for field deployment.

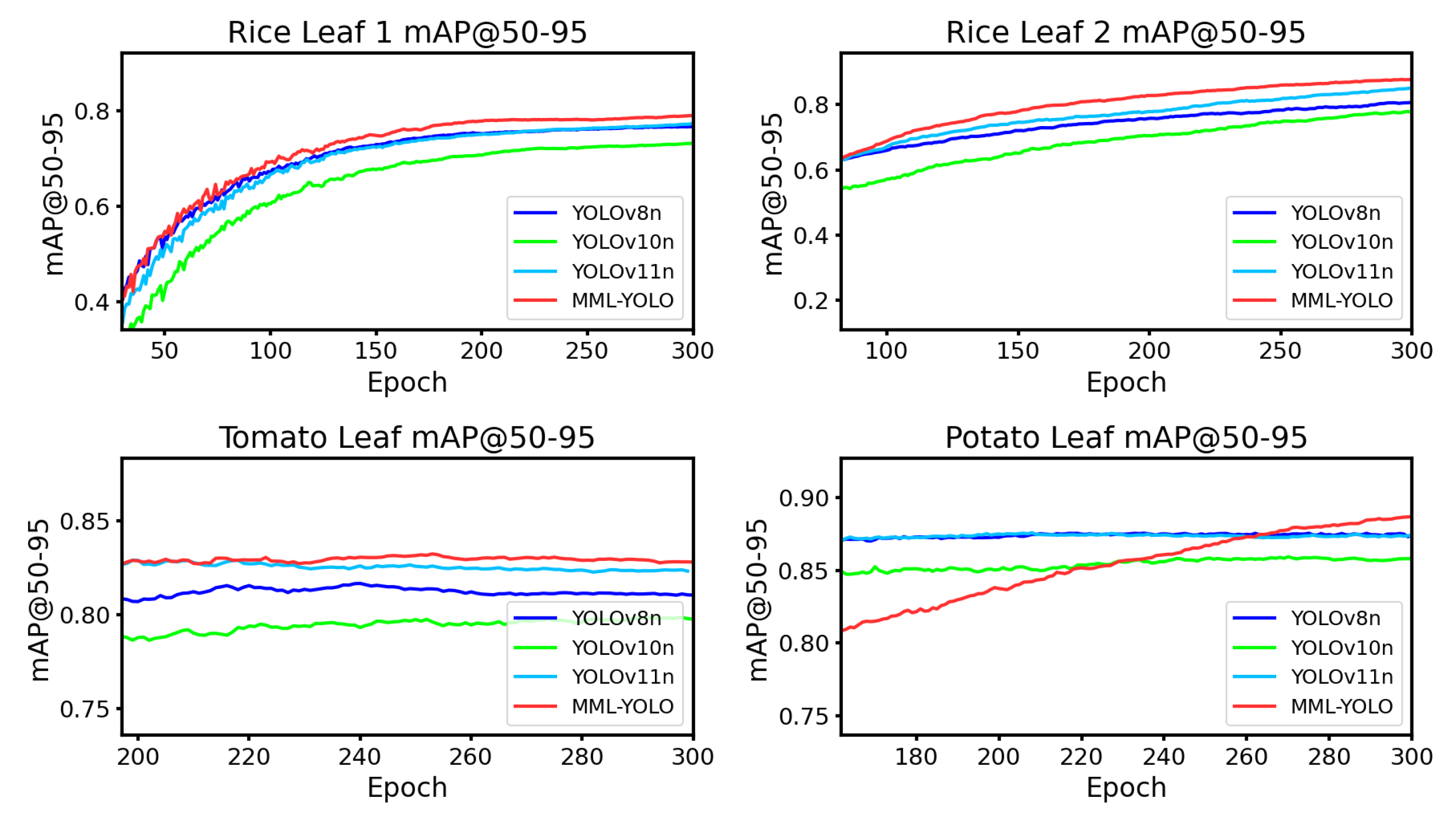

3.4. Generalization Experiment

To further substantiate the superior performance of the MML-YOLO model in detecting leaf diseases across a broad spectrum of plant species, an additional generalization experiment was conducted. Beyond the rice leaf disease detection dataset introduced earlier in this study, we expanded our evaluation to include three more diverse datasets sourced from the Roboflow platform: Rice Leaf-3G, which comprises 54,970 images covering four distinct disease categories—Bacterial Blight, Brownspot, Sheath Blight, and Rice Blast; Pomato Leaf Diseases, featuring 7,172 images across two disease types, namely Early-Blight and Late-Blight; and Tomato Leaf Diseases, consisting of 4,128 images with eight disease classifications, including Early Blight, Late Blight, Leaf Miner, Leaf Mold, Mosaic Virus, Septoria, Spider Mites, and Yellow Leaf Curl Virus. The results of these generalization experiments are presented in Figre

Figure 8. Notably, MML-YOLO demonstrates superior mAP performance at @50:95 compared to other lightweight YOLO variants. This evidence underscores the model’s efficacy and adaptability in detecting diseases on a wide range of plant leaves. We posit that MML-YOLO’s deployment on appropriate hardware platforms has the potential to significantly enhance its utility in agricultural production, enabling faster and more accurate disease detection in real-world applications.

4. Discussion

In this study, we present a new method for rice leaf disease detection based on an improved version of the YOLOv11 architecture, called MML-YOLO. the method introduces three key modules: multibranching large convolutional kernel fusion with deep convolution (MLFD), multiscale expanding Transformer Attention (MDTA), and lightweight Lo-Head detection head. Together, these modules address multiple challenges faced by traditional approaches, such as dealing with complex backgrounds, detecting small targets, and ensuring model efficiency in resource-constrained environments.The MLFD module, through its multi-branching structure, enables the model to learn diverse feature representations, specifically enhancing its ability to capture features at different spatial scales. By using a large convolutional kernel, MLFD significantly improves context extraction, which is crucial for detecting disease features under various conditions. In addition, the MDTA module enables the model to better adapt to the complex variations of disease manifestations at different scales by combining the channel and spatial attention mechanisms to effectively detect fine-grained features.The Lo-Head module, on the other hand, reduces the computational burden of the model and ensures fast inference speeds through its lightweight design, making the scheme suitable for real-time applications. Experimental results show that the MML-YOLO network exhibits superior performance in terms of precision, recall, and mAP, and achieves significant improvement over existing methods. Especially in the mAP@50:95 metric, as shown in

Figure 9.The model improves from 0.7743 to 0.7927, which shows the effectiveness of the proposed module.The fusion of MLFD, MDTA, and Lo-Head not only improves the detection accuracy, but also leads to a significant increase in computational efficiency, and the size of the model only increases by 0.4MB compared to the baseline.These advances are crucial for realistic agricultural scenarios where computational resources are usually limited and the need for real-time, accurate disease detection is critical. In addition, after extensive generalization experiments, MML-YOLO shows good adaptability in a wide range of plant disease detection, further demonstrating its robustness and scalability. This suggests that precision agriculture integrating such advanced deep learning models has a promising future, and real-time disease monitoring can significantly enhance crop management and disease prevention strategies.

However, despite the remarkable results achieved by MML-YOLO in experiments, there is still some room for research and improvement. One of the main challenges is the ability of the model to generalize across a wider range of environmental conditions and plant species. Currently, the model performs well in controlled experimental environments, but deploying it to diverse real-world agricultural environments with varying light conditions, leaf shading, and complex backgrounds remains challenging. In addition, model training has focused on rice leaf diseases, and expansion to other crops (e.g., coffee, chili peppers, or maize) will require additional data support as well as further optimization of the detection module. Future work will involve extending the dataset to include a wider variety of crop diseases and improving the model’s ability to handle this diversity without sacrificing detection performance. Additionally, when deploying this network to edge devices (e.g., agricultural robots or drones), hardware limitations will need to be addressed to ensure that inference time is minimized while maintaining high detection accuracy.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the core challenges associated with rice leaf disease detection in complex natural environments, including high computational demands, limited adaptability to diverse backgrounds, and insufficient performance in identifying small-scale lesions. Additionally, through generalization experiments, the proposed approach demonstrates promising applicability to broader plant leaf disease detection tasks.To this end, we introduce a lightweight detection framework named MML-YOLO, built upon the YOLOv11n architecture and augmented with three novel modules: MLFD, MDTA, and Lo-Head. The MLFD module enhances multi-scale feature extraction through a multi-branch architecture and large kernel designs, enabling more robust representation under variable conditions. The MDTA module incorporates both spatial and channel attention mechanisms, improving the model’s capacity to capture fine-grained and hierarchical features. Meanwhile, the Lo-Head detection head is streamlined for efficiency, removing redundant convolutional operations to reduce computational load while maintaining competitive accuracy.

Thanks to its lightweight architecture and targeted enhancements, MML-YOLO exhibits a favorable trade-off between performance and efficiency, making it particularly suitable for deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. Experimental results confirm that MML-YOLO outperforms several baseline and contemporary detection models, particularly in the mAP@0.5:0.95 metric, where it achieves a substantial performance boost. These findings validate the proposed architecture’s effectiveness across both accuracy and deployment readiness.While the results in rice leaf disease detection are highly promising, the generalization experiments also suggest MML-YOLO’s potential for broader agricultural applications. Nevertheless, certain limitations remain—especially regarding the diversity and availability of annotated plant disease datasets. Many crop disease types are caused by a wide range of environmental and biological factors, and acquiring balanced datasets for various species remains a challenge.

Future research will aim to expand the dataset across multiple growth stages and disease types of rice and other crops. By incorporating samples from crops such as coffee, pepper, peanuts, and corn, we intend to further enhance the model’s generalization capability. Moreover, future efforts will involve deploying MML-YOLO onto agricultural robots in real-world scenarios. Such deployment would allow for real-time detection and early intervention in field conditions, thereby maximizing the network’s practical value in intelligent agricultural systems and contributing to more efficient crop management and disease control.